Introduction

Old age is the most common time in life to develop epilepsy.1 Making a secure diagnosis can be difficult, and piecing together an accurate picture of events may take some time. The clinical manifestations of seizures, the causes of epilepsy, and the psychosocial impact of the diagnosis can be different in older people than in younger ones. In addition, elderly people with epilepsy have two to three times higher mortality than the general population.w1 Age related physiological changes can affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antiepileptic drugs. The situation is compounded by a paucity of good clinical studies. In this review we discuss the challenges and highlight recent developments in the diagnosis and management of epilepsy in elderly people.

Sources and selection criteria

We searched Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Collaboration with the key words “epilepsy”, “seizures”, “elderly”, “aged”, and “anticonvulsants”. We selected articles of interest from 1995 onwards and then hand searched these for earlier publications, focusing on those that specifically included elderly patients and covered clinically relevant topics.

Epidemiology

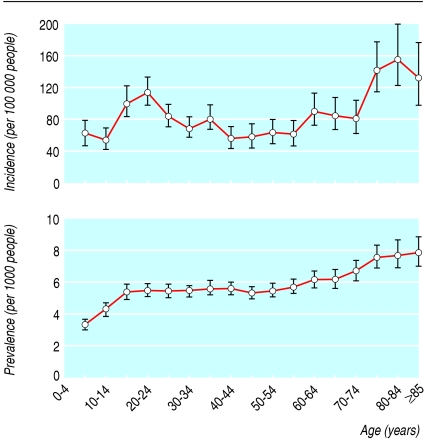

More than 11 million elderly people live in the United Kingdom, at least 1% of whom will have epilepsy. Compared with younger populations, elderly people are more prone to develop seizures, whether provoked by acute illnesses (“provoked” or “acute symptomatic” seizures) or without an obvious immediate cause (“unprovoked” seizures). Thirty per cent of acute seizures in elderly people will present as status epilepticus,w2 which carries a mortality approaching 40%.w3 The annual incidence of epilepsy (recurrent unprovoked seizures) rises from 90 per 100 000 in people between the ages of 65 and 69 to more than 150 per 100 000 for those over 80 (fig 1).2 w4 With continuing ageing of the population, the number of older people with epilepsy is set to rise further, placing an increasing burden on healthcare resources.

Fig 1.

Age specific prevalence and incidence of treated epilepsy in the United Kingdom2

Provoked seizures

In developed countries, the most common cause of provoked seizures in elderly people is acute stroke.3 w5 w6 Eight per cent of patients will develop seizures within two weeks of a haemorrhagic stroke, compared with 5% among those who have had an ischaemic event.w7

Systemic disorders precipitating acute seizures can involve metabolic or electrolyte disturbances, including hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia, uraemia, hyponatraemia, hypocalcaemia, hypothyroidism, pneumonia, urosepsis, and hepatic failure.1 Seizures secondary to acute central nervous system infections occur more commonly in developing countries than in developed countries.

A wide range of drugs commonly taken by elderly people have been reported to precipitate seizures, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, antibiotics, theophylline, levodopa, thiazide diuretics,4 and the herbal remedy ginkgo biloba.w8 Assigning an absolute risk to these drugs is usually difficult, however, as the evidence of association is on the whole poor and the risk is small. Alcohol withdrawal seizures are not uncommon in this population.

First unprovoked seizure and epilepsy

Older people who present with a first unprovoked seizure are more likely to develop seizure recurrence than are younger adults.5 Epilepsy is usually diagnosed after the occurrence of two or more unprovoked seizures. A cause can be identified in more than 60% of elderly people with epilepsy; this is classified as “remote symptomatic epilepsy.”6 w9 w10 Previous stroke is the most common underlying problem, accounting for 30-40% of all cases of epilepsy. Asymptomatic cerebral infarction can also lead to epilepsy,w11 and, paradoxically, seizures may be a marker of increased risk for subsequent stroke.7

Alzheimer's disease and other dementias are associated with a fivefold to 10-fold increase in the risk of epilepsy, which usually develops in the advanced stage.8 w12 Brain tumours and head trauma are relatively uncommon causes of epilepsy in elderly people.6

