In a 1747 letter to his parents, Benjamin Franklin noted

‘I apprehend I am to busy in prescribing, and meddling in the Dr's sphere, when any of you complain of ails in your letters: but as I always employ a physician myself when any disorder arises in my family and submit implicitly to his orders in every thing, so I hope you consider my advice, when I give any, only as a mark of my good will, and put no more of it in practice that happens to agree with what your Dr. directs.’1

After giving this assurance that he did not mean to play the physician, Franklin continued with advice about remedies for bladder stone and gravel. In fact, throughout his life he dispensed such advice and wrote knowledgeably on a number of health-related issues.

Franklin played many roles during his long life: printer and publisher, civic activist, revolutionary and statesman, scientist and philosopher, diplomat, and sage. Given the significance of his political and civic activities and his experimentation with electricity, it is little wonder that Franklin's medical interests have attracted less attention. Nonetheless, despite his lack of formal training, medicine was prominent among Franklin's interests. His writings ranged over a number of topics, from treatment of the common cold to promotion of exercise and a moderate diet. With his connections to prominent physicians on both sides of the Atlantic and with his published works widely read, Franklin's thoughts on health and medicine found a broad contemporary audience. He was also a medical activist and inventor, championing smallpox inoculation, taking a leading role in founding Pennsylvania Hospital (the first such institution in the British North American colonies), and inventing devices like bifocal glasses.

Born in Boston in 1706, Benjamin Franklin (Figure 1) was the youngest son of 17 children. He came to Philadelphia in 1723, after leaving an apprenticeship with his brother, a printer. By the 1730s, Franklin was owner of his own printing house, publishing a popular newspaper and almanac, and a civic activist. He retired from printing in 1748 to pursue other interests and later gained international fame for his experiments with electricity.

Figure 1.

Portrait-bust of Benjamin Franklin in profile. Anonymous French artist, 1777. From the Private Collection of Bruce McKittrick

Franklin spent the latter portion of his life in politics and diplomacy. He served in the Pennsylvania Assembly and spent 15 years in London as a colonial agent. He was also a member of the legislative bodies crucial to the founding of the United States, serving as a delegate to the Continental Congress and, later, the oldest participant in the Constitutional Convention. Franklin signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and was sent to France as the first diplomat from the USA.

Such diverse interests and activities were not unusual for the time. Many educated men were active or interested in politics, civic or social improvement, and scientific exploration. These pursuits rose out of a social consciousness born of the Enlightenment. This movement valued reason and observation as the means to knowledge and improved social organization. An Enlightenment temperament, such as that shown by Franklin, had a high regard for rationality, valued self-discipline and social consciousness, and desired to generate progress by increase of learning.

In his roles as scientist and purveyor of information, Franklin was an active citizen in the eighteenth-century medical world. His contemporaries sought healthcare and medical advice from a wide variety of sources and most medical care was provided in the home from family members or—for the wealthy—servants. Sources of counsel about health, disease and medicine included popular health manuals, almanacs, newspapers and cookbooks. The adages and poetry in Poor Richard's Almanac, the entire contents of which were authored by Franklin, served to instruct the masses at the same time they entertained.

Through his almanac and other writings, Benjamin Franklin exerted his greatest influence on the medical sphere. With numerous well-informed correspondents—including physicians and scientists on two continents—and, as a skilled writer, he was capable of writing letters, articles, collections of sayings and other works filled with medical commentary. These covered a wide range of subjects including electrical treatments for paralysis.

Medical uses of electricity were much discussed during Franklin's lifetime. It was known, from early in the eighteenth century, that an electrical shock could cause involuntarily twitching and contraction of muscles. Many people thus hoped that ‘electrical fire’ would provide a cure for paralysis. They believed that sending a charge through the affected limbs might increase blood flow, regenerate muscle and restore movement or physical control.

Franklin was doubtful about the usefulness of electrical treatment for palsy and paralysis and never promoted himself as an electrical therapist. Nonetheless, because of his reputation as an electrical innovator, he was from time to time contacted by people seeking electrical therapy. Using an electrostatic generator (in which electrical charge was created by rubbing material against a mounted glass ball or cylinder turned by a crank) and a Leyden jar (which stored the electrical energy), Franklin obliged those patients who came to him desiring electrical therapies. He described these treatments in a letter to Sir John Pringle, dated 21 December 1757.

‘Some years since...a number of paralytics were brought to me from different parts of Pennsylvania and the neighboring provinces, to be electris'd, which I did for them, at their request. My method was, to place the patient first in a chair on an electric stool, and draw a number of large strong sparks from all parts of the affected limb or side. Then I fully charg'd two 6 gallon glass jars, each of which had about 3 square feet of surface coated and I sent the united shock of these thro’ the affected limb or limbs, repeating the stroke commonly three times each day.

