Abstract

The β-subunit of the dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) enhances the Ca2+ channel and voltage-sensing functions of the DHPR. In skeletal myotubes, there is additional modulation of DHPR functions imposed by the presence of ryanodine receptor type-1 (RyR1). Here, we examined the participation of the β-subunit in the expression of L-type Ca2+ current and charge movements in RyR1 knock-out (KO), β1 KO, and double β1/RyR1 KO myotubes generated by mating heterozygous β1 KO and RyR1 KO mice. Primary myotube cultures of each genotype were transfected with various β-isoforms and then whole-cell voltage-clamped for measurements of Ca2+ and gating currents. Overexpression of the endogenous skeletal β1a isoform resulted in a low-density Ca2+ current either in RyR1 KO (36 ± 9 pS/pF) or in β1/RyR1 KO (34 ± 7 pS/pF) myotubes. However, the heterologous β2a variant with a double cysteine motif in the N-terminus (C3, C4), recovered a Ca2+ current that was entirely wild-type in density in RyR1 KO (195 ± 16 pS/pF) and was significantly enhanced in double β1/RyR1 KO (115 ± 18 pS/pF) myotubes. Other variants tested from the four β gene families (β1a, β1b, β1c, β3, and β4) were unable to enhance Ca2+ current expression in RyR1 KO myotubes. In contrast, intramembrane charge movements in β2a-expressing β1a/RyR1 KO myotubes were significantly lower than in β1a-expressing β1a/RyR1 KO myotubes, and the same tendency was observed in the RyR1 KO myotube. Thus, β2a had a preferential ability to recover Ca2+ current, whereas β1a had a preferential ability to rescue charge movements. Elimination of the double cysteine motif (β2a C3,4S) eliminated the RyR1-independent Ca2+ current expression. Furthermore, Ca2+ current enhancement was observed with a β2a variant lacking the double cysteine motif and fused to the surface membrane glycoprotein CD8. Thus, tethering the β2a variant to the myotube surface activated the DHPR Ca2+ current and bypassed the requirement for RyR1. The data suggest that the Ca2+ current expressed by the native skeletal DHPR complex has an inherently low density due to inhibitory interactions within the DHPR and that the β1a-subunit is critically involved in process.

INTRODUCTION

The dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) of skeletal muscle is a heteropentamer composed of α1S, β1a, α2-δ1, and γ1 subunits. This complex forms a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel that is specialized in coupling membrane excitation to the opening or ryanodine receptor type 1 (RyR1) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Although excitation-contraction (EC) coupling requires charge movements in the DHPR, the opening of the DHPR Ca2+ channel is not essential. Not only is the opening of the Ca2+ channel nonessential, but it has long been suspected that the great majority of the skeletal DHPRs do not contribute to the Ca2+ current (Schwartz et al., 1985). This has been suggested also by developmental studies showing that skeletal DHPR Ca2+ current and charge movements are differentially regulated. The maximal Ca2+ conductance and charge movement densities of mouse skeletal myotubes are ∼140 pS/pF and 7 fC/pF during the late gestation period (Strube et al., 1996, 2000). However, in adult mouse fibers, the Ca2+ current density remains at approximately the same level (85 pS/pF, Wang et al., 1999; 160 pS/pF, Jacquemond et al., 2002), but charge movements increase manyfold (40 fC/pF, Wang et al., 1999; 25 fC/pF, Jacquemond et al., 2002). Thus, as the myotube matures, the DHPR complex becomes preferentially engaged in voltage-sensing, and the excess of charge movements is likely to represent a functional adaptation of the complex to an increased demand for EC coupling and force generation.

A critical regulator of DHPR function is the β-subunit of this complex. Numerous expression studies in heterologous cells have shown that Ca2+ channel β-subunits profoundly affect Ca2+ current expression and gating properties of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Birnbaumer et al., 1998). β-subunits are cytoplasmic or membrane-associated proteins of ∼65–75 kDa encoded by four genes. Alternate splicing of the β1 gene produces at least three isoforms. The β1a variant is exclusively present in skeletal muscle, whereas the other two (β1b, β1c) are expressed in brain, heart and spleen (Powers et al., 1992). Transcripts of the other three genes (β2, β3, β4) were isolated from cardiac and brain cDNA libraries (β2, Perez-Reyes et al., 1992; β3, Castellano et al., 1993a; β4, Castellano et al., 1993b). In terms of sequence content, β-subunits share two conserved central regions amounting to more than half of the total peptide sequence (domains D2 and D4), a nonconserved linker between the two conserved domains (D3), and nonconserved N- and C-termini (domains D1 and D5, respectively) (Perez-Reyes and Schneider, 1994). The main interaction of β-subunits with α1 pore subunits is via a conserved ∼30-residue β-interaction domain present in domain D4 that binds with high affinity to the cytosolic loop between repeats I and II of the α1 subunit (Pragnell et al., 1994; De Waard et al., 1994). However, secondary interactions with other loops of pore subunits have been documented, especially for the neuronal α1A isoform (Walker et al., 1998). In terms of domain homology, β-subunits are related to the membrane-associated guanylate kinase superfamily, commonly engaged in membrane signaling. All members of this family have PDZ, SH3, and guanylate kinase homology domains which, in β-subunits, are present in the conserved D2 and D4 regions (Hanlon et al., 1999).

Structure-function studies have suggested roles for β-subunits in three distinct areas of DHPR function. First, β-subunits increase surface expression of Ca2+ channels; hence, this protein is vital for trafficking the newly synthesized DHPR out of perinuclear sites (Chien et al., 1995; Neuhuber et al., 1998; Bichet et al., 2000). Second, β-subunits modulate the kinetics of the L-type Ca2+ current (Qin et al., 1998; Wei et al., 2000; Berrou et al., 2001) and increase the coupling between S4 charge movements and pore opening (Neely et al., 1993; Kamp et al., 1996; Olcese et al., 1996). Finally, the β1a subunit is required for the voltage dependent triggering of Ca2+ transients in skeletal muscle, suggesting that β-participates in coupling charge movements to the opening of RyR1 (Beurg et al., 1999a,b; Sheridan et al., 2002). Studies in HEK cells, aiming to identify the molecular basis of the transport function of β2a, showed that neither D1 nor D5 was essential for the surface expression of Ca2+ channels formed by α1C or for the expression of DHP binding sites accessible from the outside of the cell (Gao et al., 1999). However, mutations in the β-interaction domain region and the nearby SH3 region abolished surface expression (Chien et al., 1998). Hence, a strong α1/β interaction is vital for the survival of the newly synthesized Ca2+ channel. In terms of the functional identity of other domains present in the β-subunit, the N-terminus in domain D1 is a critical determinant of the rate and voltage dependence of activation of Ca2+ channels formed by the α1E isoform (Olcese et al., 1994). A second region in domain D3 selectively affected inactivation independent of β-effects on activation (Qin et al., 1996). Furthermore, the C-terminus region of β1a (domain D5) is a critical determinant of the EC coupling function of the DHPR in skeletal myotubes (Beurg et al., 1999a,b; Sheridan et al., 2002).

A second critical regulator of DHPR function is RyR1 itself. Studies in RyR1 KO myotubes have shown that approximately half of the DHPR charge movements and DHP binding sites are lost when RyR1 is eliminated. However, the Ca2+ current density is depressed much more severely, close to10-fold (Nakai et al., 1996; Buck et al., 1997; Avila and Dirksen, 2000). Expression of the DHPR Ca2+ current has been suggested to be under the specific control of RyR1 by a so-called retrograde signal, from RyR1 to the DHPR (Nakai et al., 1998). The nature of this retrograde signal is probably structural in origin because full Ca2+ current recovery was observed in RyR KO myotubes expressing RyR1 mutants strongly deficient in voltage-dependent EC coupling (Avila et al., 2001). However, full charge movement recovery in the RyR1 KO myotube did not occur with the EC coupling deficient RyR1 mutant, requiring instead an entirely functional RyR1 (Avila et al., 2001). Thus, the contribution of RyR1 to DHPR expression is complex and presumably involves modulatory effects via protein-protein interactions as well as Ca2+ signaling mediated by RyR1. In contrast to the strict requirements for RyR1 in the skeletal myotube, studies in amphibian oocytes have shown that skeletal Ca2+ current expression can be achieved by a specific combination of skeletal (α1S, α2δ, γ1) and neuronal (β1b) subunits (Ren and Hall, 1997; Morrill and Cannon, 2000). The reasons why the DHPR Ca2+ current would require a retrograde signal from RyR1 in the skeletal myotube but this signal would be bypassed in the heterologous oocyte system are entirely unclear at this point. This discrepancy suggests that in the skeletal myotube, Ca2+ current regulation is multifactorial, and perhaps it represents a balance of positive and negative interactions within the DHPR and between the DHPR and other muscle proteins.

In this study, we investigated the charge movement and Ca2+ current characteristics donated to this complex by β1a, the endogenous variant known to form part of the skeletal DHPR (Ruth et al., 1989), and by β2a (Perez-Reyes et al., 1992; Qin et al., 1998), which is a variant expressed in the heart and brain but not in skeletal muscle (Perez-Reyes and Schneider, 1994). Studies were conducted in RyR1 KO, β1 KO, and double KO myotubes generated by interbreeding mice heterozygous for the β1 KO and RyR1 KO alleles. The data indicate that in the absence of RyR1, β2a had a preferential ability to recover a DHPR that expressed Ca2+ currents at a high density and charge movements at a low density. Conversely, β1a had a preferential ability to recover a DHPR that expressed charge movements at a high density and Ca2+ currents at a low density. Thus, the β-subunit of the skeletal DHPR appears to be intimately involved in the cellular mechanisms that differentially regulate charge movements and Ca2+ current expression in the skeletal myotube. Part of this work has been previously published in abstract form (Ahern et al., 2002).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of genotypes

