Abstract

A major concern in the use of class IIa bacteriocins as food preservatives is the well-documented resistance development in target Listeria strains. We studied the relationship between leucocin A, a class IIa bacteriocin, and the composition of the major phospholipid, phosphatidylglycerol (PG), in membranes of both sensitive and resistant L. monocytogenes strains. Two wild-type strains, L. monocytogenes B73 and 412, two spontaneous mutants of L. monocytogenes B73 with intermediate resistance to leucocin A (±2.4 and ±4 times the 50% inhibitory concentrations [IC50] for sensitive strains), and two highly resistant mutants of each of the wild-type strains (>500 times the IC50 for sensitive strains) were analyzed. Electrospray mass spectrometry analysis showed an increase in the ratios of unsaturated to saturated and short- to long-acyl-chain species of PG in all the resistant L. monocytogenes strains in our study, although their sensitivities to leucocin A were significantly different. This alteration in membrane phospholipids toward PGs containing shorter, unsaturated acyl chains suggests that resistant strains have cells with a more fluid membrane. The presence of this phenomenon in a strain (L. monocytogenes 412P) which is resistant to both leucocin A and pediocin PA-1 may indicate a link between membrane composition and class IIa bacteriocin resistance in some L. monocytogenes strains. Treatment of strains with sterculic acid methyl ester (SME), a desaturase inhibitor, resulted in significant changes in the leucocin A sensitivity of the intermediate-resistance strains but no changes in the sensitivity of highly resistant strains. There was, however, a decrease in the amount of unsaturated and short-acyl-chain PGs after treatment with SME in one of the intermediate and both of the highly resistant strains, but the opposite effect was observed for the sensitive strains. It appears, therefore, that membrane adaptation may be part of a resistance mechanism but that several resistance mechanisms may contribute to a resistance phenotype and that levels of resistance vary according to the type of mechanisms present.

Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria are ribosomally synthesized peptides that show antimicrobial activity in their mature form, usually against a narrow spectrum of closely related species. Several classes have been described, including lantibiotics (class I), small heat-stable non-lanthionine peptides (class II), and large heat-labile bacteriocins (class III). The class IIa bacteriocins are known as “pediocin-like” and show strong antilisterial activity (23, 25). Due to the recurrence of serious listeriosis outbreaks caused by the food-borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes, these class IIa bacteriocins have become a major focus in the search for novel naturally occurring biopreservatives. It is estimated that between 1,100 and 2,500 people in the United States develop listeriosis each year and that 20 to 25% of these Listeria infections are fatal (http://www.fsis.usda.gov; http://www.cdc.gov).

Reduced sensitivity or resistance to these bacteriocins may compromise the antimicrobial efficiency of these peptides. Resistance has been found to be spontaneous or can be induced by exposure to the bacteriocin. Of concern is the relatively high frequency (10−3 to 10−4) at which L. monocytogenes develops resistance to class IIa bacteriocins (33). Mechanisms contributing to class IIa bacteriocin resistance have included factors under the influence of the σ54 factor (34) and σ54-dependent genes, specifically the mannose phosphotransferase system (PTS) permease for Enterococcus faecalis (15, 22) and L. monocytogenes (16) and the mannose PTS enzyme IIAB component of L. monocytogenes sensitivity to leucocin A (32). The upregulation of a β-glucoside-specific PTS has also been reported in pediocin-resistant L. monocytogenes (21).

Class IIa bacteriocins are currently thought to act primarily by permeabilizing the target membrane by the formation of pores. It has been hypothesized that these pores cause leakage of ions and inorganic phosphates and subsequently dissipate the proton motive force (4, 8, 10, 14, 27). The requirement of a receptor-type molecule (5, 37) and a general electrostatic functional binding of these cationic peptides to the anionic head groups of phospholipids in membranes (11, 12, 24, 27) are involved in the mediation of class IIa bacteriocin activity. Further, it has been shown that the lipid composition of the target cell membrane plays an important role in modulating the membrane interaction of the bacteriocin (13, 14). Hydrophobic interactions between the hydrophobic part of the bacteriocin and the lipid fatty acid chains, resulting in insertion, follow the electrostatic binding of the peptide to the membrane (17, 19). This interaction of the bacteriocins with phospholipids has been reported to largely influence membrane permeability (14).

It is also possible that different levels of resistance are associated with different resistance mechanisms. The aim of this study was therefore to elucidate changes associated with bacteriocin resistance by looking at changes occurring in the phospholipid composition, in particular the phosphatidylglycerol (PG) composition of cells with different levels of resistance and a bacteriocin-sensitive strain of the same listerial species. Electrospray mass spectrometry (ESMS) was used as a tool to study phospholipid composition. Sterculic acid methyl ester (SME), a cyclopropene fatty acid previously reported to be a specific inhibitor of the stearoyl coenzyme A desaturase system (36), was used to determine the effect of inhibiting the monodesaturation of fatty acids on the resistance levels to leucocin A.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

L. monocytogenes B73 (leucocin A sensitive) and L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 (leucocin A resistant) have been described previously (32). L. monocytogenes B73-V2 and L. monocytogenes B73-V1 are mutants of the parental L. monocytogenes B73 strain with intermediate resistance to leucocin A and were generated by leucocin A exposure (see below). The pediocin-sensitive L. monocytogenes 412 strain and the pediocin-resistant L. monocytogenes 412P strain have been previously described by Gravesen et al. (21). All L. monocytogenes strains were grown on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar or broth (Biolab, Midrand, South Africa) at 37°C.

