Abstract

Organisms within the Hardjo serovar of Leptospira species are harbored in cattle throughout the world, causing abortion in pregnant animals as well as being shed in the urine, thereby providing sources of zoonotic infection for humans. We recently showed that sterile immunity in vaccinated cattle is associated with induction of a type 1 (Th1) cell-mediated immune response. Here naïve and previously vaccinated pregnant cattle were challenged with a virulent strain of serovar Hardjo and subsequently evaluated for expression of a type 1 immune response. Lymphocytes that responded in a recall response to antigen by undergoing blast transformation were evident in cultures of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from vaccinated cattle throughout the postchallenge test period while those from naïve cattle were evident at one time point only. Nevertheless, beginning at 2 weeks after challenge, gamma interferon (IFN-γ) was measured in supernatants of antigen-stimulated PBMC cultures from nonvaccinated animals although the amount produced was always less than that in cultures of PBMC from vaccinated animals. IFN-γ+ cells were also evident in antigen-stimulated cultures of PBMC from vaccinated but not from nonvaccinated animals throughout the postchallenge period. The IFN-γ+ cells included CD4+ and WC1+ γδ T cells, and a similar proportion of these two subpopulations were found among the dividing cells in antigen-stimulated cultures as ascertained by carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester loading. Finally, while naïve and vaccinated animals had similar levels of antigen-specific immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) following challenge, vaccinated animals had twofold-more IgG2. In conclusion, while infection may induce a type 1 response we suggest that it is too weak to prevent establishment of chronic infection.

The spirochete bacterium Leptospira spp. serovar Hardjo is a pathogen that causes disease in cattle and humans throughout the world. Infected cattle are the maintenance host for Leptospira borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo (subtype hardjobovis) (20) and Leptospira interrogans serovar Hardjo (subtype hardjo prajitno) and have a variety of clinical illnesses including abortion, infertility, and mastitis, while their calves may be stillborn, weak, or clinically normal but infected (see references 14-16, 21, 25, and 26). Infection is commonly transmitted by contact of urine or reproductive fluids from infected animals with the mucosal membranes of uninfected humans or animals, either directly or through fomites. Zoonotic infection of humans with leptospires including those of the serovar Hardjo group (1) poses a significant public health problem of increasing concern since leptospirosis in humans may be fatal due to involvement of multiple organs including liver, lungs, kidney, and brain (see reference 23).

It was previously thought that protective immunity against leptospirosis was sufficiently provided by antibodies (20), since anti-leptospiral lipopolysaccharide (LPS) antibodies have been shown elsewhere to provide passive immunity in some animal models, protecting against a number of strains and species of Leptospira (30, 36). However, Bolin et al. (4, 6) showed that high titers of anti-LPS antibody induced by conventional leptospiral vaccines may not be protective against L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo. Moreover, recently developed vaccines that protect against L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo including renal colonization and urinary shedding (7, 41) and protect against transplacental infection of the fetus (D. Alt, R. Hornsby, and C. A. Bolin, submitted for publication) induce a type 1, or cell-mediated, immune response (18, 41).

Cell-mediated or type 1 immunity is generally regarded as including production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and generation of cytotoxic CD8 T cells. While cytotoxic CD8 T cells and IFN-γ are both particularly important in control or clearance of infections with viruses and intracellular bacteria and protozoa, IFN-γ may also have a role in protection against extracellular microbes through its ability to activate macrophages and promote production of immunoglobulin G2 (IgG2) classes of antibodies, as has been suggested previously for immunity to extracellular stages of the protozoan parasite Babesia bigemina (9). While bovine IgG2 and IgG1 are both able to fix complement, which may be an important effector mechanism for control of leptospires in its own right, bovine IgG2 antibodies also act as opsonins (37), thereby potentially increasing the number of leptospires phagocytosed. Moreover, although leptospires are not considered to be intracellular pathogens that survive phagocytosis, IFN-γ activation of macrophages may increase the efficiency of killing. For example, Candida albicans, largely an extracellular organism that also targets the kidney, suppresses macrophage nitric oxide production through a soluble factor (10), and thus, IFN-γ is required for optimal production of nitric oxide by macrophages in vivo during a Candida infection (31).

Because of the increasing incidence of infection in cattle and the zoonotic nature of human infections, it was of interest to examine the immune response of naïve cattle following challenge with L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo during the periparturient period. This experimental design was chosen because of the effects that L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo infections have on events associated with pregnancy and transmission of the infection to the calves. Since natural infection is chronic in cattle, it was of interest to determine if it established itself due to the absence of a type 1 immune response or an insufficient one. While many bacterial infections induce type 1 immune responses, some are associated with induction of a type 2 response, such as that which occurs in patients with lepromatous leprosy (48), while other infections such as those with Brucella abortus may initially induce a type 1 response but after the first few weeks of infection show a hiatus of IFN-γ production (40). Here the cellular immune response of nonvaccinated cattle following challenge was compared with that of cattle that had been immunized prior to challenge with a vaccine protective against L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo infections (7) and which induces a type 1 cell-mediated immune response (41). Production of IFN-γ by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in response to antigen was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and since any of the major T-cell populations including αβ CD4, αβ CD8, or γδ T cells may produce IFN-γ, two-color flow cytometry was used to determine the contribution by individual T-cell subpopulations. Generation of antigen-specific IgG1 and IgG2 antibodies in sera was also evaluated since the lack of IgG2 is correlated with a type 2 immune response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cattle.

Heifers 12 to 15 months of age that lacked detectable serum antibodies against L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo as determined by the microscopic agglutination test (12) were housed at the National Animal Disease Center in Ames, Iowa. One group of cattle was not vaccinated (n = 7), while a second group was vaccinated with a commercial monovalent serovar Hardjo vaccine (n = 16) (Spirovac; CSL Ltd., Parkville, Australia). It is a killed whole-cell vaccine composed of a bovine isolate of L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo and aluminum hydroxide and is given as two doses subcutaneously 4 weeks apart. All cattle were bred naturally, 2 to 3 months following vaccination of the vaccine group, and then challenged with L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo strain 203 conjunctivally and vaginally (1 ml of phosphate buffered saline [PBS] containing 106 serovar Hardjo bacteria) 4 to 5 months after initiation of pregnancy. Cattle were evaluated for infection with serovar Hardjo following challenge by culture (5) and a direct immunofluorescence test to detect shedding of leptospires in urine (17, 29). Animals were kept in the study until they calved. All animal use complied with the relevant federal guidelines and institutional policies and was approved by the institutional animal care and use committee, and animals were held in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved facility.

Isolation of PBMC.

Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein into acid citrate dextrose and processed at the University of Massachusetts 24 h after collection. PBMC were isolated at that time over Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) density gradients according to standard methods (22). PBMC were washed three times with Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 0.5 U of heparin/ml and suspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10 μg of gentamicin/ml.

Proliferation assays.

