Abstract

The anaerobic ammonia-oxidizing activity of the planctomycete Candidatus “Brocadia anammoxidans” was not inhibited by NO concentrations up to 600 ppm and NO2 concentrations up to 100 ppm. B. anammoxidans was able to convert (detoxify) NO, which might explain the high NO tolerance of this organism. In the presence of NO2, the specific ammonia oxidation activity of B. anammoxidans increased, and Nitrosomonas-like microorganisms recovered an NO2-dependent anaerobic ammonia oxidation activity. Addition of NO2 to a mixed population of B. anammoxidans and Nitrosomonas induced simultaneous specific anaerobic ammonia oxidation activities of up to 5.5 mmol of NH4+ g of protein−1 h−1 by B. anammoxidans and up to 1.5 mmol of NH4+ g of protein−1 h−1 by Nitrosomonas. The stoichiometry of the converted N compounds (NO2−/NH3 ratio) and the microbial community structure were strongly influenced by NO2. The combined activity of B. anammoxidans and Nitrosomonas-like ammonia oxidizers might be of relevance in natural environments and for technical applications.

Two different metabolic pathways for anaerobic ammonia oxidation by lithotrophic microorganisms have been described (8, 14). The anaerobic ammonia oxidation by the planctomycete Candidatus “Brocadia anammoxidans” is a nitrite-dependent reaction. The reaction mechanism of this anammox process was examined in a laboratory-scale fluidized bed reactor by using 15N-labeled compounds. Ammonia is oxidized with hydroxylamine as the most probable electron acceptor, and hydrazine is the first detectable intermediate (22). Subsequently, the hydrazine is oxidized to dinitrogen gas. The four reducing equivalents are transferred to nitrite, forming hydroxylamine. During the conversion of ammonia, some nitrate is formed from nitrite. This reaction could provide reducing equivalents necessary for the fixation of carbon dioxide (22). The overall nitrogen balance shows a ratio of about 1:1.32:0.26 for the conversion of ammonia, nitrite, and nitrate (18). The overall anammox reaction is presented in equation 1.

|

(1) |

Under optimal growth conditions the specific anammox activity is about 3 mmol of NH4+ g of protein−1 h−1. The affinity for the substrates ammonia and nitrite is high, and the Ks values are less than 10 μM (5, 19). Interestingly, nitrite concentrations of 5 mM or higher and oxygen concentrations as low as 2 μM completely, but reversibly, inhibit the anammox activity (17). During the conversion of ammonia and nitrite no other intermediates or products, such as NO or N2O, could be detected.

The obligately anaerobic nature of B. anammoxidans is in sharp contrast with the more versatile metabolism of Nitrosomonas strains (1, 2, 10). The latter organisms are able to gain energy by aerobic or anaerobic ammonia oxidation or by denitrification by using hydrogen or organic compounds as the electron donor (2). The anaerobic ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas is a nitrogen dioxide-dependent reaction (12). It has been shown that N2O4, the dimeric form of NO2, is used as an oxidant (13). About 50% of the nitrite produced is used as a terminal electron acceptor and is converted to N2 (equation 2).

|

(2) |

In a pure culture, the specific anaerobic ammonia oxidation activity of Nitrosomonas eutropha is about 0.15 mmol of NH4+ g of protein−1 h−1. In contrast to B. anammoxidans, Nitrosomonas produces significant amounts of nitric oxide and nitrous oxide during ammonia oxidation. The nitrogen oxides, NO and NO2, are obligatory intermediates in the oxidation of ammonia (14), and they have regulatory effects on the metabolism of the nitrifiers (16, 23).

NO has toxic effects on many microorganisms (4, 6, 15, 24), but the effect on the anammox activity of planctomycetes is still unknown. In natural and man-made environments (e.g., wastewater treatment plants) these organisms may be exposed to high NO concentrations and frequently also to high NO2 concentrations The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of nitrogen oxides on the ammonia oxidation of B. anammoxidans. Furthermore, the influence of NO and NO2 on the microbial community structure and the specific ammonia oxidation activities of B. anammoxidans and Nitrosomonas were evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

An anammox enrichment culture containing about 80% B. anammoxidans (5 × 108 cells ml−1) was grown in a 2-liter sequencing batch reactor (18). Cells of N. eutropha strain N904 (isolated from cattle manure) were grown as described previously (12).

Medium and growth conditions.

Precultures of the anammox biomass were grown anaerobically at 28°C and pH 7.5. The mineral medium contained (per liter of demineralized water) 2.02 g of NaNO2, 1.96 g of (NH4)2SO4, 1.25 g of KHCO3, 25 mg of KH2PO4, 300 mg of CaCl2 · 2H2O, 200 mg of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 6.25 mg of FeSO4, 6.25 mg of EDTA, 25 ml of HCl (1 M), and 25 ml of a trace element solution. The trace element solution contained (per liter of demineralized water) 15 g of EDTA, 430 mg of ZnSO4 · 7H2O, 240 mg of CoCl2 · 6H2O, 990 mg of MnCl2 · 4H2O, 250 mg of CuSO4 · 5H2O, 220 mg of NaMoO4 · 2H2O, 190 mg of NiCl2 · 6H2O, 210 mg of NaSeO4 · 10H2O, and 14 mg of H3BO4. The influx of fresh medium into the 2-liter reactor was adjusted to 170 ml h−1.

