Abstract

Experimentally, short peptides have been shown to form amyloids similar to those of their parent proteins. Consequently, they present useful systems for studies of amyloid conformation. Here we simulate extensively the NFGAIL peptide, derived from the human islet amyloid polypeptide (residues 22–27). We simulate different possible strand/sheet organizations, from dimers to nonamers. Our simulations indicate that the most stable conformation is an antiparallel strand orientation within the sheets and parallel between sheets. Consistent with the alanine mutagenesis, we find that the driving force is the hydrophobic effect. Whereas the NFGAIL forms stable oligomers, the NAGAIL oligomer is unstable, and disintegrates very quickly after the beginning of the simulation. The simulations further identify a minimal seed size. Combined with our previous simulations of the prion-derived AGAAAAGA peptide, AAAAAAAA, and the Alzheimer Aβ fragments 16–22, 24–36, 16–35, and 10–35, and the solid-state NMR data for Aβ fragments 16–22, 10–35, and 1–40, some insight into the length and the sequence matching effects may be obtained.

INTRODUCTION

Protein folding has been one of the most explored biological topics and it is still an unsolved question. Within this general problem, there are questions that are intrinsically related to the comprehension of the conformational behavior of proteins (Chiti et al., 2002). Among these, the deposition of normally soluble proteins as fibrillar structures is particularly challenging. This process is a common feature of different and apparently unrelated diseases, such as Alzheimer's and prion protein-related encephalopathies (Kisilevsky, 2000). The proteins involved are unrelated in sequence and in native conformations. Nevertheless, all share aggregate fibers with common structural and histological features, frequently leading to cellular death. Furthermore, recently it has been shown that nondisease-associated proteins can also form similar aggregates, and that the species they form early in the aggregation process can also be highly toxic (Bucciantini et al., 2002). This issue of the nature of the toxic species is hotly debated. Current data suggest that intermediate soluble oligomers are the origin of cytotoxicity, although there are experimental data in favor of fiber toxicity (see Hardy and Selkoe, 2002, for an up-to-date review).

Fibrillar deposits are organized in cross-β-sheet structures in which the β-strands are arranged perpendicular to the fiber axis. This particular organization gives a characteristic green birefringence upon binding the dye Congo red (Sunde and Blake, 1998). In all cases, it appears that the process of structure formation follows similar kinetic patterns. Fibrillogenesis is characterized by a lag phase during which no fibers are detected. This phase is followed by fiber formation on a timescale that could be shorter than the lag phase. The lag phase can be bypassed by nucleating the reaction with preformed fibers (seeding, Rochet and Lansbury, 2000).

More than 90% of type II diabetic patients have amyloid depositions surrounding the islet cell of the pancreas. These deposits form predominantly by fibers composed of a 37-residue peptide, the islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP). The IAPP is cosecreted with insulin by the β-cells. Its function is still unknown, but was proposed to have an important role in insulin response. The observed insulin resistance in diabetes II patients supports this hypothesis (Gebre-Medhin et al., 2000).

Recently, this polypeptide has been increasingly studied as a simple model for factors governing amyloid fibril formation. There are several reasons for this choice. First, only a small number of animal species is known to show amyloidogenesis. These include human and nonhuman primates, cats, and raccoons (Westermark et al., 1990). Interestingly, there is a correlation between the sequence patterns and the occurrence of protein deposits in different species. More over, the majority of the sequence differences cluster in a very short segment, between residues 22 and 29 (Table 1). This segment has been a target of intensive research, because in vitro it forms fibrils similar to those of the whole polypeptide in vivo.

TABLE 1.

Amino acid sequences of the IAPP segment (20–29) of humans, cats, and rats

| Species | 20–29 |

|---|---|

| Human | SNNFGAILSS |

| Cat | SNNFGAILSP |

| Rat | SNNLGPVLPP |

Residues different from the human sequence are highlighted in bold and italic.

Although it appears that this segment is important for amyloid formation, it is still unclear just how important it is. Several groups have proposed that this short segment only affects the polymerization kinetics but does not play a significant role in the thermodynamics of amyloidogesis. Nilson and Raleigh (1999) have demonstrated that an additional IAPP segment consisting of residues 30–37 is able to form amyloids after a relatively long seeding time. They have further shown that the amyloidogenicity of certain segments was sensitive to ionic strength. Based on secondary structure prediction, Jaikaran et al. (2001) have identified the IAPP segments capable of forming amyloid aggregates under similar conditions as hIAPP, those of 20–29, 8–20, and 30–39. Consequently, they proposed a compact structural motif for the entire peptide in which the β-sheet structure of the superhelix is a sheet with three strands connected by two turns (Jaikaran and Clark, 2001). Based on their spectroscopic studies of the IAPP, Padrick and Miranker (2001) have proposed that the quenching behavior they observed in their amyloid aggregates is the outcome of the 30–37 segment organization.

Investigations of the 20–29 segment have identified the shortest hIAPP fragment capable of forming fibrillar depositions. Residues 22–27, NFGAIL, form aggregates similar to those of the entire hIAPP (Tenidis et al., 1999). These fibers are similarly cytotoxic to pancreatic β-cells. Furthermore, the same segment from rat is unable to develop fibrillar structures. Therefore, not only the information included in the human peptide but also the one from the rat sequence presents a good model to investigate toxic deposits.

Recently, the role of every amino acid in the NFGAIL sequence has been investigated (Azriel and Gazit, 2001) via systematic alanine scanning mutagenesis. Azriel and Gazit have identified which of those six amino acids are critical for fibril formation. They have further analyzed the effect of Ala substitutions on the kinetics of aggregation (Table 2). They concluded that Phe appears extremely important to aggregate stability, whereas the polar residue Asn appears to play a clear role in the polymerization kinetics. This residue drives the system to a collapsed structure by increasing the rate of aggregation and inducing formation of shorter fibers. Finally, the effect of the apolar residues only concerns the kinetics of the polymerization, without affecting the final fibrillar organization.

TABLE 2.

Summary of the results obtained by Ala scan on the octapeptide NFGAILSS

| Aggregated structures | Polymerization kinetics | |

|---|---|---|

| AFGAILSS | Short and branched fibers | Faster aggregation |

| NAGAILSS | Nonfibril organization | |

| NFAAILSS | Long fibers | Similar velocity |

| NFGAALSS | Long fibers | Slower kinetics |

| NFGAIASS | Long fibers | Slower kinetics |

The results are compared with the wild-type derivative. The Ala substitution is shown in bold.

Here we focus on molecular events in amyloid formation. We model a basic fibrillar motif following our previously established protocol (Ma and Nussinov, 2002a). For this purpose, hIAPP is particularly useful because it is the shortest detected amyloidogenic sequence with only six amino acids. This suggests that we can extensively simulate large systems, examining different possible molecular arrangements of the NFGAIL sequence in reasonable computational time. Our simulations probing the stability of the peptide-sheet complexes are a simplification of amyloid formation. Nevertheless, they enable us to address several key questions: How is the initial seed stabilized? What is the role of hydrogen bonds versus hydrophobicity? What is the smallest size that a seed can be? Through the simulations, we have established that an oligomer of 6–9 peptides is stable enough to be a seed and that the driving force for stabilization is the hydrophobic effect. The observation is that the β-sheet oligomer is stable only when it reaches this size, and leads to its slow formation and an inevitably long lag phase.

