Abstract

The purpose of this work was to analyze the effect of serum on the physicochemical surface properties and adhesion to glass and silicone of Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 at 37°C. As is presented using thermodynamics analysis, serum minimizes the interaction of cells with water, which correlates well with the increase in hydrophobicity and in bacterial adhesion to glass and silicone.

Enterococci are important nosocomial pathogens (7, 10), with Enterococcus faecalis accounting for 90% of human enterococcal infections, including bacteremia, wound infections, abdominal and urinary tract infections, and endocarditis (18, 22). Bacterial adhesion to biomaterials (14, 21) is directly responsible for increases in bacterial multiplication and biofilm formation (1). Despite the fact that knowledge of enterococcal virulence mechanisms is still limited (9, 18), it is generally agreed that before bacteria anchor to the host surface, the physicochemical characteristics of both the surface cell and the substratum are the main factors mediating bacterial adhesion (4, 16, 20, 23, 24). In this context, the cellular surface hydrophobicity is, for some authors, the most important physicochemical parameter controlling adhesion (1, 12, 15). The initial adhesion step in high-ionic-strength medium (17) can be also interpreted in terms of the Lifshitz-van der Waals forces (LW) and acid-base forces (AB) (4, 15, 20).

Because physicochemical characterization depends on cell surface properties and these in turn depend on the culture and experimental conditions, this paper attempts to analyze the influence of the culture medium on the adhesion of E. faecalis ATCC 29212 to glass and silicone rubber at a temperature similar to that inside the human body (37°C). The surface characterization and adhesion experiments on both substrata were carried out in a parallel plate flow chamber with bacteria grown in a standard culture medium and in the same medium supplemented with 10% human serum.

Microorganisms were stored in porous beads at −80°C; blood agar plates were inoculated with E. faecalis ATCC 29212 at 37°C and then incubated overnight in 100 ml of Trypticase soy broth (TSB), without or with 10% human serum. The cells were harvested by centrifugation for 5 min at 1,000 × g and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline for flow experiments (final concentration, 3 × 108 cells ml−1) and with distilled and deionized water for contact angle assays.

Glass was acid cleaned, and silicone (kindly provided by Willy Rüsch AG, Stuttgart, Germany) was cleaned by sonication with an available surfactant solution. Both were extensively washed with water.

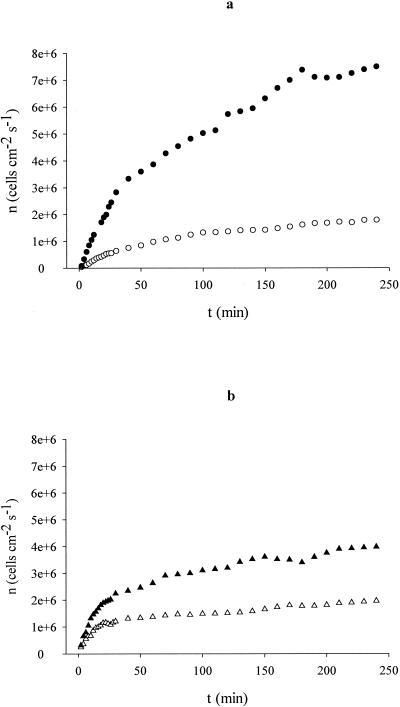

The parallel plate flow chamber has been described in detail previously (19). A parallel plate flow chamber was placed on the stage of a microscope equipped with a 40× ultra-long-working-distance objective. Bacterial suspensions were recirculated with a pulse-free flow of 0.034 ml s−1 while the system was maintained at 37°C. Images of microorganisms adhering to the bottom plate of the flow chamber were registered by a charge-coupled device camera and stored in a computer. The images were captured every 2 min at the beginning of the adhesion process and, after that, at every 10 min of the adhesion process up to 4 h (data presented in Fig. 1; also see Table 3).

FIG. 1.

(a) Average levels of adhesion to glass of Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 grown in serum-free medium (○) and 10% serum-containing medium (•) during the duration of the experiment. The triplicate experiments coincided within a 15% margin of error. (b) Average levels of adhesion to silicone of Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 grown in serum-free medium (▵) and 10% serum-containing medium (▴) during the duration of the experiment. The triplicate experiments coincided within a 15% margin of error.

TABLE 3.

