Abstract

Objective: The Computerized Patient Record System is deployed at all 173 Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers. Providers access clinical notes in the system from a note title menu. Following its implementation at the Nashville VA Medical Center, users expressed dissatisfaction with the time required find notes among hundreds of irregularly structured titles. The authors' objective was to develop a document-naming nomenclature (DNN) that creates informative, structured note titles that improve information access.

Design: One thousand ninety-four unique note titles from two VA medical centers were reviewed. A note-naming nomenclature and compositional syntax were derived. Compositional order was determined by user preference survey.

Measurements: The DNN was evaluated by modeling note titles from the Salt Lake City VA Medical Center (n=877), Vanderbilt University Medical Center (n=554), and the Mayo Clinic (n=42). A preliminary usability evaluation was conducted on a structured title display and sorting application.

Results: Classes of note title components were found by inspection. Components describe characteristics of the author, the health care event, and the organizational unit providing care. Terms were taken from VA medical center information systems and national standards. The DNN model accurately described 97 to 99 percent of note titles from the test sites. The DNN term coverage varied, depending on component and site. Users found the DNN title format useful and the DNN-based title sorting and note review application easy to learn and quick to use.

Conclusion: The DNN accurately models note titles at five medical centers. Preliminary usability data indicate that DNN integration with title parsing and sorting software enhances information access.

Finding information in traditional paper-based medical records can be a daunting task. When searching for specific data, care providers, researchers, and administrators are forced to spend considerable time browsing through page after page of the paper chart. Although dividing the pieces of paper into groups by content type (e.g., notes, laboratory reports, and radiology results) and arranging entries by date may shorten the task, page-by-page brute-force scanning is often necessary. Clues available to the chart reader include note titles, note format, handwriting variation, and contextual understanding. Because of the time required for a thorough chart review, the medical record auditors for the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations routinely request the assistance of a medical records “guide” who is familiar with local documentation idiosyncrasies.

To improve access to clinical information, Larry Weed recommended a problem-oriented medical record that indexes note content by problem type.1–3 In theory, problem-oriented medical records offer a fundamental information retrieval improvement, but they have failed to be widely used.4–6 Many other authors have noted the shortcomings of traditional paper-based records for information retrieval.7,8

Computer-based medical records, whether problem-oriented or not, are commonly said to have the potential to improve access to patient-specific information via multi-user sharing, automated search functions, legible text, and consistent structure.9–15 Computer-based medical records are being widely implemented. For instance, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has deployed the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS)16–18 at each of its 173 medical center campuses. The Department of Defense is in the process of deploying a similar system at its 105 military treatment facilities.19 In the private sector, Kaiser Permanente is deploying its clinical information system for encounter documentation across its eight regions. Numerous other organizations have made a commitment to computer-based patient record systems10,20–27 in hopes of improving information access.

The Veterans Affairs Computerized Patient Record System

The VA is aggressively pursuing computer-based medical records. The CPRS is an “umbrella” program that integrates numerous existing computer programs for the clinical user. Its tabbed chart metaphor organizes problem lists, pharmacy data, orders, laboratory results, progress notes, vital signs, radiology results, transcribed documents, and reports from various studies, such as echocardiograms. Using the CPRS, providers can enter, edit, and sign documents electronically.

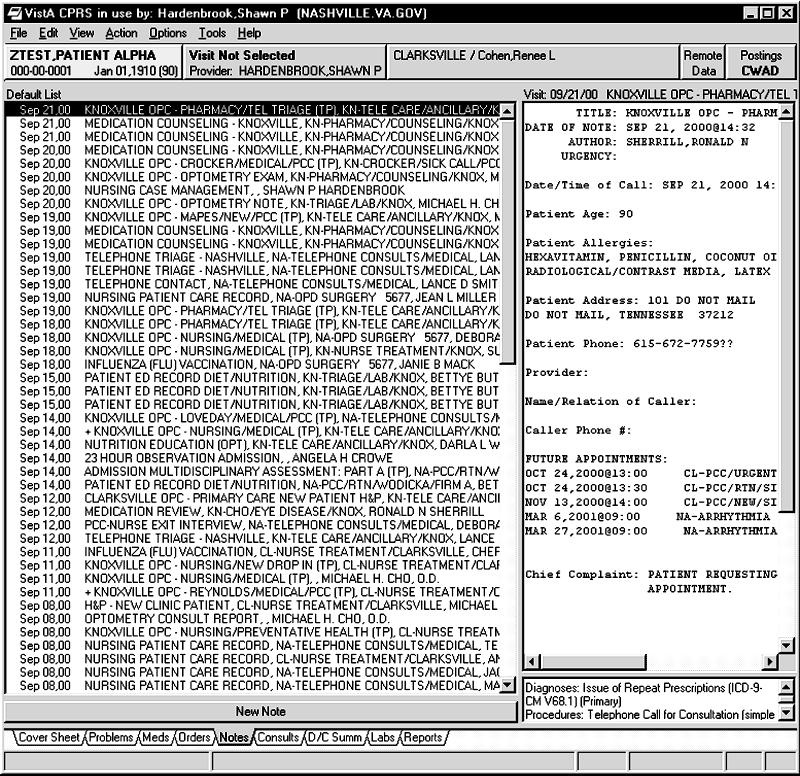

The CPRS permits users to read notes by selecting them from an onscreen note title menu (Figure 1▶). At the Nashville and Salt Lake City VA medical centers, up to 100 note titles are displayed on the menu. Other sites have chosen to display up to 500 titles. Notes are entered via the text integration utilities (TIU) by selecting one of many named, pre-formatted templates and entering the required data. The TIU templates are created and named by trained personnel called clinical applications coordinators. Clinical applications coordinators typically work closely with the medical records department and often sit on information management committees.