Precultures of N. eutropha were grown aerobically in a 10-liter sequencing batch reactor in mineral medium (12) aerated with 2 liters of air min−1. The pH was kept at 7.5 by using a 20% Na2CO3 solution.

Experimental design.

Experiments were performed in a 2-liter laboratory-scale reactor with 1.7 liters of medium; 170 ml of fresh medium was added per hour, and the same volume was removed from the reactor. The effluent was filtered by using a hollow fiber membrane module (0.4 m2) with membranes consisting of polysulfone and a cutoff of 6 kDa (SPS 6005-6; Fresenius, St. Wendel, Germany) to achieve complete biomass retention (cross-flow filtration). While the cell-free medium (170 ml h−1) was removed, the biomass was routed back into the reactor. Depending on the experiment the concentrations of substrates (ammonia and nitrite) in the fresh medium varied between 0 and 100 mM. The reactor was gassed with a 95% argon-5% CO2 gas mixture supplemented with 0 to 1,000 ppm of NO or NO2 at a rate of 0.5 to 1 liter min−1 by using mass flow controllers. The level, temperature, dissolved oxygen content, and pH were permanently controlled (Applikon, Schliedam, The Netherlands). The temperature was maintained at 28°C. The pH was kept at 7.5. Due to cell growth the biomass concentration in the reactor increased. Every 3 days the biomass concentration was measured by protein determination, and the biomass concentration was adjusted to about 80 μg of protein ml−1 (5 × 108 cells ml−1) by removing small amounts of biomass from the reactor.

Batch experiments were carried out in 100-ml glass bottles that were sealed with butyl rubber stoppers and contained 20 ml of mineral medium. The bottles were flushed with a 95% argon-5% CO2 gas mixture supplemented with 0 to 1,000 ppm of NO. The anammox biomass (80% B. anammoxidans) was purified by density gradient centrifugation (99.6% ± 0.2% B. anammoxidans) as described previously (20). During the experiments (8 h) the cell suspension (5 × 109 cells ml−1) was stirred (800 rpm) to ensure efficient gas transfer. NO consumption was calculated on the basis of the difference in the NO concentrations at the beginning and at the end of an experiment. Control experiments were carried out with cell-free medium and heat-sterilized cell suspensions. The chemical conversion rates were low (less than 3% of the biological conversion rates).

Analytical procedures.

Measurements were carried out as described by Schmidt and Bock (12) (NH4+, NO, and NO2), Van de Graaf et al. (21) (NO2− and NO3−), and Bradford (3) (protein concentration). Most-probable-number (MPN) analysis was performed as described by Mansch and Bock (7), and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed as described by Neef et al. (9). The following probes were used: NEU 653 (specific for Nitrosomonas-like microorganisms) and Amx 820 (specific for planctomycete-like bacteria). The FISH and MPN methods were used to determine the numbers of planctomycete and Nitrosomonas cells in the reactor. 4′,6′-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining was used to determine the total cell number.

Determination of ammonia oxidation activity.

The aerobic ammonia oxidation activity of N. eutropha was determined by short-term activity tests (2 h). The tests were performed in 100-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 10 ml of mineral medium (12). The protein concentration was measured, and the time-dependent consumption of ammonia was determined. The aerobic ammonia oxidation activity was used to estimate the numbers of Nitrosomonas cells in the anammox systems. The method was calibrated with anaerobically grown N. eutropha cells (13), and the correlation between cell number and the amount of ammonia converted was determined; 107 cells oxidized 40 ± 3.3 nmol of NH4+ h−1. This method was used to confirm the results of the FISH and MPN analyses. Due to the presence of colonies the MPN method underestimates the number of cells (7); the activity method tends to overestimate the number of cells.

RESULTS

Effects of NO2 and NO on anammox reactor systems.

The initial experiments were designed to investigate the influence of nitrogen oxides on the nitrogen conversion activities in anammox systems. For these experiments, anammox biomass precultured for 3 months in the absence of NOx was supplemented with increasing amounts of NO2 or NO. The NOx concentration was increased every 2 weeks. Throughout the experiments the ammonia and nitrite concentrations were adjusted to about 4 and 0.5 mM, respectively. After the NOx concentration was increased, the system adapted within 1 week to the new conditions. In the second week the nitrogen conversion activities were measured every day, and the mean values were calculated (the standard deviation was ±6.5%). The results of the experiments which were performed in the presence of NO2 are shown in Fig. 1.

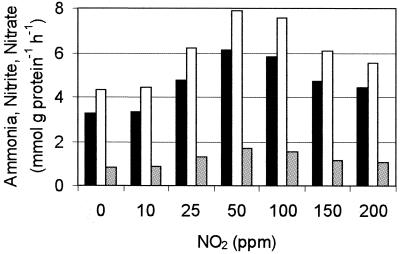

FIG. 1.

