Abstract

The pharyngeal muscles of Caenorhabditis elegans are composed of the corpus, isthmus and terminal bulb from anterior to posterior. These components are excited in a coordinated fashion to facilitate proper feeding through pumping and peristalsis. We analysed the spatiotemporal pattern of intracellular calcium dynamics in the pharyngeal muscles during feeding. We used a new ratiometric fluorescent calcium indicator and a new optical system that allows simultaneous illumination and detection at any two wavelengths. Pumping was observed with fast, repetitive and synchronous spikes in calcium concentrations in the corpus and terminal bulb, indicative of electrical coupling throughout the muscles. The posterior isthmus, however, responded to only one out of several pumping spikes to produce broad calcium transients, leading to peristalsis, the slow and gradual motion needed for efficient swallows. The excitation–calcium coupling may be uniquely modulated in this region at the level of calcium channels on the plasma membrane.

Keywords: Caenorhabditis elegans, pharyngeal muscles, calcium imaging, feeding, peristalsis

Introduction

The pharyngeal muscles of Caenorhabditis elegans have three components: the corpus, isthmus and terminal bulb (Albertson & Thomson, 1975; Fig 1A). A pacemaker neuron, MC, excites the corpus (Raizen et al, 1995) and this activity is transmitted to the terminal bulb through the isthmus by electrical coupling (Avery & Horvitz, 1989; Starich et al, 1996). Pumping and peristalsis are the major components of the feeding behaviour of C. elegans. Pumping is a nearly simultaneous contraction of the corpus, anterior isthmus and terminal bulb. C. elegans pumps vigorously at approximately 4 Hz while feeding on bacteria (Horvitz et al, 1982; Niacaris & Avery, 2003). Peristalsis is a travelling wave of contraction at the posterior isthmus, which occurs once per several pumps. This motion carries bacteria from the middle of the isthmus to the grinder (terminal bulb). As the isthmus is composed of a bundle of three muscles of one type, there is a difference in the contraction pattern between the anterior and posterior parts of the muscles.

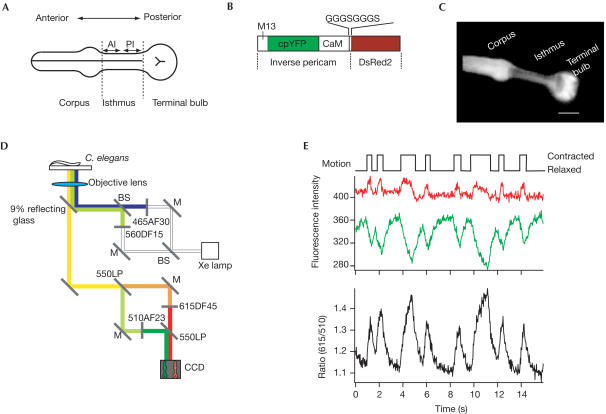

Figure 1.

Experimental strategy for visualizing the spatiotemporal pattern of calcium dynamics in the pharyngeal muscles of C. elegans. (A) Anatomy of pharyngeal muscles of C. elegans. Pumping is a simultaneous contraction of the corpus, anterior isthmus (AI) and terminal bulb, whereas peristalsis is a travelling wave of contraction emerging at the posterior isthmus (PI). The isthmus is made up of a bundle of three muscle cells of a single type. (B) Schematic primary structure of DRIP. CaM, calmodulin; M13, a CaM-binding peptide composed of 26 amino acids; cpYFP, circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein. (C) A typical photograph showing the expression pattern of DRIP in pharyngeal muscles under the control of the myo-2 promoter. Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Scheme for a new imaging system that allows simultaneous dual-wavelength excitation and simultaneous dual-emission detection. The light beams are coloured according to their wavelengths. BS; beam splitter, M; mirror. (E) Fluorescence intensities of DsRed2 (red) and inverse pericam (green) and their ratio (615/510 nm) at the terminal bulb when a nematode pumped at about 0.5 Hz. Top trace indicates the muscle motion judged by morphology changes.

The calcium dynamics in the pharyngeal muscles were studied (Kerr et al, 2000) using the first generation of cDNA-encodable calcium indicators, cameleon (Miyawaki et al, 1997). In that study, cameleon was not expressed in the isthmus, and calcium was measured only at the terminal bulb. In addition, the feeding behaviour was categorized as very slow pumping (<0.5 Hz), slow pumping (0.5–1.5 Hz) and fast pumping (>1.5 Hz), and only the slow pumping was analysed for a quantitative comparison of the slope, amplitude and duration of the calcium transients in wild-type and mutant worms.

