Abstract

Wild-type and mutant thin filaments were isolated directly from “myosinless” Drosophila indirect flight muscles to study the structural basis of muscle regulation genetically. Negatively stained filaments showed tropomyosin with periodically arranged troponin complexes in electron micrographs. Three-dimensional helical reconstruction of wild-type filaments indicated that the positions of tropomyosin on actin in the presence and absence of Ca2+ were indistinguishable from those in vertebrate striated muscle and consistent with a steric mechanism of regulation by troponin-tropomyosin in Drosophila muscles. Thus, the Drosophila model can be used to study steric regulation. Thin filaments from the Drosophila mutant heldup2, which possesses a single amino acid conversion in troponin I, were similarly analyzed to assess the Drosophila model genetically. The positions of tropomyosin in the mutant filaments, in both the Ca2+-free and the Ca2+-induced states, were the same, and identical to that of wild-type filaments in the presence of Ca2+. Thus, cross-bridge cycling would be expected to proceed uninhibited in these fibers, even in relaxing conditions, and this would account for the dramatic hypercontraction characteristic of these mutant muscles. The interaction of mutant troponin I with Drosophila troponin C is discussed, along with functional differences between troponin C from Drosophila and vertebrates.

INTRODUCTION

Contraction in all muscles results from the relative sliding of thick and thin filaments. In a repetitive cycle of attachment and dissociation, myosin cross-bridges that project from thick filaments advance along the actin-based molecular track of thin filaments, driving the contractile process (Huxley, 1969). Mechanisms that switch contraction on and off prevent muscles from being permanently contracted or non-functional. In all muscle types, contraction is initiated by an increase in the sarcoplasmic concentration of free Ca2+ ions, which bind to regulatory proteins. During relaxation, Ca2+ is sequestered and dissociates from these target proteins (reviewed in Tobacman, 1996). Although different protein systems regulate the activity of different muscle types, the thin filament-linked troponin-tropomyosin complex is involved in controlling most, if not all, striated muscles, including the asynchronous indirect flight muscles (A-IFM) of insects (Lehman and Szent-Györgyi, 1975). (The A-IFM are additionally modulated by stretch (Pringle, 1978) and myosin phosphorylation (Takahashi et al., 1990).) It is generally accepted that a “steric” regulatory mechanism governs the activity of these muscles, where a change in position of tropomyosin strands running along thin filaments acts as a molecular switch (Huxley, 1972; Haselgrove, 1972; Parry and Squire, 1973; Lehman et al., 1994). In relaxed muscles at low Ca2+, tropomyosin is constrained by troponin (Tn) I and T of the troponin complex in a position blocking myosin binding sites on actin. Ca2+ binding to Tn C releases this constraint and allows tropomyosin movement to occur and actin and myosin to interact (Tobacman, 1996; McKillop and Geeves, 1993; Vibert et al. 1997). The initial binding of myosin heads on actin causes an additional shift in tropomyosin position, further increasing the probability of myosin binding cooperatively and leading to myosin cross-bridge cycling and contraction. (Tobacman, 1996; McKillop and Geeves, 1993; Vibert et al., 1997).

The indirect flight muscles of insects are an excellent model system to investigate the structural basis of muscle contraction and its regulation. A-IFM are composed of the same major myofibrillar proteins found in other muscles, and the precise lattice arrangement of thick and thin filaments in these striated muscles facilitates structural investigation (Reedy et al., 1965; Ashhurst and Cullen, 1977; Bullard et al., 1988; Ruiz et al., 1998). A-IFM of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, in particular, are amenable to genetic manipulation, and mutations specific for Drosophila A-IFM protein isoforms typically affect flight, but not the viability, of laboratory bred flies (Bernstein et al., 1993). However, the steric mechanism of thin filament regulation has never been demonstrated directly in the A-IFM of Drosophila or any other insect (cf. Ruiz et al., 1998), and hence the genetic advantages of this system could not be fully exploited to investigate troponin-tropomyosin regulation. In this study, we have developed a simple method to isolate thin filaments from Drosophila A-IFM and have demonstrated by electron microscopy (EM) and three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction that the positions of tropomyosin in the presence and absence of Ca2+ are indistinguishable from those in vertebrate muscle thin filaments (Lehman et al., 2000). We have also demonstrated the great potential of Drosophila A-IFM as a genetic model for studying thin filament regulation by characterizing the underlying structural basis for the dramatic hypercontraction in the flightless heldup (hdp2) Drosophila strain, a mutant with a single amino acid conversion in Tn I (Beall and Fyrberg, 1991).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thin filament isolation

