Abstract

Homotetrameric proteins can assemble by several different pathways, but have only been observed to use one, in which two monomers associate to form a homodimer, and then two homodimers associate to form a homotetramer. To determine why this pathway should be so uniformly dominant, we have modeled the kinetics of tetramerization for the possible pathways as a function of the rate constants for each step. We have found that competition with the other pathways, in which homotetramers can be formed either by the association of two different types of homodimers or by the successive addition of monomers to homodimers and homotrimers, can cause substantial amounts of protein to be trapped as intermediates of the assembly pathway. We propose that this could lead to undesirable consequences for an organism, and that selective pressure may have caused homotetrameric proteins to evolve to assemble by a single pathway.

INTRODUCTION

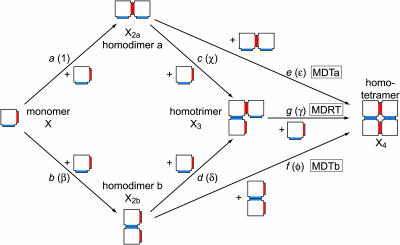

Many proteins must be homotetrameric to be functional. Prominent examples include transcription factors (e.g., p53) (Friedman et al., 1993), transport proteins (e.g., transthyretin) (Blake et al., 1974), potassium channels (Deutsch, 2002; Miller, 2000), water channels (Fujiyoshi et al., 2002), and many enzymes (e.g., the catalases (Zamocky and Koller, 1999), several dehydrogenases (Adams et al., 1970; Au et al., 1999; Buehner et al., 1974; Esposito et al., 2002; Kim et al., 1993; Ramaswamy et al., 1994), phosphofructokinase (Rypniewski and Evans, 1989), and phosphoglycerate mutase (Campbell et al., 1974), among others). In fact, it has been reported that ∼17% of the proteins from Escherichia coli in the SWISS-PROT database are homotetramers (Goodsell and Olson, 2000). There has consequently been great interest in the mechanism of homotetramer formation, but the assembly kinetics of homotetramers are more complicated than those of homodimers or homotrimers because tetramerization can occur by several different pathways. For homotetramers that are “dimers of dimers”, that is, those that have two distinct interfaces, the possibilities (ignoring any unimolecular folding or reorganization steps) are illustrated in Fig. 1. Starting from monomer (X), the first step involves the formation of one of the two possible homodimers, denoted “a” and “b” in Fig. 1 (X2a or X2b). The second step can proceed in two ways: by association with a second homodimer to yield the homotetramer (X4) or by association with a monomer to yield the homotrimer (X3). The reaction is complete in the former case, but in the latter case another monomer must be added to form the homotetramer. The pathways that include only monomers, homodimers, and homotetramers will be denoted MDTa and MDTb, where “MDT” stands for monomer-dimer-tetramer and “a” and “b” indicate the type of homodimer formed. The pathways that include monomers, homodimers, homotrimers, and homotetramers will be denoted MDRT, which stands for monomer-dimer-trimer-tetramer. The italicized lower case letters (a–g) next to the arrows in Fig. 1 are the association rate constants. The Greek letters next to the association rate constants are the rate constants relative to a, the rate constant for the formation of dimer a from two monomers (β = b/a, etc.).

FIGURE 1.

Pathways for the assembly of a “dimer-of-dimers”-type homotetramer. The two types of interfaces along which interactions can occur are indicated in red and blue. Assembly begins with a monomer (X), which dimerizes in one of two ways: along the red interface to form homodimer a (X2a) or along the blue interface to form homodimer b (X2b). These homodimers can then associate to form the homotetramer (X4), or they can successively add two monomers to form the homotrimer (X3), then the homotetramer. The pathway that proceeds from monomer to homodimer a to the homotetramer is the MDTa pathway, the one that proceeds from monomer to homodimer b to the homotetramer is the MDTb pathway, and the one the proceeds from monomer to homodimer a or b to homotrimer to homotetramer is the MDRT pathway. The italicized letters next to the arrows (a–g) are the rate constants for the corresponding steps. The Greek letters in parentheses are the rate constants relative to a (for example, β = b/a, χ = c/a, and so on).

Mechanistic studies of homotetramer formation have been carried out for many proteins (Jaenicke, 1987; Jaenicke and Lilie, 2000), including dihydrofolate reductase (Bodenreider et al., 2002), the potassium channel Kv1.3 (Tu and Deutsch, 1999), p53 (Mateu et al., 1999), β-galactosidase (Nichtl et al., 1998), pyruvate oxidase (Risse et al., 1992), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Rehaber and Jaenicke, 1992), human platelet factor 4 (Chen and Mayo, 1991), phosphofructokinase (Bras et al., 1989; Deville-Bonne et al., 1989; Martel and Garel, 1984; Teschner and Garel, 1989), phosphoglycerate mutase (Hermann et al., 1985, 1983b), and especially lactate dehydrogenase (Bernhardt et al., 1981; Girg et al., 1983; Hermann et al., 1983a, 1981, 1982; Jaenicke, 1974; Rudolph et al., 1977, 1979; Rudolph and Jaenicke 1976; Tenenbaum-Bayer and Levitzki, 1976; Zettlmeissl et al., 1979). All of the proteins listed above have been found to assemble by a single MDT pathway; that is, only one type of homodimer has ever been found to be on the tetramerization pathway, and kinetically significant amounts of homotrimer have never been observed, excluding the possibility of an MDRT mechanism (Jaenicke, 1987; Jaenicke and Lilie, 2000). To our knowledge, no homotetrameric protein has yet been found to assemble by an MDRT mechanism. Thus, despite there being several tetramerization mechanisms that could proceed in parallel, homotetramers seem to assemble exclusively by a single MDT pathway. This raises several questions about why this should be. Is the MDT mechanism inherently more efficient than the MDRT mechanism? That is, given comparable association rate constants for these two types of mechanisms, will the MDT mechanism always outcompete the MDRT mechanism? On the other hand, could homotetrameric proteins have actually evolved to assemble by MDT mechanisms? Finally, why is competition between the two different MDT pathways not observed? To improve our understanding of the fundamentals of protein assembly, we address these questions in this report by modeling homotetramer formation as a function of the rate constants a, b, c, d, e, f, and g.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Numerical integration of differential equations and other calculations were performed on a personal computer with dual AMD Athlon 2200 MP processors using Mathematica 4.2 (Wolfram Research, Champaign, Illinois) for Windows XP.

