Abstract

cDNA cloning is a central technology in molecular biology. cDNA sequences are used to determine mRNA transcript structures, including splice junctions, open reading frames (ORFs) and 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs). cDNA clones are valuable reagents for functional studies of genes and proteins. Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) sequencing is the method of choice for recovering cDNAs representing many of the transcripts encoded in a eukaryotic genome. However, EST sequencing samples a cDNA library at random, and it recovers transcripts with low expression levels inefficiently. We describe a PCR-based method for directed screening of plasmid cDNA libraries. We demonstrate its utility in a screen of libraries used in our Drosophila EST projects for 153 transcription factor genes that were not represented by full-length cDNA clones in our Drosophila Gene Collection. We recovered high-quality, full-length cDNAs for 72 genes and variously compromised clones for an additional 32 genes. The method can be used at any scale, from the isolation of cDNA clones for a particular gene of interest, to the improvement of large gene collections in model organisms and the human. Finally, we discuss the relative merits of directed cDNA library screening and RT–PCR approaches.

INTRODUCTION

The construction and screening of cDNA libraries is a common technique in the analysis of mRNA transcripts. Sequencing of full-length cDNA clones is an accurate and reliable way to delineate complete gene structures in genomic sequence, including exons and introns, open reading frames (ORFs) and 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) (1,2). Large collections of cDNAs have been used in functional genomic studies of genes and proteins, including spotted cDNA microarray analysis (3), yeast two-hybrid protein interaction screening (4,5), and high-throughput X-ray crystallography (6). The development of comprehensive non-redundant cDNA collections is an important objective of the human and model organism genome projects (7,8).

Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) sequencing is an efficient method for obtaining cDNA clones representing a significant fraction of the transcripts encoded in a genome (9–12). However, ESTs sample cDNA libraries at random, and the representation of transcripts in cDNA libraries is related to their expression levels in the tissues and developmental stages profiled, so EST sequencing is inefficient at recovering rare transcripts. The use of normalized cDNA libraries can improve the efficiency of gene discovery by EST sequencing, but even the best methods result in very incomplete normalization, so the advantage of this approach is limited (13–15). In addition, because ESTs are derived from cDNA ends, they often fail to elucidate alternative splicing in the central regions of transcripts. Thus, to screen cDNA libraries for genes and alternative transcripts that are not represented in large EST collections, efficient directed methods are needed.

As a first step in producing a non-redundant collection of Drosophila melanogaster cDNAs, we generated 262 140 5′ EST sequences from directionally cloned cDNA libraries representing a variety of tissues and developmental stages (12,16). These data represent 19.5-fold over-sampling of the 13 449 protein-coding gene models in the Release 4.1 annotation of the D.melanogaster genome sequence (http://flybase.net/annot/). The EST data were used to select cDNA clones for full-insert sequencing to create the Drosophila Gene Collection (DGC). Most clones were selected computationally, initially by inter se clustering and later by alignment to the genome sequence; some additional clones were selected by human curators during genome annotation (http://www.fruitfly.org/EST/index.shtml). Full-insert sequencing of DGC cDNAs (13) led to major improvements in the annotation of protein-coding genes in the genome sequence (2). Within the DGC, we distinguish a set of clones encoding protein sequences that perfectly match translated genome sequence annotations; these clones are suitable for functional genomic and proteomic studies (DGC Gold, http://www.fruitfly.org/EST/gold_collection.shtml). (Full-length cDNAs that do not match annotated gene models may reveal unannotated protein isoforms and so may also be suitable for functional studies.) The DGC currently comprises 6263 Gold cDNAs and 5266 additional sequenced cDNAs.

Our mapping of ESTs to gene annotations shows that there are 3125 annotated protein-coding genes not yet represented in the DGC. In addition, the genome sequence annotation predicts that ∼20% of Drosophila genes produce two or more alternatively spliced transcripts (2), and this is likely an underestimate. Thus, at least 2500 annotated alternatively spliced protein-coding transcripts are also not yet represented in the DGC. Sequencing of the most recent 10 000 5′ ESTs identified cDNAs for only 96 additional genes (1% yield). Although EST sequencing of new libraries from different tissues and developmental stages might marginally increase the rate at which additional genes are sampled by EST sequencing, an efficient method for directed screening of cDNA libraries to recover clones for specific transcripts would be very useful.

The traditional method for screening a cDNA library for clones representing a gene of interest is hybridization of labeled gene-specific DNA probes to colonies or plaques transferred to a nylon filter [reviewed in (17)]. This method is labor and time intensive, especially when the desired clones are rare in the library. It is not an efficient approach for screening libraries on a large scale. A method has been described for screening arrayed cDNA libraries by PCR of pooled clones in a combinatorial scheme (18). This approach requires arraying of individual clones into microtiter wells and is therefore practical only for abundantly expressed transcripts.

RT–PCR is an attractive alternative approach, because it recovers cDNA sequences for specific genes directly, without library screening. In RT–PCR (19), first-strand cDNA is used as a template in a PCR with a pair of gene-specific primers at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the transcript of interest. This procedure can generate cDNAs that are as complete as the starting gene model. However, because it recovers only sequences between the two PCR primers, RT–PCR depends on accurate prediction of the 5′ and 3′ ends of the target transcript in order to produce a cDNA with a complete ORF. The output of most gene-finding algorithms is a single ORF prediction per gene with no predicted UTRs, and it is not uncommon for predicted genes to be missing 5′ and 3′ coding sequences (1,2). Because gene models with complete ORFs are more difficult to predict than is generally appreciated, and because UTRs are very difficult to predict, complete transcripts are typically not captured by RT–PCR. The related Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) (20) method is a directed approach to identifying 5′ and 3′ coding and UTR sequences, but it produces PCR products representing only part of a transcript. In addition, because only one of the primers in a RACE PCR is gene-specific, successful amplification often requires sequential rounds of PCR with nested primers. In order to reliably produce full-length cDNAs using these methods, transcript ends would need to be defined by 5′ and 3′ RACE experiments before conducting RT–PCR experiments. Thus, there are practical issues that limit the utility of RT–PCR as a high-throughput strategy.

A method for obtaining the 5′ and 3′ ends of a transcript simultaneously has been described in which primary double-stranded cDNA is self-ligated in dilute solution to produce circular molecules without a cloning vector (21). The circularized cDNA is used as a template for an inverse PCR (22–24) using gene-specific primers directed away from one another in the sequence of the target transcript. The resulting PCR products include both the 5′ and 3′ ends of the transcript, which are joined together in inverted orientation at the point of ligation. This approach to characterizing the 5′ and 3′ ends of transcripts ensures that the two ends within a PCR product are derived from the same transcript isoform. The products can be cloned and characterized, but they are rearranged relative to the intact transcript. Thus, the method does not lead directly to intact cDNA clones.

Two related methods for amplifying intact cDNA clones from plasmid libraries, MACH-1 and MACH-2 (25), have been described. MACH-1, based on the Stratagene QuikChange™ site-directed mutagenesis protocol (http://www.stratagene.com), uses a pair of overlapping, oppositely directed, gene-specific primers to amplify cDNA sequences from a plasmid library in a linear amplification reaction. The products are self-annealed to form nicked circles, which are repaired upon transformation into a bacterial host. Because MACH-1 is a linear amplification method, it is not suitable for recovery of rare cDNAs. MACH-2, based on a PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis protocol (26), uses two separate inverse PCR with different pairs of gene-specific primers to amplify cDNA sequences from a plasmid library. The linear DNA products from the two reactions are size-selected and purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, mixed together, and melted and re-annealed to form hybrid molecules, which are then transformed into bacteria. MACH-2 appears to be effective and suitable for recovery of rare cDNAs. However, because it requires two PCR per target and includes a gel purification step, it is relatively inefficient and not easily adapted for high-throughput screening.

Here, we describe Self-Ligation of Inverse PCR Products (SLIP), a rapid and efficient method for plasmid library screening that can recover full-length cDNAs representing relatively rare and alternatively spliced transcripts of interest. SLIP is similar to but simpler than MACH-2. It requires one pair of gene-specific PCR primers per target and does not require a gel purification step. We describe screens of cDNA libraries used in our Drosophila EST projects for clones representing 153 transcription factor genes that were not represented by full-length clones in the DGC. Our results demonstrate that the new method is effective in recovering relatively rare cDNA clones from plasmid libraries, that the full-insert sequences of many of the resulting cDNA clones reveal unannotated coding sequences and UTRs in curated gene models, and that the approach can be applied productively in a high-throughput setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PCR primer design

A single transcript model was selected from the Release 3.1 annotation (2) for each curated gene in the list of targets. For genes with multiple curated transcript models, the first(‘RA’) model was arbitrarily selected. Primer3 (27) (http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu/genome_software/other/primer3.html) designs standard PCR primer pairs and can be used to design primers for multiple sequence targets automatically, but it has no explicit inverse PCR primer design feature, so we wrote software to manipulate the transcript sequences.

Primer3 was developed for the purpose of designing primers for PCR amplification of DNA with primers flanking the region to be amplified. Since the SLIP process requires the PCR primers to abut at their 5′ ends with no overlap and in opposite orientation on the template, it was necessary to computationally rearrange our template sequences to mimic the format required for primer3. A separate template sequence was constructed at each base location from position 26 to position 500 in the template sequence, as follows. First, a series of 4 ‘N’s was added to the 3′ terminus of the transcript sequence. Next, the 5′ sequence of the transcript from base 1 to a base in the range from position 26 to position 500 was removed from the 5′ end and attached after the ‘N’s at the 3′ end. This generated a linear representation of the circular plasmid, with potential PCR primer locations at the ends and flanking the entire sequence to be amplified. This procedure resulted in 475 templates for primer design for each transcript sequence of at least 500 bp. The procedure started at base 26 so that sufficient sequence would be available at the 3′ end of the template for primer design.

Next, each template sequence was run through primer3 to design a PCR primer pair, with constraints imposed using the adjustable parameters. Table 1 shows the parameter settings that were used for primer3. A critical constraint was to fix the PCR product length equal to the length of the template, forcing the program to design a pair of PCR primers that included the 5′ and the 3′ terminal bases of the template sequence. A mis-priming library was also employed to prevent the design of primers complementary to the cDNA vector pOT2. A primer pair design was produced for each iteration of the template sequence that had sequences at the ends that allowed design of primers that met the primer3 criteria. Primer3 produces an output file that describes attributes of each primer pair.

