Abstract

MscL is a mechanosensitive channel gated by membrane tension in the lipid bilayer alone. Its structure, known from x-ray crystallography, indicates that it is a homopentamer. Each subunit comprises two transmembrane segments TM1 and TM2 connected by a periplasmic loop. The closed pore is lined by five TM1 helices. We expressed in Escherichia coli and purified two halves of the protein, each containing one of the transmembrane segments. Their electrophysiological activity was studied by the patch-clamp recording upon reconstitution in artificial liposomes. The TM2 moiety had no electrophysiological activity, whereas the TM1 half formed channels, which were not affected by membrane tension and varied in conductance between 50 and 350 pS in 100 mM KCl. Coreconstitution of the two halves of MscL however, yielded mechanosensitive channels having the same conductance as the native MscL (1500 pS), but exhibiting increased sensitivity to pressure. Our results confirm the current view on the functional role of TM1 and TM2 helices in the MscL gating and emphasize the importance of helix-helix interactions for the assembly and functional properties of the channel protein. In addition, the results indicate a crucial role of the periplasmic loop for the channel mechanosensitivity.

INTRODUCTION

Mechanosensitive (MS) channels are channels whose open probability is dependent on membrane tension. They have been hypothesized to be directly involved in physiological functions as diverse as touch, hearing, and osmoregulation (Hamill and Martinac, 2001). In bacteria such as Escherichia coli, the mechanosensitive channels MscL and MscS have been demonstrated to protect cells against osmotic challenge by acting as safety valves. When bacteria are shifted from a high to a low osmolarity medium, the increase in membrane tension triggers the opening of mechanosensitive channels, allowing the release of internal solutes (Berrier et al., 1992; Levina et al., 1999).

MscL from E. coli was the first MS channel to be purified and cloned, by Kung and co-workers (Sukharev et al., 1994). The structure of the MscL homolog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the closed conformation was solved by x-ray crystallography (Chang et al., 1998). The channel is a homopentamer with each subunit consisting of two transmembrane α-helices TM1 and TM2 (Fig. 1 A), connected by an external periplasmic loop, and with the NH2 and COOH termini located in the cytoplasm (Blount et al., 1996a). The closed pore is lined by the five TM1 segments (on the NH2-terminal side) tilted at an oblique angle with respect to the membrane, whereas the five TM2 segments form an external surrounding ring.

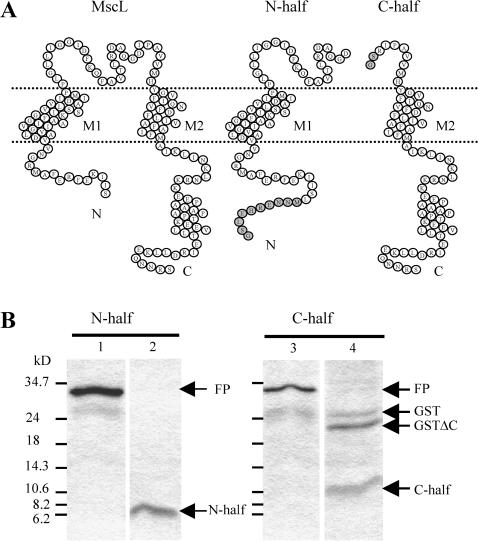

FIGURE 1.

Production of the N-half and C-half part of MscL. (A) Membrane topology of the E. coli MscL subunit, based on PhoA fusion experiments (Blount et al., 1996a) and on the structure of M. tuberculosis MscL (Chang et al., 1998) (left), and of the two halves of MscL produced in E. coli (right). Residual amino acids after GST affinity tag removal are shown in gray: GSLEHRENNM for the N-half and GS for the C-half. (B) Tricine-SDS-PAGE (16.5% acrylamide/bis-acrylamide) patterns showing the fusion proteins produced in E. coli and the resulting cleaved proteins. Both halves of the protein MscL have been produced as N-terminal fusion proteins with glutathion-S-transferase. After fixation to affinity beads, fusion proteins could be displaced by reduced glutathion (lanes 1 and 3). Cleavage by thrombin of the fusion proteins fixed on the column led to elution of the N-half and C-half proteins (lanes 2 and 4). A time dependant band is observed near 21 kDa, corresponding to additional cleavage of GST on its carboxyl end, as verified by N-terminal sequencing. For the C-half part, thrombin cleavage was less efficient (C-half, lane 4). Both fusion proteins have a similar size as expected, but peptides corresponding to each moiety migrate quite differently, and they are not stained efficiently by Coomassie dye. Molecular weight markers are indicated as small bars and related migration values in kilodaltons on the left.

