Abstract

Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) (CD26) plays a critical role in the modulation and expression of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. We recently reported that sera from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus contained low levels of DPP IV and high titers of anti-DPP IV autoantibodies of the immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG classes and found a correlation between the low circulating levels of DPP IV and the high titers of anti-DPP IV autoantibodies of the IgA class. Since streptokinase (SK) is a potent immunogen and binds to DPP IV, we speculated that patients with autoimmune diseases showed higher DPP IV autoantibody levels than healthy controls as a consequence of an abnormal immune stimulation triggered by SK released during streptococcal infections. We assessed this hypothesis in a group of patients suffering from acute myocardial infarction, without a chronic autoimmune disease, who received SK as part of therapeutic thrombolysis. Concomitant with the appearance of anti-SK antibodies, these patients developed anti-DPP IV autoantibodies. These autoantibodies bind to DPP IV in the region which is also recognized by SK, suggesting that an SK-induced immune response is responsible for the appearance of DPP IV autoantibodies. Furthermore, we determined a correlation between high titers of DPP IV autoantibodies and an augmented clearance of the enzyme from the circulation. Serum levels of the inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) increased significantly after 30 days of SK administration, while the levels of soluble IL-2 receptor remained unchanged during the same period, suggesting a correlation between the lower levels of circulating DPP IV and higher levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in serum in these patients.

Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) (CD26) is a widely distributed, multifunctional, highly glycosylated membrane-bound ectoenzyme (10) that cleaves X-Pro dipeptides from the NH2 terminus of a number of proteins (31). Expression of DPP IV is highly associated with cell differentiation and activation, and it is involved in T-lymphocyte activation and migration across the extracellular matrix (1, 28). DPP IV is also found in human plasma (24), where its enzymatic activity is correlated with the activity of the enzyme in normal T lymphocytes (37). Not only are plasma DPP IV isoforms analogous to isoforms found in T lymphocytes (23), but they bind adenosine deaminase with similar specificity and affinity (21), suggesting that the plasma enzyme originates from T lymphocytes (22, 38).

Due to the key role that the membrane-bound DPP IV plays in T-cell-mediated immune responses and lymphokine synthesis (8), the enzyme has been studied in several autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In both RA and SLE there is a reduction in serum DPP IV activity (11, 29, 30, 41). In a recent report (6), we demonstrated that reduction of serum DPP IV activity in RA patients was due to hypersialylation of the enzyme, whereas in SLE patients a similar reduction in activity was possibly the result of increased clearance of DPP IV from circulation due to the high titers of circulating anti-DPP IV autoantibodies of the immunoglobulin A (IgA) class (6).

In previous studies we found that streptokinase (SK), a protein secreted by streptococci which facilitates the development of focal infection in association with plasminogen (Pg) of the host, can induce anti-Pg autoantibodies (16). We also demonstrated that SK binds to DPP IV expressed by rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts (17). Given these observations and since SK is a very potent immunogenic protein, we hypothesized that high titers of DPP IV autoantibodies in plasma in patients with autoimmune diseases could possibly result from immune stimulation by bacterial proteins such as SK. We assessed this hypothesis in a group of patients without chronic autoimmune disease who had suffered from acute myocardial infarction and had received SK as part of therapeutic thrombolysis.

We analyzed the expression and titers of anti-DPP IV antibodies in serum for 90 days after administration of SK and found that these autoantibodies bind preferentially to an epitope in DPP IV which is also recognized by SK. We also analyzed serum levels of the inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and soluble interleukin 2 receptor (IL-2 sRα), which are sensitive to DPP IV levels in the circulation (21). Since superantigens of bacterial origin have been postulated as participants in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease in humans (32), our data suggest a potential role for SK in these processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of both participating centers. After informed consent was obtained, a group of 10 patients who were treated with SK due to myocardial infarction during 1994 and 1995, at the University of Chile Clinical Hospital, were studied to assess the induction of anti-SK and anti-DPP IV autoantibodies. All of them were men, with a mean age of 47 years (age range, 39 to 72 years). Seven patients were chronic cigarette smokers. Three of the patients had arterial hypertension; two of them were being treated with atenolol and hydrochlorotiazide, and the third one was receiving enalapril. One of the patients had diabetes mellitus and was being treated with tolbutamide. None of them had a history of streptococcal infection during the 6 months previous to the acute myocardial infarction. They received thrombolytic therapy as a single intravenous dose of 1.5 × 106 U of SK. All patients received aspirin, 250 mg/day, after administration of SK. Analyses of the levels of anti-DPP IV IgA, IgG, or IgM were performed with serum samples collected immediately before administration of SK. Additional serum samples were collected at 10, 30, and 90 days after administration of the thrombolytic agent. None of the patients had a prior history of connective tissue disease or suffered from preexisting lymphoproliferative diseases. No one developed arthritis or any signs of connective tissue disease during the 2 years following SK administration.

Peptides.

The octapeptides LTSRPAHG and its randomized sequence APHLSTGR were purchased from Multiple Peptide Systems, San Diego, Calif.