For the proliferation assays, 5 × 105 PBMC were aliquoted into 96-well flat-bottomed microtiter plates along with medium only, concanavalin A (ConA) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml, or antigen. Antigen was sonicated whole bacterial cells from L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo clone RZ33 used at a final concentration of 0.5 μg of protein/ml in medium. This concentration was established in pilot studies evaluating 50 to 0.005 μg/ml. The sonicate was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until use, and a single batch of antigen preparation was used throughout. A total culture volume of 0.2 ml/well was employed. All cultures were set up in quadruplicate and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 5 days, at which time 0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine was added to each well for an additional 12 h. Incorporation of [3H]thymidine was determined by liquid scintillation counting, and results were expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) of the counts per minute of [3H]thymidine incorporated into DNA in quadruplicate cultures. Cell division was assessed by carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) loading as described previously (47). Briefly, PBMC at 2 × 107 cells/ml in Hanks' balanced salt solution were mixed with equal volumes of CFSE at 3 μM solubilized with 2.5 mM Pluronic F127 and incubated for 10 min at 37°C following which heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum was added to stop the reaction. Cells were analyzed for cell divisions following culture by assessing the CFSE content with flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson, Sunnyvale, Calif.) and WinMDI flow cytometry analysis software. With each cell division the fluorescence intensity decreases approximately twofold. Cells were stained by indirect immunofluorescence after culture to assess T-cell subpopulations by using monoclonal antibody (MAb) IL-A12 to identify CD4 (2), MAb MMCA837G to identify CD8 (Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom), MAb GB21A to identify the δ chain of the γδ T-cell receptor (TCR) (VMRD, Pullman, Wash.), and the IgG2a isolate of IL-A29 to evaluate WC1 (11). This was followed by incubation with goat anti-mouse phycoerythrin-conjugated isotype-specific secondary antibody (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, Ala.).

IFN-γ production by ELISA.

For cytokine evaluation, 5 × 106 PBMC/well were aliquoted into a 24-well tissue culture plate in the presence of medium or the L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo antigen as described above with a total volume of 2 ml/well and incubated for 1 to 7 days. At the end of the culture period (which was 5 days unless stated otherwise in the results) PBMC were resuspended and allowed to settle and supernatants were collected. IFN-γ in culture supernatants was measured by ELISA with a commercial kit (Biosource, Camarillo, Calif.). The amount of IFN-γ was compared to a standard curve generated with recombinant bovine IFN-γ (kindly provided by CSL Australia, Melbourne, Australia).

Flow cytometry to detect cytokine-producing cells.

To evaluate production of IFN-γ by flow cytometry, cells were cultured as for the IFN-γ ELISA in medium only or with antigen for 7 days unless stated otherwise in the results. They were restimulated during the last 4 h of culture with monensin (2 μM) by addition of phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin (at an 0.5-μg/ml final concentration each) as is conventional for these assays (51). Cells were stained for surface markers of T-cell subpopulations as described above, except that the secondary antibodies were conjugated to fluorescein. Following this, they were washed, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, and permeabilized by incubation at 4°C overnight in a solution of 20% horse serum, 0.1% saponin, and 0.1% sodium azide in PBS. Intracellular immunostaining was performed with anti-bovine IFN-γ MAb 7B6, kindly provided by J.-J. Letesson (54), and goat anti-mouse phycoerythrin-conjugated isotype-specific secondary antibody (Southern Biotechnology). Inclusion of isotype-matched primary control MAb (Southern Biotechnology) was found not to increase background fluorescence. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Antibody titers.

A capture ELISA was used to measure antigen-specific IgG1 and IgG2 antibody levels in the serum. Sonicated antigen as described for the cellular assays was diluted in 0.1 M Na2HPO4 (pH 9.0) and applied as a coating onto ELISA plates at 5 μg/ml by incubation at 4°C overnight. Plates were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) and blocked at room temperature for 3 h with 200 μl of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Following washing, 100 μl of serum diluted 100- and 1,000-fold with 1% BSA in PBST was added to plates, incubated at room temperature for 2 h, and washed. Mouse anti-bovine IgG1 or IgG2 conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1 μg/ml) (Serotec) was diluted with 1% BSA in PBST, added to plates, incubated at room temperature for 45 min, and washed. The substrate added was 0.3 mg of 2,2′-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) per ml in 0.1 M citric acid (pH 4.35); the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 25 min, and the reaction was stopped by addition of 50 μl of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate/well. Optical density at 405 nm was determined, and dilutions of serum that yielded a reading in the linear range of the assay were used. Pilot experiments to establish sensitivity and specificity of the assay evaluated known positive and negative sera over a broad range of dilutions.

Statistical analyses.

Data are presented as means and SEM for all animals in the treatment groups unless stated otherwise for a particular assay and except for data from 4 months postchallenge, when there were only four animals remaining in the nonvaccinated group and two in the vaccinated group (the others having given birth). Treatment groups were compared for significant differences by a one-way analysis of variance, and the Student t test was used subsequently to compare responses between groups. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

In vitro response by PBMC following challenge.

The most significant clinical effects of Leptospira infection in cattle concern pregnancy and the health of calves born to infected cows. Aborted material as well as urine from infected dams and calves provides sources for zoonotic infections of humans. Therefore, pregnant cattle (both naïve and vaccinated) were challenged with L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo and then evaluated for type 1 immunity since this correlates with protection against serovar Hardjo organisms. After challenge, Leptospira organisms were detected in the urine of all the nonvaccinated animals but not in that from previously vaccinated cattle by immunofluorescence and culture assays.

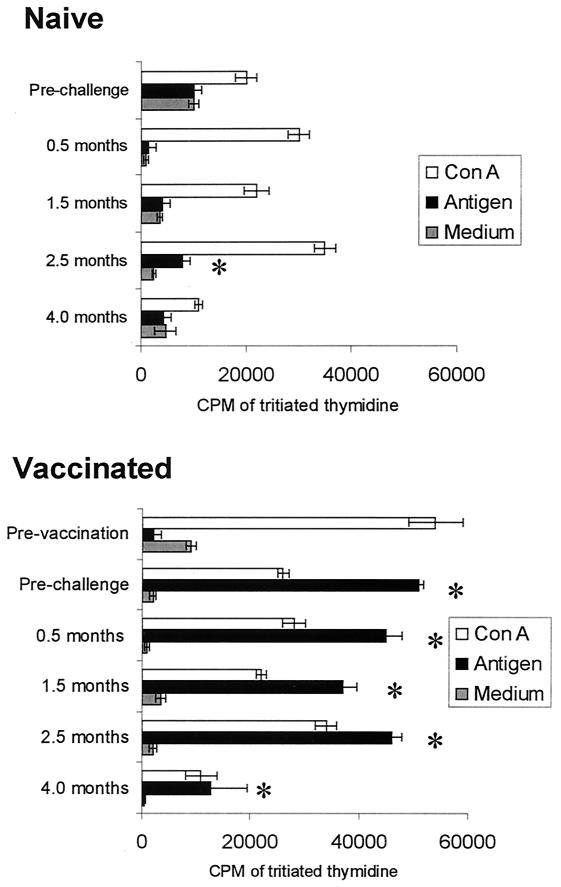

When lymphocyte blastogenesis was evaluated following challenge, PBMC from nonvaccinated-infected cattle exhibited significant antigen-specific responses at 2.5 months postchallenge only (Fig. 1, top) while PBMC from vaccinated-challenged cattle continued to do so at all four times evaluated postchallenge, as they had following vaccination prior to challenge (Fig. 1, bottom). Moreover, the responses with PBMC from vaccinated cattle cultured with antigen were consistently higher than those with PBMC from the nonvaccinated-infected cattle. The ConA mitogenic responses of PBMC from the two groups of cattle were similar to one another at all times, indicating that PBMC from nonvaccinated-infected cattle were competent to proliferate if an appropriate stimulus was provided (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

