Abstract

We present a new method for creating patches of fluid lipid bilayers with conjugated biotin and other compounds down to 1 μm resolution using a photolithographically patterned polymer lift-off technique. The patterns are realized as the polymer is mechanically peeled away in one contiguous piece in solution. The functionality of these surfaces is verified with binding of antibodies and avidin on these uniform micron-scale platforms. The biomaterial patches, measuring 1 μm–76 μm on edge, provide a synthetic biological substrate for biochemical analysis that is ∼100× smaller in width than commercial printing technologies. 100 nm unilamellar lipid vesicles spread to form a supported fluid lipid bilayer on oxidized silicon surface as confirmed by fluorescence photobleaching recovery. Fluorescence photobleaching recovery measurements of DiI (1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiIC18(3))) stained bilayer patches yielded an average diffusion coefficient of 7.54 ± 1.25 μm2 s−1, equal to or slightly faster than typically found in DiI stained cells. This diffusion rate is ∼3× faster than previous values for bilayers on glass. This method provides a new means to form functionalized fluid lipid bilayers as micron-scale platforms to immobilize biomaterials, capture antibodies and biotinylated reagents from solution, and form antigenic stimuli for cell stimulation.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, micron-scale patterning methods have been developed to immobilize functional biomolecules on silicon dioxide substrates for biosensor and bioassay applications. Many techniques use lithographic methods, borrowed from microelectronics fabrication technology, to produce patterned biomolecules on a surface (Branch et al., 2000). Photopatterning has been used for enzymes, antibodies, and nucleic acids in the development of biochips on silicon, glass, and plastic substrates (Dontha et al., 1997).

There are several common technologies used to pattern materials on silicon and glass substrates including microarray patterning, ink jet printing, electron beam patterning, and microcontact printing. Microarray printing is commonly used to create biomaterial arrays on glass using a quill or flat-headed pin to spot sizes ranging from 50 to 300 μm (Fitzgerald, 2002). However, pin damage as well as variations in glass substrates thickness, humidity, sample wetting properties, and pin pressure can lead to differences in spot diameter and thickness. Ink jet printing is a noncontact printing technique with commercial applications offering 1440 dpi resolution (17.6 μm). This technique would have difficulty achieving smaller features necessary for subcellular patterning (e.g., below 5 μm). Electron beam lithography involves striking a surface with a beam of electrons with patterning capabilities below 100 nm. E-beam patterning can be used to burn away biomaterials from a coated surface and leave behind unmodified regions. However, this technique is a serial process that requires a significant amount of time to pattern micron scale features over a whole wafer. Microcontact printing is another patterning method that uses a polydimethyl siloxane (PDMS) elastomeric stamp to micropattern biomaterials (Biebuyck et al., 1997; Xia and Whitesides, 1998; Yang et al., 1998; James et al., 1998).

The micropatterning of lipids offers new possibilities for studies of lipid mobility kinetics, diagnostics, and the study of cellular interactions with lipid-associated biomolecules. Micropatterned lipids have been examined for their stability and sensitivity (Tien and Salamon, 1990; Zviman and Tien, 1991; Sackman, 1996; Groves and Boxer, 1995, 2002; Groves et al., 1997, Cremer and Boxer, 1999, Cremer et al., 1999), as well as other parameters including lateral diffusion of lipid molecules (Hovis and Boxer, 2000), and mobility of lipids within confined protein barriers (Kung et al., 2000). To date, the most widely used approach toward lipid patterning has been microcontact printing. This approach has allowed deposition of lipids down to feature sizes as small as 5 μm (Kam and Boxer, 2001). While microcontact printing is a versatile and widely used method for patterning a variety of materials, it has the potential for surface fouling, nonspecific binding after primary layer application, and molecular denaturation of associated biomolecules due to drying. Deformation of the PDMS stamp has been shown to alter the expected size of the patterned material (Hovis and Boxer, 2000). Other PDMS limitations include elastomer shrinkage after curing, swelling in some solvents, and inherent elasticity that makes patterning over large areas a challenge.

In our research we sought to develop a new method for patterning uniform and reproducible lipid bilayers. For this we utilize photolithography in combination with a recently described polymer lift-off technique (Ilic and Craighead, 2000, Orth et al., 2003a). In comparison to the patterning techniques listed above, the polymer lift-off method can form uniform features down to 1 μm, which is a significant size reduction over microarray and ink jet printing. The technique has been adapted to photolithography with use of steppers, which can pattern a whole wafer faster and at a lower cost than the serial process of electron beam lithography. Since the polymer is a temporary stencil that is removed in one piece, it circumvents the problems of PDMS residue. Furthermore, the polymer lift-off technique avoids the PDMS pattern distortion and nonuniformity over large surface areas.

