Abstract

The thermodynamics of cation permeation through the KcsA K+ channel selectivity filter is studied from the perspective of a physically transparent semimicroscopic model using Monte Carlo free energy integration. The computational approach chosen permits dissection of the separate contributions to ionic stabilization arising from different parts of the channel (selectivity filter carbonyls, single-file water, cavity water, reaction field of bulk water, inner helices, ionizable residues). All features play important roles; their relative significance varies with the ion's position in the filter. The cavity appears to act as an electrostatic buffer, shielding filter ions from structural changes in the inner pore. The model exhibits K+ vs. Na+ selectivity, and roughly isoenergetic profiles for K+ and Rb+, and discriminates against Cs+, all in agreement with experimental data. It also indicates that Ba2+ and Na+ compete effectively with permeant ions at a site near the boundary between the filter and the cavity, in the vicinity of the barium blocker site.

INTRODUCTION

Potassium channels form a wide and diverse class of ion channels. Their fundamental role is to “stabilize” the membrane potential, bringing it closer to the potassium equilibrium potential and farther from the firing threshold. In addition to this electrical role, K channels also help in the transport of ions and water in epithelial and glial cells, and probably have other functions as well. Differences among K-channels relate more to their gating characteristics than to ionic selectivity. All exhibit a permeation selectivity sequence Tl+ > K+ > Rb+ > NH4+, and are usually blocked by Cs+ (Bezanilla and Armstrong, 1972; Yellen, 1984a,b; Hodgkin and Keynes, 1955). Generally Na+ and Li+ permeability is too low to be measured. Potassium is typically many thousands times more permeable than Na+, a feature essential to channel function.

Molecular cloning and mutagenesis experiments have demonstrated that all K+ channels have essentially the same pore constitution (MacKinnon and Yellen, 1990; Yellen et al., 1991; Hartmann et al., 1991) with a common sequence (TVGYG), the “potassium signature.” Mutating any of these residues disrupts the channel's selectivity for K+ against Na+.

The x-ray structure of the KcsA K+ channel, a bacterial channel from Streptomyces lividans (Doyle et al., 1998), validated inferences drawn from decades of electrophysiological measurements, confirming that the channel was a multi-ion pore and that, on the extracellular side, there was a narrow selectivity filter formed by the highly conserved signature sequence. In passing to the cytoplasmic side, there was a wider water-filled cavity followed by a hydrophobic inner pore. The original x-ray structure highlighted three coordination positions for the ion(s), two in the selectivity filter and a third at the center of the cavity. More recent work (Zhou et al., 2001) clearly shows additional coordination sites, both at the filter-cavity boundary and at the extracellular mouth. Filter structure appears to be fairly rigid; it is surrounded by two sets of helices (inner and outer). The carboxy termini of the inner ones point toward the center of the water-filled cavity, contributing to ion stabilization (Doyle et al., 1998; Roux and MacKinnon, 1999). The cavity itself is finely tuned to specifically accommodate K+, whose hydration structure there is so optimal and stable that it is visible crystallographically (Zhou et al., 2001).

Publication of this structure has led to an explosion of theoretical analysis of pore behavior and properties: electrostatic studies of the cavity ion (Roux and MacKinnon, 1999); full-scale simulations focusing on permeation (Bernèche and Roux, 2000, 2001; Åqvist and Luzhkov, 2000; Shrivastava and Sansom, 2000), on the basis for selectivity (Luzhkov and Åqvist, 2001; Biggin et al., 2001), and on modeling ion currents (Burykin et al., 2002); truncated permeation models, explicitly including only selectivity filter residues (Allen et al., 1999a,b); mesoscopic conductance models based on Brownian dynamics (BD) (Chung et al., 1999; 2002a).

In general, the investigations are in agreement with one another and consistent with experiment. The molecular dynamics (MD) studies by and large indicate increased rigidity of the protein in the selectivity filter region, with the ions preferentially coordinated at the crystallographic sites. Relative permeation energetics, where a fixed number of ions translocate among pore occupancy states, yield profiles that correlate reasonably well with experiment. However, none of the MD studies seems robust enough to provide reliable permeation free energy profiles relative to bulk water. The molecular level conductance computations (Burykin et al., 2002), although qualitatively of great interest, do not seem to imply the three-ion occupancies suggested both electrophysiologically and crystallographically (Hodgkin and Keynes, 1955; Hille and Schwartz, 1978; Doyle et al., 1998; Morais-Cabral et al., 2001). The BD studies, by judicious adjustment of the pore's effective dielectric constant, are able to reproduce many aspects of observed conductance behavior.

Free-energy computations of channel proteins are generally very computer intensive. In addition to the pore former, here comprised of ∼2800 atoms, one must model the surroundings, lipid and bulk electrolyte, each a region of very different dielectric properties. A completely rigorous treatment, designed to determine ionic permeation free energies in the channel's selectivity filter, would require: A), an all-atom approach, including the complete protein, channel water, and substantial regions of the lipid membrane and of intracellular and extracellular water; B), a force field that properly accounts for polarization; C), accounting for all intermoiety interactions, including the long-range electrostatics; D), a statistically meaningful amount of data.

To date, no theoretical study totally addresses all these issues. To cope with these difficulties, various methods are used. These techniques usually ignore some aspects of the system, treat others in approximate, computationally cheaper ways, and focus their efforts on the details considered most important.

For free-energy determinations, radical approximations are applied. In one recent study (Åqvist & Luzhkov, 2000), all nonbonded interactions except those involving the ions are treated approximately, using a third order multipole expansion method (Lee & Warshel, 1992). Alternatively, long-range electrostatics is dealt with using Ewald summations (Bernèche and Roux, 2000, 2001) or reaction field methods (Åqvist and Luzhkov, 2000; Luzhkov and Åqvist, 2001).

Conductance studies require monitoring the system for microseconds, totally out of the question for MD simulations. However, an MD generated potential of mean force can be directly used as input for BD analysis (Bernèche and Roux, unpublished results). Severe approximation, done using mesoscopic modeling via BD, is another possibility (Chung et al., 1999, 2002a,b; Allen et al., 1999a). Only a few features are explicitly included. The “solvents” (membrane, bulk water and intrapore water) are treated as dielectric continua. The “dielectric constant” of the intrapore water is unknown, and results depend significantly on its value. Truncating the problem and employing continua permits tracking ion passage through the model channel. However molecular detail is lost. A yet different alternative, a microscopic-mesoscopic hybrid, treats the membrane and distant bulk water as dielectric continua and describes the ion(s), nearby bulk water and the protein with restricted MD, uses reaction field boundary conditions, and develops ionic free-energy profiles; these are then coupled with BD to simulate ionic trajectories (Burykin et al., 2002) yielding conductances that are qualitatively in accord with observation.

The complications introduced in modeling domains with significantly different dielectric properties (outer and inner bulk water, lipid, protein) make simulation of membrane proteins especially challenging. The various charged species (ions and ionizable groups) strongly polarize their surroundings in the low ɛ regions, behavior that is a fundamental aspect of channel biophysics, and which consequently can significantly influence biological functioning. A central concept in membrane biophysics views the membrane as nature's tool for “compartmentalization of life's essential ingredients” (Hille et al., 1999), making the question of dielectric phase boundaries especially important. Consistent with this description of the physiological ensemble, our computational model accounts for dielectric discontinuities with great care, using an approach that treats long-range electrostatics exactly, modeling explicitly and exactly those degrees of freedom considered most critical for permeation and relegating unavoidable approximations to parts of the system considered quantitatively less significant for permeation. The rest of the system is approximated by charges embedded in dielectric continua. The peculiar advantages of this approach are threefold: reaction field effects due to neighboring phases with different dielectric constants are described simply and exactly; the computational load imposed by periodic boundaries is avoided; the rapidity of the calculations allows one to dissect the various contributions to the stabilization of permeant ions and assess their joint and several effects on selectivity. While highly simplified, it circumvents some of the computational difficulties outlined above. The development of a reasonable, relatively simple modeling approach is of special importance for theoretical study of the much larger channel proteins for which structures are now available: a ClC chloride channel (Dutzler et al., 2002), two aquaporins (Murata et al., 2000; Sui et al., 2002), and an aquaglyceroporin (Fu et al., 2000).

Our approach is a microscopic-mesoscopic hybrid, like those of Chung et al. (1999, 2002a) and Burykin et al. (2002); however, it differs from both. Like the former, only a few microscopic features are included, but our channel waters are explicit and the carbonyls are mobile, not static. Like the latter, permeation involves removing an ion from the high ɛ aqueous medium and transferring it to the selectivity filter, embedded in a low ɛ domain. But our ɛ is not a mean field parameter, adjusted to account for charge-induced protein reorganization. Instead, structural polarization arises from explicit reorientation of the protein; ɛ, chosen at the outset, accounts for electronic influences alone.

We present a simplified and physically transparent, but generally realistic and computationally tractable model of the K+ channel selectivity domain, one that may be readily scaled up to higher accuracy and performance. It is targeted at estimating how individual moieties present in the protein affect the free energy of permeation, for ions positioned at or near the coordination sites of the selectivity filter. In subsequent sections we first describe the computational model, our approach to implementing it and estimating ion permeation energetics. We then exploit this treatment, first considering the influence that the various structural features, both individually and collectively, have on ion and water behavior in the filter, then focusing on the role of cavity water, and finally addressing questions regarding permeation. Because of its computational simplicity, we can compare, in a readily interpretable fashion, the way that the different alkali cations and barium interact with parts of the selectivity filter. It is easy to extend the approach, implementing additional features, and designing more realistic approximations, without the heroic computational efforts needed in MD studies.

