Abstract

The Polycomb group (PcG) of proteins conveys epigenetic inheritance of repressed transcriptional states. In Drosophila, the Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) maintains the silent state by inhibiting the transcription machinery and chromatin remodelling at core promoters. Using immunoprecipitation of in vivo formaldehyde-fixed chromatin in phenotypically diverse cultured cell lines, we have mapped PRC1 components, the histone methyl transferase (HMT) Enhancer of zeste (E(z)) and histone H3 modifications in active and inactive PcG-controlled regions. We show that PRC1 components are present in both cases, but at different levels. In particular, active target promoters are nearly devoid of E(z) and Polycomb. Moreover, repressed regions are trimethylated at lysines 9 and 27, suggesting that these histone modifications represent a mark for inactive PcG-controlled regions. These PcG-specific repressive marks are maintained by the action of the E(z) HMT, an enzyme that has an important role not only in establishing but also in maintaining PcG repression.

Keywords: Polycomb, PRC1, E(z), histone methylation, transcriptional repression

Introduction

The Polycomb group (PcG) and trithorax group (trxG) of genes code for components of multiprotein complexes that control the maintenance of the repressed and active state, respectively, of developmentally regulated genes. Both groups are genetically linked and work together forming a ‘cellular memory' system that acts primarily at the level of chromatin, preventing changes in transcription programmes (Francis & Kingston, 2001; Orlando, 2003).

Two distinct PcG complexes have been purified in Drosophila. One of these, the Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1), contains among others the proteins Polycomb (Pc), Polyhomeotic (Ph), Posterior sex combs (Psc) and Ring1, which are the main components of a minimal core complex (PCC), that can block SWI/SNF remodelling and transcription in vitro (Shao et al, 1999; Lavigne et al, 2004). A second complex contains, among others, the PcG protein Enhancer of zeste (E(z)). E(z) is the only PcG protein with an assigned putative function bearing a histone methyltransferase (HMT) activity that is specific for lysines 9 and 27 of histone H3 in vitro (Cao et al, 2002; Czermin et al, 2002; Müller et al, 2002).

Differing results have been obtained concerning PcG-specific H3 methylation patterns and the in vivo activity of E(z). Dimethylation and trimethylation of lysine 9 (Lys 9) of histone H3 have been linked to heterochromatic regions in various organisms (Nakayama et al, 2001; Peters et al, 2003) and also to PcG binding sites on Drosophila polytene chromosomes (Czermin et al, 2002). By immunostaining, Czermin and colleagues concluded that primarily methylation of Lys 9 seems to be involved in PcG repression, although methylation of Lys 27 could not be excluded. H3 Lys 27 dimethylation has been mapped to a cis-regulatory PcG response element (PRE) and the Ubx promoter region in flies (Cao et al, 2002; Wang et al, 2004). Lys 27 trimethylation only seems to colocalize with PcG proteins in Schneider-2 (S2) culture cells and on polytene chromosomes (Fischle et al, 2003). Finally, Pc itself can bind H3 tails trimethylated at Lys 27 (Czermin et al, 2002; Fischle et al, 2003). All this suggests that the activity of an E(z)-containing complex leads to the establishment of a specific methylation pattern in the region of PcG targets and to the recruitment of PRC1 (Wang et al, 2004). However, the exact H3 methylation pattern in PcG-repressed regions, core promoters and PREs, remains to be established as well as a correlation with PRC1 presence and the transcriptional states of the homeotic target genes.

Here, we compare the presence of the PRC1 core proteins, E(z), proteins of the transcriptional machinery and the related H3 methylation profile in promoter regions of two PcG target genes in the active and repressed states. We show that high levels of PcG proteins, in particular Pc and E(z), are the characteristic feature of repressed promoters. Conversely, active promoters are virtually devoid of Pc and E(z). The presence of both proteins is linked with a characteristic dual H3 mark, comprising both Lys 9 and Lys 27 trimethylation, a pattern that we also find in a repressive PRE region. In addition, we show that the reduction of PRC1 levels by double-stranded RNA interference (dsRNAi), resulting in the reactivation of the target gene, leads to the loss of E(z) and to a significant reduction of H3 trimethyl Lys 9 and Lys 27. This suggests that E(z) has an important role not only in the establishment of PcG-specific methylation marks but also in their maintenance during replication, as well as after recruiting Prc1.

