Abstract

Nonnative disulfide bond formation can play a critical role in the assembly of disulfide bonded proteins. During the folding and assembly of the P22 tailspike protein, nonnative disulfide bonds form both in vivo and in vitro. However, the mechanism and identity of cysteine disulfide pairs remains elusive, particularly for P22 tailspike, which contains no disulfide bonds in its native, functional form. Understanding the interactions between cysteine residues is important for developing a mechanistic model for the role of nonnative cysteines in P22 tailspike assembly. Prior in vivo studies have suggested that cysteines 496, 613, and 635 are the most likely site for sulfhydryl reactivity. Here we demonstrate that these three cysteines are critical for efficient assembly of tailspike trimers, and that interactions between cysteine pairs lead to productive assembly of native tailspike.

INTRODUCTION

Disulfide bonds stabilize proteins and can direct folding, but few disulfide-bonded proteins are believed to exist in the bacterial cytoplasm (Gilbert, 1990). Further, it is widely believed that formation of disulfide bonds is not favored in the reducing environment of the cytoplasm. The identification of a disulfide-bonded intermediate in the folding and assembly pathway of the nondisulfide-bonded P22 tailspike protein (Robinson and King, 1997) has suggested that cysteines and disulfide bonds may play a role in the folding and assembly of cytoplasmic proteins. Additionally, the recent discovery of transient disulfide bond formation during the assembly of the Vp1, the major capsid protein of simian virus 40 (Li et al., 2002), further suggests that disulfide interactions may be more prevalent in the overall reducing environment of the cytoplasm of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms than expected based on the reducing potential. Our goals are to understand the role and mechanism of this transient disulfide bond formation during folding and assembly of the P22 tailspike trimer.

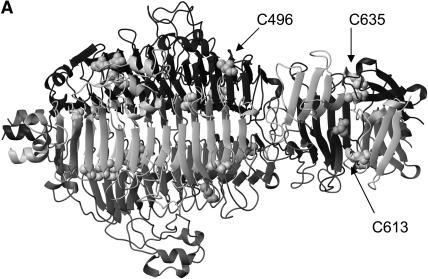

The tailspike protein from the P22 bacteriophage has been a useful system for investigating complex, oligomeric protein folding and assembly reactions (Goldenberg et al., 1982; Goldenberg and King, 1982; Goldenberg et al., 1983; Seckler et al., 1989; Speed et al., 1995; Robinson and King, 1997; Speed et al., 1997). The crystal structure has been solved at high resolution by x-ray crystallography (Steinbacher et al., 1994) (Fig. 1 A). The 210-kDa trimer is composed of three identical monomers of 666 amino acids each. Based on the crystal structure, no covalent linkages exist between the polypeptide chains in the native state (Steinbacher et al., 1994). There are eight cysteines per monomer, and each has been shown to be in the reduced state in the native trimer in solution (Sargent et al., 1988). The three subunits comprising the native conformation are highly intertwined and confer extreme stability to the tailspike trimer. The trimer is resistant to denaturation by SDS and proteolytic hydrolysis and has a melting temperature greater than 80°C.

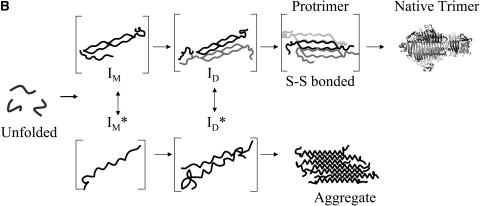

FIGURE 1.

Tailspike crystal structure and folding pathway. (A) Crystal structure of P22 tailspike (Steinbacher et al., 1994). The cysteine residues highlighted as stick and ball representations. Arrows point to residues 496, 613, and 635. (B) The folding and aggregation pathway of P22 tailspike (Goldenberg and King, 1982; Goldenberg et al., 1983; Speed et al., 1995; Robinson and King, 1997). IM and ID are productive monomer and dimer folding intermediates. IM* and ID* are early aggregation species. The protrimer intermediate contains at least two interchain disulfide bonds (Robinson and King, 1997) and is the trimeric precursor to the final native state (Goldenberg and King, 1982).

Tailspike monomer chains progress through two competing pathways both in vivo and in vitro: productive folding to form the native trimer and aggregation (Goldenberg et al., 1982; Goldenberg and King, 1982; Goldenberg et al., 1983; Seckler et al., 1989; Speed et al., 1995; Robinson and King, 1997; Speed et al., 1997) (Fig. 1 B). At 37°C, a significant fraction of the tailspike polypeptide chains aggregate and never reach the native state (Goldenberg et al., 1983; Haase-Pettingell et al., 2001). This observation highlights the importance of understanding amino acid interactions that govern this competition. Productive folding occurs through addition reactions to form dimer and the disulfide-bonded protrimer before final conversion to the native trimer (Goldenberg et al., 1983; Robinson and King, 1997) (Fig. 1 B). Previous studies have shown that interchain disulfide bonds link three subunits in the protrimer (Robinson and King, 1997). Once reduced, the protrimer is able to form native trimer (Robinson and King, 1997), which contains no disulfide bonds (Sargent et al., 1988; Steinbacher et al., 1994). Aggregates and aggregation intermediates do not contain interchain disulfide bonds (Speed et al., 1995; Betts and King, 1998).

The in vivo expression and trimer stability of cysteine to serine point mutations have been investigated previously (Haase-Pettingell et al., 2001). Each single point mutation resulted in native trimer with wild-type activity and thermostability. Native trimer yields at various expression temperatures suggested that several cysteine residues may be important during folding and assembly, including Cys-287, Cys-290, Cys-496, Cys-613, and Cys-635. Investigations into the reactivity of the cysteine side chains found that the five N-terminal cysteines were not labeled by iodo[14C]acetamide (Sather and King, 1994). Coupled with the observation that there were three cysteines labeled with iodoacetamide per tailspike polypeptide chain (Robinson and King, unpublished data), this suggested that the C-terminal cysteines at 496, 613, and 635 were the most probable sites for disulfide bond formation in the folding intermediates.