Thirty thoraces dissected from either anesthetized myosin heavy chain mutation Mhc7 or hdp2; Mhc12 “myosinless” Drosophila served as starting material. The genetic alteration in the myosinless Mhc12 Drosophila strain is similar to that in Mhc7 Drosophila; in each strain, myosin heavy chains fail to accumulate in the A-IFM and therefore thick filament assembly does not occur. The Mhc12 strain available has identifiable phenotypic markers, b, el, and cn flanking the myosin gene, and these markers were useful in following the Mhc12 mutation in subsequent crosses. Crosses of b el Mhc12 cn Drosophila with hdp2 flies possessing an f marker were carried out by standard procedures to obtain a stable double mutant hdp2; Mhc12 stock. Balancer chromosomes were used to suppress chromosome recombination.

To solubilize cell membranes and extract nonfilamentous soluble proteins and nucleotides, the thoraces were “chemically skinned” in 0.1% saponin overnight by gentle agitation in a 10-ml “rigor solution” consisting additionally of 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 1 mM NaN3, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mM sodium phosphate/PIPES buffer (pH 7.0) at 4°C. The skinned material was then rinsed with the same solution lacking saponin, and homogenized in 0.8 ml fresh buffer in a glass homogenizer. Homogenates were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 25 min to sediment particulate material, including trace amounts of thin filaments still bound in rigor to thick filaments and presumably derived from non-A-IFM muscles. A-IFM thin filaments were collected from the supernatant by sedimentation at 100,000 × g for 30 min and thin filament pellets resuspended in 0.2 ml rigor buffer with a 25-gauge syringe needle. Before preparation for EM, samples were diluted 2- to 10-fold either with the above buffer or the same buffer with 0.1 mM CaCl2 added in excess of the EGTA present.

Rabbit skeletal muscle F-actin and troponin complexes containing mutant CBMII cardiac Tn C but wild-type cardiac Tn I and Tn T were prepared as before (Spudich and Watt, 1971; Tobacman et al., 1999; Morris et al., 2001). Stoichiometric amounts of the troponin complex were mixed with bovine cardiac tropomyosin (Tobacman and Adelstein, 1986) and the troponin-tropomyosin added to a suspension of F-actin (10 μM) in the above buffer in a 2:7 molar ratio (troponin-tropomyosin/actin), and diluted 10 times for EM.

Electron microscopy and 3D reconstruction

Negative staining and electron microscopy

Five μl of thin filaments in either EGTA or Ca buffer were applied to carbon-coated EM grids (at ∼25°C), negatively stained with 1% (w/v) uranyl acetate and dried at 80% relative humidity to aid in spreading the stain (Lehman et al., 1994; Vibert et al., 1997). EM images were recorded at 80 kV on a Philips CM120 EM (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at 60,000× magnification under low dose conditions (∼12 e−/Å2) at a defocus of 0.5 μm.

3D reconstruction

Micrographs were digitized using a Zeiss SCAI scanner (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) at a pixel size corresponding to 0.7 nm in the filaments, and well-preserved regions of the filaments were selected and straightened as previously (Lehman et al., 1994; Vibert et al., 1997). Helical reconstruction, which resolves actin monomer structure and tropomyosin strands, but not troponin position or structure (Lehman et al., 2001), was carried out by standard methods (Owen et al., 1996). The statistical significance of densities in reconstructions was evaluated from the standard deviations associated with contributing points (Milligan and Flicker, 1987; Trachtenberg and DeRosier, 1987).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Thin filament isolation from Drosophila A-IFM

Extraction of A-IFM thin filaments from insect muscle homogenates by routine procedures is ineffective, even though thin filaments are easily prepared from other insect muscle types (Lehman et al., 1974). This is, in part, because I-bands of A-IFM sarcomeres are extremely short, and interdigitating thick and thin filaments overlap almost completely. We therefore exploited the genetic advantages of the Drosophila system to isolate A-IFM thin filaments from myosinless (Mhc7 or Mhc12) strains that lack A-IFM thick filaments but are otherwise normal (Chun and Falkenthal, 1988; Bernstein et al., 1993). Although thick filaments do not accumulate in the flight muscles, thin filaments are apparently unaffected, develop normally, form I-bands and can be isolated directly and prepared free of contaminants with minimal processing (see Material and Methods section). Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis (not shown) confirmed the purity of these preparations, and we and others (Chun and Falkenthal, 1988; Bernstein et al., 1993; Ruiz et al., 1998) demonstrated that actin, tropomyosin, and troponin components are present in thin filaments of myosinless A-IFM in normal ratios.

