Abstract

Horseradish peroxidase C (HRPC) binds 2 mol calcium per mol of enzyme with binding sites located distal and proximal to the heme group. The effect of calcium depletion on the conformation of the heme was investigated by combining polarized resonance Raman dispersion spectroscopy with normal coordinate structural decomposition analysis of the hemes extracted from models of Ca2+-bound and Ca2+-depleted HRPC generated and equilibrated using molecular dynamics simulations. Results show that calcium removal causes reorientation of heme pocket residues. We propose that these rearrangements significantly affect both the in-plane and out-of-plane deformations of the heme. Analysis of the experimental depolarization ratios are clearly consistent with increased B1g- and B2g-type distortions in the Ca2+-depleted species while the normal coordinate structural decomposition results are indicative of increased planarity for the heme of Ca2+-depleted HRPC and of significant changes in the relative contributions of three of the six lowest frequency deformations. Most noteworthy is the decrease of the strong saddling deformation that is typical of all peroxidases, and an increase in ruffling. Our results confirm previous work proposing that calcium is required to maintain the structural integrity of the heme in that we show that the preferred geometry for catalysis is lost upon calcium depletion.

INTRODUCTION

Horseradish peroxidase is a secretory plant peroxidase that catalyzes the oxidation of small aromatic substrates, such as plant hormones and lignin precursors, by hydrogen peroxide (Dunford, 1991; Smith and Veitch, 1998). Isoenzyme C (HRPC) is the most abundant isoenzyme found in horseradish roots. In the resting state, the HRPC prosthetic group is a typical class III peroxidase pentacoordinate ferric heme b with the iron described as a quantum mixed state (QMS) consisting of a low contribution from an intermediate spin (IS) species admixed with a predominant high spin (HS) state (Maltempo and Moss, 1976; La Mar et al., 1980; de Ropp et al., 1997; Howes et al., 2001; Smulevich, 1998). Class III peroxidases are also characterized by the presence of two calcium binding sites, respectively proximal and distal to the heme. The x-ray crystal structure of HRPC (Gajhede et al., 1997) shows that the proximal Ca2+ ion is located at 13.52 Å from the heme iron and the distal at 15.93 Å (Fig. 1). The role of calcium has been the object of several studies showing that Ca2+ binding is essential for catalysis and maintaining the structural features of the enzyme required for its catalytic activity (Haschke and Friedhoff, 1978; Morishima et al., 1986; Shiro et al., 1986; Smith et al., 1990; Chattopadhyay and Mazumdar, 2000). Ca2+ has also been shown to be required for the stability of the enzyme: in the presence of calcium, the free-energy change during unfolding is 16.7 kJ/mol for the native enzyme compared to 9.2 kJ/mol in the absence of Ca2+ (Pappa and Cass, 1993).

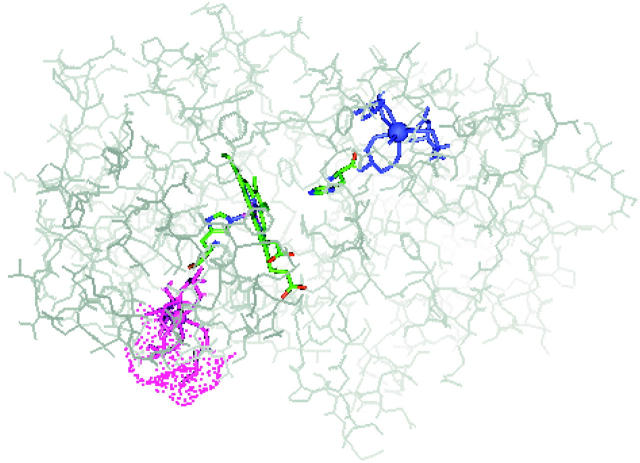

FIGURE 1.

The seven-coordinate calcium binding sites in HRPC. The proximal site (purple) is partially solvent-exposed (dotted surface) in a more flexible region of the protein while the distal site (blue) is buried in the protein core. Image from the energy-minimized structure generated using the 1ATJ.PDB coordinates (Gajhede et al., 1997). Solvent-accessible surface (115.92 Å) was calculated using the Connolly algorithm (Connolly, 1983) with a 1.4-Å probe radius.

The effect of the proximal Ca2+ ion on the heme environment was recently investigated by electronic absorption and resonance Raman spectroscopy by Howes et al. who showed that the QMS of the Fe3+ heme was slightly altered upon removal of the proximal Ca2+ ion, increasing the IS contribution (Howes et al., 2001). Using resonance Raman spectroscopy and total reflection x-ray fluorescence, we recently further investigated the effect of Ca2+ depletion on the spin state of the iron and observed a predominantly pentacoordinate Fe3+ HS spectrum upon further Ca2+ depletion (Huang et al., 2003). Our results suggest that complete removal of calcium in both binding sites is required to significantly affect the spin state of the iron (Fig. 1). This interpretation is consistent with earlier studies suggesting that the two HRPC Ca2+ ions were not equivalent in that only one seemed essential to finetune the structural environment of the active site (Ogawa et al., 1979) and also with reports indicative of a ∼50% loss of activity upon removal of both or one calcium (Haschke and Friedhoff, 1978; Morishima et al., 1986; Shiro et al., 1986; Howes et al., 2001). Our results also showed that the Ca2+ binding sites of HRPC require further characterization.

