Abstract

Cationic liposomes (CLs) are used worldwide as gene vectors (carriers) in nonviral clinical applications of gene delivery, albeit with unacceptably low transfection efficiencies (TE). We present three-dimensional laser scanning confocal microscopy studies revealing distinct interactions between CL-DNA complexes, for both lamellar LαC and inverted hexagonal HIIC nanostructures, and mouse fibroblast cells. Confocal images of LαC complexes in cells identified two regimes. For low membrane charge density (σM), DNA remained trapped in CL-vectors. By contrast, for high σM, released DNA was observed in the cytoplasm, indicative of escape from endosomes through fusion. Remarkably, firefly luciferase reporter gene studies in the highly complex LαC-mammalian cell system revealed an unexpected simplicity where, at a constant cationic to anionic charge ratio, TE data for univalent and multivalent cationic lipids merged into a single curve as a function of σM, identifying it as a key universal parameter. The universal curve for transfection by LαC complexes climbs exponentially over ≈ four decades with increasing σM below an optimal charge density (σM*), and saturates for  at a value rivaling the high transfection efficiency of HIIC complexes. In contrast, the transfection efficiency of HIIC complexes is independent of σM. The exponential dependence of TE on σM for LαC complexes, suggests the existence of a kinetic barrier against endosomal fusion, where an increase in σM lowers the barrier. In the saturated TE regime, for both LαC complexes and HIIC, confocal microscopy reveals the dissociation of lipid and DNA. However, the lipid-released DNA is observed to be in a condensed state, most likely with oppositely charged macro-ion condensing agents from the cytoplasm, which remain to be identified. Much of the observed bulk of condensed DNA may be transcriptionally inactive and may determine the current limiting factor to transfection by cationic lipid gene vectors.

at a value rivaling the high transfection efficiency of HIIC complexes. In contrast, the transfection efficiency of HIIC complexes is independent of σM. The exponential dependence of TE on σM for LαC complexes, suggests the existence of a kinetic barrier against endosomal fusion, where an increase in σM lowers the barrier. In the saturated TE regime, for both LαC complexes and HIIC, confocal microscopy reveals the dissociation of lipid and DNA. However, the lipid-released DNA is observed to be in a condensed state, most likely with oppositely charged macro-ion condensing agents from the cytoplasm, which remain to be identified. Much of the observed bulk of condensed DNA may be transcriptionally inactive and may determine the current limiting factor to transfection by cationic lipid gene vectors.

INTRODUCTION

The unrelenting research activity involving gene therapy with either synthetic vectors (carriers) or engineered viruses is currently unprecedented (Alper, 2002; Chesnoy and Huang, 2000; Clark and Hersh, 1999; Ferber, 2001; Henry, 2001; Mahato and Kim, 2002; Miller, 1998). After the initial landmark studies (Felgner et al., 1987; Nabel et al., 1993; Singhal and Huang, 1994), cationic liposomes (CLs; closed bilayer membrane shells of lipid molecules) have emerged worldwide as the most prevalent synthetic vectors (carriers) (Ferber, 2001) whose mechanisms of action are investigated extensively in research laboratories, concurrently with ongoing, mostly empirical, clinical trials to develop cancer vaccines (Alper, 2002; Chesnoy and Huang, 2000; Clark and Hersh, 1999; Ferber, 2001; Henry, 2001; Mahato and Kim, 2002; Miller, 1998). Primary among the advantages of CL over viral methods is the lack of immune response due to the absence of viral peptides and proteins. Moreover, while viral capsids have a maximum DNA-carrying capacity of ∼40 kbp, CLs (which, when combined with DNA, form, in most instances, self-assemblies with distinct lamellar  or inverted hexagonal

or inverted hexagonal  nanostructures; see Raedler et al., 1997; Koltover et al., 1998; Lasic et al., 1997), place no limit on the size of the DNA. Thus, if complexed, for example, with human artificial chromosomes (Wilard, 2000), optimally designed CL-carriers offer the potential of potent vectors comprised of multiple human genes and regulatory sequences extending over hundreds of thousands of DNA base pairs.

nanostructures; see Raedler et al., 1997; Koltover et al., 1998; Lasic et al., 1997), place no limit on the size of the DNA. Thus, if complexed, for example, with human artificial chromosomes (Wilard, 2000), optimally designed CL-carriers offer the potential of potent vectors comprised of multiple human genes and regulatory sequences extending over hundreds of thousands of DNA base pairs.

Despite all the promise of CLs as gene vectors, their transfection efficiency (TE; ability to transfer DNA into cells followed by expression), compared to viral vectors, remains notoriously low, resulting in a flurry of research activity aimed at enhancing transfection (Alper, 2002; Chesnoy and Huang, 2000; Clark and Hersh, 1999; Ferber, 2001; Henry, 2001; Mahato and Kim, 2002; Miller, 1998). A further sense of urgency for developing efficient synthetic carriers stems from the recent tragic events associated with the use of engineered adenovirus vectors leading to the death of a patient due to an unanticipated severe immune response (Marshall, 2000). In addition, in the latest gene therapy trials using modified retrovirus vectors to treat children with severe combined immunodeficiency, a French gene therapy team has reported a major setback where one patient (out of eleven) developed a blood disorder similar to leukemia which is confirmed to have resulted from insertion of the modified retrovirus in the initial coding region of a gene related to the early development of blood cells (Marshall, 2002).

Our in vitro studies should apply to TE optimization in ex vivo cell transfection, where cells are removed and returned to patients after transfection. In particular, our studies, aimed at understanding the chemically and physically dependent mechanisms underlying TE in continuous (dividing) cell lines, should aid clinical efforts to develop efficient CL-vector cancer vaccines in ex vivo applications. The vaccines are intended to induce transient expression of genes coding for immunostimulatory proteins in dividing cells (Chesnoy and Huang, 2000; Nabel et al., 1993; Rinehart et al., 1997; Stopeck et al., 1998); thus, the nuclear membrane, which dissolves during mitosis, is not considered a barrier to expression of DNA.

A critical requirement for enhancing transfection via synthetic carriers is a full understanding of the different nanostructures of CL-DNA complexes and the physical and chemical basis of interactions between complexes and cellular components. Toward that end, we used a combination of three-dimensional laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM), which closely followed complexes across the plasma membrane and inside the cytoplasm, and reporter gene TE studies that gave a statistically meaningful measure of the total amount of protein synthesized by cells from delivered DNA. Furthermore, we examined the structure-dependent basis of transfection through imaging of CL-DNA complexes exhibiting either the  (cationic lipid DOTAP mixed with neutral lipid DOPC) or

(cationic lipid DOTAP mixed with neutral lipid DOPC) or  (DOTAP mixed with neutral lipid DOPE) nanostructure (Koltover et al., 1998; Raedler et al., 1997). Previous to our report, TE studies had shown that in mixtures of DOTAP and neutral lipids, typically at a wt.:wt. ratio of between 1:1 and 1:3, DOPE aided, while DOPC severely suppressed, transfection (Farhood et al., 1995; Hui et al., 1996), hence suggesting that

(DOTAP mixed with neutral lipid DOPE) nanostructure (Koltover et al., 1998; Raedler et al., 1997). Previous to our report, TE studies had shown that in mixtures of DOTAP and neutral lipids, typically at a wt.:wt. ratio of between 1:1 and 1:3, DOPE aided, while DOPC severely suppressed, transfection (Farhood et al., 1995; Hui et al., 1996), hence suggesting that  complexes transfect more efficiently than

complexes transfect more efficiently than  complexes.

complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Lipids included univalent cationic lipids DOTAP (1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethyl-ammonium-propane) and DMRIE (n-(2-hydroxyethyl)-n,n-dimethyl-2,3-bis(tetradecyloxy)-1-propanaminium), multivalent cationic lipid DOSPA (2,3-Dioleyloxy-n-(2-(sperminecarboxamido)ethyl)-n,n-dimethyl-1-propaniminium penta-hydrochloride), and neutral lipids DOPC (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) and DOPE (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine). DOTAP, DOPC, DOPE were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., and DMRIE and DOSPA were gifts from Vical Inc. Plasmid DNA containing the Luciferase gene and SV40 promoter/enhancer elements was used (pGL3-control vector, Promega, Cat. E1741).

Cell culture

Mouse fibroblast L-cell lines were subcultured in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, Gibco BRL) supplemented with 1% (vol/vol) penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco BRL) and 5% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (HyClone Lab) at 37°C and 5% CO2 atmosphere every 2–4 days to maintain monolayer coverage.

Liposome preparation

Neutral lipids (DOPE, DOPC) were dissolved in chloroform and cationic lipids (DOTAP, DOSPA, DMRIE) were dissolved in a chloroform/methanol mixture. The lipid solutions were mixed in required ratios and the solvent was evaporated, first under a stream of nitrogen and then in vacuum over night, leaving a lipid film behind. The appropriate amount of millipore water was added to the dried lipid film, resulting in the desired concentration (0.1 mg/ml–25 mg/ml) and incubated at 37°C for at least 6 h to allow formation of liposomes. To form small unilamellar vesicles, liposome solutions were vortexed for 1 min, tip-sonicated to clarity (for 5–10 min), and filtered with 0.2 μm filters to remove metal particulates arising from the sonicator tip. Liposome solutions were then stored at 4°C.

Transfection

L-cells were transfected at a confluency of 60–80%. Using liposome (0.5 mg/ml) and DNA (1 mg/ml) stock solutions, CL-DNA complexes were prepared in DMEM, which contained 2 μg of pGL3-DNA at a cationic-to-anionic charge ratio of 2.8 and allowed to sit for 20 min for complex formation. The cells were then incubated with complexes for 6 h, the optimized time of transfer into cells before removal, rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (Gibco BRL), and incubated in supplemented DMEM for an additional 24 h (sufficient for a complete cell cycle) to allow expression of the luciferase gene. Luciferase gene expression was measured with the Luciferase Assay System from Promega. Each transfection experiment was repeated between 3–6 times over a short period of a few days yielding the error bars (Slack, 2000; Lin et al., 2002). In addition, the experiments were repeated four times over a 12-month period using different cell batches. While the absolute value of the average of each transfection measurement between the different experiments (done with several months separating experiments) varied by as much as a decade (which is also commonly found by other groups; Boussif et al., 1995), the observed trend in the transfection data was completely reproducible. Transfection efficiency was normalized to mg of total cellular protein using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye Reagent Concentration solution (Bio-Rad) and is expressed as relative light units per mg of total cellular protein ± 1 SD. The transfection protocol is commonly used by others (Boussif et al., 1995).

Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM)

L-cells were seeded on coverslips in six-well plates and allowed to grow, reaching a confluency of 60–80%. DNA was labeled following the Mirus Label IT (PanVera Corporation) protocol, which is fluorescent at 492 nm. Lipids were labeled with 0.2% (wt) Texas Red DHPE (Molecular Probes), which is fluorescent at 583 nm. Using labeled liposome (0.5 mg/ml) and DNA (0.1 mg/ml) stock solutions, CL-DNA complexes were prepared in DMEM using 2 μg of pGL3-DNA (at a cationic to anionic charge ratio of 2.8), allowed to sit for 20 min for complex formation, and incubated with cells for the optimal 6-h transfer time. Cells were rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (Gibco BRL), fixed by soaking in a fixing solution (3.7% formaldehyde in PBS) for 20–30 min and mounted using SlowFade Light Antifade Kit (Molecular Probes) for microscopy. Confocal images were taken with a Leica DM IRBE confocal microscope. The images of Figs. 3 and 5 (repeated more than 10 times) are representative of the typical behavior in a given field of view (Lin, 2001).

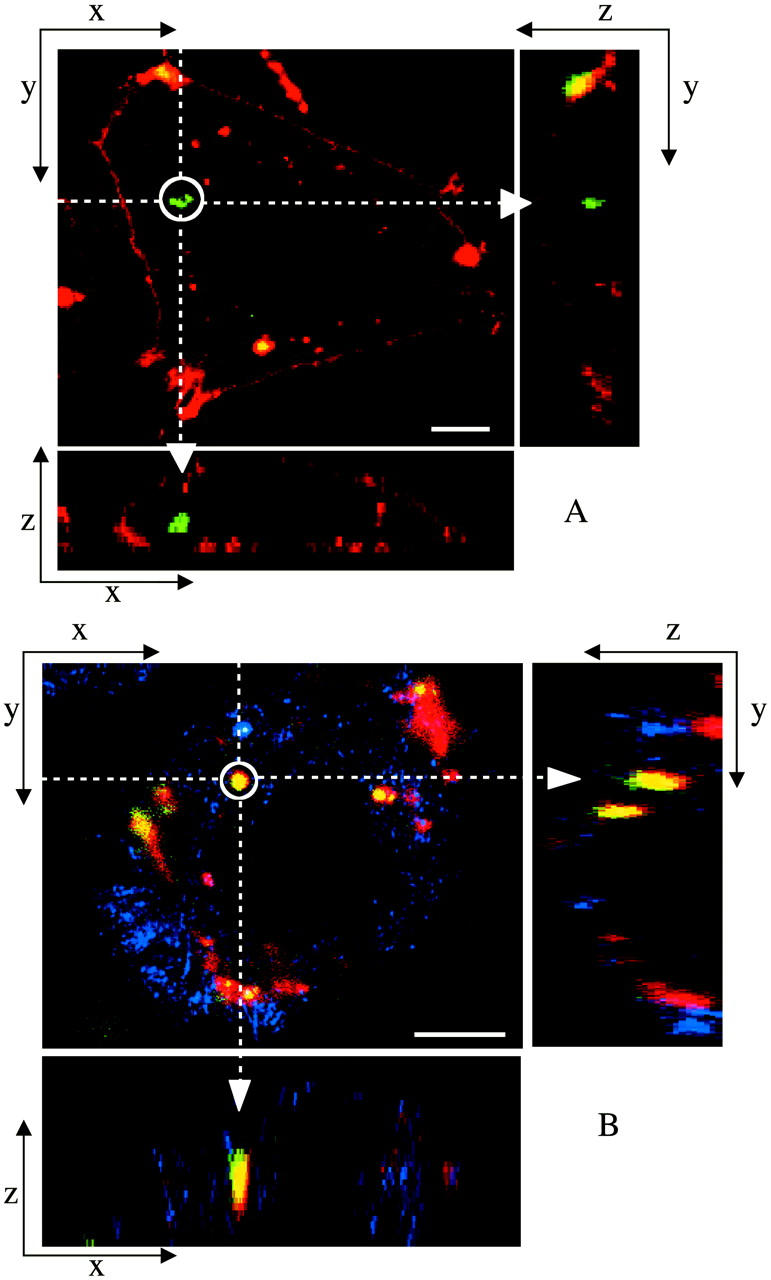

FIGURE 3.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) images of transfected mouse L-cells. Red denotes lipid; green, DNA; and yellow, the overlap of the two denotes CL-DNA complexes. For each set, middle is the x-y top view at a given z; right is the y-z side view along the vertical dotted line; bottom is the x-z side view along the horizontal dotted line. Objects in circles are indicated by arrows in the x-z and y-z plane side views. (A) Cells transfected with  complexes (ΦDOPE = 0.69), show fusion of lipid (red) with the cell plasma membrane and the release of DNA (green in the circle) within the cell. Thus,

complexes (ΦDOPE = 0.69), show fusion of lipid (red) with the cell plasma membrane and the release of DNA (green in the circle) within the cell. Thus,  complexes display clear evidence of separation of lipid and DNA, which is consistent with the high transfection efficiency of such complexes. The released exogenous DNA is in an aggregated state, which implies that it has been condensed with oppositely charged biomolecules of the cell, which remain to be identified. (B) Cells transfected with

complexes display clear evidence of separation of lipid and DNA, which is consistent with the high transfection efficiency of such complexes. The released exogenous DNA is in an aggregated state, which implies that it has been condensed with oppositely charged biomolecules of the cell, which remain to be identified. (B) Cells transfected with  complexes at ΦDOPC = 0.67, which results in a low membrane charge density σM ≈ 0.005 e/Å2 and low transfection efficiency (as plotted in Fig. 4 B). First, no fusion is observed. Second, intact CL-DNA complexes are observed inside cells (one such yellow complex is shown in the circle). The intact complex implies that DNA remains trapped within the complex, which is consistent with the observed low transfection efficiency of such low

complexes at ΦDOPC = 0.67, which results in a low membrane charge density σM ≈ 0.005 e/Å2 and low transfection efficiency (as plotted in Fig. 4 B). First, no fusion is observed. Second, intact CL-DNA complexes are observed inside cells (one such yellow complex is shown in the circle). The intact complex implies that DNA remains trapped within the complex, which is consistent with the observed low transfection efficiency of such low  complexes. Because of the lack of fusion (which aided observation of the cell outline in A), we achieved cell outline by observation in reflection mode, which appears as blue. Bars = 5 μm applies to all planes.

complexes. Because of the lack of fusion (which aided observation of the cell outline in A), we achieved cell outline by observation in reflection mode, which appears as blue. Bars = 5 μm applies to all planes.

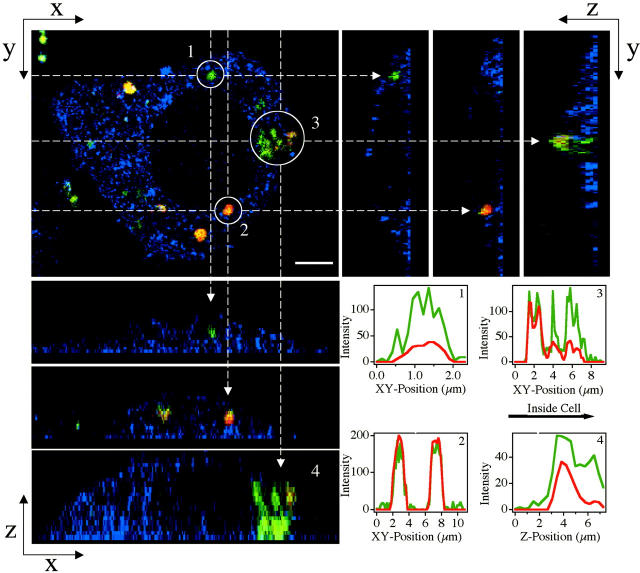

FIGURE 5.

LSCM images of a mouse L-cell transfected with  complexes at ΦDOPC = 0.18, which resulted in cationic membranes with a high charge density σM ≈ 0.012 e/Å2 and high transfection efficiency (as plotted in Fig. 4 B). Red denotes lipid; green, DNA; and yellow, the overlap of the two, CL-DNA complexes. Top left is the x-y top view at a given z. Objects in circles in the x-y plane are indicated by arrows in the side views. Panels in the top right are y-z side views along the vertical dashed lines (of the x-y plane). Panels in the bottom left are x-z side views along the horizontal dashed lines (of the x-y plane). Although these lamellar complexes have transfection efficiencies as high as those of the high-transfecting

complexes at ΦDOPC = 0.18, which resulted in cationic membranes with a high charge density σM ≈ 0.012 e/Å2 and high transfection efficiency (as plotted in Fig. 4 B). Red denotes lipid; green, DNA; and yellow, the overlap of the two, CL-DNA complexes. Top left is the x-y top view at a given z. Objects in circles in the x-y plane are indicated by arrows in the side views. Panels in the top right are y-z side views along the vertical dashed lines (of the x-y plane). Panels in the bottom left are x-z side views along the horizontal dashed lines (of the x-y plane). Although these lamellar complexes have transfection efficiencies as high as those of the high-transfecting  complexes, no fusion with the cell plasma membrane is seen in contrast to fusion observed in high-transfecting

complexes, no fusion with the cell plasma membrane is seen in contrast to fusion observed in high-transfecting  complexes (Fig. 3 A). Both released DNA (circle denoted as 1) and intact complexes (circle denoted as 2) are observed inside the cell. Very significantly, the observed released DNA is in an aggregated state, which implies that it resides in the cytoplasm and has escaped the endosome (as described in the text, in contrast to the cytoplasm, there are no known DNA condensing biomolecules in the endosome). (3 and 4) A complex in the process of releasing its DNA into the cytoplasm. Corresponding plots of fluorescence intensity as a function of position are shown in boxes in the lower right corner. Because of the lack of fusion (which aided observation of the cell outline in Fig. 3 A) we achieved cell outline by observation in reflection mode, which appears as blue. Bar = 5 μm applies to all planes.