Figure 1.

Note titles in the Computerized Patient Record System at the Nashville Veterans Affairs Medical Center, before implementation of the document-naming nomenclature.

As CPRS use at our facilities increased, providers began to express dissatisfaction with the difficulty of finding specific notes in the electronic chart. Scanning through long lists of note titles frustrated some providers, even though the notes were legible and promptly available. A sample screen shot (Figure 1▶) helps illustrate to the reader why this might be so. An upcoming hospital merger added additional impetus to review that institution's medical document-naming methods. Concern was expressed that a combined system, containing nearly 1,200 unique note titles, might compound providers' difficulties entering and finding notes.

A proposed solution was to implement a set of “rules” for naming documents that would be easily understood by providers at each facility. Our initial hope of finding Veterans Health Administration national document-naming guidelines was not realized. We next consulted health information management texts without success. Finally, we reviewed national and international standards, such as ASTM 138428 and 1633,29 but found nothing helpful. At the time, the HL7 document ontology task force did not yet exist.

Given the lack of accepted document-naming guidelines and a pressing need for them, we decided to create our own. A complete solution to the problem would consist of three steps—creating a set of rules for naming documents, showing the usability of the resulting names in a laboratory environment, and showing efficacy of the resulting names in a production environment. The remainder of this paper describes how the document-naming nomenclature (DNN) was derived and the results of a usability evaluation.

Methods

Goals

The first step in creating the DNN was to establish design goals and constraints. The DNN was designed to be a controlled terminology for indexing and knowledge organization.30 The fundamental goal of the DNN is to create informative names that are simple to follow and create, so that untrained providers can quickly access the document they need. The intent is to maximize the utility of the name for providers directly caring for patients. We recognized that other medical record uses, such as note aggregation for research, might require different designs. To partially address this issue, we wanted a syntax that would allow computer programs to decompose and manipulate the titles easily. The CPRS limits documents to a single title of no more than 60 characters.

Empirical Review of Document Titles

All CPRS note titles in use at the Nashville and Murfreesboro campuses of the VHA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System were electronically copied and manually reviewed. A sample of “raw” note titles is shown in Table 1▶. During this process, recurrent themes in the information content of note titles were discovered. Certain categories of information, such as “note author role,” were commonly present. All unique note titles were reviewed to identify their components. Each reviewer determined candidate categories, and consensus among reviewers was achieved through discussion. Counts of categories and combinations of categories, found in the “raw” note titles, are presented in Table 2▶.

Table 1 .

▪ Sample “Raw” Document Titles

| BMT Attending Note |

| Bone Marrow (NP) |

| Bone Marrow Biopsy Procedure Note |

| Brief Operative Note—Attending |

| Brief Operative Note—Resident |

| Cardiac Transplant Follow-up |

| Cardiothoracic Surg Consult Report |

| Cardiovascular Catheterization Report |

| Care Manager Scot Clinic |

| Central Catheter Placement |

| Chaplain SVC—Group Counseling |

Table 2 .

▪ Components Present in 1,094 Unique Note Titles from Veterans Affairs Medical Centers at Nashville and Murfreesboro, Tennessee

| Component(s) | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Role | 88 | 8 |

| Problem | 124 | 11 |

| Care unit (any) | 764 | 70 |

| MDCU | 75 | 7 |

| Service | 682 | 62 |

| Section | 358 | 33 |

| Event | 916 | 84 |

| Event qualifier | 446 | 41 |

| Care Unit+Event | 599 | 55 |

| Care Unit+Role | 75 | 7 |

| Care Unit+Problem | 17 | 2 |

| Event+Role | 65 | 6 |

| Event+Problem | 117 | 11 |

| Role+Problem | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviation: MDCU indicates multidisciplinary care unit.

Nomenclature Creation

A process similar to that described by Foskett31 for the construction of faceted classifications for special subjects was employed to create the DNN. Following existing title review, we decided that the evolving controlled terminology would be a nomenclature whose naming rules specify document identifier categories (e.g., note-author role), allowable values for categories (e.g., intern, attending), and a syntax for combining them. Codification of the “unwritten” document-naming rules in use at our facilities resulted in the first draft of the DNN.

Once component categories were created, the next task was to enumerate the terms for each. Terms were generated in three ways. First, terms were extracted from relevant files in the sites' Veterans Information Systems Technology Architecture (VistA) information systems. Second, national standards from organizations such as X1232 were reviewed. Finally, terms were added during DNN creation at the two initial sites.