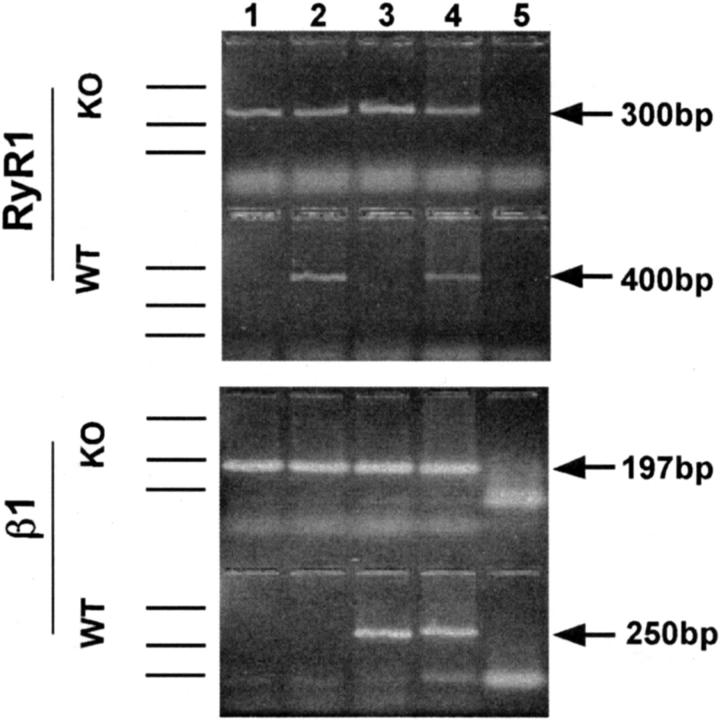

We used PCR to screen for the wild-type (WT) and knock-out (KO) alleles of the DHPR β1 and RyR1 genes in mice with targeted disruptions of these genes (Gregg et al., 1996; Nakai et al., 1996). Tail samples from E18 fetuses were digested with Proteinase K (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and the DNA was then isolated following the Puregene animal tissue protocol (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The PCR reactions for each sample were composed of 11.7 μL distilled water, 1 μL of each 20 μM primer, 3.2 μL of 1.25 mM dNTPs (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX), 2 μL 10× PCR buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), 12 μL Taq polymerase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and 1 μL of the DNA solution (∼100 μg/mL). PCR primers 5′ gga ctg gca aga gga ccg gag 3′ and 5′ gga agc cag ggc tgc agg tga gc 3′ were used to amplify a 400 bp fragment of the WT RyR1 allele. PCR primers 5′ gga ctg gca aga gga ccg gag 3′ and 5′ cct gaa gaa cga gat cag cag cct ctg ttc c 3′ were used to amplify a 300 bp fragment of the KO RyR1 allele. The following conditions applied for the PCR of the RyR1 alleles: 1) 5 min and 30 s at 94°C, 2) 1 min at 94°C, 3) 1 min at 55°C, 4) 1 min at 72°C, 5) cycle through steps 2–4 for 30 times, and 6) 10 min at 72°C. PCR primers 5′ cta gga gaa tgg atg gta gat gg 3′ and 5′ aca ccc cct gcc agt ggt aag agc 3′ were used to amplify a 250 bp fragment of the WT β1 allele. PCR primers 5′ aca ccc cct gcc agt ggt aag agc 3′ and 5′ aca ata gca ggc atg ctg ggg atg 3′ were used to amplify a 197 bp fragment of the KO β1 allele. The following conditions apply for the PCR of the DHPR β1 alleles: 1) 2 min at 94°, 2) 30 s at 94°C, 3) 45 s at 55°C, 4) 1 min at 72°C, 5) cycle through steps 2–4 for 30 times, and 6) 10 min at 72°C.

Myotube primary cell cultures

Cell cultures of myotubes were prepared from hind limbs of E18 mice as described (Beurg et al., 1997). Myoblasts were isolated by enzymatic digestion with 0.125% (w/v) trypsin and 0.05% (w/v) pancreatin. After centrifugation, mononucleated cells were resuspended in plating medium containing 78% Dulbeccos's modified Eagle's medium with low glucose (DMEM), 10% horse serum, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 2% chicken serum extract. Cells were plated on plastic culture dishes coated with gelatin at a density of ∼1 × 104 cells per dish. Cultures were grown at 37°C in 8% CO2 gas. After the fusion of myoblasts (5–7 days), the medium was replaced with FBS-free medium, and CO2 was decreased to 5%.

cDNA transfection

Cell transfection was performed during myoblast fusion with the polyamine LT1 (Panvera). Cells were exposed for 2–3 h to a transfection solution containing LT1 and cDNA in a 5:1 μl/μg ratio. All cDNAs of interest, with the exceptions of RyR1 and CD8-β2a C3,4S, were subcloned in the mammalian expression vector pSG5 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The RyR1 cDNA was subcloned in the pCl-neo expression vector (Promega, Madison, WI) as described (Nakai et al., 1996). The CD8-β2a C3,4S construct is described below. The expression plasmid was cotransfected with a plasmid encoding the T-cell surface glycoprotein CD8A used as a transfection marker. Transfected cells were identified with micron-size polystyrene beads coated with a monoclonal antibody against an external CD8A epitope (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). The efficiency of cotransfection of the marker and the cDNA of interest was ∼80%.

Full-length cDNAs

All cDNAs were N-terminus tagged by in-frame fusion of the first 11 amino acids of the phage T7 gene 10 protein in the pSG5 vector. GenBank accession numbers for the full-length sequences utilized in the present study were as follows: mouse β1a residues 1–524 (NM_031173), mouse β1b residues 1–596 (AY094173), mouse β1c residues 1–480 (AY094172), rat β2a residues 1–604 (M80545), rat β3b residues 1–485 (M88751), and rat β4 residues 1–519 (L02315). All cDNA constructs were sequenced at least twice at a campus facility.

β1a deletion constructs

Two oligonucleotide primers were designed to encompass the region of interest. Each primer had 20–25 bases identical to the original sequence and an additional 10–15 bases that resulted in an amplified product with an AgeI site at the 5′ end and a stop codon and NotI restriction site at the 3′ end. The PCR products were subcloned into the pCR-Blunt vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), excised by digestion with AgeI and NotI, and cloned into pSG5.

β1aΔ1–57

PCR primers 5′ gcat gac cgg tgg aca gca aat ggg tgg ctc agc aga gtc cta cac 3′ and 5′ gcg gcc gct agc tac cta cat ggc gtg ctc ctg agg 3′ were used to generate a cDNA that contains amino acids 58–524 of the β1a cDNA. This cDNA was fused in frame to the first 11 amino acids of the phage T7 gene 10 protein in the pSG5 vector.

β1aΔ490–524

PCR primers 5′ gca tga ccg gtg gac agc aaa tgg gta tgg tcc aga aga gcg gca tgt ccc ggg gcc 3′ and 5′ ggg gcg gcc gct cac tgg agg ttg gag acg ggg gca 3′ were used to generate a cDNA that contains amino acids 1–489 of the β1a cDNA. This cDNA was fused in frame to the first 11 amino acids of the phage T7 gene 10 protein in the pSG5 vector.

Cysteine substitution constructs

β1a Q3C, K4C

Forward primer 5′ acc ggt gga aca gca aat ggg tat ggt ctg ctg cag ggg cat g 3′ and reverse primer 5′ att gta gcc aac att tgt ccg aac agc 3′ were used to introduce nucleotides for cysteines at residue positions three and four in the β1a template. Primers (10 pmol each), 20 pmol dNTPs, 20 ng T7-β1a-pSG5 template, and 0.5 μl Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) were combined and cycled at 95°C for 5 min then 95°C for 2 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles ending with 10 min at 72°C. The PCR product was ligated into pCR 2.1 TA vector (Stratagene, Carlsbad, CA). This cDNA was then inserted into T7-β1a-pSG5 via unique AgeI and XhoI sites.

β2a C3,4S

Forward primer 5′ acc ggt gga cag caa atg gta tgc agt cct ccg ggc 3′ and reverse primer 5′ cat atc tgt gac ctc ata cc 3′ were used to introduce nucleotides for serines at residue positions three and four in the β2a template. Primers (10 pmol each), 20 pmol dNTPs, 20 ng T7-β2a-pSG5 template, and 0.5 μl Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) were combined and cycled at 95°C for 5 min then 95°C for 2 min, 55°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles finishing with 10 min at 72°C. The PCR product was cloned into pCR 2.1 TA vector (Stratagene, Carlsbad, CA). This cDNA was then inserted into T7-β2a-pSG5 via unique AgeI and Acc65I sites.

Chimeric β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 (β2a 1–287/β1a 325–524)

This construct contains amino acids 1–287 of β2a fused to the N-terminus of amino acids 325–524 of β1a and was made by two rounds of PCR. Primers 5′ gca tga ccg gtg gac agc aaa tgg gta tgc agt gct gcg ggc tgg ta 3′ (A) and 5′ gag cgt ttg gcc agg gag atg tca gca 3′ (B) were used to PCR the 5′ end of the full-length β1a cDNA. Primers 5′ tcc ctg gcc aaa cgc tcc gtc ctc aac 3′ (C) and 5′ gcg gcc gct agc tac cta cat ggc gtg ctc ctg agg 3′ (D) were used to PCR the 3′ end of the full-length β1a cDNA. The primers were designed to produce a 17 bp overlap of identical sequence. The two PCR products were electrophoresed on agarose gels, excised from the gel, and eluted using GenElute columns (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA). The two PCR products were mixed in an equimolar ratio, denatured, allowed to reanneal, and used in a PCR reaction to amplify the chimeric fragments with primers A and D. This cDNA was fused in frame to the first 11 amino acids of the phage T7 gene 10 protein in the pSG5 vector.

Chimeric β2aD1β1aD2–5 (β2a 1–16/β1a 58–524)

This construct contains amino acids 1–16 of β2a cDNA fused to the N-terminus of amino acids 58–524 of β1a cDNA and was made by one round of PCR. Forward primer 5′ gga tcc atg cag tgc tgc ggg ctg gta cat cgc cgg cga gta cgg gtc cgc cag ggc tca gc 3′ encodes a portion of the N-terminal T7 tag, the first 16 residues of β2a and β1a residues 58–67. This “overhang” primer was combined with reverse primer 5′ att gta gcc aac att tgt ccg aac agc 3′ to produce the chimeric construct containing domain D1 of β2a fused to domain D2 to D5 of β1a. Primers (10 pmol each), 20 pmol dNTPs, 20 ng T7-pSG5-β1a template, and 0.5 μl Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) were combined and cycled at 95°C for 5 min then 95°C for 2 min, 55°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles ending with 10 min at 72°C. The PCR product was cloned into pCR 2.1 TA vector (Stratagene). This cDNA was then inserted into the T7-β1a-pSG5 vector via unique AgeI and XhoI sites.

Chimeric β1aD1–D3β2aD4,5 (β1a 1–325/β2a 287–604)

This construct contains amino acids 1–325 of β1a cDNA fused to the N-terminus of amino acids 287–604 of β2a cDNA and was made by two rounds of PCR. In the first round, the β1a cDNA fragment was amplified by the forward primer 5′ caa gac tag cgt gag cag tgt cac c 3′ (A) encoding residues 240–247 of β1a and the reverse primer 5′ gtg ttg gat ctt tct atg acg gag cgt ttg 3′ (B), which encodes residues 321–325 of β1a and residues 287–292 of β2a. The β2a cDNA fragment was amplified by the forward primer 5′ ata gaa aga tcc aac aca agg tcg agc 3′ (C) encoding residues 287–295 of β2a and the reverse primer 5′ aag ctg caa taa aca agt tct gc 3′ (D) which is homologous to the pSG5-T7 vector sequence. The first two PCR products were mixed after purification with QIAquick PCR purification columns (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), and were annealed and extended by Taq polymerase in the absence of primers (95°C for 2 min, then 95°C for 1 min, 43°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min for 5 cycles). Afterward, primers A and D were added to the PCR mixture and the reaction was continued at 95°C for 1 min, 65°C for 1 min, and then 72°C for 1 min for 25 cycles ending with 10 min at 72°C. The final PCR product was subcloned into pCR 2.1 TA vector (Stratagene). This cDNA was then inserted into the T7-β1a-pSG5 vector via unique PmlI and NotI sites.