Proteins.

DPP IV from a pool of human plasma (2 liters) was isolated by sequential purification using DEAE-Sepharose ion-exchange chromatography, Gly-Leu affinity chromatography, and gel filtration over Sephacryl S-200 as described by Shibuya-Saruta et al. (38), followed by affinity chromatography on immobilized adenosine deaminase as described by De Meester et al. (7), with an overall yield of 60% over that from serum. Calf intestinal mucosa adenosine deaminase was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.

Enzyme assays.

DPP IV activity was measured in 96-well culture plates using Gly-Pro-p-nitroanilide (0.2 mM) as the substrate in reaction mixtures (200 μl) containing serum samples (40 μl) and 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The hydrolysis of the substrate was monitored at a wavelength of 405 nm using an Anthos Labtec kinetic plate reader. Activity was expressed as ΔA405/min. Specific activity was calculated using a molar extinction coefficient of 8,800 M−1 cm−1 for p-nitroanilide at 405 nm (9) and a molecular mass of 220,000 Da for DPP IV. All experiments were done in triplicate unless otherwise specified.

Antibodies.

Antibodies to purified DPP IV from human serum were prepared in rabbits according to standard protocols (19). The polyclonal anti-DPP IV IgG was purified by affinity chromatography on protein A-Sepharose (13) followed by immunoadsorption to DPP IV coupled to Sepharose 4B. The monoclonal anti-DPP IV IgG, IOA26-clone BA5, was purchased from AMAC, Inc. (Westbrook, Maine). Human IgG Fc fragment and goat affinity-purified F(ab′)2 fragments against human IgA, IgG, and IgM were purchased from ICN Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Aurora, Ohio). Secondary antibodies to human IgA, IgG, and IgM were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. Human anti-DPP IV IgA was purified from patient sera by chromatography on Jacalin-Sepharose (33) followed by immunoadsorption to DPP IV coupled to Sepharose 4B. Human anti-DPP IV IgG was purified from patient sera by chromatography on protein A-Sepharose (13) followed by immunoadsorption to DPP IV coupled to Sepharose 4B. Human anti-DPP IV IgM was purified from patient sera by ion-exchange chromatography on maltose binding protein-Sepharose (35), followed by immunoadsorption to DPP IV coupled to Sepharose 4B.

ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were performed in 96-well culture plates. Quantification of anti-SK antibodies was performed in 96-well culture plates coated with SK as previously described (15). For quantification of DPP IV, plates were coated first with 200 μl of a solution containing 5 μg of an anti-DPP IV monoclonal antibody (MAb) (IOA26-clone BA5) per ml in 0.1 M Na2CO3 and incubated overnight at 4°C. The MAb anti-DPP IV (clone BA5) is well characterized and has been used for immunoprecipitations and Western blot analyses of full-length DPP IV (20). After coating, plates were rinsed with 200 μl of 10 mM sodium phosphate-0.1 M NaCl (pH 7.4) containing 0.05 Tween 80 (PBS-Tween) to remove unbound protein. Nonspecific sites were blocked by incubating with PBS-Tween containing 2% bovine serum albumin (PBS-Tween-2% BSA) at room temperature for 1 h. Plates were washed again with PBS-Tween, air dried, and stored at 4°C. For assays, increasing concentrations of sera were added in triplicate in a 200-μl final volume of PBS-Tween-2% BSA and incubated al 37°C for 2 h, followed by rinsing with PBS-Tween and incubation with an affinity-purified polyclonal anti-DPP IV rabbit IgG (100 ng/well) at 37°C for 1 h. Plates were then washed with PBS-Tween and 200 μl of alkaline phosphatase substrate (1-mg/ml p-nitrophenylphosphate) in 0.1 M glycine-1 mM MgCl2-1 mM ZnCl2 (pH 10.4), was added to the plate, and absorbance was monitored at a wavelength of 405 nm using an Anthos Labtec Kinetic Plate reader. Bound DPP IV was expressed as ΔA405/min. Concentrations of DPP IV were calculated from a calibration curve constructed with affinity-purified DPP IV. The concentrations of anti-DPP IV IgA, IgG, and IgM in sera of patients were determined by ELISA using 96-well culture plates coated with DPP IV. Provisions were made to avoid reactivity of specific DPP IV autoantibodies with rheumatoid factors. Plates were incubated with serum samples (1:200 dilution) in the presence of IgG Fc fragments (1 μg/ml) at 37°C for 2 h, rinsed extensively with PBS-Tween, and finally incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-human IgA, IgG, and IgM F(ab′)2 fragments at 37°C for 1 h, and the concentrations of bound immunoglobulins were calculated from calibration curves expressing the rate of hydrolysis of the alkaline phosphatase substrate p-nitrophenylphosphate (ΔA405/min) versus the concentration of pure immunoglobulins of the three classes. The total concentration of these immunoglobulins in patient sera was determined by ELISA in 96-well culture plates coated with F(ab′)2 specific anti-human IgA, IgG, and IgM. After incubation of sera in the presence of Fc fragments (1 μg/ml) to avoid cross-reactivity of immunoglobulins, the plates were rinsed with PBS-Tween and incubated with Fc-specific alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-human IgA, IgG, and IgM F(ab′)2 fragments. Bound antibodies were measured as described above and expressed as ΔA405/min. Final concentrations were calculated from calibration curves constructed with pure human IgA, IgG, and IgM. For peptide competition experiments, plates coated with DPP IV were first incubated with increasing concentrations of the octapeptides LTSRPAHG or its randomized sequence APHLSTGR in PBS-Tween-2% BSA and incubated for 1 h at 37°C before addition of a single concentration (100 ng/well) of anti-DPP IV autoantibodies. Concentrations of bound antibodies were determined as described above.