Generation of the leucocin-resistant strains L. monocytogenes B73-V1 and B73-V2.

Leucocin A was synthesized as described previously (32). A 1% inoculum of L. monocytogenes B73 was added to BHI broth containing leucocin A at 100 μg/ml. After 36 h, the broth culture was serially diluted and plated on BHI agar plates free of leucocin. Following incubation for 24 h, colonies were selected randomly, and the 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of leucocin A for these colonies were determined by agar well diffusion assay, to assess resistance development. The stability of the phenotype of the selected mutants L. monocytogenes B73-V1 and B73-V2 was monitored over 10 successive subcultures in BHI broth, free of leucocin.

Antilisterial activity determinations.

The IC50 was determined using the agar well diffusion assay, as described by Du Toit and Rautenbach (18), with the following modifications. The cells were not washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, and 0.7% BHI agar was used in the wells. All dose-response data from the agar well diffusion assays was analyzed using Graphpad Prism version 3.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.) as described by Du Toit and Rautenbach (18). A sigmoidal curve with variable slope and constant top of 100 and variable bottom was fitted to each of the data sets by using the equation Y = bottom + (100 − bottom)/[1 + 10(log IC50) × hill slope]. For curve fitting only, the mean value of each data point, without weighting, was considered. The IC50 was calculated from the x value of the response halfway between the top and bottom plateau.

Extraction of L. monocytogenes phospholipids.

L. monocytogenes strains were grown in 1-liter broth cultures to early stationary phase (optical density at 600 nm, 0.7 to 0.75) and were then harvested for phospholipid extraction. Phospholipid was extracted using the Bligh and Dyer method as described by Cabrera et al. (9). Cells were lysed in a sonicating water bath for 2 h, instead of by vortexing. The phospholipid standards (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) used were dimyristoyl-phosphatidylglycerol (DMPG), dioleoyl-phosphatidylglycerol (DOPG), dipalmitoyl-phosphatidylglycerol (DPPG), and distearoyl-phosphatidylglycerol (DSPG).

Inhibition of PG desaturation by sterculic acid methyl ester.

SME, a desaturase inhibitor obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., was prepared and stored in the same way as previously described (36). It was added, to reach a final concentration of 0.025 mM, to a 1% inoculum of the L. monocytogenes strains to be tested, in a broth culture. For the agar diffusion assay, a final concentration of 0.05 mM SME was used in the agar.

Electrospray mass spectrometry.

Mass spectrometry was performed using a Micromass triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization source. Dried phospholipid was diluted with 100 μl of methanol-chloroform (2:1, vol/vol) and then diluted 1:10 with methanol-chloroform (1:1, vol/vol). A 5-μl volume of the sample solution was introduced into the electrospray ionization mass spectrometer via a Rheodyne injector valve. Methanol-chloroform (1:1, vol/vol) was the carrier solvent, delivered at a flow rate of 20 μl/min during each analysis. A capillary voltage of 3.5 kV was applied, with the source temperature at 120°C and the cone voltage at 100 V. Data acquisition was in the negative mode, scanning the first analyzer (MS1) through m/z = 200 to 2,000 at a scan rate of 100 atomic mass units/s. Combining the scans across the elution peak and subtracting the background produced representative scans. For fragmentation analysis, precursor ions were selected in MS1 and product ions were detected in MS 2 after decomposition at a collision energy of 40 eV and with the argon pressure in the collision cell at 0.2 Pa.

Statistical evaluation.

Tukey's comparative test, using Prism 3.0, was used to statistically evaluate all results and to calculate significant differences in the ratios of unsaturated and short-acyl-chain fatty acid species between the susceptible and resistant strains. P values for the dose-response curves were also generated using this method.

RESULTS

Antilisterial activity determinations.

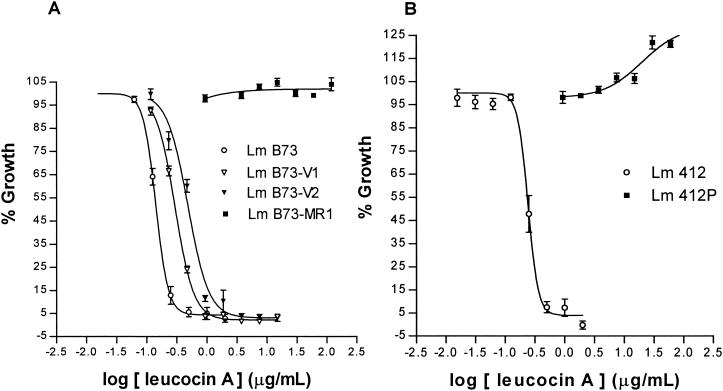

L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 showed no decrease in growth with increasing concentrations of leucocin A up to 120 μg/ml (the maximum concentration in our assay) (Fig. 1). However, the other highly leucocin-resistant strain, L. monocytogenes 412P, showed an unexpected increased in growth (±30%) with increasing concentrations of leucocin A (Fig. 1). This increase in growth may be an indication of a strain-specific resistance response. This strain was selected under pediocin-PA1 pressure and showed cross-resistance to leucocin A.

FIG. 1.

