Abstract

Mutants of Staphylococcus aureus strain COL resistant to a household pine oil cleaner (POC) were isolated on laboratory media containing POC. S. aureus mutants expressing the POC resistance (POCr) phenotype also demonstrate reduced susceptibility to the cell wall-active antibiotics vancomycin and oxacillin. The POCr phenotype is reliant on the S. aureus alternative transcription factor SigB, since inactivation of sigB abolished expression of elevated POC resistance and the reductions in vancomycin and oxacillin susceptibilities. The isolation of suppressor mutants of COLsigB::kan, which maintain the sigB::kan allele, indicates that the POCr phenotype can also be expressed to a lesser degree via a sigB-independent mechanism. These results bolster a growing body of reports suggesting that common disinfectants can select for bacteria with reduced susceptibilities to antibiotics. A series of in vitro-selected glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus (GISA) isolates also expressed reductions in POC susceptibility compared to parent strains. Viewed collectively, our evidence suggests that mutations leading to the POCr phenotype may also be involved with the mechanism that leads to the GISA phenotype.

The cost of infections caused by antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the United States has recently been estimated to be between 24 and 36 billion dollars per year (19). Infections with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) are also associated with higher mortality rates than disease caused by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (27). The glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin remains the antibiotic of choice for treatment of serious MRSA infections; however, MRSA isolates expressing intermediate levels of vancomycin resistance, i.e., glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus (GISA), have now been isolated from patients (for a review, see references 9 and 12). SigB, an alternative transcription factor of S. aureus, is involved with general stress resistance (5) and virulence factor production (2, 6, 15, 24). Inactivation of sigB in various strains of MRSA and GISA can also lead to reductions in resistance to oxacillin and vancomycin (30a, 32).

In the laboratory, various disinfectants and antiseptics have been shown to select for bacteria with increased antibiotic resistance (for a review, see reference 17), including MRSA with elevated resistance to antibiotics (1). It is now feared that the continued use of disinfectants in the household will promote the evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacteria (16). Cleaning and disinfecting solutions consisting of pine oil, surfactants, and alcohol are commonly purchased and used in households around the world. It has been previously shown in the laboratory that a pine oil-containing cleaning product can select for Escherichia coli mutants with reduced susceptibilities to multiple antibiotics (18).

In an effort to further understand potential links between disinfectant resistance and antibiotic resistance, we have now isolated MRSA mutants expressing elevated resistance to a common household pine oil cleaner (POC). Relationships between POC, oxacillin, and vancomycin resistance and sigB were also investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, antibiotics, and chemicals.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. COL is a homogenous MRSA strain (28) that has been chosen for genomic sequencing (see http://www.tigr.org/tdb/mdb/mdbinprogress.html). Bacterial strains were maintained on Luria broth agar (LBA) (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), while isolates carrying the sigB::kan insertion were maintained on LBA supplemented with 100 mg of kanamycin/liter. Unless otherwise noted, chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo. The POC (Pine-Sol) was obtained from a local supermarket. Vancomycin, kanamycin, and oxacillin (Bristol Laboratories, Syracuse, N.Y.) were prepared in water, filter sterilized, and stored at −20°C.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain(s) | Relevant backgrounda | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| COL | MRSA | 28 |

| COLsigB::kan | COL, sigB::kan | 30a |

| CP170 to CP179 | COL, POCr | This study |

| CP191 to CP196 | CP170sigB::kan | This study |

| CP197 to CP199 | CP171sigB::kan | This study |

| CP182 and CP183 | COLsigB::kan, POCr | This study |

| BB568 | MRSA, COL | 10 |

| BB568V15 | BB568 GISA | 21 |

| BB255 | NCTC 8325 | 10 |

| BB255V3 | BB255 GISA | 21 |

| BB270 | MRSA, BB255 | 10 |

| BB270V15 | BB270 GISA | 21 |

| BB399 | MRSA | 10 |

| BB399V12 | BB399 GISA | 21 |

| SH108 | atl mutant | 8 |

| SH108V5 | SH108 GISA | 21 |

Abbreviations: MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; POCr, pine oil cleaner resistant; GISA, glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus.

Selection of S. aureus mutants expressing the POC resistance (POCr) phenotype.

Initially, 100-μl aliquots of overnight LB cultures of COL and COLsigB::kan were spread on LBA containing 1.5 and 0.4% POC (vol/vol), respectively, and incubated at 37°C until surviving POCr mutant CFU appeared (48 to 72 h). Individual CFU were then passaged three times in LB before being tested for drug resistance levels. Individual POCr CFU of both S. aureus strain COL and COLsigB::kan surviving on LBA plates prepared with 1.5 and 0.4% POC (vol/vol), respectively, arose at a frequency of 10−8.