Serum cytokinase assays.

Concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-2 sRα in serum were determined by quantitative sandwich ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) according to manufacturer's instructions. Analyses of assay reproducibility showed intra-assay coefficients of variation for TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-2 sRα equal to or less than 4.2, 2.0, and 4.6%, respectively, while interassay coefficients of variation were equal to or less than 3.8, 2.6, and 1.8%, respectively.

Statistics.

The statistical significance of differences between the variables serum DPP IV levels, cytokine levels, and basal levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM antibodies against DPP IV was evaluated by means of Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance. The specific post hoc comparisons within each group of variables was performed by means of the Mann-Whitney U test. The changes between the baseline IgG, IgA, and IgM antibody levels among the SK-treated patients and levels at 30, 60, and 90 days' time was evaluated by means of the Friedman analysis of variance test.

RESULTS

Anti-SK antibody levels in patients who received SK therapeutically.

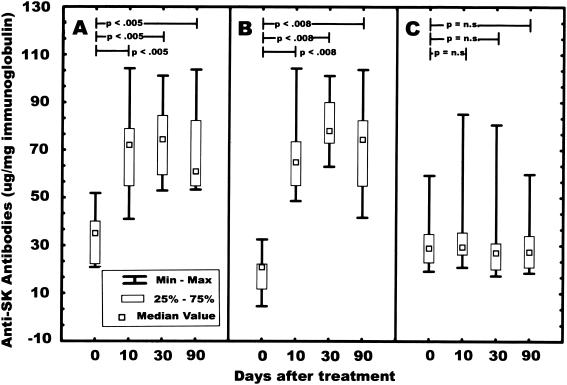

Analysis of anti-SK IgA, IgG, and IgM levels (Fig. 1) shows that IgA and IgG titers peaked 30 days after administration of SK, followed by a slow decrease up to 90 days after the infusion of the thrombolytic agent. There were statistically significant differences between the IgA baseline levels and those at 10, 30, and 90 days (medians, 34.99, 72.02, 74.41, and 60.98 μg of anti-SK IgA/mg of IgA, respectively; P < 0.0003 overall and P < 0.005 for each comparison). The differences between the baseline IgG anti-SK antibodies and those at 10, 30 and 90 days were also statistically significant (medians, 20.86, 64.83, 78.04, and 74.38 μg of anti-SK IgG/mg of IgG, respectively; P < 0.0002 overall, and P < 0.008 for each comparison). No statistically significant differences between baseline and 10, 30, and 90 days were observed for IgM anti-SK autoantibodies (medians, 28.88, 29.37, 26.99, and 27.32 μg of IgM/mg, respectively).

FIG. 1.

Levels of anti-SK antibodies in serum from patients (n = 10) who received SK therapeutically. Serum samples (1:500 dilution) in 0.2 ml of PBS-Tween were added separately to 96-well microtiter plates coated with SK and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Anti-SK IgA titers; (B) anti-SK IgG titers; (C) anti-SK IgM titers. n.s., not significant.

Anti-DPP IV autoantibodies levels in patients who received SK therapeutically.