METHODS

Using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we followed the dynamic properties of our system, analyzing the different models. We considered the majority of possible arrangements of the NFGAIL peptide within a β-sheet supramolecular organization. We systematically explored different strand packing and orientations, starting from a dimer and growing the size of our assembled structure up to nine strands (nonamer).

Computational details

All calculations were performed using the CHARMM package (Brooks et al., 1983). All atoms of the system were considered explicitly and the potential energy of the system was computed using the CHARMM 22 force field (MacKerell et al., 1998). Inasmuch as there are still no detailed data on the hIAPP structure, we use explicit representation of the solvent molecules, using the TIP3 water model (Jorgensen et al., 1982), in an attempt to obtain similar fibrillogenic conditions. The combination of both force field and water model has already been shown to provide a good description of both the conformational properties and the free energy of formation in β-sheet rich systems (Bursulaya and Brooks, 1999).

All simulations were performed using the NVT ensemble in a cubic box, i.e., at constant volume, temperature, and mass. Periodic boundary conditions were applied using the nearest image convention. The box size was increased depending on the initial complex shape, to maintain infinite dilution conditions.

The initial β-sheets assemblies were constructed using a simple geometrical criterion. Hydrogen bonded chains were placed at 4.7 Å and the distance between the sheets was set to 10 Å, which corresponds to the average distance in a cross-β structure (Sunde and Blake, 1998). Every starting molecular structure was built using the INSIGHTII molecular package (MSI, Burlington, MA, 1997). All the initial amyloid models were solvated by water molecules taken from a Monte Carlo equilibrium simulation until an approximate total density of 1 g/cm3 was achieved. Before running each MD simulation, the potential energy of the system was minimized for a total of 500 minimization steps. We applied a combination of steepest-descent and the Newton-Raphson methods (200 and 300 steps, respectively).

All simulations were carried out at 350 K to enhance the stability differences between the built models by means of a stronger thermal stress. Residue-based cutoffs were applied at 10 Å, i.e., if two residues or a residue and a water molecule have any atoms within 10 Å, the interaction between the pair is evaluated. The SHAKE algorithm (Ryckaert et al., 1977) was applied to fix the bond lengths and a numerical integration time step of 2 fs was used for all the simulations. The nonbonded pair list was updated every 25 steps. The MD trajectories were saved every 500 steps (1-ps interval) for subsequent analysis.

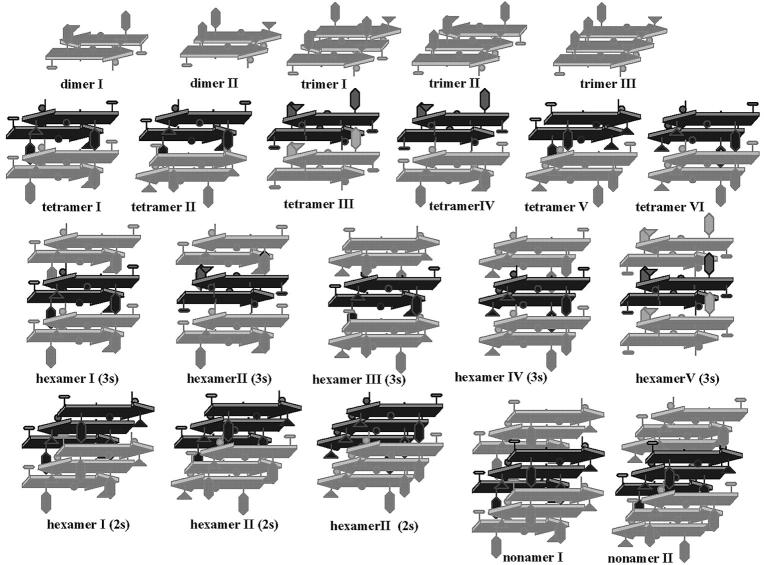

Twenty-two trajectories were run for a total of 31 ns. The trajectory of every model was followed for 1 ns, except for the nonamer models, which needed additional simulation time to establish their relative stabilities. In these latter cases, we ran 4 ns for each system. All our structural arrangements are depicted in Fig. 1, from a two-stranded sheet to a basic nonamer structural motif.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the structural models that were built to search for the preferred arrangement for the hIAPP (22–27) peptide. Up to tetramers, strands of the same sheet are drawn with the same color. Schematic side-chain representations have been added to clarify the different possible orientations between chains of different β-sheets.

