Abstract

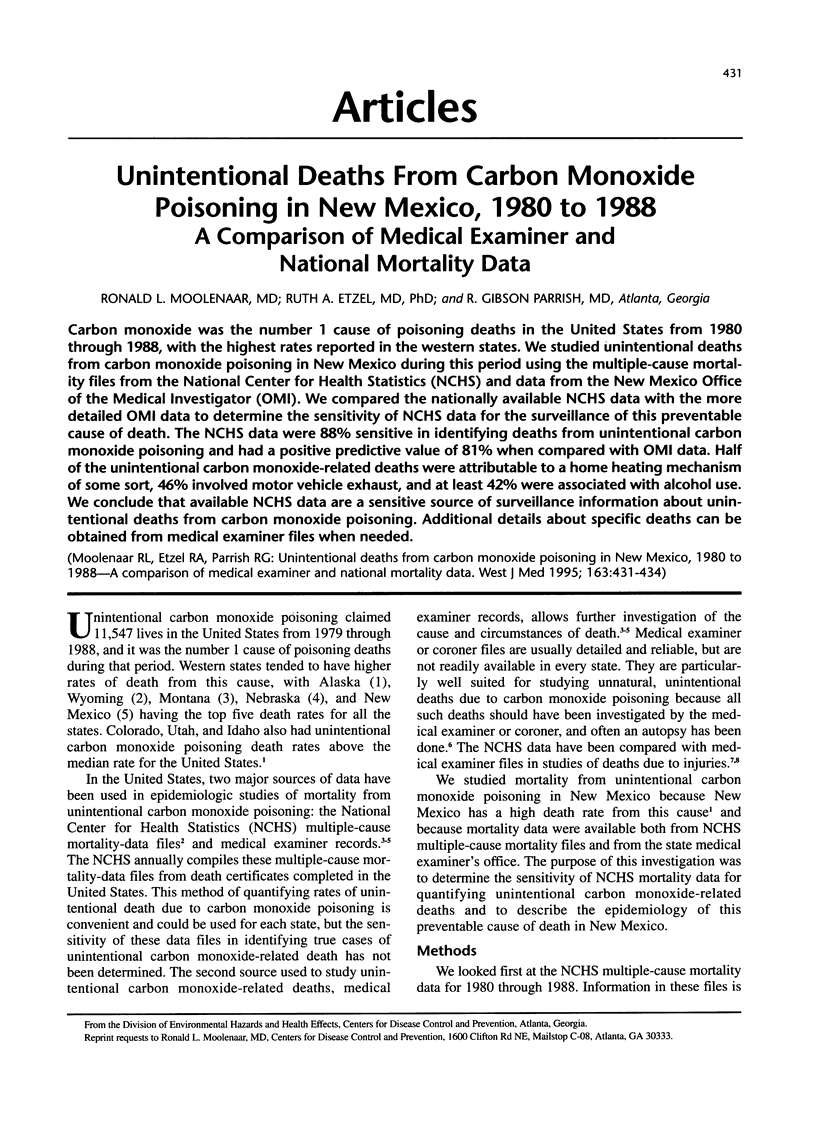

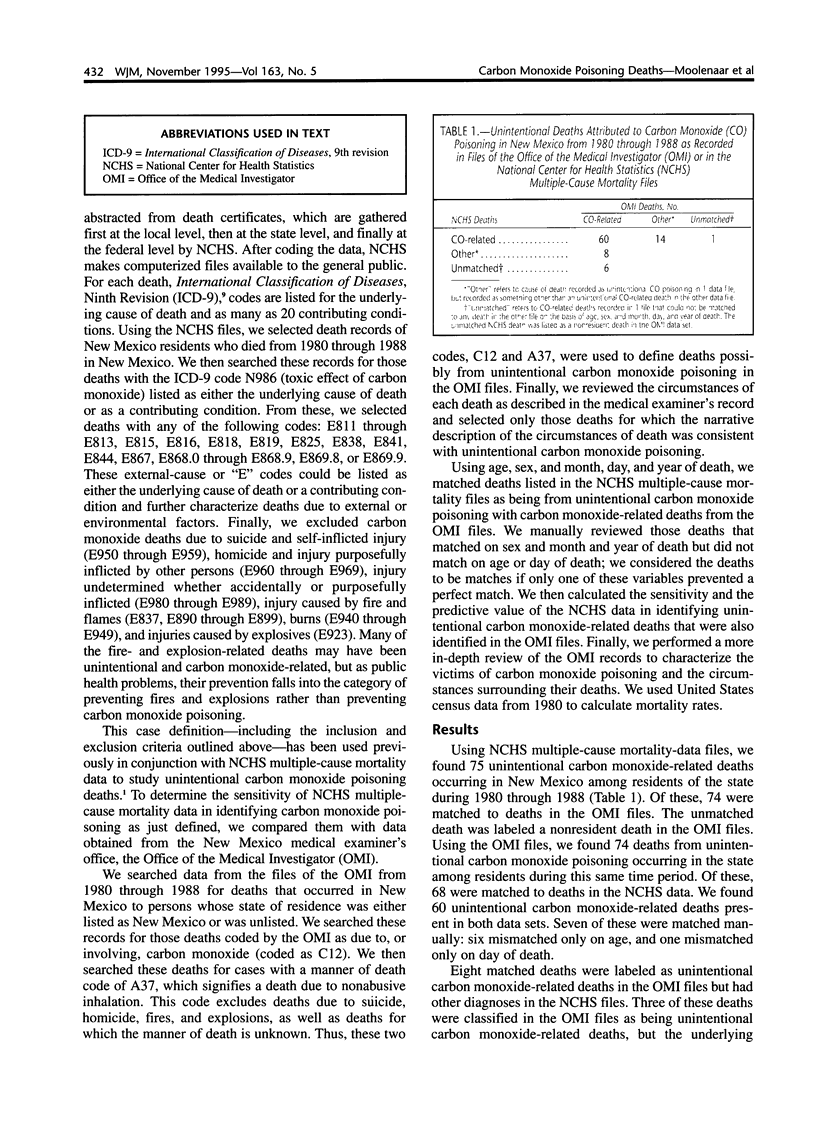

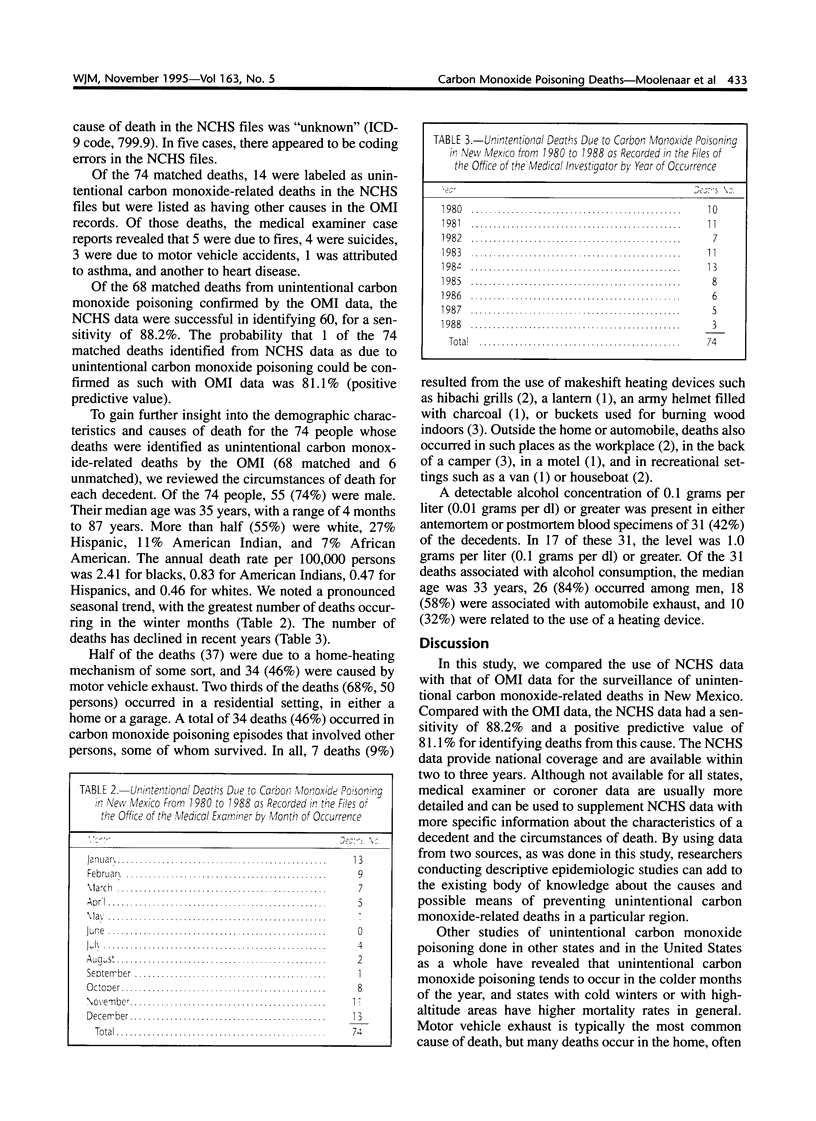

Carbon monoxide was the number 1 cause of poisoning deaths in the United States from 1980 through 1988, with the highest rates reported in the western states. We studied unintentional deaths from carbon monoxide poisoning in New Mexico during this period using the multiple-cause mortality files from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and data from the New Mexico Office of the Medical Investigator (OMI). We compared the nationally available NCHS data with the more detailed OMI data to determine the sensitivity of NCHS data for the surveillance of this preventable cause of death. The NCHS data were 88% sensitive in identifying deaths from unintentional carbon monoxide poisoning and had a positive predictive value of 81% when compared with OMI data. Half of the unintentional carbon monoxide-related deaths were attributable to a home heating mechanism of some sort, 46% involved motor vehicle exhaust, and at