(A) Dose-response of leucocin A-sensitive L. monocytogenes B73, intermediate-resistance mutants L. monocytogenes B73-V1 and L. monocytogenes B73-V2, and highly leucocin-resistant L. monocytogenes B73-MR1. (B) Dose-response of pediocin PA-1- and leucocin A-sensitive L. monocytogenes 412 and the highly pediocin PA-1- and leucocin A-resistant L. monocytogenes 412P. The 100% growth level was taken as the growth of each strain in the absence of leucocin A. Data are a combination of the results of duplicate experiments. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean for each concentration value (eight determinations).

The shifting of the dose-response curves (Fig. 1) of the two spontaneous mutant strains, L. monocytogenes B73-V1 and B73-V2, to the right indicated their increased resistance to leucocin A. The IC50s (Table 1) of leucocin A for L. monocytogenes B73-V1 and B73-V2 indicate that these strains are ±2.4 times and ±4 times more resistant, respectively, to leucocin A than is L. monocytogenes B73. According to Tukey's comparison test, the strains with intermediate resistance to leucocin A had a significantly different response from that of L. monocytogenes B73 (leucocin susceptible) (P < 0.001). The IC50s for L. monocytogenes 412 and B73 have also been determined to be significantly different (P < 0.001). In keeping with the nomenclature for vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (6), we have referred to L. monocytogenes B73-V1 and B73-V2 as intermediate leucocin resistant strains.

TABLE 1.

IC50s of leucocin A for the L. monocytogenes strains testeda

| L. monocytogenes strain | Leucocin A IC 50 (μg/ml) (95% confidence range) |

|---|---|

| B73 | 0.14 (0.13-0.16) |

| B73-V1 | 0.30 (0.28-0.31) |

| B73-V2 | 0.49 (0.39-0.60) |

| B73-MR1 | >100 |

| 412 | 0.24 (0.22-0.27) |

| 412P | >100 |

Two independent experiments were performed, and each concentration was determined in quadruplicate per experiment.

Due to the limited amount of leucocin A available, we did not determine its IC50s for the two highly resistant strains. It has, however, been determined that L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 is more than 1,000 times as resistant as L. monocytogenes B73, while L. monocytogenes 412P is more than 500 times as resistant as L. monocytogenes 412P, using the maximum concentration of 120 μg of leucocin A per ml. L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 and L. monocytogenes 412P have subsequently been referred to as highly leucocin resistant.

ESMS identification and profiles of phospholipids of L. monocytogenes strains.

Correlating the fragmentation mass spectra of standard PGs with that of the L. monocytogenes PG fragmentation patterns allowed the identification of the fatty acyl moieties in the observed PG species (Table 2). Our data correlated with the fragmentation data reported for PGs from Bacillus (7). The identification of the fatty acyl moieties of the PG species (Table 2) as mainly C14, C15, C16, and C17 is also corroborated by the findings of Mastronicolis et al. (28) in their study of the diversity of the polar lipids of L. monocytogenes.

TABLE 2.

Molecular species of PG and the corresponding fatty acid species from L. monocytogenes strains, identified by ESMS in negative-ion mode