Structural characterization

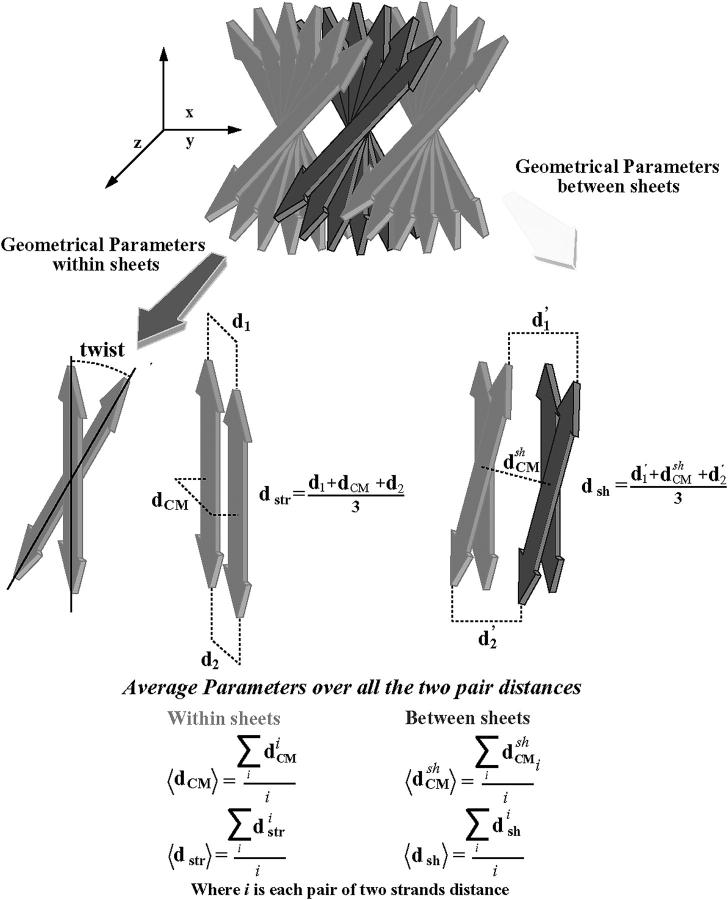

Because there were no structural data to compare with, we have developed analytical strategies to characterize our structural models. Parameters like the root mean-square distance, the native contacts, and the Ramachandran plot relate to some well-known structure. However, in our case, we did not have detailed information on our system. Further, large changes in the main-chain conformation do not necessarily imply a decrease of stability, inasmuch as the reference dihedral angles are unknown (Chakrabarti and Pal, 2001). Consequently, we implement geometrical parameters that can conceivably provide structural information in terms of global organization. We describe the cross-β structure using three main geometrical parameters (Fig. 2). The most intuitive one is the distance between strands within a sheet. This is indirectly achieved by the number of intrasheet hydrogen bonds remaining during each simulation. Related to that distance, there is the twist angle between strands of the same sheet. The twist reflects steric effects between associated strands. Although this parameter may not account for the relative stabilities between models, it determines the periodicity of the amyloid β-superhelix. The third parameter is the distance between sheets. We seek a structural model capable of maintaining a cross-β structure, which means it has to retain a superhelical organization within and beyond the sheets. We initially calculate the average distances between the mass centers of the strands, within and between sheets (called 〈dCM〉 and  respectively, in Fig. 2). However, using only the mass center distance, there could be some geometrical distributions of the strands that could give us an apparent erroneous stability, inasmuch as our system needs to maintain ordered strands. This appears especially relevant for sheet association. Independent of fiber width, a cross-β structure must maintain a minimal regularity along the associating sheet axis (see Fig. 2) for subsequent growth along this axis. A presumed twist between sheets cannot be observed when measuring only mass center distances. Thus, we define additional distance parameters by averaging three main distances between two strands, two distances between the ends, and the mass center distances. These additional distance parameters should show the degree of the loss of cohesion in each model along the simulation time (in Fig. 2 called 〈dstr〉 and 〈dsh〉, respectively).

respectively, in Fig. 2). However, using only the mass center distance, there could be some geometrical distributions of the strands that could give us an apparent erroneous stability, inasmuch as our system needs to maintain ordered strands. This appears especially relevant for sheet association. Independent of fiber width, a cross-β structure must maintain a minimal regularity along the associating sheet axis (see Fig. 2) for subsequent growth along this axis. A presumed twist between sheets cannot be observed when measuring only mass center distances. Thus, we define additional distance parameters by averaging three main distances between two strands, two distances between the ends, and the mass center distances. These additional distance parameters should show the degree of the loss of cohesion in each model along the simulation time (in Fig. 2 called 〈dstr〉 and 〈dsh〉, respectively).

FIGURE 2.

The main geometrical parameters used to describe the simulated molecular arrangements.

RESULTS

Stability within a sheet

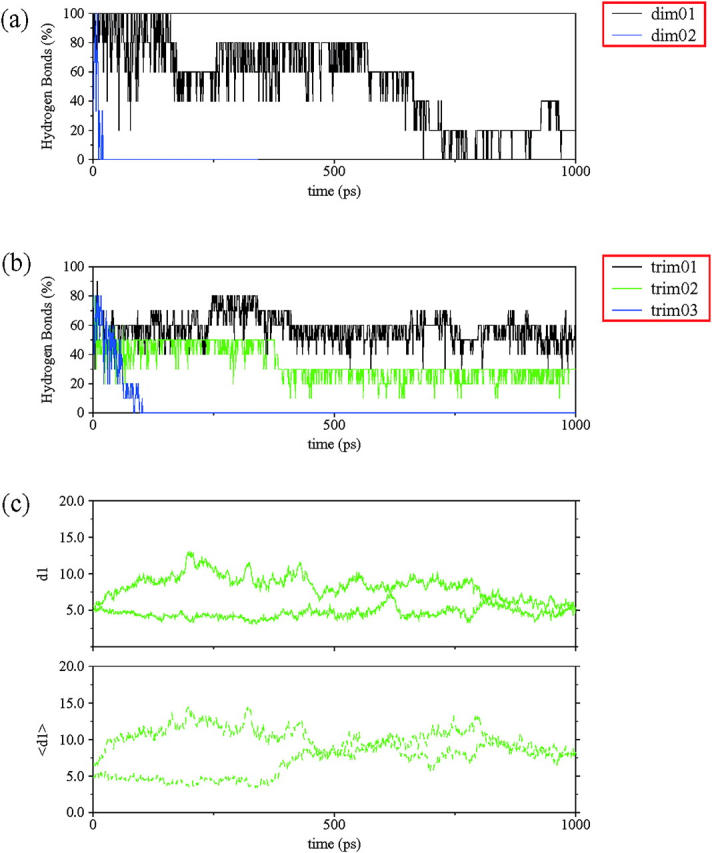

To detect the preferred orientation of the strands within a sheet, we built seven different models with two and with three strands (dimers and trimers). When there are only two interacting strands, the antiparallel orientation between strands is the most stable (dimer I in Fig. 3 a). This arrangement was able to retain more than 60% of the original hydrogen bonds for ∼600 ps. All other models lost their structural integrity very quickly. The parallel arrangement (dimer II) retained more than 50% of the original interactions for less than 50 ps. Furthermore, models with some shifts between strands in a direction perpendicular to the hydrogen bonding axis (not shown) unfolded even before the end of the equilibration period, due to the short peptide length.

FIGURE 3.

Some structural parameters used to characterize the organization of the NFGAIL segment within a sheet. The fraction of the initial hydrogen bonds for each model preserved along the simulation is presented for (a) dimers and (b) trimers. A hydrogen bond is considered when the O…H distance is less than 2.5 Å and the NH-O angle is larger than 130°. (c) The two mass center distances (d1) and ddtr (〈d1〉) of trimer II. See Fig. 2 for definitions.

The simulations with single, three-stranded sheets showed very similar tendencies. The full antiparallel arrangement (trimer I) was able to maintain more than 50% of the original hydrogen bonds for 1 ns (Fig. 3 b). At the same time, a trimer with a combination of parallel and antiparallel orientations (trimer II) quickly lost the interactions between the parallel strands, with only the interactions formed by antiparallel strands holding up. The behavior of the antiparallel interacting strands is identical to that of dimer I (Fig. 3 c). Finally, the full parallel trimer (trimer III) separated very quickly, following the same pattern described for its corresponding dimer.

Supramolecular organization

Several factors may determine the structural cohesion of the NFGAIL fibers. Initially we focus our attention on two aspects: side-chain interactions and the hydrophobic effect. The latter was implicitly achieved using explicit solvent representation, whereas the former leads us to construct different possible strand orientations to explore all possible side-chain packing. We compute the initial sheet interactions using tetramers (two two-stranded sheets) with different relative orientations of the strands within and between the sheets.

