Summary

The HAP46/BAG-1 protein: regulator of HSP70 chaperones, DNA-binding protein and stimulator of transcription

Keywords: Bcl-2-associated athanogene BAG-1, DNA binding, HSP70/HSC70-associating protein HAP46, HSP70/HSC70 molecular chaperones, transcriptional stimulation

Abstract

HAP46/BAG-1M and its isoforms affect the protein-folding activities of mammalian HSP70 chaperones. They interact with the ATP-binding domain of HSP70 or HSC70, leaving the substrate-binding site available for further interactions. Trimeric complexes can therefore form with, for example, transcription factors. Moreover, HAP46/BAG-1M and the larger isoform HAP50/BAG-1L bind to DNA non-specifically and enhance transcription in vitro and upon overexpression in intact cells. These factors are linked to positive effects on cell proliferation and survival. This review focuses on DNA-binding activity and transcriptional stimulation by HAP46/BAG-1M, and presents a molecular model for the underlying mechanism. It is proposed that transcription factors are recruited into complexes with HAP46/BAG-1M or HAP50/BAG-1L through HSP70/HSC70 and that response-element-bound complexes that contain HAP46/BAG-1M and/or HAP50/BAG-1L along with HSP70s target and affect the basal transcription machinery.

Introduction

HAP46/BAG-1M was discovered independently by three groups who used expression screening to search for partners of the respective proteins that they were studying. Takayama et al (1995) screened a mouse embryo cDNA library with Bcl-2 and cloned a cDNA that encodes a 219-residue protein, which they called Bcl-2-associated athanogene 1 (BAG-1). The name 'athanogene' (from the Greek word athánatos, meaning 'against death') was chosen because transfected cells responded less drastically to apoptotic stimuli. Similar sequences were cloned by Bardelli et al (1996), who screened the same library with the plasma-membrane receptor for hepatocyte growth factor. The third group used a human expression library and glucocorticoid receptors, and so discovered the 274-residue human protein (Zeiner & Gehring, 1995). This has an apparent molecular weight of 46 kDa and was first named receptor-associating protein RAP46, then later renamed HSP70/HSC70-associating protein of apparent molecular size 46 kDa (HAP46) (Zeiner et al, 1997) for the reasons discussed below. The gene is located on region p12 of human chromosome 9 (Takayama et al, 1996). It gives rise to a single transcript of ∼1.4 kb (Zeiner & Gehring, 1995) and the promoter contains binding sites for several transcription factors that are important for expression (Yang et al, 1999).

The three sequences (Takayama et al, 1995; Zeiner & Gehring, 1995; Takayama et al, 1996) are homologous, with the exception of 55 additional amino acids that are present in the human protein. The mouse cDNAs have subsequently been extended so that their similarity covers almost the entire sequence (Packham et al, 1997; Takayama et al, 1998). Such homology was surprising considering that different target proteins had been used for the interaction screening. This became even more puzzling when additional proteins were found to interact with the HAP46/BAG-1 protein, such as other members of the nuclear-receptor superfamily (Zeiner & Gehring, 1995; Froesch et al, 1998; Liu et al, 1998), several unrelated transcription factors (Zeiner et al, 1997), the platelet-derived growth-factor receptor (Bardelli et al, 1996), the protein kinase RAF-1 (Song et al, 2001), the human homologue SIAH-1A of Drosophila Seven in absentia (Matsuzawa et al, 1998) and proteasomes (Lüders et al, 2000a).

A breakthrough came with the discovery that the heat-shock protein HSP70 and the constitutive HSC70 are important interacting partners of the protein (Gebauer et al, 1997; Höhfeld & Jentsch, 1997; Takayama et al, 1997; Zeiner et al, 1997). This interaction occurs with mammalian and insect HSP70s, but not with endoplasmic BIP or HSP70s that are of plant, yeast or bacterial origin (Zeiner et al, 1997). This is noteworthy because the bait proteins that were used for cloning were produced in the baculovirus system, which contains insect HSP70s, and therefore explains the large range of interacting partners of HAP46/BAG-1.

HAP46/BAG-1 affects HSP70 activities

HSP70s are a prominent and highly conserved family of chaperones that are involved in many biological processes. They support the folding of newly synthesized and misfolded polypeptides, prevent protein aggregation, aid protein translocation across membranes (see, for example, Mayer et al, 2001) and also have a role in the assembly of multimeric proteins. A well-known example is the generation of heteromeric states of steroid hormone receptors (Mayer et al, 2001), but there are other instances of similar functions (Niyaz et al, 2003). HSP70s characteristically consist of two different parts: the ATP-binding domain and the substrate-binding domain. They cooperate closely and their three-dimensional structures are known (Mayer et al, 2001). The ATP domain consists of two roughly symmetrical subdomains, I and II, with a central cleft that harbours the nucleotide-binding site. Bound ATP is slowly hydrolysed and the resulting ADP is exchanged for new ATP. The substrate-binding domain has the ability to interact with an almost unlimited range of proteins (Mayer et al, 2001).

