Abstract

Characterization of rhodamine 123 as functional assay for MDR has been primarily focused on P-glycoprotein-mediated MDR. Several studies have suggested that Rh123 is also a substrate for MRP1. However, no quantitative studies of the MRP1-mediated efflux of rhodamines have, up to now, been performed. Measurement of the kinetic characteristics of substrate transport is a powerful approach to enhancing our understanding of their function and mechanism. In the present study, we have used a continuous fluorescence assay with four rhodamine dyes (rhodamine 6G, tetramethylrosamine, tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester, and tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester) to quantify drug transport by MRP1 in living GLC4/ADR cells. The formation of a substrate concentration gradient was observed. MRP1-mediated transport of rhodamine was glutathione-dependent. The kinetics parameter, ka = VM/km, was very similar for the four rhodamine analogs but ∼10-fold less than the values of the same parameter determined previously for the MRP1-mediated efflux of anthracycline. The findings presented here are the first to show quantitative information about the kinetics parameters for MRP1-mediated efflux of rhodamine dyes.

INTRODUCTION

A major obstacle impeding the success of chemotherapy is multidrug resistance (MDR). The classical MDR phenotype is characterized by cross-resistance to a wide variety of structurally unrelated chemotherapeutic agents of natural origin after being exposed to only one. The role of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and the multidrug resistance protein (MRP1) in MDR, in vitro, are uncontested (Cole and Deeley, 1998; Nielsen and Skovsgaard, 1992). Both proteins are members of the ATP-Binding-Cassette superfamily of transport proteins that lower the intracellular drug content through active drug efflux. Transfection experiments with the mdr-1 gene (Fojo et al., 1987) or the mrp-gene (Grant et al., 1994) have demonstrated that overexpression of these genes was sufficient to render otherwise drug-sensitive cells multidrug resistant.

Characterization of drug retention as functional assays for MDR has been primarily focused on P-gp-mediated MDR, and the recognition that Rh 123 is substrate for P-gp that can be applied at noncytotoxic concentrations has stimulated the use of this agent in flow cytometric drug retention studies. After the discovery of MRP1 in 1996, studies were undertaken to determine if agents used to evaluate P-gp function also can be used to evaluate MRP function. Thus, cellular retention of rhodamine 123 was studied in MRP1-expressing cell lines. Several studies have suggested that Rh123 is a substrate for MRP1 (Zaman et al., 1994; Twentyman et al., 1994; Minderman et al., 1996); however, no quantitative studies of the MRP1-mediated efflux of rhodamine have, up to now, been performed.

In this article, using two types of measurements, rate and steady-state, with the latter being performed under single-cell conditions, we have derived values for the internal concentration of free rhodamine, and hence values for the real rate of outward pumping of rhodamine. In addition, the use of potassium and a potassium carrier to eliminate the effect of membrane potential makes a very useful simplification. This was done using intact GLC4/ADR cells. We are therefore able to present data that quantitatively characterized the transport by MRP1 of four rhodamine analogs: rhodamine 6G (Rh 6G), tetramethylrosamine (TMR), tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester or rhodamine I (Rh I), and tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester or rhodamine II (Rh II). The results are compared with those obtained in the same cell line with other substrates versus those obtained in cells having a P-gp-mediated MDR phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drugs and chemicals

Rhodamine 6G (Rh 6G) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Tetramethylrosamine (TMR), tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester or rhodamine I (Rh I), and tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester or rhodamine II (Rh II) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Stock solution of rhodamine, 10−3M, were prepared in ethanol. Purified daunorubicin (DNR) was kindly provided by Pharmacia-Upjohn Laboratories (Milano, Italy). Triton X-100, valinomycin, FCCP, L-buthionine-(s,r) sulphoximine (BSO), and concanamycin A were from Sigma. Valinomycin and FCCP were dissolved in ethanol. All the reagents were of the highest quality available and deionized double-distilled water was used throughout the experiments. Some experiments were performed in HEPES/Na+ buffer solutions containing 20 mM HEPES plus 132 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 0.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose at pH 7.3. However, most of the experiments were performed in HEPES/K+ buffer solution: to dissipate membrane potential, high K+, low Cl− buffer was made by equimolar substitution of K-methanesulfonate for NaCl, 10 nM valinomycin, and 1 μM FCCP was added. We have checked that at these concentrations neither valinomycin nor FCCP inhibits the MRP1-mediated efflux of drug. K-methanesulfonate was made by titration of methanesulfonic acid with KOH before addition to buffer (Piwnica-Worms et al., 1983).

Cell lines and cultures

GLC4 and the MRP1-expressing GLC4/ADR cells (Zijlstra et al., 1987) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The resistant GLC4/ADR cells were cultured with 1.2 μM doxorubicin until 1–4 weeks before experiments. Cell cultures used for experiments were split 1:2 one day before use to ensure logarithmic growth. Cell viability was assessed by Trypan blue exclusion and was >95% under the various experimental conditions used. Cell counting and cell diameter were determined using a Coulter Channelyzer 256 (Beckman, St. Louis, MO). The curve distribution of the cell number vs. cell radius had a Gaussian shape with a maximum corresponding to mean cell radius of 12.5 μm and 75% of the cells had a radius equal to 12.5 ± 1.5 μm, which yields a mean volume 1.0 ± 0.3 × 10−12 L. The cytotoxicity of one rhodamine derivative, RhII, was determined by incubating cells (105) with different concentrations of the compound for 72 h in standard 6-well plates. Three independent experiments were performed. Then the IC50 values (50% inhibitory drug concentrations) were determined by counting the cells using a Coulter counter. The resistance factor (RF) was defined as the IC50 for the resistant cells divided by the IC50 for the corresponding sensitive cells.