We sought to identify unambiguously whether the cysteines at 496, 613, and 635 play a role in folding and assembly, whether they interact, and how they affect the competition between folding and aggregation. We find that mutations at cysteines 496, 613, or 635 decreases trimer rates and yields by slowing down the association of tailspike chains. We further find that pairwise interactions between cysteines 613 and 635 are required for productive assembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

DTT, SDS, glycine, Tris, and EDTA were obtained from BioRad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Electrophoresis grade urea and GdnHCl were obtained from Fisher Scientific, (Hampton, NH). IPTG and sodium chloride were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Mutant construction

The tailspike gene was expressed from a pET-11a expression plasmid (Novagen, Madison, WI) (Haase-Pettingell et al., 2001). Single cysteine to serine mutants were produced by using the Quik-Change Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX), and the double and triple mutants were produced by cassette mutagenesis. All mutants were fully sequenced (University of Pennsylvania, DNA Sequencing Facility), and no second mutation sites were found.

Protein expression

Bacterial cells were made competent for transformation by electroporation (Weaver, 1993) or heat shock (Sambrook et al., 1989). Cells were then transformed with plasmid DNA via electroporation (BioRad Gene Pulser) or heat shock (Sambrook et al., 1989), and plasmid selection maintained by AMP addition (100 μg/ml). Transformed cells were grown at the desired temperature in LB (Sambrook et al., 1989) containing AMP (LB-AMP) to an OD600 of 0.5–0.7, and protein expression was induced by the addition of IPTG to 1 mM. Protein was expressed for 3–4 h. Aliquots of cell culture were removed and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 2 min to pellet cells. The cell pellet was resuspended to 8 OD-mls, approximately one-fourth the original culture volume, in lysis solution (50 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM MgSO4, 20 μg/ml DNase, 100 μg/ml lysozyme, 0.1% Triton-X100) and subjected to two freeze-thaw cycles to complete lysis. The lysed cells were then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min to separate the pellet (insoluble protein aggregate) from the supernatant (soluble protein). The supernatant was decanted and one-half volume 3× SDS sample buffer (163 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 0.25 mg/ml bromphenol blue, 5 mg/ml SDS, 50% glycerol) was added. The pellet was resuspended in 1× sample buffer to the original volume of the lysis solution. In vivo expression samples were separated on 7.5% SDS gels at a constant current of 20 mA/gel for ∼4 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized by silver staining.

All tailspike mutants were produced and purified from overexpression in wild-type DHB4 (DE3) Escherichia coli cells, essentially as described (King and Yu, 1986). Radioactive tailspike protein was obtained from overexpression in BL21 E. coli and M9 minimal medium (Sambrook et al., 1989). Thirty minutes after protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG, 1 mCi/L of 14C-labeled amino acids was added to the media and allowed to incubate at 25°C for 4 h. Tailspike protein was then purified as described (King and Yu, 1986).

GdnHCl denaturation curves

Freshly prepared 8 M GdnHCl in 50 mM Tris at pH 7.6 and 1 mM EDTA was used in all measurements. More dilute concentrations of GdnHCl were prepared by mixing the 8 M stock with Tris refolding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA). Tailspike protein at a concentration of 50 μg/ml was incubated with the indicated concentrations of GdnHCl for 45–75 min. Fluorescence spectra were measured from 300 to 400 nm after excitation at 280 nm on an ISS PC1 spectrofluorometer (ISS, Champaign, IL). Spectra for each of the various GdnHCl buffers were collected and subtracted from the spectra containing protein to eliminate the contribution of buffer components. The centers of mass of the corrected spectra were calculated using ISS software. The fluorescence spectra were all collected in a window where the fluorescence intensity had plateaued (data not shown). Percent unfolded protein curves was obtained from fitting the center of mass versus GdnHCl curves to a two-state unfolding model. This analysis is strictly appropriate only for reversible processes; however, the derived relationships fit the data for unfolding well. The midpoints of these curves provide a convenient comparison of the stability of the different trimers in this denaturant.

Circular dichroism

Tailspike protein solutions were prepared at a concentration of 10 μg/ml in 5 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA at pH 7.6. Spectra were collected on an Aviv Model 215 spectrometer (Aviv, Lakewood, NJ) from 300–180 nm, with data recorded every 2 nm for 3 s at 25°C. Each sample was analyzed twice and averaged after a subtraction of the buffer blank.

In vitro tailspike refolding

Purified tailspike protein was denatured at 1 mg/ml with 8 M urea at pH 3.0 in 50 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA for 45–75 min. Refolding was initiated by dilution into a Tris refolding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA) to the appropriate final protein concentration. For nonradioactive reactions, sample aliquots were taken at the indicated times, added to 3× native sample buffer (15 mM Tris base, 0.12 M glycine, 0.25 mg/mL bromphenol blue, 30% glycerol), and placed on wet ice to halt folding. Samples were electrophoresed through nondenaturing gels and visualized with silver staining.

Radioactive protein refolding reactions were monitored by taking sample aliquots at the indicated times, quenching with 3× SDS sample buffer (163 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 0.25 mg/mL bromphenol blue, 5 mg/mL SDS, 50% glycerol), and placing on wet ice. Samples were separated on SDS gels, fixed, and dried onto filter paper. The dried gels were exposed to phosphor screens for 24–48 h.

Kinetics as monitored by fluorescence

Purified tailspike was denatured as for in vitro refolding studies. An optically-clear quartz cuvette, which had been rinsed with a 5% Tween solution, was used in all fluorescent measurements. An amount of 2475 μl of refolding buffer was added to the cuvette, and the background fluorescence at 340 nm was measured after excitation at 280 nm on an ISS PC1 spectrofluorometer. A total of 25 μl of denatured protein was added and rapidly mixed into the bulk buffer to initiate refolding. The solution was excited at 280 nm through a 0.5-mm slit, and the emission was recorded at 340 nm through a 2-mm slit to minimize photobleaching. The fluorescence intensity at 340 nm was measured every 15 s for 1 h. Measured fluorescence intensity was corrected for background buffer fluorescence and plotted as a fraction of the plateau with time. The data were fit to a first-order relationship, as described previously (Danner and Seckler, 1993).

Protein yield and trimer formation rate determination

Radioactive phosphor images were analyzed using NIH Image software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Trimer concentrations were determined by measuring the trimer band density and correcting for the variation in total density in each gel lane. Alternatively, nonradioactive folding reaction samples were separated on nondenaturing gels and visualized by silver staining. Four or five trimer standards were used to determine a linear calibration curve between band density and trimer concentration. Great care was taken to ensure that trimer band densities remained in the linear range of the silver staining. Final refolding yields were determined from 5 to 7 independent reactions after at least 6 h of refolding for the 20 μg/ml reactions or at least 20 h of refolding for 100 μg/ml reactions. Rate constants were calculated using the silver-stained band density method and compared with values derived from radioactive experiments. The constants of both methods were within the experimental error (data not shown).