Importantly, the interaction of HAP46/BAG-1 with HSP70/HSC70 makes use of the ATP-binding domain rather than the substrate-binding domain (Gebauer et al, 1997; Höhfeld & Jentsch, 1997; Takayama et al, 1997; Zeiner et al, 1997), and trimeric complexes can be formed with HSP70s as mediators between HAP46/BAG-1 and various proteins attached to the substrate domain (Takayama et al, 1997; Zeiner et al, 1997; Niyaz et al, 2003). Deletion of the last 47 residues from HAP46/BAG-1 showed that the carboxy-terminal portion is responsible for binding HSP70s (Takayama et al, 1997). As this interaction is such a prominent feature of HAP46/BAG-1 and its isoforms, this domain was named the BAG domain (Takayama et al, 1999). The interaction of this domain with HSP70s has been analysed in detail by X-ray analysis and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), complemented by mutagenesis. The BAG domain consists of a bundle of three α-helices that contact subdomain II of the HSP70s, mostly through electrostatic interactions (Briknarová et al, 2001; Sondermann et al, 2001). Of particular importance is Arg 237 of HAP46/BAG-1M (human sequence), as the conversion of this residue to Ala greatly reduced HSC70 binding and abolished in vitro activity. For HSP70s, the major portion of subdomain II is sufficient for binding to HAP46/BAG-1, although the affinity is greatly reduced (Brive et al, 2001). Phage display and peptide scanning yielded several potential contact regions on HSC70 in two main areas, one on each subdomain: one corresponds to the site detected by X-ray analysis and NMR, whereas the other lies on the opposite side of the cleft (Petersen et al, 2001). It is not known at present whether HAP46/BAG-1 requires more than one point of contact to exert an effect on the HSP70s.

An important aspect of the HAP46/BAG-1 interaction with HSP70s is the inhibition of their ATP-dependent chaperone activity (Gebauer et al, 1997; Takayama et al, 1997; Zeiner et al, 1997), which is concomitant with a reduction in the binding of HSP70s to misfolded proteins (Gebauer et al, 1998). However, HAP46/BAG-1 has also been described as a positive co-chaperone (Terada & Mori, 2000), and so the effect on HSP70s has still not been definitively determined. Apart from protein folding, HAP46/BAG-1 also promotes the ADP/ATP exchange reaction and/or enhances the ATPase activity of the chaperone (Höhfeld & Jentsch, 1997; Gebauer et al, 1998; Terada & Mori, 2000; Brehmer et al, 2001; Gässler et al, 2001). However, HAP46/BAG-1 has a less pronounced effect on nucleotide exchange than does GrpE (Brehmer et al, 2001), which is the prokaryotic counterpart of HAP46/BAG-1 but has a different structure. X-ray analysis of GrpE in complex with the ATP domain of Escherichia coli hsp70 protein DnaK disclosed contacts on both subdomains and showed a substantial opening of the central cleft (Mayer et al, 2001). It therefore seems reasonable that HAP46/BAG-1 might also use two contacts to produce a similar opening (Petersen et al, 2001) and binding might favour an alternative structure of the HSP70 ATP domain with a more open conformation (Osipiuk et al, 1999).

The interaction of HAP46/BAG-1 with HSP70 chaperones has an additional aspect relating to cellular regulation. The protein kinase RAF-1 is one of the few proteins known thus far to interact with HAP46/BAG-1 independent of HSP70 chaperones. The contact site is located in the C-terminal portion of HAP46/BAG-1, partially overlapping with the BAG domain (Song et al, 2001). This then explains competitive binding of HAP46/BAG-1 and RAF-1 to HSC70, thereby providing a molecular switch in RAF-1/ERK signalling under conditions of increased HSP70 expression (Song et al, 2001).

