Abstract

To evaluate the effectiveness of UV irradiation in inactivating Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts, the animal infectivities and excystation abilities of oocysts that had been exposed to various UV doses were determined. Infectivity decreased exponentially as the UV dose increased, and the required dose for a 2-log10 reduction in infectivity (99% inactivation) was approximately 1.0 mWs/cm2 at 20°C. However, C. parvum oocysts exhibited high resistance to UV irradiation, requiring an extremely high dose of 230 mWs/cm2 for a 2-log10 reduction in excystation, which was used to assess viability. Moreover, the excystation ability exhibited only slight decreases at UV doses below 100 mWs/cm2. Thus, UV treatment resulted in oocysts that were able to excyst but not infect. The effects of temperature and UV intensity on the UV dose requirement were also studied. The results showed that for every 10°C reduction in water temperature, the increase in the UV irradiation dose required for a 2-log10 reduction in infectivity was only 7%, and for every 10-fold increase in intensity, the dose increase was only 8%. In addition, the potential of oocysts to recover infectivity and to repair UV-induced injury (pyrimidine dimers) in DNA by photoreactivation and dark repair was investigated. There was no recovery in infectivity following treatment by fluorescent-light irradiation or storage in darkness. In contrast, UV-induced pyrimidine dimers in the DNA were apparently repaired by both photoreactivation and dark repair, as determined by endonuclease-sensitive site assay. However, the recovery rate was different in each process. Given these results, the effects of UV irradiation on C. parvum oocysts as determined by animal infectivity can conclusively be considered irreversible.

Widespread low-level contamination of surface waters with Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts has been reported in many countries (10, 25). Cryptosporidiosis outbreaks arising from water supplies have been documented (1, 18), and it is believed that C. parvum oocysts are widespread in rivers. The concentration of C. parvum oocysts in source river waters can be as high as 104 oocysts per 100 liters (20, 29). Although coagulation-sedimentation and rapid sand filtration can remove C. parvum oocysts and reduce their numbers by 2 to 3 log units (11, 19), the expected rate of removal may not sufficiently reduce the risk of infection to an acceptable level in cases where the source water is highly contaminated. Chlorine has been used as a disinfectant in many water supplies; however, C. parvum oocysts are insensitive to the concentrations routinely used (7, 12, 17). Thus, there is interest in developing an alternative, more effective disinfectant for inactivating these recalcitrant microorganisms.

UV disinfection systems produce no hazardous by-products and are easy to maintain. The UV system is considered one of the more effective disinfection techniques for bacteria and viruses in drinking water and wastewater (26). Although there have been many studies on UV inactivation of microorganisms such as Escherichia coli (14), relatively few studies on UV inactivation of C. parvum have been conducted. This is because, based on assessment by in vitro excystation and vital-dye methods, UV irradiation was considered ineffective in inactivating C. parvum (2, 23, 27). However, evidence based on assessment by cell culture techniques suggests that the present practice of UV irradiation at low doses may effectively inactivate C. parvum oocysts (4, 21).

A problem with UV disinfection is that some microorganisms have the ability to repair DNA lesions by mechanisms such as photoreactivation and dark repair (8, 9, 22, 33). Photoreactivation is a phenomenon in which UV-inactivated microorganisms recover activity through the repair of lesions in the DNA by enzymes under near-UV light. Photoreactivation may occur in microorganisms in UV-exposed wastewater after its discharge to watersheds, because UV-inactivated microorganisms would normally be exposed to sunlight, including near-UV light. In dark repair, UV-inactivated microorganisms repair the damaged DNA in the absence of light. Dark repair may occur in UV-exposed drinking water after it is distributed by water supply systems. Therefore, in order to achieve an appropriate UV disinfection level, it is necessary to quantitatively evaluate the effects of photoreactivation and dark repair. However, the ability of C. parvum to perform photoreactivation and dark repair following UV irradiation has not yet been clarified, despite the importance of these mechanisms in the inactivation of C. parvum by UV irradiation technology.

Inactivation of microorganisms by UV irradiation occurs through the formation of lesions in DNA, and the dominant UV-induced lesion is cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (8). The presence of UV-induced lesions would prevent normal DNA replication, leading to inactivation. In previous studies, photoreactivation and dark repair in C. parvum were investigated by the endonuclease-sensitive site (ESS) assay, which can determine the number of UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in the genomic DNA (24, 31). The results indicated that C. parvum has the ability to carry out photoreactivation and dark repair at the genomic level.

In this study, we sought to elucidate the efficacy of UV irradiation at various temperatures and intensities as well as to assess the effects of visible-light irradiation or dark storage after UV irradiation by use of animal infectivity, in vitro excystation, and the ESS assay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. parvum oocysts.

The C. parvum strain HNJ-1 (a human isolate recovered by M. Iseki, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan), which was passaged in SCID mice (C.B-17/Icr; CLEA Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) at the Research Institute of Biosciences, Azabu University, was used for this study. Fresh feces from several infected mice were placed in 500 ml of purified water, emulsified, and filtered through a 0.1-mm-mesh nylon sieve. A crude oocyst suspension (20 ml) was underlaid with a sucrose solution (specific gravity, 1.10 at 20°C) and centrifuged at 1,500 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The interface and upper layer were recovered and diluted with 150 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, comprising 0.20 g of potassium dihydrogen phosphate, 0.20 g of potassium chloride, 1.15 g of disodium hydrogen phosphate, and 8.0 g of sodium chloride in 1 liter of distilled water) containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 80. The diluted solution was centrifuged at 1,500 × g and 4°C for 15 min. The precipitate was diluted to 20 ml with PBS containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 80. The suspension was underlaid with a sucrose solution and centrifuged at 1,500 × g and 4°C for 15 min. The interface was recovered. Washing with PBS containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 80 was repeated four times to remove fecal matter. The stock of purified oocysts was stored in PBS at 4°C and used in experiments within 10 days.