| [M − H]−m/z | Calculated atomic mass (Da) | Fatty acyl combinations |

|---|---|---|

| 678 | 678.88 | C15:1/C14 |

| 680 | 680.89 | C15/C14 |

| 692 | 692.91 | C16:1/C14 |

| 694 | 694.92 | C16/C14 |

| 706 | 706.93 | C15/C16:1 |

| 708 | 708.95 | C15/C16 |

| 722 | 722.97 | C15/C17 |

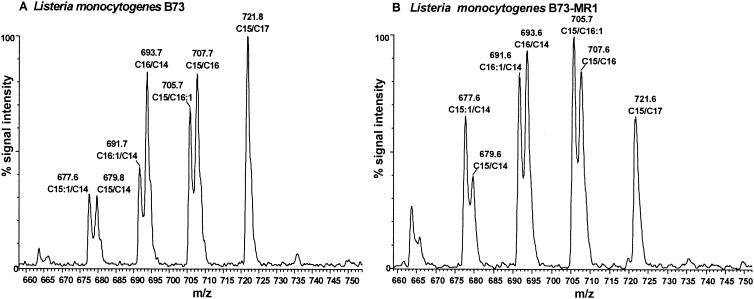

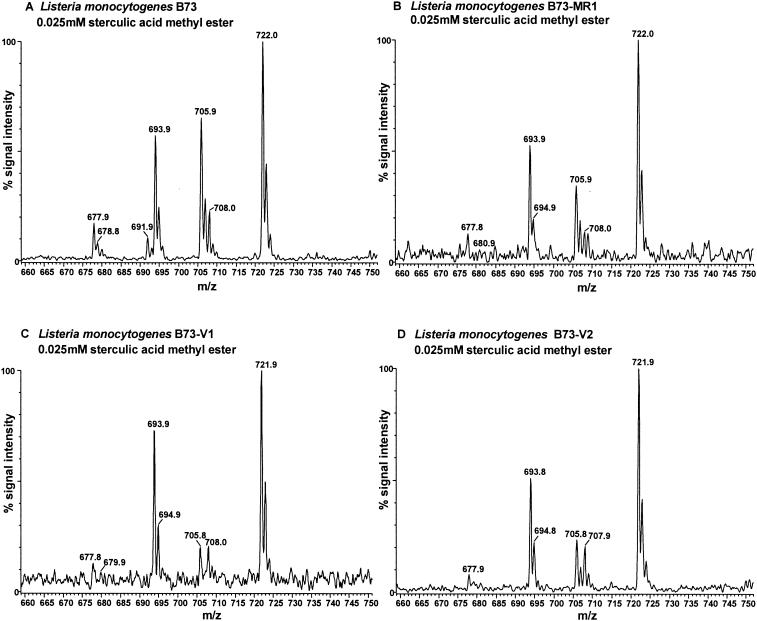

ESMS spectra of the phospholipids of all the L. monocytogenes strains (Fig. 2) showed the abundant presence of PG, the major phospholipid of L. monocytogenes (20, 26). The ESMS spectrum in Fig. 2A is representative of pediocin-sensitive L. monocytogenes strain and the spectrum in Fig. 2B represents the general profile found for the leucocin intermediate resistant and pediocin-resistant strains analyzed in this study. Approximately four major PG molecular species are observed in the ESMS data (Fig. 2), and these are found in both the saturated and unsaturated forms. In the sensitive L. monocytogenes B73 strain, the PG species with m/z 722, correlated with PG containing C15 and C17 fatty acid chains, was the most abundant (Fig. 2A). The PG containing C15 and C16:1 (m/z 706) was the most abundant in highly resistant and intermediate resistant strains (Fig. 2B). Similar differences were found between the L. monocytogenes 412 and 412P strains. It is apparent that the resistant strains seem to have an observable increase in PGs containing an unsaturated fatty acyl chain.

FIG. 2.

ESMS spectrum of the PG region of L. monocytogenes B73 (leucocin sensitive) (A) and L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 (highly resistant) (B). The ESMS data for L. monocytogenes B73 are representative of L. monocytogenes 412 too, and the ESMS data of L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 are representative of the intermediate-resistance strains and L. monocytogenes 412P.

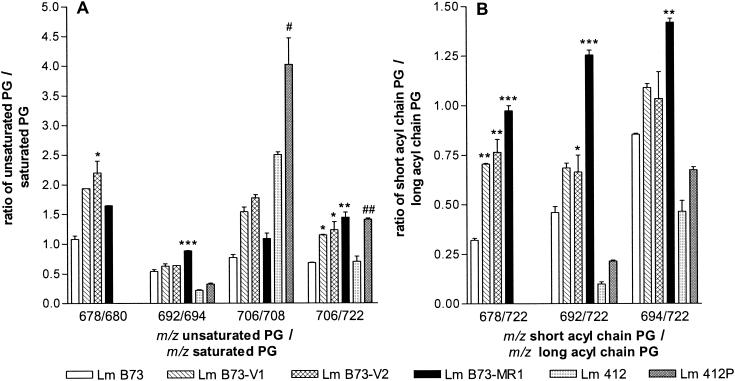

Saturation differences of PGs.

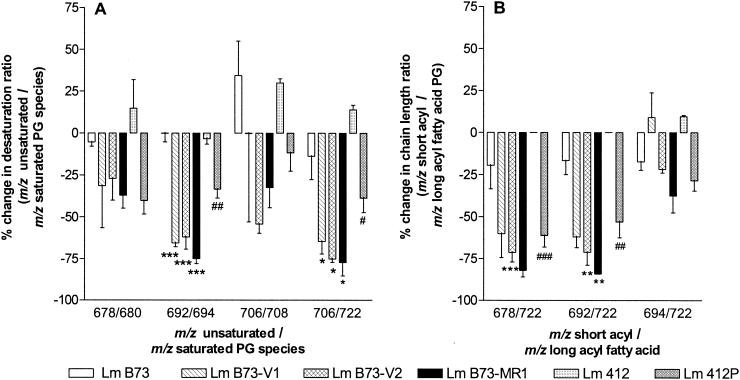

The ratios of the unsaturated to saturated molecular species of PG for all the resistant strains (Fig. 3A) were higher than those in the sensitive strains. Although the resistant strains have an increased level of the unsaturated PG component, there is no clear correlation with the resistance level. For example, the unsaturated/saturated PG ratios were greater for the intermediate-resistance strains (Fig. 3A) than for the highly resistant strains for both [m/z 678]/[m/z 680] and [m/z 706]/[m/z 708]. This change, however, correlates with increasing levels of resistance in the intermediate-resistance strain group (Fig. 3A). There was also a significant increase (P < 0.05) in the unsaturated PG species (m/z 706) in comparison to the major PG species (m/z 722), for the intermediate-resistance strains, and this increase is more significant than that for the highly resistant L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 strain.

FIG. 3.

PG composition of L. monocytogenes sensitive, (strains B73 and 412), intermediate-resistance (strains B73-V1 and B73-V2), and highly resistant (strains B73-MR1 and Lm 412P) strains depicted as ratios of unsaturated PGs to saturated PGs (A) and short-acyl-chain PGs to the long-acyl-chain PG (m/z = 722), (B). Statistical comparison between L. monocytogenes B73 and its resistant strains: ∗, P < 0.05, ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001; comparison between L. monocytogenes 412 and 412P: #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01. Note that only one value for 678/680 was determined for L. monocytogenes B73-V1 and so it could not be statistically compared.

Differences in fatty acyl chain length in PGs.