RESULTS

We are primarily interested in proteins for which tetramerization is favorable, even at submicromolar concentrations. The scheme shown in Fig. 1 is therefore applicable only to homotetrameric proteins in which the interactions along both interfaces are strong enough for each association step to be irreversible. In addition, to make the system tractable, we assume that there are no kinetically significant, unimolecular folding or reorganization steps. For example, when tetramerization is initiated from the completely unfolded and monomeric state of the protein (often by dilution from high concentrations of urea or guanidinium hydrochloride), then the scheme in Fig. 1 would only be appropriate if folding of the protein to form structured monomers were fast enough relative to association to make it kinetically insignificant. This is often true when protein association is relatively slow (at low protein concentrations) (Jaenicke, 1987), although proline isomerization can sometimes cause folding to be slow enough that it cannot be disregarded (Bodenreider et al., 2002). Unimolecular reorganization or folding of the protein after dimer-, trimer- or tetramerization must also be fast relative to association. Although such reorganization steps have sometimes been observed experimentally, their importance is also minimized at low protein concentration (Jaenicke, 1987; Schreiber, 2002).

The rate equations that define the kinetics of the system are:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

where the brackets indicate the molar concentration of the enclosed species and t is time in seconds. Conservation of mass dictates that

|

(6) |

where [X]tot is the total concentration of protein subunits. Since we are concerned with homotetramer assembly starting from a pool of monomer, the initial conditions are

|

(7) |

We have found the following transformations to be convenient:

|

Thus, the new concentration variables are the mole fractions of protein occupying a given oligomerization state. It is also useful to change the time variable to τ = t×a×[X]tot. Because the units of t are s, those of [X]tot are M, and those of a are M−1 s−1, the new time variable, τ, is dimensionless. With the transformed variables, Eqs. 1–5 become

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

where, as indicated in Fig. 1, the lowercase Greek letters are dimensionless, relative rate constants: β = b/a, χ = c/a, δ = d/a, ɛ = e/a, φ = f/a, and γ = g/a. The expression for mass conservation in terms of these variables is

|

(13) |

and the initial conditions are

|

(14) |

The total protein concentration does not appear in the transformed rate equations, the conservation law, or the initial conditions. Thus, concentration affects only the timescale of the reaction and not the shape of the reaction profile. The same is true of the magnitudes of the rate constants; only their relative values are important in determining the course of the reaction. Concentration independence of association kinetics after transformation of the concentration and time variables as suggested above can be observed in any associating system in which each step is both bimolecular and irreversible, from colloidal aggregation (Galina and Lechowicz, 1998) to the aggregation of phosphoglycerate kinase (Modler et al., 2003).

Before addressing the complete system illustrated in Fig. 1 and described by Eqs. 8–14, some limiting cases will be examined.

Case 1: Tetramerization through a single MDT pathway; β = χ = δ = φ = γ = 0

When all of the relative rate constants except ɛ are set to zero, the rate equations, conservation of mass, and initial conditions become

|

(15) |

|

(16) |

|

(17) |

|

(18) |

|

(19) |

Inspection of the rate equations reveals that steady state (where the time derivatives of x, x2a, and x4 are all 0) can be reached only when both x and x2a are 0, which, according to mass conservation, also implies that all of the protein must be homotetrameric (x4 = 1).

Sets of nonlinear differential equations cannot usually be solved. However, Eqs. 15–17 are an exception. The solutions, first derived by Chien (1948), are

|

(20) |

|

(21) |

|

(22) |

where  and

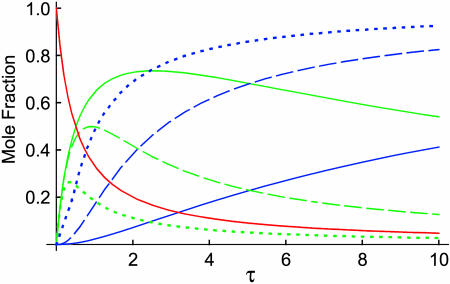

and  These solutions are plotted in Fig. 2 for several values of ɛ. This parameter does not affect the time dependence of x (the mole fraction of monomer), as is evident from Eq. 20 and from Fig. 2, in which a single red curve represents the disappearance of monomer at all values of ɛ. It does, however, affect the time dependencies of x2a and x4. The amount of homodimer that builds up (and the corresponding lag in homotetramer formation) decreases as the relative rate constant for homotetramer formation, ɛ, increases. Thus, when ɛ is 0.1, x2a reaches a maximum of 0.74 and x4 does not reach 0.1 until τ = 2.5, but when ɛ is 10, the maximum value of x2a is only 0.26 and x4 reaches 0.1 when τ = 0.3. As noted above, however, all of the protein eventually becomes homotetramer no matter what the value of ɛ is (x4 → 1 as τ → ∞).

These solutions are plotted in Fig. 2 for several values of ɛ. This parameter does not affect the time dependence of x (the mole fraction of monomer), as is evident from Eq. 20 and from Fig. 2, in which a single red curve represents the disappearance of monomer at all values of ɛ. It does, however, affect the time dependencies of x2a and x4. The amount of homodimer that builds up (and the corresponding lag in homotetramer formation) decreases as the relative rate constant for homotetramer formation, ɛ, increases. Thus, when ɛ is 0.1, x2a reaches a maximum of 0.74 and x4 does not reach 0.1 until τ = 2.5, but when ɛ is 10, the maximum value of x2a is only 0.26 and x4 reaches 0.1 when τ = 0.3. As noted above, however, all of the protein eventually becomes homotetramer no matter what the value of ɛ is (x4 → 1 as τ → ∞).

FIGURE 2.

Plots of x, x2a and x4 as a function of τ at three different values of ɛ for case 1, in which tetramerization proceeds through a single MDT pathway. The single, solid red line corresponds to x, the time dependence of which does not change with ɛ. The three green lines represent x2a at ɛ = 0.1 (solid), 1 (dashed), and 10 (dotted). The three blue lines represent x4 at ɛ = 0.1 (solid), 1 (dashed), and 10 (dotted).

Case 2: Tetramerization through competing MDT pathways; χ = δ = γ = 0

Setting χ, δ, and γ equal to 0 reflects the case in which the dimerization pathways can compete with one another. The rate equations, conservation of mass, and initial conditions are

|

(23) |

|

(24) |

|

(25) |

|

(26) |

|

(27) |

|

(28) |

Again, inspection of Eqs. 23–26 shows that steady state can be reached only when x, x2a, and x2b are all 0, that is, when all of the protein is homotetrameric (x4 = 1).