MscL is currently the best-studied MS channel and it has become a model system for the study of mechanosensation. The key questions are how an increase in membrane tension is able to induce a conformational change between the closed and the open state, and what is this conformational change? Like the other prokaryotic mechanosensitive channels (Martinac, 2001; Strop et al., 2003), MscL can be reconstituted functionally in giant liposomes and studied by patch-clamp, indicating that it is gated by membrane tension alone (Häse et al., 1995; Sukharev et al., 1997, 1999). Recently, it was shown that asymmetric addition of lysophosphatidylcholine to one of the leaflets of the liposome bilayer is able to induce opening of the channel even in the absence of the applied pressure (Perozo et al., 2002a). Since the accumulation of lysophospholipids in one of the leaflets of the lipid bilayer is expected to change the intrinsic curvature of the membrane, such a local distortion would be the trigger for the MscL gating. Given the large conductance of MscL, it was initially proposed that upon channel opening, TM2 would intercalate between TM1 helices to form a pore lined by 10 helix transmembrane segments (Cruickshank et al., 1997; Strop et al., 2003). On the basis of molecular modeling, an alternative mechanism was later proposed in which TM1 helices tilted and expanded to form the open pore (Sukharev et al., 2001a,b). Indeed, two recent lines of experiment independently suggest that TM1 helices alone are able to form the open pore. Using site-directed spin labeling and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), Perozo and co-workers (Perozo et al., 2002b) studied the transition of the channel from the closed to the open state. Their results support the notion of an open pore of at least 25 Å, lined mostly by the TM1 helices. Betanzos et al. (2002) have shown how the open conformation of the channel could be trapped during osmotic shock and stabilized by specific disulfide cross-linking between TM1 helices. In contrast, cross-linking of TM1 and TM2 helices of adjacent subunits did not prevent channel gating.

It is still unknown what part of the protein, if any, directly senses the deformation of the membrane and subsequently triggers the transition from the closed to the open conformation. Blount and co-workers, however, recently identified a structural motif Asn-hydrophobic-hydrophobic-Asp present in voltage-gated channels with six-transmembrane domains and in MscL (Kumanovics et al., 2002). They suggested that this motif, which in MscL is located at the basis of the TM1 helix close to its cytoplasmic side, could represent a sensor that might have been highly conserved throughout the evolution.

To progress in our understanding of the molecular gating mechanism of MscL, we have produced and purified two halves of the MscL protein, each of them containing one of the transmembrane segments, i.e., TM1 or TM2. In this study we addressed the following questions: i), Can the TM1 or TM2 segment alone form channels?; ii), Are these channels mechanosensitive?; And finally, iii), what is the electrophysiological activity of the two halves of the MscL protein when they are reconstituted together?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Thrombin, Glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GS-4B) beads and plasmid pGEX-2T were from Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech. Asolectin IV-S (phosphatidyl-choline), isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, antibiotics, and DNase were purchased from Sigma-Adrich (St. Louis, MO). Bio-beads SM-2 were from Biorad (Hercules, CA).

Plasmid construction

E. coli strain DH5α cells containing the plasmid pGEX-1.1 (Häse et al., 1995) were grown at 37°C for 8 h in 20 ml Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with 50 μg/ml ampicillin. This culture was diluted 1:20 and subgrown overnight. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (3000 × g, 15 min, 4°C) and the plasmid DNA extracted using the Qiagen Midi plasmid extraction kit. This plasmid was used for the following constructs: 1), amplification of the N-half MscL (as defined in Fig. 1 A) and incorporation of BamH1 site at the 5′-end of the section was achieved by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the oligonucleotides FORWARD-2: 5′-CGG GAT CCC GAA TCC CTG CTG-3′, and REVERSE-2: 5′-CCG GCA GCT GCA TGT GTC AGA GG-3′; 2), amplification of the C-half MscL (as defined in Fig. 1 A) and incorporation of EcoR1 site at the 3′-end of the section was achieved by PCR using the oligonucleotides FORWARD-1′: 5′-GGG CGG GAT CCC TCG AGC ATA GGG AG-3′, and REVERSE-1′: 5′-GGG CGG AAT TCT TAT TAA TCC CCC TGC GCA TCG CGT AG-3′. The PCR products were then purified using the Qiagen QIAquick PCR purification kit, BamH1/EcoR1 digested and ligated into pGEX-2T vector. Each ligation mixture was then transformed into competent AW737-KO E. coli knockout in the mscL gene by a chromosomal insertion (Sukharev et al., 1994). Host cells were transformed under the following parameters for BIORAD gene pulser and gene controller: 1250 V–25 μF–200 Ω. Clones were isolated by plating on selective media. All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