GSH depletion

To examine the effect of glutathione depletion by L-buthionine sulphoximine on rhodamine efflux, cells were cultured in the presence of 25 μM BSO for 24 h. Intracellular GSH was quantified using an enzymatic technique (Salerno and Garnier-Suillerot, 2001).

Real-time fluorescence measurement of drug transport in living cells

Intracellular rhodamine accumulation was measured with a flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Beckman, St. Louis, MO). Cells, 106/ml, were put in the K+ buffer at 37°C and a small volume of the mother rhodamine solution was quickly added to get a CT rhodamine concentration. Fluorescence intensity was measured continuously until steady state was reached.

Mathematical calculations

The mathematical symbols used are the following:

N × 109 is the number of cells per liter.

Vcell is the volume of one cell (∼10−12 L cell−1).

Ce is the extracellular drug concentration.

𝒞 is the concentration of internal rhodamine bound to its receptors.

𝒞i is the concentration of free internal rhodamine.

- CT, the total concentration of rhodamine added to the cells, is equal to the concentration of rhodamine in the extracellular medium plus the concentration of rhodamine, bound and free, inside the cells:

(1) K is the mean binding constant for rhodamine to its receptors.

[receptors] is the concentration of internal receptors for rhodamine.

K = 𝒞/𝒞i × [receptors] or K = β × [receptors] with β = 𝒞/𝒞i.

ℱ is the molar fluorescence of rhodamine free in the cytosol.

ρ is the mean fluorescence quantum yield for rhodamine bound to its receptors.

A = ℱ × (1 + β × ρ) is the proportionality constant between the fluorescence intensity recorded via flow cytometry and 𝒞i.

V+, the rate of passive uptake for rhodamine, is equal to the number of moles that enter by passive diffusion into one cell per second.

V−, the rate of passive efflux for rhodamine, is equal to the number of moles that leave one cell by passive diffusion per second.

k is the passive permeability rate constant (which takes into account the permeability constant of the molecule, the membrane exchange area per cell).

V+ = k × Ce and V− = k × 𝒞i.

Va, the rate for outward pumping, is equal to the number of moles that are pumped out by MRP1, per cell and per second.

ka is the rate constant for outward pumping at limiting low substrate concentration.

Va = ka × 𝒞i.

We intend to derive, from the data ka, the rate constant for outward pumping at limiting low substrate concentration, and for this purpose we need to determine 1), the concentration of free internal rhodamine; 2), the mean binding constant for rhodamine to its receptors, whatever they are; 3), the mean fluorescence quantum yield for rhodamine bound to its receptors, whatever they are; 4), the passive permeability rate constant; and 5), the rate constant for outward pumping at limiting low substrate concentration.

The determination of the kinetic parameters, e.g., the maximum rate, VM, and the Michaelis constant, Km, characteristic of the transporter-mediated efflux of drugs, required the measurement of Va and 𝒞i. When Va can be determined for various intracellular free drug concentrations 𝒞i, the maximal efflux rate (VM) and the apparent Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) can be computed by nonlinear regression analysis of transport velocity Va vs. 𝒞i, assuming that the transport follows the Michaelis equation

|

(2) |

In many cases, the complete curve Va = f(Ci) cannot be obtained and therefore it is not possible to obtain these two parameters characteristic of a transporter. However, if 𝒞i is much lower than Km, Eq. 2 becomes

|

or

|

(3) |

In this work, the rate of MRP1-associated efflux of rhodamine was calculated at the steady state, taking into account the following points: 1), the diffusion (influx and efflux) of rhodamine through the membrane is passive, so it obeys Fick's law; 2), whatever the type of cells, i.e., either drug-sensitive or drug-resistant, at steady state the rate of rhodamine influx (V+)s is equal to that of rhodamine efflux; and 3), for drug-resistant cells, the efflux is composed of two terms: a passive efflux of the molecule (V−)s, and an MRP-mediated efflux of the molecule (Va)s. It follows that

|

or

|

(4) |

Taking into account Eqs. 3 and 4, this becomes

|

(5) |

Therefore, ka determination requires k, Ce, and 𝒞i.

As it will be demonstrated below, the determination of k requires the knowledge of ℱ (the molar fluorescence of rhodamine free in the cytosol), of ρ (the mean fluorescence quantum yield for rhodamine bound to its receptors whatever they are), and of β = 𝒞/𝒞i. For this purpose, sensitive cells were incubated with rhodamine in K+ buffer. Under these experimental conditions, where Δψ = 0, the positively-charged rhodamines cannot accumulate inside mitochondria. However, they can interact with different receptors within the cell. The intracellular concentration of rhodamine bound to these receptors (𝒞) is in thermodynamic equilibrium with the rhodamine free in the cytosol (𝒞i). A mean binding constant can be defined as K = 𝒞/𝒞i × [receptors]. As we were working under experimental conditions where the receptors were in large excess compared to the intracellular rhodamine concentration, the concentration of free receptors could be considered as constant. It follows that the binding of the different rhodamine to the receptors can be characterized by β = 𝒞/𝒞i. The concentration of rhodamine inside the cells is therefore

|

(6) |

The size of cells used being very homogeneous, we can consider that the number of moles per cell does not vary so much from one cell to the other. The fluorescence of one cell measured using flow cytometry (Fcyto) is therefore proportional to the concentration of rhodamine in the cell. Fcyto is composed of two terms: the fluorescence of the free internal rhodamine (ℱ × 𝒞i) and that of the rhodamine bound to its receptors (ρ × ℱ × 𝒞).