The means and SEM of proliferative responses by PBMC from nonvaccinated (naïve) or vaccinated cattle. The times indicated are for samples taken prior to vaccination for that group or 3 weeks prior to challenge or at the number of months indicated postchallenge for both groups. For vaccinated cattle, the prechallenge sampling was after vaccination. There were 7 nonvaccinated animals and 16 vaccinated at all times except at 4 months postchallenge when only 4 nonvaccinated and 2 vaccinated animals remained in the study. PBMC were cultured with medium, L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo antigen, or a suboptimal level of ConA included as a positive control. An asterisk indicates a significant response to antigen relative to medium cultures (P ≤ 0.05).

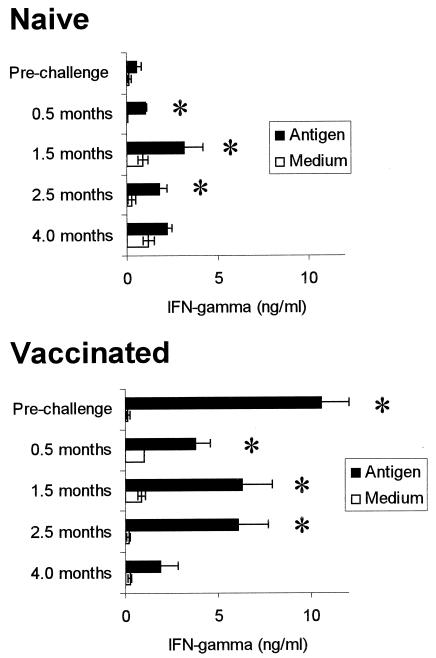

To determine whether the antigen-responsive cells were type 1 (Th1) or type 0 (Th0) versus type 2 (Th2), supernatants from PBMC cultures were evaluated for IFN-γ by ELISA. Elsewhere it has been shown that cells from these nonvaccinated animals with no previous exposure to leptospirosis, based on the absence of a detectable antibody titer, did not produce more than 650 pg of IFN-γ/ml in similar cultures of PBMC stimulated with antigen except in 1 of 44 trials conducted (41). By comparison, IFN-γ production by PBMC in Leptospira antigen-stimulated cultures was significantly higher than that in medium cultures for both naïve and vaccinated cattle following challenge, as it had been following vaccination prior to challenge (Fig. 2). While there was an increase in IFN-γ measured between 0.5 month and 1.5 months postinfection for both groups, there was no significant difference in the amount produced in the antigen-stimulated cultures between 1.5 and 2.5 months for naïve animals (P < 0.05), nor among the responses at 0.5, 1.5, or 2.5 months for the vaccinated group. This suggested that the maximal response to infection had occurred by at least 1.5 months postchallenge. Also, the response by the vaccinated cattle was not increased following challenge, indicating that the challenge did not boost the response.

FIG. 2.

IFN-γ in culture supernatants of PBMC evaluated by ELISA. The times indicated are for samples taken 3 weeks prior to challenge or at the number of months indicated postchallenge. For vaccinated cattle, the prechallenge sampling was after vaccination. The mean levels of IFN-γ produced with SEM are shown for medium and antigen cultures for PBMC from nonvaccinated (naïve) animals or vaccinated animals. There were 7 nonvaccinated animals and 16 vaccinated at all times except at 4 months postchallenge when only 4 nonvaccinated and 2 vaccinated animals remained in the study. An asterisk indicates a significant response to antigen relative to medium cultures (P ≤ 0.05).

Since IFN-γ production by PBMC from vaccinated cattle was greater than that by PBMC from the nonvaccinated cattle at all times evaluated postchallenge, IFN-γ levels in culture supernatants were assessed by ELISA after 1 to 5 days of culture to ensure that maximal production was not occurring earlier in cultures of PBMC from the nonvaccinates than in those from the vaccinates. The levels of IFN-γ in antigen-stimulated cultures were maximal by day 4 of culture for samples from either group in one trial with a decline at 5 days in one of four cultures (data not shown). When this was repeated at a later time point in the infection with samples from another four animals, the IFN-γ responses increased throughout the 5-day evaluation period for all cultures (data not shown). Thus, although differences in kinetics of response occurred between sampling dates, perhaps reflecting a change in the frequency of responsive cells in PBMC, the samples from the naïve and vaccinated animals had similar kinetics.

Evaluation of the IFN-γ-producing cells by flow cytometry.

Intracellular flow cytometry was employed to determine the proportion of IFN-γ-producing cells that participated in the response. A substantial proportion of PBMC from vaccinated animals were IFN-γ+ in response to culture with antigen throughout the postchallenge period (Fig. 3) as occurred postvaccination (see reference 41), but such cells were not as readily detectable with PBMC from nonvaccinated animals following challenge. Out of 21 samplings from the nonvaccinated animals, only three times was an antigen-specific response detected (14%). In contrast, it was detected in 30 out of 35 cultures of PBMC from vaccinated cattle in the postchallenge period (86%). Thus, we postulated either that the antigen-induced IFN-γ measured in the supernatants of PBMC cultures from the naïve-challenged animals was produced by a large proportion of cells in very small quantities per cell such that those cells could not be distinguished from background levels by flow cytometric analyses or that the peak production of IFN-γ was occurring earlier in cultures of PBMC from the nonvaccinated-infected animals than it was in cultures of PBMC from the vaccinated animals. If the latter occurred, we might fail to detect the IFN-γ-producing cells because we were evaluating them too late (following 7 days of culture with antigen). To address this latter possibility, immunofluorescence staining for intracellular IFN-γ was conducted after shorter in vitro culture times. There was no greater percentage of IFN-γ-producing cells in antigen-stimulated cultures of PBMC from four nonvaccinated animals evaluated at either 3 or 5 days of culture than in those at 7 days of culture (data not shown).

