Abstract

Filarial infections have been associated with the development of a strongly polarized Th2 host immune response and a severe impairment of mitogen-driven proliferation and type 1 cytokine production in mice and humans. The role of this polarization in the development of the broad spectra of clinical manifestations of lymphatic filariasis is still unknown. Recently, data gathered from humans as well as from immunocompromised mouse models suggest that filariasis elicits a complex host immune response involving both Th1 and Th2 components. However, responses of a similar nature have not been reported in immunologically intact permissive models of Brugia infection. Brucella abortus-killed S19 was inoculated into the Brugia-permissive gerbil host to induce gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production. Gerbils were then infected with B. pahangi, and the effect of the polarized Th1 responses on worm establishment and host cellular response was measured. Animals infected with both B. abortus and B. pahangi showed increased IFN-γ and interleukin-10 (IL-10) and decreased IL-4 and IL-5 mRNA levels compared with those in animals infected with B. pahangi alone. These data suggest that the prior sensitization with B. abortus may induce a down regulation of the Th2 response associated with Brugia infection. This reduced Th2 response was associated with a reduced eosinophilia and an increased neutrophilia in the peritoneal exudate cells. The changes in cytokine and cellular environment did not inhibit the establishment of B. pahangi intraperitoneally. The data presented here suggest a complex relationship between the host immune response and parasite establishment and survival that cannot be simply ascribed to the Th1/Th2 paradigm.

Human lymphatic filariasis, caused by the filarial nematodes Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi, affects a large proportion of people in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Infection in humans is accompanied by the development of a prominent Th2-type host response, reflected by an expansion of interleukin-4 (IL-4)- and IL-5-producing CD4+ cells, an increase in serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) and IgG4 levels, (20, 24), and a pronounced eosinophilia (20). This response is accompanied by a severe impairment of mitogen-driven proliferation and IL-2 and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production in mice and humans (36).

In regions of endemic filariasis, most infected individuals are microfilaremic but asymptomatic and are considered to be immunologically hyporesponsive to filariae. These impaired responses to filarial antigens are manifested by a reduction in T-cell proliferation (43, 46, 48) and impaired production of immunoglobulin to parasite antigens in vitro (44). In contrast, patients who develop pathological signs such as elephantiasis are characteristically amicrofilaremic and mount strong cellular and humoral immune responses to the parasite. These responses, in conjunction with extrinsic immune-independent factors, are reported to contribute to the pathological changes observed in such people (13).

The questions regarding filaria-induced host responses in humans can best be addressed by using a laboratory animal model. The Brugia-mouse model is the most attractive due to the availability of a wide range of inbred and knockout strains and the most contemporary immunologic reagents. Depleting Th1 responses in mice appears to result in increased worm recoveries, as reported for both IFN-γ knockout mice (2) and mice depleted of nitric oxide (49). Together, these observations suggest that Th1-mediated events, such as the activation of macrophages, are involved in protective resistance to Brugia. This is supported by the Th2 nature of immune responses reported from hosts carrying persistent infections. However, the lack of long-term parasite survival and the nonpermissive nature of most strains of mice suggest that infection in these animals may not truly mimic human infection, thereby limiting the usefulness of this model.

The Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) has proven to be an excellent permissive rodent model for the study of lymphatic filariasis using B. pahangi (21, 22, 42) or B. malayi (40). Upon infection, gerbils develop chronic infections with persistent microfilaremia and are susceptible to reinfection (33). Gerbils infected either subcutaneously or intraperitoneally (i.p.) show granuloma formation in the lymphatics or peritoneal cavity, respectively. Brugia-infected gerbils also show the characteristic decrease in antigen-induced proliferative responses (25, 29) and the Th2 type cellular response observed in humans (T. R. Klei, S. R. Chirgwin, U. R. Rao, and Z. Mai, unpublished data).

Recognition of the contrasts between Th1 and Th2 responses in many diseases has recently brought to light the therapeutic possibilities of manipulating the Th1-Th2 balance in an attempt to alter disease outcome (7). The Mongolian gerbil-Brugia model is a well-defined system with which to investigate this phenomenon. Specifically, altering the cell-mediated immune response in gerbils at the time of infection with B. pahangi may alter parasite establishment and early development and/or the progression of lesion development. Bacteria such as Brucella abortus elicit a dominant Th1-type host response to infection in both humans and mice, characterized by the production of IFN-γ in both humans and mice (51, 53, 54, 57). In addition, Brucella has previously been used in mice to alter the cytokine mileu and, consequently, the subsequent outcome of infection with gastrointestinal nematodes (55). The aims of the studies presented here were twofold: (i) to compare the effectiveness of various strains of B. abortus as immunomodulators in the gerbil, with the aim of inducing an environment rich in Th1-type cytokines, as indicated by an increase in IFN-γ levels, and (ii) to determine whether the prior establishment of a dominant Th1 response would alter the parasite-associated inflammatory response and/or the parasite-induced cytokine profile and consequently alter the i.p. establishment and early development of B. pahangi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gerbils and parasites.

Male Mongolian gerbils, approximately 8 weeks of age, were obtained from Charles River (Wilmington, Mass.) and maintained on standard rodent chow and water ad libitum. B. pahangi infective third-stage larvae (L3) were recovered from infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes by using Baermannization as previously described (25). Aliquots of 100 L3 larvae were counted into 0.5 ml of RPMI and injected i.p. Control gerbils were injected with 0.5 ml of media used to harvest the larvae from mosquitoes.

Experimental design and inoculation of gerbils with B. abortus strains.

Gerbils were inoculated with one of four B. abortus strains to determine their susceptibility to the bacteria and to characterize the cytokine profile induced upon infection. The gerbils were divided into five groups, each consisting of 25 animals. Stock cultures of bacteria were removed from −70°C and diluted to the desired concentrations (8), and actual numbers of live Brucella strains were determined by viable counts. Animals were given 5 × 104 live B. abortus S19 (S19) or B. abortus 2308 (2308), 4 × 108 B. abortus RB51 (RB51), or 1 of mg killed B. abortus S19 bacteria (kS19) (equivalent to ∼5 × 1011 organisms) bacteria in sterile saline. Control animals were injected with sterile saline only. Twenty-five gerbils (five from each treatment group) were euthanized at 7, 14, 28, 42, and 56 days postinfection (p.i.). Serum, spleen, and peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) were collected from each animal for examination of antibody responses, bacterial colonization, and/or cytokine mRNA analysis.

Quantifying bacteria in spleen.

Half of the spleen from each gerbil was examined for bacterial colonization. The tissue was homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), serially diluted, and then plated onto agar plates containing whole serum. Following incubation at 37°C (under 10% CO2) for 3 days, the bacterial colonies were counted and a log value of bacteria in spleen tissue was obtained by taking the mean of triplicate counts following log conversion (8, 41). Counts were doubled prior to log conversion to adjust numbers for the entire organ.