The first thing observed was an immediate greater sensible warmth in the lame limbs that receiv'd the stroke than in the others... The limbs too were found more capable of voluntary motion and seem'd to receive strength... These appearances gave great spirits to the patients, and made them hope a perfect cure; but I do not remember that I ever saw any amendment after the fifth day: Which the patients perceiving, and finding the shocks pretty severe, they became discourag'd, went home and in a short time relapsed; so that I never knew any advantage from electricity in palsies that was permanent.'2

Although Franklin's patients found no permanent cure for their paralysis, he continued to receive requests for aid—one even from Pringle himself, who requested Franklin's presence in 1767 at the treatments administered to the daughter of a nobleman.3

Franklin also concerned himself with medical problems more removed from his own scientific expertise. He wrote about lead poisoning on several occasions, in particular about a disease known as the dry-gripes (or dry-bellyache) that had plagued Europe and the colonies for years. Franklin had not yet left Boston when, in 1723 the Massachusetts colonial legislature passed a bill outlawing the use of lead in the coils and heads of stills. Observance of this law led to vastly decreased incidence of the dry-gripes, as the population drank less and less lead-contaminated rum.

In a letter to his friend, Philadelphia physician Cadwalader Evans, Franklin wrote that he was certain that the symptoms known as dry-bellyache were always the result of lead exposure, whether in food or drink or from exposure through trades that used lead.4 In his correspondence with Dr George Baker, Franklin advanced this idea and thus helped Baker discover the aetiology of the Devonshire Colic, a condition the symptoms of which included weakened muscles, loss of weight and pallor. It was widespread in Baker's native Devonshire; Baker suspected lead-contaminated cider was the cause, and his discussions with Franklin helped confirm his hypothesis. Baker eventually found that millwheels that were used to crush the apples were bound together with poured molten lead. He credited Franklin with his assistance in this discovery on several occasions.

Franklin's scientific activities and medical acumen was respected on both sides of the Atlantic by physicians, scientists and, in one case, royalty. During Franklin's time in Paris, he participated in the discrediting of the medical cult surrounding Mesmerism. Franz Anton Mesmer arrived in Paris in 1778, promoting his new principle of healing known as animal magnetism. His treatments attracted many followers, but also the scepticism of French physicians, who regarded Mesmer as a fraud. In March 1784, Louis XVI appointed a commission to investigate Mesmer's claims. Four physicians and five eminent scientists were on the commission, including Franklin, who was chosen to preside over their investigation.

The Commission observed one of Mesmer's disciples, a Dr D'Eslon, at Franklin's home in Passy, outside Paris. D'Eslon attempted to magnetize several patients chosen by the Commission, as well as members of Franklin's own household, and the subjects reported feeling no change. In the Commission's report, written by Franklin, Mesmer was declared a fraud, as no reasonable proof of animal magnetism could be determined. Franklin felt that any cures made were a product of imagination, and the report he authored led to Mesmer's disgrace.

Throughout his lifetime, Franklin produced many lighter writings on health related topics as well. His advice in Poor Richard's Almanac includes Franklin's most famous advice on health, including such maxims as:

Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise

Be not sick too late, nor well too soon

Time is an herb that cures all diseases

Eat to live and not live to eat.

Franklin promoted a moderate diet, exercise, and self-control in all things, and sometimes even followed his own advice. In his youth, Franklin was influenced to try vegetarianism after reading Thomas Tryon's Way to Health and Happiness; he later returned to eating meat. He exercised frequently, favouring swimming and endorsing it not only as good exercise but also as a method to open pores, hydrate the body and maintain cleanliness. In his old age, Franklin continued to exercise, lifting and swinging weights when his health no longer allowed him to swim or walk.

Many of Franklin's medical writings showed the same spirit of public activism that characterized his civic and national projects. He repeatedly used his skills with pen and press in support of innovations that could make a difference in the public health. Most significant, perhaps, was his lifelong endorsement of smallpox inoculation.

Inoculation spread rapidly in North America and Europe after its introduction into western medicine in the 1720s. The practice involved exposing healthy individuals to the disease by abrading the skin and introducing a small amount of morbid matter. Typically the patient would contract a similarly mild instance of the disease and, once recovered, would have permanent immunity. Cases contracted the natural way would often leave victims disfigured and had a significant mortality rate.