Kinetic rate constants (k) were determined by the following analysis. The formation of trimer (cT) was approximated as a first-order process, described in Eq. 1 below. Parameters were estimated in two parts, first with an initial least squares fit to the full equation and then with a linear regression model, Eq. 2. Parameter estimates from the two methods were within 10% of each other, ensuring that both the early and late time points were given similar weight in the fits.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

A represents the final trimer yields; B incorporates the lag before appearance of detectable trimer levels, and k is the first-order kinetic rate constant. The assumptions inherent in the derivation of this relationship hold mainly at low protein concentrations, where the majority of unfolded monomer folds into trimer. This analysis is not strictly accurate for describing folding kinetics under aggregating conditions as it discounts the competition with the aggregation pathway. However, it allows for a convenient comparison between the behaviors of different mutants at various conditions. The individual uncertainties associated with independently calculated rate constants were averaged to give an overall error for the weight-averaged rate constants.

RESULTS

Serine point mutations do not alter structure and stability of resulting trimer

Purified tailspike proteins were subjected to biophysical characterization to evaluate the effect of the point mutations on the native trimer. The single cysteine-to-serine mutations have previously been shown to have wild-type P22 head binding activity, indicating that the mutations do not affect the function of the protein (Haase-Pettingell et al., 2001). Similarly, Raman spectra of each of the single serine mutants indicated that tertiary and quaternary structures were not disrupted by the point mutations (Raso et al., 2001). Additionally, a comparison of the circular dichroism spectra of the wild-type and the C-terminal serine mutants demonstrated good agreement between the proteins (data not shown), indicating similar secondary structure. All spectra showed the characteristic trough of a β-sheet protein at around 220 nm.

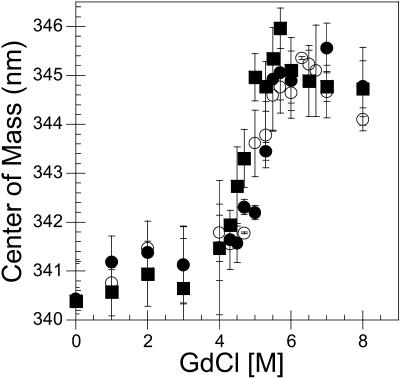

The effect of the mutations on the stability of the resulting trimers was investigated by measuring the center of mass of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of tailspike mutants in varying concentrations of GdnHCl. The percent of folded protein present at increasing concentrations of GdnHCl for each of the serine mutations mapped closely to the wild-type tailspike curve (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The stability of the native trimer in GdnHCl was not altered due to the presence of these point mutations.

FIGURE 2.

Point mutations at cysteine residues do not alter stability of tailspike trimer. Purified trimer treated with different concentrations of guanidine hydrochloride was incubated at room temperature for 45–75 min before fluorescence spectra were recorded. Center of mass of the spectra was calculated by ISS system software as described in Materials and Methods. Wild-type tailspike is shown as open circles, C635S as closed squares, and C613S as closed circles. Other mutant data are not shown for clarity, but the fits for the data are included in Table 1. Data represent the average of at least three independent measurements, with the error bars indicating the standard deviation from the average.

TABLE 1.

Midpoints of unfolding in the presence of guanidine hydrochloride show that the cysteine-to-serine mutations do not alter the stability of the resulting trimers

| Tailspike variant | Midpoint of unfolding (M) |

|---|---|

| Wild-type | 5.2 ± 0.1 |

| C496S | 5.3 ± 0.1 |

| C613S | 5.1 ± 0.2 |

| C635S | 5.3 ± 0.2 |

| C496S/C635S | 5.2 ± 0.1 |

Reported values are the guanidine concentration at which 50% of the tailspike trimer is unfolded, determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Cysteine mutants have reduced in vitro refolding yields in comparison to wild-type

In vitro, the competing pathways of productive folding and aggregation are influenced by several experimental parameters, including temperature and protein concentration. At low protein concentrations and temperatures (20 μg/ml and 20°C), the productive folding pathway is favored, but as either variable is increased, aggregation predominates. We were interested in characterizing the refolding behavior of the cysteine mutants under various conditions to determine the critical residues during folding and assembly and potentially identify the specific function of these interactions.

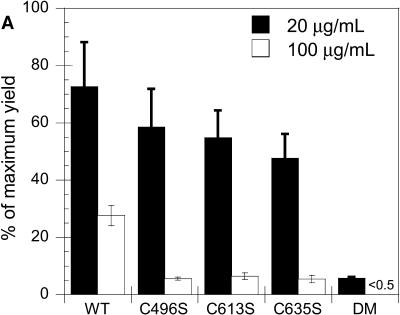

Refolding reactions were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Reactions were incubated at 20°C for 8–20 h and separated on nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels. Trimer yields were calculated by correlating gel band densities to a linear calibration curve as described in Materials and Methods. At 20 μg/ml, wild-type tailspike had a refolding yield of ∼75%, and each of the single mutants had slightly reduced yields of 48–60% (Fig. 3 A, solid bars). The double mutant C496S/C635S refolded to quite low yields, only ∼8%. This yield was much lower than the sum of the individual mutations would predict, suggesting that there are pairwise interactions between the cysteine residues.

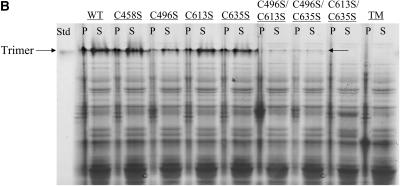

FIGURE 3.

