Abstract

We have examined the temperature dependence of the intramolecular electron transfer (ET) between heme b and heme o3 in CO-mixed valence cytochrome bo3 (Cbo) from Escherichia coli. Upon photolysis of CO-mixed valence Cbo rapid ET occurs between heme o3 and heme b with a rate constant of 2.2 × 105 s−1 at room temperature. The corresponding rate of CO recombination is found to be 86 s−1. From Eyring plots the activation energies for these two processes are found to be 3.4 kcal/mol and 6.7 kcal/mol for the ligand binding and ET reactions, respectively. Using variants of the Marcus equation the reorganization energy (λ), electronic coupling factor (HAB), and the ET distance were found to be 1.4 ± 0.2 eV, (2 ± 1) × 10−3 eV, and 9 ± 1 Å, respectively. These values are quite distinct from the analogous values previously obtained for bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) (0.76 eV, 9.9 × 10−5 eV, 13.2 Å). The differences in mechanisms/pathways for heme b/heme o3 and heme a/heme a3 ET suggested by the Marcus parameters can be attributed to structural changes at the CuB site upon change in oxidation state as well as differences in electronic coupling pathways between Heme b and heme o3.

INTRODUCTION

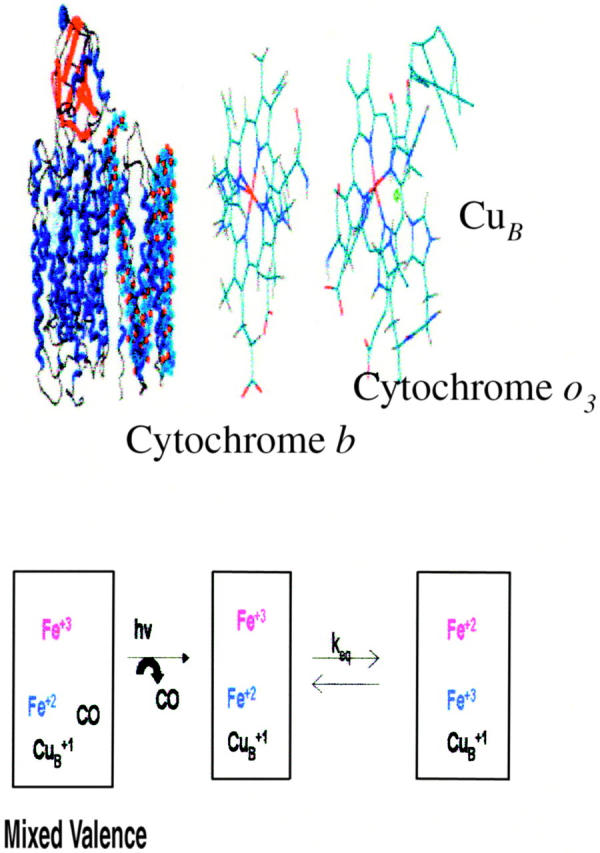

Heme/copper oxidases form a diverse class of respiratory proteins found in nearly all aerobic organisms (Gennis, 1998; Musser et al., 1995; Wikstrom et al., 1981). Although these enzymes range in molecular weight and subunit composition, several common features are found throughout the class. The majority of heme/copper oxidases contain at least three subunits (SU I, SU II, and SU III) with SU I containing the majority of the redox active metal centers. In addition, these enzymes contain two heme chromophores (heme a, heme b, and/or heme o) and at least one copper ion (Fig. 1). One of the two hemes contains a six-coordinate low-spin heme iron that functions as a catalyst for electron transfer to the binuclear center. The binuclear center consists of the remaining heme (designated heme a3, heme o3, or heme b3 depending upon the organism), which contains a five-coordinate high-spin heme iron and a copper ion (designated CuB). In addition, heme/copper oxidases from higher organisms contain an additional binuclear copper cluster (designated CuA) that accepts electrons from cytochrome c. All members of this class catalyze the four electron reduction of dioxygen to water and it is widely believed that most of these enzymes are energy transducing, i.e., they couple redox energy to the active transport of protons across a membrane.

FIGURE 1.

Structural diagram of Cytochrome bo3 from E. coli (top left) and the metal center orientation (top right). The bottom diagram describes the ET reaction being monitored subsequent to photolysis of the mixed valence derivative of the enzyme.