Electron microscopy of isolated thin filaments

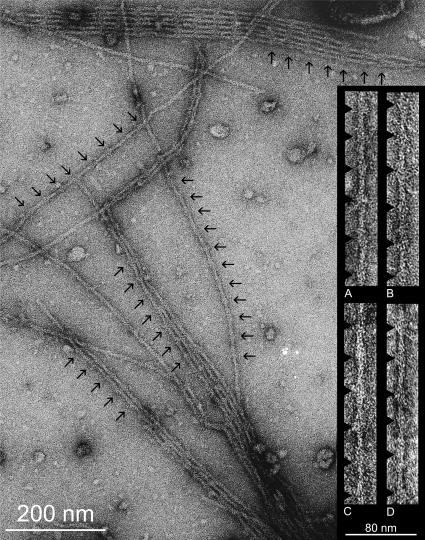

Negative staining demonstrated that purified extracts of Mhc7 A-IFM were replete with thin filaments and free of thick filaments and other particulate material (Fig. 1). A-IFM thin filaments (Fig. 1), isolated in EGTA and either maintained in EGTA or treated with Ca2+, showed the characteristic double helical distribution of actin subunits and occasionally exhibited longitudinally oriented elongated tropomyosin strands. They also displayed periodic bulges, representing the globular end of the troponin complex that repeated at characteristic 38-nm intervals (Lehman et al., 1994, 2000, 2001). Although we have not quantified the mass or the dimensions of the troponin bulges in micrographs of A-IFM filaments, they are visibly larger than those present in vertebrate thin filaments (cf. Lehman et al., 1995), consistent with biochemical and structural evidence first presented by Bullard, Leonard, and colleagues (Bullard et al., 1988; Wendt and Leonard, 1999). Filaments were often linked together laterally by an apparent association of their troponin complexes, and sometimes as many as 20–30 thin filaments interacted to form “rafts” composed of a single layer of filaments.

FIGURE 1.

Electron micrographs of negatively stained Drosophila IFM thin filaments. A low magnification field showing single thin filaments, paired filaments, and filament rafts isolated from Mhc7 myosinless flies. The globular ends of troponin (indicated by black arrows) are evident as bulges repeating at 38-nm intervals and are most easily seen by viewing filaments at a glancing angle. Filament pairs and rafts apparently are joined together by troponin molecules. (Inset) Examples of filaments used for image processing from the IFM of (A and B) Mhc7 or (C and D) hdp2; Mhc12 mutants isolated in EGTA (A and C) or treated with Ca2+ (B and D). Single filaments typically were chosen for image processing, but reconstruction of loosely paired filaments was also possible, and invariably both filament types yielded the same results.