UV irradiation.

The UV irradiation conditions for each experiment are shown in Table 1. A small portion of a purified suspension of C. parvum oocysts was placed in an open plastic petri dish (inner diameter, 56 mm) containing 10 ml of 150 mM PBS to produce a final concentration of 106 oocysts per ml. Since the extinction coefficient was 0.050 cm−1 at 254 nm and the loss of UV intensity in a 4.0-mm thickness of the oocyst suspension was only 2%, the UV intensity at the surface of the oocyst suspension was regarded as the UV intensity in the entire suspension layer.

TABLE 1.

Summary of experimental conditions

| Trial no. | UV intensity (mW/cm2) | Irradiation time (s) | UV dose (mWs/cm2) | Temp (°C) | Evaluation methoda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.24 | 5 | 1.20 | 5 | AI |

| 2 | 0.24 | 5 | 1.20 | 10 | AI |

| 3 | 0.24 | 5 | 1.20 | 30 | AI |

| 4 | 0.24 | 7 | 1.68 | 5 | AI |

| 5 | 0.24 | 7 | 1.68 | 10 | AI |

| 6 | 0.24 | 7 | 1.68 | 30 | AI |

| 7 | 0.24 | 10 | 2.40 | 5 | AI |

| 8 | 0.24 | 10 | 2.40 | 10 | AI |

| 9 | 0.24 | 10 | 2.40 | 30 | AI |

| 10 | 0.048 | 25 | 1.20 | 20 | AI |

| 11 | 0.12 | 10 | 1.20 | 20 | AI |

| 12 | 0.60 | 2 | 1.20 | 20 | AI |

| 13 | 0.048 | 38 | 1.82 | 20 | AI |

| 14 | 0.12 | 15 | 1.80 | 20 | AI |

| 15 | 0.60 | 3 | 1.80 | 20 | AI |

| 16 | 0.048 | 50 | 2.40 | 20 | AI |

| 17 | 0.12 | 20 | 2.40 | 20 | AI |

| 18 | 0.60 | 4 | 2.40 | 20 | AI |

| 38 | 0.24 | 167 | 40.0 | 20 | Ex |

| 39 | 0.24 | 167 | 40.0 | 20 | Ex |

| 40 | 0.24 | 333 | 80.0 | 20 | Ex |

| 41 | 0.24 | 333 | 80.0 | 20 | Ex |

| 42 | 0.24 | 500 | 120 | 20 | Ex |

| 43 | 0.24 | 500 | 120 | 20 | Ex |

| 44 | 0.24 | 667 | 160 | 20 | Ex |

| 45 | 0.24 | 667 | 160 | 20 | Ex |

| 46 | 0.24 | 1,000 | 240 | 20 | Ex |

| 47 | 0.24 | 1,000 | 240 | 20 | Ex |

| C-1b | Not irradiated | AI | |||

| C-2 | Not irradiated | AI | |||

| C-3 | Not irradiated | AI | |||

| C-4 | Not irradiated | AI |

AI, animal infectivity; Ex, in vitro excystation.

C, Control samples for MPN0 in animal infectivity.

The dish was placed under a 5-W low-pressure mercury lamp (QCGL5W-14 97D; Iwasaki Electronic, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The intensity of the UV light at a wavelength of 253.7 nm ranged from 0.048 to 0.60 mW/cm2, as measured by a UV dose rate meter (UTI-150-A; Ushio Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The dose of UV irradiation was altered by controlling the exposure time. The oocyst suspension was gently mixed by using an electromagnetic stirrer during UV irradiation.

Fluorescent-light irradiation and storage in the dark.

Table 2 summarizes the experimental conditions of UV irradiation and the subsequent recovery treatments. Immediately after UV irradiation, one group was exposed to fluorescent light by use of a 15-W fluorescent lamp (FL15N white-light fluorescent lamp; Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan). The intensity of the fluorescent light at a wavelength of 360 nm was measured by a UV-A region dosimeter (UVR-2 with UD-36; TOPCON, Tokyo, Japan). Throughout the duration of fluorescent-light irradiation, the oocyst suspension was gently mixed by using an electromagnetic stirrer. Another group was covered with aluminum foil and incubated at 20°C for 4 to 24 h.

TABLE 2.

Experimental conditions of UV irradiation and subsequent recovery treatments

| Trial no. | UV intensity (mW/cm2) | Irradiation time (s) | UV dose (mWs/cm2) | Temp (°C) | Treatment after UV irradiation

|

Evaluationb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLa dose (mWs/cm2) | Storage duration (h) | ||||||

| 19 | 0.10 | 5 | 0.50 | 20 | Not treated | AI, ESS | |

| 20 | 0.10 | 5 | 0.50 | 20 | 150 | AI, ESS | |

| 21 | 0.10 | 5 | 0.50 | 20 | 300 | AI, ESS | |

| 22 | 0.10 | 5 | 0.50 | 20 | 12 | AI, ESS | |

| 23 | 0.10 | 5 | 0.50 | 20 | 24 | AI, ESS | |

| 24 | 0.10 | 10 | 1.00 | 20 | Not treated | AI, ESS | |

| 25 | 0.10 | 10 | 1.00 | 20 | 150 | AI, ESS | |

| 26 | 0.10 | 10 | 1.00 | 20 | 300 | AI, ESS | |

| 27 | 0.10 | 10 | 1.00 | 20 | 12 | AI, ESS | |

| 28 | 0.10 | 10 | 1.00 | 20 | 24 | AI, ESS | |

| 29 | 0.10 | 15 | 1.50 | 20 | Not treated | AI, ESS | |

| 30 | 0.10 | 15 | 1.50 | 20 | Not treated | AI, ESS | |

| 31 | 0.10 | 15 | 1.50 | 20 | 180 | AI, ESS | |

| 32 | 0.10 | 15 | 1.50 | 20 | 360 | AI, ESS | |

| 33 | 0.10 | 15 | 1.50 | 20 | 540 | AI, ESS | |

| 34 | 0.10 | 15 | 1.50 | 20 | 720 | AI, ESS | |

| 35 | 0.10 | 15 | 1.50 | 20 | 4 | AI, ESS | |

| 36 | 0.10 | 15 | 1.50 | 20 | 12 | AI, ESS | |

| 37 | 0.10 | 15 | 1.50 | 20 | 24 | AI, ESS | |

FL, fluorescent light.