In contrast, we investigated the spatial and temporal dynamics of Ca2+ fluxes through all the pharyngeal muscles during natural feeding behaviour, that is, fast pumping, to achieve a complete understanding of how their excitation is controlled. We have generated a ratiometric indicator for Ca2+, which can be distributed in all the pharyngeal muscles, including the isthmus. To use this indicator for visualizing fast pumping of the pharyngeal muscles, we have developed a simultaneous illumination and detection system. The simultaneous acquisition of Ca2+-sensitive images (green) and Ca2+-insensitive images (red) permits quantitative Ca2+ measurements by minimizing the effects of several artefacts that are unrelated to changes in the concentration of free Ca2+, and, in this case, will correct for movement of the pharyngeal muscles.

We found that the Ca2+ transients in the posterior isthmus were broad and followed one out of several spikes in the anterior isthmus and terminal bulb, which may be necessary for the proper timing and mechanics of peristalsis. The cellular mechanisms underlying coordinated contraction will be discussed in terms of Ca2+ regulation.

Results And Discussion

Pericam is a family of newly developed cDNA-encodable calcium indicators, which are based on circularly permuted yellow fluorescent proteins (Nagai et al, 2001). This family has three members: flash pericam, inverse pericam and ratiometric pericam. Inverse pericam is the brightest among them, but is less useful because it loses its green fluorescence upon Ca2+ binding. To generate a bright and useful indicator for quantitative Ca2+ imaging, we have attached red fluorescent protein, DsRed2, via a short linker, GGGSGGGS (G=glycine, S=serine), to the C terminus of inverse pericam. The resulting indicator, called ‘DRIP' (DsRed2-referenced Inverse Pericam) is a dual-emission ratiometric indicator that requires two excitation wavelengths (Fig 1B). The red to green ratio increases upon binding Ca2+ with the same affinity (Kd for Ca2+, 0.2 μM) as inverse pericam (S.S. and A.M., unpublished data). When expressed in C. elegans under the control of the myo-2 promoter, which is specific for pharyngeal muscles (Okkema et al, 1993), DRIP is distributed in all the pharyngeal muscles (Fig 1C).

For fast Ca2+ imaging in the vigorously contracting muscles, inverse pericam and DsRed2 in DRIP must be excited and detected simultaneously. We have developed a new system based on conventional epifluorescence microscopy (Fig 1D). The light from a 75 W Xe lamp was split by a beam splitter (BS) and the two beams were band-pass-filtered at appropriate wavelengths for excitation of inverse pericam and DsRed2. The excitation beams were combined by another BS and introduced into an inverted microscope. The emitted fluorescence of the two colors was measured simultaneously with commercially available equipment. Whereas simultaneous illumination and detection is common in laserscanning confocal microscopy, the typical system adopting point scanning has a limited time resolution and is not suitable for fast Ca2+ imaging.

Feeding behaviour was induced by soaking the nematodes in a serotonin solution (Avery & Horvitz, 1990). A typical temporal profile of the ratio of red to green signals (615/510 nm) obtained from the terminal bulb that contracted at 0.5–1 Hz is shown in Fig 1E (lower black trace). Streams of images were taken at 30 Hz. Whereas the deflection of the red fluorescence signal from DsRed2 followed the motion quickly (Fig 1E, red trace), the green fluorescence signal from inverse pericam changed slowly (Fig 1E, green trace), as reported previously (Kerr et al, 2000). These results indicate that DRIP can report Ca2+ dynamics in moving muscles.

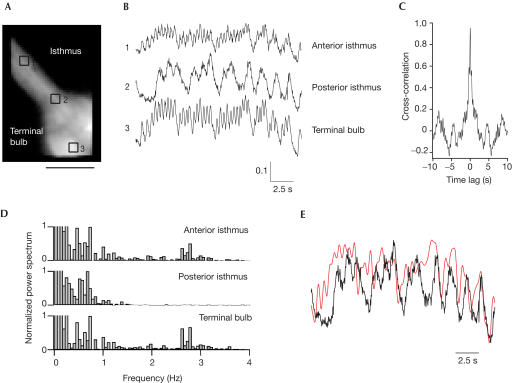

We observed the calcium dynamics at multiple points using a worm exhibiting slow pumping (0.5–1 Hz). Signals from the anterior isthmus (Fig 2A, region of interest (ROI) #1), the posterior isthmus (Fig 2A, ROI #2), as well as the terminal bulb (Fig 2A, ROI #3) were measured. The pumping rhythm in these three regions appeared nearly synchronized (Fig 2B). Alignment of the traces revealed that the Ca2+ transients in the anterior isthmus (#1) and terminal bulb (#3) were tightly synchronized, whereas the Ca2+ transient in the posterior isthmus (#2) was broad and delayed (Fig 2C). When the entire pharynx was imaged using a low-magnification lens, the tight synchronism of the Ca2+ transients in the corpus to those in the anterior isthmus and terminal bulb was verified (S.S. and A.M., unpublished data).