Serine mutations decrease tailspike trimer yield. (A) Tailspike refolding yields of reactions carried out at 20 μg/ml (solid) and 100 μg/ml (open) at 20°C. Refolding was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Reactions were incubated overnight at 20°C and then separated on nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels. Gels were silver-stained, and trimer yields were calculated by correlation of gel band density to a linear calibration curve. Reported yields are the average of 4–8 independent reactions, and the error bars represent one standard deviation from the average. DM indicates the double mutant C496S/C635S. The yield of the C496S/C635S DM at 100 μg/ml was below the sensitivity of staining, <0.5 μg/ml. (B) Batch expression of wild-type and cysteine mutants in DHB4 cells at 16°C. Cells were grown to midlog phase in LB medium containing AMP. Protein expression was induced, and the cells were harvested and lysed as described in Materials and Methods. Soluble (S) and insoluble or cell pellet (P) fractions were separated and detected by SDS PAGE and silver staining. Std, trimer standard; lane 1, wild-type cell pellet (P); lane 2, wild-type soluble fraction (S); lane 3, C458S P; lane 4, C458S S; lane 5, C496S P; lane 6, C496S S; lane 7, C613S P; lane 8, C613S S; lane 9, C635S P; lane 10, C635S S; lane 11, C496S/C613S P; lane 12, C496S/C613S S; lane 13, C496S/C635S P; lane 14, C496S/C635S S; lane 15, C613S/C635S P; lane 16, C613S/C635S S; lane 17, C496S/C613S/C635S (Triple Mutant, TM) P; lane 18, TM S.

Cellular folding conditions are at relative protein concentrations much higher than 20 μg/ml. In vivo expression experiments showed that serine mutations at the three C-terminal cysteine residues significantly reduced trimer yields in comparison to wild-type, even at 16°C (Fig. 3 B). Each single mutation resulted in slightly lower yields (lanes 6, 8, and 10 compared to lane 2), but double and triple mutations at these residues (lanes 12, 14, 16, and 18) greatly reduced trimer yields. In fact, only C496S/C613S and C496S/C635S were able to produce trimer, albeit at nearly undetectable levels and only at the lowest expression temperature investigated (16°C) (arrow, lanes 12 and 14). Expression of these double and triple variants at temperatures greater than 16°C resulted in no detectable trimer (data not shown).

As the folding environment is altered, the partitioning between the productive and aggregation pathway is affected. Under harsher conditions (high temperature in vivo or high protein concentration in vitro), the aggregation pathway predominates. Although in vivo growth at low temperatures showed similar yields to refolding at 20 μg/ml (Fig. 3 A, solid bars, and Fig. 3 B), we wanted to evaluate the behavior of the serine mutants at higher protein concentrations to simulate in vivo results at more physiological conditions. At 37°C, King and colleagues (Haase-Pettingell et al., 2001) have shown that single cysteine-to-serine mutations at the three C-terminal cysteines reduced in vivo expression yields ∼95% in comparison to wild-type tailspike. In vitro, we find that high protein concentrations significantly reduced the ability of these mutant tailspikes to refold to trimer. Wild-type had a 28% trimer yield when refolded at 100 μg/ml, but C496S, C613S, and C635S each had refolding yields of 5% or less (Fig. 3 A, open bars). The yield of one of the double mutants, C496S/C635S, at these conditions was below the detection level of silver staining (∼0.5 μg/ml), indicating a refolding yield of <0.5%. This is consistent with an interaction between the cysteines at 496 and 635, as the effect is greater than that of the sum of the individual changes.

Serine mutants exhibit wild-type hydrophobic collapse as monitored by fluorescence

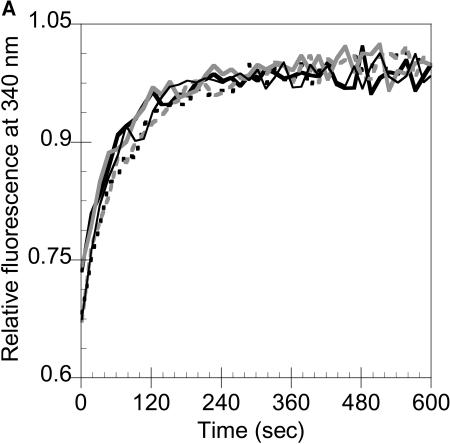

Previously, tailspike folding kinetics has been monitored through intrinsic fluorescence for wild-type and several tsf mutants (Danner and Seckler, 1993). Danner and Seckler (1993) have suggested that the intensity changes captured by fluorescence represent the collapse of denatured monomer to the structured subunit (M). Interestingly, fluorescence intensity with time behavior of the serine mutants did not reveal any significant differences in rate constants in comparison to wild-type (Fig. 4 A), as the rate of fluorescence recovery at 340 nm was the same for all protein variants. In contrast, native gel electrophoresis clearly showed the prolonged presence of folding intermediates of each of the serine mutants at much later times than in the wild-type reactions, even at low protein concentrations (Fig. 4 B). Although the change in fluorescence intensity reached a plateau after only 2–3 min (Fig. 4 A), trimer concentrations continue to increase until around 60 min in wild-type and 4–6 h for each of the serine mutants (Fig. 4 B). This suggests that subunit interactions and assembly in the serine mutants are impaired whereas the monomer folding is like that of wild-type chains.

FIGURE 4.

Serine mutants exhibit wild-type subunit folding kinetics but altered subunit assembly. (A) Fluorescence intensity recovery with time for wild-type and the serine mutants were identical. Denatured protein was rapidly diluted in refolding buffer to 10 μg/ml, as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were excited at 280 nm, and the emission at 340 nm was measured every 15 s during the time course. Wild-type tailspike, solid line; C496S, dashed line; C613S, gray solid line; C635S, gray dashed line; C496S/C635S, thin line. (B) Native PAGE shows reduced assembly rates and yields in mutants. Purified, denatured wild-type tailspike and the serine mutants were diluted to 20 μg/ml in refolding buffer. Samples were taken and subjected to native PAGE as described in Materials and Methods at 15 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 6 h.

Serine mutants display slower in vitro refolding kinetics than wild-type

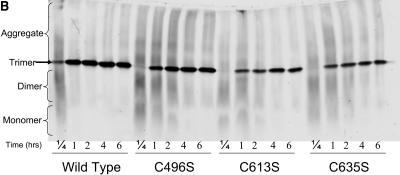

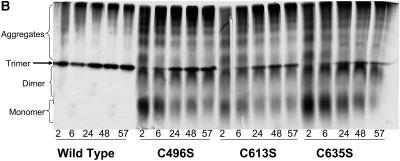

To further characterize the effect of the loss of cysteine functionality, we determined the rates at which the single cysteine-to-serine mutants were able to form trimer at in vitro conditions which favor folding and aggregation. Refolding samples were collected at various times and subjected to native PAGE. Trimer concentration with time data then were fit to a first-order exponential relationship as described in Materials and Methods. At low protein concentrations, where each of the three C-terminal cysteine mutants had reduced yields, trimer formation rates for the single mutants were lower than that of wild-type (Fig. 5 A, solid bars). C635S had the slowest rate of trimer formation, folding nearly two times slower than wild-type. Interestingly, the rate of C496S/C635S formation at low protein concentrations was nearly identical to C635S. Therefore, even though the yield of the refolding reaction was affected significantly in C496S/C635S, the rate of trimer formation occurred as fast as in C635S.