Chimeric β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5 (β2a C3,4S 1–287/β1a 325–524)

This construct contains amino acids 1–287 of β2a fused to the N-terminus of amino acids 325–524 of β1a with cysteines substituted for serines at positions three and four of β2a. Forward primer 5′ acc ggt gga cag caa atg gta tgc agt cct ccg ggc 3′and reverse primer 5′ cat atc tgt gac ctc ata cc 3′ were used to introduce nucleotides for serines at residue positions three and four in the chimeric β2a 1–287/β1a 325–524 template. Primers (10 pmol each), 20 pmol dNTPs, 20 ng T7-pSG5-β2a template, and 0.5 μl Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) were combined and cycled at 95°C for 5 min then 95°C for 2 min, 55°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles finishing with 10 min at 72°C. The PCR product was cloned into pCR 2.1 TA vector (Stratagene). This cDNA was then inserted into T7-β2a 1–287/β1a 325–524-pSG5 vector via unique AgeI and Acc65I sites.

Chimeric CD8-β2a C3,4S

This construct was described previously (Restituo et al., 2000). Residues 1–209 of the human CD8A surface glycoprotein (accession number NM_001768) were fused in-frame to the N-terminus of β2a C3S,C4S in expression vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The N-terminus of CD8 has an external epitope recognized by anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody 5C2 adsorbed on polystyrene Dynabeads M-450 (Dynal).

Sequence alignment

Alignment of mouse β1a (NM_031173) and rat β2a (M80545) peptide sequences was performed with DNASTAR (Madison, WI) using the Jotun Hein method and an identity residue weight table. Other alignment methods and residue weight tables also produced similar results. Based on this alignment, domain D1 corresponds to residues 1–57 of β1a and residues 1–16 of β2a with a similarity of 41.2%; D2 corresponds to residues 58–198 of β1a and residues 17–157 of β2a with a similarity of 78.2%; D3 corresponds to residues 199–253 of β1a and residues 158–205 of β2a with a similarity of 36.7%; D4 corresponds to residues 254–477 of β1a and residues 206–429 of β2a with a similarity of 90.6%; and D5 corresponds to residues 478–524 of β1a and residues 430–604 of β2a with a similarity of 21.7%.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp

Cells were voltage-clamped 3–5 days after transfection. Transfected cells revealed by CD8 beads were voltage-clamped with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and a Digidata 1200 (Axon Instruments) pulse generator and digitizer. Linear capacitance, leak currents, and effective series resistance were compensated with the amplifier circuit. The charge movement protocol included a long pre-pulse to eliminate immobilization-sensitive gating currents. Voltage was stepped from a holding potential of −80 mV to −30 mV for 700 ms, then to −50 mV for 5 ms, then to the test potential for 50 ms, then to −50 mV for 30 ms, then to −80 mV. Test potentials were applied in decreasing order every 10 mV from +100 or +110 mV to −70 mV. The intertest pulse period was 10 s. Subtraction of the linear charge was done online with a P/4 procedure. The P/4 pulses were delivered immediately before the protocol from −80 mV in the negative direction. The P/4 pulses adequately subtracted the linear component of the charging current, in the range of −80 to −120 mV. In this range, the membrane capacity varied linearly with voltage, within a 0.5% error.

Solutions

The external solution in all cases was (in mM) 130 TEA methanesulfonate, 10 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES titrated with TEA(OH) to pH 7.4. For Ca2+ currents, the pipette solution was (in mM) 140 Cs+-aspartate, 5 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, and 10 MOPS-CsOH, pH 7.2. For charge movements, the pipette solution was (in mM) 120 NMG (N-methyl glucamine)-glutamate, 10 HEPES-NMG, 10 EGTA-NMG, pH 7.3 (Ahern et al., 2001b). For charge movements, the external solution was supplemented with 0.5 mM CdCl2, 0.5 mM LaCl3, and 0.05 mM TTX to block residual Na+ current. For Ca2+ transients, the pipette solution was (in mM) 140 Cs+-aspartate, 5 MgCl2, 0.1 EGTA, and 10 MOPS-CsOH, pH 7.2.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy

Confocal line scan measurements were performed as described previously (Conklin et al., 1999). Cells were loaded with 4 μM fluo-4 acetoxymethyl (AM) ester (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 60 min at room temperature. All experiments were performed at room temperature. Cells were viewed with an inverted Olympus microscope with a 20× objective (N.A. = 0.4) and an Olympus Fluoview confocal attachment (Melville, NY). A 488 nm spectrum line for fluo-4 excitation was provided by a 5 mW Argon laser attenuated to 20% with neutral density filters. Line scans consisted of 1,000 lines, each of 512 pixels, acquired at a rate of 2.05 ms per line. Line scans were synchronized to start 100 ms before the onset of the depolarization. The time course of the space-averaged fluorescence intensity change was estimated as follows. The pixel intensity was transformed into arbitrary units, and the mean intensity was obtained by averaging pixels covering the cell exclusively. The mean resting fluorescence intensity, Fo, corresponds to the mean intensity of each line in the line scan averaged over the first 100 ms before stimulation. The change in mean intensity above rest, ΔF, was obtained by subtraction of Fo from the mean intensity of each line in the line scan. ΔF for each line in a line scan was divided by Fo and the ratio ΔF/Fo was plotted as a function of time. To construct peak Ca2+ fluorescence versus voltage curves, we used the highest ΔF/Fo line value after the onset of the pulse and up to the termination of the pulse. Image analysis was performed with NIH Image software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). To obtain reliable Ca2+ transient versus voltage curves, seven step depolarizations of 50 ms were applied in descending order (from +90 mV to −30 mV) from a holding potential of −40 mV. Between each depolarization, the cell was maintained at the resting potential for 30 s to permit recovery of the resting fluorescence.

Curve fitting

The voltage dependence of charge movements (Q), Ca2+ conductance (G), and peak fluorescence ΔF/Fo was fitted according to a Boltzmann distribution (Eq. 1), namely A = Amax/(1+exp(−(V−V1/2)/k), where Amax is Qmax, Gmax, or ΔF/Fo max; V1/2 is the potential at which A = Amax/2; and k is the slope factor. The statistic of Boltzmann parameters (Amax, V1/2, k) were obtained by fitting curves to individual cells and are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The figures show the fit of the mean Amax of all cells with the number of cells shown in Tables 1 and 2. The statistical analyses were performed with Analyse-it software (Analyse-It Software, Leeds, UK).

TABLE 1.

Ca2+ conductance and charge movements of myotubes expressing β1a or β2a

| G-V curve

|

Q-V curve

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gmax (pS/pF) | V1/2 (mV) | k (mV) | Qmax (fC/pF) | V1/2 (mV) | k (mV) | |

| β1/RyR1 KO | — | — | — | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 6.6 ± 6 | 16.3 ± 1.6 |

| NT | (10) | (6) | ||||

| β1a | 33.7 ± 7.3 | 17.6 ± 1.5 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.4a | 14.3 ± 4 | 16.7 ± 1.7 |

| (6) | (6) | |||||

| β2a | 115 ± 18.2b | 11.9 ± 3.8 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.4a | 18.9 ± 2.8 | 14.6 ± 0.9 |

| (7) | (5) | |||||

| RyR1 KO | 37.1 ± 5.2 | 12.4 ± 2.4 | 6.3 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 15.7 ± 3.2 | 16.6 ± 0.8 |

| NT | (14) | (13) | ||||

| β1a | 35.5 ± 9.9 | 9.9 ± 3.7 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 20.5 ± 3.7 | 26.1 ± 1.4a |

| (10) | (5) | |||||

| β2a | 195.4 ± 16a | 10.8 ± 1.3 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 12.8 ± 3.4 | 18.2 ± 1.4 |

| (15) | (6) | |||||

| β1KO | — | — | — | 1.9 ± 0.3 | −1.1 ± 2.4 | 15.8 ± 1.8 |

| NT | (15) | (5) | ||||

| β1a | 158 ± 21.4 | 0.4 ± 2.6 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.7a | 24.7 ± 5.2a | 20.1 ± 1.9 |

| (7) | (4) | |||||

| β2a | 170 ± 14.1 | 13.6 ± 1b | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 15.4 ± 7.8a | 19.0 ± 1.7 |

| (11) | (8) | |||||

Entries correspond to mean ± SE of Boltzmann parameters fitted to each cell according to Eq. 1. The number of cells is in parentheses. Indicated are parameters of nontransfected (NT), wild-type β1a- and wild-type β2a- transfected myotubes with genotypes β1/RyR1 KO, RyR1 KO, and β1 KO. a indicates parameters compared to NT of each genotype (with the exception of conductance parameters of β1 KO and β1/RyR1 KO) with t-test significance p < 0.05. For conductance parameters of β1 KO and β1/RyR1 KO myotubes, b indicates data of β1a-transfected compared to β2a-transfected myotubes with t-test significance p < 0.05.

TABLE 2.

Ca2+ conductance of myotubes expressing DHPR β-chimeras

| RyR1 KO

|

β1 KO

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gmax (pS/pF) | V1/2 (mV) | k (mV) | Gmax (pS/pF) | V1/2 (mV) | k (mV) | |

| β2a C3,4S | 59.8 ± 3.9a | 18.6 ± 2.1a | 6 ± 0.3 | 166.4 ± 17.9 | 15.2 ± 2.3 | 4.1 ± 0.4 |

| (12) | (6) | |||||

| CD8-β2a C3,4S | 161 ± 16.7 | 22 ± 1.3a | 6 ± 0.5 | 195.8 ± 12.7 | 20.9 ± 0.5b | 5.3 ± 0.3 |

| (8) | (6) | |||||

| β1a Q3C, K4C | 49 ± 4.6a | 28.1 ± 3.5a | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 237.8 ± 8.8b | 30 ± 1.4b | 6.5 ± 0.4b |

| (6) | (8) | |||||

| β2aD1 β1a D2–5 | 55.1 ± 4.5a | 25.3 ± 2.5a | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 232.8 ± 14.6 | 22.8 ± 1.3b | 4.8 ± 0.5 |

| (5) | (5) | |||||

| β2aD1–3 β1a D4,5 | 173.4 ± 14 | 9.2 ± 2.4 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 225.7 ± 22.4 | 11.5 ± 2.6 | 4.2 ± 0.5 |

| (7) | (6) | |||||

| β2aC3,4S D1–3 β1a D4,5 | 64.5 ± 7.3a | 23.9 ± 1.4a | 6.6 ± 0.5a | 230 ± 30 | 13.3 ± 1.8 | 4.4 ± 0.4 |

| (8) | (5) | |||||

Entries correspond to mean ± SE of Boltzmann parameters fitted to each cell according to Eq. 1. The number of cells is in parentheses. Constructs were expressed in either RyR1 KO myotubes or β1 KO myotubes. a and b indicate parameters with ANOVA significance p < 0.05 compared to Ca2+ conductance parameters of wild-type β2a in RyR 1 KO (a) or β1 KO (b) myotubes. Parameters of β2a expression are shown in Table 1.