Therefore

|

(7) |

Let us consider sensitive cells, N × 109 L, in K+ buffer, incubated with rhodamine at concentration CT. At steady state, Ce = 𝒞i, and taking into account Eqs. 1 and 6, it becomes

|

(8) |

and

|

(9) |

ℱ, ρ, and β can then be computed by a nonlinear analysis of Fcyto, measured at fluorescence steady state, vs. N.

The parameter k was determined from the continuous monitoring of the fluorescence signal, Fcyto (flow cytometry), when sensitive cells in K+ buffer were incubated with rhodamine. Actually, when cells are incubated with rhodamine, before reaching the steady state, rhodamine enters continuously into the cells. According to Eq. 6, during dt, the increase of the intracellular rhodamine concentration is (1 + β) × dCi and the increase of the number of moles per cell and per second is

|

(10) |

or

|

(11) |

The integration of this equation yields

|

(12) |

However, according to Eq. 7, it becomes

|

(13) |

which can be written more simply as

|

(13a) |

with

|

In this expression, Ce can be taken equal to CT, and the other parameters are constant. It follows that the term k/(1 + β) × Vcell (and then k), can be computed by a nonlinear analysis of Fcyto vs. t data. It should be emphasized that these calculations are valid if the rate of interaction of the dye with its receptors is much higher than the rate of its passive diffusion through the membrane.

RESULTS

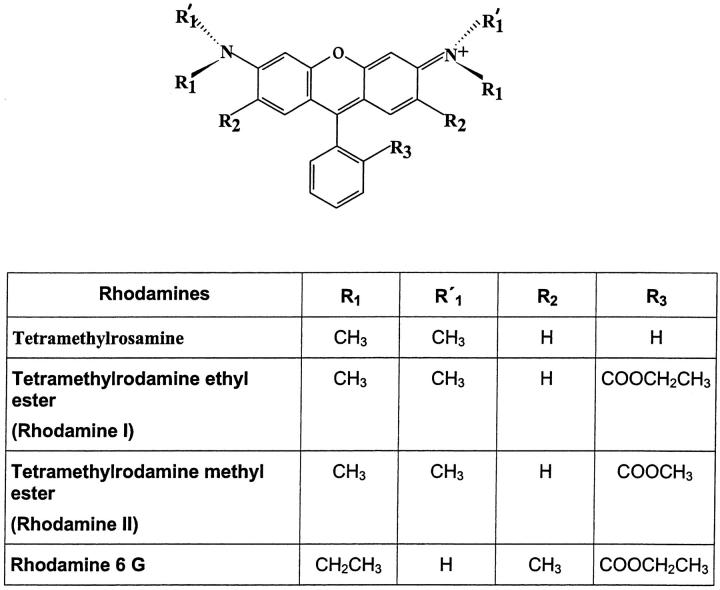

The rhodamines used in the present study (Fig. 1) have a permanent positive charge. Due to the membrane potentials, all these rhodamine dyes were accumulated in wild-type drug-sensitive cells and were localized mainly in the mitochondria. Their accumulations were lower in resistant cells, strongly suggesting that these compounds were pumped out by MRP1. The aim of the present work was to determine the efficiency of the MRP1-mediated efflux of these rhodamines which can be characterized, as we have shown in the experimental section, by the coefficient of active efflux ka = k × [(Ce/𝒞i) − 1]. This requires the measurement of 1), the coefficient of passive diffusion k; and 2), the gradient of concentration generated by the pump, e.g., the extracellular Ce and the cytosolic 𝒞i free drug concentrations at steady state. The following experiments were designed to determine these three parameters.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the rhodamines used.

If we consider sensitive cells in Na+ buffer, the gradient of concentration through the plasma membrane depends on the membrane potential. However, for resistant cells, this gradient of concentration depends on two parameters: 1), the plasma membrane potential which tends to make the cytosolic rhodamine concentration higher than the extracellular one; and 2), the MRP1-mediated efflux of rhodamine which tends to decrease the rhodamine concentration in the cytosol versus the extracellular one. Under these conditions it is impossible to determine the gradient of concentration generated by the pump only. However, experiments performed in the absence of membrane potential, e.g., in K+ buffer, can solve the problem since the gradient of concentration through the plasma membrane is then only due to the pump. The following experiments were therefore performed in such buffer. We have first checked that the MRP1-mediated efflux of drug was similar in Na+ and K+ buffers.

Comparison of the MRP1-mediated efflux of daunorubicin (DNR) in the presence and in the absence of membrane potential

First, we have checked that in K+ buffer plasma and mitochondrial potentials were dissipated. We have performed a continuous spectrofluorometric monitoring of the fluorescence signal of a cationic rhodamine (TMR 0.2 μM) during incubation with sensitive cells in a 1-cm quartz cuvette containing Na+ buffer on the one hand and K+ buffer on the other hand. In Na+ buffer a strong decrease of the fluorescence signal was observed due to the accumulation of the lipophilic cation mainly in the mitochondrial compartments, leading to a quenching of the fluorescence signal. However, when the same experiments was performed in K+ buffer, no quenching of the fluorescence was observed—from which we inferred that there was no accumulation of TMR inside the cells and therefore that the potentials were eliminated.