Our two-sheet structural models follow similar behavior as the one-sheet systems. A preliminary stability comparison, in terms of remaining hydrogen bonds, shows that all antiparallel arrangements of chains within a sheet maintained the original hydrogen bonding scheme better than the parallel orientation (Fig. 4 a). Both parallel arrangements quickly lost all hydrogen bonds. Detailed chain pair-distances within and between sheets confirmed that the system is unstructured.

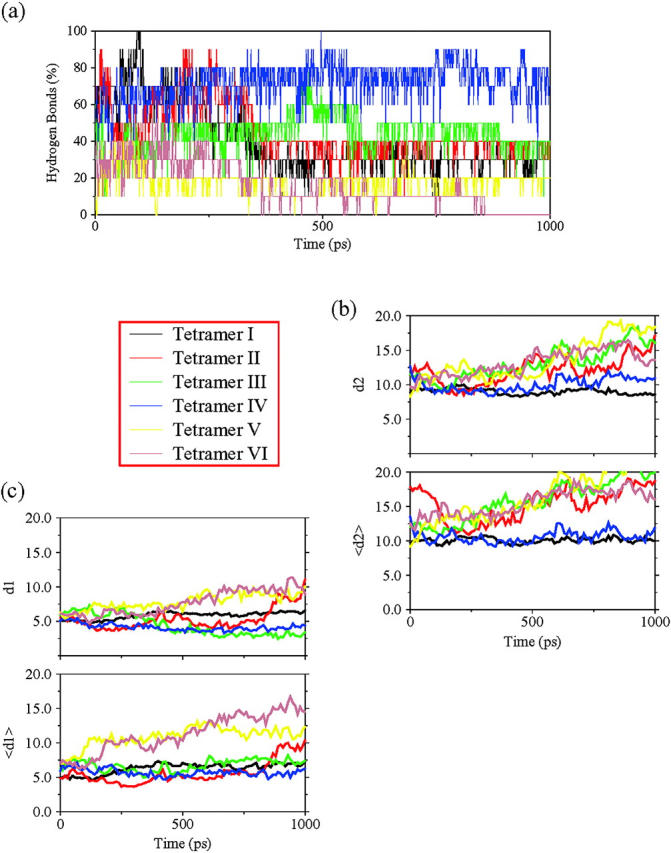

FIGURE 4.

(a) The fraction of hydrogen bonds for each tetrameric model along the simulated time. (b) The average mass center distances (d2) and the main strand distances 〈dsh〉 (〈d2〉) between sheets, for all tetramers investigated. (c) The average mass center distance (d1) and the main strand distance 〈dstr〉 (〈d1〉) within sheets, for all investigated tetramers. See Fig. 2 for definitions.

Following the hydrogen bonds with simulation time, the results obtained with the different antiparallel models appear to indicate that models with minimal steric hindrance are favored. Tetramer IV, which is able to retain more than 60% of the original hydrogen bonds, is the most stable, although it has large hydrophobic side chains (Phe, Ile, Leu) facing the solvent. Tetramers I, II, and III retain an acceptable percentage of the hydrogen bonds in the 1-ns simulation (between 40 and 50%). These models have only one-half of their aromatic side chains inside the hydrophobic pocket.

With regard to sheet packing, both models I and IV are clearly able to maintain an organized structure, not only in terms of mass center distance  but also in the values of 〈dsh〉 (Fig. 4 b). However, the remaining structural arrangements are characterized by a quick loss of the bulk organization. This is especially clear in both models with parallel stranded sheets (tetramers V and VI).

but also in the values of 〈dsh〉 (Fig. 4 b). However, the remaining structural arrangements are characterized by a quick loss of the bulk organization. This is especially clear in both models with parallel stranded sheets (tetramers V and VI).

Detailed examination of the chain pair-distances yields a clearer view of the molecular details that drive the organization of each model. Tetramers I and IV preserve both inter- and intrasheet distances as seen by the small differences between all initial and final distances. In the case of tetramer I, the slight increase in the interstrand distance in one sheet results from partial disruption of the hydrogen bonds scheme at the edges of the sheet (Fig. 5). The mass center distances show that the hydrogen bonds in the central segment of the sheet are still retained. At the same time, the structural disruption observed in both tetramers II and III can be explained by breaking a sheet. In both cases, the increase of the interchain distances clearly points that packing is able to retain only half of the oligomer, leading at the end of the simulation to a dimeric system (Fig. 5).

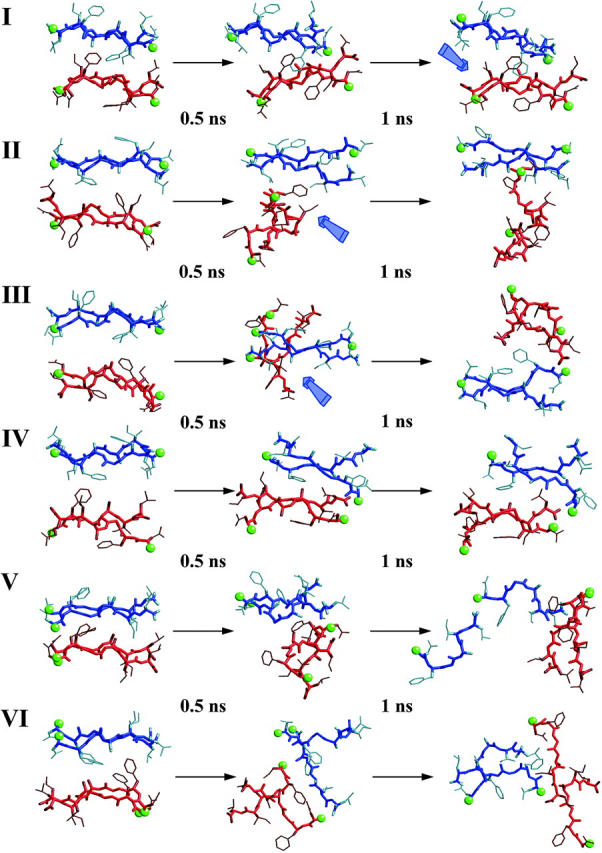

FIGURE 5.

Detailed structural snapshots of all simulated tetramers, with equally spaced intervals over the 1 ns of the MD simulation. Strands that belong to the same sheet are drawn with the same color (either blue or red). Green balls show the N-terminus of each strand. Blue arrows point to positions of structural interest (see text).

Consequently, only two molecular arrangements satisfy the selected structural criteria. In addition, tetramers II and III, even though they lost their regular structural organization after 1 ns, their intersheet distances show that these two arrangements are able to maintain a reasonable structural integrity for 500 ps (Fig. 5). In both cases the sheets themselves are stable enough to keep their strands intact; however, steric interactions do not favor the intersheet organization. These effects finally lead to intrasheet dissociation.

To get an insight into the system, we build hexameric systems of three sheets with two strands in each to examine the effect of the stabilization induced by sheet association. We further explore if there is a case in which the tendencies observed with the tetrameric models are altered by nonadditive effects. With these models, we are able to bury the side chains of an entire sheet and study steric hindrance in the packing of three β-sheets.

