Abstract

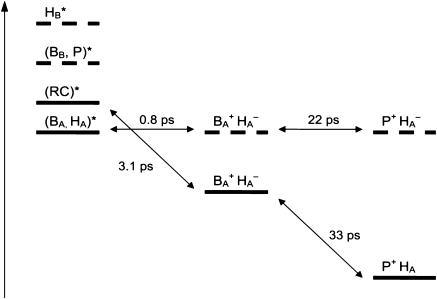

Energy and electron transfer in Photosystem II reaction centers in which the photochemically inactive pheophytin had been replaced by 131-deoxo-131-hydroxy pheophytin were studied by femtosecond transient absorption-difference spectroscopy at 77 K and compared to the dynamics in untreated reaction center preparations. Spectral changes induced by 683-nm excitation were recorded both in the QY and in the QX absorption regions. The data could be described by a biphasic charge separation. In untreated reaction centers the major component had a time constant of 3.1 ps and the minor component 33 ps. After exchange, time constants of 0.8 and 22 ps were observed. The acceleration of the fast phase is attributed in part to the redistribution of electronic transitions of the six central chlorin pigments induced by replacement of the inactive pheophytin. In the modified reaction centers, excitation of the lowest energy QY transition produces an excited state that appears to be localized mainly on the accessory chlorophyll in the active branch (BA in bacterial terms) and partially on the active pheophytin HA. This state equilibrates in 0.8 ps with the radical pair  . BA is proposed to act as the primary electron donor also in untreated reaction centers. The 22-ps (pheophytin-exchanged) or 33-ps (untreated) component may be due to equilibration with the secondary radical pair

. BA is proposed to act as the primary electron donor also in untreated reaction centers. The 22-ps (pheophytin-exchanged) or 33-ps (untreated) component may be due to equilibration with the secondary radical pair  . Its acceleration by HB exchange is attributed to a faster reverse electron transfer from BA to

. Its acceleration by HB exchange is attributed to a faster reverse electron transfer from BA to  . After exchange both

. After exchange both  and

and  are nearly isoenergetic with the excited state.

are nearly isoenergetic with the excited state.

INTRODUCTION

The purification of a functional reaction center (RC) from Photosystem II (PSII) was first reported in 1987 (Nanba and Satoh, 1987) and numerous studies have been dedicated to unraveling its function (reviewed in Dekker and van Grondelle, 2000; Diner and Rappaport, 2002; Greenfield and Wasielewski, 1996; Klug et al., 1998; Prokhorenko and Holzwarth, 2000; Yoder et al., 2002). The structure of the PSII RC is similar to that of the well-known RC of purple bacteria. Current models based on this notion (Svensson et al., 1996) are now essentially confirmed by the first x-ray diffraction studies on crystallized PSII core particles (Zouni et al., 2001; Kamiya and Shen, 2003). The central part of the RC, where the primary charge separation takes place, is an approximately C2-symmetric structure formed by the D1 and D2 polypeptides and six chlorin cofactors: four chlorophyll a (Chl) and two pheophytin a (Pheo). The only major difference from the corresponding arrangement in the purple bacterial RC is the larger spacing of the two central Chls that correspond to the bacterial special pair, resulting in similar (∼10 Å) nearest neighbor distances between all six central cofactors.

Upon excitation, an electron is transferred from the Chls to the Pheo HA, producing the charge-separated state  . Which and how many of the four Chls take part in P680 is subject to debate (Dekker and van Grondelle, 2000; Diner and Rappaport, 2002; Durrant et al., 1995; Stewart et al., 2000; van Gorkom and Schelvis, 1993). The isolated RC does not retain the cofactors involved in normal secondary electron transfer reactions. It does contain cytochrome b559 and two extra Chls, which are too far from the central cofactors (∼25 Å) to be involved in normal electron transfer in the PSII RC. The charge-separated state recombines in the nanosecond timescale (Danielius et al., 1987), either to the triplet state (Takahashi et al., 1987) or to the singlet excited state, with varying, temperature dependent yields (Groot et al., 1994).

. Which and how many of the four Chls take part in P680 is subject to debate (Dekker and van Grondelle, 2000; Diner and Rappaport, 2002; Durrant et al., 1995; Stewart et al., 2000; van Gorkom and Schelvis, 1993). The isolated RC does not retain the cofactors involved in normal secondary electron transfer reactions. It does contain cytochrome b559 and two extra Chls, which are too far from the central cofactors (∼25 Å) to be involved in normal electron transfer in the PSII RC. The charge-separated state recombines in the nanosecond timescale (Danielius et al., 1987), either to the triplet state (Takahashi et al., 1987) or to the singlet excited state, with varying, temperature dependent yields (Groot et al., 1994).

Despite the apparent simplicity of the system a clear understanding of the dynamics of energy transfer and charge separation and of the mechanism of the primary reaction has not yet been attained. Ultrafast time-resolved spectroscopy at low temperatures reveals multiexponential evolution of the excited state and photoproduct populations, even when exciting in the red edge of the absorption spectrum (generally assumed to result in selective excitation of the primary donor). The different time components observed at low temperatures are usually assigned to charge separation either through direct excitation of the primary donor (1–5 ps) (Germano et al., 1995; Greenfield et al., 1999; Groot et al., 1997a; Konermann et al., 1997; Prokhorenko and Holzwarth, 2000; Tang et al., 1990) or slowed down by energy transfer to the primary donor in tens or hundreds of picoseconds (Greenfield et al., 1999; Groot et al., 1997a). However, calculations based on structural information from both the crystallographic structure (Zouni et al., 2001; Kamiya and Shen, 2003) and a model that closely resembles it (Svensson et al., 1996) predict subpicosecond excitation energy equilibration among the six central cofactors (Durrant et al., 1995; Leegwater et al., 1997; Renger and Marcus, 2002). Measurements of fluorescence line narrowing seem to indicate that the lowest energy, emitting state is in fact P680 (Peterman et al., 1998). These observations are inconsistent with the occurrence of charge separation slowed down by energy transfer to P680. Groot et al. (1997a) have attempted to explain their results on the temperature dependence of the rate of charge separation by suggesting that this reaction may be activated, involving an intermediate state higher in energy than P680*, possibly with a charge-transfer (CT) character. Prokhorenko and Holzwarth (2000) proposed that electron transfer occurs in fact from  (the Chl molecule corresponding to the purple bacterial accessory BChl in the active branch) and that the slower components observed in the tens of picoseconds timescale at low temperatures are due to secondary electron transfer from the P Chls to

(the Chl molecule corresponding to the purple bacterial accessory BChl in the active branch) and that the slower components observed in the tens of picoseconds timescale at low temperatures are due to secondary electron transfer from the P Chls to  .

.