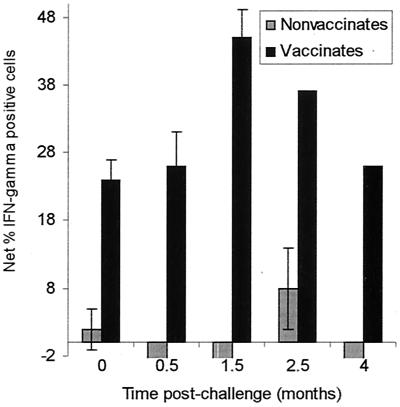

FIG. 3.

Flow cytometric analysis (one-color) was used to determine the percentage of IFN-γ-producing cells in response to antigen stimulation in cultures of PBMC from nonvaccinated or vaccinated cattle at the times indicated following challenge. The mean percentages of IFN-γ+ cells in cultures with antigen minus the percentage in control medium cultures (i.e., net IFN-γ+ cells) are shown with the SEM for 7 nonvaccinated and 16 vaccinated animals at 0.5 and 1.5 months postchallenge while at 2.5 months three nonvaccinated animals and one control vaccinated animal were evaluated and at 4.0 months only four nonvaccinated and two vaccinated animals were remaining in the study.

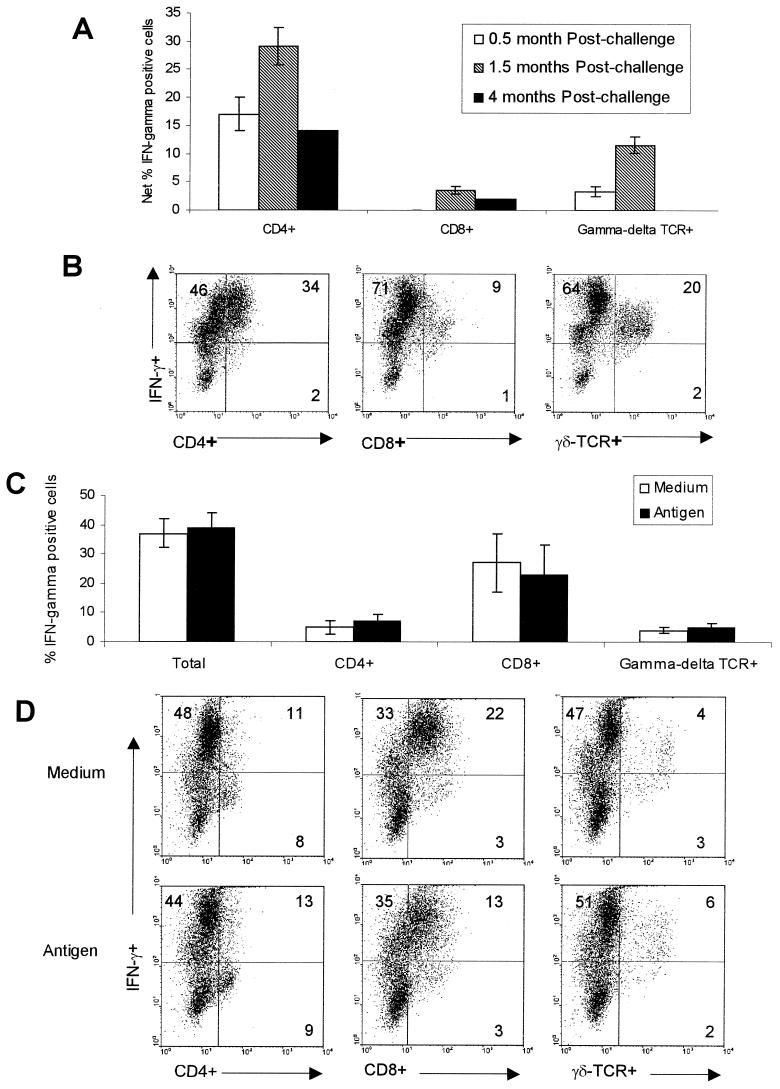

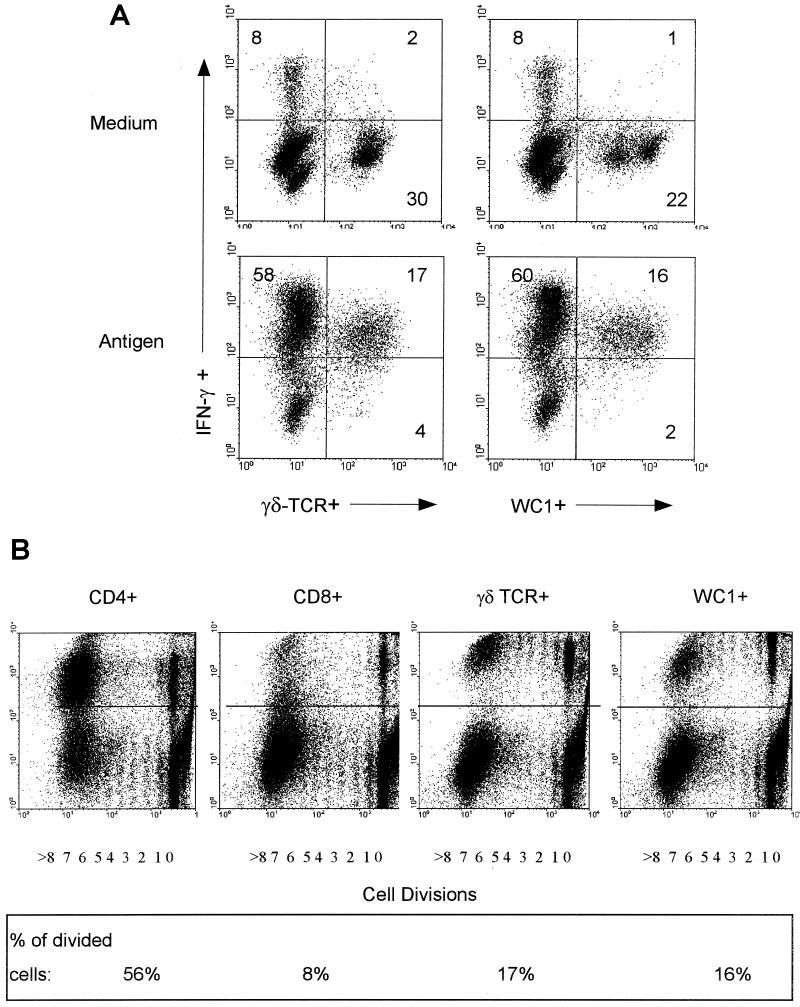

Two-color flow cytometry was employed to identify the subpopulations of T cells that produce IFN-γ in response to antigen after subtracting the percentages in medium control cultures (Fig. 4A). It was found that the majority of the IFN-γ-producing cells in 7-day cultures of PBMC from vaccinated-challenged cattle were CD4+ T lymphocytes at the three times evaluated with a contribution by γδ TCR+ T cells at two times. Some CD8+ T lymphocytes were also IFN-γ+ at two times, but they generally constituted a smaller percentage of the total IFN-γ+ cells. An example of flow cytometric results for PBMC from an individually vaccinated animal following challenge in response to culture with antigen is shown in Fig. 4B.