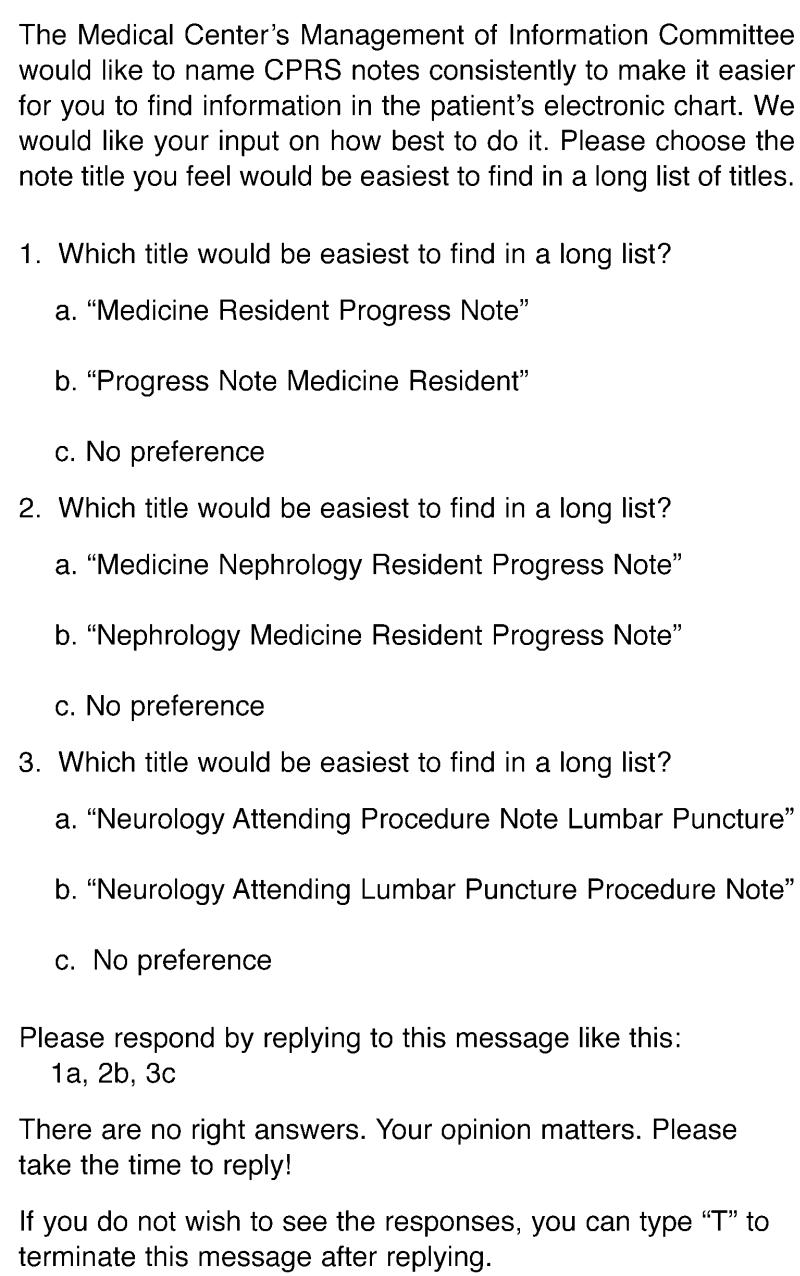

Rules for combining terms from each category into a document title were created. The issue of initial category sequence in a document title was addressed by conducting a user preference survey. A brief survey was sent by e-mail to all CPRS users at the Nashville VA Medical Center, asking for their preferences in three groups of choices. The survey was limited to a subset of possible combinations to encourage response. The survey questions and instructions are reproduced in Figure 2▶.

Figure 2.

User preference survey for note title format.

Software tools to support DNN review and use were created. To allow the DNN to be reviewed by a wider audience, a Microsoft Access title composition program was written. This software tool was extended with VistA-specific code to permit trained users to download and rename existing document titles automatically.

Study Design

Structure and Content Evaluation

To determine whether the DNN could be used beyond the initial two facilities, we evaluated its ability to model note titles at the Salt Lake City VA Medical Center, the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville. Electronic note titles from the Salt Lake City VA Medical Center and Vanderbilt University Medical Center and note title components from the Mayo Clinic were mapped by the authors into the structure and terminology of the DNN. The extent to which the DNN structure could accommodate the note title components from these sources was the primary outcome measure. Content completeness in each DNN category was a secondary outcome measure.