RESULTS

Studies were conducted in cultured myotubes from E18 fetuses that were either null for the DHPR β1 gene, the RyR1 gene, or both genes. To generate double null mice, we interbred mice heterozygous of the β1 KO allele (β1WT/KO, Gregg et al., 1996) with mice heterozygous for the RyR1 KO allele (RyR1WT/KO, Nakai et al., 1996). Double heterozygous F1 mice (β1WT/KO RyR1WT/KO) were phenotypically normal and, when interbred, generated an F2 progeny consisting of normal and paralytic fetuses. At E18, F2 fetuses with a β1 KO or RyR1 KO phenotype were identified by the absence of movement when prodded and by the curved features of the spine reported previously (Gregg et al., 1996; Nakai et al., 1996). Paralytic F2 fetuses were each separately processed for myotube cell culture while a PCR screen was conducted in parallel. Fig. 1 shows the genotype of three paralytic littermates (lanes 1, 2, and 3) and a parent (lane 4) screened for the wild-type (WT) and knock-out (KO) alleles of the two genes. A β1/RyR1 KO was identified in lane 1 based on the amplification of DNA fragments from both KO alleles but not from the WT alleles. Lane 2 shows a β1 KO (β1KO/KO) heterozygous for the RyR1 allele (RyR1WT/KO), while lane 3 shows the genotype of a RyR1 KO (RyR1KO/KO) heterozygous of the β1 KO allele (β1WT/KO). From a total of 102 paralytic E18 fetuses, we identified a total of 11 β1/RyR1 KO fetuses, which amounts to 1 double KO in 9.23 paralytic littermates. This result was consistent with the predicted odds of 1 β1/RyR1 KO out of 7 paralytic littermates from an F2 progeny, assuming independent allele segregation. In the text and figures, β1/RyR1 KO, β1 KO, and RyR1 KO identify the genotype β1KO/KO RyR1KO/KO, β1KO/KO RyR1WT/WT, and β1WT/WT RyR1KO/KO, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Genotype of β1/RyR1 KO mice obtained by PCR. DNA fragments amplified with genotype-specific primers are shown on two separate 3% agarose gels. Each gel shows two sets of PCR reactions, each for a specific allele (top: RyR1 KO, RyR1 WT; bottom: β1 KO, β1 WT). Indicated on the left are three size markers (500, 200, and 100 bp) of a total of six markers run in each gel. Indicated by arrows are the expected sizes of the amplified DNA for each reaction. Templates used were total DNA of three paralytic littermates (lanes 1–3), a double heterozygous parent (lane 4), and a control reaction without template (lane 5).

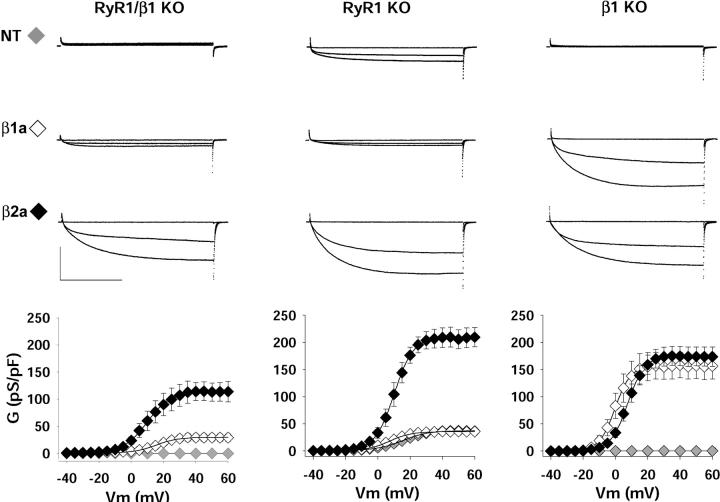

β1/RyR1 KO myotubes were cultured and transfected with either the endogenous isoform β1a or rat β2a, which, among many tested β variants from the four gene families (described below), had the unique ability to stimulate Ca2+ current expression in the absence of RyR1. Fig. 2 shows Ca2+ currents expressed by the two isoforms in β1/RyR1 KO, RyR1 KO, and β1 KO myotubes. The data correspond to whole-cell Ca2+ currents elicited by 500-ms depolarizations to −10, +10, and +30 mV from a holding potential of −40 mV. Conductance versus voltage relationships are shown immediately below the Ca2+ currents for the three transfection conditions, namely nontransfected (gray symbols), β1a-transfected (white symbols), or β2a-transfected (black symbols). The complete pulse protocol utilized for fitting conductance versus voltage curves consisted of step depolarizations from −35 mV to +60 mV every 5 mV. We found that nontransfected (labeled NT) β1/RyR1 KO and β1 KO myotubes had no detectable Ca2+ currents. In our hands, the limit of Ca2+ current detection was ∼20 pA/cell. A background Ca2+ current of low density was previously reported in intercostal muscle fibers dissociated from E18 β1 KO fetuses (Strube et al., 1996). However, this current component was far less frequent in cell cultures of limb myotubes (Strube et al., 1998) and was entirely absent here. The null background could possibly be related to changes in the genetic background because the colony was constantly regenerated by outbred mice to avoid a reduction of the litter size. If β1/RyR1 KO myotubes are null for both genes, overexpression of the missing β1a subunit should restore the phenotype of the RyR1 KO myotube. In β1a-expressing β1/RyR1 KO myotubes, we consistently detected a low-density Ca2+ current with an average Gmax of 34 ± 7 pS/pF (n = 6) shown in the left column of Fig. 2. This density was similar to that of nontransfected RyR1 KO myotubes shown in the center column of Fig. 2 (37 ± 5 pS/pF, n = 14). Thus, β1a overexpression in the double KO recovered the RyR1 KO phenotype, and furthermore, the Ca2+ current density of RyR1 KO myotubes was similar to that in previous reports (Avila and Dirksen, 2000; Ahern et al., 2001b). Averages of Boltzmann parameters fitted to the conductance versus voltage curve of each cell and the statistical significance of the data are shown in Table 1. β1a overexpression in RyR1 KO and β1 KO myotubes is shown in the center and right columns of Fig. 2. We found that β1a failed to increase the Ca2+ current density of the RyR1 KO myotube but recovered an entirely normal (WT) density in the β1 KO myotube. In the latter case, the Gmax was 158 ± 21 pS/pF (n = 7) and was consistent with previous reports from our laboratory (Beurg et al., 1997; 1999a,b). The positive result in the β1 KO myotube indicated that the expression vector and transfection procedures were adequate for Ca2+ current expression. Therefore, the low functional expression in the β1/RyR1 KO and RyR1 KO myotubes were likely due to the specific absence of RyR1. Additionally, the studies with β1a validated the genotype of the double KO myotube entirely. If myotubes assigned as β1/RyR1 KO were in fact β1 KO but RyR1WT/WT, β1a overexpression in the misidentified β1/RyR1 KO myotubes should have rescued a high-density Ca2+ current similar to that seen by β1a overexpression in β1 KO myotubes (Fig. 2, right column). However, this was not the case. If, on the other hand, myotubes assigned as β1/RyR1 KO were in fact RyR1 KO but β1WT/WT, the low-density Ca2+ current of ∼30 pS/pF present in RyR1 KO myotubes (Fig. 2, center column) should have been observed in the nontransfected misidentified β1/RyR1 KO myotubes. Again, this was not the case.

FIGURE 2.

DHPR Ca2+ currents in β1/RyR1 KO, RyR1 KO, and β1 KO myotubes. Ca2+ currents are shown in response to 500-ms voltage steps to −10, +10, and +30 mV from a holding potential of −40 mV. Nontransfected (NT), β1a-expressing, or β2a-expressing myotubes are shown in the top, middle and bottom rows, respectively. Scale bars are 1 nA and 200 ms. The graphs show the voltage dependence of the Ca2+ conductance calculated from the maximal current during the pulse and the reversal potential obtained by extrapolation. Symbols show the mean Ca2+ conductance density (± SE) for the number of cells indicated in Table 1. The mean was fitted according to Eq. 1. The parameters of the fit with Gmax in pS/pF, V1/2 in mV, and k in mV are as indicated below. For β1/RyR1 KO myotubes 29.8, 14.8, 7.4 for β1a-transfected; and 114.8, 9.7, 7.5 for β2a-transfected. For RyR1 KO myotubes 37.8, 15.0, 8.6 for NT; 35.8, 7.1, 7.1 for β1a-transfected; and 196.7, 10.8, 5.1 for β2a-transfected. For β1 KO myotubes 156.6, −0.3, 4.9 for β1a-transfected; and 174.8, 7.5, 5.3 for β2a-transfected.

Overexpression of β2a in the β1 KO myotube was shown previously to restore the L-type Ca2+ current (Beurg et al., 1999a,b). We therefore became interested in determining if a hybrid DHPR containing β2a could be kept under retrograde control by RyR1. If this was the case, β2a should not restore high-density Ca2+ currents in the absence of RyR1. The right column of Fig. 2 confirmed the previous result showing that β2a can readily replace β1a and express a high-density Ca2+ current in the β1 KO myotube. In β1/RyR1 KO and RyR1 KO myotubes, β2a recovered Ca2+ currents with a density four- to sixfold larger than those recovered by β1a (Fig. 2 left and center columns). The result in the RyR1 KO myotube was particularly compelling because the maximal Ca2+ conductance stimulated by β2a, after discounting the Ca2+ conductance of the nontransfected myotube, was approximately the same as in the β2a-expressing β1 KO myotube. Thus, Ca2+ currents recovered by β2a had readily bypassed the inhibition imposed by the absence of RyR1. Moreover, the presence of β1a in the RyR1 KO myotube did not interfere with the ability of β2a to bypass current inhibition. We noticed that the maximal Ca2+ conductance recovered by β2a was lower in β1/RyR1 KO than in RyR1 KO myotubes. To understand this situation better, we compared the Ca2+ conductance of the β2a-expressing double KO myotube to that of the double KO myotube reconstituted with the two missing homologous subunits. The Gmax generated by the combined expression of β1a and RyR1 in β1/RyR1 KO myotubes was 122 ± 22 pS/pF (n = 5), and this value was not significantly different from that of β2a-expressing β1/RyR1 KO myotubes (115 ± 18 pS/pF, n = 7; t-test significance p = 0.84). However, it was of significance to note that the Gmax of double KO myotubes expressing β1a and RyR1 was lower than the Gmax of the β1a-expressing β1 KO myotube (158 ± 21 pS/pF, n = 7) and the RyR1-expressing RyR1 KO myotube (177 ± 32 pS/pF, n = 6). In our hands, Ca2+ current recovery to levels present in wild-type myotubes required cDNA expression for 3–5 days when either RyR1 was expressed in the RyR1 KO myotube or β1a was expressed in the β1 KO myotube. This result agreed with a previous study of RyR1 expression in the RyR1 KO myotube where the post-transfection time required for Ca2+ current recovery was 3 to 6 days (Avila et al., 2001). It could be that the combined absence of both genes in double KO myotubes resulted in structural changes and/or changes in protein expression patterns in the nascent myotube, which are not easily reverted by post-addition of the missing cDNAs for 3–5 days. Presumably, longer expression times might be required in this case for full Ca2+ current recovery. However, the extensive growth of myotubes after the first week of cDNA expression and the inadmissibly high series resistance of myotubes kept in culture after 5 days precluded us from further investigating this possibility.