Determination of POC, vancomycin, and oxacillin susceptibilities.

Resistance levels to POC, vancomycin, and oxacillin were determined by the gradient plate method using LBA, as described previously (23). POC (1% [vol/vol]) was added to the upper LBA layer (0-to-1% [vol/vol] gradient) for all strains examined, except for BB270 and SH108 and their respective GISA mutants, where 0.4% (vol/vol) POC was incorporated into the upper LBA layer (0-to-0.4% [vol/vol] gradient). Vancomycin (1 mg/liter final concentration) or oxacillin (500 mg/liter final concentration) was added to the upper LBA layer as required, creating 0-to-1-mg/liter and 0-to-500-mg/liter gradients, respectively. Gradient plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h, and resistance levels were expressed as the distance grown in millimeters on the gradient by each strain investigated (Table 2). Vancomycin resistance population analyses were performed as previously described, using LBA containing increasing concentrations of vancomycin (20, 23). Essentially, S. aureus isolates were grown overnight in 3 ml of LB (37°C, 200 rpm) and then serially diluted in fresh LB. Ten-microliter aliquots of the dilutions were then pipetted onto the surface of LBA plates containing increasing concentrations of vancomycin. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and CFU were scored.

TABLE 2.

POC, vancomycin, and oxacillin gradient plate resultsa

| Strain | Parent | Kmr | Growth (mm) on gradientb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 → 1% (vol/vol)c POC | 0 → 1 mg/liter Van | 0 → 500 mg/liter Oxa | |||

| COL | − | 23 | 34 | 42 | |

| COLsigB::kan | COL | + | 0↓ | 27 ↓ | 5 ↓ |

| CP170 | COL | − | 55 ↑ | 44 ↑ | 42 − |

| CP171 | COL | − | 59 ↑ | 40 ↑ | 60 ↑ |

| CP172 | COL | − | 63 ↑ | 59 ↑ | 63 ↑ |

| CP173 | COL | − | 83 ↑ | 39 ↑ | 65 ↑ |

| CP174 | COL | − | 53 ↑ | 34 − | 63 ↑ |

| CP175 | COL | − | >90 ↑ | 37 ↑ | 71 ↑ |

| CP176 | COL | − | >90 ↑ | 40 ↑ | 73 ↑ |

| CP177 | COL | − | >90 ↑ | 42 ↑ | 73 ↑ |

| CP178 | COL | − | >90 ↑ | 57 ↑ | 73 ↑ |

| CP179 | COL | − | >90 ↑ | 42 ↑ | 74 ↑ |

| CP191sigB::kan | CP170 | + | 0 ↓ | 29 ↓ | 40 ↓ |

| CP192sigB::kan | CP170 | + | 0 ↓ | 29 ↓ | 27 ↓ |

| CP193sigB::kan | CP170 | + | 0 ↓ | 29 ↓ | 24 ↓ |

| CP194sigB::kan | CP170 | + | 0 ↓ | 29 ↓ | 19 ↓ |

| CP195sigB::kan | CP170 | + | 5 ↓ | 34 ↓ | 30 ↓ |

| CP196sigB::kan | CP170 | + | 0 ↓ | 34 ↓ | 27 ↓ |

| CP197sigB::kan | CP171 | + | 0 ↓ | 25 ↓ | 0 ↓ |

| CP198sigB::kan | CP171 | + | 0 ↓ | 19 ↓ | 0 ↓ |

| CP199sigB::kan | CP171 | + | 0 ↓ | 20 ↓ | 0 ↓ |

| CP182 | COLsigB::kan | + | 35 ↑ | 32 ↑ | 14 ↑ |

| CP183 | COLsigB::kan | + | 33 ↑ | 27 − | 14 ↑ |

| BB568 | ND | 7 | ND | ND | |

| BB568V15 | BB568 | ND | 25 ↑ | ND | ND |

| BB255 | ND | 14 | ND | ND | |

| BB255V3 | BB255 | ND | 24 ↑ | ND | ND |

| BB270c | ND | 17 | ND | ND | |

| BB270V15c | BB270 | ND | 25 ↑ | ND | ND |

| BB399 | ND | 7 | ND | ND | |

| BB399V12 | BB399 | ND | 28 ↑ | ND | ND |

| SH108c | ND | 22 | ND | ND | |

| SH108V5c | SH108 | ND | 31 ↑ | ND | ND |

Abbreviations: Kmr, kanamycin resistant; POC, pine oil cleaner; Van, vancomycin; Oxa, oxacillin; ND, not determined.