THE COMPUTATIONAL MODEL

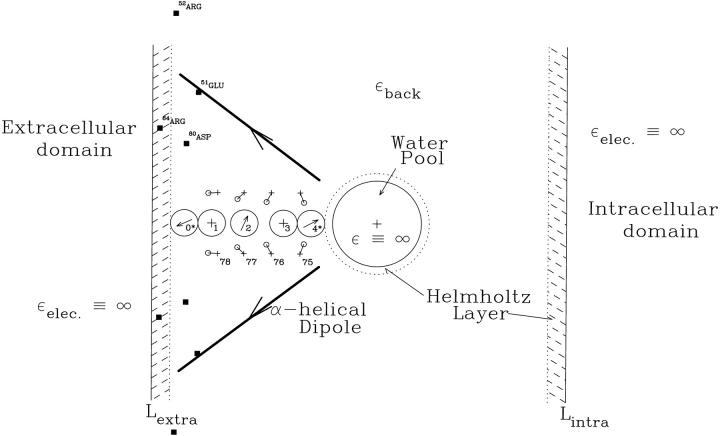

The computational idealization is illustrated in Fig. 1. All five sites illustrated have rough physiological parallels. We follow MacKinnon's numbering convention (Morais-Cabral et al., 2001). Sites 1-3 correspond to the carbonyl binding pockets. Since the Thr75 residues were not explicitly incorporated (see below), site 4*, located at the cavity-filter boundary, can only represent a generalized binding region. Site 0* approximates the axial binding site, just beyond the binding pockets (Zhou et al., 2001; Miller, 2001; Bernèche and Roux, 2001). The asterisks are used to indicate that these two sites, due to the truncated nature of the model, are only general analogs of the crystallographic locations. We conzsider possible ionic occupancy of all sites. In the spirit of the semimicroscopic (SMC) approach the model includes only those structural features deemed most critical for ionic coordination by the filter (Dorman et al., 1996, 1999; Garofoli et al., 2002). A limited number of these are mobile and reorientable: the ion(s), the single file waters in the selectivity filter, and the carbonyl oxygens from residues 75-78, which form the binding pockets. For computational simplicity the remainder are viewed as fixed background charges: the cavity ion, the carbonyl carbons from residues 75-78, the oriented α-helices and selected charged residues. In addition to the crystallographic water, additional single-file waters were added to complete the ions' solvation shells, as suggested both by inspection of the original crystal structure, by MD simulation and recently confirmed experimentally (Zhou et al., 2001). Thus, in all computations each of the five coordinating positions contained either an ion or water. The water-filled cavity and both bulk water domains are modeled as dielectric continua with ɛ ≡ ∞, which give rise to a reaction field that interacts with the model's explicit electrical features. Water, with its ɛ of 80, is nearly an ideal conductor (Partenskii et al., 1991, 1994, 1998; Partenskii and Jordan, 1992a,b); the errors associated with this approximation are ≤2.5% of the total reaction field contribution (Dorman and Jordan, 2003), typically ∼1 kJ mol−1.

FIGURE 1.

Semimicroscopic model geometry for the KcsA selectivity filter. This planar projection includes solvating CO groups (residues 75–78 of each tetramer strand), single file ions and waters, peptide dipoles, the Asp80 and Glu51 carboxylates, the Arg64 and Arg52 guanidiniums, the aqueous cavity and its included ion. Bulk electrolyte and the cavity are treated as dielectric continua, ɛ ≡ ∞. The Helmholtz layer (accounting for water immobilized by interaction with polar surfaces) separating the explicit sources in the filter from extracellular bulk water has a width of 2 Å; that between the filter and the midchannel water pool is 1.5 Å. The pool radius is 5.0 Å and it accommodates ∼20 waters. The carbonyl binding pockets at sites 1 and 3 are ∼18.5 Å and ∼11.0 Å from the cavity center. Site numbering follows the convention of Morais-Cabral et al. (2001). Modified from Garofoli et al. (2002), with permission.

The membrane and those parts of the channel not explicitly represented are modeled as a low dielectric background continuum, ɛback ∼ 2; ɛback should not be identified with the lipid ɛ. The channel features that are explicitly modeled account for structural contributions to dielectric shielding (translational and rotational reorientation of waters and peptide moieties), i.e., processes at up to THz frequencies. Ultra-high-frequency electronic contributions to dielectric relaxation are not explicitly treated; it is these that give rise to the background dielectric. This separation has commonality with that of Burykin et al. (2002). However, by not assigning a mean field protein ɛ, we avoid the severe model dependence of “protein dielectric constants” (Partenskii and Jordan, 1992a,b; Warshel and Papazyan, 1998; Schutz and Warshel, 2001). ɛback describes electronic effects; the dielectric influence of protein realignment arises naturally.

Crystallographic coordinates were strand averaged, determining symmetrized rest locations of the various features. The rest orientations of the carbonyl oxygens were determined by energy minimization of an unoccupied channel using InsightII/Discover modeling software (Accelerys) with the consistent-valence force field (CVFF) force field (Dauber-Osguthorpe et al., 1988). Although ions and waters always occupy the real filter, to properly account for energetic effects due to reorientation of the carbonyls by the filter contents it is first necessary to determine a hypothetical “rest” configuration (the unoccupied channel); it differs little from the crystallographic structure. Distances are measured from the center of the aqueous cavity, assigned a physical radius of 5.0 Å, consistent with the structural data of Doyle et al. (1998). Simulations using InsightII/Discover (Accelerys) place ∼20 waters in the cavity, also consistent with this radius.

Of the potentially ionizable residues, the Asp80, Arg64, Glu51, and Arg52 have been included in the model. The other potentially ionizable groups are assumed to form salt bridged pairs (Arg117 and Glu118), to be too far from the filter to significantly affect energetics (Arg89) or to be too deeply embedded in the low ɛ milieu to deprotonate (Glu71). The charge state of the Glu71 is somewhat controversial; two studies indicate it should be uncharged (Bernèche and Roux, 2002; Luzhkov and Åqvist, 2000) although Ranatunga et al. (2001) suggest there are conditions where it may be partially deprotonated, by transferring its proton to the Asp80. The implications of such charge transfers are considered briefly below. There is evidence for ion binding at site 4* (Morais-Cabral et al., 2001), which could involve eightfold coordination if hydroxyls from Thr75 participated in forming the cavity. The role of these hydroxyls is not clear. One MD study suggests all four are involved in binding (Shrivastava and Sansom, 2000); another finds only one of the four participating and that interaction is transient (Bernèche and Roux, 2000). As modeling very mobile groups was not easily done with our computational algorithm and as immobilizing the Thr75 would yield highly unreliable free energies, we eliminated them from the final model. As a result, we cannot distinguish site 4* from electrostatically similar regions somewhat displaced toward the cavity.

Inputs are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The Tyr78 carbonyl carbons (those furthest from the cavity) are numbered 1-4, etc. The rest position of On is given by

|

(1a) |

|

(1b) |

|

(1c) |

dCO is the carbonyl bond length (1.22 Å). Here z[Cn] is the axial distance of the nth carbon from the cavity center, ρ[Cn] its radial distance from the channel axis, θn its polar angle about the channel axis; ψn and φn are the longitudinal and latitudinal angles of the nth oxygen in a coordinate system where the polar axis is the radius vector between Cn and the channel axis. It should be noted that, as observed in the x-ray structure with its structurally compact filter domain, there are a few unavoidable short O-O contacts among the carbonyls. Finally, the left- (extracellular) and right- (intracellular) hand dielectric boundaries are respectively, 26.0 and 20 Å from the pool center. The left-hand boundary includes a Helmholtz layer, extending 2 Å beyond the channel (or membrane) surface (Dorman et al., 1996). The choice of right-hand boundary is highly approximate, but energetically immaterial as it is far removed from the filter.

TABLE 1.

Symmetrized coordinates and effective charges of the carbonyl carbons, α-helical termini and carboxylates and guanidiniums of strand I

| Atom or group | Z/Å | ρ/Å | θ/rad | qeff/eo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonyl C, 1 | −19.2 | 3.45 | 0 | +0.38 |

| Carbonyl C, 5 | −16.3 | 3.45 | 0 | +0.38 |

| Carbonyl C, 9 | −13.5 | 3.45 | 0 | +0.38 |

| Carbonyl C, 13 | −10.3 | 3.45 | 0 | +0.38 |

| α-helix, carboxy terminus | −6.5 | 7.7 | 0 | −0.50 |

| α-helix, amino terminus | −18.1 | 21.3 | 0 | +0.50 |

| Asp80, carboxylate group | −21.2 | 9.7 | π/8 | −0.29 |

| Arg64, guanidinium group | −25.2 | 10.7 | 0 | +1.00 |

| Glu51, carboxylate group | −20.0 | 16.0 | −π/8 | −0.23 |

| Arg52, guanidinium group | −23.5 | 23.7 | 0 | +0.56 |

A cylindrical coordinate system is used: z is the axial distance from the center of the cavity; ρ is the radial distance from the channel axis; θ is the polar angle about the axis. The coordinates for corresponding features of the other three strands are generated by successive 90° rotations. See text for discussion of the choices of the effective charges.

TABLE 2.

Energy minimized orientation angles of carbonyl oxygens (see Eq. 1)

| Oxygen number | ψ/deg | φ/deg |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42 | 111 |

| 2 | 41 | 159 |

| 3 | 40 | 70 |

| 4 | 42 | 24 |

| 5 | 66 | 163 |

| 6 | 65 | 107 |

| 7 | 65 | 17 |

| 8 | 67 | 73 |

| 9 | 98 | 98 |

| 10 | 67 | 129 |

| 11 | 67 | 38 |

| 12 | 68 | 51 |

| 13 | 101 | 146 |

| 14 | 100 | 124 |

| 15 | 100 | 34 |

| 16 | 102 | 56 |

The ψn and φn are longitudinal and latitudinal angles of On in a coordinate system where the polar axis is the radius vector between Cn and the channel axis.