Presentation

Compared with younger patients, the presentation of epilepsy in old age is often less specific, and it may take time before a firm diagnosis can be reached.w13 Underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis are common.w14 Up to 70% of seizures are of focal onset, with or without secondary generalisation.6 Complex partial (focal) seizures may present with atypical features such as memory lapses, episodes of confusion, periods of inattention, or apparent syncope.w14 Tonic-clonic seizures can occasionally be part of a late onset idiopathic epilepsy syndrome.w15

Diagnosis

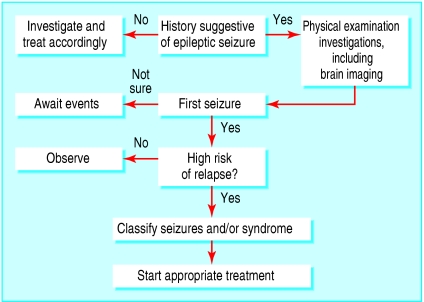

An elderly person suspected to have had new onset seizures should ideally be referred to an epilepsy specialist for rapid assessment and initiation of treatment if indicated (fig 2). A range of conditions can mimic epileptic seizures, and these should be considered by obtaining thorough medical, drug (prescribed and over the counter), and social histories (box 1). As the patient often remembers little of the episode, corroborative evidence from an observer is invaluable. The possibility of previous events should be explored, particularly partial (focal) seizures, which are often overlooked by the patient and family.

Fig 2.

Algorithm for management of seizures and epilepsy in elderly people

Physical examination should focus on the neurological and cardiovascular systems. Routine investigations should include full blood count, renal function testing, serum electrolytes, and random blood glucose.1 An electrocardiogram and a chest radiograph should be done. The need for more specialised investigations, including ambulatory prolonged electrocardiography and tilt table testing, should be guided by the clinical scenario.

Elderly patients with new onset seizures should have a brain scan.w16 Magnetic resonance imaging is more sensitive than computed tomography in detecting relevant anatomical abnormalities.w17 Age related changes, including diffuse atrophy, periventricular hyperintensities due to hypertension, and artherosclerosis, are common and should not routinely be interpreted as the cause of seizures.

Routine scalp electroencephalography is not sensitive or specific for the diagnosis in elderly people,w18 nor does the absence of epileptiform abnormalities rule out epilepsy.9 Electroencephalographic findings, therefore, should be interpreted within the clinical context. Such low sensitivity and specificity argues against the indiscriminate use of routine electroencephalography in elderly people with a low suspicion of epilepsy. When the diagnosis is in doubt, the patient can be referred to a specialist centre for videoelectroencephalographic monitoring.w19 w20

Management

The goal of management should be the maintenance of a normal lifestyle, ideally by complete control of seizures without (or with minimal) side effects, so that the patient's functional capacity is restored to his or her maximal potential. Time is needed to explain the likely cause, diagnosis, and necessity for treatment. The support of the family and caregivers can be paramount to a successful outcome.

Box 1: Differential diagnoses of seizures in elderly people

Neurological

Transient ischaemic attack

Transient global amnesia

Migraine

Narcolepsy

Restless legs syndrome

Cardiovascular

Vasovagal syncope

Orthostatic hypotension

Cardiac arrhythmias

Structural heart disease

Carotid sinus syndrome

Endocrine/metabolic

Hypoglycaemia

Hyponatraemia

Hypokalaemia

Sleep disorders

Obstructive sleep apnoea

Hypnic jerks

Rapid eye movement sleep disorders

Psychological

• Non-epileptic psychogenic seizures

Treatment

Treatment for provoked seizures should be directed towards the underlying cause. All elderly people reporting more than one well documented or witnessed unprovoked event should be offered antiepileptic drug treatment. Whether treatment should be started after a single unprovoked seizure remains controversial. Prospective randomised studies involving patients across all age groups, such as the recently published multicentre study of early epilepsy and single seizures (MESS) study,10 have shown that, compared with deferring treatment until further episodes have occurred, immediate treatment after a first unprovoked seizure does not improve the long term remission rate. However, because of the physical and psychological consequences of recurrence, prophylactic treatment should be considered after a first unprovoked event in an elderly person at high risk of recurrence, such as those with a causative brain lesion or an epileptiform electroencephalogram, or at his or her request.

