Abstract

We studied the diffusion of native and trypsinized nucleosome core particles (NCPs), in aqueous solution and in concentrated DNA solutions (0.25–100 mg/ml) using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS). The highest DNA concentrations studied mimic the DNA density inside the cell nucleus. The diffusion coefficient of freely diffusing NCPs depends on the presence or absence of histone tails and is affected by the salt concentration due to the relaxation effect of counterions. NCPs placed in a network of long DNA molecules (30–50 kbp) reveal anomalous diffusion. We demonstrate that NCPs diffusion is in agreement with known particle transport in entangled macromolecular solutions as long as the histone tails are folded onto the particles. In contrast, when these tails are unfolded, the reversible adsorption of NCPs onto the DNA network has to be taken into account. This is confirmed by the fact that removal of the tails leads to reduction of the interaction between NCPs and the DNA network. The findings suggest that histone tail bridging plays an important role in chromatin dynamics.

INTRODUCTION

The genome of eukaryotic organisms is physically organized in a DNA-protein complex called chromatin whose structure and dynamics are known to play an important role in gene expression. Recently, there has been an increasing interest to study the structure of chromatin in order to unravel the structure-function relation (Widom, 1998). Currently, very little is known about the dynamics of chromatin. Considering the level of the nucleosome formed by the wrapping of two turns of DNA around a histone octamer, the presence of histones and, more precisely, the coiling of DNA around the histones represses the genetic activity as it occludes binding sites of proteins (Morse, 1989). The displacement and positioning of histones became an important issue of research since the discovery of chromatin remodeling enzymes which are known to displace the histone core (Varga-Weisz and Becker, 1998).

For a first approach, we undertake to address in this article the histone dynamics by looking at the self-diffusion of isolated nucleosome core particles in aqueous solutions and in concentrated DNA solutions. A DNA concentration range from 0.25 to 100 mg/ml is supposed to mimic physiological DNA concentrations in the cell nucleus. It is generally accepted that the DNA concentrations in vivo varies from 50 to 250 mg/ml depending on the phase of the cell cycle, and the monovalent salt concentrations range from a few to 150 mM. We have chosen fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) as a tool to probe the NCPs dynamics. FCS measures the fluorescent light emitted from individual particles excited through a very small illuminated volume. The diffusion coefficients of particles are obtained from the time autocorrelation function of the particle number fluctuations inferred from the fluctuating signal. With the improvement of the signal-to-noise ratio and single molecule detection (Eigen and Rigler, 1994), FCS has been widely used to study the diffusion of single molecules in solution. In addition, coupling FCS with confocal microscopy allows direct measurements inside cells. Previously, experiments were performed in vivo to measure the diffusion of small DNA molecules in the cell (Lukacs et al., 2000). In our experiments, FCS has the advantage that NCPs can be specifically labeled and hence their diffusion can be followed in a complex environment such as concentrated DNA solutions. In addition, FCS is ideal for studying low NCP concentrations where it is safe to neglect the interactions among NCPs. This allows us to effectively study the chemical kinetics of isolated NCP within this environment.

We treat NCPs as a colloidal system, however, some generic properties of NCPs have to be taken into account. Previous studies have shown that NCPs can change their conformation. The basic terminal part of the proteins, generally called “histone tails,” were found to be able to entangle out of the histone core depending on the salt concentration of the solution (Mangenot et al., 2002a). This conformation change is known to contribute to the repression of the chromatin activity (Kornberg and Lorch, 1999) by allowing the folding or unfolding of the chromatin fiber (Garcia-Ramirez et al., 1992). From a dynamic point of view, histone-tail modifications, such as acetylation, phosphorylation, or methylation, are necessary to allow the activity of the chromatin remodeling complex (for a review see Peterson, 2000). In the following, we will demonstrate that the diffusion of NCPs in a concentrated DNA solution is governed by the histone tails. After introduction of the materials and methodical aspects, we show freely diffusing NCPs as a function of salt and trypsinisation. These findings are then used to interpret the diffusion of NCPs in concentrated DNA solutions.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Preparation of nucleosome core particles

Nucleosome core particles were prepared from native calf thymus chromatin as previously described (Mangenot et al., 2002a). H1-depleted chromatin was digested by micrococcal nuclease (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and purified by chromatography over a Sephacryl S-300 HR column (Pharmacia). The fraction corresponding to the mononucleosomes was collected and dialyzed against TE buffer (10mM Tris-HCl, 1mM EDTA, pH 7.6). NCPs were concentrated by ultrafiltration, under nitrogen pressure, through a nitrocellulose membrane (Amicon YM100) up to a concentration of 10 mg/ml. The absence of contaminating oligo-nucleosomes and the integrity of the particles were carefully checked. The DNA associated with the histone core displayed a length of 146 ± 3 base pairs (bp).

The ionic environment of particles was varied over a wide range. The final monovalent salt concentration (Cs) taking into account the Tris+ and Na+ ions, was varied from 10 to 200 mM. Samples were prepared by dilution of the stock solution to a concentration of 0.2 mg/ml (0.5 mg/ml in some cases), in the appropriate buffer, to reach the desired Cs values.

Preparation of trypsinized nucleosome core particle

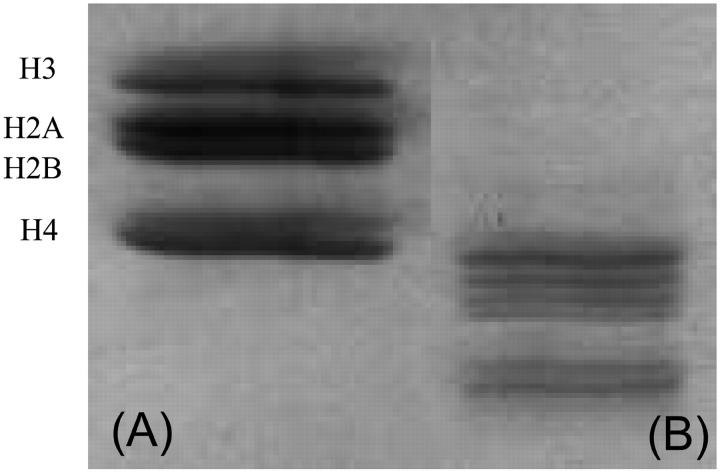

A fraction of the intact NCPs was digested by immobilized trypsin, according to a protocol previously described (Ausio and Van Holdes, 1989). Fig. 1 shows an SDS-15% polyacrylamide gel to analyze the histone composition of the sample. The native nucleosome core particles show four different bands corresponding to the intact histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. After trypsin digestion, these bands are shifted to lower molecular weight corresponding to the digestion of the histone tails.

