Abstract

Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) contributes to Ca2+ transients in frog sympathetic ganglion neurons. Here we use video-rate confocal fluo-4 fluorescence imaging to show that single action potentials reproducibly trigger rapidly rising Ca2+ transients at 1–3 local hot spots within the peripheral ER-rich layer in intact neurons in fresh ganglia and in the majority (74%) of cultured neurons. Hot spots were located near the nucleus or the axon hillock region. Other regions exhibited either slower and smaller signals or no response. Ca2+ signals spread into the cell at constant velocity across the ER in nonnuclear regions, indicating active propagation, but spread with a (time)1/2 dependence within the nucleus, consistent with diffusion. 26% of cultured cells exhibited uniform Ca2+ signals around the periphery, but hot spots were produced by loading the cytosol with EGTA or by bathing such cells in low-Ca2+ Ringer's solution. Peripheral hot spots for Ca2+ release within the perinuclear and axon hillock regions provide a mechanism for preferential initiation of nuclear and axonal Ca2+ signals by single action potentials in sympathetic ganglion neurons.

INTRODUCTION

Cytosolic Ca2+ regulates a wide range of functions within an individual cell. In neurons, Ca2+ levels govern many processes, including neurotransmitter secretion, regulation of membrane excitability, and induction of gene expression (Ghosh and Greenberg, 1995; Clapham, 1995; Hardingham et al., 1997). Spatiotemporal differences in [Ca2+] within a given cell, as well as spatial organization of the Ca2+-receptive proteins that bind and respond to Ca2+, may provide a partial explanation for how the single messenger Ca2+ is able to selectively modulate multiple cellular functions (Linden, 1999; Akita and Kuba, 2000; Marchant and Parker, 2000; Pozzo-Miller et al., 2000; Koopman et al., 2001; Young et al., 2001). The experimental characterization of local Ca2+ signals is thus of major interest for understanding Ca2+ signaling.

In a previous study, we used video-rate laser scanning confocal microscopy to investigate local Ca2+ signals at the periphery of the cell body of cultured frog sympathetic ganglion neurons (SGNs) (McDonough et al., 2000). We found that application of caffeine, a pharmacological agent that sensitizes ryanodine receptor (RyR) Ca2+-release channels (McPherson et al., 1991) in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane (Verkhratsky and Petersen, 1998) to activation by Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR), reproducibly initiated Ca2+ release at one or more distinct localized sites around the periphery of the neuron (McDonough et al., 2000). Here we investigate elevations of Ca2+ at the cell periphery in response to a single action potential. Such action potential-induced Ca2+ signals are also initiated by CICR (Cohen et al., 1997) in frog sympathetic ganglion neurons (Akita and Kuba, 2000). Using video-rate confocal imaging, we now find that the Ca2+ transient in response to a single action potential differs appreciably in different subareas of the same neuron. In neurons in freshly dissected ganglia, as well as in a large majority of cultured neurons, [Ca2+] rises rapidly at a few local hot spots around the periphery of the cell, and rises more slowly and much less or not at all in other peripheral regions and in deeper areas of the cell. Our previous (McDonough et al., 2000) and present Ca2+ imaging results thus indicate local functional differences in CICR activation around the cell periphery.

We now find that the peripheral perinuclear region, located between the plasma membrane and the peripherally positioned nucleus, almost always exhibits a hot spot for Ca2+ release in response to a single action potential, indicating a functional specialization of the perinuclear periphery to reliably respond to AP stimuli. A second, independent hot spot is frequently located across the cell body from the peripheral perinuclear site, near the actual or previous axon hillock region, in either intact or cultured, axotomized neurons, respectively. Even in those cultured neurons that exhibited a uniform peripheral Ca2+ transient in response to a single action potential under control conditions, addition of intracellular EGTA or lowering extracellular [Ca2+] reveals latent peripheral hot spots for initiation of Ca2+ release in the perinuclear and axon hillock regions. Frog sympathetic ganglion neurons thus appear to be functionally specialized to preferentially generate local Ca2+ signals at the peripheral perinuclear and axon hillock regions in response to single neuronal action potentials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ganglion dissection and cell culture

Frogs (Rana pipiens) were chilled in ice for 30 min and then sacrificed by decapitation and pithing, according to guidelines issued by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Maryland Baltimore (Baltimore, MD). The two chains of sympathetic ganglia were isolated, desheathed, and placed into a Ca2+-free Ringer's solution containing 3.3 mg/mL collagenase (Sigma Type IA, C-9891, for 30–35 min at 35°C; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO). For studying cells within freshly isolated ganglia (Smith, 1994), the chains of ganglia were then washed gently in 2 mM Ca2+ Ringer's solution 3× to remove collagenase completely. For Ca2+ indicator dye loading, ganglia were placed in 2 mM Ca2+ Ringer's solution containing 200 μM neostigmine (a cholinesterase inhibitor) and 20 μM fluo-4 acetoxymethylesther, AM for 1 h at room temperature, after which the ganglia were washed with dye- and neostigmine-free Ringer's solution and placed in a cover glass-bottom chamber for confocal experiments.

To isolate neurons for culture, the two chains of sympathetic ganglia were prepared and collagenase-digested as described above. The enzymatic dissociation was completed in a trypsin solution (2 mg/mL, Sigma Type I, T-8003, for 10 min at 35°C), after which individual cells were isolated from the digested tissue by trituration. The cells were then plated in cover glass-bottom petri dishes coated with poly-L-lysine, and cultured for 2–7 days at 22–24°C in a 1:1 mixture of Leibovitz's L-15 solution and our neuron culture medium containing 2 mM Ca2+. Before experiments, cultured cells were washed 3× in 2 mM Ca2+ Ringer's solution. For calcium experiments, cultured cells were loaded with 2 μM fluo-4 AM in 2 mM Ca2+ Ringer's at room temperature for 20 min and then washed with dye-free Ringer's solution (for composition of all solutions, see Cseresnyés et al., 1997; McDonough et al., 2000). A few cultured cells were loaded with fluo-4 and then imaged during plasma membrane permeabilization by 0.1% saponin in internal solution (in mM: 80 Cs glutamate, 2 trizma maleate, 20 Na creatine phosphate, 7 ATP, 6 MgCl2, 1 DTT, 0.1 EGTA; pH = 7.0). After fluo-4 calcium measurements, some cultured neurons were loaded with TMRE for monitoring the spatial distribution of mitochondria within the cell. In such cases, cells were exposed to 1–2 μM TMRE for 1–5 min, and then to 100 nM TMRE for the rest of the experiment. Some cells (not fluo-4 loaded) were stained with 100 mM BODIPY-FL ryanodine for 10–15 min, and then subsequently loaded with TMRE as above.

Confocal imaging

Confocal imaging experiments were carried out on a Nikon RCM-8000 video-rate system, based on a Nikon Diaphot 300 inverted microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY). Cells were imaged with a Nikon 60× NA 1.2 water-immersion objective lens (for further details about the confocal system, see McDonough et al., 2000). The larger cells (B cells) were selected for all experiments. In many cases cells were also selected to exhibit a noticeable change of fluorescence (ΔF) in response to a test field stimulus. Sequences of successive images of fluo-4 loaded cells were acquired at video rate without online averaging. To improve the signal/noise ratio of the images in these sequences of high time-resolution images, offline signal averaging was generally applied. In such cases, a given neuron was repeatedly activated (3–6× in most experiments), with the same field stimulus and stimulus timing and synchronization with the imaging system. The images corresponding to a given elapsed time in each series were averaged offline using custom-written image analysis software in the IDL programming language (see also Results of Fig. 2). This signal averaging resulted in a sequence of averaged video-rate confocal images that were much smoother, with a theoretical improvement of signal/noise proportional to √n, where n is the number of repeats. Keeping the number of repeats in the 3–6 range in most experiments allowed us to perform multistep experiments without significant photobleaching. We will refer to the sequence of signal-averaged video-rate images as an averaged sequence. Thus, members of an averaged sequence will be improved signal/noise images, which still correspond to video-rate acquisition. Cells respond very reproducibly to single APs, justifying the signal-averaging procedure (see Figs. 2 and 3).