FIG.4.

(A) PBMC from vaccinated cattle cultured with L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo antigen were analyzed by two-color immunofluorescence for intracellular IFN-γ and cell surface phenotypic markers by flow cytometry. The means and SEM shown for 0.5 month (n = 16) and 1.5 months (n = 16) and the average at 4 months (n = 2) postchallenge for the net IFN-γ+ cells (percentage in antigen-stimulated cultures minus the percentage in medium control cultures) for the group of animals are shown. (B) An example of analysis from one vaccinated animal is shown in the form of dot plots of flow cytometric analysis in antigen-stimulated cultures by two-color immunofluorescence for CD4, CD8, and total γδ T cells in conjunction with IFN-γ. (C) Total IFN-γ+ cells in PBMC isolated from nonvaccinated cattle 4 months after challenge and cultured with medium or antigen. The mean percentages and SEM are shown (n = 4). (D) An example of analysis for PBMC from a nonvaccinated-infected animal cultured with medium or antigen is shown.

At 4 months postchallenge there was a high proportion of IFN-γ-producing cells in medium (mean ± SEM, 40% ± 21%) and antigen-stimulated cultures of PBMC from nonvaccinated animals (mean ± SEM, 36% ± 11%), and they were identified as CD8+ T cells in both cultures with and cultures without antigen (Fig. 4C). An example of a flow cytometric analysis of these non-antigen-specific responses is shown in Fig. 4D. While most of the γδ T cells were also producing IFN-γ in the example shown (Fig. 4D), they constituted a small percentage of total cells within the PBMC cultures. The CD4 T cells were largely IFN-γ−. While we also occasionally observed high responses in the medium cultures of PBMC from the vaccinated animal throughout the study period, there was still an overall net increase in the percentage in the antigen-stimulated cultures (Fig. 3).

WC1+ γδ T cells respond to antigen.

γδ T cells in ruminants can be divided into subpopulations by expression of the γδ lineage-specific cell surface molecule WC1. A large proportion of peripheral blood γδ T cells may express WC1 (3, 11, 49), but in other tissues such as the spleen this is not the case (55). Since the γδ T cells constituted a proportion of the IFN-γ+ cells in the antigen-stimulated cultures of PBMC from vaccinated animals, the expression of WC1 was also evaluated. Virtually all the WC1+ cells were IFN-γ+ after antigenic stimulation and culture for 7 days (Fig. 5A has an example). Although there was no statistically significant difference, there was a slightly higher net percentage (percentage in antigen-stimulated culture minus percentage in medium cultures) of IFN-γ+ cells that were δ-TCR+ (15.1% ± 1.5% [SEM], n = 3) than were WC1+ in the same cultures (13.5% ± 1.5% [SEM]).

FIG. 5.

An example of two-color immunofluorescence for IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells as assessed by δ TCR or WC1 expression following culture with medium or antigen as indicated (A) and cell division by PBMC in antigen-stimulated cultures as assessed by CFSE loading of cells and surface staining for CD4, CD8, WC1, or δ TCR (B). Positive cells for phenotypic surface markers are above the horizontal line indicated at log10 2.1 on the dot plots, while the number of cell divisions undergone as ascertained by diminishing CFSE intensity is shown on the abscissa and indicated as 0 to 8 divisions. The percentage that a phenotypic population represents of the divided cell population is indicated in the box at the bottom of panel B.

By using CFSE-loaded cells and two-color immunofluorescence staining for surface markers, it was also possible to determine the phenotype of dividing cells in antigen-stimulated cultures of PBMC from vaccinated cattle (Fig. 5B). They were comprised mainly of CD4 and γδ T cells, with each population having a substantial proportion of divided cells by 7 days of culture. Moreover, the majority (94%) of the dividing γδ T cells were WC1+, corroborating the results found by intracellular IFN-γ staining. There was proliferation of some CD8 T cells, but this included the CD8lo cells (immunofluorescence around log10 2.2), which may partly or largely represent γδ T cells, since we have found that γδ T cells that are CD8+ generally express lower levels of CD8 while the CD8hi (immunofluorescence around log10 3.5) cells are δ-TCR− (data not shown). This antigen-driven expansion of T cells also explains the results in Fig. 4B that showed that a high percentage of cells were IFN-γ+ in 7-day PBMC cultures. A time course experiment confirmed this expansion of responsive cells. It indicated that the net proportions of viable PBMC that were IFN-γ+ (responses in medium cultures were subtracted from those in antigen-stimulated cultures) were 2% after 3 days of culture, 8% after 4 days, 29% after 5 days, and 46% at 7 days for a representative vaccinated animal.

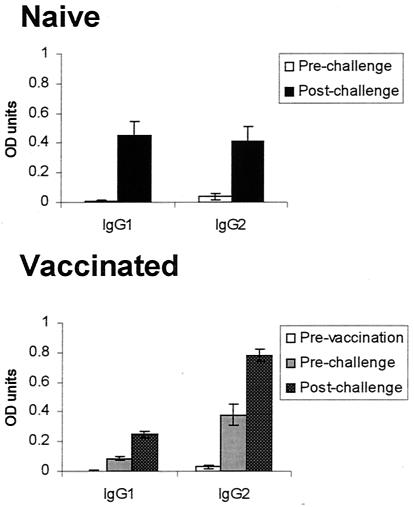

Antibody isotype responses to antigen.

Prior to inclusion in the study, all animals were negative for antibodies to leptospires (indicated as “prechallenge” for nonvaccinated animals and “prevaccination” for vaccinated ones [Fig. 6 ]). The amount of IgG1 and IgG2 antigen-specific antibody measured in the serum of challenged animals at 2 months after challenge was greater for both groups relative to prechallenge-prevaccination levels, and the vaccinated and nonvaccinated animals had similar levels of antigen-specific IgG1, representing an increase from postvaccination levels for the vaccine group (Fig. 6). There was about twofold more antigen-specific IgG2 in sera from vaccinated-challenged animals than was found in that of the nonvaccinated-challenged animals postchallenge, and there was also an increase from the postvaccination-prechallenge levels. The presence of antigen-specific IgG2 supports an IFN-γ response in both groups of animals.

FIG. 6.