Protein expression and purification

E. coli strains AW737-KO (500 ml), carrying pGEX-N-half or pGEX-C-half plasmid, were grown at 37°C in LB broth with 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol. After addition of isopropyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (0.1 mM) for induction of protein expression, cells were further grown for 4 h. Cells were harvested, resuspended in 25 ml 50 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM NaCl, 5% sucrose, 2 mM MgSO4, DNase (10 μg/ml), pH 7.6, and passed twice through a French press at 8000 psi The broken cell suspension was centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 × g to pellet and isolate cell debris and inclusion bodies from cytoplasm and membrane vesicles. The pellet was resuspended in 10 ml phosphate-buffered saline (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.4 mM K H2PO4, pH 7.2) containing 0.1% N,N-dimethyldodecylamine-N-oxide (LDAO) for glutathion S-transferase (GST)-N-half and 1% Triton X-100 for GST-C-half, and incubated for 3 h at room temperature. Nonsoluble inclusion bodies and cell debris were eliminated by second centrifugation at 3000 × g. The supernatant was incubated with 0.5 ml GS-4B (bed volume) beads for 3 h at room temperature. The membrane vesicles were ultracentrifuged for 60 min at 100,000 × g, and the pelleted vesicles were resuspended with detergent under conditions similar to that for inclusion bodies. The suspension was ultracentrifuged and the supernatant was incubated with 0.5 ml GS-4B beads for 3 h at room temperature. For both fusion proteins, the beads were then washed four times by centrifugation using a desktop centrifuge for 5 min in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1.5% octyl-glucoside. After the last wash, the beads were resuspended in 500 μl 10 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0, containing 1% octyl-glucoside and 10 units thrombin. After 3 h incubation at room temperature the beads were transferred to a small column (10 × 3 × 30 mm) and washed three times with 500 μl 10 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0, 1% octyl-glucoside. Protein samples were analyzed by 16.5% Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Schägger and von Jagow, 1987). After affinity chromatographic purification, both peptide concentrations were determined using Bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce Chemical) and SDS-PAGE.

Reconstitution in liposomes

N-half and C-half proteins purified with octyl-glucoside were incubated with 1 mg azolectin IV-S lipids at a given protein/lipid ratio in 2 ml 10 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 100 mM KCl, 1% octyl-glucoside, for 30 min at room temperature. Bio-Beads SM-2 (Bio-Rad) were then added at a concentration of 160 mg per ml. For coreconstitution of TM1 and TM2, both peptides were mixed for 3 h in detergent at 4°C before addition of lipids. After 4 h, Bio-Beads were discarded, and the suspension was centrifuged for 25 min at 200,000 × g. The pellet was resuspended in 20 μl HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, and the following suspension was subjected to a dehydration/rehydration cycle to obtain giant proteoliposomes as previously described (Berrier et al., 1989). Rehydration was performed in 10 mM HEPES-KOH, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.4. A quanity of 2 μl of the giant proteoliposome suspension was deposited in a patch-clamp chamber and diluted by 2 ml bath solution (10 mM HEPES-KOH, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.4).

Patch-clamp recording

Single-channel activity was recorded using standard patch-clamp methods. Patch electrodes were pulled from Pyrex capillaries (Corning code 7740) using a P-2000 Sutter Instruments (Novato, CA) laser pipette puller, and were not fire polished before use. Micropipettes were filled with a buffer similar to that of the patch-clamp chamber completed by 2 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM CaCl2. Negative pressure (suction) was applied to the patch pipette by syringe and monitored with a piezo-electric pressure transducer (Bioblock Scientific). Unitary currents were recorded using a Biologic (Grenoble, France) RK-300 patch-clamp amplifier with a 10-GΩ feedback resistance and stored on digital audiotape (Biologic DTR 1200 DAT recorder). Records were subsequently filtered at 1 kHz (−3 dB point) through a four-pole Bessel low pass filter, digitized offline at a rate of 2 kHz, and analyzed on a personal computer, with a program developed by G. Sadoc (Gif sur Yvette). Data were plotted on a Hewlett-Packard LaserJet printer, using Sigmaplot software (Jandel).

RESULTS

Production of the N-half and C-half of MscL

The two parts of the MscL gene corresponding respectively to the N-half and C-half of MscL, as indicated on Fig. 1 A, were cloned into pGEX vectors, allowing N-terminal fusion with GST. The sequence possesses a thrombin site allowing proteolytic cleavage of GST. In both cases the fusion proteins could be expressed and detected by antibody against GST. The yield was low, however, compared to the expression of the full length MscL fused with GST. The fusion proteins were found both in the membrane fraction and in inclusion bodies. Fusion proteins from both fractions were purified using affinity columns. Fig. 1 B shows the electrophoretic migration of the fusion proteins for both N- and C-half moieties eluted after displacement from the affinity column by reduced gluthatione (lanes 1 and 3), and of eluted half moieties cleaved directly by thrombin on the affinity column (lanes 2 and 4). The two N-half and C-half proteins appear as diffused bands on the gels and the C-half moiety fraction is contaminated by GST and truncated GST. Since the amount of protein thus recovered was relatively small and since GST was not expected to have channel activity, this fraction was not further purified. For the N-half moiety, 500 ml culture yielded ∼25 μg protein recovered from the membrane fraction and 50 μg from the inclusion bodies. For the C-half moiety the yields were 50 and 100 μg, respectively. This compares to some 500 μg for the full-length MscL.