A higher Ca2+ current density recovered by β2a compared to β1a could reflect a better ability of β2a to traffic the DHPR to the cell surface. To determine if this was the case, we used gating currents to gauge the membrane density of DHPR voltage sensors. We have previously shown that a pore-forming DHPR generates as much gating current as a non pore-forming DHPR (Ahern et al., 2001a). Thus, the technique is impervious to the functional state of the Ca2+ channel, which is an important consideration in the present case. Fig. 3 shows intramembrane currents produced by the movement of charges in the expressed DHPR in response to 4 of 17 step voltages delivered to each cell (−30, +10, +50, and +90 mV) from a holding potential of −80 mV. The protocol included a 700-ms pre-test pulse depolarization to −30 mV to remove immobilization sensitive components of the gating current unrelated to the DHPR and pre-test P/4 pulses to eliminate linear components unrelated to voltage sensors. We found a good correspondence between the magnitude of the ON and OFF components, as would be expected if charge movements were due to reversible displacements of intramembrane charges. The graphs at the bottom of each column in Fig. 3 show charge versus voltage relationships for nontransfected and β1a- and β2a-expressing myotubes. The immobilization-resistant charge was obtained by integration of the OFF component which, in our hands, was less contaminated by ionic current than the ON component. The main contaminant of the ON component was a nonlinear outward current, presumably from a K+ channel, that was not always blocked by the pipette solution. In all cases, the OFF charge increased in a sigmoidal fashion starting at approximately −10 mV and saturated at potentials more positive than +60 mV, and data were adequately fit by a Boltzmann equation (Eq. 1) shown by the lines. In the β1/RyR1 KO myotube (Fig. 3, left column), we detected a small background charge with a maximal density of ∼1 fC/pF. Overexpression in these cells of β1a or β2a increased the maximal charge density threefold and twofold, respectively, and this difference was significant in each case (see Table 1). Thus, contrary to expectations based on Ca2+ current densities, the density of DHPR voltage sensors was lower in β2a-expressing than in β1a-expressing double KO myotubes. Overexpression of β1a in the double KO myotube reconstituted quantitatively the density of DHPR voltage sensors present in the nontransfected RyR1 KO myotube. This can be seen by comparing the charge versus voltage curves at the bottom of Fig. 3 (left plot open symbols versus center plot gray symbols) and the statistic of the Boltzmann parameters presented in Table 1. The Qmax of β1a-expressing β1/RyR1 KO myotubes was 3.3 ± 0.4 fC/pF, whereas the Qmax of nontransfected RyR1 KO myotubes was 3.9 ± 0.4 fC/pF, with the latter result in agreement with previous determinations (Avila and Dirksen, 2000). Interestingly, neither overexpression of β1a nor β2a rescued additional charge in the RyR1 KO myotube. β2a caused a slight reduction in Qmax relative to the nontransfected background, although this difference was not significant. The same pattern of charge recovery observed in the double KO was repeated in the β1 KO myotube (Fig. 3, right column). The maximal charge density in the β1a-expressing β1 KO myotube was higher than in β2a-expressing myotubes. However, due to the background charge present in nontransfected cells, the charge expressed by β1a, but not that by β2a, was significantly different from background (see Table 1). The Qmax of nontransfected β1 KO myotubes was ∼twofold higher than the Qmax of the β1/RyR1 KO myotube or that of the α1S-null dysgenic myotube (Ahern et al., 2001a). Such excess of charges is likely to arise from a low density of β1-less DHPR complexes transported to the surface, perhaps by residual levels of other beta isoforms present in the skeletal myotube. In summary, the intramembrane charge movement analyses did not provide evidence for a differential ability of β2a to promote transport and targeting of the DHPR to the cell surface. On the contrary, β2a was less effective than β1a in all three myotube genotypes analyzed.

FIGURE 3.

DHPR charge movements in β1/RyR1 KO, RyR1 KO, and β1 KO myotubes. Intramembrane currents are shown in response to 50-ms voltage steps to −30, +10, +50, and +90 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. Nontransfected (NT), β1a-expressing, or β2a-expressing myotubes are shown in the top, middle, and bottom rows, respectively. Scale bars are 0.5 nA and 25 ms. The graphs show the voltage dependence of the intramembrane charge obtained by integration of the OFF current. Symbols show the mean nonlinear charge density (± SE) for the number of cells indicated in Table 1. The lines are a fit of the mean according to Eq. 1. The parameters of the fit with Qmax in fC/pF, V1/2 in mV, and k in mV are: for β1/RyR1 KO myotubes 1.3, 18.5, 16.6 for NT; 3.1, 15.1, 17.3 for β1a-transfected; and 2.2, 16.7, 17.2 for β2a-transfected. For RyR1 KO myotubes 3.8, 16.2, 17.8 for NT; 3.4, 16.3, 23.4 for β1a-transfected; and 2.5, 12.1, 19.4 for β2a-transfected. For β1 KO myotubes 2.0, 1.6, 19.2 for NT; 4.6, 25.7, 19.2 for β1a-transfected; and 3.4, 15.6, 19.5 for β2a-transfected.

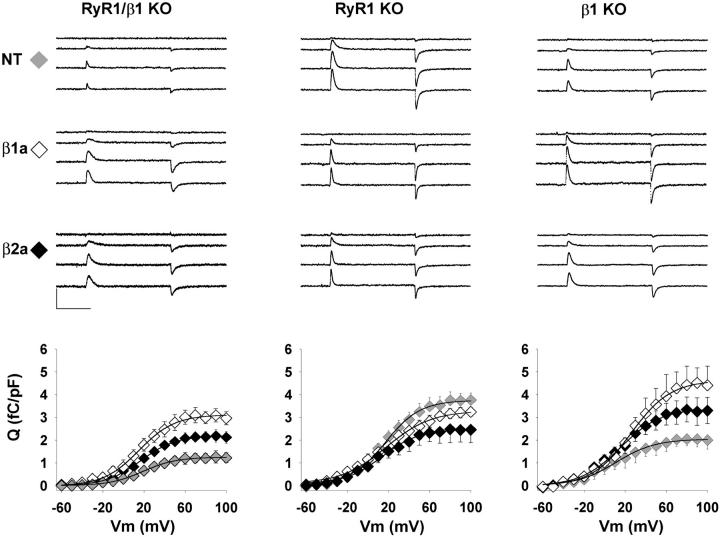

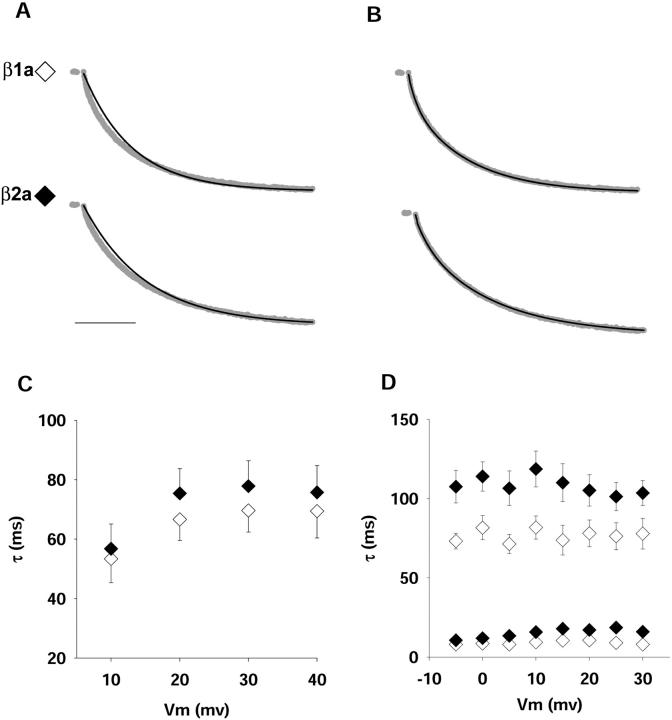

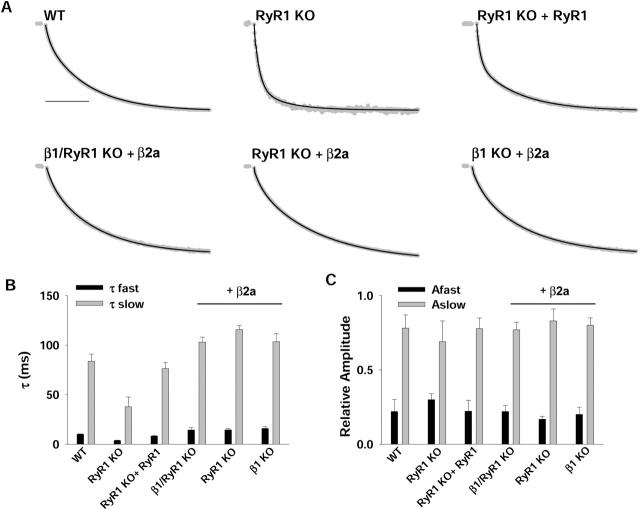

Evidence in favor of a direct interaction of the β2a isoform with the α1S pore subunit was obtained from the kinetics of activation of the expressed Ca2+ current. Previous studies in oocytes had shown that β2a is unique among splice variants of the four genes in that it reduced the rate of Ca2+ current inactivation of neuronal α1E channels, whereas all other variants had the opposite effect (Olcese et al., 1994; Qin et al., 1998). Here, we could not investigate the inactivation rate because the Ca2+ current of cultured myotubes inactivates very slowly, and in β1a-expressing β1 KO myotubes, the current is ∼10% inactivated at the end of a 1-s depolarization (Beurg et al., 1997). Longer pulses had deleterious effects on the pipette seal and, for that reason, were not attempted. Nevertheless, we found that β2a reduced the activation rate, which, to our knowledge, had not been documented previously for this variant. We investigated the activation kinetics in response to depolarizations of 500 ms, of which we omitted the first 10 ms due to incomplete compensation of the capacitative transient and fitted the remaining 490 ms as a first- or second-order process. Fig. 4 shows normalized whole-cell Ca2+ current (gray traces) during a depolarization to +30 mV from a holding potential of −40 mV in β1a- and β2a-expressing β1 KO myotubes. Based on a fit of the entire pulse current during a 1-second depolarization, we had previously concluded that the activation kinetics of the Ca2+ current in β1a-expressing β1 KO myotubes followed a monoexponential time course (Beurg et al., 1997). However, at a higher temporal resolution, we noticed that the early phase of the Ca2+ current activated faster than predicted by a monoexponential fit. Mono- and biexponential fits of the same data are shown by Figs. 4 A and 4 B, respectively. The biexponential fit was adequate to account for the fast-activating component, and the comparatively slower component evident at 100 ms or longer. A chi-square test (see the figure legend) confirmed the visual inspection. Furthermore, the voltage dependence of the activation time constant favored the biexponential representation. In the case of the monoexponential fit, the activation time constant increased with voltage, which would be unusual for a voltage gated channel. In contrast, τ(activation) for the slow and fast processes identified by the biexponential fit was essentially independent of voltage in the range of potentials investigated. Such a weak voltage dependence agreed with the activation kinetics reported in normal myotubes in the same range of potentials and at the same external Ca2+ concentration (Dirksen and Beam, 1995). Furthermore, Ca2+ current activation was previously reported to be a biexponential process in α1S-expressing dysgenic myotubes (Ahern et al., 2001b) and RyR1-expressing RyR1 KO myotubes (Avila and Dirksen, 2000). For all these reasons, we are confident that a biexponential representation of the data provides a more accurate description of the activation process. Fig. 5 A shows biexponential fits of normalized Ca2+ currents at the same potential recovered by β2a in the three myotube genotypes. For comparison, the figure also shows the fitted time course of the normal L-type Ca2+ current and the Ca2+ current of RyR1 KO and RyR1-expressing RyR1 KO myotubes. In agreement with previous results, the Ca2+ current of RyR1 KO myotubes activated faster than the normal Ca2+ current or that of RyR1-expressing RyR1 KO myotubes (Avila and Dirksen, 2000). In contrast, Ca2+ currents obtained by overexpression of β2a activated significantly slower in both the absence and the presence of RyR1. The slowing of the activation kinetics was manifested in the two components of activation (Fig. 5 C) and occurred without a change in the relative proportions of the two components (Fig. 5 D). The statistical analysis (see the figure legend) demonstrated that τ(slow) and τ(fast) were indistinguishable among the β2a-expressing β1/RyR1 KO, RyR1 KO, and β1 KO myotubes and were significantly larger than in RyR1 KO and RyR1-expressing RyR1 KO myotubes. Hence, the kinetics of activation of the β2a-mediated Ca2+ current had the unique feature of being noticeably slow and, in addition, was impervious to the presence or absence of RyR1. The kinetic analysis indicated that β2a could pair up with α1S and conferred unique activation kinetics to the skeletal DHPR Ca2+ channel.