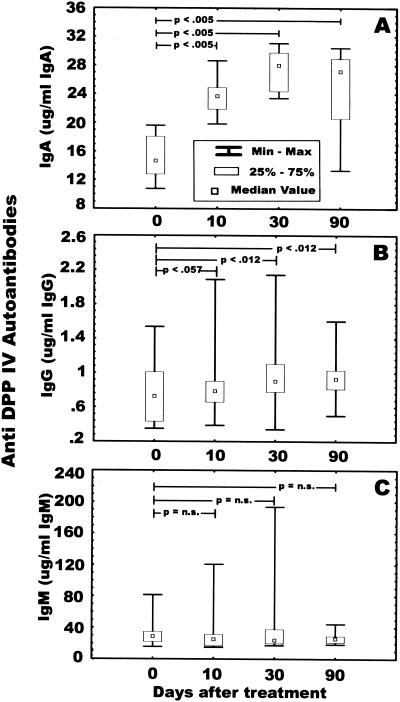

Concomitant with the increase of anti-SK IgA and IgG in serum, we observed a statistically significant increase of anti-DPP IV IgA from the baseline to 10, 30, and 90 days after SK administration (median concentrations in serum, 14.76, 24.34, 27.97, and 27.13 μg of anti-DPPV IV IgA/mg of IgA respectively; P < 0.0002 overall and P < 0015 for all comparisons) (Fig. 2A). Anti-DPP IV autoantibodies of the IgG class were also increased 10 days after SK administration, reaching statistically significant levels at 30 and 90 days after SK administration (median concentrations in serum, 0.72, 0.78, 0.90, and 0.93 μg of anti-DPP IV IgG/mg of IgG, respectively; P < 004 overall; P < 0.057 at 10 days; P < 0.012 at 30 and 90 days) (Fig. 2B). No statistically significant increase in DPP IV autoantibodies of the IgM class was found over time (median concentration in serum, 28.87, 25.45, 24.03, and 25.96 μg of anti-DPP IV IgM/mg of IgM, respectively) (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Analysis of anti-DPP IV autoantibodies from patients (n = 10) who received SK therapeutically. Serum samples (1:500 dilution) in 0.2 ml of PBS-Tween were added separately to 96-well plates coated with DPP IV and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Anti-DPP IV IgA titers; (B) anti-DPP IV IgG titers; (C) anti-DPP IV IgM titers. n.s., not significant.

DPP IV levels and activity over time in sera of patients who received SK therapeutically.

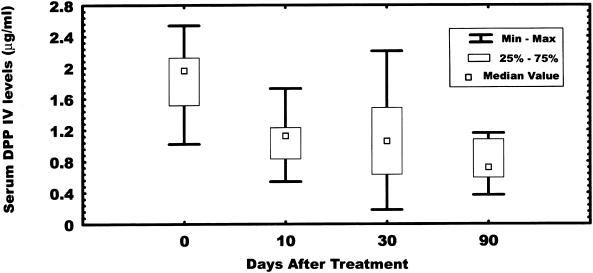

The median serum DPP IV levels from a group of patients (n = 10) who received SK therapeutically (Fig. 3) show a continuous decrease in the enzyme concentration between 0 and 90 days after SK administration (1.9, 1.12, 1.12, and 0.80 μg/ml at 0, 10, 30, and 90 days, respectively). The difference between 0 and 90 days is statistically significant (P < 0.0042). However, measurements of DPP IV enzymatic activity during the same period (data not shown) show no statistically significant changes.

FIG. 3.

Levels of DPP IV in serum from patients (n = 10) who received SK therapeutically. Serum samples (40 μl) in 0.2 ml of PBS-Tween were added to 96-well plates coated with an anti-DPP IV MAb and incubated for 2 h at 37°C as described in Materials and Methods. The plates were washed with PBS-Tween and incubated with a polyclonal anti-DPP IV IgG for 1 h at 37°C, followed by incubation with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated protein A for 30 min. Bound DPP IV was detected by monitoring the hydrolysis of the alkaline phosphatase substrate p-nitrophenylphosphate at a wavelength of 405 nm.

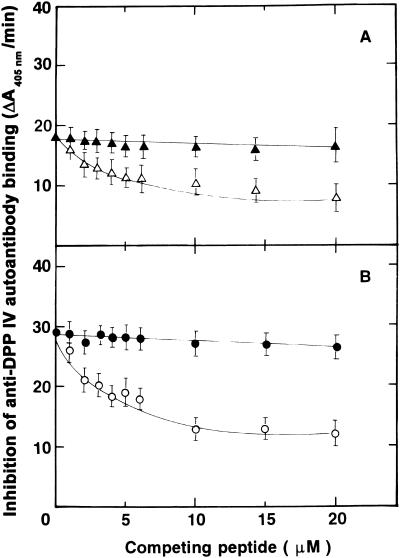

Binding specificity of anti-DPP IV autoantibodies.

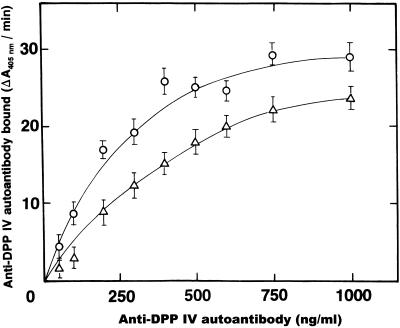

SK binds to DPP IV via the LTSRPA amino acid sequence (17). Therefore, if interactions with SK are involved in the mechanisms responsible for the production of anti-DPP IV autoantibodies, either SK or the LTSRPA peptide should be able to interfere with autoantibody binding to DPP IV. A series of ELISA experiments was carried out to establish the binding specificity of the anti-DPP IV autoantibodies. Plates coated with DPP IV were incubated with a single aliquot (5 μl), in triplicate, from each SK-treated patient in the presence of increasing concentrations of the octapeptide LTSRPAHG or its randomized sequence APHLSTGR. The concentrations of anti-DPP IV autoantibodies of the IgA and IgG classes bound under these conditions were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Since the inhibition curves were similar for all the sera tested (data not shown), we purified anti-DPP IV IgA and IgG from one serum with the highest titers. Both purified anti-DPP IV antibodies react with the immobilized antigen in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4). Incubation of DPP IV plates with a single concentration of either IgA (Fig. 5A) or IgG (Fig. 5B) anti-DPP IV autoantibody (500 ng/ml) in the presence of increasing concentrations of the peptide LTSRPAHG, inhibited binding of both classes of autoantibodies, whereas its randomized sequence APHLSTGR produced no effect.