One of the causes of controversy and ambiguity is the congestion of the absorption spectrum. At room temperature, the lowest-energy optical transitions (QY) of the eight RC chlorins lie within a 20-nm (400 cm−1) range. Even at a temperature of 6 K the absorption spectrum of the PSII RC shows little structure in the QY region (Fig. 1 A, dotted line). It is now generally agreed that the two distant Chls absorb around 670 nm (Schelvis et al., 1993; Telfer et al., 1990), and probably all six central chromophores contribute to the absorption at 676–684 nm (Durrant et al., 1995; Renger and Marcus, 2002). These spectral assignments are still controversial in some respects (Diner et al., 2001; Germano et al., 2001; Jankowiak et al., 1999; Stewart et al., 2000), but they are in line with calculations based on a multimer model (Durrant et al., 1995; Renger and Marcus, 2002; Barter et al., 2003) that assumes equal site energies and inhomogeneous widths for all pigments. Since the distances, and the assumed nearest-neighbor dipole-dipole interactions, between the central chlorin cofactors are all very similar, calculations of optical spectra yield essentially two wavelength positions for the electronic states in the RC: uncoupled Chls absorb at 670 nm (close to their site energy), and electronically coupled chlorins (the central cofactors) absorb between 680 and 684 nm (Durrant et al., 1995; Renger and Marcus, 2002). In pump-probe measurements little selectivity for each of the central cofactors can be expected, both at the probe and at the pump wavelength. Moreover, similar difficulties are encountered in distinguishing excited states from charge-separated states.

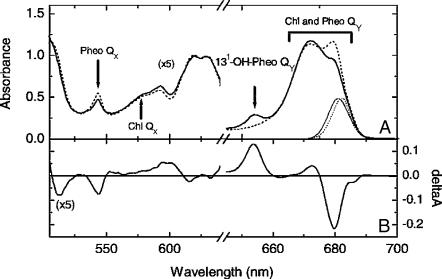

FIGURE 1.

(A) The 6-K absorption spectra of the two types of RCs used for time-resolved absorption difference spectra: untreated RC (dotted) and RC1x (solid). The wavelength profile of the pump laser beam for the measurements was similar to the ones shown here (thin lines) and had a maximum at 683 nm. (B) Absorption-difference spectrum associated with the exchange of HB, calculated from the spectra in A. In both A and B, the signals below 640 nm are shown at 5× enlarged amplitude. (Adapted from Germano et al., 2001.)

We have earlier reported the selective exchange of HA and HB with 131-deoxo-131-hydroxy-pheophytin a (131-OH-Pheo) (Germano et al., 2000, 2001; Shkuropatov et al., 1999). In the RC, the QY transition of this pigment peaks at 654 nm (Fig. 1) and should exhibit much weaker exciton interaction than the native Pheo with the Chls that absorb at 680 nm in the RC. Its reduction potential is estimated to be ∼300 mV more negative than that of Pheo (Shkuropatov et al., 1997), which prevents its photoreduction by P680. A procedure was found that replaces most of HB only when applied once, yielding a preparation called RC1x. The substitution of HB had no effect on charge separation, whereas that of HA blocked it, but both caused similar spectral changes (Germano et al., 2001). Comparison of the absorption spectrum of RC1x to that of an untreated (or control) preparation provides information on the properties of HB in the native RC (Fig. 1 B, adapted from Germano et al., 2001). The QX transitions of both Pheos were at 543 nm. In the QY region, the changes induced by HB replacement were interpreted as the disappearance of the QY transition of HB at 676–680 nm and a blue shift of BB, whereas the P Chls seemed little affected (Germano et al., 2001; Shkuropatov et al., 1999). Thus the absorption near 680 nm in RC1x is mainly due to the cofactors in the active branch: P, HA, and BA.

The observation that HA and HB contribute almost equally to the absorption spectrum, both in the QY and in the QX region, indicates that interpretation of time-resolved absorption-difference spectra is complicated by the spectral evolution in the inactive (B) branch. For example, the dynamics of the pheophytin QX band cannot be assigned unambiguously to HA, since HB contributes equally to that absorption band. In RC1x , however, the cofactors bound at the positions of HA and HB (Pheo and 131-OH-Pheo, respectively) are spectrally distinct, and absorption changes at 543 nm can be assigned exclusively to the Pheo bound at the position of HA, that is, the primary electron acceptor. Here we explore the effect of HB substitution on the femtosecond to picosecond dynamics in the QY and QX regions of the optical spectrum induced by 683-nm excitation at 77 K and probed by transient absorption-difference spectroscopy. A remarkable decrease of the apparent rate constant for charge separation sheds new light on the primary reaction in Photosystem II.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PSII RCs were purified from spinach Tris-washed BBY grana membranes (Berthold et al., 1981) as described by van Leeuwen et al. (1991). RC1x was prepared as in Germano et al. (2000). The total yield of Pheo exchange in RC1x determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of the pigment extract as in Germano et al. (2000) was 41%, corresponding to 82% exchange of HB.

The RC preparations were in a buffer consisting of 20 mM Bis-Tris (pH 6.5), 0.03% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside, 200 mM sucrose, and 67% (w/v) glycerol. The optical density at room temperature at the QY absorption maximum was adjusted to A675 = 1/mm for probing in the QY region and 2/mm for probing in the QX region. Samples were transferred to a 1-mm cuvette and cooled in the dark to 77 K.

Transient absorption data were recorded in a setup described by Gradinaru et al. (2000), modified electronically so that the repetition rate was 100 Hz, low enough to avoid permanent photobleaching of the sample due to accumulation of triplet states. The spectral position and bandwidth (full width at half-maximum) of the pump pulse were set to 683 and 8 nm, respectively, by a narrow-band interference filter. The pulse duration was ∼120 fs. The energy of the pump beam was between 15 and 30 nJ, corresponding to less than one photon absorbed per RC. Time resolved spectral changes were probed with a white light continuum and recorded with a home-built double diode array camera. Transient spectra were collected between 580 and 725 nm and between 460 and 610 nm in time windows of 300 ps (Qy) and 125 ps (QX). The spectral resolution was better than 1 nm.

The time-resolved spectra were globally analyzed with a fitting program described by van Stokkum et al. (1994), which also corrects for group velocity dispersion in the white light continuum. The parameters for this correction were taken from the recorded transient birefringence in CS2. The instrument response function (IRF) was described by a Gaussian with a full width at half-maximum of ∼130 fs (a global analysis fitting parameter).