Table 1.

Primer3 parameter settings

| Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| Primer length | 23 bases ±2 |

| Max. number of Ns in primer sequence | 0 |

| Product size | Full-length of annotated transcript |

| Tm | 65° ±5 |

| GC clamp | Most 3′ base must be G or C |

| GC content | 50% ±20 |

| Max. complementarity (self) | 8a |

| Max. complementarity (paired primer) | 8a |

| Max. mononucleotide repeat in primer | 5 bases |

| Max. end stability | 9a |

aSee http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu/genome_software/other/primer3.html for score calculation methods.

All candidate primer pairs in the primer3 output file were compared to a database of all curated transcripts in the Release 3.1 annotation using blastn (wublast-2.0 with parameters S = 50 Q = 200). The blastn output files were parsed to check that the targeted transcript had the highest blastn score and was perfectly aligned over the length of the primer sequences. Next, alignments to other transcripts were analyzed. If there were any gaps in the alignment to non-target transcripts, the primer was not disqualified. If the alignment was shorter than 16 bp, the primer was not disqualified. If the non-target alignment was equal to or longer than 16 bp, then the 18 3′-most bases of the primer sequence were further analyzed. If fewer than 16 bases aligned in the 18 3′-most bases, the primer was not disqualified. If greater than or equal to 16 bases aligned in the 18 3′-most bases, the primer sequence was checked to see if the two most 3′ bases aligned. If so, the primer was rejected. This process resulted in a reduced set of primer pairs from which to select the optimum pair for each transcript.

To select one primer pair for each targeted transcript from the set of all acceptable primers, we calculated an objective function for each primer pair:

where Tm is a melting temperature, Wtm is the weight assigned to the Tm (0.3), is the average Tm of the two primers, is the optimum Tm, Wgc is the weight assigned to GC content (0.1), GCavg is the average percent GC content of the primers, GCopt is the optimum GC content, Wblast is the weight assigned to the blastn alignment (0.3), BlastLength is the length of the longest blastn alignment to non-target curated genes, WΔtm is the weight assigned to the difference in Tm between the primers (0.3), and ΔTm is the difference in Tm between the two primers. For each targeted gene, we selected the primer pair with the lowest objective function score.

cDNA library screening

For each targeted gene, the forward and reverse PCR primers (8 µM each) were phosphorylated in a single 15 µl reaction with T4 polynucleotide kinase (0.25 U) at 37°C for 1 h, followed by heat inactivation of the enzyme at 65°C for 20 min.

Aliquots of the GH (adult head, 1.23 µg/µl), LD (embryo, 1 µg/µl), LP (larva and pupa, 1.16 µg/µl) and SD (S2 cell line, 0.66 µg/µl) plasmid pOT2 cDNA libraries described in (12) were pooled to make a mixed library stock. Each library was available as a singly amplified stock, and 10 µl aliquots of each were combined to generate the pool. We estimate the complexity of the mixed stock to be ∼2 × 106 independent clones. The mixed stock (1 µg/µl) was diluted 1:500 to produce a working stock for use in PCR.

PCR was conducted with Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each 15 µl reaction included 1.5 µl of working library stock, 1 µM of each 5′-phophorylated primer, 200 µM dNTPs and 0.3 U of polymerase. Reactions were heated to 98°C for 30 s, followed by 35 PCR cycles including denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 2 min, 45 s. The manufacturer's suggested extension time for complex templates is 30 s per kb; the pOT2 vector is 1.5 kb in length; thus, the extension time we used is sufficient to amplify cDNAs with inserts at least 4 kb in length. The annealing temperature for the first five cycles was ramped down linearly from 72 to 68°C (touchdown PCR). In the subsequent 30 cycles, the annealing temperature was 68°C. After cycling, the reactions were incubated for an additional 5 min at 72°C to finish the final extension. To exchange the buffer and reduce the concentration of unincorporated dNTPs and primers, each PCR product was diluted to 30 µl with dH20 and subjected to gel filtration through a 300 µl Sepharose G-50 column in 96-well format.

Half of each filtered sample (15 µl) was treated with T4 DNA ligase (400 U, New England BioLabs) in a 100 µl overnight reaction at 16°C. DpnI (20 U, New England BioLabs) was then added to each sample, and the reactions were incubated at 37°C for 2 h and then at 80°C for 20 min to inactivate the restriction enzyme.

An aliquot (2 µl) of each self-ligated and digested sample was transformed into TAM1 chemically competent Escherichia coli host cells (Active Motif) in 96-well format according to the manufacturer's instructions. The entire volume of transformed cells was plated on LB agar plates containing chloramphenicol (50 µg/ml) and incubated overnight at 37°C. Four clones per target were grown overnight in 2× YT media containing chloramphenicol (50 µg/ml). An aliquot of each culture was used to produce an archival frozen stock, and the remainder was used to prepare plasmid DNA by a standard alkaline lysis procedure.

Plasmid DNA samples were used to produce three sequence reads. Sequencing reactions were performed with BigDye v3.1 dye-terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems) at 1/16th the manufactures recommended scale. Sequence data were collected on an Applied Biosystems 3730 × 1 capillary device. All templates were sequenced with the primers PM002 (5′ end), PM001 (3′ end) (16), and the target-specific, sense-strand PCR primer. Following data analysis, selected cDNAs were sequenced to completion using additional custom primers.

Sequence assembly and finishing

Sequence trace files were processed using phred and crossmatch to produce vector-masked sequence files with basecalls and associated quality scores (28,29). The three sequence reads from each template were assembled using a customized version of phrap (http://www.phrap.org) in which every trace is included in the assembly. Each sequence assembly was evaluated by a custom script in a series of tests to select clones for full-insert sequencing. Test 1, if the translation of the longest ORF in the contig containing the 5′ end read matched the predicted protein sequence of a transcript of the targeted gene, then the cDNA library screening experiment was declared ‘done’, and the clone was entered into our cDNA sequence finishing pipeline. Our standard cDNA finishing pipeline requires quality standards higher than can routinely be achieved with three traces (phrap estimated error rate less than 1/50 000; individual base quality better than q25), so a further round of primer sequencing was performed if needed. This work was designed manually or by autofinish (30). Test 2, if the sequence assembly produced contigs with only a partial match to the predicted transcript or coding sequence (CDS) because of low sequence quality, sequence gaps, or errors in the gene prediction, then the clone was retained for possible full-insert sequencing. A partial match was defined as alignment of at least 50% of the length of the cDNA contig containing the 5′ read. The percent identify of the match was also reported. If the contig sequence did not meet this criterion, all contigs were concatenated together and compared to the annotated transcript using sim4 (31). Alignment of 50% of the length of the clone sequence, or 100 bp and a percent identity of 50% over the aligned region, was required for inclusion in the cDNA finishing pipeline. Test 3, if the assembly did not show any significant alignment to the target, the clone was discarded.

After all of the cDNA isolates for a particular target were evaluated, we selected from the set according to the rules: (i) if one or more isolates from a target was ‘done’, the isolate that had a poly(A) tail, included the longest 5′-UTR, and had the highest sequence quality was selected. If no isolate had a poly(A) tail, we still proceeded with sequence finishing of the isolate with the longest 5′-UTR, if the entire targeted CDS was captured. All other isolates were removed from the processing queues. (ii) if one or more isolates passed Test 2 and no isolates passed Test 1, all candidate isolates were selected for one round of sequencing using custom primers designed to the target gene sequence. If none of the isolates then passed quality standards, one of the isolates was selected for finishing. The isolates selected for finishing were entered into the cDNA processing pipeline for quality assurance, automated annotation and sequence submission. Sequences of 88 cDNA clones reported here were submitted to the GenBank data library; their accession numbers are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of selected cDNA clones

| Gene namea | Clone IDb | GenBank accession nosc | Classificationd | Annotated transcript lengthe | cDNA insert lengthf | Annotated CDS lengthe | cDNA ORF lengthf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ac* | IP01413 | BT022154 | match | 961 | 962 | 603 | 603 |