Figure 2.

Calcium measurements in slowly pumping pharyngeal muscles (0.5 Hz). (A) Fluorescence image of the isthmus and terminal bulb. Scale bar, 20 μm. Regions of interest (ROIs) were placed in the anterior isthmus (ROI#1), posterior isthmus (ROI#2) and terminal bulb (ROI#3). (B) Temporal profiles of the ratio (615/510 nm) values in the three ROIs. (C) Comparison of the calcium transients in the three ROIs. Peaks are aligned with respect to the peaks of ROI#3 and normalized.

The retarded Ca2+ dynamics observed in the posterior isthmus was further explored using worms that pumped fast (3 Hz) naturally (Fig 3A,B). Again, the tight synchronism of the Ca2+ transients between the terminal bulb and the anterior isthmus was confirmed by a cross-correlogram (Fig 3C). The posterior isthmus seemed to extract a low-frequency component of the fluctuations taking place in other parts (low-pass filtering), and/or seemed to pick one out of several pumping spikes to produce broad Ca2+ transients (random decoupling). When the power spectra of the three regions were compared (Fig 3D), it was revealed that the high-frequency component around 3 Hz was missing in the posterior isthmus. The trace from the terminal bulb was then low-pass filtered with a cutoff frequency of 2 Hz and superimposed onto the posterior isthmus trace (Fig 3E). They did not fit each other; their poor correlation was characterized by a low correlation coefficient of 0.60. The mean correlation coefficient value from five wild-type worms that showed fast pumping was 0.75±0.08. These results suggest random decoupling of Ca2+ spikes in the posterior isthmus.

Figure 3.

Calcium measurements in quickly pumping pharyngeal muscles (3 Hz). (A) Fluorescence image of the isthmus and terminal bulb. Scale bar, 20 μm. Regions of interest (ROIs) were placed in the anterior isthmus (ROI#1), posterior isthmus (ROI#2) and terminal bulb (ROI#3). (B) Temporal profiles of the ratio (615/510 nm) values in the three ROIs. (C) Cross-correlogram between ROI#1 and ROI#3. This confirms the synchronism of the calcium dynamics between ROI#1 and ROI#3 (time lag=0 and the cross-correlation value at time 0=0.95). (D) Power spectra of the data at the three ROIs. Values are normalized around 0.7 Hz. (E) Correlation between the low-pass-filtered Ca2+ dynamics of the terminal bulb (red) and the posterior isthmus Ca2+ dynamics (black). The terminal bulb trace in (B) was low-pass filtered (cutoff frequency=2 Hz) and superimposed on the posterior isthmus trace in (B).

We examined whether the retarded Ca2+ transients are indeed responsible for peristalsis. We attempted to image peristalsis by feeding nematodes with Escherichia coli expressing DsRed2. The passage of red fluorescence through the posterior isthmus indicated the occurrence of peristalsis. In this experiment, we monitored Ca2+ using only the green fluorescence signals. Whenever peristalsis occurred (Fig 4, arrowheads), a significant increase in Ca2+ was detected (Fig 4, top). A series of images for red fluorescence during the left-most spike is shown (Fig 4, bottom); a clump of red bacteria was clearly witnessed to pass through the isthmus. It was thus concluded that each Ca2+ transient and peristalsis correlated well at the posterior isthmus.

Figure 4.

Observation of calcium transients and peristalsis at the posterior isthmus. (Top) The trace was calculated as the reciprocal of fluorescence intensity of inverse pericam. The arrowheads indicate the time when peristalsis began as assessed by the movement of DsRed2-expressing E. coli. (Bottom) An example of the movement of the red bacteria is shown. Similar results were obtained from two other experiments.