These equations are similar to Eqs. 15–19, whose solutions were given above. For example, replacing the factor −2 in Eq. 15 with −2(1 + β) yields Eq. 23. The solution for x is therefore

|

(29) |

The availability of a second pathway causes the rate of disappearance of x to increase by a factor of 1 + β but does not change its hyperbolic dependence on τ. Equations 24 and 25 have the same form as Eq. 16. They can therefore be solved by the same method, yielding

|

(30) |

where  and

and  and

and

|

(31) |

where  and

and  The solution for x4 can then be obtained by rearranging Eq. 27:

The solution for x4 can then be obtained by rearranging Eq. 27:

|

(32) |

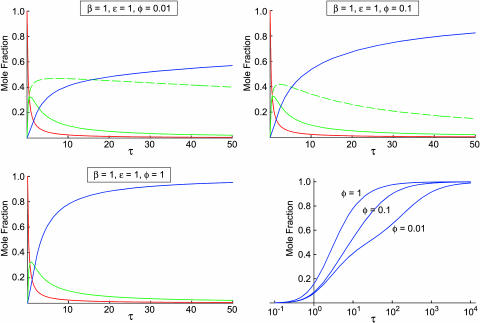

where x, x2a, and x2b are as given in Eqs. 29–31. These solutions can be used to understand how tetramerization progresses when two different MDT-type pathways operate in parallel. For example, the solutions show that tetramerization can be distinctly biphasic when the tetramerization rate constants (ɛ and φ) for the two pathways are very different, and that a substantial amount of homodimer (temporarily) accumulates in the pathway with the lower tetramerization rate constant. This is illustrated in Fig. 3, where x, x2a, x2b, and x4 are plotted against τ when β = 1, ɛ = 1, and φ = 0.01 (upper left), 0.1 (upper right) or 1 (lower left). The time dependence of x4 for the various values of φ is also shown in the lower right-hand panel of Fig. 3 with τ on a logarithmic scale to emphasize the biphasic accumulation of homotetramer, and to show that x4 → 1 as τ → ∞ for all three values of φ.

FIGURE 3.

Plots of x, x2a, x2b, and x4 as a function of τ at β = 1, ɛ = 1, and φ = 0.01 (upper left), 0.1 (upper right), and 1 (lower left) for case 2, in which the MDTa and MDTb pathways compete with each other. In these three plots, the solid red line represents x, the solid green line represents x2a, the dashed green line represents x2b, and the solid blue line represents x4 (note that the curves for x2a and x2b overlay when φ = 1, so they are represented by a single green line). The plot in the lower right shows x4 versus τ at φ = 0.01, 0.1, and 1 with τ on a logarithmic scale.

The solutions found above, though useful, are not informative as to how much each pathway contributes to the total amount of homotetramer formed when the reaction is complete. The contributions from each pathway can be separated and quantified by noting that, according to Eq. 26,

|

(33) |

The contributions from the MDTa and MDTb pathways, x4a and x4b respectively, are

|

(34) |

These expressions cannot be integrated directly, but explicit solutions for x4a and x4b can still be found as shown in the Appendix. They are

|

(35) |

|

(36) |

where μ1, μ2, ν1, and ν2 are as defined above. The values of x4a and x4b as τ → ∞, which represent the amount of homotetramer formed through each MDT pathway, are 1/(1 + β) and β/(1 + β), respectively. Thus, the contributions of the two pathways depend purely on β, the relative rate constant of dimerization. When β is small, the formation of homodimer b is relatively slow, and tetramerization occurs almost exclusively through the MDTa pathway (x4a → 1, x4b → 0). When β is large, the formation of homodimer b is relatively fast, and tetramerization occurs almost exclusively through the MDTb pathway (x4a → 0, x4b → 1). This is intuitively satisfying; since reverse reactions have been neglected, dimerization irreversibly commits material to one pathway or the other, and the contribution of each pathway should therefore depend only on the relative rates of dimerization.

Case 3: Tetramerization through an MDRT pathway; β = δ = ɛ = φ = 0

Setting β, δ, ɛ, and φ to 0 eliminates all of the terms in Eqs. 8–12 in which the mole fraction of monomer, x, does not occur. Since x is a multiplier in every remaining term, the rate equations can be simplified by another transformation of the time variable. Let

|

(37) |

Variables like s are known as concentration-time integrals (Saville, 1971). Under this transformation, ds = x dτ and the rate equations become

|

(38) |

|

(39) |

|

(40) |

|

(41) |

The conservation of mass and initial conditions are

|

(42) |

|

(43) |

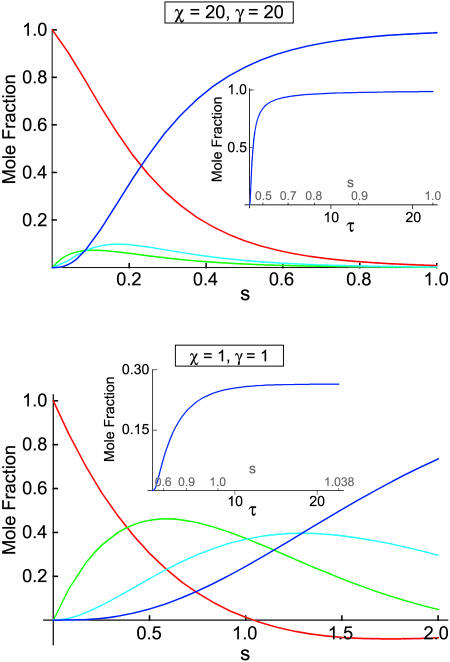

Before transformation of τ, the rate equations for assembly would not have been analytically solvable. Transformation of τ according to Eq. 37, however, converts Eqs. 38–41 to a linear, homogeneous system of differential equations with constant coefficients. A solution in terms of the parameters χ and γ could now be found in principle, but it would be exceedingly complicated. Therefore, we present two examples at particular values of χ and γ to illustrate how this system behaves. First, let χ = γ = 20, so that both tri- and tetramerization are fast relative to dimerization. The solutions, shown below, are simple sums of exponentials (because the system's eigenvalues and all of the components of its eigenvectors are real):

|

(44) |

|

(45) |

|

(46) |

|

(47) |

These solutions are plotted in the upper panel of Fig. 4, which shows that x4 → 1, and x, x2a, and x3 → 0 as s, and therefore τ, approaches infinity. The inset shows the plot for x4 as a function of τ with the corresponding values of s shown in gray. The dependence on τ was obtained by inverting Eq. 37:

|

(48) |

FIGURE 4.