complexes (Fig. 3 A). Both released DNA (circle denoted as 1) and intact complexes (circle denoted as 2) are observed inside the cell. Very significantly, the observed released DNA is in an aggregated state, which implies that it resides in the cytoplasm and has escaped the endosome (as described in the text, in contrast to the cytoplasm, there are no known DNA condensing biomolecules in the endosome). (3 and 4) A complex in the process of releasing its DNA into the cytoplasm. Corresponding plots of fluorescence intensity as a function of position are shown in boxes in the lower right corner. Because of the lack of fusion (which aided observation of the cell outline in Fig. 3 A) we achieved cell outline by observation in reflection mode, which appears as blue. Bar = 5 μm applies to all planes.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The XRD experiments were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory at 10 KeV. To prepare CL-DNA samples liposome solutions (25 mg/ml) and DNA solutions (5 mg/ml) were each diluted in DMEM at 1:1 (vol.:vol.), then mixed at the desired cationic to anionic charge ratio of 2.8 and centrifuged before loading into for 1.5-mm x-ray. We note that similar to previous findings (Koltover et al., 1998; Raedler et al., 1997) the self-assembled structures of CL-DNA complexes does not change in the concentration range between the x-ray samples and the samples for confocal microscopy and transfection.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

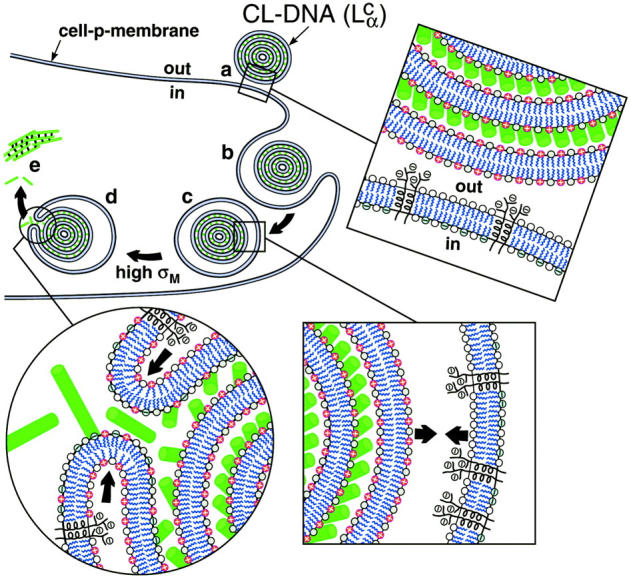

The initial electrostatic attraction between positively charged CL-DNA complexes and mammalian cells is known to be mediated by negatively charged cell surface sulfated proteoglycans (Fig. 1 a, expanded view; also see Mislick and Baldeschwieler, 1996). Consistent with previous studies, we found that  complexes gain entry into the cell through endocytosis (Fig. 1, b and c; see also Labat-Moleur et al., 1996; Zabner et al., 1995). LSCM of

complexes gain entry into the cell through endocytosis (Fig. 1, b and c; see also Labat-Moleur et al., 1996; Zabner et al., 1995). LSCM of  CL-DNA particles in cells revealed two distinct types of behavior. At low membrane charge density, σM ≈ 0.005 e/Å2 = e/(200 Å2), mostly intact

CL-DNA particles in cells revealed two distinct types of behavior. At low membrane charge density, σM ≈ 0.005 e/Å2 = e/(200 Å2), mostly intact  complexes were present inside cells implying that DNA was trapped by the lipid vector. Further TE experiments confirmed that the intact complexes were themselves trapped in endosomes (Fig. 1 c). At high σM ≈ 0.012 e/Å2 ≈ e/(83 Å2), we observed released DNA inside cells consistent with the escape of CL-DNA complexes into the cytoplasm through fusion with anionic endosomal membranes (Fig. 1 d). LSCM further determined that the released DNA was condensed (Fig. 1 e), most likely, with oppositely charged cytoplasmic condensing agents absent in endosomes. Unlike the endosomal environment, the cytoplasm contains many multivalent cationic biomolecules such as spermine and histones, which become available during the cell cycle in millimolar concentration levels, and are able to condense DNA (Bloomfield, 1991).

complexes were present inside cells implying that DNA was trapped by the lipid vector. Further TE experiments confirmed that the intact complexes were themselves trapped in endosomes (Fig. 1 c). At high σM ≈ 0.012 e/Å2 ≈ e/(83 Å2), we observed released DNA inside cells consistent with the escape of CL-DNA complexes into the cytoplasm through fusion with anionic endosomal membranes (Fig. 1 d). LSCM further determined that the released DNA was condensed (Fig. 1 e), most likely, with oppositely charged cytoplasmic condensing agents absent in endosomes. Unlike the endosomal environment, the cytoplasm contains many multivalent cationic biomolecules such as spermine and histones, which become available during the cell cycle in millimolar concentration levels, and are able to condense DNA (Bloomfield, 1991).

FIGURE 1.

Model of cellular uptake of  complexes. (a) Cationic complexes adhere to cells due to electrostatic attraction between positively charged CL-DNA complexes and negatively charged cell-surface sulfated proteoglycans (shown in expanded views) of mammalian plasma membranes. (b and c) After attachment, complexes enter through endocytosis. (d) Only those complexes with a large enough membrane charge density (σM) escape the endosome through activated fusion with endosomal membranes. (e) Released DNA inside the cell is observed by comfocal microscopy to be present primarily in the form of aggregates. The DNA aggregates must reside in the cytoplasm because oppositely charged cellular biomolecules able to condense DNA are not present in the endosome. Arrows in the expanded view of c indicate the electrostatic attraction between the positively charged membranes of the complex and the negatively charged membranes of the endosome (comprised of sulfated proteoglycans and anionic lipids), which tends to enhance adhesion and fusion. Arrows in the expanded view in d indicate that the bending of the membranes hinders fusion.

complexes. (a) Cationic complexes adhere to cells due to electrostatic attraction between positively charged CL-DNA complexes and negatively charged cell-surface sulfated proteoglycans (shown in expanded views) of mammalian plasma membranes. (b and c) After attachment, complexes enter through endocytosis. (d) Only those complexes with a large enough membrane charge density (σM) escape the endosome through activated fusion with endosomal membranes. (e) Released DNA inside the cell is observed by comfocal microscopy to be present primarily in the form of aggregates. The DNA aggregates must reside in the cytoplasm because oppositely charged cellular biomolecules able to condense DNA are not present in the endosome. Arrows in the expanded view of c indicate the electrostatic attraction between the positively charged membranes of the complex and the negatively charged membranes of the endosome (comprised of sulfated proteoglycans and anionic lipids), which tends to enhance adhesion and fusion. Arrows in the expanded view in d indicate that the bending of the membranes hinders fusion.

Corresponding TE measurements exhibited two remarkable features. First and foremost, an unexpected simplicity emerged from this highly complex  -cell system, where σM was found to be a universal parameter controlling TE. The TE data for

-cell system, where σM was found to be a universal parameter controlling TE. The TE data for  complexes containing DOPC mixed with the multivalent cationic lipid DOSPA or the univalent cationic lipids DOTAP and DMRIE, at a constant cationic to anionic charge ratio, merged onto a universal curve when plotted versus σM. Second, this universal TE curve increased exponentially, over four decades, with increasing σM. This behavior is consistent with a model describing a kinetic barrier for fusion of CL-DNA complexes with the endosomal membrane (Fig. 1 d), where an increase in σM lowers the barrier height. This new understanding of the fundamental role of the lipid carrier σM has led to redesigned

complexes containing DOPC mixed with the multivalent cationic lipid DOSPA or the univalent cationic lipids DOTAP and DMRIE, at a constant cationic to anionic charge ratio, merged onto a universal curve when plotted versus σM. Second, this universal TE curve increased exponentially, over four decades, with increasing σM. This behavior is consistent with a model describing a kinetic barrier for fusion of CL-DNA complexes with the endosomal membrane (Fig. 1 d), where an increase in σM lowers the barrier height. This new understanding of the fundamental role of the lipid carrier σM has led to redesigned  DOPC-based carriers with efficacy competitive with the TE of

DOPC-based carriers with efficacy competitive with the TE of  DOPE-based carriers.

DOPE-based carriers.

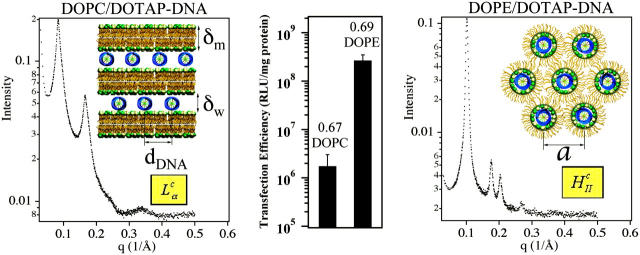

We used positively charged CL-DNA complexes prepared at ρ = DOTAP/DNA (wt./wt.) = 6 (ρ = 2.2 is the isoelectric point) from mixtures of cationic and neutral lipids complexed with plasmid DNA (pGL3). The weight ratio ρ = 6, which gave a cationic-to-anionic charge ratio of 2.8, was chosen as it corresponded to the middle of a typical plateau region observed for optimal transfection conditions as a function of increasing ρ above the isoelectric point. X-ray diffraction (XRD) results elucidated the structures of these complexes in water and in DMEM, a common environment for in vitro studies of cells. Synchrotron XRD of DOTAP/DOPC complexes at the mole fraction ΦDOPC = 0.67 (Fig. 2, left) showed sharp peaks at q001 = 0.083 Å−1, q002 = 0.166 Å−1, with a shoulder peak at q003 = 0.243 Å−1 (due to the form factor), and q004 = 0.335 Å−1, resulting from the layered structure of the  phase (d = interlayer spacing = δm+δw = 2π/q001 = 75.70 Å) with DNA intercalated between cationic lipid bilayers (Fig. 2, left, inset). For DOTAP/DOPE complexes at ΦDOPE = 0.69, XRD (Fig. 2, right) revealed four orders of Bragg peaks at q10 = 0.103 Å−1, q11 = 0.178 Å−1, q20 = 0.205 Å−1, and q21 = 0.270 Å−1, denoting the

phase (d = interlayer spacing = δm+δw = 2π/q001 = 75.70 Å) with DNA intercalated between cationic lipid bilayers (Fig. 2, left, inset). For DOTAP/DOPE complexes at ΦDOPE = 0.69, XRD (Fig. 2, right) revealed four orders of Bragg peaks at q10 = 0.103 Å−1, q11 = 0.178 Å−1, q20 = 0.205 Å−1, and q21 = 0.270 Å−1, denoting the  phase (Fig. 2, right, inset) with a unit cell spacing of

phase (Fig. 2, right, inset) with a unit cell spacing of  Except for a difference in lattice constants, the structures of CL-supercoiled DNA complexes are analogous to the ones reported recently for CL-linear DNA complexes (Koltover et al., 1998, 1999; Raedler et al., 1997; Salditt et al., 1997).