Numbers represent millimeters of growth on 90-mm drug gradient plates. Arrows indicate increases (↑) or decreases (↓) in resistance levels expressed by mutant strains compared to relevant parent strains. The “−” indicates no difference in distances grown by mutant and parent strain on drug gradient plates.

A gradient of 0 to 0.4% POC was used for BB270, BB270V15, SH108, and SH108V5.

Transduction of sigB::kan and isolation of chromosomal DNA.

Phage 80α lysates of COLsigB::kan were prepared and used to transduce the sigB::kan allele into COL mutants expressing the POCr phenotype. Transductants were selected on LBA supplemented with 100 mg of kanamycin/liter. S. aureus chromosomal DNA for PCR analysis was isolated from lysostaphin-treated cells using DNAzol (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, Ohio) as recommended by the manufacturer. Chromosomal DNA was precipitated with ethanol, spooled onto a glass rod, and washed two times with 100% ethanol. The spooled washed DNA was then allowed to air dry and resuspended in 50 mM Tris-Cl-EDTA (pH 7.0) buffer (30).

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of POCr COL mutants.

POC resistance levels were determined initially for POCr mutants (strains CP170 to CP179) of COL surviving on 1.5% (vol/vol) POC. Distances grown by the POCr mutants CP170 to CP179 on POC gradients were increased (2.4- to >3.9-fold) relative to the distance grown by the parent strain, COL (Table 2).

Importance of sigB in the POC resistance mechanism.

Since sigB is important in the general stress response of S. aureus (5), we determined the effect of sigB inactivation on POC resistance expression. Initially, the POC resistance levels of parent strain COL and that of the isogenic sigB mutant COLsigB::kan (Table 1) were analyzed. COLsigB::kan did not grow on the POC gradient examined, while the parent strain COL grew to a distance of 23 mm (Table 2). Transduction of the sigB::kan allele into POCr mutants CP170 and CP171 resulted in kanamycin-resistant strains CP191 to CP196 and CP197 to CP199, respectively (Table 1). Chromosomal preparations of parent strains (COL, CP170, and CP171), COLsigB::kan (30a), and putative sigB::kan transductants (CP191 and CP197) were subjected to PCR using an internal sigB forward primer (5′-CCTTTGAACGGAAGTTTGAAGC-3′) and a reverse sigB primer (5′-TGACACACCATCATTTCTA-3′) (annealing temperature, 55°C) which binds 272 bp downstream of the sigB stop codon. In strains COL, CP170, and CP171, a 0.86-kb sigB PCR product was generated as expected. In the putative sigB::kan transductants (CP191 and CP197) and COLsigB::kan, a 0.86-kb sigB amplicon was replaced by a 1.7-kb sigB::kan PCR product. The 1.7-kb amplicon indicates a sigB allele in which a 664-bp EcoRV internal sigB fragment has been deleted and replaced with a 1.5-kb kanamycin resistance cassette. With the exception of CP195, all CP170 and CP171 sigB::kan transductants did not grow on the POC gradient examined (Table 2). While transductant CP195 did grow on the POC gradient investigated, it still demonstrated an 11-fold reduction in POC resistance compared to parent strain CP170. This evidence indicates that the loss of sigB in a wild-type and POCr background leads to strains that are highly susceptible to the action of POC.

Two POCr suppressor mutants of COLsigB::kan were successfully isolated from LBA plates containing 0.4% (vol/vol) POC. Both mutants CP182 and CP183 retained resistance to kanamycin, and CP182 at least also retained the inactivated sigB::kan allele as determined by PCR analysis (see above) and the presence of a 1.7-kb amplicon. Both CP182 and CP183 expressed a 33- to >35-fold increase in POC resistance compared to parent strain COLsigB::kan. The POC resistance levels expressed by CP182 and CP183 were lower than that of sigB+ POCr mutants CP170 to CP179 (Table 2), but they were higher than that of the original strain COL.

Vancomycin and oxacillin susceptibilities in POCr mutants and isogenic sigB::kan transductants.