In this work, we use Polarized Resonance Raman Dispersion Spectroscopy (PRRDS) to investigate the heme distortions resulting from partial Ca2+ removal. We also use molecular dynamics simulations (MDS) to generate equilibrated structural models of HRPC and of the Ca2+-depleted species from the available x-ray structure (Gajhede et al., 1997). Further, we extract the hemes from the averaged MDS trajectory structures and subject them to normal coordinate structural decomposition (NSD). The NSD method has been used extensively to describe and analyze the out-of-plane distortions of porphyrins in heme proteins (Shelnutt, 2000). It classifies the porphyrin distortions in terms of equivalent displacements along the lowest frequency normal coordinate of the porphyrin and provides a computational procedure allowing to determine the out-of-plane and in-plane displacements along all the normal coordinates of the porphyrin (Jentzen et al., 1997). NSD results have been published characterizing the out-of-plane distortions of peroxidases belonging to different classes (Jentzen et al., 1998; Howes et al., 1999) and it was recently applied to study the calcium-dependent conformation of a heme in a diheme peroxidase (Pauleta et al., 2001), thus providing a database for comparison.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation

Horseradish peroxidase isoenzyme C (code HRP4B) was purchased from Biozyme Laboratories Ltd. (San Diego, CA). This preparation has a Reinheitszahl (RZ) of ∼3.4 and contains 90% isoenzyme C and it was used without further purification. Calcium was partially removed following the procedure of Haschke and Friedhoff (1978). To achieve depletion of one mole of calcium, the enzyme was dissolved in 100 mM Tris/HCl pH 8 and incubated for 4 h in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride in 10 mM EDTA at room temperature, followed by 12 h dialysis against 5 mM EDTA, pH 7 and 4 h dialysis against water. As reported elsewhere (Huang et al., 2003), total reflection x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy was used to analyze the calcium contents of this preparation which yields 0.43 mol of Ca2+/mole of enzyme. PRRDS measurements were performed on 1 mM native and Ca2+-depleted HRPC dissolved in 50 mM Tris/HCl buffer at pH 8.0.

Polarized resonance Raman spectroscopy

All Raman spectra were measured in 135° backscattering geometry using a tunable Argon ion laser (Lexel 95). Its excitation radiation lines cover the resonant region of the Q-band of HRP. The laser beam, polarized perpendicular to the scattering plane, was filtered by a set of interference filters and focused onto a sample in a quartz cell mounted in a macro-chamber at room temperature. The laser power was adjusted to values between 10 mW to 50 mW depending of the excitation wavelength used. The scattered light was collimated and collected by an imaging lens system into an entrance slit of 100 um width of a triple-grating spectrometer (Jobin-Ivon). Polarization analyzer and scrambler were inserted between collimator and entrance slit of the spectrometer in order to measure the two components polarized perpendicular (Iy) and parallel (Ix) to the polarization of the incident laser beam. The scattered light was then dispersed by a Jobin Ivon T65000 triple monochromator, which is equipped with 1800 groove/mm gratings. The photons were counted with a liquid nitrogen cooled CCD camera (CCD3000 from Jobin-Ivon) with 1024 × 512 pixel array chip. The data were digitized and stored on a Dell computer with Pentium III processor for further analysis. The spectral resolution of the spectrometer ranged from 3.8 cm−1 (457.9 nm) to 2.8 cm−1 (514.5 nm). Calibrated with 934 cm−1 of ClO4−, the recorded Raman spectra have an accuracy of 1 cm−1.

All spectra were analyzed by the program MULTIFIT (Jentzen et al., 1996). Each Raman band was fitted with a Voigtian profile, which results from the convolution of its Lorentzian line profile and the Gaussian line profile of spectrometer slit function. The spectra were decomposed consistently by using identical parameters such as half-width, frequency position, and band profile for all eight excitation wavelengths. Thus, the observed spectra were subjected to a global fit. Many attempts with different guess values for the spectral parameters were carried out and the best fitting parameters and the respective statistical errors were found with the smallest χ2-values. The intensities of the polarized bands were derived from their band areas. The depolarization ratios ρ of the spectral lines were calculated as

|

where Ix and Iy were measured parallel and perpendicular to the polarization of the exciting laser beam. The accuracy of the depolarization ratio was verified with the 216 cm−1 line of CCl4. The measured depolarization ratio was found to be identical with its expectation value of 0.75 ± 0.02 at all excitation wavelengths. The depolarization ratio of the 934 cm−1 line of the internal standard ClO4− was always close to 0, as theoretically expected. This shows that the contamination by the collimator optics is negligibly small for polarized and depolarized lines.

COMPUTATIONAL METHODS

Generating the models and energy minimization

All simulations were performed using the academic CHARMM version 27 (Brooks et al., 1983; MacKerell et al., 1998) on a Silicon Graphics R-10000 O2 workstation linked to the NIIF supercomputing environment. The x-ray coordinates of HRPC were obtained from the RCSB protein database (Bernstein et al., 1977); namely PDB1ATJ.ENT (Gajhede et al., 1997). The structure was corrected for x-ray disordered and modified regions. Specifically, Met1, introduced for gene expression, was removed and Asn307 and Ser308, disordered and not included in the coordinates, were added in extended mode using the Biopolymer module of the InsightII software package (Accelerys, San Diego, CA). The stereochemical quality of the model was verified using the PROCHECK program (Laskowski et al., 1993) and three calcium-depleted models were generated by removing the proximal calcium site, the distal site and finally, both calciums.

Parameterization

Charges for the ferric heme and the Ca2+-coordination spheres were calculated at the Hartree-Fock level using a 6-311G basis set and electrostatic potential fitting as previously described (Schay et al., 2001) and incorporated into CHARMM. van der Waals parameters were from Cates et al. (2002).