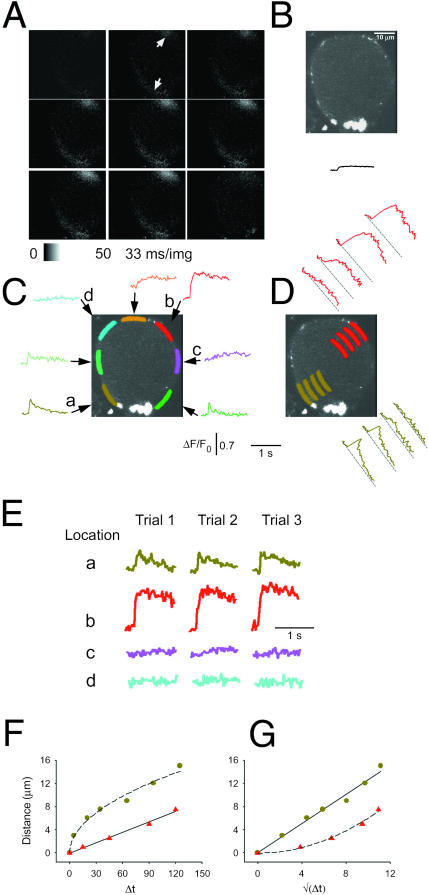

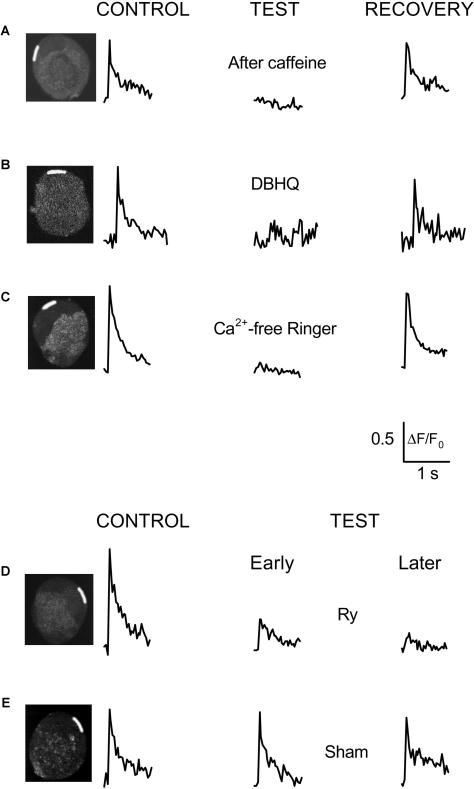

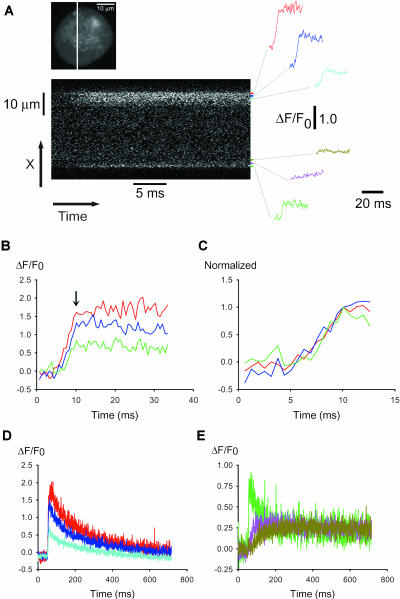

FIGURE 2.

Nonuniform calcium responses of a frog neuron in intact sympathetic ganglion during individual action potentials. Confocal images were collected at video rate (33 ms/image) from a fluo-4 AM loaded frog neuron, located inside of a partially digested sympathetic ganglion, during APs induced by field stimulation (see Methods). The APs were repeated 3×, with a 2-min break between each stimulus, and the corresponding images in each of the three series of images (53 images per series) were signal-averaged offline to create an averaged sequence. (A) The first eight images are sequential elements of the averaged sequence, whereas the last panel corresponds to the 53rd image recorded after the 2-min break between AP applications. The field stimulus was applied 1 ms into the second image of Fig. 2 A, corresponding to 1/30th of the vertical dimension of this image (see Methods). The fluorescence signal corresponds to ΔF (= F–F0; see Methods) and is presented on a stretched lookup table (see panel below). The two white arrows indicate the two hot spots for Ca2+ release. The arrow at the direction of 7 o'clock points at the hot spot in the peripheral perinuclear area, whereas the arrow at 1 o'clock shows the nonnuclear hot spot, which is located near the axon hillock. (B) A confocal image of fluo-4 fluorescence of the same neuron, collected at the same focal plane as in A using online frame averaging of 16 frames of raw images, collected at video rate without stimulation, to improve image quality. The nucleus was always located at the periphery, a few microns inside the PM, both in neurons in intact ganglia and in cultured cells. The bright area near 6 o'clock in B may be a presynaptic bouton of an axosomatic synapse. Similar bright fluorescent structures were found on the majority of intact ganglion neurons of this study. The solid line under the cell's image shows the ΔF/F0 response averaged over the entire cell, using the same time- and fluorescence scales as in C and D. (C) Spatially averaged values of fluorescence were calculated from the indicated color-highlighted areas of interest (AOIs) around the perimeter of the cell, using successive frames of the averaged sequences of images. The corresponding color-coded records give ΔF/F0 values, where F0 was calculated as the mean of the fluorescence value in the AOI in the first five images in the average sequence, all recorded before the field stimulus. The AOIs that were plotted in shades of green (light, dark, and olive) are at or near the peripheral perinuclear zone, whereas the red AOI is at the axon hillock. The location of the axon was observed directly by using transmitted light microscopy before the AP experiments, but the axon was outside the confocal plane of focus after switching to fluorescence imaging. The orange and pink AOIs were close to the axon hillock. All of the colored AOIs were drawn inside the cell at a constant distance from the PM, and all were of the same width and length (33 μm2). The nonuniform distribution of calcium signals around the periphery of the cell was detected in seven out of seven intact ganglion cells. Special care was taken when positioning the perinuclear AOI (olive-green), while analyzing this and all other experiments, to avoid any overlap between this AOI and the intranuclear space. (D) Radial spread of the fluo-4 signal from two hot spots in the same neuron. The olive-green (perinuclear) and red (axonal) AOIs were shifted to increasing radial distances from the periphery of the cell, to calculate the time course of ΔF/F0 at deeper zones of the cytosol (red) or nucleus (olive-green). The position of each record within the two stacks of AOIs (red curves above the cell's image, olive-green curves below and to the right of the image) corresponds to the position of the respective AOI inside the cell relative to the PM. (E) Time course of unaveraged fluorescence during each of the individual three APs on a compressed timescale. The areas selected for presentation were from the peripheral perinuclear zone (a, olive-green), the axon hillock area (b, red), and two of the quiescent peripheral nonnuclear regions (c, pink, and d, cyan). The field stimuli were 2-ms long in all cases. (F) Radial distance of the AOI from the PM as a function of the time to half-maximum rise of ΔF/F0 at that AOI. To calculate these data, seven or five AOIs were selected in the nuclear and nonnuclear areas, respectively, arranged radially at gradually larger distances from the PM (similarly to the arrangement of AOIs in D). The distance between the AOIs and the PM was measured in μm using our custom-made IDL program, whereas the time to half-peak at each AOI was calculated in milliseconds as the time interval between the arrival of the electric field stimulus and the half-maximum time of the resulting Ca2+ transient at that AOI. (G) Same data as F but plotted as a function of the square root of the time to half-peak. In both F and G, the rise-time values were corrected for the time to half-peak at the most peripherally located AOI, which was estimated for each data set by the x-intercepts of the straight lines fit to the data for spread from nonnuclear (F, red triangle) or nuclear (G, olive circles) hot spots.

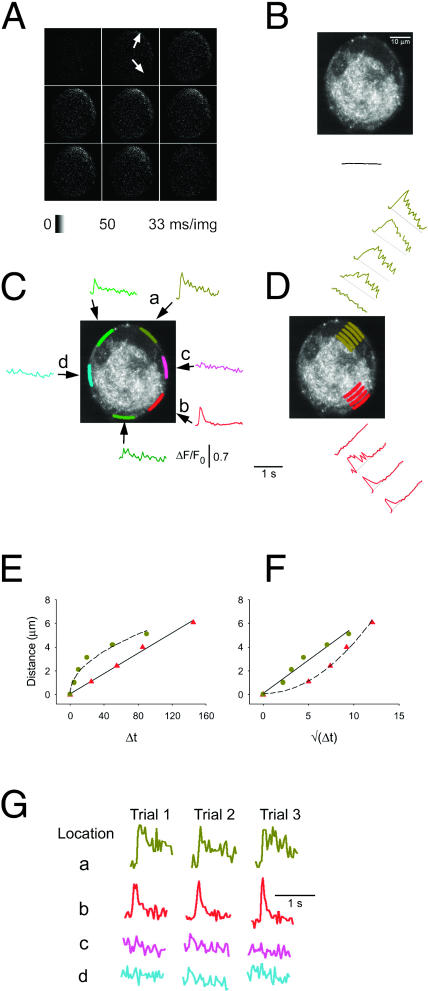

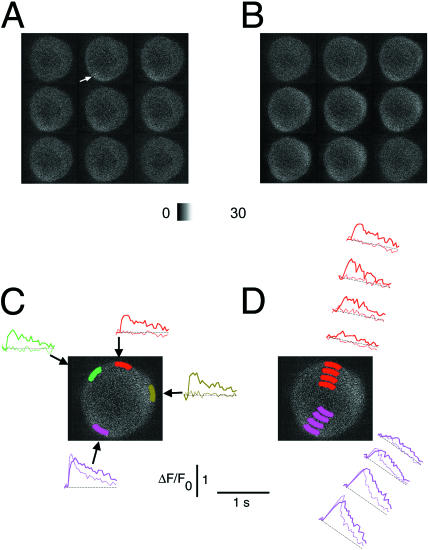

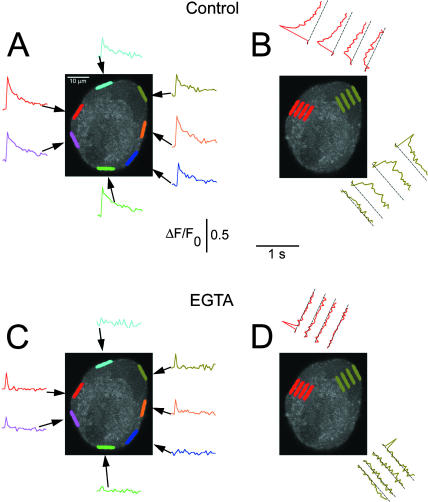

FIGURE 3.

Nonuniform calcium responses of a cultured frog sympathetic ganglion neuron during individual action potentials. AP-induced Ca2+ transients were recorded in a cultured frog sympathetic ganglion neuron. The dye loading, fluorescence recording, and offline analysis methods were largely similar to those applied in Fig. 2. (A) The arrow at 1 o'clock points at the hot spot in the peripheral perinuclear area (compare with B), whereas the other arrow, at 5 o'clock, shows the nonnuclear hot spot. These images show no small regions of constant high fluorescence, in accordance with the absence of synapses in cultured neurons (see Fig. 1 B). (B) The fluo-4 fluorescence of the same neuron was imaged at the same focal plane, using online image averaging at 16 frames/image. The higher spatial resolution of the averaged image provides a better view of the cell's structure. The solid curve under the image indicates the whole-cell average of the ΔF/F0 signal, generated by a single AP. Same scales as in Fig. 3, C and D. C–G were generated similarly to the corresponding panels of Fig. 2.

