Abstract

Synthetic RS20 peptide and a set of its point-mutated peptide analogs have been used to analyze the interactions between calmodulin (CaM) and the CaM-binding sequence of smooth-muscle myosin light chain kinase both in the presence and the absence of Ca2+. Particular peptides, which were expected to have different binding strengths, were chosen to address the effects of electrostatic and bulky mutations on the binding affinity of the RS20 sequence. Relative affinity constants for protein/ligand interactions have been determined using electrospray ionization and Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. The results evidence the importance of electrostatic forces in interactions between CaM and targets, particularly in the presence of Ca2+, and the role of hydrophobic forces in contributing additional stability to the complexes both in the presence and the absence of Ca2+.

INTRODUCTION

Calmodulin (CaM) forms tight complexes with a large number of target proteins, interacting with its targets in aqueous solution in both a Ca2+-dependent and a Ca2+-independent manner (Crivici and Ikura, 1995; Tsvetkov et al., 1999; Hill et al., 2000). The binding affinity for Ca2+ typically increases in the presence of target (Mirzoeva et al., 1999; Hill et al., 2000). Mg2+ has been assumed either to prevent the formation of CaM–target–Ca4 complex (Ohki et al., 1993) or to decrease both Ca2+ and target binding affinity for CaM by competing with Ca2+ for metal binding sites and leading to structurally unfavorable CaM conformation for target binding (Ohki et al., 1997; Martin et al., 2000).

The structure of CaM consists of two globular domains that are connected by a flexible α-helical linker (Babu et al., 1988; Chattopadhyaya et al., 1992). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Ikura et al., 1992) and x-ray diffraction (Meador et al., 1992) studies on CaM complexed with the peptides from skeletal and smooth-muscle myosin light chain kinases have established that the domains are in close association with each other in CaM–target–Ca4 structures. The typical CaM–target–Ca4 structure contains a hydrophobic tunnel through the molecule. Only the ends of the peptide lie outside of the tunnel. The peptide is engulfed inside the hydrophobic cavity, making hydrophobic and electrostatic contacts with the globular domains of CaM. High affinity binding of different targets is promoted by the α-helical linker (Persechini and Kretsinger, 1988) and several methionine residues of CaM (Yuan et al., 1998). The hydrophobic interactions in CaM take place in hydrophobic pockets that accommodate bulky side chains of the target.

The model peptides derived from the CaM binding sequences of target proteins have been found to retain the high affinities and specificities of the proteins they mimic (Kilhoffer et al., 1992). The sequences contain long-chain hydrophobic and positively charged hydrophilic residues and adopt an α-helical conformation (O'Neil and DeGrado, 1990). Molecular modeling studies (Afshar et al., 1994) have used the NMR solution data (Ikura et al., 1992) as a basis for building the molecular model of synthetic CaM and RS20 peptide derived from the CaM-binding sequence of smooth-muscle myosin light chain kinase (smMLCK). The modeling has suggested that the CaM structure is able to accommodate large peptide variations due to the contributions of salt-bridges in the complex.

Numerous studies have shown the potential of electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry in probing protein complexes in their native conformations (see, for example, Hunter et al., 1997; Gao et al., 1999). Competition reactions between ligands of similar properties (Daniel et al., 2002; Jørgensen et al., 1998) and dissociation of noncovalent and other complexes in the gas-phase (Jørgensen et al., 1999a; Rostom et al., 2000) have given useful information on the affinities of the interactions in the absence of bulk solvent. Electrostatic interactions are generally considered to be more important for maintaining gas-phase noncovalent complexes than hydrophobic interactions (Robinson et al., 1996; Wu et al., 1997). Where, however, the ligand is buried in the interior of the protein and the hydrophobic interactions are shielded in the complex, hydrophobic interactions have been found to be as important as electrostatic interactions (Rostom et al., 2000).

In this article, the binding of peptides to calmodulin has been used as a model system in examining methods of determining relative binding affinities in solution by Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FTICR) and ESI. We have previously studied the association of CaM and the target peptide (RS20) in some depth by ESI and FTICR, both in the presence and in the absence of Ca2+ (Hill et al., 2000). With solution-phase competition reactions using pairs of RS20 analogs, we have estimated the relative binding affinities of the mutated peptides. The peptide analogs were chosen so as to probe the influence of electrostatic and hydrophobic mutations on the binding affinity of RS20. Experiments have also been performed in the presence of Mg2+ to test the influence of Mg2+ on binding of the peptides to CaM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry

Experiments were performed on an FTICR mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with a shielded 9.4 T superconducting magnet (Magnex Scientific, Abingdon, UK), a cylindrical infinity ICR cell with a 0.06-m diameter, and an external electrospray (ES) ion-source (Analytica of Branford, Branford, MA, USA). This FTICR mass spectrometer has been described previously (Palmblad et al., 2000). The flow rate of the sample solution into the ES ion-source was 0.83 μl min−1. To preserve the essential noncovalent interactions of CaM–peptide and CaM–peptide–Ca4 structures, the experimental parameters in the ES source were carefully controlled. The spray voltage in the front end of the glass capillary in the atmospheric-pressure region as well as the capillary potential (VC) and skimmer potential at the intermediate-pressure region were kept low in standard measurements. The dissociation experiments were performed by gradually increasing the capillary potential, which induced fragmentation of the complexes in the ion-source. Carbon dioxide was used as a drying gas in the ion-source, and its temperature and flow rate (200°C, 30 p.s.i., 500 kPa) were adjusted so that no decomposition of complexes took place upon desolvation. The ions were accumulated for 4 s in the intermediate hexapole ion trap. Short accumulation time was used to preclude unwanted collisional activation in the hexapole. Base pressure was 2 × 10−10 mbar in the ICR cell. The spectra were calibrated against a commercially available mixture of peptides (Hewlett-Packard, Vernon Hills, IL, USA) in the 622–2722 range of mass-to-charge (m/z) values. The experiments were performed 3–5 times to establish reproducibility of the results.