Serum collection and analysis for antibody production.

Gerbils were bled under anesthesia from the retro-orbital sinus prior to and during infection, as well as at necropsy. The sera were isolated and then mixed with an equal volume of Rose-Bengal cells (card test) (1). Following room temperature incubation for 4 mins, the samples were scored as either positive for the presence of agglutination (indicating the presence of anti-Brucella antibodies) or negative for agglutination (antibody negative).

Coinfection of gerbils with B. abortus and B. pahangi.

Following this initial study, two further experiments were conducted to investigate the effect of B. abortus-induced IFN-γ on the establishment of an i.p. B. pahangi infection. For these studies, gerbils were divided into four groups of either 8 (first experiment) or 12 (second experiment) animals. The groups were saline- and medium-inoculated control (0+0), kS19 inoculated (Ba+0), B. pahangi infected (0+Bp), and kS19 and B. pahangi infected (Ba+Bp).

In both experiments, animals were inoculated i.p. with either kS19 B. abortus (Ba+0) or sterile saline (0+0) on day −7. On day 0, three gerbils receiving either saline (0+0) or bacteria (Ba+0) were euthanized and their spleens, renal lymph nodes (RLN), and PEC were collected for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of cytokine mRNA. Half of the remaining animals were then i.p. infected with 100 B. pahangi L3 larvae (0+Bp, Ba+Bp) while the rest were given medium only (0+0, Ba+0). All animals were euthanized at 28 days p.i., a time when the worms have completed their developmental molts and are classified as immature adults. In this way, the experiment was focused on the effect of elevated levels of IFN-γ on early establishment and subsequent survival of B. pahangi. In addition, at this time the worms are larger and easier to visualize than are early L3 larvae, increasing the accuracy of the worm recovery data.

Spleen, RLN, and PEC samples were analyzed for cytokine mRNA, and worms were recovered and enumerated in both experiments. In the second experiment, complete blood cell counts (CBC) were conducted and the host inflammatory response to parasite antigens was investigated using a pulmonary granulomatous response (PGRN) model (26). Cytokine gene expression data presented here are the mean of the two coinfection experiments. Worm recoveries are presented from both experiments.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

RNA was extracted from the spleens and PEC of gerbils in all experiments. RLN were also processed for RNA in the coinfection experiments. PEC were collected by lavage with PBS. Spleen and RLN single-cell suspensions, prepared by passing half of the spleen or both lymph nodes through a 70-μm cell strainer (Falcon), were centrifuged at 2,600 × g for 10 min (4°C). The pellets were resuspended and homogenized in 0.5 ml of RNAStat 60 (Tel-test, Friendship, Tex.), snap frozen on dry ice, and then stored at −70°C. RNA was isolated using chloroform extraction as specified by the manufacturer (Tel-test), and its concentration and integrity were determined using a spectrophotometer. Reverse transcription was carried out on 1,200 ng of RNA as previously described (54). This cDNA was employed as a template in quantitative PCR using either the Q-PCR system 5000 (Q-PCR) or the ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system (Taqman) (both produced by Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Primers and probes.

The gene sequences encoding gerbil IL-4 (GenBank accession no. L37779), IL-5 (L37780), IL-10 (L37781), IFN-γ (L37782), and hypoxamthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) (L37778) have been reported elsewhere (37, 38, 39). Gerbil cytokine- and HPRT-specific oligonucleotide primers and probes were designed for both quantitative PCR systems and generated commercially (GeneLab, Baton Rouge, La.; Baron Biotech, Plymouth, Mass.; Applied Biosystems). All oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers and probes used for Q-PCR and Taqman for all molecules measureda

| Gene | Sequenceb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sense (5′-3′) | Antisense (5′-3′)c | Probe (5′-3′)d | |

| HPRT | CTC ATG GAC TGA TTA T5GG ACA G | AGC TGA GAG ATC ATC TCC ACC AAT | GGG GGC TAT AAA TTC TTT GCT G |

| CCTTTTTCCCCCGTTAGTTCA | CATCGCCAATCACGATGCT | CCGTCATGGCGACCCGCAG | |

| IFN-γ | ATC AGG GCA GAT CTA ATC GCT AAC T | TGA CTC TGG GTG ACA GAT GGC CCA | TGAAGCGAAATACGATGGGTT |

| TTCGTACAGGAGCCGGACTT | ACAAGATGCAGTGTGTAGCGTTC | CCCTGCCTCAGCCTAGCTCAGAGACC | |

| IL-4 | TTG TCT CAC ATC CCT GAC GGT AG | AGC ATG GAG TCA CCT CTC GTG | ATA GCA ACG AAG AAC ACC ACA |

| CAGGGTGCTCCGCAAATT | AGGACCCCGGAGTTGTTCTT | TTCCCACGAGAGGTGACTCCATGCT | |

| IL-5 | GAC CTT GAT ACA GCT GTC CAC TC | GTA ATC CAG GAA CTG CCG TGC T | ATA AAA ATC ACC AGC TGT GCA T |

| CTCACCGGGCTCTACTGACAA | CAATGCACAGCTGGTGATTTTT | CAACGAGACAGTGAGGCTTCCTGTTCCT | |

| IL-10 | CCA GCT CGG CAC TGC TAT ATT G | TTT CCA AGG AGG TGC TTC TGT TAG | GCG GCG CTG TCA TCG ATT TC |

| GGCAGCCTTGCAGAAGACA | TCCAGCCAGTAAGATTAGGCAATA | AGCTCCATCATGCCCAGCTCGG | |

All primers and probes are shown for both systems, although IL-5 was measured using only Taqman and IL-4 and IFN-γ were measured using only Q-PCR.

Q-PCR primers and probes are on the top line of each cell. Taqman primers and probes are on the bottom line of each cell.

Antisense primers for Q-PCR were labeled with biotin at the 5′ terminus.

Probes for Q-PCR were labeled with TBR at the 5′ terminus. Probes for Taqman were labeled with 6-FAM at the 5′ terminus and TAMRA at the 3′ terminus.

Primers designed from the antisense DNA strand for use with the Q-PCR system 5000 (i.e., IL-4, IFN-γ, and HPRT) were biotinylated at their 5′ terminus. Probes used in Q-PCR hybridization were designed from the sense strand and were labeled with tris-(2,2′-bipyridine) ruthenium(II) chelate (TBR) at their 5′ terminus. Primers used with the 7700 sequence detection system (IL-5, IL-10, and HPRT) were unlabeled, while probes designed for this system were labeled with the reporter dye FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein) and the quencher dye TAMRA (6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine).

PCRs.

