Abstract

The model of myosin regulation by a continuous tropomyosin chain is generalized to a chain of tropomyosin-troponin units. Myosin binding to regulated actin is cooperative and initially inhibited by the chain as before. In the absence of calcium, myosin is further inhibited by the binding of troponin-I to actin, which through the whole of troponin pins the tropomyosin chain in a blocking position; myosin and TnI compete for actin and induce oppositely-directed chain kinks. The model predicts equilibrium binding curves for myosin-S1 and TnI as a function of their first-order affinities KS1 and LTI. Myosin is detached by the actin binding of TnI, but TnI is more efficiently detached by myosin when the kink size (typically nine to ten actin sites) spans the seven-site spacing between adjacent TnI molecules. An allosteric mechanism is used for coupling the detachment of TnI to calcium binding by TnC. With thermally activated TnI kinks (kink energy B ≈ kBT), TnI also binds cooperatively to actin, producing cooperative detachment of myosin and biphasic myosin-calcium Hill plots, with Hill coefficients of 2 at high calcium and 4–6 at low calcium as observed in striated muscle. The theory also predicts the cooperative effects observed in the calcium loading of TnC.

INTRODUCTION

In the previous article (I), a mathematical model for the regulatory action of tropomyosin as a continuous flexible chain on the actin filament was developed and applied to myosin binding data for actin-tropomyosin systems. In this article the model is generalized for myosin regulation by the thin filament of striated muscle, whose tropomyosin chain carries one troponin molecule for each 40-nm-long tropomyosin unit. In the absence of calcium, the inhibitory action of the chain is increased because TnI, the inhibitory component of troponin, and hence the whole troponin, is bound to actin. Consequently, the activation of muscle contraction by calcium is due to the release of troponin from actin (Ebashi, 1977, Grabarek et al., 1992, Herzberg et al., 1986). Fig. 1 depicts the disposition of tropomyosin and the three components of troponin on the thin filament with and without calcium.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic structure of the regulated actin tropomyosin-troponin (A-Tm-Tn) filament, showing a single chain of tropomyosin (Tm) molecules on one strand of the actin double helix. TnT is bound to one end of Tm and its N-terminus overlaps the adjacent tropomyosin. The C-terminus of TnC and the N-terminal of TnI are bound to TnT. (A) In the absence of calcium, the hands of the N-terminal region of TnC are shut and the C-terminal of TnI is bound to actin and blocks myosin binding to that site. (B) When two calcium ions are bound to TnC, the hands of the N-terminal region are open and bind a region of TnI near its C-terminus, so that the myosin binding site is regulated only by tropomyosin. Based on models of Gagne et al. (1995) and Tripet et al. (1997).

The required generalization of the model is to a Tm·Tn chain where molecules of myosin and TnI (on the chain) are both in reaction-equilibrium with actin, pinning the chain at positive and negative angles respectively when bound. The equilibrium statistical mechanics of this chain is developed as a function of the actin affinities KS1, LTI of myosin and enchained TnI. Activation of myosin-actin interaction by calcium is recovered when LTI ≪ 1, duplicating the results of the previous article. If LTI ≫ 1, inhibition at low calcium occurs by the binding of enchained TnI molecules to actin, pinning the chain near the outer actin domain (a local blocked state), whereas strong myosin binding pushes the chain toward the inner domain (a local open state). The resting position of the chain, which is the mean configuration of the closed state, is assumed to lie somewhere in between. The validity of this interpretation of the structural evidence, rather than the existence of three discrete orientational states of the filament, has been discussed in I. Dynamic TnI-actin equilibrium would allow a few molecules of TnI to be detached from actin even at low calcium; these TnI molecules would let the chain revert to a local closed state from which the first myosin could bind under an additional fluctuation (Fig. 2, A1 and A2).

FIGURE 2.

The continuous tropomyosin-troponin chain, with troponins bound to the chain at intervals of 38 nm (approximately seven actin sites). All diagrams represent states in the absence of calcium. (A1) In the absence of myosin, most molecules of TnI are bound to actin, locally pinning the chain at a negative angle φ− which blocks myosin binding. (A2) The first myosin to bind requires a chain fluctuation allowed by detached TnI molecules or an extreme fluctuation between bound TnI molecules. (A3) At higher myosin density, TnI molecules are detached when the distortion energy of the chain overcomes their binding energy and the chain is forced toward open configurations (φ > φ+). Under these conditions, additional myosin binding is not locally inhibited by the chain. (B) Cross-sections of the actin filament and tropomyosin chain (•), showing (B1) the TnI binding interface, where bound TnI hangs off the chain at more negative angles (Lehman et al., 2001; Narita et al., 2001) and (B2) the interface for strong myosin binding. The two interfaces overlap so myosin and TnI compete for their binding sites.

The generalized CFC model generates indirect pair interactions between proteins that bind to the regulated actin filament, if their actin affinity is affected by the local orientation of the tropomyosin chain. A local distortion in chain position produced by one bound protein is transmitted over a distance of the order of the chain persistence length and modifies the affinity of neighboring actin sites for a second protein. For two proteins of the same kind, the free energy of chain distortion decreases as the distance between binding sites is reduced, giving an attractive interaction (positive cooperativity). For two different proteins which induce oppositely-directed chain kinks, the distortion energy rises as their kinks are merged, lowering the affinity of whichever protein bound later (repulsive interaction, negative cooperativity). In this model, the actin-binding proteins are myosin and enchained TnI, giving three distinct types of indirect pair interaction via the chain:

M-M

Myosin-myosin interaction, from the overlap between positive chain kinks produced by bound myosins (I), which promote local open states of the chain.

M-I

Myosin-TnI interaction, negatively cooperative as above if actin-bound TnI generates a negative chain kink of any size (including zero). Bindings of myosin and enchained-TnI alter the balance of locally blocked and open states of the chain, which is weighted in favor of myosin as enchained TnI's access only every seventh actin monomer.

I-I

TnI-TnI interaction, from overlap between chain kinks produced by actin-bound TnI's on the chain, promoting local blocked states. Overlapping kinks require a chain persistence length of at least half the seven-site troponin spacing.

Note that although we refer throughout to the interaction between TnI and actin, the value of LTI and the strength of I-I interactions in particular will be functions of the properties of the whole troponin molecule.

These pair interactions are the molecular basis for cooperative phenomena generated by an ensemble of myosins and troponins on regulated actin, which could be described as cooperativity of type M-M (+ve), type M-I (−ve), or type I-I (+ve) respectively, when only one type of pair interaction is operating. Because these interactions can operate in combination, we will avoid using the same terminology to describe the resulting cooperative effects. The reader is invited to consider the energetics of combined interactions such as tertiary TnI interactions via an intervening myosin.

Because our model requires a continuous tropomyosin chain, the mechanism for calcium regulation of myosin binding is necessarily different to that of Hill, Eisenberg, and Greene (1980), where the calcium states of TnC regulated the end-to-end interactions of individual tropomyosins. This difference is reflected in the predictions of the models. We assume that calcium regulation is achieved by the well-known allosteric mechanism (Herzberg et al., 1986; McKay et al., 2000) where the binding of Ca to TnC downregulates the actin-binding of TnI. We use a simplified version of this mechanism (Fig. 1, Appendix) in which the distal part of enchained TnI is either captured by the distal end of TnC (the in state of TnC, favored at high calcium) or bound to actin (the out state of TnC, favored at low calcium). Allosteric modifications of TnC are required for continuous modulation of actin-TnI affinity LTI with calcium concentration; details are given in the Appendix. For skeletal TnC, two bound calcium ions are required to favor the in state, and the allosteric transition within each molecule of TnC is also cooperative, with a Hill coefficient of between one and two for calcium binding (Potter and Gergely, 1975). For cardiac TnC, one calcium ion is thought to be sufficient.