Franklin wrote articles promoting inoculation and its safety as early as 1731. His support of inoculation grew after the heartbreaking loss of his 6-year-old son, Francis Folger Franklin, to smallpox in 1736. Franklin had planned to inoculate the boy at the time of an outbreak, but was unable to do so because the child was in a weakened state from another illness. Critics of inoculation suggested that Franklin's son had been a victim of the procedure, and Franklin was forced to publish an article in his paper, The Pennsylvania Gazette, insisting that his son had contracted a natural case of the disease.5

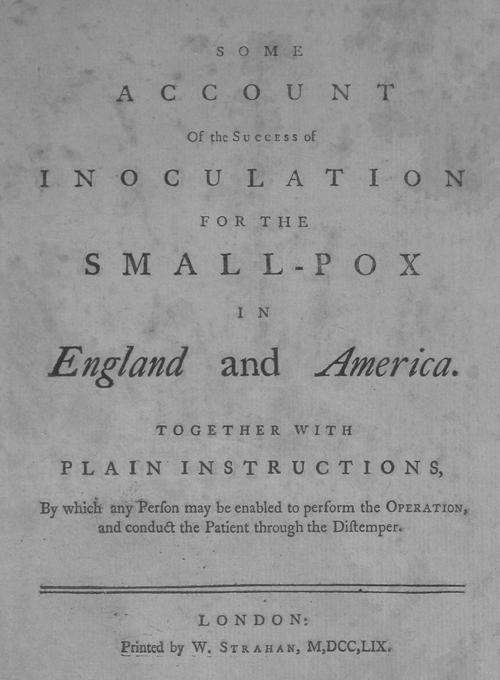

Throughout his life, Franklin monitored the success of inoculation in several colonial cities, and shared information with his correspondents about the procedure's extremely low mortality rates and the decreased smallpox incidence that resulted.6 The statistics he compiled were useful for Some Account of the Success of Inoculation for the Small-pox in England and America (Figure 2), a pamphlet he wrote with physician William Heberden. While in London, Franklin encouraged Heberden to write briefly on the value of inoculation and to include instructions by which any educated layman could inoculate his own family. Franklin wrote the preface and had 1500 copies printed and sent to the colonies for free distribution.

Figure 2.

Some Account of the Success of Inoculation for the Small-pox. Franklin, Benjamin and Heberden, William 1759, Library, College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Franklin did more than just write about medical matters. Most of his inventions provided practical solutions to everyday problems, and Franklin brought that same inventive spirit into the medical realm. His medical creations were uncomplicated and made to be immediately useful, like the flexible catheter he designed for his brother John, who suffered from bladder stone and urinary retention. Franklin designed a device in 1757, had it made by a local silversmith, and sent it to John in Boston, with a letter detailing its design and use.7 The catheter was made from silver wire, coiled with joints to allow flexibility, and covered with gut.

Most famous among his contributions to medical care were Franklin's ‘double spectacles’, better known as bifocals. He himself was probably wearing these spectacles as early as the 1750s, during his time in London.8 In several letters to London philanthropist, George Whatley, Franklin stated that he had created bifocals to avoid awkward shifting between his regular and reading glasses. Cutting his other glasses and having half of each lens placed in the same frame, Franklin believed, ‘... make my eyes as useful to me as ever they were’.9

Franklin also served the Philadelphia medical scene with his skills as an organizer and philanthropist. In 1751 Franklin's friend, Dr Thomas Bond, began a campaign to raise money for what would be the first voluntary hospital in the colonies. Bond had little success raising money and turned to Franklin for assistance. Franklin supported the idea completely and agreed to become a subscriber. His involvement had the desired effect, and once he was involved in the project funds were raised easily. He then petitioned the Pennsylvania Assembly for support and convinced the legislators to match the voluntary funds if he and Bond could solicit £2000 from citizens of the colony. The founders used the Assembly's promise of matching funds to encourage private donors, and the necessary sum was soon raised. Pennsylvania Hospital received its charter in May 1751 and, in 1756, the first patients were admitted to the hospital's building at Eighth and Pine Streets. Franklin served on the hospital's board for a number of years, and sought support from abroad for the institution during his time in London.

Franklin enjoyed good health. While most images of Franklin show him in prosperous middle age or as an elderly statesman, he was a strong and active youth. As a young man, Franklin's most serious afflictions were respiratory illnesses. He was thus very interested in the common cold and its causes. He dismissed the popular notion that changes in temperature, particularly exposure to cold air, made people apt to catch cold. He suggested instead that putrid matter in the air was responsible. Because of this belief, Franklin championed proper ventilation as essential to good health, noting that:

‘I am persuaded that no common Air from without, is so unwholesome as the Air within a close Room, that has been often breath'd and not changed.’10

Franklin advocated as much exposure to fresh air as possible and frequently slept with an open window. He enjoyed a daily air bath to cleanse his skin. This involved sitting naked in his chambers with the windows open.