Q-PCRs were optimized for gerbil cDNA samples based on previously published data from equine cytokines (54) and were conducted under optimal conditions for exponential phase amplification. Amplification was carried out using the following parameters; 94°C for 1 min, then 34 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 40 s, with a final extension of 72°C for 7 min. Taqman PCRs for HPRT, IL-5, and IL-10 were carried out using the PE Biosystems Universal PCR Master Mix as specified by the manufacturer. All quantitative PCR analyses were carried out in duplicate.

Quantitating cytokines with the Q-PCR System 5000.

Cytokine mRNA was quantified as described previously (54). Briefly, 5 μl of PCR product was hybridized to a TBR-labeled probe and captured with streptavidin-coated beads (Dynabeads; Applied Biosystems). The reaction was then quantified by a photomultiplier tube that reports the final value in luminosity units (LUM).

The mean LUM generated by the Q-PCR machine for each cytokine was normalized to HPRT using the following method. A standard numerical value (2,500) was divided by the mean HPRT LUM for each sample. This number was then multiplied by the average LUM for each cytokine measured in that sample to give a corrected cytokine LUM value. Comparison of the LUM units of the cytokines in treated groups compared with those obtained from control animals allowed the cytokine level to be expressed as a measure of fold change compared with controls.

For the two coinfection studies, HPRT, IL-4, and IFN-γ mRNA levels were measured using plasmid standard curves to interpolate a numerical value of cytokine expression (copy unit). The raw LUM values obtained for the plasmid curves and the samples were analyzed using linear regression (SigmaPlot) (described in reference 54). The luminosity values obtained for cytokine samples were then interpolated to give the copy units of a cytokine present in a sample. The mean was calculated from control (0+0), groups and each cytokine value from animals in treatment groups was divided by this mean to provide a measure of fold change in cytokine production compared to controls ± standard error.

Detecting IL-5 and IL-10 using the 7700 sequence detection system.

Taqman PCRs were conducted using commercially available PCR master mix and the suggested protocol (Applied Biosystems). Relative standard curves were constructed using cDNA produced from RNA isolated from spleen cells stimulated with concanavalin A (10 μg/ml) for 24 h (see reference 26 for the protocol). Undiluted cDNA was designated a value of 1,000. Serial dilutions (1:1) were made, with the first dilution designated 500, the second designated 250, etc., until 10 dilutions had been made.

Cycle threshold values were obtained for IL-5, IL-10 and HPRT for each gerbil PEC sample. Linear regressions were carried out as described in the ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system user bulletin no. 2 (Applied Biosystems). Values obtained for IL-5 and IL-10 were normalized to the HPRT value of that sample, and values are presented as fold change compared with the mean value of the control group ± standard error.

PGRN.

A PGRN was induced by embolizing cyanogen bromide-Sepharose 4B (CNBr-4B) beads (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, Mo.) in the lungs of gerbils 3 days prior to necropsy, as previously described (22). In brief, sized CNBr-4B beads were coated with either parasite-soluble extracts (SAWA) (see reference 22 for preparation of SAWA) or diethylamine (DEA) (Sigma). Gerbils received approximately 2.5 × 104 beads inoculated into the retro-orbital sinus. At necropsy the lungs were perfused with 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and step sectioned at 2.4 μm. At least 40 μm of tissue was cut before the next step section was taken to ensure that multiple measurements were not taken on the same bead. Areas of 20 granulomas surrounding 40- to 60-μm diameter beads were measured in each animal by using Photoshop image analysis software (Corel Corp. Ltd., Dublin, Ireland), and the are data presented as the arithmetic means of each treatment group ± standard error.

Cellular profile.

All gerbils in the second coinfection study were bled at necropsy for CBC analysis. Cells were also washed from the peritoneal cavity of all gerbils using PBS. The washes were centrifuged (2,600 × g for 10 min at 4°C) and resuspended in 5 ml PBS. Aliquots of 100 μl were applied to a glass slide using a Cytospin (Shandon Inc, Pittsburgh, Pa.). Cells were heat fixed and then stained with a modified Wright's Giemsa stain (Hema-Tek Stain Pak; Bayer Corp., Tarrytown, N.Y.). One hundred cells were counted and identified as eosinophils, mast cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, or macrophages.

Statistics.

Cytokine mRNA, PGRN data, and cell counts were analyzed using analysis of variance. Bacterial colonization data were analyzed using analysis of variance and Tukey's test. Worm recovery data were analyzed using a t test and Tukey's test. Significance was set at P < 0.05 for all tests. All statistical analyses were conducted using SYSTAT 8.0 (SSPS Inc.).

RESULTS

Gerbils clear B. abortus strains following antibody production.

All gerbils inoculated with B. abortus S2308, S19, or kS19 produced antibodies, although the kinetics of the antibody response varied according to the bacterial strain (data not shown). Animals infected with virulent S2308 produced the most rapid antibody response, with all animals testing positive by 14 days p.i. All gerbils receiving kS19 were also antibody positive at 14 days p.i., while 100% of animals receiving the live S19 cells were not positive until 42 days p.i. No gerbils inoculated with RB51 were positive, since RB51 is a rough B. abortus strain and does not carry the oligopolysaccharide molecule found on the outer membrane of the smooth B. abortus strains (28). The agglutinating antibodies measured by the card test are produced against this oligopolysaccharide molecule.

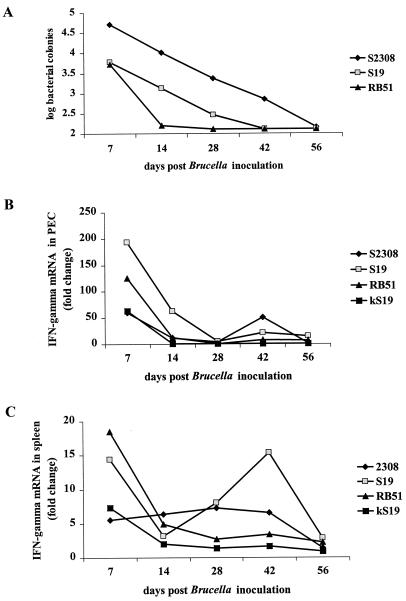

The rate of bacterial clearance by the gerbils corresponded with strain virulence (Fig. 1A). S2308 was isolated from all gerbils at 28 days p.i. and was still cultured from one animal at 56 days p.i. Indeed, gerbils receiving S2308 showed significantly higher bacterial colonization than did gerbils receiving other strains until this time. Gerbils receiving S19 cleared the bacteria more quickly than did those infected with S2308 but less quickly than those infected with RB51. The difference in bacterial growth between gerbils infected with S19 and RB51 was statistically significant at 14 days p.i.

FIG. 1.