The helix macrodipoles help stabilize ions in the aqueous cavity (Doyle et al., 1998; Roux and MacKinnon, 1999). The dipole moment is determined by summing individual contributions from each NH and CO dipole of the chain. Were the helices ideal, this would correspond to siting equivalent charges at the carboxy and amino termini of the pore helices. However, these extreme residues, although satisfying helix definition requirements (Kabsch and Sander, 1983), are not perfectly aligned. Due to this deformation, the COs of Thr74 (the final residue in each helix) are far closer to the cavity than is consistent with the overall macrodipolar orientation. Consequently we used data from the last three residues (72-74) to determine the effective location of the helices' negative termini, leading to a placement distinct from earlier estimates, themselves rather different (Allen et al., 1999a; Chung et al., 1999). Ion energetics at sites 0*-3 of the filter are fairly insensitive to the positioning of the effective helix negative termini; however, ionic stability at site 4* and in the cavity is choice sensitive.

Ions are modeled as charged hard spheres, using crystallographic radii (Pauling, 1960). An SPC-like model describes the water; because electronic polarization is accounted for by the choice of background dielectric, the model water has its gas phase dipole moment, 1.86 Debye. The hydrogen charge is +0.32955 eo; charges are sited at the equilibrium atomic positions. The water molecule is assigned a hard-core radius of 1.4 Å, consistent with the pair correlation function of ambient water. With these identifications, the hydration free energy of the three smallest halides and of the three larger alkali cations have been computed and found to reproduce the experimental data with a standard deviation of ∼2 kT at 300 K (Dorman and Jordan, 2003). Analogous to the treatment of water, the charge on the CO carbon, +0.38 eo, is chosen to reproduce the group's permanent dipole moment (Pethig, 1979; Lee and Jordan, 1984); the influence of the bond's electronic polarization is then implicitly accommodated in the choice of ɛback. The carbonyl oxygen's hard-core radius is 1.4 Å, essentially the van der Waals radius. Standard charges are chosen for the α-helices' carboxy and amino termini, −0.5 eo and +0.5 eo respectively (Hol et al., 1978).

Determining the proper effective charge state of the charged residues for use in further analysis requires care. The crystal structure indicates that these residues are at the channel-water interface so they are most likely fully charged. Focusing on the Asp80s, the negatively charged groups' electrical interaction with bulk water gives rise to a set of positive image charges, creating a set of effective dipoles, thus greatly reducing their influence on the ions in the filter. In the real system the Asp80s abut a large extracellular mouth; for a fully charged carboxylate ∼1.4 Å from the boundary, the effective dipole moment would be 13.4 Debye. From Fig. 1 it is clear that a portion of this mouth region is incorporated into the Helmholtz layer; the negative charges are 4.8 Å from the boundary, creating an effective dipole of 46.1 Debye, slightly more than three times its actual strength. To correct for this geometric artifact Asp80 charges have been reduced correspondingly. Similar considerations are used in assigning effective charges to Glu51 and Arg52 residues; because Arg64 is close to the image plane, its charge need not be attenuated.

Within the single file, the ion(s) and explicit waters have unrestricted translational and rotational freedom. The carbonyl oxygens can reorient from their rest locations; bending is described by an harmonic potential, Ubend = 1/2kbend (θ − θo)2, with kbend taken to be 6 × 10−20 J, typical of low-energy torsional modes in polypeptides (Fisher et al., 1981). Because the filter geometry is so tightly constrained, results are insensitive to gross changes in kbend.

As already indicated, ions at sites 0* or 4*, being adjacent to continuum regions, are incompletely solvated by explicit waters; quantitative results are correspondingly less reliable. Site 4* energetics are further uncertain because the possibility of transient interaction with Thr75 is ignored and because its energetics are sensitive to the placement of the negative macrodipole termini.

IMAGE CHARGE ANALYSIS – THE REACTION FIELD

For a planar interface, the reaction field due to interaction between a charge embedded in the low ɛ domain (ɛback) and the surrounding high ɛ region (ɛbulk) can be expressed in terms of a series of electrical images of alternating polarity, located in the high ɛ region. For a real charge q at a point (z, ρ, θ), the primary images are located at (2LIntra − z, ρ, θ) and (2LExtra − z, ρ, θ); the charge associated with these images is −q(ɛbulk − ɛback)/(ɛbulk + ɛback). With bulk water as the high ɛ domain, approximating ɛbulk by infinity introduces little error. The complete series of higher order images is generated by repeated reflection at the planes LIntra and LExtra (Jackson, 1962).

The reaction field due to interaction with a spherical cavity is less simple. Considering only interaction with the cavity (ɛcavity), the potential φ(r), at the point r, due to a real charge q located at a point Ro outside the cavity, is

|

(2a) |

where

|

(2b) |

|

(2c) |

ao is the radius of the cavity and χ is the angle between r and Ro (Dorman and Jordan, 2003). In the event that ɛcavity ≫ ɛback, the summation term vanishes and an imagelike description is appropriate. In addition to the image charge q′ at So, there is a compensating charge at the center of the cavity, which is not charged, but dipolar.

The proper choice of ɛcavity is not immediately self-evident; simulations of dipolar correlations in water in small cavities suggest a value as small as 5 (Zhang et al., 1995). However, ɛ is a macroscopic property only rigorously defined for large cavities, where it would have the same ɛ as bulk water and the imagelike description would be appropriate. In constricted surroundings it is known that the effective ɛ differs depending upon the property that is being studied (Partenskii et al., 1994). For simplicity we have assumed that in our model system ɛcavity is large, an approximation that has been justified by comparison with computations in which the cavity is filled with explicit model waters (Garofoli et al., 2002).

Each real charge generates four primary images, two in the bulk domains and a dipolar pair in the cavity. Following the rules just outlined, each of these generates further images with oscillating polarity, so that the total number of images to be cataloged grows rapidly and no closed form expression for the total image energy could be found. However, the dipolar cavity image energies attenuate rapidly; third and higher terms can be ignored. The series of purely planar images oscillates and beyond fourth order the residual image energy can be accurately approximated analytically.

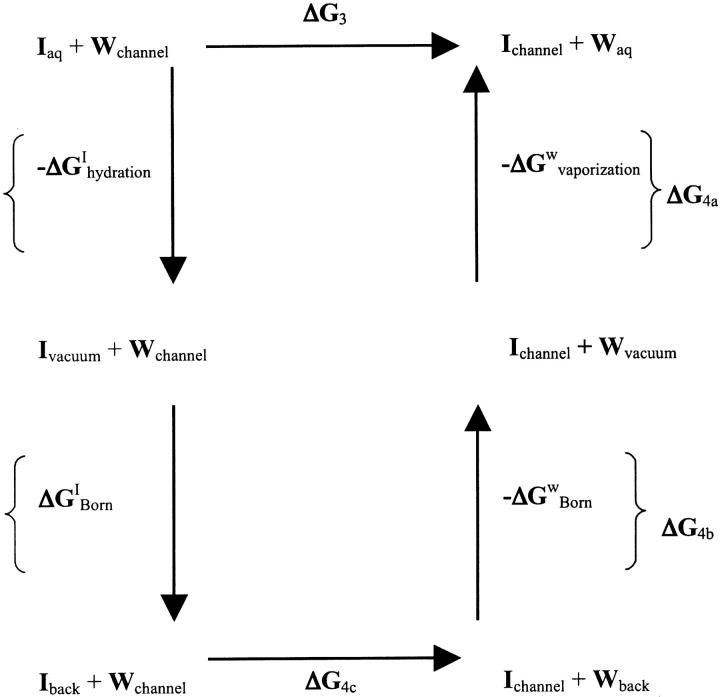

Equivalent thermodynamic cycle

Permeation through the potassium channel is a concerted process. As an ion enters the intracellular side of the selectivity filter from the aqueous cavity, another one departs at the extracellular mouth. Overall permeation energetics can be described as an exchange process, where hydrated ions replace water molecules at particular channel sites. A typical step is

|

(3) |

which, for computational purposes, can be decomposed into subsidiary stages:

|

(4a) |

|

(4b) |

|

(4c) |

Here (aq) indicates the bulk water environment, (background) indicates an infinite homogeneous dielectric with a permittivity reflecting the contribution from electronic polarizability (ɛ ∼ 2), and (channel) indicates the complete model system. The complete cycle is illustrated in Fig. 2.

FIGURE 2.

Equivalent thermodynamic cycle of Eqs. 3 and 4. The steps corresponding to Eqs. 4a, 4b, and 4c are illustrated separately.

The first term in this composite description (Eq. 4a) accounts for ion-water exchange between electrolyte and vacuum. It is determined experimentally as the sum of the ionic dehydration free energy and the aqueous condensation free energy,

|

(5) |

Ionic dehydration free energies cannot be directly measured. Tabulated thermodynamic data define the half-cell potential for the standard hydrogen electrode as 0.000 V. Absolute determination requires a value for the absolute free energy of formation of the hydrated proton. This has been estimated by various methods (Grunwald, 1996; Reiss and Heller, 1985; Randles, 1956; Tissandier et al., 1998), with values between +411 and +465 kJ mol−1. We use the latest finding, +411 kJ mol−1 (Tissandier et al., 1998), which is consistent with recent theoretical studies (Pliego and Riveros, 2000; Tawa et al., 1998).