With these mechanisms incorporated in the chain model, its predictions can be applied to the calcium regulation of myosin binding in solution. The relevant experiments are primarily titrations of myosin binding to regulated actin as a function of myosin and calcium concentrations. Unfortunately the latter are generally not available as solution data, and one is forced to rely on measurements of the calcium dependence of isometric force in striated muscle, which can be argued to be analogous. There is apparently no published data for the bound fraction of enchained TnI as a function of calcium. Evidence for the three types of cooperativity is as follows.

Equilibrium myosin binding curves to fully-regulated actin (actin-Tm·Tn) as a function of myosin concentration show M-M cooperativity at high calcium as described in I. At low calcium this cooperativity is more apparent, but in fact the degree of cooperativity (the Hill coefficient or the quantity S* defined in I) may be no greater than at high calcium. Rather, myosin binding is inhibited by M-I interactions proceeding from blocked states generated by the actin-binding of enchained TnI molecules, raising the switching myosin concentration defined by the point of inflection so that the concave behavior of the binding curve at low myosin concentration is evident. This inhibition is completely overcome at high concentrations, when myosin overrides TnI and pushes the chain toward the open state through its sevenfold advantage in binding sites.

Myosin binding as a function of calcium concentration can be judged from classic measurements of isometric tension in muscle fibers, consistent with competitive myosin-TnI interactions with TnI allosterically coupled to calcium. However, the observed degree of cooperativity is not as for binding with respect to myosin concentration; measured values of the Hill coefficient range from 2 to 7, according to method and conditions (Gordon et al., 2000). A value not greater than 2 is expected if tropomyosin-troponin units switch independently according to whether or not two calcium ions are bound to TnC. In the context of the chain model, higher myosin-calcium cooperativity must be due to TnI-TnI cooperativity, with allosteric coupling between the actin-binding of each TnI and calcium binding to the associated TnC. This cooperativity could be due to I-I pair interactions, which operate in the absence of myosin, or a combination of M-I interactions via one or more bound myosins (the reader may verify that this mechanism produces cooperative detachment of TnI molecules). However, the true situation seems more complicated. In rabbit psoas muscle, Moss et al. (1983) find a biphasic force-calcium Hill plot with slopes of 6.7 for pCa > 6.5 and 2.0 for pCa < 6.5, but only at full filament overlap, while at partial overlap there is a single Hill coefficient close to two. Solution measurements of the initial rate of myosin binding to fully-regulated actin as a function of calcium (Head et al., 1995) yields a Hill coefficient of 1.8; this number applies to the myosin-free filament and therefore argues against the existence of I-I interactions.

Clear evidence for I-I interactions is available from calcium-binding studies of TnC in isolated troponin and on fully regulated actin in the absence of myosin. Grabarek et al. (1983) have shown that the calcium load of TnC rises more rapidly with free calcium (an increase in the cooperativity of calcium binding) when the troponins are bound to tropomyosin on F-actin. For this system, a drop in free calcium level at one troponin causes its TnI component to bind more strongly to actin: as the chain adopts a local blocking position (Fig. 2), this event is transmitted to neighboring molecules of TnI, which in turn decreases the calcium affinity of the corresponding molecules of TnC, giving calcium-to-calcium cooperativity.

The increase in the cooperativity of the TnC-calcium-loading curve with added myosin (Bremel and Weber, 1972; Grabarek et al., 1983) is further evidence for M-I interactions. The above discussion shows that this mechanism can operate in the absence of I-I interactions.

The predictions of the generalized chain model developed in this article accommodate all these observations if I-I interactions are present in some experimental systems but not in others. In the concluding section we assess the degree of cooperativity to be expected in different measurements from the three types of pair interactions acting in combination with each other and with the allosteric mechanism coupling TnI to calcium.

REGULATION BY A TROPOMYOSIN-TROPONIN CHAIN

The model described in I describes myosin binding to actin-Tm, and to actin-Tm-Tn at millimolar concentrations of Ca2+. At micromolar calcium or below, most molecules of TnI are bound to actin, which increases the inhibition of myosin binding by the chain. The following assumption, in addition to those made in I for myosin binding, is required: At low calcium, each bound TnI pins the chain at angle φ− < 0, creating a negative kink of energy

|

(1) |

to further inhibit myosin binding to sites within one persistence length (Fig. 2 B1).

Let LTI be the actin affinity of TnI on the chain in the absence of chain distortion. When TnI is part of the troponin complex (Fig. 1), LTI will be interpreted as a first-order equilibrium constant for the transfer of TnI from TnC to actin, which is a decreasing function of the free calcium level. A solitary TnI on the chain would need to bind under a thermally created kink to angle φ−, with affinity L where

|

(2) |

However, at low calcium all TnI molecules on the chain will bind to actin if L > 1, and the affinity of late-binding TnI molecules will increase toward LTI if kinks between adjacent TnI molecules overlap (Fig. 2 A1). As the TnI spacing is approximately seven actin monomers, the cooperative effects of this overlap cannot be as great as for myosin binding. Myosin binding at low calcium is grossly inhibited by the multiply pinned chain, which must make a thermal fluctuation from negative angles near φ− to positive angles above φ+; the bending energy associated with this fluctuation is prohibitively large for sites within one persistence length on each side (Fig. 2 A3). With myosins bound, the energy cost of positive and negative kinks in proximity forces many TnI molecules to detach (Fig. 2, A2 and A3) even at low calcium.

The inhibitory effect of TnI requires that LTI > 1, but if TnI binding is not cooperative, the stronger condition L > 1 is required.

The energy of a pair of chain kinks depends on whether the kinks are produced by bound myosin or bound TnI. For two kinks with angles φ1, φ2, and separation ξx, the distortion energy of the chain is

|

in terms of the functions ΓS(x), ΓA(x) defined in Smith (2001). Hence the distortion energies of myosin-myosin, TnI-TnI, and myosin-TnI kink pairs are respectively

|

(3a) |

|

(3b) |

in terms of single-kink energies A and B, assuming that  As x → 0 the kinks merge, and ΓS(0) = 1 for kinks of the same kind whereas ΓA(x) diverges to infinity as opposing kinks are pushed together. For x ≫ 1, the kinks are completely separated and

As x → 0 the kinks merge, and ΓS(0) = 1 for kinks of the same kind whereas ΓA(x) diverges to infinity as opposing kinks are pushed together. For x ≫ 1, the kinks are completely separated and  so the pair energy is the sum of the energies of each kink in isolation.

so the pair energy is the sum of the energies of each kink in isolation.

MYOSIN BINDING TO ACTIN-TROPOMYOSIN-TROPONIN

When actin-myosin interactions are regulated by the tropomyosin-troponin complex, the model must be extended to allow molecules of troponin-I to bind to actin, as described in the preceding section. Actin-myosin, actin-TnI, and Ca-TnC interactions are assumed to be in rapid equilibrium; the time scales of these equilibria (1–10 ms) can be inferred from solution kinetics and the rise of muscle tension after activation by calcium. The extra parameters needed to describe the binding of TnI to actin are its affinity LTI and the energy B of the associated (negative) chain kink.

Theory

The free energy of the pinned chain now depends on the positions of bound molecules of myosin and TnI. TnI is assumed to compete with myosin for every seventh actin monomer on a given strand of the helix. Suppose that p molecules are bound to monomers at positions  Their identity is specified by tags

Their identity is specified by tags  which take values +1 for myosin and −1 for TnI, where the latter is permitted only on every seventh site. These integers determine the numbers n and m of bound myosins and TnI's, where n + m = p. With this formalism, the partition function for an N-site filament can be written as

which take values +1 for myosin and −1 for TnI, where the latter is permitted only on every seventh site. These integers determine the numbers n and m of bound myosins and TnI's, where n + m = p. With this formalism, the partition function for an N-site filament can be written as

|

(4) |

where xnm and σnm are vectors of reduced spacings and identity tags, respectively.