Cytochrome bo3 is a member of a class of terminal oxidase in the respiratory chains of aerobic bacteria. The most widely studied enzyme is that from Escherichia coli. This enzyme contains four subunits, two distinct hemes (heme b and heme o3), and one copper ion (designated CuB) with an overall molecular weight of ∼100 kDa (Puustinen et al., 1989; Anraku and Gennis, 1987). Of key interest is the fact that this enzyme shares considerable sequence similarity with mammalian cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) (Anraku and Gennis, 1987). This similarity occurs between the three mitochondrially coded subunits (designated COI, COII, and COIII) of the mammalian enzyme and cytochrome bo3 (Cbo) subunits cyoB, cyoA, and cyoC. The similarity between COI (which contains the cytochrome a and the binuclear cluster) and cyoB is as high as 37%. In addition, the conserved residues associated with metal axial ligands in COI are conserved in cyoB indicating that this subunit contains the heme b and a binuclear heme o/CuB cluster. The similarity between the CuA containing COII and cyoA is less pronounced (10%) but hydropathy plots show striking similarities. In addition, cyoA lacks the putative CuA ligands. The similarity between COIII (believed to play a significant role in proton translocation (Ogunjimi et al., 2000)) and cyoC (23%) is greater than that between COII/cyoA but less than COI/cyoB. In addition, spheroplasts from a strain of aerobically grown E. coli that lacks the cytochrome d gene also exhibit active proton transport across the membrane barrier similar to cytochrome c reductase and CcO (Anraku and Gennis, 1987).

Understanding the thermodynamics associated with each electron transfer step is necessary for an understanding of the mechanism through which Cbo conserves redox energy via active proton transport. Previous studies have shown that Cbo can be prepared in a form in which the heme o3-CuB binuclear center is reduced (i.e., Fe2+/Cu1+) with CO bound to cytochrome o3 whereas heme b remains in the Fe3+ form (CO-mixed valence form) (Morgan et al., 1993; Brown et al., 1994). Photolysis of CO from heme o3 results in rapid electron transfer from heme o3 to heme b with a rate constant of ∼3 × 105 s−1 (Fig. 1). Both CcO from bovine heart muscle and the bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides can also form CO-mixed valence derivatives (Morgan et al., 1989; Adelroth et al., 1995; Brzezinski, 1996; Einarsdottir et al., 1992). With these enzymes, the rate constants for intramolecular electron transfer between heme a3 and heme a are also roughly 1 × 105 s−1 (Morgan et al., 1989; Adelroth et al., 1995). In addition, CcO from both bovine heart muscle and Rhodobacter sphaeroides contain a low potential mixed valence CuA center and subsequent electron transfer from heme a to CuA occurs with a rate constant of ∼6 × 104 s−1 (Morgan et al., 1989; Adelroth et al., 1995). Furthermore, temperature dependence of these rate constants have allowed for the determination of the reorganizational energy (λ) and electronic coupling factors (HAB) for the various electron transfer (ET) reactions in these enzymes. In the case of bovine heart CcO, λ for ET between heme a and heme a3 is found to be 0.76 eV with an HAB of ∼1 × 10−4 eV (Adelroth et al., 1995; Brzezinski, 1996). The corresponding values for ET between heme a and CuA were found to be 0.3 eV and 4.0 × 10−6 eV, respectively. For the bacterial enzyme λ was found to be 1.2 eV with an HAB of ∼9 × 10−4 eV (Adelroth et al., 1995; Brzezinski, 1996). The values of λ and HAB for ET between heme a and CuA in the bacterial enzyme could not be determined due to a low amplitude for this phase in the transient absorption spectrum. What is particularly intriguing is that the rate constants for intramolecular ET between heme a and heme a3 are nearly identical despite a large difference in reaction driving force (ΔG° ∼ −40 meV for bovine CcO versus −0.1 meV for Rhodobacter sphaeroides CcO). In addition, the reorganizational energy (λ) for ET between heme a and heme a3 is much larger for the bacterial enzyme (1.2 eV vs. 0.76 eV), which should give rise to a smaller rate constant. It appears that the stronger electronic coupling compensates for the larger reorganizational energy and lower driving force in the bacterial enzyme.

In the case of Cbo, the rate constant for ET between heme b and heme o3 is also nearly identical to the analogous heme a3 to heme a ET rate constant despite a larger driving force (ΔG° ∼ −40 meV for bovine CcO versus −71 meV for Cbo).13 In this study we have determined the Marcus parameters for intramolecular ET between heme b and heme o3 in the CO-mixed valence Cbo derivative. Based on this study, the ET Marcus parameters for Cbo (λ = 1.4 ± 0.2, HAB = (2 ± 1) × 10−3 eV, and 9 ± 1 Å) are very similar to the bacterial CcO parameters. It is suggested that structural distortions at the CuB site as well as heme orientation/ET tunneling pathways may play a role in regulating heme-heme ET within the bacterial enzymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cytochrome bo3 was purified from Escherichia coli strain GO105/pJRHISA (Au and Gennis, 1987). A histidine tag on subunit II of the enzyme extends it by seven amino acids, which allows purification in one step. The enzyme is stored as a stock solution (∼150 μM) in 100-mM HEPES buffer containing 0.1% lauryl maltoside. The samples for temperature-dependent transient absorption (TA) were prepared by diluting the cytochrome bo3 stock solution to ∼20 μM in 50-mM HEPES buffer containing 0.1% maltoside (pH ∼ 7.5).

The samples were placed in a 1-cm path length quartz cuvette and sealed with a septum cap. The sample was de-aerated with Ar for ∼5 min, followed by an additional purge of CO for ∼10 min to generate the mixed-valence form of cytochrome bo3. All steady-state absorption spectra were obtained using a Milton Roy Spectronic 300 diode array UV-Vis spectrometer (Ivyland, PA).