Results And Discussion

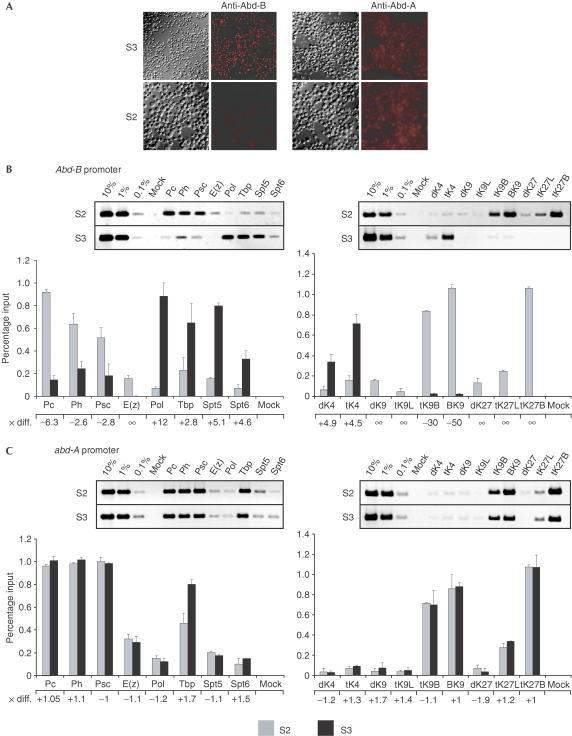

To compare promoter regions of differently expressed PcG-controlled genes, we used the two Drosophila cell lines S2 and S3, which show a particular expression pattern pertaining to genes Abdominal B (Abd-B) and abdominal A (abd-A) of the Bithorax Complex (BXC). Abd-B can be detected in S3 but not in S2 cells (Fig 1A). In addition, the Abd-B promoter produces a spliced, polyadenylated transcript in S3 cells, whereas no such transcript can be detected in S2 cells (data not shown). Abd-A is not expressed in either cell line (Fig 1A), nor is a transcript produced (data not shown). We analysed both promoters by immunoprecipitation of in vivo formaldehyde-fixed chromatin (X-ChIP), using antisera against Pc, Ph, Psc and E(z), RNA polymerase II (Pol II), TATA-binding protein (Tbp) and the elongation factors Spt5 and Spt6. Further, we investigated the pattern of H3 methylation using antisera that recognize various methylated isoforms of this histone (Table 1 and supplementary information online).

Figure 1.

Proteins and histone H3 methylation patterns in the Abd-B and abd-A promoter regions of the Bithorax Complex. (A) Expression of Abd-B and abd-A in S3 and S2 cells. (B,C) PCR analysis with crosslinked and immunoprecipitated DNA of the Abd-B-B promoter (primer p10; B) and the abd-A-AI promoter (primer p19b; C). Gels resulting from precipitations of S2-chromatin (top), and S3-chromatin (below) are shown. PCR reactions with 10, 1 and 0.1% of the input DNA are loaded to determine the linear range of amplification and to use for normalization during quantification. The different antisera used for the immunoprecipitations (IPs) are indicated (for abbreviations, see Table 1 and text) above the gels. The graphs show quantitative analyses of the ethidium-bromidestained bands from two independent experiments. The values on the y-axis represent the amount of immunoprecipitated DNA as a percentage of the input. The absolute difference of values for S3 versus S2 is indicated for each precipitation (× diff.) below the graphs.

Table 1.

