Abstract

Group B streptococci (GBS) are among the most common causes of life-threatening neonatal infections. Vaccine development since the late 1970s has focused on the capsular polysaccharides, but a safe, effective product is still not available. Our quest for a vaccine turned to the streptococcal C5a peptidase (SCPB). This surface protein is antigenically conserved across most if not all serotypes. A murine model was used to assess the impact of SCPB on clearance of GBS from the lungs of intranasally infected animals. Mutational inactivation of SCPB resulted in more-rapid clearance of streptococci from the lung. Immunization with recombinant SCPB alone or SCPB conjugated to type III capsular polysaccharide produced serotype-independent protection, which was evidenced by more-rapid clearance of the serotype VI strain from the lungs. Immunization of mice with tetanus toxoid-type III polysaccharide conjugate did not produce protection, confirming that protection induced by SCPB conjugates was independent of type III polysaccharide antigen. Histological evaluation of lungs from infected mice revealed that pathology in animals immunized with SCPB or SCPB conjugates was significantly less than that in animals immunized with a tetanus toxoid-polysaccharide conjugate. These experiments suggest that inclusion of C5a peptidase in a vaccine will both add another level to and broaden the spectrum of the protection of a polysaccharide vaccine.

Group B streptococci (GBS) are the leading cause of meningitis, pneumonia, and sepsis in neonates. They are also a prominent cause of peripartum maternal infections, causing an estimated 50,000 cases annually (2). A child usually acquires GBS through perinatal transmission from the mother's genital tract. Development of a GBS vaccine began 2 decades ago, after Baker and Kasper reported a correlation of maternal antibody deficiency with susceptibility to neonatal GBS infection (4). Immunity to GBS was associated with maternal antibodies to the type-specific capsular polysaccharides (Cps). Therefore, vaccine development has focused on the polysaccharide capsules. However, in animal models, protection by Cps is highly specific, and cross protection by the different serotypes does not occur. The number of different capsular serotypes has increased to nine and will likely increase more in the future. Those serotypes responsible for invasive GBS disease in the United States are restricted with few exceptions to types Ia, Ib, II, III, and V. Vaccine development has been directed primarily at serotypes Ia and III, because these strains are the predominant cause of meningitis in neonates (27). Human vaccine trials with polysaccharides of types Ia, II, and III have shown low and variable levels of specific antibodies following immunization of volunteers (5). With changing serotype distribution and the emergence of new serotypes, multivalent GBS vaccines have become of interest (17).

Protein-polysaccharide conjugates have proven more effective than polysaccharides alone for prevention of bacterial infections. Tetanus toxoid (TT) and several GBS surface proteins (6), alpha C protein (16, 26), Rib protein (26), and beta C protein (28), have been tried as the carrier. Our laboratory has focused on the streptococcal C5a peptidase (SCPB) (18, 37). All group A streptococcal serotypes and group B, C, and G streptococci of human origin produce the peptidase. SCPB is a multifunctional surface-bound protease which specifically inactivates the human phagocyte chemotaxin C5a (7, 37) but also binds to fibronectin and promotes invasion of epithelial cells by GBS (6a, 12). Bohnsack et al. showed that SCPB-deficient GBS were cleared more rapidly from mice that were supplemented with human C5a following lung infection (7). Antibody directed against recombinant SCPB was found to be opsonic and to induce macrophage killing of various serotypes of GBS (11). Furthermore, SCPB is an effective immunogenic carrier of type III Cps (CpsIII). Immunization of mice with conjugates resulted in high immunoglobulin G (IgG) titers being directed against both CpsIII and SCPB (11). In this study, we used a murine model to investigate the role of SCPB in the pathogenesis of GBS infecting lungs and demonstrated that subcutaneous immunization with either recombinant SCPB alone or SCPB-Cps conjugates results in more-efficient clearance of GBS from lungs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

GBS strain O90R (unencapsulated) and an SCPB deletion mutant, O90R(Del), have been described previously (12). GBS serotype VI strain S2-02288 was used for challenge of immunized animals, because this serotype was reported to be substantially more virulent for mice (34). Streptococci were grown on blood agar plates or in Todd-Hewitt broth to mid-log phase by incubation at 37°C until the optical density at 560 nm was 0.5 to 0.6. They were then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in PBS so that the appropriate concentrations for mouse inoculations could be obtained.

Whole-blood phagocytosis (24).

GBS from mid-log-phase cultures (optical density at 560 nm of 0.5 to 0.6) were washed with PBS and diluted to a concentration of approximately 1,000 CFU/50 μl. Diluted GBS (1,000 CFU) was added to 950 μl of heparinized whole blood from healthy human donors and incubated at 37°C on a rotator for 3 h. To quantify GBS survival, 100-μl samples were taken at 0 and 3 h after incubation. Samples were plated on Todd-Hewitt agar with 5% sheep blood. The number of CFU per milliliter was determined after overnight incubation of plates at 37°C.