FIGURE 1.

SDS-15% PAGE gel electrophoresis, stained with Silver. For (A) native nucleosome core particle and (B) after trypsin digestion: The bands are shifted to lower molecular weight

After digestion, the particles were extensively dialyzed against TE buffer and concentrated by ultrafiltration (Amicon YM100) to a concentration of 3 mg/ml. The samples were prepared by dilution of the stock solution in the appropriate buffer to a final NCP concentration of 0.2 mg/ml.

Preparation of DNA

Long DNA, prepared from calf thymus chromatin, with a length ranging from 30 to 50 kbp was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany) and purified using a standard phenol extraction to remove any traces of residual proteins. After purification, the DNA was diluted to a DNA concentration <1 mg/ml and extensively dialyzed against TE buffer to remove any excess of salt, and dried. The final concentrations, ranging from 1 to 200 mg/ml, were prepared by dissolving the DNA in one of the three salt concentrations studied (Cs = 10, 100, or 400 mM).

30-bp oligonucleotide DNA was purchased from MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany), and diluted in buffer to a final concentration of 0.02 mg/ml.

Sample preparation

Nucleosome core particles were labeled using an intercalating dimeric cyanine nucleic acid dye, Toto-1 or Toto-3 with absorption/emission wavelengths of 514/533 and 642/660 respectively (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Samples were always labeled at least 12 h before performing the experiments. On average, only one of ten particles was labeled. For example, 150 μl of NCP solution at 0.2 mg/ml (1 μM) were mixed with 150 μl of Toto-3 at 0.1 μM.

For diffusion in the network, 150 μl of the labeled solution of NCPs at 0.1 mg/ml was mixed with 150 μl of the unlabeled network. To ensure the homogeneity of the solution, experiments were performed a few hours after the mixing of the solution. However to avoid any exchange of the dye between the unlabeled network and the labeled objects, mixing time never exceeded 5–6 h.

FCS experiments

FCS experiments were performed using a commercial FCS setup (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany), consisting of the module Confocor 2 and the microscope model Axiovert 200 equipped with a Zeiss C-Apochromat 40×, NA 1.2 water immersion objective. The illumination sources were an Ar laser (514 nm) for excitation of the Toto-1 dye or an He-Ne laser (633 nm) for Toto-3. Emitted fluorescence was collected at wavelengths exceeding 530 nm for Toto-1 and 650 nm for Toto-3.

Determination of the laser waist size was performed by comparison between the theoretical and experimental diffusion of 30 bp DNA labeled with either Toto-1 or Toto-3 depending on the laser used. Theoretical diffusion of rods with length L and diameter d, is known to be  where γ = 0.312 + 0.565d/L − 0.1(d/L)2 (Tirado et al., 1984), η is the solvent viscosity, kB the Boltzmann constant, and T the temperature. The calibration with short double-strand DNA has the advantage that the same dye is used as in our final experiments.

where γ = 0.312 + 0.565d/L − 0.1(d/L)2 (Tirado et al., 1984), η is the solvent viscosity, kB the Boltzmann constant, and T the temperature. The calibration with short double-strand DNA has the advantage that the same dye is used as in our final experiments.

Theory and data analysis

Since FCS is well established (Magde et al., 1972; Elson and Madge, 1974) and has been discussed in detail elsewhere (Eigen and Rigler, 1994; Schwille et al., 1997), we will only give a short introduction. The raw signal in a FCS experiment is the time-dependent fluorescence intensity, F(t), emitted by fluorescently labeled objects diffusing through a small open volume (<1 fl). The size of the effective volume depends both on the excitation profile of the focused laser beam and the confocal detection optics. Fluctuations, δF(t), in the measured intensity signal are due to molecules entering or leaving the detection volume and are, therefore, related to diffusion.

By means of a time autocorrelation, dynamic information contained in the intensity fluctuations can be realized. For an ideal Brownian diffusing particle, the resulting autocorrelation function is given by

|

(1) |

with

|

(2) |

In Eq. 2, f is the ratio of the height z0 and the radius r0 of the detection volume, usually approximated by a Gaussian ellipsoid and N denotes the number of particles per effective volume. The mean passage time τD of a particle through a detection volume of radius r0 directly relates to the diffusion coefficient Dt as:

|

(3) |

In the case of globular diffusion objects, the hydrodynamic radius, RH, can be written as:

|

(4) |

For experiments performed with an intercalating dye in the DNA, the experimental autocorrelation function is not simply fitted by Eq. 1. We observed that the intercalating dyes exhibit not only the well known triplet decay on very short timescales (Widengren et al., 1995), but also a decay in the intermediate time range between triplet and diffusional decay (Lumma et al., 2003). This intermediate decay was modeled as an isomerization between two states, on and off, similar to chromophore blinking known from GFP (Wachsmuth et al., 2000). Assuming that these processes are well separated in the time domain, the autocorrelation function can be written (Widengren, 2001).

|

(5) |

where  is the autocorrelation function related with the characteristic triplet decay τT of fraction T. χ denotes the on-off kinetics of the intercalated dyes, with a transfer rate from excited to unexcited states koff, and kon for the reverse process.

is the autocorrelation function related with the characteristic triplet decay τT of fraction T. χ denotes the on-off kinetics of the intercalated dyes, with a transfer rate from excited to unexcited states koff, and kon for the reverse process.