Except for a difference in lattice constants, the structures of CL-supercoiled DNA complexes are analogous to the ones reported recently for CL-linear DNA complexes (Koltover et al., 1998, 1999; Raedler et al., 1997; Salditt et al., 1997).

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of structure and transfection efficiency (TE). Left (mole fraction ΦDOPC = 0.67) shows a typical XRD scan of lamellar (inset)  complexes. Right (mole fraction ΦDOPE = 0.69) shows a typical XRD scan of inverted hexagonal (inset)

complexes. Right (mole fraction ΦDOPE = 0.69) shows a typical XRD scan of inverted hexagonal (inset)  complexes. Middle displays the corresponding TE, as measured by luciferase enzyme assays of transfected mouse L-cells.

complexes. Middle displays the corresponding TE, as measured by luciferase enzyme assays of transfected mouse L-cells.

Transfection experiments were done using plasmid DNA (pGL3), which contains the firefly luciferase reporter gene, to measure TE and its correlation to the solution structures of complexes. Mouse L-cells were transfected with CL-DNA complexes and incubated on average for at least a full cell-cycle, during which expression occurred. A standard luciferase assay allowed us to evaluate quantitatively the amount of synthesized protein by measuring the bioluminescence (number of emitted photons) in relative light units per mg of cell protein. Fig. 2 (middle) clearly demonstrates the higher TE, by more than two decades, attained by complexes in the  phase at ΦDOPE = 0.69 compared to

phase at ΦDOPE = 0.69 compared to  complexes at ΦDOPC = 0.67.

complexes at ΦDOPC = 0.67.

To further understand the structure-function correlation, we examined the transfer process of CL-DNA complexes into cells and the mechanism of the subsequent DNA release using LSCM, which provides an optical resolution of ∼0.3 μm in the x and y, and ∼3/4 μm in the z. The complexes were doubly tagged with fluorescent labels, a red one for lipid and a green covalent one for DNA. Fig. 3 shows LSCM pictures of mouse L-cells after 6 h of transfer time. By comparing images of the x-y, y-z, and x-z planes, we were able to determine the position of an object relative to a cell. Fig. 3 A shows a typical confocal image of a mouse cell transfected with  complexes at ΦDOPE = 0.69. The lipid fluorescence clearly outlines the plasma membrane, indicating fusion of lipid with the plasma membrane before or after entry through the endocytic pathway (Wrobel and Collins, 1995). An aggregate of complexes (yellow) was seen inside a cell as well as a clump of DNA (green) in the cytoplasm. The image shows that the interaction between

complexes at ΦDOPE = 0.69. The lipid fluorescence clearly outlines the plasma membrane, indicating fusion of lipid with the plasma membrane before or after entry through the endocytic pathway (Wrobel and Collins, 1995). An aggregate of complexes (yellow) was seen inside a cell as well as a clump of DNA (green) in the cytoplasm. The image shows that the interaction between  complexes and cells leads to the dissociation and release of DNA from the CL-vector consistent with the measured high TE.

complexes and cells leads to the dissociation and release of DNA from the CL-vector consistent with the measured high TE.

The corresponding confocal images with  complexes at ΦDOPC = 0.67 are shown in Fig. 3 B. In striking contrast to transfection with

complexes at ΦDOPC = 0.67 are shown in Fig. 3 B. In striking contrast to transfection with  complexes, we observed no free DNA, but rather many individual intact CL-DNA complexes inside cells. Fig. 3 B highlights one such typical complex. In the absence of fusion, complexes entered cells through endocytosis (Fig. 1). This was further substantiated in LSCM images of cells prepared at 4°C, where endocytosis is inhibited, which showed complexes attached to the outside cell surface and none within the cell body (Lin et al., 2000; Lin, 2001; Safinya et al., 2002). At ΦDOPC = 0.67, most of the DNA remained trapped by the CL-vector consistent with the measured low TE. As we discuss below, chloroquine-based experiments showed that the intact CL-DNA complexes were typically trapped within endosomes.

complexes, we observed no free DNA, but rather many individual intact CL-DNA complexes inside cells. Fig. 3 B highlights one such typical complex. In the absence of fusion, complexes entered cells through endocytosis (Fig. 1). This was further substantiated in LSCM images of cells prepared at 4°C, where endocytosis is inhibited, which showed complexes attached to the outside cell surface and none within the cell body (Lin et al., 2000; Lin, 2001; Safinya et al., 2002). At ΦDOPC = 0.67, most of the DNA remained trapped by the CL-vector consistent with the measured low TE. As we discuss below, chloroquine-based experiments showed that the intact CL-DNA complexes were typically trapped within endosomes.

As the concentration of DOPC decreased in the  CL-DNA complexes, we observed an unexpected enhancement in TE by two decades. Fig. 4 A (red diamonds) exhibits the nontrivial dependence of TE on ΦDOPC for DOPC/DOTAP-DNA complexes, which starts low for 0.5 < ΦDOPC < 0.7 and increases dramatically to a value, at ΦDOPC = 0.2, rivaling that achieved by DOPE/DOTAP-DNA complexes. Similar results were obtained for another univalent cationic lipid DMRIE (Fig. 4 A, black triangles). The key experiment, which led to a deeper understanding of TE, was a study done with the multivalent cationic lipid DOSPA (blue squares) replacing DOTAP. A qualitatively similar trend was observed with TE decreasing rapidly above a critical

CL-DNA complexes, we observed an unexpected enhancement in TE by two decades. Fig. 4 A (red diamonds) exhibits the nontrivial dependence of TE on ΦDOPC for DOPC/DOTAP-DNA complexes, which starts low for 0.5 < ΦDOPC < 0.7 and increases dramatically to a value, at ΦDOPC = 0.2, rivaling that achieved by DOPE/DOTAP-DNA complexes. Similar results were obtained for another univalent cationic lipid DMRIE (Fig. 4 A, black triangles). The key experiment, which led to a deeper understanding of TE, was a study done with the multivalent cationic lipid DOSPA (blue squares) replacing DOTAP. A qualitatively similar trend was observed with TE decreasing rapidly above a critical  , albeit with

, albeit with  shifted from ∼0.2 (observed for DOTAP and DMRIE complexes) to 0.7 ± 0.1 (DOSPA). The main difference between the cationic lipids is the notably larger charge density of DOSPA (Fig. 4 B, inset), with a larger headgroup carrying potentially up to five cationic charges. Thus, at a given ΦDOPC, the membrane charge density (σM) is significantly larger in DOSPA compared to DOTAP or DMRIE containing complexes.

shifted from ∼0.2 (observed for DOTAP and DMRIE complexes) to 0.7 ± 0.1 (DOSPA). The main difference between the cationic lipids is the notably larger charge density of DOSPA (Fig. 4 B, inset), with a larger headgroup carrying potentially up to five cationic charges. Thus, at a given ΦDOPC, the membrane charge density (σM) is significantly larger in DOSPA compared to DOTAP or DMRIE containing complexes.

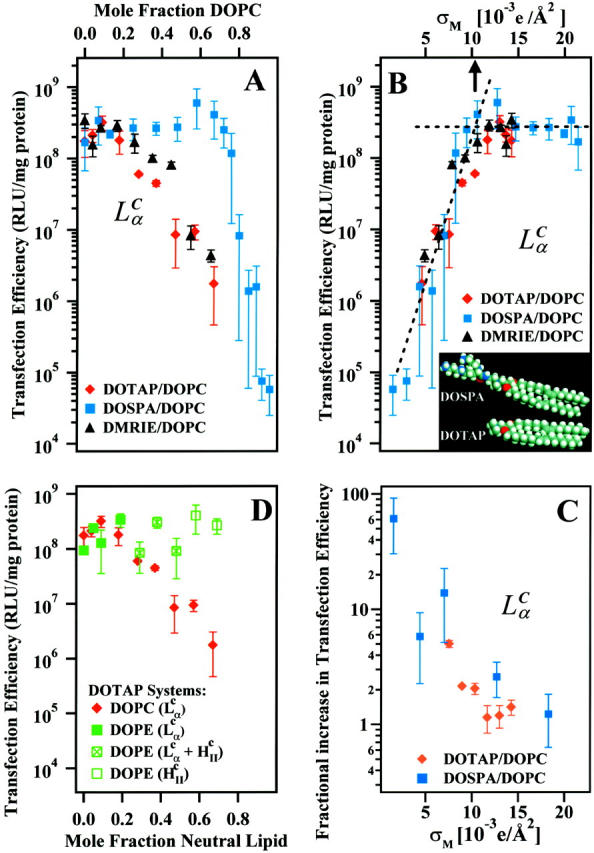

FIGURE 4.