Energy minimization

All crystallographic water molecules were retained (151, less one molecule which is a ligand to Ca352) since they have been shown to have an important structural role by participating in the H-bond network, especially the waters found in the heme crevice (Gajhede et al., 1997). Explicit hydrogens were added using the HBUILD module and the amino acid residues were protonated so as to be consistent with neutral pH. The propionic acid side chains were also considered ionized as discussed elsewhere (Schay et al., 2001) and the disulfide bridges were explicitly modeled, namely: Cys11-Cys91, Cys44-Cys49, Cys97-Cys301, and Cys177-Cys209. The structures were solvated in a 36-Å sphere of 5000 explicit TIP3 waters (Jorgensen et al., 1983) using a spherical shape quartic boundary potential within the Miscellaneous Mean Field Potential approximation as implemented in CHARMM. All models were subjected to the same energy minimization protocol. First, the hydrogens of the solvent waters were relaxed while imposing fixed constraints on all other atoms with 30 steps of steepest descent minimization. Then the solvent was relaxed keeping the protein constrained. Finally, harmonic constraints were used to progressively relax the R-groups, then the backbone and the heme group from 240 to 0 kcal mol−1 using conjugate gradient minimization until the derivatives reached 0.9 mol−1 Å−1. An Adopted Basis Newton-Raphson final minimization of all models completed the minimization protocol with final derivatives of 0.06 mol−1 Å−1.

Molecular dynamics

Molecular dynamics were performed using the SHAKE algorithm so as to remove the highest frequencies from the system and allow use of a 0.001 ps timestep for integration. The van der Waals cutoff distance was 14 Å using a smooth switching function at a distance of 10.0 Å and a shifting function was used for the electrostatic interactions at a cutoff of 13.0 Å. A dielectric constant of 1 was used. The structures were brought to 300 K in 10 ps using a stepwise heating stage. The heating stage was followed by an equilibration stage until energy stabilized. After a 50 ps-equilibration stage, 200-ps trajectories were acquired for analysis. The average structure was calculated for all 4 trajectories and subjected to progressive energy minimization as described above until the derivatives reached 0.3 mol−1 Å−1.

Normal coordinate structural decomposition

The hemes of the four models were extracted for NSD, performed using version 2.0 of the NSD program (Jentzen et al., 1997) with the hemes oriented as shown in Fig. 2. The computational procedure is based on group theory in that the atomic distortions of the 24 porphyrin atoms from ideal D4h symmetry can be described in terms of 3N − 6 = 66 normal coordinates. The program projects out the out-of-plane and in-plane distortions along all the 66 normal coordinates of the porphyrin. For heme proteins however, it has been shown that the total distortion from planarity can statistically be adequately described by using only the six lowest out-of-plane frequency modes, namely B2u, B1u, Eg(x), Eg(y), A1u, and A2u because these modes contribute the most to heme nonplanarity (Jentzen et al., 1997; Jentzen et al., 1998).

FIGURE 2.

Orientation of the heme for the NSD calculations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RR high frequency skeletal heme vibrational modes

Polarized RR spectra were recorded at all excitation wavelengths of an Argon ion laser. This allowed us to determine the spectral parameters of the totally symmetric A1g modes as well as those of the B1g, A2g, and B2g in-plane modes. Table 1 lists the line frequencies, their D4h symmetry classification and assignments for both native and Ca2+-depleted HRPC at pH 8.0 in the high frequency region and Fig. 3 presents representative spectra. The lines observed in this region are well-known markers of oxidation state, spin state (Spiro and Strekas, 1974; Spiro, 1978) and porphyrin nonplanar distortions (Shelnutt, 2000). The most striking difference resulting from calcium removal is the loss of QMS character by Fe3+, as shown by the significant loss of intensity of ν11 in the Ca2+-depleted spectrum and upshifted ν10c (compare to Table 1). The observed increase of the weak ν10c+ from 1637 to 1640 cm−1 upon calcium depletion is indicative of a small population of the hc-ls state remaining after stabilization of the major pc-hs state. More importantly, our results point to a reorganization of the ligand field strength in the active site.

TABLE 1.

Frequencies (cm−1) of the RR lines of native and Ca2+-depleted HRPC

| Mode | HRPC | Ca2+- depleted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ν21 (A2g) | 1304 | pc-hs¶ | 1307 | pc-hs¶ |

| ν4 (A1g) | 1373 | pc-hs¶ | 1373 | pc-hs¶ |

| ν3a (A1g) | 1492w | pc-hs‡ | 1492s | pc-hs‡ |

| ν3b (A1g) | 1499s | pc-qms‡ | 1499w | |

| ν11 (B1g) | 1546s | pc-qms‡ | 1546w | pc-qms‡ |

| ν19a (A2g) | 1574/1576 | pc-hs†/qms-hs‡ | 1568 | hc-hs*† |

| ν2 (A1g) | 1572 | pc-hs*† | 1572 | pc-hs*† |

| ν19b (A2g) | 1586 | hc-ls* | 1589 | hc-ls* |

| ν37 (Eu) | 1584 | Qms§ | 1595 | pc-hs* |

| ν10a (B1g) | 1621w | hc-hs‡ | 1621w | hc-hs‡ |

| ν10b (B1g) | 1629 | pc-hs‡ | 1629 | pc-hs‡ |

| ν10c (B1g) | 1637s | pc-qms‡ | 1640w | hc-ls‡ |

Huang et al. (2003).

This article.

FIGURE 3.

Polarized Raman spectra of native Ca2+-depleted HRPC (pH 8) excited at 476.5 and 457.9 nm (a) and at 514.5 and 496.5 nm (b), which cover both B-preresonance and Qv-resonance excitation.