Quantitation of bacterial colonization in spleens (A) and IFN-γ mRNA in PECs (B) and spleen cells (C) of gerbils following infection with B. abortus S2308, S19, RB51, or kS19. Gerbils were necropsied on days 7, 14, 28, 42 and 60 after inoculation with B. abortus. Clearance of B. abortus by gerbils was inversely related to strain virulence. IFN-γ mRNA was induced in both PECs and spleen following bacterial infection, peaking at 7 days p.i. The profile of IFN-γ induction varied with the bacterial strain.

B. abortus infection results in increased IFN-γ production in the spleen and PEC of the Mongolian gerbil.

Cytokine mRNA levels were quantitated in PEC and spleen samples collected from all necropsied gerbils. PEC taken from all Brucella-infected gerbils showed elevated levels of IFN-γ at 7 days p.i., with S19 producing the highest increase (193-fold greater than controls) (Fig. 1B). However, the levels of IFN-γ mRNA in PEC decreased markedly after 7 days p.i. in all animals and were generally absent after 28 days p.i. The PEC collected from the five gerbils in each treatment group were pooled at necropsy. Consequently, no statistical analysis was performed due to the lack of replicates.

Spleen samples from B. abortus treated gerbils also showed increased IFN-γ, compared with those taken from control animals (Fig. 1C) at 7 days p.i. As in the PEC, RB51 and S19 induced the highest increase in IFN-γ mRNA levels, although RB51 (18-fold) was more effective than S19 (14-fold) in spleen cells. In all animals infected with kS19, S19, or RB51, levels of IFN-γ mRNA in the spleen fell rapidly after 7 days. However, levels of IFN-γ remained elevated until 42 days p.i. in spleens from gerbils infected with S2308. These levels were significantly higher than those induced in the spleens of gerbils receiving either RB51 or S19 at this time point. Inoculation of gerbils with the B. abortus strains did not result in increased levels of IL-4 mRNA compared with controls in either spleen or PEC samples (data not shown).

Based on these data, kS19 was selected for further experiments. This strain induced significant levels of IFN-γ on day 7 without concomitant effects of long-term Brucella infection or the hazards associated with using live organisms.

Ba+Bp gerbils show increased IFN-γ and a decreased Th2-type cytokine response.

Gerbils inoculated i.p. with kS19 (Ba+0) showed a 240-fold induction of IFN-γ in the PEC on day 0, compared with controls (0+0) (data not shown). Lower levels of IFN-γ were observed in the spleen (sixfold) and RLN (fivefold), however, confirming the strong compartmentalization of the gerbil cellular response following inoculation with various Brucella strains. As expected, little IL-4 was observed in either Ba+0 or 0+0 gerbils on day 0.

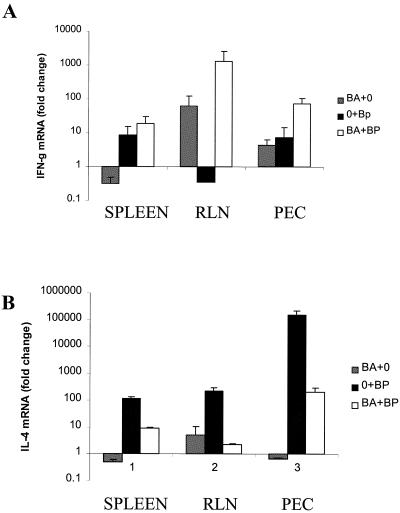

At 28 days p.i., Ba+Bp gerbils showed the highest levels of IFN-γ in all tissues (Fig. 2A). Indeed, the IFN-γ mRNA levels in PEC of Ba+Bp gerbils were significantly higher than were the levels in PEC from Ba+0 and 0+Bp gerbils at 28 days p.i. The highest increase in IL-4 mRNA levels, compared with controls, was observed in gerbils infected with B. pahangi alone (0+Bp) (Fig. 2B), while Ba+0 gerbils showed the lowest levels of IL-4 mRNA induction. Ba+Bp gerbils showed intermediate levels of IL-4 in spleen and PEC, suggesting a possible cross-regulatory effect by the pre-existing Th1-type response in these tissues. Little difference in RLN IL-4 mRNA levels was detected between 0+Bp- and Ba+Bp-treated gerbils.

FIG. 2.

Quantitation of IFN-γ (A) and IL-4 (B) in gerbil spleens, RLN, and PECs. Gerbils were inoculated with B. abortus (Ba+0), infected with B. pahangi (0+Bp), or given both B. abortus and B. pahangi (Ba+Bp). On day 28 after B. pahangi infection, the gerbils were necropsied and spleen, RLN, and PEC RNA was isolated. IFN-γ and IL-4 mRNA levels were measured using RT-PCR and are expressed as fold change compared with control (0+0) gerbils.

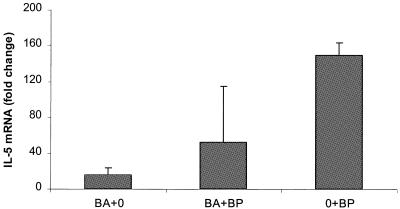

IL-5 mRNA levels in PEC showed a similar trend to IL-4 mRNA levels, with the highest levels observed in 0+Bp-infected gerbils, the lowest levels observed in Ba+0-treated gerbils, and intermediate levels observed in Ba+Bp-infected gerbils (Fig. 3). IL-10 mRNA exhibited a different pattern from that of IL-5, with low levels reported from Ba+0 and 0+Bp gerbils (less than a twofold increase compared with 0+0 gerbils). Ba+Bp gerbils showed slightly elevated levels of IL-10 (7.8-fold increase compared with control gerbils), which were not significantly different.

FIG. 3.

Quantitation of IL-5 mRNA in gerbil PECs Gerbils were given either B. abortus (Ba+0), B. pahangi (0+Bp) or both B. abortus and B. pahangi (Ba+Bp). PECs were collected and analyzed by RT-PCR for cytokine mRNA. Values are expressed as fold change compared with control animals (0+0).

Prior B. abortus sensitization does not significantly alter the inflammatory response to parasite antigens in B. pahangi-infected gerbils.

PGRN formation was used as an indicator of the immune responsiveness of the treated gerbils. The largest granulomas were observed in the lungs of 0+Bp gerbils inoculated with SAWA-coated Sepharose beads (data not shown), as expected from prior studies (22). The mean area of PGRN to BpAg-coated beads in Ba+Bp-treated gerbils (16,637.11 μm) was smaller than that observed in 0+Bp gerbils (19,554.17 μm) but larger than that seen in Ba+0 gerbils (833.26 μm). These differences were not statistically significant.

Sensitization with kS19 does not inhibit B. pahangi establishment.

There were no statistically significant differences in the number of worms recovered from treatment groups in either coinfection study (Table 2). However, we did observe that Ba + Bp gerbils harbored approximately 20% more worms than 0 + Bp gerbils in the second study. These data suggest that the presence of B. abortus-induced IFN-γ in the peritoneal cavity prior to and at the time of i.p. infection with B. pahangi and during the early development of the L3 larvae does not inhibit the establishment of this parasite in gerbils.