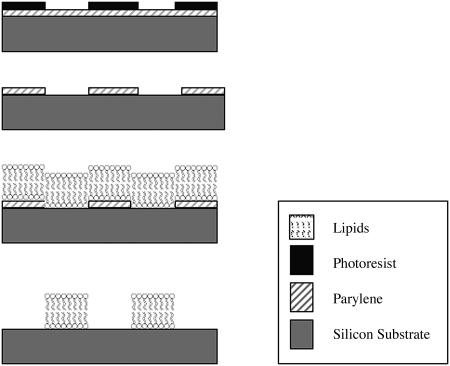

With the polymer lift-off approach, di-para-xylylene (Parylene C) is vapor deposited on a silicon substrate to produce a conformal polymer film that adheres weakly to the surface (Fig. 1). After the addition of a photoresist, the film is patterned using conventional photolithography, and is then subjected to a controlled reactive ion etch (RIE) that removes exposed regions of Parylene down to the silicon dioxide substrate. The RIE also creates a more hydrophilic silicon dioxide surface in the exposed regions compared to the nonexposed regions of the substrate. We hypothesized that lipid vesicles applied to the patterned oxidized silicon substrate would adhere to regions of exposed silicon dioxide and form lipid bilayers. The patterned lipids could then be submerged in aqueous solutions and the Parylene removed, leaving sharp boundaries between surface features. Since neither drying nor compressive force would be used with this technique, denaturation and attendant loss of functionality of more delicate molecules (viz. proteins) associated with the bilayers would be obviated. Fluorescence photobleaching recovery (FPR) (Axelrod et al., 1976; Brown et al., 1999) has been used to study the mobility of lipid molecules in cellular lipid bilayers as well as supported lipid bilayers. We describe the use of this method to pattern lipid bilayers of various feature sizes as small as 1 μm on a silicon substrate. The bilayers are fluid in nature, and model ligands incorporated into them retain their functionality and the potential applications of this technology. The lipid patterns are functionalized with dinitrophenyl ((DNP)-cap-DPPE) and biotin. The patterning of lipids with DNP serves as a model system for the patterning of chemicals for cell stimulation. The patterning of biotin enables the application of avidin-biotin technology, which is a versatile method for immobilizing biotinylated biomaterials from solution (Green, 1975), even under stringent conditions (Savage et al., 1994). This capability extends the patterning demonstrated by photobiotin in this laboratory (Orth et al., 2003b).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of the fabrication steps adapted from Ilic and Craighead (2000). (Top) Photoresist patterning using optical lithography. (Second from top) Reactive ion etching of Parylene and removal of the top photoresist layer. (Second from bottom) POPC lipid immobilization. (Bottom) Peeling of Parylene, resulting in a lipid bilayer.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Silicon wafer preparation and Parylene deposition

3-inch 〈100〉 type silicon wafers (Silicon Qwest International, Santa Clara, CA) were cleaned in base and acid baths to remove surface contaminants and baked at 1100°C for 50 min in a wet oxide furnace to grow a 500 nm thermal oxide layer. A conformal layer of Parylene C was deposited using a PDS-2010 Labcoater 2 Parylene deposition system (Specialty Coating Systems, Indianapolis, IN). 1 g of Parylene dimer was used to deposit ∼1 μm thick Parylene film on five 3-inch silicon wafers.

Photolithography

1.2 μm of OCG OiR 620-7i photoresist was applied to the Parylene-coated silicon wafers. The samples were prebaked for 1 min at 90°C and exposed using standard photolithographic techniques with a 10× stepper (Fig. 1, top). After development in Microposit MIF 300 developing solution (Shipley, Marlboro, MA), the exposed portions of the Parylene film were subjected to an oxygen-based RIE etching step using a Plasma Therm 72 with a radio frequency (RF) power density at 0.255 W/cm2 (Fig. 1, second from top). After etching, the samples were dipped into a beaker of acetone to remove residual resist, rinsed with isopropyl alcohol, and washed in deionized water. The samples were then dried with a nitrogen gas stream. Samples were immersed in Nanostrip (Cyantek, Freemont, CA) for 1 min and then rinsed with deionized water and nitrogen dried.