Polarized resonance Raman dispersion spectroscopy

The depolarization ratio dispersion of Ca2+-free HRP is compared to that of the native enzyme in Fig. 4. We selected three typical Raman bands, i.e., ν4 (A1g), ν21 (A2g), and ν11 (B1g), for analysis. In Fig. 4 a, for both samples, the DPRs of the ν4 band are above 0.125 and increase with excitation wavelengths in the Qv -band excitation region. The ν4 DPRs of Ca2+-free HRPC are systematically larger than the DPRs of the native species. Theoretical simulations of A1g mode depolarization ratios have shown that the dispersion and increase of DPRs can arise from B1g and B2g perturbations which predominantly arise from rhombic distortions along the Npyrr-Fe-Npyrr line and from triclinic distortions involving displacements along the Cm-Fe-Cm lines and deformations of the pyrrole rings, respectively (Schweitzer-Stenner, 2001). Accordingly, the larger DPRs observed in Ca2+-depleted HRPC are indicative of increased rhombic and triclinic distortions upon calcium removal from HRPC. The axial ligand (His 170) is a good candidate to induce precisely this type of deformation and it is likely that the larger DPRs of Ca2+-depleted HRPC reflect a distortion of its imidazole ring which can be brought about by a rotation either toward the methine carbon line (increase of B2g distortion) or toward the Npyrr-Fe-Npyrr line (increase of B1g distortion) and/or a shorter distance between the ligand and the iron (increase of B1g and B2g distortions) or a combination of all these effects.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of DPRs for native and Ca2+-depleted HRPC: ν4 (top), ν21 (middle), and ν11 (bottom).

Fig. 4 b compares the DPRs of native and Ca2+-depleted HRPC for antisymmetric ν21 (A2g). The DPRs are further decreased by Ca2+-removal, consistent with the notion that additional rhombic distortions are induced. Interestingly, some DPR-values of Ca2+-free HRPC at shorter wavelengths are near or even below 0.75. These could be brought about by the product of ruffling and saddling (B2u ⊗ B1u = A1g) or by antisymmetric in-plane A2g-type distortions, which have been shown to provide detectable contributions of A1g-perturbation type in porphyrin systems (Schweitzer-Stenner et al., 2001).

Fig. 4 c compares the DPRs of the B1g type mode ν11 between native and Ca2+-depleted HRPC. The DPRs of ν11 in the Ca2+-depleted species increase monotonically with excitation wavelength, and cross both the expectation line of 0.75 under D4h and the DPR curve of ν11 in native HRPC. This shows that this mode is subject to A2g-type and A1g-type vibronic perturbations resulting from B2g and B1g in-plane distortions of the macrocycle, respectively. The dispersion is more pronounced for Ca2+-depleted HRPC, indicating that both types of distortions increase with respect to native HRPC. In fact, the contribution of A1g-perturbation/B1g-distortion which gives rise to the DPR decrease at higher excitation wave numbers must be considered as particularly strong, since the excitation is still far away from the B-band resonance position at which such an effect would be expected to be maximal. If all these observations involve the proximal histidine, it follows that the type of perturbations induced by Ca2+ removal could cause both a decrease of the His:NE2-Fe distance or a smaller azimuthal angle of the imidazole ring with respect to the N-Fe-N line, as theoretically argued elsewhere (Schweitzer-Stenner, 1989).

Molecular dynamics

All structures were subjected to initial 50-ps equilibration MDS runs which yielded fully equilibrated structures after ∼20 ps. These runs were followed by the acquisition of 200-ps production trajectories. All runs were quite stable as shown by their constant potential energies and temperature. The energy minimization protocol was also successful in reaching comparable energy minima for the four models. The stability of the fluctuation of the total energy was also examined by calculating the ratio between the average rms fluctuation of the total energy and the average energy. For all models, this ratio did not exceed 0.1, thus showing that energy was conserved during the simulations and that the models were well equilibrated.

Table 2 presents some useful quantities calculated from the simulations. The radius of gyration is the radius of a sphere containing an equivalent volume to that of the molecule. With removal of one calcium, the Rgyr values do not change with respect to that of the native structure. However, complete Ca2+ removal leads to a slight expansion of the protein matrix, evidenced by the increase in the radius of gyration. The backbone and R-group RMSD values are lowest for the native structure (0.987 Å and 1.211 Å). They reflect the dynamics of the protein matrix. The values calculated for the Ca2+-depleted models (1.044, 1.163, and 1.140 Å for the backbone and 1.451, 1.543, and 1.526 Å for the R-groups) are higher and reflect an increased flexibility of the secondary structure as a result of calcium removal. Also relevant are the backbone RMSD values comparing only the effect of calcium removal. They fall in the same range (1.213, 1.220, and 1.210 Å) and attest to a role played by calcium in modifying the dynamics of HRPC. Fig. 5 shows the backbone Cα-traces of the native (top) and Ca2+-free structures. Removal of calcium does not affect the secondary structure fold to a significant extent besides relaxing it to a looser form. This is probably due to the presence of the four disulfide bridges, Cys11-Cys91, Cys44-Cys49, Cys97-Cys301, and Cys177-Cys209, that have been shown to stabilize helices A, B, C, D, F1, and F2 (Chattopadhyay and Mazumdar, 2000). The two regions showing the most backbone reorganization are on the proximal side of the heme, namely short insertion helix F′ consisting of Met181, Asp182, Arg183, and Leu 184 and part of helix H, namely Asp247 and Ser246. Fig. 6 compares the R-group displacements in the vicinity of the heme for both HRPC and the Ca2+-free model. They are quite significant especially in the reorganization of both distal and proximal Phe aromatic clusters. The distance of distal His42 to the heme iron shortens upon calcium removal from 6 to 5.5 Å and the heme pocket water closest to the iron in the native structure (3.20 Å) moves further away from the iron in the calcium-depleted species toward Arg38. All of the R-group displacements necessarily must reorganize the nonbonded interaction network at the catalytic site. Detailed 1H-NMR studies performed on HRPC have provided a detailed assignment of the hyperfine proton resonances of the heme macrocycle and of the amino acid resonances in the heme pocket (La Mar et al., 1980; Thanabal et al., 1987, 1988). A comparison with calcium-depleted HRPC would be required to experimentally verify if calcium can indeed cause residue reorientation with respect to the heme, as shown in the case of cationic peanut peroxidase (Barber et al., 1995).

TABLE 2.