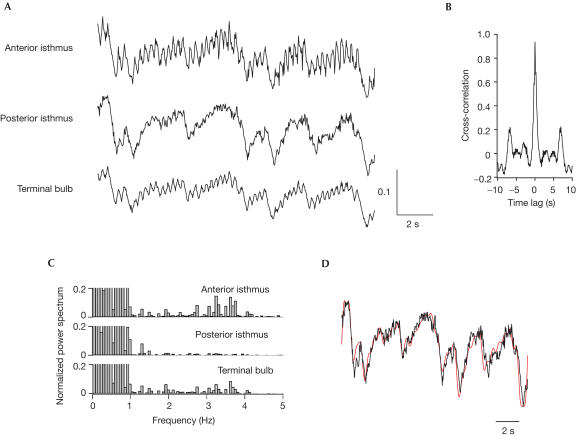

We next explored the origin of the calcium ions causing the slow Ca2+ dynamics at the posterior isthmus. We examined the involvement of Ca2+ mobilization from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) through the ryanodine receptor Ca2+ channel, as is characteristic of Ca2+ dynamics. There is only a single gene, unc-68, that encodes a ryanodine receptor in C. elegans (Sakube et al, 1993; Maryon et al, 1996). Within the pharyngeal muscles, interestingly, UNC-68 localized to the SR at the posterior isthmus and terminal bulb (Maryon et al, 1998). This raised the intriguing possibility that UNC-68 might prolong the Ca2+ rising phase via Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR), leading to Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Ca2+ channels at the plasma membrane. A null mutant, unc-68(e540) (Sakube et al, 1997), apparently showed broad Ca2+ dynamics at the posterior isthmus (Fig 5A). The tight synchronism between the anterior isthmus and the terminal bulb and the absence of the high-frequency component in the posterior isthmus were confirmed by correlogram (Fig 5B) and power spectra (Fig 5C), respectively. Interestingly, the posterior isthmus trace and a low-pass-filtered trace from the terminal bulb fitted well (Fig 5D), yielding a high correlation coefficient (0.93). The mean value from three unc-68 mutants was 0.92±0.003, which contrasts with the poor correlation in wild-type worms (0.75±0.08; Fig 3E).

Figure 5.

Calcium measurements in the pharyngeal muscles of quickly pumping unc-68 mutants (4 Hz). (A) Temporal profiles of the ratio (615/510 nm) values in the anterior isthmus, posterior isthmus and terminal bulb. (B) Cross-correlogram between the anterior isthmus and terminal bulb (time lag=0 and the cross-correlation value at time 0=0.94). (C) Power spectra of the data at the three regions. Values are normalized around 0.44 Hz. (D) Correlation between the low-pass-filtered Ca2+ dynamics of the terminal bulb (red) and the posterior isthmus Ca2+ dynamics (black). The terminal bulb trace in (A) was low-pass filtered (cutoff frequency=2 Hz) and superimposed on the posterior isthmus trace in (A).

Here we investigated the Ca2+ dynamics within all the pharyngeal muscles of C. elegans during natural feeding behaviours exhibiting fast pumping. Muscle contraction is triggered by firing of the MC neuron. The excitation is quickly transmitted from the corpus to the terminal bulb through the isthmus by electrical coupling. Thus, the corpus, anterior isthmus and terminal bulb synchronously contract with fast Ca2+ spikes. Within the synchronous contractions over the pharynx, however, the midportion, the posterior isthmus, exhibits a slow movement called peristalsis. In the present study, we demonstrate that the Ca2+ dynamics in the posterior isthmus are often decoupled during fast pumping. As each of the three muscle cells spans the anterior and posterior isthmus, it is interesting to know the mechanism(s) by which Ca2+ dynamics are differentially regulated within a cell. One possibility is that the excitation–calcium coupling is uniquely modulated at the posterior isthmus at the level of Ca2+ channels on the plasma membrane. It should be noted that within the isthmus, the ryanodine receptor is localized to the posterior portion. Our analyses using unc-68 mutants supported a possible role for the participation of Ca2+ released from the internal stores (CICR) in the random decoupling of Ca2+ spikes and suggested other mechanisms for low-pass-filtered Ca2+ dynamics. It is important to consider the involvement of the neuron that innervates the posterior isthmus (M4) (Albertson & Thomson, 1975). When this neuron is killed soon after hatching, peristalsis does not occur and the nematodes do not mature (Avery & Horvitz, 1987). Although the electrical activity of M4 has not been detected electrophysiologically (Raizen & Avery, 1994), it is possible that the neuron modulates the excitation–calcium coupling in the posterior isthmus.