FIG. 4.

Binding of anti-DPP IV autoantibodies to immobilized DPP IV. Increasing concentrations of purified anti-DPP IV IgA (▵) or IgG (○) autoantibodies in PBS-Tween (200 μl/well) were added to 96-well plates coated with DPP IV and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The plates were rinsed twice with PBS-Tween followed by a 1-h incubation at 37°C with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-IgA or anti-IgG secondary antibodies. Binding was detected by monitoring the hydrolysis of the alkaline phosphatase substrate p-nitrophenylphosphate at 405 nm. Error bars, standard deviations.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of autoantibody binding to DPP IV by a peptide structurally homologous to the SK binding region to DPP IV. Ninety-six-well plates coated with DPP IV were incubated with increasing concentrations of the octapeptide LTSRPAHG or APHLSTGR in PBS-Tween for 1 h at 37°C. At this time, a single concentration (500 ng/ml) of IgA or IgG was added to the wells and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Excess reagents were removed by rinsing the plates with PBS-Tween, and bound autoantibodies were detected with specific alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-IgA or anti-IgG secondary antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Inhibition of IgA autoantibody binding to DPP IV in the presence of increasing concentrations of LTSRPAHG (▵) or its randomized sequence APHLSTGR (▴). (B) Inhibition of IgG autoantibody binding to DPP IV in the presence of increasing concentrations of LTSRPAHG (○) or its randomized sequence (•). Error bars, standard deviations.

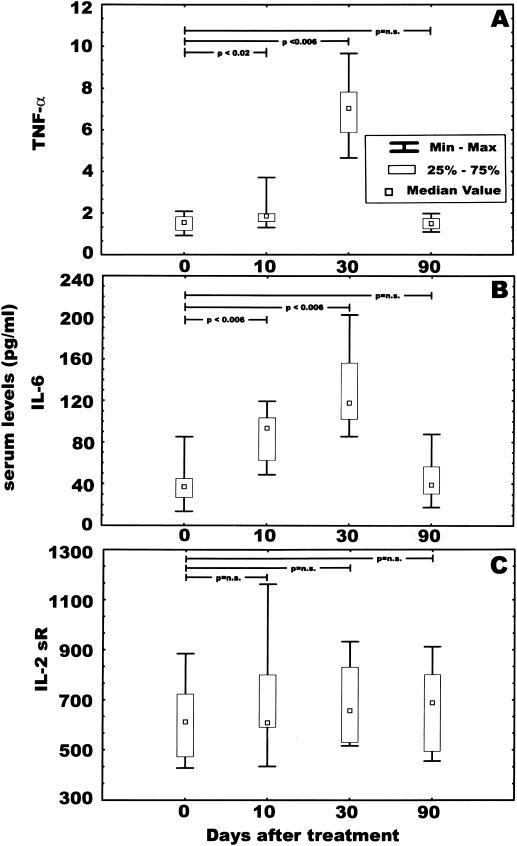

Serum cytokine levels.

Analyses of levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-2 sRα in serum after SK administration (Fig. 6A) show that TNF-α increased from a median of 1.55 pg/ml at baseline to 1.86 pg/ml at 10 days and 7.04 pg/ml at 30 days, returning to near baseline (1.50 pg/ml) at 90 days after SK administration. With regard to serum IL-6 levels (Fig. 6B), their medians also increased from 36.91 pg/ml at baseline to 93.57 and 117.80 pg/ml at 10 and 30 days after SK administration, respectively. The median serum IL-6 levels returned close to baseline (38.86 pg/ml) at 90 days. For both these cytokines, the differences between their levels at baseline and 10 and 30 days post-SK administration were statistically significant, with a P of <0.02 and <0.006 for TNF-α at 10 and 30 days, respectively, and a P of <0.006 and <0.006 for TNF-α at10 and 30 days, respectively. The median IL-2 sRα levels in serum changed from 610.68 pg/ml at baseline to 694.84, 676.41, and 655.03 pg/ml at 10, 30, and 90 days after SK administration, respectively (Fig. 6C). None of these differences were statistically significant.

FIG. 6.

Analyses of levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-2 sRα in serum. The concentrations of the three cytokines in serum samples (n = 10) from patients who received SK therapeutically were determined by an ELISA method as described in Materials and Methods. (A) TNF-α titers; (B) IL-6 titers; (C) IL-2 sRα titers. n.s., not significant.