Plots of x (red), x2a (green), x3 (cyan), and x4 (blue) as a function of s, the concentration-time integral, at χ = γ = 20 (upper panel) and χ = γ = 1 (lower panel) for case 3, in which tetramerization proceeds exclusively through the MDRT pathway. The insets show the plots of x4 as a function of τ with the corresponding values of s in gray. Note that in the lower plot, x crosses the abscissa at s ≈ 1.04. The meaning of this is discussed in the text.

For the second example, let χ = γ = 1, so that the formation of homodimers, homotrimers, and homotetramers all have the same rate constants. In this case, the solutions are not simple sums of exponentials; they have periodic components (because the system of equations has eigenvalues that are complex numbers):

|

(49) |

|

(50) |

|

(51) |

|

(52) |

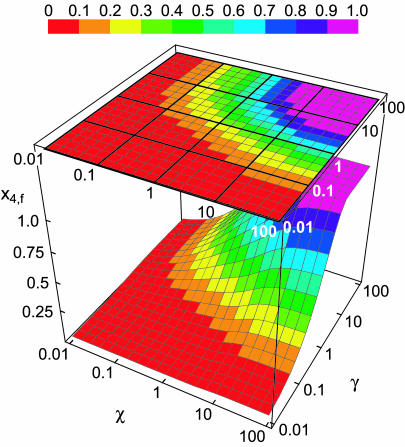

The plot of these solutions in the lower panel of Fig. 4 has a noteworthy feature: the value of x crosses the abscissa at s ≈ 1.04 and becomes negative. According to Eq. 48, τ must approach infinity as x approaches 0. The reaction must therefore end at s ≈ 1.04 and the solutions for s > 1.04 have no physical meaning. At s ≈ 1.04, x4 still has not reached 1 and x2a and x3 have not reached 0. This is also apparent in the inset, in which the time variable is converted back to τ. The homotetramer is not the exclusive product of the reaction despite all of the steps leading to it being irreversible. This happens because of something that is hidden by the use of the concentration-time integral. As noted above, when β, δ, ɛ, and φ are all 0, the remaining nonzero terms in Eqs. 8–12 are multiplied by x. This means that steady state can be achieved when x = 0, regardless of the values of x2a, x3, or x4. In the case examined here where χ = γ = 1, x rapidly approaches 0, trapping a substantial amount of protein in the homodimer and homotrimer state (x2a,s=1.04 = 0.36, x3,s=1.04 = 0.38). This is by no means an isolated phenomenon, restricted to a few unlikely values of χ and γ. Fig. 5 shows a plot of the final value of x4 (x4,f) as a function of the parameters χ and γ. These were determined by integrating Eqs. 38–43 with values of χ and γ ranging from 0.01 to 100. Tetramerization does not reach completion in large portions of χ, γ space. In fact, tri- and tetramerization must both be relatively fast (χ, γ ≈ 4 or larger) for homotetramers to represent >90% of the product.

FIGURE 5.

A plot of the mole fraction of homotetramer as τ → ∞ as a function of χ and γ when tetramerization can only occur by the MDRT pathway. The colors of the plot specify the value of x4,f according to the key shown in the upper portion of the figure. In addition, the plot is projected onto the χ-, γ-plane above the plot. The heavier gridlines correspond to values of χ or γ increasing from 0.01 by factors of 10, as indicated along the edges of the projection. The lighter gridlines correspond to increases by a factor of ∼1.6 (100.2).

The phenomenon described above is a result of the assumption that each step on the MDRT pathway is irreversible. Strict irreversibility, however, is never attainable in real physical systems. Dissociation will still occur no matter how favorable each monomer addition step is, providing a pool of monomers, though probably at very low concentration, that will allow the system to relax to its predominantly homotetrameric equilibrium state. Indeed, this is not unlike the relaxation of systems of polymerizing proteins (for example, actin or flagellin) to their equilibrium length distributions (Oosawa and Asakura, 1975). The initial depletion of monomers in these systems can occur in only hours, whereas days could be needed to reach the final equilibrium (Oosawa and Asakura, 1975). Likewise, in homotetramer forming systems, the redistribution of protein among the oligomeric states is likely to be slow compared to monomer depletion, trapping protein in incompletely assembled homodimeric and -trimeric states until the system can reach equilibrium (which we have assumed to be overwhelmingly dominated by homotetramers).

Competition among MDTa, MDTb, and MDRT pathways for tetramerization

The preceding examination of limiting cases has revealed the following: 1), that accumulation of homodimer in MDT mechanisms requires that tetramerization be slow relative to dimerization; 2), that tetramerization can proceed in two distinct phases, and at least one type of homodimer can accumulate, when the MDTa and MDTb pathways compete and the two tetramerization rate constants (ɛ and φ) are very different; 3), that the partitioning of protein between the MDTa and MDTb pathways depends only on the relative rate of dimerization; and 4), that protein can be trapped in incompletely assembled states when tetramerization takes place through the MDRT mechanism, unless χ and γ are both large. To answer the questions posed at the end of the Introduction, we will now examine the problem, described by Eqs. 8–14, when the MDTa, MDTb, and MDRT mechanisms can all proceed in parallel. In particular, we will try to define conditions under which tetramerization proceeds exclusively by a single MDT mechanism.

Equations 8–14 have six relative rate constants (β, χ, δ, ɛ, φ, and γ), which makes their direct analysis complicated. The problem can be simplified by making some assumptions about the values of the rate constants. The addition of monomer to homodimer a to form homotrimer and the addition of monomer to monomer to form homodimer b involve association along the same interface (the blue interface in Fig. 1). The rate constants for these processes should therefore be similar, and we will assume that β = χ. By analogy, we will assume that the addition of monomer to homodimer b to form homotrimer and monomer to monomer to form homodimer a also have the same rate constants, so δ = 1. Substituting β for χ and 1 for δ in Eqs. 8–12 reduces the number of rate constants to four (β, ɛ, φ, and γ):

|

(53) |

|

(54) |

|

(55) |

|

(56) |

|

(57) |

This assumption does not affect the mass balance or the initial conditions, which are represented by Eqs. 13 or 14, respectively. The problem can be further constrained by noting that protein-protein association rates generally fall in the range from 104 M−1 s−1 to 106 M−1 s−1 (Schreiber, 2002). It will therefore be assumed that the rate constants for any step are no more than 100 times more or less than a, the (absolute) rate constant for the formation of homodimer a. Thus, 0.01 ≤ β, ɛ, φ, γ ≤ 100.