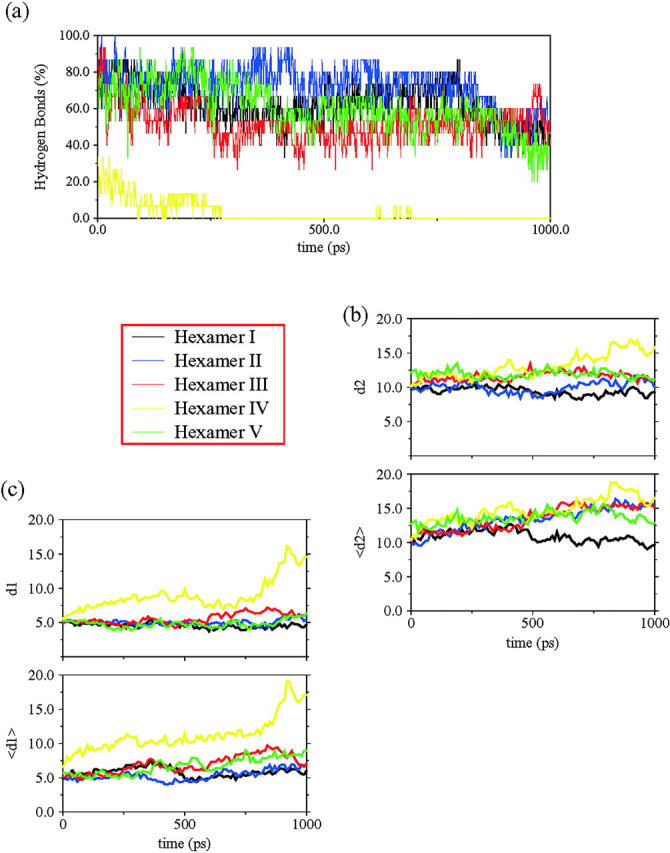

Regarding the number of original hydrogen bonds (Fig. 6 a), only hexamer V has a meaningful decrease. The other four models are able to maintain up to 45% of their original interactions. It is noteworthy that only this model has parallel arrangement of strands within the sheets.

FIGURE 6.

(a) The fraction of hydrogen bonds for each hexamer for the three sheets along the simulation time. (b) The average mass center distances (d2) and the main strand distances 〈dsh〉 (〈d2〉) between sheets, for all the models investigated. (c) The average mass center distance (d1) and the main strand distance 〈dstr〉 (〈d2〉) within sheets, for all models investigated. See Fig. 2 for definitions.

Examining the geometrical parameters related to sheet organization, we find that the model derivative of tetramer IV (hexamer II (3s); see Fig. 1) presents an unexpected structural disruption in the packing pattern. Tetramer IV is the most stable model until this point, but the asymmetric contacts induced by fitting a third sheet seem to play a key role in the overall stabilization. The average intersheet distance remains stable, whereas the 〈dsh〉 rises suddenly after 200 ps of simulation (Fig. 6 b). This nonconcerted behavior of both parameters can only be explained by the appearance of a marked twist between the associating sheets, i.e., perpendicular to the superhelical direction. Detailed inspection shows that this model lost its integrity at the location where an extra sheet was added (Fig. 7). As can be expected, steric hindrance introduced by the side chains of the new sheet disrupts the fiber growth direction. On the other hand, the effect of adding a new sheet in hemaxer I (3s) (see Fig. 1), which is a derivative of tetramer I, makes this model the most stable. In this structural arrangement, the combination of the hydrophobic effect (burying two-thirds of the hydrophobic residues) and the good geometrical matching in terms of the van der Waals distances enhances dramatically the stability of the structure. The other two packing models with antiparallel strands in their sheets illustrate very similar features to their parent tetramers. Both illustrate a marked drift in the intersheet organization, followed by complete disruption of one of their sheets (hexamers III and V, Figs. 6 and 7).

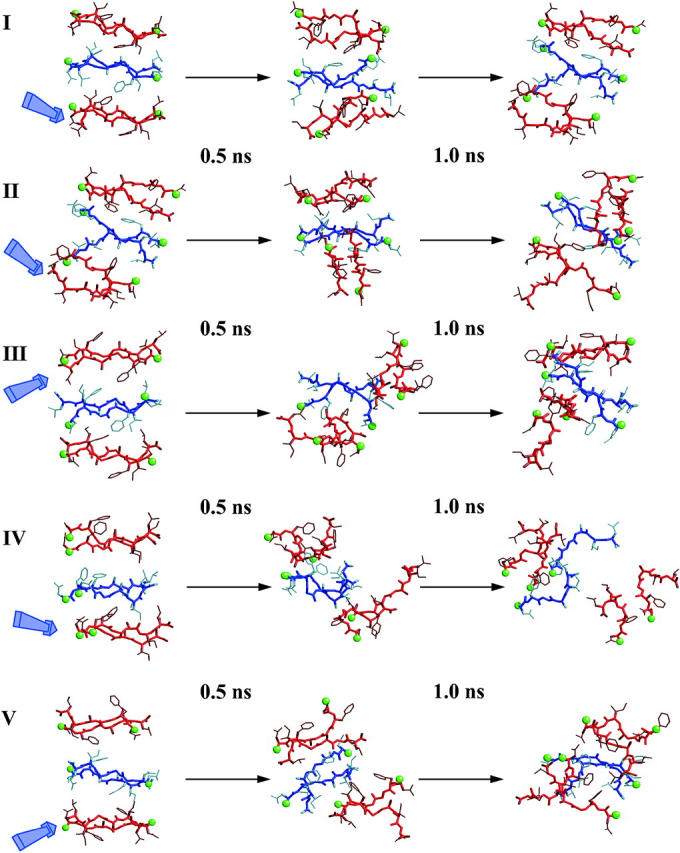

FIGURE 7.

Detailed structural snapshots of the simulated hexamers with three sheets, with equally spaced intervals over the 1 ns of the MD simulation. Strands that belong to the same sheet are drawn with the same color (either blue or red). Green balls show the N-terminus of each strand. The blue arrow points to the position where the new sheet was added to the former tetramers.

Before establishing a final model, we ensure that hydrogen bonds are not the key to the self-assembly process. We build three new hexamers with two three-stranded sheets. We choose three different arrangements that can represent all packing patterns: the equivalent packing of tetramer I as the most favored one, the packing obtained with tetramer II as an all-antiparallel arrangement, and finally an all-parallel arrangement to have an unstable packing reference (hexamers I, II, and III (2s), respectively). The behavior achieved by these systems is analogous to that observed from their former models (tetramers and hexamers (3s)). The increase in hydrogen bonds stabilized each sheet, but not the bulk organization (data not shown).