Formation and purification of calmodulin and synthetic peptides for mass spectral analysis

DNA-encoded CaM was produced and purified as previously described (Roberts et al., 1985; Craig et al., 1987), and the purity (∼99%) was checked by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electropohoresis (SDS-PAGE) and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Ultrapure water and plasticware washed in 1N HCl were used to minimize contamination in all experiments. Two milligrams of lyophilized CaM was dissolved in 1.5 ml of 5 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5.9) and desalted over a PD-10 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) equilibrated with ammonium acetate. Protein concentration was determined by UV absorption with a Jasco V-550 spectrophotometer using a molar extinction coefficient of 1560 M−1 cm−1 at 280 nm (Gilli et al., 1998).

The single-point mutated synthetic peptides that were derived from the phosphorylation site of smMLCK were produced and purified as previously described (Lukas et al., 1986; Guimard et al., 1994). The lyophilized peptides were diluted in 5 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.9 before addition of the protein) to the concentration of 1 mM, and appropriate aliquots of these peptide stock solutions were added to CaM solution to achieve desired CaM-to-peptide ratio. Typically, the CaM concentration was 20 μM and the peptide concentration 30 μM. At these concentrations, unspecific aggregation of protein and peptide was not detected. In peptide competition experiments, two peptides were added to CaM solution to reach the molar ratios of 1:1.5:1.5 CaM/peptide(A)/peptide(B). The concentration of CaCl2 and MgCl2 (Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) stock solutions was 10 mM. Small aliquots of metal cation stock solutions were added to CaM–peptide solutions to give desired CaCl2 and MgCl2 molar concentrations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mass spectra of calcium-free calmodulin and synthetic peptides

Studies using a combination of isothermal titration calorimetry and differential scanning calorimetry (Tsvetkov et al., 1999) and using ESI-FTICR mass spectrometry (Hill et al., 2000) showed that in the absence of Ca2+ CaM binds RS20, a synthetic peptide derived from the CaM-binding region of smMLCK. The interaction was suggested by Tsvetkov et al. (1999) to occur between RS20 and the C-terminal domain of CaM. The single point mutations of the RS20 sequence studied here represented conversions of amino acid residues located in the C-terminal half of RS20 to either bulkier or more hydrophobic residues. The amino acid sequences of RS20 and the mutants, with the theoretical and measured (in this study) molecular masses, are shown in Table 1. The interactions between CaM and RS20 in the presence of Ca2+ have been described before (Meador et al., 1992; Afshar et al., 1994), but the detailed interactions between Ca2+-free CaM and RS20 still remain unclear. R16L represents conversion of a residue that has a particular importance in electrostatic interactions between CaM and smMLCK (Meador et al., 1992; Afshar et al., 1994) to a residue expected not to provide electrostatic interactions. V11L, V11F, and A13L have mutations in residues that in aqueous solution are involved in contacts with the hydrophobic pockets of the binding interface of Ca2+-loaded CaM.

TABLE 1.

The amino acid sequences and the theoretical and experimentally measured monoisotopic masses of the peptides

| Peptide | Amino acid sequence | Theoretical mass (Da) | Experimental mass (Da) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RS20 | RRKWQKTGHAVRAIGRLSSS | 2293.2992 | 2293.3008 ± 0.0005 |

| V11F | RRKWQKTGHAFRAIGRLSSS | 2341.2992 | 2341.2978 ± 0.0004 |

| V11L | RRKWQKTGHALRAIGRLSSS | 2307.3148 | 2307.3096 ± 0.015 |

| A13L | RRKWQKTGHAVRLIGRLSSS | 2335.3461 | 2335.3458 ± 0.001 |

| R16L | RRKWQKTGHAVRAIGLLSSS | 2250.2821 | 2250.2801 ± 0.0003 |

The mutated residues are in bold. The experimental values are the mean ± standard deviation from five experiments.

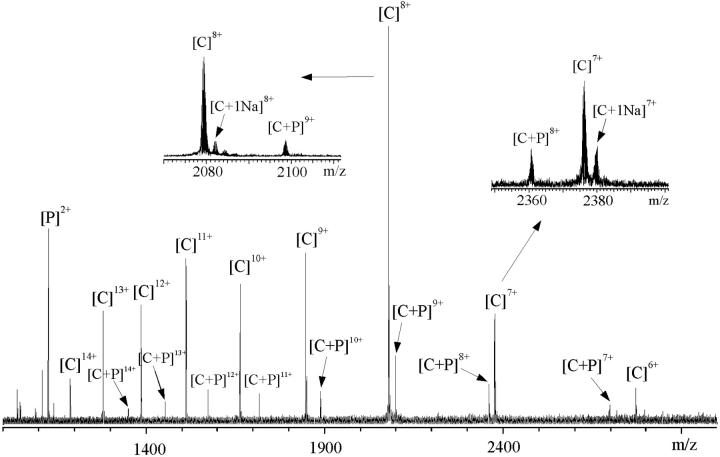

The mass spectrometric measurements evidenced unambiguously noncovalent association of every one of the peptides with Ca2+-free CaM. For example, the signal at m/z 2098.60 (Fig. 1) represented R16L bound to Ca2+-free CaM within the 9+ charge-state from which the experimental molecular mass of the complex was determined as 18,878.36 ± 0.07 Da. The theoretical mass of the noncovalent CaM–R16L complex (18,878.99 Da), obtained from the sequences, agreed well with the measured molecular mass of the complex. The stoichiometry of peptide binding was principally one peptide per one CaM. The charge distribution of the peptide-bound CaM was shifted to lower charge-states, in comparison to that of peptide-free CaM, and was centered around the 9+ charge-state (cf. the 8+ charge-state for CaM alone, and 3+ and 2+ for peptide alone, respectively) (Hill et al., 2000). The change by one in the charge-state series after formation of the CaM–peptide complex is consistent with the formation of salt-bridges between two moieties and partial burial of the peptide within the CaM structure. The minimal change in the charge-state distribution indicates that CaM structure remained similar to that of the peptide-free CaM. The result is consistent with the earlier results from small-angle x-ray scattering (Izumi et al., 2001) and from the combination of isothermal titration calorimetry and differential scanning calorimetry (Tsvetkov et al., 1999) that the binding of RS20 to Ca2+-free CaM does not induce or require a large-scale conformational change.

FIGURE 1.