Antisera against methylated isoforms of histone H3

| Namea | Epitope | References |

|---|---|---|

| dK4 |

Dimethylated Lys 4, linear |

See Methods and supplementary information online |

| tK4 |

Trimethylated Lys 4, linear |

See Methods and supplementary information online |

| dK9 |

Dimethylated Lys 9, linear |

Nakayama et al (2001); Upstate Biotechnology 07-212; specificity tested by Perez-Burgos et al (2004) |

| tK9L |

Trimethylated Lys 9, linear |

See Methods and supplementary information online |

| tK9B |

Trimethylated Lys 9, 2 × branched |

Peters et al (2003); Perez-Burgos et al (2004) |

| brK9 |

Dimethylated Lys 9, 4 × branched; has strong affinity to trimethylated Lys 9 |

Perez-Burgos et al (2004) |

| dK27 |

Dimethylated Lys 27, linear |

Upstate Biotechnology 07-452 |

| tK27L |

Trimethylated Lys 27, linear |

F. Sauer (unpublished data), specificity for Lys 27 tested by western dotblot (F. Sauer, personal communication) |

| tK27B | Trimethylated Lys 27, 2 × branched | Peters et al (2003); Perez-Burgos et al (2004) |

The immunopurified DNA was analysed using primer pairs amplifying the promoter regions of both genes (primer pairs p10 and p19b; Breiling et al, 2001) containing the transcription start site. As shown in Fig 1B, in the core promoter region of Abd-B, all PcG proteins show a higher binding rate in S2 cells than in S3 cells. This is particularly striking for Pc and E(z). E(z) is virtually absent in the active Abd-B promoter, but interacts with the repressed Abd-B promoter, together with PRC1 components. For Pol II and both elongation factors, we find the reverse situation, although these factors are not absent at the repressed promoter. Interestingly, Tbp levels do not differ much, raising the possibility that Tbp may be an important target for interactions of PRC1 with the transcriptional machinery. In contrast to Abd-B, the protein patterns in the abd-A promoter are strikingly similar in both cell lines and match those observed for the inactive Abd-B promoter in S2 cells (Fig 1C). The recruitment of Pol II, Tbp and elongation factors to an endogenous repressed promoter seems to be possible, although transcriptional activation is blocked. These findings are in line with recent data, which show that a transgenic hsp26 heatshock promoter, repressed by a nearby PRE, is also occupied by Tbp and RNA Pol II, but transcriptional initiation is blocked (Dellino et al, 2004). Thus, PcG proteins create a chromatin environment that inhibits the correct engagement and progressive movement of the polymerase and associated proteins, but not the binding of these factors.

Two alternative histone H3 methylation patterns for the active and the inactive Abd-B promoter were observed (Fig 1B). The active promoter is marked by dimethylation and trimethylation of Lys 4. For the repressed promoter, we observed high levels of H3 methyl Lys 9 and H3 methyl Lys 27, particularly of the trimethylated isoforms. These findings are confirmed by the results from the abd-A region (Fig 1C), in which the repressed promoter is marked by H3 trimethyl Lys 9 and H3 trimethyl Lys 27 in both cell lines. The presence of both modifications was independently confirmed using different antibodies specific for the same modifications (Table 1 and supplementary information online).