Within the NFGAIL structure

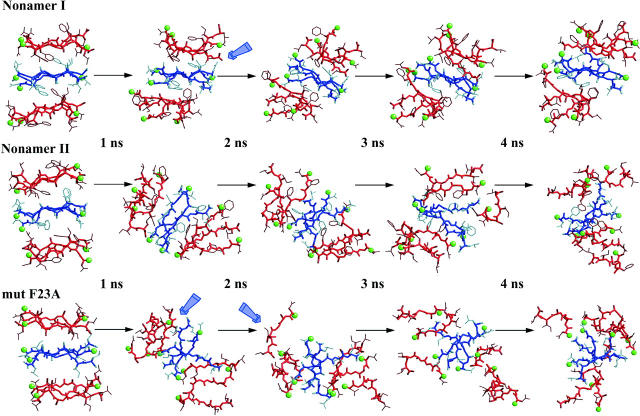

To check the reliability of our structural model, we carried out three additional simulations. We built two nonamers consisting of three sheets, with three strands in each sheet. We expanded two models from our previous simulations, both with possible antiparallel arrangements (the corresponding nonamers from hexamers I and II (2s)). At this point we left out all parallel organizations.

The new simulations required more than 1 ns to reach a meaningful conclusion. Adding a whole new set of strands implied new sets of hydrogen bonds and burial of the hydrophobic residues on the central sheet. Nevertheless, the behavior observed was similar to that of the equivalent former hexamers (2s) (Fig. 8). After 1.5 ns of simulation, nonamer II starts losing its structural tightness at the same site where the former hexamer did (II (2s)). This suggests again that the association between sheets is a key factor that governs the self-assembly process, i.e., correct side-chain fitting that allows chemical groups to properly interact (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Detailed structural snapshots of nonamers I and II, and the nonamer of the sequence NAGAIL, with equally spaced intervals over the 1 ns of the MD simulation. Strands that belong to the same sheet are drawn with the same color (either blue or red). Green balls show the N-terminus of each strand. Blue arrows point to the position of some structural rearrangements (see text).

At this point we have obtained an arrangement that could work as the basic structural motif of the NFGAIL segment. Still, we constructed a third structure to test its capability to reproduce the reported experimental data. Azriel and Gazit (2001) reported that the mutation F23A was critical for the amyloid organization of this particular peptide segment. Thus, we proceeded to test the reliability of our conformational model by repeating the same calculation we performed with nonamer I but building our amyloid system with NAGAIL segments. If our model is a valid description of the cross-β-sheet structure adopted by the NFGAIL segment, the F23A mutant peptide should quickly lose its bulk organization. This was the result we have obtained. Exchanging an aromatic by a small hydrophobic residue drove the oligomer to quickly lose its organization. It is interesting to note how the entire sheet is disrupted. The sheet starts breaking at the most stable side of the wild-type sequence (Fig. 8). Thus, the effect of the aromatic ring in this specific segment correlates with the major stabilizing force of the fiber organization.

DISCUSSION

Currently we have structural information for a number of peptide-derived amyloids (Lynn and Meredith, 2000). For the Alzheimer β-protein (Aβ) residues 16–22 and 34–42, solid-state NMR has established an antiparallel conformation (Balbach et al., 2000). For the Aβ10–35 and Aβ1–40, solid-state NMR has established a parallel-stranded structural interaction (Benzinger et al., 1998; Antzukutkin et al., 2000). For Aβ25–35, whereas the infrared spectra of the amyloid indicates the existence of β-sheet organization, x-ray failed to detect an ordered crystalline (Mason et al., 1996; Kohno et al., 1996). Following analogous simulation protocols to those used here, we have obtained parallel models for Aβ16–35 and Aβ10–35, and antiparallel orientation for Aβ19–22 (Ma and Nussinov, 2002b). Further, simulations have also indicated that the prion-derived AGAAAAGA has an antiparallel-stranded conformation, and so does AAAAAAAA (Ma and Nussinov, 2002a). Here we show that a short six-residue peptide, NFGAIL, derived from the islet amyloid polypeptide, similarly prefers an antiparallel organization. Further, for this peptide, as for the A8, extensive simulations have been carried out to explore possible organizations. For the polyalanine, two sheets, with up to four strands in each sheet, have been simulated. Here, we simulate dimers through nonamers, organized in three sheets, with three strands per sheet. In all cases, for short peptides the antiparallel orientation is preferred within the sheet. The simulations also indicate that between sheets the preferred orientation for the Aβ16–22, A8, AGAAAAGA, and the NFGAIL is parallel. On the other hand, for the longer peptides, either parallel or antiparallel strand orientation within the sheet is possible, depending on the sequence. Here, the preferred orientation is likely to be determined by the distribution of the polar (charged)/nonpolar residues along the sequence. This is clearly observed for the Aβ16–35, Aβ10–35, and Aβ1–40 sequence. The exception is the recently determined yeast prion Sup35 dehydrated β-structure of GNNQQNY. For this polar peptide, x-ray powder pattern of the microcrystals indicated parallel stranded sheets, packed against one parallel and one antiparallel sheets (Balbirnie et al., 2001).

Combining experiment and MD, we may infer that for the shorter peptides the effect of the electric dipole due to the polarity of the conformation may play a crucial role in strand orientation, driving the system into a preferred antiparallel organization. The longer the peptide, the less important is the effect of the helical dipole. For the longer peptide, the interactions acquire the dominant role in the bulk system (Ma and Nussinov, 2002a). However, it is the sequence matching that determines if the antiparallel organization will be stable, or disintegrate. We have previously investigated a repetitive prion sequence (AGAAAAGA). We observed that the correct matching of the side chains determined the stability of these complexes, over the effect of the ionic strength or the pH (Ma and Nussinov, 2002a). Even though that sequence had two types of small amino acids, Gly and Ala, the structural integrity of the supramolecular organization was tightly linked to the interstrand interactions between sheets. In the NFGAIL sequence, a subtle difference arises due to the chemical nature of its residues types. NFGAIL forms stable amyloids, whereas NAGAIL does not (Azriel and Gazit, 2001). The peptide is unable to sustain a stable amyloid after this mutation. The sequence matching observed in all our simulations becomes even more critical when we consider the aromatic residues. This leads us to conclude that the driving force in amyloid formation is the combination of the general hydrophobic effect and, if present, the particular structural properties of the aromatic groups. The aromatics can interact nonspecifically with the hydrophobic residues and, at the same time, form cooperative interactions with other aromatic residues. For the NFGAIL, the effect of the Ala substitution is particularly dramatic, because an aromatic residue in a short peptide is exchanged by a residue with a small side chain. Moreover, Ala substitutions at other positions in the NFGAIL did not alter the capability of the NFGAIL peptide to form fibrils, even though Ala has a high propensity to adopt an α-helix conformation. This differential effect points to the important role of the aromatic residues in maintaining the integrity of the fibril. To get further insight into this point, we enlarge our investigation by mutating the aromatic residue for a bulky hydrophobic one (Ile and Leu). As in the Ala substitutions, the association is unstable and disintegrates in the long simulations (unpublished data). Nevertheless, for these Ile and Leu substitutions, the effect was not as dramatic as for the Ala mutant. In particular, we note that the F23L mutation still enables the bulk system to maintain a certain degree of β-sheet organization.