RESULTS

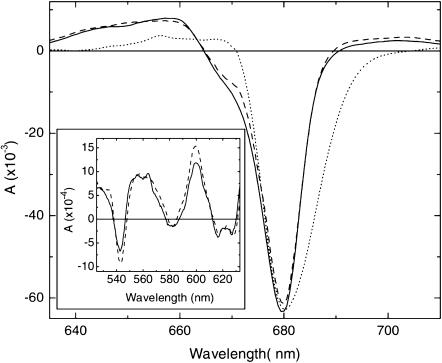

Fig. 2 shows the absorption-difference (ΔA) spectra for the two types of RC preparations at 125 ps after excitation. At this delay, almost all of the energy transfer and charge separation processes are expected to be completed. Therefore, the spectra reflect the differences in absorption between the charge-separated and ground states. These spectra are clearly different from that of Chl excited states (Chl*/Chl), as observed, e.g., in the isolated PSII core antenna protein CP47 (dotted line in Fig. 2; from De Weerd et al., 2002). The much larger width of the ΔA spectrum to the red of the main bleaching is due to the different ground state absorption properties of this complex and to the contribution of stimulated emission (De Weerd et al., 2002) and does not concern us here. The ΔA spectra of the RC preparations show a larger absorption increase at 640–650 nm and a negative shoulder near 668 nm, which are also observed in the difference spectrum of photoaccumulation of Pheo− (see, e.g., Germano et al., 2000). The presence of the latter feature in time-resolved ΔA spectra has been taken as a marker for the formation of the charge-separated state at low temperatures (Groot et al., 1997a; van Kan et al., 1990; Visser et al., 1995). The absorption increase between 630 and 660 nm also reflects the appearance of Pheo− (Fujita et al., 1978; Germano et al., 2000).

FIGURE 2.

Time-resolved ΔA spectra at a time delay of 125 ps measured in untreated RC (dashed) and RC1x (solid). The dotted line represents the ΔA spectrum of Chl*/Chl in a protein environment (CP47) (from de Weerd et al., 2002; courtesy of F. de Weerd), with a shifted wavelength scale (−6 nm) so that its maximal bleaching coincides with that of the RCs. The inset compares the ΔA spectra of untreated RC (dashed) and RC1x (solid) at a delay of 125 ps in the Pheo and Chl QX region.

The Pheo QX bleaching is at 543 nm for both types of RCs, the same wavelength as the maximum of the ground state absorption (Fig. 2, inset). The broad band centered at 580 nm represents bleaching of the Chl QX band (Kwa et al., 1994). The split band at 616 and 628 nm represents bleaching of Pheo as well as Chl absorption bands (cf. Fig. 1 A). Pheo absorption is more pronounced at 616 nm, since this band is decreased upon exchange of Pheo with 131-OH-Pheo (Fig. 1; see also Germano et al., 2000).

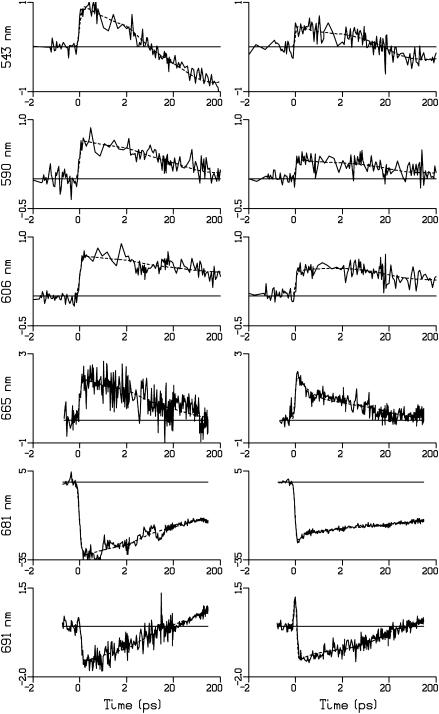

Fig. 3 shows kinetic traces at selected wavelengths in the QX and QY regions for untreated RC (left) and RC1x (right). The timescale is linear between −2 and 2 ps and logarithmic for later delay times. Six hundred sixty-five and 691 nm are close to the isosbestic points of the ΔA spectra presented in Fig. 2, so the decay of these transients reflects the kinetics of charge separation (see above). The results confirm that the charge separation is preceded by a transient absorption increase at 665 nm (due to excited state absorption) and an apparent decrease at 691 nm (due to stimulated emission).

FIGURE 3.

Kinetic traces (solid) and fits to the data (dashed) for untreated RC (left) and RC1x (right) at representative wavelengths in the QX and QY regions. Unit of ΔA is mOD. The timescale is linear between −2 and 2 ps and logarithmic for later delays.

The positive signal near time 0 in the kinetic traces at 691 nm is related to a spectral broadening of the initial bleaching during temporal overlap of pump and probe beams. This feature was only present at probe wavelengths close to the maximum of the QY bleaching and not in the QX region. Its dynamics are adequately described by the IRF (Groot et al., 1997a,b), and the spectral shape (thin solid lines straddling 680 nm in Fig. 4 A) agrees well with the inset in Fig. 1 of Groot et al. (1997a). This broadening phenomenon will not be further discussed here.

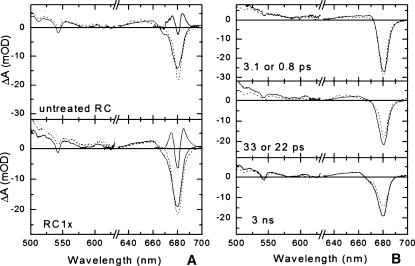

FIGURE 4.

Species-associated difference spectra estimated from global analysis of the data for untreated RC and RC1x. Data for the QY and QX regions were scaled to each other in the wavelength range where they overlap. The spectra in the QX region are amplified 10× for easier viewing. (A) SADS of untreated RC (top) and RC1x (bottom). Species that decay with a time constant of 3.1 ps (untreated RC) or 0.8 ps (RC1x) (dotted lines), 33 ps (untreated RC) or 22 ps (RC1x) (dashed lines), and 3 ns (solid lines). The thin solid line straddling 680 nm represents the SADS of a component with dynamics described by the IRF (see text). (B) Comparison of the SADS of untreated RC (dashed) and RC1x (solid).

Although the signal/noise ratio for kinetic traces at individual wavelengths is limited, a kinetic difference between modified and untreated RCs is consistently observed. The transients decay significantly faster in the modified RCs, especially in the sub-ps time range where the data for untreated RCs do not exhibit significant decay. In Fig. 3 this unexpected kinetic difference is most clearly observed at 665 and 681 nm.

Since the QY and QX data for untreated RC and RC1x overlap between 580 and 610 nm (see Materials and Methods), they could be linked and analyzed simultaneously, assuming wavelength-independent kinetics. A minimal number of three components, with time constants of ∼0.8 or 3.1 ps (τ1), 22 or 33 ps (τ2), and a long-lived component (τ3, which was arbitrarily fixed at 3 ns), was needed for an adequate description of the time-resolved data for each type of RC (Table 1). The difference in time constants for the two types of RCs could not be ignored in the fits and indicates that the first picosecond process is accelerated approximately fourfold and the second ∼1.5-fold after the HB substitution.