To characterize local calcium signaling in our cells, we calculated the time course of spatially averaged fluorescence within multiple user-specified areas of interest (AOIs) within each neuron using our custom-written software. First, the AOIs were specified. Then the pixel values within each AOI were corrected for background fluorescence, recorded from a cell-free area of each image, and the corrected values within the AOI were arithmetically averaged. The spatially averaged fluorescence values were calculated either from the original images or from the averaged sequence, providing video-rate time resolution in either case. The AOIs selected around the cell periphery were of identical size and shape in a given neuron, and at equal distances from the plasma membrane, to avoid artificial differences of the local Ca2+ signals due to varied sizes or to radial locations of the AOIs. The AOI areas ranged from 14 to 33 μm2 in different cells.

Field stimulation and stimulus synchronization with confocal imaging

Brief (0.5, 1, or 2 ms) field stimuli were used to generate single action potentials (APs) in isolated frog neurons or within neurons in freshly dissected ganglia. The field electrodes were custom-made, using high purity platinum wires. One electrode was shaped into a loop, with a diameter of ∼3 mm. The cell to be tested was positioned approximately in the center of the loop electrode. The other electrode was a straight wire that was placed directly above the center of the loop electrode. The field stimulus was initiated by the image acquisition system that provided a TTL pulse to the signal generator at the instant of the start of the image sequence. The timing and the duration of the field stimulus were set by a custom-made system, which consisted of a digital signal generator and an amplifier. The field stimulus was applied either 100 or 200 ms after the start of the image sequence, thus providing either three or six control images before stimulation at the start of each sequence. These control images were used to determine the steady-state fluorescence level (F0) within each specified AOI, which was then applied to calculate the relative fluorescence values (ΔF/F0, where ΔF = F–F0).

At video rate, one line of pixels is scanned in 63 μs, resulting in acquisition of a full-frame image in 30 ms (480 horizontal lines per image; scanning from bottom to top of image as shown here). Return of the laser beam to its starting position and start of the next image required an additional 3 ms, thus providing us with a 33-ms/image acquisition rate when obtaining image sequences. In all but one figure, the end of the stimulation pulse was below the position of the lower edge of the cell at the bottom of the image. Thus, the fluorescent pattern inside the cell in the image in which the stimulus was applied represents the cell at a time after stimulus application. It should be noted, however, that the bottom of each acquired image (either original or of the averaged sequence) corresponds to a moment of time 30 ms earlier than the top of that same image due to the 30-ms acquisition time for each image, with successive lines being acquired from bottom to top of the image.

RESULTS

Local peripheral Ca2+ hot spots in neurons in intact sympathetic ganglia

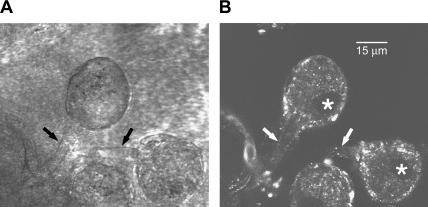

Neurons in partially digested ganglia (see Methods) exhibited intact axons (Fig. 1, arrows) and were successfully loaded with fluo-4 (Fig. 1 B) using 60-min exposure to fluo-4 AM (20 μM) in the presence of 200 μM neostigmine. After such loading treatments, relatively small bright round or oval structures were usually visualized on the surface of many sympathetic ganglia neurons (SGNs) within the ganglia (Fig. 1 B). In other images (not shown) these structures appeared connected by thinner fluorescent lines, indicating that they may be presynaptic varicosities located at synapses on the sympathetic ganglion neurons. Neuronal nuclei were visualized as darker oval or bean-shaped areas (Fig. 1 B, stars) near the cell periphery.

FIGURE 1.

General structure of intact ganglion neurons. Sympathetic ganglia were freshly isolated, enzymatically digested, and loaded with fluo-4 AM in the presence of neostigmine, as described in Methods. The ganglia were imaged in the Biorad MRC 600 confocal system (Biorad, Hercules, CA). A and B show the scattered and fluo-4 fluorescence light images, respectively, of a selected area of a ganglion with three identifiable sympathetic ganglion neurons (SGNs) (one shown only in part, at the bottom of the image). The axons of the cells at the top and on the right are labeled with arrows (black arrows in A, white in B). The nuclei of these cells appear as dark, oval-shaped areas at the periphery of the cells (B, white stars). The bright areas of fluo-4 fluorescence (B) may correspond to presynaptic varicosities. The scale bar in B corresponds to 15 μm.

We applied video-rate confocal microscopy to study local calcium signaling during APs in fluo-4 loaded SGNs. Fig. 2 presents video-rate confocal imaging data from a neuron in a partially digested sympathetic ganglion. Three sequences of video-rate images were acquired in precise synchrony with the electric field stimulus, and the corresponding images in each sequence were digitally averaged after the experiments to give the averaged sequence in Fig. 2 A. The first video frame image in Fig. 2 A was recorded 33 ms before the field stimulus, the second image overlapped the time of stimulation, and the next six images were recorded sequentially after stimulation. These first eight images correspond to sequential frames recorded at video rate (33 ms per image). The ninth image was recorded after a 2-min recovery, during which no stimuli were applied and no images were collected. The images in Fig. 2 A demonstrate that the Ca2+-dependent fluo-4 fluorescence change, the Ca2+ signal or Ca2+ transient, first raises within two small areas, or hot spots, at the periphery of this cell (arrows). The spread of increased fluorescence away from the hot spots was rather restricted around the cell periphery, whereas the radial spread of the Ca2+ signal into the cell was somewhat less limited. Due to the small number, localized origin, and limited spread of increased fluorescence at the hot spots, the fluorescence signal averaged over the whole cell image showed negligible fluorescence change as a result of the electrical stimulation (Fig. 2 B, record below image).

To characterize the spatiotemporal distribution of Ca2+ in the cell, small AOIs were selected within the cell, as shown by the colored areas in the fluorescence images in Fig. 2, C and D. The fluorescence values within each of these colored areas were spatially averaged and used to calculate a ΔF/F0 time course in each AOI (Fig. 2, C and D).

All AOIs used in a given cell were of the same size and shape, and the AOIs around the periphery of a cell were all positioned to be at equal distances from the plasma membrane to avoid artificial differences in Ca2+ responses due simply to different sizes or different radial locations of the AOIs.

The time course of fluorescence in each of the AOIs positioned around the cell periphery in Fig. 2 C clearly demonstrates that this neuron exhibited two local peripheral hot spots for initiation of Ca2+ release. One hot spot was located in the peripheral perinuclear area (a, olive-green). This location exhibited a very rapidly rising local Ca2+ transient, going from rest to peak signal within the 33-ms time interval from acquisition of data at a given location in one image and the next image, and a relatively rapid decay phase (t1/2 = 240 ms). The other hot spot, at the cell periphery roughly opposite the nucleus (b, red), had a calcium transient with a similarly rapid onset but a slower decay (t1/2 > 1 s) that was too long to be determined with the sampling interval used here. Other peripheral areas that were about midway between these two sites remained quiescent (c, violet and d, blue).

Local peripheral hot spots for initiation of Ca2+ release were observed in every neuron examined in this study in a partially dissociated ganglion (seven out of seven cells). All neurons exhibited a hot spot in the peripheral perinuclear region and five out of seven had one or more hot spots roughly opposite the nucleus in the axon hillock region. Thus, local peripheral hot spots for Ca2+ release in the perinuclear and axon hillock region are a consistent feature of neurons in freshly isolated ganglia.

All hot spots in both the perinuclear and the nonnuclear regions exhibited a very rapid rising phase, which was generally completed from one 33-ms image to the next. The half-time of decay of the local peripheral Ca2+ signals at the perinuclear hot spots was always relatively fast (180–300 ms; 260 ± 20 ms, N = 7). In contrast, at some nonnuclear hot spots the half-time of decay (240 ± 26 ms, N = 3) was similar to that at the perinuclear hot spots, whereas other nonnuclear hot spots (N = 4) exhibited decay half-times >1 s. In principle, the time course of rise and fall of Ca2+ at the release site will be determined by the balance between the rate of Ca2+ release and the rates of Ca2+ removal by Ca2+ binding and transport or by Ca2+ diffusion out of the release region. The more rapid decline of the Ca2+ signal observed in the peripheral perinuclear region compared to some of the nonnuclear peripheral release sites might thus indicate either more effective removal of Ca2+ in the perinuclear periphery or prolonged release in the nonnuclear release site.

The hot spots for Ca2+ release were temporally and spatially stable throughout an experiment. Fig. 2 E presents fluorescence records for individual (i.e., unaveraged) responses to single APs from both of the two hot spots (a, olive-green peripheral perinuclear location; b, red peripheral nonnuclear location) and from two quiescent peripheral areas (Fig. 2 C, c, violet and d, blue). These records demonstrate that the active areas gave reproducible Ca2+ transients in response to each electrical stimulus, and thus reliably and repeatedly functioned as hot spots for Ca2+ release. Similarly, the quiescent zones were reproducibly nonresponsive throughout the experiment. These findings indicate that the hot spots are structurally determined, not random. Moreover, activation at the hot spots was always temporally synchronized to the time of the AP, thus excluding the possibility that these sites were stochastic or appeared spontaneously. Finally, the hot spots cannot be attributed to localized depolarization, since the plasma membrane should form an isopotential surface over the entire cell body of these neurons.

In the cell in Fig. 2 the intact axon was observed in lower power views (not shown) to be located at the top of the fluorescence images in Fig. 2. The nonnuclear hot spot was thus in close proximity to the axon hillock, which may indicate a functional relationship between this site and the origination site of the axonal Ca2+ transients. However, the occurrence of nonnuclear peripheral hot spots in individual cultured axotomized frog SGNs (below) indicates that the continued presence of the axon is not required for maintenance or function of this nonnuclear Ca2+ release site.