GBS association with PMNs by flow cytometry.

Assays were carried out according to the method described by Ji et al. (21). Mid-log-phase biscarboxyethyl-carboxyfluorescein-pentaacetoxy-methylester (BCECF-AM)-labeled GBS were incubated with whole blood for 20 min at 37°C. One-hundred-microliter samples were mixed with 2 ml of FACScan lysing solution (Becton Dickinson). Cells were washed with PBS-Ca2+ and resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS-Ca2+ for flow cytometry analysis. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) were fluorescent only when associated with GBS, and 10,000 PMN events were recorded.

SCPB purification and C5a peptidase activity measurement.

SCPB from serotype II strain 78-471 was expressed from pGEX plasmids in Escherichia coli strain BL21 and purified as previously described (31). SCPBw contains amino acids 89 to 1037, with D130 and S512 being replaced by Ala. C5a peptidase activity was measured using the fluorescent fusion protein glutathione transferase-human C5a-green fluorescent protein (GST-hC5a-GFP) bound to Sepharose beads (31). Release of GFP by peptidase activity was measured with a Bio-Tek FL600 fluorescence reader. The purity of proteins was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce).

Purification of polysaccharide and conjugation protocol.

CpsIII was purified according to the method of Deng et al. (14). Purified SCPB and SCPBw were coupled by reductive amination to purified polysaccharide that was first oxidized with periodate by using the method reported by Wessels et al. (36). Conjugates were analyzed for their protein and carbohydrate contents. Purified SCPB and CpsIII were used as the standards.

Immunization protocol.

The vaccines, TT, SCPB, CpsIII-TT, CpsIII-SCPB, and CpsIII-SCPBw, were prepared by mixing 5 μg of antigen with 100 μg of AlPO4 (alum) in a 50-μl volume and incubating overnight at 4°C. The next day, 50 μg of mycobacterial phospholipid adjuvant (RIBI Immunochem Research, Hamilton, Mont.) was added, resulting in a total dose volume of 100 μl. Four-week-old female CD1 mice (Charles River Laboratories) were immunized subcutaneously at the scruff of the neck with 5 μg of antigen/dose. Mice were then boosted at weeks 4 and 6 with 5 μg of antigen in adjuvant. Ten days after the final booster injection, the mice were bled and sera from individual mice were saved. Mice were then challenged 13 days after the final booster injection with strain S2-02288.

Analysis of mouse antisera.

Mouse IgG specific for SCPB and SCPBw antigens was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) on microtiter plates coated with 250 ng of protein per well. Mouse serum samples were serially diluted, beginning at a 1:2,000 dilution, for postvaccination sera. Goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to alkaline phosphatase was used as the secondary antibody. The plate was developed for 30 min after addition of the substrate, and the titer is reported as the reciprocal dilution that resulted in an absorbance greater than that of the negative controls ± 2 standard errors of the mean (immunized with TT). Anti-CpsIII antibody titers were also determined by endpoint dilution as previously described (11).

Immunofluorescence was used to analyze whether mouse antisera were able to neutralize the C5a peptidase activity. Sera were diluted 1:50 in PBS-1% bovine serum albumin, and then 100-μl samples were mixed with 250 ng of SCPB. The mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 2 h and then added to 20 μl of a GST-hC5a-GFP bead suspension. After incubation for 45 min at room temperature, released GFP was measured with a Bio-Tek FL600 fluorescence reader. Neutralization was calculated as the percentage of inhibition of SCPB activity by serum at a 1:50 dilution.

Infection of mice.

Each experimental group consisted of 15 to 20 mice. The mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and inoculated with 40 to 50 μl of GBS [1010 CFU for O90R and O90R(Del), 108 CFU for S2-02288] in the right nare only. After 5 h, all mice were killed using a CO2 chamber. Both lungs were removed, homogenized, and cultured quantitatively on Columbia blood agar plates. After overnight incubation at 37°C, the number of beta-hemolytic colonies on plates was counted. The bacterial recovery from each lung was expressed as CFU per milligram of lung tissue. The geometric means were calculated for each group.

Histopathology.

One mouse from each infection group and one uninfected mouse were chosen for histopathological examination. Whole lungs were fixed overnight in 10% buffered formalin and then embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Gram stained.

Statistics.

The INSTAT program and the Mann-Whitney U test (unpaired, nonparametric, and two-sided P value) were used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Inactivation of SCPB by deletion increases sensitivity to phagocytosis by human whole blood.