The second term (Eq. 4b) describes a coupled Born transfer process, in which each charge distribution (ion or water) is embedded in a spherical cavity with ɛ = 1 and transferred from this vacuum to the dielectric background (or vice versa). The associated free energy is readily computed, given a Born cavity radius for both the ion and the water (Beveridge and Schnuelle, 1975; Roux et al., 1990; Hyun and Ichiye, 1997; Hummer et al., 1996). These radii were determined by energy minimizations with an ion at filter sites 1–4*, waters at the other coordination sites and additional waters in the extracellular vestibule and the midchannel cavity (Garofoli et al., 2002) using the CVFF force field of the InsightII/Discover (Accelerys). The mean distances between coordinating oxygens and the ion established the quantity RIon-Surr. At the Born cavity boundary an atom physically excludes its neighbors because its electron density becomes significant and overlaps strongly with the solvating species. At this boundary point the surroundings become polarizable. Operationally, we define this cavity radius, Rcav, as the difference between RIon-Surr and oxygen's steric radius. In estimating cavity size we use an oxygen steric radius of 1.35 Å, a compromise between the more common value of 1.4 Å and the value of 1.3 Å suggested by quantum studies of cation interaction with N-methylacetamide (Roux and Karplus, 1995). The corresponding cavity radii are listed in Table 3. Except for sodium, all differ little (<0.1 Å) from the ionic crystal radii at filter sites 1–4*. The associated free energy is

|

(6) |

the second term is computed by the procedure of Beveridge and Schnuelle (1975) using the water model described above (see also Dorman and Jordan (2003)).

TABLE 3.

Mean ionic cavity radii (in Å) for various cations at the filter sites discussed in the model

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | 1.23 | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.03 |

| K+ | 1.38 | 1.43 | 1.40 | 1.32 |

| Rb+ | 1.57 | 1.48 | 1.50 | 1.44 |

| Cs+ | 1.65 | 1.61 | 1.66 | 1.56 |

| Ba2+ | 1.43 | 1.44 | 1.43 | 1.38 |

The last step (stabilization, Eq. 4c) is simulated via thermodynamic integration, using a Monte Carlo (MC) algorithm, transforming a water to an ion in the selectivity filter, while simultaneously transforming an ion in the dielectric background into a water (Tembe and McCammon, 1984). We use MC instead of MD as the computational demands are much less stringent and our focus is thermodynamics, not dynamics. MC is less prone to be affected by the abrupt and distinct filter-water and filter-cavity boundaries. Furthermore, the loss of correlation in successive steps inherent to MC, accomplished by random moves, provides better statistical quality than MD. The associated free energy change is computed in the standard fashion (Tembe and McCammon, 1984),

|

(7) |

where  indicates canonical averaging in an equilibrium ensemble corresponding to a partially transmuted state. The Hamiltonian H(λ) is

indicates canonical averaging in an equilibrium ensemble corresponding to a partially transmuted state. The Hamiltonian H(λ) is

|

(8) |

where Hwater and Hion describe all interactions involving the water and the ion at the position being transmuted; Hother describes interactions involving all the other mobile species. The Hamiltonians incorporate terms describing electrostatic and steric interaction among the waters, ions and carbonyls (including their reaction fields) and electrostatic interaction between these mobile sources and the fixed charges.

For an ion at the cavity center a different procedure is used. Instead of the decomposition of Eq. 4, the transfer free energy from bulk water is computed using the approach outlined by Roux and MacKinnon (1999). Several contributions are treated exactly: the Born energy for transferring an ion into the cavity, the reaction field, and interaction with fixed charges. Interaction with reorientable carbonyls relies on a mean field argument, assuming each is frozen in its average orientation. Interaction with waters is determined assuming each is independently statistically oriented by the cavity ion. The total stabilization for a monovalent cation, −16.7 kT, differs little from Roux and MacKinnon's (1999) value of −14.2 kT; the discrepancy most likely reflects different descriptions of the pore. In our model it contains explicit waters; in their treatment it is a dielectric continuum with ɛ = 80.

The computational grid

In our implementation of the thermodynamic perturbation process, on the fly computation of the interactions between all species was time consuming and inefficient. We precomputed these terms using discrete configurational arrays with rotational intervals (for waters and carbonyl Os) of ≤30° and translational intervals of 0.25 Å in both axial and radial directions (for ions and waters), yielding stabilization free energies (see below) reliable to ±1 kJ/mol. The same basic energy grid could be reused for calculations involving variable ion occupancy scenarios and the same configuration could be sampled repeatedly without requiring redetermination of the energy. All computations were carried out at 300 K. Acceptance ratios for water reorientations were ∼0.3. Because the selectivity filter is constricted (Doyle et al., 1998; Roux and MacKinnon, 1999; Shrivastava and Sansom, 2000; Bernèche and Roux, 2000), permitting relatively little angular movement of the COs, typical acceptance ratios for CO reorientations were low, ∼0.15. The carbonyl oxygens are almost all in steric contact, which severely reduces their ability to move. This is especially the case in MC where concerted motion in statistically unlikely if more than one group must move at once, or impossible (our case) if only individual groups are mobile. As a result the carbonyl scaffold is very constrained. The waters rotate quite freely but are restricted in translation due to the immobility of the surrounding carbonyls. So the carbonyls' immobility not only impedes carbonyl reorientation but it partially freezes the waters as well.

Dividing the thermodynamic integral into 80 intervals eliminated hysteresis. Convergence of the Monte Carlo integration was tested by comparing the free energy changes for the forward and reverse transmutations; stability was assumed if results differed by <0.1 kT. Due to the low acceptance ratios analysis of each interval commenced with 106 equilibration steps followed by 1.2·107 steps of data collection. Because of the precalculated energy grid this made no outsize computational demands. To minimize correlations data were collected at every fifth step. To estimate statistical error, three separate jobs were run for each configuration.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Individual features

In modeling permeation, we exchange water in the ion-binding cavity for an ion in vacuum, the cavity term summarized by Eq. 4b. The structural term, accounting for stabilization due to the realignment of waters and carbonyls in transmuting a channel water into an ion is the thermodynamic perturbation term, Eq. 4c. Within the filter, the cavity terms are roughly binding site independent (though there are significant differences among the cations); much of the variation between the solvating effectiveness at each carbonyl binding pocket (1-3) is a consequence of the structural component, Eq. 4c. We first consider this.

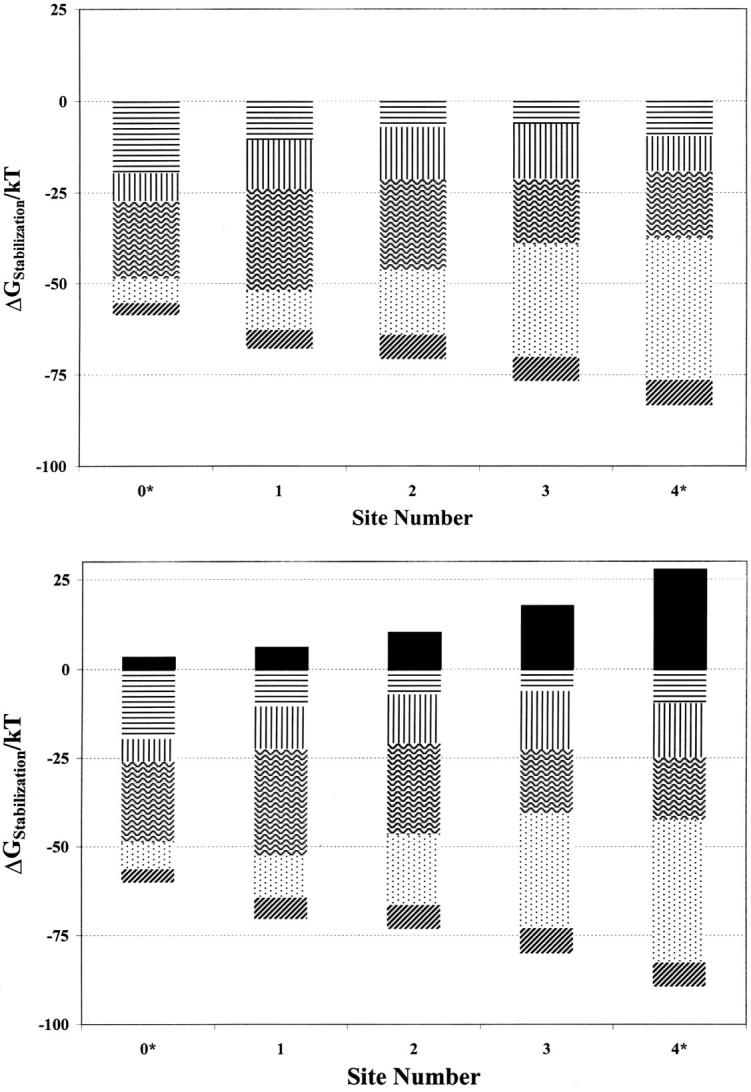

The structural contribution that each feature makes to ionic stabilization can be assessed both individually and collectively (Garofoli et al., 2002). Here we consider a potassiumlike cation (RI = 1.3 Å). Fig. 3, a and b, depict the site dependence of the contribution of each explicit feature to the reorientational free energy, expressed in kT. As cavity radii in the channel interior show little site variation (see Table 3), energetic comparison provides insight into the interplay of the individual elements.

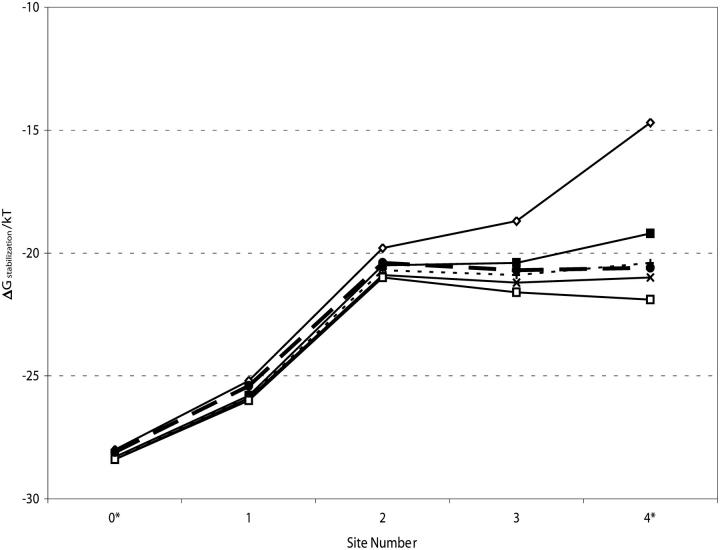

FIGURE 3.