| Ada2Ag* | IP01330 | BT022166 | n.d., S268P | 2317 | 2147 | 1581 | 1581 |

| B-H2 | IP01479 | BT022144 | match | 3089 | 3034 | 1935 | 1935 |

| bsh | IP01040 | BT022203 | 5′ extension | 1524 | 2034 | 1281 | 1287 |

| btn | NC | N/A | co-ligated | 2332 | N/A | 474 | N/A |

| C15 | IP08859 | BT022127 | n.d., S113I | 1105 | 1880 | 1017 | 1017 |

| Cdk7 | IP01401 | BT022155 | match | 1392 | 1457 | 1059 | 1059 |

| debcl* | IP01389 | BT022157 | match | 1626 | 1743 | 900 | 900 |

| dmrt11E | NC | N/A | genomic | 1134 | N/A | 1131 | N/A |

| dmrt99B | IP01169 | BT022192 | match | 1533 | 2343 | 1530 | 1530 |

| dys | IP08837 | BT022132 | 3′ extension | 2707 | 3484 | 2643 | 2655 |

| E(bx)* | IP08836 | BT022131 | 3′ short | 7830 | 2631 | 6477 | 2110 |

| e(y)2 | IP01143 | BT022196 | match | 481 | 468 | 303 | 303 |

| eve | NC | N/A | SLIP artifact | 1468 | N/A | 1128 | N/A |

| Fer2 | NC | N/A | SLIP artifact | 840 | N/A | 837 | N/A |

| ftz | IP01266 | BT022173 | match | 1758 | 1758 | 1230 | 1230 |

| gcm2 | IP01423 | BT022152 | match | 2415 | 2257 | 1818 | 1818 |

| gsb | IP01408 | BT022156 | match | 1452 | 1652 | 1281 | 1281 |

| H15 | IP01538 | BT022140 | match | 2555 | 2606 | 1980 | 1980 |

| hang* | NC | N/A | 3′ short | 7002 | N/A | 5877 | N/A |

| hbn | IP01393 | BT022158 | match | 1802 | 1790 | 1227 | 1227 |

| Her | IP01491 | BT022141 | match | 450 | 631 | 447 | 447 |

| HGTX* | IP01125 | BT022198 | match | 3049 | 3229 | 1539 | 1539 |

| HLH3B | IP01280 | BT022174 | match | 1353 | 1434 | 1128 | 1128 |

| HLH4C | IP01307 | BT022167 | match | 1424 | 1456 | 501 | 501 |

| HLHm7 | IP09063 | BT022121 | co-ligated | 723 | 1061 | 558 | 558 |

| HLHmdelta | IP01594 | BT022133 | match | 1016 | 1017 | 519 | 519 |

| HLHmgamma | IP08862 | BT022125 | match | 842 | 959 | 615 | 615 |

| lbl | IP08853 | BT022129 | exon variant | 1847 | 1752 | 1116 | 882 |

| nau | IP01012 | BT022208 | exon variant | 1534 | 1450 | 996 | 984 |

| nht | IP01149 | BT022194 | exon variant | 780 | 966 | 777 | 735 |

| OdsH | IP01524 | BT022139 | match | 1226 | 1310 | 1146 | 1146 |

| Poxn | IP01592 | BT022136 | match | 2178 | 2468 | 1275 | 1275 |

| Rfx | NC | N/A | 3′ short | 3943 | N/A | 2691 | N/A |

| rn | IP01358 | BT022161 | exon variant | 3661 | 3118 | 2838 | 1626 |

| ro | IP01518 | BT022142 | match | 1241 | 1202 | 1050 | 1050 |

| Rpb4g* | IP01323 | BT022168 | exon variant | 732 | 609 | 450 | 417 |

| sc | IP01419 | BT022151 | match | 1422 | 1432 | 1035 | 1035 |

| sens | IP01345 | BT022164 | match | 2450 | 2461 | 1623 | 1623 |

| sisA | IP01195 | BT022187 | match | 768 | 770 | 567 | 567 |

| Sox14* | NC | N/A | genomic | 3159 | N/A | 2007 | N/A |

| Sox15 | IP09065 | BT022122 | n.d., P319L | 3654 | 3638 | 2352 | 2352 |

| Sox21a | IP01552 | BT022137 | co-ligated | 1167 | 2993 | 1164 | 1164 |

| Su(z)2 | IP01427 | BT022149 | co-ligated | 6313 | 2218 | 4104 | 1806 |

| sv | IP01047 | BT022204 | exon variant | 4690 | 920 | 2382 | 537 |

| TfIIA-S-2 | IP09007 | BT022123 | co-ligated | 2917 | 4415 | 1527 | 1527 |

| TfIIEbeta | IP01109 | BT022197 | match | 1052 | 1022 | 876 | 876 |

| tj | NC | N/A | genomic | 1530 | N/A | 1527 | N/A |

| tll | IP01133 | BT022195 | match | 1938 | 1942 | 1356 | 1356 |

| tun* | IP01285 | BT022171 | exon variant | 4114 | 3504 | 3282 | 2670 |

| zen | NC | N/A | SLIP artifact | 1272 | N/A | 1059 | N/A |

| CG10147 | IP01005 | BT022207 | match | 1347 | 1792 | 1344 | 1344 |

| CG10309 | IP01015 | BT022205 | exon variant | 2778 | 3308 | 2775 | 2772 |

| CG10348 | IP08802 | BT022134 | 5′ extension | 1593 | 2054 | 1590 | 1629 |

| CG10431 | IP01025 | BT022206 | 5′ extension | 2151 | 3382 | 2148 | 2352 |

| CG11085 | IP01054 | BT022201 | exon variant | 828 | 1576 | 825 | 885 |

| CG11152 | IP01059 | BT022202 | match | 1800 | 2320 | 1797 | 1797 |

| CG11294 | IP01065 | BT022199 | match | 946 | 1021 | 783 | 783 |

| CG12029 | IP01101 | BT022200 | 5′ extension | 503 | 3021 | 327 | 2253 |

| CG13287 | NC | N/A | 3′ short | 1386 | N/A | 1383 | N/A |

| CG15258 | IP01147 | BT022193 | match | 591 | 702 | 588 | 588 |

| CG15336 | IP01157 | BT022191 | antisense | 546 | 705 | 543 | 318 |

| CG15710 | IP01184 | BT022189 | match | 798 | 932 | 795 | 795 |

| CG15782 | IP01192 | BT022190 | gene merge | 455 | 2383 | 426 | 1920 |

| CG1663 | IP01201 | BT022188 | match | 1164 | 1411 | 1161 | 1161 |

| CG16779 | NC | N/A | co-ligated | 5943 | N/A | 5940 | N/A |

| CG16899 | IP01211 | BT022185 | exon variant | 1074 | 1928 | 1071 | 1326 |

| CG17186 | IP01220 | BT022186 | match | 1146 | 1433 | 1143 | 1143 |

| CG17195 | IP01224 | BT022183 | 5′ extension | 737 | 942 | 723 | 849 |

| CG17196 | IP01227 | BT022184 | 5′ short, u.s. | 831 | 890 | 828 | 495 |

| CG17197 | IP01230 | BT022181 | dicistronic | 951 | 1656 | 948 | 870 |

| CG17198 | IP01235 | BT022182 | 5′ extension | 873 | 1087 | 858 | 897 |

| CG17287 | IP01239 | BT022179 | 5′ extension | 1017 | 1801 | 1014 | 1080 |

| CG17328 | IP01243 | BT022180 | match | 1413 | 1480 | 1239 | 1239 |

| CG17385 | IP01247 | BT022177 | match | 837 | 1192 | 834 | 834 |

| CG17568 | IP01252 | BT022178 | 3′ extension | 1509 | 1856 | 1506 | 1539 |

| CG17801 | NC | N/A | 5′ & 3′ short | 1054 | N/A | 1035 | N/A |

| CG17803 | IP01257 | BT022175 | 5′ extension | 1401 | 2038 | 1329 | 1761 |

| CG18476* | IP01261 | BT022176 | match | 2954 | 2982 | 2808 | 2808 |

| CG2120 | NC | N/A | genomic | 1035 | N/A | 1032 | N/A |

| CG30417 | IP01291 | BT022172 | match | 807 | 863 | 804 | 804 |

| CG30431* | IP01295 | BT022169 | match | 1810 | 1847 | 1254 | 1254 |

| CG30443* | IP01303 | BT022170 | match | 1771 | 1801 | 1686 | 1686 |

| CG31241* | IP01327 | BT022165 | match | 2020 | 2053 | 1473 | 1473 |

| CG31612* | IP01335 | BT022163 | match | 3308 | 3452 | 2961 | 2961 |

| CG32611* | IP08939 | BT022126 | SLIP artifact | 3313 | 3001 | 3309 | 2136 |

| CG32705* | IP01380 | BT022162 | 5′ short | 4705 | 1215 | 4101 | 1188 |

| CG32767* | IP01381 | BT022159 | n.d., frame | 7670 | 5378 | 3843 | 3672 |

| CG32772* | IP01388 | BT022160 | exon variant | 2476 | 3027 | 1629 | 1560 |

| CG3485 | IP01409 | BT022153 | intron | 993 | 1677 | 990 | N/A |

| CG40351* | IP01431 | BT022150 | 3′ short | 5846 | 2006 | 4924 | 1750 |

| CG4318 | IP01435 | BT022147 | 5′ extension | 699 | 1487 | 696 | 708 |

| CG4328 | IP01440 | BT022148 | n.d., frame | 1593 | 1491 | 1590 | 816 |

| CG4565 | IP01448 | BT022145 | 3′ extension | 672 | 886 | 669 | 825 |

| CG4676 | NC | N/A | intron | 1008 | N/A | 852 | N/A |

| CG4956 | IP01459 | BT022146 | 5′ extension | 858 | 1057 | 855 | 906 |

| CG5245 | IP01468 | BT022143 | exon variant | 1506 | 1542 | 1503 | 1422 |

| CG6118 | IP09048 | BT022124 | 5′ short, u.s. | 2832 | 4052 | 2829 | 2646 |

| CG7368 | IP08855 | BT022130 | match | 1593 | 2849 | 1590 | 1590 |

| CG7691 | IP01563 | BT022138 | match | 852 | 1306 | 849 | 849 |

| CG7963 | NC | N/A | co-ligated | 966 | N/A | 963 | N/A |

| CG8089 | IP01584 | BT022135 | n.d., frame | 1875 | 1998 | 1872 | N/A |

| CG8117 | IP08861 | BT022128 | match | 489 | 792 | 486 | 486 |

| CG9793 | IP09168 | BT022120 | intron | 1041 | 1227 | 1038 | N/A |

aGenes represented in our EST collection are indicated by asterisks.

bClone ID numbers for compromised clones that were not fully sequenced are not reported (NC).

cClones that were not fully sequenced were not submitted to GenBank and have no accession numbers (N/A).

dClone classifications relative to the Release 4.1 annotations are indicated. Nucleotide discrepancies (n.d.) are reported with either the corresponding difference in the predicted protein sequence or an indication of a frameshift (n.d., frame). 5′ short clones with upstream in-frame stop codons (5′ short, u.s.), genomic contaminants (genomic), and retained introns (intron) are also indicated by abbreviations. All other classes are reported as described.

eRelease 4.1 annotated transcript lengths and annotated CDS lengths are reported in nucleotides. For genes with multiple annotated transcripts, the length of the one that most closely matches the cDNA sequence is reported.

fcDNA insert and ORF lengths are reported in nucleotides. For clones with unfinished sequences, these data are not known with confidence (N/A). For clones classified as ‘co-ligated’, ‘genomic contaminant’ or ‘retained intron’, ORF lengths are not reported (N/A).

gRpb4 and Ada2A were separate gene annotations in Release 3.1 but are merged into one in Release 4.1. The cDNAs recovered in the two experiments correspond to different Release 4.1 transcript isoforms.