Radii of gyration and RMSD values for the average structures of the 200-ps molecular dynamics simulations

| Trajectory | Rgyration | RMSbackbone | RMSR-groups | RMSHeme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRPC + 2 Ca2+ | 26.545 | 0.987 | 1.211 | 0.909 |

| HRPC + distal Ca2+ | 26.583 | 1.044 | 1.451 | 0.946 |

| 1.213 | 0.717 | |||

| HRPC + prox Ca2+ | 26.567 | 1.163 | 1.543 | 0.989 |

| 1.220 | 0.818 | |||

| Ca2+-free HRPC | 27.447 | 1.140 | 1.526 | 0.928 |

| 1.210 | 0.800 |

The first RMS value is calculated using the energy minimized structure of the same model as reference structure; the second value given for the Ca2+-depleted models is calculated using the native enzyme as reference structure.

FIGURE 5.

Stereo view of the backbone traces of the HRPC (top) and Ca2+-depleted (bottom) average structure after 200 ps of molecular dynamics.

FIGURE 6.

The effect of calcium removal in the vicinity of the heme of HRPC (left) and Ca2+-free HRPC (right). The aromatic cluster consisting of Phe41, 143, 152, and 179 on the distal side and Phe172, 221, 229, and 277 on the proximal side are rendered purple. Pro141 and His42 are yellow, and wat90 is a red sphere.

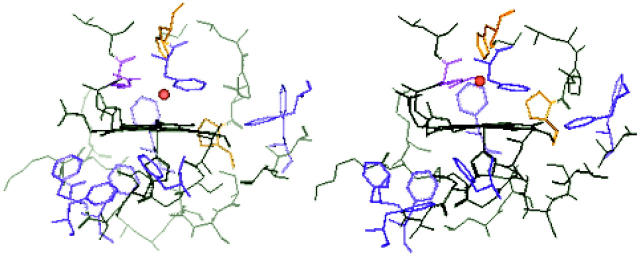

Table 3 lists heme geometry parameters. Of significant interest is that the His:NE2-Fe bond is not affected by calcium removal. Other parameters reflect the complex interaction of the different contributions to nonplanarity. As discussed above, our DPR results are indicative of increased in-plane distortions of B1g/B2g distortions. The similar His:NE2-Fe bond lengths of all four models resulting from the simulations eliminate shortening of the His:NE2-Fe distance as a possible explanation of the DPR differences between native and Ca-free HRPC. More likely is then a decrease of the azimuthal angle of the proximal imidazole ring with respect to the Npyrr-Fe-Npyrr line. This is supported by inspection of the heme structures resulting from the MDS, which clearly show that the native model has a larger azimuthal angle (Fig. 7). The decrease of the Ca2+-depleted HRPC azimuthal angles results in an increase of the steric interaction between the imidazole carbons and the pyrrole nitrogens and could thus induce the B1g-type distortions suggested by our DPR measurements.

TABLE 3.

Geometrical parameters of the hemes extracted from the average 200-ps molecular dynamics HRPC structures

| HRPC native Fe-His170:NE2 bond: 2.19 Å | Ca2+-free HRPC Fe-His170:NE2 bond: 2.17 Å | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| His170:NE2-Fe-Npyrr displacements | |||||||||

| Atom 1 | Atom 2 | Atom 3 | Angle | Atom 1 | Atom 2 | Atom 3 | Angle | ||

| 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NC | 93.86 | 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NC | 86.84 | ||

| 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NB | 89.29 | 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NB | 90.60 | ||

| 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NA | 90.52 | 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NA | 90.85 | ||

| 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:ND | 89.43 | 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:ND | 85.84 | ||

| Dihedral indicative of Cm-Fe-Cm distortion | |||||||||

| Atom 1 | Atom 2 | Atom 3 | Atom 4 | Angle | Atom 1 | Atom 2 | Atom 3 | Atom 4 | Angle |

| C4B | NB | ND | C1D | 1.93 | C4B | NB | ND | C1D | 6.66 |

| C4A | NA | NC | C1C | −1.88 | C4A | NA | NC | C1C | −11.16 |

| C4D | ND | NB | C1B | 5.31 | C4D | ND | NB | C1B | 13.33 |

| C4C | NC | NA | C1A | −3.85 | C4C | NC | NA | C1A | −11.78 |

| His170:NE2-Fe-Npyrr-Ca dihedral | |||||||||

| 170:NE2 | FE | NC | C1C | 88.63 | 170:NE2 | FE | NC | C1C | 88.69 |

| 170:NE2 | FE | NB | C1B | 94.03 | 170:NE2 | FE | NB | C1B | 102.57 |

| 170:NE2 | FE | NA | C1A | 90.02 | 170:NE2 | FE | NA | C1A | 79.84 |

| 170:NE2 | FE | ND | C1D | 87.51 | 170:NE2 | FE | ND | C1D | 84.87 |

| His170:NE2-Ca distances: ligand to closest porphyrin Ca | |||||||||

| 170:NE2 | C4C: | 3.87 | 170:NE2 | C4C: | 3.63 | ||||

| 170:NE2 | C1B: | 3.75 | 170:NE2 | C1B: | 3.86 | ||||

| 170:NE2 | C4A: | 3.82 | 170:NE2 | C4A: | 3.84 | ||||

| 170:NE2 | C1D: | 3.68 | 170:NE2 | C1D: | 3.51 | ||||

| HRPC + distal Ca2+ Fe-His170:NE2 bond: 2.18 Å

|

HRPC + proximal Ca2+ Fe-His170:NE2 bond: 2.18 Å

|

||||||||

| His170:NE2-Fe-Npyrr displacements | |||||||||

| Atom 1 | Atom 2 | Atom 3 | Angle | Atom 1 | Atom 2 | Atom 3 | Angle | ||

| 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NC | 88.46 | 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NC | 88.15 | ||