A detailed description of the instrumentation used for temperature-dependent TA spectroscopy has been given previously (Larsen et al., 1994). In brief, the arc of a 150-W Xe arc lamp is passed through the sample housed in a constant temperature block regulated by a circulating water bath. The emerging light is then focused onto the entrance slit of a Spex 1680B 1/4M double monochromator and detected using a Hamamatsu R928 PMT coupled to a 500-MHz preamplifier/amplifier system of our own design. The generated signal is then digitized using a Tecktronix RTD710A 200-MHz transient digitizer coupled to an IBM-based PC. A pulse from a frequency doubled Nd:YAG laser (Continuum SureLite I, 532 nm, 7-ns pulse width, 3 mJ/pulse) passing nearly collinear with the probe spot initiates the photochemistry. The temperature was varied between 10 and 35°C in increments of ∼5°C. The data was fit to a one-exponential decay scheme with KinetAsyst 2 software (HiTech Inc., Salsbury, England). All transient absorption traces were the average for 25–50 laser pulses (10 Hz).

RESULTS

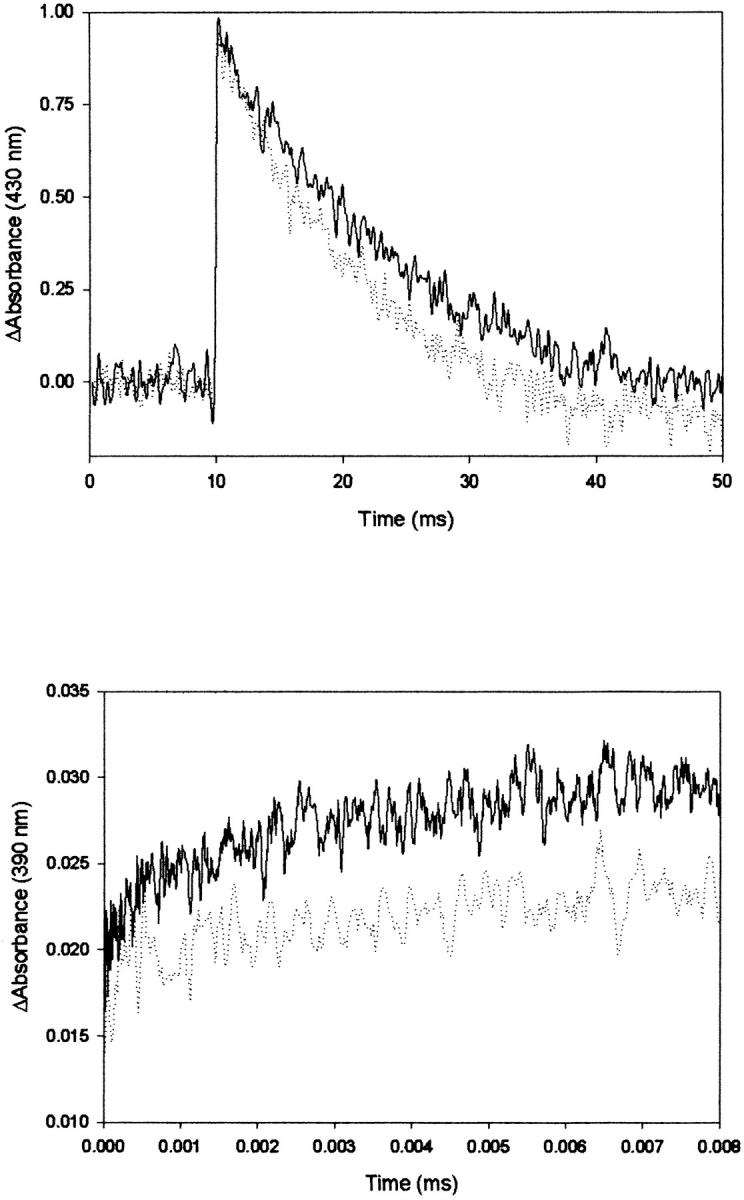

Fig. 2 displays transient absorption traces subsequent to CO photolysis monitored at 430 nm (top panel, maximum of the five-coordinate heme o3) and 390 nm (bottom panel, intramolecular ET) at both 10°C (solid traces) and 35°C (dashed traces). The data obtained at 430 nm could be fit to a single exponential decay with a rate constant of (87 ± 0.4) s−1 at 25°C, consistent with CO rebinding to the heme o3 site (Morgan et al., 1993; Brown et al., 1994). The corresponding data obtained at 390 nm shows a rapid unresolved increase in absorption due to the formation of a five-coordinate heme o3 followed by an additional monophasic absorption increase that has been previously attributed to intramolecular ET between heme o3 and heme b (Brown et al., 1994). The rate constant for this phase is found to be (2.2 ± 0.2) × 105 s−1 at 25°C, consistent with previous studies (Morgan et al., 1993; Brown et al., 1994). The observed rate constant can be written as:

|

(1) |

where kf and kb refer to the forward and back rate constants. In addition, Adelroth et al. (1995) determined the kf using:

|

(2) |

where ΔA and Δɛ are the absorbance and extinction coefficient for the ET at the observation wavelength (390 nm for Cbo, 445 nm for CcO) and CMV is the concentration of the mixed-valence enzyme. Analysis of the data for Cbo reveals a value for kf at 25°C of 1.1 × 105 s−1.