For diffusion in a network where the particles no longer move freely, an anomalous diffusion is observed due to the presence of barriers and particle-network interactions. In this case, the mean-square displacement of the particles 〈x2〉, is no longer proportional to the time, but scales as  where β is the anomalous diffusion parameter (Saxton, 1994), also called stretched exponent.

where β is the anomalous diffusion parameter (Saxton, 1994), also called stretched exponent.

The autocorrelation function of anomalous diffusion of the particle is a generalization of Eq. 1 and can then be written as:

|

(6) |

If the anomalous parameter β = 1, Eqs. 2 and 6 become identical, and one recovers the normal free diffusion.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Freely diffusing nucleosome core particles

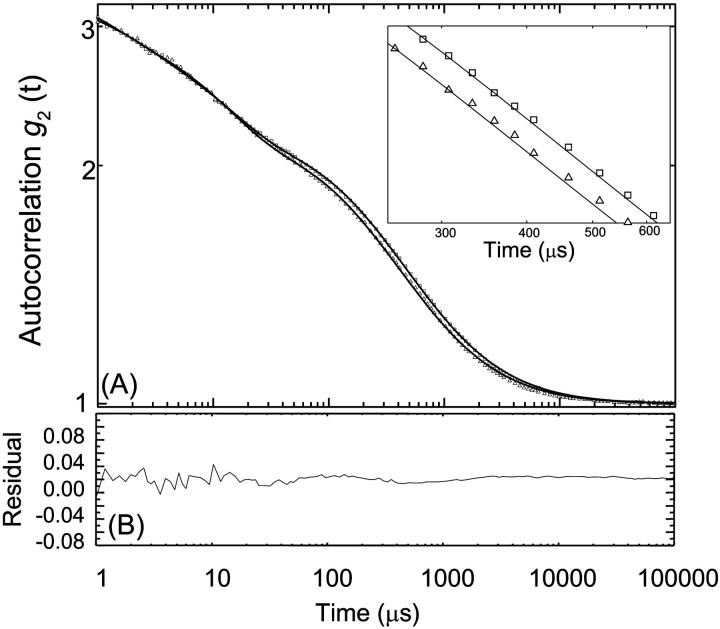

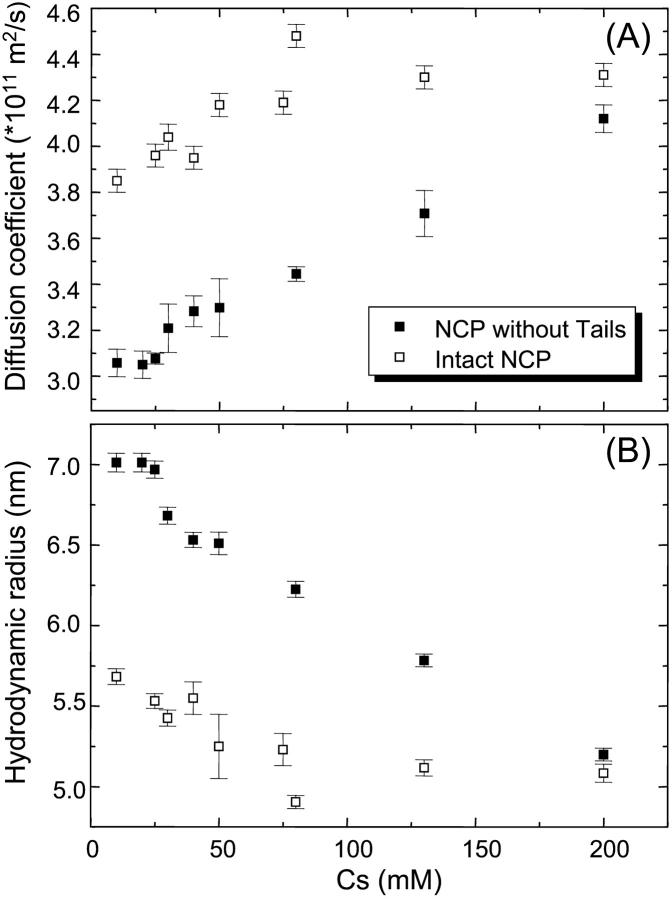

FCS measurements were performed on intact nucleosome core particles in different ionic buffers ranging from 10 to 200 mM monovalent salt concentration, Cs. Fig. 2 A shows the autocorrelation function (normalized by the number of particles, N, in the laser beam), for particles labeled with Toto-3, at a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml for Cs = 10 and 200 mM. These functions were fitted using Eqs. 2 and 5. The residues between experimental data and best fit are plotted in Fig. 2 B. The experimental data and the fits are in good agreement for the entire set of data, showing that Eq. 5 describes the data appropriately. The fitting parameters related with the on/off kinetics of the chromophore and the triplet states were found to be nearly independent of the salt concentration. The triplet fraction was around 30% with a triplet time of 0.9 μs. The transfer rate, koff−1, of the blinking process was 15 μs, with a ratio K = kon/koff = 3. The variations of the diffusion coefficient Dt are plotted in Fig. 3 A. Interestingly, the diffusion shows variations as a function of the salt concentration. Dt is found to increases from 3.8 × 10−11 to 4.7 × 10−11 m2/s when the salt concentration increases from 10 to 75 mM, and then remains constant at higher salt concentrations. Assuming a globular shape for NCPs, the apparent hydrodynamic RHapp values can be calculated according to Eq. 4. As shown in Fig. 3 B these variations are related with a decrease in the hydrodynamic radius from 5.7 nm to 5.1 nm. The same experiments were performed on NCPs where histone tails were digested by trypsin. Variation of the diffusion coefficient and hydrodynamic radius are also plotted on Fig. 3, A and B. As for intact NCPs, the diffusion coefficient increases when increasing Cs, but with different variations. It was found to increase linearly from 3 × 10−11 to 4.1 × 10−11 m2/s. This corresponds to a decrease of Rhapp from 7 to 5.2 nm. No plateau value was found for trypsinized NCPs.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Experimental autocorrelation functions, g2(t) recorded for intact NCPs for two different salt concentrations: Cs = 10 mM (up triangle) and 200 mM (open square). The functions, normalized by the number of particles, N, inside the effective laser volume are fitted according to Eqs. 2 and 5 (continuous lines). Inset zoom of the g2(t) function for time ranging from 200 to 600 ms (B) Residual between the fit and experimental functions for Cs = 10 mM.

