Abstract

Introduction

The administration of antithrombin III (ATIII) is useful in patients with congenital deficiency, but evidence for the other therapeutic indications of this drug is still uncertain. In Italy, the use of ATIII is very common in intensive care units (ICUs). For this reason we undertook an observational study to determine the pattern of use of ATIII in ICUs and to assess the outcome of patients given this treatment.

Methods

From 20 May to 20 July 2001 all consecutive patients admitted to ICUs in 20 Italian hospitals and treated with ATIII were enrolled. The following information was recorded from each patient: congenital deficiency, indication for use of ATIII, daily dose and duration of ATIII treatment, outcome of hospitalization (alive or dead). The outcome data of our observational study were compared with those reported in previously published randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Results

Two hundred and sixteen patients were enrolled in the study. The clinical indications for using ATIII were sepsis (25.9%), disseminated intravascular coagulation (23.1%), and other clinical conditions (46.8%). At the end of the study, 65.3% of the patients were alive, 24.5% died and 10.2% were still in the hospital. Among the patients with sepsis (n = 56), 19 died during the observation period (33.9%; 95% confidence interval 22.1–47.5%).

Discussion

Our study described the pattern of use of ATIII in Italian hospitals and provided information on the outcome of the subgroup treated with sepsis. A meta-analysis of current data from RCTs, together with our findings, indicates that there is no sound basis for using this drug in ICU patients with sepsis.

Keywords: antithrombin III, disseminated intravascular coagulation, sepsis, septic shock

Introduction

Antithrombin III (ATIII) is a recognized treatment for patients with congenital ATIII deficiency [1,2,3,4,5] (see also the approval of this indication by the Food and Drug Administration); in contrast, the evidence supporting its use for other clinical indications is uncertain [6,7,8,9,10].

In Italian hospitals this drug is widely used in patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs), who are generally given ATIII for the treatment of sepsis or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). The approval of ATIII by the Italian Ministry of Health was granted nearly 10 years ago (before the profound reform of the Drug Regulatory Agency made by the Italian Ministry of Health in 1993) and has remained unchanged since then. This approval of ATIII was rather generic and included 'congenital deficiency of ATIII and all clinical conditions that can cause an acquired deficiency of ATIII'.

Three small randomized studies [7,8,9] and one large international trial [10] assessed the effectiveness of ATIII in sepsis, but none of these trials found a significant benefit in terms of reduced morbidity or mortality. As regards congenital deficiency, the effectiveness of ATIII is fairly well documented [1,2,3,4,5], but these patients are rare. The other clinical indications (such as acute thrombosis or thromboembolism, prevention of DIC in hepatic coma, and treatment of bleeding episodes in cirrhosis) are supported by a small series of very preliminary studies (see, for example, the Drugdex databank, CD-ROM Drugdex, volume 110; Micromedex, Englewood, Colorado, USA).

To achieve a better definition of the current use of ATIII in Italian hospitals and to generate naturalistic data (based on routine practice) about the outcome of this treatment, we undertook a multicenter observational study.

Methods

Design of the study and aims

The study was based on a multicenter observational design. From 20 May to 20 July 2001 all consecutive patients admitted to ICUs in 20 Italian hospitals and treated with ATIII were enrolled in the study. The study had the following aims: (1) surveying the use of ATIII in patients admitted to ICUs; (2) determining the outcome of patients treated with ATIII; and (3) comparing the results obtained from our observational study with those previously found in the randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

A meta-analysis was also conducted to summarize the information deriving from four RCTs [7,8,9,10] that studied the effectiveness of ATIII in sepsis.

Data collection

The following information was recorded from each patient enrolled in the study: (1) demographic characteristics (age, sex, weight); (2) congenital deficiency (y/n); (3) baseline ATIII level; (4) ward of first admission in the hospital; (5) clinical indication for using ATIII (sepsis or DIC or any other clinical condition); (6) daily dose and duration of treatment with ATIII; (7) outcome of hospitalization (alive or dead); and (8) concurrent administration of antibiotics and/or heparin.