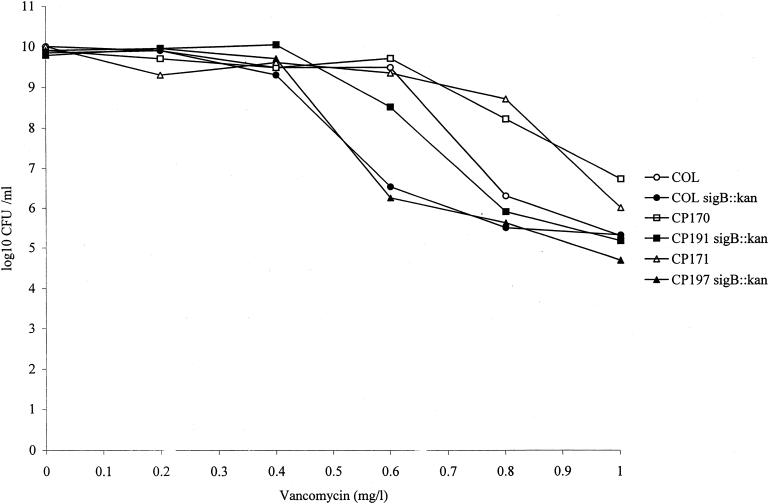

Since sigB inactivation had such a dramatic effect on POC resistance and sigB is also associated with the expression of vancomycin and oxacillin resistance (32; Singh et al., submitted), vancomycin and oxacillin resistance levels were analyzed in the POCr strains and their isogenic sigB::kan mutants. The distances grown by the POCr COL mutants CP170 to CP173 and CP175 to CP179 on a vancomycin gradient were increased (1.1- to 1.7-fold) relative to the distance grown by parent strain COL (Table 2). In contrast, POCr isolate CP174 grew to the same distance as that grown by parent strain COL on a vancomycin gradient (Table 2). Vancomycin resistance population analyses revealed that on plates containing 0.8 and 1.0 mg of vancomycin/liter, the number of individual CP170 and CP171 CFU surviving was increased by 1.9 and 2.4, and 1.4 and 0.7 log units, respectively, compared to the number of COL CFU surviving on these plates (Fig. 1). Except for the POCr mutant CP170, the distances grown on an oxacillin gradient by all POCr isolates were increased (1.4- to 1.8-fold) relative to the distance grown by parent strain COL (Table 2). Besides demonstrating reduced POC resistance, COLsigB::kan, CP191 to CP196, and CP197 to CP199 also demonstrated elevated vancomycin and oxacillin susceptibilities compared to their respective sigB+ parent strains COL, CP170, and CP171 (Table 2). CP171 sigB::kan transductants (CP197, CP198, and CP199) did not grow at all on the oxacillin gradient examined (Table 2). Vancomycin resistance population analyses also revealed lower numbers of COLsigB::kan, CP191 (CP170sigB::kan), and CP197 (CP171sigB::kan) CFU surviving on increasing vancomycin concentrations compared to their respective parent strains (Fig. 1). At 1.0 mg of vancomycin/liter, the number of CP191 and CP197 CFU surviving was reduced by 1.5 and 1.3 log units, respectively, compared to the number of POCr parent strain CP170 and CP171 CFU surviving on the same vancomycin concentration (Fig. 1). Oxacillin susceptibility was also reduced 2.8-fold in both POCr sigB::kan suppressor mutants CP182 and CP183 compared to parent strain COLsigB::kan, but only CP182 demonstrated a reduced vancomycin susceptibility (1.2-fold) compared to the parent COLsigB::kan.

FIG. 1.

Vancomycin resistance population analysis for strains COL, COLsigB::kan, CP170, CP191sigB::kan, CP171, and CP197sigB::kan.

Comparison of POC resistance levels of in vitro-selected GISA strains and their respective parent strains.

Our results demonstrate a connection between POC resistance, sigB, and reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Therefore, we investigated if in vitro-selected GISA strains representing different genetic lineages (Table 1) also expressed altered POC resistance levels compared to their respective parent strains. The distances grown on POC gradients by all GISA isolates examined (BB568V15, BB255V3, BB399V12, BB270V15, and SH108V5) were increased relative to the distances grown by each of the respective parent strains (Table 2). This indicates that mutations selected for in vitro that result in the GISA phenotype can also lead to elevated POC resistance.