Individual contributions of the various electrical features to the stabilization energy of a monovalent cation (R = 1.3 Å) at various locations in the model KcsA filter with (top) the cavity unoccupied, and (bottom) the cavity occupied: continua induced reaction fields (horizontal lines), single file waters (vertical lines), binding pocket carbonyls (wavy lines), oriented α-helices (stippled area), charged residues (dark diagonal lines), cavity ion (solid).

Interpretation is straightforward. First consider Fig. 3 a, with an unoccupied cavity. The effect of water (the combined influence of the single file and the reaction field due to the aqueous continua, both bulk and cavity) is almost constant, always ∼20–25 kT, slightly smaller near the cavity and slightly larger toward the extracellular side. The effect of the carbonyls is strongest at sites 1 and 2, where there is eightfold ion-oxygen coordination. It is weaker at the extreme positions (0* and 4*), where only one ring of four oxygens contributes to stabilization. The origin of the surprisingly low influence of the carbonyls at site 3 is not obvious because here too there is eightfold ion-carbonyl coordination. At the filter's interior sites the ion-carbonyl interaction is swamped by the large contribution from the macrodipoles pointing toward the water cavity. In addition to their primary role in stabilizing the ion at the cavity's center (Doyle et al., 1998; Roux and MacKinnon, 1999) these macrodipoles interact very strongly with ions in the selectivity filter, especially at the innermost sites, 3 and 4*. The net influence of the charged residues (Asp80, Arg64, Glu51, and Arg52) is relatively small because, in conjunction with their images, they form electrical dipoles.

Fig. 3 b illustrates the effect of cavity occupation. The cavity ion of course destabilizes an ion in the filter, but the effect drops off rapidly (faster than inversely with distance) as the ion moves outward. Comparison of Fig. 3, a and b, provides one surprise. The single file water contribution to stabilizing an ion at site 4* is noticeably larger when there is an ion in the cavity. The cavity ion and a site 4* ion cooperate to increase the axial electric field in the filter promoting improved water alignment, which leads to increased ion-water interaction energy within the filter, analogous to results of Guidoni et al. (2000). All other features are stabilizing, and qualitatively differ little from the empty cavity scenario.

No one feature dominates structural contributions to ionic stabilization. Even at the external crystallographic site (site 1) the macrodipoles are essential, contributing ∼30–35% of the structural stabilization energy from either the water or the carbonyls. At site 3, the macrodipoles are about twice as important as either the carbonyl oxygens or the waters. Structural stabilization due to ion-water interaction is important everywhere and always comparable to that from ion-carbonyl interaction. Both continuum (reaction field) and single file waters contribute significantly to the ion-water interaction term, even for ions in midfilter.

Comparison of site energetics with mobile groups (here water and carbonyls) acting jointly or individually permits determining whether they cooperate or interfere in stabilizing the ion. At all sites (data not shown) there is either slight (∼1 kT) cooperativity or neutral behavior; i.e., the contributions of the two groups are roughly superimposable.

The role of the cavity

A strength of the method is the ease with which it lends itself to thought experiments with a reengineered channel architecture. This permits assessing the role and significance of individual structural features. In the protein these parameters are constrained; however hypothetical scenarios provide insight into why the structure evolved as it has.

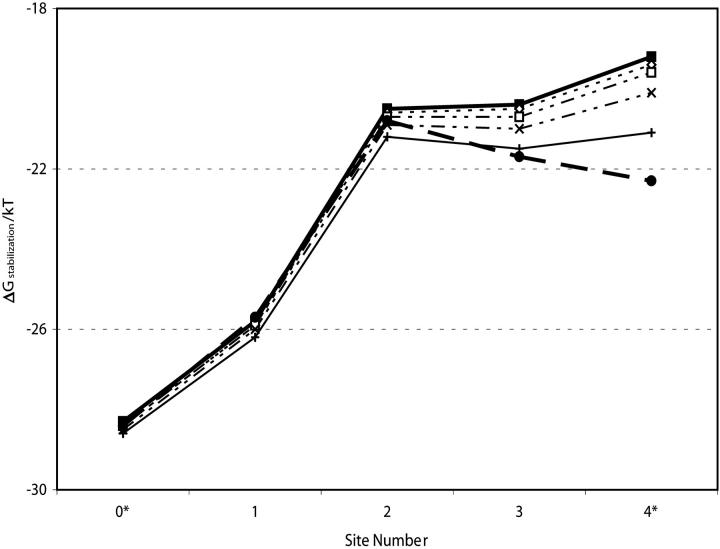

The aqueous cavity's main role is to stabilize its incorporated cation. The individual feature analysis suggests that it might also stabilize ions in the filter. We considered what would happen if the cavity size were changed by gradually increasing the cavity radius to 8.5 Å, quintupling the amount of water incorporated; the cavity center was moved correspondingly inwards to maintain the cavity-filter boundary. Fig. 4 shows that the cavity size has fairly little energetic influence within the carbonyl binding pockets (1, 2, and 3); even quintupling the amount of cavity water only decreases the ionic energy by 1.25 kT at the inner binding pocket (3). Totally eliminating the cavity also has amazingly little influence on monovalent ion energetics within the filter; energy would increase by 1.75 kT at the inner binding pocket (3). However, at the cavity-filter boundary site (4*) filter ions' energies are strongly influenced by the cavity. Two single file waters totally insulate filter ions from the intracellular domain; even one is quite effective. This is quite generally true; were the cavity removed and substituted by an extended chain of single file waters (data not shown) energetics are affected only at sites 4* and 3. To test the high ɛ continuum approximation the physiological (5 Å) cavity was modeled by incorporating 20 explicit waters (Garofoli et al., 2002); except at site 4*, results differed trivially from those based on the “conducting water” approximation.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of cavity size on stabilization free energy of a monovalent cation (R = 1.3 Å) at various locations in the selectivity filter as a function of cavity radius, R (in Å): R = 0, ⋄; R = 5, ▪; R = 6.4, +; R = 7.1, x; R = 8.5, □; R = 5, 20 explicit waters (see text), •.

The inner pore is lined with hydrophobic residues presumed to have no chemical or functional effect on channel selectivity. During gating its structure changes significantly whereas the selectivity filter's structure appears essentially unaltered (Jiang et al., 2002), consistent with the original suggestion of a rigid domain (Doyle et al., 1998). As gating does not substantially modify the filter, the position of the other features included in our model are unchanged; thus an analysis of permeation energetics based on the crystallographic “closed” state filter structure may plausibly be expected to depict behavior in the “open” state. Fig. 5 assesses the inner pore's influence on selectivity filter energetics by reducing membrane thickness, bringing cytoplasmic water ever closer to the cavity, in essence shortening the inner pore. In another experiment, we simulated an open inner pore by deforming the cavity into a tube filled with 72 explicit waters extending to the cytoplasm (Garofoli et al., 2002). The cavity always insulates ions within the carbonyl binding pockets from changes in inner pore geometry. Even were it eliminated completely, or deformed into an open state pore, ionic energies at these locations would decrease by <1 kT. Only at site 4*, the filter-cavity boundary, would changes in the inner pore geometry be energetically important.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of inner pore on stabilization free energy of a monovalent cation (R = 1.3 Å) at various locations in the selectivity filter as a function of distance, W (in Å), from the cytoplasm: W = 16, ▪; W = 12, ⋄; W = 8, □; W = 4, x; W = 0, +; “open state” (see text), •.

Permeation energetics

Permeation, characterized by high selectivity and high throughput, involves major energetic compromises. Selectivity demands highly structured coordination sites so that an ion, relative to water, tends to be very stable when bound in the filter. This state, however, cannot be too stable, or conductivity would decrease; in the extreme case this would lead to self-inflicted block (Jordan, 2002). For permeation to be possible the associated free energy changes must be fairly close to zero. Potassium channels, being multiply occupied, solve this dilemma in a unique way. All calculations are consistent with the notion that single ions are strongly bound and that even with two ions in the filter the channel remains blocked (Shrivastava and Sansom, 2000; Chung et al., 1999; Allen et al., 1999b). A third ion, entering from the cytoplasmic side, is required to relieve this block and knock an ion out of the filter (Hodgkin and Keynes, 1955; Hille and Schwartz, 1978; Neyton and Miller, 1988a,b; Chung et al., 2002b; Jordan, 2002).

Our computational idealization was not designed to quantitatively reproduce the absolute free energies of permeation for the various cations, and unsurprisingly, did not do so. But it should be noted that similar problems even plague all atom simulations with the best tuned force fields; these, when used to describe even a simple system like gramicidin, yield quite unrealistic permeation free energies (Allen et al., 2003). In addition to the simplicity of our model, uncertainties in determining the ionic coordination cavity radii, Rcav (Table 3), have energetic consequences since the ionic transfer free energy ∝1/Rcav; changing Rcav by 0.1 Å changes ionic free energies of the monovalent ions by ∼10 kT. As uncertainties are systematic, reflecting the force field used, we can still meaningfully compare permeation energies for various cations and for various filter occupancy scenarios. However, to compensate for limitations due to the restricted number electrical features included, we computed the interaction energy between axial filter ions and those partially charged groups not explicitly treated in the model, including the reaction field. Since GROMOS assigns the same carbonyl partial charges as we, GROMOS charge parameters were used to estimate the influence of those features not explicitly part of the model of Fig. 1. These energies were always destabilizing and ranged between 4 and 10 kT in the filter.