FIGURE 3.

(A) Variation of the diffusion coefficient and (B) the hydrodynamic radius as a function of the salt concentration, Cs, for intact and trypsinized NCPs. Both kind of particles are labeled with Toto-3, with in average one particle over ten labeled with one dye. Experiments were performed at a NCP concentration CNCP = 0.1 mg/ml.

Comparison between radius of gyration and hydrodynamic radius

In a previous study small-angle x-ray scattering was performed on intact NCPs in a similar range of salt concentrations. With increasing salt a small increase in the radius of gyration from 4.3 to 4.6 nm was measured. This increase was attributed to the unfolding of the histones tails outside of the core (Mangenot et al., 2002a). We would like to consolidate the static and dynamic measurements. Assuming rigid globular particles we introduce as an approximate relation between the hydrodynamic radius (RH) and the radius of gyration (RG):

|

(7) |

where δRS denotes a correction due to the thickness of the solvation shell and δRκ a correction due to the relaxation effect of the counterions surrounding the particles (Oosawa, 1971). Both effects contribute to the effective hydrodynamic radius but remain almost invisible in the radius of gyration. The thickness of the hydration shell is expected to be nearly constant over the whole range of salt concentrations and one could reasonably assume that δRS will be on the order of a few angstroms. In this case, if we neglect the effect of the counterions on the NCPs diffusion, increasing the salt concentration should give rise to an increase of the hydrodynamic radius. Surprisingly, neither the intact, nor the trypsinized NCPs, show an increase of the hydrodynamic radius when the salt concentration is increased.

Self-diffusion of particles as a function of the salt concentration has been studied for different colloidal systems, such as proteins (Weissman et al., 1979; Le Bon et al., 1999), DNA (Fulmer et al., 1981), micelles, charged latex spheres (Gorti et al., 1984), synthetic polyelectrolytes (Mattoussi and Karasz, 1990). Depending on the system, both an increase and a decrease of the hydrodynamic radius was observed with increasing salt concentration. One possible reason is the presence of interparticle interactions in the solutions which are known to increase the value of the hydrodynamic radius (O'Leary, 1987; Mattoussi and Karasz, 1990). Our experiments were performed at very dilute concentrations. The hydrodynamic radius could then be analyzed without taking into account an effect of interparticle interaction, but only conformation.

We observe no dependence of the diffusion over NCP concentrations (CNCP) ranging from 0.05 to 0.5 mg/ml. Technically, one can perform experiments at lower NCP concentration, but this region is at the limit of the onset of unwrapping between DNA and histones core.

An increase of the diffusion coefficient with increasing salt concentration has been observed experimentally on polyelectrolytes solutions (Mattoussi and Karasz, 1990), and charged latex spheres (Gorti et al., 1984). In both cases the authors argue that these variations are due to the presence of counterions surrounding the particle, and lead to what is referred to as the “relaxation effect” in the polyelectrolyte theory (Oosawa, 1971).

Relaxation effect of counterions

In this paragraph we would like to briefly discuss the relaxation effect in more detail. As already mentioned, the diffusion of the particle leads to a deformation of the counterion layers, known as the relaxation effect. This deformation is important at low salt, when the counterion layer (proportional to the Debye-screening length κ−1) is more important. A theory exists to quantify this effect of the diffusion coefficient of weak charged particles, i.e., when the zeta potential of the particle is small: ζ < kBT/e (ζ < 25 mV) (Schurr, 1980). In case of noninteracting particles, considered as spheres of radius a and effective charge Zeff, the additional effective hydrodynamic layer δRκ, due to the relaxation effect of counterions is given by:

|

(8) |

where e is the elementary charge, ɛ0 the vacuum permittivity, ɛ the dielectric constant of the solution, and Ds the diffusion coefficient of the small ions. According to this theory, increasing the salt concentration should decrease the value of the hydrodynamic radius. In case of the intact NCPs, the effective charge of the particle has already been studied as a function of the salt concentration (Mangenot et al., 2002b). Zeff was found to decrease from −71 to −124 when the salt concentration was varied from 7.5 to 210 mM. According to these values, the qualitative variations of the hydrodynamic radius could be reproduced without any free parameter. However, the theoretical values are found to be too low compared to the experimental results by a factor of two. This is probably due to the fact that intact NCPs are not weakly charged polyelectrolytes. The absolute values of the zeta potential were measured over a range from 92 to 28 mV as the salt concentration was varied from 7.5 to 210 mM.

Trypsinized NCPs

Since much of the ambiguity of the hydrodynamic data stems from the unfolding histone tails, it is of interest to consider the case where these tails are cut off by enzymatic digestion. The effective charge of the trypsinized NCPs is larger than for intact NCPs leading to different values of the hydrodynamic radius. The intact NCPs are highly negatively charged with a structural charge of −146: the 146 bp DNA carry 292 negative charges (two negative charges per bp), and the histone octamer contains 220 positives charges (lysine and arginine) and 74 negatives charges (acids aspartic and glutamic). All the negative charges of the histone octamer are located on the histone core, but approximately half of the positive charges are located on the histones tails. Therefore, the structural charge of the trypsinized NCP is approximately −246. In first approximation for our experiments, intact and trypisnized NCPs were considered as spheres, with a radius of 5 nm, and with two different structural charges. At low salt, Cs = 10 mM, a difference of 1.5 nm was observed in the values of the hydrodynamic radius. This can be associated with the counterion layer, which is proportional to the Debye-screening length κ−1, and therefore more important in the case of more negatively charged particles. On the contrary, at high salt, the thickness of this layer is expected to be very small (κ−1 = 0.67 nm for Cs = 200 mM), and thus quasi independent of the charge of the particles. This effect is observed experimentally, at Cs = 200 mM, where RH ≈ 5 nm for both intact and trypsinized NCPs, and in keeping with the radius of the particle without counterions.