AI, animal infectivity.

Infectivity.

Infectivity was determined via animal infectivity tests with SCID mice in a specific-pathogen-free area at the Research Institute of Biosciences, Azabu University. This study was approved by the Animal Research Committee of Azabu University. Five-week-old SCID mice were used for the tests after 1 week of conditioning for adaptation to the new cage. Mice were individually housed in cages and provided autoclave-sterilized food and water. Three to eight mice were used per dilution. Fivefold serial dilutions were made using sterilized tap water. A 0.5-ml aliquot of a selected dilution series was administered orally to the mouse. The mortality of the mice at the early stage of the experiments was 2 out of 789 mice; no mouse died beyond 1 week after oral administration. Four weeks after oral administration, fresh feces were collected, suspended in 50 ml of purified water, and emulsified using a vortex mixer. A 5-ml portion of the suspension was overlaid on 8 ml of a sucrose solution and centrifuged at 1,500 × g and 4°C for 15 min. The interface was recovered, and approximately 1 ml of the supernatant was filtered through a 25-mm cellulose acetate membrane disk filter (pore size, 0.8 μm). The filter was then stained using immunofluorescent antibodies against oocyst wall protein (Hydrofluoro Combo Kit; Strategic Diagnostics Inc., Newark, Del.) and observed under an epifluorescent, differential-contrast microscope (BX-60; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at a magnification of ×400 to determine the presence or absence of oocysts. The most probable number (MPN) of infection was calculated from oocyst-positive mice by using the MPN program developed by Hurley and Roscoe (15). The relative infectivity of each sample was calculated as MPNa/MPN0, where MPNa is the MPN of oocysts after UV irradiation and MPN0 is the MPN of oocysts before UV irradiation.

In the animal infectivity test, the dark repair process was monitored closely, as it occurred in the interval between the time immediately after UV irradiation of oocysts and the time at which oocysts reached the infection site. Thus, the results include the effect of the dark repair process.

In vitro excystation.

The viability of the oocysts was determined by a modification of Woodmansee's method (35). The original excystation protocol was modified slightly by addition of a 5-min preincubation at 37°C in acidified Hank's balanced salt solution (pH 2.75) prior to incubation for excystation. After the preincubation period, the oocysts were incubated in the excystation medium at 37°C for 60 min.

The numbers of intact oocysts (IO) before excystation treatment, partially excysted oocysts (PO), empty oocysts (EO), and free sporozoites (S) were enumerated under a phase-contrast microscope at a magnification of ×400. Excystation rate (V) was calculated as  . The survival ratio (Sr) was calculated as Va/V0, where Va is the excystation rate of the UV-irradiated sample and V0 is the excystation rate of the control sample (before UV irradiation).

. The survival ratio (Sr) was calculated as Va/V0, where Va is the excystation rate of the UV-irradiated sample and V0 is the excystation rate of the control sample (before UV irradiation).

ESS assay.

A C. parvum suspension was frozen in liquid nitrogen for 3 min and then thawed at 95°C for 5 min to break the oocyst walls (P. A. Rochelle, D. M. Ferguson, T. J. Handojo, R. De Leon, M. H. Stewart, and R. L. Wolfe, abstract from the Fourth International Workshops on Opportunitistic Protists, J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 43:72S, 1996). The DNA was then extracted by the Genomic-tip DNA extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.). UV endonuclease was prepared from Micrococcus luteus by using the method for the preparation of fraction II originally described by Carrier and Setlow (3). The DNA solution was incubated with the UV endonuclease at 37°C for 45 min in 30 mM Tris (pH 8.0)-40 mM NaCl-1 mM EDTA in order to incise the nicks at the site of the pyrimidine dimer. The reaction was stopped by addition of concentrated alkaline loading dye to a final concentration of 100 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5% Ficoll, and 0.05% bromocresol green. The sample was electrophoresed at 0.4 V/cm for 15 h on 0.35% alkaline agarose gels in a solution containing 30 mM NaOH and 1 mM EDTA. 7GT (bacteriophage T4dC+T4dC/BglI digest mixture; Wako, Tokyo, Japan) and 8GT (bacteriophage T4dC+T4dC/BglII digest mixture; Wako) were used as molecular-length markers. The gel was neutralized and stained in an ethidium bromide solution overnight to stain the DNA. The stained gel was photographed (Gel Doc 1000; Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) and analyzed (Molecular Analyst software; Bio-Rad). The midpoint of the DNA mass, that is, the median migration distance of each sample, was graphically determined to be the representative migration distance of the sample. The median migration distance was converted to the median molecular length (Lmed) of the DNA by means of the quadratic regression curve obtained from analysis of the molecular standards. The average molecular length (Ln) of the DNA was calculated as 0.6 × Lmed (calculation from Veatch and Okada [32]). The number of ESSs per base was calculated as [1/Ln(+UV)] − [1/Ln(−UV)], where Ln(+UV) and Ln(−UV) are the Lns of the UV-irradiated and nonirradiated samples, respectively (calculation from Freeman et al. [6]).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Efficacy of UV irradiation.