Sequence analysis

Each finished cDNA sequence was aligned to the genome sequence and the annotated Release 4.1 target transcripts using sim4. The highest scoring alignment was recorded, and the corresponding annotated transcript was used for further analysis. Transcript alignments with scores of less than 100% were manually reviewed for nucleotide discrepancies, co-ligation events, retained introns, genomic contaminants and antisense transcripts. The longest predicted ORF was identified in each finished cDNA sequence, and its protein translation was compared to the translated annotated CDS using sim3 (32). Alignments with scores of less than 100% amino acid identity were manually reviewed and annotated for N-terminal and C-terminal extensions and truncations of the predicted protein sequence, exon variants, dicistronic transcripts and merges of annotated genes.

RESULTS

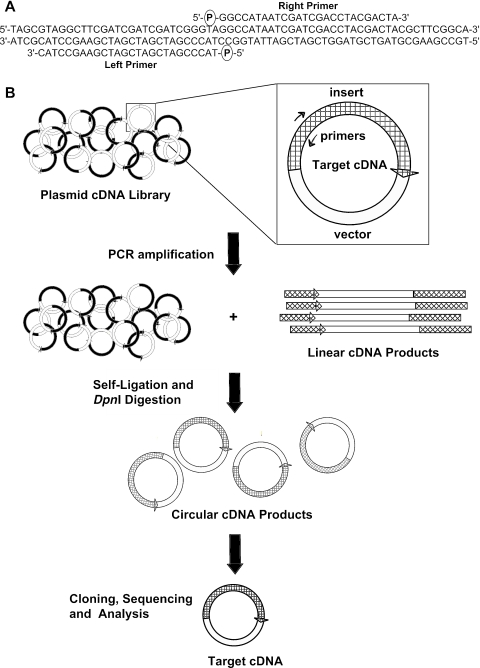

cDNA library screens for 153 transcription factor genes

The SLIP cDNA library screening method is diagrammed in Figure 1. cDNA clones representing a gene of interest are amplified from a plasmid library with gene- or transcript-specific PCR primers. The primers are designed to match the sequence of the target exactly, to abut each other without overlapping, and to be oriented in opposite directions as for inverse PCR. The resulting linear PCR products are treated with T4 DNA ligase to circularize them. Thus, the procedure replicates intact cDNA clones that are identical to the clone from which they were amplified. The reaction mixture is treated with the restriction enzyme DpnI to digest the methylated plasmid library template DNA, leaving the un-methylated PCR products intact. (The cDNA library is methylated by the standard library amplification procedure in a dam+ E.coli host.) The resulting plasmid cDNA products are transformed into bacteria, and individual clones are isolated and characterized by sequencing. The procedure is similar to the Stratagene ExSite™ site-directed mutagenesis protocol (http://www.stratagene.com).

Figure 1.

Description of SLIP. (A) A pair of oppositely directed PCR primers is designed within an exon of a target gene. The primers abut at their 5′ end with no overlap, and the 5′ end are phosphorylated. (B) The primers are used to amplify specific clones from a plasmid cDNA library. The positions of the primers (arrows) within a target cDNA are shown, with the vector indicated in white and the cloned cDNA insert indicated in black and white cross-hatch. The resulting linear products are complete sequences of target clones, including the intact vector and the entire insert, which is split into two halves at the position of the PCR primers. Self-ligation of the linear PCR products into circular products replicates the original target cDNA clones. The methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme DpnI is used to digest the un-amplified plasmid library DNA, leaving the self-ligated amplification products intact. These products are cloned, sequenced and analyzed as described in the text to identify bona fide target-specific cDNAs.

We tested the SLIP method by screening a pool of cDNA libraries for clones representing 153 Drosophila transcription factor genes (Table 2). These targets are D.melanogaster curated genes that have been assigned the function attribute ‘transcription factor’ in the Gene Ontology database (33) and that were not represented by full-length cDNA clones in the DGC. Twenty-six of the target genes are represented by one or more ESTs in our collection, but the cDNAs that had been previously selected for full-insert sequencing were found to be compromised and so replacement cDNAs were needed. The remaining 127 target genes are not represented by ESTs in our large collection, indicating that they are rare in our cDNA libraries. The Release 4.1 annotated transcripts of the target genes range in length from 171 to 8834 bases with a median of 1398 bases.

Table 2.

Experimental design

| Gene namea | Transcript lengthb | Primer 1 | Primer 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abd-B* | 4743 | GCGAGAGAGAAAGAGCGTACGAG | TCTCGTGGTTTCCTCCTGACC |