Average number of Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 bacteria adhering to glass and to silicone initially (j0 and at 4 h from the beginning of the adhesion experiments, taking into account the microorganism growth with or without serum

| Growth medium | Substratum | j0a | No. of adhered bacteria (106) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSB | Glass | 383 | 1.8 |

| TSB | Silicone | 565 | 2.0 |

| TSB + 10% serum | Glass | 1,562 | 7.5 |

| TSB + 10% serum | Silicone | 1,483 | 4.0 |

j0, initial adhesion rates calculated from Fig. 1.

Experiments were done in triplicate and compared with an unpaired Student t test (confidence interval, 95%).

Using the sessile drop technique (2), water, formamide, and diiodomethane contact angles (θW, θF, and θD, respectively) were determined on lawns of dried bacteria (Table 1). Briefly, bacteria suspended in demineralized water were layered onto 0.45-μm-pore-size filters (Millipore, Molsheim, France) by using negative pressure. Filters were left to air dry for 45 min at 37°C and were then placed in an environmental chamber, which was connected to a thermostat to maintain the temperature at 37°C and saturated with vapor of the liquid used. The images were taken as has been previously described (13).

TABLE 1.

Water, formamide, and diiodomethane contact angles of Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 grown in serum-free TSB and 10% serum-containing TSB, as well as contact angles for both employed substrata, and Lifshitz-van der Waals (γLW), acid-base (γAB), and total (γTotal) surface tension component and electron donor (γ−) and electron acceptor (γ+) parameters of microorganisms and employed substrataa

| Growth medium or substratum | Contact angle (degrees)

|

Parameter value (mJ m−2)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θW | θF | θD | γLW | γ− | γ+ | γAB | γTotal | |

| Growth media | ||||||||

| TSB | 49 | 37 | 47 | 27.0 | 28.2 | 2.7 | 17.4 | 44.4 |

| TSB + 10% serum | 68 | 36 | 47 | 30.3 | 7.2 | 4.1 | 10.9 | 41.2 |

| Substrata | ||||||||

| Glass | 19 | 16 | 30 | 31.5 | 50.1 | 2.3 | 21.5 | 53.0 |

| Silicone | 92 | 89 | 67 | 19.4 | 11.7 | 0.4 | 4.3 | 23.7 |

The average standard deviation over three separate cultures of microorganisms came to ±2 degrees for contact angles, ±2.0 mJ m−2 for γLW, ±5.0 mJ m−2 for γ−, and ±0.8 mJ m−2 for γ+.

The surface tension components (Table 1), γLW and  , were calculated from the application of the Young-Dupré equation (25) to each probe liquid:

, were calculated from the application of the Young-Dupré equation (25) to each probe liquid:

|

(1) |

where γ− and γ+ are the electron donor and electron acceptor parameters of the γAB component, respectively,  is the surface tension of the probe liquid (L), and B is bacteria.

is the surface tension of the probe liquid (L), and B is bacteria.

Components and parameters of surface tension of probe liquids at 37°C were calculated according to González-Martín et al. (5).

According to van Oss et al. (25), the total interaction free energy between microorganisms and substrata through water (ΔGadhTotal) can be calculated as the sum of a term which takes into account the interaction between them through dipole-dipole, dipole-induced dipole, and induced dipole-induced dipole LW interactions and a second term which takes into account their tendency to give or accept electrons, which is their Lewis or acid-base character:

|

(2) |

where

|

(3) |

and

|

(4) |

and W is water and S is the substratum. Results are summarized in Table 2. Serum-grown bacteria present higher hydrophobicity than serum-free-grown cells, considering θW as an indicator of hydrophobicity (2). This behavior is in agreement with that found by Ljungh and Wadstrom, even working with a different methodology (11), although some other authors detected decreases or no changes in surface hydrophobicity after growth in serum (3, 6).

TABLE 2.

Lifshitz-van der Waals ( ), acid-base (

), acid-base ( ), and total (

), and total ( ) interaction free energy levels of the adhesion of Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 grown with and without serum to glass and silicone in water

) interaction free energy levels of the adhesion of Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 grown with and without serum to glass and silicone in water

| Growth medium | Substratum | Interaction free energy value (mJ m−2)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||

| TSB | Glass | −1.5 | 16.1 | 14.6 |

| TSB | Silicone | 0.1 | −7.9 | −7.8 |

| TSB + 10% serum | Glass | −2.2 | −3.8 | −6.0 |

| TSB + 10% serum | Silicone | 0.2 | −29.6 | −29.4 |

The average standard deviation over three separate cultures of microorganisms was ±0.5 mJ m−2 for  and ±5 mJ m−2 for

and ±5 mJ m−2 for  .

.