ESI-FTICR mass spectrum of CaM with R16L peptide (concentration ration 1:1.5) in 5 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.9. Insets show the expansions of the 7+ and 8+ charge-states. C represents CaM and P represents peptide, respectively.

The affinity of a peptide for calmodulin is represented by the equilibrium constant K for the association:

|

(1) |

where CP denotes CaM–peptide complex, C calmodulin, and P peptide.

Relative affinities of peptides (denoted as P1 and P2) have been obtained from the intensities of CaM ions and complex ions in the spectra:

|

(2) |

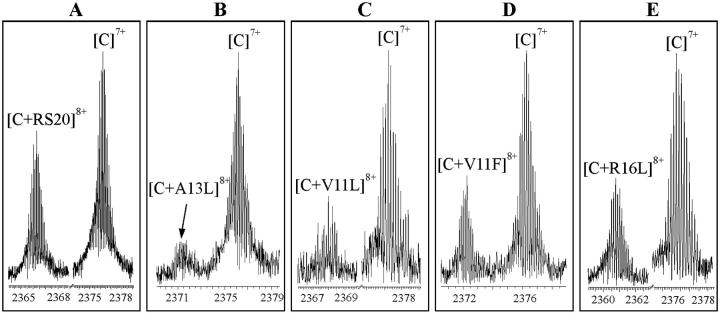

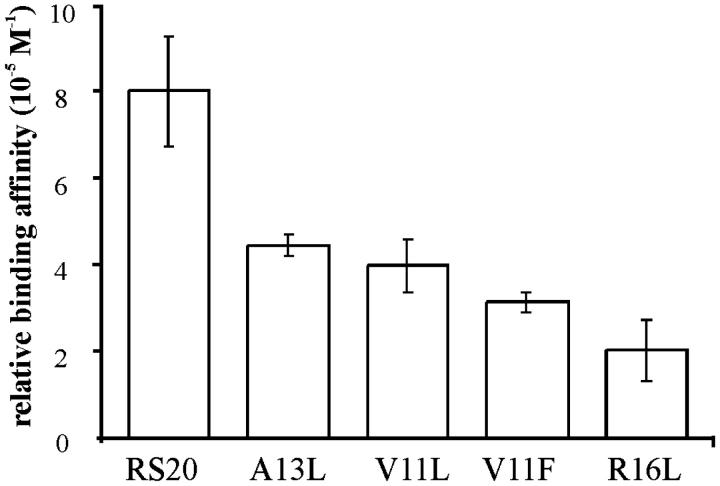

The peptide and RS20 concentrations have been considered to be equal to each other (both being close to their initial concentration 30 μM). The ratios of intensities of [CaM–peptide]8+ to [CaM]7+ have been taken as measures of the concentration ratios [CaM–peptide]/[CaM]. These ions represent the folded conformations of CaM–peptide complex and CaM. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 2 for RS20, A13L, V11L, V11F, and R16L. Determining the relative binding affinities in this way follows Jørgensen and co-workers (Jørgensen et al., 1998, 1999b), who went further and reported absolute values of association constants. The caveats to be noted are that comparisons are made between experiments, as each of the peaks in any pair in Fig. 2 represents a separate measurement. The second note of caution is that both the masses and the charges of the ions whose abundances were compared differed, and hence transmission efficiencies would have differed (Hunt et al., 1998). For this reason, we consider the method to be questionable for the determination of absolute binding constants. Fig. 3 shows the relative binding affinities. The comparison between RS20 and its mutated peptide analogs showed that mutations had an influence in decreasing the affinity of peptide to CaM. The complex of CaM with R16L had a considerably lower abundance than the corresponding RS20 complex. It has been proposed that in addition to the salt-link with glutamate 84 of CaM, arginine 16 hydrogen bonds with leucine 71 of CaM (Afshar et al., 1994) in the presence of Ca2+. Our results show that the electrostatic interaction from the basic arginine residue in the position 16 also contributes to the affinity of RS20 for Ca2+-free CaM. The V11F and V11L, which reflect the nonpolar interaction with CaM, showed affinities similar to those of R16L.

FIGURE 2.

Expanded ESI-FTICR mass spectra of CaM with (A) RS20, (B) A13L, (C) V11L, (D) V11F, and (E) R16L. The spectra were measured in 5 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.9, in the absence of CaCl2. The spectra show peaks originated from the CaM–peptide complexes at the 8+ charge-state and CaM at the 7+ charge-state in their actual intensities relative to each other.

FIGURE 3.

Stability in solution of the CaM–peptide complexes. The ratio was calculated using the relative intensities of signals corresponding to CaM–peptide complex at the 8+ charge-state and CaM at the 7+ charge-state. The values are the mean of three repeat experiments ± their standard deviation.

A13L showed the lowest binding affinity to CaM of all the peptides measured (in the absence of Ca2+). This mutation (A13L) concerns one of the bulky residues expected to interact and occupy one at the specific hydrophobic pockets of CaM. The mutation (A13L) renders the position slightly more bulky and hydrophobic, but it was expected that the pocket in the N-terminal domain of CaM would have been deep enough to accommodate the side chain of a leucine 13 in addition to that of leucine 17. The results indicate that this mutation had an unexpectedly large influence on the interaction between CaM and the target peptide (Ikura et al., 1992; Barth et al., 1998).