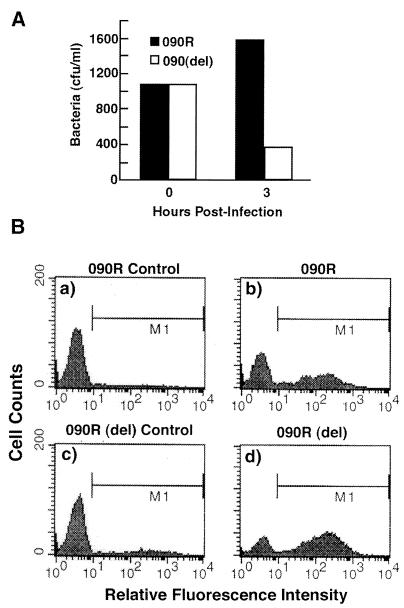

Anti-SCPB antibody was shown to opsonize GBS for phagocytosis in whole blood, suggesting the possibility that this surface protein impairs phagocytosis. This possibility was tested by assessing the sensitivity of an SCPB deletion mutant to phagocytosis. Wild-type strain O90R and a mutant derivative, O90R(Del) (11, 12), which contains a deletion in SCPB that eliminates peptidase, fibronectin, and epithelial cell binding activities, were compared for their capacity to resist phagocytosis by using a whole-blood phagocytosis assay (Fig. 1A). During the 3-h incubation of rotated blood, the parent culture increased in viable count while O90R(Del) decreased by more than 50%. The human blood donor lacked measurable antibody against SCPB. Increased sensitivity to phagocytosis was also assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis (11) to confirm that strain O90R(Del) actually associated with PMNs rather than being killed by bactericidal serum factors. For this assay, both cultures were prelabeled with BCECF-AM and then incubated with whole blood for 20 min at 37°C. The number of green fluorescent PMNs, those associated with GBS, was measured by flow cytometry (11). Under the conditions employed, 41% of the PMNs became associated with the SCPB+ O90R streptococci, whereas 61% of the PMNs were associated with strain O90R(Del) (Fig. 1B, panels b and d). Panels a and c of Fig. 1B show the fluorescence profile of PMNs prior to incubation with labeled bacteria. Therefore, as predicted by the classical phagocytosis assay, strain O90R(Del) associated with PMNs more readily than did wild-type streptococci, indicating that SCPB influences the capacity of GBS to resist phagocytosis.

FIG. 1.

Impact of SCPB on sensitivity to phagocytosis. (A) Phagocytosis of strains 090R and 090R(Del) by human whole blood. Data shown are from a single experiment but are representative of five independent experiments. (B) Association of strains 090R and 090R(Del) with PMNs in human whole blood. M1 bars represent PMNs with fluorescence greater than that of uninfected PMNs. Counts are the number of cells; a total of 10,000 cells were counted.

Clearance of SCPB deletion strain O90R(Del) from adult mouse lungs.

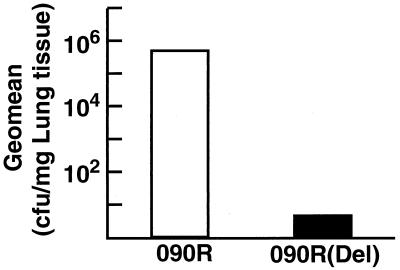

The increased susceptibility of strain O90R(Del) to phagocytosis prompted us to further evaluate the relative importance of SCPB in the pathogenesis of GBS. The lung is a likely focus of infection leading to early-onset neonatal sepsis. Therefore, a mouse model of lung infection was employed to assess the clearance of streptococci following intranasal infection. Wennerstrom and Schutt used both neonatal and adult mice to study pulmonary defenses against GBS (35). The above-mentioned experiments suggested that SCPB might retard the clearance of streptococci from mucosal tissues. The inoculum size needed to produce consistent lung infections following intranasal administration of GBS to 10-week-old mice was determined (see Materials and Methods). A preliminary time course experiment indicated that 5 to 7 h postinfection was the optimal time to evaluate the persistence of streptococci in the lung. Therefore, mice were sacrificed at that time postinfection, and lungs were removed and homogenized and the number of viable GBS per milligram of tissue was determined. No significant differences in the numbers of viable streptococci of the SCPB+ and SCPB deletion strains per milligram of lung tissue were observed 30 min after inoculation (data not shown). However, by 5 h after inoculation, fewer viable O90R(Del) streptococci (4.8 CFU/mg) than wild-type O90R streptococci (5.3 × 105 CFU/mg) were recovered from homogenized lungs (Fig. 2). This difference was determined to be statistically significant (P = 0.02). These in vivo results are consistent with in vitro phagocytosis experiments and further support the conclusion that SCPB contributes to the virulence of GBS.

FIG. 2.

Clearance of strains 090R and 090R(Del) from adult mouse lungs 5 h postinfection. Data are from three independent experiments and are presented as geometric means (CFU per milligram of lung tissue). Experimental groups contained 11 mice. The differences between the results for strains 909R and 909R(Del) were significant (P = 0.02).

Immunogenicity of SCPB and SCPB-CpsIII conjugates in mice.