| 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NB | 87.69 | 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NB | 90.56 | ||

| 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NA | 89.31 | 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:NA | 92.14 | ||

| 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:ND | 86.63 | 170:NE2 | FE | HEM:ND | 85.49 | ||

| Dihedral indicative of Cm-Fe-Cm distortion | |||||||||

| Atom 1 | Atom 2 | Atom 3 | Atom 4 | Angle | Atom 1 | Atom 2 | Atom 3 | Atom 4 | Angle |

| C4B | NB | ND | C1D | 13.44 | C4B | NB | ND | C1D | 9.97 |

| C4A | NA | NC | C1C | −12.17 | C4A | NA | NC | C1C | −12.37 |

| C4D | ND | NB | C1B | 15.13 | C4D | ND | NB | C1B | 13.96 |

| C4C | NC | NA | C1A | 14.35 | C4C | NC | NA | C1A | 13.65 |

| His170:NE2-Fe-Npyrr-Ca dihedral | |||||||||

| 170:NE2 | FE | NC | C1C | 84.18 | 170:NE2 | FE | NC | C1C | 88.94 |

| 170:NE2 | FE | NB | C1B | 100.02 | 170:NE2 | FE | NB | C1B | 103.06 |

| 170:NE2 | FE | NA | C1A | 81.56 | 170:NE2 | FE | NA | C1A | 78.05 |

| 170:NE2 | FE | ND | C1D | 91.54 | 170:NE2 | FE | ND | C1D | 87.14 |

| His170:NE2-Ca distances: ligand to closest porphyrin Ca | |||||||||

| 170:NE2 | C4C: | 3.75 | 170:NE2 | C4C: | 3.69 | ||||

| 170:NE2 | C1B: | 3.75 | 170:NE2 | C1B: | 3.67 | ||||

| 170:NE2 | C4A: | 3.77 | 170:NE2 | C4A: | 3.90 | ||||

| 170:NE2 | C1D: | 3.63 | 170:NE2 | C1D: | 3.54 | ||||

FIGURE 7.

View of the his170 imidazole orientation with respect to the Npyrr-Fe-Npyrr line in the hemes extracted from the HRPC models. Clockwise from top left: HRPC + 2Ca2+; Ca2+-depleted HRPC; HRPC + distal Ca2+; and HRPC + distal Ca2+.

Normal coordinate structural decomposition

Fig. 8 illustrates the out-of-plane heme distortions resulting from normal coordinate structural decomposition with numerical values listed in Table 4. Overall, the major effect of Ca2+-depletion is to decrease the nonplanarity of the heme with a total deformation of 0.878 Å for the native species versus 0.560 Å for the totally Ca2+-depleted model (compare to Table 4, Doop values).

FIGURE 8.

Out-of-plane displacements in Å of the minimal basis set for the hemes in the average structures extracted from the MDS trajectories. Deformations along the six lowest frequency normal coordinates of the following D4h symmetry types: B2u (saddling), B1u (ruffling), A2u (doming), Eg(x) (x-waving), Eg(y) (y-waving), and A1u (propellering).

TABLE 4.

NSD out-of-plane displacements (in Å) along the lowest frequency normal coordinate (minimal basis) of the hemes extracted from the average MDS trajectory structure of the HRPC models

| Model | Doop* | sad B2u | ruf B1u | dom A2u | wav(x) Eg(x) | wav(y) Eg(y) | Pro A1u |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ATJ HRPC + 2 Ca2+† | 0.913 | −0.871 | −0.084 | −0.067 | −0.141 | −0.208 | −0.002 |

| HRPC + 2 Ca2+ | 0.878 | −0.841 | −0.128 | 0.042 | −0.119 | 10.176 | 0.009 |

| HRPC + distal Ca2+ | 0.773 | −0.337 | −0.597 | 0.286 | −0.003 | −0.213 | 0.006 |

| HRPC + proximal Ca2+ | 0.749 | −0.398 | −0.537 | 0.155 | 0.087 | −0.283 | −0.040 |

| Ca2+-free HRPC | 0.590 | −0.173 | −0.449 | 0.204 | −0.012 | −0.269 | −0.051 |

The pure deformation types are shown at http://jasheln.unm.edu as well as NSD results for 1579 hemes from the RCSB protein database.

Total distortions using the extended basis set, see Jentzen et al., 1997, for details.

NSD results for the “static” x-ray structure (from 1ATJ.PDB).

The native HRPC heme extracted from the trajectories exhibits the strong saddling (−0.841 Å) typical of all class III peroxidases previously examined by NSD (Jentzen et al., 1998; Howes et al., 1999). Our results on the heme extracted from the 1 ATJ x-ray structure (Table 4, row 1) are also in agreement with the NSD results first reported for these coordinates (Howes et al., 1999). The predominant saddling deformation is well conserved in both dynamic and static structures, as well as the other less significant deformations.