(A) Transfection efficiency (TE) expressed as relative light units per mg total cellular protein plotted as a function of varying mole fraction DOPC with cationic lipids DOSPA, DOTAP, and DMRIE. (B) TE plotted versus the membrane charge density σM, demonstrating universal behavior of CLs containing cationic lipids with different molecular charges and headgroup areas (inset). For all three systems, TE increases with σM until an optimal  (arrow at ≈ 0.0104 e/Å2; determined by the intersection of two straight lines fit to the data (dashed lines) above and below the “knee”), at which TE plateaus. (C) The fractional increase TEchloroquine/TE for the DOSPA/DOPC and DOTAP/DOPC systems with added chloroquine as a function of σM. (D) TE plotted as a function of mole fraction of neutral lipid for the DOTAP/DOPC and the DOTAP/DOPE systems. The DOTAP/DOPC system is

(arrow at ≈ 0.0104 e/Å2; determined by the intersection of two straight lines fit to the data (dashed lines) above and below the “knee”), at which TE plateaus. (C) The fractional increase TEchloroquine/TE for the DOSPA/DOPC and DOTAP/DOPC systems with added chloroquine as a function of σM. (D) TE plotted as a function of mole fraction of neutral lipid for the DOTAP/DOPC and the DOTAP/DOPE systems. The DOTAP/DOPC system is  . The DOTAP/DOPE system goes through two phase transitions:

. The DOTAP/DOPE system goes through two phase transitions:  (filled green square) to coexisting

(filled green square) to coexisting  (green square with cross) to

(green square with cross) to  (open green square). All transfection measurements were done with 2 μg of plasmid DNA at a constant cationic to anionic charge ratio of 2.8. (2.8 was chosen as it corresponded to the middle of a typical plateau region observed for optimal transfection conditions as a function of increasing cationic to anionic charge ratio above the isoelectric point of the complex.) Thus, every TE data point of A and B (which is found to vary by nearly four orders of magnitude) used the same amount of total charged species (anionic charge from DNA, cationic charge from cationic lipid) and the membrane charge density of CL-DNA complexes (σM) was varied by varying the amount of neutral lipid.

(open green square). All transfection measurements were done with 2 μg of plasmid DNA at a constant cationic to anionic charge ratio of 2.8. (2.8 was chosen as it corresponded to the middle of a typical plateau region observed for optimal transfection conditions as a function of increasing cationic to anionic charge ratio above the isoelectric point of the complex.) Thus, every TE data point of A and B (which is found to vary by nearly four orders of magnitude) used the same amount of total charged species (anionic charge from DNA, cationic charge from cationic lipid) and the membrane charge density of CL-DNA complexes (σM) was varied by varying the amount of neutral lipid.

We show in Fig. 4 B the same TE data of Fig. 4 A, now plotted versus the membrane charge density σM (i.e., the average charge per unit area of the cationic membrane):

|

(1) |

Here, Nnl and Ncl are the number of neutral and cationic lipids, respectively; r = Acl/Anl is the ratio of the headgroup area of the cationic to neutral lipid; σcl = eZ/Acl is the charge density of the cationic lipid with valence Z; and Φnl = Nnl/(Nnl + Ncl) and Φcl = Ncl/(Nnl + Ncl) are the mole fractions of the neutral and cationic lipids, respectively. For the plots in Fig. 4 B, we used Anl = 70 Å (Langmuir trough data), rDOTAP = rDMRIE = 1, rDOSPA = 2, ZDOTAP = ZDMRIE = 1, and ZDOSPA= 3. We found that values of ZDOSPA between 3 and 4 yield a good visual fit for the comparison between DOTAP and DOSPA while 2 and 5 clearly do not. For environments of neutral pH we expect ZDOSPA to be closer to 4. The value of ZDOSPA could be regarded as a fitting parameter in the range between 3 and 4. Remarkably, given the complexity of the CL-DNA-cell system, the data, spread out when plotted as a function of Φnl (Fig. 4 A), coalesce into a “universal” curve as a function of σM, with TE varying exponentially over nearly four decades as σM increases by a factor of ≈ 8 (Fig. 4 B, σM between 0.0015 e/Å2 and 0.012 e/Å2), clearly demonstrating that σM is a key universal parameter for transfection with lamellar  CL-vectors. We now observe a single optimal

CL-vectors. We now observe a single optimal  ) (Fig. 4 B, arrow) where the universal TE curve saturates for

) (Fig. 4 B, arrow) where the universal TE curve saturates for  for both univalent and multivalent cationic lipid-containing CL-vectors. σM controls the average DNA interaxial spacing dDNA (Fig. 2, inset), which decreases as σM increases (Koltover et al., 1999; Raedler et al., 1997). Future designs of CL-vectors, which further enhance the packing of DNA based on the recent theoretical understanding of intermolecular interactions within the complex (Bruinsma, 1998; Harries et al., 1998; O'Hern and Lubensky, 1998), may be expected to enhance TE.

for both univalent and multivalent cationic lipid-containing CL-vectors. σM controls the average DNA interaxial spacing dDNA (Fig. 2, inset), which decreases as σM increases (Koltover et al., 1999; Raedler et al., 1997). Future designs of CL-vectors, which further enhance the packing of DNA based on the recent theoretical understanding of intermolecular interactions within the complex (Bruinsma, 1998; Harries et al., 1998; O'Hern and Lubensky, 1998), may be expected to enhance TE.

The TE data suggest vastly diverse behaviors of  CL-DNA complexes between low and high σM. As we discussed earlier, for low σM = e/(200 Å2) where TE is low, confocal images show DNA locked within complexes after endocytosis (Fig. 3 B). To test the idea that it is the endosomal vesicle that traps the complex, we carried out transfection experiments in the presence of chloroquine, a well-established bio-assay known to enhance the release of trapped material within endosomes by osmotically bursting the vesicle. The endocytic pathway involves the fusion of endosomes with lysosomes (vesicles containing enzymes for degradation of material within endosomes) leading to late-stage endosomes, limiting the time available for CL-DNA complexes to escape. Chloroquine, a weak base, penetrates the lysosome and accumulates in a charged state; thus, lysosomes and late-stage endosomes tend to rupture due to increased osmotic pressure caused by counterions rushing in (Voet and Voet, 1995).

CL-DNA complexes between low and high σM. As we discussed earlier, for low σM = e/(200 Å2) where TE is low, confocal images show DNA locked within complexes after endocytosis (Fig. 3 B). To test the idea that it is the endosomal vesicle that traps the complex, we carried out transfection experiments in the presence of chloroquine, a well-established bio-assay known to enhance the release of trapped material within endosomes by osmotically bursting the vesicle. The endocytic pathway involves the fusion of endosomes with lysosomes (vesicles containing enzymes for degradation of material within endosomes) leading to late-stage endosomes, limiting the time available for CL-DNA complexes to escape. Chloroquine, a weak base, penetrates the lysosome and accumulates in a charged state; thus, lysosomes and late-stage endosomes tend to rupture due to increased osmotic pressure caused by counterions rushing in (Voet and Voet, 1995).

The fractional increase (TEchloroquine/TE) for the DOSPA/DOPC and DOTAP/DOPC systems with added chloroquine as a function of σM (Fig. 4 C) shows the large increase in TE by as much as a factor of 60 as σM decreases and indicates that at low σM lamellar  complexes are trapped within endosomes, consistent both with the confocal images (Fig. 3 B) and the measured low TE without chloroquine. At high σM, chloroquine has a much smaller effect on TE with the fractional increase of order 1, implying that endosomal entrapment is not a significant limiting factor.

complexes are trapped within endosomes, consistent both with the confocal images (Fig. 3 B) and the measured low TE without chloroquine. At high σM, chloroquine has a much smaller effect on TE with the fractional increase of order 1, implying that endosomal entrapment is not a significant limiting factor.

The comparison between DOTAP/DOPC-DNA and DOTAP/DOPE-DNA complexes is shown plotted in Fig. 4 D. At high ΦDOPE > 0.56, DOTAP/DOPE-DNA complexes are in the  phase (green open squares) and exhibit high TE. We further see that in contrast to DOPC containing complexes, which show a strong dependence on the mole fraction of neutral lipid (or equivalently σM), TE of DOPE containing complexes is independent of σM. The data show unambiguously that σM is a critical parameter for TE by

phase (green open squares) and exhibit high TE. We further see that in contrast to DOPC containing complexes, which show a strong dependence on the mole fraction of neutral lipid (or equivalently σM), TE of DOPE containing complexes is independent of σM. The data show unambiguously that σM is a critical parameter for TE by  complexes and not so for

complexes and not so for  complexes. The mechanism of transfection by DOPE containing

complexes. The mechanism of transfection by DOPE containing  complexes is independent of σM and dominated by other effects; possibly, for example, the known fusogenic properties of inverted hexagonal phases. In contrast, for

complexes is independent of σM and dominated by other effects; possibly, for example, the known fusogenic properties of inverted hexagonal phases. In contrast, for  complexes, high TE requires

complexes, high TE requires  Thus, to produce a high TE of

Thus, to produce a high TE of  complexes with large mole fraction of neutral lipid ∼0.70 (i.e., similar to those mole fractions where DOPE containing

complexes with large mole fraction of neutral lipid ∼0.70 (i.e., similar to those mole fractions where DOPE containing  complexes show high TE) requires the incorporation of multivalent cationic lipids (e.g., DOSPA) to ensure that

complexes show high TE) requires the incorporation of multivalent cationic lipids (e.g., DOSPA) to ensure that  .

.