Lack of the electrophysiological activity of the C-half MscL moiety

The purified C-half moiety, containing the TM2 segment, was reconstituted into azolectin liposomes. The corresponding proteoliposomes were subjected to a cycle of dehydration-rehydration to produce giant proteoliposomes amenable to patch-clamp recording. Several preparations were assayed with lipid to protein ratios (weight/weight) ranging from 10,000 to 60. Proteins isolated from the membrane fraction as well as from inclusion bodies were used. No spontaneous channel activity that could be attributed to the C-half moiety was observed in 86 patches. The only channel activity that could be recorded was observed at high protein concentration (lipid to protein ratio of 60:1) and was attributed to porin channels (six patches) resulting from the residual contamination by the outer membrane. Indeed, the channels, whose conductance ranged from 200 to 400 pS, were open at low membrane potentials and closed when high positive and negative membrane potentials were applied with kinetics characteristic of porin channel (Berrier et al., 1997). Contamination by porin channels cannot be totally avoided when membrane proteins are purified from E. coli, and this contamination is likely to be revealed when high protein concentrations are used. A total of 54 patches reconstituted with the TM2 fragment alone were tested for MS channel activity by applying negative pressure to the patch pipette. Since all of them remained silent, we concluded that this portion of the MscL protein cannot form channels by itself.

The N-half MscL moiety forms channels that are not activated by pressure

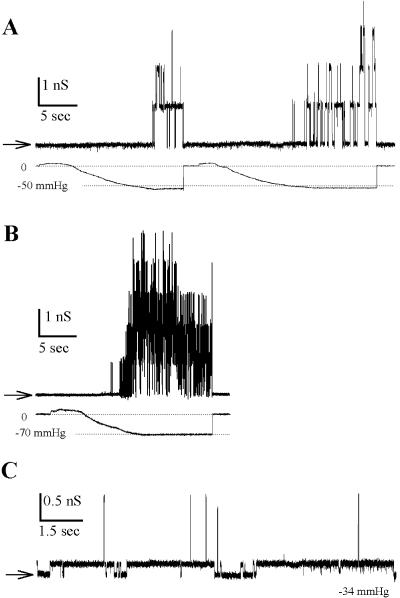

Spontaneous channel activity could be recorded from patches of giant proteoliposomes reconstituted with the N-half moiety of MscL, containing the TM1 segment, purified either from membrane fraction or inclusion bodies. Reconstitution was performed at different lipid to protein ratios: 500, 1000, 1300, and 2000, with a result that the channel activity was observed in 27 out of 34 patches, 25 out of 57 patches, 27 out of 47 patches, and one out of five patches respectively. From patch to patch, channels with different conductance, varying between 50 and 350 pS (in 100 mM KCl symmetrical media), and different kinetics were observed. However, in most cases, the same type of channel was consistently observed in a single patch throughout the recording. To summarize, only one type of channels was observed in 51 patches, two types of channels were observed in 24 patches, and three types of channels were observed in only five patches. Fig. 2 displays examples of such recordings. Fig. 2 A is representative of the most frequently observed kinetic pattern. Fig. 2 B documents a fast flickering pattern that was less often observed. Fig. 2, C and D, are successive segments of the same recording, showing the disappearance of one of the two channels initially present in the patch. Although in some patches channels were more active at one polarity than at the other, this pattern was not consistently observed. No clear voltage dependence could be observed. Suction was systematically applied in 89 patches, including patches that were apparently devoid of channel activity. No pressure-dependent channel was ever observed. When channels were present in the patch, gating was not affected by pressure applied until breakage of the patch (around 50 mm Hg). We noticed that the presence of the N-half proteins apparently increased the fragility of the patches.

FIGURE 2.

Spontaneous channel activity recorded in patches made on giant proteoliposomes reconstituted with the N-half part of MscL. Traces show the most commonly observed activity. Pipette voltage was −20 mV. No pressure was applied to the patch. (A, C, and D) The protein was purified from vesicles and reconstituted at a lipid/protein ratio of 500 (w/w). (B) The peptide was purified from inclusion bodies and reconstituted at a lipid/protein ratio of 1000. Time and conductance scales are indicated by small bars. Arrows indicate the closed levels for all channels in the patches. Bath medium: 100 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4. Pipette medium: similar to bath medium with, in addition, 2 mM CaCl2 and 5 mM MgCl2.