More short-acyl-chain PGs than the PG species with m/z 722 were observed for the intermediate-resistance and highly resistant strains (Fig. 3B). L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 contained more of all short-acyl-chain PGs, specifically the species with m/z 692, than did the intermediate-resistance strains (Fig. 3B). It is, however, difficult to detect a clear correlation between the level of resistance and amounts of short-acyl-chain PGs, considering that the highly resistant strains are at least 200 times more resistant than the intermediate-resistance strains.

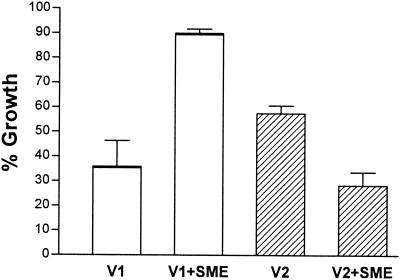

IC50 determinations for SME-treated cells.

SME has been used previously as a desaturase inhibitor in prokaryotes (36). A final concentration of 0.025 mM in broth was determined to be most favorable since it caused no significant growth inhibition (data not shown). No significant growth inhibition was found with 0.05 mM SME in agar, while inhibition was observed with 0.05 mM SME in broth. The higher tolerance to the inhibitor could probably be attributed to decreased diffusion in a solid (agar) environment. The sensitivity of L. monocytogenes B73 to leucocin A was not affected by the presence of SME (data not shown). The inhibitor, however, affected the response of the two intermediate-resistance strains to leucocin A (compare Table 1 and Fig. 3). The 2-fold-resistant L. monocytogenes B73-V1 displayed an unexpected 2.5-fold increase in resistance at 0.33 μg of leucocin A per ml (compare Table 1 and Fig. 4). The fourfold-resistant L. monocytogenes B73-V2 displayed a decrease of ±50% in resistance (compare Table 1 and Fig. 4) to leucocin A at 0.65 μg/ml. No decrease in resistance was observed for the highly resistant L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 at the maximum of 2.6 μg/ml leucocin A concentration. We did not determine IC50s for the highly resistant strains in the presence of SME due to the limited availability of leucocin A.

FIG. 4.

Influence of SME on the leucocin A resistance of intermediate-resistance L. monocytogenes strains. L. monocytogenes B73-V1 and B73-V2 were incubated for 17 h with 0.33 and 0.65 μg of leucocin A per ml, respectively, without (control) or with 0.05 mM SME added to the growth media. The 100% growth level was taken as growth in the absence of leucocin A, without (control) or with 0.05 mM SME added to the growth media. Data are a combination of results of duplicate experiments. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean for eight determinations. Means are significantly different (P < 0.0005) between the SME-treated and nontreated cultures.

Changes in PG composition of cells treated with SME.

The desaturase inhibitor affected the sensitive and the intermediate-resistance and highly resistant strains in different ways. The PG profiles in Fig. 5A and B are representative of the pediocin-sensitive L. monocytogenes 412 and the resistant L. monocytogenes 412P strains, respectively, after addition of desaturase inhibitor. The major difference exhibited in phospholipid profiles of SME-treated highly resistant strains was the replacement of the unsaturated PG (m/z 706) by a saturated PG (m/z 722) as the major PG (Fig. 5B). This result indicated that the precursor PG species might have been channeled into an alternative reaction in which an extra methyl group was added, because the desaturation reaction was inhibited.

FIG. 5.

ESMS spectrum of the PG region of L. monocytogenes B73, B73-V1, B73-V2, and B73-MR1 after treatment with SME. The spectral data for L. monocytogenes B73 are similar to those for L. monocytogenes 412, and the data for L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 are similar to those for L. monocytogenes 412P.

ESMS profiles (Fig. 5C and D) and percent change (Fig. 6A) of the intermediate-resistance strains show the significant decreases in the levels of two unsaturated PGs species, namely, the m/z 706 (P < 0.05) and m/z 692 (P < 0.001) species.

FIG. 6.

Percent change in the ratio of unsaturated to saturated PGs (A) and in the ratio of short-acyl-chain to long-acyl-chain PGs (B) after treatment with 0.025 mM SME in L. monocytogenes strains. The means and standard deviations from for independent experiments are given. Comparison between L. monocytogenes B73 and its resistant strains: ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001. Comparison between L. monocytogenes 412 and the resistant L. monocytogenes 412P: #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01.

The percent decrease for all the L. monocytogenes B73 resistant strains was greater than 50% for the unsaturated PG species with m/z 692 and m/z 706. We found no significant difference between the intermediate-resistance and highly resistant strains in the percent change of unsaturated/saturated PG ratios. L. monocytogenes B73 showed the opposite effect, namely, an increase in the unsaturated PG/saturated PG ([m/z 706]/[m/z 708]) ratio and very small decreases in the rest of the unsaturated/saturated PG ratios analyzed (Fig. 6A). The sensitive L. monocytogenes 412 strain also showed the opposite effect to that observed for L. monocytogenes 412P, namely, significant (P < 0.05) increases in several unsaturated PG/saturated PG ratios ([m/z 706]/[m/z 708], [m/z 678]/[m/z 680], and [m/z 706]/[m/z 722]). After multiple assessments, inconclusive data for the PG ratio [m/z 706]/[m/z 708] in L. monocytogenes B73-V1 were found (error bar in Fig. 6A).