As before, we approximate the chain free energy by a sum of pair energies, but the form of the pair energy  now depends on the identities

now depends on the identities  of the bound molecules. Pair potentials for localized myosin-myosin, TnI-TnI, and myosin-TnI interactions via the chain should be defined as

of the bound molecules. Pair potentials for localized myosin-myosin, TnI-TnI, and myosin-TnI interactions via the chain should be defined as

|

(5a) |

|

(5b) |

|

(5c) |

Specific functional forms are available from Eq. 3, in which entropic components are neglected. All potentials tend to zero for x ≫1. At x = 0, the homo-pair potentials (5a,b) have values −A and −B respectively, while the hetero-pair potential (5c) diverges to +∞.

The transfer-matrix method for the partition function can proceed as follows. To keep track of TnI-binding sites, let ZMk be the partition function for a regulated actin filament of 7M + k monomers, where M is a non-negative integer, k = 1,…,7, and only sites with k = 1 can bind TnI molecules on the chain (Fig. 3). It is convenient to fix the range r of interactions at seven, the number of actin monomers between adjacent troponins. With this approximation, TnI-TnI interactions via the chain are restricted to nearest-neighbors, and ν ≤ 3.5 should be observed to avoid excessive truncation of the interaction potentials.

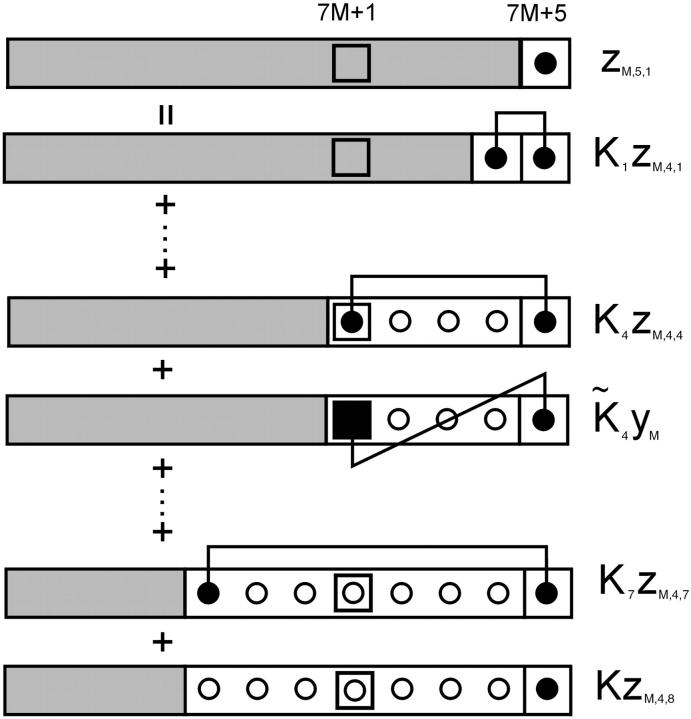

FIGURE 3.

Diagram illustrating Eq. 7a for components of the myosin-troponin transfer matrix ZMk with 7M + k myosin binding sites for k = 5. Every seventh myosin binding site (□) is positioned to bind TnI also. The component  , in which the last site is occupied by myosin, can be expressed in terms of

, in which the last site is occupied by myosin, can be expressed in terms of  for j = 1,…,8 as in I, plus a term where TnI is bound to site 7M + 1 and interacts with the leading myosin through the factor

for j = 1,…,8 as in I, plus a term where TnI is bound to site 7M + 1 and interacts with the leading myosin through the factor  The factor yM is the component of ZMk with site 7M + 1 occupied by TnI and unoccupied sites in front (Eq. 7d; diagram not shown).

The factor yM is the component of ZMk with site 7M + 1 occupied by TnI and unoccupied sites in front (Eq. 7d; diagram not shown).

Following Fig. 3, we define constrained partition functions zMk1 as before, with the leading site occupied by myosin, zMk2 with the leading site empty and the site behind occupied by myosin, up to zMk7 with myosin in the seventh site from the front. zMk8 is defined as before with all seven leading sites empty. We also need a partition function yM with the leading k − 1 sites empty and TnI bound to the kth site back, which is indexed as 7M + 1 and can bind TnI as well as myosin. If k > 1, the k − 1 leading sites cannot bind TnI, so this partition function is independent of k. Then

|

(6) |

It will be sufficient to calculate ZM1, the partition function for a chain with troponins at each end.

Adding one site to the front gives the recursions

|

(7a) |

|

(7b) |

|

(7c) |

for k = 1,…,6, plus

|

(7d) |

where

|

(8) |

Using the 8 × 8 transfer matrix T introduced in I, the vector form of these equations is

|

(9a) |

|

(9b) |

where  for k = 1,…,7 and

for k = 1,…,7 and  are eight-dimensional vectors. For matrix multiplication, vectors without superscript are treated as columns and vectors with the T superscript as rows.

are eight-dimensional vectors. For matrix multiplication, vectors without superscript are treated as columns and vectors with the T superscript as rows.

Equation 9a can be solved recursively for zM2,…,zM7 in terms of zM1 and yM. This information enables a recursive solution from one troponin site to the next, in the form

|

(10) |

where

|

(11) |

As in I, it can be shown that the partition function in the limit of large M is proportional to ΛmM where Λm is the highest eigenvalue of the 9 × 9 matrix in Eq. 10. In this limit, the bound fractions θ and ρ for myosin and troponin-I respectively are

|

(12ab) |

The eigenvalues of this 9 × 9 matrix can be obtained in terms of the eigenfunctions of T, which can be computed efficiently. The matrix T7 in the upper 8 × 8 block is diagonalized by the similarity transform  of I, so that the required eigenvalues are preserved by the similarity transformation

of I, so that the required eigenvalues are preserved by the similarity transformation

|

(13) |

For eigenvalue Λ with eigenvector (x,y), the eigenequations are

|

|

Thus the eigenvalues satisfy

|

(14) |

where λα are the eigenvalues of T,  , and Pα is an 8 × 8 projector matrix, with an element of unity at the αth diagonal entry and zeros elsewhere.

, and Pα is an 8 × 8 projector matrix, with an element of unity at the αth diagonal entry and zeros elsewhere.

For numerical computation, Eq. 14 can be solved iteratively for the highest eigenvalue, starting from an approximation which retains only the term with the highest eigenvalue λm in the sum. The initial estimate is

|

(15) |

Care must be taken to avoid ill-conditioned numerical results as various limiting situations are approached. When TnI binding is switched off, t = Cα = 0 and Eq. 14 is indeterminate, although the above initial estimate is then exact. Nevertheless, Eq. 14 can give convergent numerical solutions for LTI ≥ 10−4. As mentioned earlier, the calculation is invalid when A = 0, but computed results are well-behaved if βA ≥ 10−3.

For the myosin binding fraction θ, the required derivative dΛm/dK should be calculated numerically rather than from a derived analytic expression. For TnI binding, a simple closed formula for dΛm/dL can be derived, giving the expression

|

(16) |

for the bound TnI fraction ρ. Note that these results are not defined in the absence of myosin, when T has zeros in the top row. The problem of TnI binding in the absence of myosin is mathematically equivalent to myosin binding in the absence of troponin, except that the spacing between binding sites is sevenfold greater.