DISCUSSION

In addition to its multiple roles in the expression or modulation of autoimmune and inflammatory responses (29), DPP IV functions as a receptor for both Pg (14) and SK (17). In a previous study (16), we found evidence suggesting that high titers of anti-Pg autoantibodies in sera from patients with RA and SLE may be the result of associations between SK (liberated during streptococcal infections) and Pg of the host (16). Recently, we reported the presence of anti-DPP IV autoantibodies in sera of patients with several autoimmune disorders (6). Since we found a correlation between appearance of Pg autoantibodies and anti-SK antibodies in SK-treated patients (16) and taking into consideration that SK associates with DPP IV (17), we investigated whether similar correlations existed in the appearance of anti-DPP IV autoantibodies in patients who received SK as a thrombolytic agent. This study shows a correlation between the appearance of anti-SK antibodies and anti-DPP IV autoantibodies of the IgA class during the same period. Inhibition of binding of these antibodies to DPP IV by the peptide LTSRPAH, an octapeptide containing the SK region responsible for binding to DPP IV (17), suggests SK as a promoter in the production of these autoantibodies. Although the specific activity of DPP IV in these patients was not changed over time, there is a continuous reduction in the concentration of circulating DPP IV, suggesting that the increase in levels of IgA autoantibodies may play a role in the augmented clearance of the enzyme from circulation. Levels of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 in serum were significantly elevated after 30 days of SK administration, while the levels of IL-2 sRα remained unchanged during the same period, suggesting a correlation between the lower levels of circulating DPP IV and high levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in these patients.

Newly synthesized DPP IV is cleared from circulation by the liver basolateral endosomes in association with polymeric IgA receptors, responsible for the transportation of IgA to bile, via a joint transcytotic process (2). This process has been also suggested as a major mechanism to clear harmful antigens from the circulation in the form of IgA-antigen complexes via bile secretion (4) and clears both the polymeric IgA receptors and the DPP IV together with the same kinetics (2). In this context, we should mention that SK is also rapidly removed from the circulation via secretion into the bile (5).

Our study also demonstrates that the IgA class antibody response against SK and DPP IV persists for at least 90 days after thrombolytic therapy with SK. Taking into consideration the short half-life of IgA in circulation, these findings suggest that SK persists for long periods in the host tissues, although it is not clear whether it remains intact or degraded. It has been postulated that a significant elevation of IgA antibody titers may result from enterobacterial antigenic stimulation via the gastrointestinal tract (39). In our study, intravenous administration of SK, without any evidence of mucosal participation, produced a predominant IgA anti-DPP IV response, thereby suggesting that high IgA circulating levels do not necessarily involve the gut as the site of infection. In this regard, it may be noteworthy that a large proportion of autoantibodies developed against plasma proteins after SK administration appear to be of IgA class. Proteins like Pg (16) and lactate dehydrogenase M (33) have in common their reactivity with SK. Most streptococcal infections of humans occur at skin or mucosal surfaces without causing bacteremia. Therefore, if the original immunogenic stimulus by streptococci is at a mucosal surface, the humoral immune response is primarily IgA.

The role of DPP IV in immune function is very complex. In some experimental models, such as adjuvant-induced arthritis (41) specific inhibition of DPP IV activity suppresses disease expression, pointing to a role for DPP IV activity in the pathogenesis of experimentally induced arthritis. However, in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts (17), SK binds to DPP IV and induces an increase in intracellular calcium independently of DPP IV enzymatic activity, thereby suggesting that its role in the pathogenesis of arthritis is not confined to only its enzymatic activity. DPP IV also has a key regulatory role in the metabolism of peptide hormones involved in psychoneuroendocrine, nutrition, and immune functions (21). Therefore, an increase in the clearance rate of circulating DPP IV may have either negative or positive pathogenic implications. For example, since DPP IV inactivates TNF-α (3), lower levels of DPP IV may increase bioactive levels of this cytokine in the circulation, thereby promoting TNF-α-induced tissue damage (21). Conversely, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, reduced levels of circulating DPP IV lead to increased levels of bioactive glucagon-like peptide-2, facilitating enhanced repair of the intestinal mucosal epithelium in vivo (46).

Although SK administration induced anti-DPP IV autoantibodies and higher circulating levels of TNF-α and IL-6, none of these patients developed an autoimmune disease at the beginning or during 2 years after the thrombolytic therapy with SK. Work by other investigators (40) shows that myocardial infarction patients have high titers of anti-SK antibody up to 90 months after SK administration, but their immune functions were similar to those of the general population. Based on the experimental and clinical data available, the apparently contradictory effects on the immune system may be explained by a bimodal action of DPP IV in immune function; immune reactions that have been initiated by other mechanisms are supported by DPP IV enzymatic activity, while other immune reactions are rather reduced, thus focusing the immunosurveillance on processes that are already under way (21).

A direct participation of bacterial components in the onset of arthritis has been reported, but the mechanisms involved are unclear (18, 25, 26, 36, 43, 45). It appears that exposure to a single isolated bacterial peptide is insufficient to trigger an autoimmune disease. Other factors such as up-regulation of the immunostimulatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, or IL-1 by microbial entry into phagocytic cells (44); a distinct genetic profile between streptococcal strains (12); or autoimmune genetic susceptibility of the host (25) may also be necessary for this process.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institutes Grant HL-24066.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ansorge, S., F. Bühling, T. Hoffman, T. Kähne, K. Neubert, and D. Reinhold. 1995. DPP IV/CD26 on human lymphocytes: functional roles in cell growth and cytokine regulation, p. 163-184. In B. Fleischer (ed.), Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) in metabolism and the immune response. Springer, New York, N.Y.