The NSD results are clearly different for the hemes of the Ca2+-depleted models. Calcium depletion predominantly affects the saddling and ruffling deformations. Saddling is drastically reduced in the Ca2+-free model, with a deformation of −0.173 Å compared to −0.841 Å for the native model, and −0.398 Å and −0.337 Å in the structures with either proximal or distal Ca2+ present. Ruffling, which is not significant in the native model (−0.128), increases to moderate values upon Ca2+ removal (−0.597, −0.537, and −0.449 Å). It has been proposed that ruffling has a stronger effect on the high frequency lines than an equivalent saddling deformation (Franco et al., 2000). In a recent 600-ps MDS study of the myoglobin-CO heme deformations, ruffling was shown to exhibit the largest transient deformations (exceeding 0.5 Å), which were already well characterized on the timescale of our trajectories (Kiefl et al., 2002). The authors proposed that they were probably part of ns-oscillations in heme deformations. Clearly, longer timescale trajectories are required to fully average these ruffling excursions, especially if they are correlated to tertiary structure rearrangements of the protein matrix. Our NSD results also show that the doming deformation increases and changes sign when compared to the native model. But since the His:NE2-Fe bond length does not change upon calcium removal, this doming cannot correspond to the classical displacement observed in myoglobin or hemoglobin as they cycle between oxy and deoxy forms with the concomitant significant change of axial ligand-metal bond length. It should also be noted that the doming deformation in the NSD context does not involve the iron, but only the 24 atoms of the porphyrin ring. We therefore propose that increased doming probably results from smaller distances between the imidazole carbons and the Ca and Npyrr atoms of the porphyrin which is also consistent with our observed increase of both B2g and B1g-type distortions. These could be induced by a rearrangement of the weak nonbonded interactions—such as van der Waals and hydrogen bonding (Laberge, 1998)—resulting from the sidechain reorganization occurring in the vicinity of the heme as a result of calcium removal (compare to Fig. 5). Moreover, the HRPC heme is not covalently linked to the protein matrix and is thus conceivably more sensitive to respond to altered nonbonded interactions in its vicinity.

CONCLUSIONS

In resting HRPC, calcium depletion results in reorganization of the residues of the heme pocket. These rearrangements modulate the conformation of the heme prosthetic group. Specifically, they increase B2g and B1g in-plane distortions that contribute to a change in the spin state of the iron and also increase the overall planarity of the heme. This supports the concept of nonplanar distortions providing a mechanism for the modulation of function by the protein (Shelnutt et al., 1998) and confirm the structural role of Ca2+ in maintaining the heme of HRPC in a geometry required for efficient catalysis.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Hungarian Government's National Information Infrastructure Development Program for providing computing time on the IIF parallel supercomputing environment, and J.A. Shelnutt for kindly providing the NSD program.

This research was supported by Hungarian OTKA grant T-032117 (J.F.), a Senior NATO Science Fellowship (M.L.), and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (COBRE-program, P20 RR16439-01) and the Petroleum Research Funds (PRF#38544-AC4) (R.S.S.).

References

- Barber, K. R., M. J. Rodriguez Maranon, G. S. Shaw, and R. B. Van Huystee. 1995. Structural influence of calcium on the heme cavity of cationic peanut peroxidase as determined by 1-H-NMR spectroscopy. Eur. J. Biochem. 232:825–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, F. C., T. F. Koetzle, G. J. B. Williams, E. F. Meyer, Jr., M. D. Brice, J. R. Rodgers, O. Kennard, T. Shimanouchi, and M. Tasumi. 1977. The Protein Data Bank: a computer-based archival file for macromolecular structures. Eur. J. Biochem. 80:319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, B. R., R. E. Bruccoleri, B. D. Olafson, D. J. States, S. Swaminathan, and M. Karplus. 1983. CHARMM: a program for macromolecular energy, minimization and dynamics calculations. J. Comp. Chem. 4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Cates, S., M. L. Teodoro, and G. N. Phillips, Jr. 2002. Molecular mechanisms of calcium and magnesium binding to parvalbumin. Biophys. J. 82:1133–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay, K., and S. Mazumdar. 2000. Structural and conformational stability of horseradish peroxidase: effect of temperature and pH. Biochemistry. 39:263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, M. L. 1983. Solvent-accessible surfaces of proteins and nucleic acids. Science. 221:709–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ropp, J. S., P. Mandal, L. Brauer, and G. N. La Mar. 1997. Solution NMR study of the electronic and molecular structure of the heme cavity in high-spin, resting state horseradish peroxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119:4732–4739. [Google Scholar]

- Dunford, B. H. 1991. Horseradish peroxidase: structure and kinetic properties. In Peroxidases in Chemistry and Biology. CRC Press, Boca Raton. 1–24.

- Franco, R., J. G. Ma, Y. Lu, G. C. Ferreira, and J. A. Shelnutt. 2000. Porphyrin interactions with wild-type and mutant mouse ferrochelatase. Biochemistry. 39:2517–2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajhede, M., D. J. Schuller, A. Henriksen, A. T. Smith, and T. L. Poulos. 1997. Crystal structure of horseradish peroxidase C at 2.15 Å resolution. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:1032–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haschke, R. H., and J. M. Friedhoff. 1978. Calcium-related properties of horseradish peroxidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 80:1039–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes, B. D., C. B. Schiodt, K. G. Welinder, M. P. Marzocchi, J.-G. Ma, J. Zhang, J. A. Shelnutt, and G. Smulevich. 1999. The quantum mixed-spin heme state of barley peroxidase: a paradigm for class III peroxidases. Biophys. J. 77:478–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes, B. D., A. Feis, L. Raimondi, C. Indiani, and G. Smulevich. 2001. The critical role of the proximal calcium ion in the structural properties of horseradish peroxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:40704–40711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q., M. Laberge, K. Szigeti, J. Fidy, and R. Schweitzer-Stenner. 2003. Change in the iron spin state in horseradish peroxidase C induced by calcium depletion probed by resonance Raman spectroscopy: a significant role for the distal calcium? Biospectroscopy. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jentzen, W., E. Unger, G. Karvounis, J. A. Shelnutt, W. Dreybrodt, and R. Schweitzer-Stenner. 1996. Conformational properties of nickel(II) octaethylporphyrin in solution. 1. Resonance excitation profiles and temperature dependence of structure-sensitive raman lines. J. Phys. Chem. 100:14184–14191. [Google Scholar]