TABLE 2.

Mean worm recoveries at necropsy (28 days p.i.) for both coinfection experiments

| Treatment group | No. of wormsa

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PECb | Otherc | Total | |

| 0+BP | 23.1 ± 5.8 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 24.2 ± 5.7 |

| 34.7 ± 3.4 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 37.0 ± 3.3 | |

| BA+BP | 25.1 ± 5.3 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 26.4 ± 5.3 |

| 44.4 ± 5.5 | 2.1 ± 0.58 | 46.5 ± 5.7 | |

Values are means ± standard error. The top value in each row is from the first coinfection experiment. The bottom value in each row is from the second coinfection experiment.

Worms found in peritoneal washes.

Worms recovered by dissecting gerbil tissues.

Prior sensitization with B. abortus causes cellular changes in B. pahangi-infected gerbils.

Total circulating leukocytes were counted and expressed as the number of cells per milliliter. Bp+0 gerbils showed similar numbers of total leukocytes (19.4 × 106 cells/ml) to those in 0+0 gerbils (22.3 × 106 cells/ml). However, Ba+0 and Ba+Bp gerbils had significantly fewer total leukocytes than did 0+0 gerbils (13.5 × 106 and 14.3 × 106/ml, respectively).

Eosinophils were enumerated and expressed as a percentage of total circulating cells or PEC in each gerbil (Table 3). 0+Bp gerbils showed the greatest percentage of circulating eosinophils. Ba+Bp gerbils showed lower levels of eosinophils than those observed in 0+Bp gerbils but higher levels than those reported for Ba+0 gerbils. These data suggest the B. abortus sensitization and the presence of a Th1-type cellular environment may have changed the host cellular response to B. pahangi infection. Analysis of both untransformed and log-transformed data did not show statistically significant differences between the treatment groups.

TABLE 3.

Cellular composition of PECs and circulating eosinophil levels in gerbils at necropsya

| Treatment | % of PECs that wereb:

|

Circulating eos (% of total cells) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lympho | neu | mc | macs | eos | ||

| Ba+0 | 52.9 | 0 | 2.5 | 47.0 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| 0+BP | 52.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 34.5 | 11.6 | 5.1 |

| Ba+Bp | 62.3 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 29.0 | 8.0 | 1.4 |

| 0+0 | 53.1 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 45.8 | 0.4 | 2.8 |

All cells are expressed as percentage of cells counted.

lympho, lymphocytes; neu, neotrohils; mc, mast cells; macs, macrophages; eos, eosinophils.

The eosinophil profile in the peritoneal cavity mimicked that observed in CBCs (Table 3), with the highest eosinophilia recorded in 0+Bp gerbils. Ba+Bp animals showed fewer eosinophils than did 0+Bp gerbils, as was observed in peripheral cells. Eosinophils made up less than 1% of the total cells identified in 0+0 and Ba+0 gerbils. The levels of peritoneal eosinophils in Ba+Bp and 0+Bp gerbils were significantly different from those in 0+0 and Ba+0 gerbils (P = 0.01). Ba+Bp gerbils showed the highest levels of neutrophils and the lowest levels of macrophages (P = 0.03 and P = 0.04, respectively), suggesting a complex cellular environment. Total lymphocytes and mast cells were also identified and counted, although no significant differences existed between groups when examining these cells.

DISCUSSION

All three live strains of B. abortus colonized gerbils transiently, with bacteria being cleared between 28 (S19 and RB51) and 42 (S2308) days p.i. The kinetics of bacterial infection varied according to strain virulence, with S2308 persisting in gerbil spleens longer than did either S19 or RB51. However, the gerbils cleared S2308 by 42 days p.i., suggesting they are less susceptible to this strain than mice, which can harbor S2308 for between 12 weeks (C57BL/10) and 6 months (BALB/c) (41). This relationship between virulence and infection maintenance, which has also been observed in mice (41) and cattle (11), is probably due to the release by the more virulent strains of soluble factors (other than lipopolysaccharide) that inhibit phagolysosomal fusion (14), prevent degranulation (4) and oxidative burst (27), and suppress tumor necrosis factor alpha production by monocytes (5). The lengthened exposure to S2308 was also reflected by the prolonged immunoglobulin production observed in gerbils infected with this strain. This is the first report of the experimental infection of Mongolian gerbils with B. abortus and as such provides novel information on the use of this animal for further Brucella studies.

IFN-γ mRNA levels were increased in both PEC and spleens of gerbils following B. abortus inoculation. The largest increases in IFN-γ levels were observed following inoculation with either S19 (PEC) or RB51 (spleen) at 7 days p.i. The highest levels of IFN-γ mRNA were observed in gerbil PEC, the site of Brucella inoculation, following administration of S19. All PEC responses were greatly decreased by 14 days p.i. as the bacteria were cleared by the gerbils or began to colonize systemic organs, such as the spleen.

Brucella-induced Th1 responses have previously been shown to confer both resistance and increased susceptibility to various pathogens. For example, B. abortus-induced IFN-γ inhibits the development of protective immunity in mice to the nematode Nippostrongylus brasilienesis, probably by interfering with the production and effects of Th2 cytokines associated with this protection (55). In the present experiments, kS19 was used to induce IFN-γ in the peritoneal cavity of gerbils prior to infection with B. pahangi. The ability of kS19 to induce transient IFN-γ production by the gerbil in the absence of an ongoing infection made it a suitable candidate for these immunomodulation studies. Another advantage of using kS19 is that this strain can be manipulated under normal laboratory conditions, as opposed to the strict regimes required when working with live B. abortus strains.

Primary infection of both humans and mice (permissive or nonpermissive) with Brugia L3 larvae usually results in the induction of a Th2 host response (3, 34, 45, 56). Gerbils infected only with B. pahangi similarly developed Th2 responses, showing elevated levels of IL-4 and IL-5, compared with other groups. However, Ba+Bp gerbils had decreased levels of these Th2-type cytokines compared with 0+Bp gerbils. These gerbils also showed the highest levels of IL-10 and IFN-γ in all tissues, suggesting the presence of a mixed cytokine milieu following dual administration of kS19 and B. pahangi. The presence of both Th1- and Th2-type cytokines following administration of a bacterium and a helminth parasite is not unexpected. Indeed, similar results have been observed using antigen preparations. Pearlman et al. (47) immunized mice with Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen preparation either alone, or following immunization with B. malayi antigen. The mice immunized with helminth antigen followed by bacterial antigen showed IL-4, IL-5 and IFN-γ, production while the mice immunized only with M. tuberculosis antigen developed a strongly polarized Th1 response. These data suggest that there is a modulation effect of the initial immune effectors (to B. malayi antigen) on the host response raised against subsequent agents introduced into the host (in this case, M. tuberculosis antigen).