Usability Evaluation

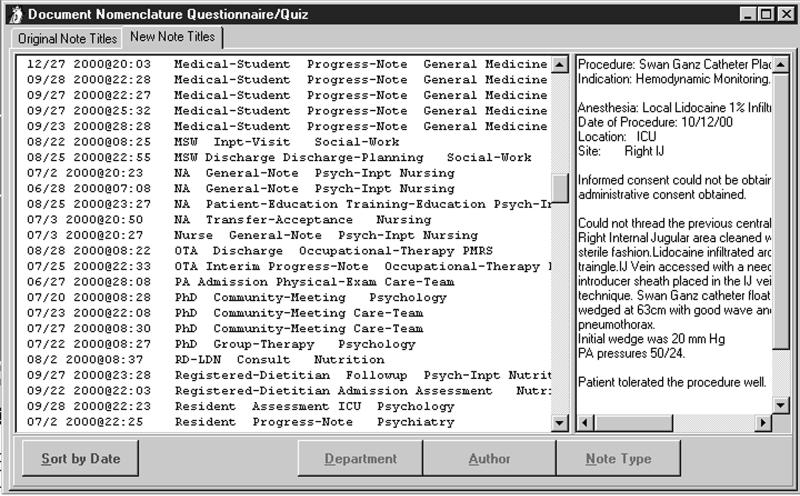

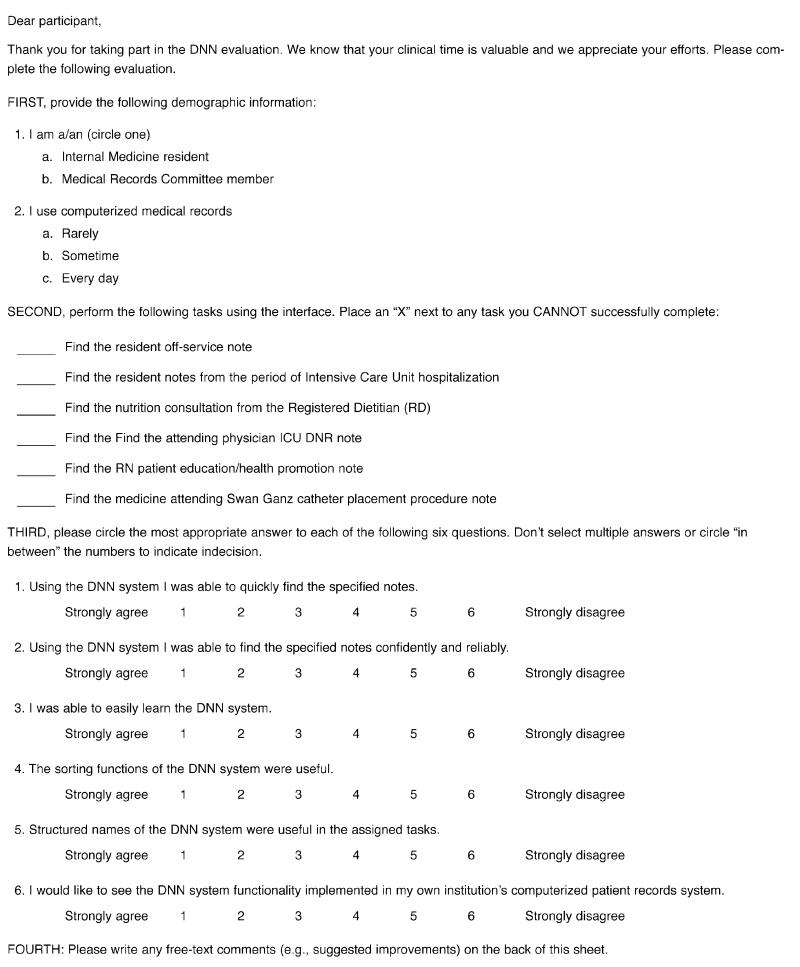

Progress notes for a single patient, covering multiple episodes of care, were re-titled using the DNN conventions. They were loaded into a Delphi application that could display them in reverse chronologic order or sort them according to author role, care unit, or event type (Figure 3▶). The usability test was done using two types of users—internal medicine residents and Medical Records Committee (MRC) members engaged in reviewing records for internal JCAHO and quality management activities.

Figure 3.

Title parsing and sorting application used in usability evaluation.

The users were not given any explicit training in use of the DNN system. Each user was timed while performing six exercises that involved finding specific notes (see Appendix▶). The exercises were chosen to represent common medical record review tasks based on the experience of the authors (who include two MRC chairs). After performing the tasks, the subjects answered six evaluation questions that assessed their perceptions of system effectiveness (Figure 4). Users could also offer comments. T-tests were used to assess whether each response varied significantly from the indifferent point (Likert answer mean 3 on a scale of 1 to 5). A two-way multivariate analysis of variance was used to compare responses of committee members and residents.

Appendix.

Usability Evaluation

Results

Initial Analysis of Document Titles

Note titles from Murfreesboro (n=566) and Nashville (n=593) were downloaded from VistA and analyzed. After normalizing case, punctuation, and spaces, there were 1,094 unique note titles between the two facilities.

Note titles typically included one or more descriptors of the people, places, things, or actions taking part in the medical event that was being documented. Common elements included characteristics of the note author, the care-giving organizational unit, and the event being documented (see Table 2▶). Title authors combined components in an inconsistent fashion with respect to the elements included and the order of inclusion (see sample raw titles in Table 1▶).

The Document-naming Nomenclature

DNN Information Categories

Table 3▶ summarizes DNN information categories derived from analysis of the document titles at the VA medical centers at Nashville and Murfreesboro.

Table 3.

▪ Overview of the Document-naming Nomenclature, Including Categories, Category Order, and Number of Terms Within Categories, after Analysis of Titles from Veterans Affairs Medical Centers at Nashville and Murfreesboro, Tennessee

| Default Order | Category | Examples | Terms in Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Care-providing Unit— Multidisciplinary Care Unit | Substance abuse, cardiac care | 42 |

| 3 | Care-providing Unit—Service | Medicine, Surgery, Social Work | 170 |

| 2 | Care-providing Unit—Section | Nephrology, ENT | 96 |

| 4 | Note Author Role | Attending physician, intern, medical student, registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, consultant | 126 |

| 6 | Event | Progress note, procedure note, admission note, assessment, plan, “do not resuscitate” note, family conference note, consult answer | 187 |

| 5 | Event Qualifier | Initial, follow-up, final procedure descriptor | 75 |

| 7 | Episode of Care | Integer | 0 |

Definitions and Examples

Multidisciplinary Care Unit: A care-providing organization composed of representatives from more than one service or section to address multiple facets of a clinical disorder or family of disorders. Examples: Substance Abuse, Cardiac Care.

Service: A high-level organizational unit distinguished by a unique academic and clinical focus and professional training. Examples: Medicine, Surgery, Social Work.

Section: A subunit of a major Service. A Section is distinguished by a more highly focused academic and clinical mission than a Service. Its members typically have completed additional training beyond that shared with other Service members. Examples: Nephrology, ENT.