FIGURE 4.

Kinetics of activation of Ca2+ currents in β1 KO myotubes expressing β1a or β2a. A, B) Ca2+ currents (gray line) were normalized according to the maximal current during the pulse. They were obtained in β1 KO myotubes transfected with β1a (top) or β2a (bottom) in response to a 500-ms voltage step to +30 mV from a holding potential of −40 mV. Scale bar is 100 ms. To fit the current during the pulse, the first 10 ms after the onset of the pulse was omitted. A) shows a monoexponential fit and B) shows a biexponential fit of the same data, with the fit indicated by the black line. Time constants of the monoexponential fit are 58.4 ms for β1a and 103.4 ms for β2a. Time constants of the biexponential fit are 7, 62.5 ms for β1a and 16.9, 119.2 ms for β2a. Relative contributions of the fast and slow components are 0.11, 0.89 for β1a and 0.15, 0.85 for β2a. Chi-square tests of the fit were as follows: χ2 = 0.026 for monexponential and χ2 = 0.00024 for biexponential fits of β1a; χ2 = 0.028 for monoexponential and χ2 = 0.0006 for biexponential fits of β2a. C) Voltage dependence of the single activation time constant obtained from the monoexponential fit of Ca2+ currents. Unpaired t-tests revealed no significant differences in a comparison of β1a (empty symbols) versus β2a (filled symbols) at any voltage. D) Voltage dependence of the activation time constants obtained from the biexponential fit of the same data. Unpaired t-test revealed significance differences (p < 0.05) for τ slow at −5, 0, +5, +10, and +15 mV, and τ fast at +15, +20, +25, and +30 mV.

FIGURE 5.

Kinetics of activation of Ca2+ currents expressed by β2a in the absence and presence of RyR1. A) Normalized Ca2+ currents (gray) are shown in response to a 500-ms depolarization to +30 mV from a holding potential of −40 mV. Scale bar is 100 ms. The first 10 ms after the onset of the pulse was omitted, and the remainder of the pulse current was fit as a biexponential in all cases (black line). The top row shows the fit of the pulse current in normal (WT), RyR1 KO, and RyR1-expressing RyR1 KO myotubes. The bottom row shows the fit in β2a-expressing β1/RyR1 KO, RyR1 KO, and β1 KO myotubes. τ fast and τ slow are 8.6, 74.5; 4.3, 34.3; 6.1, 70.2; 16.3, 112.9; 16.3, 110.3; 16.9, 119.2 ms, respectively, from left to right with top row first. Relative contributions of fast and slow components are 0.24, 0.76; 0.26, 0.74; 0.28, 0.72; 0.16, 0.84; 0.20, 0.80; 0.15, 0.85, respectively, in the same order. B) The mean (+1 SE) τ fast and τ slow at +30 mV is shown for the genotypes analyzed above. The last three entries correspond to myotubes expressing β2a. The number of fitted Ca2+ currents, each from a separate myotube, included in the averages was 7 (WT), 10 (RyR1 KO), 10 (RyR1 KO + RyR1), 5 (β1/RyR1 KO + β2a), 10 (RyR1 KO + β2a), and 8 (β1 KO + β2a). One-way ANOVA showed no significant difference for τ fast (p = 0.75) or τ slow (p = 0.27) of β2a-expressing myotubes. All other entries were significantly different from β2a-expressing myotubes (p < 0.001). C) The mean (+1 SE) contribution of the fast and slow components of the biexponential fit is shown for all genotypes analyzed. One-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences between fast and slow components analyzed separately.

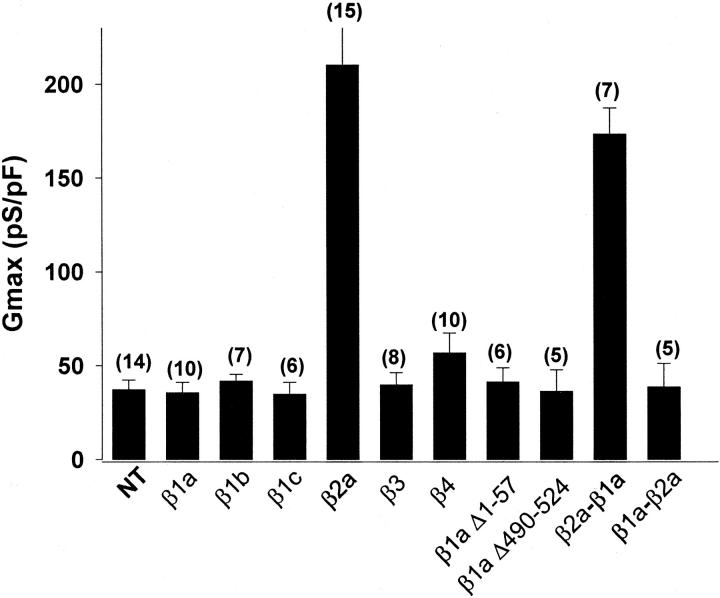

The molecular determinants of the β2a subunit responsible for Ca2+ current expression in the absence of RyR1 were pursued by screening variants of the four β-genes in RyR1 KO myotubes. Fig. 6 shows the maximal Ca2+ conductance of RyR1 KO myotubes overexpressing the indicated β-isoforms, all of which were subcloned in the mammalian expression vector pSG5. The β1b and β4 variants, which have abundant expression in the brain (Powers et al., 1992; Burgess et al., 1999), failed to recruit Ca2+ current above the endogenous level observed in nontransfected cells. Likewise, the β3 variant, which has a broader pattern of tissue expression (Castellano et al., 1993a), was also unable to recruit Ca2+ current. Thus, β2a was unique in its ability to stimulate Ca2+ current expression, and, as shown in Fig. 6, it stimulated Gmax ∼5-fold. Such stimulatory effect required the N-terminus half of β2a, as demonstrated by the large Gmax generated by the β2a-β1a chimera consisting of β2a domains D1, D2, and D3 and β1a domains D4 and D5. However, the reversed β1a-β2a chimera, consisting of β1a domains D1, D2, and D3 and β2a domains D4 and D5, failed to rescue Ca2+ current. We further asked whether a domain of the β1a subunit could be involved in inhibition of Ca2+ current expression in the RyR1 KO myotube. Elimination of this sequence might result in Ca2+ current reexpression when RyR1 was not present. To address this possibility, we investigated the involvement of the β1-specific D1, D3, and D5 domains. Neither deletion of domain D1 of β1a (β1aΔ1–57) nor domain D5 (β1aΔ490–524) had a positive effect on Ca2+ current expression. Furthermore, the splice variant β1c, which consists of β1a domains D1, D2, D4, and D5 and lacks D3 domain (Powers et al., 1992), also failed to express Ca2+ currents. We do not believe that these negative results arise from a lack of function because β1aΔ1–57, β1aΔ490–524, and β1c increased Ca2+ current expression in β1 KO myotubes (Beurg et al., 1999b). Furthermore, β1b increased Ca2+ current expression mediated by the neuronal α1A isoform in dysgenic myotubes (not shown), and β3 increased Ca2+ current expression mediated by the cardiac α1C isoform in double α1S/β1 KO myotubes (Ahern et al., 1999). In summary, structural determinants for Ca2+ current expression were mapped toward the N-terminus of β2a. Additionally, we did not find specific sequences associated with inhibition of Ca2+ current, which, in principle, could have been present in the skeletal β1a isoform and could account for the low Ca2+ conductance and comparatively large charge movements present in the RyR1 KO myotube.

FIGURE 6.

Ca2+ conductance recovered by DHPR β variants in RyR1 KO myotubes. The Ca2+ conductance of RyR1 KO myotubes transfected with the indicated β-construct was fit to Eq. 1 for the number of cells indicated in parenthesis. The β2a-β1a chimera was β2a 1–287/β1a 325–524. The β1a-β2a chimera was β1a 1–325/β2a 287–604. Gmax in pS/pF, V1/2 in mV, and k in mV were: 37.2 ± 5.2, 12.4 ± 2.4, 6.3 ± 0.3 for NT; 35.6 ± 5.6, 9.9 ± 3.7, 5.4 ± 0.3 for β1a; 41.7 ± 3.7, 18.1 ± 2.3, 6.8 ± 1.1 for β1b; 34.8 ± 6.4, 23 ± 2.4, 7.3 ± 1.7 for β1c; 195 ± 16, 10.8 ± 1.3, 4.9 ± 0.2 for β2a; 39.7 ± 6.5, 19.7 ± 2.8, 5.8 ± 0.5 for β3; 56.8 ± 10.6, 26.5 ± 2.6, 5.8 ± 0.5 for β4; 36.3 ± 11.5, 14.6 ± 2.0, 6.3 ± 0.6 for β1a Δ1–57; 41.3 ± 7.6, 17.9 ± 1.1, 6.3 ± 0.3 for β1a Δ490–524; 173 ± 14.0, 9.3 ± 2.4, 4.3 ± 0.6 for β2a-β1a; and 38.6 ± 8.2, 10.6 ± 3.4, 5.9 ± 2.2 for β1a-β2a. Unpaired t-test showed significant differences (p < 0.001) relative to nontransfected for the maximal Ca2+ conductance recovered by β2a and β2a-β1a.