In summary, the relaxation effect of the counterions surrounding the particles leads to a decrease of the hydrodynamic radius (Schurr's theory) whereas the conformational changes of the NCP gives rise to an increase of RH when the salt concentration is increased. Both effects are involved in our experiments for intact NCPs. The situation is then simple for trypsinized NCPs. In this case, the radius of gyration is found to be nearly constant for salt concentration higher than 20 mM (Bertin A., Leforestier A., Durand D. and Livolant F., in preparation). The variation of the hydrodynamic radius is then only due to the relaxation effect of the counterions surrounding the particles.

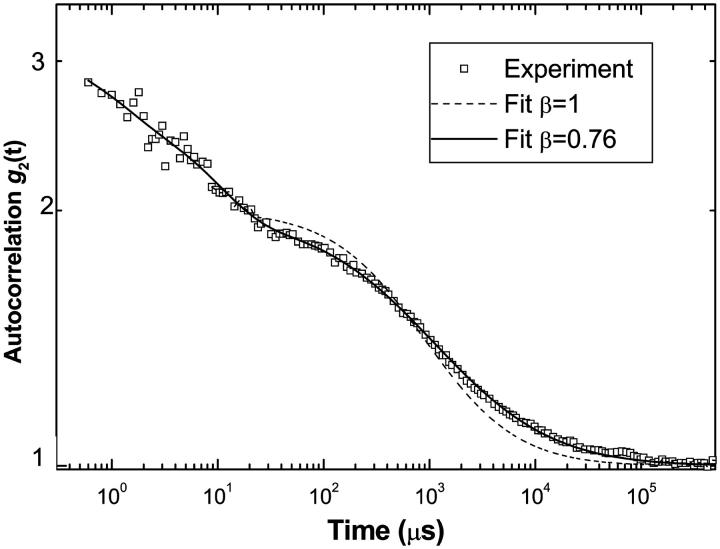

Diffusion of nucleosome core particles in concentrated DNA solutions

In the following, we consider nuclear core particles placed in concentrated DNA solutions of purified calf thymus DNA (typically 30–50 kbp). The NCPs were fluorescently labeled with Toto-3, whereas calf thymus DNA was unlabeled. The NCP diffusion was studied as a function of the DNA concentration (CDNA) ranging from 0.25 to 100 mg/ml and for three different salt concentrations (Cs = 10, 100 and 400 mM). The FCS autocorrelation functions were recorded over 10 to 30 min, and analyzed using Eqs. 5 and 6. For freely diffusing NCPs, the fit to the anomalous diffusion equation was found to yield values for the stretched exponent β close to 1, independent of salt concentration. In contrast the fluorescence correlation signal of NCPs in concentrated DNA solutions can not be fitted by a normal diffusion behavior. Fig. 4 shows the quality of the fits for β = 1 fixed and β optimized. The parameters related with the triplet state and the chromophore blinking were found to be the same as for free diffusion of the particles and nearly independent of the salt and DNA concentrations. The two important parameters to be discussed are thus the anomalous diffusion parameter β and the diffusion time τD.

FIGURE 4.

Autocorrelation function recorded for Cs = 10 mM, in a DNA concentrated solution of 5 mg/ml. The particles were labeled with Toto3, with in average one over ten particles labeled with one dye. The experiments were performed at very low NCP concentration: CNCP = 0.05 mg/ml. The curve is fitted according to the Eqs. 5 and 6 when the anomalous parameter β is fixed to 1 (dashed line) and optimized to 0.76 (continuous line).

Diffusion of intact NCPs

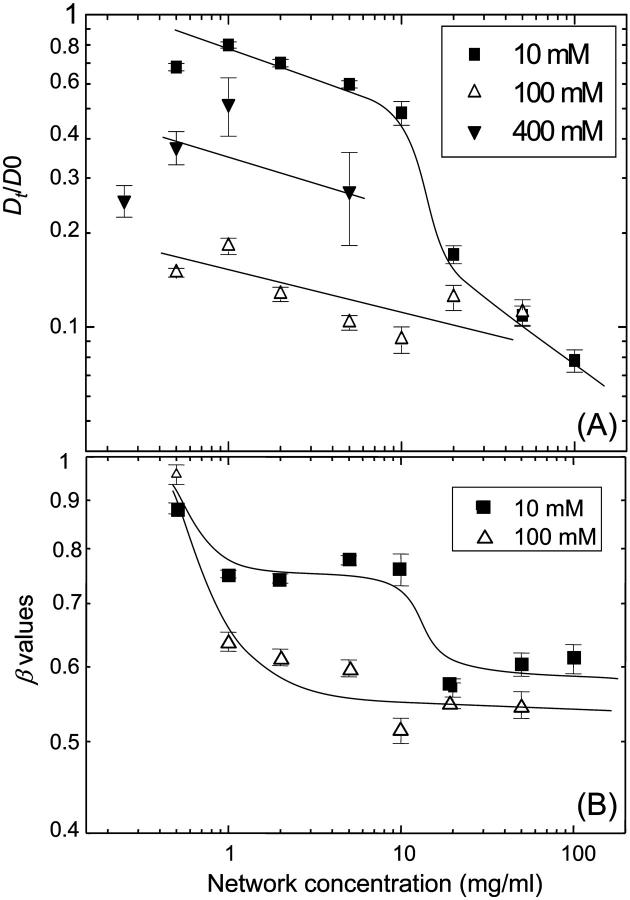

Fig. 5 A shows the diffusion coefficient (Dt) normalized by the free diffusion coefficient of NCPs (D0) recorded for freely diffusing NCPs in the absence of DNA solution. The normalized diffusion coefficient is found to decrease continuously with increasing DNA network concentration. The data set recorded at low salt concentration, Cs = 10 mM, shows a weak decay for low DNA concentrations, and a discontinuity in the slope at about a crossover concentration, Ccross ≈ 15 mg/ml. This discontinuity is missing in the data recorded at higher salt concentration, Cs = 100 mM, which show an average weak decay over the whole range of DNA concentrations. Moreover the data at high salt do not seem to asymptotically approach unity for decreasing DNA concentration. It is important to note that all the values of the NCPs diffusion are at least 100 times faster than the self-diffusion of calf thymus DNA molecules within the DNA network.