LSCM images of cells transfected with  complexes at high σM displayed a path of complex uptake and DNA release distinct from transfections done with both

complexes at high σM displayed a path of complex uptake and DNA release distinct from transfections done with both  complexes at low σM (Fig. 3 B) and

complexes at low σM (Fig. 3 B) and  complexes (Fig. 3 A). A typical confocal image with

complexes (Fig. 3 A). A typical confocal image with  complexes at ΦDOPC = 0.18 (σM ≈ 0.012 e/Å2) is shown in Fig. 5. Intact complexes were found inside the cell (Fig. 5, label 2 in x-y plane; box 2 shows the equal green (DNA) and red (lipid) fluorescence intensity along the dotted line in x-y; see inset), but more interestingly, a mass of exogenous DNA successfully transferred into the cytoplasm was also clearly evident (Fig. 5, label 1 in x-y plane; box 1 shows the much larger green fluorescence (DNA) intensity along the x-y direction). In the absence of fusion, high σM complexes enter cells through endocytosis. The integrated fluorescence intensity of the observed DNA (Fig. 5, box 1) is comparable to that of DNA complexed with lipids (Fig. 5, box 2), indicating that the released DNA is in the form of aggregates. Because endosomes contain no known DNA-condensing agent, these aggregates must reside in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1 e). The presence of lipid-released DNA in the cytoplasm after endocytic uptake of complexes agrees with the measured high TE, and moreover, implies fusion between CL-DNA lipids and endosomal membranes (Fig. 1 d), enabling escape from the endosomes. This is consistent with our finding that chloroquine has a small effect at high σM because endosomal escape is no longer a major obstacle.

complexes at ΦDOPC = 0.18 (σM ≈ 0.012 e/Å2) is shown in Fig. 5. Intact complexes were found inside the cell (Fig. 5, label 2 in x-y plane; box 2 shows the equal green (DNA) and red (lipid) fluorescence intensity along the dotted line in x-y; see inset), but more interestingly, a mass of exogenous DNA successfully transferred into the cytoplasm was also clearly evident (Fig. 5, label 1 in x-y plane; box 1 shows the much larger green fluorescence (DNA) intensity along the x-y direction). In the absence of fusion, high σM complexes enter cells through endocytosis. The integrated fluorescence intensity of the observed DNA (Fig. 5, box 1) is comparable to that of DNA complexed with lipids (Fig. 5, box 2), indicating that the released DNA is in the form of aggregates. Because endosomes contain no known DNA-condensing agent, these aggregates must reside in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1 e). The presence of lipid-released DNA in the cytoplasm after endocytic uptake of complexes agrees with the measured high TE, and moreover, implies fusion between CL-DNA lipids and endosomal membranes (Fig. 1 d), enabling escape from the endosomes. This is consistent with our finding that chloroquine has a small effect at high σM because endosomal escape is no longer a major obstacle.

The confocal image also captured an aggregate of complexes in contact with a large area of the cell surface, displaying no tendency toward fusion with the plasma membrane (Fig. 5, label 3 in x-y plane). Comparing the changes in fluorescence intensity along the x-y (Fig. 5, box 3) and z (Fig. 5, box 4) directions, from the outside toward the inside of the cell, we clearly see an aggregate of complexes caught in the process of dissociation after endocytosis, with released DNA toward the inside of the cell.

Model of cell entry by lamellar  CL-DNA complexes

CL-DNA complexes

The combined LSCM and TE data lead us to propose a model of cellular entry via  CL carriers. Optical images show no evidence of fusion with the plasma membrane, suggesting that

CL carriers. Optical images show no evidence of fusion with the plasma membrane, suggesting that  complexes enter via the endocytic pathway. Chloroquine data imply that complexes with low σM are trapped within the endosome, but increasing σM enables endosomal escape. For

complexes enter via the endocytic pathway. Chloroquine data imply that complexes with low σM are trapped within the endosome, but increasing σM enables endosomal escape. For  , the universal TE curve (Fig. 4 B) shows TE increasing exponentially as a function of σM. This suggests a simple model of activated fusion of complexes with endosomal vesicles where TE is proportional to the rate of fusion:

, the universal TE curve (Fig. 4 B) shows TE increasing exponentially as a function of σM. This suggests a simple model of activated fusion of complexes with endosomal vesicles where TE is proportional to the rate of fusion:

|

(2) |

with δE = energy barrier height = a × κ – b × σM. Here, a,b > 0 are numerical constants, and τ −1 is the collision rate between the trapped CL-DNA particle and the endosomal wall (Fig. 1 c). The first term gives the main barrier to fusion as originating from the membrane bending rigidity κ (Fig. 1 d, arrows in expanded view). A recent theoretical model (Gompper and Goos, 1995), which considers fusion between two neutral lipid bilayers (i.e., forming wormholes), has found that the main energy barrier against fusion is proportional to κ. These authors find that the density of fusion-induced passages (wormholes) between two neutral membranes decreases rapidly with increasing κ. The second term describes the fact that because the fusing membranes are oppositely charged (the endosomal membrane is comprised of negative lipids and anionic cell-surface sulfated proteoglycans), the electrostatic attraction favors membrane adhesion and a lower energy barrier as σM increases (Fig. 1 c, arrows in expanded view). A future full theoretical calculation should also include the membrane Gaussian modulus κG and the possibility of an induced negative spontaneous radius of curvature (enhancing fusion) due to interactions between DNA rods and the lipid layer (P.G. De Gennes, private communication).

Interactions between inverted hexagonal  CL-DNA complexes and cells, and comparisons with lamellar complexes

CL-DNA complexes and cells, and comparisons with lamellar complexes

The striking difference between transfection by  versus

versus  complexes is that for the former, transfection efficiency is independent of the membrane charge density σM (of course, as long as the CL-DNA complex is overall positively charged; see Fig. 4 D). Thus, another mechanism, which is independent of σM, must dominate the interaction between

complexes is that for the former, transfection efficiency is independent of the membrane charge density σM (of course, as long as the CL-DNA complex is overall positively charged; see Fig. 4 D). Thus, another mechanism, which is independent of σM, must dominate the interaction between  complexes and cells. Confocal imaging shows that

complexes and cells. Confocal imaging shows that  complexes appear to rapidly fuse with cell membranes (Fig. 3 A). The lipid fluorescence, which outlines the plasma membrane in Fig. 3 A, indicates fusion of lipids of

complexes appear to rapidly fuse with cell membranes (Fig. 3 A). The lipid fluorescence, which outlines the plasma membrane in Fig. 3 A, indicates fusion of lipids of  complexes with the plasma membrane, which may have occurred before or after entry through the endocytic pathway. The image shows that the interaction between

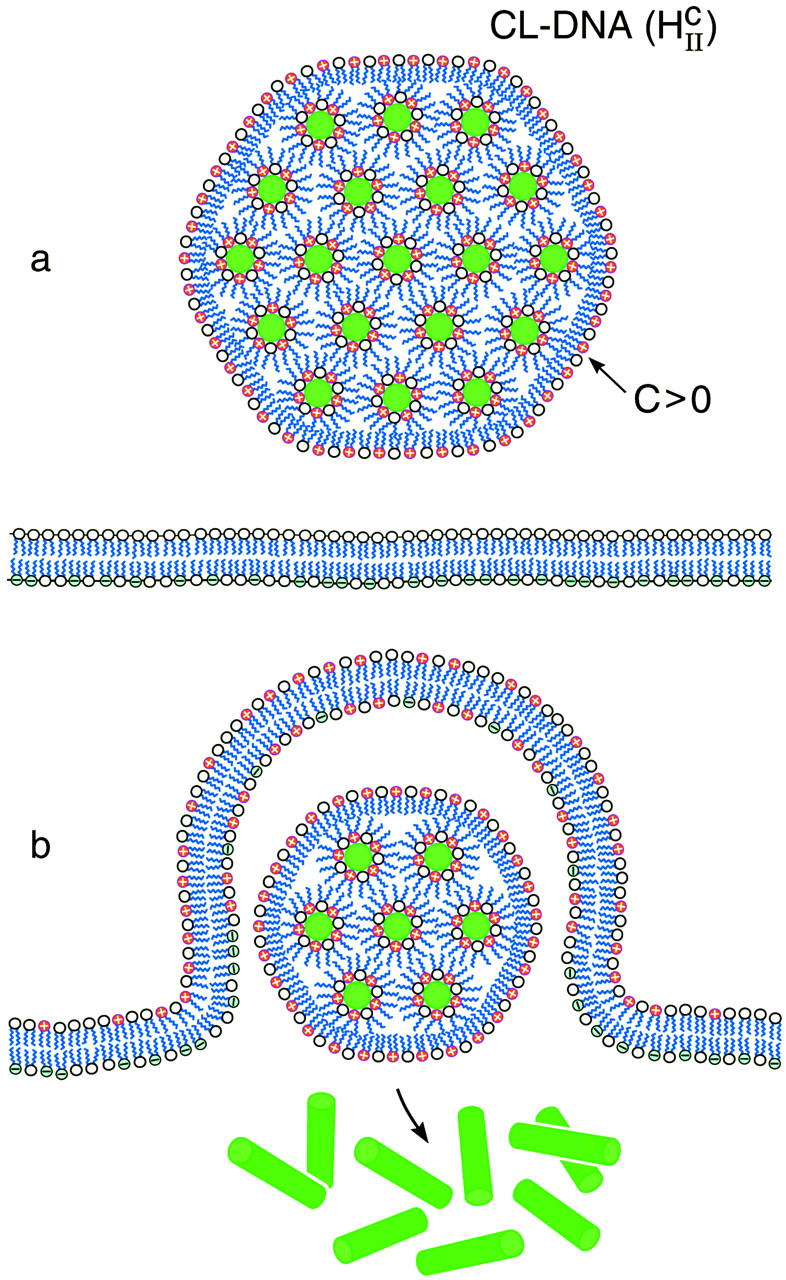

complexes with the plasma membrane, which may have occurred before or after entry through the endocytic pathway. The image shows that the interaction between  complexes and cells leads to the dissociation and release of DNA from the CL-vector consistent with the measured high TE. One mechanism, which may be responsible for the rapid fusion, is shown schematically in Fig. 6. In the top part of Fig. 6 a, a

complexes and cells leads to the dissociation and release of DNA from the CL-vector consistent with the measured high TE. One mechanism, which may be responsible for the rapid fusion, is shown schematically in Fig. 6. In the top part of Fig. 6 a, a  complex is shown approaching either the plasma or endosomal membrane. For simplicity, the cell-surface proteoglycans (similar to Fig.1) which are present are not depicted. One can see that the outer most lipid monolayer, which must cover the

complex is shown approaching either the plasma or endosomal membrane. For simplicity, the cell-surface proteoglycans (similar to Fig.1) which are present are not depicted. One can see that the outer most lipid monolayer, which must cover the  complex due to the hydrophobic effect, is at an opposite curvature to that of the preferred negative curvature of the lipids coating DNA inside the complex. This elastically frustrated state of the outer monolayer (which is independent of σM) would then drive the rapid fusion, with the plasma or endosomal membrane leading to release of a layer of DNA and a smaller

complex due to the hydrophobic effect, is at an opposite curvature to that of the preferred negative curvature of the lipids coating DNA inside the complex. This elastically frustrated state of the outer monolayer (which is independent of σM) would then drive the rapid fusion, with the plasma or endosomal membrane leading to release of a layer of DNA and a smaller  complex as shown in the bottom part of Fig. 6 b. This process would then repeat itself rapidly (e.g., through interactions of the outer layer lipids of the smaller complex with anionic biomolecules of the cell) leading to the release of much of the remaining DNA from the complex.