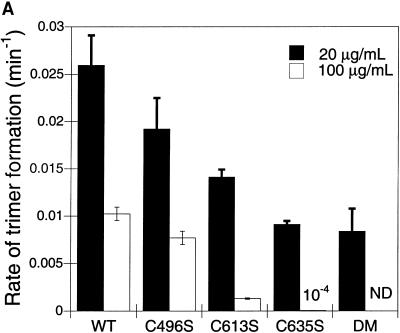

FIGURE 5.

C-terminal cysteine mutants fold more slowly than wild-type at both aggregating and folding conditions. (A) First-order trimer formation rates determined for wild-type and all cysteine mutants at 20 μg/ml (solid) and 100 μg/ml (open) at 20°C. Refolding was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Refolding samples were separated on 7% nondenaturing gels and visualized through silver staining. Trimer concentration versus time data was fit to cT = A − B exp(−kt), as outlined in Materials and Methods. The reported rates are the average of at least four independent experiments. Error was derived from both the fit to a first-order relationship and the deviation between the individual calculated values. DM indicates the double mutant C496S/C635S. ND indicates that the rate was not determined, as the trimer levels for the double mutant were below the sensitivity of staining. (B) Native PAGE shows severely reduced assembly in the serine mutants. Purified, denatured tailspike proteins were diluted to 100 μg/ml in refolding buffer. Samples were taken and separated on native PAGE as described in Materials and Methods at 2 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 57 h.

Under less favorable refolding conditions, the differences in folding yields between wild-type and the C-terminal cysteine mutants became dramatic (Fig. 3 A, open bars). Determining trimer formation rates at 100 μg/ml further supported the importance of the C-terminal cysteines during assembly, as decreased rates were observed (Fig. 5 A, open bars). This kinetic analysis revealed a disparity between the folding behaviors of the mutants at the cysteines located in the C-terminal interdigitated β-sheet region, C613S and C635S, and the mutant at the cysteine located at the C-terminal end of the β-helix domain, C496S. C613S and C635S folded 20 to 50 times slower than wild-type, whereas C496S had a trimer formation rate on the same order as seen in the wild-type reactions. At these conditions, the double mutant C496S/C635S did not form trimer (Fig. 3 A) and, therefore, trimer formation rates were not determined.

We examined refolding samples at these aggregation conditions to characterize the effect the cysteine mutations had on the folding intermediates. Once again, the folding intermediates in each of the three C-terminal cysteine mutants persisted at much longer times than the wild-type folding intermediates (Fig. 5 B). In fact, these cysteine mutants were unable to fold to completion with monomer and dimer intermediates present at seemingly constant levels even after over 50 h of refolding (Fig. 5 B). To evaluate whether in the mutants these species showed a defect in the ability to form higher-order aggregates, 100 μg/ml folding reactions were performed at a higher temperature (37°C), where only large multimer aggregates are formed in wild-type refolding reactions (Lefebvre and Robinson, 2003). After 30 min at the elevated temperature, the cysteine mutant reactions contained large molecular weight aggregates and were indistinguishable from the wild-type reactions (data not shown). Thus, the absence of the cysteine residues does not reduce the ability of the tailspike chains to aggregate. The simplest explanation is that there is a kinetic barrier preventing the cysteine mutants from further assembly reactions. The decreased ability of the folding intermediates of the mutants to associate supports the importance of cysteine residues in the trimer assembly processes.

The yields of in vitro reactions at 100 μg/ml more closely mirror in vivo behavior at 37°C (2–4% of wild-type tailspike expression yields) (Haase-Pettingell et al., 2001), so we believe these conditions capture in vivo phenotypes. Furthermore, the fact that C496S, C613S, and C635S had similar yields at the elevated protein concentration but different trimer formation rates may indicate that C613 and C635 play a different, and perhaps more important, role in the rate-determining step than C496.

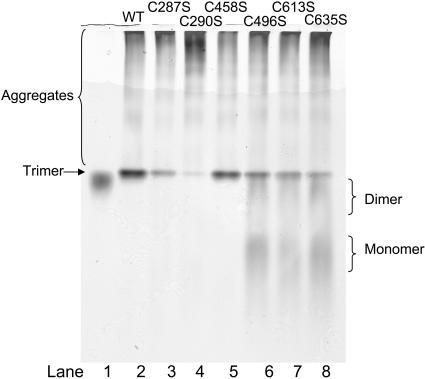

To ensure that a mutation at any cysteine residue did not produce similar results, the five other cysteines were mutated and the resulting folding behaviors examined. Of the eight cysteine residues, five led to reduced trimer yields in in vivo experiments, C287, C290, C496, C613, and C635 (Haase-Pettingell et al., 2001). Serine mutations at C169 and C267 result in wild-type trimer yields when expressed at 17°C and 30°C (Haase-Pettingell et al. 2001). A triple alanine mutant at cysteine 169, 267, and 458 also has wild-type trimer expression levels when expressed at both 17°C and 30°C (data not shown), indicating that these residues do not play a significant role in the trimer folding and assembly pathway. Single serine mutations at 287 or 290 resulted in wild-type expression levels at 17°C, but significantly reduced trimer levels at higher expression temperatures (Haase-Pettingell et al., 2001).

To determine whether mutations at 287 and 290 were having a similar effect on trimer assembly as the three C-terminal mutations, in vitro refolding of the serine mutants at these positions and C458S was performed. C458S served as a control mutant, since it exhibited wild-type tailspike behavior under all experimental conditions (Fig. 3 B, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, and data not shown). Although in vitro refolding reactions of the C287S and C290S mutants resulted in lower trimer yields, the refolding mixtures did not contain stalled intermediates as seen in the C-terminal cysteine mutants (Fig. 6, lanes 2–5, compared to lanes 6–8). Therefore the mutations at C287 and C290 act through a different mechanism to reduce trimer folding. Taken together, these data suggest that the cysteine residues at 496, 613, and 635 are likely playing specific roles in tailspike assembly.