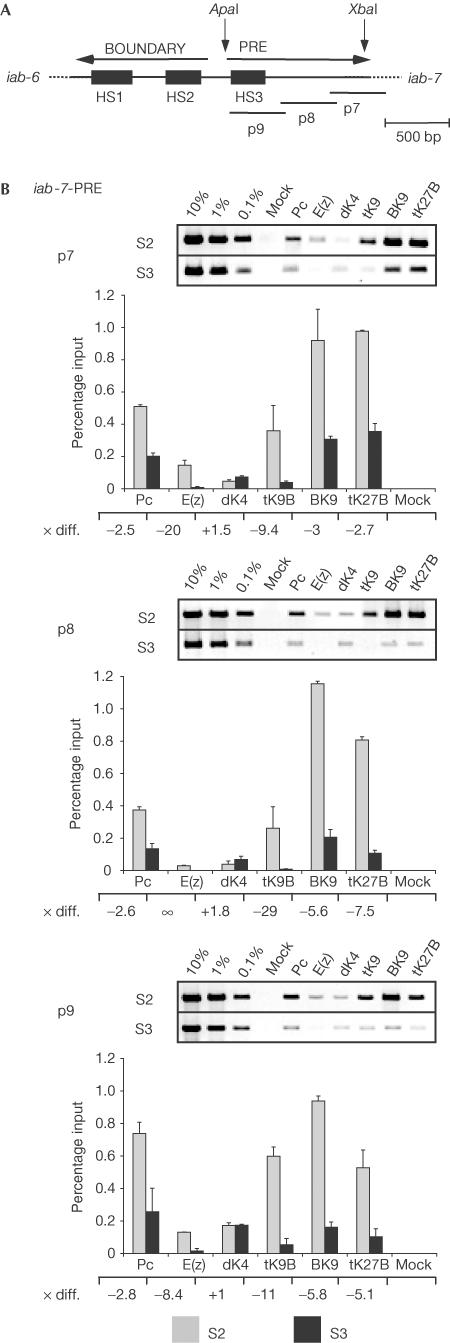

An 860-base-pair (bp) ApaI–XbaI fragment of the iab-7 region of the BXC has been identified genetically as a PcG-dependent silencer (PRE) responsible for the segment-specific repression of Abd-B. A 260-bp part of it, containing a nuclease hypersensitive region (HS3), has been isolated as a minimal PRE (Mishra et al, 2001, and references therein). Using three primer pairs spanning this PRE region (Fig 2A), we mapped Pc, E(z), H3 dimethyl Lys 4, H3 trimethyl Lys 9 and H3 trimethyl Lys 27 in the repressed (S2 cells, Abd-B is not expressed) and the active state (S3 cells, Abd-B is expressed). As for the promoter regions, the repressed state can be correlated with the presence of Pc and E(z) and is marked by trimethylation of Lys 9 and Lys 27 of H3 (Fig 2B). We observed a main peak of Pc binding for the primer pair p9, which contains the minimal PRE. In the active state, E(z) is not present in the PRE; Pc levels and trimethylation of Lys 9 and Lys 27 are reduced. Interestingly, no significant upmethylation of Lys 4 in the PRE is observed when Abd-B is active, indicating that Lys 4 methylation is specifically linked to transcriptional activity in promoter regions or genes. Taken together, our data on iab-7-PRE are consistent with the activity of its cis-regulatory target, the Abd-B gene.

Figure 2.

Proteins and histone H3 methylation patterns in the iab-7-PRE of the Bithorax Complex. (A) Schematic representation of the iab-7 region and the position of the three primer pairs used for X-ChIP. (B) PCR analysis of crosslinked and immunoprecipitated DNA of the iab-7-PRE region, presented as in Fig 1B. The different antisera used for the IPs are indicated above the gels.