Video-rate confocal imaging not only allowed us to identify the peripheral hot spots for Ca2+ release, but also provided the means to characterize the spread of the Ca2+ signal away from the hot spots. The radial spread of the Ca2+ signal from the two hot spots in the neuron in Fig. 2 is illustrated in Fig. 2 D. The ΔF/F0 signals calculated for each of the indicated sets of four AOIs positioned at increasing radial distance from the cell periphery (Fig. 2 D) indicate that the Ca2+ signal spreads with decrement and slowed time course both within the nucleus (a, olive, bottom) and in the nonnuclear (b, red, top) regions. Note that the records in Fig. 2 D are rotated so the baselines (dashed lines) are not horizontal but are roughly parallel to the central tangent to the corresponding circumferential AOIs.

Spread of the Ca2+ signal away from peripheral hot spots

The spread of Ca2+ away from the hot spots may be expected to occur via passive diffusion, with the spread retarded by Ca2+ binding and Ca2+ transport but possibly augmented by the active process of Ca2+ release from Ca2+ stores by CICR. However, since releasable Ca2+ stores are not present within the nucleus, radial spread of Ca2+ across the nucleus is expected to occur purely by Ca2+ diffusion and binding. The distance covered by passively diffusing Ca2+ is directly proportional to the square root of time (Crank, 1975), whereas release-assisted diffusion will exhibit a more constant velocity of spread. Ca2+-binding would slow the diffusion. In Fig. 2 F we plot the distance (in μm, measured from the plasma membrane, PM) as a function of the time to half-maximum rise of the ΔF/F0 signal recorded at that distance for the signals originating from the nuclear (olive-green symbols) and nonnuclear (red symbols) hot spots. The difference between the mechanisms of spread in the nuclear and nonnuclear cytosolic areas is clearly shown by the different shapes of these two curves. The nonnuclear data (red triangles in Fig. 2 F) are closely approximated by a linear function (solid straight line) indicating a constant velocity of spread. In contrast, the nuclear signal (olive-green) follows a nonlinear time course. To determine whether the nuclear data followed a passive diffusion time course, the data from Fig. 2 F were replotted as a function of (time)1/2, i.e., on a square-root timescale in Fig. 2 G. The nuclear data were now well fit by a straight line in Fig. 2 G. The fitted data values of the straight line in Fig. 2 G were also transformed onto the linear timescale and replotted in Fig. 2 F (dashed curve), showing that the original nuclear data were well described by a square-root time function. The straight line fit to the nonnuclear data from Fig. 2 F was also replotted on a square-root timescale in Fig. 2 G (dashed line). These data suggest that Ca2+ spreads mainly via passive diffusion in the nuclear area (Lipp et al., 1997), whereas the Ca2+ spread in the nonnuclear cytosolic areas is probably assisted by an active process such as Ca2+ release from the ER.

It is difficult to quantify the amplitude of the change in [Ca2+] from the fluorescence signals recorded with fluo-4, which is not a ratiometric indicator. Differences in fluorescence signals due to differences in local effective concentration of fluo-4 because of possible dye binding and/or dye exclusion from intracellular organelles can be partially compensated for by normalizing the fluorescence change observed in any AOI to the resting fluorescence in the same AOI (as done here), assuming that all dye is cytosolic and that resting cytosolic [Ca2+] is the same in all AOIs. This approach is not perfect since it is possible that some dye may be sequestered within organelles at relatively high [Ca2+], and thus contribute to the resting fluorescence but not to the cytosolic Ca2+ signal. However, our results (Fig. 5, below) indicate that fluorescence due to sequestered dye may be minimal in these cells. Finally, it has also been shown that fluorescent Ca2+-sensitive dyes behave differently in the nucleus than in the cytosol (Thomas et al., 2000 and Fig. 5, below). Nonetheless, despite these uncertainties in absolute calibration, the very small or undetectable changes in fluorescence observed in the selected AOIs circumferentially or radially displaced from the hot spots (Fig. 2) would seem to correspond to very small or negligible rises in Ca2+ in response to a single action potential in these regions unless all dye contributing to resting fluorescence in these areas is totally unresponsive to elevated Ca2+.

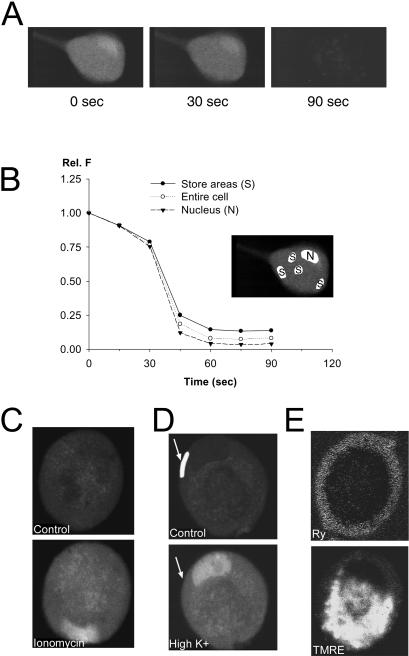

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of Ca2+-sensitive dye, and of intracellular Ca2+ compartments in cultured frog SGNs. (A) To investigate if the local hot spots might be the result of noncytosolic, store-accumulated dye, we measured the changes of fluo-4 fluorescence in a cell that was exposed to the membrane lipid detergent saponin, applied at 0.1% concentration in frog intracellular solution (see Methods). The three images show the fluo-4 fluorescence of an unstimulated cell at 0 s, 30 s, and 90 s after adding saponin to the recording chamber. The images are the result of 16-frame online averaging, to improve the signal/noise ratio. (B) The average fluorescence was calculated over selected areas of the same cell (white-highlighted areas in insert), to quantify the saponin effect. The areas covered the nucleus (N in insert; triangles in graph), the entire cell (unfilled circles), and a few selected bright areas within the cell, probably corresponding to dye accumulation within Ca2+-rich stores (S; solid circles). At the end of the experiment, only 5–10% of the original fluorescence was detectable, indicating that fluorescence signals originating from store-accumulated dye do not significantly affect our results. (C, D) Other neurons, loaded with fluo-4 AM, were exposed to very large Ca2+ influx, thus providing data about the uniformity of the distribution of Ca2+ sensitive dye in these cells. In C, the neuron was exposed to the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (2 μM) in 2 mM Ca2+ Ringer's solution for 5 min. Ca2+ influx resulted in a uniform increase of fluo-4 fluorescence in the cytoplasm and the nucleus (bean-shaped bright area near the bottom). In D, a cell was depolarized by 50 mM K+ Ringer's solution, which resulted in a large and uniform increase of fluo-4 fluorescence in the cytosol, and a larger increase in nucleus. The cell in D is the same that was used in Fig. 4 A, and exhibited a local hot spot in response to a single action potential at the peripheral perinuclear AOI (white-highlighted area in the top image, pointed out by a white arrow in both the top and bottom images of D). (E) Another cell was stained with 100 nM BODIPY Ry for 10 min, and 1 μM TMRE for 1 min, both in Ringer's solution. The cell was then kept in 100 nM TMRE Ringer's for the duration of the experiment, to avoid the leakage of the voltage-sensitive dye from the mitochondria. The cell was then imaged at 488 nm (BODIPY Ry, top) and at 550 nm (TMRE, bottom), averaging 16 frames online. The RyR Ca2+ release channels appear to be concentrated in a narrow shell at the periphery of the cell, and the mitochondria seem to occupy an interior zone.

Peripheral Ca2+ hot spots in cultured SGNs

Neurons in freshly isolated intact ganglia have the advantage of maintained axons and synapses. However, the technical difficulties of manipulating and recording from neurons in intact ganglia make the use of this preparation rather time-inefficient and relatively impractical for routine experiments. Therefore, we also investigated AP-induced Ca2+ transients in individual cultured SGNs, which lack axons and synapses and may have undergone some possible cellular reorganization in culture. Despite these differences, the majority of cultured SGNs responded to single APs with local Ca2+ hot spots (Fig. 3) similar to those observed in neurons in intact ganglia (Fig. 2). Fig. 3 A presents video-rate confocal imaging data from such a neuron. Similar to the neurons from the intact ganglion in Fig. 2, this cultured SGN also exhibited local peripheral Ca2+ responses to a single AP. Two peripheral hot spots for Ca2+ release were identified in this neuron. As in the neurons in the intact ganglia, one of the hot spots was located in the perinuclear periphery (top), whereas the other was found at a peripheral location (bottom right) (Fig. 3 A, arrows). An average of 16 images of the resting cell (Fig. 3 B) shows the cell nucleus as a darker bean-shaped subplasma membrane region near the top of the cell. The fluorescence response averaged over the entire cell exhibited little change as a result of cell stimulation (Fig. 3 B, record below cell image).

Using the images in Fig. 3 A, we calculated the ΔF/F0 Ca2+ responses in the two peripheral hot spots, as well as in several other peripheral cytoplasmic AOIs. The selected AOIs and the corresponding ΔF/F0 records were color-coded (Fig. 3 C). Both the perinuclear and nonnuclear hot spots (a, olive-green, top; b, red, bottom right, respectively) responded to a single AP with a very rapidly rising and rapidly falling Ca2+ transient. In this cell, the t1/2 for the decay of the ΔF/F0 signal was 360 ms or 130 ms at the perinuclear or nonnuclear hot spots, respectively. In 23 cultured cells with local peripheral Ca2+ hot spots, 17 exhibited a relatively rapid decay of ΔF/F0 at both perinuclear (t1/2 = 330 ± 60 ms) and nonnuclear (t1/2 = 195 ± 15 ms) hot spots, whereas six cells exhibited rapid decay at the nuclear hot spots (t1/2 = 310 ± 120 ms) but slower decay at the nonnuclear site (t1/2 > 1 s). These 23 cells were from a nonbiased sample (see below).