We have measured the accumulation of DNR (cells, 106/ml, and 1 μM DNR) in GLC4 and GLC4/ADR cells in Na+ and K+ buffers (Δψ = 0) respectively, using a method previously described (Marbeuf-Gueye et al., 1998). We observed that the accumulation of DNR in sensitive cells was much lower than in sensitive cells and that, in both cases, the accumulation did not depend on the membrane potentials.

Uptake of rhodamine by GLC4 cells in the absence of membrane potential

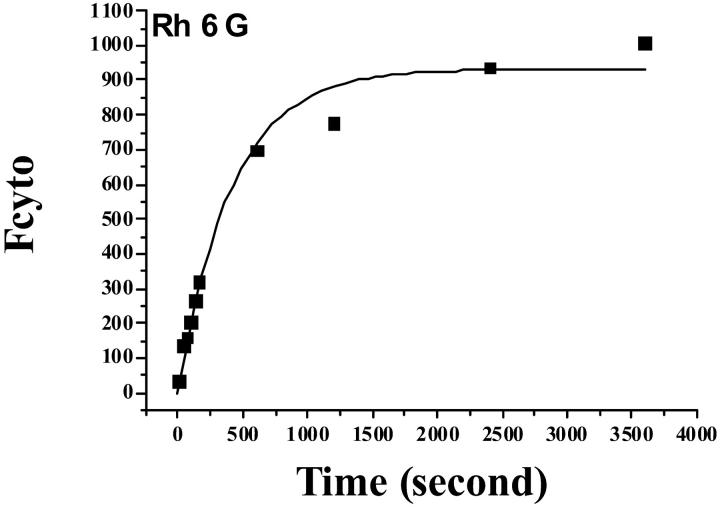

A continuous cytofluorometric monitoring (Facscan) of the fluorescence signal of sensitive cells incubated in K+ buffer with various rhodamine concentrations CT (0.02–0.2 μM) was performed. Fig. 2 shows such a record for Rh6G. Data points of Fcyto vs. time (or the experimental records) were fitted to Eq. 13a) and the a- and b-parameters determined (see Table 1) with b = k/Vcell × (1 + β).

FIGURE 2.

Uptake of Rh 6G by GLC4 cells. Cells, 106/ml, were incubated with 0.2 μM Rh 6G in K+ buffer. The cytofluorometry signal (Fcyto) was recorded as a function of time. The data points are from a representative experiment. They were fitted to Eq. 13a, Fcyto = a × [1 × exp (− b × t)], and the coefficients a and b calculated (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters for rhodamine derivatives and daunorubicin

| Rhodamine | 𝒞i/Ce | a* | b × 10−3 s−1* | k × 10−13 L cell−1 s−1 | ka × 10−13 L cell−1 s−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh I | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 91 ± 18 | 12 ± 3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| Rh II | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 91 ± 18 | 12 ± 2 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.5 |

| TMR | 0.78 ± 0.08 | 278 ± 55 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 9.3 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 0.5 |

| Rh 6G | 0.55 ± 0.05 | 930 ± 180 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| Daunorubicin | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 118 ± 24 | 0.84 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 8 ± 4 |

| 3.1 ± 0.5† | 13 ± 3† | ||||

| As(OH)3 | 0.0045 ± 0.0010 | 0.0061 ± 0.0015‡ | |||

| GSH | 0.0044 ± 0.0015§ | ||||

| Calcein | 0.006 ± 0.002¶ |

Active efflux, ka, and passive, k, coefficients. Gradient of concentration 𝒞i/Ce through the plasma membrane generated by MRP1. Data are mean ± SE of at least three determinations.

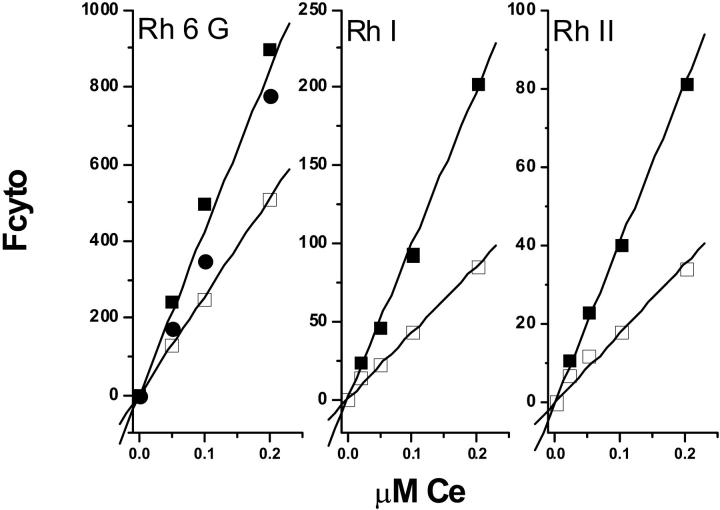

For each concentration the value of Fcyto at steady state was determined. Fig. 3 shows the plot of Fcyto as a function of CT = Ce. Actually the accumulation of rhodamine in the cells being very low, the extracellular concentration was equal to the total rhodamine concentration added to the cells. This was verified as follows: a continuous spectrofluorometric monitoring (PerkinElmer LS50B spectrofluorometer) of the fluorescence signal of the rhodamine during incubation with cells in a 1-cm quartz cuvette containing K+ buffer was performed. In a typical experiment, sensitive cells, 106/ml, were incubated with 0.2 μM rhodamine. No modification of the fluorescence signal was observed versus time. At steady state, cells were centrifuged and the fluorescence of the supernatant measured. The intensity of the signal was very similar to that observed in the presence of cells. Our conclusion was that it is reasonable, under these conditions, to consider that Ce is equal to CT.