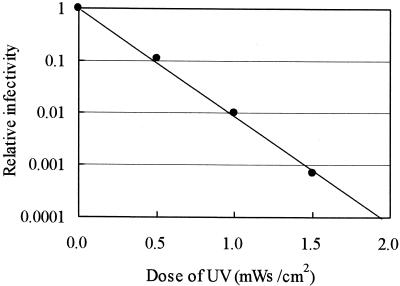

The number of orally administered oocysts, infection rate among mice, MPN, 95% confidence interval, and relative infectivity are shown in Table 3. The reduction in infectivity of C. parvum oocysts with UV irradiation at 20°C is shown in Fig. 1. Infectivity decreased exponentially as the UV dose increased. The UV doses required for 1-, 2-, and 4-log10 reductions in infectivity were 0.48, 0.97 and 1.92 mWs/cm2, respectively. The doses resulting in reductions in infectivity in this study were approximately half of the previously reported doses based on assessment by cell culture (4, 21, 30). It has been reported that sensitivity to disinfectants varies among different strains of C. parvum (28). The reason that the effective dose of irradiation was about half of the reported values might be related to differences in the experimental conditions, including the use of different strains of C. parvum and/or differences between in vitro cell culture methods and in vivo animal infectivity experiments. Our dose of UV irradiation is much lower than the minimum dose of 16 mWs/cm2 recommended for a 2-log10 reduction of bacteria by the U.S. Public Health Service. Therefore, if the minimum dose is maintained at 16 mWs/cm2, it can be expected to result in more than 10-log10 inactivation of C. parvum oocysts. These results suggest that UV irradiation is a highly effective disinfectant technique for inactivating C. parvum oocysts from the perspective of reducing infectivity.

TABLE 3.

Summary of C. parvum infectivity in SCID mice for each trial

| Trial no.a | Inoculumb (no. of positive mice/total no. of mice) | MPN | 95% confidence interval | Relative infectivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-1 | 9 (1/5), 49 (3/4), 203 (4/5), 1,010 (5/5) | 1.33 × 10−2 | 5.56 × 10−3 to 3.19 × 10−2 | 1.00 × 100 |

| 1 | 149 (1/5), 745 (3/5), 3,725 (5/5), 18,625 (5/5) | 1.63 × 10−4 | 5.45 × 10−5 to 4.90 × 10−4 | 1.23 × 10−2 |

| 2 | 126 (0/3), 630 (0/3), 3,150 (0/3), 15,750 (2/3), 78,750 (3/3) | 5.33 × 10−5 | 1.72 × 10−5 to 1.65 × 10−4 | 4.01 × 10−3 |

| 3 | 122 (0/3), 608 (0/3), 3,038 (0/3), 15,188 (1/3), 75,938 (3/3) | 3.37 × 10−5 | 1.13 × 10−5 to 1.01 × 10−4 | 2.53 × 10−3 |

| 8 | 127 (0/3), 634 (0/3), 3,169 (0/3), 15,844 (0/3), 79,219 (1/3) | 3.91 × 10−7 | 5.62 × 10−8 to 2.72 × 10−6 | 2.94 × 10−5 |

| 10 | 120 (0/3), 600 (0/3), 3,000 (0/3), 15,000 (2/3), 75,000 (3/3) | 5.60 × 10−5 | 1.81 × 10−5 to 1.74 × 10−4 | 4.21 × 10−3 |

| 11 | 120 (0/3), 600 (1/3), 3,000 (2/3), 15,000 (2/3), 75,000 (3/3) | 1.54 × 10−4 | 5.16 × 10−5 to 4.63 × 10−4 | 1.16 × 10−2 |

| 12 | 144 (0/3), 720 (1/3), 3,600 (3/3), 18,000 (3/3), 90,000 (3/3) | 7.15 × 10−4 | 2.38 × 10−4 to 2.15 × 10−3 | 5.38 × 10−2 |

| 17 | 126 (0/3), 631 (0/3), 3,156 (0/3), 15,781 (0/3), 78,906 (1/3) | 3.93 × 10−7 | 5.65 × 10−8 to 2.74 × 10−6 | 2.95 × 10−5 |

| 18 | 149 (0/3), 746 (0/3), 3,731 (0/3), 18,656 (3/3), 93,281 (3/3) | 8.66 × 10−6 | 2.82 × 10−6 to 2.66 × 10−5 | 6.51 × 10−4 |

| C-2 | 5 (0/8), 24 (1/8), 121 (4/5), 604 (5/5) | 9.49 × 10−3 | 4.14 × 10−3 to 2.18 × 10−2 | 1.00 × 100 |

| 4 | 5,625 (0/5), 28,125 (2/5), 140,625 (4/5), 703,125 (5/5) | 1.24 × 10−5 | 5.22 × 10−6 to 2.97 × 10−5 | 1.31 × 10−3 |

| 5 | 6,850 (0/5), 34,250 (3/5), 171,250 (3/5), 856,250 (5/5) | 8.74 × 10−6 | 3.62 × 10−6 to 2.11 × 10−5 | 9.21 × 10−4 |

| 6 | 6,088 (0/5), 30,438 (0/5), 152,188 (3/5), 760,940 (5/5) | 6.22 × 10−6 | 2.56 × 10−6 to 1.51 × 10−5 | 6.55 × 10−4 |

| 13 | 6,700 (2/5), 33,500 (2/5), 167,500 (3/5), 837,500 (5/5) | 1.04 × 10−5 | 4.34 × 10−6 to 2.48 × 10−5 | 1.10 × 10−3 |

| 14 | 6,700 (1/5), 33,500 (4/5), 167,500 (5/5), 837,500 (5/5) | 4.38 × 10−5 | 1.77 × 10−5 to 1.09 × 10−4 | 4.62 × 10−3 |

| 15 | 6,750 (0/5), 33,750 (0/5), 168,750 (1/5), 843,750 (5/5) | 2.54 × 10−6 | 1.08 × 10−6 to 5.96 × 10−6 | 2.68 × 10−4 |

| C-3 | 9 (1/5), 39 (3/5), 203 (4/5), 1,010 (5/5) | 1.29 × 10−2 | 5.44 × 10−3 to 3.04 × 10−2 | 1.00 × 100 |