Answering the questions from the introduction requires that the contributions from the MDTa, MDTb, and MDRT pathways to the total amount of homotetramer formed at the end of the reaction be determined as functions of the relative rate constants. The contributions from the three pathways can be separated by noting that, according to Eq. 57,

|

(58) |

Thus,

|

(59) |

where x4,f is the final mole fraction of homotetramer formed through all pathways combined, and x4a,f, x4b,f, and x4r,f are the final mole fractions of homotetramer formed through the MDTa, MDTb, and MDRT pathways, respectively.

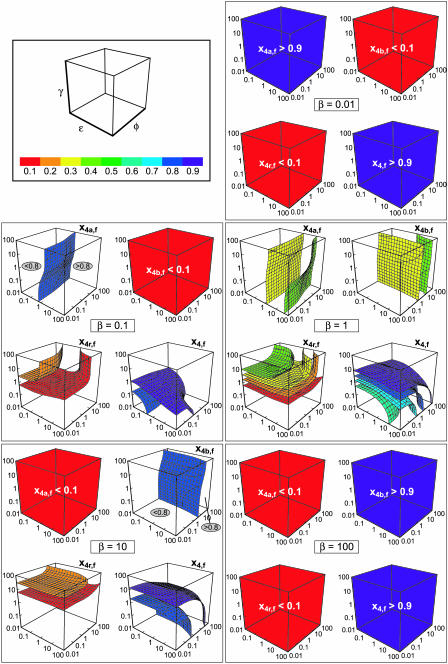

Equations 53–57 and 13 and 14 cannot be solved explicitly, and must therefore be numerically integrated. To determine the dependence of x4a,f, x4b,f, x4r,f, and x4,f on the relative rate constants, numerical solutions were obtained to very large values of τ (τ = 108) for combinations of β, ɛ, φ, and γ, where each was allowed to vary from 0.01 to 100 by factors of 100.5 (∼3.2). Thus, solutions were obtained for 6561 combinations of β, ɛ, φ, and γ, and the results for β = 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10. and 100 are shown in Fig. 6 (the plots for β = 0.032, 0.32, 3.2. and 32 are omitted for clarity). The five groups of plots in Fig. 6 show the contour surfaces of x4a,f, x4b,f, x4r,f, and x4,f in the three-dimensional space defined by ɛ, φ, and γ. Each contour represents the interpolated surface of ɛ, φ, and γ values on which x4a,f, x4b,f, x4r,f, or x4,f has a particular fixed value. The color of the surface indicates the value according to the key shown in the first panel of Fig. 6. As mentioned above, the groups of plots in Fig. 6 have one plot each for x4a,f, x4b,f, and x4r,f. There is also a plot for x4,f, the mole fraction of homotetramer that forms from all of the pathways combined. Because all of the steps are irreversible, one might expect that x4,f should always be 1, independent of the values of β, ɛ, φ, and γ. However, as was observed for case 3 (where the MDRT pathway was considered by itself), protein assembling through the MDRT pathway can be trapped as homodimer or -trimer before becoming homotetrameric. Indeed, inspection of Eqs. 53–57 reveals that steady state can be achieved when x, x2a, and x2b are all 0. It is thus possible that x3 can be nonzero and x4 < 1 at the end of the reaction, representing the situation where protein is trapped as homotrimer.

FIGURE 6.

Three-dimensional contour plots of the total amounts of homotetramer formed through the MDTa pathway (x4a,f), the MDTb pathway (x4b,f), the MDRT pathway (x4r,f), and all three pathways combined (x4,f) when all of the pathways compete with each other for values of β between 0.01 and 100. Each contour represents a surface on which x4a,f, x4b,f, x4r,f, or x4,f is constant in the space defined by the values of ɛ, φ, and γ at a particular value of β (the value of β is shown in the center of each group of five plots) The colors of the contours indicate the values of x4a,f, x4b,f, x4r,f, and x4,f according to the key in the first panel of the figure. The plots that are filled with a single, solid color indicate that the mole fraction of interest is either <0.1 (red) or >0.9 (violet) at all values of ɛ, φ, and γ. For plots that have only one contour, the value on either side of the contour is indicated in a gray ellipse. Note that the total amount of homotetramer formed at the end of the assembly reaction (x4,f) can be <1, even though each individual step has been assumed to be irreversible, because protein can be trapped as homotrimer (see text for a discussion).

Some features of the kinetics of the full system stand out after an inspection of Fig. 6. At very low and very high values of β (β = 0.01 or β = 100), a single MDT mechanism dominates the formation of homotetramer. Almost all of the protein becomes homotetrameric through the MDTa pathway when β is small, or through the MDTb pathway when β is large. This can be understood in terms of the preceding examination of case 2 (where the MDTa and MDTb pathways compete). There it was found that the value of β directly determined the amount of homotetramer formed through each pathway because the dimerization step irreversibly committed protein to one pathway or the other. When β was small, most of the protein assembled through the MDTa pathway; when β was large, most of the protein assembled through the MDTb pathway. The same is true here, but in addition we note that small or large values of β suppress the MDRT pathway. Since it has been assumed that β = χ, the rate of homotrimer formation by addition of monomer to homodimer a is also slow when β is small, thus disfavoring the MDRT pathway. Even when homotetramer formation from homodimer a is slow (ɛ is small), monomer is consumed so rapidly by dimerization that none remains to make homotrimer by addition to homodimer a. The only path left available to homodimer a is tetramerization by the MDTa mechanism. By analogy, the MDTb pathway is overwhelmingly favored when β is large.

The behavior of the system is more complicated when the value of β is neither small nor large. For example, all of the pathways can make substantial contributions to the total amount of homotetramer formed when β = 1, depending on the values of ɛ, φ, and γ. The plot of x4a,f shows that the contribution from the MDTa pathway varies from under 30% to over 40% (0.2 < x4a,f < 0.5). The contours show that ɛ has the strongest influence on x4a,f. This should be expected, since ɛ is the relative rate constant for one of the steps on the MDTa pathway (homotetramer formation from homodimer a). In contrast, the other two relative rate constants, φ and γ, have much weaker effects on x4a,f. This can be rationalized by noting that the steps to which these rate constants correspond are neither on nor in direct competition with the MDTa pathway. Analogous observations can be made on the plot of x4b,f for β = 1: φ is the most influential rate constant in this case, whereas the effects of ɛ and γ are small by comparison.