| ac* | 961 | GGGAACGCAACCGCGTAAAGC | GGGCATTTCTCCGGATAACAGAG |

| Ada2Ac* | 2422 | GGAACTCCATGGTTTTGTATAATCC | TGGTGTGTTCATTCTGATGTGC |

| amos | 1154 | AATCGGGTACCTGAGCGGATCG | GCCAACCTCTTGAGGATCAGCAG |

| ato | 1483 | AACTGCCATTGGTCGTGCCACTC | GGTGGTGAGTTGCAGCGGTCTC |

| BBS2 | 1650 | TGGAGTTCGAGCGTATAGCCACTG | CTTCCTCGGTGGCCTCATTCC |

| B-H2 | 3089 | CCGGAAATGTCCGCAACAACG | TGGCATTGTGGTCATGTGTGG |

| bsh | 1524 | TCCCACTACAACGGAGATCAG | AGTTCCGTGTCGCGAGTGGTG |

| Bteb2 | 962 | CCGGACTTAAGTGATTGGGAGCAG | CGGACATACGGTCAGGTCATTG |

| btn | 2332 | TCACTCTTTCCACTTCACAACATGC | AAACAAAATGAGAGTGTGCAAATG |

| C15 | 1105 | CCATTGAGCGAGTCCCTGCAGTC | CGTTTCGGACTCGTCGTAGCAG |

| cato | 570 | CCGGAATGGCAATTCTTGGATG | CGATAAGAAAGCCCCCTGTCC |

| Cdk7 | 1392 | CTAAACGATGCTGCCCAATGC | GAGCCTCATAAATAGCACGAAAATG |

| CrebB-17A | 1080 | GACCGGGTGCTTGGTGTCAAC | CCCAAATGCTCACCTGCAGTC |

| debcl* | 1626 | ACTGCCCGTTGAAATTCAGAATAC | GGGGAGAGGGAATCGGCCTAC |

| dimm | 1173 | GTGCCACCAGACGAACTTCACAG | GACGGACGGGTCGAGAACTTCC |

| dmrt11E | 1134 | TCGCTGTGTTGTACCTCATGC | GCATGCAAGGGATCGGACTCG |

| dmrt93B* | 978 | CAAGAAGCTCTGCACCTACAAGAAC | TGACCCCGCAGCTCTGAAATG |

| dmrt99B | 1533 | CGCCTTGAAGGGACACAAACG | CTGACCACTCCGTGGTTCCTG |

| dys | 2707 | ACGAAGGGCGCCTCGAAGATG | CGATTTGTTTGCATCGAATCTTG |

| E(bx)* | 8834 | AAAATTTTCACGGTTGCTTAAATGG | TGCGTCTGTTTAAATGTCACTCTTC |

| E(spl) | 540 | CCGAGCTACGAGGTGATGATGG | CGACAAGTGTTTTCAGGTTGTCC |

| E(y)2 | 481 | AGATACGCGACACAAGGATGAGC | AAGTCTTGCAAATTACCAAGTTTCC |

| E5 | 1575 | GAGATCGGCTCCACTAAGGGTCAG | GTCGAGGATTCGCCCACAATC |

| Eip74EF* | 5994 | AGTTTCCGCCGCATTGTAATTG | CATTCAGCAAGTATTCTGCTTTCTC |

| eve | 1468 | ATCCTTCCTGGTTACCCGGTACTGC | ACCTCGCTCCTGCCAGTTACTTC |

| fd3F | 1083 | CGGTCACCTGTGGGCCATTTC | GCTCCTTGGGGCGCTTTAACTC |

| fd64A | 1098 | GGCCTTCTACTACCAGGGCATCG | GGTGAAAACGATCCGCACATCAG |

| fd96Ca | 1119 | CCGCTCAGCGATATCTACAAG | CAACATTTTCTCCGGCGAACTC |

| fd96Cb | 825 | TGGCCTTCGATATGTTCGAGAATG | TGGGATGAAGTGTCCAGTAGGAG |

| Fer2 | 840 | CCAGCAGCATTATATGCAACATAGC | ATGTGACGCAGGTTGTTGGAG |

| ftz | 1758 | TGTACAACATGTATCACCCCCACAG | TGTTCATGTTGTCGGCGTAGCTG |

| gcm2 | 2924 | GGGCTTTCGAATCGCGGAAAAC | TGCGAACAGGCAACACTTGAG |

| gsb | 1452 | AGCTGGAGTCCGTCCCTGTGTC | GCTGCCATCTCCACGATTTGG |

| H15 | 2555 | GACCGCAAATACGGGCGTAAAG | TCCGGTTTTTCGTGCTATTTATC |

| ham | 3327 | ACATGCAGCGAGTGGCACCAG | CCTTGGACGCACAGGACATCTG |

| hang* | 7002 | AGGAAACCCAAGAGCGAAACTCC | TTATCTTCGCCTATTTTTCCACTTC |

| hbn | 1802 | AAAAACCAACTTGTAGCAAGTGAAG | TCTTATTTTGTTAGCGATTTTCCAG |

| Her | 450 | CCCAATTGATTGCTATTGGAGTGG | CTCTGATATACTCCGGATGTAGGC |

| HGTX* | 3049 | CATATAGCCTGATCTCGTTCAAATC | GGTAACTCCGTGGCCGGAAAATATC |

| HLH3B | 1353 | CCGGGCACCTGAACGGTAATG | ATCGCGGTGACTCGTTGGTCTG |

| HLH4C | 1424 | ACCGAAATCAGTGGTGCAAATAGC | GCTGGACACTGGACTTTCTTGC |

| HLH54F | 1066 | GATGCCAGTTCTCAAAGCTCCCAAC | CTCATCGAAGTCGTCATCAAAGAAC |

| HLHm7 | 723 | CTCCGCAAGCTGAAAGAGTCTAAG | ATGCTGCACGGTGACTTCCAG |

| HLHmdelta | 1016 | ACAATGGCCGTTCAGGGTCAG | GTATAATGGGTTTTGATTTGGTGTG |

| HLHmgamma | 842 | CTGGAACTTACCGTCACCCATTTGC | GATATCGGCTTTCTCCAAACG |

| Hmx | 792 | GATGGCAACTCGAAGAGAAAGAAG | ACCATGTGGCGAGGAGCTGTC |

| lbe | 2045 | GTCAGTATCGTCAGTACCGACTTG | AAGCCTTGTACACTCAAATCTTGC |

| lbl | 1847 | CCGTAAGGATACAGCCAGGATGTGC | CTTAGCTCCAAACTCTTTTCTACGG |

| nau | 1534 | CGTACGGTCCGCAAATCGAAGTC | CGAGTGTGTGTACCGCCTTCC |

| nerfin-2 | 2088 | AGTGTCGGGCATTACCAGCAATC | CGACGAAGTGAGTGGTGTCTGG |

| Neu2 | 1149 | TCCAACACCATATGCAAGTCCTG | CAGTGGATCGTGCTTCTCAAC |

| nht | 780 | GCAAGGCAAAAGTCTCCATAAAG | TTGCATCCTGAGAGCCTGAGTC |

| OdsH | 1226 | GCCCCAAATCCGGAAATTAGTC | ATCCATGGACAAGTTGAGAACG |

| org-1 | 2100 | TGCTATGGCAACGACTACTGG | GTTGTAGTCCGTTAGGCTGGTGTC |

| Poxn | 2178 | GCCTGAGACTGAGCATCCTAATAGC | CCAAATGGCGTTGCTCGAACTG |

| Rfx | 3943 | ACCCAGAAGATGTCAACAGTCGTG | TTCGCCTGGTCAGCTCTTTAC |

| rn | 3661 | TCGTTCGTTGTAACGCCCTACC | GGGGTACGAGCGGAACTGGTG |

| ro | 1241 | CATAGCGAACACTACGATTCTATCC | GGATCTAAGCTGTCACTCCTTTTG |

| Rpb4c* | 2422 | TGAGGAGCTGCGCCAAATACTCG | TCCTCGAAGCGACCCTCTAGTGAAG |

| sc | 1422 | CGGCTCCATATAATGTAGACCAATC | GCGAGGAACCAGGCGATAGAG |

| sens | 2450 | GATTTGTGCAGTGAACAGTATTGAG | TCACTTTCTTGGCGTTGTGATCTTG |

| side* | 2820 | GATTTGGGCTGTCGGCTTCAC | GTTTTCCCATTGTCCGGGCATC |

| sisA | 768 | CCGCACTATCGACAGCATCGTC | GTGAACTGCTTCCGCGATACG |

| slou | 2778 | ACAGGCACACAACACGGCACATC | GGCAAGTCAATAGCTAAATGCTG |

| Sox100B | 1945 | CTGAAAGCCGAGCAGAAGAAGG | GGCATAGTTTGCCAAAACCAG |

| Sox14* | 3159 | CAGGACACGGAGAACAAATAAGTCC | GCCAATCTACACTAAACATCGATTC |

| Sox15 | 3654 | GCGCTATCCGCTGTTTGTATCTTG | TCTTGGGAAAATGAAAATTCACG |

| Sox21a | 1167 | TAGGCTCTGGATCGGGAAACAC | CTCCCACACTCATACCCATGC |

| Su(z)2 | 6313 | ACCTGCAAAACACGCACAACAC | GCATCTTTCTGCCTATTCTATCTGC |

| sv | 4690 | AGAGCACGATTCCCAACATCTGC | AGCTGGCCTGTACTTGTATTAAGG |

| TfIIA-S-2 | 462 | CTGGGCAGAACGCTCCAGGAC | CGTTGTGGCCCTGTAATGTTGATAG |

| TfIIEbeta | 1052 | ACCGCCGCCTAGCGATGATTC | GGAGCTGGTCTATCGGGCTTG |

| Tj | 1530 | GTGAAGCGCGAGGATCACAGTC | ATGGCCCAAAGTCGTGACCTG |

| tll | 1938 | AATTCAATTTGTGCAAGCGTTTC | TCACTTGGCACTGGTGTATCTTTG |

| tun* | 8413 | GCTGCAAATCAAATTGTCACGTTTC | AGCTGTGGTTGGGCCATCTTC |

| vnd | 3036 | TTTAAGTTGCCCTACCAGGATACC | TTCCAGACATAGTTCGATTTAGGC |

| zen | 1272 | CGATGTTAACCCCATCGGTCTG | TGATGATGACCATAGATCAAATCAC |

| zen2 | 942 | TTTCTGTCGGGATCGACTGTCGTG | CAGTTAGAAAACGCTCCTGCGTATC |

| CG10147 | 1347 | GAAGTTCCACTCCTTCCGAGCAC | TCCAGAAGCTCGTAGCACTCC |

| CG10309 | 2778 | AGGGACGCGCCAAGAATCTGAG | CGGGTGAGTAGATGTTCGTCTTG |

| CG10348 | 1593 | AAGCGGAGAAGCAGTTTCGATCAG | GCCCTTGGCATGGTGATTTAAG |

| CG10431 | 2151 | TCGGAAGATGACTCCATGAGTGG | AACCCTAATTGATGGCACAGC |

| CG10887 | 2031 | TTCACTCAACAGCAAATAGTGTTCC | AAGAATGTGAACGGCTTTGGTG |

| CG11072 | 171 | CACATCCATCAGAGCCCATAAG | CCCTCTGAACAAACTAGTGTGACG |

| CG11085 | 828 | ATAGACATTGAGGATCGATCTACGC | ATCCGAATCGTCGTTGGAGAGC |

| CG11152 | 1800 | GACTTTGGAACAATACCGCCTCCAG | ATCGTCGTTGATTGAGCTTGTGAAG |

| CG11294 | 946 | GATCTGCTCACGGAGTATATGTTTG | GCCGGGCAGCGGTGATATAAAAG |

| CG11762 | 957 | GGTGGATTTGGACGATGTTCCTG | AATCTTAGTCCGCTTATCATGTGC |

| CG11966 | 1764 | CAACTACATGCAGAGTGCCTATCAC | TTGTTGCTCTCATCCGGCAGTC |

| CG12029 | 503 | CGTTACAACCGCCGAAATAATCC | CACCGTTCGTACGCTCATCAAAC |

| CG13287 | 1386 | CACCGGGTGGAAAGACCACTC | GCGATGTGGGTGTCTCATTGTTG |

| CG13296 | 1398 | GCATGACCACTTCATCGACAGAAAC | TGGTCGGTGTGATACTGGTGCTC |

| CG1379 | 1107 | GGAAACCTGACACTGGGTGATTC | GCATCCGATTAGGTCATCAATCTC |

| CG15258 | 591 | CAAAATCGCATAACGCAGGAG | CTGGATCGACCGGATGTGTTC |

| CG15269 | 1764 | AAGGAGCGTAAATCCGCTCAGG | GCCCAGAATCTTACTGATGCTAAAG |

| CG15336 | 546 | ATCGGACGCGCATCTATTGGAATC | AGCCGCAGAACTCGCACATAAG |

| CG15398 | 885 | AGGGAGCCGAGGAAATGTCTTTGC | CACTTGCTTTGTTCGCCAGGACTTG |

| CG15455 | 921 | TCTACCGATCGCCTTCAAGGTTTTG | GTTTTGTTTGAGCGCCAGTGC |

| CG15696 | 540 | CCACCCAGCATCTTATGTCTCAAAG | GCGTACGGATGGAAAGGCAAG |

| CG15710 | 798 | CCTGTTTGCAGCCGATAAAAGAG | GCGCCACGTACACCTTGGTAAC |

| CG15782 | 455 | TGTCTATGCCCGCGAAATGCTC | TCGGGATAATGGGCTTCCTTG |

| CG1663 | 1164 | GGCGGAGGTACAGGAATCTTTC | AACTTGGATTCCTGAGCAATAGAC |

| CG16779 | 5943 | CCGGAAATGTTGGCAGATGTC | ATCCGGATACCCGATGGTCAG |

| CG16899 | 1074 | TTCTTGCGGTCGAAGGATAATGAG | TCTCTCTGCATCGGAGAACATGAG |

| CG17075 | 2907 | AAGTCCCGCAAAGGGAGTAGTGAC | TCGCTGTGCGACTCCGTCAAG |

| CG17186 | 1146 | CTCGTGCAACGTCTGCGGCTAC | AACAGTGACGATTCCACCTCAGAC |

| CG17195 | 737 | TGCATTTTGAGACGGGACCAC | GGTGTTGCACAAAACGCAGTG |

| CG17196 | 831 | TGGCCTGCTACCGTACAAGCTCAG | GCAAGTTTCCCAGGATATTGTATG |

| CG17197 | 951 | AGTACTTGGCGCGTCGAAATC | TGGTGCAGGCCCATATCAAAC |

| CG17198 | 873 | CAGTTTTTGGGATTGTTTGGACAG | TGGCATTACGTAGAAAGCTTCG |

| CG17287 | 1017 | CGGTGCATTTTCGTAGCTCCAG | AAACCATGTCCATAGAAACATGAAC |

| CG17328 | 1413 | TTTTTAAAACCGATGGCCTACCTTC | CTCTTATTTTAGCGCATTGCATC |

| CG17385 | 837 | AGACGGTGGCCAATCAGTTCAG | CGTCGAATTCTACCTCCATGC |

| CG17568 | 1509 | ATTAGCGAACTAATCGATTTTGCAG | AAGCGTATAGCACTCCGTACACAGC |

| CG17801 | 1054 | GCCGCGTCATATTTGCCCATC | TGGCGTTCATTCTGTTCTAACC |

| CG17803 | 1401 | AGACGACGGAAAAGTACAACATTC | GCCTAAGCTTTTTGTCGACCTG |

| CG18476* | 2954 | ATCAATCTGGATGCAACTGGTAGTC | TTCGGTTAGCTCGCATAAAATCTCC |

| CG2120 | 1035 | CGATCTATTGGAACTTGTGAATGG | TATTCCGAGCCCGGATTCAGC |

| CG30417 | 807 | CAACTGCTGGGCCTCCACGATTAC | CGGATCCAGTGGCTCGTAGAAAAC |

| CG30431* | 1810 | TCGTCCGTATAGATCGGGGCTTC | TTGGCATAGTTGTTTTCCTTGC |

| CG30443* | 1771 | GGAGACTACCCCGAACCTCCAC | TCGGCCTGGTTGGACGATGAC |

| CG31224* | 7059 | CAAAGCGGAAGACGAGAGGAAAG | TGCGCTCCTTCTTCCAATATACAAG |

| CG31241* | 2020 | GCGCCCAAGTACTGCTACTTCTTC | TCTCGAGGTAGAGGCTTCTGG |

| CG31612* | 3308 | ATGTTTCGGCGACGCTTATCAGTAG | GAGTGTCAGCAGAGATTCTTGTTCG |

| CG31632* | 3371 | AAAATGCAAGCCACTTCCGGTCAG | GGCCACGTCCATAACGGTTTTATC |

| CG32532* | 4422 | GCTGGAAAATTTCAATGGAGCGAAG | GGGGGCGTCCTTTCCTGATTTC |

| CG32611* | 3313 | TTGCCGAGCTGCAAACCTTAG | AACGGACGTCCTTCAATATCAC |