HAP46/BAG-1 isoforms

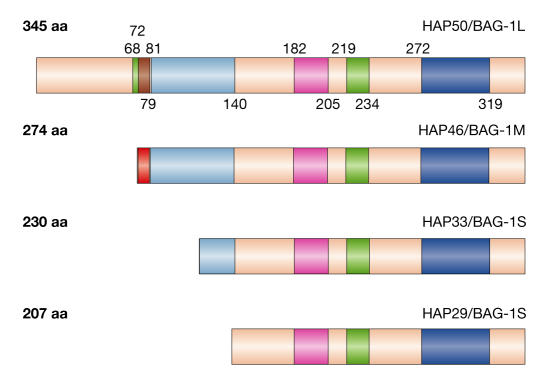

By carefully inspecting human HAP46/BAG-1 cDNAs, Packham et al (1997) discovered the noncanonical translational start codon CUG upstream of the previously identified AUG. This gives rise to a polypeptide of 345 residues; that is, it contains a 71-amino-acid extension (Fig 1) and begins with leucine. This larger form has been detected in human and mouse cell extracts (Packham et al 1997; Takayama et al, 1998; Yang et al, 1998). The apparent molecular size is ∼50 kDa, hence the name HAP50 or BAG-1L (BAG-1-long). The amino-terminal end is rich in arginine, therefore raising the calculated pI from 5.1 in HAP46/BAG-1 to 8.3. A notable feature of human and mouse HAP50/BAG-1L is a cluster of basic residues (positions 68–79) that is characteristic of contiguous nuclear-localization signals (NLSs). To distinguish better the isoforms, human HAP46 was then named BAG-1M in which the M stands for medium (Takayama et al, 1998). Smaller isoforms, often called BAG-1S, originate from AUG codons further downstream. The main difference between human and mouse mRNAs is that the latter do not contain the AUG codon that gives rise to human HAP46/BAG-1M. Instead, an intermediate form originates from a start codon further downstream (Packham et al 1997; Takayama et al, 1998) and is shorter by 55 residues. This is the original mouse Bag-1 (Takayama et al, 1995), which corresponds to human HAP33 (Fig 1). Generally, this form is present in cells at higher concentration than other forms. Importantly, all isoforms contain the same C-terminal BAG domain and interact equally with HSP70s to affect their chaperoning activities.

Figure 1.

Isoforms of human HAP46/BAG-1M and domain structure. Green: potential nuclear localization signal (NLS) (SV40 large T and nucleoplasmin types). Red: DNA-binding domain (appears brown in HAP50/BAG-1L owing to overlap with the potential NLS). Sequence in HAP46/BAG-1M:(1)MKKKTRRRST(10). Light blue: acidic hexa-repeat domain (consensus sequence Thr-Arg-Ser-Glu-Glu-X). Pink: ubiquitin-like domain. Dark blue: BAG domain, which is depicted here as originally defined by Takayama et al (1999).

HAP50/BAG-1L enhances androgen-receptor action (Knee et al, 2001). This requires the BAG domain, so HSP70s are involved. HAP50/BAG-1L also cooperates with the vitamin D receptor, but the measured response has been variable (Guzey et al, 2000; Witcher et al, 2001). The N-terminal portion of HAP50/BAG-1L is required for in vitro binding to the vitamin D receptor and HAP46/BAG-1M does not interact (Witcher et al, 2001).

Intracellular localization and expression

The effects of HAP46/BAG-1M on protein folding indicate that it is localized in the cytosol and this has now been established by different experimental approaches (Takayama et al, 1998; Zeiner et al, 1999; Nollen et al, 2000; Knee et al, 2001). For example, HeLa cells that express HAP46/BAG-1M coupled to the green fluorescent protein showed fluorescence that was equally distributed between the cytoplasm and the nucleus at 37 °C. However, exposing the same cells to heat shock resulted in redistribution of the protein to the nucleus, which is a response that has been seen with several cell types (Zeiner et al, 1999). The potential bipartite NLS of HAP46/BAG-1M (Fig 1) possibly becomes active only under specific conditions, such as heat stress. By contrast, HAP50/BAG-1L is almost exclusively localized in the cell nucleus at 37°C (Packham et al, 1997; Takayama et al, 1998; Knee et al, 2001; Niyaz et al, 2001).

Even though the BAG-1 gene is expressed differentially in various mammalian tissues it is expressed minimally in almost all cell types. Notable changes in tissue distribution were observed during early mouse development (Crocoll et al, 2000), which are undoubtedly biologically significant. It will be exciting to see what developmental defects are observed in mice in which the BAG-1 gene is disrupted.

Expression of the BAG-1 gene is often increased in cancer cells relative to normal cells and the levels of the isoforms also differ. In general, there is a rough correlation between HAP46/BAG-1 protein levels and cell proliferation, which indicates that it might be suitable as a prognostic marker (Townsend et al, 2003a). High levels in tumour cells might be due to increased expression of the BAG-1 gene by p53 mutants (Yang et al, 1999).