The Ca2+ transients also spread from the two hot spots toward the center of the neuron (Fig. 3 D). As the Ca2+ signal spread toward more central locations, the local transients exhibited progressively smaller and slower Ca2+ responses. As in the intact neurons (Fig. 2, F and G), the radial spread of Ca2+ across the nucleus from the perinuclear hot spot was mainly via passive diffusion, whereas Ca2+ release significantly contributed to the radial spread of Ca2+ from the nonnuclear hot spot, as shown by the distance-time and distance-square-root-time graphs in Fig. 2, E and F, respectively. The two hot spots were also spatially and temporally stable (Fig. 3 G). Based on these results, the initiation sites in this cultured SGN and the spread of Ca2+ from these sites behaved similarly to those observed in intact ganglion neurons.

To estimate the fraction of all cultured neurons that exhibited local peripheral hot spots for Ca2+ release, we sampled a group of cells (n = 31) that were selected solely by their shape and size before observing their fluorescence signals. Of the cells in this unbiased sample, 23 cells (74%) exhibited responses at a few local hot spots around the cell periphery. Thus a large majority of the B neurons in both intact ganglia and cell cultures exhibit localized peripheral Ca2+ hot spots in response to single action potentials. The other eight (26%) cultured cells exhibited uniform Ca2+ signals around the cell periphery in response to a single AP (see below).

Nonnuclear hot spots in cultured neurons were usually located approximately across the cell from the nucleus, which also corresponds to the most common location of the axon in an intact neuron. It thus appears likely that cultured cells with nonuniform peripheral Ca2+ signals preserved the structural elements in the axonal hillock region that give rise to preferential Ca2+ release, and thus still possess a hot spot for Ca2+ release in that area, even after several days in cell culture without the presence of the axon.

To show that the field stimuli used here elicited APs, three cultured SGNs were exposed to 2 μM TTX, which completely eliminated the field stimulus-induced Ca2+ transient (data not shown). The size and shape of the Ca2+ signal remained constant using electrical stimulus intensities above a threshold level, but were zero when stimulated below that threshold (n = 7), consistent with the Ca2+ responses being triggered by all-or-none APs.

Ca2+ release from internal stores by CICR is critical for AP-induced local peripheral Ca2+ responses

Studies by Kuba and co-workers showed that Ca2+ release by CICR plays an important role in the initiation of AP-induced Ca2+ transients in bullfrog SGNs (Hua et al., 2000; Akita and Kuba, 2000), but those responses were probably not from highly localized hot spots as observed here (see Discussion below). We thus examined the importance of CICR in AP-induced local peripheral Ca2+ signals in the grass frog neurons. We first used caffeine to deplete internal Ca2+ stores. Three 1-min exposures to 10 mM caffeine in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (2 mM Mg2+ substituted for Ca2+ in Ringer's solution) completely abolished the local Ca2+ transient in response to a single AP (Fig. 4 A). Store refilling during two subsequent 30-s exposures to 50 mM K+ Ringer's solution (by equimolar substitution of K+ for Na+ in normal Ringer's, 2 mM Ca2+) largely restored the local Ca2+ signal at the original hot spot (Fig. 4 A). Interestingly, the depletion and refilling of the Ca2+ stores did not cause the appearance of local Ca2+ signals at any new peripheral locations that did not exhibit hot spots under control conditions (Fig. 4 A and three other cells in this protocol). Thus, the hot-spot locations were specifically preserved during store depletion and refilling, indicating a conserved, store content-independent structural basis for the hot spots. In five hot spots from four neurons, store depletion by two or three 1-min exposures to caffeine in Ca2+-free Ringer decreased peak ΔF/F0 to 17 ± 4% (p < 0.05) of the control peak value, and store refilling during two or three 30-s exposures to 50 mM K+ restored peak ΔF/F0 to 78 ± 18% of control.

FIGURE 4.

Calcium-induced Ca2+ release is essential for AP-induced Ca2+ transients. Spatially averaged values of relative fluorescence were calculated in several peripheral AOIs in five different neurons (A–E). Results from a single AOI in the peripheral perinuclear zone (white-highlighted areas in inset images of the neuron) are presented in each panel. The data correspond to ΔF/F0 values, calculated similarly to Figs. 2 and 3. (A) After the control measurements (left; average of three sequences), 10 mM caffeine was applied extracellularly for 1 min in Ca2+ free Ringer's solution without recording images. The caffeine application was repeated an additional 2×, 1 min each, without recording images, with 3-min washout periods between applications during which the cells were kept in caffeine- and Ca2+-free Ringer's solution to deplete the ER of Ca2+. Field stimuli were then applied 3× and the average responses were recorded in each AOI (middle). Before each stimulus, 2 mM extracellular calcium was added back for 20–30 s to allow Ca2+ influx during APs. Between recording sequences, the extracellular solution was changed back to Ca2+-free Ringer's. No increase of fluorescence was detected in any area of the cell under these experimental conditions. In an attempt to recover the cell's response to APs, the neuron was placed continuously in 2 mM Ca2+ Ringer's for 10 min and then three sequential field stimuli were applied. However, the AP-induced calcium response was still negligible (data not shown). To facilitate the recovery of calcium transients, the ER was then reloaded with Ca2+ by exposing the cell to 50 mM extracellular K+ 3×, for 30 s each (see Cseresnyés et al., 1997). The cell was placed in 2 mM K+ solution for 5 min after each high-K+ application. The high-K+ exposures elevated the fluo-4 fluorescence in the entire cell (see Fig. 5 D, which shows data from the same cell as in Fig. 4 A). The field stimuli were then repeated 3× and the average of the resulting records are shown in the right. In agreement with previous findings (Cseresnyés et al., 1997), three brief high-K+ exposures were capable of completely reloading the ER with Ca2+, as indicated by the full restoration of the Ca2+ responses (Fig. 4 A, right). (B) Another neuron was stimulated by 0.5-ms duration electric field pulses under control conditions (left), in the presence of 30 μM DBHQ (middle), and after a 20-min washout of DBHQ (right). DBHQ was applied for 10 min before recording the first AP-induced transient in the presence of the drug. Before the washout experiments, the cells were rinsed 3× with DBHQ-free Ringer's, and then incubated in drug-free Ringer's for 20 min before recording. Averaged sequences for each experimental condition were calculated from four sequences of video-rate confocal images, with 2-min breaks between pulses (see Methods). Values of relative fluorescence from the averaged sequence were calculated within a peripheral perinuclear AOI in each panel (white-highlighted zone in the inset). (C) To investigate the role of Ca2+ influx via PM Ca2+ channels during AP-induced calcium signaling, the response of another neuron was first recorded under control conditions (left). The cell was then incubated in Ca2+-free Ringer's solution for 3 min and excited by 2-ms field stimuli in the continued absence of extracellular calcium. No response was recorded in the hot spot (middle), or any part of the neuron (not shown). The cell was then washed 3× with 2 mM Ca2+ Ringer's solution. The cell's response to three consecutive field stimuli, separated by 2-min recovery periods, was recorded after 6 min in 2 mM Ca2+ Ringer's. The averaged signal indicates complete recovery of the cell's response (right). (D) AP-induced calcium transients were recorded from another neuron before and during exposure to ryanodine under conditions similar to B and C. After recording three control responses (left), the cell was exposed to 50 μM ryanodine (Ry), adding the drug directly to the recording chamber. After 1 min in ryanodine, field stimuli were applied again in every 3 min and the video-rate image sequences of the calcium transients were analyzed as described in A. Early test (middle) or late test (right) data were calculated from the averaged sequence of the first three or the next three calcium responses, respectively, recorded in the presence of Ry. The difference between the early and late Ry data characterizes the use-dependent behavior of Ry. (E) To validate our data with Ry in D, we tested if a significant rundown could be observed in these neurons, under experimental conditions similar to those in D. An example of these sham control data is shown in E. This neuron was stimulated 3× (left) before replacing the bath solution with fresh Ringer's solution, simulating the procedure of adding Ry to the recording chamber. The cell was then stimulated 6× following a protocol similar to that in the presence of Ry in D, and the first and last three Ca2+ responses were signal-averaged and plotted in the middle and right panels, respectively. These data indicate that there was no significant rundown in this cell.

The AP-induced local Ca2+ transient was nearly completely eliminated by the SERCA inhibitor DBHQ (30 μM; Fig. 4 B; and by thapsigargin or cyclopiezonic acid, data not shown), and largely recovered after 30-min washout in DBHQ-free solution (Fig. 4 B). In hot spots from five neurons, DBHQ (30 μM) decreased mean peak ΔF/F0 to 27 ± 7% (p < 0.05) of the pre-DBHQ control value, and 30-min washout of DBHQ restored the mean peak ΔF/F0 to 101 ± 19% of control. Removal of Ca2+ from the external Ringer's solution (by equimolar substitution by Mg2+) rapidly (4 min) and reversibly (1 min) eliminated the local peripheral Ca2+ transient in this (Fig. 4 C) and three other cells tested in this protocol. Finally, the irreversible and use-dependent Ca2+ release channel blocker ryanodine (Ry; 10 μM) gradually decreased the amplitude of the local Ca2+ transients (Fig. 4 D). In hot spots in five neurons, the average peak ΔF/F0 of the first three responses in the presence of 10 μM Ry was 56 ± 2% of the pre-Ry control, and the average of the subsequent three responses was 30 ± 7% (p < 0.05) of control. In parallel studies on three other neurons subjected to the same solution change protocol but in the absence of added Ry (Fig. 4 E), the peak ΔF/F0 of the first three “sham” responses was 90 ± 13% of control and of the subsequent three responses was 79 ± 3% of control, indicating minimal rundown of the local Ca2+ signals in these neurons under control conditions. These results indicate a major role of Ca2+ efflux from the ER via the ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channel in generating the local Ca2+ signals in frog SGNs. Thus, in both bullfrog (Hua et al., 2000; Akita and Kuba, 2000) and grass frog (Rana pipiens; present results) SGNs, CICR may have a close functional coupling to the Ca2+ influx mechanism and the plasma membrane Ca2+ influx must be sufficiently large and rapid (Hernandez-Cruz, 1997) to activate Ca2+ release (Usachev et al., 1997). The structural basis for this strong functional coupling may arise from a concentrated sub-PM localization of the functional ER, as revealed by live-cell staining with BODIPY-ryanodine in both grass frog (Fig. 5 E; see also McDonough et al., 2000) and bullfrog SGNs (Akita and Kuba, 2000).