Analysis

The information collected from each patient was analyzed by standard descriptive statistics. In the subgroup of patients with sepsis, the in-hospital mortality rate observed in our study was compared with that previously reported by the four RCTs. All rates were presented together with their 95% confidence interval (CI), which was calculated by using Equations 1.26 and 1.27 of Fleiss [11].

Results

The overall number of patients who were admitted to ICUs during the study period was 1648. Of these patients, 216 (13%) were enrolled in our study. The characteristics of these 216 patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 216 patients enrolled in our observational study and of the subgroup of 56 patients treated for sepsis

| Overall group of patients | Patient subgroup with sepsis | |||

| Patients' characteristics | n | Characteristics | n | Characteristics |

| Age (years) | 208 | 62.0 ± 17.2 | 52 | 61.8 ± 16.7 |

| Sex (male, female) | 211 | 146, 65 | 52 | 38, 14 |

| Body weight (kg) | 162 | 75.5 ± 9.2 | 48 | 77.9 ± 16.2 |

| ATIII level at baseline (%) | 209 | 57.4 ± 18.2 | 55 | 54.3 ± 14.9 |

| Congenital deficiency | 180 | 1 (0.5%) | 47 | 0 (0%) |

| Ward of admission (surgery, other) | 204 | 111, 93 | 51 | 27, 24 |

| Administration of antibiotics | 199 | 179 (83%) | 53 | 50 (89%) |

| Administration of heparin | 202 | 107 (50%) | 54 | 28 (50%) |

| Daily dose of ATIII (units per patient) | 195 | 1758 ± 1092 | 47 | 1988 ± 981 |

| Duration of administration of ATIII (days) | 195 | 3.1 ± 4.1 | 47 | 3.5 ± 2.6 |

n is the number of evaluable patients. Where errors are shown these are SDs. The daily doses of ATIII according to the clinical indications were as follows: sepsis (n = 47), 1988 ± 981 units/day; disseminated intravascular coagulation (n = 46), 1857 ± 967 units/day; other indications (n = 94), 1518 ± 1000 units/day. A one-way analysis of variance showed that these values were significantly different (F = 4.1; 2 and 184 degrees of freedom; P = 0.02); post-hoc tests showed that the only difference that reached significance was between sepsis and other indications (P = 0.03).

The clinical indication for using ATIII was sepsis (n = 56), DIC (n = 50), or other (n = 101). Table 1 also reports separate information for the subgroup of 56 patients treated for sepsis.

The duration of ATIII therapy did not differ at levels of statistical significance between patients treated for different clinical indications (P = 0.57 according to an analysis of variance). The daily dose of ATIII showed a difference between sepsis and other indications (Table 1).

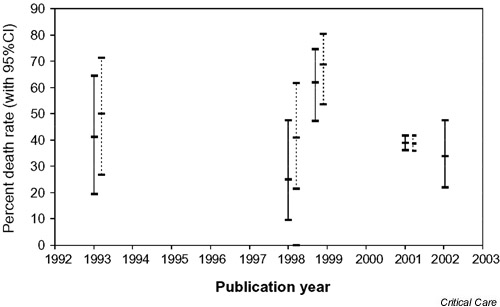

Table 2 reports the outcome of hospitalization according to clinical indication. With regard to the use of ATIII in patients with sepsis, Figure 1 shows the percentage mortality rate (with 95% CI) observed in our study, together with the rates found in four previous studies [7,8,9,10].

Table 2.