Mass spectra of calcium-loaded calmodulin and synthetic peptides

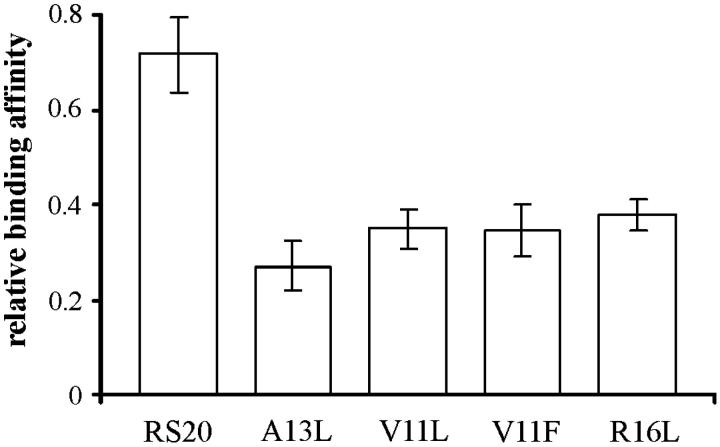

The binding of the peptides and calmodulin in the presence of calcium is strong, as is evident from the mass spectrum of R16L and CaM (Fig. 4). The method of determining relative binding affinities proposed here is suitable for study of the very stable CaM–peptide–Ca4 complexes. Solutions containing 1:1.5:5 CaM/peptide/CaCl2 molar ratios were measured. As expected, the presence of both Ca2+ and peptide had notable influence on folding of CaM. The unfolded conformations, represented by the high charge-states in the bimodal charge-state distribution from 16+ to 10+ of Ca2+-free CaM, disappeared (see Fig. 4). This indicated that CaM had adopted more folded structures. The CaM–peptide–Ca4 complex at the charge-states from 7+ to 9+ was detected in the spectra in the case of each peptide. The most abundant species was CaM–peptide–Ca4 at the 8+ charge-state. Only weak signals corresponding to CaM and CaM–Ca at the 7+ and 8+ charge-states, CaM–Ca2 at the 8+ charge-state and CaM–peptide and CaM–peptide–Ca at the charge-states from 7+ to 9+, were observed. No signal was obtained that corresponded to the complex of CaM–Ca4 (Hill et al., 2000). In addition, signals corresponding to the CaM–peptide complexes containing more than four Ca2+ (up to 10 Ca2+) confirmed that the protein has several additional binding sites for Ca2+ (Milos et al., 1989). There was some evidence of a preference for CaM–peptide–Ca7 complex. In the complexes detected, the binding of Ca2+ was associated formally with the loss of two protons. To simplify the representation of the species detected, the numbers of protons formally added or lost are not written in the labels of the figures. For example, [C + 4Ca]6+ represents [(CaM + 4Ca-8H) + 6H]6+.

FIGURE 4.

ESI-FTICR mass spectrum of CaM with R16L peptide (concentration ration 1:1.5) in 5 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.9, containing 0.1 mM CaCl2. Insets show the expansions of the 7+ and 8+ charge-states of CaM–R16L–Can and the 8+ charge-state of CaM.

Competition reactions

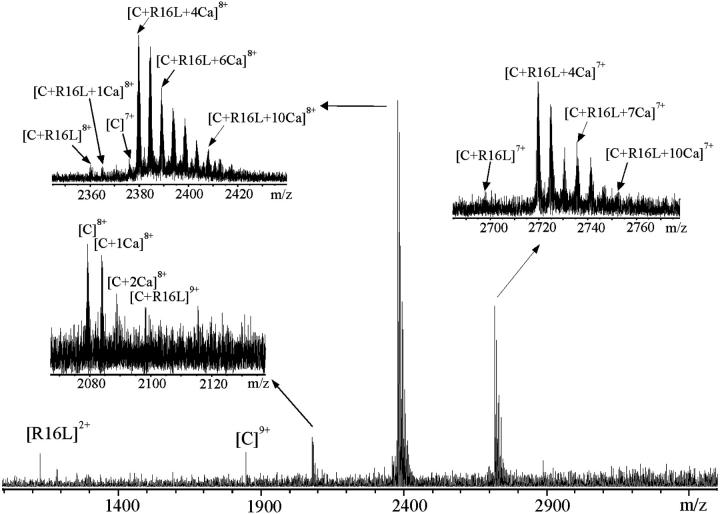

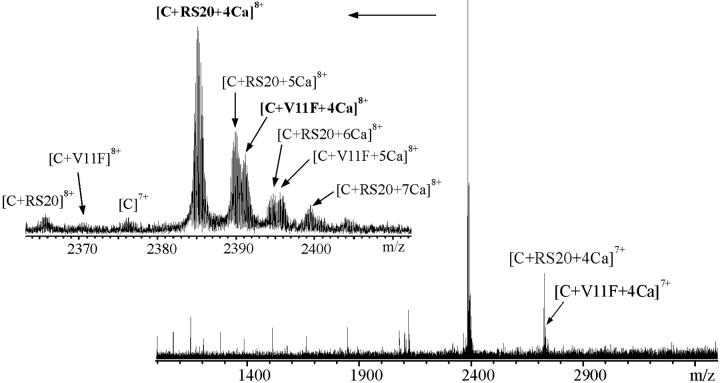

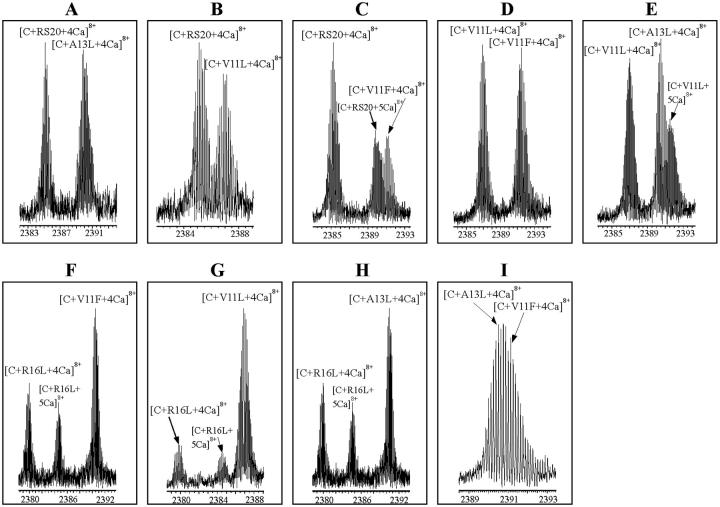

Binding competitions to CaM in solution were set up between pairs of peptides in the presence of Ca2+. Equimolar concentrations (30 μM) of two competing peptides and 20 μM CaM in the presence of CaCl2 (100 μM) in ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5.9) were mixed. The reaction mixture was measured immediately after sample preparation. The spectrum for V11F and RS20 is shown in Fig. 5. Fig. 6 shows the expanded mass spectra obtained from CaM–peptide–Ca4 complexes at the 8+ charge-state in competition reactions. The peaks originating from [CaM + A13L + 4Ca]8+ and [CaM + V11F + 4Ca]8+ (Fig. 6 I) partly overlap. After apodizing the spectra with Gaussian weighting functions, their intensities were calculated using an integral method for improving the shape of the isotopic patterns. The intensities of the peaks corresponding to different CaM–peptide–Ca4 complexes were aggregated and interpreted to correlate the relative affinities of the peptides (Fig. 7). Relative binding affinities KCP were calculated using the equilibrium concentrations of peptides and peptide complexes:

|

(3) |

KCP denotes the equilibrium constant for the reaction:

|

In the competitive situation, the concentration [C] of CaM, the calcium concentration [Ca2+], and the hydrogen ion concentration are common to the formation of the two complexes. Therefore, the ratio of the equilibrium constants reduce to Eq. 4:

|

(4) |

The concentrations have been obtained from the original intensities as follows:

|

(5) |

[C0] is the initial concentration of CaM in solution. Ci is the summed intensities of CaM in all states. CP1i is the summed intensities of complex with peptide 1 and CP2i the summed intensities of complex with peptide 2. The relationship of the concentration [C] to Ci has been used to obtain [CP1] and [CP2] from CP1i and CP2i, respectively. The concentrations of peptides [P1] and [P2] have been obtained from the initial concentrations of peptides [P1]0 and [P2]0 and the complex concentrations (i.e., [P1] + [CP1] = [P1]0 and [P2] + [CP2] = [P2]0).

FIGURE 5.

ESI-FTICR mass spectrum of CaM with V11F and RS20 peptides (concentration ratio 1:1.5:1.5) in ammonium acetate buffer, 5 mM, pH 5.9, containing 0.1 mM CaCl2. Inset shows the expansion of the 8+ charge-state. C represents CaM.

FIGURE 6.

Expanded ESI-FTICR mass spectra showing competition reactions of pairs of peptides: (A) RS20 and A13L, (B) RS20 and V11L, (C) RS20 and V11F, (D) V11L and V11F, (E) V11L and A13L, (F) R16L and V11F, (G) R16L and V11L, (H) R16L and A13L, and (I) A13L and V11F. CaM/peptide1/peptide2/CaCl2 concentration ratio was 1:1.5:1.5:5 in 5 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.9. The spectra show peaks originated from the CaM–peptide–Ca4 complexes at the 8+ charge-state.

FIGURE 7.

Relative affinities in solution of the RS20, A13L, V11L, V11F, and R16L peptides in the presence of calcium. The ratio of CaM, peptide1, peptide2, and CaCl2 was 1:1.5:1.5:5 in competition reactions. The relative intensities of CaM–peptide–Ca4 complexes at the 8+ charge-state were used for calculation. The values are the mean of three repeat experiments ± their standard deviation.

The result with the A13L peptide in the presence Ca2+ showed a substantial difference compared to that in the absence of Ca2+. A13L was found to have the lowest binding affinity of all peptides used for CaM in the absence of Ca2+; in the presence of Ca2+, the incorporation of A13L into CaM was strong. These results regarding the influence of Ca2+ on the relative binding affinities of the peptides are in accordance with the hypothesis that the affinity derived from hydrophobic interactions of CaM and peptide is enhanced by Ca2+ binding (Ikura et al., 1992).

The result in the presence of Ca2+ with R16L, which lacks one of the electrostatic contacts with CaM, contrasts with the result for the CaM–R16L complex in the absence of Ca2+. We suggest that the reason for this strong influence of mutation R16L on the binding affinity of the peptide is the transformation in the interactions between CaM and the target peptide upon Ca2+ binding. The findings imply that the contribution of arginine 16 becomes important for the complex in the presence of Ca2+.

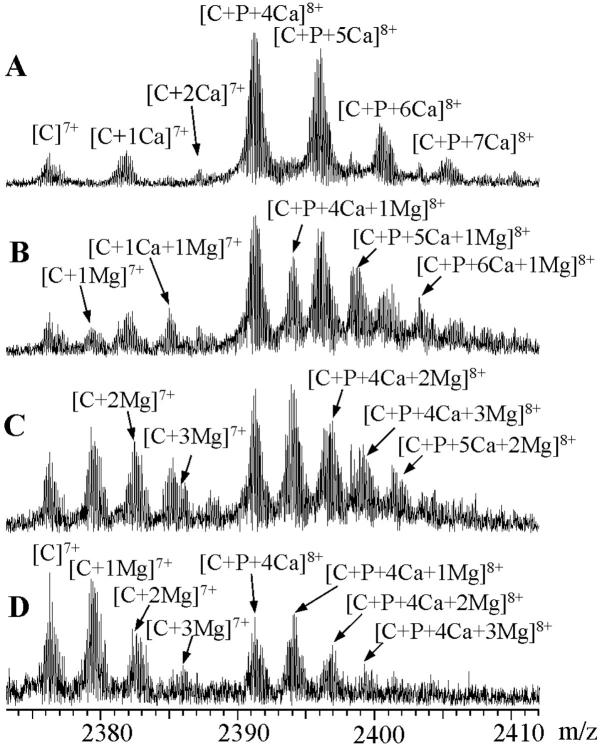

Peptide binding in the presence of Ca2+ and Mg2+

The influence of Mg2+ binding on the stability of CaM–peptide–Ca4 complex was studied by gradually adding MgCl2 solution to the sample mixture of CaM, peptide, and CaCl2 (molar ratio 1:1.5:5) in 5 mM ammonium acetate buffer. Fig. 8 shows the ESI-FTICR mass spectra obtained after the addition of MgCl2 to a solution containing V11F peptide. The spectra are expanded to show the changes in peak intensities at the 8+ charge-state of CaM–V11F–Ca4 and at the 7+ charge-state of CaM. Panels A and B show the mass spectra measured for solutions containing 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 0.1 mM CaCl2/0.05 mM MgCl2. Upon initial addition of MgCl2, the new peaks arose between those corresponding to Ca2+-containing species and evidenced association of Mg2+. Further addition of MgCl2 resulted in decreases in the intensities of CaM–peptide–Ca4 species and, in proportion, increases in the intensities of species containing one or more Mg2+ ions (Fig. 8, C and D). With 0.1 mM MgCl2 and 0.01 mM CaCl2, the ESI mass spectrum resembled that of CaM in the absence of metal, in that the strongest peak was due to CaM at the 8+ charge-state, suggesting that the protein's conformation had changed. Mg2+ was bound to [CaM]7+ in the same stoichiometries as it was to [CaM–peptide–Ca4]8+. There was evidence of CaM and CaM–peptide–Ca4 binding up to at least three Mg2+. In contrast to Ca2+ binding, there was no preference for 1:4 stoichiometry of CaM/Mg2+ or 1:1:4 stoichiometry of CaM/peptide:Mg2+.