DISCUSSION

POCs are used in the household for cleaning and disinfection of most surfaces and clothing. The active ingredient of POCs is pine oil, which significantly adds to the ability of POCs to deodorize and disinfect areas and items within a household. The predominant component of pine oil is alpha-terpineol (7), which along with other terpenes has antimicrobial activity (4, 11, 14, 25). We have shown here that mutants of an MRSA strain demonstrating elevated resistance to POC can be isolated on laboratory media containing 1.5% POC (vol/vol) in a single step. We have also determined that the POCr phenotype leads to reduced oxacillin and vancomycin susceptibility. In vitro-selected S. aureus mutants demonstrating elevated resistance to the common household disinfectant triclosan also can express slightly reduced susceptibilities to vancomycin (see Table 3 in reference 31). These results add to a growing body of reports suggesting that common disinfectants can select for bacteria with reduced susceptibilities to antibiotics (16).

The emergence of GISA has become a serious public health threat (9, 12). Some strains of S. aureus expressing reduced vancomycin susceptibility have been reported to have vancomycin MICs as low as 1.0 mg/liter (3, 9, 13). It is not until these strains are screened on media containing vancomycin that their true GISA identity is discovered (for a review, see reference 9). Since low-level vancomycin resistance is relevant, it will be important to determine if POCr mutants that survive on subclinical vancomycin concentrations also mutate with greater ease to obtain a GISA phenotype.

All in vitro-selected GISA strains examined in our study had increased resistance to POC, even though these isolates had no prior exposure to POC. The increase in vancomycin resistance expressed by the in vitro-selected GISA we have analyzed has been attributed to alterations in cell wall structure and physiology (21). Since POCs are made with pine oil, surfactants, and alcohol, these mixtures probably target the membrane of susceptible microorganisms. Therefore, it is probable that the mutations leading to the POCr phenotype, similar to mutations leading to the GISA phenotype, also alter the cell wall structure of S. aureus.

POC resistance is reliant on sigB, since inactivation of this alternative transcription factor led to dramatic reductions in POC resistance and increases in vancomycin and oxacillin susceptibilities. However, the isolation of POCr suppressor mutants of COLsigB::kan (CP182 and CP183), which retain the sigB::kan allele, suggests that a sigB-independent pathway can also provide the cell with the means to express the POCr phenotype. The levels of POC resistance and reductions in vancomycin (when expressed) and oxacillin susceptibilities, however, were lower for POCr suppressor mutants (CP182 and CP183) compared to sigB+ POCr mutants CP170 to CP179. This indicates that while a suppressor mutation(s) can overcome sigB inactivation to allow for the POCr phenotype, strains with intact sigB express greater POCr-related resistance levels. The agr locus is intimately involved with the production of S. aureus virulence factors (26). Recently, a report appeared demonstrating that deletion of the agr locus leads to reduced vancomycin susceptibility in S. aureus (29). Piriz-Duran et al. previously demonstrated that the inactivation of agr also leads to reduced oxacillin resistance in S. aureus (22). In addition, the agr operon is under the control of SigB (2). Therefore, it is possible that mutations leading to the sigB-dependent POCr phenotype involve the agr locus.