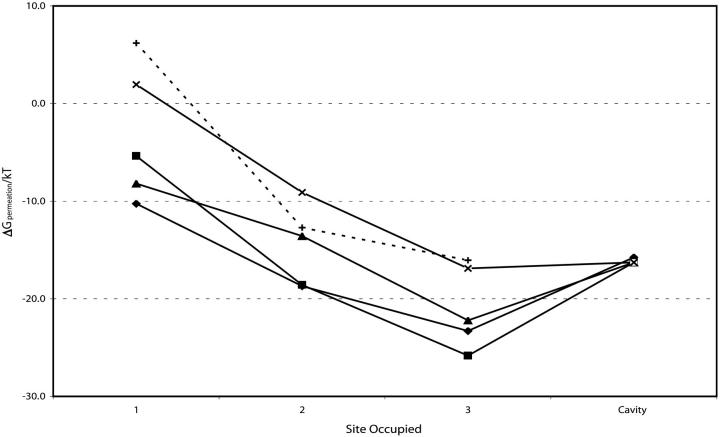

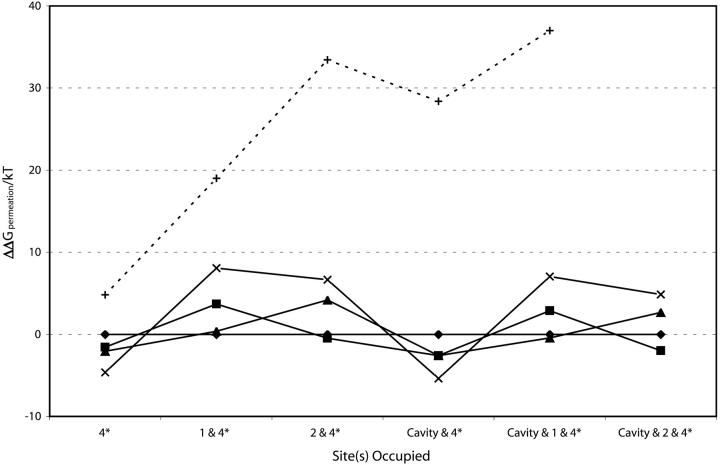

Figs. 6–8 compare permeation free energies for the alkali cations and barium, including the residual background correction.

Figs. 6 and 7 show that, regardless of filter occupancy, the permeation energy profiles for K+ and Rb+ are roughly similar, with Cs+ noticeably less stable, consistent with known behavior in K-channels and in KcsA in particular (Hille, 2001; LeMasurier et al., 2001). Occupancy preference for the carbonyl binding pockets differs depending upon whether an ion is in the aqueous cavity. With no cavity ion, we find that K+ occupancy of site 3 to be most likely, unlike previous calculations where site 2 was favored (Burykin et al., 2002). With an occupied cavity, ionic repulsion drives the filter ion outward; for K+, we find that occupancy of site 2 is favored, similar to earlier work (Shrivastava and Sansom, 2000; Åqvist and Luzhkov, 2000; Burykin et al., 2002).

At the carbonyl binding pockets Na+ is substantially less stable in the channel than are the potassium or rubidium, generally by ∼10 kT per sodium ion in the filter. The difference is significant, meaningful even for the idealization used, and consistent with the exclusion of Na+ from the narrow filter. In the binding pockets sodium's solvation structure differs sharply from that of the large cations (Garofoli et al., 2002; Shrivastava et al., 2002). It is coordinated by four carbonyl oxygens and two waters (or five and one) unlike the larger cations, which are typically coordinated by eight carbonyl oxygens.

Comparing the three terms in the permeation free energy (Eqs. 4a, 4b, and 4c) indicates that, viewed from this perspective, Na+ is excluded because its binding cavity in the filter is much larger than its hydration cavity. For Na+ the cavity contribution (Eq. 4b) doesn't come close to compensating for the dehydration energy. For K+ it does; the radius of binding pocket differs little from the ion's hydration radius. Our K+/Na+ energy gaps are roughly comparable to those of earlier estimates (Luzhkov and Åqvist; 2001; Allen et al., 2000; Bernèche and Roux, 2001).

The favored double occupancy state has one ion in the cavity and one in the filter, consistent with earlier computations (Shrivastava and Sansom, 2000; Åqvist and Luzhkov, 2000; Burykin et al., 2002).

Of the possible multiple occupancy scenarios considered (Fig. 7), the configuration with the filter doubly occupied by sodium exhibits the largest K+/Na+ discrimination.

Cavity occupancy destabilizes the doubly occupied filter (Fig. 7, sites 1 and 3 occupied) by ∼10 kT, consistent with the experimental inference that the channel is in a three-ion mode when functional (Hodgkin and Keynes, 1955; Hille and Schwartz, 1978) and with previous computational studies (Shrivastava and Sansom, 2000; Bernèche and Roux, 2000; Åqvist and Luzhkov, 2000; Chung et al., 1999, 2002a; Allen et al., 1999b).

The triply occupied state is roughly isoenergetic with three cations hydrated in bulk water; the overall free energy balance hinges crucially on interaction with the rest of the peptide (the groups not explicitly treated in the model). Excluding these terms, the free energy of the ions in the triply occupied filter would have been ∼15 kT less than that of three independent hydrated cations.

The barium data of Fig. 6 suggest that single Ba2+ occupancy of the carbonyl binding pockets could be competitive with potassium or rubidium. In the multiple occupancy scenarios of Fig. 7 (a barium in the filter and a monovalent cavity ion) barium occupancy is never competitive, and generally less likely than occupancy by Na+.

FIGURE 6.

Permeation free energy for single cation occupancy of selected sites of the model KcsA channel (K+, ♦; Rb+, ▪; Cs+, ▴; Na+, x; Ba2+, +).

FIGURE 8.

Permeation free energy for various cation occupancies of selected sites of the model KcsA channel; site 4* is always occupied. All energies are measured relative to that for K+ occupancy of these sites (K+, ♦; Rb+, ▪; Cs+, ▴; Na+, x; Ba2+, +).

FIGURE 7.

Permeation free energy for multiple cation occupancy of selected sites of the model KcsA channel (K+, ♦; Rb+, ▪; Cs+, ▴; Na+, x; Ba2+, +).

Fig. 8 depicts energetics with site 4* occupied, always relative to potassium-filter energies. This site differs qualitatively from the carbonyl binding pockets. Here Na+ is energetically competitive with the large alkali cations, regardless of cavity occupancy, consistent with the fact that Na+ can block outward current (Bezanilla and Armstrong, 1972; French and Wells, 1977; Yellen, 1984b; Heginbotham et al., 1999) and in accord with other free energy perturbation studies (Luzhkov and Åqvist, 2001; Allen et al., 2000). However, two sodium ions are never comfortable in the carbonyl binding pockets. At this location, barium can also compete favorably with potassium, an observation in essential accord with structural and electrophysiological evidence that the barium block site lies between the cavity and the narrow part of the filter (Jiang and MacKinnon, 2000; Neyton and Miller, 1988a,b). Given the enormous energetic compensation required in dehydrating barium and resolvating it in the filter (its absolute dehydration energy is ∼540 kT, almost four times that of potassium), it is quite striking that the SMC analysis roughly accommodates this energy balance.

The major observations are that ion-filter interaction is roughly comparable for potassium and rubidium, that it is somewhat unfavorable for cesium and substantially unfavorable for sodium, and that both sodium and barium can effectively displace potassium at the cavity-filter boundary domains. What model features account for these results? From our perspective, ionic stabilization is the sum of the two terms, Eqs. 4b and 4c. The first involves taking an ion from vacuum and placing it in a cavity in a low dielectric milieu. In the second step the peptide, in particular the carbonyl groups forming the binding pockets, is reoriented by interaction with the ion.

In the carbonyl binding pockets the Born cavity contributions for each ion considered (Eq. 4b) differ by ∼2–3 kT. Reorientational stabilization (Eq. 4c) varies by typically triple as much. Thus, for a given ion, peptide realignment is more important for stability in the filter.

Why is sodium unstable in the carbonyl binding pockets? As originally suggested by Bezanilla and Armstrong (1972), given a structural rationale by Doyle et al. (1998) and consistent with a series of simulational studies (Åqvist and Luzhkov, 2000; Allen et al., 1999b, 2000) potassium fits optimally at these sites. While they expand to accommodate rubidium (easily) and cesium (at substantial energetic cost), they don't contract enough to cradle sodium. For the larger alkali cations, as well as for barium, mean ion-oxygen distances in the binding pockets roughly equal ionic hydration radii (with differences <0.1 Å). For sodium the differences are significant; cavity radii are ∼0.3 Å larger than sodium's hydration radius (0.95 Å). For sodium, the Born contribution to the total energy is far smaller and relatively insufficient to compensate for sodium's large dehydration energy. It should be noted that this motif, whereby filter size and rigidity provide the physical basis for preferential adsorption of larger ions over smaller ones, is well known in inorganic ion exchange. In particular, ion-exchange selectivities in zeolites generally favor adsorption of larger ions over smaller ones, e.g., K+ over Na+ and Ca2+ over Mg2+, because the smaller ions are preferentially hydrated (Sherry, 2003). But this remains an unsettled issue in potassium channels; some studies argue that K+/Na+ discrimination is a highly cooperative effect, involving far more than ion interaction with the binding pocket carbonyls alone (Bernèche and Roux, 2000, 2001; Biggin et al., 2001).