FIGURE 3.

Intensity of the flow cytometry signal recorded at steady-state fluorescence from sensitive and resistant GLC4 cells incubated with Rh6G, Rh I, or RhII. The intensity of the signal (Fcyto) is plotted as a function of the extracellular concentration, Ce, of Rhodamine. Cells, 106/ml, were incubated with various concentrations of rhodamine in K+ buffer. GLC4/ADR cells (□); GLC4 cells (▪); and GSH-depleted GLC4/ADR cells (•). The data points are from a representative experiment.

In these experiments, the very important point is that, at steady state, when Δψ = 0, there is a transmembrane equilibrium—and the free rhodamine activity should be the same on both sides of the plasma membrane. Here, the concentrations being low, we have made the reasonable assumption that concentration could be used in place of activity, e.g., Ce = 𝒞i, therefore CT = 𝒞i. As can be seen, there is a linear dependency of Fcyto as a function of CT = 𝒞i:Fcyto = A × 𝒞i, where A is a constant which depends on the nature of the rhodamine. However, the fluorescence signal recorded from the cells is due not only to the rhodamine free (𝒞i) in the cytosol but also to the rhodamine bound (𝒞) to intracellular sites and the ratio of these two concentrations is a constant β = 𝒞/𝒞i. As we have shown in the experimental section, Fcyto = ℱ × (1 + β × ρ) × 𝒞i, and therefore A = ℱ × (1 + β × ρ).

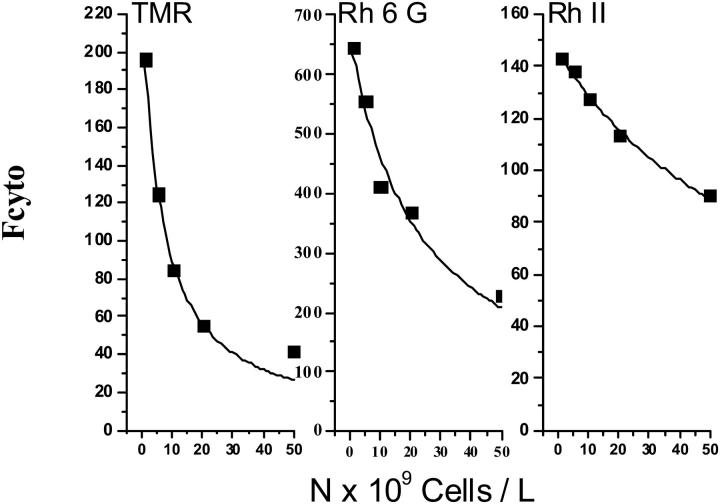

The following experiments were designed to determine β. In this set of experiments cells were incubated with always the same rhodamine concentration CT = 0.2 μM but the number of cells used during the incubation in K+ buffer was varied from 105 to 5 × 107 per ml. The flow cytometry signal was measured at steady state. Fig. 4 shows typical records of Fcyto as a function of the cells' number for TMR, Rh 6G, and RhII. As can be seen, the intensity of the signal decreased when the number of cells increased. Data points of Fcyto vs. number of cells were fitted to Eq. 9 and the values of ℱ, ρ, and β were estimated. To check if β-values in resistant cells were similar to those observed in sensitive cells, experiments were performed with energy-depleted resistant cells. The values of the three parameters ℱ, ρ, and β were the same respectively as those determined for sensitive cells. They are reported in Table 2. The β-values for RhI and RhII rhodamines were comparable; however, the β-value for TMR was ∼15-fold higher. It was then possible to calculate the k-value (Table 1).

FIGURE 4.

Intensity of the flow cytometry signal recorded at steady-state fluorescence from GLC4 cells incubated with 0.2 μM TMR, Rh 6G, or RhII in K+ buffer. The intensity of the signal (Fcyto) recorded plotted as a function of the number of cells per liter. The data points are from a representative experiment. They were fitted to Fcyto = ℱ × [CT × (1 + β × ρ)] / [1 + 10−3 × N × (1 + β)], as shown by the solid line, and the values of ℱ, β, and ρ were estimated.

TABLE 2.

| Rhodamine | β | ℱ × 106 (1 μM) | ρ | a* = (1 + β × ρ) ℱ × Ce |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh I | 7 ± 1 | 380 ± 40 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 124 ± 32 |

| Rh II | 11 ± 1 | 450 ± 40 | 0.054 ± 0.002 | 143 ± 37 |

| TMR | 147 ± 15 | 200 ± 20 | 0.030 ± 0.003 | 216 ± 56 |

| Rh 6G | 45 ± 4 | 610 ± 60 | 0.10 ± 0.1 | 671 ± 175 |

Parameters characteristic of the interaction of rhodamines with cells; Eq. 9 was used to fit the data, such as shown in Fig. 4. Data are mean ± SE of three determinations. β, mean binding constant of rhodamine to cellular components; ℱ, micromolar fluorescence of rhodamine free in the cytosol; and ρ, fluorescence quantum yield of rhodamine bound to cellular components.

The a-parameter from Eq. 13a was calculated using the β-, ℱ-, and ρ-values.