Role: The part played by the note author in the event being documented. Examples: Attending, Intern, Medical Student, RN, LPN, Consultant.

Event: A health care “action” that requires documentation. Examples: Procedure, Admission, Assessment, Plan, DNR, Family Conference, Consult Answer.

Event Qualifier: A health care event modifier that makes the event more specific. Examples: Initial, Follow-up, Final, Swan Ganz Placement.

Episode of Care: A series of encounters directed toward the resolution or stabilization of a clinical problem.

Syntax: Rules for Document Name Composition

Names are created by concatenating terms from each category in the priority order indicated.

All categories do not need to be used.

The delimiter between categories is a single space (“ “).

If a class entry is to be blank, a delimiter should be entered.

Words composing a multiword term within a category should be separated by a dash (“–”) rather than a single space. A single space is reserved to be the delimiter between category terms.

User Preference for Component Order Within Composed Note Titles

Respondents to the e-mail survey at the Nashville VA Medical Center numbered 42. Tabulation of the responses to each of the survey questions follows.

- Question 1: Order of Event and Care Unit

- Care Unit First 24

- Event First 14

- No Preference 4

- Question 2: Order of Service and Section

- Service First 0

- Section First 36

- No Preference 6

- Question 3: Order of Event and Event Qualifier

- Event First 9

- Event Qualifier First 21

- No Preference 11

DNN Tools

Tools to support DNN review and implementation were created using Microsoft Access 97, Borland Delphi 4.0, and VistA Fileman routines. The Access database is used to manage the DNN and model free-text titles imported from VistA. The Delphi and Fileman components permit authorized VA users to load existing TIU titles into the Access-based tool automatically.

Evaluation of Mayo Clinic Note Titles

The Mayo Clinic uses a combination of dictated and handwritten notes. Dictated note titles are formulated by selecting a “Service” and an “Event” from approved lists. The Mayo medical record is organized by clinical care “episodes.” A care episode begins with the patient's first contact with the Mayo health care system. The episode remains open until the patient's problem has resolved or, in cases of chronic incurable disorders (such as diabetes mellitus), stabilized.

Ten Mayo event-types correspond structurally to DNN Events and Event Qualifiers. Forty-two Mayo “Services” correspond to DNN Multidisciplinary Care Units, Services, and Sections.

All Mayo dictated notes follow the DNN model because they are formed from a subset of that model.

Of the 42 Mayo “Services,” 18 were categorized as a DNN Multidisciplinary Care Unit, 25 were categorized as a DNN Service (department), and 21 were categorized as a DNN Section. Table 4▶ shows the content completeness of DNN for describing Mayo “Services” and Mayo “Events.” Eight of the ten major categories used at Mayo had exact representations in the DNN, as derived from data from the VA medical centers at Nashville and Murfreesboro. The two Mayo terms that lacked equivalents were “Conference” and “Miscellaneous.” Mayo terms that did not appear in the initial version of the DNN were subsequently added.

Table 4.

▪ Analysis of Note Titles from the Mayo Clinic, the Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC), and Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), and Their Coverage by the Initial Version of the Document-naming Nomenclature (DNN)

| Multidisciplinary Care Unit | Service | Section | Role | Event | Event Qualifier | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mayo Clinic dictated note titles with component | 18/42 (43%) | 25/42 (60%) | 21/42 (50%) | N/A* | 10/10* (100%) | 5/10 (50%) |

| DNN coverage | 1/18 (6%) | 23/25 (92%) | 12/21 (57%) | N/A | 8/10 (80%) | 2/5 (40%) |

| VUMC electronic note titles with component | 11/50 (22%) | 13/50 (26%) | 6/50 (12%) | 5/50 (10%) | 41/50 (82%) | 17/50 (34%) |

| DNN coverage | 0/11 (0%) | 10/13 (77%) | 2/6 (33%) | 5/5 (100%) | 39/41 (95%) | 10/17 (59%) |

| VUMC dictated note titles with component | 160/524 (31%) | 181/524 (35%) | 135/524 (26%) | 7/524 (1%) | 499/524 (95%) | 139/524 (28%) |

| DNN coverage | 18/160 (11%) | 163/181 (90%) | 46/135 (35%) | 7/7 (100%) | 403/499 (81%) | 81/139 (58%) |

| Salt Lake City VAMC CPRS note titles with component | 257/877 (29%) | 650/877 (74%) | 367/877 (42%) | 185/877 (22%) | 845/877 (96%) | 426/877 (49%) |

| DNN coverage | 46/257 (18%) | 609/650 (94%) | 291/367 (79%) | 179/185 (97%) | 798/845 (94%) | 206/426 (48%) |

Abbreviation: CPRS indicates the Veterans Affairs Computerized Patient Record System.

*See text.

Evaluation of Note Titles from the Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Medical Center

The Salt Lake City VA Medical Center uses the same nationally distributed VA software (e.g., CPRS, TIU, and VistA) as the Nashville and Murfreesboro medical centers. Local configuration is possible and in some instances required. For example, note titles and types are primarily locally defined.

The Salt Lake City VA Medical Center had 877 note titles. Of these, 864 (99 percent) could be completely modeled using the DNN structure. Of the remainder, 12 titles could be only partially modeled because they contained abbreviations that were incomprehensible to the authors. The last title was a test, and it was not used for medical documentation. The frequency of DNN components in these note titles and their coverage by the initial DNN term set are shown in Table 4▶.