TABLE 1.

Best-fitting time constants obtained by global analysis of the data sets measured for untreated RC and RC1x

| Type of RC | τ1 | τ2 |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 3.1 ± 0.5 ps | 33 ± 5 ps |

| RC1x | 0.8 ± 0.2 ps | 22 ± 5 ps |

The spectral evolution over the whole wavelength range can be visualized by constructing species-associated difference spectra (SADS), assuming a sequential, irreversible model A → B → C… , where the arrows symbolize increasingly slower monoexponential processes, with time constants that can be regarded as the lifetimes of species A (τ1), B(τ2), etc. The SADS of a species with lifetime τ is the difference between the absorption spectrum of the flash-induced species present before time τ and the absorption spectrum of the ground state present before the flash. We note that species A, B, etc., do not necessarily represent pure states and the processes may be equilibrations, so that their observed rate constants are the sum of forward and back rate constants between the pure states equilibrating. The results of this analysis are shown in Fig. 4 A for untreated RC (top) and RC1x (bottom). In Fig. 4 B each of the SADS for untreated RC (dashed) and RC1x (solid) are plotted together.

The dotted lines in Fig. 4 A (and both spectra in the top panel in Fig. 4 B) represent the initial absorption change, determined from the data after correction for group-velocity dispersion and deconvolution with the IRF. In the QY region, they resemble the difference spectrum of Chl*/Chl in CP47 (see Fig. 2 and De Weerd et al., 2002) and are characterized by ground state bleaching/stimulated emission at 679.5 nm (untreated RC) and 680.5 nm (RC1x) and a small, broad, positive signal between 650 and 670 nm due to Chl (and Pheo) excited state absorption. The small red shift of the bleaching/stimulated emission in RC1x versus the untreated RC will prove significant for interpreting the kinetic differences between the two types of RCs (see below). Between 500 and 640 nm, ground state bleaching of the Pheo and Chl QX transitions is observed for both types of RCs, superimposed on a broad, positive signal of small amplitude that arises from excited state absorption of the chlorins.

The decay from the initial state (Fig. 4 A, dotted lines) to the intermediate state (Fig. 4 A, dashed lines) is associated with a 40% decrease of the main QY bleaching in untreated RC, but only 20% in RC1x. The spectral evolution over the whole region (the bleaching of the Pheo QX band, the decrease of QY bleaching caused by the disappearance of stimulated emission, the appearance of the negative shoulder near 670 nm, and the positive absorption at wavelengths longer than 690 nm) can be assigned to the formation of the radical pair state with a 3.1-ps time constant in the untreated RC and 0.8 ps in the modified RC.

The above-mentioned spectral differences between the initial and intermediate states are slightly less pronounced in RC1x. The spectral differences between the intermediate and final states (Fig. 4 A, solid lines), however, resemble those between the initial and intermediate states, and in this case the differences are more pronounced in RC1x. This means that a larger part of the charge separation in the modified RC is associated with the decay of the second component, with a 22-ps lifetime, whereas in untreated RC the fast kinetic component (3.1 ps) produces most of the charge-separated states (Fig. 4 A).

DISCUSSION

The results presented here describe the dynamics of energy conversion in PSII RCs in which the properties of some of the central chlorin cofactors had been substantially modified. The main consequence of HB replacement with 131-OH-Pheo is the decrease of the observed time constants from 3.1 to 0.8 ps and from 33 to 22 ps together with a decrease of the yield of radical pair formation associated with the fast phase and an increase of the yield during the slow phase.

The 0.8- vs. 3.1-ps component

Comparison of the SADS of the initial and intermediate states indicates that the fast phase represents charge separation. The absorbance changes associated with the fast phase are accompanied by a decay of excited states (observed, e.g., at 691 nm and, superimposed on some recovery of ground state absorption, at 681 nm) and an ingrowth of a bleaching at 668 nm that is characteristic for the presence of the charge-separated state. The concomitant increase of Pheo QX bleaching at 543 nm may therefore also be attributed to charge separation.

A time constant for charge separation of 3.1 ps is slightly shorter than the one measured by Greenfield et al. (1999), which was obtained at 7 K under similar excitation conditions and with detection in the Pheo QX region. However, there is a large variation in the initial rates of charge separation reported in the literature on pump-probe absorption-difference spectroscopy at low temperatures. Time constants have been reported of 2 ps for excitation at 685 nm at 95 K (Germano et al., 1995), 5 ps for excitation at 683 nm at 7 K and detection in the QX (Greenfield et al., 1999), 1.5 ps for excitation at 688 nm at 77 K (Visser et al., 1995), and 0.7 ps for excitation at 685 nm at 77 K (Groot et al., 1997a), and thus seem to depend on the wavelengths of excitation and detection and on temperature.

Picosecond dynamics measured in the QY absorption region with excitation within this band, as described by several authors (Germano et al., 1995; Groot et al., 1997a; Visser et al., 1995), are generally distorted by spectral broadening (Groot et al., 1997b) (see above). This is usually described by the IRF. If this contribution to the data is not estimated correctly, fits of the kinetics may easily overestimate the initial rate of charge separation. The problem is avoided by excitation in the QY and detection in the QX region, as in the experiments of Greenfield et al. (1999). This may explain why our kinetic analysis agrees relatively well with that in Greenfield et al. (1999) but not entirely with conclusions obtained from measurements in the QY absorption region only (Groot et al., 1997a). However, other variations in the experimental conditions and in the purity and integrity of the RC complex may also contribute to the discrepancies in the results reported in the literature.

The kinetic analysis and the interpretation of the spectral changes indicate that the fast phase of 0.8 ps observed in RC1x can also be assigned to charge separation. Compared to the 3.1-ps component in untreated RC, it represents a significant net acceleration and could not be explained by an increased inhomogeneity. We could fit the data for untreated RC with an additional 0.8-ps component, but that did not significantly improve the χ2-value of the fits, and the spectrum (SADS) obtained did not differ very much from that of the 3.1-ps component resulting from analysis with only three components. It was not possible to fit the data sets for untreated and RC1x simultaneously with the same time constants, confirming the kinetic differences observed by their independent global analysis (Table 1).

The 22- vs. 33-ps component

In the QY region the second kinetic component, decaying with a time constant of 22 ps in the modified RCs and 33 ps in untreated RC, is associated with a blue shift of the main bleaching/stimulated emission (Fig. 4 A, upper panel). This shift is partially caused by loss of stimulated emission at wavelengths above 680 nm, especially in RC1x (see, e.g., Fig. 4 A), and can be assigned to a further decrease of the excited states population. However, the spectral evolution in the QX region indicates that in RC1x additional charge separation occurs with a time constant of 22 ps, and that in untreated RC the Pheo QX bleaching amplitude also increases with a time constant of 33 ps. Thus, the intermediate component must also be assigned to charge separation.