DNA binding and transcriptional stimulation

The N-terminal end of HAP46/BAG-1M contains a prominent cluster of basic residues that was thought to interact with other molecules. Indeed, HAP46/BAG-1M readily binds to DNA even though the protein as a whole is acidic. Neither the origin of the DNA nor its size is important, although a minimum length is required. In addition, not only linear fragments but also supercoiled plasmid DNA bind to the protein, which indicates a lack of sequence specificity (Zeiner et al, 1999; Niyaz et al, 2003). The deletion of ten N-terminal residues abolished DNA binding. HAP46/BAG-1M can simultaneously interact with DNA and HSP70s, yielding trimeric complexes of the type DNA•HAP46/BAG-1M•HSP70 (Zeiner et al, 1999; Niyaz et al, 2003) in which the substrate-binding site of HSP70/HSC70 remains available for further interactions. The large form HAP50/BAG-1L contains the same basic DNA-binding region, although this overlaps with a putative NLS (Fig 1).

To analyse further the DNA-binding region, the three lysines (positions 2–4) and the three arginines (positions 6–8) in HAP46/BAG-1M were exchanged en bloc for neutral residues (Zeiner et al, 1999; Schmidt et al, 2003). In both cases, DNA binding was destroyed, which indicates that some basic residues within both clusters are essential.

HAP46/BAG-1M supplemented with a nuclear extract stimulates in vitro transcription independent of whether prokaryotic or eukaryotic templates are used or whether these contain promoter elements (Zeiner et al, 1999; Niyaz et al, 2003). The transcripts have no distinct length, which indicates random initiation. Termination probably occurs at the end of linearized DNAs. Transcriptional stimulation also occurs in intact cells when HAP46/BAG-1M is translocated to the nucleus owing to heat stress. Whereas heat shock drastically diminishes general message levels in normal cells, the overexpression of HAP46/BAG-1M almost reverses this, and the induction of HSP70 and HSP40 is enhanced (Zeiner et al, 1999). The expression of the BAG-1 gene, however, is unaltered by this treatment (Townsend et al, 2003b). Transcription is similarly stimulated in cells that overexpress HAP50/BAG-1L, and this mainly affects endogenous genes that are subject to regulation rather than highly expressed genes, such as those that encode actin or tubulin (Niyaz et al, 2001). The stimulatory effect is apparently specific for RNA polymerase II.

To test whether HSP70s participate in transcriptional stimulation, the BAG domain was deleted from HAP46/BAG-1M and stimulation was greatly diminished as a result (Niyaz et al, 2003). This delineates a new cellular function of the HSP70 system in transcription and corresponds to the proposed involvement of HSP70 in chromatin remodelling (Schmidt et al, 2003). It might be relevant, however, that the above deletion variant still produced some stimulation, which indicates that this process involves not only the BAG domain of HAP46/BAG-1M but also, possibly, the DNA-binding domain.

HAP46/BAG-1M interacts with transcription factors

To find a biochemical reason for the effect on transcription, a series of transcription factors was studied. Several steroid hormone receptors, cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB) and core binding factor (CBFA1/RUNX2) readily associated with HAP46/BAG-1M when HSC70 was present, but these interactions were destroyed by ablating the BAG domain (Niyaz et al, 2003). This is clear evidence for the involvement of HSP70/HSC70. For glucocorticoid receptors, this observation confirmed previous data (Schneikert et al, 2000), whereas it was the first direct evidence of trimeric complexes of oestrogen receptors containing HSC70 (Niyaz et al, 2003).

These data do not exclude the possibility that HAP46/BAG-1M interacts with other transcription factors independent of HSP70s, as was observed for the homeodomain factor GAX (Niyaz et al, 2003). The vitamin D receptor is another candidate for direct interaction, as binding to HAP50/BAG-1L required the N-terminal part in addition to the BAG domain (Guzey et al, 2000; Witcher et al, 2001). Therefore, there are two different types of interaction between transcription factors and the transcriptionstimulating protein HAP46/BAG-1M.

Possible mechanism for transcriptional stimulation

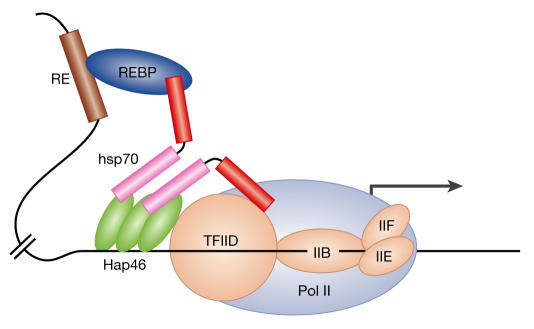

The above observations can be incorporated into a model that explains the transcription-stimulating effect of HAP46/BAG-1M (Fig 2). It postulates that HAP46/BAG-1M binds to DNA in areas of active chromatin and, through HSP70s as bridging molecules, recruits transcription factors and possibly other components of the transcription machinery into functional complexes. This might then affect the expression of the respective gene.