3D reconstruction of A-IFM thin filaments

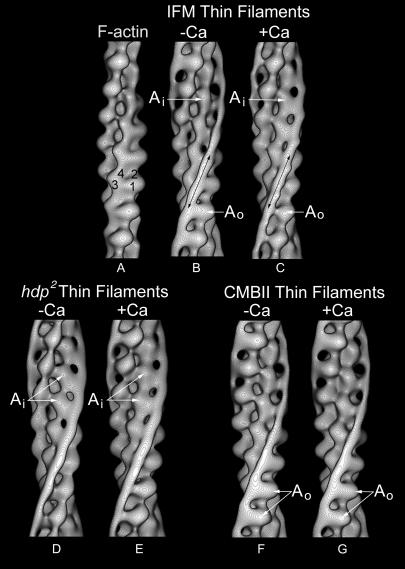

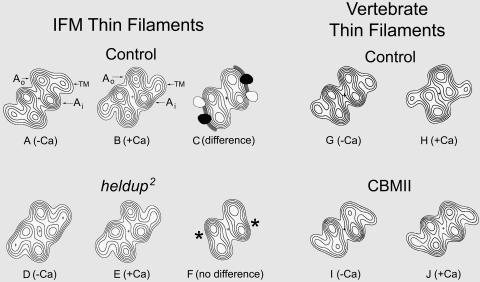

To determine the 3D structure of the negatively stained A-IFM thin filaments, 3D reconstructions were calculated for filaments in EGTA or Ca2+ using helical analysis (Owen et al., 1996). Density maps determined for pure F-actin served as controls. Surface views and helical projections of averaged data showed typical two-domain actin monomers that could be further divided into subdomains (Figs. 2 and 3). In addition, longitudinally continuous strands of density followed the long-pitch actin helices of all thin filaments processed. These strands were not present in the F-actin control and were assumed to represent primarily tropomyosin, as they were virtually identical to tropomyosin strands observed in actin-tropomyosin (no troponin) controls and thin filaments reconstructed from other muscles (Lehman et al., 1994, 2000). In the presence of EGTA, the tropomyosin strands contacted actin monomers along the inner edge of their outer domains (Figs. 2 and 3). In contrast, in Ca2+, tropomyosin contacted the inner domains of actin monomers (Figs. 2 and 3). Difference density analysis, subtracting maps of one set of data from the other, demonstrated that the Ca2+-dependent change in the association of tropomyosin with actin was significant at better than the 99.95% confidence level (Fig. 3). In the absence of Ca2+,A-IFM tropomyosin was located over known myosin binding sites on actin (Milligan et al., 1990) in a position that could block myosin binding in relaxed muscles. Our results showing tropomyosin movement away from the blocking position on addition of Ca2+ are consistent with the presence of the steric mechanism of regulation in A-IFM, and the two distinctive positions for tropomyosin in A-IFM filaments are indistinguishable from those found in vertebrate striated muscle filaments (Lehman et al., 2000).

FIGURE 2.

Surface views of reconstructed thin filaments showing the position of tropomyosin strands on actin. (A) F-actin control (actin subdomains numbered on one monomer); (B–E) Drosophila filaments from Mhc7 (B and C) and hdp2; Mhc12 (D and E) strains; (F and G) reconstituted thin filaments containing mutant CBMII Tn C and otherwise wild-type vertebrate cardiac troponin-tropomyosin components. Reconstructions are of samples maintained in the absence of Ca2+ (B, D, and F) or treated with Ca2+ (C, E, and G). Tropomyosin strands indicated by black arrows in B and C. Note that the tropomyosin density in B, F, and G is associated with subdomain-1 of each actin monomer and bridges over subdomain-2 of successive monomers along the long-pitch actin helix (on the inner edge of the outer domain of actin (Ao)). In C, D, and E), tropomyosin is associated with subdomain-3 and bridges over subdomain-4 of successive actin monomers (on the outer edge of the inner domain of actin (Ai)). Thus, Ca2+-dependent movement of tropomyosin occurs in filaments from Mhc7 IFM, but not from hdp2; Mhc12 mutant IFM or from filaments containing CBMII Tn C. In the case of hdp2; Mhc12, tropomyosin is trapped on the inner domain of actin and, in the CMBII mutant, on the outer actin domain. The average phase residuals (±SD), a measurement of the agreement among filaments generating reconstructions, for the 15 filaments in each Drosophila data set were 58.0 ± 5.6°, 56.2 ± 7.0°, 55.8 ± 6.0°, and 54.8 ± 5.8°, respectively. The average up-down phase residuals, a measure of filament polarity, were 23.9 ± 6.6°, 24.4 ± 8.2°, 19.1 ± 5.5°, and 28.5 ± 7.9°, respectively, values comparable to those previously found. The average angular rotations between adjacent actin monomers along the genetic helix of the Drosophila filaments were 167.1 ± 0.7°, 167.0 ± 0.9°, 167.3 ± 1.4°, and 167.1 ± 1.3°, respectively, consistent with a 28/13 helix.

FIGURE 3.