Kinetic components in the tens of picoseconds range observed at low temperatures have been assigned to charge separation limited by slow (uphill) energy transfer (Germano et al., 1995; Greenfield et al., 1999; Groot et al., 1997a). However, the observation of such slow components at very low temperatures, e.g., 7 K (Greenfield et al., 1999) or 1.4 K (Prokhorenko and Holzwarth, 2000), is difficult to understand in terms of a detrapping mechanism, unless the energies of the states involved in uphill energy transfer differ by less than 1 nm (at 7 K) (Greenfield et al., 1999). The multiphasic kinetics of radical pair formation can better be explained by assuming multiple radical pair states, as suggested by several models (Klug et al., 1998; Konermann et al., 1997; Prokhorenko and Holzwarth, 2000). In this interpretation, the 22-/33-ps component in our data may be assigned to stabilization of the initial charge separation, e.g., by secondary electron transfer. This interpretation is based mainly on the spectral changes associated with the 33-ps component in untreated RCs, which especially in the QX region do not indicate a further decay of excited states, in contrast to the 22-ps component in RC1x (Fig. 4 A, top; see also above). The time constants of 22/33 ps are consistent with those proposed in the literature for the first step of radical pair stabilization (Klug et al., 1998; Prokhorenko and Holzwarth, 2000).

Excited state distribution

The acceleration of the initial rate of charge separation upon exchange of HB is surprising, since this cofactor is bound at the inactive branch of the RC and is not close to a redox-active cofactor (Kamiya and Shen, 2003; Zouni et al., 2001). However, our previous analysis of the steady-state optical spectra of RC1x (Germano et al., 2001) has revealed that HB-exchange results in blue shifts of transitions at 680 and 684 nm (see also Fig. 1 B) and in pronounced changes in the CD spectrum, which indicate that HB takes part in excitonic interactions with the remaining RC central cofactors. Furthermore, photoaccumulation of P680+ in Pheo-modified RCs has shown that the absorption of the primary donor is blue shifted by ∼2 nm, and has a larger contribution at 670 nm in RCs where HB had been chemically modified (Shkuropatov et al., 1997). The blue-shifted (to ∼674 nm) state that results from HB exchange may replace an exciton state that was delocalized over the P Chls, in addition to BB, in untreated RC (Germano et al., 2001).

The steady-state spectral changes imply that the distribution of excited states produced by the 683-nm pump pulse in untreated RC is different from that in RC1x for the same excitation conditions and is mainly localized in the active branch. The blue shift of the HB transition (from 676–680 to 654 nm; Germano et al., 2001) and of the 680-nm transition of at least one of the other central Chls (most likely BB) imply that in RC1x at most four and perhaps even only two cofactors contribute to the 680-nm pigment pool, whereas there are six in untreated RCs. The decrease in the extent of the delocalization of the excited state could in part explain the four times faster rate of charge separation in RC1x.

Our results indicate that the excited state in untreated RC and in RC1x is either delocalized or distributed over Pheo and Chl cofactors, since the 0.8- or 3.1-ps SADS show bleaching of QX transitions of both types of cofactors (Fig. 4). Considering the analysis of the steady-state optical spectra (Germano et al., 2001) (see above), it seems reasonable to assume that the Chl cofactor excited at 682 nm in RC1x is BA and that the initial excited state is partially delocalized (or distributed) over HA as well. However, the exciton in the alleged (BAHA)* state must be more localized on BA, since the Pheo QX bleaching in the initial SADS of RC1x shows only a minor contribution of HA to the absorption spectrum.

The excited state (BAHA)* is slightly lower in energy than the excited state(s) produced by 683-nm excitation in untreated RCs, since the 0.8-ps SADS of RC1x is 1-nm red shifted compared to the 3.1-ps SADS of untreated RC (Fig. 4). This observation may explain the apparent discrepancy between our results and those of Groot et al. (1997a), who found fast time constants of 0.4–0.7 ps at all temperatures above 20 K, upon 685-nm excitation. These time constants are close to the 0.8-ps value we observe in RC1x. A possible interpretation of this similarity is that the 2-nm longer excitation wavelength in the experiments by Groot et al. (1997a) preferentially selects for transitions in the active branch.

Charge transfer

Presumably, the first radical pair formed from (BAHA)* is  , since these are adjacent cofactors and HA is the primary electron acceptor. Charge separation upon direct excitation of BA with a time constant of 0.2 ps was first observed by van Brederode et al. (1997, 1999a,b) in RCs of purple bacteria. In untreated PSII RCs, however, selective excitation of BA is difficult, since this cofactor is either excitonically coupled to the remaining central chlorins (Durrant et al., 1995; Leegwater et al., 1997; Renger and Marcus, 2002) or nearly isoenergetic with other electronic states in the RC, in particular those on the inactive branch. Exchange of HB for 131-OH-Pheo disturbs the excitonic interactions and allows for direct excitation of a state located in the active branch only. Our interpretation of the results is in line with suggestions by several authors (Dekker and van Grondelle, 2000; Diner and Rappaport, 2002; Prokhorenko and Holzwarth, 2000) that the primary electron donor in PSII is BA. Barter et al. (2003) recently calculated the electron transfer dynamics predicted by the multimer model (Durrant et al., 1995) and concluded that at least 90% of the charge separation proceeds via the state

, since these are adjacent cofactors and HA is the primary electron acceptor. Charge separation upon direct excitation of BA with a time constant of 0.2 ps was first observed by van Brederode et al. (1997, 1999a,b) in RCs of purple bacteria. In untreated PSII RCs, however, selective excitation of BA is difficult, since this cofactor is either excitonically coupled to the remaining central chlorins (Durrant et al., 1995; Leegwater et al., 1997; Renger and Marcus, 2002) or nearly isoenergetic with other electronic states in the RC, in particular those on the inactive branch. Exchange of HB for 131-OH-Pheo disturbs the excitonic interactions and allows for direct excitation of a state located in the active branch only. Our interpretation of the results is in line with suggestions by several authors (Dekker and van Grondelle, 2000; Diner and Rappaport, 2002; Prokhorenko and Holzwarth, 2000) that the primary electron donor in PSII is BA. Barter et al. (2003) recently calculated the electron transfer dynamics predicted by the multimer model (Durrant et al., 1995) and concluded that at least 90% of the charge separation proceeds via the state  .

.