Evaluation of Vanderbilt University Note Titles

Vanderbilt University Medical Center is in the process of deploying an electronic progress note system. At present, most notes are either dictated or handwritten into the medical record. Authors create titles for these notes without restriction. Note titles for the electronic note entry system are restricted to a controlled subset. Dictated note titles were analyzed separately from electronic note titles.

All 50 VUMC electronic note titles could be completely modeled using DNN. Eleven (22 percent) included Multidisciplinary Care Units, 13 (26 percent) included Services, 6 (12 percent) included Sections, 5 (10 percent) included Roles, 41 (82 percent) included Events, and 17 (34 percent) included Event Qualifiers.

The Vanderbilt MARS system33 is used to view online dictated documents. As of Oct 5, 2000, there were 1,874,677 notes online. Unique strings, representing dictated titles, numbered 2,721. This number is not adjusted to account for differences in case, spelling, or other lexical variants. We analyzed the 524 titles that were used ten or more times (accounting for 1,870,073 dictated documents).

The DNN structure fully modeled 507 of 524 titles (97 percent). Thirteen dictated note titles could not be modeled at all with the DNN structure. Of these, eight were indecipherable acronyms or non sequiturs, and five were digits (e.g., “88”). Four dictated note titles covered multiple events (e.g., admission note and operative note and death note) and could only be partially modeled. The DNN accurately modeled 507 of 511 (99.2 percent) comprehensible, non-numeric titles.

Redundant titles were common. For example, in the trauma service there were 27 unique titles for “progress notes” and 8 variations on “admission note” (excluding all those with additional components, such as an “admission” with “history and physical”). Event was present in 95 percent of titles, Service was present in 35 percent, Section was present in 26 percent, and role was present in 1 percent.

Table 4▶ shows components that were present in the Vanderbilt electronic and dictated note titles and their coverage by the DNN.

Usability Evaluation

Respondents included nine internal medicine residents and seven MRC members from the Salt Lake City VA Medical Center. Thirteen respondents were daily CPRS users. Each group's mean responses to Likert scale usability questions are shown in Table 5▶. In each case, responses were significantly better than indifferent (P<0.0002 for each). The mean time to complete the six tasks for the two groups was 4.9 min for residents and 4.0 min for MRC members. The difference in task time between the two groups was not significant (t=1.323, P=0.2071). A two-way (type of user: MRC committee member vs. resident) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) using task time as a covariate did not show any significant effects for the six dependent variables assessed in the Likert questionnaire. This indicates that residents and MRC members viewed the system in a similar light. Finally, the analysis showed no significant effects for the type-of-user x task-time interaction (F~1.0, P>0.05 in all cases).

Table 5.

▪ Mean and Standard Error of Questionnaire Responses

| Found Notes Quickly | Found Notes Confidently and Reliably | Easy to Learn | Sorting Functions Useful | Structured Names Useful | Want DNN Functions in Production System | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents (n=9) | 1.33±0.167 | 1.778±0.227 | 1.333±0.167 | 1.333±0.236 | 1.556±0.294 | 1.444±0.338 |

| MRC (n=7) | 1.429±0.202 | 1.286±0.184 | 1.143±0.143 | 1.286±0.184 | 1.1435±0.143 | 1.143±0.143 |

| Overall (n=16) | 1.375±0.125 | 1.562±0.157 | 1.250±0.112 | 1.312±0.151 | 1.375±0.180 | 1.312±0.198 |

Notes: The most favorable response possible was 1, a neutral response was 3, and the least favorable response possible was 5. All resident and MRC member results were highly significant (Student t-test, P<0.0002, assuming null hypothesis of indifference). For the six overall results, the t-test result was significant at P<0.0001.

Discussion

The structure of the DNN successfully modeled virtually all note titles at each participating institution. In order of decreasing frequency, each institution used health care event (80 to 96 percent), features of the care providing unit (~50 to 70 percent), and author role (~10 percent) in their note titles. The overlap of component types and their similar frequency of use at different institutions (Table 6▶) are interesting and useful findings of this report. The only substantive DNN structure failure relates to multiple event documentation within a single note. An example of this is a single note used to document an admission, operation, and death. This was very rare, and may be undesirable in any event.

Table 6.

▪ Comparison of Title Component Frequencies (%) among Participating Institutions

| Note Title Component | Initial VA (n=1,094) | Mayo | SLC VA (n=877) | VUMC Electronic Notes (n=50) | VUMC Dictated Notes (n=524) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role | 8 | NA | 22 | 10 | 1 |

| Care unit (any) | 70 | 100* | 89 | 52 | 63 |

| Multidisciplinary care unit | 7 | 43 | 29 | 22 | 31 |

| Service | 62 | 60 | 74 | 26 | 35 |

| Section | 33 | 50 | 42 | 12 | 26 |

| Event | 84 | 100* | 96 | 82 | 95 |

| Event qualifier | 41 | 50 | 49 | 34 | 27 |

Abbreviations: VA indicates Department of Veterans Affairs; SLC VA, the Salt Lake City VA Medical Center; VUMC, Vanderbilt University Medical Center; NA, not applicable.

* See text.

The quality of the initial DNN term content varied considerably by the axis addressed. For example, initial DNN content accurately described events (80 to 95 percent). Services (departments) were also well described (77 to 94 percent). Each role component from Vanderbilt was covered, as were 97 percent of roles used at Salt Lake City (Mayo electronic titles do not include roles). Sections, such as Nephrology, were covered only moderately well (33 to 79 percent), and multidisciplinary care units were poorly covered (0 to 18 percent). The initial DNN term set has subsequently been supplemented with unmatched terms from the evaluation institutions.