Helical projections (formed by projecting component densities in reconstructions down the long-pitch actin helices onto a plane perpendicular to the thin-filament axis) showing axially averaged positions of F-actin and tropomyosin (TM) that appear symmetrical on either side of the filament. Densities in all maps shown were significant over background noise at greater than the 99.95% confidence levels. Drosophila filaments from Mhc7 (A and B) and hdp2; Mhc12 mutants (D and E); vertebrate filaments containing wild-type troponin (G and H); or mutant CBMII troponin (I and J). Reconstructions are of samples maintained in the absence of Ca2+ (A, D, G, and I) or treated with Ca2+ (B, E, H, and J). Again, note that Ca2+-dependent movement of tropomyosin occurs in filaments from Mhc7 IFM, but not in those from hdp2; Mhc12 mutants or from reconstituted filaments containing CBMII Tn C instead of control vertebrate troponin. The statistical significance of the differences observed between maps of Mhc7 IFM filaments in EGTA or Ca2+ conditions was computed. The regions of the two maps that were significantly different from each other at greater than the 99.95% confidence level are displayed as single contour envelopes superimposed on the control map of F-actin (C); densities specific to EGTA (solid black) or Ca2+ (open) highlight the tropomyosin movement and the tropomyosin binding positions on actin. The myosin-binding sites on actin are indicated by gray bands in C. No significant differences were detected between contributing densities forming the EGTA and Ca2+ maps of the hdp2; Mhc12 mutants (F), confirming that tropomyosin movement did not occur; an asterisk marks the tropomyosin-binding site on actin in hdp2 filaments.

hdp2 A-IFM thin filaments

Drosophila has a single gene that encodes Tn I (Barbas et al., 1993). A point mutation at residue 116 (Ala to Val) in constitutive exon 5 of Tn I causes the hdp2 Drosophila flightless phenotype characterized by abnormal “heldup” wing posture. This results from a hypercontraction that shears apart the A-IFM (Beall and Fyrberg, 1991; Nongthomba et al., 2003), and the ensuing muscle destruction can be easily visualized by polarized light microscopy as in Nongthomba et al. (2003). To study the effects of the hdp2 mutation on thin filament regulation, filaments were extracted from the A-IFM of hdp2; Mhc12 “double mutants” by the same procedure used above. EM of these thin filaments showed normal actin filament substructure, troponin bulges, and tropomyosin strands, and confirms the results of others that thin filament ultrastructure and protein composition appear unaffected by the hdp2 mutation (Beall and Fyrberg, 1991; Nongthomba et al., 2003). However, in marked contrast to our results on normal thin filaments, 3D reconstruction of filaments isolated from the double mutants showed that Ca2+ had no significant effect on tropomyosin position (Figs. 2 and 3). Tropomyosin was in the “Ca2+-induced” position on the inner domain of the actin whether Ca2+ was present or not. Hence, steric regulation is disabled in hdp2 filaments, and myosin binding sites on actin are exposed even in relaxing conditions. Thus, in A-IFM with thick filaments and ATP, unimpeded cross-bridge cycling would account for the hypercontraction in hdp2 flies.

How hdp2 leads to defective steric regulation is unclear. Drosophila residue Ala-116 corresponds to a conserved alanine at position 25 in the vertebrate skeletal muscle Tn I sequence in an N-terminal α-helix that makes hydrophobic contacts with Cys-98, Ile-101, and Phe-102 of the Tn C “E helix” (Vassylyev et al., 1998; Tanaka et al., 2003). The subtle increase in residue size may alter the Tn I-C interface and destabilize the Tn I association with actin and tropomyosin and, therefore, steric regulation. As most Mhc mutations suppress the hdp2 phenotype, any weakening of acto-myosin interactions might diminish hypercontraction and thus the accompanying muscle destruction (Kronert et al., 1999; Nongthomba et al., 2003). Further interpretation awaits an atomic structure of Ca2+-free troponin and a detailed model of its interactions with tropomyosin and actin (cf. Tanaka et al., 2003). In contrast, models of actin-tropomyosin interaction are available (Phillips et al., 1986; Brown et al., 2001), and the ability to dissect the impact of the hdp2 mutation on tropomyosin position both genetically and structurally validates our approach. Thus, it should be possible to analyze other previously described or newly designed Drosophila mutants to determine structural effects on the actin monomer, F-actin helical symmetry, and steric regulation.