| CG32705* | 4705 | TGTCCGTGGGTGAACAACTGC | GTGATGATCGAAGGTCTCTATGC |

| CG32767* | 7670 | CGCAACAGATCGAATTTATACTGC | ATAGGGCGCTATCGTTAATGG |

| CG32772* | 2476 | CTCCGAAGACGTGGATCTGATATTC | TCGTCCTGCGACTGTAGGTTCTC |

| CG3485 | 993 | GATCTCTGAATGCACGGACTGTGAC | ACTTGTGCTATTGAAACCAGCAG |

| CG40351* | 5846 | AGACCCGTCCTATCCAACAATAAC | CCTGGCATTAAACCATCGTAAC |

| CG4318 | 699 | ATCCTTTTCCCAAGACCATTTGC | CCTTCGGTAGAACCGGGAAGC |

| CG4328 | 1593 | GCCGGAGTAGCCCACAATGAC | TTTGGTACTCGCACTCCTTCC |

| CG4374 | 2577 | CGAGTTTTGGCACCAGGACAAG | TAGCCCTGTAACGTGGGATCG |

| CG4565 | 672 | AATTCTGTTCTTTTGAACCCCTGTC | GTACTCGTCCGCCAAGAATTTG |

| CG4575 | 285 | GAAGAATATGGAGGCCTTTCAAAC | CGTATCGCGCCCACTTTGACG |

| CG4676 | 1008 | CTTTGCAGCACTGTCTCAGTTGG | CGATTTTTGGCTCTGCTGCTAAC |

| CG4956 | 858 | AGTTGCATTGGCCATAAAAATCAG | GGCAAAGAAGGTGCAGTGGTG |

| CG5245 | 1506 | AGTTAAAGGCGTCCCGTCGAAGC | GGCTCCAAATCTTTGCCATAACTAC |

| CG5369 | 846 | TATCCGAGAGCAATACGATCCTC | CGGATAGGTCGGTAATGTCTATGTC |

| CG6118 | 2832 | TCGAAGATCATCAAGAAGTGGAAC | CAGTGGAAGCGGCACATTGAG |

| CG7056 | 819 | CGCTGCGCTTCAATCCCATCTAC | AAGTGGGAGCCAGGACAGCAC |

| CG7368 | 1593 | TCCGCTGGTTTCCACCGTGAC | GCTGTGCTCGTCGTGAATTGC |

| CG7691 | 852 | ATTGGCGACAGGGCGACGATATAC | CGCCGCTCGGTTCACTTTGAC |

| CG7786 | 579 | CCATTCCCCAGAATCTTCGGCTAAC | AAATGGAGTAGGACGGATTGTTC |

| CG7963 | 966 | CCTTGCAGCCAATGTATTTATGC | TACACAGGTCCACTTGCATCTCC |

| CG8089 | 1875 | GTGCTGTCGAGGATTCAGGGAGAAG | TTGCACTTGCAGTGGCAGGAAG |

| CG8117 | 489 | GCGACTTGAACGGCTGCAAGG | CGTAAATTGCGTCCTCCAGTTTAG |

| CG9571 | 783 | TCCATCCGATCGCTGCTCTCC | GAAGCTGGACTGGAAGATTGGTG |

| CG9793 | 1041 | TTGGAAGTCCAAAGGGAGTTGCTC | ACAGCGTTCCCTAAAGGATATGG |

| CG9895 | 1233 | TACAGGTTAAATGGATCACGACTGC | CTCTGCGCTCCAGACGACGAC |

aGenes represented in our EST collection are indicated by asterisks.

bRelease 4.1 annotated transcript lengths in nucleotides are reported. For genes with multiple annotated transcripts, the length of the longest is reported.

cRpb4 and Ada2A were separate gene annotations in Release 3.1 but are merged into one in Release 4.1.

Custom scripts were developed to automate PCR primer design for SLIP. To improve the likelihood of recovering full-length cDNAs, primer pairs were restricted to the 5′ most 500 bases of each curated gene model. Aliquots of four plasmid cDNA libraries, all previously used in our EST sequencing projects, were pooled and diluted to produce a template for SLIP screening. Target gene sequences were amplified from the library pool using a standard PCR procedure.

The linear PCR products were circularized and treated with DpnI. The reaction products were cloned, and four cloned isolates per target were analyzed by sequencing. Sequencing reactions were performed using a pair of primers flanking the cloning site in the vector, and the target-specific, sense-strand PCR primer, to produce three reads. The sequence data were analyzed automatically and reviewed manually. A consensus sequence for each clone was assembled and compared to all annotated transcripts of the corresponding target gene. Of the 153 target genes, 92 (60%) yielded one or more gene-specific clones in this initial screen.

The initial library screen failed to yield specific cDNAs for 61 target genes. It also yielded gene-specific but compromised clones for 27 target genes. These clones were compromised in various ways, all previously observed in cDNA libraries, such that they did not represent high-quality, full-length cDNAs (see below). We performed a second library screen on 56 of the 61 target genes for which the initial screen completely failed, and on 13 of the 27 target genes for which the initial screen yielded only compromised clones. In this second screen, we used a 10-fold higher concentration of the cDNA library pool as the template, in an attempt to recover very rare clones. Analysis of the sequence data from the second screen showed that we recovered one or more gene-specific clones for 12 of the 56 targets that failed in the first screen. Furthermore, for the 13 targets that yielded only compromised clones in the first screen, we recovered novel clones for only two targets and identical, compromised clones for ten targets.

Taken together, the two rounds of library screening produced one or more target-specific clones for 104 (68%) of the 153 target genes (Tables 3 and 4). This total includes clones recovered for 85 of the 127 targets that were not represented in our EST collection, and 19 of the 26 targets that were previously represented in our EST data (Table 4) but not necessarily by ESTs from the libraries used in this screen. As described below, these clones were further characterized to determine which ones represent full-length cDNAs.

Table 3.

Summary of cDNA clones recovered

| Classification | Clone counta |

|---|---|

| ORF identical to gene annotationb | 43 |

| ORF alters gene annotationc: | |

| 5′ extension | 10 |

| 3′ extension | 3 |

| 5′ short with upstream in-frame stop codon | 2 |

| Exon variant | 12 |

| Dicistronic | 1 |

| Gene merge | 1 |

| Subtotal: high-quality, full-length cDNAs | 72 |

| Compromised clones: | |

| Nucleotide discrepancyd | 6 |

| Shorte | |

| 5′ short | 1 |

| 3′ short | 5 |

| 5′and 3′ short | 1 |

| Co-ligated insertf | 7 |

| Antisense transcriptg | 1 |

| Genomic contaminanth | 4 |

| Retained introni | 3 |

| SLIP artifact | 4 |

| Subtotal: compromised cDNAs | 32 |

| Gene-specific clones recovered | 104 |

aOne cDNA clone was selected per target gene.

bThe clone encodes a protein that is identical to the corresponding Release 4.1 annotation.

cThese clones encode proteins that differ from their corresponding annotation. ‘5′ extension’ and ‘3′ extension’ clones encode additional N-terminal and C-terminal residues, respectively, relative to the annotation. ‘5′ short with upstream in-frame stop codon’ clones encode full-length ORFs that are missing sequences encoding N-terminal residues relative to the annotation and may represent alternatively spliced products. ‘Exon variant’ clones contain sequence differences relative to the annotation at internal positions in the CDS and represent alternatively spliced products.

dThe sequence of these clones have nucleotide differences, most likely the result of errors generated by reverse transcriptase during library construction, that introduce a missense or frameshift change in the ORF relative to the annotated CDS.

eThese clones are missing sequences encoding the N-terminal portion of the predicted protein sequence of the annotation for the ‘5′ short’ class, the C-terminal portion for the ‘3′ short’ class, or both for the ‘5′ and 3′ short’ class.

fThese clones contain sequences from two unrelated genes and are almost certainly the result of two cDNA molecules being cloned into the same plasmid vector during library construction. In three such cases, the clones encode proteins that are identical to the targeted annotation.

gThe sequence of the clone overlaps the annotated gene model but is transcribed from the opposite strand.

hThese clones do not include a poly-adenylated tail. These are genomic clones that contaminate the cDNA libraries.

iThese clones are poly-adenylated and include unprocessed intron.

The 49 gene targets that failed to yield target-specific clones fall into three classes. For two target genes, all clones failed to yield sequence data. For 16 target genes, all isolates corresponded to genes that were not the intended targets and did not include a complete copy of one or both of the PCR primer sequences. For 31 target genes, the sequences of all isolates included at least one copy of one or both of the PCR primer sequences, but were otherwise unrelated to the target gene.

We examined the library screening results to look for correlations that might predict successful clone recovery. Named genes are more likely to have been studied and validated at the molecular level, so they might be more likely than un-named genes (annotated based on computational results) to yield specific clones in a cDNA library screen. Of the 153 target genes, 79 are named genes and 74 are un-named genes designated only by a CG (Curated Gene) number in the Release 4.1 annotation. At least one target-specific cDNA was recovered for 51 (65%) of the named genes and 53 (72%) of the un-named genes. Because the library screening method is PCR-based, we examined whether the rate of recovery of gene-specific clones was higher for target genes with shorter predicted transcripts. The median lengths of the Release 4.1 annotated transcripts are 1423 bases for the 104 targets for which gene-specific clones were recovered and 1398 bases for the complete set of 153 target genes. Thus, neither attribute of the target genes is correlated with success in library screening.