FIGURE 6.

Only serine mutations at the C-terminal cysteines result in stalled folding intermediates. Tailspike protein was denatured in 8 M urea at pH 3.0 for 1 h at 20°C before rapid 10-fold dilution in Tris refolding buffer. Refolding reactions were incubated at 20°C overnight before one-half sample volume of native sample buffer was added to halt further association. Samples were separated on a 7% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. Lane 1, tailspike trimer; lane 2, wild-type refolding reaction; lane 3, C287S refolding reaction; lane 4, C290S refolding reaction; lane 5, C458S refolding reaction; lane 6, C496S refolding reaction; lane 7, C613S refolding reaction; lane 8, C635S refolding reaction.

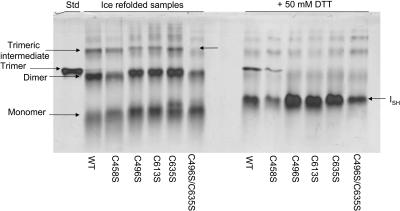

FIGURE 7.

C-terminal serine mutations display an altered trimer folding intermediate. Tailspike protein was denatured in 8 M urea at pH 3.0 for 1 h at 0°C before rapid 10-fold dilution in 0°C Tris refolding buffer. Refolding reactions were held on wet ice for 5 h before one-half sample volume of native sample buffer was added to halt further association. Aliquots were taken from each reaction and added to 100 mM DTT. Both sets of samples were separated on the same 9% nondenaturing acrylamide gel. (Left panel) WT, C458S, C496S, C613S, C635S, C496S/C635S. Arrows in the left panel highlight the trimeric folding intermediates present in the absence of reducing agent. (Right panel) Same samples as the left panel after the addition of 100 mM DTT. Arrows in the right panel show the reduced intermediate (ISH) present in all refolding reactions.

Cysteine-to-serine mutations lead to an altered trimeric folding intermediate

Mutations at the C-terminal cysteines affected overall trimer yield and assembly both in vivo and in vitro. We were also interested in examining the specific effects these mutations had on the folding intermediates. Tailspike was denatured as described above, but equilibrated on wet ice to 0°C. Equilibration on ice has been shown to allow for the accumulation of productive folding intermediates and decrease partitioning to the aggregation pathway (Xie and Wetlaufer, 1996; Betts and King, 1998). After 1 h, the denatured protein was rapidly diluted 10-fold into Tris refolding buffer that was preequilibrated to 0°C. Refolding was allowed to proceed on wet ice for 5 h before one-half sample volume of native sample buffer (see Materials and Methods) was added to halt further association.

Ice-refolded samples were separated on a nondenaturing gel to visualize the folding intermediates. The wild-type refolding samples contained predominately protrimer and dimer as well as some monomer intermediates (Fig. 7, lane 1). Although refolding at low temperatures reduced the fraction of protein that aggregated, there were still some aggregation species apparent in the sample (faint bands above trimer). Refolding samples of the cysteine to serine mutants prepared in parallel are shown in Fig. 7 (lanes 2–6). The refolding mixture of the C458S protein appeared almost identical to that for wild-type (Fig. 7, lane 2). Refolding on ice allowed for the accumulation of monomeric and predominately dimeric folding intermediates in each of the C-terminal single cysteine mutant samples (Fig. 7, lanes 3–5). The double mutant C496S/C635S contains mostly monomer and dimer and no apparent protrimeric intermediates (Fig. 7, lane 6).

The monomeric, dimeric, and protrimeric species exhibited altered mobilities in the C-terminal single cysteine mutants in comparison to wild-type (Fig. 7, lanes 3–6 compared to lane 1). The altered mobility of the prevalent dimer band of the C-terminal cysteine single mutants shifted the alignment such that it appears to run with similar size to the native trimer (Fig. 7, lanes 3–5). Separation of the refolding reactions on lower percentage gels confirmed that this species was indeed a folding intermediate and not native trimer (data not shown). Additionally, the mobility of native tailspike trimer on nondenaturing gels is insensitive to the presence of reducing agent (Robinson and King, 1997), whereas the mutant dimeric protein species dissociated when treated with 100 mM DTT (Fig. 7, lanes 3–5 compared to lanes 9–11). As expected, the folding intermediates in the C458S refolding mixture ran with identical mobility to the wild-type intermediates (Fig. 7, lanes 1 and 2). One possible reason for the mobility differences in the C-terminal cysteine mutants is that altered conformations are adopted by the folding intermediates when all the wild-type C-terminal cysteine residues are not present.

The tailspike folding intermediates have been shown to be sensitive to reducing agents (Robinson and King, 1997; Betts and King, 1998). We were interested in characterizing the behavior of the folding intermediates of the C-terminal cysteine mutants in the presence of reducing agents to establish whether or not there were any further physical differences from those of wild-type. In wild-type, the reduction of interchain disulfide bonds in the protrimer leads directly to the formation of the native trimer (Robinson and King, 1997). Upon addition of 100 mM DTT to the refolding samples shown in the left panel of Fig. 7, only the wild-type and C458S protrimeric intermediates were reduced to form native trimer (Fig. 7, lanes 7 and 8). The single C-terminal serine mutants and the double mutant showed no native trimer in the presence of reducing agent, indicating the trimeric intermediate does not have wild-type protrimer characteristics.