Relationship between clinical indication for the use of ATIII and outcome of hospitalization

| Outcome of hospitalization | ||||

| Clinical indication | n | Alive | Dead | Still in hospital at the end of the study |

| Sepsis | 56 | 31 (55.4%) | 19 (33.9%) | 6 (10.7%) |

| DIC | 50 | 30 (60%) | 16 (32%) | 4 (8%) |

| Any other clinical condition | 101 | 75 (74.3%) | 16 (15.8%) | 10 (9.9%) |

| Not reported | 9 | 5 (55.6%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| Total | 216 | 141 (65.3%) | 53 (24.5%) | 22 (10.2%) |

Percentages, which should be read horizontally, indicate which of the three outcomes was found in the various patient subgroups. DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Figure 1.

Percentage mortality rate (with 95% CI) of patients with sepsis: comparison between the results of our observational study and those reported in the four RCTs previously published. Solid lines, treatment groups; broken lines, control groups; dates of publication: 1993, Fourrier et al. [7]; early 1998, Eisele et al. [9]; late 1998, Baudo et al. [8]; 2001, Warren et al. [10] and our study.

Subgroup analyses within the patient cohort of our study did not identify any relationship between mortality and patient characteristics. The administration of heparin, which Warren et al. [10] found to have some implications for outcome, did not influence mortality in our patient series: mortality was 19.6% in the 107 patients who received heparin, compared with 30.5% in the 95 patients who did not receive this drug (P = 0.10) by Fisher's exact test; mortality was 28.6% in the 28 patients with sepsis who received heparin, compared with 42.3% in the 26 patients with sepsis who did not receive this drug (P = 0.39).

Discussion

The main scientific value of our observational and prospective study lies in its naturalistic design; the population of patients that we studied was in fact drawn from the everyday practice of more than 20 hospitals and was intentionally free from specific exclusion criteria.

In interpreting our outcome data, one disadvantage is that the group treated with ATIII was not compared with any reference group observed prospectively within our research; neither did we include any retrospective control group not treated with the drug. However, historical retrospective controls would have raised profound problems of matching the retrospective data with the prospective ones. A prospective enrollment of controls not treated with ATIII was not feasible because the therapeutic policy of the ICUs involved in our study was to administer ATIII to virtually all patients with a diagnosis of sepsis or DIC.

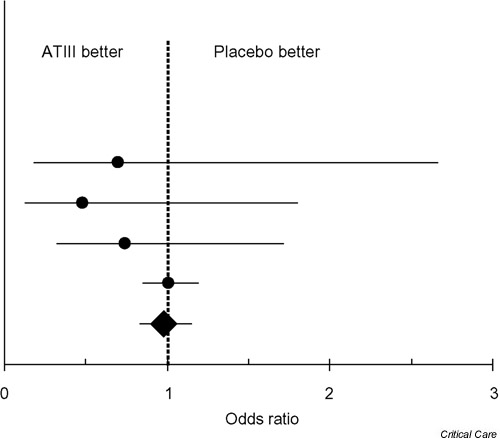

Regardless of our statistical indexes, a 'first-look' comparison between the data on sepsis produced by the previous RCTs (including four treatment groups and four control groups) and those observed in our naturalistic study indicates a complete overlap of the various survival rates and of their respective 95% CIs. This qualitative impression (Figure 1) is in agreement with the meta-analysis shown in Figure 2 (see Appendix2 for details of its methodology).

Figure 2.

Comparison of death rates between patients given ATIII and patients given placebo in the four RCTs that met the inclusion criteria of out meta-analysis. The odds ratios of the individual studies and of our meta-analysis are denoted by dots and by a diamond, respectively; each horizontal bar indicates the 95% CI for the odds ratio, and the vertical dotted line represents the identity line. From top to bottom, datasets are the trials of Warren et al. [10], Baudo et al. [8], Eisele et al. [9], and Fourrier et al. [7]; the bottom dataset is our meta-analysis. In the four RCTs, the crude death rates in the treatment group and in the control group, respectively, were as follows: Fourrier et al. [7], 7 of 17 versus 9 of 18; Eisele et al. [9], 5 of 20 versus 9 of 22; Baudo et al. [8], 31 of 50 versus 33 of 48; Warren et al. [10], 450 of 1157 versus 448 of 1157.