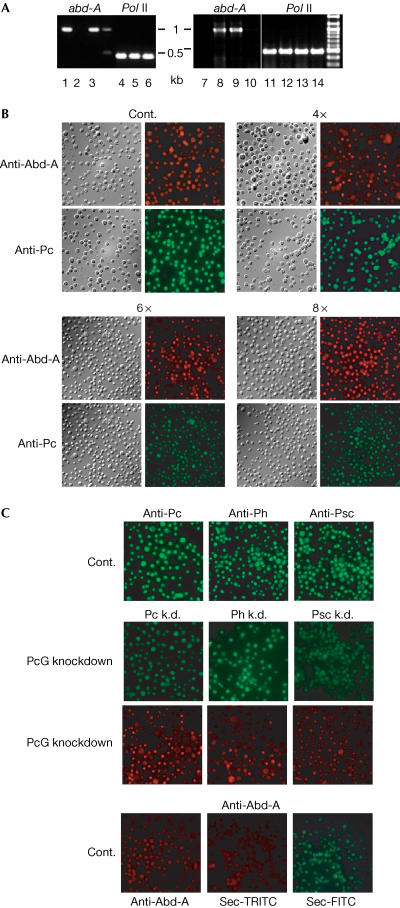

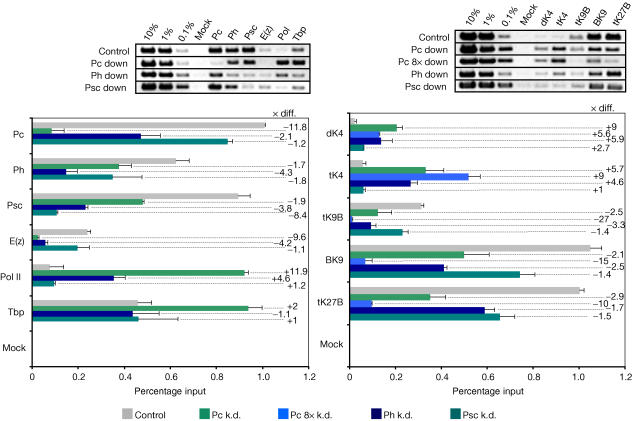

PcG-repressed promoters get derepressed after inhibition of PcG protein synthesis by dsRNAi in S2 cells (Breiling et al, 2001). We made use of this observation to perform X-ChIP analysis on the derepressed abd-A promoter (Fig 3A). After four rounds of treatment with Pc-dsRNA, a spliced, polyadenylated abd-A transcript is detected. Virtually 100% of the cells were negative for Pc staining (Fig 3B), and Pc was no longer detected by western blot in these cells (supplementary information online). The Abd-A protein is produced after knockdown, although it is detected only in a subset of cells (Fig 3B). We prepared crosslinked chromatin of these cells and used this material for X-ChIP (Fig 4). After reactivation of abd-A, we see patterns that resemble those observed for the active Abd-B gene in S3 cells (Fig 1B)—that is, high levels of Pol II, Tbp and the elongation factors and low occupancy for Pc (as expected, as this protein was knocked down) and E(z). Psc and Ph levels are also affected, indicating the importance of Pc for the coherence of PRC1. H3 Lys 9 di-/trimethylation and Lys 27 trimethylation are severely reduced, concomitant with an increase in Lys 4 di-/trimethylation. The levels of H3 trimethyl Lys 9 and H3 trimethyl Lys 27 can be further reduced by additional rounds of dsRNA treatment (see Pc 8 × k.d. in Fig 4, right panel), which also leads to an increased number of Abd-A-expressing cells (Fig 3B). Thus, the artificial derepression of the abd-A promoter is a slow process that requires the cells to go through repeated rounds of replication. We suggest that this happens, as it is necessary to dilute out, through cell division, PcG components and the repressive methylation marks near the promoter by histone replacement (as suggested by Wang et al, 2004). Similarly, H3 Lys 9 and Lys 27 trimethylation will be lost, as the maintaining action of E(z) is missing. In parallel or subsequently, the methylation of H3 Lys 4 (possibly by the activity of the two trxG HMTs Ash1 and Trx) and the recruitment of remodelling activities such as the Brahma protein would enable functional initiation and transcriptional elongation (Beisel et al, 2002). In addition, we observed a mild upregulation of ph and Psc expression after Pc knockdown (see supplementary information online), which could compensate for the loss of Pc and further slow down the process of abd-A reactivation.

Figure 3.

Expression of Abd-A and PRC1 proteins in S2 cells. (A) Analysis of a specific abd-A transcript by RT–PCR. Template total RNA from embryos (0–24 h egg lays, positive control, lanes 1 and 4), nontreated S2 cells (lanes 2, 5, 7 and 11), S2 cells treated 4 × with dsRNA specific for Pc (lanes 3, 6, 8 and 12), for ph (lanes 9 and 13) and for Psc (lanes 10 and 14). As an input control, a primer pair specific for transcripts of the RP144 gene was included in the analysis. Amplified products using a primer pair specific for abd-A are shown on the left of each gel, and those using a primer pair specific for RP144 are shown on the right. (B) Expression of Abd-A and Pc in control cells, after four, six and eight rounds of Pc knockdown. (C) Expression of abd-A in S2 cells treated 4 × with PcG-dsRNAs. The expressions of PcG proteins in control and knocked down cells are shown below the reactivation of Abd-A in the knocked down cells. The expression of Abd-A in control cells and the staining patterns of the secondary antibodies used alone are shown at the bottom.

Figure 4.

PCR analysis with crosslinked and immunoprecipitated DNA of the reactivated abd-A promoter. Gels and quantifications resulting from precipitations of chromatin from cells treated 4 × with Pc-dsRNA, 8 × with Pc-dsRNA (only methylation) and 4 × with ph- and Psc-dsRNA, respectively, are shown. The absolute difference (× diff.) for chromatin of knocked down cells versus wild-type cells is indicated to the right of the bars.