The plot of x4r,f for β = 1 shows that the contribution of the MDRT pathway to homotetramer formation can vary from under 10% to over 40% (0 < x4r,f < 0.5), again depending on ɛ, φ, and γ. For large values of γ (above the red contour), x4r,f is largest when ɛ and φ are both small. This occurs because slow homodimer-homodimer association rates (small values of ɛ and φ) cause both homodimer a and b to accumulate, which gives them the opportunity to enter the MDRT pathway by associating with monomer to form homotrimer. Large values of γ then guarantee that the homotrimer will go on to form homotetramer. On the other hand, when ɛ and φ are both large, neither type of homodimer accumulates, and the MDRT mechanism is suppressed; in fact, x4r,f is held to <0.2 when ɛ = φ = 100. This is expected based on the results of case 1, where it was found that the extent and duration of homodimer accumulation decreased as the rate constant for homotetramer formation increased. When either ɛ or φ is large whereas the other is small, an intermediate situation is observed. The formation of homotrimer, and thus access to the MDRT pathway, is suppressed for one homodimer (the one with the large tetramerization rate constant), whereas it is promoted for the other homodimer. This effect is related to the biphasic homotetramer formation noted in case 2, but here the slow-associating homodimer is diverted to the MDRT pathway instead of slowly forming homotetramer. For small values of γ (below the red contour in the plot of x4r,f for β = 1), the contribution of the MDRT mechanism to homotetramer formation is small (x4r,f < 0.1). Instead, large amounts of protein become trapped as homotrimer. This is evident in the plot of x4,f for β = 1, from which it is apparent that x4,f can be <0.6, and therefore that x3 can be >0.4, at the end of the reaction. The amount of protein trapped as homotrimer at a given value of γ is largest when ɛ and φ are both small, smallest when they are both large, and intermediate when one is small and one is large.

The information in Fig. 6 can be summarized as follows. The contribution of the MDTa pathway to the total amount of homotetramer formed, represented by x4a,f, is largest when β is small (<0.1). Its contribution rapidly decreases as β increases, becoming <0.1 at all values of ɛ, φ, and γ when β ≥ 10. The contribution of the MDTb pathway to the total amount of homotetramer formed shows the opposite behavior, being largest when β is large (>10) and decreasing rapidly as β decreases. The MDTb pathway is negligible when β ≤ 0.1. The contribution of the MDRT pathway is largest when β is close to 1 (0.1 < β < 10), ɛ and φ are both small, and γ is large. Finally, the amount of protein that becomes trapped as homotrimer is largest when β is close to 1 (0.1 < β < 10), ɛ and φ are both small, and γ is small.

DISCUSSION

The preceding results allow us to suggest some answers to the questions raised in the introduction, which were as follows: Given comparable association rate constants for these two types of mechanisms, does the MDT mechanism always outcompete the MDRT mechanism? Could homotetrameric proteins have evolved to assemble by MDT mechanisms? And, why is competition between the two different MDT pathways not observed?

The MDT pathway does not outcompete the MDRT pathway given comparable association rate constants

The plots in Fig. 6 show that similar amounts of homotetramer are produced by all of the available pathways when their rate constants are comparable (β, ɛ, φ, and γ are all close to 1). The inherent efficiency of the pathways cannot, therefore, explain the dominance of the MDT pathway for homotetramer formation. This is consistent with the results of Tu and Deutsch (1999), who studied the competition between the MDT and MDRT pathways in a system related to the one presented here (in their system, the steps preceding tetramerization were allowed to be reversible, but only one type of homodimer was accounted for). They found that the MDT pathway could only be dominant when the rate constants for monomer-monomer and homodimer-homodimer association were large (or when homotrimer was much more likely to revert to monomer and homodimer than it was to add a monomer and become homotetramer).

Homotetrameric proteins may have evolved to favor MDT assembly mechanisms

It has been shown above that the fully formed homotetramer is inevitably the product of the MDT pathway. This is not necessarily true for the MDRT pathway; protein can instead be trapped in intermediate oligomeric states. The presence of such incompletely assembled, improper oligomers could be harmful to an organism. For example, improper oligomers could be susceptible to proteolysis from which the homotetramer was protected. The protein fragments that resulted from this proteolysis could be innocuous, in which case the cost to the organism would only be the energy wasted in synthesizing the protein. There is also a possibility, however, that the presence of the protein fragments could be detrimental. If they were amyloidogenic (prone to forming fibrillar aggregates), their aggregation could be pathogenic. For example, aggregation by the amyloidogenic peptides that result from the proteolysis of the amyloid precursor protein (Hooper et al., 2000; Selkoe, 1998) and gelsolin (an actin modulating protein) (Maury, 1991) are associated with Alzheimer's disease and Finnish hereditary amyloidosis, respectively. Furthermore, improper oligomers themselves could aggregate and lead to disease. These potentially harmful consequences of the accumulation of improper oligomers on the MDRT pathway could have resulted in selective pressure favoring the MDT mechanism for homotetramer assembly.

Competition between MDT pathways is not observed because it would be accompanied by competition with the MDRT pathway

The two possible MDT pathways (MDTa and MDTb in Fig. 1) can only compete when β is close to 1. This situation, however, also favors the MDRT pathway. Thus, it could be that competition between the MDTa and MDTb pathways is not observed because it would always be accompanied by a substantial contribution from the MDRT pathway, the disadvantages of which were noted above.

Strategies for controlling the tetramerization pathway

Given the model for tetramerization proposed above, in which each step is irreversible, χ is set equal to β and δ is set equal to 1, Fig. 6 shows that for a single MDT pathway to dominate homotetramer formation it is sufficient (and necessary) that β be either small (on the order of 0.01) or large (on the order of 100). Formation of one of the two possible homodimers must therefore be much faster than formation of the other. This could be achieved, for example, by optimizing the electrostatic interactions (Schreiber, 2002; Schreiber and Selzer, 1999; Sheinerman et al., 2000) or, to a lesser degree, the desolvation forces (Camacho et al., 2000) at one (and only one) of the interfaces to promote fast association. The relative importance of electrostatics and desolvation to homotetramer formation is difficult to evaluate because, even for homotetramers that are known to assemble by an MDT mechanism, it is not usually known which homodimer is on the assembly pathway. An exception is phosphofructokinase, for which the order in which subunit interfaces form has been determined (Bras et al., 1989; Deville-Bonne et al., 1989; Teschner and Garel, 1989). A detailed calculation and comparison of the electrostatic energies at the two interfaces is beyond the scope of this article, but inspection of the crystal structure (accession no. 2PFK (Rypniewski and Evans, 1989)) does not reveal electrostatic interactions to be obviously more important at one interface than the other. Thus, for phosphofructokinase, it may be desolvation forces that ensure assembly by the MDT pathway. Nonetheless, we note that electrostatics are generally recognized to have a stronger influence on protein-protein association rates than desolvation (Camacho et al., 1999; Janin, 1997; Schreiber, 2002), and that electrostatics probably play an important role in the assembly of other protein homotetramers.