Full-insert sequencing and characterization of cDNAs

The sequence data from the 104 genes with target-specific clones were further analyzed to determine which represented full-length cDNAs (Tables 3 and 4). cDNAs for which the initial three sequence reads did not produce a complete, high-quality sequence of the cloned insert were selected for sequence finishing. Finishing reads were produced using custom primers designed from the sequence assembly and the annotated transcript model. If a cDNA was found to be compromised, the complete sequence of the insert was not necessarily determined.

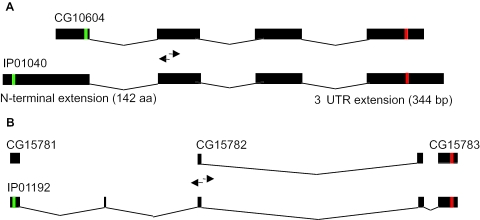

The predicted protein sequence encoded by the longest ORF in the finished sequence of each cDNA clone was compared to the predicted protein sequence in the recently available Release 4.1 genome sequence annotation (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu/). For 43 (28%) of the 153 target genes, the selected cDNA contains a complete ORF that encodes a protein identical to that of the gene model. For 29 (19%) target genes, the cDNA represents a transcript with an ORF that is not identical to that of an annotated transcript and provides evidence that these gene models should be modified. The cDNAs for 15 of these are classified as ‘5′ extension’, ‘3′ extension’, or ‘5′ short with upstream in-frame stop codon’, meaning that the cDNAs encode a protein sequence that varies in the number of terminal amino acids relative to the gene model (Figure 2A). The cDNA clones for another 12 of these target genes are classified as encoding ‘exon variants’, meaning that the cDNA encodes a protein sequence that diverges from that of the annotated gene model, indicating differences in the pattern of mRNA splicing. These include four cDNAs that encode alternate amino termini, one that encodes an alternate C-terminus, and seven that encode different amino acids at locations internal to the CDS. Lastly, one cDNA represents a dicistronic transcript containing both CG17197 and CG17198, and another cDNA provides evidence to merge three annotated genes (CG15781, CG15782 and CG15783) into one gene with a single, continuous ORF (Figure 2B). In summary, high-quality, full-length cDNA clones were recovered for 72 (47%) of the 153 target genes. This total includes 11 of the 26 target genes that were represented by ESTs and 61 of the 127 target genes that were not.

Figure 2.

cDNA sequences improve gene annotations. (A) Comparison of cDNA IP01040 to the targeted Release 4.1 annotated gene model CG10604. Exons (filled boxes), introns (connecting lines), start codons (green) and stop codons (red) are indicated. The positions of the PCR primers used in the SLIP screening experiment are shown (arrows not to scale). The cDNA subsumes the gene model and extends beyond it by 829 bases at the 5′ end, including 5′-UTR sequence and sequences encoding an additional 142 N-terminal amino acids, and by 344 bases at the 3′ end. (B) Comparison of cDNA IP01192 to the three corresponding gene models CG14781, CG17782 and CG15783. The positions of the PCR primers within the target gene model CG15782 are indicated. The cDNA shows that the three annotated gene models are parts of one gene with a single long ORF.

For the remaining 32 (21%) genes with one or more target-specific clones, all clones were compromised in various ways (see Tables 3 and 4). For 27 genes, the clones contain well known cDNA library artifacts, including nucleotide discrepancies, truncations of the 5′ and/or 3′ ends, retained introns, genomic clone contaminants, and co-ligated inserts. This set includes three cDNAs with co-ligated inserts that nevertheless include complete ORFs for the target genes; these ORFs are suitable for cloning into expression systems. The set also includes six clones with nucleotide discrepancies that represent full-length cDNAs; these discrepancies could be repaired by site-directed mutagenesis to produce high-quality cDNAs. Artifacts attributable to the SLIP screening procedure itself are present in the clones selected for four target genes. One clone contains just one of the two PCR primer sequences, two clones contain multiple concatenated copies of both primer sequences, and a fourth clone has a 2 bp deletion at the point of ligation where the 5′ ends of the two primers abut. The latter clone is in all other respects a full-length cDNA and could be repaired by site-directed mutagenesis. Finally, one clone corresponds to an antisense transcript and may represent a complete transcript. A number of such cDNAs were documented in the Release 3.1 genome sequence annotation (2), and the existence of antisense transcripts has been reported in many organisms (34).

PCR has a bias toward amplification of short products, so we examined the lengths of the cDNAs recovered in our screens. The longest cDNA recovered for which we produced a finished sequence has an insert length of 4415 bp, but it is compromised by co-ligation. The longest full-length, high-quality cDNA recovered has an insert length of 3504 bp and contains an ORF of 2670 bp. The longest ORF in a high-quality, full-length cDNA recovered in our screen is 2961 bp in length. There are nine target genes with annotated CDS lengths greater than 3000 bp for which cDNAs were recovered, and none of these cDNAs encodes the complete ORF: four are 5′ or 3′ short, two are co-ligated and short, one contains a SLIP artifact, one contains a frameshift, and one encodes a full-length version of a shorter exon variant. Thus, the screen failed to recover full-length cDNAs for the longest target genes.

To assess whether SLIP selects for short clones, we compared the results of our directed screen to our EST sequencing results for the same cDNA libraries. In a set of ∼80 000 5′ EST sequences, the fraction that include the predicted start codon of the corresponding gene model in the Release 1 genome sequence annotation was 80% (12). Because this result is based on 5′ ESTs and not on full-insert cDNA sequences, it does not account for clones truncated at the 3′ end, and thus somewhat overestimates the frequency of full-length clones in the libraries. In the directed library screens reported here, the cDNAs for 72 of the 104 selected target-specific clones contained high-quality, full-length ORFs, another 10 cDNAs are full-length but compromised by nucleotide discrepancy or co-ligation (including one ‘SLIP artifact’ clone compromised by a 2 bp deletion), and an additional five cDNAs classified as ‘3′ short’ also contain the predicted start codon (Tables 3 and 4). Therefore, 87 (84%) of the cDNAs reported here include the predicted start codon of the Release 4.1 gene model. Thus, similar frequencies of full-length cDNA clones were recovered by 5′ EST sequencing and by SLIP screening.

Finally, we note that Ada2A and Rpb4 were distinct genes in the Release 3.1 annotation but have been merged into a single gene with multiple transcript isoforms in the Release 4.1 annotation. The two screening experiments performed on the Rpb4/Ada2A gene, based on the Release 3.1 annotation and with different PCR primers, recovered cDNAs representing different transcript isoforms, and so the two experiments were treated as independent in our analyses.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that SLIP is an efficient and effective method for screening plasmid cDNA libraries. In screens for 153 Drosophila transcription factor genes known to be represented at relatively low levels in our cDNA libraries, we recovered high-quality, full-length cDNAs with complete ORFs for 72 genes and compromised cDNAs for another 32 genes. The six cDNAs compromised by nucleotide discrepancies, and one clone with a 2 bp deletion resulting from a SLIP artifact, could be repaired by site-directed mutagenesis to produce high-quality, full-length cDNAs. Three of the co-ligated cDNAs encode complete ORFs suitable for cloning into expression systems. Thus, by a more liberal standard, full-length cDNAs were recovered for 82 genes. SLIP is simpler to perform than the similar MACH-2 method, and both methods are considerably more efficient than the traditional hybridization-based library screening approach.

Because PCR tends to amplify shorter products more efficiently, SLIP likely has a bias toward recovery of shorter clones. Thus, if a cDNA library contained clones of various lengths for a target gene, SLIP might recover only short cDNAs with incomplete ORFs. Many of the short clones in cDNA libraries are missing the 5′ end of the transcript. We took two measures to improve the recovery of full-length clones: we designed PCR primers within the first 500 bases of each annotated transcript model, and we performed PCR with an extension time sufficient to amplify cDNAs with inserts of at least 4 kb in our 1.6 kb cloning vector pOT2. We recovered relatively long full-length cDNA clones, but we did not recover full-length clones for target genes with ORFs longer than 3 kb. Comparison to EST sequencing results from the same cDNA libraries shows that the two approaches recovered full-length cDNAs at a similar rate. This suggests that full-length cDNAs for target genes with long ORFs are rare in the cDNA libraries used in this study. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that some long transcripts were not recovered in our screens due to the PCR conditions used.

Modifications to the SLIP protocol are likely to improve recovery of long cDNAs. Techniques for PCR amplification of large fragments, including increasing the number of cycles of amplification, increasing the extension time and employing DNA polymerases optimized for ‘long PCR’ could be incorporated to reduce size bias due to the PCR step and recover long cDNAs. PCR amplification of fragments at least 20 kb in length from complex templates such as the human genome is a routine procedure (35), and kits for this purpose are available from several commercial suppliers. Libraries containing full-length cDNAs for very long transcripts are also necessary for recovery of long cDNAs, and methods for constructing such libraries have been developed (36). In addition, PCR products could be size-selected by excision from agarose gels before the self-ligation step. Although we have not demonstrated recovery of very long cDNAs using SLIP, we see no reason the method should be significantly limited by the lengths of transcripts or cloning vectors.

The success of SLIP screening was not significantly correlated with named genes, a common surrogate for the confidence of the target gene annotation, nor with the presence of ESTs in our collection. This suggests that recovery of a cDNA clone for a target gene depends primarily on the presence of a cDNA clone in the library. Because we diluted the cDNA library pool 500-fold for the first round of screening experiments, library complexity seemed likely to be a limiting factor. To test this, we performed a second screen for 69 target genes, including 56 targets that failed to yield specific clones in the first round of screening, using a 10-fold higher concentration of library pool (50-fold dilution). An additional twelve genes yielded specific clones in this second screen. The effect of library concentration was not dramatic, however, which suggests that most of the complexity of the library pool was represented in each sample in the initial round of screening. Statistical analysis of the results indicates that the additional successes in the second round of screening are consistent with the expected increase from selection of additional isolates for sequence analysis, with the underlying screening success rate identical for both library dilutions (data not shown). Note that these cDNA libraries had already been extensively sampled by EST sequencing, and this had not yielded clones for 127 of the 153 genes targeted in this study. To use this screening method to recover cDNAs for the transcription factor genes that are still not represented in our collection, new cDNA libraries with higher complexity and from additional tissues and developmental stages would seem to be required.