Determination of 𝒞i, the concentration of free rhodamine in the cytosol of GLC4/ADR

Resistant cells, 106/ml, were incubated in K+ buffer, in the presence of different concentrations of rhodamine ranging from 0.02 to 0.2 μM. At steady state, the flow cytometry signal (Fcyto) was recorded and the plot of Fcyto as a function of CT is shown in Fig. 3. As can be seen, for a same extracellular drug concentration, the fluorescence signal is lower in resistant cells than in sensitive cells. Similar experiments were performed in energy-depleted cells and the values of Fcyto obtained were similar to that determined for sensitive cells. This allowed us to say that the A-parameter value was the same for both sensitive and resistant cells. Therefore, from the Fcyto value measured in resistant cells we can easily calculate the 𝒞i value and then the gradient of concentration 𝒞i/Ce generated by the pump. This calculation was performed for the various concentrations of rhodamines used (0.02–0.2 μM), and we did not observe significant variation of the gradient value, indicating that we were working under conditions where the MRP1 transporter was far from being saturated. The values of the gradient generated by the pump are reported in Table 1; they are within the range of 0.35–0.78.

Determination of the active efflux coefficient ka

Once the parameters k, Ce, and 𝒞i were measured, it was easy to calculate ka according to Eq. 5. The values are reported in Table 1. For the sake of comparison, the values for DNR are also shown.

Validation of the method

The method was validated in two different ways.

Using Eq. 13a to fit the data in Fig. 2, we have determined a and b. On the other hand, using the data of a completely different set of experiments, and fitting them with Eq. 9, we have determined ℱ-, β-, and ρ-values. These values were then used to recalculate a = (1 + β × ρ) × ℱ × Ce. As can be seen in Tables 1 and 2, the values of a obtained either from the data Fcyto = f(t) or from the data Fcyto = f(N) (at steady state) are in good agreement.

We have further validated the method using a totally different substrate for which the k+/− and ka parameters were previously determined using a totally different methodology. For this purpose we have used daunorubicin. We have recorded Fcyto as a function of time when cells (106/mL) were incubated with 1 μM DNR to avoid accumulation of the drug (which is a weak base in acidic compartments; Loetchutinat et al., 2001); the experiments were performed in the presence of 20 nM concanamycin A. DNR is well-known to accumulate in the nucleus and therefore the extracellular concentration cannot be consider as constant. When taken into account as a function of time, the modification of the extracellular drug concentration is always

|

(13a) |

but in the a and b expressions there is a correction factor of

|

and then

|

and

|

Of course this complete expression can be used for rhodamines, but in this case, the D-value is close to 1 (because of the relatively low value of β).

The a-, b-, D- and β-values obtained are the following:

a = 118 (fluorescence arbitrary units)

b = 8.4 × 10−4 s−1

D = 1.4

β = 400, which yields k = (3.5 ± 0.5) × 10−13 L cell–1 s–1.

On the other hand,

𝒞i/Ce = 0.30 ± 0.04, which yields ka = (0.8 ± 0.4) × 10−12 L cell–1 s–1.

These values are in good agreement with those previously obtained with a methodology that we have largely developed and used for the determination of the rate of uptake and pump-mediated efflux of anthracycline in living cells (Mankhetkorn et al., 1996; Marbeuf-Gueye et al., 1998). These values are k = (3.1 ± 0.5) × 10−13 L cell−1 s–1 and ka = (1.3 ± 0.3) × 10−12 L cell−1 s−1.

Rhodamine uptake in GSH-depleted GLC4/ADR cells

Cells were incubated in the culture medium for 24 h in the presence of 25 μM BSO. Under these conditions the concentration of GSH remaining inside the cells was <0.2 mM (Salerno and Garnier-Suillerot, 2001). Cells were then incubated with 0.2 μM rhodamine. For both cell lines the uptake was comparable to that observed for sensitive cells. These results clearly indicate that GSH is involved in the decrease of rhodamine retention in resistant cells.

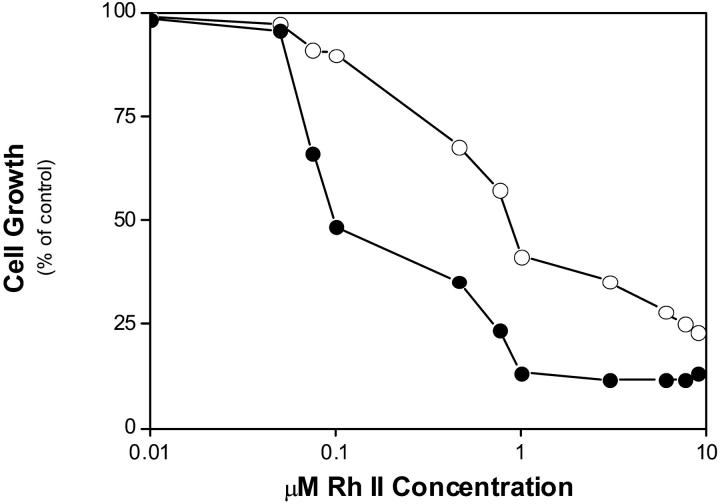

Cell-growth inhibition

Cell lines that we used were made resistant by co-culture with doxorubicin. The IC50 value obtained with RhII for sensitive and resistant GLC4 cells are 0.09 ± 0.02 μM and 0.75 ± 0.15 μM, respectively (Fig. 5). These values represent means ± SD of triplicate determinations. The resistance factor was equal to 8. For comparison, the IC50 obtained with doxorubicin under similar experimental conditions were (9 ± 2) × 10 −3 μM and 0. 670 ± 0.070 μM for sensitive and resistant cells respectively, with RF = 74.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of RhII on the growth of GLC4 and GLC4/ADR cells. Cells were seeded at 105 cells/ml and grown in the absence and the presence of increasing concentrations of RhII (0–10 μM). Cell numbers were determined 72 h later. Cell growth is expressed as % of control in the absence of drug. GLC4 cells (•); and GLC4/ADR cells (○). The data points are from a representative experiment.