The state (BAHA)* is in this interpretation delocalized over the primary electron donor and the primary electron acceptor, so that it is reasonable to assume that it has a considerable CT character. Recent results of Stark spectroscopy on untreated RCs and RC1x have provided evidence for participation of HA and possibly BA in a CT state (Frese et al., 2003). Our results for RC1x may be interpreted in terms of formation of the CT state ( ) in equilibrium with the excited state (BAHA)* with a time constant of 0.8 ps. These two states are nearly isoenergetic. In untreated RC, the CT state (or initial radical pair) is formed in equilibrium with the excited state RC*, which is slightly higher (1–2 nm) in energy, with a 3.1-ps time constant (Fig. 5). We note that the existence in the PSII RC of a CT state lower in energy than the excited state was proposed by Kwa et al. (1994) to explain results of site-selection triplet-minus-singlet spectroscopy upon excitation in the red edge of the QY absorption band. The involvement of a CT state in the mechanism of primary charge separation in PSII was also postulated by Groot et al. (1997a). Furthermore, CT states have been observed by Stark spectroscopy of the absorption band of the accessory BChls in RCs of purple bacteria (Zhou and Boxer, 1998). The observed resonance Stark effect was assigned to mixing of the excited state of BA with

) in equilibrium with the excited state (BAHA)* with a time constant of 0.8 ps. These two states are nearly isoenergetic. In untreated RC, the CT state (or initial radical pair) is formed in equilibrium with the excited state RC*, which is slightly higher (1–2 nm) in energy, with a 3.1-ps time constant (Fig. 5). We note that the existence in the PSII RC of a CT state lower in energy than the excited state was proposed by Kwa et al. (1994) to explain results of site-selection triplet-minus-singlet spectroscopy upon excitation in the red edge of the QY absorption band. The involvement of a CT state in the mechanism of primary charge separation in PSII was also postulated by Groot et al. (1997a). Furthermore, CT states have been observed by Stark spectroscopy of the absorption band of the accessory BChls in RCs of purple bacteria (Zhou and Boxer, 1998). The observed resonance Stark effect was assigned to mixing of the excited state of BA with  CT states. Given the structural analogy between RCs of purple bacteria and PSII, a similar effect can be expected in the latter. Interestingly,

CT states. Given the structural analogy between RCs of purple bacteria and PSII, a similar effect can be expected in the latter. Interestingly,  states are not observed (Zhou and Boxer, 1998; Frese et al., 2003). This asymmetry may contribute to the unidirectionality of electron transfer in PSII-type RCs.

states are not observed (Zhou and Boxer, 1998; Frese et al., 2003). This asymmetry may contribute to the unidirectionality of electron transfer in PSII-type RCs.

FIGURE 5.

Energy-level diagram summarizing the interpretation of the picosecond dynamics in untreated and modified RCs. The dashed levels correspond to the blue-shifted transitions in RC1x. The positions of the levels are not at scale.

Stabilization

Our results and those of others (Germano et al., 1995; Greenfield et al., 1999; Groot et al., 1997a; Klug et al., 1998; Konermann et al., 1997; Prokhorenko and Holzwarth, 2000; Visser et al., 1995) indicate that the initially formed radical pair is stabilized in the tens of picoseconds time range. We interpret this stabilization in terms of a slowly relaxing equilibrium between the radical pair state and the excited state, in agreement with results from time-resolved fluorescence both at room temperature and at 77 K, which show that a significant fraction of the initial excited states remains untrapped for tens to hundreds of picoseconds (Donovan et al., 1997; Konermann et al., 1997). The presence of excited states in the tens of picoseconds timescale can be related to the zero-crossing time at the Pheo QX bleaching: ∼10 ps for untreated RC but longer (near 20 ps) for RC1x (at 543 nm; see Fig. 3). The absorption change in this wavelength region is composed of a broad and featureless positive signal due to Chl excited state absorption and a negative signal due to Pheo QX bleaching. The later zero-crossing time for RC1x and the slower decay of stimulated emission at 691 nm indicate a larger excited states population at times up to 100 ps in this preparation as compared to untreated RC. Also the ratio between the Pheo QX bleaching at 543 nm and the QY bleaching around 680 nm can be used as a measure of the charge separation yield. It is then clear from Fig. 4 B (3-ns component) that the yield of charge separation in the time range measured is lower in modified RCs than in untreated RCs.

We note that the long-lived excited state population observed at room temperature or at 77 K cannot be assigned to the postulated low-temperature trap state, since this state is only observed near 4 K (Groot et al., 1994). The observation of a lower yield of radical pair formation at 100 ps in RC1x versus untreated RC is consistent with the interpretation of the observed rate constants in terms of excited state/radical pair equilibration processes (Donovan et al., 1997; Klug et al., 1998; Konermann et al., 1997). We further suggest that radical pair stabilization involves the transfer of an electron from PA to  (since PA is the cofactor nearest to BA (Kamiya and Shen, 2003; Zouni et al., 2001).

(since PA is the cofactor nearest to BA (Kamiya and Shen, 2003; Zouni et al., 2001).

Assuming exponential forward and reverse kinetics, the observed rate constant of equilibration is the sum of the forward and reverse rate constants. The equilibrium constant associated with the 0.8 ps phase in RC1x appears to be somewhat less than 1 so the time constant of charge separation is probably 1–2 ps. The equilibrium constant associated with the 3.1-ps component in untreated RCs is substantially larger, so part of the observed acceleration of the fast phase of charge separation by HB exchange could well be due to an acceleration of charge recombination. At 77 K the Boltzmann factor kBT is less than 7 meV and a 2-nm red shift of the excited state in RC1x relative to that in untreated RC could explain a twofold acceleration of a thermally activated charge recombination, if the energy of the radical pair is the same. Suppose the forward reaction is threefold accelerated because the excited state is concentrated on fewer pigments in RC1x, however, some increase of the energy of the radical pair would be required in addition to explain the decreased equilibrium constant. The accelerated stabilization of the charge separation in RC1x may similarly be attributed to an acceleration of the reverse reaction, whereas the forward reaction should actually be slowed down by the lower population of the initial radical pair in equilibrium with the excited state. In this interpretation, both phases of charge separation should be exothermic by at least 10–15 meV in untreated RC, whereas in RC1x the final state would still be close to isoenergetic with the excited state, explaining its lower yield.

CONCLUSIONS

The combination of femtosecond pump-probe transient absorption experiments with selective Pheo exchange described here has resulted in new insights in the details of the charge separation mechanism in Photosystem II.