complex as shown in the bottom part of Fig. 6 b. This process would then repeat itself rapidly (e.g., through interactions of the outer layer lipids of the smaller complex with anionic biomolecules of the cell) leading to the release of much of the remaining DNA from the complex.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic sketch of an inverted hexagonal CL-DNA complex interacting with either the plasma membrane or the endosomal membrane (a). For simplicity, the cell-surface proteoglycans, which are present in the membrane bilayer have been left out (see Fig. 1). The outer lipid monolayer covering the  CL-DNA complex has a positive curvature (C > 0) whereas the desired curvature for cationic lipid monolayers coating DNA within the complex of the inverted hexagonal phase is negative. The outer lipid layer is thus energetically costly, which would result in a driving force, independent of the cationic membrane charge density, for rapid fusion of the

CL-DNA complex has a positive curvature (C > 0) whereas the desired curvature for cationic lipid monolayers coating DNA within the complex of the inverted hexagonal phase is negative. The outer lipid layer is thus energetically costly, which would result in a driving force, independent of the cationic membrane charge density, for rapid fusion of the  complex with the bilayer of the cell plasma membrane or the endosomal membrane as sketched in b.

complex with the bilayer of the cell plasma membrane or the endosomal membrane as sketched in b.

By comparison, the bilayers of lamellar  complexes are inherently more stable and the onionlike (lipid-bilayer/DNA-monolayer) complex having left the endosome after fusion (Fig. 1 d, expanded view shows release of a layer of DNA and a smaller complex within the cytoplasm), is expected to peel, layer-by-layer, much more slowly through interactions of the cationic membranes with anionic components of the cell such as the predominantly anionic cytoskeletal filaments (Wong et al., 2000). In the high transfection regime, for both

complexes are inherently more stable and the onionlike (lipid-bilayer/DNA-monolayer) complex having left the endosome after fusion (Fig. 1 d, expanded view shows release of a layer of DNA and a smaller complex within the cytoplasm), is expected to peel, layer-by-layer, much more slowly through interactions of the cationic membranes with anionic components of the cell such as the predominantly anionic cytoskeletal filaments (Wong et al., 2000). In the high transfection regime, for both  and

and  complexes, confocal microscopy reveals the dissociation of lipid and DNA (Figs. 3 A and 5). However, the exogenous DNA, which has been released from the complex, is in a condensed state. The DNA aggregates visible in the confocal images support the hypothesis that the exogenous DNA has been condensed with oppositely charged condensing agents from the cytoplasm as depicted schematically in Fig. 1 e.

complexes, confocal microscopy reveals the dissociation of lipid and DNA (Figs. 3 A and 5). However, the exogenous DNA, which has been released from the complex, is in a condensed state. The DNA aggregates visible in the confocal images support the hypothesis that the exogenous DNA has been condensed with oppositely charged condensing agents from the cytoplasm as depicted schematically in Fig. 1 e.

CONCLUSIONS

We have identified the membrane charge density of the CL-vector (i.e., the average charge per unit area of the membrane, σM) as a key universal parameter that governs the transfection efficiency (TE) behavior of  complexes in cells. In contrast to

complexes in cells. In contrast to  complexes,

complexes,  complexes exhibit no dependence on σM (Fig. 4 D). This demonstrates a structural basis (

complexes exhibit no dependence on σM (Fig. 4 D). This demonstrates a structural basis (  versus

versus  ) for the dependence of transfection efficiency on a physical-chemical parameter (σM) of CL-DNA complexes. The importance of the nanostructure of CL-DNA complexes to transfection mechanisms is further underscored in confocal microscopy images showing distinct pathways and interactions with cells for

) for the dependence of transfection efficiency on a physical-chemical parameter (σM) of CL-DNA complexes. The importance of the nanostructure of CL-DNA complexes to transfection mechanisms is further underscored in confocal microscopy images showing distinct pathways and interactions with cells for  and

and  complexes and also for

complexes and also for  complexes with low and high σM.

complexes with low and high σM.

The claim that σM is a universal parameter for TE results from the observation that while TE magnitudes for univalent versus multivalent cationic lipids are different at the same values of the mole fraction of the neutral lipid (Fig. 4 A), the magnitudes are equal (within the experimental error bars), when the comparison is made at the same value of σM (Fig. 4 B). Previous work by others has typically focused on optimizing transfection efficiency as a function of increasing cationic lipid-to-DNA charge ratio (Boussif et al., 1995; Chesnoy and Huang, 2000; Mahato and Kim, 2002; Miller, 1998; Singhal and Huang, 1994). What is remarkable about what we report in this article is that all transfection efficiency measurements were done with 2 μg of plasmid DNA at a constant cationic-to-anionic charge ratio of 2.8 (chosen as it corresponded to the middle of a typical plateau region observed for optimal transfection conditions as a function of increasing cationic-to-anionic charge ratio above the isoelectric point of the complex). Thus, the nearly four orders-of-magnitude increase observed in the universal transfection curve (Fig. 4 B) occurs under the condition where each data point contains the same amount of cationic charge from cationic lipid and anionic charge from DNA, and the variation in σM is achieved simply by varying the amount of neutral lipid.

The universal TE curve for  complexes reveals a critical membrane charge density (

complexes reveals a critical membrane charge density ( ) where

) where  complexes with

complexes with  achieve high TE competitive with

achieve high TE competitive with  complexes. Thus, for example, to produce a high TE of

complexes. Thus, for example, to produce a high TE of  complexes with large mole fractions of the neutral lipid requires the use of a multivalent cationic lipid such as DOSPA to ensure that

complexes with large mole fractions of the neutral lipid requires the use of a multivalent cationic lipid such as DOSPA to ensure that  . Previous to what we report here, it was thought that one could not make a high TE

. Previous to what we report here, it was thought that one could not make a high TE  complex with such large mole fractions of DOPC. In principle, extremely large mole fractions of neutral helper lipid may be incorporated within an

complex with such large mole fractions of DOPC. In principle, extremely large mole fractions of neutral helper lipid may be incorporated within an  complex with the retention of high TE if the condition of

complex with the retention of high TE if the condition of  is satisfied with the use of the appropriate multivalent cationic lipid. Recent work has shown such behavior with high TE

is satisfied with the use of the appropriate multivalent cationic lipid. Recent work has shown such behavior with high TE  complexes with 0.80 mol fraction of DOPC and 0.20 mol fraction of a new multivalent cationic lipid, MVL5 (Ewert et al., 2002).

complexes with 0.80 mol fraction of DOPC and 0.20 mol fraction of a new multivalent cationic lipid, MVL5 (Ewert et al., 2002).

Before what we describe in our article, it was assumed that inverted hexagonal  complexes always transfect much more efficiently than lamellar

complexes always transfect much more efficiently than lamellar  complexes. Our work has led us to redesigned

complexes. Our work has led us to redesigned  complexes, which easily compete with the high TE of

complexes, which easily compete with the high TE of  complexes, even in the presence of large mole fractions of order 0.70 DOPC (Fig. 4 A, DOSPA/DOPC complexes). This is a very significant result with respect to opening up an alternative lamellar instead of inverted hexagonal structure for gene transfection applications. First, the lamellar phase is by far the most common structure of CL-DNA complexes. For example, published data on high transfecting inverted hexagonal phase complexes almost always contain the neutral-lipid DOPE or a PE-based lipid, and even then, only in a narrow concentration regime (Koltover et al., 1998). In contrast, the vast majority of non-PE-based neutral lipids, when complexed with cationic lipids, lead to the

complexes, even in the presence of large mole fractions of order 0.70 DOPC (Fig. 4 A, DOSPA/DOPC complexes). This is a very significant result with respect to opening up an alternative lamellar instead of inverted hexagonal structure for gene transfection applications. First, the lamellar phase is by far the most common structure of CL-DNA complexes. For example, published data on high transfecting inverted hexagonal phase complexes almost always contain the neutral-lipid DOPE or a PE-based lipid, and even then, only in a narrow concentration regime (Koltover et al., 1998). In contrast, the vast majority of non-PE-based neutral lipids, when complexed with cationic lipids, lead to the  phase (Ewert et al., 2002; Safinya, 2001; Koltover et al., 1999 and 1998; Lasic et al., 1997; Raedler et al., 1997). Thus, by enabling the high efficiency of

phase (Ewert et al., 2002; Safinya, 2001; Koltover et al., 1999 and 1998; Lasic et al., 1997; Raedler et al., 1997). Thus, by enabling the high efficiency of  complexes (including those containing significant amounts of the neutral lipid DOPC), a broad variety of lipids and lipid-mixtures, which may have other desired properties (e.g., with peptide headgroups for trafficking of complexes to desired intracellular locations), will be available for gene transfection applications. Second, it is known that DOPE containing inverted hexagonal

complexes (including those containing significant amounts of the neutral lipid DOPC), a broad variety of lipids and lipid-mixtures, which may have other desired properties (e.g., with peptide headgroups for trafficking of complexes to desired intracellular locations), will be available for gene transfection applications. Second, it is known that DOPE containing inverted hexagonal  complexes work well in in vitro applications but they do not transfect efficiently in systemic applications because they tend to aggregate in blood due to the hydrophobic effect (Chesnoy and Huang, 2000). The majority of in vivo gene transfection protocols currently on going, which are very inefficient due to the presence of serum or extracellular matrix components, contain cholesterol as the neutral-lipid component (which leads to

complexes work well in in vitro applications but they do not transfect efficiently in systemic applications because they tend to aggregate in blood due to the hydrophobic effect (Chesnoy and Huang, 2000). The majority of in vivo gene transfection protocols currently on going, which are very inefficient due to the presence of serum or extracellular matrix components, contain cholesterol as the neutral-lipid component (which leads to  phase complexes), and are more stable in blood.

phase complexes), and are more stable in blood.