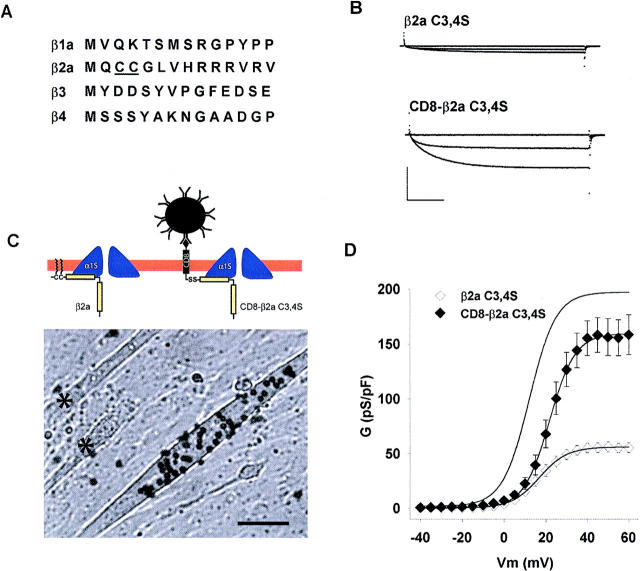

The rat β2a variant has vicinal cysteines at N-terminal positions three and four, which are not present in other splice variants from the same gene nor in variants from different β-genes (Fig. 7 A). The functional consequences of these two cysteines of β2a have been investigated in several expression systems and account for unique properties of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Chien et al., 1996; Qin et al., 1998; Restituto et al., 2000). Because the N-terminal half of β2a was required for Ca2+ current expression in the RyR1 KO myotube (Fig. 6), we investigated the participation of the double cysteine motif in this process. Following the approach of the three studies cited above, we mutated cysteines at positions three and four of β2a to serines and transfected the construct in RyR1 KO myotubes. Representative Ca2+ currents from a β2a C3,4S-transfected myotube are shown in Fig. 7 B, and the population average conductance versus voltage relationship is shown in Fig. 7 D. The Ca2+ current stimulated by β2a C3,4S was ∼threefold lower than that stimulated by wild type β2a, and was similar in density to that of nontransfected myotubes. The Gmax in β2a C3,4S-expressing and nontransfected RyR1 KO myotubes was 57 ± 3.9 pS/pF (n = 12 cells) and 37 ± 5 pS/pF (n = 14 cells), respectively, and the difference was mildly significant (t-test significance p = 0.011). As a positive control, β2a C3,4S was transfected in β1 KO myotubes, which express RyR1 but do not express Ca2+ current owing to the absence of the endogenous β-isoform (Gregg et al., 1996). Table 2 shows that the Ca2+ conductance of β2a C3,4S-expressing β1 KO myotubes was similar to that of wild-type β2a-expressing β1 KO myotubes. Thus, the inability of β2a C3,4S to recover Ca2+ current in RyR1 KO myotubes was due to the specific absence of the two cysteines and not due to a generalized inability of the construct to rescue Ca2+ channel function. Studies in nonmuscle expression systems have shown that the β2a variant becomes tethered to the plasma membrane by covalent palmitoylation of the double cysteine motif (see diagram in Fig. 7 C; Chien et al., 1996; Qin et al., 1998; Restituto et al., 2000). Furthermore, the unique properties of Ca2+ channels, conferred by β2a, require tethering of this subunit to the plasma membrane (Restituto et al., 2000). To demonstrate if a membrane tethering mechanism was responsible for the Ca2+ current stimulation caused by β2a in RyR1 KO myotubes, we expressed a fusion protein consisting of a β2a subunit lacking the double cysteine motif fused to the C-terminus of the transmembrane and extracellular domains of the lymphocyte glycoprotein CD8A. The CD8-β2a C3,4S fusion protein was previously shown to anchor β2a to the plasma membrane of HEK cells (Restituto et al., 2000). The N-terminus of the fusion protein carried an external epitope recognized by micron-size beads coated with an anti-CD8 antibody (see Materials and Methods). Thus, expression of the fusion protein on the surface of myotubes was recognized by incubation of transfected myotubes with anti-CD8 beads added to the external solution. Fig. 7 C shows a field of RyR1 KO myotubes transfected solely with the CD8-β2a C3,4S cDNA and incubated with anti-CD8 beads. Approximately 10% of transfected myotubes were found to bind CD8 beads, and the binding could not be removed by extensive washout of the external solution. The asterisks in Fig. 7 C mark myotubes lacking expression of the CD8 epitope. Bead-coated myotubes were found to express high-density Ca2+ currents in all cases (8 of 8 cells), whereas myotubes lacking expression of the CD8 epitope had Ca2+ current densities typical of nontransfected cells (4 of 4 cells). Ca2+ currents from a representative CD8-β2a C3,4S expressing RyR1 KO myotube are shown in Fig. 7 B, and the population average conductance versus voltage curve is shown in Fig. 7 D. For comparison, the line without data in Fig. 7 D shows the Boltzmann fit of the Ca2+ conductance of RyR1 KO myotubes expressing wild-type β2a obtained in Fig. 2. The Ca2+ conductance density expressed by CD8-β2a C3,4S was ∼threefold higher than that expressed by β2a C3,4S, and furthermore, a cell-by-cell analysis of the data (Table 1) indicated that the maximal Ca2+ conductance density (Gmax) expressed by CD8-β2a C3,4S was statistically indistinguishable from that expressed by wild-type β2a (Table 2). This result demonstrated that membrane anchoring of β2a via the CD8 transmembrane domain mimicked the Ca2+ current stimulation produced by the double cysteine motif present in wild-type β2a. Thus, it is likely that the double cysteine motif of β2a exerted its stimulatory effect on Ca2+ currents by a mechanism involving palmitoylation and anchoring of the β subunit to the myotube surface membrane.

FIGURE 7.

Participation of a double cysteine motif of β2a in Ca2+ current expression in RyR1 KO myotubes. A) Comparison of residues 1 through 14 of mouse β1a, rat β2a, rat β3b, and rat β4. Nonconserved cysteines at positions three and four of β2a are underlined. B) Ca2+ current expression by a β2a variant lacking cysteines at positions three and four (β2a C3,4S) and by a membrane-anchored variant CD8-β2a C3,4S in RyR1 KO myotubes. Ca2+ currents were elicited by 500-ms depolarizations from a holding potential of −40 mV to −10, +10, and +30 mV. Scale bars are 2 nA and 100 ms. C) Wide-field view of RyR1 KO myotubes expressing CD8-β2a C3,4S. Surface expression of the construct is revealed by anti-CD8 beads added to the external solution. Myotubes were transfected with the CD8-β2a C3,4S cDNA exclusively. Asterisk marks nontransfected myotubes in the same field. Bar is 50 microns and bead diameter is 4.5 microns. Diagrams depict membrane-anchoring of wild-type β2a and CD8-β2a C3,4S according to previous studies (Chien et al., 1996; Qin et al., 1998; Restituto et al., 2000). D) Voltage dependence of the Ca2+ conductance in RyR1 KO myotubes. The line without data corresponds to the voltage dependence of the Ca2+ conductance of β2a-expressing RyR1 KO myotubes from Fig. 2. Symbols show the mean conductance (± SE) for the number of cells indicated in Table 2. The lines are a fit of the mean conductance according to Eq. 1. Parameters of the fit with Gmax in pS/pF, V1/2 in mV, and k in mV are 56, 16.8, and 6.6 for β2a C3,4S (open diamonds); and 160, 21.7, and 6.8 for CD8-β2a C3,4S (filled diamonds).

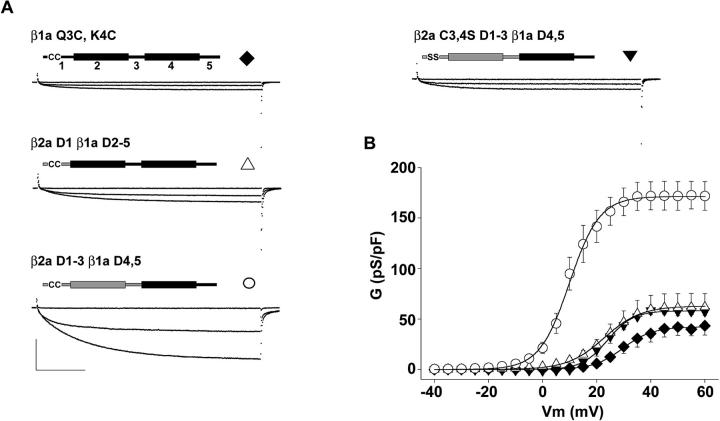

The exeriments in Fig. 7 demonstrated that the double cysteine motif of β2a was essential for the Ca2+ current stimulation observed in the absence of RyR1. However, this motif alone might not be sufficient. To determine whether the double cysteine motif acted alone or in combination with other domains of β2a, we transferred the N-terminal sequence of β2a to β1a and measured the Ca2+ conductance expressed by these chimeras in RyR1 KO myotubes. We first inserted cysteines at an equivalent position in β1a. Fig. 8 A shows that β1a Q3C, K4C was unable to stimulate Ca2+ current expression in RyR1 KO myotubes beyond the density present in nontransfected cells. We next replaced the entire D1 domain of β1a by the 16-residue β2a D1 domain. This chimera, namely β2aD1β1aD2–5, was also unable to significantly stimulate the expression of Ca2+ current in RyR1 KO myotubes. Finally, we replaced domains D1, D2, and D3 of β1a by equivalent domains of β2. This chimera, namely β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 expressed high-density Ca2+ currents, and the Gmax expressed in RyR1 KO myotubes was statistically indistinguishable from that of wild-type β2a (Table 2). Because D2 domains of β1a and β2a have a 78% similarity (see Materials and Methods), the positive results obtained with the last chimera suggest that domains D1 and D3 of β2a are essential for Ca2+ current expression in the absence of RyR1, whereas β1a D2 and β2a D2 may possibly be interchangeable. To determine if domains D1, D2, or D3 of β2a could stimulate Ca2+ currents in the absence of the double cysteine motif, the two vicinal cysteines in the high Ca2+ current-expressing β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 chimera were mutated to serines. Fig. 8 A shows that the Ca2+ conductance expressed by the β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5 chimera was drastically reduced. Elimination of the two cysteines reverted the Gmax expressed by the latter chimera back to that seen with β2a C3,4C (Table 2). In summary, the results with β2a-β1a chimeras reaffirmed the critical role of C3 and C4 in Ca2+ current stimulation. Additionally, domains D1–D3 of β2a were required for Ca2+ current stimulation. However, β2a D1–3 did not have an independent signaling function in the absence of C3 and C4. It is entirely possible that critical residues in β2a D1–3 provide a structural context essential for anchoring the subunit to the plasma membrane or for palmitoylation of C3 and/or C4 in the skeletal myotube. It is important to emphasize that all chimeras recovered a similarly large Gmax in the β1 KO myotube, regardless of their conductance behavior in the RyR1 KO myotube (Table 2). Therefore, the inability to stimulate Ca2+ current in the RyR1 KO myotube did not imply an inability of the construct to become integrated into a functional DHPR. The positive result in the β1 KO myotube indicated that molecular determinants must be present in the DHPR, perhaps in subunits other than β1a, for stimulation of Ca2+ current expression by RyR1.