Coreconstitution of the N-half and C-half moieties yield fully functional MscL channels

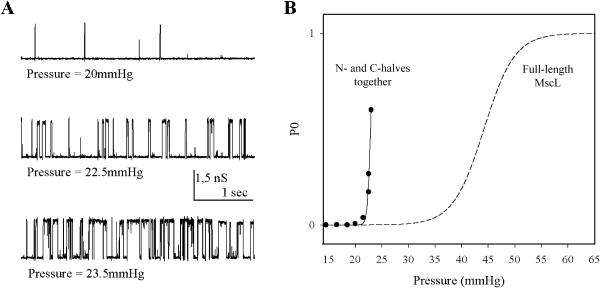

The N-half and C-half moieties of MscL, purified from the membrane fraction, were incubated together in detergent in the presence of lipids in approximately equivalent amounts. After removal of detergent the proteoliposomes were subjected to a cycle of dehydration-rehydration and the resulting giant proteoliposomes were used for the patch-clamp study. Under these conditions, we detected mechanosensitive channels that possessed the characteristics of MscL. As shown in Fig. 3 A, application of negative pressure to a patch that had no spontaneous channel activity resulted in the opening of channels that closed upon release of pressure, as native MscL channels (Fig. 3 B). The channels had the conductance of MscL (1500 pS in 100 mM KCl). Coreconstitution was performed at different lipid to protein ratios with proteins purified from the membrane fraction or inclusion bodies. MscL channels were more frequently detected when the C-half moiety from membrane fractions was used. N-half moieties from both fractions performed equally well. The frequency of observation of MscL channels varied from one preparation to the next. Thus in a preparation for which the lipid to protein ratio was 300, MscL channels were observed in two patches out of 35, whereas in another (lipid/protein ratio of 1000) 88 patches out of 190 had MscL channels. In these two preparations C-half moiety from membrane fractions was used. The number of MscL channels per patch was rather low (from one to four) even at the highest protein concentration (lipid/protein ratio of 300). This is at least 10 times less than the number of channels present in a patch when the full length MscL is used for reconstitution. In some patches, we observed the superposition of spontaneously active channels, presumably due to the N-half moiety and MscL channel activity (Fig. 3 C). In other patches, only TM1 channels were observed. Typically, in a given preparation, out of 190 patches, 61 patches contained MscL channels alone, 27 patches contained MscL and TM1 channels, and 63 patches contained only TM1 channels. We examined the pressure dependence of the reconstituted MscL. The patches were more fragile than in ordinary proteoliposomes, probably due to the presence of TM1. Consequently full activation curve could not be obtained. Strikingly, the sensitivity to pressure of the reconstituted channel was increased as compared to that the native channel (Fig. 4). The pressure required for an open probability of 0.5 was 24.2 ± 2.7 mm Hg (n = 4) for the coassembled channels vs. 44.7 ± 6.8 (n = 3) for that of the native MscL channels. Similarly, the amount of the pressure required for an e-fold change in the channel open probability was 0.69 ± 0.19 mm Hg for the coassembled MscL channel compared to 4.85 ± 0.84 mm Hg for the native channel.

FIGURE 3.

N- and C-halves coreconstituted together form mechanosensitive channels. (A) The N-half and C-half moieties of the protein were incubated together in detergent in equivalent amount and reconstituted in liposomes for patch-clamp experiments. The lipid/protein ratio was 1000 (w/w). Upper trace shows current and lower trace shows pressure applied to the membrane patch. Application of negative pressure activated ion channels that closed upon release of suction. (B) Electrophysiological activity of the native MscL purified and reconstituted in liposomes. (C) Mixed activities of N-half protein and recovered MscL in the same patch under −34 mm Hg suction. MscL activity appears with application of pressure, whereas N-half protein activity is observed before suction (not shown). All recordings were carried out at pipette voltage of −10 mV. Other conditions as in Fig. 2.

FIGURE 4.

Pressure dependence of the reassembled MscL channel. (A) Channel activity of N- and C-halves coreconstituted together at various levels of suction. Levels of pressure are indicated at the bottom of each trace. The lipid/protein ratio was 1000 (w/w). Pipette voltage was −10 mV. Other conditions as in Fig. 2. (B) Open probability P0 versus the applied pressure, at fixed membrane potential (−10 mV pipette), of the channel whose activity is shown in A. The data, obtained from 10-s segments of recording at each pressure, were fitted to a Boltzmann distribution of the form P0 = (1 + exp α (p1/2 − p))−1, where P0 is the open probability, p is the pressure, p1/2 is the pressure at which the open probability is 0.5, and α is the sensitivity. For these data, 1/α = 0.37 mm Hg, p1/2 = 22.9 mm Hg. By way of comparison, the Boltzmann distribution describing the pressure dependence of native MscL channels is shown as a dotted line. The parameters of this distribution (1/α = 4.85 mm Hg, p1/2 = 44 mm Hg) are the average of parameters obtained from three different patches.