DISCUSSION

It has long been known that Rh123 is a P-gp substrate. More recently, the transport of other rhodamines such as TMR, Rh I, Rh II, and Rh6G by P-gp has been demonstrated (Lu et al., 2001; Eytan et al., 1997) and the kinetics parameters characteristic of their transport have been measured (Lu et al., 2001; Loetchutinat et al., 2003). In the case of MRP1, these things are far from clear. Zaman et al. (1994) have demonstrated cross-resistance to Rh123 in MRP1 transfected SW 1573 cells. Daoud et al. (2000) have shown that the IC50 of HeLa-MRP1 is ∼14- and ∼fivefold higher than HeLa cells for VP16 and Rh123 respectively. Minderman et al. (1996) have demonstrated that in addition to being a substrate for P-gp, Rh123 is also a substrate for MRP-mediated drug efflux, but that this efflux takes place at a slower rate compared to P-gp. However, the comparison of the uptake of Rh123 by GLC4/ADR and GLC4 using flow cytometry has shown that the fluorescence signal recorded from GLC4 was less than that observed with GLC4/ADR cells (Feller et al., 1995; Garnier-Suillerot, unpublished data). More recently, Daoud et al. (2000) have reported on the characterization of MRP1 interactions with Rh123 using the photoactive analog iodoaryl azido Rh123, and shown that it interacts directly and specifically with MRP1.

To our knowledge, up to now the MRP1-mediated efflux of one rhodamine only, Rh123, has been explored and no study was designed to determine the kinetics parameters of this transport.

Measurement of the kinetic characteristics of substrate transport is a powerful approach to enhancing our understanding of their function and mechanism. In this article, we present data that characterized the transport of several rhodamine analogs which are positively charged. We took advantage of the intrinsic fluorescence of rhodamines, and performed a flow-cytometric analysis of dye accumulation in the wild-type, drug-sensitive GLC4 cells that do not express MRP1. For its MDR subline, which displays high level of MRP1, the resistance factor for daunorubicin was equal to 23 (Marbeuf-Gueye et al., 1999). The measurements were made in real-time using intact GLC4/ADR and GLC4 cells. We clearly show that GLC4/ADR cells are cross-resistant to rhodamines, that there is an energy-dependent efflux of rhodamines in GLC4/ADR cells, and that this efflux is GSH-dependent inasmuch as no efflux was observed after GSH depletion with BSO. Rh123 is widely used as a structural marker for mitochondria as an indicator of mitochondrial activity and, therefore, the relative accumulation of positively charged rhodamine in parental and resistant cells is likely to be influenced by any differences in mitochondrial number or membrane potential between the cell types in addition to effects of active transporters. For this reason we have studied the MRP1-mediated efflux of rhodamine in the absence of membrane potential after having checked that the MRP1-mediated efflux of drug (in this case, daunorubicin) was not potential-dependent.

To characterize the MRP1-mediated efflux of rhodamines, the parameter ka was calculated. As shown (Materials and Methods, this article; and Marbeuf-Gueye et al., 1998, 1999), ka is proportional to the ratio VM/Km and is very convenient to evaluate the efficiency of a transporter for any substrate. The determination of ka requires the measurement of the gradient of concentration, i.e., Ce vs. 𝒞i, which is generated by the presence of the pump. Thanks to the use of two independent fluorometric techniques, macrofluorescence and flow-cytometry, it is possible to directly determine the free rhodamine concentration in the cytosol and in the extracellular medium. Actually, our data clearly show that the cytofluorometric signal, in cells without membrane potential, is proportional to the amount of rhodamine free in the cytosol. This observation allows the further determination of the concentration of drug free in the cytosol of resistant cells. The determination of ka also requires the measurement of the rate of passive diffusion of the dye through the plasma membrane. For this reason, we have determined the ratio of the drug bound to the drug free in the cytosol, which subsequently allows the determination of the real number of molecules that penetrate per second into one cell and therefore the true rate of passive diffusion of the dye.

As can be seen in Table 1, the ka values determined for the four molecules are of the same order of magnitude, ranging from 0.8 to 2.6 × 10−13 L cell−1 s−1. One of our aims was to compare the MRP1-mediated efflux of these rhodamine analogs to that of other substrates obtained previously using the same cell line. To help this comparison, the values of 𝒞i/Ce, k, and ka for daunorubicin are reported in Table 1, together with the ka value for GSH, calcein, and As(OH)3. Compared to previously published data, the efficiency of the MRP1-mediated rhodamine pumping is ∼10-fold less than for anthracycline (Marbeuf-Gueye et al., 1999) but ∼100-fold more than for GSH (Salerno and Garnier-Suillerot, 2001), calcein (Essodaïgui et al., 1998), and As(OH)3 (Salerno et al., 2002). In addition, the present study shows that the efficiency of the MRP1-mediated rhodamine pumping is ∼10-fold less than the efficiency of the P-gp-mediated rhodamine pumping, whereas the efficiency of the anthracycline pumping was very similar for both transporters.