Figure 2.

Model depicting possible chaperoning of the transcriptional apparatus to DNA by HAP46/BAG-1M along with HSP70. A simplified version of the initiation complex is shown with, arbitrarily, three molecules of HAP46/BAG-1M bound to DNA. RE, response element on DNA; REBP, specific response-element binding protein.

Figure 2 assumes that an enhancer protein, such as a steroid receptor, bound to its cognate response element serves as an anchoring component on DNA and forms complexes with HAP46/BAG-1M that involve HSP70s. In this way, long stretches of DNA can be bridged. Other molecules of HAP46/BAG-1M further communicate with the transcription machinery by establishing contact either directly or through HSP70s with the basal transcription factor TFIID and/or RNA polymerase II. Some of these interactions might be transient. The model points to a complex array of interactions of HAP46/BAG-1M with the transcription apparatus and opens up the possibility of mutual potentiation as well as competition. In a similar manner, HAP46/BAG-1M could potentially lead to the repression of transcription of some active genes. The mechanistic details of the effects of HAP46/BAG-1M on transcription are unknown, particularly in view of the fact that ATP and ADP levels affect the protein-binding properties of HSP70 chaperones (Mayer et al, 2001).

Physiology

In terms of biology, HAP46/BAG-1M behaves like a chameleon, acting both as a transcriptional stimulator and an HSP70 co-chaperone. It forms a stoichiometric complex with HSP70/HSC70 so that equal concentrations are needed to block protein folding. However, HAP46/BAG-1M is normally present at much lower levels than HSC70, making complete inhibition of folding activity unlikely (Nollen et al, 2000). Conversely, in the nucleus, even low levels of HAP46/BAG-1M together with HSP70s might affect transcription. The same applies to HAP50/BAG-1L. There should be well-balanced equilibria in cells under heat or other kinds of stress when excessive amounts of misfolded proteins require chaperoning by cytosolic HSC70. The translocation of HAP46/BAG-1M to the nucleus would release any inhibitory effect on cytosolic chaperoning that could otherwise be operating. HAP46/BAG-1M might therefore act differently depending on physiological conditions and intracellular localization.

In contrast to HAP46/BAG-1M and HAP50/BAG-1L, shorter forms do not contain the basic amino-acid clusters and consequently do not bind to DNA. They function as negative or positive regulators of protein folding depending on specific conditions (Lüders et al, 2000b; Nollen et al, 2000; Gässler et al, 2001). As they contain a potential NLS (Fig 1), they translocate to the nucleus after heat shock (Townsend et al, 2003b).

Steroid receptors were the first transcription factors found to form complexes with HAP46/BAG-1M, and HSP70s clearly mediate these interactions. Transcriptional activation by androgen and oestrogen receptors is enhanced by HAP50/BAG-1L but not by HAP46/BAG-1M (Knee et al, 2001; Cutress et al, 2003), probably because HAP46/BAG-1M is largely cytosolic under normal conditions whereas HAP50/BAG-1L is nuclear. However, under heat stress, HAP46/BAG-1M might similarly stimulate the response to androgen and oestrogen. The effects of HAP46/BAG-1M on glucocorticoid responses are complex. One group found that the overexpression of HAP50/BAG-1L in several cell types promoted glucocorticoidstimulated expression of a reporter construct and of the receptor gene itself (Niyaz et al, 2001). Others have described a negative effect of HAP46/BAG-1M on glucocorticoid-receptor actions. Overexpression of HAP46/BAG-1M reduced receptor binding to DNA and caused decreased hormonal response (Kullmann et al, 1998) with both DNA binding and BAG domains being involved (Schneikert et al, 2000; Schmidt et al, 2003). Such variations in response are possibly the result of using different experimental systems in which either potentiation or inhibition of transcription might prevail (see above).

Overexpression of HAP46/BAG-1M and its isoforms protects various cell types from heat-induced apoptosis (Takayama et al, 1997; Zeiner et al, 1999; Niyaz et al, 2001; Townsend et al, 2003b), possibly through the enhanced induction of HSP70 and HSP40 (Zeiner et al, 1999). Related to this is the increased growth-factor-dependent proliferation of various cells by HAP46/BAG-1 (Townsend et al, 2003a) and the rescue of lymph cells from glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Kullmann et al, 1998). Cell-protective effects that counterbalance such diverse insults might be due to a stimulation of general transcription and/or enhanced expression of specific genes by HAP46/BAG-1M and HAP50/BAG-1L. In addition, HAP46/BAG-1M might arrest cell death by inhibiting protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), which is associated with the cellular stress response protein GADD34 (Hung et al, 2003).