Antibodies of the IgG1 or IgG2 subclasses specific for antigen as measured by ELISA are shown for prechallenge and postchallenge for the nonvaccinated group and prevaccination, postvaccination-prechallenge, and postvaccination-postchallenge for the vaccinated group. The means and SEM for 7 nonvaccinated and 16 vaccinated animals are shown. The sera were evaluated at two dilutions, and the results that were within the linear range of the assay for all samples (1:1,000) are indicated here. The prechallenge sera were not positive at any concentration tested when compared to a known negative control. OD, optical density.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to examine the immune response of naïve and vaccinated cattle following challenge with L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo. The work builds upon our published work showing that protective immunity correlated with establishment of a type 1 IFN-γ-based immune response as determined by in vitro analyses of responses by PBMC (41). While a crude bacterial sonicate containing bacterial LPS and nucleic acids was used as the antigen in the in vitro studies to demonstrate this, antigen-specific responses never occurred in a total of 27 nonvaccinated animals evaluated in two studies (41; R. Brown et al., unpublished data). Moreover, the ability of the antigen sonicate to stimulate responses in vitro was eliminated when it was digested with proteases (S. Blumerman, unpublished data). Together these data indicated that the response was to protein components and not to potentially mitogenic components such as the LPS. The protective immune response induced by vaccination is considered to be a type 1 immune response since IL-4 was never detected (41) and although both IgG1 and IgG2 antibodies to the antigen were induced as shown here, bovine T-cell clones that produce much greater quantities of IFN-γ than of interleukin-4 as assessed by RNA transcripts have been shown elsewhere to help B cells make both IgG1 and IgG2 antibodies (9).

Our findings here indicated that, as early as 2 weeks after challenge of naïve cattle, IFN-γ production by PBMC in response to antigen was measured and this response was sustained for several months. While some of the IFN-γ may be attributable to NK cell responses as described recently for calves vaccinated with Mycobacterium bovis BCG (28), IgG2 antigen-specific antibodies were also produced following challenge of the naïve animals, indicating development of an adaptive immune response by Th1 cells (19). Although the amount of IFN-γ, the level of IgG2 antibodies, the proliferative response by PBMC to antigen, and the proportion of IFN-γ-producing cells as measured by flow cytometry were all lower than those found for vaccinated-challenged animals, these results nevertheless suggest that infection induces a weak type 1 or type 0 immune response. Since protection of nonpregnant animals against infection (7) as well as protection of pregnant cattle (this study) and their fetuses (Alt et al., submitted) correlates with induction of a type 1 immune response, it is reasonable to postulate that natural infection may also result in partial protection against subsequent infections. However, it is also likely that the overall weaker response induced by infection impacts on the epidemiology of the disease in livestock and zoonotic infection of humans, since it fails to prevent persistent infection and shedding from kidneys and genital tracts of infected cattle. The lack of measurement of a more vigorous response by infected cattle was not likely to be a result of insufficient time following challenge for analysis, since in a recent study we were able to detect IFN-γ-producing cells by flow cytometry by 30 days following completion of vaccination (R. Brown et al., unpublished data).

Our inability to measure antigen-specific IFN-γ-producing cells in cultures of PBMC from the nonvaccinated animals by flow cytometry when IFN-γ was clearly being produced as measured by ELISA (e.g., at month 1.5) is consistent with previous observations. IFN-γ production measured by ELISA has been noted as a more sensitive measure of recall responses by T cells in vitro than of delayed-type hypersensitivity in vivo (54), and intracellular flow cytometry detection of IFN-γ-producing cells has been noted by others as being relatively insensitive compared to assays such as limiting dilution to determine the frequency of antigen-responsive cells in a population (53). Thus, while very useful for dissecting a vigorous immune response, it may be less useful as a method of detection or analysis of weaker ones. In fact, without the restimulation with phorbol myristate acetate-ionomycin for the final 4 h of the culture, which is a standard component of this method (51), the amount of IFN-γ per cell is decreased about 10-fold (R. Brown, unpublished data).

Although there was never a vigorous antigen-specific increase in IFN-γ+ cells in cultures of PBMC from the nonvaccinated-infected animals, there were occasionally IFN-γ+ cells in the medium control cultures with similar percentages in the corresponding antigen-containing cultures. These were predominately CD8+ cells. These results contrasted with detection of IFN-γ+ cells in PBMC cultures from vaccinated animals which were consistent with a recall memory response to antigen and predominately WC1+ γδ T cells and CD4 T cells. We have also recently observed high levels of IFN-γ+-CD8+ cells in medium cultures of PBMC from 6- to 10-month-old uninfected-unvaccinated calves (R. Brown, unpublished data). Since completion of those studies, it has been reported elsewhere that bovine natural killer (NK) cells make IFN-γ and have CD8 α and β chains on their surface and that these cells can expand in vitro with appropriate stimulation (28). Thus, it is possible that at least some of these CD8+ cells are NK cells. Periods of transient high spontaneous responses by bovine PBMC in in vitro cultures are a problem that had plagued researchers for some time, and while they are still unexplained, one study showed that a decrease in the fetal bovine serum levels ameliorated the problem (44). Unfortunately, the present study was terminated immediately after these high spontaneous responses were noted and so further analysis was not done.

The basis for the induction of a vigorous protective type 1 cell-mediated immune response afforded by the monovalent Leptospira serovar Hardjo vaccine used here and not by infection or pentavalent vaccines that contain serovar Hardjo (4-6) is unclear especially since the adjuvant for the vaccine used here was aluminum hydroxide, which induces Th2 or type 2 responses (8). Because ruminants have large numbers of circulating γδ T cells (11) that can fluctuate rapidly in the blood (3) and these cells produce IFN-γ (3, 41), we suggest that the response by this population may be particularly germane to establishing type 1 immunity in these animals. Precedence for the role of γδ T cells in establishment of the adaptive immune response comes from the recent observation that they influence development of type 1 antibody responses to mycobacterial infection in cattle (33). It is possible that γδ T-cell engagement occurs because components of the monovalent vaccine stimulate macrophage production of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1α, cytokines known to substitute for complete Freund's adjuvant for inducing cell-mediated immune responses (45) and to stimulate γδ T cells to produce type 1 cytokines (35). However, since responses by the WC1+ γδ T cells to the leptospire sonicate occur in the absence of CD4 T cells in vitro and have characteristics of a memory or recall response (41), leptospire components are likely to directly stimulate the γδ T cells in vivo. Leptospira may have components similar to the mycobacterial γδ T-cell-stimulating heat shock proteins (42) and low-molecular-weight phosphorylated molecules that stimulate through the TCR (13, 32). Alternatively, the LPS of leptospires has been shown previously to interact with TLR2 (52), a signaling receptor also expressed by γδ T cells during bacterial infections (38).

It is noteworthy that γδ T cells are a major population of T cells in the ruminant uterus (24)—a target organ of leptospire infections. In addition, IFN-τ produced in the ruminant uterus is known to stimulate expansion of γδ T cells, albeit the WC1− cells (50). In this environment they may contribute to a protective role as shown elsewhere for other primary bacterial infections (27, 34, 39). However, the opposite effect has also been shown. That is, γδ T cells can negatively affect response to bacterial antigens by bovine CD4 T cells (46) and control of bacterial infections in mice (43). Future experiments are planned to directly evaluate their role in development of the response to vaccination and protection against leptospirosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank J.-J. Letesson for providing the anti-IFN-γ MAbs, Rick Hornsby and Annette Olson for their excellent technical assistance, Cyril Gay for helpful discussions in preparing the manuscript, and Bill Ellis for discussions concerning responses to leptospiral vaccines.