SME also had an influence on the length of the esterified fatty acids in the PG population. The intermediate-resistance strain, L. monocytogenes B73-V1, showed a possible increase in the short-acyl/long-acyl fatty acid PG ratio ([m/z 694]/[m/z 722]) after treatment with SME (Fig. 6B). Again, the highly resistant L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 displayed the largest decreases in the short-acyl/long-acyl chain PG ratios (Fig. 6B). L. monocytogenes B73 showed less than a 25% decrease for all the short-acyl/long-acyl chain PG ratios determined. The resistant strains showed a greater than 50% decrease in the ratios of [m/z 678]/[m/z 722] PG and [m/z 692]/[m/z 722] PG (Fig. 6B). The sensitive L. monocytogenes 412 strain showed no change in the [m/z 678]/[m/z 722] and [m/z 692]/[m/z 722] ratios and an increase in the [m/z 694]/[m/z 722] ratio, with L. monocytogenes 412P showing decreases in the same ratios.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that there are significant differences in the PG content of class IIa bacteriocin-resistant L. monocytogenes strains compared to the wild type. Differences in the PG composition of the resistant L. monocytogenes cell membrane include an increase in the concentration of unsaturated fatty acyl chains of PG, as well as an increase in the concentration of short acyl chains of PG, for all the leucocin-resistant strains. Both of these phospholipid adaptations should result in an increase in membrane fluidity. In contrast to our findings that resistant strains have larger amounts of desaturated and shorter PGs in their membranes (indicating more fluid membranes), it has been shown that nisin-resistant L. monocytogenes has a more rigid membrane (29, 30, 31). Verheul et al. (35), however, observed no differences in fatty acid content between nisin-resistant and -sensitive Listeria strains. Chen et al. (13) also reported that the saturation state of the PG acyl chains in vesicles had little effect on the binding affinity of pediocin PA-1 for the vesicle. However, their fluorescence results indicated that the penetration of the bacteriocin into a bilayer of the saturated dimyristoyl-phosphatidylglycerol was deeper than into a bilayer of unsaturated DOPG (13). The DOPG is therefore thought to be less favorable for efficient membrane permeabilization due to its higher fluidity. A weaker insertion ability of class IIa bacteriocins into unsaturated PG could point to the role of increased amounts of unsaturated PGs in the membranes of resistant strains. In contrast, the larger amounts of longer and saturated PGs in the sensitive L. monocytogenes B73 and 412 strains may enhance membrane insertion by bacteriocin and thus increase sensitivity. A less fluid membrane has also been shown to be a factor influencing the resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to the cationic antimicrobial peptide thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein (3). Similar to our findings, it has been observed that Kluyveromyces lactis mutant cells with reduced amphotericin B sensitivity have a higher unsaturated fatty acid/saturated fatty acid ratio than do wild-type K. lactis cells (38). It is also known that the increased levels of monounsaturated fatty acids in the membrane phospholipid influence the overall decrease in the membrane molecular order (38). These findings indicate the significant roles played by unsaturated phospholipids and membrane fluidity in antibiotic or antimicrobial peptide association with membranes and consequently in resistance mechanisms. Membrane fluidity could be an important contributing factor to class IIa bacteriocin resistance by affecting the insertion of these bacteriocins into the membrane and consequently the formation and stability of pores. Any increase in membrane fluidity could decrease class IIa bacteriocin insertion into the phospholipid membrane and pore or permeability complex stability and could therefore contribute to resistance.

By treating strains with SME, a putative inhibitor of Listeria desaturase, we were able to determine a possible correlation between unsaturated PGs and resistance of L. monocytogenes to class IIa bacteriocins. Desaturase enzymes are responsible for the production of unsaturated acyl chains in phospholipids. SME has reportedly been used as a desaturase inhibitor in prokaryotes (36). In our study we saw a marked influence of the inhibitor on the PG phospholipid composition of L. monocytogenes. The levels of the major unsaturated PG molecular species, m/z 692 and m/z 706, were decreased in the resistant strains. The percent decrease of unsaturated/saturated PG ratios in the highly resistant strains was greater than in the intermediate-resistance strains and significantly different from that in the sensitive strains. Sensitive strains showed small decreases and even increases in unsaturated/saturated PG ratios after addition of the desaturase inhibitor.

Our results indicated that the resistant L. monocytogenes probably contains an SME-sensitive desaturase while the sensitive strains probably contain a less responsive desaturase. The only bacterial desaturase (except for those in cyanobacteria) described to date has been the Bacillus subtilis Δ5 desaturase (1). No significant homologues to the Bacillus desaturase were found after scanning the L. monocytogenes genome (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/Listilist/index.html.). A two-component signal transduction system for this single desaturase in B. subtilis was also described recently (2). The environment finely controls this two-component signal transduction system. Unsaturated fatty acids reportedly act as negative signaling molecules of des (desaturase gene) transcription (2). A similar system could exist for the control of the desaturase activity in L. monocytogenes.

One of the strains, L. monocytogenes B73-VI, displaying intermediate resistance, showed an anomalous response to SME. Rather than the expected increase in leucocin A sensitivity, it became 2.5 times more resistant after treatment. The PG profile of this strain also showed some anomalies after treatment; for example, we found both increases and decreases in the levels of the major unsaturated PG (m/z 706) and a possible increase in the level of the major short-acyl-chain PG (m/z 694) in different culture batches of this strain. This could mean that the mechanism involved in membrane adaptation of this strain is highly sensitive to extremely small changes in its lipid metabolism and/or culture conditions. It is also possible that some undetected membrane adaptation, occurring after SME treatment, may be important in the increased resistance of L. monocytogenes B73-V1. L. monocytogenes B73-V2, however, showed the expected increase (±50%) in leucocin A sensitivity with SME treatment, which coincided with decreases in the levels of unsaturated and short-acyl-chain PGs. This may indicate that both the levels of unsaturated PGs and short-acyl-chain PGs and therefore the activity of a desaturase and fatty acid elongation and branching may influence the resistance of this particular strain.