Unresolved problems

Apart from the DNA binding and BAG domains, the functions of the remaining portions of HAP46/BAG-1M are largely unknown. The protein harbours a region of ten acidic hexa-repeats (including one degenerated sequence), whereas HAP33/BAG-1S has only four such repeats. Even though this region may be phosphorylated, this does not affect activity, at least not with respect to steroid-receptor action and binding to HSP70s (Schneikert et al, 2000). Deletion of the hexa-repeat region neither destroyed transcriptional stimulation by HAP46/BAG-1M (Niyaz et al, 2003) nor glucocorticoid-receptor-dependent transcription in transfected cells (Schmidt et al, 2003). Mouse HAP50/BAG-1L contains only six acidic repeats, which are also less conserved.

Moreover, the ubiquitin-like region (Fig 1) remains mysterious. It is much shorter than ubiquitin itself and interacts with proteasomes (Lüders et al, 2000a). Conjugation with ubiquitin normally primes proteins for degradation by proteasomes, but HAP46/BAG-1M has a relatively long half-life despite the fact that it is ubiquitylated (Alberti et al, 2002). Whereas the prevention of stress-induced growth inhibition by HAP46/BAG-1M and its isoforms requires a conserved lysine in the ubiquitin region (Townsend et al, 2003b), it is dispensable for the action of HAP50/BAG-1L on androgen receptors (Knee et al, 2001) and of HAP46/BAG-1M on transcription (Y Niyaz, unpublished data).

An exciting question is how HAP46/BAG-1M and HAP50/BAG-1L affect transcription mechanistically. In the context of Figure 2, it will be important to identify the component(s) of the transcriptional apparatus they interact with and whether HSP70s are involved. Mutational analysis will then help to establish biochemical details and functional significance. It will also be important to investigate a more extended panel of transcription factors for their ability to interact with HAP46/BAG-1M.

A key problem concerns the cellular expression of HAP46/BAG-1M and HAP50/BAG-1L. High levels in various cancer cells probably relate to enhanced survival under the adverse and stressful conditions that prevail in tumours and during antitumour treatments. Cells that express a lot of the BAG-1 gene might be selected for, but defective mutations, particularly in the DNA and BAG domains, might not have immediate selective advantages. A range of cell survival factors have been found to upregulate the BAG-1 gene in various cell types (Townsend et al, 2003a). Also multidrug-resistant cells that are less sensitive to apoptosis compared with their normal counterparts express higher levels of HAP46/BAG-1M and HAP33/BAG-1S (Ding et al, 2000), and downregulation of these genes slowed HeLa cell growth (Takahashi et al, 2003). Therefore, it will be helpful in the treatment of cancer if levels of HAP46/BAG-1M and HAP50/BAG-1L could be decreased by specific agents or external treatments. Indeed, protein-kinase inhibitors, such as genistein and flavopiridol, and the immunosuppressant rapamycin, downregulate the BAG-1 gene (Adachi et al, 1996; Kullmann et al, 1998; Kitada et al, 2000). However, decreased levels of HAP50/BAG-1L caused HeLa cells to be less sensitive to anticancer drugs (Takahashi et al, 2003). The full importance of HAP46/BAG-1M and its isoforms in the development of various cancers is far from clear, and it is to be hoped that these recent data will stimulate further research in this area.

Acknowledgments

I apologize to those colleagues whose work I was unable to cite owing to space limitations and I am grateful to P. Henrich for help with the figures.