This work was supported in part by a grant from Pfizer, Inc. (C.L.B.); a grant from CSL, Ltd. (C.A.B.); and USDA NRI Competitive Grant no. 2000-02293 (C.L.B.).

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arimitsu, Y., E. Kmety, Y. Ananyina, G. Baranton, I. R. Ferguson, L. Smythe, and W. J. Terpstra. 1994. Evaluation of the one-point microcapsule agglutination test for diagnosis of leptospirosis. Bull. W. H. O. 72:395-399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin, C. L., A. J. Teale, J. Naessens, B. M. Goddeeris, N. D. MacHugh, and W. I. Morrison. 1986. Characterization of a subset of bovine T-lymphocytes by monoclonal antibodies and function: similarity to lymphocytes defined by human T4 and murine L3T4. J. Immunol. 136:4385-4391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldwin, C. L., T. Sathiyaseelan, M. Rocchi, and D. McKeever. 2000. Rapid changes occur in the percentage of circulating bovine WC1+ γδ Th1 cells. Res. Vet. Sci. 69:175-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolin, C. A., R. L. Zuerner, and G. Trueba. 1989. Effect of vaccination with a pentavalent leptospiral vaccine containing Leptospira interrogans serovar Hardjo type hardjo-bovis on type hardjo-bovis infection of cattle. Am. J. Vet. Res. 50:2004-2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolin, C. A., and J. A. Cassells. 1990. Isolation of leptospira interrogans serovar bratislava from stillborn and weak pigs in Iowa. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 196:1601-1604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolin, C. A., J. A. Cassells, R. L. Zuerner, and G. Trueba. 1991. Effect of vaccination with a monovalent Leptospira interrogans serovar Hardjo type hardjo-bovis vaccine on type hardjo-bovis infection of cattle. Am. J. Vet. Res. 52:1639-1643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolin, C. A., and D. P Alt. 2001. Use of a monovalent leptospiral vaccine to prevent renal colonization and urinary shedding in cattle exposed to Leptospira borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo. Am. J. Vet. Res. 62:995-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewer, J. M., M. Conacher, C. A. Hunter, M. Mohrs, F. Brombacher, and J. Alexander. 1999. Aluminum hydroxide adjuvant initiates strong antigen-specific Th2 responses in the absence of IL-4 or IL-13-mediated signaling. J. Immunol. 163:6448-6454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown, W. C., T. F. McElwain, G. H. Palmer, S. E. Chantler, and D. M. Estes. 1999. Bovine CD4+ T-lymphocyte clones specific for rhoptry-associated protein 1 of Babesia bigemina stimulate enhanced immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2 synthesis. Infect. Immun. 67:155-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chinen, T., M. H. Qureshi, Y. Koguchi, and K. Kawakami. 1999. Candida albicans suppresses nitric oxide (NO) production by interferon-γ and lipopolysaccharide-stimulated murine peritoneal macrophages. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 115:491-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clevers, H., N. D. MacHugh, A. Bensaid, S. Dunlap, C. L. Baldwin, A. Kaushal, K. Iams, C. J. Howard, and W. I. Morrison. 1990. Identification of a bovine surface antigen uniquely expressed on CD4−CD8− T cell receptor-γδ+ T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 20:809-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole, J. R., C. R. Sulzer, and A. R. Pursell. 1973. Improved microtechnique for the leptospiral microscopic agglutination test. Appl. Microbiol. 25:979-980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Constant, P., Y. Poquet, M. Peyrat, F. Davodeau, M. Bonneville, and J.-J. Fournie. 1995. The antituberculous Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine is an attenuated mycobacterial producer of phosphorylated nonpeptidic antigens for human γδ T cells. Infect. Immun. 63:4628-4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhaliwal, G. S., R. D. Murray, and W. A. Ellis. 1996. Reproductive performance of dairy herds infected with Leptospira interrogans serovar Hardjo relative to year of diagnosis. Vet. Rec. 138:272-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhaliwal, G. S., R. D. Murray, H. Dobson, J. Montgomery, and W. A. Ellis. 1996. Reduced conception rates in dairy cattle associated with serological evidence of Leptospira interrogans serovar Hardjo infection. Vet. Rec. 139:110-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis, W. A., J. J. O'Brien, D. G. Bryson, and D. P. Mackie. 1985. Bovine leptospirosis: some clinical features of serovar Hardjo infection. Vet. Rec. 117:101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis, W. A., J. Montgomery, and J. A. Cassells. 1985. Dihydrostreptomycin treatment of bovine carriers of leptospira interrogans serovar Hardjo. Res. Vet. Sci. 39:292-295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellis, W. A., S. W. J. McDowell, D. P. Mackie, J. M. Pollock, and M. J. Taylor. 2000. Immunity to bovine leptospirosis. In Proceedings of the 21st World Buiatrics Congress, Punte del Este, Uruguay.

- 19.Estes, D. M., N. M. Closser, and G. K. Allen. 1994. IFN-γ stimulates IgG2 production from bovine B cells costimulated with anti-mu and mitogen. Cell. Immunol. 154:287-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faine, S., B. Adler, C. A. Bolin, and P. Perolat. 1999. Leptospira and leptospirosis, 2nd ed. MediSci Press, Melbourne, Australia.