The decision whether or not to start antiepileptic drug treatment should be made after ample discussion with the patient and family about the risks and benefits of both courses of action. Classification of the seizures should be followed by an understanding of the goals of treatment and specific attention to the pros and cons of the most appropriate antiepileptic drugs, including their side effects and potential for drug-drug interactions. Some mention should be made of possible morbidity and mortality from continuing seizure activity. Driving regulations should also be raised if appropriate.

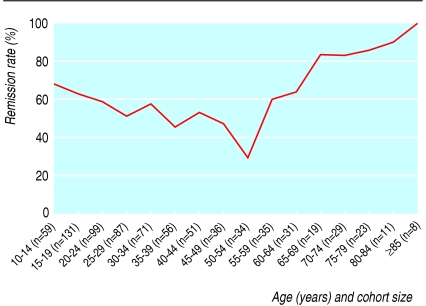

Epilepsy in elderly people generally responds well to treatment. Up to 80% of patients with onset in old age can be expected to remain seizure-free with anti-epileptic drug treatment (fig 3).11 Elderly people are, however, more susceptible to the adverse effects of drugs than their younger counterparts.12 Whether treatment can be safely withdrawn after a period of seizure freedom has not been determined, so most older patients will remain on antiepileptic drugs for life.

Fig 3.

Remission rates according to age at starting treatment for epilepsy in 780 newly diagnosed patients. Remission was defined as freedom from all seizures for at least one year at evaluation11

Pharmacology

The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antiepileptic drugs differ in old age (box 2) from those in younger patients.12 w21 w22 Age related alteration in receptor affinity and number may lead to altered drug sensitivity and impaired homoeostasis.13 When treating epilepsy in elderly people, biological age (assessed by clinical judgment) is more important than chronological age in terms of choice and usage of antiepileptic drugs. Drugs that can cause cognitive impairment or complex pharmacokinetic interactions are best avoided. Some of the advantages and disadvantages of the commonly available anticonvulsants in this population are highlighted in the table.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of antiepileptic drugs in elderly people

| Antiepileptic drugs | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Established | ||

| Phenobarbital | Broad spectrum

|

Sedation

|

| Once daily

|

Cognitive impairment

|

|

| Cheapest

|

Behavioural problems

|

|

|

|

Enzyme induction

|

|

| Bone loss | ||

| Phenytoin | Once daily

|

Sedation

|

| Cheap

|

Allergic reactions

|

|

|

|

Saturation kinetics

|

|

|

|

Enzyme induction

|

|

| Bone loss | ||

| Carbamazepine | “Gold standard” for partial seizures

|

Neurotoxicity

|

| Studied in elderly

|

Allergic reactions

|

|

| Relatively cheap

|

Enzyme inducer

|

|

|

|

Hyponatraemia

|

|

| Bone loss | ||

| Sodium valproate | “Gold standard” for generalised seizures

|

Tremor

|

| Broad spectrum

|

Weight gain

|

|

| Few interactions

|

Parkinsonism

|

|

| Relatively cheap | Bone loss | |

| Modern | ||

| Lamotrigine | Broad spectrum

|

Slow titration

|

| Good tolerability

|

Dose related rash

|

|

| Few interactions

|

Insomnia

|

|

| Studied in elderly | ||

| Gabapentin * | No allergic reactions

|

Sedation

|

| No interactions

|

Dizziness

|

|

| Studied in elderly | Weight gain | |

| Topiramate | Broad spectrum

|

Slow titration

|

| Weight loss

|

Cognitive impairment

|

|

|

|

Renal stones

|

|

| Few data in elderly | ||

| Oxcarbazepine | Good tolerability

|

Neurotoxicity

|

|

|

Allergic rash

|

|

|

|

Selective enzyme induction

|

|

| Hyponatraemia | ||

| Tiagabine * | Few allergic reactions

|

Dizziness

|

| Few interactions | Few data in elderly | |

| Levetiracetam * | Few allergic reactions

|

Sedation

|

| No interactions | Behavioural problems | |

| Pregabalin * | No allergic reactions

|

Dizziness

|

| No interactions

|

Weight gain

|

|

| Few data in elderly | ||

| Zonisamide * | Broad spectrum

|

Slow titration

|

| Once daily

|

Sedation

|

|

| No interactions

|

Renal stones

|

|

| Few data in elderly |

Licensed only for adjunctive use in the United Kingdom.