DISCUSSION

Here we have attempted to examine the pore forming activity of two truncated parts of the MscL protein, each containing only one transmembrane segment. We showed that such proteins could be produced in E. coli. Although the yield was low, this method is an interesting alternative to the chemical synthesis of transmembrane peptides. We showed that the incorporation in a lipid bilayer of the purified N-half part of MscL, containing the TM1 segment, yielded channels exhibiting multiple conductances that could not be affected in a reproducible manner by either one, negative pressure or voltage. In dealing with single channel activity, observed after reconstitution of purified proteins, one has always to take into account the possibility of contaminations. We are, however, confident that observed channel activities were due to the presence of the N-half moiety since no such channel activities were observed with the C-half moiety produced and purified under similar conditions. Montal and co-workers have shown how chemically synthesized peptides corresponding to transmembrane segments of a channel protein could form ion channels of different conductance and kinetics, after reconstitution in lipid bilayers (Montal, 1995). In the case of the acetylcholine receptor, the TM2 transmembrane segments, once reconstituted in the lipid bilayer formed channels, whereas the TM1 segments (Oiki et al., 1988) or peptides with randomized sequences did not form channels (Oblatt-Montal et al., 1993). Similarly, the TM2 transmembrane segments of the glycine receptor could form channels, whereas the TM1 segments did not (Reddy et al., 1993). A direct interpretation is that the peptides self-assemble as bundles of different multimers that form channels, as do some antimicrobial peptides (Montal, 1995). The fact that the TM1 segment of MscL, which is part of the pore, is able to form channels was not unexpected and is consistent with this explanation. However, several remarks can be made. First, the assembly of N-half parts is a low probability event because the number of channels per patch is rather low, even when the relative amount of protein is high. We know from previous experiments that when full length MscL is reconstituted at a lipid to protein ratio of 500:1, tens of channels are present in every patch. Indeed, if the channel formation by the N-half part were not a rare process, expression of the fusion protein would impair bacterial growth, although in this case it was only slowed down. The very high conductance of MscL (1500 pS in 100 mM KCl) was never observed in these experiments. If the pore of MscL is formed by the TM1 transmembrane segments alone, these segments have to be tilted during the channel opening (Betanzos et al., 2002; Perozo et al., 2002b). Obviously in this case stretch is not able to induce such a tilt of this part of the protein independently of the other half of the protein. It is difficult to speculate on the stoiechiometry of the N-half parts assembly forming different channels. If all these channels resulted from different oligomers of the protein, we would have expected to observe a limited number of conductances. A puzzling observation is that, in our many recordings from the TM1 channels, nearly all conductances between 50 and 350 pS were observed. Therefore, we cannot exclude that some of these channels are not formed exclusively of bundles of α-helices, but may result from temporary defects in the lipid bilayer induced by the amphipatic protein.

In contrast with the N-half moiety, the C-half moiety is unable to form channels on its own. This could not be easily predicted. For instance, the hydrophobicity moment of TM2, which would be expected to reflect its amphipathicity, is higher than that of TM1 in E.coli MscL and in 21 homologs. The observation that TM2 is unable to form channels is difficult to reconcile with the proposal that the TM2 transmembrane segments could be part of the open pore of MscL together with the TM1 segments. Our findings are therefore more consistent with the model of Guy, Sukharev, and co-workers, who proposed that the tilted TM1 transmembrane segments alone enclose the pore of the open channel (Sukharev et al., 2001a,b). This proposition was confirmed by using electron paramagnetic resonance measurements as well as cross-linking experiments (Perozo et al., 2002b; Betanzos et al., 2002).

Blount and co-workers have recently detected a four amino acid motif NxxD in the TM1 helix and have speculated that it could represent a sensor in mechanosensation (Kumanovics et al., 2002). Among different tests of this hypothesis, the authors proposed to examine the electrophysiological activity of this helix. The experiments in this study clearly indicate that the N-half part of the protein alone is unable to form channels that respond to tension. Therefore, the motif at the basis of TM1 helix is very likely not a sensor of membrane tension promoting the tilting of the helix. When mutations are performed in this motif, the sensitivity of the channel to membrane tension is modulated but its mechanosensitivity is not abolished. This does not completely rule out the possibility that this motif, whose conservation is striking, does not play a role in mechanosensation.