- 21.Giles, N., S. C. Hathaway, and A. E. Stevens. 1983. Isolation of Leptospira interrogans serovar Hardjo from a viable premature calf. Vet. Rec. 113:174-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goddeeris, B. M., C. L. Baldwin, O. Ole-MoiYoi, and W. I. Morrison. 1986. Improved methods for purification and depletion of monocytes from bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Functional evaluation of monocytes in responses to lectins. J. Immunol. Methods 89:156-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerreiro, H., J. Croda, B. Flannery, M. Mazel, J. Matsunaga, M. G. Reis, P. N. Levett, A. I. Ko, and D. A. Haake. 2001. Leptospiral proteins recognized during the humoral immune response to leptospirosis in humans. Infect. Immun. 69:4958-4968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen, P. J., and W. Liu. 1996. Immunological aspects of pregnancy: concepts and speculations using the sheep as a model. Ann. Reprod. Sci. 42:483-493. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heath, S. E., and R. Johnson. 1994. Leptospirosis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 205:1518-1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins, R. J., J. F. Harbourne, T. W. A. Little, and A. E. Stevens. 1980. Mastitis and abortion in dairy cattle associated with leptospira of the serotype Hardjo. Vet. Rec. 27:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiromatsu, K., Y. Yoshikai, G. Matsuzaki, S. Ohga, K. Muramori, K. Matsumoto, J. A. Bluestone, and K. Nomoto. 1992. A protective role of γδ T cells in primary infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J. Exp. Med. 175:49-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hope, J. C., P. Sopp, and C. J. Howard. 2002. NK-like CD8+ cells in immunologically naïve neonatal calves that respond to dendritic cells infected with Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J. Leukoc. Biol. 71:184-194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson, R. C., and P. Rogers. 1964. Differentiation of pathogenic and saprophytic leptospires with 8-azaguanine. J. Bacteriol. 88:1618-1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jost, B. H., B. Adler, T. Vihn, and S. Faine. 1986. A monoclonal antibody reacting with a determinant on leptospiral lipopolysaccharide protects guinea pigs against leptospirosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 22:269-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaposzta, R., P. Tree, L. Marodi, and S. Gordon. 1998. Characteristics of invasive candidiasis in gamma interferon- and interleukin-4-deficient mice: role of macrophages in host defense against Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 66:1708-1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaufmann, S. H. E. 1996. γδ and other unconventional T lymphocytes: what do they see and what do they do? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2272-2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy, H. E., M. D. Welsh, D. G. Bryson, J. P. Cassidy, F. I. Forster, C. J. Howard, R. A. Collins, and J. M. Pollock. 2002. Modulation of immune responses to Mycobacterium bovis in cattle depleted of WC1+ γδ T cells. Infect. Immun. 70:1488-1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ladel, C. H., C. Blum, A. Dreher, K. Reifenberg, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1995. Protective role of gamma/delta T cells and alpha/beta T cells in tuberculosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:2877-2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lahn, M., H. Kalataradi, P. Mittelstadt, E. Pflum, M. Vollmer, C. Cady, A. Mukasa, A. T. Vella, D. Ikle, R. Harbeck, R. O'Brien, and W. Born. 1998. Early preferential stimulation of γδ T cells by TNF-α. J. Immunol. 160:5221-5230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masuzawa, T., R. Nakamura, Y. Hashiguchi, T. Shimizu, Y. Iwamoto, T. Morita, and Y. Yanagihara. 1990. Immunological reactivity and passive protective activity of monoclonal antibodies against protective antigen (PAg) of Leptospira interrogans serovar lai. Zentbl Bakteriol. Reihe A 272:328-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGuire, T. C., A. J. Musoke, and T. Kurtti. 1979. Functional properties of bovine IgG1 and IgG2: interaction with complement, macrophages, neutrophils and skin. Immunology 38:249-256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mokuno, Y., T. Matsuguchi, M. Takano, H. Nishimura, J. Washizu, T. Ogawa, O. Takeuchi, S. Akira, Y. Nimura, and Y. Yoshikai. 2000. Expression of toll-like receptor 2 on gamma delta T cells bearing invariant Vγ6/Vδ1 induced by Escherichia coli infection in mice. J. Immunol. 165:931-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mombaerts, P., J. Arnoldi, F. Russ, S. Tonegawa, and S. H. E. Kaufman. 1993. Different roles of αβ and γδ T cells in immunity against an intracellular bacterial pathogen. Nature 365:53-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy, E., J. Sathiyaseelan, and C. L. Baldwin. 2001. Interferon-gamma is crucial for surviving a Brucella abortus infection in both resistant C57BL/6 and susceptible BALB/c mice. Immunology 103:511-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naiman, B., D. Alt, C. A. Bolin, R. Zuerner, and C. L. Baldwin. 2001. Protective killed Leptospira borgpetersenii vaccine induces potent Th1 immunity comprising responses by CD4 and γδ T lymphocytes. Infect. Immun. 69:7550-7558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Brien, R. L., Y.-X. Fu, R. Cranfill, A. Dallas, C. Ellis, C. Reardon, J. Lang, S. R. Carding, R. Kubo, and W. Born. 1992. Heat shock protein Hsp60-reactive gamma delta cells: a large, diversified T-lymphocyte subset with highly focused specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:4348-4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Brien, R. L., X. Yin, S. A. Huber, K. Ikuta, and W. K. Born. 2000. Depletion of a γδ T cell subset can increase host resistance to a bacterial infection. J. Immunol. 165:6472-6479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orlik, O., and G. A. Splitter. 1996. Optimization of lymphocyte proliferation assay for cells with high spontaneous proliferation in vitro: CD4+ T cell proliferation in bovine leukemia virus infected animals with persistent lymphocytosis. J. Immunol. Methods 199:159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pape, K. A., A. Khoruts, A. Mondino, and M. K. Jenkins. 1997. Inflammatory cytokines enhance the in vivo clonal expansion and differentiation of antigen activated CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 159:591-598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhodes, S. G., R. G. Hewinson, and H. M. Vordermeier. 2001. Antigen recognition and immunomodulation by γδ T cells in bovine tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 166:5604-5610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sathiyaseelan, T., and C. L. Baldwin. 2000. Evaluation of cell replication by bovine T cells in polyclonally-activated cultures using carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) loading and flow cytometric analysis. Res. Vet. Sci. 69:275-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sieling, P. A., J. S. Abrams, M. Yamamura, P. Salgame, B. R. Bloom, T. H. Rea, and R. L. Modlin. 1993. Immunosuppressive roles for IL-10 and IL-4 in human infection. In vitro modulation of T cell responses in leprosy. J. Immunol. 150:5501-5510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smyth, A. J., M. D. Welsh, R. M. Girvin, and J. M. Pollock. 2001. In vitro responsiveness of γδ T cells from Mycobacterium bovis-infected cattle to mycobacterial antigens: predominant involvement of WC1+ cells. Infect. Immun. 69:89-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tuo, W., F. W. Bazer, W. C. Davis, D. Zhu, and W. C. Brown. 1999. Differential effects of type I IFNs on the growth of WC1− CD8+ γδ T cells and WC1+ CD8− γδ T cells in vitro. J. Immunol. 162:245-253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varga, S. M., and R. M. Welsh. 1998. Cutting edge: detection of a high frequency of virus-specific CD4+ T cells during acute infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Immunol. 161:3215-3218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Werts, C. R., I. Tapping, J. C. Mathison, T. H. Chuang, V. Kravchenko, I. Saint Girons, D. A. Haake, P. J. Godowski, F. Hayashi, A. Ozinsky, D. M. Underhill, C. J. Kirschning, H. Wagner, A. Aderem, P. S. Tobias, and R. J. Ulevitch. 2001. Leptospiral lipopolysaccharide activates cells through a TLR2-dependent mechanism. Nat. Immunol. 2:286-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weynants, V., K. Walravens, C. Didembourg, P. Flanagan, J. Godfroid, and J.-J. Letesson. 1998. Quantitative assessment by flow cytometry of T-lymphocytes producing antigen-specific γ-interferon in Brucella immune cattle. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 66:309-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weynants, V., J. Godfroid, B. Limbourg, C. Segerman, and J.-J. Letesson. 1995. Specific bovine brucellosis diagnosis based on in vitro antigen-specific gamma-interferon production. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:706-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wyatt, C. R., C. Madruga, C. Cluff, S. Parish, M. J. Hamilton, and W. C. Davis. 1994. Differential distribution of γδ T cell receptor lymphocyte subpopulations in blood and spleen of young and adult cattle. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 40:187-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]