Lipid preparation

The lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). These lipids included DiI, 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiIC18(3)); DNP-cap-DPPE, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[6-[(2,4-dinitrophenyl) amino]hexanoyl] (ammonium salt); DOPC, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; DPPE-PEG(2000)Biotin, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[biotinyl(polyethylene glycerol) (2000); POPC, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; and Rh-PE, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-lissamine rhodamine b sulfonyl. Lipids were dissolved separately and stored in chloroform at −20°C. Large unilamellar vesicles were prepared by extrusion (Mayer et al., 1986). Lipids were mixed at desired molar ratios and dried to a thin film under a stream of nitrogen gas; 5–10 μmol of total lipid was dried in each 13 × 100 mm glass test tube. The resulting films were placed under vacuum for 1 h to remove residual organic solvent. Dried lipid films were hydrated in HEPES (140 mM NaCl, 10 mM, pH 7.4, Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI), using vigorous cortex mixing to a final lipid concentration of 2 mM. After hydration of the small lamellar vesicle (SLV) suspension was subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles (liquid nitrogen/room temperature water) to distribute the lipid mixture. The SLV suspension was then extruded 10 times through two stacked 0.1 μm Nucleopore polycarbonate filters (Whatman, Clifton, NJ) using a high pressure 10 mL Thermobarrel Extruder (Northern Lipids, Vancouver, BC) to obtain uniform 100 nm SLV. Lipid vesicles were diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (0.138 M NaCl, 0.0027 M KCl, pH 7.4). Functionalized lipids bound to the pattern on the silicon substrate were reacted with a target analyte as illustrated in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Functionalized lipid and target analyte association

| Functionalized lipid | Target analyte |

|---|---|

| DNP-PE | Alexa 488-conjugated monoclonal mouse anti-DNP IgE |

| DPPE-PEG(2000)Biotin | Alexa 488-conjugated NeutrAvidin |

Anti-DNP IgE preparation

Monoclonal, mouse anti-DNP IgE molecules were obtained from the Baird research group at Cornell University and were stained with NHS-Alexa 488 dye (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The stock solution was diluted to 0.5 μg/ml, 7.4 pH.

Avidin preparation

The sample was prepared by adding DPPE-PEG(2000)Biotin lipids onto the patterned polymer surface. Alexa 488-conjugated NeutrAvidin (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) solution was diluted to 50 μg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline, 7.4 pH.

Target analyte and lipid application

A 20 μl drop of 2 mM lipid solution was placed on the Parylene-patterned substrate for 30 min, as illustrated in Fig. 1, second from bottom. Samples were incubated in 35-mm plastic Petri dishes (Fisher Chemicals, Pittsburgh, PA) for 10 min and rinsed in Milli-Q water. The Parylene was removed by mechanically peeling it from the substrate with tweezers under Milli-Q water (Fig. 1, bottom).

Microscopy and fluorescence photobleaching recovery measurements

Epifluorescence microscopy was performed with a Zeiss (Thornwood, NY) Axitron upright microscope, water immersion objectives, and Omega (Brattleboro, VT) Optical filter sets. Rhodamine and DiI fluorescent dyes were observed with a 510–590 nm excitation/590 nm emission filter set, and an Alexa 488 fluorescent dye was observed with a 450–490 nm excitation/520 nm emission filter set. Images were captured using a Spot CCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

Two-photon laser scanning microscopy was carried out using a lab-built multiphoton system composed of a modified BioRad (Hercules, CA) MRC600 scanner, Spectra-Physics (Mountain View, CA) Tsunami/Millennia (10 W) Ti:S laser and a modified Olympus AX-70 upright microscope. FPR measurements of DiI stained bilayers were implemented on the same system using two-photon excitation. Fluorescence was detected by turret-mounted a GaAsP photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu H7422, Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ). The output from the photomultiplier tube was spilt into an amplified analog signal for imaging and pulsed (TTL) output available for photon counting applications such as FPR. In this manner we can image the specimen and then accurately park the laser any point in the sample to carry out the diffusion measurement. Using a 60×/0.9 NA water immersion objective a spot (∼300 nm 1/e2 radius) was bleached in the bilayer by a 100 μs duration bleaching pulse at 900 nm (∼100 fs pulse width). Laser intensity was controlled by a resonance-dampened KD*P Pockels cell (Model 350-80BKLA, Conoptics, Danbury, CT), which provided short, high intensity bleaching pulses followed by a low intensity monitoring level. Fluorescence recovery was monitored for 80 ms using an 80 μs bin size by a lab-built acquisition system. Each FPR curve was averaged 50–100 times at the same location with a 250 ms delay between bleaching pulses. Data were fit to a model that assumes a single (Fickian) component, two-dimensional diffusion, and two-photon bleaching (Brown et al., 1999; Zipfel and Webb, 2001):

|

(1) |

An immobile fraction was not needed to fit the data. The bleaching parameter (β)and the diffusion coefficient (D) are determined using the Marquardt-Levenburg algorithm. Summation to n = 8 in the nonlinear fit is sufficient for convergence. The lateral two-photon 1/e2 beam radius (ωxy) for a 0.9 NA lens at 900 nm was calculated as (Zipfel and Webb, 2001):

|

(2) |

Equation 2 was determined from fits of the squared, diffraction-limited illumination point spread function (calculated following Richards and Wolf (1959)) for NA > 0.7.