Tn C and Ca2+-induced tropomyosin movements

Although the mechanism of steric regulation in insect and vertebrate muscles is comparable, the mass of troponin in insects, and in arthropods in general, differs from that of troponin in vertebrates. A-IFM Tn I and T, for example, contain protein extensions not present in vertebrate troponin (Bullard et al., 1988; Barbas et al., 1993). The functional significance of these variations and of unique thin-filament components in some insect muscles is not known (cf. Bernstein et al., 1993). In addition, Tn C, the most conserved of the troponin subunits, also differs in the A-IFM. Amino acid substitutions in three of the four EF hands in DmTnC4 (Qiu et al., 2003), the major A-IFM Tn C isoform, leave only one metal-binding motif to regulate troponin-tropomyosin interactions. (In the A-IFM system, a minor Tn C isoform (DmTnC1) present in ∼10% of the total troponin, binds two Ca2+; that isoform and DmTnC4 apparently are randomly distributed among troponin complexes along thin filaments (Qiu et al., 2003). The Tn C in molluscs, like DmTnC4, also binds Ca2+ only at site IV (Lehman et al., 1980; Ojima et al., 2000).) In contrast, vertebrate skeletal muscle Tn C contains four active EF hands, consisting of two low-affinity Ca2+-specific binding sites (I and II) located at the N-terminal lobe of the dumbbell-like protein, and two high-affinity Ca2+/Mg2+-exchange binding sites (III and IV) at the C-terminal lobe. (Tn C in vertebrate cardiac muscle contains three active EF hands, consisting of one low-affinity site (II), and two high-affinity sites (III and IV) (Tobacman, 1996).) Only the low-affinity sites I and II bind Ca2+ rapidly enough to control skeletal and cardiac muscle. In vertebrates, sites III and IV are thought to be purely structural, not regulatory (reviewed in Tobacman, 1996). Interestingly, in DmTnC4, only the C-terminal lobe EF hand corresponding to the type IV site is capable of binding Ca2+ (Qiu et al., 2003). This is surprising since engineered vertebrate Tn C mutants that lack active sites I and II (but retain sites III and IV) do not activate myosin ATPase or support force in skinned fibers, because Tn I-T inhibition cannot be relieved by Ca2+ (Morris et al., 2001). Reconstruction of filaments reconstituted with this mutant vertebrate “CBMII” TnC showed that in this system neither site III nor site IV is sufficient for Ca2+-dependent tropomyosin shifts, even when given time to bind Ca2+. Tropomyosin in these mutant vertebrate filaments, in fact, was in the blocked state both in the presence and absence of Ca2+ (Figs. 2 and 3). Thus, in the vertebrate system, Ca2+ binding to low-affinity binding sites (and not to high-affinity ones) is necessary for the tropomyosin movement. This observation highlights the differences between Drosophila and vertebrates in the function of Tn C EF hands at site IV. Unlike that in vertebrates, site IV in Drosophila is likely to be regulatory, and by binding Ca2+ responsible for steric regulation by tropomyosin. Despite the possibility that insect Tn C may display fairly tight Ca2+ binding (Qiu et al., 2003), the relative affinities of Ca2+ and Mg2+ presumably combine to give an apparent Ca2+ affinity at site IV that accounts for a Ca2+-activation of A-IFM myofibrillar ATPase comparable to that in vertebrate striated muscle (Marston and Tregear, 1974). It is intriguing that the hdp2 mutation involves part of Tn I that interacts with the C-lobe of Tn C, not with the N-lobe, and that the hdp2 mutation leads to defective steric regulation. This adds credence to the premise that in Drosophila and possibly other invertebrates the C-lobe may be regulatory.

Our studies have specifically addressed the structural mechanism of troponin-tropomyosin-linked Ca2+ regulation in the A-IFM. It is well known that the rhythmic contraction of A-IFM used for insect flight is not based on cyclic alternation in Ca2+ levels but is dependent instead on alternation between stretch-activation and release-deactivation (Pringle, 1978; Tregear et al., 1998). How a troponin-tropomyosin-linked steric blocking mechanism can be designed to be partly dependent on stretch-activation is an unsolved but exciting question for future investigation. The effect of Ca2+ binding to troponin-tropomyosin explored here, and necessary in vertebrate and invertebrate synchronous muscles, must be more complex in A-IFM, particularly since these muscles are likely to be additionally modulated by myosin-phosphorylation.