The DNN model is based on the observation that medical chart documentation describes “Events” in the process of care. An event may be a patient admission, the performance and interpretation of a study, a visit to an outpatient clinic, or any of a number of occurrences. Notes are written to document “what happened.” In this respect, the DNN is an extension of the work of Huff et al.34

Our decision to include author role in the DNN merits discussion. We are well aware that precise roles may be difficult to define consistently in all instances, especially if we use licensure to define role. License types and titles vary among states and countries. For example, in the United States, the classifications for mid-level providers vary from state to state: in Minnesota there are four categories of mid-level providers; in Utah, two. This variability makes creating a valid value set difficult and its maintenance even harder.

Finally, only 1 to 22 percent of unique note titles contained a reference to author role. We included author role for several reasons. First, it is more commonly used than an analysis of all unique titles might suggest. Of the 50 most commonly used note titles at the Nashville VA Medical Center, 9 included roles (Nurse, Intern, Resident, Attending, and Care Manager). Together, they accounted for 99,940 of 417,661 entries (24 percent). Second, we included author role to allow the note reader to assess the note's validity and quality. Most experienced chart users know that a note written by an attending physician and a note written by a third-year medical student are likely to vary significantly in terms of quality, quantity, and information content. Finally, academic institutions, wishing to bill for services, must clearly distinguish care provided by trainees from care and supervision provided by medical staff. Including role in the title makes this task much easier.

We excluded problem following considerable debate among the authors. Including problem would make the DNN more compatible with problem-oriented medical records. In addition, a number of TIU titles contain specific reference to problems. However, in practice, note titles containing problems were rarely used (most either 0 or 1 times). We were also unsure how to title notes that address multiple problems in a reproducible manner, given our stated title length restrictions. We remain open to discussion of this important issue.

Although the user survey regarding compositional order within the DNN was relatively small, the lop-sidedness of the results was noteworthy. In keeping with the indexing literature of the past,35 users preferred more specific concrete concepts to be presented first, such as event qualifier preceding event type and section preceding service. The survey included a limited number of category order combinations to encourage response. Results will be used to guide initial title presentation. However, since DNN titles are easily parsed and manipulated by software, user-specific preferences can be accommodated.

The usability test results indicate that the administrative and clinical users found the DNN-based title sorting and note review application to be easily learned as well as fast and reliable for accessing required medical records. The DNN title structure was found to be useful for assigned task completion. All users were able to locate each required note quickly and accurately. We anticipate that users would have been even quicker on a second or third patient example (there seemed to be a substantial learning curve during the usability exercise). The results on the Likert questionnaire indicate that both MRC members and residents strongly favored the DNN titles and the associated application. Participating users wanted this functionality implemented in their production systems. Finally, users' comments were uniformly positive, including such comments as these:

This is much quicker than the current system of retrieving notes!

Coding for professional fees [would be made] much easier by searching for attending notes… the VISN HIMS manager group would want this!

The present study has several important limitations. First, the authors evaluated the ability of the DNN to model titles only at the Vanderbilt, Mayo, and Salt Lake City medical centers. Second, the DNN was composed from titles from only two sites. It is possible that note titles may be different at other facilities in this country or abroad. Third, the usability evaluation was limited in scope. Finally, it could be argued that some or all DNN categories should be considered note metadata rather than title components.

The authors are aware of a parallel effort in Health Level 7 (HL7) to create a document ontology. At the time the DNN project started, no such effort existed in HL7. It is our intent to share all data and findings with HL7, to increase quality and contribute to consensus. Standards organizations represent the appropriate outlet for formalizing and distributing such efforts. Had such standards been available before the large-scale push for CPRS in VA, we would not have faced the note-finding difficulties described in the introduction to this article.

Conclusion and Next Steps

The DNN was created to help providers find desired clinical notes rapidly among hundreds of entries in the CPRS. It was created by formalizing the unwritten naming conventions discovered during manual review of 1,094 unique electronic progress note titles from two institutions. The DNN structure accurately models note titles at five medical centers. Preliminary usability evaluation indicates that information access is enhanced when the DNN is integrated with title parsing and sorting software.

Several additional steps should be taken. First, a mechanism integrating value sets from additional institutions should be created. This need is particularly important in the areas of multidisciplinary care units and organizational sections. Second, micro-ontologies should be created for each DNN axis. For example, a role ontology would allow better aggregation and retrieval of notes, authored by any type of nurse or physician. Third, effectiveness should be evaluated in a production environment. Finally, mechanisms should be put in place for the ongoing maintenance and free dissemination of the naming nomenclature. It is our hope that the HL7 organization will be the vehicle for this endeavor.

Currently, the VA has computerized virtually all clinical documents in 173 hospital units and 771 community-based outpatient clinics. As a result, patient records containing hundreds and even thousands of notes are becoming common. However, the current VA CPRS (version 14J) can display these notes only in reverse chronologic order. Finding a single important note (e.g., the DNR note) in this type of “haystack” when under considerable time pressure can be very difficult. The present results indicate that information access is enhanced when the DNN is integrated with title parsing and sorting software. We anticipate that future work to integrate the DNN functionality into the VA CPRS and perhaps the Mayo system would provide substantial and measurable patient care and provider benefits.