Other than frequent respiratory problems, Franklin suffered two common eighteenth-century complaints: gout and pain from bladder stones. These were largely nuisance diseases in Franklin's middle years, and he was fortunate to enter his seventies still active and mentally focused. His gout attacks began in his forties and continued intermittently for the rest of his life—with occasional attacks in his knees, feet and hands so severe as to render him bedridden. He often returned to a simple diet when dealing with this problem and he believed that exposing his afflicted limbs to fresh air was also helpful. As late as 1783, at the age of 76, Franklin faced gout attacks philosophically, noting:

‘I have been lately ill with a Fit of the Gout, if that may indeed be called a Disease; I rather suspect it to be a Remedy; since I always find my Health and Vigour of Mind improv'd after the Fit is over.’11

As he advanced into his eighties, Franklin's health increasingly failed. His bladder stone grew, causing him pain in movement and curtailing the active life he had enjoyed before then. The stone was probably sizable by the time it began to cause Franklin difficulty, and it only grew larger. Late in his life, he noted that he could actually feel the weight of the stone moving in his body when he rolled over in bed or shifted position. Franklin's stone was too large for surgery by the time it caused him the greatest suffering. With the high risks of any procedure where cutting was involved, and his advanced age making the operation even more dangerous, Franklin chose to manage the stone as best he could with diet and gentle exercise. In a 1787 letter to the Comte de Buffon, a friend and fellow sufferer, Franklin noted that he had ‘... tried all the noted Prescriptions for diminishing the Stone, without procuring any good Effect. But observing Temperance in Eating, avoiding wine and Cyder, and using daily the Dumb Bell, which exercises the upper Part of the Body without much moving the Parts in contact with the Stone, I think I have prevented its Increase’.12

In his final years, Franklin took opium to combat the severe pain resulting from the stone and he was often bedridden. He died 17 April 1790, after suffering a bout of pneumonia and pleurisy.

With the breadth of his commentary, and the useful products of his inventiveness, Franklin's medical legacy continues to the present. His wit and wisdom on diet, health care and moderate living, as written in Poor Richard's Almanac, is still part of the public consciousness. Almost immediately after his death, authors began quoting and reprinting Franklin's advice to give their own works legitimacy and to boost sales. We may now be able to quantify the calories burned during exercise or the nutritional content in our diet, but Franklin's advice, made long before such activities were possible or even understood, still rings true in its simplicity.

In a larger sense, Franklin's medical legacy is similar to the legacy of the Enlightenment world in which he lived—a legacy of public health initiatives and ideas about improvement through moderation and human enterprise. Franklin's thoughts and inventions fit squarely into this heritage, from his campaign against smallpox that paved the way for acceptance of vaccination (announced by Edward Jenner within a decade of Franklin's death) to his invention of spectacles that could serve two purposes simultaneously. Because his thoughts on health and medicine depended so much upon people taking an active role in remaining healthy and improving society, the medical world of Benjamin Franklin will continue to have relevance and influence for years to come.

References

- 1.Letter from Benjamin Franklin to Josiah and Abiah Franklin, 6 September 1744. Benjamin Franklin Papers. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society

- 2.Letter from Benjamin Franklin to Sir John Pringle, December 21, 1757. In: Benjamin Franklin. Experiments and Observations on Electricity made at Philadelphia in America, 4th edn. London: David Henry, 1769

- 3.Letter from Sir John Pringle to Benjamin Franklin, March 1767. Benjamin Franklin Papers. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society

- 4.Letter from Benjamin Franklin to Cadwalader Evans, 20 February 1768. In: Samuel Hazard, ed. Hazard's Reg Pennsylvania 1835;16 66 [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Pennsylvania Gazette 30 December 1736

- 6.Letter from Benjamin Franklin to William Vassall, 29 May 1746; Letter from Benjamin Franklin to John Perkins, 13 August 1752. Benjamin Franklin Papers. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society

- 7.Letter from Benjamin Franklin to John Franklin, 8 December 1752. History of Medicine Collections. New York: Academy of Medicine

- 8.Letocha, Charles E. The Invention and Early Manufacture of Bifocals. Survey of Ophthalmology 1990;35: 226-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Letter from Benjamin Franklin to George Whatley, 21 August 1784

- 10.Letter from Benjamin Franklin to Jan Ingenhousz, 28 August 1785

- 11.Letter from Benjamin Franklin to Mary Stevenson Hewson, 7 September 1783. Benjamin Franklin Papers. Conneticut: Yale University Library

- 12.Letter from Benjamin Franklin to the Comte de Buffon, 4 November 1787