It has been proposed that the dimer intermediate contains interchain disulfide bonds (Betts and King, 1998). Two-dimensional electrophoresis of separated folding intermediates showed that the dimer intermediate shifted mobility after incubation with reducing agents in wild-type as well as all the C-terminal cysteine mutants investigated, consistent with the presence of an interchain disulfide bond (data not shown). The prevalent dimer band present in the refolding mixtures of both the wild-type and cysteine mutants disappeared after treatment with 100 mM DTT (Fig. 7, lanes 7–12). The monomer species seen in the refolding mixtures in the left panel (Fig. 7, lanes 1–6) also vanished after the addition of reducing agent (Fig. 7, lanes 7–12). The change in mobility of the monomer in the presence of reducing agent indicated the existence of an intrachain disulfide bond. The appearance of a single, discrete band in the presence of reducing agent suggests that the monomer and dimer folding intermediates reduce to a single conformation (Fig. 7, right panel, ISH). The distinct band of the protrimeric intermediate of the C-terminal cysteine mutants also disappears upon the addition of reducing agents (Fig. 7, lanes 9–11 compared to lanes 3–5), but, unlike wild-type, does not form native trimer (Fig. 7, lanes 9–11 compared to lane 7). It seems likely that the interchain disulfide bonds in the protrimer of the C-terminal cysteine mutants are reduced to the same conformation as the monomer and dimer intermediates. Aggregation species do not contain disulfide bonds (Speed et al., 1995; Betts and King, 1998). Therefore the faint aggregation bands observed do not exhibit altered mobility in the presence of reducing agent and are still apparent in all the samples in the right panel of Fig. 7.

DISCUSSION

C-terminal cysteines play a role in tailspike trimer assembly reactions

Refolding yields in the in vitro refolding reactions of the C-terminal cysteine mutants were lower than wild-type at all conditions investigated. At low total protein concentration, where productive folding is favored, the C-terminal cysteine mutants were able to form trimer, although at slightly lower levels and slower rates than wild-type. At these conditions, the change in fluorescence intensity with time indicated that the cysteine mutants were forming monomer at the same rate as wild-type. Inspection of the folding intermediates in the reaction mixtures revealed an increased lifetime of the productive subunits in the C-terminal cysteine mutant refolding samples. Thus the defect seen in the C-terminal cysteine reactions was occurring after monomer formation, during the assembly of on-pathway subunits.

Refolding reactions performed at a total protein concentration of 100 μg/ml, where competition with the aggregation pathway is significant, led to even lower yields and slower trimer formation rates in the C-terminal cysteine mutants in comparison to wild-type. Under these conditions, hindered subunit assembly resulted in stalled populations of monomeric and dimeric intermediates in the C-terminal cysteine mutant refolding reactions. Because cysteine mutants were able to form aggregates at 37°C, these populations did not represent aggregation-deficient conformations, but rather productive intermediates unable to progress through the folding pathway.

The function the disulfide bonds may be playing during the folding and assembly of the tailspike trimer is unknown. The C-terminus is composed of a “β-prism” domain, where β-strands from all three subunits contribute to three interwoven β-sheets (Haase-Pettingell et al., 2001). Contacts between the chains may be stabilized through interchain disulfide bonds, holding the chains in register for sufficient time for further association to occur. In this manner, disulfide bonds between subunits could lower the activation energy barrier of assembly reactions. Assembly intermediates may be kinetically trapped in a local free energy minimum in the absence of essential cysteine residues arising from an inability to form these stabilizing disulfide bonds.

Partitioning between folding and aggregation pathway occurs before assembly

The competing aggregation pathway complicates tailspike folding investigations. Researchers have altered in vitro refolding conditions to manipulate the partitioning between folding and aggregation (Mitraki et al., 1993; Speed et al., 1995), but questions still remain about the branch point and interaction between the pathways. The characterizations of several tsf mutants indicate that an early folding intermediate is destabilized and leads to an increased partitioning to the aggregation pathway (Danner and Seckler, 1993; Mitraki et al., 1993). These folding defects can be alleviated by an intragenic suppressor, which increases the yield of tailspike trimer in both wild-type and tsf constructs (Fane et al., 1991; Mitraki et al., 1991). Cells coinfected with suppressor mutants and tsf mutants only form trimer containing the suppressor chains at restrictive temperatures (Mitraki et al., 1991, 1993) suggest that the suppressor mutation destabilizes the formation of incorrect conformations; however Danner and Seckler (1993) found that monomer folding rates, as determined by fluorescence, are improved in the suppressor mutants, signifying that the suppressor acts by facilitating the formation of on-pathway monomer rather than by destabilizing aggregation reactions. Ultimately, though, the suppressor mutation is acting at a step before chain associations.

Combining the suppressor mutation V331A with the C-terminal cysteine mutants does not result in increased trimer expression levels (Danek and Robinson, unpublished results), lending further evidence that the folding defect of the cysteine mutations occurs during productive assembly past the monomer collapse. The choice of pathway through which the tailspike chain will transition appears to occur before the cysteine interactions are important. Several observations support this theory: first, unlike previously characterized tsf mutants, the C-terminal cysteine mutants do not have an increased partitioning to the aggregation pathway; and second, their folding intermediates persist at extremely long times without participating in higher-order aggregation reactions. These observations suggest that there is limited interaction between the folding and aggregation pathways at higher-order species.

Folding competent intermediates are distinct from aggregates

The question arises as to what distinguishes a productive intermediate from an aggregation-prone species. That intermediates on the productive pathway have a diminished capability to participate in aggregation reactions suggests that particular conformations or structural motifs may define them as folding competent and thus limit their ability to aggregate. One possibility to explain conformational differences between folding intermediates and aggregation species could be the formation of disulfide bonds. There are no disulfide bonds in tailspike aggregates (Speed et al., 1995); however, disulfide bonds have been found in the protrimer (Robinson and King, 1997), dimer (Betts and King, 1998), as well as the monomer (these results).

The connectivity of the disulfide linkages is not known. In native gels, the monomer species has a faster mobility, and therefore smaller apparent radius, in the absence of reducing agent. One consistent model is that a C-terminal cysteine at C613 or C635 forms a disulfide linkage with a cysteine in the main body of the protein at C496, leading to a more compact conformation. Large hydrophobic patches present in the C-terminus have been suggested to be driving forces in assembly (Gage and Robinson, 2003), and the burial of these residues within the monomer could direct conformational changes necessary to bring the two residues in the C-terminal β-prism within bonding proximity of the main body of the tailspike chain. The conformational differences seen on native gels between wild-type folding intermediates and those of the C-terminal cysteine mutants may be explained by less tightly buried configurations formed in the absence of wild-type disulfide bonds.

Flexibility of folding intermediate conformations

Cysteines 613 and 635 play important roles in chain association; however, these roles appear to be partially redundant as single mutants at these sites only decrease but do not prevent trimer formation. The loss of any assembly of the C613S/C635S and C496S/C613S/C635S mutants and the severely reduced expression yields of C496S/C613S and C496S/C635S are much greater than expected from the additive effects of the single mutants, indicating there are likely to be pairwise interactions between these cysteine residues.