Since PCR primers were designed based on Release 3.1 annotated genes, including many for which no molecular evidence currently exists, our success in recovering clones depended upon the accuracy of the gene predictions. In 29 cases, the clones recovered in the screen provide evidence that the corresponding gene models should be modified. For three of the failed library screening experiments, the revised Release 4.1 gene models do not include the Release 3.1 exons used to design the PCR primers. This provides a trivial explanation for these failures. Further examination of the PCR primer sequences and the gene models they were designed to target may suggest other ways of improving the success rate.

The 49 genes that did not yield target-specific clones probably failed due to absence of clones from the cDNA library aliquot. Most of the failed screens yielded clones representing genes that were not targets. These non-target clones probably arise by mis-priming during PCR in the absence of target-specific cDNAs. Another potential explanation for the recovery of non-target clones is incomplete DpnI digestion of the library template DNA. However, in many cases the sequence traces from non-target clones include sequences complementary to one or both of the corresponding PCR primers. Thus, mis-priming appears to be the primary failure mode.

Our results suggest ways of optimizing the screening procedure. One of the easily adjusted parameters is the number of isolates selected for sequence analysis. Based on a retrospective analysis, we estimate that by characterizing four isolates per target instead of three, we have increased our screening success rate by ∼12%. Similarly, characterizing four isolates per target yields ∼32% more screening successes than two isolates, and 88% more screening successes than a single isolate. We estimate that selecting more than four isolates will result in a maximum increase of 5% in the number of successes, and this needs to be balanced against the increase in costs of characterizing additional clones. Another parameter that may be adjusted is the number of isolates selected for full-insert sequencing. While in most cases all of the characterized isolates were identical (based on analysis of the three initial sequence reads), there were cases in which different clones were recovered. These may indicate alternative transcription start sites or alternative splicing, rather than incomplete cDNAs. Another area for optimization is in the automated analysis of the initial sequence reads to determine which clones should be considered for full-insert sequencing. Analysis of the finished sequences from these experiments, largely gained through manual examination, suggests that a useful criterion for clone selection would be 50% or greater sequence identity of the clone and the corresponding gene model over at least half the length of the sequence data generated from the clone.

The success of these directed library screens raises the question of when a project to produce a non-redundant cDNA collection should switch from an EST-based approach to a directed approach. At the end of our EST sequencing project, the final 10 000 EST sequences identified cDNAs representing just 96 (1%) new genes not previously represented in the collection. At that point, it was decided that additional EST sequencing was not warranted. If an efficient directed method had been available, we might have switched from EST sequencing to directed library screening at an earlier stage in the DGC project.

In our view, the results described here justify a larger scale SLIP screen for cDNA clones representing the remaining annotated genes and alternative transcripts that are not yet represented by cDNA clones in the DGC. We assert that cDNAs obtained by library screening can be more informative and valuable than RT–PCR products. The principle advantage of cDNAs over RT–PCR products is that cDNAs can recover sequences at the 5′ and 3′ ends of transcripts that are not represented in annotated gene models. In our screens, we recovered full-length cDNA clones that extend the ORF of the annotated gene model in the 5′ (10 genes; e.g. Figure 2A) or the 3′ (3 genes) direction, that discover a dicistronic transcript (one gene-pair), and that fuse gene models (three gene models into one gene; Figure 2B). For these 15 genes, RT–PCR experiments based on the ORFs in the annotated gene models would have amplified cDNA products representing incomplete ORFs encoding truncated protein sequences. Furthermore, such RT–PCR data would appear to validate the incomplete gene models. In addition, we recovered five full-length cDNAs classified as exon variants that have alternative 5′- or 3′-terminal coding sequences that are not present in the genome annotation. Because the termini of these ORFs are not present in the current genome annotation, they would not be recovered in annotation-based RT–PCR experiments. The 5′ and 3′ ends of transcripts can be recovered by RACE, but this approach does not lead directly to full-length cDNA clones. Thus, because it involves fewer assumptions based on predicted transcript structures, we consider directed cDNA library screening to be a more conservative and informative approach than RT–PCR.

RT–PCR is likely to be more sensitive than directed cDNA library screening for the recovery of sequences of transcripts with extremely low expression levels because it does not involve library construction steps, which inevitably reduce the complexity of the sample. RT–PCR is also likely to be more effective for recovery of long transcripts, since it constrains amplified transcript sequences to include the 5′ and 3′ ends defined by the PCR primers. Thus, we do not assert that directed cDNA library screening is better than RT–PCR. Instead, we maintain that SLIP can be more informative than RT–PCR and that the two approaches are complementary, each with distinct advantages and disadvantages.

In a pilot study evaluating the use of RT–PCR to generate cDNA clones for the Mammalian Gene Collection, acceptable full-ORF clones were recovered for 67% of 384 well characterized human genes that had sequences in the RefSeq database but that were not yet represented by cDNAs in the collection (37). In the study, RT–PCR was performed on a series of RNA templates representing different human tissues until a PCR product of the expected size was obtained for each target gene. Multiple bands were observed in many of the RT–PCR, so bands of expected size were purified by excision from agarose gels before cloning. Twelve or more cloned isolates were end sequenced for each target; 4718 clones were sequenced to recover acceptable clones for 259 genes. In our study, the targets include many uncharacterized predicted genes, the cDNA libraries were pooled into a single PCR template, no agarose gel analysis or purification was performed, and four clones were analyzed per target (although 67 targets were subjected to two rounds of screening). The target gene sets, the tissue sampling approaches, and the work expended per target are quite different in the two studies, making their direct comparison difficult.

A productive and rigorous strategy for cloning and characterizing a eukaryotic transcriptome might involve successive phases of EST sequencing, directed cDNA library screening using SLIP, RT–PCR amplification of annotated ORFs and RACE experiments to recover uncaptured UTRs and coding sequences and to precisely define transcription start sites. A strategy based purely on RT–PCR and RACE could also be effective, particularly if advances in genome annotation approaches lead to significant improvements in gene prediction.

Finally, cDNA libraries are often constructed from RNA isolated from particular tissues or developmental stages, so EST and cDNA sequences can provide data on when and where a transcript is expressed. We pooled cDNA libraries into a mixed template to improve the efficiency of our screens, resulting in the loss of this spatial and temporal expression information. In Drosophila, large datasets on RNA expression have been produced in microarray studies (38,39) and embryonic in situ hybridization experiments (40), and these data have much higher resolution and reliability than data from cDNA library associations. If cDNA libraries constructed with library-specific sequence tags were used, as in the rat EST project (41), then the library source information for cDNAs amplified from a pooled template would be retained.

In summary, SLIP is an effective method for increasing the representation of genes and transcripts in comprehensive cDNA collections, such as those currently under construction by the NIH Mammalian Gene Collection project for several model organisms and the human (7,8). We have used it to recover full-length cDNA clones for 72 genes with relatively low expression levels. Our results also demonstrate that SLIP can be used to screen for cDNAs representing alternatively spliced transcripts. By designing PCR primers in predicted isoform-specific exonic sequence, cDNAs containing the alternatively spliced sequences can be targeted. Finally, the utility of SLIP is not limited to genomic applications. The method is simple and should be useful in any project requiring the isolation of cDNA clones. The main limitation is the availability of high-quality plasmid cDNA libraries representing organisms, tissues and developmental stages of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gerald M. Rubin for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Ling Hong and Gerald M. Rubin for providing the cDNA libraries used in this study. The work described here was supported by NIH grant HG002673 to S.E.C. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by NIH grant HG002673.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haas B.J., Volfovsky N., Town C.D., Troukhan M., Alexandrov N., Feldmann K.A., Flavell R.B., White O., Salzberg S.L. Full-length messenger RNA sequences greatly improve genome annotation. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-6-research0029. RESEARCH0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Misra S., Crosby M.A., Mungall C.J., Matthews B.B., Campbell K.S., Hradecky P., Huang Y., Kaminker J.S., Millburn G.H., Prochnik S.E., et al. Annotation of the Drosophila melanogaster euchromatic genome: a systematic review. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0083. RESEARCH0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schena M., Shalon D., Davis R.W., Brown P.O. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uetz P., Giot L., Cagney G., Mansfield T.A., Judson R.S., Knight J.R., Lockshon D., Narayan V., Srinivasan M., Pochart P., et al. A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2000;403:623–627. doi: 10.1038/35001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito T., Chiba T., Ozawa R., Yoshida M., Hattori M., Sakaki Y. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:4569–4574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061034498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui R., Edwards A. High-throughput protein crystallization. J. Struct. Biol. 2003;142:154–161. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strausberg R.L., Feingold E.A., Klausner R.D., Collins F.S. The mammalian gene collection. Science. 1999;286:455–457. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerhard D.S., Wagner L., Feingold E.A., Shenmen C.M., Grouse L.H., Schuler G., Klein S.L., Old S., Rasooly R., Good P., et al. The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA project: the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC) Genome Res. 2004;14:2121–2127. doi: 10.1101/gr.2596504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams M.D., Kelley J.M., Gocayne J.D., Dubnick M., Polymeropoulos M., Xiao H., Merril C.R., Wu A., Olde B., Moreno R.F. Complementary DNA sequencing: expressed sequence tags and human genome project. Science. 1991;252:1651–1656. doi: 10.1126/science.2047873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCombie W.R., Adams M.D., Kelley J.M., FitzGerald M.G., Utterback T.R., Khan M., Dubnick M., Kerlavage A.R., Venter J.C., Fields C. Caenorhabditis elegans expressed sequence tags identify gene families and potential disease gene homologues. Nature Genet. 1992;1:124–131. doi: 10.1038/ng0592-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delseny M., Cooke R., Raynal M., Grellet F. The Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA sequencing projects. FEBS Lett. 1997;405:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin G.M., Hong L., Brokstein P., Evans-Holm M., Frise E., Stapleton M., Harvey D.A. A Drosophila complementary DNA resource. Science. 2000;287:2222–2224. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]