- 2.Barr, V. A., L. J. Scott, and A. L. Hubbard. 1995. Immunoadsorption of hepatic vesicles carrying newly synthesized dipeptidyl peptidase IV and polymeric IgA receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 270:27834-27844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauvois, B., J. Sanceau, and J. Wietzerbin. 1992. Human U937 cell surface peptidase activities: characterization and degradative effect on tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:923-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, W. R., and T. M. Kloppel. 1989. The liver and IgA: immunological, cell biological, and clinical implications. Hepatology 9:763-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brucato, F. H., and S. V. Pizzo. 1990. Catabolism of streptokinase and polyethylene glycol-streptokinase: evidence for transport of intact forms through the biliary system in the mouse. Blood 76:73-79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuchacovich, M., H. Gatica, H., S. V. Pizzo, and M. Gonzalez-Gronow. 2001. Characterization of human serum dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD 26) and analysis of its autoantibodies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 19: 673-680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeMeester, I., G. Vanhoof, A. M. Lambeir, and S. Scharpé. 1996. Use of immobilized adenosine deaminase for the rapid purification of native human CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J. Immunol. Methods 189:99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeMeester, I., G. Vanhoof, D. Hendriks, H. Demuth, A. Yaron, and S. Scharpé. 1992. Characterization of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) from human lymphocytes. Clin. Chim. Acta 210:23-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erlanger, B. F., N. Kokowsky, and W. Cohen. 1961. The preparation of two new chromogenic substrates of trypsin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 95:271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleischer, B. 1994. CD26: a surface protein involved in T cell activation. Immunol. Today 15:180-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujita, K., M. Hirano, J. Ochiai, M. Funabashi, I. Nagatsu, T. Nagastsu, and S. Sakakibara. 1978. Serum glycylproline p-nitroanilidase activity in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Chim. Acta 88:15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuller, F., D. Bast, V. Nizet, D. Low, and J. de Azavedo. 2001. Streptococcus initial virulence is associated with a distinct genetic profile. Infect. Immun. 69:1994-2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goding, J. W. 1978. Use of staphylococcal protein A as an immunological reagent. J. Immunol. Methods 20:241-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez-Gronow, M., G. Gawdi, and S. V. Pizzo. 1994. Characterization of the plasminogen receptors of normal and rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 269:4360-4366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Gronow, M., J. J. Enghild, and S. V. Pizzo. 1993. Streptokinase and human fibronectin share a common epitope: implications for regulation of fibrinolysis and rheumatoid arthritis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1180:283-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Gronow, M., M. Cuchacovich, D. M. Grigg, and S. V. Pizzo. 1996. Analysis of autoantibodies to plasminogen in the serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Mol. Med. 74:463-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Gronow, M., M. R. Weber, G. Gawdi, and S. V. Pizzo. 1998. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) is a receptor for streptokinase on rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Fibrinol. Proteol. 12:129-135. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granfors, K., S. Jalkanen, A. Lindberg, O., Maki-Ikola, R. Von Essen, R. Lahesmaa-Rantala, H. Isomaki, R. Saario, W. J. Arnold, and A. Toivanen. 1990. Salmonella lipopolysaccharide in synovial cells from patients with reactive arthritis. Lancet 335:685-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harlow, E., and D. Lane (ed.). 1988. Antibodies: a laboratory manual, p. 98—108. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 20.Hegen, H. 1998. CD26 workshop panel report, p. 478-489. In T. Kishimoto, H. Kikutani, et al. (ed.), Leucocyte typing VI. White cell differentiation antigens. Garland Publishing, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 21.Hildrebrandt, M., W. Reutter, P. Arck, M. Rose, and B. Klapp. 2000. A guardian angel: the involvement of dipeptidyl peptidase IV in psychoneuroendocrine function, nutrition and immune defense. Clin. Sci. 99:93-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kameoka, J., T. Tanaka, Y. Nojima, S. F. Schlossman, and C. Morimoto. 1993. Direct association of adenosine deaminase with a T cell activation antigen, CD26. Science 261:466-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasahara, Y., G. Leroux-Roeslm, R. Majamura, and F. Chisari. 1984. Glycylprolyl-diaminopeptidase in human leukocytes: selective occurrence in T lymphocytes and influence on the total serum enzyme activity. Clin. Chim. Acta 139:295-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasahara, Y., N. Fuji, M. Mizukoshi, and T. Nagatsu. 1983. Multiple forms of glycylprolyl dipeptidylaminopeptidase in serum and tissues. Japanese J. Clin. Chem. 12:89-93. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirveskari, J., Q. He, M. Leirisalo-Repo, O. Maki-Ikola, M. Wuorella, A. Putto-Laurila, and K. Granfors. 