Few data specific to elderly people are available to help the clinician to choose the best treatment for the individual patient.1 As in other populations, a drug should be chosen with a spectrum of activity and side effect and interaction profiles that offer the potential to produce freedom from seizure without long term sequelae. Starting with a low dose and titrating slowly is generally recommended to avoid toxicity. A modest maintenance dose should be targeted and events awaited. If the first drug fails as a result of an idiosyncratic reaction, poor tolerability at low to moderate dosage, or lack of efficacy, an alternative should be tried. If the patient tolerates the second drug with a useful but suboptimal response, combination treatment with low doses of both agents can be considered.w23 Written instructions, careful explanation of the regimen, and the provision of dosing trays can aid adherence.

Box 2: Pharmacological considerations in elderly people

Pharmacokinetic

Reduction in:

Protein binding

Hepatic metabolism

Enzyme inducibility

Renal elimination

Pharmacodynamic

Alterations in:

Brain neurotransmitters

Receptor function

Autonomic pharmacology

Homoeostatic mechanisms

Tolerability

Greater risk of:

Altered kinetics and dynamics

Polypharmacy and interactions

Idiosyncratic reactions

Physical and psychiatric comorbidities

Box 3: Useful websites for support groups for patients

Asian and Oceanian Epilepsy Association (Asia)—www.aoea-online.org

Epilepsy Action (United Kingdom)—www.epilepsy.org.uk

Epilepsy Scotland (Scotland)—www.epilepsyscotland.org.uk

Epilepsy Foundation (United States)—www.epilepsyfoundation.org

The Epilepsy Project (United States)—www.epilepsy.com

International Bureau for Epilepsy (international)—www.ibe-epilepsy.org/

Joint Epilepsy Council (United Kingdom)—www.jointepilepsycouncil.org.uk

Established antiepileptic drugs

All the established antiepileptic drugs, with the exception of ethosuximide, are efficacious against partial seizures with or without secondary generalisation, the typical seizure type in elderly people.14 Carbamazepine may have a small benefit over sodium valproate for control of partial seizures,15 but no trial has specially included elderly patients. The barbiturates are not generally recommended for use in elderly people because of their sedative and behavioural side effects.16 As the pharmacokinetics of phenytoin changes from first order to zero order at therapeutic dosage, plasma concentrations must be monitored to avoid toxicity.w24 Hyponatraemia due to carbamazepine, particularly when coadministered with diuretics, occurs more commonly later in life, although this is often asymptomatic.w25

Phenobarbital, phenytoin, and carbamazepine can produce idiosyncratic reactions, in particular skin rashes, and complex drug-drug interactions, as they are all substrates for and inducers of hepatic monooxygenase enzymes. They can interact with a wide range of lipid soluble drugs commonly used in elderly people, including warfarin, cardiac antiarrhythmics, theophylline, corticosteroids, antidepressants, cytotoxics, macrolide antibiotics, and St John's wort.17

Enzyme induction also accelerates the catabolism of vitamin D, leading to decreased calcium absorption, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and increased bone loss.18 Some authorities recommend calcium and vitamin D supplements and regular bone density measurements for elderly patients at particular risk of osteoporosis—for example, because of prolonged treatment, multiple drugs, or non-ambulatory lifestyle.w26

Sodium valproate has a broad spectrum of activity and is the drug of choice for the unusual idiopathic generalised epilepsy syndrome presenting late in life. It may have a slightly better cognitive and behavioural profile than the other established antiepileptic drugs.16 In addition, valproate does not induce hepatic drug metabolising enzymes. It can reduce bone mineral density, however, possibly by interfering with osteoblastic function.w27 Valproate can also produce dose dependent tremor and reversible parkinsonism.w28