Acknowledgments

C.T.D.P. is the recipient of an Australian Postgraduate Scholarship through Curtin University of Technology. J.E.G. acknowledges Midwestern University intramural funds and A.D. Russell of Cardiff University (United Kingdom) for personal communications. V.K.S. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association, Midwest Affiliate. Work in the B.J.W. and R.K.J. laboratories was supported by NIH grants AI43970, AI43027, and AI049964.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akimitsu, N., H. Hamamoto, R. Inoue, M. Shoji, A. Akamine, K. Takemori, N. Hamasaki, and K. Sekimizu. 1999. Increase in resistance or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to beta-lactams caused by mutations conferring resistance to benzalkonium chloride, a disinfectant widely used in hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:3042-3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bischoff, M., J. M. Entenza, and P. Giachino. 2001. Influence of a functional sigB operon on the global regulators sar and agr in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:5171-5179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle-Vavra, S., R. B. Carey, and R. S. Daum. 2001. Development of vancomycin and lysostaphin resistance in a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:617-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carson, C. F., and T. V. Riley. 1995. Antimicrobial activity of the major components of the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 78:264-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan, P. F., S. J. Foster, E. Ingham, and M. O. Clements. 1998. The Staphylococcus aureus alternative sigma factor σB controls the environmental stress response but not starvation survival or pathogenicity in a mouse abscess model. J. Bacteriol. 180:6082-6089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung, A. L., Y. T. Chien, and A. S. Bayer. 1999. Hyperproduction of alpha-hemolysin in a sigB mutant is associated with elevated SarA expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 67:1331-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claus, E. P., V. P. Tyler, and L. R. Brady. 1970. Pharmacognosy. Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 8.Foster, S. J. 1995. Molecular characterization and functional analysis of the major autolysin of Staphylococcus aureus 8325/4. J. Bacteriol. 177:5723-5725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fridkin, S. K. 2001. Vancomycin-intermediate and -resistant Staphylococcus aureus: what the infectious disease specialist needs to know. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:108-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gustafson, J. E., B. Berger-Bachi, A. Strassle, and B. J. Wilkinson. 1992. Autolysis of methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:566-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustafson, J. E., S. D. Cox, Y. C. Liew, S. G. Wyllie, and J. R. Warmington. 2001. The bacterial multiple antibiotic resistant (Mar) phenotype leads to increased tolerance to tea tree oil. Pathology 33:211-215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiramatsu, K. 2001. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a new model of antibiotic resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 1:147-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiramatsu, K., N. Aritaka, H. Hanaki, S. Kawasaki, Y. Hosoda, S. Hori, Y. Fukuchi, and I. Kobayashi. 1997. Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet 350:1670-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, J. M., M. R. Marshall, and C. Wei. 1995. Antibacterial activity of some essential oil components against five foodborne pathogens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 43:2839-2845. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kullik, I., P. Giachino, and T. Fuchs. 1998. Deletion of the alternative sigma factor σB in Staphylococcus aureus reveals its function as a global regulator of virulence genes. J. Bacteriol. 180:4814-4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy, S. B. 2001. Antibacterial household products: cause for concern. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:512-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonnell, G., and A. D. Russell. 1999. Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:147-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moken, M. C., L. M. McMurry, and S. B. Levy. 1997. Selection of multiple-antibiotic-resistant (mar) mutants of Escherichia coli by using the disinfectant pine oil: roles of the mar and acrAB loci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2770-2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palumbi, S. R. 2001. Humans as the world's greatest evolutionary force. Science 293:1786-1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfeltz, R. F., J. L. Schmidt, and B. J. Wilkinson. 2001. A microdilution plating method for population analysis of antibiotic-resistant staphylococci. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:289-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeltz, R. F., V. K. Singh, J. L. Schmidt, M. A. Batten, C. S. Baranyk, M. J. Nadakavukaren, R. K. Jayaswal, and B. J. Wilkinson. 2000. Characterization of passage-selected vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains of diverse parental backgrounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:294-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piriz-Duran, S., F. H. Kayser, and B. Berger-Bächi. 1996. Impact of sar and agr on methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 141:255-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price, C. T., F. G. O'Brien, B. P. Shelton, J. R. Warmington, W. B. Grubb, and J. E. Gustafson. 1999. Effects of salicylate and related compounds on fusidic acid MICs in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rachid, S., K. Ohlsen, U. Wallner, J. Hacker, M. Hecker, and W. Ziebuhr. 2000. Alternative transcription factor σB is involved in regulation of biofilm expression in a Staphylococcus aureus mucosal isolate. J. Bacteriol. 182:6824-6826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raman, A., U. Weir, and S. F. Bloomfield. 1995. Antimicrobial effects of tea tree oil and its major components on Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Propionibacterium acnes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 21:242-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Recsei, P., B. Kreiswirth, M. O'Reilly, P. Schlievert, A. Gruss, and R. P. Novick. 1986. Regulation of exoprotein gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus by agar. Mol. Gen. Genet. 202:58-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin, R. J., C. A. Harrington, A. Poon, K. Dietrich, J. A. Greene, and A. Moiduddin. 1999. The economic impact of Staphylococcus aureus infection in New York City hospitals. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabath, L. D., S. J. Wallace, K. Byers, and I. Toftegaard. 1974. Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to penicillins and cephalosporins: reversal of intrinsic resistance with some chelating agents. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 236:435-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakoulas, G., G. M. Eliopoulos, R. C. Moellering, Jr., C. Wennersten, L. Venkataraman, R. P. Novick, and H. S. Gold. 2002. Accessory gene regulator (agr) locus in geographically diverse Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1492-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 30a.Singh, V. K., J. L. Schmidt, R. K. Jayaswal, and B. J. Wilkinson. Impact of sigB mutation on Staphylococcus aureus oxacillin and vancomycin resistance varies with parental background and method of assessment. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Suller, M. T., and A. D. Russell. 2000. Triclosan and antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu, S., H. de Lencastre, and A. Tomasz. 1996. Sigma-B, a putative operon encoding alternate sigma factor of Staphylococcus aureus RNA polymerase: molecular cloning and DNA sequencing. J. Bacteriol. 178:6036-6042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]