A similar phenomenon was observed in the present experiments, with Ba+Bp gerbils displaying mixed Th1 and Th2 cytokine responses. We now know that B. pahangi itself induces IFN-γ in the PECs of i.p. infected gerbils. Effectively, then, Ba+Bp gerbils received an initial Th1 stimulus followed by a mixed Th1-Th2 stimulus. It is possible that the preexisting Th1 cells in kS19-inoculated gerbils promoted further expansion of Th1 cell populations in response to B. pahangi infection. The cytokine environment at the time of antigen priming has been proposed to have a profound effect on the Th subset elicited following antigen administration (9), and Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes are thought to proliferate optimally in response to different populations of antigen-presenting cells. Alternatively, rather than promote further Th1 cell expansion, the Th1 component in the mixed immune response to B. pahangi may have been sufficient to delay the decline in the IFN-γ mRNA level observed in Ba+0 gerbils. In addition, the Th1 response may have actively contributed to the suppression of IL-4 and IL-5. Whether this down regulation is due specifically to the increased levels of IFN-γ remains undetermined.

Most commonly, patients with generalized onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis exhibit a decrease in cellular responsiveness (43). Evidence now suggests that this suppression of T-cell activation and inflammation in human onchocerciasis may be IL-10 and transforming growth factor dependent (10, 31, 32). T-cell clones generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with generalized onchocerciasis have shown a cytokine profile characteristic of a new type of suppressor cells previously found in tolerization against autoimmunity and alloreactivity (10, 17). This is the first report of the occurrence of such cells, termed Th3 or Tr1, in an infectious disease, and it has been suggested that they may be involved in parasitic infections that are not clearly polarized, such as lymphatic filariasis and schistosomiasis (16, 52). The production of both Th2 (IL-4 and IL-5) and Th1 (IFN-γ) responses by gerbils infected i.p. with B. pahangi L3 suggests that this is certainly not a strongly polarized host response. Tr1 cells are thought to suppress naive and memory Th1 and Th2 responses via the production of IL-10 and transforming growth factor β. In addition, whereas IL-10 was once clearly classified as a Th2-type cytokine that could down regulate Th1 responses, there is now increasing evidence that IL-10 may also act as an inhibitor of Th2 responses both in vivo and in vitro (58, 59). However, Ba+Bp gerbils did not show significantly higher levels of IL-10 than did other treatment groups, suggesting that if Th3/Tr1 cells are involved in the Th2 suppression observed in these experiments, they may act through mechanisms in addition to those involving IL-10.

The decreased PEC and circulating eosinophil levels in Ba+Bp gerbils corresponded to the observed reduction in Th2 cytokine responses. Numerous studies have shown that eosinophilia in nematode infections (6, 18, 19) and more specifically in filarial infections (12, 13) is dependent on the cytokine IL-5, and our data support a relationship between IL-5 and eosinophil levels in this model. However, this relationship appears to be complex. For example, IL-5 has been implicated in the killing of Onchocerca microfilariae (12) but appears to have little or no influence on the establishment of the rodent filariid Litomosoides sigmodontis L3 in BALB/c mice (27). The exact nature of the interactions between IL-5 and eosinophils and B. pahangi L3 early development in the gerbil model is still not known.

The neutrophil composition of PECs also varied between groups, with Ba+Bp gerbils showing significantly more neutrophils than did 0+0 gerbils (P = 0.011). Like eosinophils, neutrophils appear to play different roles in filarial infections. In onchocerciasis, they comprise a large proportion of the onchocercomata that forms around adult worms (46). Often these neutrophils are concentrated around the vulva of the worm, where microfilariae are released (50, 51). The data collected here show increased PEC neutrophil levels in response in 0+Bp gerbils, compared with 0+0 gerbils; this may be in response to the presence of microfilariae in the peritoneal cavity.

Gerbils sensitized to the Th1-type inducing organism B. abortus prior to infection with B. pahangi showed a slightly decreased PGRN response to SAWA-coated beads than did 0+Bp gerbils. The chronicity of filarial infections has been suggested to favor the expansion of T-cell subsets producing IL-4 and IL-5 (23, 24) and a suppression of Th1-type responses (24). However, other literature suggests that the inflammatory responses and clinical signs usually associated with both lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis can be linked to the presence of both Th1- and Th2-type cytokines (34, 48, 52). The data presented here indicate that altering the cytokine mileu by introducing B. abortus prior to B. pahangi infection does not significantly alter the PGRN response in gerbils.

The presence of elevated levels of IFN-γ in the peritoneal cavity at the time of B. pahangi infection does not appear to inhibit parasite establishment or development. Indeed, data from one experiment suggest that IFN-γ promotes L3 development, with approximately 20% more worms recovered from Ba+Bp than from 0+Bp animals. While this enhancement in parasite establishment was not recorded in the second experiment, it appears that IFN-γ in the vicinity of L3 inoculation is not detrimental to B. pahangi development in this model. This differs from reports suggesting that depleting Th1 effector molecules such as IFN-γ and NO results in enhanced Brugia recoveries in mice (2, 49). However, other studies suggest that Th1 effectors are not required for resistance to infection (15) and that the presence of IFN-γ may even enhance Brugia development in mice (30). These data underline the complex nature of the host-parasite interactions that occur during infection with Brugia.

While filarial infections are usually associated with a strong Th2 immune response, the biological implications of this polarized response remain to be fully elucidated. In an attempt to further clarify the role of Th1 and Th2 immune responses in B. pahangi infection in gerbils, B. abortus was used to induce significant IFN-γ mRNA expression at the time of infection with the filarial parasite. While inoculation with kS19 did not effect a complete switch to Th1 responses following B. pahangi infection, Th2 cytokine responses were depressed, as was the inflammatory response normally associated with Brugia infection. Additionally, Ba+Bp gerbils tended to show altered cell profiles, both i.p. and in circulation. However, these changes were insufficient to provide protection against B. pahangi infection, suggesting either that a strong Th2-type cytokine response is not essential for successful establishment of the nematode or that a more strongly Th1 polarized response is necessary to inhibit larval development.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of Keiko Antoku in the initial sensitization experiment.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI-19199-18.

Editor: J. M. Mansfield

REFERENCES

- 1.Alton, G. G., L. M. Jones, R. D. Angus, and J. M. Verger. 1988. Serological methods, p. 81-86. In G. G. Alton (ed.), Techniques for the brucellosis laboratory. Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Nouzilly, France.