| 19 | 149 (1/5), 745 (3/5), 3,725 (5/5), 18,625 (5/5) | 1.35 × 10−3 | 5.44 × 10−4 to 3.34 × 10−3 | 1.05 × 10−1 |

| 20 | 134 (1/5), 670 (3/5), 3,350 (5/5), 16,750 (5/5) | 1.50 × 10−3 | 6.04 × 10−4 to 3.72 × 10−3 | 1.16 × 10−1 |

| 21 | 153 (1/5), 765 (3/5), 3,825 (5/5), 19,125 (5/5) | 1.31 × 10−3 | 5.29 × 10−4 to 3.25 × 10−3 | 1.02 × 10−1 |

| 22 | 155 (1/5), 776 (3/5), 3,880 (5/5), 19,400 (5/5) | 1.29 × 10−3 | 5.22 × 10−4 to 3.21 × 10−3 | 1.00 × 10−1 |

| 23 | 161 (1/5), 805 (3/5), 4,025 (5/5), 20,125 (5/5) | 1.25 × 10−3 | 5.03 × 10−4 to 3.09 × 10−3 | 9.69 × 10−2 |

| 24 | 269 (1/5), 1,345 (1/5), 6,725 (2/5), 33,625 (5/5) | 1.29 × 10−4 | 5.35 × 10−5 to 3.12 × 10−4 | 1.00 × 10−2 |

| 25 | 805 (1/5), 4,025 (3/5), 20,125 (4/5), 100,625 (5/5) | 1.30 × 10−4 | 5.48 × 10−5 to 3.06 × 10−4 | 1.01 × 10−2 |

| 26 | 755 (2/5), 3,775 (2/5), 18,875 (4/5), 94,375 (5/5) | 1.33 × 10−4 | 5.64 × 10−5 to 3.15 × 10−4 | 1.03 × 10−2 |

| 27 | 759 (1/5), 3,794 (3/5), 18,970 (4/5), 94,850 (5/5) | 1.37 × 10−4 | 5.81 × 10−5 to 3.25 × 10−4 | 1.06 × 10−2 |

| 28 | 755 (1/5), 3,775 (3/5), 18,875 (4/5), 94,375 (5/5) | 1.38 × 10−4 | 5.84 × 10−5 to 3.26 × 10−4 | 1.07 × 10−2 |

| C-4 | 8 (2/5), 40 (3/5), 250 (4/5), 1,350 (5/5) | 1.32 × 10−2 | 5.29 × 10−3 to 3.30 × 10−2 | 1.00 × 100 |

| 29 | 3,220 (0/5), 16,100 (0/5), 80,500 (3/5), 402,500 (5/5) | 9.45 × 10−6 | 3.95 × 10−6 to 2.26 × 10−5 | 7.16 × 10−4 |

| 30 | 3,170 (0/5), 15,850 (0/5), 79,250 (3/5), 396,250 (5/5) | 9.60 × 10−6 | 4.01 × 10−6 to 2.30 × 10−5 | 7.27 × 10−4 |

| 31 | 2,207 (0/5), 11,033 (1/5), 55,165 (1/5), 275,825 (5/5), 1,379,125 (5/5) | 9.74 × 10−6 | 4.15 × 10−6 to 2.28 × 10−5 | 7.38 × 10−4 |

| 32 | 2,265 (0/5), 11,325 (0/5), 56,625 (2/5), 283,125 (5/5), 1,415,625 (5/5) | 9.99 × 10−6 | 4.25 × 10−6 to 2.35 × 10−5 | 7.57 × 10−4 |

| 33 | 2,447 (0/5), 12,233 (0/5), 61,165 (2/5), 305,825 (4/4), 1,529,125 (5/5) | 8.87 × 10−6 | 3.61 × 10−6 to 2.18 × 10−5 | 6.72 × 10−4 |

| 34 | 2,500 (0/5), 12,500 (0/5), 62,500 (2/5), 312,500 (5/5), 1,562,500 (5/5) | 9.05 × 10−6 | 3.85 × 10−6 to 2.13 × 10−5 | 6.86 × 10−4 |

| 35 | 2,336 (0/5), 11,680 (0/5), 58,400 (2/5), 292,000 (5/5), 1,460,000 (5/5) | 9.69 × 10−6 | 4.12 × 10−6 to 2.28 × 10−5 | 7.34 × 10−4 |

| 36 | 2,253 (0/5), 11,266 (1/5), 56,330 (1/5), 281,650 (5/5), 1,408,250 (5/5) | 9.75 × 10−6 | 4.12 × 10−6 to 2.31 × 10−5 | 7.39 × 10−4 |

| 37 | 2,200 (0/5), 11,000 (1/5), 55,000 (3/5), 275,000 (4/5), 1,375,000 (5/5) | 9.32 × 10−6 | 3.98 × 10−6 to 2.18 × 10−5 | 7.06 × 10−4 |

C-1, control for trials 1, 2, 3, 8, 10, 11, 12, 17, and 18; C-2, control for trials 4, 5, 6, 13, 14, and 15; C-3, control for trials 19 through 28; C-4, control for trials 29 through 37.

Number of oocysts per mouse.

FIG. 1.

Relationship between the relative infectivity of C. parvum oocysts and the UV irradiation dose.