We have demonstrated that Drosophila A-IFM thin filaments can be easily isolated from myosinless flies and then studied structurally by electron microscopy and 3D reconstruction. Overall our results show that thin filament regulation in the vertebrate and insect systems is very similar, but that much remains to be learned from the A-IFM model by the comparative genetic and structural approach taken.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. I. Bernstein for providing Mhc7 mutant Drosophila and J. Moore for discussions.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HL36153 (to W.L.), AR34711, HL62468 (to R.C.), and HL38834 (to L.S.T.); a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (United Kingdom) grant (to J.C.S.); and NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant RR08426 (to R.C.) supporting electron microscopy facilities. NIH training grant HL007291 (C. Akey, principal investigator) partly supported A.C. This work was carried out using the Core Electron Microscopy Facility of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, supported in part by Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center grant DK32520. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

L. S. Tobacman's present address is Depts. of Medicine and of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Medicine, Chicago, IL 60612-7342.

References

- Ashhurst, D. E., and M. J. Cullen. 1977. The structure of fibrillar flight muscle. In Insect Flight Muscle. R. T. Tregear, editor. North Holland Publishing, Amsterdam. 9–14.

- Barbas, J. A., J. Galceran, L. Torroja, A. Prado, and A. Ferrus. 1993. Abnormal muscle development in the heldup3 mutant of Drosophila melanogaster is caused by a splicing defect affecting selected Tn I isoforms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:1433–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall, C. J., and E. Fyrberg. 1991. Muscle abnormalities in Drosophila melanogaster heldup mutants are caused by missing or aberrant troponin-I isoforms. J. Cell Biol. 114:941–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, S. I., P. T. O'Donnell, and R. M. Cripps. 1993. Molecular genetic analysis of muscle development, structure, and function in Drosophila. Int. Rev. Cytol. 143:63–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. H., K. H. Kim, G. Jun, N. J. Greenfield, R. Dominguez, N. Volkmann, S. E. Hitchcock-DeGregori, and C. Cohen. 2001. Deciphering the design of the tropomyosin molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:8496–8501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, B., K. Leonard, A. Larkins, G. Butcher, C. Karlik, and E. Fyrberg. 1988. Troponin of asynchronous flight muscle. J. Mol. Biol. 204:621–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun, M., and S. Falkenthal. 1988. Ifm(2)2 is a myosin heavy chain allele that disrupts myofibrillar assembly only in the indirect flight muscle of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 107:2613–2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselgrove, J. C. 1972. X-ray evidence for a conformational change in actin-containing filaments of vertebrate striated muscle. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 37:341–352. [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, H. E. 1969. The mechanism of muscular contraction. Science. 164:1356–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, H. E. 1972. Structural changes in actin- and myosin-containing filaments during contraction. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 37:361–376. [Google Scholar]