Other ways of suppressing the MDRT pathway become apparent if our assumption that β = χ is relaxed. For example, Mateu et al. (1999) have proposed a model for the assembly of the p53 tetramerization domain in which monomers are initially unfolded, but simultaneously associate and fold to yield a structured homodimer. This homodimer can then go on to form the homotetramer. Because folding is required to create the interface necessary for tetramerization, β and χ would be small (though not necessarily equal to each other), making the MDRT pathway inaccessible. Moreover, if the assumption that all of the association steps are irreversible is relaxed, the MDT mechanism can be enforced if only one of the two possible homodimers is stable enough to form under tetramerization conditions.

The ways listed above that rely on differences between two interfaces to ensure the MDT mechanism for homotetramer formation cannot be used by homotetrameric proteins that have a four-fold (C4) axis of symmetry, because all of the interfaces are identical in such homotetramers. Nevertheless, Kv1.3, a potassium channel that presumably has a C4 axis of symmetry, has been found to assemble by the MDT pathway (Tu and Deutsch, 1999). Our results do not strictly apply to the assembly of C4 symmetrical homotetramers because their symmetry demands that there be only one MDT pathway for homotetramer formation, a possibility not accounted for by the scheme in Fig. 1. Tu and Deutsch, however, have modeled this system (Tu and Deutsch, 1999). To explain why Kv1.3 assembles by an MDT pathway, they have proposed a mechanism in which a conformational change occurs after monomers associate to form homodimers. This yields a homodimer with interfaces that are self-complementary (allowing homotetramer formation) but incompatible with those of the monomer (disfavoring the MDRT pathway). The difference between this mechanism and that proposed for the p53 tetramerization domain is that, in this case, the conformational change must occur in such a way that the C4 symmetry of the final homotetramer can be maintained.

In summary, we have shown that the MDT pathway for protein homotetramer formation is fundamentally different from the MDRT pathway in that all available protein is eventually converted to homotetramer in the MDT pathway, whereas substantial amounts of protein can be trapped as assembly intermediates in the MDRT pathway. We suggest that improper oligomers formed in the MDRT pathway could be vulnerable to aberrant proteolysis, misfolding, and aggregation, and that this may have led to evolutionary pressure favoring the MDT pathway. We believe that this may explain the uniform dominance of the MDT pathway for homotetramer formation.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Deechongkit, C. Esau, A. Hurshman, T. Foss, and J. W. Kelly for helpful discussions.

APPENDIX

To obtain explicit expressions for the contribution of the MDTa pathway in case 2 (tetramerization through competing MDT pathways), we first rearrange Eq. 24:

|

(60) |

This expression for ɛx2a2 can be substituted into Eq. 34:

|

(61) |

Integrating the expressions above yields

|

(62) |

Finally, replacing x2a according to Eq. 30 yields the time dependence for x4a:

|

(63) |

where μ1 and μ2 are as defined above for Eq. 30. This is identical to Eq. 35. The expression for x4b in Eq. 36 can be obtained in an analogous way.

References

- Adams, M. J., G. C. Ford, R. Koekoek, P. J. Lentz, A. McPherson, Jr., M. G. Rossmann, I. E. Smiley, R. W. Schevitz, and A. J. Wonacott. 1970. Structure of lactate dehydrogenase at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 227:1098–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au, S. W., C. E. Naylor, S. Gover, L. Vandeputte-Rutten, D. A. Scopes, P. J. Mason, L. Luzzatto, V. M. Lam, and M. J. Adams. 1999. Solution of the structure of tetrameric human glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase by molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. D. 55:826–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt, G., R. Rudolph, and R. Jaenicke. 1981. Reassociation of lactic dehydrogenase from pig heart studied by cross-linking with glutaraldehyde. Z. Naturforsch. [C]. 36:772–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake, C. C., M. J. Geisow, I. D. Swan, C. Rerat, and B. Rerat. 1974. Structure of human plasma prealbumin at 2.5 Å resolution. A preliminary report on the polypeptide chain conformation, quaternary structure and thyroxine binding. J. Mol. Biol. 88:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenreider, C., N. Kellershohn, M. E. Goldberg, and A. Mejean. 2002. Kinetic analysis of R67 dihydrofolate reductase folding: from the unfolded monomer to the native tetramer. Biochemistry. 41:14988–14999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bras, G. L., W. Teschner, D. Deville-Bonne, and J. R. Garel. 1989. Urea-induced inactivation, dissociation, and unfolding of the allosteric phosphofructokinase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 28:6836–6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehner, M., G. C. Ford, K. W. Olsen, D. Moras, and M. G. Rossman. 1974. Three-dimensional structure of d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J. Mol. Biol. 90:25–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, C. J., S. R. Kimura, C. DeLisi, and S. Vajda. 2000. Kinetics of desolvation-mediated protein-protein binding. Biophys. J. 78:1094–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, C. J., Z. Weng, S. Vajda, and C. DeLisi. 1999. Free energy landscapes of encounter complexes in protein-protein association. Biophys. J. 76:1166–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. W., H. C. Watson, and G. I. Hodgson. 1974. Structure of yeast phosphoglycerate mutase. Nature. 250:301–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. J., and K. H. Mayo. 1991. Human platelet factor 4 subunit association/dissociation thermodynamics and kinetics. Biochemistry. 30:6402–6411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien, J.-Y. 1948. Kinetic analysis of irreversible consecutive reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 70:2256–2261. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, C. 2002. Potassium channel ontogeny. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64:19–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deville-Bonne, D., G. Le Bras, W. Teschner, and J. R. Garel. 1989. Ordered disruption of subunit interfaces during the stepwise reversible dissociation of Escherichia coli phosphofructokinase with KSCN. Biochemistry. 28:1917–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, L., F. Sica, C. A. Raia, A. Giordano, M. Rossi, L. Mazzarella, and A. Zagari. 2002. Crystal structure of the alcohol dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus at 1.85 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 318:463–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, P. N., X. Chen, J. Bargonetti, and C. Prives. 1993. The p53 protein is an unusually shaped tetramer that binds directly to DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90:3319–3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiyoshi, Y., K. Mitsuoka, B. L. de Groot, A. Philippsen, H. Grubmuller, P. Agre, and A. Engel. 2002. Structure and function of water channels. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12:509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galina, H., and J. B. Lechowicz. 1998. Mean-field kinetic modeling of polymerization: the Smoluchowski coagulation equation. Adv. Polym. Sci. 137:135–172. [Google Scholar]