Why is behavior at cavity-filter boundary (site 4*) different? Here binding of either sodium or barium is roughly competitive with binding to the larger alkali cations. For barium this seems to reflect the influence of the nearby macrodipoles. Fig. 3, a and b, show that the stabilization energy is largest at this interior site, mainly due to interaction with the α-helices, accounting for half the structural contribution to stabilization. Doubling the ionic charge more than doubles the stabilizational contribution. Even with the limited structural reorganization permitted in this realization of the SMC approach, ion-protein electrical interaction does not simply scale with ionic charge; the dielectric environment is responding in a nonlinear fashion, precisely what is expected (Partenskii and Jordan, 1992b). Increased sodium stabilization at site 4* reflects its escape from the rigid binding pockets. The ion effectively coordinates water on the cavity side and also closely approaches the carbonyls on the filter side. As indicated in Table 3, the mean ion-oxygen distance is much smaller. The Born cavity radius only slightly exceeds sodium's hydration radius and the Born term (Eq. 4b) more closely compensates for the ionic dehydration energy.

How reliable is this type of analysis, designed to compare the behavior of different monovalent ions in the various binding pockets within the filter? Based on similar modeling of gramicidin (Dorman et al., 1996), energy differences of a few kT are too small to be meaningful. However, general trends among the monovalent ions are significant. What about the barium computations? While monovalent-divalent free energy differences are quite sensitive to the choice of oxygen's steric radius, carbonyl binding pocket or site 4* occupancy involving a single barium is always roughly competitive (within ∼10 kT) with potassium or rubidium, an important result because barium's absolute dehydration free energy is four times that of the similarly sized potassium ion.

We have treated the Glu71 as fully protonated, consistent with analyses of Luzhkov and Åqvist (2000) and Bernèche and Roux (2002); however, work by Ranatunga et al. (2001) suggests that there may be significant proton transfer to the Asp80s, leaving both residues partially charged. We have considered the consequences by incorporating the glutamates in the computational model, and determining what effect this would have on Ba2+/K+ partitioning in the filter (sites 1–4*). The Glu71 residues are more deeply embedded in the low ɛ region than are the Asp80s so that their influence on ions in the channel is much less strongly counterbalanced by the reaction field. Proton transfer from glutamate to aspartate makes the potential along the filter axis significantly more negative; as the Glu71s become more charged, barium binding at the filter sites is ultimately favored. The effect can be summarized briefly. The switch from potassium to barium occupancy occurs at ∼25% transfer for sites 2 to 4* and at ∼75% transfer for site 1. With >25% proton transfer, barium occupancy would be favored at most sites, leading to significant block and loss of potassium conduction. The fact that barium binding is observed in the vicinity of site 4* (Jiang and MacKinnon, 2000; Neyton and Miller, 1988a,b), and nowhere else in the channel, suggests that there is probably only limited proton transfer, and that the complete transfer suggested recently (Ranatunga et al., 2001) is highly unlikely. What is unequivocal is that full deprotonation of both the Asp80s and the Glu71s would so favor barium binding in the filter either to totally block the channel, or to make it barium selective.

SUMMARY

We have analyzed the permeation free energy for transferring ions from bulk water into the selectivity filter of the KcsA K+ channel using thermodynamic Monte Carlo integration, in the framework of the semimicroscopic method. We separately investigated the stabilizational influence of the various features modeled, assessed cooperativity and performed “thought experiments” involving modifications of the channel's architecture. In addition, we determined relative permeation free energies for a variety of occupancy scenarios (single, double, triple) and some important cations (Na+, K+, Rb+, Cs+, Ba2+). The approach is designed to provide qualitative and semiquantitative insight into the permeation process, to aid in deconstructing the influence of individual structural features, and to facilitate ionic comparisons.

Water's contribution to stabilization is roughly the same at all five sites considered; the effect of the carbonyls is maximal at the central sites, where there is eightfold ion-carbonyl coordination; the helices' role is strongest at the innermost sites, whereas the opposite is true for the charged residues (Asp80, Arg64, Glu51, and Arg52) near the extracellular interface. The cavity ion destabilizes ions in the selectivity filter, but repulsion is heavily shielded, falling more rapidly than 1/R. It also has a polarizing effect on single file waters, increasing their ability to stabilize an ion at the filter-cavity boundary. Except for this, contributions of mobile groups are roughly superimposable; there is no significant cooperativity.

The cavity, in addition to stabilizing the midchannel ion, is an electrostatic buffer, shielding ions in the filter from structural changes that may occur in the inner pore.

Within the carbonyl binding pockets the permeation free energies of K+ and Rb+ are roughly equal, Cs+ is generally less stable than either, and Na+ is substantially disfavored, by ∼10 kT per sodium, all in agreement with experiment. Similar to behavior in ion-exchange zeolites, the filter's inability to stabilize sodium is here a consequence of its rigidity; the solvation cavity is too large and the self-energy contribution does not adequately compensate for sodium's large dehydration energy. For the monovalent ions the most stable state has an ion in the cavity and another in the selectivity filter. The destabilization associated with triple occupancy is consistent with this being the functional mode. Single barium occupancy of the carbonyl binding pockets need not be outrageously unfavorable. Behavior at site 4*, the cavity-filter boundary, is distinctly different; here both Na+ and Ba2+ compete quite effectively with K+, an observation consistent with this being in the vicinity of the “barium blocker” site and with the sodium block of outward current. The actual site occupancy picture is somewhat confusing. For K+, our double occupancy results agree with previous computations (Shrivastava and Sansom, 2000; Åqvist and Luzhkov, 2000; Burykin et al., 2002) but do not accord with the crystallographic interpretation of conductance data (Morais-Cabral et al., 2001). There are no other computations for Rb+, but our analysis is not consistent with experiment.

Proton transfer from the Glu71s to the Asp80s increases the likelihood of barium binding in the filter. Only partial transfer is consistent with the filter favoring potassium occupancy. Fully deprotonating both acidic residues would appear to totally alter the selectivity of the channel, making it more suitable for divalent ions than monovalent ones.

The model is being augmented to incorporate more detail (Miloshevsky and Jordan, 2002). In particular, it can be modified to incorporate explicit waters in both the cavity and the pore mouth, to permit the efficient sampling of the influence of Thr75 residues, and to allow for ion-induced filter expansion and contraction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rob Blaustein, Joe Mindell, and the referees for their helpful comments.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM-28643). Debi Patangia determined the data of Table 3 and Gennady Miloshevsky computed free energies for the examples where the aqueous cavity contains explicit waters.

S. Garofoli's present address is Universitá di Roma “La Sapienza”, Dipartimento di Fisica, P.le Aldo Moro 5 00185 Rome, Italy.

References

- Allen, T. W., T. Bastug, S. Kuyucak, and S. H. Chung. 2003. Gramicidin A channel as a test ground for molecular dynamics force fields. Biophys. J. 84:2159–2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T. W., A. Bilznyuk, A. P. Rendell, S. Kuyucak, and S. H. Chung. 2000. The potassium channel: structure, selectivity and diffusion. J. Chem. Phys. 112:8191–8204. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T. W., M. Hoyles, S. Kuyucak, and S. H. Chung. 1999a. Molecular and Brownian dynamics study of ion selectivity and conductivity in the potassium channel. Chem. Phys. Lett. 313:358–365. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T. W., S. Kuyucak, and S. H. Chung. 1999b. Molecular dynamics study of the KcsA potassium channel. Biophys. J. 77:2502–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åqvist, J., and V. Luzhkov. 2000. Ion permeation mechanism of the potassium channel. Nature. 404:881–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernèche, S., and B. Roux. 2000. Molecular dynamics of the KcsA K+ channel in a bilayer membrane. Biophys. J. 77:2517–2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernèche, S., and B. Roux. 2001. Energetics of ion conduction through the K+ channel. Nature. 414:73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernèche, S., and B. Roux. 2002. The ionization state and the conformation of Glu-71 in the KcsA K+ channel. Biophys. J. 82:772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge, D. L., and G. W. Schnuelle. 1975. Free energy of a charge distribution in concentric dielectric continua. J. Phys. Chem. 79:2562–2573. [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla, F., and C. M. Armstrong. 1972. Negative conductance caused by entry of sodium and cesium ions into the potassium channels of squid axon. J. Gen. Physiol. 60:588–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggin, P. C., G. R. Smith, I. Shrivastava, S. Choe, and M. S. P. Sansom. 2001. Potassium and sodium ions in a potassium channel studied by molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1510:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burykin, A., C. N. Schutz, J. Villá, and A. Warshel. 2002. Simulations of ion current in realistic models of ion channels: the KcsA potassium channel. Proteins. 47:265–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S. H., T. W. Allen, M. Hoyles, and S. Kuyucak. 1999. Permeation of ions across the potassium channel: Brownian dynamics studies. Biophys. J. 77:2517–2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S. H., T. W. Allen, and S. Kuyucak. 2002a. Conducting-state properties of the KcsA potassium channel from molecular and Brownian dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 82:628–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S. H., T. W. Allen, and S. Kuyucak. 2002b. Modeling diverse range of potassium channels with Brownian dynamics. Biophys. J. 83:263–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauber-Osguthorpe, P., V. A. Roberts, D. J. Osguthorpe, J. Wolff, M. Genest, and A. T. Hagler. 1988. Structure and energetics of ligand binding to proteins: E. coli dihydrofolate reductase-trimethoprim, a drug-receptor system. Proteins: Struc. Func. and Genet. 4:31–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman, V. L., S. Garofoli, and P. C. Jordan. 1999. Ionic interactions in multiply occupied channels. In Gramicidin and Related Ion-Channel Forming Peptides. Novartis Found. Symp. 225, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester. 153–169. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dorman, V. L., and P. C. Jordan. 2003. Ion-water interaction potentials in the semi-microscopic model. J. Chem. Phys. 118:1333–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Dorman, V. L., M. B. Partenskii, and P. C. Jordan. 1996. A semi-microscopic Monte Carlo study of permeation energetics in a gramicidin-like channel: the origin of cation selectivity. Biophys. J. 70:121–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, D. A., J. M. Cabral, R. A. Pfuetzner, A. Kuo, J. M. Gulbis, S. L. Cohen, B. T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 1998. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 280:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutzler, R., E. B. Campbell, M. Cadene, B. T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 2002. X-ray structure of a ClC chloride channel at 3.0 A reveals the molecular basis of anion selectivity. Nature. 415:287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, W., J. Brickmann, and P. Läuger. 1981. Molecular dynamics study of ion transport in transmembrane protein channels. Biophys. Chem. 13:105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French, R. J., and J. B. Wells. 1977. Sodium ions as blocking agents and charge carriers in the potassium channel of squid giant axon. J. Gen. Physiol. 70:707–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, D., A. Libson, L. J. W. Miercke, C. Weitzman, P. Nollert, J. Krucinski, and R. M. Stroud. 2000. Structure of a glycerol-conducting channel and the basis for its selectivity. Science. 290:481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofoli, S., G. Miloshevsky, V. L. Dorman, and P. C. Jordan. 2002. Permeation energetics in a model potassium channel. In Ion Channels-from Atomic Resolution to Functional Genomics. Novartis Found Symp 245, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester. 109–122. [PubMed]