- 2.Babu, S., L. M. Ganley, T. R. Klei, L. D. Shultz, and T. V. Rajan. 2000. Role of interferon and interleukin-4 in host defense against the human filarial parasite Brugia malayi. Infect. Immun. 68:3034-3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bancroft, A. J., R. K. Grencis, K. J. Else, and E. Devaney. 1993. Cytokine production in BALB/c mice immunized with radiation attenuated third stage larvae of the filarial nematode, Brugia pahangi. J. Immunol. 150:1395-1402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertram, D. T., P. C. Canning, and J. A. Roth. 1986. Preferential inhibition of primary granule release from bovine neutrophils by a Brucella abortus extract. Infect. Immun. 52:285-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caron, E., T. Peyard, S. Kohler, S. Cabane, J. P. Liautard, and J. Dornand. 1994. Live Brucella spp. fail to induce tumor necrosis factor alpha excretion upon infection of U937-derived phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 62:5267-5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coffman, R. L., B. W. Seymour, J. Jackson, and D. Rennick. 1989. Antibody to interleukin-5 inhibits helminth-induced eosinophilia in mice. Science 245:308-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffman, R. R., S. Mocci, and A. O'Garra. 1999. The stability and reversibility of Th1 and Th2 populations, p. 1-12. In R. L. Coffman and S. Romagnani (ed.), Redirection of Th1 and Th2 responses. Springer Verlag, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.De Bagues, M. P. J., P. H. Elzer, S. M. Jones, J. M. Blasco, F. M. Enright, G. G. Schurig, and A. J. Winter. 1994. Vaccination with Brucella abortus rough mutant RB51 protects BALB/c mice against virulent strains of Brucella abortus, Brucella melitensis, and Brucella ovis. Infect. Immun. 62:4990-4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devaney, E., and J. Osborne. 2000. The third-stage larvae (L3) of Brugia: its role in immune modulation and protective immunity. Microbes Infect. 2:1363-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doetze, A., J. Satoguina, G. Burchard, T. Rau, C. Loliger, B. Fleischer, and A. Hoerauf. 2000. Antigen specific cellular hyporesponsiveness in a chronic human helminth infection is mediated by T(h)3/T(r)1-type cytokines IL-10 and transforming growth factor beta but not by a T(h) 1 to T(h)2 shift. Int. Immunol. 12:623-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edmonds, M. D., A. Cloeckaert, N. J. Booth, W. T. Fulton, S. D., Hagius, J. V. Walker and P. H. Elzer. 2001. Attenuation of a Brucella abortus mutant lacking a major 25 kDa outer membrane protein in cattle. Am. J. Vet. Res. 62:1461-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folkard, S. G. 1996. Eosinophils are the major effector cells of immunity to microfilariae in a mouse model of onchocerciasis. Parasitology 112:323-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedman, D. O. 1998. Immune dynamics in the pathogenesis of human lymphatic filariasis. Parasitol. Today 14:229-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frenchick, P. J., R. J. Markham, and A. H. Cochrane. 1985. Inhibition of phagosome and lysosome fusion in macrophages by soluble extracts of virulent Brucella abortus. Am. J. Vet. Res. 45:332-335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganley, L., S. Babu, and T. V. Rajan. 2001. Course of Brugia malayi infection in C57BL/6J NOS2+/+ and −/− mice. Exp. Parasitol. 1:35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grogan, J. L., P. G. Kremsner, A. M. Deelder, and M. Yazdanbakhsh. 1998. Antigen-specific proliferation and interferon-gamma and interleukin-5 production are down regulated during Schistosoma haematobium infection. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1433-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groux, H., A. O'Garra, M. Bigler, M. Rouleau, S. Antonenko, J. E. de Vries, and M. G. Roncarolo. 1997. A CD4+ T-cell subset inhibits antigen-specific T-cell responses and prevents colitis. Nature 389:737-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall, L. R., R. K. Mehlotra, A. W. Higgins, M. A. Haxhiu, and E. Pearlman. 1998. An essential role for interleukin-5 and eosinophils in helminth-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Infect. Immun. 66:4425-4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogarth, P. J., M. J. Taylor, and A. E. Bianco. 1998. IL-5 dependant immunity is independent of IL-4 in a mouse model of onchocerciasis. J. Immunol. 160:5436-5440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussain, R., and E. A. Ottesen. 1986. IgE responses in human filariasis. IV. Parallel antigen recognition by IgE and IgG4 subclass antibodies. J. Immunol. 136:1859-1863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeffers, G. W., T. R. Klei, and F. M. Enright. 1984. Activation of jird (Meriones unguiculatus) macrophages by the filarial parasite Brugia pahangi. Infect. Immun. 43:43-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeffers, G. W., T. R. Klei, F. M. Enright, and W. G. Henk. 1987. The granulomatous inflammatory response in jirds, Meriones Unguiculatus, to Brugia pahangi: an ultrastuctural and histochemical comparison of the reaction in the lymphatics and peritoneal cavity. J. Parasitol. 73:1220-1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King, C., S. Mahanty, V. Kumaraswami, J. Abrams, J. Regunathan, K. Jayaraman, E. Ottesen, and T. Nutman. 1993. Cytokine control of parasite-specific anergy in human lymphatic filariasis. Preferential induction of a regulatory T helper type 2 lymphocyte subset. J. Clin. Investig. 92:1667-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King, C. L., and T. B. Nutman. 1991. Regulation of the immune response in lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Immunol. Today 12:A54-A58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klei, T. R., C. S. McVay, V. A. Dennis, S. U. Coleman, F. M. Enright, and H. W. Casey. 1990. Brugia pahangi: effects of duration of infection and parasite burden on lymphatic lesion severity, granulomatous hypersensitivity, and immune responses in jirds (Meriones unguiculatus). Exp. Parasitol. 71:393-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klei, T. R., C. S. McVay, S. U. Coleman, F. M. Enright, and U. R. Rao. 1991. Adoptive transfer of granulomatous inflammation to Brugia antigens in jirds. J. Parasitol. 83:626-629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korenaga, M., and I. Tada. 1994. The role of IL-5 in the immune responses to nematodes in rodents. Parasitol. Today 10:234-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kreutzer, D. L., C. S. Buller, and D. C. Robertson. 1979. Chemical characterization and biological properties of lipopolysaccharides isolated from smooth and rough strains of Brucella abortus. Infect. Immun. 23:811-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lammie, P. J., and S. P. Katz. 1983. Immunoregulation in experimental filariasis. I. In vitro suppression of mitogen-induced blastogenesis by adherent cells from jirds chronically infected with Brugia pahangi. J. Immunol. 130:1381-1385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawrence, R. A., J. E. Allen, and C. A. Gray. 2000. Requirements for in vivo IFN-gamma induction by live microfilariae of the parasitic nematode, Brugia malayi. Parasitology 120:631-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levings, M. K., and M. G. Roncarolo. 2000. T-regulatory 1 cells: a novel subset of CD4 T cells with immunoregulatory properties. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 106:S109-S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levings, M. K., R. Sangregorio, F. Galbiati, S. Squadrone, R. de Waal Malefyt, and M. G. Roncarolo. 2001. IFN-alpha and IL-10 induce the proliferation of human type 1 T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 66:5530-5539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin, D. S., S. U. Coleman, U. R. Rao, and T. R. Klei. 1995. Absence of protective resistance to homologous challenge infections in jirds with chronic, amicrofilaraemic infections of Brugia pahangi. J. Parasitol. 81:643-646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacDonald, A. S., R. M. Maizels, R. A. Lawrence, I. Dranfield, and J. E. Allen. 1998. Requirement for in vivo production of IL-4, but not IL-10, in the induction of proliferative suppression by filarial parasites. J. Immunol. 160:4124-4132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahanty, S., J. Abrams, C. King, A. Limaye, and T. Nutman. 1992. Parallel regulation of IL-4 and IL-5 in human helminth infections. J. Immunol. 148:3567-3571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahanty, S., C. L. King, V. Kumaraswami, J. Regunathan, A. Maya, K. Jayaraman, J. S. Abrams, E. A. Ottesen, and T. B. Nutman. 1993. IL-4 and IL-5-secreting lymphocyte populations are preferentially stimulated by parasite-derived antigens in human tissue invasive nematode infections. J. Immunol. 1:3704-3711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mai, Z, G. K. Kousoulas, D. W. Horohoy, and T. R. Klei. 1994. Cross-species cloning of gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) interleukin-2 cDNA and it's expression in COS-7 cells. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 40:63-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mai, Z. 1996. Experimental lymphatic filariasis in gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus): molecular cloning and expression of gerbil cytokines and measurement of cytokine gene expression during a primary infection of Brugia pahangi. Ph.D. thesis. Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