FIGURE 8.

ESI-FTICR mass spectra showing the 8+ charge-state of CaM with V11F peptide (concentration ratio 1:1.5) in ammonium acetate buffer, 5 mM, pH 5.9, containing (A) 0.1 mM CaCl2, (B) 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 0.05 mM MgCl2, (C) 0.05 mM CaCl2 and 0.1 mM MgCl2, and (D) 0.01 mM CaCl2 and 0.1 mM MgCl2. C represents CaM and P peptide, respectively.

Gas-phase complexes

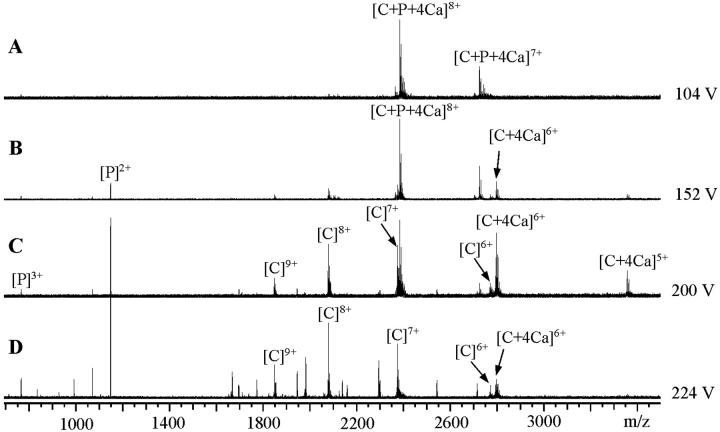

To assess the gas-phase stability and hence the relative likelihoods of dissociation of CaM–peptide–Ca4 complexes, the dissociation of CaM–peptide–Ca4 complexes was studied by gradually increasing the potential applied to the capillary in the ion-source. The molar ratios of CaM to peptide to CaCl2 were 1:1.5:5. Fig. 9 shows typical spectra representing the dissociation of the CaM–RS20–Ca4 complex at different capillary potentials. Fig. 9 A shows the initial stage of the experiment under low-energy conditions where no decomposition of the complex had taken place. After an increase in the capillary potential (Fig. 9 B), there was CaM–Ca4 complex within the 6+ and 5+ charge-states and peptide alone within the 2+ charge-state, indicating that the CaM–RS20–Ca4 complex initially dissociated into CaM–Ca4 and RS20. This result is consistent with results for CaM–RS20–Ca4 obtained by sustained off-resonance irradiation collision-induced dissociation (SORI CID) (Nousiainen et al., 2001). When the capillary potential was further increased, the intensities of the peaks corresponding to CaM–Ca4 and peptide rose (Fig. 9 C). At the highest capillary potential, no CaM–RS20–Ca4 was observed (Fig. 9 D), indicating that the complex had totally dissociated. As the capillary potential was increased, there were increases in the intensities of peaks corresponding to Ca2+-free CaM at the charge-states from 6+ to 10+ and peptide alone at the 3+ and 2+ charge-states. Complexes of CaM with one to seven Ca2+ were detected only at low intensities indicating that in harsh conditions the removal of Ca2+ from the protein had taken place. In addition, CaM fragments showed that the protein primary structure had been decomposed at the highest capillary potentials. The dissociation took place in the same way qualitatively with all of the peptides, producing ions corresponding to CaM–Ca4, CaM, peptide, and CaM-fragments.

FIGURE 9.

The ion-source collision-induced-dissociation of CaM–RS20–Ca4 complex (concentration ratio 1:1.5:5) in 5 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.9. (A)–(D) were measured on the sample using the ES capillary potentials from 104 V to 224 V. (A) shows the ESI-FTICR mass spectrum of the intact complex. The increase of the capillary potential from 104 V to 152 V (indicated in (B)) results in the decomposition of the complex to CaM–Ca4 and RS20. Further increase of the capillary potential leads to the decomposition of CaM–Ca4 (C) and fragmentation of CaM backbone (D). C represents CaM and P peptide, respectively.