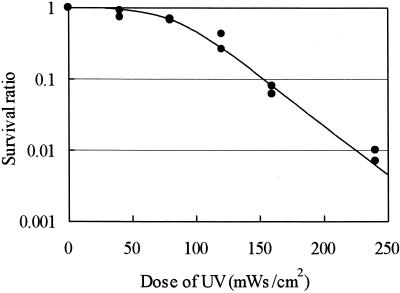

The reduction in the viability of C. parvum oocysts by UV treatment as assessed by excystation is shown in Fig. 2. The 6-hit series event model (34) was used as the mathematical model because viability decreased only slightly at the low dose range (<100 mWs/cm2). The estimated UV dose for a 2-log10 reduction in viability at 20°C was 230 mWs/cm2, which is approximately 200 times higher than the dose required for an equivalent reduction in infectivity. Hirata et al. reported that the CT (product of concentration of disinfectant and contact time) values of chemical disinfectants required for equivalent reductions in the infectivity and the viability of C. parvum differed by a factor of 18 for chlorine (12) and by a factor of 3 for ozone (13). The present study showed a marked difference between the effect of UV irradiation on the infectivity of C. parvum and the effect on its viability. This large difference between the UV requirement for reducing infectivity and that for reducing excystation suggests that a large percentage of C. parvum oocysts exposed to a low dose of UV irradiation are able to excyst but not infect. Although the excystation assay may prove to be a useful measure of disinfection with respect to oocyst viability, it cannot distinguish between infective and noninfective oocysts (12). Thus, the animal infectivity experiment is the most appropriate evaluation method, given that the primary area of interest is the infectivity of C. parvum oocysts. Therefore, in assessing the degree of inactivation by a water treatment process from the perspective of public health, the efficacy of a disinfectant should be evaluated by its effect on infectivity.

FIG. 2.

Relationship between the survival ratio as assessed by in vitro excystation of C. parvum oocysts and the UV irradiation dose.

Effects of temperature and intensity.

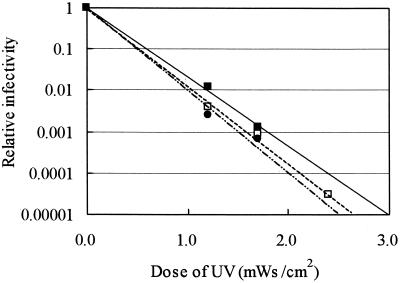

The reductions in infectivity observed at various temperatures are shown in Fig. 3. The UV doses resulting in a 2-log10 reduction in infectivity at 5, 10, and 30°C were 1.20, 1.07, and 1.02 mWs/cm2, respectively. The observed increase in the dose required for a 2-log10 reduction in infectivity was only 7% for every 10°C reduction in water temperature. The CT requirement of chemical disinfectants generally depends on both the temperature and the concentration of the disinfectant (5, 13). For instance, the temperature factor of ozone has been reported to be as high as 4.09 (16) or 4.20 (13) for every 10°C reduction in temperature. However, temperature did not significantly affect the efficacy of UV irradiation in reducing the infectivity of oocysts in this study.

FIG. 3.

Effect of water temperature on the relative infectivities of C. parvum oocysts exposed to increasing UV dosages. Symbols: ▪, 5°C; □, 10°C; •, 30°C.

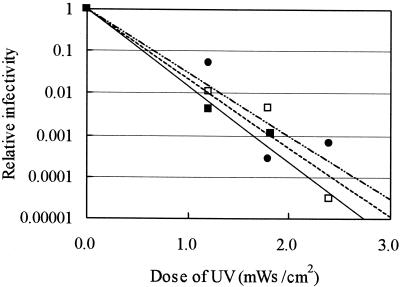

The reductions in infectivity observed at various irradiation intensities are shown in Fig. 4. The UV doses required for a 2-log10 reduction in infectivity at intensities of 0.048, 0.12, and 0.60 mW/cm2 were 1.15, 1.20, and 1.34 mWs/cm2, respectively, indicating that only an 8% increase in the UV dose was required with a 10-fold increase in intensity. These results showed that the disinfecting effect of UV on C. parvum oocysts was dependent on the actual irradiation dose only.

FIG. 4.

Effect of irradiation intensity on the relative infectivities of C. parvum oocysts exposed to increasing UV dosages. Symbols: ▪, 0.048 mW/cm2; □, 0.12 mW/cm2; •, 0.60 mW/cm2.

Thus, in practice, UV irradiation can be used to inactivate C. parvum oocysts in water without considering the effects of either water temperature or irradiation intensity.

Photoreactivation and dark repair in C. parvum following UV inactivation.

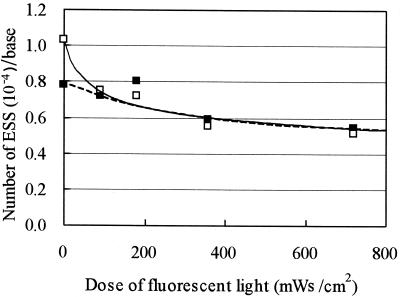

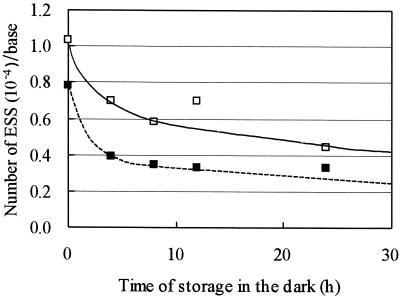

The reduction in infectivity of C. parvum oocysts induced by UV irradiation might not be permanent, because the DNA lesions of some microorganisms may be repaired by photoreactivation or dark repair (9). Figure 5 shows the number of ESSs per base in UV-inactivated oocysts after exposure to fluorescent light. The UV-induced pyrimidine dimers were gradually repaired as the time of exposure to fluorescent light increased. The number of ESSs decreased by approximately 30 to 50% after fluorescent-light irradiation at a dose of 720 mWs/cm2. Figure 6 shows the number of ESSs in UV-inactivated oocysts after dark storage for various durations. The UV-induced pyrimidine dimers were gradually repaired during storage in the dark. Nonetheless, the number of ESSs decreased more slowly during dark storage than during the photoreactivation process. Upon storage in the dark for 24 h, the number of ESSs decreased by approximately 60%, indicating that C. parvum has the ability to repair the pyrimidine dimers in the genomic DNA during either exposure to fluorescent light or storage in the dark.

FIG. 5.