FIGURE 5.

(A) Variation of the diffusion coefficient of intact NCPs as a function of the DNA concentration, normalized by D0, the diffusion coefficient of free NCPs. The data are recorded for three salt concentrations: Cs = 10, 100, and 400 mM. (B) Variation of the anomalous parameter β resulting from the fit of the autocorrelation function by using Eqs. 5 and 6. The lines are just guides for the eyes.

The diffusion of particles in a polymer solution has been investigated on numerous polymeric systems. A general experimental finding is that for particles with radius smaller than the mesh size of the polymer solution, RH < ξ, the particles see the linear viscosity (ηp) of the polymer solution (Ye et al., 1998; Busch et al., 2000)

|

(9) |

where η0 denotes the solvent viscosity and [η] the intrinsic viscosity of the polymer in solution of concentration Cp. Hence using Stokes-Einstein and Eq. 9 the measured normalized self diffusion coefficient of NCPs in DNA should follow:

|

(10) |

We fitted the first part of the diffusion data shown in Fig. 5 A using the linear Eq. 10. For low salt concentration we yield good agreement with [η] = 0.0438 ± 0.006 ml/mg and an offset close to 1. This intrinsic viscosity is also in agreement with measurements in the Bloomfield group (Busch et al., 2000). However, the data at Cs = 100 mM are not well described by the Eq. 10. The reason is that the asymptotic limit at low DNA concentration is clearly not approaching unity. Furthermore, discontinuity at the crossover concentration, Ccross, seen in the data for Cs = 10 mM are also not explained by this first approach. We will argue in the following that both effects are due to unfolding of the histone side chains, which induce a strong histone-DNA interaction. Previous studies on the second virial coefficient of dilute NCP solutions have shown that the histone tails unfold when the ionic strength of the solution was increased. The unfolded cationic tails give rise to an attractive force between neighboring NCPs by a mechanism called “tail bridging” (Mangenot et al., 2002b). For this new situation of histone-DNA binding, we adopt theory made for transport of proteins on actin filaments (Ajdari, 1995; Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2002). Particles that are able to absorb reversibly to a filament network diffuse more slowly than free particles due to the dwell time, when adsorbed. Neglecting active transport on filaments, the resulting apparent diffusion coefficient (Dsticky) could then be written:

|

(11) |

Dt represents the diffusion coefficient of particles which diffuse during the time τoff when they are not adsorbed to the network, and stay during the time τon on the network. Using this equation and replacing Dt as described by Eq. 11 we obtain good agreement with the data at high salt. Dt is found to decrease by a factor of 5.2 in comparison with the free diffusion. Moreover, we recover the same intrinsic viscosity [η] = 0.0439 ± 0.008 ml/mg.

The question remains, how the discontinuity at Ccross occurs. One has to consider that at high DNA concentrations, the ionic strength (Cc) due to the counterions of DNA cannot be neglected. This counterion concentration is equal to the phosphate concentration of the DNA, but due to Manning's condensation, only a fraction of these counterions contribute to the ionic strength of the solution. According to Manning's theory for condensation, this fraction is equal to 25%. The total ionic strength of the solution is then equal to Cs + Cc. For low DNA concentrations (e.g. for 1 mg/ml, Cc = 3 mM), the counterions contribution can be neglected compared to the added salt. Under this condition, for Cs = 10 mM, the histone tails of the NCPs are folded onto the particle and do not interact with the network. For high network concentration, the counterions increase the effective salt concentration (CDNA = 20 mg/ml, and for Cs = 10 mM, the ionic strength of the solution is then equal to 25 mM). At concentrations above 20 mM, the histone tails of NCPs unfold. This explains why the diffusion coefficient of the 10 mM data approaches the same value as the 100 mM data since the NCP conformation is the same in both experiments. Finally, for Cs = 400 mM, the histone tails are still unfolded, but the attractive interactions between the positively charged tails and negatively charged DNA are partially screened, leading to an increase of the diffusion coefficient, compared to the one recorded for Cs = 100 mM.

We finally address the question, if steric effects might determine diffusion in the highly concentrated limit. All the measurements presented in this study are performed in the semidilute regime. The transition from the dilute to the semidilute regime occurs at a concentration C* = 0.01 mg/ml. We checked using x ray that all the solutions, up to CDNA = 100 mg/ml were still isotropic (data not shown). In this regime, the properties of the DNA concentrated solutions do not depend on the length of the DNA. It is thus possible to estimate the mesh size ξ between two entanglements in the DNA solution according to the data of Wang and Bloomfield, who measured the variation of ξ as a function of CDNA for a solution of 146 bp DNA (Wang and Bloomfield, 1991). According to these authors, ξ is found to vary from 50 nm at 1 mg/ml to 6 nm at 100 mg/ml. Interestingly, for the higher network concentration studied, the mesh size of the concentrated DNA solution is approximately equal to the size of the NCPs. Nevertheless, the diffusion of the NCPs is found to be only 5–10 times lower than the free diffusion of NCPs in the absence of DNA.