- 39.Mai, Z., D. W. Horohov, and T. R. Klei. 1998. Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase cDNA in gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus). Lab. Anim. Sci. 48:179-183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McVay, C. S., T. R. Klei, S. U. Coleman, and S. C. Bosshardt. 1990. A comparison of host responses of the Mongolian jird to infections of Brugia malayi and B. pahangi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 43:266-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montaraz, J. A., and A. J. Winter. 1986. Comparison of living and nonliving vaccines for Brucellla abortus in BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 53:245-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nasarre, C., S. U. Coleman, U. R. Rao, and T. R. Klei. 1997. Brugia pahangi: differential induction and regulation of jird inflammatory responses by life-cycles stages. Exp. Parasitol. 87:20-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nutman, T. B., V. Kumaraswami and E. A. Ottesen. 1987. Parasite-specific anergy in human filarisis: insights after analysis of parasite antigen-driven lymphokine production. J. Clin. Investig. 79:1516-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nutman, T. B., V. Kumaraswami, L. Pao, P. R. Narayanan, and E. A. Ottesen. 1987. An analysis of in vitro B cell immune responsiveness in human lymphatic filariasis. J. Immunol. 138:3954-3959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osborne, J., S. J. Hunter, and E. Devaney. 1996. Anti-interleukin-4 modulation of the Th2 polarized response to the parasitic nematode Brugia pahangi. Infect. Immun. 64:3461-3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ottesen, E. A., P. F. Weller, M. Lunde, and R. Hussain. 1982. Endemic filariasis on a pacific island. II. Immunological aspects: immunoglobulin, complement, and specific antifilarial IgG, IgM and IgE antibodies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 78:953-961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pearlman, E., J. W. Kazura, F. E. Hazlett, and W. H. Boom. 1993. Modulation of murine cytokine responses to mycobacterial antigens by helminth-induced T helper 2 cell responses. J. Immunol. 151:4857-4864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piessens, W. F., P. B. McGreevy, P. W. Piessens, M. McGreevy, I. Koiman, J. S. Saroso, and D. T. Dennis. 1980. Immune responses in human infections with Brugia malayi: specific cellular unresponsiveness to filarial antigens. J. Clin. Investig. 65:172-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rajan, T. V., P. Porte, J. A. Yates, L. Keefer, and L. D. Shultz. 1996. Role of nitric oxide in host defense against an extracellular, metazoan parasite, Brugia malayi. Infect. Immun. 64:3351-3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubio de Kromer, M. T., M. Kromer, K. Luersen, and N. W. Brattig. 1998. Detection of a chemotactic factor for neutrophils in extracts of female Onchocerca volvulus. Acta Trop. 15:46-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schulz-Key, H. 1990. Observations on the reproductive biology of Onchocerca volvulus. Acta Leiden. 59:27-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soboslay, P. T. C. G. Luder, S. Reisch, S. M. Geiger, M. Banla, E. Batchassi, A. Stadler, and H. Schulz-Key. 1999. Regulatory effects of Th1-type (IFN-gamma, IL-2) and Th2-type (IL-10, IL-13) on parasite-specific cellular responsiveness in Onchocerca volvulus-infected humans and exposed endemic controls. Immunology 97:219-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Svetic, A., Y. C. Jian, F. D. Finkleman, and W. C. Gause. 1993. Brucella abortus induces a novel cytokine gene expression pattern characterized by elevated IL-10 and interferon gamma in CD4+ T cells. Int. Immunol. 5:877-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swiderski, C. E., T. R. Klei, and D. W. Horohov. 1999. Quantitative measurement of equine cytokine mRNA expression by polymerase chain reaction using target specific standard curves. J. Immunol. Methods 222:155-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Urban, J. F., K. B. Madden, A. W. Cheever, P. P. Trotta, I. M. Katona, and F. D. Finkelman. 1993. IFN inhibits inflammatory responses and protective immunity in mice infected with the nematode parasite, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. J. Immunol. 15:7086-7094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vickery, A. C., and A. L. Vincent. 1984. Immunity to Brugia pahangi in athymic mice and normal mice: eosinophilia, antibody and hypersensitivity responses. Parasite Immunol. 6:545-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaitseva, M. B., H. Golding, M. Betts, A. Yamauchi, E. T. Bloom, L. E. Butler, L. Stevan, and B. Golding. 1995. Human peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells express Th-1 like cytokine mRNA and proteins following in vitro stimulation with heat-inactivated Brucella abortus. Infect. Immun. 63:2720-2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zuany-Amorim, C., S. Haile, D. Leduc, C. Dumarey, M. Huerre, B. B. Vargaftig, and M. Pretolani. 1995. Interleukin-10 inhibits antigen-induced cellular recruitment into the airways of sensitized mice. J. Clin. Investig. 95:2644-2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zuany-Amorim, C., C. Creminon, M. C. Nevers, M. A. Nahori, B. B. Vargaftig, and M. Pretolani. 1996. Modulation by IL-10 of antigen-induced IL-5 generation, and CD4+ T lymphocyte and eosinophil infiltration into the mouse peritoneal cavity. J. Immunol. 157:377-384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]