The results show that the radical pair P680+Pheo− is formed from the lowest excited state mainly in two phases with time constants of 3.1 and 33 ps in untreated RCs. Substitution of 131-OH-Pheo for HB accelerates both phases of charge separation, to 0.8 and 22 ps, respectively. It also decreases the yield of both phases, indicating that the observed increase of equilibration rates is at least partially due to acceleration of the reverse reaction(s). After HB exchange both the state formed by the fast phase and that formed by the slow phase appear to be virtually isoenergetic with the initial excited state, thus accounting for an approximately twofold decrease of the observed time constants. The fact that the fast phase is accelerated more is attributed to localization of the lowest excited state in RC1x on the pigments involved in the primary charge transfer, BA and HA, allowing a very fast equilibrium between the excited state (BAHA)* and a charge-separated state  . Since the slow phase of charge separation is not correspondingly accelerated, it is attributed to a secondary process stabilizing the charge separation, presumably by electron transfer from PA to

. Since the slow phase of charge separation is not correspondingly accelerated, it is attributed to a secondary process stabilizing the charge separation, presumably by electron transfer from PA to  .

.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. G. Zvereva and V. A. Shkuropatova for their help in preparing the chemically modified pheophytin.

This work was supported by grant 047-006-003 from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), a PCB RAS grant from the Russian Academy of Sciences, grant 00-04-48334 from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, and grant PRAXIS XXI/BD/2870/94 from the Portuguese National Foundation for Scientific and Technical Research (JNICT).

M. Germano and C. C. Gradinaru contributed equally to this work.

References

- Barter, L. M. C., J. R. Durrant, and D. R. Klug. 2003. A quantitative structure-function relationship for the Photosystem II reaction center: supramolecular behavior in natural photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:946–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthold, D. A., G. T. Babcock, and C. F. Yocum. 1981. A highly resolved, oxygen-evolving Photosystem II preparation from spinach thylakoid membranes. FEBS Lett. 134:231–234. [Google Scholar]

- Danielius, R. V., K. Satoh, P. J. M. van Kan, J. J. Plijter, A. M. Nuijs, and H. J. van Gorkom. 1987. The primary reaction of Photosystem II in the D1–D2-cytochrome b-559 complex. FEBS Lett. 213:241–244. [Google Scholar]

- De Weerd, F. L., I. H. M. van Stokkum, H. van Amerongen, J. P. Dekker, and R. van Grondelle. 2002. Pathways for energy transfer in the core light-harversting complexes CP43 and CP47 of photosystem II. Biophys. J. 82:1586–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, J. P., and R. van Grondelle. 2000. Primary charge separation in Photosystem II. Photosynth. Res. 63:195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diner, B. A., and F. Rappaport. 2002. Structure, dynamics, and energetics of the primary photochemistry of photosystem II of oxygenic photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53:551–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diner, B. A., E. Schlodder, P. J. Nixon, W. J. Coleman, F. Rappaport, J. Lavergne, W. F. J. Vermaas, and D. A. Chisholm. 2001. Site-directed mutations at D1-His198 and D2-His197 of photosystem II in Synechocystis PCC6803: sites of primary charge separation and cation and triplet stabilization. Biochemistry. 40:9265–9281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, B., L. A. Walker II, D. Kaplan, M. Bouvier, C. F. Yocum, and R. J. Sension. 1997. Structure and function of the isolated reaction center complex of photosystem II. 1. Ultrafast fluorescence measurements of PSII. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101:5232–5238. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant, J. R., D. R. Klug, S. L. S. Kwa, R. van Grondelle, G. Porter, and J. P. Dekker. 1995. A multimer model for P680, the primary electron donor of Photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:4798–4802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frese, R. N., M. Germano, F. L. de Weerd, I. H. M. van Stokkum, A. Y. Shkuropatov, V. A. Shuvalov, H. J. van Gorkom, R. van Grondelle, and J. P. Dekker. 2003. Electric field effects on the chlorophylls, pheophytins and β-carotenes in the reaction center of photosystem II. Biochemistry. 42:9205–9213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, I., M. S. Davis, and J. Fajer. 1978. Anion radicals of pheophytin and chlorophyll a: their role in the primary charge separations of plant photosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100:6280–6282. [Google Scholar]

- Germano, M., A. Y. Shkuropatov, H. Permentier, R. de Wijn, A. J. Hoff, V. A. Shuvalov, and H. J. van Gorkom. 2001. Pigment organization and their interactions in reaction centers of photosystem II: optical spectroscopy at 6 K of reaction centers with modified pheophytin composition. Biochemistry. 40:11472–11482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germano, M., A. Y. Shkuropatov, H. Permentier, R. A. Khatypov, V. A. Shuvalov, A. J. Hoff, and H. J. van Gorkom. 2000. Selective replacement of the active and inactive pheophytin in reaction centres of Photosystem II by 131-deoxo-131-hydroxy-pheophytin a and comparison of their 6 K absorption spectra. Photosynth. Res. 64:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germano, M., M. H. Vos, J. L. Martin, T. J. Aartsma, and H. J. van Gorkom. 1995. Femtosecond absorbance changes in PS II reaction centers. In Photosynthesis: From Light to Biosphere, Vol. 1. P. Mathis, editor. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 503–506.

- Gradinaru, C. C., I. H. M. van Stokkum, A. Pascal, R. van Grondelle, and H. van Amerongen. 2000. Identifying the pathways of energy transfer between carotenoids and chlorophylls in LHCII and CP29. A multicolor, femtosecond pump-probe study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 104:9330–9342. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, S. R., M. Seibert, and M. R. Wasielewski. 1999. Time-resolved absorption changes of the pheophytin Qx band in isolated photosystem II reaction centers at 7K: energy transfer and charge separation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 103:8364–8374. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, S. R., and M. R. Wasielewski. 1996. Excitation energy transfer and charge separation in the isolated Photosystem II reaction center. Photosynth. Res. 48:83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groot, M.-L., E. J. G. Peterman, P. J. M. van Kan, I. H. M. van Stokkum, J. P. Dekker, and R. van Grondelle. 1994. Temperature-dependent triplet and fluorescence quantum yields of the photosystem II reaction center described in a thermodynamic model. Biophys. J. 67:318–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groot, M.-L., F. van Mourik, C. Eijckelhoff, I. H. M. van Stokkum, J. P. Dekker, and R. van Grondelle. 1997a. Charge separation in the reaction center of photosystem II studied as a function of temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:4389–4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groot, M.-L., R. van Grondelle, J. A. Leegwater, and F. van Mourik. 1997b. Radical pair quantum yield of Photosystem II of green plants and of the bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Saturation behavior with sub-picosecond pulses. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101:7869–7873. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowiak, R., M. Ratsep, R. Picorel, M. Seibert, and G. J. Small. 1999. Excited states of the 5-chlorophyll photosystem II reaction center. J. Phys. Chem. B. 103:9759–9769. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya, R., and J.-R. Shen. 2003. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus vulcanus at 3.7 Å resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:98–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug, D. R., J. R. Durrant, and J. Barber. 1998. The entanglement of excitation energy transfer and electron transfer in the reaction centre of photosystem II. Philos. T. Roy. Soc. A. 356:449–464. [Google Scholar]