Indeed, our experiments show that the C-half part of the protein, which includes the TM2 helix, is essential for the formation of a mechanosensitive channel with MscL characteristics. It is tempting to speculate that TM2 helices form a scaffold that confers the characteristic pore formed by five TM1 helices. It is therefore possible that the TM2 helices, which are in a direct contact with the lipid bilayer (Perozo et al., 2002b), are the ones that sense tension and whose tilting causes the opening of the channel pore.

The currently accepted model for the folding of helical membrane proteins involves two steps (Popot and Engelman, 1990). In the first step hydrophobic segments insert into the membrane as α-helices. In the second step helix-helix interactions drives the assembly of the helices to form the native bundle. This model is supported by experiments in which functional proteins have been assembled from proteolytic or genetically cleaved fragments (reviewed in Popot et al., 1994). That the 10 separated helices of the MscL channel are able to assemble to form a mechanosensitive channel is in itself remarkable and attest to the importance of helix-helix interaction in the conformation of membrane proteins. The process itself is not very efficient since only a fraction of the reconstituted proteins form MscL-type channel. Nevertheless, it is striking to observe that only one kind of channel can be formed: mechanosensitive channels of higher or lower conductance were not observed.

In a previous article, we examined the contributions of the extramembranous part of the channel in mechanosensation by direct application of proteases during patch-clamp experiments performed on MscL reconstituted in artificial liposomes (Ajouz et al., 2000). In these experiments, the channel retained its native orientation with the NH2 and COOH termini facing the recording chamber and the periplasmic loop facing the interior of the patch pipette. When trypsin or chymotrypsin were present in the pipette, we observed that the sensitivity of the MscL channels increased over time. The interpretation of this observation was that the periplasmic loop had been proteolysed, that its integrity was not essential for mechanosensation, but that its cleavage enhanced mechanosensitivity. The experiments reported here clearly demonstrate this proposal and indicate that the loop plays an important role in MscL gating possibly by acting as a spring, which sets the level of mechanosensitivity of the channel. Indeed, mutations in the loop region of MscL from E. coli (Blount et al., 1996b) or of MscL from M. tuberculosis (Maurer et al., 2000) have been shown to lead to a gain of function. More recently, Maurer and Dougherty (2003) reported on random mutagenesis experiments performed on MscL coupled with a high-throughput functional screen. Using this approach they found that loss of function mutations are concentrated in the loop region and in particular in the region of the protein near the headgroups of the lipid bilayer. There is therefore mounting evidence that the loop may constitute a key functional region conferring mechanosensitivity to the MscL channel protein.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stuart Butterly for making one construct used in this study, Anne Bibonne for technical assistance, and P. Decottignies for peptide sequencing.

This work was supported in part by grant CR 521090 from Délégation Générale pour l'Armement and by the Programmes Internationaux de Coopération Scientifique from Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique to A.G. as well as International Research & Exchanges Board Award X00001605 by the Australian Research Council to B.M. and A.G.