The ready accessibility of cultured neurons to solution change provided the opportunity for controls of indicator localization and responsiveness, and for localization of intracellular organelles. Membrane permeabilization of a fluo-4 loaded neuron by exposure to saponin (0.1% in intracellular solution) resulted in a rapid and almost complete loss of cell fluorescence after 30–45 s in saponin, demonstrating loss of dye from cytosolic and nuclear volumes within this time (Fig. 5, A and B). The relatively low residual fluorescence after saponin permeabilization (Fig. 5, A and B) is consistent with minimal sequestration of dye into intracellular organelles and with relatively low cellular intrinsic fluorescence compared to the fluo-4 fluorescence in these resting cells. In another neuron, application of the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (2 μM for 5 min in Ringer's solution) caused a uniform increase in fluo-4 fluorescence throughout the peripheral cytoplasmic regions of the cell, and a larger and uniform increase in fluorescence throughout the nucleus (Fig. 5 C). Ca2+ elevation during cell depolarization by elevated (50 mM) K+ Ringer's solution (Friel, 1995; Albrecht et al., 2001) also resulted in a uniform increase in cytoplasmic fluorescence and a larger increase in nuclear fluorescence (Fig. 5 D). Note that the AOI in white in Fig. 5 D (top) exhibited the same fluorescence increase as the rest of the cytoplasmic region (Fig. 5 D, bottom). This same AOI exhibited a local Ca2+ transient in response to a single action potential (Fig. 4 A). The results in Fig. 5, C and D, indicate uniform, but different (Thomas et al, 2000) dye responsiveness to elevated Ca2+ throughout either the peripheral cytoplasm or throughout the nucleus. Thus, the local peripheral hot spots for Ca2+ release observed after action potentials are unlikely to be due to local peripheral pockets of highly responsive dye molecules. Cell staining with BODIPY Ry (100 nM for 10 min in Ringer's solution) and TMRE (1 μM for 1 min, followed by continuous exposure to 0.1 μM, both in Ringer's solution) revealed that the RyR release channels are located in an annulus at the periphery of the cell, and that the mitochondria are concentrated in a zone interior to the peripheral RyR-rich annulus (Fig. 5 E), in accordance with our earlier results (McDonough et al., 2000).

To further rule out the possibility of unresponsive dye in some regions in electrical stimulation experiments, AOIs that were nonresponsive after a single action potential were shown to be capable of responding during a more massive and prolonged increase in total cytosolic Ca2+ produced by a train of stimuli. A neuron in which the response to a single AP was detected at a peripheral hot spot (Fig. 6 A, arrow) was subsequently stimulated using a train of 26 electric field stimuli (2-ms duration each) at 250 Hz (Fig. 6 B). The local response to the single AP is presented by the briefer duration (thin) record in the pair of superimposed records at the pink AOI in Fig. 6, C and D. The neuron exhibited a local peripheral site of Ca2+ release (pink) in response to a single AP (thin trace), with little or no change in fluorescence outside this hot spot (green, red, and olive thin traces, Fig. 6 C). In contrast, the train of stimuli induced a longer and more slowly decaying change in fluorescence (thicker, more slowly decaying pink record in Fig. 6, C and D) at the hot spot for a single AP, and resulted in large signals in peripheral AOIs (green, red, and olive thick traces, Fig. 6 C) that did not respond to the single stimulus. These results indicate that AOIs which did not respond after a single action potential did indeed contain responsive dye. In response to the train of action potentials, the fluorescence signal spread decrementally from the periphery into the cell from both the hot spot for a single AP (pink thick trace) and from the region that did not respond after a single AP (red thick trace). The smaller amplitude signal for the train (thick pink) than for the single AP (thin pink) at the hot spot may be indicative of some rundown of Ca2+ release over time (e.g., Fig. 4 E) in the cell.

FIGURE 6.

Nonuniform Ca2+ responses to single APs are not the result of uneven dye distribution. A cultured SGN was loaded with fluo-4 AM and was then stimulated 3× with a 2-ms long electric pulse, with 2-min breaks between experiments, to generate single APs. The resulting Ca2+ signals were recorded at video rate and corresponding video frames in each sequence were averaged after the experiment. (A) The first eight frames of the signal-averaged series, followed by the frame recorded after a 2-min break. The ΔF/F0 time course of the averaged single-AP responses is plotted in dotted lines at four peripheral AOIs (C), or at two radially arranged sets of AOIs (D). This cell had one hot spot for Ca2+ release, in the peripheral perinuclear area (olive-green). (B) The same cell was then exposed to a train of 26 field stimuli at 250 Hz, which resulted in a more uniform Ca2+ transient. The fluo-4 fluorescence records of this Ca2+ response are plotted as solid lines in C and D, using the same colors. The cell responded to the train of APs in all of the peripheral and radial AOIs, indicating that the nonuniform Ca2+ signals recorded during single APs were not caused by uneven dye distribution.

Some cultured SGNs exhibit uniform peripheral Ca2+ responses

The majority (74%, above) of cultured SGNs behaved very similarly to intact ganglion cells (Fig. 2) in exhibiting local peripheral hot spots for AP-induced Ca2+ release (Figs. 2, 3, and 6). In contrast, other cultured SGNs responded to single APs with peripherally uniform Ca2+ transients, exhibiting no apparent hot spots. In the neuron shown in Fig. 7, a single AP rapidly increased the fluo-4 fluorescence homogenously around the entire perimeter of the cell, forming a ring of bright fluorescence that then spread partially toward the center of the cell (Fig. 7 A). Note that the Ca2+ transient in the second frame (in which the stimulus was applied) appeared at a time when the process of image acquisition, which progressed from bottom to top of each image, had already completed scanning of the very bottom of the cell. Thus the bottom of the cell remained dark in the second image in Fig. 7 A, and only exhibited increased fluorescence in image 3. The resting fluorescence image (Fig. 7 B) of this cell exhibited a dark region corresponding to the nucleus near the cell periphery (from 3 to 6 o'clock).

FIGURE 7.

Uniform peripheral Ca2+ responses to a single AP in a cultured sympathetic ganglion neuron. In experimental conditions very similar to those in Fig. 3, a cultured SGN was stimulated with single APs and the resulting Ca2+ transients were recorded at video rate. (A) Averaged sequence of video images shows that this cell responded more uniformly to a single AP than the cells in Figs. 2 and 3. (B) The resting fluorescence image, recorded with 16 frames/image online averaging, showing raw fluorescence values. The ring-shaped area of elevated fluorescence is likely the result of dye sequestration within intracellular Ca2+ stores, especially mitochondria, having higher than cytosolic [Ca2+]. The whole-cell average of the single-AP induced ΔF/F0 signal is plotted under the cell's image. The data are shown on the same fluorescence and timescales as in Fig. 7, C and D. (C) ΔF/F0 values were calculated for the six indicated AOIs at the cell periphery, and plotted against time in the same colors as the AOIs. The olive-green AOI was drawn in the peripheral perinuclear zone. The records confirm that this cell responded with a uniform Ca2+ transient to single APs. (D) The radial spread of the ΔF/F0 signal from the red and olive-green AOIs in C. The larger signal amplitude in the nuclear area (second and third olive-green curves) may in part be caused by different dye characteristics within the nucleus. All AOIs were the same in size and shape (in C and D), and were at a constant distance from the PM (in C) or at constantly increasing distances from the PM (in D). (E) The distance versus time to half-peak correlation for this cell, both in the nuclear (olive-green circles) and nonnuclear (red triangles) zones. (F) Same data as E, but on a square-root timescale. The data were calculated and plotted as described in Figs. 2 and 3.

To assay the uniformity of the fluorescence signals at different points around the periphery of the cell in Fig. 7, we selected peripheral AOIs around the perimeter of the cell, and calculated the time course of fluorescence averaged over each of these AOIs. The AOIs are indicated as colored areas around the edge of the cell, and the corresponding time courses of ΔF/F0 are plotted around the image of the cell, using the same colors (Fig. 7 C). The time courses of both the rising (<33 ms) and decaying phases (114 ms ≤ t1/2 ≤ 175 ms; mean ± SD = 137 ± 21 ms, six different AOIs) of the fluorescence signals at various AOIs around the periphery of this neuron were all relatively rapid and quite similar, although their amplitude varied somewhat with location. The spread of the fluorescence change from the periphery into the cell interior through the nucleus (bottom, olive; see Fig. 7 B) and through the cytosolic region across the cell from the nucleus (top, red) are illustrated in Fig. 7 D. The time course of the fluorescence change became slower with increasing radial distance from both the perinuclear and nonnuclear cell peripheries (Fig. 7 D). It is possible that the increased amplitude signals seen in the nucleus compared to the peripheral AOI just outside the nucleus is an artifact due to different properties of fluo-4 in the nuclear and cytosolic environments (Thomas et al, 2000). The data in Fig. 7, E and F, indicate that Ca2+ spread mainly via passive diffusion inside the nucleus, whereas Ca2+ release from the ER contributed significantly to the spread of the nonnuclear Ca2+ signal (red symbols) in this cell with peripherally uniform response, as in the cells exhibiting peripheral hot spots.