FIGURE 2.

Transient absorption data for the photolysis of the CO-mixed valence derivative of Cbo3. (Top) Traces obtained at 430 nm on a 50-ms timescale; solid line, 10°C; dashed line, 35°C. (Bottom) Traces obtained at 390 nm on a 25-μs timescale; solid line, 10°C; dashed line, 35°C. Sample concentration is ∼20 μM. Traces are the average of 25 laser pulses.

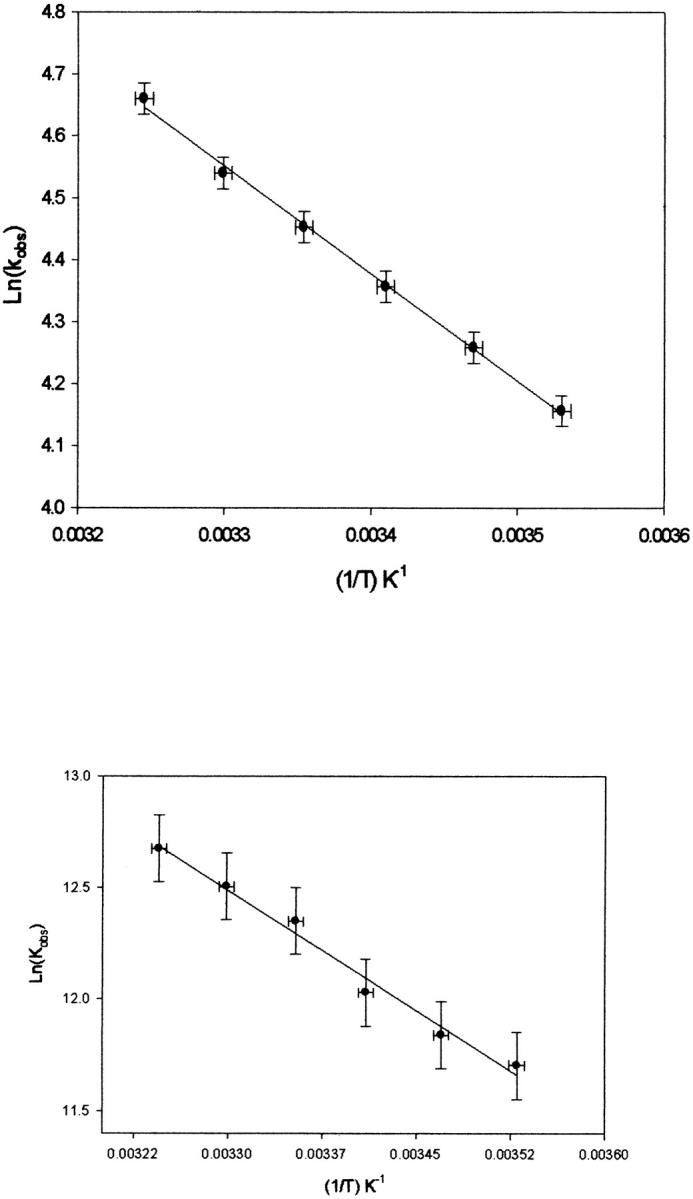

Arrhenius plots describing the temperature dependence of the ET rate constant (determined from fitting the data obtained at 390 nm as a function of temperature) and CO recombination are shown in Fig. 3. The Arrhenius plots give Ea of 3.5 ± 0.4 kcal/mol and 6.7 ± 0.4 kcal/mol for CO recombination and electron transfer, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Plot of Ln(kobs) versus (1/T) for the decay at 430 nm (top) and rise at 390 nm (bottom) subsequent to photolysis.

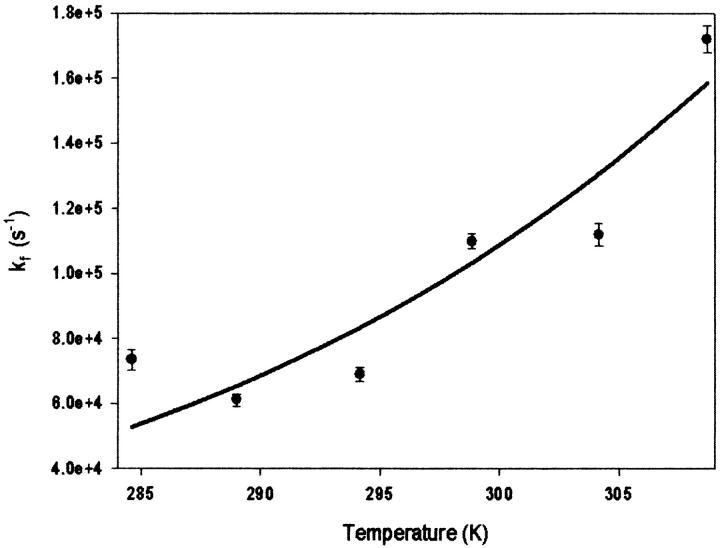

The rate constants for ET (kf) were also plotted versus temperature to obtain various Marcus parameters (Fig. 4). The temperature dependence of the rate constant was fitted to two different expressions of the Marcus equation:

|

(3) |

(where HAB is the electronic coupling factor, λ is the overall reorganizational energy, kB is Boltzman's constant, ΔG° is the reaction free energy, and T is temperature) and:

|

(4) |

(where β = 1.0 Å−1 is an empirically determined distance dependence parameter, ro is the van der Waals contact distance and r is the actual distance between redox centers, and k0 represents the optimal rate constant in the absence of activation barriers and at van der Waals contact distance) (Barbara et al., 1996; Marcus and Sutin, 1985). Fitting the data in Fig. 3 to Eq. 3 yielded λ of 1.4 ± 0.2 eV and Hab = 2.2 × 10−3 eV using a ΔG° of −71 meV (obtained using Keq = kf/kb for the heme b/heme o3 ET reaction). Subsequent fitting of the same data to Eq. 4 (plot not shown) also gave a λ of 1.3 ± 0.1 eV and a distance of 9 ± 1 Å between heme b and heme o3. These values, and the values previously determined for bovine heart CcO and CcO from Rhodobacter sphaeroides are summarized in Table 1.

FIGURE 4.

Plot of kf versus temperature for the decay at 390 nm subsequent to photolysis fit to Eq. 3 (see text for details).

TABLE 1.

Summary of thermodynamic parameters for intramolecular electron transfer in heme/copper oxidases

| ΔG° (meV) | Hab (eV) | λ (eV) | d (Å) | ket (s−1) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine a3 → a | −40 | 9.9 × 10−5 | 0.76 | 13.2 | 2 × 105 | 10,11 |

| Rb. sphaeroidesa3 → a | −0.1 | 9 × 10−4 | 1.2 | 9 | 1.2 × 105 | 11,12 |

| E. colio3 → b | −71 | 2.1 × 10−3 | 1.4 | 9 | 1.1 × 105 | This work |

The analysis described above is based upon the assumption that the value of ΔG° does not vary over the temperature range of the kinetic measurements. This implies that the reduction potentials of cytochrome b and cytochrome o3 do not vary with temperature. From the values of kf and kb determined above the equilibrium constant for electron exchange can be determined (i.e., Keq = kf/kr) and this leads directly to the calculation of ΔG° (i.e., ΔG° = −RTLnK). The average value of ΔG° is found to be −71 meV and this value does not change significantly over the temperature range of our experiments. Previous potentiometric studies of cytochrome bo3 demonstrate very little change in the reduction potentials of the two cytochromes between 15 K and 293 K consistent with the observations presented here (Bolgiano et al., 1991; Salerno et al., 1990). It should be pointed out here that the reduction potentials of heme o3 and heme b have yet to be clearly established. In the fully oxidized enzyme the heme b reduction potential has been reported to be in the 50-mV range whereas the heme o3 potential has been assigned a reduction potential between 220 and 250 mV (Bolgiano et al., 1991; Salerno et al., 1990). In a previous study of intramolecular ET in the mixed valence Cbo the reduction potential of the heme b/heme o3 couple was estimated to be between 15 and 25 mV based upon the [Feb2+Feo33+]/[Feb3+Feo32+] equilibrium (Morgan et al., 1993). This suggests some degree of interaction between the metal sites within the enzyme. Although the reduction potential for the heme b/heme o3 determined here is higher than that previously reported for the mixed valence enzyme it is still considerably lower than that estimated using the reduction potentials of the heme b and heme o3 centers within the fully oxidized enzyme consistent with heme-heme redox interactions.

DISCUSSION

Photolysis of the CO-mixed valence forms of bovine heart CcO, Rb. sphaeroides CcO, and E. coli Cbo results in rapid intramolecular electron transfer between the five-coordinate heme a3 (CcO)/heme o3 (Cbo) and the six-coordinate heme a (CcO)/heme b (Cbo) with rate constants on the order of 2 × 105 s−1 (Morgan et al., 1993; Brown et al., 1994). In the case of the CcOs, further electron redistribution occurs between the low-spin heme a and the low potential CuA center with rate constants on the order of 6 × 104 s−1. It is noteworthy that electron transfer between the two hemes occurs with roughly the same rate constants despite a significant difference in the reaction free energies (see Table 1). Previous temperature dependent studies of heme a3/heme a electron transfer in both bovine heart and Rb. sphaeroides CcO suggest that the similarity in rate constants is due to a balance between the heme/heme distance (13.2 Å for bovine heart versus 9 Å for Rb. sphaeroides), the overall reorganizational energy (λ = 0.76 eV for bovine CcO and 1.2 eV for Rb. sphaeroides), and the electronic coupling between the hemes (Hab = 9.9 × 10−5 eV for bovine heart and 9 × 10−4 eV for Rb. sphaeroides) (Adelroth et al., 1995; Brzezinski, 1996). Thus, it appears that the higher reorganizational energy and small driving force associated with heme a3/heme a electron transfer in Rb. sphaeroides are offset by a shorter effective distance and stronger electronic coupling. In the case of Cbo electron transfer between heme o3/heme b in E. coli Cbo exhibits a heme/heme distance and electronic coupling factor similar to Rb. sphaeroides but with a higher driving force and larger reorganizational energy.