The stretched exponential of anomalous diffusion

The anomalous diffusion parameter β is plotted on Fig. 5 B for Cs = 10 and 100 mM as a function of the network concentration. The stretched exponent β is found to be equal to 1 for free diffusion and decreases in the case of high salt (Cs = 100 mM) conditions to almost 0.55 at high DNA concentration. At low salt (Cs = 10 mM), the exponent drops to ∼0.75 up to the crossover concentration Ccross = 15 mg/ml, where it suddenly approach 0.55 as for the high salt concentration. Anomalous diffusion has been widely studied in the percolation field (Stauffer and Aharony, 1992). These theoretical studies are restricted to obstacle concentration near the percolation threshold and thus can not be directly used in our study where the DNA network concentration varies over a wide concentration range. Therefore, it is worthwhile to compare these data with Monte Carlo studies which analyzed the diffusion of a molecule in the presence of inert obstacles or binding sites (Saxton, 1994, 1996). Interestingly, this simulation predicted that increasing the network concentration will decrease the β values more drastically in the case of binding than in the case of noninteraction between the particles and the network, up to a plateau value of 0.3. Our measurements show that the β values are higher at Cs = 10 mM than at Cs = 100 mM. Moreover, both set of data asymptotically approach a value of 0.55. The difference between the theoretical and experimental values could be due to the fact that simulations are made for a point like network. The only discrepancy lays in the fact that in the absence of interaction between the network and the particle, Monte Carlo simulation predicted that increasing the network concentration should decrease the value of the stretched exponent. Interestingly, except for the discontinuity observed at Ccross, which we mention once again is attributed to binding of NCP with the DNA, increasing the DNA concentration does not change the β value for Cs = 10 mM. Increasing the network concentration decreases the value of the diffusion coefficient but does not influence the anomalous diffusion of the NCPs in a concentrated DNA solution. Finally, it seems important to note that the autocorrelation functions were measured without problem for Cs = 10 and 100 mM, on the whole range of network concentration. The fluorescent dyes were found to be highly intercalated in the DNA of the NCPs. On the contrary, no measurements were possible for Cs = 400 mM, when the network concentration was >5 mg/ml. Indeed, at high salt concentration we observed that binding between intercalating dye and DNA became weaker due to screening of interactions. Therefore, for lower network concentrations, some measurements were performed but the errors bars on the diffusion coefficients are more important than for lower salt concentrations. It was also nearly impossible to determine the anomalous parameter β for these curves.

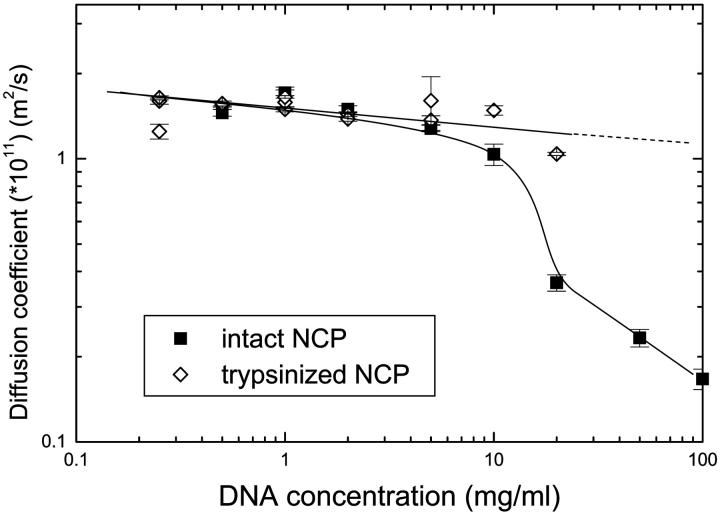

Trypsinized NCP

The diffusion coefficient of trypsinized NCPs has been studied in the same conditions than for intact NCPs, for Cs = 10 and 100 mM. Its variations are plotted on Fig. 6. Interestingly, the diffusion coefficient is found to be independent of the salt concentration on the whole range of network concentration studied. More over, the values of the diffusion coefficient are equal to a constant value of 1.5 × 10−11 m2/s, when CDNA is ranging from 0.25 to 20 mg/ml. Independently of the network and salt concentration, the absence of the histone tails for the trypsinized NCPs prevent the interaction between the NCPs and the network. The NCP diffusion is then mainly governed by the crowding of the DNA solution, and the repulsion between the NCPs and the network. In such case, some authors argue that increasing the DNA concentration will push onto the particles which then will be faster. This effect is not observed in our experiments, probably due to the mesh size which even at high network concentration is largely bigger than the NCP size.

FIGURE 6.

Diffusion coefficient recorded for trypsinized NCPs, as a function of the DNA concentration and for two different salt concentrations: Cs = 10 and 100 mM. By comparison, the diffusion coefficient measured for intact NCPS for Cs = 10 mM, is also plotted.

CONCLUSION

The diffusion of isolated nucleosome core particles has been studied for intact and trypsinized particles. They are analyzed either in free solution as a function of the salt concentration or in a DNA solution, as a function of the salt and DNA concentration. In aqueous solution, the NCPs follow Brownian diffusion behavior with a weak salt dependence. Increasing the salt concentration leads to an increase in the diffusion coefficient, related to a decrease of the hydrodynamic radius. We have shown that this variation are understood when taking into account both the conformational changes of the NCPs, i.e., histones tails unfolding when the ionic strength of the solution is increased, and also the relaxation effect of the counterions surrounding the particles. In the second part of this article, we studied the diffusion of the same particles in a DNA network. We demonstrated that the diffusion coefficient of NCPs is mainly governed by the conformation of the histones tails. When these cationic chains are folded onto the particles, the measured diffusion coefficient is understood by taking into account a simple model of diffusion in an entangled DNA solution. On the contrary, when the tails are entangled out of the core, we have to take into account an electrostatic binding between the particles and the DNA to understand our data. Moreover, we demonstrated that the diffusion of trypsinized NCPs, which lack the basic tails, is governed by the crowding of the DNA solution and nearly independent of the salt concentration.

Our study intended to mimic some aspects of the chromatin dynamics inside the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. We saw that much of the diffusion behavior in vitro is understood by treating the nucleosome core particles like charged colloids. However, the most dramatic changes in the diffusion coefficient were associated with the unfolding of the histone tails. In fact, trypsinized NCPs missed the histone tail related effects. Moreover the unfolding occurred in a physiological regime of salt concentration. Hence we could assume that conformational changes associated with histone tails will play an important part in controlling chromatin dynamics. Mobility of chromatin fibers with respect to each other could be switched by histone tail bridges. It will be highly illuminating for the future to investigate for example NCP diffusion in vivo. In particular since in vivo measurements of DNA diffusion inside the cell nucleus seem to demonstrate that small DNA fragments are almost immobile over characteristic distances of 1 μm and over a few minutes timescale (Lukacs et al., 2000). The situation could be different for NCP particles, since we found measurable diffusion even at the highest DNA concentrations. FCS proved to be very powerful technique in this respect, since it makes use of specifically labeling the NCP in a dense macromolecular network. The technique also permits to measure histone-DNA binding directly as well as allows for future intracellular studies on living cells.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge A. Bertin and Dr. Livolant's group for the kind gift of the trypsinized nucleosome core particles.