Specific ammonia (solid bars) and nitrite (open bars) consumption rates and nitrate production rates (shaded bars) in an anammox system supplemented with different concentrations of NO2. According to the Mann-Whitney U test, the increases in activity as the NO2 concentration was increased up to 50 ppm and the decreases in activity at NO2 concentrations between 50 and 200 ppm are highly significant (error rate, 0.005). The experiments were repeated three times.

When the NO2 concentration in the gas mixture used for gassing was increased, ammonia and nitrite consumption, as well as nitrate production, increased. The highest ammonia and nitrite conversion rates observed in the presence of 50 ppm of NO2 were about two times higher than the conversion rates in the absence of NO2. A further increase in the NO2 concentration resulted in slowly decreasing anaerobic ammonia oxidation activities. In the absence of NO2 the growth rate of B. anammoxidans was about 0.003 h−1, in the presence of 50 ppm of NO2 the growth rate was about 0.004 h−1, and in the presence of 200 ppm of NO2 the growth rate was about 0.0028 h−1. According to a Mann-Whitney U test the differences in the growth rates are significant (error rate, 0.05).

To enlarge the statistical basis for the observed effects, short-term batch experiments were performed to examine the effect of NO2 (0 to 200 ppm) on the anammox biomass (10 replicate experiments). Again, the highest activities were measured in the presence of 50 ppm of NO2 (the activities were 1.5 times higher than those in an NO2-free control). Interestingly, the ratio between ammonia and nitrite consumption changed depending on the NO2 concentration (Table 1). When no gaseous NO2 was added, the NO2−/NH3 ratio was about 1.3, as previously determined by Strous et al. (18). When the NO2 concentration was increased to 200 ppm, the NO2−/NH3 ratio decreased to about 1.25.

TABLE 1.

NO2−/NH3 consumption ratios in anammox reactors in the presence of NO2 or NO

| NOx concn (ppm) | NO2−/NH3 ratio in the presence of NO2 | NO2−/NH3 ratio in the presence of NO |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.33 | 1.30 |

| 10 | 1.32 | 1.44 |

| 25 | 1.30 | 1.39 |

| 50 | 1.28 | 1.37 |

| 100 | 1.29 | 1.49 |

| 150 | 1.28 | 1.34 |

| 200 | 1.25 | 1.50 |

| 600 | NDa | 1.53 |

| 1,000 | ND | 2.58 |

ND, not determined.

The influence of NO2 addition on the composition of the microbial community in the reactor was evaluated by FISH, MPN, and activity tests (Table 2). Throughout the experiment small amounts of the biomass were removed regularly (every 3 days) to keep the biomass content of the reactor constant. Therefore, the number of B. anammoxidans cells remained unchanged (about 5 × 108 cells ml−1). In contrast, the number of Nitrosomonas cells increased significantly in the presence of NO2. The ratio of B. anammoxidans cells to Nitrosomonas cells changed from about 2 × 106:1 to about 30:1.

TABLE 2.

Numbers of B. anammoxidans and Nitrosomonas cells in reactors supplemented with NO2 or NOa

| NOx (ppm) | No. of cells (ml−1) in the presence of:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO2

|

NO

|

|||||||

| B. anammoxidans (FISH analysis)b | Nitrosomonas (FISH analysis)c,d | Nitrosomonas (MPN analysis)d | Nitrosomonas (activity test)e,f | B. anammoxidans (FISH analysis)b | Nitrosomonas (FISH analysis) | Nitrosomonas (MPN analysis)g | Nitrosomonas (activity test)e,g | |

| 0 | 5.1 × 108 | NDh | 1.7 × 103 | 2.3 × 102 | 6.9 × 108 | ND | 2.6 × 103 | 5.9 × 102 |

| 10 | 5.2 × 108 | ND | 6.3 × 103 | 6.1 × 104 | 7.2 × 108 | ND | 2.7 × 103 | 5.3 × 102 |

| 25 | 5.0 × 108 | ND | 1.3 × 104 | 4.7 × 105 | 6.5 × 108 | ND | 2.0 × 103 | 5.7 × 102 |

| 50 | 5.0 × 108 | 4.5 × 105 | 3.3 × 104 | 1.6 × 106 | 6.9 × 108 | ND | 2.2 × 103 | 5.0 × 102 |

| 100 | 5.1 × 108 | 1.2 × 106 | 9.1 × 104 | 4.7 × 106 | 6.5 × 108 | ND | 1.6 × 103 | 3.9 × 102 |

| 150 | 5.1 × 108 | 2.7 × 106 | 2.9 × 105 | 1.2 × 107 | 7.6 × 108 | ND | 8.4 × 102 | 1.9 × 102 |

| 200 | 5.2 × 108 | 6.4 × 106 | 7.6 × 105 | 1.8 × 107 | 6.9 × 108 | ND | 4.9 × 102 | 1.1 × 102 |

The number of B. anammoxidans cells was controlled by biomass removal.