RESULTS

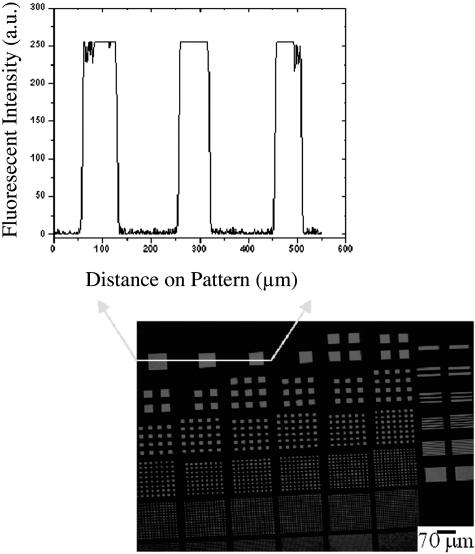

To determine whether the polymer lift-off method (Ilic and Craighead, 2000) could be used to pattern functionalized lipids on a micron scale, Paralyene C was applied to a silicon surface and the resulting film subjected to photolithography to produce square arrays composed of individual squares ranging from 1 to 76 μm in width (Fig. 2). After reactive ion etching, multilamellar vesicles of POPC labeled with rhodamine-tagged phosphoethanolamine were added to the substrate in a 99:1 POPC:Rh-PR ratio, and the Paralyene C film removed with tweezers. Microscopic analysis revealed a uniform pattern of fluorescent squares of the expected size. The ratio of fluorescence in lipid-containing regions versus background was >150:1 (Fig. 2, top). Indeed, because much of the observed fluorescence in the regions between squares was due to pixel “bleeding” in the CCD, the actual contrast was likely to be significantly higher.

FIGURE 2.

Fluorescence intensity image analysis of three squares of lipid in a 99:1 ratio of POPC:Rh-PE (2 mM). This demonstrates the low background signal that is present as a result of the protective polymer cover during biomaterial incubation.

Homogenous patterns were routinely achieved. There were several parameters that affected the uniformity of the final lipid pattern. Patterns were reliably formed with a Parylene thickness of 1 μm, and a resist thickness of 1.2 μm. RIE needed to occur long enough to remove the entire polymer from the exposed regions. Biomaterial incubation time needed 10 min for the lipids and 30 min for the antibodies or avidin in the second layers. Finally, lipid vesicles were always used immediately upon preparation, and the resulting bilayers examined within 48 h so as to achieve uniform results.