In general, the overall reorganizational energy (λ) associated with electron transfer can be written as the sum of an inner-sphere component, λis, which involves changes in bond length associated with a change in oxidation state of the donor/acceptor and an outer sphere component, λos, which is the response of the solvent to the change in charge distribution on the redox centers (Barbara et al., 1996; Marcus and Sutin, 1985). In the case of heme a3 to heme a electron transfer the total reorganizational energy can be written as:

|

(5) |

where λisa3 is the inner sphere reorganization associated with heme a3, λisa is the reorganizational component associated with heme a, λCuB is the inner sphere reorganization for CuB, and λos is the outer sphere reorganizational energy attributed to the protein response to the change in the redox states of the two hemes. A recent voltametric study of six-coordinate low-spin hemes suggests that λis for the Fe3+ to Fe2+ transition is on the order of 0.4 eV (Blankman et al., 2000). Thus the value of λisa in bovine heart CcO can also be estimated to be 0.4 eV. Because the overall value of λ for the heme a3 to heme a electron transfer in bovine heart CcO is 0.76 eV and λisa is expected to be on the order of 0.4 eV, then λisa3 + λCuB + λos would be roughly 0.36 eV. It is also reasonable to suggest that λos will also be small because the protein should have a relatively low dielectric constant giving λisa3 + λCuB a value of 0.36 eV.

In the case of the bacterial enzymes the overall value of λ is found to be roughly 1.2–1.4 eV. It is unlikely that the values of λisa3/λiso3 and λisa/λiso for heme a3/heme o3 to heme a/heme o electron transfer would be significantly different in the bacterial enzymes from those of the bovine heart CcO. Adelroth et al. (1995) suggested that the large value of λ associated with heme a3/heme a electron transfer in Rb. sphaeroides CcO, relative to bovine heart CcO, could be due to solvation changes within the heme a3/CuB binuclear center subsequent to electron transfer. Interestingly the value of λ for electron transfer between heme o3 and heme b is only slightly larger than that observed for heme a3 to heme a electron transfer in the Rb. sphaeroides CcO. Recent Cu x-ray absorption studies of Cbo have revealed significant differences in the structure of the CuB center upon conversion from Cu(II) to Cu(I) (Ralle et al., 1999; Osborne et al., 1999). The data show that CuB(II) is four coordinate consistent with three histidine ligands and one hydroxyl ligand (or possibly water). In addition, the Cu-N bond lengths are all nearly equivalent (1.95 Å) with the Cu(II)-O bond distance being 2.5 Å. Upon reduction of the CuB site the Cu copper coordination changes from four coordinate to three coordinate with the reduction in coordination resulting from the loss of a histidine ligand. In contrast, the x-ray structure of the reduced form of bovine heart CcO (2.35 Å resolution) does not show any changes in the vicinity of CuB upon reduction (Yoshikawa et al., 1998). A recent high-pressure study of heme a3 to heme a electron transfer in CO-mixed valence bovine heart CcO also revealed a rather large activation volume but this was attributed to structural changes at the heme a3 upon change in redox state (Larsen, 1999). As mentioned above, it is likely that structural changes associated with changes in redox state of heme a3/o3 are likely to be species independent. Thus, it is suggested that the additional 0.4 eV of reorganizational energy associated with heme o3/heme b electron transfer in E. coli and heme a3/heme a electron transfer in Rb. sphaeroides is associated with ligand loss at the CuB center upon oxidation of CuB (i.e., changes in λCuB). This further suggests that electron equilibration between heme o3 and CuB is established on the same timescale as the electron transfer between heme b and heme o3.