The standard deviation was 7%. According to the Mann-Whitney U test the constant cell number is highly significant (error rate, 0.005).

The standard deviation was 18%.

According to the Mann-Whitney U test the increasing cell number with increasing NO2 concentration is significant (error rate, 0.05).

The standard deviation was 9%.

According to the Mann-Whitney U test the increasing cell number with increasing NO2 concentration is highly significant (error rate, 0.005).

According to the Mann-Whitney U test the decreasing cell number with increasing NO concentration is significant (error rate, 0.05).

ND, not detectable.

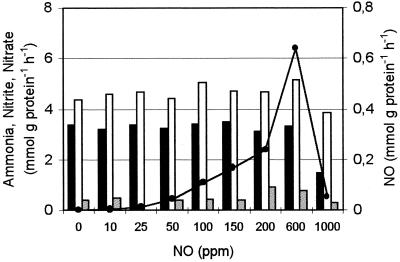

The effect of nitric oxide was investigated by using a similar experimental design, but the reactors were gassed with a gas mixture that consisted of argon (95%), carbon dioxide (5%), and NO. The NO concentration was increased every 2 weeks until the final value of 1,000 ppm was reached after 16 weeks (Fig. 2). The specific ammonia consumption activity remained unchanged in the presence of concentrations of NO between 0 and 600 ppm. In contrast, the specific nitrite consumption activity increased significantly as the NO concentration was increased. As a consequence, the NO2−/NH3 ratio increased (Table 1). Furthermore, increasing amounts of NO were consumed (Fig. 2). Strong inhibition of the specific ammonia, nitrite, and NO consumption activities was observed with 1,000 ppm of NO (Fig. 2). The growth rate remained unchanged at 0.003 h−1 in the presence of 0 to 600 ppm of NO but decreased to about 0.001 h−1 in the presence of 1,000 ppm of NO. Throughout the experiments the number of B. anammoxidans cells was controlled and remained 5 × 108 cells ml−1 (Table 2). The number of active Nitrosomonas cells decreased about fivefold (from 5.9 × 102 to 1.1 × 102 cells ml−1). NO consumption (detoxification) by B. anammoxidans was also examined in short-term batch experiments with purified biomass (purity, 99.6% ± 0.2%; concentration, 5 × 108 cells ml−1). In three replicate experiments NO consumption rates of 0, 0.1, and 0.4 mmol of NO g of protein−1 h−1 and ammonia oxidation activities of 2.3, 2.4, and 1.4 mmol g of protein−1 h−1 were measured in the presence of 0, 100, and 1,000 ppm of NO, respectively. Interestingly, the NO consumption rate increased as the NO concentration increased.

FIG. 2.

Specific ammonia (solid bars), nitrite (open bars), and NO (•) consumption rates and nitrate production rates (shaded bars) in a reactor supplemented with different concentrations of NO. According to the Mann-Whitney U test, the specific ammonia consumption activity was constant as the NO concentration was increased up to 600 ppm (error rate, 0.05), and the specific nitrite consumption activity increased (error rate, 0.1). Two replicated experiments were performed.

Influence of Nitrosomonas on anammox reactor systems.

The experiments in which NO2 was added showed that high numbers of active Nitrosomonas cells can have a strong influence on the N conversion rates in anammox reactors. This influence was studied in laboratory-scale reactors inoculated with a mixed population of B. anammoxidans (about 108 cells ml−1) and N. eutropha (0, 107, 5 × 107, or 108 cells ml−1). The experiments were performed for 2 days in the presence of 200 ppm of NO2 and an excess of ammonia; nitrite was limiting. The ammonia, nitrite, and NO2 consumption rates, as well as the nitrate and NO production rates, were determined, and the NO2−/NH3 ratio was calculated. The results are shown in Table 3. When the anammox system was supplemented with N. eutropha, the conversion of nitrogen compounds changed significantly. Ammonia and NO2 consumption and NO production increased. Nitrite consumption remained unchanged. The NO2−/NH3 ratio decreased from 1.3 to 0.82, indicating that Nitrosomonas produced nitrite, which was directly consumed by B. anammoxidans.

TABLE 3.

N conversion rates, NO2−/NH3 ratios, and N loss in 2-liter reactorsa

| No. of N. eutropha cells (ml−1) | Conversion rates (μmol reactor−1 h−1)

|

NO2−/NH3 ratio | Sp act (μmol of NH4+ g of protein−1 h−1)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonia | Nitrite | NO2b | NO | Nitrate | B. anammoxidansc | N. eutrophad | ||

| 0e | 141.4 | 187.9 | 0 | 0.01 | 36.8 | 1.33 | 4,423 | |

| 107 | 149.9 | 191.4 | 14.4 | 13.5 | 38.1 | 1.28 | 4,579 | 1,080 |

| 5 × 107 | 183.8 | 183.2 | 70.6 | 71.2 | 41.3 | 1.00 | 4,963 | 1,462 |

| 108 | 226.2 | 185.8 | 129.4 | 119.1 | 49.3 | 0.82 | 5,525 | 1,545 |

The reactor with the anammox biomass was supplemented with 0, 107, 5 × 107, or 108 N. eutropha cells ml−1. The consumption and production rates were calculated on the basis of the substrates added to the reactor and the products leaving the reactor. The standard deviation for five replicate experiments was less than ± 5%.