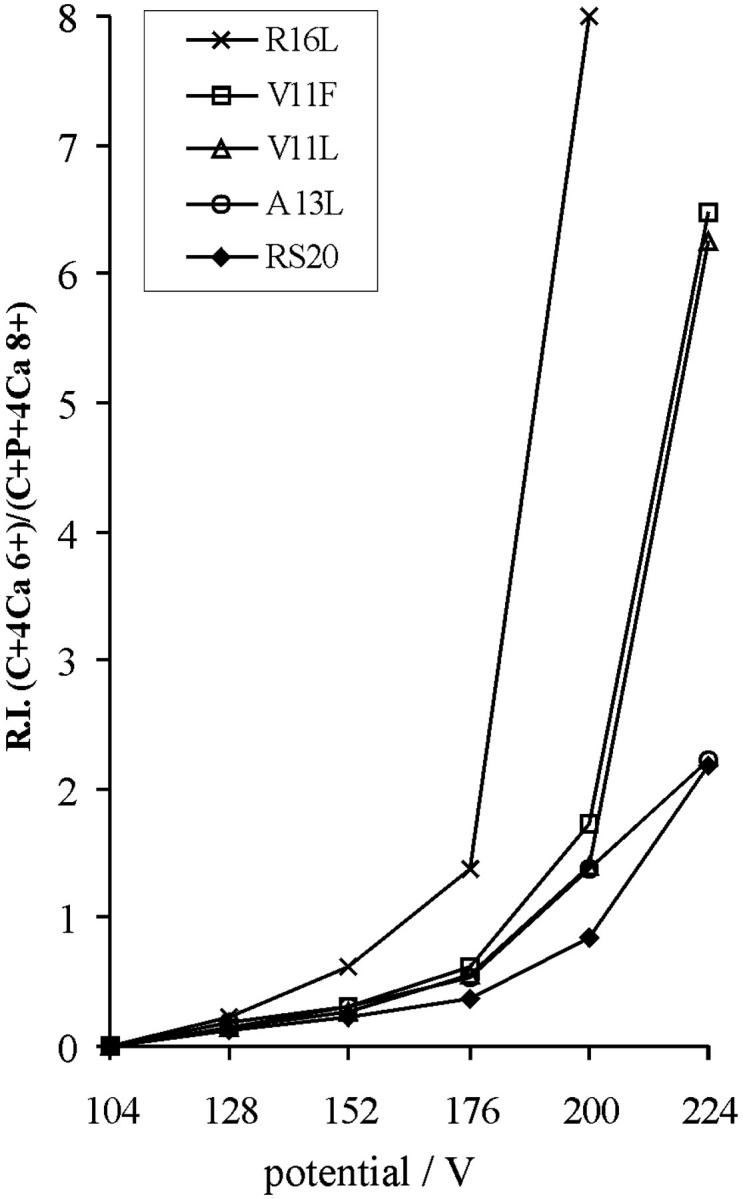

The spectra measured using different peptides varied from each other in regard to the relative abundances of the peptide-bound and peptide-free CaM species under increasing capillary potential. These differences reflect different relative affinities in the gas-phase of peptides for CaM in CaM–peptide–Ca4. The relative gas-phase affinities of the peptides were estimated from the ratios of the relative intensities of [CaM + 4Ca]6+ and [CaM + peptide + 4Ca]8+. Fig. 10 plots the ratio of relative intensities of [CaM + 4Ca]6+ and [CaM + peptide + 4Ca]8+ versus the potential applied to the capillary of the ion-source. The selection of [CaM + peptide + 4Ca]8+ and [CaM + 4Ca]6+ was based on our previous observation that the SORI-CID of CaM–RS20–Ca4 produced doubly and triply charged RS20, and CaM–Ca4 at the charge-state two and three less than that of the complex (Nousiainen et al., 2001). The ratio of [CaM + 4Ca]6+ and [CaM + RS20 + 4Ca]8+ remained lowest at all capillary potentials, demonstrating that in the gas-phase RS20 peptide had the highest affinity for CaM in the presence of Ca2+. The curve representing CaM–V11L–Ca4 was parallel with that for the V11F peptide. The curve representing CaM–A13L–Ca4 complex showed that A13L has an affinity slightly higher than those of V11L and V11F but lower than that of RS20. R16L was lost from its CaM–peptide–Ca4 at lower capillary potentials than the other peptides. Of the mutated amino acid residues in the peptide sequence, it was concluded that the basic arginine 16 played a more important role in the gas-phase than the nonpolar valine 11 and alanine 13.

FIGURE 10.

Stability in the gas-phase of the CaM–peptide–Ca4 complexes shown as a function of capillary potential. The ratio was calculated using the relative intensities of signals corresponding to CaM–peptide–Ca4 complex at the 8+ charge-state and CaM–Ca4 at the 6+ charge-state. C represents CaM and P peptide, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Consideration of findings on peptide–CaM complexes in the absence of Ca2+ demonstrated that the conversion of alanine at position 13 to the structurally larger and more hydrophobic leucine diminished the binding in solution of peptide to CaM. In the presence of Ca2+ this mutation did not have such a great influence. With Ca2+ present, it is concluded that conformational changes made possible the incorporation of hydrophobic residue 13 irrespective of its size, and increased the contributions of hydrophobic interactions between CaM and its target. Conversion of residue 16 from polar arginine to hydrophobic leucine demonstrated that arginine 16 was more important to the interaction between target and CaM in the presence of Ca2+ than in the absence of Ca2+.

The results with Mg2+ showed that Mg2+ diminished the binding in solution of the target peptides within the CaM–peptide–Ca4 complexes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. R. Toci for production and purification of synthetic CaM and Dr. B. Calas for synthesis of the peptides.

This work was supported by grants from the Graduate School of Bioorganic Chemistry (Ministry of Education, Finland), Academy of Finland (44906), and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) (88/9708907). The University of Warwick FTICR mass spectrometry facility was a UK National Facility supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