- Girg, R., R. Rudolph, and R. Jaenicke. 1983. The dimeric intermediate on the pathway of reconstitution of lactate dehydrogenase is enzymatically active. FEBS Lett. 163:132–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodsell, D. S., and A. J. Olson. 2000. Structural symmetry and protein function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29:105–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, R., R. Jaenicke, and G. Kretsch. 1983a. Kinetic analysis of the reconstitution pathway of lactate dehydrogenase using cross-linking with glutaraldehyde. Naturwissenschaften. 70:517–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, R., R. Jaenicke, and N. C. Price. 1985. Evidence for active intermediates during the reconstitution of yeast phosphoglycerate mutase. Biochemistry. 24:1817–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, R., R. Jaenicke, and R. Rudolph. 1981. Analysis of the reconstitution of oligomeric enzymes by cross-linking with glutaraldehyde: kinetics of reassociation of lactic dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 20:5195–5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, R., R. Rudolph, and R. Jaenicke. 1982. The use of subunit hybridization to monitor the reassociation of porcine lactate dehydrogenase after acid dissociation. Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 363:1259–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, R., R. Rudolph, R. Jaenicke, N. C. Price, and A. Scobbie. 1983b. The reconstitution of denatured phosphoglycerate mutase. J. Biol. Chem. 258:11014–11019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, N. M., A. J. Trew, E. T. Parkin, and A. J. Turner. 2000. The role of proteolysis in Alzheimer's disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 477:379–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenicke, R. 1974. Reassociation and reactivation of lactic dehydrogenase from the unfolded subunits. Eur. J. Biochem. 46:149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenicke, R. 1987. Folding and association of proteins. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 49:117–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenicke, R., and H. Lilie. 2000. Folding and association of oligomeric and multimeric proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 53:329–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janin, J. 1997. The kinetics of protein-protein recognition. Proteins. 28:153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. J., M. Wang, and R. Paschke. 1993. Crystal structures of medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase from pig liver mitochondria with and without substrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90:7523–7527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel, A., and J. R. Garel. 1984. Renaturation of the allosteric phosphofructokinase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 259:4917–4921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateu, M. G., M. M. Sanchez Del Pino, and A. R. Fersht. 1999. Mechanism of folding and assembly of a small tetrameric protein domain from tumor suppressor p53. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maury, C. P. 1991. Gelsolin-related amyloidosis. Identification of the amyloid protein in Finnish hereditary amyloidosis as a fragment of variant gelsolin. J. Clin. Invest. 87:1195–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C. 2000. An overview of the potassium channel family. Genome Biol. 1:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modler, A. J., K. Gast, G. Lutsch, and G. Damaschun. 2003. Assembly of amyloid protofibrils via critical oligomers—a novel pathway of amyloid formation. J. Mol. Biol. 325:135–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichtl, A., J. Buchner, R. Jaenicke, R. Rudolph, and T. Scheibel. 1998. Folding and association of β-galactosidase. J. Mol. Biol. 282:1083–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosawa, F., and S. Asakura. 1975. Thermodynamics of the Polymerization of Protein. Academic Press, London.

- Ramaswamy, S., D. A. Kratzer, A. D. Hershey, P. H. Rogers, A. Arnone, H. Eklund, and B. V. Plapp. 1994. Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic studies of Saccharomyces cerevisiae alcohol dehydrogenase I. J. Mol. Biol. 235:777–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehaber, V., and R. Jaenicke. 1992. Stability and reconstitution of d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic eubacterium Thermotoga maritima. J. Biol. Chem. 267:10999–11006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risse, B., G. Stempfer, R. Rudolph, H. Mollering, and R. Jaenicke. 1992. Stability and reconstitution of pyruvate oxidase from Lactobacillus plantarum: dissection of the stabilizing effects of coenzyme binding and subunit interaction. Protein Sci. 1:1699–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, R., I. Heider, E. Westhof, and R. Jaenicke. 1977. Mechanism of refolding and reactivation of lactic dehydrogenase from pig heart after dissociation in various solvent media. Biochemistry. 16:3384–3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, R., and R. Jaenicke. 1976. Kinetics of reassociation and reactivation of pig-muscle lactic dehydrogenase after acid dissociation. Eur. J. Biochem. 63:409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, R., G. Zettlmeissl, and R. Jaenicke. 1979. Reconstitution of lactic dehydrogenase. Noncovalent aggregation vs. reactivation. 2. Reactivation of irreversibly denatured aggregates. Biochemistry. 18:5572–5575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rypniewski, W. R., and P. R. Evans. 1989. Crystal structure of unliganded phosphofructokinase from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 207:805–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saville, B. 1971. On the use of “concentration-time” integrals in the solution of complex kinetic equations. J. Phys. Chem. 75:2215–2217. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, G. 2002. Kinetic studies of protein-protein interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, G., and T. Selzer. 1999. Predicting the rate enhancement of protein complex formation from the electrostatic energy of interaction. J. Mol. Biol. 287:409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe, D. J. 1998. The cell biology of β-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin in Alzheimer's disease. Trends Cell Biol. 8:447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheinerman, F. B., R. Norel, and B. Honig. 2000. Electrostatic aspects of protein-protein interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10:153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum-Bayer, H., and A. Levitzki. 1976. The refolding of lactate dehydrogenase subunits and their assembly to the functional tetramer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 445:261–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teschner, W., and J. R. Garel. 1989. Intermediates on the reassociation pathway of phosphofructokinase I from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 28:1912–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu, L., and C. Deutsch. 1999. Evidence for dimerization of dimers in K+ channel assembly. Biophys. J. 76:2004–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamocky, M., and F. Koller. 1999. Understanding the structure and function of catalases: clues from molecular evolution and in vitro mutagenesis. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 72:19–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zettlmeissl, G., R. Rudolph, and R. Jaenicke. 1979. Reconstitution of lactic dehydrogenase. Noncovalent aggregation vs. reactivation. 1. Physical properties and kinetics of aggregation. Biochemistry. 18:5567–5571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]