The universal TE curve for DOPC-containing  complexes increases exponentially with σM for

complexes increases exponentially with σM for  (an optimal membrane charge density), and saturates for

(an optimal membrane charge density), and saturates for  . The limiting saturated TE level of

. The limiting saturated TE level of  complexes is comparable to the high TE of DOPE-containing

complexes is comparable to the high TE of DOPE-containing  complexes. In the high yet saturated TE regime, for both

complexes. In the high yet saturated TE regime, for both  and

and  complexes, confocal microscopy reveals the dissociation of lipid and DNA. However, the lipid-released DNA is in a condensed state (Figs. 3 A and 5). Because DNA is strongly negatively charged, condensation can only occur if it combines with oppositely charged condensing agents from the cytoplasm, such as spermine and histones, which become available during the cell cycle in millimolar concentration levels (Bloomfield, 1991). Although DNA strands covering the surface of the condensed DNA mass or isolated from it are most likely transcriptionally active, much of the observed bulk of condensed DNA may be transcriptionally inactive and may determine the current limiting factor to transfection by cationic lipid vectors.

complexes, confocal microscopy reveals the dissociation of lipid and DNA. However, the lipid-released DNA is in a condensed state (Figs. 3 A and 5). Because DNA is strongly negatively charged, condensation can only occur if it combines with oppositely charged condensing agents from the cytoplasm, such as spermine and histones, which become available during the cell cycle in millimolar concentration levels (Bloomfield, 1991). Although DNA strands covering the surface of the condensed DNA mass or isolated from it are most likely transcriptionally active, much of the observed bulk of condensed DNA may be transcriptionally inactive and may determine the current limiting factor to transfection by cationic lipid vectors.

A final important observation is that the work that we have described here should apply to transfection optimization in ex vivo cell transfection, where cells are removed and returned to patients after transfection. In particular, the results of this article should aid clinical efforts to develop efficient CL-vector cancer vaccines in ex vivo applications. However, the current work is not expected to be predictive of transfection behavior in blood for systemic in vivo applications in the presence of serum. Future studies should reveal other types of well-defined structure-function correlations for transfection in vivo in the presence of serum.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge insightful discussions with R. Bruinsma. We have benefited from numerous discussions with Phillip Felgner and Leaf Huang over the last few years. DOSPA and DMRIE were gifts from Phillip Felgner, for which we are extremely grateful.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM-59288, AI-20611, and AI-12520. The x-ray diffraction experiments, which were supported in part by National Science Foundation grant DMR-0203755, were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (supported by the Department of Energy). The Materials Research Laboratory at University of California at Santa Barbara is supported by National Science Foundation grant DMR-0080034.

Alison J. Lin and Nelle L. Slack contributed equally to this work.

References

- Alper, J. 2002. Drug delivery: breaching the membrane. Science. 294:1638–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield, V. 1991. Condensation of DNA by multivalent cations: consideration on mechanism. Biopolymers. 31:1471–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussif, O., F. Lezoulach, M. A. Zanta, M. D. Mergny, D. Scherman, B. Demeneix, and J.-P. Behr. 1995. A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:7297–7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma, R. 1998. Electrostatics of DNA-cationic lipid complexes: isoelectric instability. European Phys. J. B. 4:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Chesnoy, S., and L. Huang. 2000. Structure and function of lipid-DNA complexes for gene delivery. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29:27–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P. R., and E. M. Hersh. 1999. Cationic lipid mediated gene transfer. Curr. Op. Mol. Therap. 1:158–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, K., A. Ahmad, H. M. Evans, H.-W. Schmidt, and C. R. Safinya. 2002. Efficient synthesis and cell transfection properties of a new multivalent cationic lipid for non-viral gene delivery. J. Med. Chem. 45:5023–5029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhood, H., N. Serbina, and L. Huang. 1995. The role of dioleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine in cationic liposome mediated gene transfer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1235:289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felgner, P. L., T. R. Gadek, M. Holm, R. Roman, H. W. Chan, M. Wenz, J. P. Northrop, J. M. Ringold, and M. Danielsen. 1987. Lipofectin: a highly efficient lipid-mediated DNA transfection procedure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:7413–7417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber, D. 2001. Gene therapy: safer and virus-free? Science. 294:1638–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gompper, G., and J. Goos. 1995. Fluctuations and phase behavior of passages in a stack of fluid membranes. J. Phys. II. 5:621–634. [Google Scholar]

- Harries, D., S. May, W. M. Gelbart, and A. Ben-Shaul. 1998. Structure, stability, and thermodynamics of lamellar DNA-lipid complexes. Biophys. J. 75:159–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry, C. M. 2001. Gene delivery—without viruses. Chem. Eng. News. 79:35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, S., M. Langner, Y. Zhao, P. Ross, E. Hurley, and K. Chan. 1996. The role of helper lipids in cationic liposome-mediated gene transfer. Biophys. J. 71:590–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltover, I., T. Salditt, J. O. Raedler, and C. R. Safinya. 1998. An inverted hexagonal phase of cationic liposome-DNA complexes related to DNA release and delivery. Science. 281:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltover, I., T. Salditt, and C. R. Safinya. 1999. Phase diagram, stability, and overcharging of lamellar cationic lipid-DNA self-assembled complexes. Biophys. J. 77:915–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labat-Moleur F., A.-M. Steffan, C. Brisson, H. Perron, O. Feugeas, P. Furstenberger, F. Oberling, E. Brambilla, and J.-P. Behr. 1996. An electron microscopy study into the mechanism of gene transfer with lipopolyamines. Gene Therapy. 3:1010–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasic, D. D., H. H. Strey, M. C. A. Stuart, R. Podgornik, and P. M. Frederik. 1997. The structure of DNA-liposome complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119:832–833. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, A. J. 2001. Optimization of non-viral cationic lipid carriers in gene delivery. Ph.D. thesis. University of California, Santa Barbara, CA.

- Lin, A. J., N. L. Slack, A. Ahmad, I. Koltover, C. X. George, C. E. Samuel, and C. R. Safinya. 2000. Structure and structure-function studies of lipid/plasmid DNA complexes. J. Drug Target. 8:13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahato, R. I., and S. W. Kim, editors. 2002. Pharmaceutical Perspectives of Nucleic Acid-Based Therapeutics. Taylor and Francis, London and New York.

- Marshall, E. 2000. Biomedicine:gene therapy on trial. Science. 288:951–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, E. 2002. News of the week: gene therapy a suspect in leukemia-like disease. Science. 298:34–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A. D. 1998. Cationic liposomes for gene delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 37:1768–1785. [Google Scholar]

- Mislick, K. A., and J. D. Baldeschwieler. 1996. Evidence for the role of proteoglycans in cation-mediated gene transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:12349–12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabel, G., E. Nabel, Z. Yang, B. Fox, G. Plautz, X. Gao, L. Huang, S. Shu, D. Gordon, and A. Chang. 1993. Direct gene transfer with DNA-liposome complexes in melanoma: expression, biologic activity, and lack of toxicity in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90:11307–11311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hern, C. S., and T. C. Lubensky. 1998. Sliding columnar phase of DNA-lipid complexes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80:4335–4348. [Google Scholar]

- Raedler, J. O., I. Koltover, T. Salditt, and C. R. Safinya. 1997. Structure of DNA-cationic liposome complexes: DNA intercalation in multilamellar membranes in distinct interhelical packing regimes. Science. 275:810–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart, J., E. Hersh, B. Issell, P. Triozzi, W. Buhles, and J. Neidhart. 1997. Phase 1 trial of recombinant human interleukin-1-β (rhIL-1-β), carboplatin, and etoposide in patients with solid cancers: Southwest Oncology Group Study 8940. Cancer Invest. 15:403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safinya, C. R. 2001. Structures of lipid-DNA complexes: supramolecular assembly and gene delivery. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11:440–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safinya, C. R., A. J. Lin, N. L. Slack, and I. Koltover. 2002. Structure and structure-activity correlations of cationic lipid/DNA complexes: supramolecular assembly and gene delivery. In Pharmaceutical Perspectives of Nucleic Acid-Based Therapeutics. R. I. Mahato and S. W. Kim, editors. Taylor & Francis, London. pp. 190–209.

- Salditt, T., I. Koltover, J. O. Raedler, and C. R. Safinya. 1997. Two-dimensional smectic ordering of linear DNA chains in self-assembled DNA-cationic liposome mixtures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79:2582–2585. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, A., and L. Huang. 1994. In Gene Therapeutics: Methods and Applications of Direct Gene Transfer. J. A. Wolf, editor. Birkhauser, Boston, Massachusetts.

- Slack, N. L. 2000. Structure and function studies of cationic lipid non-viral gene delivery systems. Ph.D. thesis. University of California, Santa Barbara, CA.

- Stopeck, A. T., E. M. Hersh, J. L. Brailey, P. R. Clark, J. Norman, and S. E. Parker. 1998. Transfection of primary tumor cells and tumor cell lines with plasmid DNA/lipid complexes. Cancer Gene Ther. 5:119–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voet, D., and J. Voet. 1995. Biochemistry, 2nd Ed. Wiley, New York.

- Wilard, H. F. 2000. Genomics and gene therapy: artificial chromosomes coming to life. Science. 290:1308–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, G. C. L., J. X. Tang, A. Lin, Y. Li, P. A. Janmey, and C. R. Safinya. 2000. Hierarchical self-assembly of f-actin and cationic lipid complexes: stacked three-layer tubule networks. Science. 288: 2035–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel, I., and D. Collins. 1995. Fusion of cationic liposomes with mammalian cells occurs after endocytosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1235:296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabner, J., A. J. Fasbender, T. Moninger, K. A. Poellinger, and M. J. Welsh. 1995. Cellular and molecular barriers to gene transfer by a cationic lipid. J. Biol. Chem. 270:18997–19007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]