Comparing the hydrophobicity results with those of adhesion experiments, the highest hydrophobicity is well correlated with the greatest adhesion to both substrata, as presented in Fig. 1 and Table 3 (P < 0.05 for comparisons between serum-grown and serum-free-grown bacteria at the beginning of and after 4 h of the adhesion experiment). A similar agreement is seen between thermodynamics predictions and adhesion data: despite the positive value of  for the adhesion to glass of serum-free-grown bacteria, thermodynamics calculations clearly predict that serum would be able to increase the adhesion to glass and silicone. This behavior is mainly due to the changes in the short-range ABs, because the long-range LWs remain unchanged under the different growth medium conditions.

for the adhesion to glass of serum-free-grown bacteria, thermodynamics calculations clearly predict that serum would be able to increase the adhesion to glass and silicone. This behavior is mainly due to the changes in the short-range ABs, because the long-range LWs remain unchanged under the different growth medium conditions.

A different approach to the information that the free energy values for total adhesion provide can be obtained by taking into account that  represents the total free energy interaction between medium 1 (bacteria) and medium 2 (substratum) when immersed in a given medium 3 (water) (expressed as ΔG1,3,2). Using the method described in reference (8), this can be expressed as

represents the total free energy interaction between medium 1 (bacteria) and medium 2 (substratum) when immersed in a given medium 3 (water) (expressed as ΔG1,3,2). Using the method described in reference (8), this can be expressed as

|

(5) |

where ΔG1,2, ΔG1,3, and ΔG2,3 are the interaction free energy values (in a vacuum) between media 1 and 2, 1 and 3, and 2 and 3, respectively, and γ3 is the surface tension of medium 3. The different ΔGij values, where i and j symbolize 1, 2, or 3, have been calculated (Table 4) based on the fact that

|

(6) |

This way of splitting the total free energy permits a deeper understanding of the forces that provoke the increase in adhesion of serum-grown bacteria to both substrata.

TABLE 4.

ΔG12 interaction free energies for Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 bacteria (B), grown without serum and with serum, with glass (G), silicone rubber (R), and water (W)a

| Growth medium | Interaction free energy value (mJ m−2) with:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔGBG | ΔGBR | ΔGBW | |

| TSB | −98 | −64 | −117 |

| TSB + 10% serum | −97 | −66 | −97 |

ΔG12 interaction free energy value between silicone rubber and water is ΔGRW = −81 mJ m−2 and between glass and water is ΔGGW = −137 mJ m−2. The average standard deviation over three separate cultures of microorganisms was 5 mJ m−2.

From the data presented in Table 4, it can be clearly seen that addition of serum to the growth medium does not affect the direct interaction between bacteria and either glass or silicone rubber, the two substrata. However, there was an important change of about 20 mJ m−2 between the ΔGBW values before and after serum growth. Taking this fact into account, the highest adhesion observed for serum-grown bacteria, regardless of the substratum selected, can be seen to be more closely related to changes in their behavior with water than to the kind of substratum used ([ΔGBW (with serum)] < [ΔGBW (without serum)]). The lower affinity of serum-grown bacteria for water drives the cells to more favorable surroundings (i.e., with regard to substrata).

It is interesting that the data obtained from the splitting of  , although in accordance with that obtained from the measurement of water contact angles (i.e., higher hydrophobicity for serum-grown cells than for serum-free-grown bacteria) provides a step further towards the analysis of the adhesion behavior of this bacterium, since it provides a possible elucidation of how hydrophobicity changes act on the adhesion process.

, although in accordance with that obtained from the measurement of water contact angles (i.e., higher hydrophobicity for serum-grown cells than for serum-free-grown bacteria) provides a step further towards the analysis of the adhesion behavior of this bacterium, since it provides a possible elucidation of how hydrophobicity changes act on the adhesion process.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Junta de Extremadura-Consejería de Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología, and the Fondo Social Europeo for the Ph.D. grant awarded to A.M.G.M., for financial support, and for the IPR99C016 and IPR00C046 projects. We also thank the DGES for the PB97-0378 project and Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Spain (FIS 00/0293).

REFERENCES

- 1.An, Y. H., and R. J. Friedman. 2000. Handbook of bacterial adhesion. Principles, methods and applications. Humana Press Inc., Totowa, N.J.