- Kronert, W. A., A. Acebes, A. Ferrus, and S. I. Bernstein. 1999. Specific myosin heavy chain mutations suppress troponin I defects in Drosophila muscles. J. Cell Biol. 144:989–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, W., B. Bullard, and K. Hammond. 1974. Calcium-dependent myosin from insect flight muscles. J. Gen. Physiol. 63:553–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, W., R. Craig, and P. Vibert. 1994. Ca2+-induced tropomyosin movement in Limulus thin filaments revealed by three dimensional reconstruction. Nature. 368:65–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, W., V. Hatch, V. Korman, M. Rosol, L. Thomas, R. Maytum, M. A. Geeves, J. E. Van Eyk, L. S. Tobacman, and R. Craig. 2000. Tropomyosin isoforms modulate the localization of tropomyosin strands on actin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 302:593–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, W., J. F. Head, and P. W. Grant. 1980. The stoichiometry and location of troponin I- and troponin-C-like proteins in the myofibril of the bay scallop, Aequipecten irradians. Biochem. J. 187:447–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, W., M. Rosol, L. S. Tobacman, and R. Craig. 2001. Troponin organization on relaxed and activated thin filaments revealed by electron microscopy and three-dimensional reconstruction. J. Mol. Biol. 307:739–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, W., and A. G. Szent-Györgyi. 1975. Regulation of muscular contraction. Distribution of actin control and myosin control in the animal kingdom. J. Gen. Physiol. 66:1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, W., P. Vibert, P. Uman, and R. Craig. 1995. Steric-blocking by tropomyosin visualized in relaxed vertebrate muscle thin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 251:191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston, S., and R. T. Tregear. 1974. Calcium binding and the activation of fibrillar insect flight muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 347:311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKillop, D. F. A., and M. A. Geeves. 1993. Regulation of the interaction between actin and myosin subfragment-1: Evidence for three states of the thin filament. Biophys. J. 65:693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, R. A., and P. F. Flicker. 1987. Structural relationships of actin, myosin, and tropomyosin revealed by cryo-electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 105:29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, R. A., M. Whittaker, and D. Safer. 1990. Molecular structure of F-actin and the location of surface binding sites. Nature. 348:217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C. A., L. S. Tobacman, and E. J. Homsher. 2001. Modulation of contractile activation in skeletal muscle by a calcium-insensitive troponin C mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20245–20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nongthomba, U., M. Cummins, S. Clark, J. O. Vigoreaux, and J. C. Sparrow. 2003. Suppression of muscle hypercontraction by mutations in the myosin heavy chain gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 164:209–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojima, T., N. Koizumi, K. Uyeama, A. Inoue, and K. Nishita. 2000. Functional role of Ca2+-binding site IV of scallop troponin C. J. Biochem. (Tokyo). 128:803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen, C., D. G. Morgan, and D. J. DeRosier. 1996. Image analysis of helical objects: The Brandeis helical package. J. Struct. Biol. 116:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry, D. A. D., and J. M. Squire. 1973. Structural role of tropomyosin in muscle regulation: Analysis of the X-ray patterns from relaxed and contracting muscles. J. Mol. Biol. 75:33–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, G. N., J. P. Fillers, and C. Cohen. 1986. Tropomyosin crystal structure and muscle regulation. J. Mol. Biol. 192:111–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, J. W. S. 1978. Stretch-activation of muscle: function and mechanism. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 201:107–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, F., A. Lakey, B. Agiianian, A. Hutchins, G. W. Butcher, S. Labeit, K. Leonard, and B. Bullard. 2003. Troponin C in different insect muscle types: identification of two isoforms in Lethocerus, Drosophila and Anopheles that are specific to asynchronous flight muscle in the adult insect. Biochem. J. 371:811–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy, M. K., K. C. Holmes, and R. T. Tregear. 1965. Induced changes in orientation of the cross-bridges of glycerinated insect flight muscle. Nature. 207:1276–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, T., B. Bullard, and J. Lepault. 1998. Effects of calcium and nucleotides on the structure of insect flight muscle thin filaments. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 19:353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spudich, J. A., and S. Watt. 1971. The regulation of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction. I. Biochemical studies of the interaction of the tropomyosin-troponin complex with actin and the proteolytic fragments of myosin. J. Biol. Chem. 242:4866–4871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, S., H. Takano-Ohmuro, K. Maruyama, and Y. Hotta. 1990. Regulation of Drosophila myosin ATPase activity by phosphorylation of myosin light chains–I. Wild-type fly. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 95:179–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, S., A. Yamashita, K. Maeda, and Y. Maeda. 2003. Structure of the core domain of human cardiac troponin in the Ca2+-saturated form. Nature. 424:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobacman, L. S. 1996. Thin filament-mediated regulation of cardiac contraction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 58:447–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobacman, L. S., and R. S. Adelstein. 1986. Mechanism of regulation of cardiac actin-myosin subfragment 1 by troponin-tropomyosin. Biochemistry. 25:798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobacman, L. S., D. Lin, C. A. Butters, C. A. Landis, N. Back, D. Pavlov, and E. Homsher. 1999. Functional consequences of troponin T mutations found in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 274:28363–28370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachtenberg, S., and D. J. DeRosier. 1987. Three-dimensional structure of the frozen-hydrated flagellar filament: The left-handed filament of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 195:581–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tregear, R. T., R. J. Edwards, T. C. Irving, K. J. Poole, M. C. Reedy, H. Schmitz, E. Towns-Andrews, and M. K. Reedy. 1998. X-ray diffraction indicates that active cross-bridges bind to actin target zones in insect flight muscle. Biophys. J. 74:1439–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt, T., and K. Leonard. 1999. Structure of the insect troponin complex. J. Mol. Biol. 285:1845–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassylyev, D. G., S. Takeda, S. Wakatsuki, K. Maeda, and Y. Maeda. 1998. Crystal structure of troponin C in complex with troponin I fragment at 2.3-A resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:4847–4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vibert, P., R. Craig, and W. Lehman. 1997. Steric-model for activation of muscle thin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 266:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]