The large number of note titles from each VA medical center speaks to the success of the VA system-wide push to implement computer-based medical records. In addition to improving document selection in our facilities, we hope the DNN will promote our ability to transfer and incorporate documents from other facilities. Initially, demand for note transfer between VA medical centers could be addressed.

It is only because of the success of our predecessors in the field of computer-based records that we have had the opportunity to recognize and address this issue. We expect the need for a simple and useful DNN to grow in the future as other institutions bring their medical records “online.”

Appendix

Appendix: Usability Evaluation▶

This work was supported in part by grants R01-LM-05416097 and R01-LM-05416-06S1 from the National Library of Medicine.

References

- 1.Weed LL. Medical records, patient care, and medical education. Irish J Med Sci. 1964(June):271–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Weed LL. Medical records that guide and teach. N Engl J Med. 1968;278(11):593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weed LL. Medical records that guide and teach (concluded). N Engl J Med. 1968;278(12):652–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feinstein AR. The problems of the “problem-oriented medical record”. Ann Intern Med. 1973;78(5):751–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldfinger SE. The problem-oriented record: a critique from a believer. N Engl J Med. 1973;288(12):606–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnelly WJ, Brauner DJ. Why SOAP is bad for the medical record. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(3):481–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nightingale F. Notes on Hospitals. London, UK: Longmans, Green, 1863.

- 8.Tufo HM, Speidel JJ. Problems with medical records. Med Care. 1971;9(6):509–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnett GO. Computers in patient care. N Engl J Med. 1968;279(24):1321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenes RA, Barnett GO, Klein SW, Robbins A, Prior RE. Recording, retrieval and review of medical data by physician-computer interaction. N Engl J Med. 1970;282(6):307–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonald CJ, Tierney WM. Computer-stored medical records: their future role in medical practice. JAMA. 1988;259(23):3433–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dick RS, Steen EB (eds). The Computer-based Patient Record: An Essential Technology for Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1991. [PubMed]

- 13.Powsner SM, Wyatt JC, Wright P. Opportunities for and challenges of computerisation. Lancet. 1998;352(9140):1617–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shortliffe EH, Tang PC, Detmer DE. Patient records and computers [editorial]. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(12):979–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider EC, Riehl V, Courte-Wienecke S, Eddy DM, Sennett C. Enhancing performance measurement: NCQA's road map for a health information network. National Committee for Quality Assurance. JAMA. 1999;282(12):1184–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson CL, Meldrum KC. The VA computerized patient record: a first look. Proc 18th Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1994:1048. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Brown SH. No free lunch: institutional preparations for computer-based patient records. Proc AMIA Symp. 1999:486–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Payne TH. The transition to automated practitioner order entry in a teaching hospital: the VA Puget Sound experience. Proc AMIA Annu Symp. 1999:589–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Staggers N. The vision for the Department of Defense's computer-based patient record. Mil Med. 2000;165(3):180–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pryor TA, Gardner RM, Clayton PD, Warner HR. The HELP system. J Med Syst. 1983;7(2):87–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stead WW, Hammond WE, Straube MJ. A chartless record: Is it adequate? J Med Syst. 1983;7(2):103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnett GO. The application of computer-based medical-record systems in ambulatory practice. N Engl J Med. 1984;310(25):1643–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bleich HL, Beckley RF, Horowitz GL, et al. Clinical computing in a teaching hospital. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(12):756–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scherrer JR, Baud RH, Hochstrasser D, Ratib O. An integrated hospital information system in Geneva. MD Comput. 1990;7(2):81–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald CJ, Tierney WM, Overhage JM, Martin DK, Wilson GA. The Regenstrief Medical Record System: 20 years of experience in hospitals, clinics, and neighborhood health centers. MD Comput. 1992;9(4):206–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camp HN. Technical challenges, past and future, in implementing theresa: a one-million-patient, one-billion-item computer-based patient record and decision support system. In: Proceedings of the Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE) Conference on Health Care Information Infrastructure; Oct 23–24, 1995; Philadelphia Pa. 1995:83–6.

- 27.Kolodner RM, editor. Computerizing Large Integrated Health Networks: The VA Success. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1997.

- 28.Subcommittee 31.19 on Electronic Health Record Content and Structure, American Society for Testing and Materials. Standard Guide for Content and Structure of the Electronic Health Record. West Conshohocken, Pa.: ASTM, 1999. Publication E1384-99e1.

- 29.Subcommittee 31.19 on Electronic Health Record Content and Structure, American Society for Testing and Materials. Standard Specification for Coded Values Used in the Electronic Health Record. West Conshohocken, Pa.: ASTM, 2000. Publication E1633-00.

- 30.Rector AL. Thesauri and formal classifications: terminologies for people and machines. Methods Inf Med. 1998;37:501–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foskett DJ. The construction of a faceted classification for a special subject. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Scientific Information, 1958. Washington, DC: National Academy of Science, National Research Council,1958:867–88.

- 32.American National Standards Institute. Health Care Provider Taxonomy. Alexandria, Va.: ANSI, 1997. Publication X12N-TG2-WG15 ASC.

- 33.Giuse DA, Mickish A. Increasing the availability of the computerized patient record. AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1996:633–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Huff SM, Rocha RA, Bray B, Warner H, Haug PJ. An event model of medical information representation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1995;2(2):116–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ranganathan SR. Philosophy of Library Classification. Copenhagen, Denmark: Munksgaard, 1951.