Modern antiepileptic drugs

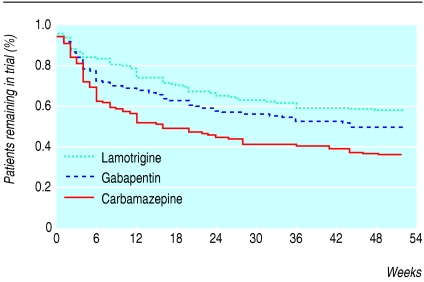

None of the modern antiepileptic drugs has been shown to have superior efficacy to the established agents for the treatment of newly diagnosed partial and tonic-clonic seizures,14 although lamotrigine and oxcarbazepine have shown better tolerability,19,20 increasing the likelihood of a successful outcome. Only two randomised controlled trials have specifically recruited elderly patients; these found that lamotrigine and gabapentin produced fewer adverse events than carbamazepine, with similar efficacy (fig 4).21,22 Pooled data from 13 trials of lamotrigine involving elderly patients have confirmed its good tolerability profile.23 Open label studies have indicated that levetiracetam may be effective in this population.24 w29 Oxcarbazepine may be similarly well tolerated in younger and older adults, although 6% of the elderly cohort developed hyponatraemia, particularly if they were taking concomitant natriuretic drugs.w30 Long term data on the value of the newer antiepileptic drugs in elderly people are lacking.

Fig 4.

Percentage of patients remaining in the trial over time. Elderly patients randomised to monotherapy with lamotrigine (n=199, P<0.001) or gabapentin (n=194, P=0.008) were more likely to remain on treatment than those receiving carbamazepine (n=197)22

Summary points

Around 1-2% of elderly people have epilepsy, often secondary to cerebrovascular disease; presentation is often non-specific, and many other conditions can mimic an epileptic seizure

With appropriate pharmacological treatment, most elderly people with epilepsy will remain seizure-free

When choosing an antiepileptic drug, particular attention should be paid to side effects and potential for drug-drug interactions

Randomised clinical trials suggest that lamotrigine and gabapentin are better tolerated than carbamazepine in elderly people

Epilepsy can have a profound physical and psychological impact in old age, with a substantial negative effect on quality of life

The number of elderly people with epilepsy is set to rise further, placing an increasing burden on healthcare resources

Psychosocial implications

Epilepsy can have a profound physical and psychological impact in old age. Elderly people are particularly vulnerable to injuries during seizures. The clinical situation is often complicated by a range of neurodegenerative, cerebrovascular, neoplastic, and psychiatric comorbidities. Problems with concomitant drugs are common. The stigma associated with diagnosis of epilepsy can be particularly hard to deal with at this time of life.25 Quality of life may also be adversely affected by the loss of a driving licence that may never be recovered. The unpredictable nature of seizures can lead to social withdrawal. Loss of confidence and reduced independence can result in premature admission to nursing homes and residential care facilities. Self help groups can provide useful support for patients (box 3).

Additional educational resources

International League Against Epilepsy—www.epilepsy.org

European Epilepsy Academy—www.epilepsy-academy.org

American Epilepsy Society—www.aesnet.org

Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)—Clinical guideline 70: Diagnosis and management of epilepsy in adults, 2003. Clinical guideline 81: Diagnosis and management of epilepsies in children and young people, 2005 (www.sign.ac.uk)

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)—Clinical guideline 20: The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care, 2004 (www.nice.org.uk)

American Academy of Neurology—www.aan.com (a range of epilepsy guidelines are available on this site)

Conclusion

Development of epilepsy is common in later life. The prognosis in terms of seizure control may be better than in younger populations. The choice of antiepileptic drugs should focus on avoidance of side effects and adverse drug-drug interactions. The objective should be complete control of seizures, with enhanced quality of life. Optimal management requires rapid assessment, accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, assured education, and sympathetic support.

Supplementary Material

Additional references (w1-w30) are on bmj.com

Additional references (w1-w30) are on bmj.com

Contributors: PK did the initial literature search and produced the first draft. MJB provided PK with previously published and presented material and developed the final manuscript, adding substantial new material.

Competing interests: Over the past 20 years MJB has been involved in clinical trials for most of the pharmaceutical companies that develop and market antiepileptic drugs and has also lectured on their behalf. He has consultancy agreements with Pfizer, Eisai, Johnson and Johnson, and UCB Pharma. He previously had similar associations with GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Sanofi Aventis. He has research grants from Cephalon, UCB Pharma, and Pfizer. PK has received research support from and spoken at meetings sponsored by Pfizer, Janssen Cilag, and UCB Pharma.