The rise and fall of fluorescence was relatively rapid at all regions around the periphery of the uniformly responding cell in Fig. 7. In contrast, in the nonuniformly responding neurons the decay of fluorescence was generally slower in the nonnuclear than in the nuclear peripheral primary release sites. In a sample of 38 cells selected for uniform peripheral responses, 25 cells exhibited rapid decay of ΔF/F0 in both the nuclear and nonnuclear regions, having a mean t1/2 for decay of 322 ± 109 ms in the perinuclear periphery and 209 ± 58 in a similar size region roughly across the cell from the nucleus. In 13 other cells with uniform peripheral responses, t1/2 was >1.5 s in the perinuclear and/or the nonnuclear peripheral AOI. The t1/2 value for the nuclear zone was 121 ± 45 ms (mean ± SD) for cells with slow decay only in the nonnuclear AOIs (n = 3). The average nonnuclear t1/2 was 290 ± 123 ms for the cells with slow decay only in the nuclear AOI (n = 3).

The decay half-times at the periphery, and radial propagation properties from the periphery for the nuclear and nonnuclear hot spots are summarized in Table 1. Three categories of cells were considered: neurons in intact ganglia, cultured cells with nonuniform responses, and cultured cells with uniform responses. Overall, there seems to be little difference in these properties in each category of these cells. Thus, the newly responding peripheral regions that have appeared in culture in those cultured cells exhibiting uniform peripheral responses may have similar properties as the hot spots in nonuniformly responding cells. A possible basis for the appearance of cells exhibiting uniform peripheral responses in culture might be that the Ca2+ transport capability of ER in initially nonresponsive peripheral regions of these cells became more developed during culture. In that case, the ER Ca2+ content could increase in the initially nonresponsive regions of the ER, thereby potentiating the ER CICR capability such that the entire peripheral ER might release Ca2+ in response to the Ca2+ influx during an action potential. Alternatively, Ca2+ entry could be localized in cells exhibiting hot spots, but be more uniform in cells exhibiting uniform peripheral responses. In any case, Table 1 indicates that the Ca2+ handling properties of actively releasing peripheral regions appeared to be very similar in neurons of intact ganglia, and in cultured neurons exhibiting uniform or nonuniform peripheral Ca2+ release.

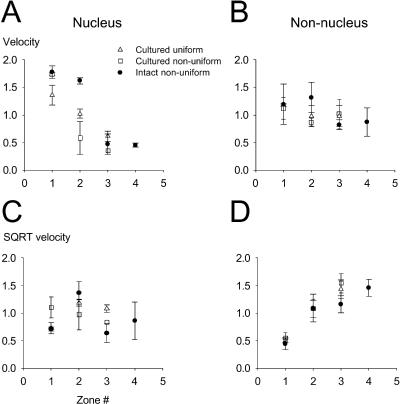

TABLE 1.

Decay and propagation properties of Ca2+ transients in neurons in intact ganglia and in culture

| Intact | Cultured nonuniform | Cultured uniform | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cells | 7 | 23 | 7 |

| Decay half-time at periphery | |||

| Nonnuclear (ms) | 240 ± 26 | 195 ± 15 | 113 ± 26 |

| Nuclear | 281 ± 42 | 330 ± 60 | 350 ± 110 |

| Radial propagation from periphery | |||

| Linear velocity into cytoplasm (μm ms−1/2) | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.01 |

| Square-root velocity into nucleus (μm ms−1) | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.76 ± 0.19 |

Decay times from peak to half-maximum at peripheral hot spots were calculated in seven cells from intact ganglia, as well as in 23 cultured neurons exhibiting nonuniform peripheral Ca2+ responses. Decay times at the periphery of cultured cells with uniform peripheral responses were collected from seven cells in the unbiased sample. In the cultured uniform cells, the decay half-times were calculated at one AOI in the peripheral perinuclear zone and in another peripheral AOI of similar size and shape approximately across the cell from the nucleus. These two AOIs corresponded to the perinuclear and nonnuclear hot spots in neurons of intact ganglia and in cultured neurons exhibiting nonuniform Ca2+ responses. The eighth uniformly responding cell of the unbiased sample (not included in the table) had a half-time decay >1 s in both the nuclear and nonnuclear periphery, which thus could not be estimated using our l-s sampling interval. Propagation from the nuclear AOI through the nucleoplasm was characterized by the square-root velocity, whereas the linear velocities were used to determine the rate of propagation through the nonnuclear ER-rich zone (see Figs. 2, 3, and 7).

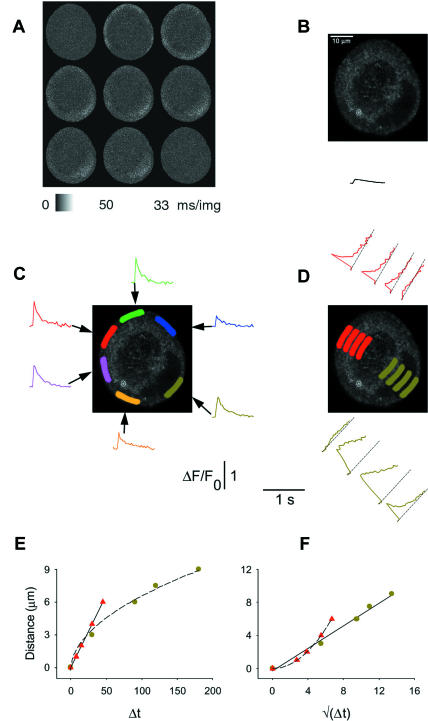

Passive diffusion and active spread of Ca2+ in intact and cultured neurons

Calcium spread from the perinuclear hot spot through the nucleus, or from the nonnuclear hot spot into the cytosol, was carried out by different mechanisms: the spread was passive in the nucleus but actively promoted, presumably by Ca2+ release from the ER, in the nonnuclear zone (Fig. 2 F and G; Fig. 3, E and F; and Fig. 7, E and F). To characterize the average behavior of the three main groups of cells (cells in intact ganglia, cultured cells with local peripheral Ca2+ responses, and cultured cells with peripherally uniform Ca2+ responses), the linear and square-root rates of Ca2+ spread were calculated for 3–4 pairs of neighboring AOIs, arranged radially at gradually increasing distances from the PM, and averaged according to the location of the AOIs (see figure legends for more details). The data in Fig. 8, A and B, show the mean values of the linear velocity for the nuclear (left) and nonnuclear (right) AOIs. These results demonstrate that the linear velocity of Ca2+ spread decreases with distance from the plasma membrane in the nuclear areas, but not in the nonnuclear region for all three groups of cells. These results point out the difference between the passive diffusion and facilitated spread mechanisms characterizing the nuclear and nonnuclear areas, respectively. If the nuclear diffusion mechanism were purely passive, the velocity calculated with the square-root values of the relative half-maximum time (see Fig. 8 legend) would be constant throughout the radial spread. In Fig. 8, C and D, we show the average square-root velocity values for the nuclear (left) and nonnuclear (right) zones. These data clearly indicate that the main mechanism of Ca2+ spread in the nuclear zone is passive diffusion, whereas the spread of Ca2+ in the nonnuclear zone is promoted, probably by CICR via the RyRs of the ER.

FIGURE 8.

Average velocities of Ca2+ diffusion in intact and cultured neurons. The linear velocity of Ca2+ diffusion was calculated by dividing the difference in distance of each AOI from the PM by the difference in time to half-peak of the Ca2+ signal at that AOI for a set of 3–4 AOIs arranged radially (see Fig. 2 legend). The individual velocities were then averaged according to the zone number, where the zone number indicates the relative radial location of the two AOIs. A shows the linear velocities for the nuclear AOIs, whereas B contains the data for the nonnuclear AOIs. To distinguish between passive diffusion and facilitated spread, the square-root velocities were also calculated for all three cell groups, both in the nuclear (C) and nonnuclear (D) areas. The square-root velocity was calculated as a ratio of the difference in distance of the two AOIs from the PM (in μm) and the difference in the square roots of the time to half-peak [in (ms)1/2 ] of the Ca2+ signal at those AOIs. Individual square-root velocities were averaged according to the zone number, as described for A and B (above). Data in A–D are plotted as sample mean ± SD for intact cells (solid circles), cultured cells with uniform Ca2+ responses (unfilled triangles), and cultured cells with nonuniform Ca2+ transients (unfilled squares).

The mean rates of facilitated spread of Ca2+ from the nonnuclear hot spots were 0.09, 0.11, and 0.13 μm/ms in cells in intact ganglia and in cultured cells exhibiting hot spots or uniform peripheral Ca2+ release, respectively. These values are similar to the velocities of a Ca2+ wave in cardiac myocytes (Cheng et al., 1996). In contrast to the constant velocity of spread across the nonnuclear peripheral ER, the velocity of spread decreased across the nucleus (Figs. 2 F, 3 E, 7 E, and 8). Assuming diffusion across the nucleus from an instantaneous point source in the perinuclear ER, the effective diffusion constants were calculated from Crank (1975) and Yao et al. (1995) as

|

(1) |

Applying Eq. 1 at the half-peak concentration and time results in

|

(2) |

where slope is the slope of the distance versus square-root time curve (see Figs. 2 G, 3 F, and 7 F, olive circles and linear fitted line). The mean effective diffusion constant calculated from the square-root velocity of Ca2+ spread across the nucleus in the same group of cells was 0.3, 0.24, and 0.20 μm2/ms.

Rapid rising phase of peripheral calcium transients revealed by high-speed line-scan imaging

Our data from full frame video-rate images indicate that the peripheral fluorescence signal jumped from its resting level to a near maximum value from one XY image to the next at the hot spots for Ca2+ release (Figs. 2, 3, and 6) and around the periphery in uniformly responding cells (Fig. 7). Thus, the rise of calcium transients at such locations was actually too fast to be resolved using the full-frame video-rate confocal XY imaging. To gain more information about the activation kinetics of the calcium transients, fluo-4 fluorescence data were therefore collected in line-scan mode, which could in principle provide a time resolution of 63 μs/ data point at each pixel location along the scan line. However, due to the noise in the images, in practice we averaged 10 successive lines (at 63 μs/line) to create an image at 630 μs/line. In the line-scan experiments, we used cultured cells with uniform peripheral responses so that any line location crossing the cell would pass through two active regions for Ca2+ release, one where the scan line crossed each edge of the cell. Fluorescence data were continuously collected along a single scan line running through the nucleus of the cell (Fig. 9 A, top), and the neuron was stimulated to produce an AP.