This meta-analysis gave the following results: summary odds ratio 0.98; 95% CI 0.83–1.15, P = 0.80; χ2 for heterogeneity 1.86; 3 degrees of freedom; P = 0.60. In this meta-analysis, the large-scale trial by Warren et al. [10] outweighed the other three small RCTs in that Warren's trial included 93% of the overall cohort of the four RCTs. In the light of the above data, there seems to be no clinical benefit in administering ATIII to critical patients with sepsis; in this context, one crucial point is that the most recent large-scale trial gave very clear results and was negative. The other clinical indications reported in our patients' series were more difficult to interpret because of the nearly complete lack of previous controlled studies exploring these therapeutic issues.

There has been a lively debate in the literature on the relative merits of observational studies and RCTs in providing useful evidence of clinical effectiveness [12,13,14]. Although the great majority of researchers stick to the concept that RCTs are the gold standard, common sense suggests that having information both from RCTs and from observational studies is better than having information from RCTs only. In this framework, our study advances knowledge about the use of ATIII in critical patients.

In conclusion, our findings based on an observational prospective study and on an updated meta-analysis of the previous RCTs do not support the use of this drug in ICU patients with sepsis.

Key messages

Antithrombin III (ATIII) is a recognized treatment for patients with congenital ATIII deficiency; in contrast, the evidence supporting its use for other clinical indications is uncertain.

In Italian hospitals this drug is widely used in patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs), who are generally given ATIII for the treatment of sepsis or disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Three small randomized studies and one large international trial have assessed the effectiveness of ATIII in sepsis, but none of these trials has found a significant benefit in terms of reduced morbidity or mortality.

Our findings, based on an observational prospective study and on an updated meta-analysis of the previous randomized controlled trials, do not support the use of this drug in ICU patients without congenital deficiency.

Competing interests

In 2001 our research group received a grant from Eli-Lilly (Italy) to conduct an original study on factors influencing length of stay in critical patients with sepsis. In Italy, anti-thrombin III is marketed by Aventis-Behring and by Baxter.

Appendix 1: Gruppo di Studio sull'antitrombina III (The Antithrombin Study Group)

The Antithrombin Study Group includes the study coordinators (A Messori, F Vacca, M Vaiani, S Trippoli, Laboratorio di Farmacoeconomia, c/o Azienda Ospedaliera Careggi, Firenze) and a total of 51 participants. The names and addresses of the participants involved in the project were the following (all located in Italy): R Banfi, M Cecchi, E Cini, D Dupuis, T Falai, R Fornaini, A Ipponi, ML Migliaccio, F Pelagotti, L Rabatti, I Ruffino, R Silvano, E Tendi (Firenze, four hospitals); P Becagli, M Monciatti (Empoli); B Bozzone, R Casullo, F Cattel, S Pardossi, R Passera, S Stecca, U Tagliaferro (Torino, two hospitals); P Di Bartolomeo, T Faggiano, M Lattarulo (Bari); N Caboni, A Cannas (Cagliari); A Plescia, M Sorci (Rimini); L Bonistalli, M Puliti (Prato); B Ciammitti, M Costantini, F Mammini (Terni); L De Cicco, G Mazzaferro (Napoli); P Marrone, R Tetamo (Palermo); P Beneduce, MG Celeste, P Fiorani, S Galeassi, G Guaglianone, A Pecere, L Ragni (Roma, two hospitals); SM Germinario (Andria); O Basadonna, L Todesco (Camposampiero, Padova); R Calle-gari, M Pegoraro (Asolo); E Lamura (Ancona).

Appendix 2: Methodology of the meta-analysis

A MedLine search (PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi) was performed to cover the period from January 1980 to November 2001. The search was limited to the studies published in English and was based on four index terms combined with the following Boolean syntax: "antithrombin III" AND (sepsis OR septic shock OR "disseminated intravascular coagulation"). This search was supplemented by examining the Drugdex databank (CD-ROM Drugdex, volume 110; Micromedex, Englewood, Colorado, USA).