Previous data showed that SCPB is a highly effective immunogenic carrier when chemically conjugated to CpsIII (11). Therefore, immunization experiments were performed to determine whether vaccination with SCPB alone or with SCPB-CpsIII conjugate would induce serotype-independent protection in mice. Groups of 20 mice were immunized subcutaneously with TT and SCPB or with polysaccharide conjugates (TT-CpsIII, SCPB-CpsIII, or SCPBw-CpsIII) at weeks 0, 4, and 6. Serum antibodies (IgG) specific for SCPB or CpsIII were measured by ELISA. Mean antibody titers in sera taken after the final antigen booster injection are shown in Table 1. All vaccines produced a vigorous serum IgG response against both SCPB and CpsIII. Mice that were immunized with SCPB uniformly produced significant titers of antibodies that neutralized C5a peptidase activity. At a 1:50 dilution, antisera from mice immunized with SCPB alone neutralized, on average, 80% of the C5a peptidase activity, whereas antisera from mice immunized with SCPB-CpsIII conjugates neutralized 64.5% of the activity (data not shown). Although the antibody response to SCPB-CpsIII (full-length protein) appeared to be greater than that to the truncated SCPBw-CspIII conjugate, the differences in total antibody titers and percentages of neutralization were not statistically significant. The anti-TT and anti-SCPB antibody titers in sera from mice immunized with polysaccharide conjugates were comparable (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Immunogenicity of conjugate vaccines

| Specific antibody | Antibody titer (geometric mean)a after immunization of mice with:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT | SCPB | TT-CpsIII | SCPB-CpsIII | SCBPw-CpsIII | |

| Anti-SCPB | 0 | 320,000 | 0 | 204,000 | 131,225 |

| Anti-CpsIII | NAb | NA | 14,764 | 8,227 | 7,971 |

The titers of antigen-specific IgG are the geometric means of titers from groups of 15 mice.

NA, not assayed.

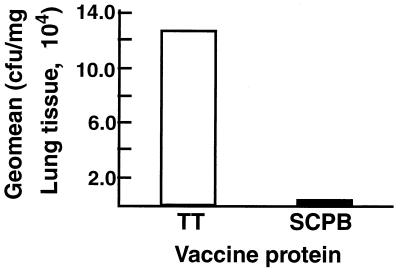

Immunization with SCPB alone enhanced clearance of GBS from mouse lungs.

Previous studies have suggested that immunization with SCPB could provide mice with serotype-independent protection from infection. To test this possibility, mice were immunized with full-length recombinant SCPB that was mixed with alum and mycobacterial phospholipid adjuvant. Control mice were immunized with TT mixed with the same adjuvants. Immunized mice were then challenged with 5 × 108 CFU of strain S2-02288 (serotype VI) by intranasal inoculation. This strain was reported to be somewhat more virulent for mice than other serotypes (34). Five hours after inoculation, the mice were euthanatized and their lungs were removed, homogenized, and assayed for viable GBS (Fig. 3). Significantly fewer GBS were recovered from the lungs of mice immunized with SCPB than from mice immunized with TT. A 100-fold difference in the geometric mean numbers of CFU per milligram of lung tissue was observed, which is a highly statistically significant difference (P = 0.0004).

FIG. 3.

Immunization with SCPB enhances clearance from lungs. The clearance of serotype VI strain S2-02288 from mouse lungs was evaluated 5 h postinfection. Mice were immunized with TT or full-length SCPB. Twenty mice were in each experimental group. Data are from a single experiment but are representative of three independent experiments. Mice were euthanatized, and their lungs were harvested and homogenized in buffer. Homogenates were assayed for viable streptococci. The differences between the results for animals immunized with TT and SCPB were significant (P = 0.0004).

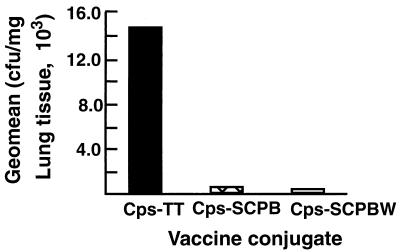

SCPB-CpsIII conjugate vaccines induce serotype-independent protection.

Previous experiments have demonstrated that SCPB is an efficient carrier protein that promotes a strong antibody response to CpsIII, but they did not evaluate whether this resulted in protection from infection (11). We performed an experiment to evaluate the effectiveness of SCPB-polysaccharide conjugates as a vaccine by using the mouse lung clearance model. A second question that was considered was whether the inactive, truncated form of the peptidase, SCPBw, induced protective immunity equivalent to that of the full-length active protein when conjugated to CpsIII. Purified proteins (SCPB and SCPBw) were conjugated with purified CpsIII by reductive amination as described in Materials and Methods. Control mice were immunized with a TT-CpsIII conjugate. The immunized mice were again challenged with 5 × 108 CFU of strain S2-02288 by intranasal inoculation. The results (Fig. 4) show that fewer GBS (50-fold less) were recovered from mice immunized with SCPB-CpsIII or SCPBw-CpsIII conjugant than from mice immunized with TT-CpsIII. The difference between the results for animals immunized with SCPB-CpsIII and SCPBw-CpsIII was small and statistically insignificant. The P value was 0.02 for the differences between mice immunized with SCPB-CpsIII and TT-CpsIII. The P value was 0.05 for the differences between mice immunized with SCPBw-CpsIII and TT-CpsIII. As expected, anti-CpsIII antibody induced by immunization with TT-CpsIII did not enhance clearance of serotype VI streptococci from the lung. These results indicate that chemical conjugation of SCPB to the CpsIII not only enhanced the immunogenicity of the polysaccharide but also broadened the potential protective response to an unrelated serotype.