Finally, note the existence of the Maxwell relation

|

(17) |

which follows from Eq. 12 and is independent of the model. It is useful in comparing the cross sensitivities of myosin binding to TnI and vice versa, here defined as the logarithmic derivatives

|

(18) |

respectively. Standard manipulations then give the model-independent identity

|

(19) |

Numerical predictions

The model predicts the fractions of myosin and TnI bound to actin as a function of their first-order affinities KS1 (proportional to [S1]) and LTI, which is controlled by calcium bound to TnC. The upper row in Fig. 4 shows these functions for fixed values of the kink energies and persistence number, namely βA = 1.5, βB = 0.01, and ν = 3.0. As before, myosin binding is cooperative (Fig. 4 A), and switches from a low affinity form  with η < 1 at low KS1 to the high affinity form

with η < 1 at low KS1 to the high affinity form  at high KS1. The factor η reflects increased inhibition by TnI, and decreases as TnI binds more strongly (Fig. 4, A and B). Similarly, the switching affinity K* (the value of KS1 at the point of inflection) increases with the strength of TnI binding. Nevertheless, when myosin binds strongly (say KS1 > 2), that binding is not inhibited by TnI. Similarly, the binding of TnI (Fig. 4, C and D) is inhibited by bound myosin, but less so at high LTI.

at high KS1. The factor η reflects increased inhibition by TnI, and decreases as TnI binds more strongly (Fig. 4, A and B). Similarly, the switching affinity K* (the value of KS1 at the point of inflection) increases with the strength of TnI binding. Nevertheless, when myosin binds strongly (say KS1 > 2), that binding is not inhibited by TnI. Similarly, the binding of TnI (Fig. 4, C and D) is inhibited by bound myosin, but less so at high LTI.

FIGURE 4.

The fractional occupancies θ, ρ of actin sites by myosin-S1 and troponin-I as functions of their affinities KS1 and LTI, predicted for the tropomyosin-troponin chain using A = 1.5 kBT and ν = 3. The TnI kink energy B is set to zero in A–D and to kBT in E–F. The bound TnI fraction refers to every seventh actin site, for which myosin and TnI compete.

In other respects, the binding characteristics of myosin and TnI are quite different. Switching behavior in the TnI binding curves of Fig. 4 D is not present because we used a very small TnI kink energy B. The inhibitory effect of myosin on TnI binding is very potent; the figure shows that a tenfold increase in myosin affinity reduces the apparent actin affinity of TnI by a factor of 300. For this reason, the TnI binding curves for different myosin affinities reach a common asymptote only at exceptionally high values of LTI. The inhibitory effect of TnI on myosin binding is much less dramatic. Fig. 4 A shows that TnI must bind very strongly to actin to displace bound myosins; a tenfold increase in LTI from 30 to 300 increases the myosin switching affinity K* only by a factor of 1.6. These differences arise from the sevenfold ratio of TnI and actin site spacings when ν = 3, and are confirmed by the ratio of cross sensitivities. At KS1 = 1 and LTI = 30,  and

and  , so

, so  from Eq. 19. Furthermore, Eq. 17 can be checked numerically. At the same point, Fig. 4, B and C gives

from Eq. 19. Furthermore, Eq. 17 can be checked numerically. At the same point, Fig. 4, B and C gives  and

and

The lower row of Fig. 4 shows the effects of requiring a negatively kinked chain for TnI binding, with βB =1.0. The value of LTI must be increased by a factor of order exp(βB) = 2.7 to achieve the same bound fraction of TnI. If this were the only effect of introducing negative TnI kinks, the lower graphs could be derived from their upper counterparts by rescaling LTI, so that binding curves are determined by TnI affinity  under the chain and not by LTI and B separately. This approximation would be correct if TnI-induced kinks do not overlap. The extent of any overlapping regions will increase with LTI and the bound fraction of troponin-I, allowing TnI to bind cooperatively at high LTI. The TnI binding curves in Fig. 4 H switch from a chain-inhibited form

under the chain and not by LTI and B separately. This approximation would be correct if TnI-induced kinks do not overlap. The extent of any overlapping regions will increase with LTI and the bound fraction of troponin-I, allowing TnI to bind cooperatively at high LTI. The TnI binding curves in Fig. 4 H switch from a chain-inhibited form  where ζ < 1 at low LTI to an uninhibited form ≈ LTI/(1+LTI) at high LTI, but only in the presence of bound myosin. This behavior is not observed in the absence of myosin, because the switching affinity L* (the value of LTI at the point of inflection) drops rapidly toward zero as KS1 → 0. If the persistence number ν is increased, L* and the width of the switching region in LTI both decrease. L* also goes to zero as B → 0.

where ζ < 1 at low LTI to an uninhibited form ≈ LTI/(1+LTI) at high LTI, but only in the presence of bound myosin. This behavior is not observed in the absence of myosin, because the switching affinity L* (the value of LTI at the point of inflection) drops rapidly toward zero as KS1 → 0. If the persistence number ν is increased, L* and the width of the switching region in LTI both decrease. L* also goes to zero as B → 0.

Differences between the myosin binding curves of Fig. 4, E and A can also be explained in terms of the cooperative binding of TnI when B > 0 (Fig. 4 E). Apart from the required scaling of LTI to higher values, binding curves in the two figures with the same switching value K* have a higher slope when B > 0. This effect is also due to bound myosin increasing the switching affinity L* of TnI, which can push TnI out of the cooperative binding region (LTI > L*) for a given value of LTI. Hence TnI binding is inhibited by added myosin sooner than in the absence of TnI-based cooperativity (Fig. 4, G and C). The result is an increase in the apparent cooperativity of myosin binding, measured by the slope of the binding curve at its point of inflection.

Varying the myosin kink energy A produces effects similar to those found in the absence of bound TnI, described in I.

All computations were made in Fortran. Complex roots of the secular Eq. 14 were found by Laguerre's method, implemented by subroutines zroots and laguer (Press et al., 1992). All eigenvectors of T were checked for orthogonality and completeness, achieved to one part in 106 at worst with single-precision arithmetic but generally to machine accuracy. These programs were checked in limiting cases where one protein is absent. When LTI ≤ 0.01, myosin binding curves approach those predicted in the absence of troponin (η = 1). Similarly, ζ = 1 for the TnI binding curve when KS1 ≤ 10−3.

As presented, the theory applies to native tropomyosin-troponin where troponins are separated by seven actin site spacings. Engineered Tm-Tn chains with shortened tropomyosins can be accommodated by changing the value of r to match the troponin spacing.

EXPERIMENTAL TESTS

The predictions of the last section can be tested against myosin binding data for actin-Tm-Tn filaments with and without calcium, myosin binding as a function of calcium at various myosin affinities and TnC binding data as a function of calcium level. Binding data for myosin in solution is required, but is available only at the ends of the calcium range. Qualitatively analogous measurements, of the calcium dependence of isometric force in the muscle fiber, are available. However, the CFC model as developed here is not strictly applicable to myosin binding in the muscle fiber, as explained in the Discussion section.

Skeletal actin-Tm-Tn

Myosin-S1 binding curves of Maytum et al. (1999) to actin-Tm-Tn±Ca can be fitted to the generalized chain model, as shown in Fig. 5 and Table 1. The +Ca data is well-fitted by using a very small TnI affinity LTI; in this limit the precise values of LTI and the TnI kink energy B do not matter. Optimum values of the other parameters  , A, and ν which appear in I were as reported earlier.

, A, and ν which appear in I were as reported earlier.

FIGURE 5.

Experimental myosin binding curves versus free S1 concentration for regulated actin systems from skeletal muscle (Maytum et al., 1999), and curves of best-fit to the CFC model for the tropomyosin-troponin chain. The fitted parameters are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

| Filament | Version |

(M−1) (M−1) |

βA | ν | LTI | βB | χ2/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TmTn+Ca | I | 1.7 × 107 | 1.6 | 3.7 ± 0.1 (3.9) | 0.12 | ||

| TmTn+Ca | II | 1.7 × 107 | 1.6 | 3.5 ± 0.1 (4.0) | 0.01* | 0.1* | 0.10 |

| TmTn−Ca | II | 2.0 × 107 | 0.90 | 3.6* | 51 ± 3 | 0.01* | 0.16 |

Parameters for the myosin binding curves of Fig. 5 for skeletal actin-Tm-Tn, from least-squares fitting to versions I (preceding article) or II (this article) of the CFC model, and chi-squared per data point. As before, bracketed values were obtained by weighted fitting in favor of low S1 concentrations. Starred values were held constant in the fitting procedure. The effects of using different constraints for fitting the −Ca data are described in the main text.