In sterile control experiments, the NO2 consumption resulting from the reaction of NO2 with water was determined. The values obtained were subtracted from the data obtained with cells.

The specific ammonia oxidation activity of B. anammoxidans was calculated on the basis of nitrate production.

The specific ammonia oxidation activity of N. eutropha was calculated on the basis of NO2 consumption and NO production.

The anammox biomass contained about 2 × 103 Nitrosomonas cells ml−1.

The anoxic activity of N. eutropha resulted in levels of ammonia and NO2 consumption and NO production similar to the expected 1:2:1 ratio shown in equation 2 (13). About 50% of the ammonia consumed should have been converted to nitrite. However, in the presence of excess ammonia B. anammoxidans immediately converted this nitrite to N2.

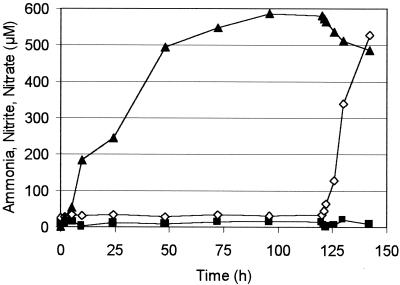

Only when ammonia was the limiting substrate did B. anammoxidans and N. eutropha have to compete for ammonia. Due to the ammonia limitation, the additional nitrite produced by N. eutropha could not be converted by B. anammoxidans and therefore should have accumulated in the reactor. The N conversion in an ammonia-limited anammox reactor (108 cells ml−1) supplemented with nitrite and 250 ppm of NO2 is shown in Fig. 3. After 120 h N. eutropha (108 cells ml−1) was added. Before N. eutropha was present, B. anammoxidans consumed all of the ammonia and nitrite added with the fresh medium; the concentrations of these compounds in the reactor were low, and increasing concentrations of nitrate were detected. After N. eutropha was added, the concentration of nitrite increased rapidly (Fig. 3), NO2 was consumed, and NO was produced (data not shown), indicating an NO2-dependent ammonia oxidation activity of N. eutropha. The decreasing nitrate concentration indicated that the activity of B. anammoxidans was reduced, which was most likely due to competition with N. eutropha for ammonia. When the ammonia limitation in the reactor was eliminated, the nitrite concentration decreased to less than 10 μM and the nitrate concentration reached about 850 μM (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Ammonia (▪), nitrite (◊), and nitrate (▴) concentrations in a reactor before (0 to 120 h) and after (120 to 142 h) the addition of N. eutropha. The NO2 concentration was adjusted to 200 ppm. The cell concentrations were adjusted to 108 B. anammoxidans cells ml−1 and 108 N. eutropha cells ml−1.

B. anammoxidans-N. eutropha community with ammonia and gaseous NO2 as substrates.

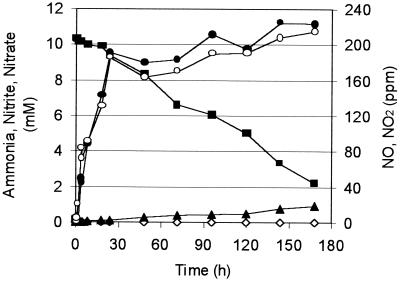

On the basis of equations 1 and 2, we speculated that ammonia and gaseous NO2 are suitable substrates for a combined Brocadia-Nitrosomonas community. Nitrosomonas seems to be able to produce nitrite, N2, and NO by combined ammonia oxidation and denitrification (equation 2). Ammonia and the nitrite produced may be further converted to nitrate and N2 by B. anammoxidans (equation 1). The specific ammonia oxidation activity of B. anammoxidans is dependent on the rate of nitrite production by N. eutropha. Such a coculture was examined in a reactor containing mineral medium (10 mM ammonia). The reactor was inoculated with 108 cells of B. anammoxidans ml−1 and 108 cells of N. eutropha ml−1. The reactor was gassed at a rate of 0.5 liter min−1 with a 95% argon-5% carbon dioxide gas mixture supplemented with 250 ppm of NO2. Immediately after inoculation ammonia and NO2 consumption started (Fig. 4). Throughout the experiment nitrate and NO were produced, but nitrite did not accumulate (the concentration was always less than 20 μM). On the basis of NO2 consumption, the specific anaerobic ammonia oxidation activity of N. eutropha was calculated to be about 1.6 mmol g of protein−1 h−1. The production of nitrate was used to calculate the specific activity of B. anammoxidans (about 0.9 mmol of NH4+ g of protein−1 h−1). In sterile control experiments the chemical formation of nitrite and nitrate by reaction of NO2 with water was determined. The values obtained in the control experiments were taken into account when the specific activity of B. anammoxidans was calculated.