- Jentzen, W., W.-Z. Song, and J. A. Shelnutt. 1997. Structural characterization of synthetic and protein-bound porphyrins in terms of the lowest-frequency normal coordinates of the macrocycle. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101:1684–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Jentzen, W., J.-G. Ma, and J. A. Shelnutt. 1998. Conservation of the conformation of the porphyrin macrocycle in hemeproteins. Biophys. J. 74:753–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, W. L., J. Chandrasekhar, J. D. Madura, R. W. Impey, and M. L. Klein. 1983. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- Kiefl, C., N. Sreerama, R. Haddad, L. Sun, W. Jentzen, Y. Lu, Y. Qiu, J. A. Shelnutt, and R. W. Woody. 2002. Heme distortions in sperm-whale carbonmonoxy myoglobin: correlations between rotational strengths and heme distortions in MD-generated structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:3385–3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge, M. 1998. Intrinsic protein electric fields: basic non-covalent interactions and relationship to protein-induced Stark effects. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1386:305–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Mar, G. N., J. S. de Ropp, K. M. Smith, and K. C. Langry. 1980. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance study of the electronic and molecular structure of the heme crevice in horseradish peroxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 255:6646–6652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R. A., M. W. MacArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton. 1993. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- MacKerell, J. A. D., B. Brooks, I. Brooks, C. L. L. Nilsson, B. B. Roux, Y. Won, and M. Karplus. 1998. CHARMM: the energy function and its parameterization with an overview of the program. In Encyclopedia of Computational Chemistry. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester. pp. 271–277.

- Maltempo, M. M., and T. H. Moss. 1976. The spin 3/2 state and quantum spin mixtures in heme proteins. Quart. Revs. Biophys. 9:181–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishima, I., M. Kurono, and Y. Shiro. 1986. Presence of endogenous calcium ion in horseradish peroxidase. Elucidation of metal-binding site by substitutions of divalent and lanthanide ions for calcium and use of metal-induced NMR (1H and 113Cd) resonances. J. Biol. Chem. 261:9391–9399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, S., Y. Shiro, and I. Morishama. 1979. Calcium binding by horseradish peroxidase C and the heme environmental structure. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 90:674–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa, H. S., and E. G. Cass. 1993. A step towards understanding the folding mechanism of horseradish peroxidase: tryptophan fluorescence and circular dichroism equilibrium studies. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993:227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauleta, S. R., Y. Lu, C. F. Goodhew, I. Moura, G. W. Pettigrew, and J. A. Shelnutt. 2001. Calcium-dependent conformation of a heme and fingerprint peptide of the diheme cytochrome c peroxidase from Paracoccus pantrophus. Biochemistry. 40:6570–6579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schay, G., R. Galantai, M. Laberge, and J. Fidy. 2001. Protein matrix local fluctuations and substrate binding in HRPC: a proposed dynamic electrostatic sampling method. Int. J. Quant. Chem. 84:290–301. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer-Stenner, R. 1989. Allosteric linkage-induced distortions of the prosthetic group in heme proteins as derived by the theoretical interpretation of the depolarization ratio in resonance Raman scattering. Q. Rev. Biophys. 22:381–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer-Stenner, R. 2001. Polarized resonance Raman dispersion spectroscopy on metalporphyrins. J. Porphyrins. Phthalocyan. 5:198–224. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer-Stenner, R., C. Lemke, R. Haddad, Y. Qiu, J. A. Shelnutt, J. M. E. Quirke, and W. Dreybrodt. 2001. Conformational distortions of metalloporphyrins with electron-withdrawing NO2 substituents at different meso positions. A structural analysis by polarized Raman dispersion spectroscopy and molecular mechanics calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A. 105:6680–6691. [Google Scholar]

- Shelnutt, J. A., X.-Z. Song, J.-G. Ma, S.-L. Jia, W. Jentzen, and C. J. Medforth. 1998. Nonplanar porphyrins and their significance in proteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 27:31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shelnutt, J. A. 2000. Molecular simulations and normal coordinate structural analysis of porphyrins and heme proteins. In The Porphyrin Handbook. Academic Press, New York. pp.167–224.

- Shiro, Y., M. Kurono, and I. Morishima. 1986. Presence of endogenous calcium ion and its functional and structural regulation in horseradish peroxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 261:9382–9390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. T., and N. C. Veitch. 1998. Substrate binding and catalysis in heme peroxidases. Curr. Op. Struct. Biol. 2:269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. T., N. Santama, S. Dacey, M. Edwards, R. C. Bray, R. N. F. Thornely, and J. F. Burke. 1990. Expression of a synthetic gene for horseradish peroxidase C in Escherichia coli and folding and activation of the recombinant enzyme with Ca2+ and heme. J. Biol. Chem. 265:13335–13343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulevich, G., A. M. English, A. R. Mantini, and M. P. Marzocchi. 1991. Resonance Raman investigation of ferric iron in horseradish peroxidase and its aromatic donor complexes at room and low temperatures. Biochemistry. 30:722–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulevich, G., M. Paoli, J. F. Burke, S. A. Sanders, R. N. Thorneley, and A. T. Smith. 1994. Characterization of recombinant horseradish peroxidase C and three site-directed mutants, F41V, F41W, and R38K, by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 33:7398–7407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulevich, G. 1998. Understanding heme cavity structure of peroxidases: comparison of electronic absorption and resonance Raman spectra with crystallographic results. Biospectroscopy. 4:S3–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro, T. G., and T. C. Strekas. 1974. Resonance Raman spectra of heme proteins. Effects of oxidation and spin state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 96:338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro, T. G. 1978. Resonance Raman spectra of hemoproteins. Methods Enzymol. 54:233–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanabal, V., J. S. de Ropp, and G. N. La Mar. 1987. Proton NMR study of the electronic and molecular structure of the heme cavity in horseradish peroxidase. Complete heme resonance assignments based on saturation transfer and nuclear Overhauser effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109:265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Thanabal, V., J. S. de Ropp, and G. N. La Mar. 1988. Proton NMR characterization of the catalytically relevant proximal and distal hydrogen-bonding networks in ligated resting state horseradish peroxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 110:3027–3035. [Google Scholar]