The −Ca data cannot be fitted uniquely by unconstrained variation of all five parameters. The maximum slope is no greater than in the presence of calcium, suggesting no Ca-induced change in the Hill coefficient. Comparisons with Fig. 4, A and E therefore suggest that B is much smaller than thermal energy (βB ≪ 1). An acceptable fit can be obtained by constraining ν = 3.6 as found with calcium to give LTI = 50, but myosin kink energy A is lowered to 0.89 kBT. If the value of LTI is constrained instead, the optimum value of ν depends on LTI and reaches 3.6 when LTI = 80. It appears that the myosin binding curve does not contain enough information to give a unique fit when more than three parameters are varied. Hence we conclude that variations in the values of A and ν from fits with different values of LTI are not significant. Our preferred fit to the –Ca data is with ν = 3.6, since there are no compelling grounds for supposing that the persistence length of the chain would vary with calcium level. However, a calcium-induced shift in kink energy A could still arise if the resting orientation of the chain, from which the kink angle φ+ is measured, is influenced by the calcium-dependent electrostatic environment of troponin-C.

The hypothesis that the kink size 2ν + 1 = 8.4 of skeletal A-Tm-Tn filaments is structurally determined, and therefore calcium-independent, may appear to conflict with calcium-dependent unit sizes obtained previously by fitting the same data to the McKillop-Geeves model (11 at +Ca, 6 at −Ca). As discussed in I, this unit size can be interpreted as the correlation length of the chain in the context of CFC models. When calcium is removed, a correlation length of seven monomers is expected if the chain is pinned to actin by all molecules of TnI; in this situation, myosin kinks produced at high myosin concentration would not be able to grow beyond the seven-site TnI spacing even when the intrinsic kink size is greater than seven.

Calcium regulation of myosin binding

The calcium dependence of myosin binding to the fully-regulated actin filament can be predicted if the actin affinity of TnI is a known function of the free calcium level C. The binding of TnI to actin is downregulated by the binding of two molecules of Ca2+ to TnC, which has the effect of transferring the corresponding molecule of TnI from actin to TnC (Fig. 1). If this process proceeds by an allosteric mechanism, LTI is a decreasing function of C, approximately quadratic over a range of concentrations (Appendix).

The Hill plots for myosin bound fraction derived from Fig. 4, B and F can now be presented as a function of calcium level. For convenience, we assume a strict quadratic law so that  When B = 0 (Fig. 6 A), the myosin-calcium Hill plots are straight lines with a slope of 2.2, independent of myosin affinity. With cooperative binding of TnI (βB = 1.0, Fig. 6 B), these plots are generally biphasic, with a slope ∼2.2 at high calcium but slopes of four to six at low calcium, the latter slope increasing with myosin affinity KS1. These predictions mirror the asymmetric force-calcium relationship seen by Moss et al. (1983) in the muscle fiber, suggesting a model in which TnI binds cooperatively to actin below the point of inflection

When B = 0 (Fig. 6 A), the myosin-calcium Hill plots are straight lines with a slope of 2.2, independent of myosin affinity. With cooperative binding of TnI (βB = 1.0, Fig. 6 B), these plots are generally biphasic, with a slope ∼2.2 at high calcium but slopes of four to six at low calcium, the latter slope increasing with myosin affinity KS1. These predictions mirror the asymmetric force-calcium relationship seen by Moss et al. (1983) in the muscle fiber, suggesting a model in which TnI binds cooperatively to actin below the point of inflection  ,

,  , where its affinity is high.

, where its affinity is high.

FIGURE 6.

Hill plots for myosin bound fraction θ versus free calcium level C. (A) from Fig. 4 A (B = 0), with slopes near unity and (B) from Fig. 4 F (B = 1.5 kBT), showing biphasic behavior. Abscissas were converted using the equation logLTI(C) = −12.3−2 log C. The flat region of plots in (A) at low calcium reflect residual myosin binding. To avoid computational singularity, θmax was set at 1.001.

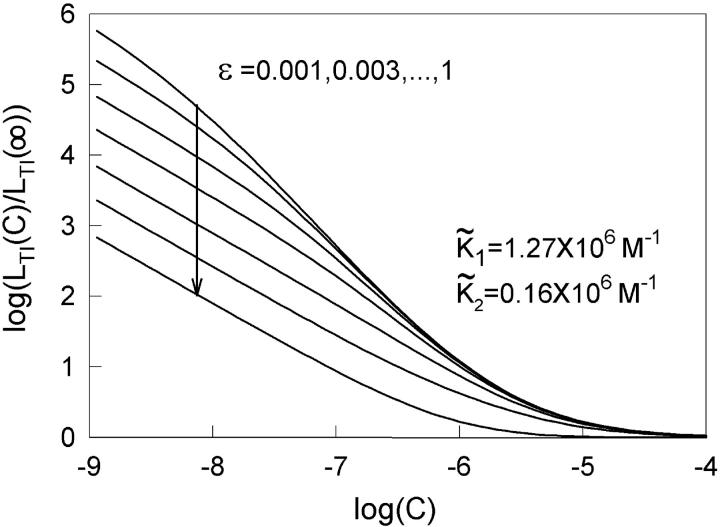

Allosteric models can only produce a quadratic relationship between LTI and calcium level when TnC is not saturated by calcium. This effect is seen in the log-log plot of Fig. 7, where the slope falls from 1.9 below 1 μM calcium to zero above 100 μM. This drop in slope can also generate a biphasic myosin-calcium Hill plot, but not with Hill coefficients above 2.0 at low calcium. As the calcium level is raised, myosin binding may well saturate before TnC saturates with calcium, in which case the first explanation remains valid. The slope in Fig. 7 also drops at calcium levels below 10 nM, where the allosteric mechanism fails but myosin activation is negligible.

FIGURE 7.

Calcium dependence of the transfer affinity LTI(C) of TnI from TnC to actin, as predicted from Eq. A1 for λ = 10, ɛo = 0, and various values of ɛ. Values of the calcium-binding affinities  to TnC are as reported by McKay et al. (2000).

to TnC are as reported by McKay et al. (2000).

The calcium content of troponin-C

If calcium control of actin-myosin interactions operates by modulating the binding strength of TnI to actin as described above, the bound calcium content of troponin-C will be reflected in the fraction of troponin-I's bound to troponin-C. As bound TnI can be displaced by myosin binding, it follows that mechanical interventions in the muscle fiber which increase the number of bound myosins should displace TnI molecules from actin to TnC and shift the allosteric equilibrium of TnC from the out form to the in form (Fig. 1). As the open form requires at least one if not two calcium ions bound to TnC, a mechanical intervention of this kind should increase the calcium content of troponin-C. Interventions which decrease the bound myosin fraction should have the opposite effect. Such effects have often been observed, for example by Bremel and Weber (1972), Allen and Kurihara (1982), Grabarek et al. (1983), and Güth and Potter (1987).

The chain model predicts that an increase in bound myosin reduces the bound TnI fraction ρ. This effect will lead to myosin-induced changes in TnC if coupled to the allosteric scheme of the Appendix, where 1–ρ is the fraction of TnI's bound to TnC. The reaction scheme in this appendix can be grafted onto the present model by assuming that the different calcium states of TnC, for in and out states respectively, are equilibrated by constructing partial partition sums before summing over site occupancies by myosin and TnI in Eq. 4. However, equilibrium between in and out states is modified by chain distortion and cannot be enforced at the level of a single TnC before evaluating the whole partition function. Thus the mean number of calciums bound to TnC is

|

(20) |

in which  is a decreasing function of ρ for all ɛo,ɛ in the range (0,1).

is a decreasing function of ρ for all ɛo,ɛ in the range (0,1).