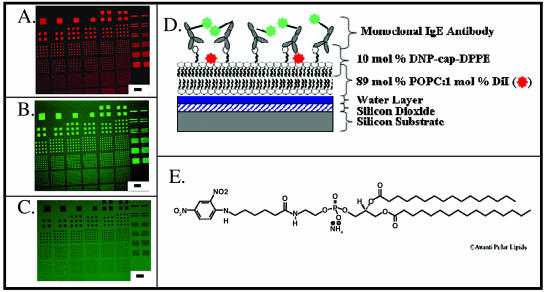

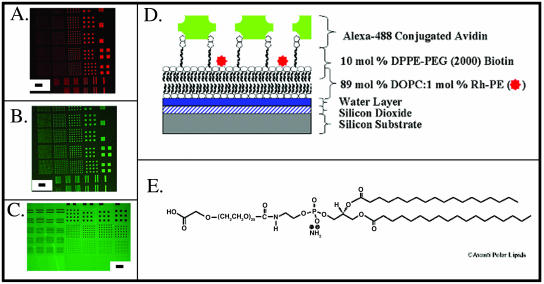

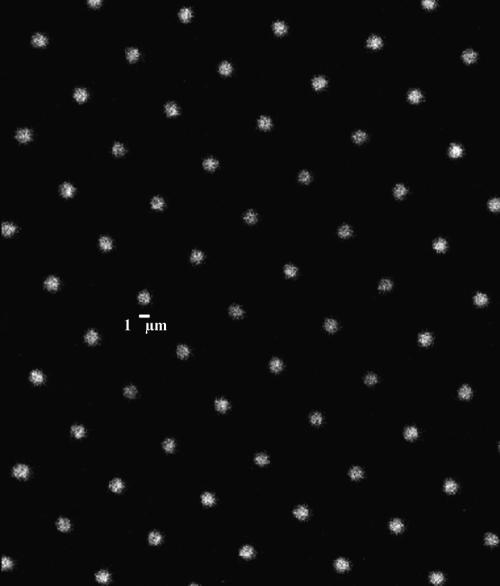

Spatial patterning of lipid-soluble ligands and/or receptors on a micro- or nanoscale would be extremely useful in a number of potential bioassays. Nevertheless, such assays require that the respective molecules (either ligands or receptors) retain their binding properties after incorporation into the patterned lipid bilayer. To examine the functionality of ligand/receptor interactions in the lipid bilayers described here, we prepared bilayers that contained either a model antigenic determinant (namely, dinitrophenyl) or a model ligand (namely, biotin) and tested the ability of these substances to bind their cognate receptors (anti-DNP antibodies on the one hand, or avidin on the other). In the first instance, DPPE was covalently linked to DNP, and the resulting compound incorporated into DiI-labeled POPC vesicles (POPC:DNP-cap-DPPE:DiI; 89:10:1 mol %). Patterned lipid bilayers were then prepared from these vesicles using the polymer lift-off method. As in the case of the POPC lipid vesicles, these formed arrays that were clearly visible under the fluorescence microscope (Fig. 3 A). This platform was considered a model for a cell surface carrying a single antigen (that is DNP). After transfer to aqueous medium, samples were incubated for 30 min with DNP-specific mouse antibodies tagged with Alexa 488, and then washed thoroughly. As shown in Fig. 3 B, strong Alexa 488 (green) fluorescence was seen in a pattern that corresponded precisely to the DiI-containing squares. When lipid bilayers were formed without DNP-conjugated lipids, antibody binding to the lipid features was below the background level associated with the silicon substrate itself (Fig. 3 C). These images demonstrate the significance of our antibody specificity: whereas antibodies are normally excluded from lipid bilayer patterns (Fig. 3 C), antibodies will bind with high affinity to their respective target molecules within the lipid bilayer. Relating this to normal physiological conditions, the antibodies will generally not bind to a cell lipid bilayer unless the appropriate epitope or target ligand is present. In the case of biotin, DOPC vesicles (DOPC: DPPE-PEG(2000)Biotin:Rh-PE; 89:10:1 mol %) containing biotinylated PEG were patterned on silicon as above (the use of PEG with biotin, as opposed to PE, reduced nonspecific binding in the subsequent step due to repulsive factors associated with the longer carbon chain). Resulting lipid bilayers were then reacted with Alexa 488-conjugated NeutrAvidin. As with DNP-antibody combinations, lipid bilayers containing biotin were labeled strongly with Alexa 488-conjugated NeutrAvidin (Fig. 4 B). When lipid bilayers were formed with (POPC:Rh-PE, 99:1) rather than the biotin-conjugated lipids, the NeutrAvidin bound at a lower level than the background binding level to the silicon substrate (Fig. 4 C). Fig. 4 D illustrates the layering of the molecules in this patterning process. These results clearly suggest that the lift-off process could serve as a model for patterning both lipids conjugated with antigens and biotin on a surface for subsequent binding of antibodies and biotinylated molecules, respectively. Fig. 5 shows an array of supported lipid bilayers created using this technique. The array is the fourth smallest array and can be located in Fig. 2 in the bottom row, third array from the left. This illustrates an example of the lipid bilayer patterns that can be attained using this technique.

FIGURE 3.

Fluorescence characterization of 1-μm-−76-μm-wide squares and 1-μm-−20-μm-wide lines of hapten-conjugated DOPC/Rh-PE-supported lipid bilayer membrane. (A) Membrane composed of 10 mol % DNP-cap-DPPE, 89% DOPC, and 1 mol % DiI. Scale bar is 70 μm. (B) The same pattern from Fig. 2, top, with NHS-Alexa 488-conjugated monoclonal IgE. (C) Control using 99% POPC and 1 mol % Rh-PE and NHS-Alexa 488-conjugated monoclonal IgE. (D) Schematic of the lipid layer illustrated in Fig. 3, A and B. (E) DNP-cap-DPPE structure (Avanti, 2001).

FIGURE 4.

Fluorescence characterization of 1-μm-−76-μm-wide squares and 1-μm-−20-μm-wide lines of DPPE-PEG(2000)Biotin supported lipid bilayer membrane. (A) Membrane composed of 10 mol % DPPE-PEG(2000)Biotin, 89 mol % DOPC, and 1 mol % Rh-PE. Scale bar is 95 μm. (B) The same pattern from Fig. 3 A with Alexa 488-conjugated avidin. (C) Control using 99% POPC and 1 mol % Rh-PE and Alexa 488-conjugated avidin. This image was taken with a 4× longer duration and an 8× greater gain than Fig. 4 B to accentuate the contrast of the background to the patterned regions. (D) Schematic of the lipid layer illustrated in Fig. 4, A and B. (E) DPPE-PEG(2000)Biotin structure (Avanti, 2001).

FIGURE 5.

This confocal image of 1.3 μm supported lipid bilayer patterns (POPC:DNP-cap-DPPE:DiI; 89:10:1 mol %) were attained using the polymer lift-off method.