Methods

Construction of indicator. The gene for inverse pericam was amplified with a sense primer containing a BamHI site and a reverse primer containing a sequence encoding a peptide linker GGGSGGGS and an EcoRI site. The digested PCR product was inserted into the BamHI/EcoRI sites of pcDNA3 (Invitrogen), yielding inverse pericam/pcDNA3. The gene for DsRed2 was amplified with a sense primer containing a NotI site and a reverse primer containing an XhoI site. The restricted fragment was inserted in frame into the NotI/XhoI sites of inverse pericam/pcDNA3, yielding DRIP/pcDNA3. The DRIP gene was then amplified with a sense primer containing an NheI site and a reverse primer containing a SacI site. The restricted fragment was subcloned into the NheI/SacI site of pPD49.26, yielding DRIP/pPD49.26. The myo-2 promoter fragment was retrieved from pPD30.69 by digestion with HindIII and NheI. The fragment was inserted into the HindIII/NheI sites of DRIP/pPD49.26.

Nematode culture. A solution containing 5 ng/μl cDNA encoding DRIP was injected into N2 worms and unc-68(e540) worms. They were cultured at 20°C.

Calcium imaging. The two beams for excitation of inverse pericam and DsRed2 were created using band-pass filters 465AF30 (Omega) and 560DF15 (Omega), respectively. They were combined and introduced into an inverted microscope (IX70, Olympus). Emitted light was measured with a simultaneous image acquisition device (W-View, HamamatsuPhotonics) accommodating a dichroic mirror 550LP (Omega) and band-pass filters 510AF23 (Omega) and 615DF45 (Omega). Images were captured around 30 Hz. Nematodes were glued on an agar pad and feeding behaviour was stimulated using serotonin at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml.

Data analysis. Fluorescence intensities and ratio changes were measured using software (AquaCosmos, HamamatsuPhotonics), and cross-correlogram and power spectra were obtained using custom macroprograms based on Igor Pro (Wavemetrix).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr T. Nagai, Dr M. Doi, Dr T. Inoue and Dr Y. Aono for valuable advice and Dr A. Fire for pPD vectors. Worm strain unc-68(e540) was provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources. This work was partly supported by grants from CREST of Japan Science and Technology, the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, and Human Frontier Science Program.

References

- Albertson DG, Thomson JN (1975) The pharynx of Caenorhabditis elegans. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B 275: 299–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L, Horvitz HR (1987) A cell that dies during wild type C. elegans development can function as a neuron in a ced-3 mutant. Cell 51: 1071–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L, Horvitz HR (1989) Pharyngeal pumping continues after laser killing of the pharyngeal nervous system of C. elegans. Neuron 3: 473–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L, Horvitz HR (1990) Effects of starvation and neuroactive drugs on feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Exp Zool 253: 263–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz HR, Chalfie M, Trent C, Sulston JE, Evans PD (1982) Serotonin and octopamine in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 216: 1012–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr R, Lev-Ram V, Baird GS, Vincent P, Tsien RY, Schafer WR (2000) Optical imaging of calcium transients in neurons and pharyngeal muscle of C. elegans. Neuron 26: 583–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryon EB, Coronado R, Anderson P (1996) unc-68 encodes a ryanodine receptor involved in regulating C. elegans body-wall muscle contraction. J Cell Biol 134: 885–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryon EB, Saari B, Anderson P (1998) Musclespecific function of ryanodine receptor channels in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Sci 111: 2885–2895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki A, Llopis J, Heim R, McCaffery JM, Adams JA, Ikura M, Tsien RY (1997) Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature 388: 882–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Sawano A, Park ES, Miyawaki A (2001) Circularly permuted green fluorescent proteins engineered to sense Ca2+. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 3197–3202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niacaris T, Avery L (2003) Serotonin regulates repolarization of the C. elegans pharyngeal muscle. J Exp Biol 206: 223–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okkema PG, Harrison SW, Plunger V, Aryana A, Fire A (1993) Sequence requirement for myosin gene expression and regulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 135: 385–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizen DM, Avery L (1994) Electrical activity and behavior in the pharynx of Caenorhabditis elegans. Neuron 12: 483–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizen DM, Lee RYN, Avery L (1995) Interacting genes required for pharyngeal excitation by motor neuron MC in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 141: 1365–1382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakube Y, Ando H, Kagawa H (1993) Cloning and mapping of a ryanodine receptor homolog gene of Caenorhabditis elegans. Ann NY Acad Sci 707: 540–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakube Y, Ando H, Kagawa H (1997) An abnormal ketamine response in mutants defective in the ryanodine receptor gene ryr-1 (unc-68) of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Mol Biol 267: 849–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starich TA, Lee RYN, Panzarella C, Avery L, Shaw JE (1996) eat-5 and unc-7 represent a multigene family in Caenorhabditis elegans involved in cell–cell coupling. J Cell Biol 134: 537–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]