Predictions for  as a function of calcium level are shown in Fig. 8, using Eq. A1 for the calcium-dependent affinity LTI(C) of TnI to actin. The calcium binding curve for isolated troponin-C is obtained by setting

as a function of calcium level are shown in Fig. 8, using Eq. A1 for the calcium-dependent affinity LTI(C) of TnI to actin. The calcium binding curve for isolated troponin-C is obtained by setting  which equilibrates the binding of free TnI to TnC; in this case the quantity λ in Eq. A1 is the (first-order) binding constant of TnI to Ca2TnC. For troponins on tropomyosin in the regulated actin filament, ρ is a property of the whole filament and is predicted by the CFC model as a function of LTI and KS1 (Fig. 4). These predictions give the remaining binding curves in Fig. 7, where λ is now the equilibrium constant for transferring TnI from actin to Ca2TnC. If TnI binds more tightly to Ca2TnC than to actin, then λ > 1.

which equilibrates the binding of free TnI to TnC; in this case the quantity λ in Eq. A1 is the (first-order) binding constant of TnI to Ca2TnC. For troponins on tropomyosin in the regulated actin filament, ρ is a property of the whole filament and is predicted by the CFC model as a function of LTI and KS1 (Fig. 4). These predictions give the remaining binding curves in Fig. 7, where λ is now the equilibrium constant for transferring TnI from actin to Ca2TnC. If TnI binds more tightly to Ca2TnC than to actin, then λ > 1.

FIGURE 8.

Predictions for the mean calcium load  of TnC versus calcium concentration C, using the allosteric model of the Appendix, for isolated troponin, and from the chain model for the fully regulated actin filament (A-Tm-Tn) with and without myosin-S1 (KS1 = 1 and 0). Values of the constants in this model are λ = 10, ɛo = 0, and ɛ = 0.001 in all cases; however, the meaning of λ is different in the absence of actin (see main text). Increasing the value of λ favors the open state of TnC and displaces all binding curves to lower calcium. Curves for the actin system were generated by the chain model with βA = 1.5, ν = 3, and βB = 0.01 (A) or 1.0 (B) for TnI kink energy. The corresponding Hill plots (C), (D) show that biphasic behavior is generated in both cases by adding myosin.

of TnC versus calcium concentration C, using the allosteric model of the Appendix, for isolated troponin, and from the chain model for the fully regulated actin filament (A-Tm-Tn) with and without myosin-S1 (KS1 = 1 and 0). Values of the constants in this model are λ = 10, ɛo = 0, and ɛ = 0.001 in all cases; however, the meaning of λ is different in the absence of actin (see main text). Increasing the value of λ favors the open state of TnC and displaces all binding curves to lower calcium. Curves for the actin system were generated by the chain model with βA = 1.5, ν = 3, and βB = 0.01 (A) or 1.0 (B) for TnI kink energy. The corresponding Hill plots (C), (D) show that biphasic behavior is generated in both cases by adding myosin.

For the case B = 0 (Fig. 8 A), each TnI binds independently to actin so the predicted calcium loading curves are the same for Tn and actin-Tm-Tn if, for the sake of illustration, λ has the same value in each system. For the latter, a nonsaturating concentration of myosin detaches TnI molecules from actin into the hands of TnC which, by the proposed allosteric mechanism, increases its equilibrated calcium load. The increased slope of the loading curve is shown in the Hill plot below (Fig. 8 C) and reflects the increased slope of the TnI binding curve (Fig. 4 D) on adding myosin, at an intermediate value of LTI, say 50.

When TnI binding requires a kinked chain (B = kBT, Fig. 8 B), the loading curves for actin-Tm-Tn show the effects of TnI-TnI interactions operating both in the absence and the presence of myosin. Consider the effects of lowering the calcium level through the transition region. In the absence of myosin, cooperative actin binding of TnI under TnI-induced chain kinks produces a slightly bigger loss of TnI from TnC than occurs when TnI's bind independently to actin; the effect is small because the TnI switching affinity L* is lower than the range of TnI affinities explored by calcium. In the presence of myosin, the switching affinity of TnI is driven up into the middle of the range generated by calcium variation so that the effects of I-I interactions are apparent, giving a steeper loading curve than in Fig. 8 A. Fig. 8 D shows the associated Hill plots.

The loading curves in Fig. 8 B have the same features as those observed by Grabarek et al. (1983), except that the measured curve for isolated troponin is displaced to higher calcium. This displacement would be produced by using a lower value of λ; the limiting case λ = 0 is sufficient to describe the calcium loading of TnC alone. However, the reaction scheme in the Appendix implies that the Tn curves in Fig. 8 are for a different reaction, namely calcium loading of TnC accompanied by distal binding of TnI to TnC in the whole troponin complex (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

The experimental data considered does suggest that chain kink energies are a somewhat variable property of regulated actin filaments. This was apparent in the preceding article, where myosin kink energies for actin-Tm systems with skeletal and smooth tropomyosin were not in accord with the resting positions of the chain deduced from structural studies. For actin-Tm-Tn systems, a similar variability is apparent in the TnI kink energy; a very small value B ≪ kBT is required to fit the myosin titration data at low calcium and give a nominal Hill coefficient of 2.0 for the kinetic measurements of Head et al. (1995), but the remaining experiments considered required B ∼ kBT for autocooperative binding of TnI. Both variations would be generated by changes in the resting orientation of the chain on actin, relative to the binding domains of myosin and TnI, which would produce equal and opposite changes in  and

and  . If this orientation is determined by a weak electrostatic confining potential, it might well be sensitive to changes in pH and ionic strength.

. If this orientation is determined by a weak electrostatic confining potential, it might well be sensitive to changes in pH and ionic strength.

While the CFC model provides the core of an explanation for the biphasic force-calcium relationship in striated muscle, the theory in its present form is not strictly applicable to the muscle fiber. Isometric muscle tension is not strictly proportional to the number of strongly-bound myosins (Bagni et al., 1988; Mijailovich et al., 1996). Secondly, not all actin sites may be accessed by myosins tethered to thick filaments. For a fixed-end fiber in active contraction, a range of experiments indicate that only 25–43% of myosin-S1 heads are strongly bound to thin filaments (Linari et al., 1998 and references therein), which implies that only 14–25% of actin sites are occupied (Squire, 1981). Hence the mean nearest-neighbor spacing of sites accessible by tethered myosins is of the order of three to six monomers, not much less than the width of chain kinks predicted by the CFC model. However, sarcomeric models suggest that there is a wide distribution of nearest-neighbor spacings, with spacings of one or two monomers as likely as the mean spacing. Thus some myosins will bind to nearest-neighbor or next-nearest-neighbor monomers as required for the release of inhibition by the chain. In the muscle fiber, the mean first-order affinity for competent myosins, however defined, is likely to be of the order of one to two, which is in the predicted range for optimal regulation of myosin binding by TnI and hence by calcium (Figs. 4 and 5). Thus the present model should give qualitative indications for fibers, but its predictions should be checked from a sarcomeric model with tethered myosins.

It may not be apparent that the CFC model can be applied to myosin binding under ATP-cycling conditions which generate force in the muscle fiber. Although the chain model has been developed using equilibrium statistical mechanics, its predictions can be applied under steady-state ATP-cycling conditions by re-interpreting the first-order myosin binding constant KS1 as the ratio of rate constants for irreversible binding and detachment. This trick allows the model to address many other experiments. However, the chain may not regulate myosin affinity and the rate of myosin binding in the same way.

Other aspects of muscle regulation which can be addressed by the CFC model in its present form are as follows. 1), The biphasic force-calcium Hill plot observed by Moss et al. (1983) is replaced by a straight-line plot with slope near 2 when the muscle fiber is stretched beyond overlap. This could be a consequence of detuning the TnI switching affinity if the accompanying decrease in lattice spacing increases myosin affinity (Brenner et al., 1996). This effect would lower the calcium level for half activation at large sarcomere lengths where the overlap of filaments is small (Endo, 1972). 2), Similarly, there are many reports of a symmetric force-calcium relationship in different muscle types at full overlap (e.g., Stephenson and Williams, 1982; Stienen et al., 1985), which could have different myosin affinities in the fiber, or a different resting position of the Tm chain from which TnI molecules could bind to actin without kinking. 3), Calcium regulation of muscle contractility is diminished as the rigor condition, in which all myosins are bound, is approached by reducing the ambient concentration of ATP (Güth and Potter, 1987; Swartz et al., 1996). Many strongly bound myosins hold the chain in an open configuration and would not allow TnI molecules to bind to actin when calcium is removed.