The simulations further indicate that amyloidogenesis is not a process that initiates by association of strands that later will belong to the same sheet. Viewing amyloidogenesis in this way implicitly considers hydrogen bonds as playing a dominant role. In contrast, our results suggest that hydrogen bonds are a consequence of the aggregation, i.e., the hydrophobic effect. Such a scenario is justified by the lack of homogeneity in strand orientation. Further, seed formation is likely to be related to some nonspecific association of several strands of an eventual, future hydrophobic pocket. The spatial strand proximity allows hydrogen bond formation, leading to further stabilization. Such a scenario is further consistent by recent kinetic studies indicating the existence of α-helical oligomer intermediates (Kirkitadze et al., 2001).

There is considerable mutational data on the IAPP. For residues 20–29, Moriarty and Raleigh (1999) have systematically mutated every residue by proline. Their results have demonstrated that a proline substitution at positions 20, 21, or 29 (Ser, Asn, Ser) has a lesser effect on amyloid formation than substitutions at positions 22–28. They concluded that these results illustrate the importance of central residues in the peptide, as compared to end residues. Westermark et al. (1990) note that position 25 is more tolerant to substitutions than other core residues. However, Pro at this position still has a noticeable effect on amyloid formation, consistent with its being a central residue in this peptide (Moriarty and Raleigh, 1999). Because we have not simulated the 20–29 fragment, we cannot comment directly on the effect of these positions. Nevertheless, should this 10-residue fragment also be organized in an antiparallel orientation, the same residues would be expected to be in register as in our 22–27 fragment. However, the stability of a 10-residue fragment is likely to be enhanced as compared to our hexamer, tolerating some of the proline substitutions.

Based on the analysis of amyloidogenic sequences and interactions in self-assembled systems, Gazit suggested that aromatic (stacking) interactions are one of the key factors in amyloid formation and stabilization (Gazit, 2002). Our results validate the effect of the aromatics. In our most stable model (antiparallel strands, parallel sheets) there are recurring ring interactions via a T-shape organization between the Phe of different sheets. Moreover, there are recurring interactions between large nonpolar residues (Ile and/or Leu) and Phe leading to a distinct microorganization in the intersheet box. At the same time, experiments show the importance of Phe for amyloid formation. In its absence, the self-assembly event is unreachable (Azriel and Gazit, 2001). This is also observed in our simulations. Experiments further indicated that the substitution of one nonpolar residue by an Ala slowed the fibrillogenesis but did not stop it. This is again in agreement with our proposition. The longer timescale can be a consequence of a random selection that each soluble polypeptide chain might go through, until some of the hydrophobic residues establish a tight enough interaction to initiate the self-assembly process.

Our results suggest that depending on the sequence, a hexamer can already form a minimal seed size, although a nonamer is more stable. Even though an exposed sheet in the hexamer becomes buried in the nonamer, the preferred interactions and strand/sheet organization do not change. This suggests a common mechanism. Further, both experimental solid-state NMR results (Antzukutkin et al., 2000), and simulations (Ma and Nussinov, 2002b) suggest that even for longer peptides, the amyloids are formed not by curling into single molecule-component sheets, but rather by contributing a single strand. If this strand is too long for a stable sheet, as in the case of Aβ, the sheet appears to bend, forming a hooklike double-layered sheet (Tycko, personal communication; Ma and Nussinov, 2002b). This may further suggest that a protein may partially unfold to contribute a strand to an amyloid fibril, rather than completely unfold to refold into a complete β-sheet structure. Such a mechanism is consistent with the recent observation of Chiti et al. (2002), indicating that different regions in the proteins are responsible for folding and for aggregation.

Our conclusions are consistent with the kinetics of amyloid formation. Amyloid kinetics follows a particular pattern that implies preformation of a basic structural motif, which further induces the formation of the seed. Consideration of the timescale involved in seed formation may suggest that the driving force is specific enough to allow the interchain association, but loose enough to favor the interaction between protein segments that may still be partially folded.

Nevertheless, this simple mechanistic model does not explain some features recently observed in the amyloidogenicity of the entire Aβ protein. Kirkitadze et al. (2001) have demonstrated that during the assembly process, there are some intermediates with secondary structure. Instead of a direct transition from a coiled conformation to an association of partially extended strands, they detected the presence of partially helical peptides in the early stages of fibrillogenesis. These partially helical conformers were observed to form oligomeric assemblies. Further, helices in transmembrane and in soluble globular proteins often similarly interact through their exposed nonpolar side chains. An intermediate oligomeric α-helix-containing assembly is consistent with a disordered region forming a partial helix, with subsequent conversion to a β-strand. Rather than a helix converting to a β-sheet with a sheet-sheet interaction, a locally unfolded helix may interact with an oligomer, whether as a short helix as in our case here, or a long partially unfolded helix contributing to a growing bent double-layered sheet conformation (Ma and Nussinov, 2002b; R. Tycko, personal communication) as in the 40-residue Aβ. Such a mechanism could operate for parallel or for antiparallel strand organization. This does not necessarily imply that helix formation is an obligatory step. However, a coil-to-helix, and helix-to-β-conformation have lower energetic barriers and consequently shorter timescales than a direct coil-to-β-conformational transition.

To conclude, consistent with experiments, the simulations clearly indicate that the driving force for amyloid formation is the hydrophobic effect and that sequence matching is a critical factor in amyloid organization. Nevertheless, additionally, to form and to maintain a regular β-superhelix that can extend over large distances, both the side chains have to match and the backbone should not be obstructed so it can adopt such a regular conformation. Double methylation of the backbone of the core NFGAIL sequence inhibits amyloid formation (Kapuriotu et al., 2002). The methyls not only interfere with H-bonding. Further, they obstruct formation of a regular, ordered assembly through steric effects, again showing the sensitivity of the superhelix. The simulations further indicate a minimal seed size, consistent with our previous AAAAAAAA simulations. Clearly, the organization that we observe for the NFGAIL peptide cannot be part of the entire IAPP structure, even if antiparallel strand assembly is maintained. Nevertheless, as this peptide has been shown experimentally to form fibrils microscopically similar to the parent protein and to other amyloids, its small size is particularly advantageous. It enables extensive experimentation with possible amyloid organization in an attempt to uncover the basic principles of amyloid conformation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. K. Gunasekaran, C.J. Tsai, and S. Kumar for discussions. In particular, we thank Dr. Jacob V. Maizel for encouragement. The computation times are provided by the National Cancer Institute's Frederick Advanced Biomedical Supercomputing Center and by the National Institutes of Health Biowulf.

The research of R. Nussinov in Israel has been supported in part by the Magnet grant, by the Ministry of Science grant, and by the Center of Excellence in Geometric Computing and its Applications funded by the Israel Science Foundation (administered by the Israel Academy of Sciences), and by the Adams Brain Center. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract number NO1-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the view or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organization imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

The publisher or recipient acknowledges right of the U.S. Government to retain a nonexclusive, royalty-free license in and to any copyright covering the article.