References

- Afshar, M., L. S. D. Caves, L. Guimard, R. E. Hubbard, B. Calas, G. Grassy, and J. Haiech. 1994. Investigating the high affinity and low sequence specificity of calmodulin binding to its targets. J. Mol. Biol. 244:554–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu, Y. S., C. E. Bugg, and W. J. Cook. 1988. Structure of calmodulin refined at 2.2 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 204:191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth, A., S. R. Martin, and P. M. Bayley. 1998. Specificity and symmetry in the interaction of calmodulin domains with the skeletal muscle myosin light chain kinase target sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 273:2174–2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyaya, R., W. E. Meador, A. R. Means, and F. A. Quiocho. 1992. Calmodulin structure refined at 1.7 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 228:1177–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, T. A., D. M. Watterson, F. G. Prendergast, J. Haiech, and D. M. Roberts. 1987. Site-specific mutagenesis of the alpha-helices of calmodulin. Effects of altering a charge cluster in the helix that links the two halves of calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 262:3278–3284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crivici, A., and M. Ikura. 1995. Molecular and structural basis of target recognition by calmodulin. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 24:85–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, J. M., S. D. Friess, S. Rajagopalan, S. Wendt, and R. Zenobi. 2002. Quantitative determination of noncovalent binding interactions using soft ionization mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 216:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J., Q. Wu, J. Carbeck, Q. P. Lei, R. D. Smith, and G. M. Whitesides. 1999. Probing the energetics of dissociation of carbonic anhydrase-ligand complexes in the gas phase. Biophys. J. 76:3253–3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilli, R., D. Lafitte, C. Lopez, M. C. Kilhoffer, A. Makarov, C. Briand, and J. Haiech. 1998. Thermodynamic analysis of calcium and magnesium binding to calmodulin. Biochemistry. 37:5450–5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimard, L., M. Afshar, J. Haiech, and B. Calas. 1994. A protein/peptide assay using peptide-resin adduct: application to the calmodulin/RS20 complex. Anal. Biochem. 221:118–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, T. J., D. Lafitte, J. I. Wallace, H. J. Cooper, P. O. Tsvetkov, and P. J. Derrick. 2000. Calmodulin-peptide interaction: apocalmodulin binding to the myosin light chain kinase target site. Biochemistry. 39:7284–7290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S. M., M. M. Sheil, M. Belov, and P. J. Derrick. 1998. Probing the effects of cone potential in the electrospray ion source: consequences for the determination of molecular weight distributions of synthetic polymers. Anal. Chem. 70:1812–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, C. L., A. G. Mauk, and D. J. Douglas. 1997. Dissociation of heme from myoglobin and cytochrome b5: comparison of behavior in solution and the gas phase. Biochemistry. 36:1018–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura, M., G. M. Clore, A. M. Gronenborn, G. Zhu, C. B. Klee, and A. Bax. 1992. Solution structure of a calmodulin-target peptide complex by multidimensional NMR. Science. 256:632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi, Y., S. Kuwamoto, Y. Jinbo, and H. Yoshino. 2001. Increase in the molecular weight and radius of gyration of apocalmodulin induced by binding of target peptide: evidence for complex formation. FEBS Lett. 495:126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, T. J. D., P. Roepstorff, and A. J. R. Heck. 1998. Direct determination of solution binding constants for noncovalent complexes between bacterial cell wall peptide analogues and vancomycin group antibiotics by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 70:4427–4432. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, T. J. D., D. Delforge, J. Remacle, G. Bojesen, and P. Roepstorff. 1999a. Collision-induced dissociation of noncovalent complexes between vancomycin antibiotics and peptide ligand stereoisomers: evidence for molecular recognition in the gas phase. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 188:63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, T. J. D., T. Staroske, P. Roepstorff, D. H. Williams, and A. J. R. Heck. 1999b. Subtle differences in molecular recognition between modified glycopeptide antibiotics and bacterial receptor peptides identified by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2:1859–1863. [Google Scholar]

- Kilhoffer, M. C., T. J. Lukas, D. M. Watterson, and J. Haiech. 1992. The heterodimer calmodulin: myosin light-chain kinase as a prototype vertebrate calcium signal transduction complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1160:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas, T. J., W. H. Burgess, F. G. Prendergast, W. Lau, and D. M. Watterson. 1986. Calmodulin binding domains: characterization of a phosphorylation and calmodulin binding site from myosin light chain kinase. Biochemistry. 25:1458–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. R., L. Masino, and P. M. Bayley. 2000. Enhancement by Mg2+ of domain specificity in Ca2+-dependent interactions of calmodulin with target sequences. Protein Sci. 9:2477–2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador, W. E., A. R. Means, and F. A. Quiocho. 1992. Target enzyme recognition by calmodulin: 2.4 A structure of a calmodulin-peptide complex. Science. 257:1251–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milos, M., M. Comte, J. J. Schaer, and J. A. Cox. 1989. Evidence for four capital and six auxiliary cation-binding sites on calmodulin: divalent cation interactions monitored by direct binding and microcalorimetry. J. Inorg. Biochem. 36:11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzoeva, S., S. Weigand, T. J. Lukas, L. Shuvalova, W. F. Anderson, and D. M. Watterson. 1999. Analysis of the functional coupling between calmodulin's calcium binding and peptide recognition properties. Biochemistry. 38:3936–3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nousiainen, M., X. Feng, P. Vainiotalo, and P. J. Derrick. 2001. Calmodulin-RS20-Ca4 complex in the gas phase: electrospray ionisation and Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 7:393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Ohki, S., U. Iwamoto, S. Aimoto, M. Yazawa, and K. Hikichi. 1993. Mg2+ inhibits formation of 4Ca2+-calmodulin-enzyme complex at lower Ca2+ concentration. 1H and 113Cd NMR studies. J. Biol. Chem. 268:12388–12392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki, S., M. Ikura, and M. Zhang. 1997. Identification of Mg2+-binding sites and the role of Mg2+ on target recognition by calmodulin. Biochemistry. 36:4309–4316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neil, K. T., and W. F. DeGrado. 1990. How calmodulin binds its targets: sequence independent recognition of amphiphilic alpha-helices. Trends Biochem. Sci. 15:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmblad, M., K. Håkansson, P. Håkansson, X. Feng, H. J. Cooper, A. E. Giannakopulos, P. S. Green, and P. J. Derrick. 2000. A 9.4 T Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer: description and performance. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 6:267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Persechini, A., and R. H. Kretsinger. 1988. The central helix of calmodulin functions as a flexible tether. J. Biol. Chem. 263:12175–12178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, D. M., R. Crea, M. Malecha, G. Alvarado-Urbina, R. H. Chiarello, and D. M. Watterson. 1985. Chemical synthesis and expression of a calmodulin gene designed for site-specific mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 24:5090–5098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C. V., E. W. Chung, B. B. Kragelund, J. Knudsen, R. T. Aplin, F. M. Poulsen, and C. M. Dobson. 1996. Probing the nature of noncovalent interaction by mass spectrometry. A study of protein–CoA ligand binding and assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118:8646–8653. [Google Scholar]

- Rostom, A. A., J. R. H. Tame, J. E. Ladbury, and C. V. Robinson. 2000. Specificity and interactions of the protein OppA: partitioning solvent binding effects using mass spectrometry. J. Mol. Biol. 296:269–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetkov, P. O., I. I. Protasevich, R. Gilli, D. Lafitte, V. M. Lobachov, J. Haiech, C. Briand, and A. A. Makarov. 1999. Apocalmodulin binds to the myosin light chain kinase calmodulin target site. J. Biol. Chem. 274:18161–18164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q., J. Gao, D. Joseph-McCarthy, G. B. Sigal, J. E. Bruce, G. M. Whitesides, and R. D. Smith. 1997. Carbonic anhydrase–inhibitor binding: from solution to the gas phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119:1157–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, T., A. M. Weljie, and H. J. Vogel. 1998. Tryptophan fluorescence quenching by methionine and selenomethionine residues of calmodulin: orientation of peptide and protein binding. Biochemistry. 37:3187–3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]