- Konermann, L., G. Gatzen, and A. R. Holzwarth. 1997. Primary processes and structure of the photosystem II reaction center. 5. Modeling of the fluorescence kinetics of the D1-D2-cyt-b559 complex at 77K. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101:2933–2944. [Google Scholar]

- Kwa, S. L. S., C. Eijckelhoff, R. van Grondelle, and J. P. Dekker. 1994. Site-selection spectroscopy of the reaction center complex of Photosystem II. 1. Triplet-minus-singlet absorption difference: a search for a second exciton band of P-680. J. Phys. Chem. 98:7702–7711. [Google Scholar]

- Kwa, S. L. S., W. R. Newell, R. van Grondelle, and J. P. Dekker. 1992. The reaction center of Photosystem II studied with polarized fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1099:193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kwa, S. L. S., S. Völker, N. T. Tilly, R. van Grondelle, and J. P. Dekker. 1994. Polarized site-selection spectroscopy of chlorophyll a in detergent. Photochem. Photobiol. 59:219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Leegwater, J. A., J. R. Durrant, and D. R. Klug. 1997. Exciton equilibration induced by phonons: theory and application to PS II reaction centers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101:7205–7210. [Google Scholar]

- Nanba, O., and K. Satoh. 1987. Isolation of a Photosystem II reaction center consisting of D1 and D2 polypeptides and cytochrome b-559. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:109–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman, E. J. G., H. van Amerongen, R. van Grondelle, and J. P. Dekker. 1998. The nature of the excited state of the reaction center of photosystem II of green plants: a high-resolution fluorescence spectroscopy study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:6128–6133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorenko, V. I., and A. R. Holzwarth. 2000. Primary processes and structure of the photosystem II reaction center: a photon echo study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 104:11563–11578. [Google Scholar]

- Renger, T., and R. A. Marcus. 2002. Photophysical properties of PS-2 reaction centers and a discrepancy in exciton relaxation times. J. Phys. Chem. B. 106:1809–1819. [Google Scholar]

- Schelvis, J. P. M., P. I. van Noort, T. J. Aartsma, and H. J. van Gorkom. 1993. Energy transfer, charge separation and pigment arrangement in the reaction center of Photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1184:242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Shkuropatov, A. Y., R. A. Khatypov, V. A. Shkuropatova, M. G. Zvereva, T. G. Owens, and V. A. Shuvalov. 1999. Reaction centers of Photosystem II with a chemically-modified pigment composition: exchange of pheophytins with 13(1)-deoxo-13(1)-hydroxy-pheophytin a. FEBS Lett. 450:163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkuropatov, A. Y., R. A. Khatypov, T. S. Volshchukova, V. A. Shkuropatova, T. G. Owens, and V. A. Shuvalov. 1997. Spectral and photochemical properties of borohydride-treated D1–D2-cytochrome b-559 complex of photosystem II. FEBS Lett. 420:171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, D. H., P. J. Nixon, B. A. Diner, and G. W. Brudvig. 2000. Assignment of the Qy absorbance bands of photosystem II chromophores by low-temperature optical spectroscopy of wild-type and mutant reaction centers. Biochemistry. 39:14583–14594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, B., C. Etchebest, P. Tuffery, P. J. M. van Kan, J. Smith, and S. Styring. 1996. A model for the photosystem II reaction center core including the structure of the primary donor P680. Biochemistry. 35:14486–14502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Y., Ö. Hansson, P. Mathis, and K. Satoh. 1987. Primary radical pair in the Photosystem II reaction center. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 893:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, D., R. Jankowiak, M. Seibert, C. F. Yocum, and G. J. Small. 1990. Excited-state structure and energy-transfer dynamics of two different preparations of the reaction center of photosystem II: a hole-burning study. J. Phys. Chem. 94:6519–6522. [Google Scholar]

- Telfer, A., W.-Z. He, and J. Barber. 1990. Spectral resolution of more than one chlorophyll electron donor in the isolated Photosystem II reaction center complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1017:143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Van Brederode, M. E., M. R. Jones, F. van Mourik, I. H. M. van Stokkum, and R. van Grondelle. 1997. A new pathway for transmembrane electron transfer in photosynthetic reaction centers of Rhodobacter sphaeroides not involving the excited state special pair. Biochemistry. 36:6855–6861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brederode, M. E., and R. van Grondelle. 1999. New and unexpected routes for ultrafast electron transfer in photosynthetic reaction centers. FEBS Lett. 455:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brederode, M. E., F. van Mourik, I. H. M. van Stokkum, M. R. Jones, and R. van Grondelle. 1999. Multiple pathways for ultrafast transduction of light energy in the photosynthetic reaction center of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:2054–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gorkom, H. J., and J. P. M. Schelvis. 1993. Kok's oxygen clock: what makes it tick? The structure of P680 and consequences of its oxidizing power. Photosynth. Res. 38:297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kan, P. J. M., S. C. M. Otte, F. A. M. Kleinherenbrink, M. C. Nieveen, T. J. Aartsma, and H. J. van Gorkom. 1990. Time-resolved spectroscopy at 10 K of the Photosystem II reaction center: deconvolution of the red absorption band. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1020:146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, P. J., M. C. Nieveen, E. J. van de Meent, J. P. Dekker, and H. J. van Gorkom. 1991. Rapid and simple isolation of pure Photosystem II core and reaction center particles from spinach. Photosynth. Res. 28:149–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Stokkum, I. H. M., T. Scherer, A. M. Brouwer, and J. W. Verhoeven. 1994. Conformational dynamics of flexibly and semirigidly bridged electron donor-acceptor systems as revealed by spectrotemporal parametrization of fluorescence. J. Phys. Chem. 98:852–866. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, H. M., M. L. Groot, F. van Mourik, I. H. M. van Stokkum, J. P. Dekker, and R. van Grondelle. 1995. Subpicosecond transient absorption difference spectroscopy in the reaction center of Photosystem II–radical pair formation at 77 K. J. Phys. Chem. 99:15304–15309. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder, L. M., A. G. Cole, and R. J. Sension. 2002. Structure and function in the isolated reaction center complex of Photosystem II: energy and charge transfer dynamics and mechanism. Photosynth. Res. 72:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H., and S. G. Boxer. 1998. Probing excited-state electron transfer by resonance stark spectroscopy. 2. Theory and application. J. Phys. Chem. B. 102:9148–9160. [Google Scholar]

- Zouni, A., H.-T. Witt, J. Kern, P. Fromme, N. Krauss, W. Saenger, and P. Orth. 2001. Crystal structure of photosystem II from Synechococcus elongatus at 3.8 Å resolution. Nature. 409:739–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]