We did not observe a decrease in resistance after addition of the desaturase inhibitor to the highly resistant L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 strain. However, analysis of the PG profiles of L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 showed no significant differences from those of the intermediate-resistance L. monocytogenes B73-V2 strain after inhibitor addition. It is apparent from this result that an additional factor(s), besides increases in the levels of short-acyl-chain and unsaturated PGs, also contributes to resistance in the highly resistant cells.

In summary, our findings indicate that there is an association between increased amounts of unsaturated and short-acyl-chain PGs in cell membranes and resistance to class IIa bacteriocins. Moreover, the PG composition may be regulated differently, as seen for the differing effects of the desaturase inhibitor on the sensitive and resistant strains. The resistance of the intermediate-resistance strains could be modulated by changing the PG composition of their membranes by treatment with SME. However, we observed no changes in the resistance of highly resistant strains after the same treatment.

Membrane adaptation is probably only one of several mechanisms involved in resistance, and our present results show clearly that other mechanisms are necessary for the development of complete resistance. For example, the absence of a putative mannose-specific PTS enzyme IIAB component under σ54 control has been noted in L. monocytogenes B73-MR1 (32) and L. monocytogenes 412P (M. Ramnath and A. Gravesen, personal communication). The absence of this membrane-bound enzyme may be associated with resistance, but it may also influence membrane fluidity and lipid ordering. Further consideration should also be given to the role of desaturase(s) and the influence of membrane composition on bacteriocin resistance.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Gravesen and Y. Héchard for helpful discussions. We are also grateful to A. Gravesen for providing the pediocin-resistant and -sensitive strains. We also thank S. Aimoto and K. Tamura for the gift of leucocin A.