- 2.Busscher, H. J., A. H. Weerkamp, H. C. van der Mei, A. W. J. van Pelt, H. P. de Jong, and J. Arends. 1984. Measurements of the surface free energy of bacterial cell surfaces and its relevance for adhesion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:980-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carballo, J., C. M. Ferreiros, and M. T. Criado. 1991. Influence of blood proteins in the in vitro adhesion of Staphylococcus epidermidis to Teflon, polycarbonate, polyethylene, and bovine pericardium. Rev. Esp. Fisiol. 47:201-208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallardo-Moreno, A. M., H. C. Van der Mei, H. J. Busscher, and C. Pérez-Giraldo. 2001. The influence of subinhibitory concentrations of ampicillin and vancomycin on physico-chemical surface characteristics of Enterococcus faecalis 1131. Colloids Surfaces B 24:285-295. [Google Scholar]

- 5.González-Martín, M. L., B. Janczuk, L. Labajos-Broncano, and J. M. Bruque. 1997. Determination of the carbon black surface free energy components from the heat of immersion measurements. Langmuir 13:5991-5994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzman, C. A., C. Pruzzo, and L. Calegari. 1991. Enterococcus faecalis: specific and non-specific interactions with human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 15:157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hancock, L. E., and M. S. Gilmore. 2000. Pathogenicity of enterococci, p. 251-258. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferreti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 8.Israelachvili, J. 1992. Intermolecular and surface forces. Academic Press Limited, London, England.

- 9.Jett, B. D., M. M. Huycke, and M. S. Gilmore. 1994. Virulence of enterococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 7:462-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuusela, P., T. Vartio, M. Vuento, and E. B. Myhre. 1985. Attachment of staphylococci and streptococci on fibronectin, fibronectin fragments, and fibrinogen bound to a solid phase. Infect. Immun. 50:77-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ljungh, A., and T. Wadstrom. 1995. Growth conditions influence expression of cell surface hydrophobicity of staphylococci and other wound infection pathogens. Microbiol. Immunol. 39:753-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majtán, V., and L. Majtánová. 2000. Effect of quaternary ammonium salts and amine oxides on the surface hydrophobicity of Enterobacter cloacae. Chem. Pap. 54:49-52. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreno del Pozo, J. 1994. Ph.D. thesis. University of Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain.

- 14.Nickel, J. C., P. Feero, J. W. Costerton, and E. Wilson. 1989. Incidence and importance of bacteriuria in postoperative, short-term urinary catheterization. Can. J. Surg. 32:131-132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira, M. A., M. M. Alves, J. Azeredo, M. Mota, and R. Oliveira. 2000. Influence of physico-chemical properties of porous microcarriers on the adhesion of an anaerobic consortium. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24:181-186. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poortinga, A. T., R. Bos, and H. J. Busscher. 2001. Charge transfer during staphylococcal adhesion to TiNOX coatings with different specific resistivity. Biophys. Chem. 91:273-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rijnaarts, H. H. M., W. Norde, J. Lyklema, and A. J. B. Zehnder. 1999. DLVO and steric contributions to bacterial deposition in media of different ionic strengths. Colloids Surf. 14:179-195. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sartingen, S., E. Rozdzinski, A. Muscholl-Silberhorn, and R. Marre. 2000. Aggregation substance increases adherence and internalization, but not translocation, of Enterococcus faecalis through different intestinal epithelial cells in vitro. Infect. Immun. 68:6044-6047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sjollema, J., H. J. Busscher, and A. H. Weerkamp. 1989. Real time enumeration of adhering microorganisms in a parallel plate flow cell using automated image analysis. J. Microbiol. Methods 9:73-78. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smets, B. F., D. Grasso, and M. A. Engwall, and B. J. Machinist. 1999. Surface physicochemical properties of Pseudomonas fluorescens and impact on adhesion and transport through porous media. Colloids Surf. B 14:121-139. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stickler, D. J. 1996. Bacterial biofilms and the encrustation of urethral catheters. Biofouling 9:293-305. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Süβmuth, S. D., A. Muscholl-Silberhorn, R. Wirth, M. Susa, R. Marre, and E. Rozdzinski. 2000. Aggregation substance promotes adherence, phagocytosis, and intracellular survival of Enterococcus faecalis within human macrophages and suppresses respiratory burst. Infect. Immun. 68:4900-4906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teixeira, P., and R. Oliveira. 1999. Influence of surface characteristics on the adhesion of Alcaligenes denitrificans to polymeric substrates. J. Adhesion Sci. Technol. 13:1287-1294. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Loosdrecht, M. C. M., W. Norde, J. Lyklema, and A. J. B. Zehnder. 1990. Hydrophobic and electrostatic parameters in bacterial adhesion. Aquat. Sci. 52:103-114. [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Oss, C. J. 1994. Interfacial forces in aqueous media. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.