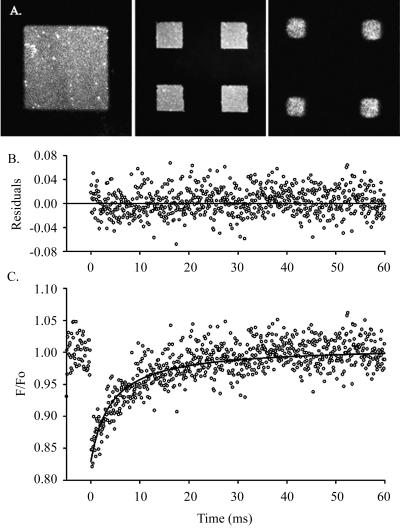

Neutron scattering and NMR analysis of artificial membranes on glass beads (Johnson et al., 1991; Bayerl and Bloom, 1990) have shown that lipid bilayers float on a thin film of water between the lipid and the solid substrate. We presumed that the same was true in this case. To examine whether the patterned lipids described here behaved as normal supported bilayers, we measured their fluid properties by FPR. FPR was used to measure the lateral diffusion coefficient of the lipid probe DiI in supported bilayers as evidence of normal bilayer mobility. On properly prepared supported POPC bilayer samples, we found an average value of 7.5 ± 1.2 μm2 s−1 (mean ± SD, n = 30) measured at 22°C. This value was obtained from 30 measurements on bilayer patches in different areas (70 × 70, 20 × 20, and 3 × 3 μm). There was no significant difference between average values for each patch size: 6.6 ± 0.9, 8.2 ± 0.9, and 7.8 ± 1.3 μm2 s−1 for the 70 × 70, 20 × 20, and 3 × 3 μm patches, respectively, 10 measurements on each patch size (Fig. 6). All values are from measurements made in the center of the bilayer patch to avoid edge effects (i.e., reduced dimensionally) that would produce slower apparent diffusion. For example, FPR measurements carried out 4.8 ± 1.4 μm from the patch edge yielded a diffusion coefficient of 1.7 ± 0.6 μm2 s−1 (n = 7).

FIGURE 6.

Multiphoton FPR measurements of DiI-stained supported lipid bilayer patches composed of 10 mol % DNP-cap-DPPE, 89% DOPC, and 1 mol % DiI. (A) Representative DiI-stained patches used in FPR measurements: 70-μm (left) and 20-μm (center), and 3-μm square (right). (B) Residuals from fit in C. (C) Data with fit. The excitation wavelength was 900 nm, bleaching pulse was 100 μs long at 5–8 mW average power during the pulse, and 0.5 mW while monitoring recovery. A 60×/0.9 NA objective was used producing a 1/e2 radius of 0.32 μm at 900 nm. Trace shown is an average of 120 bleaching pulses. Data were fit to a two-dimensional diffusion model and the returned diffusion coefficient was 6.8 μm2 s−1 for this curve.

Hovis and Boxer (2001) report values of 1–2 μm2 s−1 (measurement temperature not given) for their supported bilayer system composed of egg phosphatidylcholine and 1% Texas Red labeled DHPE, which is similar to other previous reports for bilayers on glass. Literature values for the DiI diffusion coefficient in cell membranes range from 0.8 to 3 μm2/s at 25°C, to 2–7 μm2/s at 37°C (Bloom and Webb, 1983, Fulbright et al., 1997). Measurements of DiI in polarized moving neutrophils at 24°C produced coefficients ranging from 1 to 7 μm2/s, depending on the position of the measurement (leading versus trailing edge) (Zipfel, unpublished). In artificial systems such as black lipid membranes and other types of multilaminar vesicles made of DPPC (measured at ∼40°C), the DiI diffusion coefficient ranged from 1 to 32 μm2/s, depending on the type of preparation and the amount of solvent trapped between the bilayers (Fahey and Webb, 1978). Our measurements in POPC-supported lipid bilayers presented here yield an ∼3× faster diffusion than found on an intact cell membrane, as might be expected due to the absence of dye/proteins interactions in the membrane. It is also ∼3× faster than previous values for bilayers on glass, which we believe, indicates fewer interactions with the substrate.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate a new technique for creating precise, micron-scale lipid bilayers on silicon substrates. Lipids patterned with this technique had fluid properties comparable to those of biological membranes, and their associated ligands retained functionality, allowing capture of other biomaterials from solution.