References

- Ajouz, B., C. Berrier, M. Besnard, B. Martinac, and A. Ghazi. 2000. Contributions of the different extramembranous domains of the mechanosensitive ion channel MscL to its response to membrane tension. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1015–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrier, C., M. Besnard, and A. Ghazi. 1997. Electrophysiological characteristics of the PhoE porin channel from Escherichia coli. Implications for the existence of a superfamily of ion channels. J. Membr. Biol. 156:105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrier, C., A. Coulombe, C. Houssin, and A. Ghazi. 1989. A patch-clamp study of ion channels of inner and outer membranes and of contact zones of E. coli, fused into giant liposomes. Pressure-activated channels are localized in the inner membrane. FEBS Lett. 259:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrier, C., A. Coulombe, I. Szabo, M. Zoratti, and A. Ghazi. 1992. Gadolinium ion inhibits loss of metabolites induced by osmotic shock and large stretch-activated channels in bacteria. Eur. J. Biochem. 206:559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betanzos, M., C. S. Chiang, H. R. Guy, and S. Sukharev. 2002. A large iris-like expansion of a mechanosensitive channel protein induced by tension. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:704–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount, P., S. I. Sukharev, P. C. Moe, M. J. Schroeder, H. R. Guy, and C. Kung. 1996a. Membrane topology and multimeric structure of a mechanosensitive channel in bacteria. EMBO J. 15:4798–4805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount, P., S. I. Sukharev, M. J. Schroeder, S. K. Nagle, and C. Kung. 1996b. Single residue substitutions that change the gating properties of a mechanosensitive channel in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:11652–11657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, G., R. H. Spencer, A. T. Lee, M. T. Barclay, and D. C. Rees. 1998. Structure of the MscL homolog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a gated mechanosensitive ion channel. Science. 282:2220–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshank, C. C., R. F. Minchin, A. C. Le Dain, and B. Martinac. 1997. Estimation of the pore size of the large-conductance mechanosensitive ion channel of Escherichia coli. Biophys. J. 73:1925–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill, O. P., and B. Martinac. 2001. Molecular basis of mechanotransduction in living cells. Physiol. Rev. 81:685–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häse, C. C., A. C. Le Dain, and B. Martinac. 1995. Purification and functional reconstitution of the recombinant large mechanosensitive ion channel (MscL) of Eschericia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 270:18329–18334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanovics, A., G. Levin, and P. Blount. 2002. Family ties of gated pores: evolution of the sensor module. FASEB J. 16:1623–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levina, N., S. Totemeyer, N. R. Stokes, P. Louis, M. A. Jones, and I. R. Booth. 1999. Protection of Escherichia coli cells against extreme turgor by activation of MscS and MscL mechanosensitive channels: identification of genes required for MscS activity. EMBO J. 18:1730–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinac, B. 2001. Mechanosensitive channels in prokaryotes. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 11:61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, J. A., and D. A. Dougherty. 2003. Generation and evaluation of a large mutational library from the E. coli mechanosensitive channel of large conductance, MscL. Implications for channel gating and evolutionary design. J. Biol. Chem. 278:21076–21082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, J. A., D. E. Elmore, H. A. Lester, and D. A. Dougherty. 2000. Comparing and contrasting Escherichia coli and Mycobacterium tuberculosis mechanosensitive channel (MscL). New gain of Function mutations in the loop region. J. Biol. Chem. 275:22238–22244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montal, M. 1995. Molecular mimicry in channel-protein structure. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 5:501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oblatt-Montal, M., L. K. Buhler, T. Iwamoto, J. M. Tomich, and M. Montal. 1993. Synthetic peptides and four-helix bundle proteins as models systems of the pore-forming structure of channel protein. I. Transmembrane segment TM2 of the nicotinic cholinergic receptor channel is a key pore-lining structure. J. Biol. Chem. 268:14601–14607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oiki, S., W. Danho, V. Madison, and M. Montal. 1988. M2 delta, a candidate for the structure lining the ionic channel of the nicotinic cholinergic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 85:8703–8707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perozo, E., A. Kloda, D. M. Cortes, and B. Martinac. 2002a. Physical principles underlying the transduction of bilayer deformation forces during mechanosensitive channel gating. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:696–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perozo, E., D. M. Cortes, P. Sompornpisut, A. Kloda, and B. Martinac. 2002b. Open channel structure of MscL and the gating mechanisms of mechanosensitive channels. Nature. 418:942–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popot, J.-L., C. De Vitry, and A. Atteia. 1994. Folding and assembly of integral membrane proteins: an introduction. In Membrane Protein Structure. S. H. White, editor. Oxford University Press, New York. 41–96.

- Popot, J.-L., and D. M. Engelman. 1990. Membrane protein folding and oligomerization: the two-stage model. Biochemistry. 29:4031–4037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, G. L., T. Iwamoto, J. M. Tomich, and M. Montal. 1993. Synthetic peptides and four-helix bundle proteins as models systems of the pore-forming structure of channel protein. II. Transmembrane segment M2 of the brain glycine receptor is a plausible candidate for the pore-lining structure. J. Biol. Chem. 268:14608–14615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schägger, H., and G. von Jagow. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166:368–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strop, P., R. Bass, and D. Rees. 2003. Prokaryotic mechanosensitive channels. In Advances in Protein Chemistry. F. M. Richards, D. S. Eisenberg, and J. Kuryan, editors. Membrane Proteins, Vol. 63. D. C. Rees, editor. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. 177–209. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sukharev, S., M. Betanzos, C. S. Chiang, and H. R. Guy. 2001a. The gating mechanism of the large mechanosensitive channel MscL. Nature. 409:720–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev, S., S. R. Durell, and H. R. Guy. 2001b. Structural models of the MscL gating mechanism. Biophys. J. 81:917–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev, S. I., P. Blount, B. Martinac, F. R. Blattner, and C. Kung. 1994. A large-conductance mechanosensitive channel in E. coli encoded by mscL alone. Nature. 368:265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev, S. I., P. Blount, B. Martinac, and C. Kung. 1997. Mechanosensitive channels of Escherichia coli: the mscL gene, protein and activities. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 59:633–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev, S. I., W. J. Sigurdson, C. Kung, and F. Sachs. 1999. Energetic and spatial parameters for gating of the bacterial large conductance mechanosensitive channel MscL. J. Gen. Physiol. 113:525–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]