This research was supported by a National Research Foundation Grant (South Africa) to J. W. Hastings.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilar, P. S., J. E. Cronan, Jr., and D. de Mendoza. 1998. A Bacillus subtilis gene induced by cold shock encodes a membrane phospholipid desaturase. J. Bacteriol. 180:2194-2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilar, P. S., A. M. Hernandez-Arriaga, L. E. Cybulski, A. C. Erazo, and D. de Mendoza. 2001. Molecular basis of thermosensing: a two-component signal transduction thermometer in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 20:1681-1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer, A. S., R. Prasad, J. Chandra, A. Koul, M. Smriti, A. Varma, R. A. Skurray, N. Firth, M. H. Brown, S. Koo, and M. R. Yeaman. 2000. In vitro resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein is associated with alterations in cytoplasmic membrane fluidity. Infect. Immun. 68:3548-3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennik, M. H. J., A. Verheul, T. Abee, G. Naaktgeboren-Stoffels, L. G. M. Gorris, and E. J. Smid. 1997. Interactions of nisin and pediocin PA-1 with closely related lactic acid bacteria that manifest over 100-fold differences in bacteriocin sensitivity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3628-3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhunia, A. K., M. C. Johnson, and N. Kalyachayanand. 1991. Mode of action of pediocin AcH from Pediococcus acidilactici H on sensitive bacterial strains. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 70:25-33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bierbaum, G., K. Fuchs, W. Lenz, C. Szekat, and H.-G. Sahl. 1999. Presence of Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin in Germany. Eur. J. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18:691-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black, G., A. P. Snyder, and K. S. Heroux. 1997. Chemotaxonomic differentiation between the Bacillus cereus group and Bacillus subtilis by phospholipid extracts analysed with electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry. J. Microbiol. Methods 28:187-199. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruno, M., and T. J. Montville. 1993. Common mechanistic action of bacteriocin from lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3003-3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabrera, G. M., M. L. Fernandez Murga, G. Font de Valdez, and A. M. Seldes. 2000. Direct analysis by electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry of mixtures of phosphatidyldiacylglycerols from Lactobacillus. J. Mass. Spectrom. 35:1452-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, Y., and T. J. Montville. 1995. Efflux of ions and ATP depletion induced by pediocin PA-1 are concomitant with cell death in Listeria monocytogenes Scott A. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 175:3232-3235. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, Y., R. Shapira, M. Einstein, and T. J. Montville. 1997. Functional characterization of pediocin PA-1 binding to liposomes in the absence of a protein receptor and its relationship to a predicted tertiary structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:524-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, Y., R. D. Ludescher, and T. J. Montville. 1997. Electrostatic interactions, but not the YGNGV consensus motif, govern binding of pediocin PA-1 and its fragments to phospholipid vesicles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4770-4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, Y., R. D. Ludescher, and T. J. Montville. 1998. Influence of lipid composition on pediocin PA-1 binding to phospholipid vesicles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3530-3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chikindas, M. L., M. J. Garcia-Garcera, A. J. M. Driessen, A. M. Liedeboer, J. Nissen-Meyer, I. F. Nes, T. Abee, W. N. Konings, and J. Venema. 1993. Pediocin PA-1, a bacteriocin from Pediococcus acidilactici PAC1.0, forms hydrophilic pores in the cytoplasmic membrane of target cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3577-3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalet, K., C. Briand, Y. Cenatiempo, and Y. Héchard. 2000. The rpon gene of Enterococcus faecalis directs sensitivity to subclass IIa bacteriocins. Curr. Microbiol. 41:441-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalet, K, Y. Cenatiempo, P. Cossart, The European Listeria Genome Consortium, and Y. Héchard. 2001. A σ54-dependent PTS permease of the mannose family is responsible for sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes to mesentericin Y105. Microbiology 147:3263-3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demel, R. A., T. Peelen, R. J. Siezen, B. de Kruijff, and O. P. Kuipers. 1996. Nisin Z, mutant nisin Z and lacticin 481 interactions with anionic lipids correlate with antimicrobial activity—a monolayer study. Eur. J. Biochem. 235:267-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du Toit, E. A., and M. Rautenbach. 2000. A sensitive standardised micro-gel well diffusion assay for the determination of antimicrobial activity. J. Microbiol. Methods 42:159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fimland, G., R. Jack, G. Jung, I. F. Nes, and J. Nissen-Meyer. 1998. The bactericidal activity of pediocin PA-1 is specifically inhibited by a 15-mer fragment that spans the bacteriocin from the center toward the C terminus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:5057-5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer, W., and K. Leopold. 1999. Polar lipids of four Listeria species containing l-lysylcardiolipin, a novel lipid structure, and other unique phospholipids. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:653-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gravesen, A., P. Warthoe, S. Knøchel, and K. Thirstrup. 2000. Restriction fragment differential display of pediocin-resistant Listeria monocytogenes 412 mutants shows consistent over expression of a putative β-glucoside-specific PTS system. Microbiology 146:1381-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Héchard, Y., C. Pelletier, Y. Cenatiempo, and J. Fréré. 2001. Analysis of σ54-dependent genes in Enterococcus faecalis: a mannose PTS permease (EII Man) is involved in sensitivity to a bacteriocin, mesentericin Y105. Microbiology 147:1575-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jack, R. W., J. R. Tagg, and B. Ray. 1995. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 59:171-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser, A. L., and T. J. Montville. 1996. Purification of the bacteriocin bavaricin MN and characterization of its mode of action against Listeria monocytogenes Scott A cell and lipid vesicles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4529-4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klaenhammer, T. R. 1993. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 12:39-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosaric, N., and K. K. Carroll. 1971. Phospholipids of Listeria monocytogenes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 239:428-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maftah, A., D. Renault, C. Vignoles, Y. Héchard, P. Bressollier, M. H. Ratinaud, Y. Cenatiempo, and R. Julien. 1993. Membrane permeabilization of Listeria monocytogenes and mitochondria by the bacteriocin mesentericin Y105. J. Bacteriol. 175:3232-3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mastronicolis, S. K., J. B. German, and G. M. Smith. 1996. Diversity of the polar lipids of the food-borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. Lipids 31:635-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazzotta, A. S., and T. J. Montville. 1997. Nisin induces changes in membrane fatty acid composition of Listeria monocytogenes nisin-resistant strains at 10°C and 30°C. J. Appl. Microbiol. 82:32-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazzotta, A. S., and T. J. Montville. 1999. Characterization of fatty acid composition, spore germination, and thermal resistance in a nisin-resistant mutant of Clostridium botulium 169B and in the wild-type strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:659-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ming, X., and M. A. Daeschel. 1993. Nisin resistance of foodborne bacteria and the specific resistance responses of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A. J. Food. Prot. 56:836-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramnath, M., M. Beukes, K. Tamura, and J. W. Hastings. 2000. Absence of a putative mannose-specific phosphotransferase system enzyme IIAB component in a leucocin A-resistant strain of Listeria monocytogenes, as shown by two-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3098-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rekhif, N., A. Atrih, and G. Lefebvre. 1994. Selection and properties of spontaneous mutants of Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 15313 resistant to different bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. Curr. Microbiol. 28:237-241. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robichon, D., E. Gouin, M. Débarbouillé, P. Cossart, Y. Cenatiempo, and Y. Héchard. 1997. The rpoN (σ54) gene from Listeria monocytogenes is involved in resistance to mesentericin Y105, an antibacterial peptide from Leuconostoc mesenteroides. J. Bacteriol. 179:7591-7594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verheul, A, N. J. Russell, R. Van'T Hof, F. M. Rombouts, and T. Abee. 1997. Modifications of membrane phospholipid composition in nisin-resistant Listeria monocytogenes Scott A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3451-3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wältermann, M., and A. Steinbüchel. 2000. In vitro effects of sterculic acid on lipid biosynthesis in Rhodococcus opacus strain PD630 and isolation of mutants defective in fatty acid desaturation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 190:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan, L. Z., A. C. Gibbs, M. E. Stiles, D. S. Wishart, and J. C. Vederas. 2000. Analogues of bacteriocins: antimicrobial specificity and interactions of leucocin A with its enantiomer, carnobacteriocin B2, and truncated derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 43:4579-4581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Younsi, M., E. Ramanandraibe, R. Bonaly, M. Donner, and J. Coulon. 2000. Amphotericin B resistance and membrane fluidity in Kluyveromyces lactis strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1911-1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]