Note the different uses of apparently equivalent terminologies for tropomyosin states in these articles and Lehman et al. (2000, 2001). Here and in I, the closed state denotes orientations of the Tm chain in the absence of myosin and troponin, open state denotes the new orientation generated when the chain is saturated by bound myosins or the local kink produced by a single bound myosin, and blocked state the orientations produced by bound troponin-I's in the absence of bound myosins. However, Lehman et al. use the letters C,B,M to denote three specific chain orientations on actin, lying between the two domains of actin, near the outer domain and near the inner domain respectively. Confusion can arise because in different actin-Tm systems the closed state may have different positions (designated C or B) relative to actin.

CONCLUSIONS

The extension of the chain model to actin-Tm-Tn systems, with calcium control of the equilibrium binding of TnI to actin, provides a reasonably complete model of thin filament regulation in solution which accounts for many calcium-dependent properties of the regulated filament. Myosin titration data at +Ca and −Ca can be fitted by the model, but do not provide a conclusive test; this data can also be fitted by the rigid-unit model (McKillop and Geeves, 1993) and the model of Hill, Eisenberg and Greene (1980). The calcium-dependence of thin-filament properties provide a more searching test of models. The predictions of the CFC model enable calcium-dependent phenomena described in the introduction to be understood in terms of myosin-myosin, myosin-TnI, and TnI-TnI pair interactions (M-M, M-I, and I-I), where the actin affinity of TnI is downregulated by the calcium load of TnC. Our conclusions are as follows.

Myosin-myosin cooperativity, manifested by a concave binding curve at low concentrations, is observed at high calcium, and arises solely from M-M interactions as in I. The degree of cooperativity is determined by the persistence length of the Tm chain, which is not simply related to the myosin-myosin Hill coefficient (maximum slope of the Hill plot) but can be estimated from a derived switching curve described in I. The titration data analyzed in this article does not suggest that the intrinsic persistence length is calcium-dependent. M-M interactions operate at all calcium levels. At low calcium, myosin-myosin cooperativity is also produced by M-I interactions in which bound myosins detach TnI molecules from actin. This mechanism is enhanced by I-I interactions, which are present only if TnI molecules require a kinked chain to bind to actin and these kinks can overlap (empirically, B/kBT > 0.3 and ν > 3). I-I interactions stabilize the blocked state at low calcium, which is broken down by M-I interactions as more myosins bind.

Calcium-calcium cooperativity in the absence of myosin is observed in the calcium loading curve of TnC, and starts with the intrinsic cooperativity of an isolated troponin molecule, giving a Ca-Ca Hill coefficient of between one and two for skeletal TnC. For calcium binding to the A-Tm·Tn filament, this Hill coefficient is increased by I-I interactions if present. This effect is observed by Grabarek et al. (1983). The model predicts a somewhat smaller effect, which reflects the small switching affinity L* for the onset of cooperative actin-binding of TnI in the absence of myosin. With I-I interactions, TnI binds cooperatively to actin only at high affinity (LTI > L*), equivalent to low calcium (C < C*).

Myosin binding is regulated by calcium as a consequence of calcium-TnI coupling and M-I interactions, in which myosin affinity is reduced by the actin-binding of neighboring enchained TnI molecules as the calcium level is lowered. The calcium level C0.5 for half-maximal activation is a decreasing function of myosin affinity, and is also decreased by M-M interactions, which kick in at a somewhat lower level of activation where the bound myosin fraction is of order 1/ν. If I-I interactions are present, their stabilizing effect on the blocked state is broken down by myosins binding as the calcium level is raised, so that C0.5 is decreased. For myosins in solution, their sevenfold site advantage over TnI ensures that these tunings are sensitive. In striated muscles, |log10C0.5| lies between 5 and 7.

Myosin-calcium cooperativity. In the absence of I-I interactions, the Hill coefficient for the calcium dependence of myosin binding is close to two, reflecting allosteric TnC-TnI coupling (as described in the Appendix) for each troponin on the chain. I-I interactions increase this Hill coefficient for calcium concentrations near C*, where TnI-induced chain kinks start to overlap. Through M-I interactions, C* and C0.5 are both tuned by myosin affinity in the same way. In striated muscle, it appears that in some circumstances C* ≤ C0.5, giving a biphasic Hill plot. When B → 0, I-I interactions become very small and L* → 0, C* → ∞, giving a straight-line Hill plot with a slope near two.

Calcium-calcium cooperativity is enhanced by myosin. The calcium loading curve of TnC on fully-regulated actin becomes steeper when myosin is added. This effect is caused by a combination of M-I interactions, in which enchained TnI's can be cooperatively detached by an intervening bound myosin within one persistence length of each of them, even when B = 0. The degree of cooperativity is enhanced when I-I interactions are present. The Hill plot may again appear biphasic with a higher slope at low calcium, for the same reason as above.

In general, we suggest that variation in the Hill coefficients for calcium-dependent properties of the regulated thin filament can be understood in terms of the concept of cooperative switching of actin-TnI interactions. There is a switching range of calcium concentrations, between a weak-binding regime at high calcium in which enchained TnI molecules bind independently to actin and the chain is in a mixture of closed state and open states, and a strong-binding regime at low calcium in which these TnI molecules bind cooperatively through chain displacements and the chain is mainly in the blocked state. Cooperative binding at low calcium might arise directly from I-I pair interactions, or indirectly in the presence of bound myosin from M-I pair interactions. The effects of these interactions also depend on the calcium-dependent property in question. A Hill coefficient above the maximum value from independent calcium-binding entities (two for skeletal TnC) is expected only in the switching range of calcium levels. We suggest that the definition of Hill coefficient used in this article (maximum slope of the Hill plot, which locates the switching concentration) is a better measure of cooperativity than the usual definition (slope at half-activation). The width of the switching region is a decreasing function of the degree of cooperativity, but is always finite as expected for a one-dimensional cooperative system.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. S.S. Lehrer for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. This work was supported by program grants from the Wellcome Trust (D.A.S., M.A.G.) and the National Institutes of Health (M.A.G.).

APPENDIX: CALCIUM-DEPENDENT BINDING OF TNI TO ACTIN

It is generally agreed that calcium regulation of myosin binding and muscle contraction requires an allosteric mechanism to regulate the actin affinity of troponin-I as a continuous decreasing function of calcium level. This is achieved through the competitive binding of TnI to TnC, which is favored at high calcium when both calcium-binding sites on the regulatory N-terminal domain of TnC are occupied and a hydrophobic patch is exposed to capture the C-terminal of TnI (Herzberg et al. 1986). Open and closed allosteric states of TnC with one or two Ca++ ions bound to these sites have been identified by McKay et al. (2000). The following scheme is intended as a minimal description of this mechanism, suitable for predicting the calcium dependence of LTI:

Figure 9.

Allosteric states of CamTnC for each m = 0,1,2 have been lumped together, and the closed state predominates. Similarly, allosteric forms of CamTnC. TnI are lumped, and the open state predominates for m = 2 and has been detected for m = 1. For simplicity, the switching of TnI from actin to TnC is treated as a single reaction, with a first-order affinity λ when two calciums are bound. If all reactions proceed to equilibrium, the effective affinity of TnI for actin at free calcium concentration C is

|

(A1) |

where  For intact skeletal troponin, the scheme of McKay et al. (2000) indicates that ɛo = 0 and ɛ ≪ 1, assuming that the allosteric fractions ɛo,ɛ for the release of TnI from TnC are unchanged by its subsequent binding to actin. The precise value of λ is not known, but the activation of actin-myosin interactions at high calcium appears to require λ > 1. Whether this is so in practice remains to be seen.