FIG. 4.

Immunization with SCPB and CpsIII speeds clearance of streptococci from lungs. Mice (20 mice per experimental group) were immunized with CpsIII-TT, CpsIII-SCPB, or CpsIII-SCPBw. Lungs were obtained from mice 5 h after infection with the serotype VI strain S2-02288. Data are from a single experiment but are representative of two experiments. The numbers of CFU per milligram of lung tissue are presented as geometric means. The differences between the results for animals immunized with SCPB-CpsIII and TT-CpsIII were significant (P = 0.02).

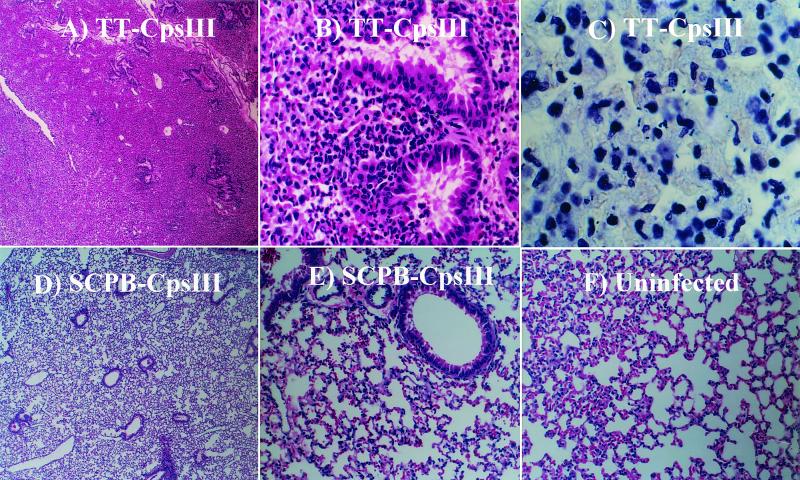

Immunization with SCPB reduces inflammatory damage in the lung.

The lungs of one mouse from each experimental group were sectioned and processed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and Gram staining. Slides were marked in a blind fashion and examined by an experienced surgical pathologist. Lungs from the control mouse, immunized with TT-CpsIII, revealed greater than 90% involvement by bronchopneumonia. Histologic sections showed mild pulmonary edema and an extensive, diffuse inflammatory infiltrate consisting of neutrophils and alveolar macrophages. Focal areas revealed signs consistent with progression to lobar pneumonia (Fig. 5A and B). Both extracellular and intracellular streptococci were readily observed in Gram-stained sections (Fig. 5C). Lungs from mice immunized with SCPB-CpsIII conjugate protein also showed multiple areas of bronchopneumonia; however, less than 30% of the lung was involved. Histologic sections of these lungs showed reduced pulmonary edema and a significantly reduced inflammatory infiltrate compared with samples from TT-treated mice. Inflammation was generally peribronchiolar, with greater sparing of alveolar spaces (Fig. 5D). Sections of lung from the mouse immunized with SCPBw-CpsIII also showed less overall involvement relative to those from a mouse treated with TT-CpsIII (data not shown). For comparison, Fig. 5F shows a section from an uninfected mouse treated with SCPB-CpsIII.

FIG. 5.

Immunization with SCPB reduced pathology in mouse lung. Mice were immunized with TT-CpsIII, SCPB-CpsIII, or SCPBw-CpsIII conjugate. One mouse from each experimental group was euthanatized 5 h after infection with serotype VI strain S2-02288. Lungs were removed, fixed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Sections were either Gram stained (C) or stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A, B, D, E, and F). Representative sections from a mouse immunized with TT-CpsIII (A to C), a mouse immunized with SCPB-CpsIII (D and E), and an uninfected mouse immunized with SCPB-CpsIII (F) are shown. Magnifications, ×40 (A and D), ×200 (B, E, and F), and ×1,000 (C).