Relationship between the number of ESSs and the dosage of fluorescent-light irradiation in UV-irradiated (at 0.50 or 1.00 mWs/cm2) C. parvum oocysts. Symbols: ▪, 0.50 mWs/cm2; □, 1.00 mWs/cm2.

FIG. 6.

Relationship between the number of ESSs and the duration of dark storage in UV-irradiated (at 0.50 or 1.00 mWs/cm2) C. parvum oocysts. Symbols: ▪, 0.50 mWs/cm2; □, 1.00 mWs/cm2.

Table 4 shows the results of the animal infectivity test for oocysts that had been exposed to fluorescent light after UV inactivation. Exposure to UV irradiation of 0.50, 1.00, or 1.50 mWs/cm2 alone led to a 0.98-, 2.00-, or 3.15-log10 reduction in infectivity, respectively. The degree of reduction in infectivity following photoreactivation in samples that had been exposed to fluorescent light at a dose of 150 to 720 mWs/cm2 after UV irradiation did not change.

TABLE 4.

Infectivity in SCID mice of C. parvum oocysts exposed to fluorescent light after UV inactivation

| UV irradiation dose (mWs/cm2) | Fluorescent-light dose (mWs/cm2) | Log10 reduction |

|---|---|---|

| 0.50 | 0 | 0.98 |

| 0.50 | 150 | 0.93 |

| 0.50 | 300 | 0.99 |

| 1.00 | 0 | 2.00 |

| 1.00 | 150 | 2.00 |

| 1.00 | 300 | 1.98 |

| 1.50 | 0 | 3.15 |

| 1.50 | 180 | 3.13 |

| 1.50 | 360 | 3.12 |

| 1.50 | 540 | 3.17 |

| 1.50 | 720 | 3.16 |

Table 5 shows the results of the animal infectivity test for oocysts that had been stored in the dark after inactivation by UV irradiation. A dark repair period of 4 to 24 h did not change the degree of inactivation of C. parvum which had been UV irradiated at 0.5, 1.0, or 1.5 mWs/cm2, based on the animal infectivity experiments.

TABLE 5.

Infectivity in SCID mice of C. parvum oocysts stored in the dark after UV inactivation

| UV irradiation dose (mWs/cm2) | Storage duration (h) | Log10 reduction |

|---|---|---|

| 0.50 | 0 | 0.98 |

| 0.50 | 12 | 1.00 |

| 0.50 | 24 | 1.01 |

| 1.00 | 0 | 2.00 |

| 1.00 | 12 | 1.97 |

| 1.00 | 24 | 1.97 |

| 1.50 | 0 | 3.15 |

| 1.50 | 4 | 3.13 |

| 1.50 | 12 | 3.13 |

| 1.50 | 24 | 3.15 |

Even though UV-inactivated C. parvum oocysts underwent photoreactivation or dark repair upon exposure to fluorescent light or storage in the dark, respectively, as observed in the ESS study, the infectivity of C. parvum oocysts did not change after either treatment. These results indicate that C. parvum did not recover its infectivity following either photoreactivation or dark repair, although recovery was seen at the DNA level.

The reasons for this are as follows. (i) Immediately after UV irradiation of oocysts, the dark repair process begins. Therefore, the results of the photoreactivation experiment also include the effects of the dark repair process. (ii) Although considerable recovery at the DNA level may occur during photoreactivation or dark repair, some lesions at the DNA level remain, and those lesions may inhibit the progression of the life cycle. (iii) Other damage induced by UV irradiation aside from pyrimidine dimers could not be repaired by photoreactivation and dark repair and might play an important role in infection. From these results, we conclude that UV-irradiated oocysts cannot proceed with their life cycle even if they are placed in the presence or absence of visible light.

Conclusions.

The results of the present study can be summarized as follows.

(i) The infectivity of C. parvum HNJ-1 oocysts decreased exponentially as the UV irradiation dose increased. The UV dose required for a 2-log10 reduction in infectivity was only 1.0 mWs/cm2.

(ii) The dose required for a 2-log10 reduction in viability as assessed by in vitro excystation was approximately 200 times higher than that required for a 2-log10 reduction in infectivity, suggesting that C. parvum oocysts exposed to low-dose UV irradiation are able to excyst but not infect.

(iii) Neither water temperature nor UV intensity significantly affected the reduction in the infectivity of UV-irradiated C. parvum oocysts.

(iv) The ESS study revealed that when UV-inactivated C. parvum oocysts were exposed to fluorescent light or stored in the dark, photoreactivation or dark repair, respectively, occurred; however, the infectivity of C. parvum oocysts was not restored. These results indicate that the life cycle of UV-irradiated oocysts cannot proceed even when they are placed in the presence or absence of visible light.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a 2001 Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research category (B)(2) (grant 13450217) and, in part, by a 2000 and 2001 Grant-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Scientists (grant 12750501) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atherton, F., C. Newman, and D. Casemore. 1995. An outbreak of waterborne cryptosporidiosis associated with a water supply in the UK. Epidemiol. Infect. 115:123-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell, A. T., L. J. Robertson, M. R. Snowball, and H. V. Smith. 1995. Inactivation of oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum by ultraviolet irradiation. Water Res. 29:2583-2586. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrier, W. L., and R. B. Setlow. 1970. Endonuclease from Micrococcus luteus which has activity toward ultraviolet-irradiated deoxyribonucleic acid: purification and properties. J. Bacteriol. 102:178-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clancy, J. 2000. UV rises to the Cryptosporidium challenge. Water 21 10:14-16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finch, G. R., E. K. Black, L. Gyurek, and M. Belosevic. 1993. Ozone inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum in demand-free phosphate buffer determined by in vitro excystation and animal infectivity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:4203-4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman, S. E., A. D. Blackett, D. C. Monteleone, R. B. Setlow, B. M. Sutherland, and J. C. Sutherland. 1986. Quantitation of radiation-, chemical-, or enzyme-induced single strand breaks in nonradioactive DNA by alkaline gel electrophoresis: application of pyrimidine dimers. Anal. Biochem. 158:119-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gyurek, L. L., G. R. Finch, and M. Belosevic. 1997. Modeling chlorine inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. J. Environ. Eng. 9:865-875. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harm, W. 1980. Biological effects of ultraviolet radiation, p. 31-39. Cambridge University Press, New York, N.Y..