References

- Antzukutkin, O. N., J. J. Balbach, R. D. Leapman, N. W. Rizzo, J. Reed, and R. Tycko. 2000. Multiple quantum solid-state NMR indicates a parallel, not antiparallel, organization of β-sheets in Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:13045–13050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azriel, R., and E. Gazit. 2001. Analysis of the minimal amyloid-forming fragment of the islet amyloid polypeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 276:34156–34161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbach, J. J., Y. Ishii, N. O. Oleg, R. D. Leapman, N. W. Rizzo, F. Dyda, J. Reed, and R. Tykco. 2000. Amyloid fibril formation by Aβ16–22: a seven-residue fragment of the Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptide, and structural characterization by solid state NMR. Biochemistry. 39:13748–13759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbirnie, M., R. Grothe, and D. S. Eisenberg. 2001. An amyloid-forming peptide from the yeast prion Sup35 reveals a dehydrated β-sheet structure for amyloid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:2375–2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzinger, T. L., D. M. Gregory, T. S. Burkoth, H. Miller-Auer, D. G. Lynn, R. E. Botto, and S. C. Meredith. 1998. Propagating structure of Alzheimer's β-amyloid(10–35) is parallel β-sheet with residues in exact register. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:13407–13412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, R. B., R. E. Bruccoleri, B. D. Olafson, D. J. Sate, S. Swaminathan, and M. Karplus. 1983. CHARMM: a program for macromolecular energy minimization and dynamics calculations. J. Comp. Chem. 4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Bucciantini, M., E. Giannoni, F. Chiti, F. Baroni, L. Formigli, J. Zurdo, N. Taddei, G. Ramponi, C. M. Dobson, and M. Stefani. 2002. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature. 416:507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursulaya, B. D., and C. L. Brooks 3rd. 1999. Folding free energy surface of three-stranded β-sheet protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121:9946–9951. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti, P., and D. Pal. 2001. The interrelationships of side-chain and main-chain conformations in proteins. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 76:1–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiti, F., N. Taddei, F. Baroni, C. Capanni, M. Stefani, G. Ramponi, and C. M. Dobson. 2002. Kinetic partitioning of protein folding and aggregation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazit, E. 2002. A possible role for the π-stacking in self-assembly of amyloid fibrils. FASEB J. 16:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebre-Medhin, S., C. Olofsson, and H. Mulder. 2000. Islet amyloid polypeptide in the islets of Langerhans: friend or foe? Diabetologia. 43:687–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, J., and D. J. Selkoe. 2002. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 297:353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaikaran, E. T. A. S., and A. Clark. 2001. Islet amyloid and type 2 diabetes: from molecular misfolding to islet pathophysiology. Biochim. et. Biophys. Acta. 1537:179–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaikaran, E. T. A. S., C. E. Higham, L. C. Serpell, J. Zurdo, M. Gross, A. Clark, and P. E. Fraser. 2001. Identification of novel human islet amyloid polypeptide β-sheet domain and factors influencing fibrillogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 308:515–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, W. L., J. Chandrasekhar, J. D. Madura, R. W. Impey, and M. L. Klein. 1982. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- Kapuriotu, A., A. Schmauder, and K. Tenidis. 2002. Structure-based design and study of non-amyloidogenic, double N-methylated IAPP amyloid core sequences as inhibitors of IAPP amyloid formation and cytotoxicity. J. Mol. Biol. 315:339–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkitadze, M. D., M. M. Condron, and D. B. Teplow. 2001. Identification and characterization of key kinetic intermediates in amyloid β-protein fibrillogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 312:1103–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisilevsky, R. 2000. Amyloidogenesis: unquestioned answers and unanswered questions. J. Struct. Biol. 130:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno, T., K. Kobayashi, T. Maeda, K. Sato, and A. Takashima. 1996. Three-dimensional structure of the amyloid β peptide (25–35) in membrane-mimicking environment. Biochemistry. 35:16094–16104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, D. G., and S. C. Meredith. 2000. Model peptides and physicochemical approach to β-amyloids. J. Struct. Biol. 130:153–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B., and R. Nussinov. 2002a. Molecular dynamics simulations of alanine rich β-sheet oligomers: insights into amyloid formation. Protein. Sci. 11:2335–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B., and R. Nussinov. 2002b. Stabilities and conformations of Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptide oligomers (Aβ16–22, Aβ16–35, Aβ10–35): Sequence effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:14126–14131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKerell, J. A. D., D. Bashford, M. Bellott, Jr., R. L. Dunbrack, J. Evanseck, M. J. Field, S. Fidcher, J. Gao, H. Guo, S. Ha, D. Joseph, L. Kuchnir, K. Kuczera, F. K. T. Lau, C. Mattos, S. Michnick, T. Ngo, D. T. Nguyen, B. Prodhom, L. W. E. Reiner, B. Roux, M. Schlenkrich, J. Smith, R. Stote, J. Straub, M. Watanabe, J. Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera, D. Yin, and M. Karplus. 1998. All-hydrogen empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins using the CHARMM22 force field. J. Phys. Chem. B. 102:3586–3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R. P., J. D. Estermyer, J. F. Kelly, and P. E. Mason. 1996. Alzheimer's disease of amyloid β-peptide 25–35 is located in membrane hydrocarbon core: x-ray diffraction analysis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 222:78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty, D. F., and D. P. Raleigh. 1999. Effects of sequential proline substitutions on amyloid formation by human amylin20–29. Biochemistry. 38:1811–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilson, R. M., and D. Raleigh. 1999. Analysis of amylin cleavage products provides new insights into amyloidogenic region of human amylin. J. Mol. Biol. 294:1375–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padrick, S. B., and A. D. Miranker. 2001. Islet amyloid polypeptide: identification of long-range contacts and local order on the fibrillogenesis pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 308:783–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochet, J. C., and P. T. Lansbury, Jr. 2000. Amyloid fibrillogenesis: themes and variations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10:60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckaert, J. P., G. Ciccoti, and H. J. C. Berendsen. 1977. Numerical integration of the Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Sunde, M., and C. F. F. Blake. 1998. From the globular to the fibrous state: protein structure and structural conversion in amyloid formation. Q. Rev. Biophys. 31:1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenidis, K., M. Waldner, J. Bernhagen, W. Fischle, M. Bergmann, M. Weber, M. L. Merkle, W. Voelter, H. Brunner, and A. Kapurniotu. 1999. Identification of penta- and hexapeptide of islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) with amyloidogenic and cytotoxic properties. J. Mol. Biol. 295:1055–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark, P., U. Engström, K. H. Johnson, and G. T. Westermark. 1990. Islet amyloid polypeptide: pinpointing amino acid residues linked to amyloid fibril formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87:5036–5040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]