FIGURE 9.

Line-scan confocal recordings of an AP-induced calcium transient. Calcium transients were induced by 0.5-ms field stimuli and the sequences of line-scan images were collected from a neuron at 63 μs/line. (A) (Top) XY image of the resting neuron with the scan line indicated. (Bottom) The line-scan image (480 lines/image) overlapping the time of the field stimulus. The color-coded data curves on the right indicate time- and spatially averaged relative fluorescence data, corresponding to the areas covered by the base of the color-coded arrowheads. The thin gray lines connect each record to its AOI: the record at the bottom (green) corresponds to the peripheral perinuclear zone, whereas the records directly above it (pink and olive) describe the behavior of intranuclear areas. The top three records (red, blue, and cyan) describe the behavior of the nonnuclear periphery. To improve signal/noise, each group of 10 successively acquired lines was averaged to give the 630-μs/data point records in A–E. (B, C) The red, blue, and green records are plotted on an expanded timescale. Records in C were normalized to unity; the reference data point is shown by the vertical arrow in B. These results indicate that the rate of rise of calcium is very high at the nonnuclear periphery (red and blue) and in the peripheral perinuclear zone (green). The activation rate of the ΔF/F0 response was very similar in these three areas, all of which were chosen from the ER-rich zone. (D, E) The entire time course of the ΔF/F0 response in all six areas.

Fig. 9 A (bottom), shows the averaged line-scan (Xt) image collected from a neuron during repeated APs. The nucleus is located just inside the bottom edge of the line-scan image. From this image it appears that the fast spread of calcium through the nonnuclear ER-rich periphery (top) suddenly comes to a halt at ∼6 μm from the PM. This may be due to strong mitochondrial calcium uptake in the mitochondrial-rich zone just inside the peripheral ER-rich layer (McDonough et al., 2000; Akita and Kuba, 2000; Fig. 5 E). The location and the size of the selected AOIs are indicated by the position and the base-width of the color-coded arrowheads, respectively, at the right edge of the line-scan image. The color-coded records at the far right of Fig. 9 A, corresponding to each arrowhead, indicate the ΔF/F0 values spatially averaged over the respective AOIs. The ΔF/F0 time course is shown only for the line-scan image frame that included the field stimulus, giving a total record duration of 30 ms. In Fig. 9 B we replot data from Fig. 9 A on an expanded timescale, to compare the fluorescence time course in the outermost ER-rich zones in the neuron (red, blue, and green). The red and blue records characterize the calcium transient in the nonnuclear periphery (Fig. 9 A, top), whereas the green record shows similar data from the peripheral perinuclear area (bottom). Comparison of the three records indicates that the activation kinetics of the calcium transients in these three ER-rich areas were very similar. The initiation time and the rate-of-rise were nearly identical, and the three curves reached their peak essentially simultaneously, as indicated by the arrow in Fig. 9 B. To be able to compare the activation kinetics more directly, we normalized the original ΔF/F0 values to the peak value measured at the downward arrow in Fig. 9 B. The normalized curves (Fig. 9 C) show that any possible difference between the activation rates of these three lines was not resolvable in the present recording.

The full time course of the calcium transients in all six AOIs is shown in Fig. 9, D and E, on a compressed timescale. The successively less peripheral AOIs in the nonnuclear ER-rich periphery (Fig. 9 D, red, blue, and cyan) behaved kinetically similarly, although the amplitudes became gradually lower as areas farther inside the cell were examined. The fluorescence time course in the AOIs within the nucleus (Fig. 9 E, olive and pink) was very different from that in the peripheral perinuclear ER-rich area (Fig. 9 E, green). The peripheral perinuclear ER-rich zone exhibited a marked initial peak, whereas the fluorescence in the intranuclear regions only gradually increased to the same fluorescence level. These differences are probably due to the lack of ER Ca2+ stores and of active Ca2+ transporters within the nucleus. The overall conclusion from these line-scan data is that fluo-4 fluorescence in the peripheral ER-rich zone rises from a resting level to a peak value in <∼5 ms in response to a single action potential. The radial propagation of elevated Ca2+ appears to be extremely rapid within the peripheral ER-rich region, since we see no detectable difference of the time-to-peak within a 4–6-μm thick shell at the cell periphery (Fig. 9 C).

Addition of cytosolic EGTA reveals latent hot spots in cultured SGNs having uniform peripheral responses

The hot spots for initiation of AP-induced Ca2+ transients (Figs. 2, 3, and 6) may correspond to regions in the subplasma membrane ER with the strongest CICR. In that case, the uniformly responding cells might simply have sufficiently developed CICR mechanism throughout the entire sub-PM ER to locally initiate CICR over the entire cell periphery in response to an AP (Fig. 7). However, these cells might still have areas where CICR is stronger than elsewhere, but our experiment would not have revealed them under control conditions. If such latent hot spots were indeed present in the uniformly responding cells, they might be revealed by the addition of an intracellular Ca2+ buffer that could silence the less powerful sites, but not totally suppress the more powerful sites of Ca2+ release. In seven cultured cells with uniform peripheral responses, we used a relatively slow Ca2+ buffer (EGTA) in an attempt to reveal possible latent hot spots.

Fig. 10 A shows control ΔF/F0 records from the corresponding color-coded peripheral AOIs in a neuron that exhibited uniform peripheral Ca2+ transients in response to a single AP under control conditions. Fig. 10 B illustrates the radial spread of elevated fluorescence across the nucleus from the peripheral AOI near 1 o'clock (olive-green) and into the cytosol from a peripheral AOI near 10 o'clock (red) under control conditions. Subsequently, after loading the same cell with EGTA AM, the cell's response to APs became nonuniform in the same AOIs around the cell periphery (Fig. 10 C). A peripheral AOI area within the perinuclear zone (olive-green, near 1 o'clock) and several areas in the nonnuclear periphery now acted as primary sites for Ca2+ release, with other peripheral AOIs giving no change in fluorescence. The very fast decay of ΔF/F0 (t1/2 ≤ 30 ms) in all responsive areas of the EGTA-loaded cells is consistent with Ca2+ binding to EGTA, which lowers the free Ca2+ much more rapidly after cessation of Ca2+ release than in the absence of added Ca2+ buffer. Furthermore, the radial spread seen in the AOIs in Fig. 10 B under control conditions was completely eliminated after loading the cell with EGTA (Fig. 10 D), even though the peripheral AOI at each of the locations examined in Fig. 10 D still exhibited a definite, but very brief, fluorescence signal in response to the action potential. This is also consistent with EGTA binding of released Ca2+, thereby restricting the diffusional spread of Ca2+ away from the release site.

FIGURE 10.

EGTA reveals latent hot spots in neurons with uniform peripheral Ca2+ transients. Calcium transients were induced by 0.5-ms field stimuli in a cultured frog SGN and the video sequences for responses to four stimuli were averaged. (A) Time course of ΔF/F0 in the seven indicated color-coded peripheral AOIs. The olive-green AOI was drawn in the peripheral perinuclear zone. The calcium transients were uniform in all peripheral AOIs. (B) The radial spread of the fluorescence signals was characterized inside the nucleus (olive-green) and at the site of the largest nonnuclear peripheral response (red). In both regions, the fluorescence signal spread with a slower rise time and decrement in amplitude, but remained detectable throughout. (C and D) The same cell was loaded with EGTA AM (20 μM; 15 min) in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. The AP protocol was then repeated 15× in the presence of 2 mM extracellular Ca2+ and the calcium transients were recorded from the same AOIs as in A and B. (C) The EGTA treatment eliminated the calcium response in many but not all AOIs. Two subareas on the left (red and pink) and one on the right (orange) still showed a significant, but now very rapidly decaying response. The perinuclear area also remained responsive (olive-green). (D) The Ca2+ signal did not spread radially when the cell was loaded with the Ca2+ buffer EGTA. The other two responsive peripheral AOIs (orange and cyan) gave similar results (not shown).

In two other uniformly responding cells, application of 10 or 20 μM of the faster Ca2+ buffer BAPTA (AM) for 15 min totally eliminated the calcium transient in response to single APs (data not shown). Thus, BAPTA was able to sufficiently limit any local rise in Ca2+ so that no detectable CICR response occurred.

Lowered extracellular Ca2+ also reveals latent hot spots in cultured SGNs having uniform peripheral responses

Another way to decrease CICR, and thus possibly reveal latent hot spots in uniformly responding cultured SGNs, was to expose these cells to lowered extracellular Ca2+ concentration. This was achieved via a local perfusion system that completely replaced the extracellular solution around a SGN within 2 s (Cseresnyés et al., 1997; McDonough et al., 2000). In these experiments, a cell was first tested with a single AP in the presence of normal (2 mM) extracellular Ca2+ and the resulting Ca2+ response was recorded. The cell was then exposed to 0.1 mM extracellular Ca2+ Ringer's solution for 6–24 s, after which a single AP was again applied. The cell was then returned to 2 mM extracellular Ca2+ Ringer's and an AP-induced Ca2+ response was again recorded. The protocol of stimulation in 2 mM Ca2+ followed by stimulation after 6–24 s in low Ca2+ Ringer's was repeated 3–4×. The video sequences for either 2 or 0.1 mM Ca2+ were averaged separately. The duration of the low-Ca2+ flush was selected by trial and error so that the resulting Ca2+ release pattern became inhomogeneous, but was not totally eliminated. In the majority of the cells, 6 s was sufficient. The location of the active areas was not sensitive to moderate prolongations of the low-Ca2+ flush. However, when the low-Ca2+ flush was further prolonged, the Ca2+ response to an action potential was totally eliminated, sometimes irreversibly.