In a last set of experiments, we also knocked down Ph and Psc. Psc is virtually absent after four rounds of dsRNA treatment, whereas the level of Ph is strongly reduced (Fig 3C and supplementary information online). After knockdown of Ph, as for Pc, a spliced, polyadenylated abd-A transcript is present, which is detected only at very low levels after Psc knockdown (Fig 3A, lane 12). In cells treated with Psc-dsRNA, no Abd-A protein is expressed, whereas the reduction of Ph levels leads to Abd-A expression, although in only a subset of cells (Fig 3C). This fits with the different efficiency of the Pc and ph knockdown. Chromatin was prepared from various dsRNA-treated cells and used for immunoprecipitation as described before (Fig 4). The reduction of Ph levels has an effect similar to the knockdown of Pc, although, due to the incomplete removal of the protein, to a lesser degree: E(z) binding to the abd-A promoter is reduced, Pol II and Tbp recruitment is increased, Lys 4 methylation increases and Lys 9/Lys 27 trimethylation decreases. Again, we observed a weak upregulation of Psc and Pc expression after ph knockdown (supplementary information online), which could result in a mild compensation for the reduction of Ph levels by overexpression of other PcG components, weakening the effect of the ph knockdown on abd-A reactivation. Reduction of Psc leads to little change, as expected, as the Psc knockdown did not result in the expression of Abd-A. Also in imaginal discs, no reactivation of target genes has been observed in clones mutant for Psc (Beuchle et al, 2001). Only in double-mutant clones for Psc and the PcG gene Supressor of zeste 2 (Su(z)2) did the expected reactivation of HOX targets take place. Thus, the functions of the Psc and Su(z)2 proteins are at least partly redundant.

Our results are in contrast with published immunohistochemical data, which solely identify H3 methyl Lys 27 as the mark for PcG-repressed regions (Fischle et al, 2003). This discrepancy may be due to the resolution of the X-ChIP method as compared with immunohistochemistry and the specificity of the single antibody used in that study. We therefore suggest that PcG-repressed regions, core promoters and PREs are marked by a specific pair of histone H3 modifications, trimethyl Lys 9 and trimethyl Lys 27. This is correlated with the presence of the major PcG-HMT, E(z), confirming the enzymatic specificity of this protein described previously in vitro (Cao et al, 2002; Czermin et al, 2002; Müller et al, 2002).

Wang et al (2004) suggest a model of hierarchical binding of PcG proteins, where E(z), recruited to PREs by the PcG protein Pho (Pleiohomeotic), creates a binding substrate for Pc-containing complexes in the PRE and by the formation of a loop, also in promoter regions. Then, PRC1 recruitment leads to the establishment of the repression of the target. Our data suggest that E(z) has an important role also in maintaining repression. Both the loss of E(z) and the loss of PRC1 components lead to the derepression of PcG target genes, as well as to the loss of repressive methylation marks (Breiling et al, 2001; Cao et al, 2002; Wang et al, 2004; this report). The presence of both proteins or protein complexes is necessary to maintain the repressed state of HOX genes. Thus, E(z) has an important function in maintenance, in particular in keeping the PcGspecific methylation marks. In addition, we show that E(z) is lost from PcG-repressed target promoters when PRC1 is disturbed. This suggests that the necessary interaction of E(z) with the target promoter region during maintenance depends also on PRC1, in particular Pc. Despite the fact that in late embryos E(z) and Pc are part of two distinct protein complexes (Poux et al, 2001), and both S2 and S3 cells stem from primary cultures of disaggregated late embryos (Cherbas & Cherbas, 1998), the two protein complexes still seem to communicate and even seem to depend on each other. This interdependence may provide the flexibility necessary to adapt maintained transcription patterns to new developmental situations.

Methods

Culture cell growth. S2 and S3 cells were grown in Schneider's Drosophila medium (Gibco) supplemented with 12.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). This strain of S2 cells does not express the Abd-B protein (Fig 1), in contrast to a strain used previously (Breiling et al, 2001). S2 cells used for RNAi were grown in serum-free insect culture medium (HyQ SFX, Hyclone).