The findings presented here are the first to show quantitative information about the kinetics parameters for MRP1-mediated efflux of rhodamine analogs in intact cells.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from l'Université Paris XIII and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

Abbreviations used: MRP1, multidrug resistance associated protein; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; MDR, multidrug resistance; Rh 6G, Rhodamine 6G; TMR, tetramethylrosamine; Rh I, tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester or rhodamine I; Rh II, tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester or rhodamine II; Rh 123, Rhodamine 123; GSH, glutathione; BSO, L-buthionine-(S,R) sulphoximine.

References

- Cole, S. P. C., and R. G. Deeley. 1998. Multidrug resistance mediated by the ATP-binding cassette transporter protein MRP. Bioessays. 20:931–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud, R., C. Kast, P. Gros, and E. Georges. 2000. Rhodamine 123 binds to multiple sites in the multidrug resistance protein (MRP1). Biochemistry. 39:15344–15352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eytan, G. D., R. Regev, G. Oren, C. D. Hurwitz, and Y. G. Assaraf. 1997. Efficiency of P-glycoprotein-mediated exclusion of rhodamine dues from multidrug-resistant cells is determined by their passive transmembrane movement rate. Eur. J. Biochem. 248:104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essodaïgui, M., H. Broxterman, and A. Garnier-Suillerot. 1998. Kinetic analysis of calcein and calcein—acetoxymethylester efflux mediated by the multidrug resistance protein and P-glycoprotein. Biochemistry. 37:2243–2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller, N., C. M. Kuiper, J. Lankelma, J. K. Ruhdal, R. J. Scheper, H. M. Pinedo, and H. J. Broxterman. 1995. Functional detection of MDR1/P170 and MRP/P190-mediated multidrug resistance in tumour cells by flow cytometry. Br. J. Cancer. 72:543–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fojo, A. T., K. Ueda, D. J. Slamon, D. G. Poplack, M. M. Gottesman, and I. Pastan. 1987. Expression of a multidrug-resistance gene in human tumors and tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:3004–3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, C., G. Valdimarsson, D. Hipfner, K. C. Almquist, S. P. C. Cole, and R. G. Deeley. 1994. Overexpression of multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) increases resistance to natural product drugs. Cancer Res. 54:357–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loetchutinat, C., W. Priebe, and A. Garnier-Suillerot. 2001. The intravesicular accumulation of anthracyclines in multidrug resistant K562 cells is less than in sensitive cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:4459–4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loetchutinat, C., S. Chantarawan, C. Marbeuf-Gueye, and A. Garnier--Suillerot. 2003. New insights into the P-glycoprotein-mediated effluxes of rhodamines. Eur. J. Biochem. 27:476–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P. H., R. H. Liu, and F. J. Sharom. 2001. Drug transport by reconstituted P-glycoprotein in proteoliposomes. Effect of substrates and modulators, and dependence on bilayer phase state. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:1687–1697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankhetkorn, S., F. Dubru, J. Hesschenbrouck, M. Fiallo, and A. Garnier-Suillerot. 1996. Relation among the resistance factor, kinetics of uptake, and kinetics of the P-glycoprotein-mediated efflux of doxorubicin, daunorubicin, 8-(S)-fluoroidarubicin, and idarubicin in multidrug-resistant K562 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 49:532–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marbeuf-Gueye, C., H. Broxterman, F. Dubru, W. Priebe, and A. Garnier-Suillerot. 1998. Kinetics of anthracycline efflux from multidrug resistance protein-expressing cancer cells compared with P-glycoprotein-expressing cancer cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 53:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marbeuf-Gueye, C., D. Ettori, W. Priebe, H. Kozlowski, and A. Garnier-Suillerot. 1999. Correlation between the kinetics of anthracycline uptake and the resistance factor in cancer cells expressing the multidrug resistance protein or the P-glycoprotein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1450:374–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minderman, H., U. Vanhoefer, K. Toth, M. B. Yin, M. D. Minderman, C. Wrzosek, M. L. Slovak, and Y. M. Rustum. 1996. DiO2(3) is not a substrate for multidrug resistance protein (MRP)-mediated drug efflux. Cytometry. 25:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, D., and T. Skovsgaard. 1992. P-Glycoprotein as multidrug transporter—a critical review of current multidrug resistant cell lines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1139:169–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwnica-Worms, D., R. Jacob, C. R. Horres, and M. Lieberman. 1983. Transmembrane chloride flux in tissue-cultured chick heart cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 81:731–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno, M., and A. Garnier-Suillerot. 2001. Kinetics of glutathione and daunorubicin efflux from multidrug resistance protein overexpressing small-cell lung cancer cell. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 421:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno, M., M. Petroutsa, and A. Garnier-Suillerot. 2002. The MRP1-mediated effluxes of arsenic and antimony do not require arsenic-glutathione and antimony-glutathione complex formation. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 34:135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twentyman, P. R., T. Rhodes, and S. Rayner. 1994. A comparison of rhodamine 123 accumulation and efflux in cells with P-glycoprotein-mediated and MRP-associated multidrug resistance phenotypes. Eur. J. Cancer. 30A:1360–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, G. J. R., M. J. Flens, M. R. Vanleusden, M. Dehaas, H. S. Mulder, J. Lankelma, M. Pinedo, R. Scheper, J. Baas, H. J. Broxterman, and P. Borst. 1994. The human multidrug resistance-associated protein MRP is a plasma membrane drug-efflux pump. Proc. Natl . Acad. Sci. USA. 91:8822–8826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zijlstra, J. G., E. G. E. De Vries, and N. H. Mulder. 1987. Multifactorial drug resistance in an adriamycin-resistant human small cell lung carcinoma cell line. Cancer Res. 47:1780–1784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]