The success of this technique can be attributed, in large part, to the properties of Parylene itself. Intramolecular forces in the chlorobenzene backbone of the polymer create a strong film that is chemically inert to acid, base, and ketone exposure. At the same time, it binds weakly to the substrate and can be completely removed in a single, contiguous sheet. Its low permeability prevents binding to masked areas of the substrate, and allows multiple reagents, such as biotin, avidin, and antibodies, to be applied to the patterned regions before removal of the film. Pattern distortions and lack of coating uniformity, which sometimes result from other methods, are less likely with this method since the features themselves are applied with photolithography and reactive ion etching. Bilayer patches do tend to become more rounded as the size decreases, presumably from deformation of the corners during the Parylene lift-off step as well as line tension effects due to the higher proportion of edge lipids in the smaller patches. Finally, since the Parylene film covers unexposed areas, surfactant or blocking solutions are not required to prevent inappropriate binding in the unpatterned regions. Thus, Parylene can be used with both low or high concentration solutions and for long incubation times. With high concentration solutions, the application can be terminated after a short incubation period by rinsing without risk of redistributing the lipid to unpatterned regions. Blocking solutions can of course be added after Parylene removal to mask exposed areas of the substrate.

We were able to produce uniform protein or metal arrays of ∼700-nm-wide features as verified by SEM imaging (Orth, unpublished). A line intensity profile through a confocal microscopic image of the patterned lipid showed the smallest feature was ∼1 μm. Thus, this patterning technique was able to form patterns near the resolution limit of the photolithographic 10× stepper used in this experiment. Although this is near the photolithographic resolution limit, electron-beam lithography should be able to pattern at smaller resolution, potentially at or below 100 nm. Even at 1 μm, the feature size attained with this method is well below the average spot size on chip arrays (produced by commercial print technologies), which are highly variable and cover a diameter of roughly 100 μm. At the macro scale, conventional 96-well plate analysis is conducted in wells with an average surface area of 45 mm2.

This patterning technique provides an ideal platform for lipid bilayer mobility studies, cell surface receptor interrogation, and cell stimulation experimentation. The verification that soluble antibodies bound specifically to the patterned antigen suggests that membrane-bound receptors, such as antibodies, could bind to the patterned surface. The spatially controlled patterning to the 1 μm level offers the ability to target small domains on a cell surface. With the use of a small mol % of functional lipid molecules in the lipid composition, this technique may approach the level of single molecule binding and single ligand stimulation. Additionally, the demonstration that the biotin-conjugated lipid surface can bind avidin enables the patterning of biotinylated molecules to the surface. This extends this patterning technique to the extensive range of compounds that can be biotinylated, such as antibodies, DNA, other proteins, etc. Patterned lipids appear stable over several days to weeks of storage in solution. Standard FPR measurements confirm that our supported lipid bilayers have a lateral mobility equal to that expected from an independent bilayer undergoing minimal interactions with the substrate. Therefore, this can serve as a versatile model system for in vitro cell membrane experimentation where supported lipid bilayers can be tailored to consist of the functional molecules in patches down to 1 μm.

Acknowledgments

W.R.Z. and W.W.W. acknowledge support from grant P41-RR04224 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. We also thank several individuals at Cornell University for their insight and research assistance: Drs. Holowka and Baird for their guidance on forming supported lipid bilayers, Dr. Stephen W. Turner for his assistance with image analysis and pattern design, Dr. Ismail Hafez for assistance preparing the lipids, Dr. Erin Sheets for advice on how to prepare lipids, Min Wu for supplying the Alexa 488 monoclonal mouse anti-DNP antibody, and Jennifer Gaudioso for her manuscript review.

This work was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the Nanobiotechnology Center (NBTC, a Science and Technology Centers program of the National Science Foundation under Agreement ECS-9876771), the resources of the Cornell Nanofabrication Facility, and the United States Air Force. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

References

- Avanti Polar Lipid Catalogue. 2001. Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL.

- Axelrod, D., D. E. Koppel, J. Schlessinger, E. L. Elson, and W. W. Webb. 1976. Mobility measurement by analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery kinetics. Biophys. J. 16:1055–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayerl, T. M., and M. Bloom. 1990. Physical properties of single phospholipid bilayers adsorbed to micro glass beads. A new vesicular model system studied by H-2-nuclear magnetic resonance. Biophys. J. 58:357–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biebuyck, H. A., N. B. Larsen, E. Delemarche, and B. Michel. 1997. Lithography beyond light: Microcontact printing with monolayer resists. IBM J. Res. Develop. 41:159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, J. A., and W. W. Webb. 1983. Lipid diffusibility in the intact erythrocyte membrane. Biophys. J. 42:295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch, D. W., B. C. Wheeler, G. J. Brewer, and D. E. Leckband. 2000. Long-term maintenance of patterns of hippocampal pyramidal cells on substrates of polyethylene glycol and microstamped polylysine. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 47:290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E. B., E. S. Wu, W. Zipfel, and W. W. Webb. 1999. Measurement of molecular diffusion in solution by multiphoton fluorescence photobleaching recovery. Biophys. J. 77:2837–2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer, P. S., and S. G. Boxer. 1999. Formation and spreading of lipid bilayers on planar glass supports. J. Phys. Chem. 103:2554–2559. [Google Scholar]