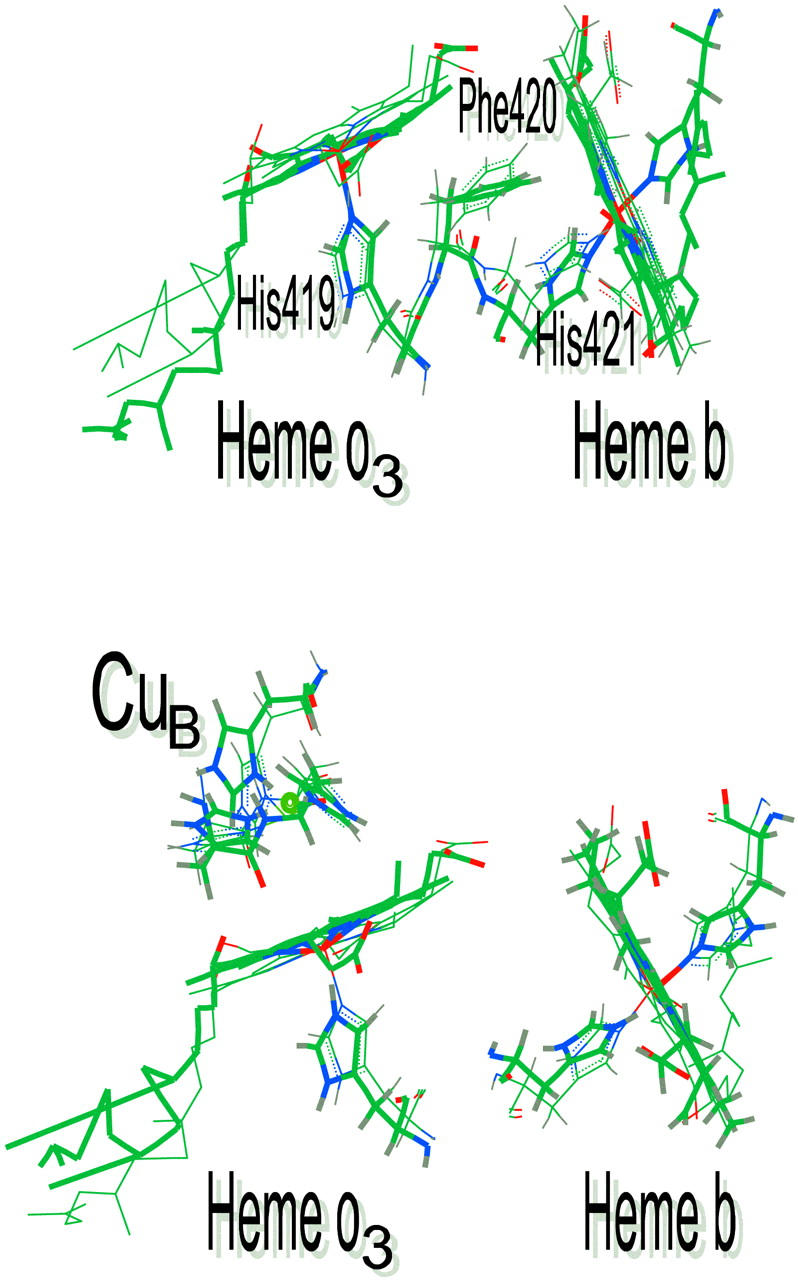

The temperature dependence of the rates of heme a3/o3 to heme a/b electron transfer also reveals significant differences in electronic coupling between the hemes of CcO and Cbo. The difference in electronic coupling may be due to differences in donor/acceptor distance and/or differences in donor/acceptor orientation. Previous theoretical studies of bovine heart CcO suggest two electron tunneling pathways between heme a and heme a3 that are coupled to each other (Fig. 5) (Regan et al., 1998; Gamelin et al., 1998; Medvedev et al., 2000). The first is a direct jump between a methyl group on heme a to the analogous methyl group on heme a3 with a distance of ∼3.5 Å. The alternative pathway involves the imidazole ring of His-378 and Phe-377 and the heme a3 porphyrin ring. The electronic coupling factor is calculated to be 5 × 10−5 eV which is close to the experimental value for the bovine enzyme. The fact the residues involved in the His-Phe pathway are conserved in both E. coli cytochrome bo3 and Rb. sphaeroides cytochrome aa3 suggests that the tunneling pathways are likely to be the same as those in the bovine enzyme. Thus, the larger value of the electronic coupling observed for both bacterial enzymes suggests different orbital coupling between the residues involved in the coupling. Examination of the recent x-ray structure of fully oxidized Cbo does, in fact, show clear differences in the orientations of the amino acid side chains involved in the proposed tunneling pathway (Fig. 5) (Abramson et al., 2000). Specifically, the phenyl rings of the Phe-377 (bovine)/Phe-369 (E. coli) are at an angle of roughly 30° relative to each other suggesting that the effective tunneling distance may not be the same in both enzymes.

FIGURE 5.

Overlay of proposed electron tunneling pathways for electron transfer between the heme groups of cytochrome c oxidase and cytochrome bo3.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Science Foundation (RWL, MCB9904713), the Department of Energy (RBG, DE-FG02-87ER13716), and the American Heart Association (RWL, HIGS-11-97 and AHA0051594Z)

References

- Abramson, J., S. Riistama, G. Larsson, A. Jasaitis, M. Svensson-Ek, L. Laakkonen, A. Puustinen, S. Iwata, and M. Wikstrom. 2000. The structure of the ubiquinol oxidase from Escherichia coli and its ubiquinone binding site. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:910–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelroth, P., P. Brzezinski, and B. G. Malmstrom. 1995. Internal electron transfer in cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 34:2844–2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anraku, Y., and R. B. Gennis. 1987. The aerobic respiratory chain of Escherichia coli. TIBS. 12:262–266. [Google Scholar]