- 9.Harris, G. D., V. D. Adams, D. L. Sorensen, and M. S. Curtis. 1987. Ultraviolet inactivation of selected bacteria and viruses with photoreactivation of the bacteria. Water Res. 21:687-692. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashimoto, A., and T. Hirata. 1999. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts in Sagami river, Japan, p. 956-961. In Preprint of the 1999 IAWQ Asia-Pacific Regional Conference. International Association on Water Quality. Chinese Taiwan Committee, Taipei, Taiwan.

- 11.Hashimoto, A., S. Kunikane, and T. Hirata. 2002. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts in the drinking water supply in Japan. Water Res. 36:519-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirata, T., D. Chikuma, A. Shimura, A. Hashimoto, N. Motoyama, K. Takahashi, T. Moniwa, M. Kaneko, S. Saito, and S. Maede. 2000. Effects of ozonation and chlorination on viability and infectivity of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. Water Sci. Technol. 41:39-46. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirata, T., A. Shimura, S. Morita, M. Suzuki, N. Motoyama, H. Hoshikawa, T. Moniwa, and M. Kanako. 2001. The effect of temperature on the efficacy of ozonation for inactivating Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. Water Sci. Technol. 43:163-166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho, C. F. H., P. Pitt, D. Mamais, C. Chiu, and D. Jolis. 1998. Evaluation of UV disinfection systems for large-scale secondary effluent. Water Environ. Res. 70:1142-1150. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurley, M., and M. E. Roscoe. 1983. Automated statistical analysis of microbial enumeration by dilution series. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 55:159-164. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joret, J. C., J. Aron, B. Langlais, and D. Perrine. 1997. Inactivation of Cryptosporidium sp. oocysts by ozone evaluated by animal infectivity, p. 739-744. In Proceedings of the 13th Ozone World Congress. International Ozone Association, Kyoto, Japan.

- 17.Korich, D. G., J. R. Mead, M. S. Madore, N. A. Sinclair, and C. R. Sterling. 1990. Effects of ozone, chlorine dioxide, chlorine, and monochloramine on Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst viability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1423-1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer, M. H., B. L. Herwald, G. F. Craun, R. L. Calderon, and D. D. Juranek. 1996. Waterborne disease: 1993 and 1994. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 88:66-80. [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeChevallier, M. W., and W. D. Norton. 1995. Giardia and Cryptosporidium in raw and finished water. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 87:54-78. [Google Scholar]

- 20.LeChevallier, M. W., W. D. Norton, and R. G. Lee. 1991. Occurrence of Giardia and Cryptosporidium spp. in surface water supplies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:2610-2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linden, K. G., G. A. Shin, and M. D. Sobsey. 2000. Comparative effectiveness of UV wavelength for the inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum in water, p. 99-100. In Proceedings of the 1st World Water Congress of the International Water Association. International Water Association, Paris, France. [PubMed]

- 22.Lindenauer, K. G., and J. Darby. 1994. Ultraviolet disinfection of wastewater: effect of dose on subsequent photoreactivation. Water Res. 28:805-817. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorenzo, L. M., M. M. E. Ares, M. M. Villacorta, and O. D. Duran. 1993. Effects of ultraviolet disinfection of drinking water on the viability of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. J. Parasitol. 79:67-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oguma, K., H. Katayama, H. Mitani, S. Morita, T. Hirata, and S. Ohgaki. 2001. Determination of pyrimidine dimers in Escherichia coli and Cryptosporidium parvum during ultraviolet light inactivation and photoreactivation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4630-4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ongerth, J. E., and H. H. Stibbs. 1987. Identification of Cryptosporidium oocysts in river water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:672-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oppenheimer, J. A., J. G. Jacangelo, J. M. Laine, and J. E. Hoagland. 1997. Testing the equivalency of ultraviolet light and chlorine for disinfection of wastewater to reclamation standards. Water Environ. Res. 69:14-24. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ransome, M. E., T. N. Whitmore, and E. G. Carrington. 1993. Effects of disinfectants on the viability of Cryptosporidium parvum. Water Suppl. 11:75-89. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rennecker, J. L., B. J. Marinas, J. H. Owens, and E. W. Rice. 1999. Inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts with ozone. Water Res. 33:2481-2488. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rose, J. B., C. P. Gerba, and W. Jakubowski. 1991. Survey of potable water supplies for Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Environ. Sci. Technol. 25:1393-1400. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin, G. A., K. Linden, T. Handzel, and M. D. Sobsey. 1999. Low pressure UV inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum based on cell culture infectivity, p. ST-7.4.1-ST7.4.8. In Proceedings of the American Water Works Association Water Quality Technology Conference. American Water Works Association, Tampa, Fla.

- 31.Sutherland, B. M., and A. G. Shih. 1983. Quantitation of pyrimidine dimer contents of nonradioactive deoxyribonucleic acid by electrophoresis in alkaline agarose gels. Biochemistry 22:745-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veatch, W., and S. Okada. 1969. Radiation-induced breaks of DNA in cultured mammalian cells. Biophys. J. 9:330-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Water Environment Federation. 1996. Wastewater disinfection, p. 227-291. Manual of practice FD-10. Water Environment Federation, Alexandria, Va.

- 34.Water Environment Federation. 1996. Wastewater disinfection, p. 244-248. Manual of practice FD-10. Water Environment Federation, Alexandria, Va.

- 35.Woodmansee, D. B. 1987. Studies of in vitro excystation of Cryptosporidium parvum from calves. J. Protozool. 34:398-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]