DISCUSSION

For almost 3 decades, GBS have been recognized as an important pathogen for newborn children and their mothers. More recently, invasive infections of adults with underlying medical conditions and the emergence of new serotypes have been reported. The incidence of early-onset neonatal GBS infections has decreased somewhat since the maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis was put in practice (3). However, the potential negative consequences of using antibiotics to prevent disease are apparent, and vaccine development is still the preferred strategy for prevention of serious neonatal disease. Moreover, a broadly protective vaccine could also reduce the incidence of invasive disease among elderly adults or those with underlying medical conditions. In both animal models and human trials, capsular polysaccharide conjugate vaccines have been shown to be significantly more immunogenic than polysaccharides alone (3, 11). Several GBS surface proteins are potential candidates for use as stand-alone vaccines and/or carrier proteins. Rib, α, and β proteins have all been shown to induce protection against systemic infection in rodent models (25, 26). However, the production of these proteins varies between strains and serotypes, and their roles in virulence are ill defined. All tested GBS strains of human origin expressed SCPB, and little or no antigenic variability in the protein has been observed (10, 32). Although the contribution of C5a peptidase to the virulence of group A streptococci has been extensively studied (20, 21), its role in GBS infections has received little attention. We and others have proposed that SCPB reduces the recruitment of PMNs to sites of GBS infection by destroying C5a, an early chemoattractant for inflammatory cells (9, 13). More recently, SCPB was found to function also as an invasin by binding to epithelial cells (12). Here, we investigated whether SCPB as either a stand-alone vaccine or a polysaccharide conjugate induces a protective immunological response in mice.

One means by which a newborn is thought to become infected during birth is by aspiration of contaminated amniotic fluid or vaginal secretions. Symptoms of early-onset disease include respiratory distress and shock accompanied by significant pathological changes in the lungs, including interstitial hemorrhage, pneumonia, pulmonary congestion, atelectasis, and the presence of intraalveolar gram-positive cocci (1, 22). The exquisite sensitivity of pneumocytes to the β hemolysin of GBS may be partially responsible for the observed damage to the lung architecture (29). Wennerstrom and Schutt (35) described a mouse model for early-onset GBS disease that resembles human infections. In this model, streptococci were introduced into lungs by intranasal inoculation. Neutrophil recruitment and phagocytosis of aspirated streptococci by alveolar macrophages are expected to be an important early defense against lung infection. This lung model was used to test the efficiency of recombinant SCPB as a vaccine component. Experimental conditions were optimized to produce reproducible numbers of streptococci in the lung. Early clearance of streptococci from lungs served as an indicator of protection. Histological examination of lung tissue revealed massive inflammation, with early signs of pneumonia in control mice 5 h after intranasal inoculation. Immunization with SCPB induced serotype-independent protection. This was reflected both by the diminished number of viable streptococci remaining in lung tissue and by reduced inflammation and pathology in lung sections from immunized mice. Our data show that SCPB is not only a good immunogen on its own but also an effective carrier for polysaccharide antigens. All immunized mice developed high serum titers of IgG antibody against both SCPB and CpsIII antigens. These results are consistent with those of a previous study, which demonstrated that anti-SCPB antibody induces serotype-independent killing of streptococci by bone marrow macrophages and PMNs in whole blood (11). Enhanced clearance of streptococci from mouse lungs is presumably due to the action of these antibodies.

Bohnsack et al. showed that SCPB inactivates C5a preparations from humans, monkeys, and cows but does not inactivate this chemotaxin when it is prepared from rats and mice (8). Therefore, the specific proteolytic action of SCPB enzyme may be irrelevant to the outcome of lung infections in mouse models. Our laboratory and another laboratory recently demonstrated that SCPB is also a fibronectin and epithelial cell binding protein and as such is required for the efficient invasion of A549 and Hep2 epithelial cell lines by GBS (6a, 12). Antibodies against SCPB were found to inhibit GBS invasion of cultured epithelial cells by as much as 50% (12). Therefore, in addition to acting as an opsonin, antibody generated by immunization may prevent GBS from reaching a protective intracellular compartment in the respiratory tract of infected mice. The exquisite in vitro sensitivity of human C5a to SCPB, however, suggests that C5a peptidase activity plays a pivotal role in human infections.

GBS is often carried asymptomatically in the vaginal tract of women, from where it can be transferred to the newborn during parturition. Strains from invasive infections of infants are internalized by epithelial cells more effectively than those from age-match healthy controls (33), suggesting that invasion of epithelial cells has a serious impact on the pathogenesis of GBS. Although GBS do not replicate within respiratory epithelial cells, their ability to enter and survive in these cells may represent a mechanism by which they can gain access to blood circulation (15).

The ideal vaccine should stimulate both local mucosal and systemic immunity and reduce GBS colonization of women of child-bearing age. Serum antibodies might prevent invasive disease, but local or secretory antibodies may be more important for the inhibition of mucosal colonization. Colonization of the rectum or cervix has been suggested to induce a local immune response that protects the neonate from infection (19). Secretory antibodies against polysaccharide antigens were found to diminish colonization of the respiratory tract by Haemophilus influenzae type b in an infant rat model (23). Shen et al. showed that intranasal immunization with polysaccharide-protein conjugates improved the mucosal as well as the systemic immune response to GBS (30).