- Cremer, P. S., J. T. Groves, L. A. Kung, and S. G. Boxer. 1999. Writing and erasing barriers to lateral mobility into fluid phospholipid bilayers. Langmuir. 15:3893–3896. [Google Scholar]

- Dontha, N., W. B. Nowall, and W. G. Kuhr. 1997. Generation of biotin/avidin/enzyme nanostructures with maskless photolithography. Anal. Chem. 69:2619–2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey, P. F., and W. W. Webb. 1978. Lateral diffusion in phospholipid bilayer membranes and multilamellar liquid crystals. Biochemistry. 17:3046–3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, D. 2002. Microarrayers on the Spot. Scientist. 16:42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fulbright, R. M., D. Axelrod, W. R. Dunham, and C. L. Marcelo. 1997. Fatty acid alteration and the lateral diffusion of lipids in the plasma membrane of keratinocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 233:128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, N. M. 1975. Avidin. Adv. Protein Chem. 29:85–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves, J. T., and S. G. Boxer. 1995. Electric field-induced concentration gradients in planar supported bilayers. Biophys. J. 69:1972–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves, J. T., and S. G. Boxer. 2002. Micropattern formation in supported lipid membranes. Acc. Chem. Res. 35:149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves, J. T., H. Ulman, and S. G. Boxer. 1997. Micropatterning fluid lipid bilayers on solid supports. Science. 275:651–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovis, J. S., and S. G. Boxer. 2000. Patterning barriers to lateral diffusion in supported lipid membranes by blotting and stamping. Langmuir. 16:894–897. [Google Scholar]

- Hovis, J. S., and S. G. Boxer. 2001. Patterning and composition arrays of supported lipid bilayers by microcontact printing. Langmuir. 17:3400–3405. [Google Scholar]

- Ilic, B., and H. G. Craighead. 2000. Topographical patterning of chemically sensitive biological materials using a polymer-based dry lift off. Biomed. Microdevices. 2:317–322. [Google Scholar]

- James, C. D., R. C. Davis, L. Kam, H. G. Craighead, M. Isaacson, J. N. Turner, and W. Shain. 1998. Patterned protein layers on solid substrates by thin stamp microcontact printing. Langmuir. 14:741–744. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. G., T. M. Bayerl, D. C. McDermott, G. W. Adam, A. R. Rennie, R. K. Thomas, and E. Sachmann. 1991. Structure of an adsorbed dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine bilayer measured with specular reflection of neutrons. Biophys. J. 59:289–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam, L., and S. G. Boxer. 2001. Cell adhesion to protein-micropatterned-supported lipid bilayer membranes. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 55:487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung, L. A., L. Kam, J. S. Hovis, and S. G. Boxer. 2000. Patterning hybrid surfaces of proteins and supported lipid bilayers. Langmuir. 16:6773–6776. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, L. D., M. J. Hope, and P. R. Cullis. 1986. Vesicles of various sizes produced by a rapid extrusion procedure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 858:161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth, R. N., M. Wu, D. A. Holowka, H. G. Craighead, and B. A. Baird. 2003a. Mast cell activation on patterned lipid bilayers of subcellular dimensions. Langmuir. 19:1599–1605. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, R., T. G. Clark, and H. G. Craighead. 2003b. Microcontact printing and avidin-biotin patterning methods for biosensor applications. Biomed. Microdevices. 5:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, B., and E. Wolf. 1959. Electromagnetic diffraction in the optical systems II. Structure of the image field in aplanatic system. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser A. 253:358–379. [Google Scholar]

- Sackman, E. 1996. Supported membranes: scientific and practical applications. Science. 271:43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage, D., G. Mattson, S. Desai, G. Niedlander, S. Morgensen, and E. Conklin. 1994. Avidin-Biotin Chemistry: A Handbook. Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL.

- Tien, H. T., and Z. Salamon. 1990. Self-assembling bilayer lipid membranes on solid support. Biotechnol. Appl. Bioc. 12:478–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y., and G. M. Whitesides. 1998. Soft lithography. Agnew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37:550–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P., T. Deng, D. Zhao, P. Feng, D. Pine, D. F. Chmelka, G. M. Whitesides, and G. D. Stucky. 1998. Hierarchically ordered oxides. Science. 282:2244–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel, W. R., and W. W. Webb. 2001. In vivo diffusion measurements using multiphoton excited fluorescence photobleaching recovery (MPFPR) and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (MPFCS). In Methods in Cellular Imaging. A. Periasamy, editor. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 216–235.

- Zviman, M., and H. T. Tien. 1991. Formation of a bilayer lipid membrane on rigid supports: an approach to BLM-based biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 6:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]