- Au, D. C., and R. B. Gennis. 1987. Cloning of the cyo locus encoding the cytochrome o terminal oxidase complex of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169:3237–3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara, P. F., T. J. Meyer, and M. A. Ratner. 1996. Contemporary issues in electron transfer research. J. Phys. Chem. 100:13148–13168. [Google Scholar]

- Blankman, J. I., N. Shahzad, B. Dangi, C. J. Miller, and R. D. Guiles. 2000. Voltammetric probes of cytochrome electroreactivity: the effect of the protein matrix on outer-sphere reorganization energy and electronic coupling probed through comparisons with the behavior of porphyrin complexes. Biochemistry. 39:14799–14805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolgiano, B., I. Salmon, W. J. Ingledew, and R. K. Poole. 1991. Redox analysis of the cytochrome o-type quinol oxidase complex of escherichia coli reveals three redox components. Biochem. J. 274:723–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S., J. N. Rumbley, A. J. Moody, J. W. Thomas, R. B. Gennis, and P. R. Rich. 1994. Flash photolysis of the carbon monoxide coumpounds of wild-type and mutant variants of cytochrome bo from Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1183:521–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski, P. 1996. Internal electron transfer in cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 35:5611–5615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einarsdottir, O., T. D. Dawes, and K. E. Georgiadis. 1992. New transients in the electron transfer dynamics of photolyzed mixed valence co-cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:6934–6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamelin, D. R., D. W. Randall, M. T. Hay, R. P. Houser, T. C. Mulder, G. W. Canters, S. de Vries, W. B. Tolman, Y. Lu, and E. I. Solomon. 1998. Spectroscopy of mixed-valence cua-type centers: ligand-field control of ground state properties related to electron transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120:5246. [Google Scholar]

- Gennis, R. B. 1998. How does cytochrome oxidase pump protons? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:12747–12749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, R. W. 1999. Activation profiles for intramolecular electron transfer in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. FEBS Lett. 462:75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, R. W., E. W. Findsen, and R. E. Nalliah. 1994. Ligand photolysis and recombination of fe(II) protoporphyrin IX complexes in dimethylsulphoxide. Inorg. Chem. 234:101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, M. A., and N. Sutin. 1985. Electron transfer in chemistry and biology. Biophys. Biochim. Acta. 811:265–3022. [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev, D. M., I. Daizadeh, and A. A. Stuchebrukhov. 2000. Electron transfer tunneling pathways in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122:6571–6582. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J. E., M. I. Verkhovsky, A. Puustinen, and M. Wikstrom. 1993. Intramolecular electron transfer in cytochrome o of Escherichia coli: events following the photolysis of fully and partially reduced co-bound forms of the bo3 and oo3 enzymes. Biochemistry. 32:11413–11418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J. E., P. M. Li, D. Jang, M. A. El-Sayed, and S. I. Chan. 1989. Electron transfer between cytochome a and copper a in cytochrome c oxidase: a perturbed equilibrium study. Biochemistry. 28:6975–6983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser, S. M., M. H. B. Stowell, and S. I. Chan. 1995. Cytochrome c Oxidase: Chemistry of a Molecular Machine Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology, Vol. 71. A. Meister, editor. Wiley and Sons, New York. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ogunjimi, E. O., C. Pokalsky, L. Shroyer, and L. Prochaska. 2000. Evidence for a conformational change in subunit III of bovine heart mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase. J. Bioenerg. Biomem. 32:617–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, J. P., N. J. Cosper, C. M. V. Stalhandske, R. A. Scott, J. O. Alben, and R. B. Gennis. 1999. Cu XAS shows a change in the ligation of Cub upon reduction of cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 38:4526–4532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puustinen, A., M. Finel, M. Virkki, and M. Wikstrom. 1989. Cytochrome o (bo) is a proton pump in Paracoccus denitrificans and Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 249:163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralle, M., M. L. Verkhovskaya, J. E. Morgan, M. I. Verkhovsky, M. Wikstrom, and N. J. Blackburn. 1999. Coordination of CuB in reduced and co-liganded states of cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli. Is chloride ion a cofactor? Biochemistry. 38:7185–7194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan, J. J., B. E. Ramirez, J. R. Winkler, H. B. Gray, and B. J. Malmstrom. 1998. Pathways for electron tunneling in cytochrome c oxidase. J. Bioenerg. Biomem. 30:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno, J. C., B. Bolgiano, R. K. Poole, R. B. Gennis, and W. J. Ingledew. 1990. Heme-copper and heme-heme interactions in the cytochrome bo-containing quinol oxidase of Escherechia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 265:4364–4368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikstrom, M., K. Krab, and M. Saraste. 1981. Cytochrome Oxidase. A Synthesis. Academic Press, London.

- Yoshikawa, S., K. Shinzawa-Itoh, R. Nakashima, R. Yaono, E. Yamashita, N. Inoue, M. Yao, M. J. Fei, C. P. Libeu, T. Mizushima, H. Yamaguchi, T. Tomizaki, and T. Tsukihara. 1998. Redox coupled crystal structural changes in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Science. 280:1723–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]