1999. Enterobacterial infection modulates major histocompatibility complex class I expression on mononuclear cells. Immunology 97:420-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maki-Ikola, O., U. Yli-Kerttula, U. Saario, P. Toivanen, and K. Granfors. 1992. Salmonella specific antibodies in serum and synovial fluid in patients with reactive arthritis. Br. J. Rheumatol. 31:25-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maki-Ikola, O., R. Lahesmaa, J. Heeseman, R. Merilahti-Palo, R. Saario, A. Toivanen, and K. Granfors. 1994. Yersinia-specific antibodies in serum and synovial fluid in patients with Yersinia triggered reactive arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 53:535-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morimoto, C., and S. F. Schlossman. 1994. CD26—a key costimulatory molecule in CD4 memory T cells. Immunologist 2:4-7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muscat, C., A. Bertotto, E. Agea, O. Bistoni, R. Ercolani, R. Tognelli, F. Spinozzi, M. Cesarotti, and R. Gerli. 1994. Expression and functional role of 1F7 (CD26) antigen on peripheral blood and synovial fluid cells in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 98:252-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakao, H., K. Eguchi, A. Kawakami, K. Migita, T. Otsubo, Y. Ueki, C. Shimomura, H. Tezuka, M. Matsunaga, K. Maeda, and S. Nagataki. 1989. Increment of Tal positive cells in peripheral blood from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 16:904-910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neurath, H. 1986. The versatility of proteolytic enzymes. J. Cell Biochem. 32:35-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paliard, X., S. G. West, J. A. Lafferty, J. R. Clements, J. W. Kappler, P. Marrack, and B. L. Kotzin. 1991. Evidence for the effects of a superantigen in rheumatoid arthritis. Science 253:325-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Podlasek, S. J., D. R. Dufour, and R. A. McPherson. 1989. Alterations in lactate dehydrogenase isoenzyme patterns after therapy with streptokinase or streptococcal infection. Clin. Chem. 35:1763-1766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roque-Barreira, M. C., and A. Campos-Neto. 1985. Jacalin: an IgA-binding lectin. J. Immunol. 134:1740-1743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothman, S., M. Gantry, R. Gawne, A. Dobek, R. Ogert, M. J. Stone, and P. Strickler. 1989. Purification of mouse monoclonal immunoglobulin M by ion-exchange chromatography. J. Liquid Chromatogr. 12:1935-1947. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salmi, M., K. Granfors, Leirisalo-Repo M, M. Hanalainen, R. MacDermott, R. Laino, T. Havia, and S. Jalkanen. 1992. Selective endothelial binding of interleukin-2-dependent human T-cell lines derived from different tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:11436-11440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schön, E., A. Ittenson, K. Klemm, and S. Ansorge. 1984. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV and a-naphtylacetate esterase in human T-lymphocytes: cytochemical and biochemical investigations. Acta Histochem. 75:175-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shibuya-Saruta, H., Y. Kasahara, and Y. Hashimoto. 1996. Human serum dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) and its unique properties. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 10:435-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shodjai-Moradi, F., A. Ebringer, and I. Abuljadayel. 1992. IgA antibody response to klebsiella in ankylosing spondylitis measured by immunoblotting. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 51:233-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Squire, I. B., W. Lawley, S. Fletcher, E. Holme, W. S. Hillis, C. Hewitt, and K. L. Woods. 1999. Humoral and cellular immune responses up to 7.5 years after administration of streptokinase for acute myocardial infarction. E. Heart J. 20:1245-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stancíková, M., Z. Lojda, J. Lukác, and M. Ruzickova. 1992. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 10:381-385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka, S., T. Murakami, H. Horikawa, M. Sugiura, K. Kawashima, and T. Sugita. 1997. Suppression of arthritis by the inhibitors of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 19:15-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van der Heijden, I. M., B. Wilbrink, I. Tchetverikov, I. A. Schrijver, L. M. Schouls, M. P. Hazenberg, F. C. Breedveld, and P. P. Tak. 2000. Presence of bacterial DNA and bacterial peptidoglycans in joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other arthritides. Arthritis Rheum. 43:593-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Voorhis, W. C., L. K. Barret, Y. T. Sweeney, C. C. Kuoi, and D. L. Patton. 1996. Analysis of lymphocyte phenotype and cytokine activity in the inflammatory infiltrates of the upper genital tract of female macaques infected with Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Infect. Dis. 174:647-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viitanen A.-M., T. P. Arstila, R. Lahesmaa, K. Granfors, M. Skurnik, and P. Toivanen. 1991. Application of the polymerase chain reaction and immunofluorescence techniques to the detection of bacteria in Yersinia triggered reactive arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 34:89-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao, Q., R. P. Boushey, M. Cino, D. J. Drucker, and P. L. Brubaker. 2000. Circulating levels of glucagon-like peptide-2 in human subjects with inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Physiol. Regulatory Integrative Comp. Physiol. 278:R1057-R1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]