Antibodies. Psc and Ph antibodies were described previously (Breiling et al, 2001). Antibodies against Pc, Tbp, Spt5, Spt6, E(z) and Abd-A were obtained from R. Paro, J. Kadonaga, F. Winston, R.S. Jones, I.W. Duncan and E. Sanchez-Herrero, respectively. The antibody against Pol II (8WG16) was from Covance, and that against Abd-B was from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank. Antisera to H3 di- or trimethylated at Lys 4 and trimethylated at Lys 9 were produced using the peptides ARTme2/3KQTARKSC and QTARtrimeKSTGGKC and specificity tested by inhibition ELISA as described (White et al, 1999; supplementary information online). Linear antibodies against trimethylated Lys 27 were obtained from F. Sauer. Branched antibodies against trimethylated Lys 9 and Lys 27 were obtained from T. Jenuwein; against dimethylated Lys 27 and dimethylated Lys 9 were from Upstate.

RT–PCR. Reverse transcription was performed with M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Ambion) using DNase-treated total RNA as template (1–2 μg per reaction) and a 16-mer polydT primer in the supplied buffer. The cDNA was PCR amplified using EuroTaq DNA polymerase (Euroclone) in the supplied buffer. Primer pairs were as follows: Abd-B: 5′-CTCCCCTCGCAATTACCAAAGG-3′, 5′-TGCCGTGTGCCGCTTGACCG-3′; abd-A: 5′-CAAATACAACGCAACCCGAGAC-3′, 5′-GTGGCATGTTGATAGAACTGAGC-3′; RPII144: 5′-CCTGCTGGATCGTGATTAACGC-3′, 5′-GTTGATGATGAAGTAGCCACCG-3′.

RNAi. Exonic pieces of approximately 1,400 bp from the Pc, ph and Psc genes were amplified by PCR, creating T7 polymerase binding sites for the transcription of both strands. RNAi was performed as described previously (Breiling et al, 2001).

ChIP. Chromatin was prepared as described by Boyd & Farnham (1999). S2 and S3 tissue culture cells were grown to a density of 3–6 × 106 per millilitre. Cells were fixed at 4°C for 10 min. After nuclei lysis, samples cooled on ice were sonicated in the presence of glass beads (150–200 μm; Sigma) 6 × for 30 s each with 30 s intervals. The sonicate was spun for 10 min at a maximum speed at 4°C, diluted to 0.2% SDS with dilution buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 140 mM NaCl), then aliquoted and used directly for IP. IP was performed as described (Breiling et al, 2001), with the following changes. For preclearing and antibody recovery, Protein A/G Plus-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used. After washing, 1 μg of RNase (DNase-free) was added to the samples and a nontreated aliquot of chromatin (input), and the tubes were incubated overnight at 65°C. Samples were adjusted to 0.5% SDS and 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K and incubated for an additional 3 h at 50°C. The material was phenol–chloroform extracted and precipitated. The final pellet was resuspended in 30 μl of TE and stored at 4°C for PCR analysis.

PCR analysis and quantification. PCR analysis was performed as described (Breiling et al, 2001). In addition, PCR reactions with 10, 1 and 0.1% of the input DNA were performed to determine the linear range of amplification. The following primer pairs were used: Abd-B (p10): 5′-CACTGGTGTGCGTGTGTGCG-3′, 5′-ATGATGGACTGGTGTTCTTGGC-3′; abd-A (p19b): 5′-AGCATAGCACTCAAAGCGGGG-3′, 5′-GAGTTTTGTCTGTCTACGGAGG-3′;Fab7-PRE-p7: 5′-TTAGTTGGTTGGTGAAACTGTGAG-3′, 5′-ATCCGACATCGTCCACAC-3′; Fab7-PRE-p8: 5′-TTCCCTGATCGCCTCGAC-3′, 5′-TACGAAACTGATGTTCTTGG-3′; Fab7-PRE-p9: 5′-GGTTCGGTAAGAGGTCTAC-3′, 5′-GAACTTCACAACAGACGACG-3′.

The primer pairs for the Abd-B and abd-A promoters have been described previously (Breiling et al, 2001). PCR gels were quantified with QuantityOne® software (Bio-Rad) and the results of at least two independent experiments for each cell type were plotted in diagrams as percentage of the input (normalized against the input).