FIGURE 8.

Participation of domains D1–D3 of β2a in Ca2+ current expression in RyR1 KO myotubes. A) Ca2+ currents are shown in RyR1 KO myotubes expressing the indicated construct. The diagrams depict domains D1–D5 with β1a sequence in black and β2a sequence in gray. β1a Q3C, K4C corresponds to wild-type β1a with glutamine and lysine at positions three and four replaced by cysteines. β2aD1β1aD2–5 corresponds to the chimera β2a 1–16/β1a 58–524. β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 corresponds to the chimera β2a 1–287/β1a 325–524. β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5 corresponds to the chimera β2a C3,4S 1–287/β1a 325–524. Ca2+ currents were elicited by 500-ms depolarizations from a holding potential of −40 mV to −10, +40, and an intermediate voltage which was +25 mV for β1a Q3C, K4C, +20 mV for β2aD1β1aD2–5, +10 mV for β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 and 25 mV for β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5. The intermediate voltage was close to the half-activation potential for each construct. Scale bars are 1 nA and 100 ms for all cells. B) Voltage dependence of the Ca2+ conductance in RyR1 KO myotubes. Symbols show the mean conductance (± SE) for the number of cells indicated in Table 2. The lines are a fit of the mean conductance according to Eq. 1. The parameters of the fit with Gmax in pS/pF, V1/2 in mV, and k in mV are 42.1, 29.7, and 5.4 for β1a Q3C, K4C (filled diamonds); 58.1, 23.9, and 4.7 for β2aD1β1aD2–5 (empty triangles); 171.4, 9.9, and 5.6 for β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 (empty circles); and 62.8, 22.7, and 6.8 for β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5 (filled inverted triangles).

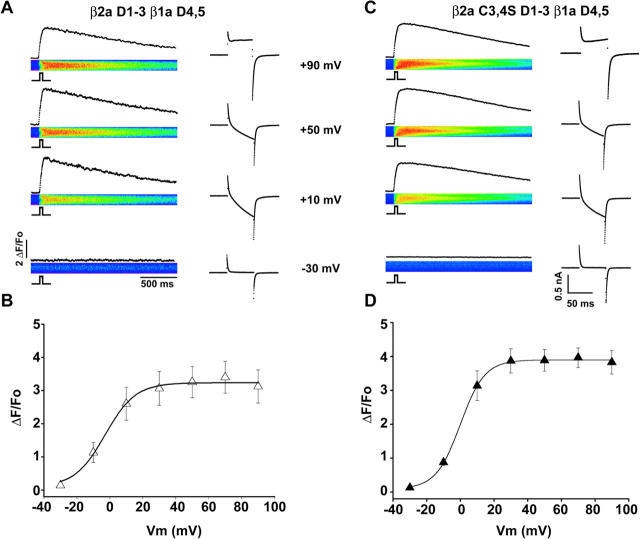

EC coupling takes place in peripheral couplings established between the surface membrane and the SR of cultured myotubes (Takekura et al., 1994). The structural evidence indicates that when RyR1 is not present, the native DHPR forms clusters that remain colocalized in the vicinity of peripheral couplings (Protasi et al., 1998). However, it is entirely possible that β-variants that have the membrane anchoring domain of β2a might divert the DHPR to other locations on the myotube surface. Consequently, the EC coupling characteristics of these myotubes might be perturbed because the rerouting of the DHPR away from peripheral couplings could actually reduce the DHPR density at functional EC coupling sites. To determine if the double cysteine motif modified the EC coupling characteristics, we investigated the recovery of Ca2+ transients produced by β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 and β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5 in β1 KO myotubes. Table 2 indicates that the former chimera was able to bypass the inhibitory signal from RyR1 and, therefore, express high-density Ca2+ currents in RyR1 KO myotubes. However, the latter chimera was not. Additionally, both chimeras had the C-terminal half of β1a, which is essential for fast skeletal-type EC coupling (Sheridan et al., 2002). Transfected cells were loaded with fluo-4 AM, and Ca2+ transients were elicited under voltage-clamp conditions. Ca2+-dependent fluorescence was measured in a confocal microscope in line-scan mode. We used voltage steps in the range of −30 mV to +90 mV from a holding potential of −40 mV to cover both the inward and outward phases of the Ca2+ current. To avoid cell fatigue and to allow for fluorescence recovery, we limited the number of depolarizations to seven, and each pulse was applied every 30 s. Fig. 9 A and C show the same stimulation protocols in β1 KO myotubes expressing β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 and β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5. The line scan images in pseudocolor correspond to one thousand (1000) 512-pixel lines stacked vertically from left to right with a total acquisition time (horizontal) of 2.05 s. The time course of the space-averaged fluorescence intensity is shown above each image, and the width of the square bar reflects the duration of the pulse. Ca2+ currents during the 50-ms depolarization are shown in expanded time scale next to each line-scan. In both cases, Ca2+ transient amplitudes increased with stimulus intensity and saturated at potentials more positive than +30 mV. The decay phase after the stimulation was also similar. Ca2+ currents underwent a reversal in polarity which is clearly seen by comparing depolarizations to +50 and +90 mV. However, this reduction in Ca2+ entry at positive potentials had no effect on the magnitude of the elicited Ca2+ transients. This result strongly suggested that skeletal-type EC coupling was recovered in both cases. To quantify the data, the maximal fluorescence during the stimulation in resting fluorescence units (ΔF/Fo) was plotted as a function of the depolarization potential and the mean fitted according to a Boltzmann distribution (Eq. 1). This is shown in Fig. 9 B and D for β1 KO myotubes expressing β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 and β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5, respectively. The fluorescence versus voltage relationship increased in a sigmoidal manner, and the parameters of the fit were similar (see legend of Fig. 9). A statistical analysis of the fluorescence versus voltage curve of each cell further corroborated that the maximal fluorescence reached at positive potentials was not significantly different (ΔF/Fo max = 3.1 ± 0.4 and 3.5 ± 0.2 ΔF/Fo for β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 and β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5, respectively, with t-test significance p = 0.34). These results clearly demonstrated that the double cysteine motif did not modify the EC characteristics of myotubes. Thus, at least in the β1 KO myotube, the two tested constructs were equally targeted to functional EC coupling sites.

FIGURE 9.

Absence of a contribution of the double cysteine motif to EC coupling recovery in β1 KO myotubes. A and C) Confocal Ca2+ transients at the indicated potentials are shown for β1 KO myotubes expressing either β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 (C = 164 pF), or β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5 (C = 182 pF). Myotubes were held at −40 mV and depolarized to the indicated potentials. The time course of the transient was obtained by integration of line scan images of fluo-4 fluorescence. The 50-ms depolarization used to stimulate the Ca2+ transient is indicated by the square pulse. The Ca2+ current during the depolarization is shown expanded next to each line scan at the same scale. For visual reference, pseudocolors, in ΔF/Fo units, are blue <0.2; yellow <2; and red <4. In the images, the total line scan duration (x axis) was 2.05 seconds and the cell dimension (y axis) was (in microns) 17.5 for β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 and 23.5 for β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5. B and D) Voltage dependence of the mean peak fluorescence (± SE) during the Ca2+ transient in ΔF/Fo units. The lines are a fit of the mean ΔF/Fo according to Eq. 1. The parameters of the fit with Fmax in ΔF/Fo, V1/2 in mV, and k in mV are 3.1, 0.6, and 8.5 for β2aD1–3β1aD4,5 (empty triangles, 8 cells); and 3.6, 1.2, and 7.1 for β2aC3,4SD1–3β1aD4,5 (filled triangles, 5 cells).

DISCUSSION

In the present work, we investigated the role of the β-subunit of the DHPR in Ca2+ current and charge movement expression in myotubes deficient in RyR1, which is a critical modulator of DHPR function (Nakai et al., 1996, 1998; Avila and Dirksen, 2000; Avila et al., 2001). The main features of this work are: 1) Myotubes expressing β1a accumulated a higher density of DHPR charge movements than those expressing β2a either in the absence or presence of RyR1. The data were especially compelling in β1/RyR1 KO myotubes where the low-background made it possible to demonstrate that the β1a-specific charge was approximately twice the β2a-specific charge. However, the comparatively larger charge movements recovered by β1a did not produce a proportional increase in Ca2+ current density. 2) The β2a-expressing myotube had a wild-type Ca2+ current density either in the presence or absence of RyR1. Thus, RyR1 is not indispensable for DHPR Ca2+ current expression in skeletal myotubes when the heterologous β2a subunit is present. The signal for RyR1-independent Ca2+ current expression was a double cysteine motif present at the N-terminus of β2a and could be transferred to β1a, provided that β2a domains D1, D2, and D3 were also transferred. Tethering β2a to the myotube surface in the absence of the two vicinal cysteines also increased Ca2+ current expression. 3) The EC coupling characteristics recovered in β1 KO myotubes by β variants, with and without the double cysteine motif, were the same. Observations 1), pertaining specifically to the behavior of β1a, carry significant implications for the cellular events controlling expression of Ca2+ current and EC coupling voltage sensors in the skeletal myotube. Observations 2) demonstrated that an ad hoc mechanism exists in β2a, an isoform not endogenously expressed in skeletal myotubes, for bypassing the inhibition of Ca2+ current expression imposed by the absence of RyR1. Finally, observations 3) show that the double cysteine motif does not impinge on the ability of the DHPR to be functionally coupled to RyR1.

Coexpression studies in amphibian oocytes previously showed that the α1E/β1a subunit pair expressed significantly more gating current and less Ca2+ current than the α1E/β2a pair (Noceti et al., 1996). In α1E/β1a channels, a significant fraction of the expressed intramembrane charges were determined to be peripheral to the gating process and were not coupled to the actual opening of the pore. Such “silent” or low-conducting channels contributed to the total cell charge but not to the Ca2+ current. Studies in β1 KO myotubes also indicated that the β1a and β2a variants produced a differential recovery of Ca2+ currents and charge movements (Beurg et al., 1999a). In this expression system, β1a and β2a restored the same Ca2+ current density, and the nonstationary variance properties of the Ca2+ currents were also similar. On the other hand, the density of DHPR charge movement restored by α1S/β2a complexes was significantly lower than that restored by α1S/β1a complexes, and this observation was confirmed in the present study. The previous study could not pinpoint the contribution of RyR1, because the latter is constitutively present in the β1 KO myotube (Gregg et al., 1996). We have now shown that, in the absence of RyR1, β1a promoted expression of DHPR charge movements; however, Ca2+ current expression was minimal. By contrast, β2a modulated DHPR function in the opposite direction, namely, toward more Ca2+ current and less charge movement expression. Hence, the inability of the native skeletal DHPR to express Ca2+ currents appears to be dictated by the properties of the β-subunit possibly in combination with molecular determinants elsewhere in the DHPR. In this respect, it is important to mention that the C-terminus of α1 subunits is known to play a role in Ca2+ channel regulation, serving as a binding site for β-subunits in some α1/β pairs (Walker et al., 1998; Tareilus et al., 1997), and promoting surface expression of α1C and α1S channels (Gao et al., 2000; Proenza et al., 2000).