In conclusion, experiments confirm that SCPB influences the persistence of GBS in the lungs of mice. Subcutaneous immunization with SCPB, either alone or conjugated to Cps, elicits a strong systemic antibody response which can protect mice from infection by encapsulated GBS. Moreover, protection is serotype independent. SCPB is also a good carrier for polysaccharide antigens.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIAID grant AI2006 and a grant from Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines, Inc.

We thank Heather Lane-Brown for assays of anti-CpsIII antibody titers.

Editor: J. D. Clements

REFERENCES

- 1.Ablow, R. C., S. G. Driscoll, E. L. Effmann, I. Gross, C. J. Jolles, R. Uauy, and J. B. Warshaw. 1976. A comparison of early-onset group B streptococcal neonatal infection and the respiratory-distress syndrome of the newborn. N. Engl. J. Med. 294:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker, C. J., and M. S. Edwards. 1995. Group B streptococcal infections, p. 980-1054. In J. S. Remington and J. O. Klein (ed.), Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant, 4th ed. W. B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, Pa.

- 3.Baker, C. J., N. A. Halsey, and A. Schuchat. 1999. 1997 AAP guidelines for prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease. Pediatrics 103:197-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker, C. J., and D. L. Kasper. 1976. Correlation of maternal antibody deficiency with susceptibility to neonatal group B streptococcal infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 294:753-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker, C. J., and D. L. Kasper. 1985. Group B streptococcal vaccines. Rev. Infect. Dis. 7:458-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker, C. J., L. C. Paoletti, M. R. Wessels, H. K. Guttormsen, M. A. Rench, M. E. Hickman, and D. L. Kasper. 1999. Safety and immunogenicity of capsular polysaccharide-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccines for group B streptococcal types Ia and Ib. J. Infect. Dis. 179:142-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Beckmann, C., J. D. Waggoner, T. O. Harris, G. S. Tamura, and C. E. Rubens. 2002. Identification of novel adhesins from group B streptococci by use of phage display reveals that Csa peptidase mediates fibronectin binding. Infect. Immun. 70:2869-2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohnsack, J. F., K. Widjaja, S. Ghazizadeh, C. E. Rubens, D. R. Hillyard, C. J. Parker, K. H. Albertine, and H. R. Hill. 1997. A role for C5 and C5a-ase in the acute neutrophil response to group B streptococcal infections. J. Infect. Dis. 175:847-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohnsack, J. F., J. Chang, and H. R. Hill. 1993. Restricted ability of group B streptococcal C5a prepared from different animal species. Infect. Immun. 61:1421-1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohnsack, J. F., K. W. Mollison, A. M. Buko, J. C. Ashworth, and H. R. Hill. 1991. Group B streptococci inactivate C5a by enzymatic cleavage at the carboxy terminus. Biochem. J. 273:635-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohnsack, J. F., S. Takahashi, L. Hammitt, D. V. Miller, A. A. Aly, and E. E. Adderson. 2000. Genetic polymorphisms of group B streptococcus SCPB alter functional activity of a cell-associated peptidase that inactivates C5a. Infect. Immun. 68:5018-5025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng, Q., B. Carlson, S. Pillai, R. Eby, L. Edwards, S. B. Olmsted, and P. Cleary. 2001. Antibody against surface-bound C5a peptidase is opsonic and initiates macrophage killing of group B streptococci. Infect. Immun. 69:2302-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng, Q., D. Stafslien, S. S. Purushothaman, and P. Cleary. 2002. The group B streptococcal C5a peptidase is both a specific protease and an invasin. Infect. Immun. 70:2408-2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chmouryguina, I., A. Suvorov, P. Ferrieri, and P. P. Cleary. 1996. Conservation of the C5a peptidase genes in group A and B streptococci. Infect. Immun. 64:2387-2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng, L., D. L. Kasper, T. P. Krick, and M. R. Wessels. 2000. Characterization of the linkage between the type III capsular polysaccharide and the bacterial cell wall of group B Streptococcus. J. Biol. Chem. 275:7497-7504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson, R. L., C. Soderland, W. R. Henderson, Jr., E. Y. Chi, and C. E. Rubens. 1995. Group B streptococci (GBS) injure lung endothelium in vitro: GBS invasion and GBS-induced eicosanoid production is greater with microvascular than with pulmonary artery cells. Infect. Immun. 63:271-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gravekamp, C., D. L. Kasper, L. C. Paoletti, and L. C. Madoff. 1999. Alpha C protein as a carrier for type III capsular polysaccharide and as a protective protein in group B streptococcal vaccines. Infect. Immun. 67:2491-2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison, L. H., J. A. Elliott, D. M. Dwyer, J. P. Libonati, P. Ferrieri, L. Billmann, and A. Schuchat. 