References

- Adachi M, Sekiya M, Torigoe T, Takayama S, Reed JC, Miyazaki T, Minami Y, Taniguchi T, Imai K (1996) Interleukin-2 (IL-2) upregulates BAG-1 gene expression through serine-rich region within IL-2 receptor βc chain. Blood 88: 4118–4123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti S, Demand J, Esser C, Emmerich N, Schild H, Höhfeld J (2002) Ubiquitylation of BAG-1 suggests a novel regulatory mechanism during the sorting of chaperone substrates to the proteasome. J Biol Chem 277: 45920–45927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardelli A, Longati P, Albero D, Goruppi S, Schneider C, Ponzetto C, Comoglio PM (1996) HGF receptor associates with the anti-apoptotic protein Bag-1 and prevents cell death. EMBO J 15: 6205–6212 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehmer D, Rüdiger S, Gässler CS, Klostermeier D, Packschies L, Reinstein J, Mayer MP, Bukau B (2001) Tuning of chaperone activity of hsp70 proteins by modulation of nucleotide exchange. Nat Struct Biol 8: 427–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briknarová K et al. (2001) Structural analysis of BAG1 cochaperone and its interactions with Hsc70 heat shock protein. Nat Struct Biol 8: 349–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brive L, Takayama S, Briknarová K, Homma S, Ishida SK, Reed JC, Ely KR (2001) The carboxy-terminal lobe of hsc70 ATPase domain is sufficient for binding BAG1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 289: 1099–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocoll A, Blum M, Cato AC (2000) Isoformspecific expression of BAG-1 in mouse development. Mech Dev 91: 355–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutress RI et al. (2003) The nuclear BAG-1 isoform, BAG-1L, enhances oestrogen-dependent transcription. Oncogene 22: 4973–4982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Yang X, Pater A, Tang S-C (2000) Resistance to apoptosis is correlated with the reduced caspase-3 activation and enhanced expression of antiapoptotic proteins in human cervical multidrug-resistant cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 270: 415–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froesch BA, Takayama S, Reed JC (1998) BAG-1L protein enhances androgen receptor function. J Biol Chem 273: 11660–11666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gässler CS, Wiederkehr T, Brehmer D, Bukau B, Mayer MP (2001) Bag-1M accelerates nucleotide release for human Hsc70 and Hsp70 and can act concentration-dependent as positive and negative cofactor. J Biol Chem 276: 32538–32544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer M, Zeiner M, Gehring U (1997) Proteins interacting with the molecular chaperone hsp70/hsc70: physical associations and effects on refolding activity. FEBS Lett 417: 109–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer M, Zeiner M, Gehring U (1998) Interference between proteins Hap46 and Hop/p60, which bind to different domains of the molecular chaperone hsp70/hsc70. Mol Cell Biol 18: 6238–6244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzey M, Takayama S, Reed JC (2000) BAG1L enhances trans-activation function of the vitamin D receptor. J Biol Chem 275: 40749–40756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höhfeld J, Jentsch S (1997) GrpE-like regulation of the hsc70 chaperone by the anti-apoptotic protein BAG-1. EMBO J 16: 6209–6216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung WJ, Roberson RS, Taft J, Wu DY (2003) Human BAG-1 proteins bind to the cellular stress response protein GADD34 and interfere with GADD34 functions. Mol Cell Biol 23: 3477–3486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada S, Zapata JM, Andreeff M, Reed JC (2000) Protein kinase inhibitors flavopiridol and 7-hydroxystaurosporine down-regulate antiapoptosis proteins in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 96: 393–397 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knee DA, Froesch BA, Nuber U, Takayama S, Reed JC (2001) Structure–function analysis of Bag1 proteins. Effects on androgen receptor transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem 276: 12718–12724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann M, Schneikert J, Moll J, Heck S, Zeiner M, Gehring U, Cato ACB (1998) RAP46 is a negative regulator of glucocorticoid receptor action and hormone induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem 273: 14620–14625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Takayama S, Zheng Y, Froesch B, Chen G, Zang X, Reed JC, Zang XK (1998) Interaction of BAG-1 with retinoic receptor and its inhibition of retinoic acid-induced apoptosis in cancer cells. J Biol Chem 273: 16985–16992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüders J, Demand J, Höhfeld J (2000a) The ubiquitin-related BAG-1 provides a link between the molecular chaperones hsc70/hsp70 and the proteasome. J Biol Chem 275: 4613–4617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüders J, Demand J, Papp O, Höhfeld J (2000b) Distinct isoforms of the cofactor BAG-1 differentially affect hsc70 chaperone function. J Biol Chem 275: 14817–14823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa S, Takayama S, Froesch BA, Zapata JM, Reed JC (1998) p53-inducible human homologue of Drosophila seven in absentia (Siah) inhibits cell growth: suppression by BAG-1. EMBO J 17: 2736–2747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer MP, Brehmer D, Gassler CS, Bukau B (2001) Hsp70 chaperone machines. Adv Protein Chem 59: 1–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyaz Y, Zeiner M, Gehring U (2001) Transcriptional activation by the human Hsp70-associating protein Hap50. J Cell Sci 114: 1839–1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyaz Y, Frenz I, Petersen G, Gehring U (2003) Transcriptional stimulation by the DNA binding protein Hap46/BAG-1M involves hsp70/hsc70 molecular chaperones. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 2209–2216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollen EAA, Brunsting JF, Song J, Kampinga HH, Morimoto RI (2000) Bag-1 functions in vivo as a negative regulator of hsp70 chaperone activity. Mol Cell Biol 20: 1083–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osipiuk J, Walsh MA, Freeman BC, Morimoto RI, Jochimiak A (1999) Structure of a new crystal form of human hsp70 ATPase domain. Acta Crystallogr 55: 1105–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packham G, Brimmel M, Cleveland JL (1997) Mammalian cells express two differently localized Bag-1 isoforms generated by alternative translation initiation. Biochem J 328: 807–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen G, Hahn C, Gehring U (2001) Dissection of the ATP binding domain of the chaperone hsc70 for interaction with the cofactor Hap46. J Biol Chem 276: 10178–10184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt U, Wochnik GM, Rosenhagen MC, Young JC, Hartl FU, Holsboer F, Rein T (2003) Essential role of the unusual DNA-binding motif of BAG-1 for inhibition of the glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem 278: 4926–4931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneikert J, Hübner S, Langer G, Petri T, Jäättelä M, Reed J, Cato ACB (2000) Hsp70–RAP46 interaction in downregulation of DNA binding by glucocorticoid receptor. EMBO J 19: 6508–6516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondermann H, Scheufler C, Schneider C, Höhfeld J, Hartl F-U, Moarefi I (2001) Structure of a Bag/hsc70 complex: convergent functional evolution of hsp70 nucleotide exchange factors. Science 291: 1553–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Takeda M, Morimoto RI (2001) Bag1–Hsp70 mediates a physiological stress signalling pathway that regulates Raf-1/ERK and cell growth. Nature Cell Biol 3: 276–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Yanagihara M, Ogawa Y, Yamanoha B, Andoh T (2003) Down-regulation of Bcl-2-interacting protein BAG-1 confers resistance to anti-cancer drugs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 301: 798–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S, Sato T, Krajewski S, Kochel K, Irie S, Millan JA, Reed JC (1995) Cloning and functional analysis of BAG-1: a novel Bcl-2-binding protein with anti-cell death activity. Cell 80: 279–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S, Kochel K, Irie S, Inazawa J, Abe T, Sato T, Druck T, Huebner K, Reed JC (1996) Cloning of cDNAs encoding the human BAG1 protein and localization of the human BAG1 gene to chromosome 9p12. Genomics 35: 494–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S, Bimston DN, Matsuzawa S, Freeman BC, Aimesempe C, Xie Z, Morimoto RI, Reed JC (1997) BAG-1 modulates the chaperone activity of hsp70/hsc70. EMBO J 16: 4887–4896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S et al. (1998) Expression and location of Hsp70/Hsc-binding anti-apoptotic protein BAG-1 and its variants in normal tissues and tumor cell lines. Cancer Res 58: 3116–3131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S, Xie Z, Reed JC (1999) An evolutionarily conserved family of hsp70/hsc70 molecular chaperone regulators. J Biol Chem 274: 781–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada K, Mori M (2000) Human DnaJ homologs dj2 and dj3, and bag-1 are positive cochaperones of hsc70. J Biol Chem 275: 24728–24734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend PA, Cutress RI, Sharp A, Brimmell M, Packham G (2003a) BAG-1: a multifunctional regulator of cell growth and survival. Biochim Biophys Acta 1603: 83–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend PA, Cutress RI, Sharp A, Brimmell M, Packham G (2003b) BAG-1 prevents stress-induced long-term growth inhibition in breast cancer cells via a chaperone-dependent pathway. Cancer Res 63: 4150–4157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witcher M, Yang X, Pater A, Tang S-C (2001) BAG-1 p50 isoform interacts with the vitamin D receptor and its cellular overexpression inhibits the vitamin D pathway. Exp Cell Res 265: 167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Chernenko G, Hao Y, Ding Z, Pater MM, Pater A, Tang S-C (1998) Human BAG-1/RAP46 protein is generated as four isoforms by alternative translation initiation and overexpressed in cancer cells. Oncogene 17: 981–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Pater A, Tang SC (1999) Cloning and characterization of the human BAG-1 gene promoter: upregulation by tumor-derived p53 mutants. Oncogene 18: 4546–4553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiner M, Gehring U (1995) A protein that interacts with members of the nuclear hormone receptor family: identification and cDNA cloning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 11465–11469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiner M, Gebauer M, Gehring U (1997) Mammalian protein RAP46: an interaction partner and modulator of 70 kDa heat shock proteins. EMBO J 16: 5483–5490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiner M, Niyaz Y, Gehring U (1999) The hsp70-associating protein Hap46 binds to DNA and stimulates transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 10194–10199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]