- Grunwald, E. 1996. Thermodynamics of Molecular Species. Wiley-Interscience, New York.

- Guidoni, L., V. Torre, and P. Carloni. 2000. Water and potassium dynamics inside the KcsA K+ channel. FEBS Lett. 477:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, H. A., G. E. Kirsch, J. A. Drew, M. Taglialatela, R. H. Joho, and A. M. Brown. 1991. Exchange of conduction pathways between two related K+ channels. Science. 251:942–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heginbotham, L., L. LeMasurier, L. Kolmakova-Partensky, and C. Miller. 1999. Single Streptomyces lividans K+ channels: functional asymmetries and sidedness of proton activation. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:551–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille, B. 2001. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3rd Ed. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, MA.

- Hille, B., and W. Schwartz. 1978. Potassium channels as multi-ion single-file pores. J. Gen. Physiol. 72:409–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille, B., C. M. Armstrong, and R. MacKinnon. 1999. Ion channels: from idea to reality. Nat. Med. 5:1105–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin, A., and R. Keynes. 1955. The potassium permeability of a giant nerve fibre. J. Physiol. 121:61–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hol, W. G., P. T. Van Duijnen, and H. J. Berendsen. 1978. The alpha-helix dipole and the properties of proteins. Nature. 273:443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer, G., L. R. Pratt, and A. E. Garcia. 1996. Free energy of ionic hydration. J. Phys. Chem. 100:1206–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, J. K., and T. Ichiye. 1997. Understanding the born radius via computer simulations and theory. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101:3596–3604. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J. D. 1962. Classical Electrodynamics. Wiley, New York.

- Jiang, Y., and R. MacKinnon. 2000. The barium site in a potassium channel by X-ray crystallography. J. Gen. Physiol. 115:269–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., A. Lee, J. Chen, M. Cadene, B. T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 2002. The open pore conformation of potassium channels. Nature. 417:523–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P. C. 2002. Unclogging a pipe: potassium channel pinball. Biophys. J. 83:2–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch, W., and C. Sander. 1983. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 22:2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W. K., and P. C. Jordan. 1984. Molecular dynamics simulation of cation motion in water-filled gramicidin-like pores. Biophys. J. 46:805–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, F. S., and A. Warshel. 1992. A local reaction field method for fast evaluation of long range electrostatic interactions in molecular simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 97:3100–3107. [Google Scholar]

- LeMasurier, M., L. Heginbotham, and C. Miller. 2001. KcsA: it's a potassium channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 118:303–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzhkov, V., and J. Åqvist. 2000. A computational study of ion binding and protonation states in the KcsA potassium channel. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1481:360–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzhkov, V., and J. Åqvist. 2001. K+/Na+ selectivity of the KcsA potassium channel from microscopic free energy perturbation calculations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1548:194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, R., and G. Yellen. 1990. Mutations affecting TEA blockade and ion permeation in voltage-activated K+ channels. Science. 250:276–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C. 2001. See potassium run. Nature. 414:23–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miloshevsky, G., and P. C. Jordan. 2002. Deconstructing permeation energetics in a model potassium channel selectivity filter. Biophys. J. 82:199a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais-Cabral, J., Y. Zhou, and R. MacKinnon. 2001. Energetic optimization of ion conduction rate by the K+ selectivity filter. Nature. 414:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata, K., K. Mitsuoka, T. Hirai, T. Walz, P. Agre, J. B. Heymann, A. Engel, and Y. Fujiyoshi. 2000. Structural determinants of water permeation through aquaporin-1. Science. 407:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyton, J., and C. Miller. 1988a. Potassium blocks barium permeation through the high conductance Ca2+ activated potassium channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 92:549–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyton, J., and C. Miller. 1988b. Discrete Ba2+ block as a probe of ion occupancy and pore structure in the high conductance Ca2+- activated K+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 92:569–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partenskii, M. B., M. Cai, and P. C. Jordan. 1991. A dipolar chain model for the electrostatics of transmembrane ion channels. Chem. Phys. 153:125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Partenskii, M. B., V. Dorman, and P. C. Jordan. 1994. Influence of a channel-forming peptide on energy barriers to ion permeation, viewed from a continuum dielectric perspective. Biophys. J. 67:1429–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partenskii, M. B., V. L. Dorman, and P. C. Jordan. 1998. Membrane stability under electrical stress. A non-local electroelastic treatment. J. Chem. Phys. 109:10361–10371. [Google Scholar]

- Partenskii, M. B., and P. C. Jordan. 1992a. Theoretical perspectives on ion channel electrostatics. Continuum and microscopic approaches. Q. Rev. Biophys. 24:477–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partenskii, M. B., and P. C. Jordan. 1992b. Nonlinear dielectric behavior of water in transmembrane ion channels: ion energy barriers and the channel dielectric constant. J. Phys. Chem. 96:3906–3910. [Google Scholar]

- Pauling, L. 1960. The Nature of the Chemical Bond, 3rd Ed. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

- Pethig, R. 1979. Dielectric and Electronic Properties of Biological Materials. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Chichester.

- Pliego, J. R., Jr., and J. M. Riveros. 2000. On the calculation of the absolute solvation free energy of ionic species: application of the extrapolation method to the hydroxide ion in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. B. 104:5155–5160. [Google Scholar]

- Ranatunga, K. M., I. H. Shrivastava, G. R. Smith, and M. S. P. Sansom. 2001. Side-chain ionization states in a potassium channel. Biophys. J. 80:1210–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randles, J. E. B. 1956. The real hydration energies of ions. Trans. Faraday Soc. 52:1573–1581. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, H., and A. Heller. 1985. The absolute potential of the standard hydrogen electrode: a new estimate. J. Phys. Chem. 89:4207–4213. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, B., and M. Karplus. 1995. Potential energy function for cation-peptide interactions: an ab initio study. J. Comput. Chem. 16:690–704. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, B., and R. MacKinnon. 1999. The cavity and pore helices in the KcsA K+ channel: electrostatic stabilization of monovalent cations. Science. 285:100–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux, B., H.-A. Yu, and M. Karplus. 1990. Molecular basis for the Born model of ion solvation. J. Phys. Chem. 94:4683–4688. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz, C. N., and A. Warshel. 2001. What are the dielectric “constants” of proteins and how to validate electrostatic models. Proteins. 44:400–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry, H. S. 2003. Ion exchange. In Handbook of Zeolite Science and Technology, S. M. Auerbach, K. A. Carrado, and P. K. Dutta, editors. Marcel Dekker, New York. In press.

- Shrivastava, I. H., and M. S. P. Sansom. 2000. Simulations of ion permeation through a potassium channel: molecular dynamics of KcsA in a phospholipid bilayer. Biophys. J. 78:557–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, I. H., D. P. Tieleman, P. C. Biggin, and M. S. P. Sansom. 2002. K+ versus Na+ ions in a K channel selectivity filter: a simulational study. Biophys. J. 83:633–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui, H., B. G. Han, J. K. Lee, P. Walian, and B. K. Jap. 2002. Structural basis of water-specific transport through AQP1 water channel. Nature. 414:872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawa, G. J., I. A. Topol, S. K. Burt, R. A. Caldwell, and A. A. Rashin. 1998. Calculation of the aqueous solvation free energy of the proton. J. Chem. Phys. 109:4852–4863. [Google Scholar]

- Tembe, B. L., and J. A. McCammon. 1984. Ligand-receptor interactions. Comput. Chem. 8:281–283. [Google Scholar]

- Tissandier, M. D., K. A. Cowan, W. Y. Feng, E. Gundlach, M. H. Cohen, A. D. Earhart, J. V. Coe, and T. R. Tuttle. 1998. The proton's absolute enthalpy and Gibbs free energy of solvation from cluster-ion solvation data. J. Phys. Chem. A. 102:7787–7794. [Google Scholar]

- Warshel, A., and A. Papazyan. 1998. Electrostatic effects in macromolecules: fundamental concepts and practical modeling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8:211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellen, G. 1984a. Ionic permeation and blockade in Ca2+ activated K+ channels of bovine chromaffin cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 84:157–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellen, G. 1984b. Relief of Na+ block of Ca2+-activated K+ channels by external cations. J. Gen. Physiol. 84:187–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]