1998. Serotype distribution of invasive group B streptococcal isolates in Maryland: implications for vaccine formulation. Maryland Emerging Infections Program. J. Infect. Dis. 177:998-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill, H. R., J. F. Bohnsack, E. Z. Morris, N. H. Augustine, C. J. Parker, P. P. Cleary, and J. T. Wu. 1988. Group B streptococci inhibit the chemotactic activity of the fifth component of complement. J. Immunol. 141:3551-3556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hordnes, K., T. Tynning, A. I. Kvam, R. Jonsson, and B. Haneberg. 1996. Colonization in the rectum and uterine cervix with group B streptococci may induce specific antibody responses in cervical secretions of pregnant women. Infect. Immun. 64:1643-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji, Y., L. McLandsborough, A. Kondagunta, and P. P. Cleary. 1996. C5a peptidase alters clearance and trafficking of group A streptococci by infected mice. Infect. Immun. 64:503-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji, Y., N. Schnitzler, D. DeMaster, and P. P. Cleary. 1998. Impact of M49, Mrp, Enn, and C5a peptidase proteins on colonization of the mouse oral mucosa by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 66:5399-5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katzenstein, A. L., C. Davis, and A. Braude. 1976. Pulmonary changes in neonatal sepsis to group B beta-hemolytic Streptococcus: relation of hyaline membrane disease. J. Infect. Dis. 133:430-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kauppi, M., L. Saarinen, and H. Kayhty. 1993. Anti-capsular polysaccharide antibodies reduce nasopharyngeal colonization by Haemophilus influenzae type b in infant rats. J. Infect. Dis. 167:365-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lancefield, R. C. 1962. Current knowledge of the type specific M antigens of group A streptococci. J. Immunol. 89:307-313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsson, C., M. Stalhammar-Carlemalm, and G. Lindahl. 1996. Experimental vaccination against group B streptococcus, an encapsulated bacterium, with highly purified preparations of cell surface proteins Rib and α. Infect. Immun. 64:3518-3523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsson, C., M. Stalhammar-Carlemalm, and G. Lindahl. 1999. Protection against experimental infection with group B streptococcus by immunization with a bivalent protein vaccine. Vaccine 17:454-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin, F. Y., J. D. Clemens, P. H. Azimi, J. A. Regan, L. E. Weisman, J. B. Philips III, G. G. Rhoads, P. Clark, R. A. Brenner, and P. Ferrieri. 1998. Capsular polysaccharide types of group B streptococcal isolates from neonates with early-onset systemic infection. J. Infect. Dis. 177:790-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madoff, L. C., L. C. Paoletti, J. Y. Tai, and D. L. Kasper. 1994. Maternal immunization of mice with group B streptococcal type III polysaccharide-beta C protein conjugate elicits protective antibody to multiple serotypes. J. Clin. Investig. 94:286-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nizet, V., R. L. Gibson, E. Y. Chi, P. E. Framson, M. Hulse, and C. E. Rubens. 1996. Group B streptococcal beta-hemolysin expression is associated with injury of lung epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 64:3818-3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen, X., T. Lagergard, Y. Yang, M. Lindblad, M. Fredriksson, and J. Holmgren. 2000. Preparation and preclinical evaluation of experimental group B streptococcus type III polysaccharide-cholera toxin B subunit conjugate vaccine for intranasal immunization. Vaccine 19:850-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stafslien, D. K., and P. P. Cleary. 2000. Characterization of the streptococcal C5a peptidase using a C5a-green fluorescent protein fusion protein substrate. J. Bacteriol. 182:3254-3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suvorov, A. N., P. P. Cleary, and P. Ferrieri. 1991. C5a peptidase gene from group B streptococci, p. 230-232. In G. Dunny, P. P. Cleary, and L. McKay (ed.), Genetics and molecular biology of streptococci, lactococci, and enterococci. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 33.Valentin-Weigand, P., and G. S. Chhatwal. 1995. Correlation of epithelial cell invasiveness of group B streptococci with clinical source of isolation. Microb. Pathog. 19:83-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Hunolstein, C., S. D'Ascenzi, B. Wagner, J. Jelinkova, G. Alfarone, S. Recchia, M. Wagner, and G. Orefici. 1993. Immunochemistry of capsular type polysaccharide and virulence properties of type VI Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococci). Infect. Immun. 61:1272-1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wennerstrom, D. E., and R. W. Schutt. 1978. Adult mice as a model for early onset group B streptococcal disease. Infect. Immun. 19:741-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wessels, M. R., L. C. Paoletti, D. L. Kasper, J. L. DiFabio, F. Michon, K. Holme, and H. J. Jennings. 1990. Immunogenicity in animals of a polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine against type III group B Streptococcus. J. Clin. Investig. 86:1428-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wexler, D., E. D. Chenoweth, and P. Cleary. 1985. A streptococcal inactivator of chemotaxis: a new virulence factor specific to group A streptococci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:179-180. [Google Scholar]