It is possible that some flexibility in the conformations or states of the folding intermediates exists, as native trimer can be formed in the absence of each of the single cysteine residues, and in the case of the C496S/C613S and C496S/C635S mutants, with only the 613 or 635 cysteine present, albeit at severely reduced rates and yields. Cold temperature incubation enhanced on-pathway dimer and protrimer formation for wild-type tailspike (Betts and King, 1998). For the serine variants, dimeric intermediates predominate after ice incubation, and the trimeric intermediates dissociate to monomers in the presence of reducing agent (Fig. 7). This indicates that serine variants do not form the same trimeric intermediate as wild-type (protrimer) and may suggest an alternate pathway for native trimer formation in the mutants. The interchain disulfide-linked protrimer that has previously been characterized for wild-type folding (Goldenberg and King, 1982; Benton et al., 2002) may represent an intermediate that is kinetically and thermodynamically favored in the presence of all C-terminal cysteine residues. However, upon removal of any of these critical residues, this intermediate may be unable to form, and an alternate, albeit less efficient route, predominates.

Ultimately, identification of disulfide bond partners and electron acceptors and donors will clarify the roles of the C-terminal cysteines. These challenging experiments are currently under way.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank C. Robinson and B. Lefebvre for many helpful discussions, J. King and C. Haase-Pettingell for assistance in the radioactive protein preparations, D. Ungerbuehler for help with the double mutant characterization, and E. Antipov for assistance with construction and expression of several mutants.

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01 GM-60543 and NIH T32 GM-08550 (B.L.D.)).

Abbreviations used: AMP, ampicillin; LB, Luria broth; IPTG, isopropyl beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside; DTT, dithiothreitol; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; PAGE, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; IAM, iodoacetamide; tsf, temperature-sensitive folding mutants; GdnHCl, guanidine hydrochloride; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, disodium salt; Tris, tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane chloride.

References

- Benton, C. B., J. A. King, and P. L. Clark. 2002. Characterization of the protrimer intermediate in the folding pathway of the interdigitated beta-helix tailspike protein. Biochemistry. 41:5093–5103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts, S., and J. A. King. 1998. Cold rescue of the thermolabile tailspike intermediate at the junction between productive folding and off-pathway aggregation. Protein Sci. 7:1516–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danner, M., and R. Seckler. 1993. Mechanism of phage P22 tailspike protein folding mutations. Protein Sci. 2:1869–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fane, B., R. Villafane, et al. 1991. Identification of global suppressors for temperature-sensitive folding mutations of the P22 tailspike protein. J. Biol. Chem. 266:11640–11648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage, M., and A. S. Robinson. 2003. C-terminal hydrophobic interactions play a critical role in oligomeric assembly of the P22 tailspike trimmer. Protein Sci. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, H. F. 1990. Molecular and cellular aspects of thiol-disulfide exchange. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 63:69–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, D., P. B. Berget, and J. King. 1982. Maturation of the tail spike endorhamnosidase of Salmonella phage P22. J. Biol. Chem. 257:7864–7871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, D., and J. A. King. 1982. Trimeric intermediate in the in vivo folding and subunit assembly of the tail spike endorhamnosidase of bacteriophage P22. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 79:3403–3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, D., D. H. Smith, et al. 1983. Genetic analysis of the folding pathway for the tail spike phage P22. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 80:7060–7064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase-Pettingell, C., S. Betts, et al. 2001. Role for cysteine residues in the in vivo folding and assembly of the phage P22 tailspike. Protein Sci. 10:397–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, J. A., and M.-H. Yu. 1986. Mutational analysis of protein folding pathway using the P22 tailspike endorhamnosidase. Methods Enzymol. 131:250–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, B. G., and A. S. Robinson. 2003. Pressure treatment of tailspike aggregates rapidly produces on-pathway folding intermediates. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 82:595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, P. P., A. Nakanishi, et al. 2002. Formation of transitory intrachain and interchain disulfide bonds accompanies the folding and oligomerization of simian virus 40 Vp1 in the cytoplasm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:1353–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitraki, A., M. Danner, et al. 1993. Temperature-sensitive mutations and second-site suppressor substitutions affect folding of the P22 tailspike protein in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 268:20071–20075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitraki, A., B. Fane, et al. 1991. Global suppression of protein folding defects and inclusion body formation. Science. 253:54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raso, S. W., P. L. Clark, C. Haase-Pettingell, J. King, G. J. Thomas, Jr. 2001. Distinct cysteine sulfhydryl environments detected by analysis of Raman S-H markers of Cys–>Ser mutant proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 307:899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, A. S., and J. A. King. 1997. Disulphide-bonded intermediate on the folding and assembly pathway of a non-disulphide bonded protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, et al. 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Sargent, D., J. M. Benevides, M. H. Yu, J. King, G. J. Thomas, Jr. 1988. Secondary structure and thermostability of the phage P22 tailspike. XX. Analysis of Raman spectroscopy of the wild-type protein and a temperature-sensitive folding mutant. J. Mol. Biol. 199:491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sather, S., and J. A. King. 1994. Intracellular trapping of a cytoplasmic folding intermediate of the phage P22 tailspike using iodoacetamide. J. Biol. Chem. 269:25268–25276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seckler, R., A. Fuchs, et al. 1989. Reconstitution of the thermostable trimeric phage P22 tailspike protein from denatured chains in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 264:11750–11753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed, M. A., T. Morshead, et al. 1997. Conformation of P22 tailspike folding and aggregation intermediates probed by monoclonal antibodies. Protein Sci. 6:99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed, M. A., D. I. C. Wang, et al. 1995. Multimeric intermediates in the pathway to the aggregated inclusion body state for P22 tailspike polypeptide chains. Protein Sci. 4:900–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbacher, S., R. Seckler, et al. 1994. Crystal structure of P22 tailspike protein: interdigitated subunits in a thermostable trimer. Science. 265:383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, J. C. 1993. Electroporation: a general phenomenon for manipulating cells and tissues. J. Cell. Biochem. 51:426–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y., and D. B. Wetlaufer. 1996. Control of aggregation in protein refolding: the temperature-leap tactic. Protein Sci. 5:517–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]