Immunostainings. Cells were grown in chamber slides (Nunc), fixed for 4 min (4% formaldehyde, 0.2% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)), washed with PBSTT (0.2% Triton X-100, 0.2% Tween 20 in PBS) and blocked for 2 h with blocking solution (5% bovine serum albumin, 10% FBS, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.2% Tween 20 in PBS). The first antibody was applied overnight at 4°C in blocking solution and secondary antibodies (fluorescein isothiocyanate- or fluorescein tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit; Jackson) were applied for 1 h at room temperature in PBSTT. After each antibody incubation, the cells were washed three times with PBSTT. Cells were mounted in Aqua Poly/Mount (Polysciences).

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.nature.com/embor/journal/v5/n10/extref/7400260s1.pdf).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

We particularly thank L. Cherbas and P. Cherbas for S2 and S3 cultured cell lines. We are indebted to I.W. Duncan, T. Jenuwein, R.S. Jones, J. Kadonaga, R. Paro, E. Sanchez-Herrero, F. Sauer and F. Winston for providing antisera. This work was supported by Telethon, VolkswagenStiftung (I/77 996), AIRC, Italian Ministry for Education, University and Research (MIUR-FIRB) and La Compagnia di San Paolo to V.O. The Birmingham Laboratory is supported by BBSRC and Cancer Research UK. L.P.O'N. is a Royal Society Research Fellow.

References

- Beisel C, Imhof A, Greene J, Kremmer E, Sauer F (2002) Histone methylation by the Drosophila epigenetic transcriptional regulator Ash1. Nature 419: 857–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuchle D, Struhl G, Müller J (2001) Polycomb group proteins and heritable silencing of Drosophila Hox genes. Development 128: 993–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd KE, Farnham PJ (1999) Coexamination of sitespecific transcription factor binding and promoter activity in living cells. Mol Cell Biol 19: 8393–8399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiling A, Turner BM, Bianchi ME, Orlando V (2001) General transcription factors bind promoters repressed by Polycomb group proteins. Nature 412: 651–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao R et al. (2002) Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science 298: 1039–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherbas L, Cherbas P (1998), in Drosophila—A Practical Approach. Roberts DB (ed) pp 319–346. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Czermin B et al. (2002) Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell 111: 185–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellino GI et al. (2004) Polycomb silencing blocks transcription initiation. Mol Cell 13: 887–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W et al. (2003) Molecular basis for the discrimination of repressive methyl-lysine marks in histone H3 by Polycomb and HP1 chromodomains. Genes Dev 17: 1870–1881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis NJ, Kingston RE (2001) Mechanisms of transcriptional memory. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 409–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne M, Francis NJ, King IF, Kingston RE (2004) Propagation of silencing; recruitment and repression of naive chromatin in trans by polycomb repressed chromatin. Mol Cell 13: 415–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra RK et al. (2001) The iab-7 polycomb response element maps to a nucleosome-free region of chromatin and requires both GAGA and pleiohomeotic for silencing activity. Mol Cell Biol 21: 1311–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J et al. (2002) Histone methyltransferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell 111: 197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama J, Rice JC, Strahl BD, Allis CD, Grewal SI (2001) Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science 292: 110–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando V (2003) Polycomb, epigenomes, and control of cell identity. Cell 112: 599–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Burgos L et al. (2004) Generation and characterization of methyl-lysine histone antibodies. Methods Enzymol 376: 234–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters AH et al. (2003) Partitioning and plasticity of repressive histone methylation states in mammalian chromatin. Mol Cell 126: 1577–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poux S, Melfi R, Pirrotta V (2001) Establishment of Polycomb silencing requires a transient interaction between PC and ESC. Genes Dev 15: 2509–2514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z et al. (1999) Stabilization of chromatin structure by PRC1, a Polycomb complex. Cell 98: 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L et al. (2004) Hierarchical recruitment of polycomb group silencing complexes. Mol Cell 14: 637–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DA, Belyaev ND, Turner BM (1999) Preparation of sitespecific antibodies to acetylated histones. Methods 19: 417–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information