FIG. 4.

Ammonia (▪), nitrite (◊), and nitrate (▴) concentrations, NO2 consumption (•) (NO2 fresh gas minus NO2 off gas), and NO production (○) (NO concentration in the off gas) in a B. anammoxidans-N. eutropha system with ammonia and NO2 as the only substrates. The cell concentrations were adjusted to 108 B. anammoxidans cells ml−1 and 108 N. eutropha cells ml−1.

DISCUSSION

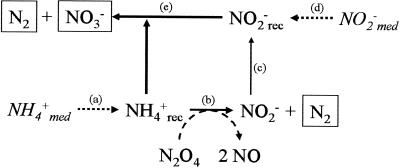

The results presented here show that Brocadia and Nitrosomonas are able to coexist under anoxic conditions. While B. anammoxidans uses nitrite as a substrate and Nitrosomonas uses gaseous NO2 as a substrate, these organisms compete for ammonia. Key elements used to analyze the results of this study are shown in Fig. 5 and in equations 1 and 2 describing anaerobic ammonia oxidation by Brocadia and Nitrosomonas. It is important to note that Nitrosomonas produces nitrite during anaerobic ammonia oxidation, which can serve as a substrate for Brocadia (Fig. 5). The assumption that this additional nitrite is consumed by Brocadia when ammonia is not the limiting substrate was confirmed in this study. As a consequence, the NO2−/NH3 ratio in such a mixed population changes depending on the metabolic activities of the two ammonia oxidizers. Since this is important for interpretation of the results, it is illustrated below with a theoretical example (equations 3 to 5 [equation 5 is the sum of equations 3 and 4]).

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

FIG. 5.

Schematic model describing the competition and cooperation between B. anammoxidans and Nitrosomonas under anoxic conditions. (a), ammonia addition (fresh medium); (b), ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas; (c), additional nitrite in the reactor due to ammonia oxidation; (d), nitrite addition (fresh medium); (e), anammox reaction; med, medium; rec, reactor. End products are enclosed in boxes.

In an anammox reactor system without active Nitrosomonas cells (equation 3), the NO2−/NH3 ratio is about 1.3. If actively ammonia-oxidizing Nitrosomonas cells are present (equation 4), the NO2−/NH3 ratio of the system decreases to about 0.4 (equation 5) when the two organisms contribute equally to ammonia consumption. According to this calculation the presence of ammonia-oxidizing Nitrosomonas cells should be indicated by a decrease in the NO2−/NH3 ratio. Hence, on the basis of this ratio the contributions of B. anammoxidans and Nitrosomonas to the total ammonia conversion in a mixed population can be calculated. Our results (Table 3) indicate that the NO2−/NH3 ratio was 0.82 in the presence of 108 cells of B. anammoxidans ml−1 and 108 cells of N. eutropha ml−1. According to equations 3 to 5 B. anammoxidans accounts for about 75% and N. eutropha accounts for about 25% of the total anaerobic ammonia oxidation. The NO2−/NH3 ratios presented in Tables 1 and 3 provide a strong indication that there is simultaneous anaerobic ammonia oxidation by B. anammoxidans and Nitrosomonas.

When the number of N. eutropha cells in the mixed population supplied with NO2, ammonium, and nitrite was increased, the total ammonia consumption of the system was stimulated and the NO2−/NH3 ratio decreased significantly (from 1.33 to 0.82). Furthermore, both NO2 consumption and NO production were detectable, indicating that anaerobically ammonia-oxidizing N. eutropha cells were present. When N. eutropha oxidized ammonia, nitrite was produced, but nitrite did not accumulate in the reactor. It is very likely that B. anammoxidans consumed the additional nitrite, resulting in a higher specific ammonia oxidation activity, which was also indicated by an increased rate of production of nitrate (Table 3 and Fig. 5). When ammonia was the limiting substrate (Fig. 3), B. anammoxidans was not able to adapt its activity to the increased nitrite supply (nitrite in the fresh medium plus nitrite produced by Nitrosomonas), and therefore, nitrite accumulated in the system.

The results shown in Table 3 were used to calculate the anaerobic ammonia oxidation activities of B. anammoxidans and N. eutropha. Nitrate production is directly correlated to the activity of B. anammoxidans (equation 1), because N. eutropha is unable to produce or consume nitrate. According to the nitrate production data (Table 3), the specific anaerobic ammonia oxidation activity of B. anammoxidans ranged from 4.4 to 5.4 mmol of NH4+ g of protein−1 h−1. On the basis of NO2 consumption and NO production, a specific activity for N. eutropha of between 1.1 and 1.5 mmol of NH4+ g of protein−1 h−1 was calculated. Interestingly, the specific anaerobic ammonia oxidation activity of N. eutropha in this mixed culture was about 10 times higher than that measured in a pure culture (12). In pure cultures, NO2 concentrations of more than 50 ppm were toxic for N. eutropha. In anammox systems NO2 concentrations as high as 250 ppm were not inhibitory. The possibility that N. eutropha cells in a mixed population are supplied with higher NO2 concentrations might explain the high anaerobic ammonia oxidation activity of such cells.