least 42% were associated with alcohol use. We conclude that available NCHS data are a sensitive source of surveillance information about unintentional deaths from carbon monoxide poisoning. Additional details about specific deaths can be obtained from medical examiner files when needed.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baker M. D., Henretig F. M., Ludwig S. Carboxyhemoglobin levels in children with nonspecific flu-like symptoms. J Pediatr. 1988 Sep;113(3):501–504. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80638-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. C., Backer R. C., Sopher I. M. Fatal unintended carbon monoxide poisoning in West Virginia from nonvehicular sources. Am J Public Health. 1989 Dec;79(12):1656–1658. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.12.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. C., Backer R. C., Sopher I. M. Unintentional deaths from carbon monoxide in motor vehicle exhaust: West Virginia. Am J Public Health. 1989 Mar;79(3):328–330. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.3.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb N., Etzel R. A. Unintentional carbon monoxide-related deaths in the United States, 1979 through 1988. JAMA. 1991 Aug 7;266(5):659–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkhuis H., Zwerling C., Parrish G., Bennett T., Kemper H. C. Medical examiner data in injury surveillance: a comparison with death certificates. Am J Epidemiol. 1994 Mar 15;139(6):637–643. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D. E., Sacks J. J., Parrish R. G., Sosin D. M., McFeeley P., Smith S. M. Sensitivity of multiple-cause mortality data for surveillance of deaths associated with head or neck injuries. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1993 Nov 19;42(5):29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan C. W., Bangdiwala S. I., Linzer M. A., Sacks J. J., Butts J. Risk factors for fatal residential fires. N Engl J Med. 1992 Sep 17;327(12):859–863. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209173271207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]