This project was partly supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft by grant SFB-563-A4.

References

- Ajdari, A. 1995. Transport by active filaments. Europhys. Lett. 31:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ausio, J., and K. V. Van Holdes. 1989. Use of selectively trypsinized nucleosome core particles to analyse the role of histone tails in the stabilisation of the nucleosome. J. Mol. Biol. 206:451–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch, N. A., T. Kim, and V. A. Bloomfield. 2000. Tracer diffusion of proteins in DNA solutions. 2 Green fluorescent protein in crowded solutions. Macromolecules. 33:5932–5937. [Google Scholar]

- Eigen, M., and R. Rigler. 1994. Sorting single molecules: application to diagnostics and evolutionary biotechnology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:5740–5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson, E., and D. Madge. 1974. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy- I. Conceptual basis and theory. Biopolymers. 13:1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer, A. W., J. A. Benbasat, and V. A. Bloomfield. 1981. Ionic strength effect on macroion diffusion and excess light scattering of short DNA rods. Biopolymers. 20:1147–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ramirez, M., F. Dong, and J. Ausio. 1992. Role of the histone tails in the folding of oligonucleosomes depleted of histone H1. J. Biol. Chem. 267:19587–19595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorti, S., L. Plank, and B. R. Ware. 1984. Determination of electrolyte friction from measurement of the tracer diffusion coefficients, mutual diffusion coefficients, and electrophoretic mobilities of charged spheres. J. Chem. Phys. 81:909–914. [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg, R. D., and Y. Lorch. 1999. Twenty-five years of the nucleosome, Fundamental particle of the eukaryote chromosome. Cell. 98:285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bon, C., T. Nicolai, M. E. Kuil, and J. G. Hollander. 1999. Self-diffusion and cooperative diffusion of globular proteins in solution. J. Phys. Chem B. 103:10294–10299. [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs, G. L., P. Haggie, O. Seksek, D. Lechardeur, N. Freedman, and A. S. Verkman. 2000. Size dependent DNA mobility in cytoplasm and nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1625–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumma, D., S. Keller, T. Vilgis, and J. O. Rädler. 2003. Dynamics of large semiflexible chains probed by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90:218301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magde, D., E. Elson, and W. W. Webb. 1972. Thermodynamic fluctuations in a reacting system-measurement by fluorescent correlation spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 29:705–708. [Google Scholar]

- Mangenot, S., A. Leforestier, P. Vachette, D. Durand, and F. Livolant. 2002a. Salt-induced conformation and interaction changes of nucleosome core particles. Biophys. J. 82:345–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangenot, S., E. Raspaud, C. Tribet, L. Belloni, and F. Livolant. 2002b. Interactions between isolated nucleosome core particles: A tail bridging effects? Eur. Phys. J. E. 7:221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Mattoussi, H., and F. E. Karasz. 1990. Electrostatic and screening effects on the dynamics aspects of polyelectrolytes solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 93:3593–3603. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, R. 1989. Nucleosomes inhibit both transcriptional initiation and elongation by RNA polymerase III in vitro. EMBO J. 8:2343–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuizen, T. M., S. Klumpp, and R. Lipowski. 2002. Walks of molecular motors in two and three dimensions. Europhys. Lett. 58:468–474. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary, T. 1987. Concentration dependence of protein diffusion. Biophys. J. 52:137–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosawa, F. 1971. Polyelectrolytes. Marcel Dekker, New York.

- Peterson, C. L. 2000. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling: going mobile. FEBS Lett. 476:68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, M. 1994. Anomalous diffusion due to obstacles: a Monte Carlo study. Biophys. J. 66:394–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, M. 1996. Anomalous diffusion due to binding: a Monte Carlo study. Biophys. J. 70:1250–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurr, J. M. 1980. A theory of electrolyte friction on translating polyelectrolytes. Chem. Phys. 45:119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Schwille, P., F. Meyer-Almes, and R. Rigler. 1997. Dual-color fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy for multicomponent diffusional analysis in solution. Biophys. J. 72:1878–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer, D., and A. Aharony. 1992. Introduction to Percolation Theory. Taylor and Francis, London.

- Tirado, M. M., C. L. Martinez, and J. G. de la Torre. 1984. Comparison of theories for translational and rotational diffusion coefficients of rod-like macromolecules. Application to short DNA fragments. J. Chem. Phys. 81:2047–2052. [Google Scholar]

- Varga-Weisz, P. D., and P. B. Becker. 1998. Chromatin-remodeling factors: machines that regulate? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10:346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmuth, M., W. Waldeck, and J. Langowski. 2000. Anomalous diffusion of fluorescent probes inside living cell nuclei investigated by spatially-resolved fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 298:677–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L., and V. A. Bloomfield. 1991. Small-angle x-ray scattering of semidilute rodlike DNA solutions: polyelectrolyte behavior. Macromolecules. 24:5791–5795. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman, M. B., R. C. Pan, and B. R. Ware. 1979. Electrostatic contributions to the viscosities and diffusion coefficients of macroion solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 70:2897–2903. [Google Scholar]

- Widengren, J. 2001. Photophysical aspects of FCS measurements. In Fluorecence Correlation Spectroscopy, Theory, and Applications. R. Rigler and E. Elson, editors. Springer. 276–301, Berlin.

- Widengren, J., U. Mets, and R. Rigler. 1995. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy of triplet-states in solution - a theoretical and experimental-study. J. Phys. Chem. 99:13368–13379. [Google Scholar]

- Widom, J. 1998. Structure, dynamics, and function of chromatin in vitro. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 27:285–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X., P. Tong, and L. J. Fetters. 1998. Transport of probe particles in semidilute polymer solutions. Macromolecules. 31:5785–5793. [Google Scholar]