References

- 1.Stephen LS, Brodie MJ. Epilepsy in elderly people. Lancet 2000;355: 1441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace H, Shorvon S, Tallis R. Age-specific incidence and prevalence rates of treated epilepsy in an unselected population of 2 052 922 and age-specific fertility rates of women with epilepsy. Lancet 1998;352: 1790-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annegers JF, Hauser WA, Lee R-J, Rocca WA. Incidence of acute symptomatic seizures in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935-1984. Epilepsia 1995;36: 327-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franson KL, Hay DP, Neppe V, Dahdal WY, Mirza WU, Grossberg GT, et al. Drug-induced seizures in the elderly: causative agents and optimal management. Drugs Aging 1995;7: 38-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopkins A, Garman A, Clarke C. The first seizure in adult life: value of clinical features, electroencephalography and computerised scanning in prediction of seizure recurrence. Lancet 1988;331: 721-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935-1984. Epilepsia 1993;34: 453-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleary P, Shorvon S, Tallis R. Late-onset seizures as a predictor of subsequent stroke. Lancet 2004;363: 1184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendez MF, Lim GTH. Seizures in elderly patients with dementia: epidemiology and management. Drugs Aging 2003;20: 791-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Cott AC. Epilepsy and EEG in the elderly. Epilepsia 2002;43(suppl 3): 94-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marson A, Jacoby A, Johnson A, Kim L, Gamble C, Chadwick D, et al. Immediate versus deferred antiepileptic drug treatment for early epilepsy and single seizures: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365: 2007-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohanraj R, Brodie MJ. Diagnosing refractory epilepsy: response to sequential treatment schedules. Eur J Neurol (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Arroyo S, Kramer G. Treatment epilepsy in the elderly: safety considerations. Drug Saf 2001;24: 991-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLean AJ, Le Couteur DG. Aging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev 2004;56: 163-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Clinical trials of antiepileptic medications in newly diagnosed patients with epilepsy. Neurology 2003;60(suppl 4): S2-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marson AG, Williamson PR, Hutton JL, Clough HE, Chadwick DW. Carbamazepine versus valproate monotherapy for epilepsy: a meta-analysis. Epilepsia 2002;43: 505-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Neuropsychological effects of epilepsy and antiepileptic drugs. Lancet 2001;357: 216-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patsalos PN, Fröscher W, Pisani F, van Rijn CM. The importance of drug interactions in epilepsy patients. Epilepsia 2002;43: 365-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ensrud KE, Walczak TS, Blackwell T, Ensrud ER, Bowman PJ, Stone KL. Antiepileptic drug use increases rates of bone loss in older women: a prospective study. Neurology 2004;62: 2051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brodie MJ, Richens A, Yuen AWC. Double-blind comparison of lamotrigine and carbamazepine in newly diagnosed epilepsy. Lancet 1995;345: 476-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bill PA, Vigonius U, Pohlmann H, Guerreiro MM, Kochen S, Saffer D, et al. A double-blind controlled clinical trial of oxcarbazepine versus phenytoin in adults with previously untreated epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 1997;27: 195-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brodie MJ, Overstall PW, Giorgi L, the UK Lamotrigine Elderly Study Group. Multicenter, double-blind, randomised comparison between lamotrigine and carbamazepine in elderly patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 1999;37: 81-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowan AJ, Ramsay RE, Collins JF, Pryor F, Boardman KD, Uthman BM, et al. New onset geriatric epilepsy: a randomized study of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine. Neurology 2005;64: 1868-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giorgi L, Gomez G, O'Neill F, Hammer AE, Risner M. The tolerability of lamotrigine in elderly patients with epilepsy. Drugs Aging 2001;18: 621-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrendelli JA, French J, Leppik I, Morrell MJ, Herbeuval A, Han J, et al. Use of levetiracetam in a population of patients aged 65 years and older: a subset analysis of the KEEPER trial. Epilepsy Behav 2003;4: 702-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker GA, Jacoby A, Buck D, Brooks J, Potts P, Chadwick DW. The quality of life of older people with epilepsy: findings from a UK community study. Seizure 2001;10: 92-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.