For intact skeletal troponin, the scheme of McKay et al. (2000) indicates that ɛo = 0 and ɛ ≪ 1, assuming that the allosteric fractions ɛo,ɛ for the release of TnI from TnC are unchanged by its subsequent binding to actin. The precise value of λ is not known, but the activation of actin-myosin interactions at high calcium appears to require λ > 1. Whether this is so in practice remains to be seen.

Double logarithmic plots of Eq. A1 (Fig. 7) show that LTI(C) decreases quadratically with calcium concentration C only over a limited range, even for the most favorable case with ɛo = 0 and ɛ ≪ 1. The maximum absolute slope is close but not equal to 2. At high calcium (pCa < 6) the curve flattens as TnC saturates with TnI, which gives a lower Hill coefficient for myosin binding at high levels of activation. At very low calcium (pCa > 8), the absolute slope changes toward unity, reflecting the dominance of TnC states with only one bound calcium; in this region the level of myosin activation is too low to be detected. As the value of ɛ is raised, the extent of regulation of the actin-TnI interaction by calcium is reduced, and the apparent two-for-one relationship between myosin Hill coefficient as functions of LTI and calcium respectively is gradually eroded. If the second calcium binding site is disabled (K2 = 0), as in cardiac TnC, LTI(C) decreases linearly with calcium concentration at low calcium provided that ɛo ≪ 1.

In the body of this article, the open and closed states of TnC are renamed in and out respectively to avoid the terminology adopted for tropomyosin states. The in state refers only to open states of TnC in which the distal part of TnI is captured (Fig. 1 B).

References

- Allen, D. G., and S. Kurihara. 1982. The effects of muscle length on intracellular calcium transients in mammalian cardiac muscle. J. Physiol. 327:79–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagni, M. A., G. Cecchi, and M. Schonberg. 1988. A model of force production that explains the lag between crossbridge attachment and force after electrical stimulation of striated muscle fibers. Biophys. J. 54:1105–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremel, R. D., and A. Weber. 1972. Cooperation within actin filament in vertebrate skeletal muscle. Nat. New Biol. 238:97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, B., S. Xu, J. M. Chalovich, and L. C. Yu. 1996. Radial equilibrium lengths of actomyosin cross-bridges in muscle. Biophys. J. 71:2751–2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebashi, S. 1977. Troponin and its function. In Search and Discovery: A Tribute to Albert Szent-Gyorgi. B. Kaminer, editor. Academic Press, New York.

- Endo, M. 1972. Stretch-induced increase in activation of skinned muscle fibres by calcium. Nature New Biol. 237:211–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne, S. M., S. Tsuda, M. X. Li, L. B. Smillie, and B. D. Sykes. 1995. Structures of the troponin C regulatory domains in the apo and calcium-saturated states. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2:784–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, A. M., E. Homsher, and M. Regnier. 2000. Regulation of contraction in striated muscle. Physiol. Rev. 80:853–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabarek, Z., J. Grabarek, P. C. Leavis, and J. Gergely. 1983. Cooperative binding to the Ca2+-specific sites of troponin C in regulated actin and actomyosin. J. Biol. Chem. 258:14098–14105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabarek, Z., T. Tao, and J. Gergely. 1992. Molecular mechanism of troponin-C function. J. Muscle Res. Cell Mot. 13:383–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güth, K., and J. D. Potter. 1987. Effect of rigor and cycling cross-bridges on the structure of troponin C and on the Ca2+ affinity of the Ca2+-specific regulatory sites in skinned rabbit psoas muscle fibers. J. Biol. Chem. 262:13627–13635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head, J. G., M. D. Ritchie, and M. A. Geeves. 1995. Characterization of the equilibrium between blocked and closed states of muscle thin filaments. Eur. J. Biochem. 227:694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, O., J. Moult, and M. N. G. James. 1986. A model for the Ca2+-induced conformational transition of troponin C: a trigger for muscle contraction. J. Biol. Chem. 261:2638–2644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, T. L., E. Eisenberg, and L. Greene. 1980. Theoretical model for the cooperative equilibrium binding of myosin subfragment 1 to the actin-troponin-tropomyosin complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 77:3186–3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, W., V. Hatch, V. Korman, M. R. L. Thomas, R. Maytum, M. A. Geeves, J. E. van Eyk, L. S. Tobacman, and R. Craig. 2000. Tropomyosin and actin isoforms modulate the localization of tropomyosin strands on actin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 302:593–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, W., M. Rosol, L. S. Tobacman, and R. Craig. 2001. Troponin organization on relaxed and activated thin filaments revealed by electron microscopy and three-dimensional reconstruction. J. Mol. Biol. 307:739–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linari, M., I. Dobbie, M. Reconditi, N. Koubassova, M. Irving, G. Piazzesi, and V. Lombardi. 1998. The stiffness of skeletal muscle in isometric contraction and rigor: the fraction of myosin heads bound to actin. Biophys. J. 74:2459–2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maytum, R. M., S. S. Lehrer, and M. A. Geeves. 1999. Cooperativity and switching within the three-state model of muscle regulation. Biochemistry. 38:1102–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay, R. T., L. F. Saltibus, M. X. Li, and B. D. Sykes. 2000. Energetics of the induced structural change in a Ca2+ regulatory protein: Ca2+ and troponin I peptide binding to the E41A mutant of the N-domain of skeletal troponin C. Biochemistry. 39:12731–12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKillop, D. F. A., and M. A. Geeves. 1993. Regulation of the interaction between actin and myosin subfragment 1: evidence for three states of the thin filament. Biophys. J. 65:693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mijailovich, S. M., J. J. Fredberg, and J. P. Butler. 1996. On the theory of muscle contraction: filament extensibility and the development of isometric force and stiffness. Biophys. J. 71:1475–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss, R. L., A. E. Swinford, and M. L. Greaser. 1983. Alterations in the Ca2+ sensitivity of tension development by single skeletal muscle fibers at stretched lengths. Biophys. J. 43:115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita, A., T. Yasunaga, T. Ishikawa, K. Mayanagi, and T. Wakabayashi. 2001. Ca2+-induced switching of troponin and tropomyosin on actin filaments as revealed by electron cryo-microscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 308:241–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, J. D., and J. Gergely. 1975. The calcium and magnesium binding sites on troponin and their role in the regulation of myofibrillar adenosine triphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 250:4628–4633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press, W. H., S. A. Teukolsky, W. T. Vetterling, and B. R. Flannery. 1992. Numerical Recipes in Fortran, 2nd Ed. Cambridge, UK.

- Smith, D. A. 2001. Path integral theory of an axially-confined worm-like chain. J. Phys. A. Math. Gen. 34:4507–4523. [Google Scholar]

- Squire, J. M. 1981. The Structural Basis of Muscle Contraction. Plenum Press, New York.

- Stephenson, D. G., and D. A. Williams. 1982. Effects of sarcomere length on the force-pCa relation in fast- and slow-twitch skinned muscle fibres from the rat. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 333:637–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stienen, G. J. M., T. Blangé, and B. W. Trietjel. 1985. Tension development and calcium sensitivity in skinned muscle fibres of the frog. Pflugers Arch. 405:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, D. R., R. L. Moss, and M. L. Greaser. 1996. Calcium alone does not fully activate the thin filament for S1 binding to rigor myofibrils. Biophys. J. 71:1891–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripet, B., J. E. van Eyk, and R. S. Hodges. 1997. Mapping of a second actin-tropomyosin and a second troponin C binding site within the C terminus of Troponin I, and their importance in the Ca2+-dependent regulation of muscle contraction. J. Mol. Biol. 271:728–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]