Simultaneous anaerobic ammonia oxidation activities of B. anammoxidans and N. eutropha were also detectable when ammonia was the limiting substrate (Fig. 3). An anammox system was grown with low ammonium and nitrite concentrations in the reactor. Nitrate was produced and accumulated in the medium. When N. eutropha (108 cells ml−1) was added, the consumption of NO2 and the production of nitrite and NO indicated that there was anaerobic ammonia oxidation activity by N. eutropha. Since the ammonia supply was not increased, B. anammoxidans and N. eutropha had to compete for this limited resource. As a result of the competition, the specific activity of B. anammoxidans decreased, as indicated by a decreasing nitrate concentration.

In an anammox reactor system without added N. eutropha cells (Fig. 1 and 2) the total activity of the system increased significantly when up to 50 ppm of NO2 was added (Fig. 1). A further increase in the NO2 concentration led to decreases in activity. The growth rate of B. anammoxidans increased only 1.4-fold, while the specific ammonia oxidation activity increased about 2-fold (Fig. 1) when the NO2 concentration was increased from 0 to 50 ppm. Perhaps parts of the reducing equivalents generated during ammonia oxidation are necessary for the conversion (reduction) of NO2. In contrast to the stable number of B. anammoxidans cells (the cell number was adjusted to about 5 × 108 cells ml−1 every 3 days), the number of Nitrosomonas cells increased from about 103 to 107 cells ml−1 (Table 2) (the growth rate was about 0.005 h−1). The ammonia oxidation activity of Nitrosomonas provided the system with additional nitrite, which was consumed by B. anammoxidans. Obviously, the increased specific activities of both B. anammoxidans (more nitrite available) and Nitrosomonas (NO2 available) led to higher N conversion activities in the reactor (Fig. 1) (0 to 50 ppm of NO2). Apparently, concentrations of NO2 higher than 50 ppm were inhibitory for B. anammoxidans in this system (Fig. 1). The cell number (Table 2) and the specific activity (Table 3) of Nitrosomonas were too low to compensate for the NO2-inhibited activity of B. anammoxidans (NO2 concentrations greater than 50 ppm). When the reactor system was incubated without supplemental NO2, Nitrosomonas was not able to oxidize ammonia (12, 14), and the conversion rates of the N compounds were dependent only on the activity of B. anammoxidans.

The situation was less complex when NO was added. The activity of the anammox system was stable at NO concentrations between 0 and 600 ppm. At higher NO concentrations the activity decreased. Under anoxic conditions in the presence of NO, Nitrosomonas was not able to oxidize ammonia (12). As a consequence, Nitrosomonas did not contribute to the ammonia oxidation activity of the system. Therefore, the N conversion rates were dependent only on the activity of B. anammoxidans. It is interesting that higher NO concentrations added to the anammox system led to increased specific NO consumption activity of B. anammoxidans (Fig. 2). The specific nitrate and NO production activities increased almost parallel to the specific nitrite consumption activity (Fig. 2). Since part of the nitrite oxidation activity provides B. anammoxidans with reducing equivalents (22), it seems likely that the electrons derived from nitrite were used to reduce NO. This might have been possible via the hydroxylamine oxidoreductase, which has some NO-reducing capacity, or via the cytochrome c nitrite reductase, producing ammonia (11). Another possibility is disproportion of NO to N2O and nitrite.

The final experiment in this study showed that B. anammoxidans and Nitrosomonas formed stable cocultures under anoxic conditions when they were supplemented with a surplus of ammonium and gaseous NO2 (Fig. 4). Under these conditions, ammonia was oxidized by N. eutropha to dinitrogen and nitrite. The nitrite produced was further converted by B. anammoxidans with ammonia as an electron donor. The model for this process is shown in Fig. 5. The ammonia oxidation activity of N. eutropha was indicated by the NO2 consumption and NO production profiles. The activity of B. anammoxidans, which was dependent on the nitrite production of N. eutropha, was indicated by the nitrate production rate. Under anoxic conditions N. eutropha converts only 50 to 60% of the ammonia consumed to nitrite (12). Because of this nitrite limitation the specific ammonia oxidation activity of B. anammoxidans (0.9 mmol g of protein−1 h−1) was lower than the specific ammonia oxidation activity of N. eutropha (1.6 mmol g of protein−1 h−1).