Eligible studies were included if they met the following criteria: patients were admitted to an ICU; randomized design; diagnosis of sepsis, septic shock or DIC; assessment of survival. The odds ratio was used as the main index to assess the treatment effect within each trial and to generate the overall results of the meta-analysis. The calculation of the summary odds ratios was based on a random-effect model [15,16]. Heterogeneity was assessed as described previously [17].

Abbreviations

ATIII = antithrombin III; CI = confidence interval; DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulation; ICU, intensive care unit; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

References

- De Stefano V, Leone G, De Carolis S, Ferrelli R, Di Donfrancesco A, Moneta E, Bizzi B. Management of pregnancy in women ATIII congenital defect: report of four cases. Thromb Haemost. 1988;59:193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellgren M, Tengborn L, Abildgaard CF. Pregnancy in women with congenital ATIII deficiency: experience of treatment with heparin and antithrombin. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1982;14:127–141. doi: 10.1159/000299460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannucci PM, Boyer C, Wolf M, Tripodi A, Larrieu MJ. Treatment of congenital ATIII deficiency with concentrates. Br JHaematol. 1982;50:531–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1982.tb01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RS, Bauer KA, Rosenberg RD, Kavanaugh EJ, Davies DC, Bogdanoff DA. Clinical experience with ATIII concentrate in treatment of congenital and acquired deficiency of antithrombin. Am JMed. 1989;87:S53–S60. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)80533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter JH, Fenech A, Ridley W, Benedett B, Cumming AM, Mackie M, Douglas AS. Familial ATIII deficiency. J Med. 1982;204:373–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner K, Kyrle PA. ATIII concentrates – are they clinically useful? Thromb Haemost. 1995;73:340–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourrier F, Chopin C, Huart JJ, Runge I, Caron C, Goudemand J. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ATIII concentrates in septic shock with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Chest. 1993;104:882–888. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.3.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudo F, Caimi TM, de Cataldo E, Ravizza A, Arlati S, Casella G, Carugo D, Palareti G, Legnani C, Ridolfi L, Rossi R, D'Angelo A, Crippa L, Giudici D, Gallioli G, Wolfler A, Calori G. Antithrombin III (ATIII) replacement therapy in patients with sepsis and/or postsurgical complications: a controlled double-blind, randomized, multicenter study. Intens Care Med. 1998;24:336–342. doi: 10.1007/s001340050576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisele B, Lamy M, Thijs LG, Keinecke HO, Schuster HP, Matthias FR, Fourrier F, Heinrichs H, Delvos U. ATIII in patients with severe sepsis: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind multicenter trial plus a meta-analysis on all randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials with ATIII in severe sepsis. Intens Care Med. 1998;24:663–672. doi: 10.1007/s001340050642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren BL, Eid A, Singer P, Pillay SS, Carl P, Novak I, Chalupa P, Atherstone A, Penzes I, Kubler A, Knaub S, Keinecke HO, Hein-richs H, Schindel F, Juers M, Bone RC, Opal SM, KyberSept Trial Study Group. High-dose antithrombin III in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;286:1869–1878. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions, edn 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1981.

- Benson K, Hartz AJ. A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1878–1886. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl JMed. 2000;342:1887–1892. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock SJ, Elbourne DR. Randomized trials or observational tribulations? N Engl JMed. 2000;342:1907–1909. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitti DB. Meta-analysis, Decision Analysis, and Cost-effectiveness Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999.

- Der Simonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Cont Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messori A, Trippoli S, Vaiani M, Gorini M, Corrado A. Bleeding and pneumonia in intensive care patients given ranitidine and sucralfate for prevention of stress ulcer: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br Med J. 2000;321:1103–1106. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7269.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]