The results of this study provide strong indications that the anaerobic ammonia-oxidizing planctomycetes (B. anammoxidans) are not sensitive to NO concentrations up to 600 ppm and that the N conversion rates of an anammox reactor system increase about twofold in the presence of 50 ppm of NO2. Further experiments demonstrated that addition of NO2 leads to increases in the number of cells and the specific ammonia oxidation activity of Nitrosomonas under anoxic conditions. Although the two groups of ammonia oxidizers compete for ammonia, cooperation also seems to be possible when the NO2-dependent ammonia oxidation of Nitrosomonas supplies B. anammoxidans with nitrite as an oxidant. This might have ecological relevance. On the one hand, the ammonia oxidation of B. anammoxidans is restricted to anoxic environments. On the other hand, Nitrosomonas-like microorganisms need an oxidizing agent (O2 or NO2) that is available only under oxic conditions. The oxic-anoxic interface might be a suitable environment for both groups of ammonia oxidizers. The availability of ammonia and nitrite is decisive for coexistence. At the oxic-anoxic interface the ammonia oxidation of Nitrosomonas-like microorganisms might be the major source of the nitrite necessary for the nitrite-dependent anammox metabolism. The products of this cooperation are mainly N2 and small amounts of nitrate. When ammonia is the limiting substrate, the two groups of ammonia oxidizers compete for ammonia (Fig. 3), and the specific affinities for ammonia might be decisive for the outcome of the competition.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeliovich, A. 1987. Nitrifying bacteria in wastewater reservoirs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:754-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock, E., R. Stüven, I. Schmidt, and D. Zart. 1995. Nitrogen loss caused by denitrifying Nitrosomonas cells using ammonium or hydroxylamine as electron donors and nitrite as electron acceptor. Arch. Microbiol. 163:16-20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford, M. M. 1976. Rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henry, Y., C. Ducrocq, J.-C. Drapier, D. Servent, C. Pellat, and A. Guissani. 1991. Nitric oxide, a biological effector. Electron paramagnetic resonance detection of nitrosyl-iron-protein complexes in whole cells. Eur. Biophys. J. 20:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuenen, J. G., and M. S. M. Jetten. 2001. Extraordinary anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria. ASM News 67:456-463. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mancinelli, R. L., and C. P. McKay. 1983. Effects of nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide on bacterial growth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 46:198-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mansch, R., and E. Bock. 1998. Biodeterioration of natural stone with special reference to nitrifying bacteria. Biodegradation 9:47-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulder, A., A. A. van de Graaf, L. A. Robertson, and J. G. Kuenen. 1995. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation discovered in a denitrifying fluidized bed reactor. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 16:177-184. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neef, A., R. I. Amann, H. Schlesner, and K.-H. Schleifer. 1998. Monitoring a widespread bacterial group: in situ detection of planctomycetes with 16S rRNA-targeted probes. Microbiology 144:3257-3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poth, M. 1986. Dinitrogen production from nitrite by a Nitrosomonas isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:957-959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schalk, J., S. de Vries, J. G. Kuenen, and M. S. M. Jetten. 2000. Involvement of a novel hydroxylamine oxidoreductase in anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Biochemistry 39:5405-5412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt, I., and E. Bock. 1997. Anaerobic ammonia oxidation with nitrogen dioxide by Nitrosomonas eutropha. Arch. Microbiol. 167:106-111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt, I., and E. Bock. 1998. Anaerobic ammonia oxidation by cell-free extracts of Nitrosomonas eutropha. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 73:271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt, I., E. Bock, and M. S. M. Jetten. 2001. Ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas eutropha with NO2 as oxidant is not inhibited by acetylene. Microbiology 147:2247-2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt, I., D. Zart, and E. Bock. 2001. Effects of gaseous NO2 on cells of Nitrosomonas eutropha previously incapable of using ammonia as an energy source. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 79:39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt, I., D. Zart, and E. Bock. 2001. Gaseous NO2 as a regulator for ammonia oxidation of Nitrosomonas eutropha. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 79:311-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strous, M., E. van Gerven, P. Zheng, J. G. Kuenen, and M. S. M. Jetten. 1997. Ammonium removal from concentrated waste streams with the anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) process in different reactor configurations. Water Res. 31:1955-1962. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strous, M., J. J. Heijnen, J. G. Kuenen, and M. S. M. Jetten. 1998. The sequencing batch reactor as a powerful tool to study very slowly growing micro-organisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 50:589-596. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strous, M., J. G. Kuenen, and M. S. M. Jetten. 1999. Key physiology of anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3248-3250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strous, M., J. Fuerst, E. Kramer, S. Logemann, G. Muyzer, K. van de Pas, R. Webb, J. G. Kuenen, and M. S. M. Jetten. 1999. Missing lithotroph identified as new planctomycete. Nature 400:446-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van de Graaf, A. A., P. de Bruijn, L. A. Robertson, and J. G. Kuenen. 1996. Autotrophic growth of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing micro-organisms in a fluidized bed reactor. Microbiology 142:2187-2196. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van de Graaf, A. A., P. de Bruijn, L. A. Robertson, M. S. M. Jetten, and J. G. Kuenen. 1997. Metabolic pathway of anaerobic ammonium oxidation on the basis of N-15 studies in a fluidized bed reactor. Microbiology 143:2415-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zart, D., I. Schmidt, and E. Bock. 2000. Significance of gaseous NO for ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas eutropha. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 77:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zumft, W. G. 1993. The biological role of nitric oxide in bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 160:253-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]