Abstract

In cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal respiratory enzyme, electron transfers are strongly coupled to proton movements within the enzyme. Two proton pathways (K and D) containing water molecules and hydrophobic amino acids have been identified and suggested to be involved in the proton translocation from the mitochondrial matrix or the bacterial cytoplasm into the active site. In addition to the K and D proton pathways, a third proton pathway (Q) has been identified only in ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus, and consists of residues that are highly conserved in all structurally known heme-copper oxidases. The Q pathway starts from the cytoplasmic side of the membrane and leads through the axial heme a3 ligand His-384 to the propionate of the heme a3 pyrrol ring A, and then via Asn-366 and Asp-372 to the water pool. We have applied FTIR and time-resolved step-scan Fourier transform infrared (TRS2-FTIR) spectroscopies to investigate the protonation/deprotonation events in the Q-proton pathway at ambient temperature. The photolysis of CO from heme a3 and its transient binding to CuB is dynamically linked to structural changes that can be tentatively attributed to ring A propionate of heme a3 (1695/1708 cm−1) and to deprotonation of Asp-372 (1726 cm−1). The implications of these results with respect to the role of the ring A propionate of heme a3-Asp372-H2O site as a proton carrier to the exit/output proton channel (H2O pool) that is conserved among all structurally known heme-copper oxidases, and is part of the Q-proton pathway in ba3-cytochrome c oxidase, are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Hydrogen-bonded networks and regulated electron transfer pathways play the dominant role in the dual function of heme-copper oxidases to reduce O2 to H2O and pump protons (Ostermeier et al., 1996; Kannt et al, 1998; Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001). Cytochrome ba3 is a member of the large family of heme-copper oxidases, and in addition to activating O2 and conserving the energy of the O2 reduction for subsequent ATP synthesis, is able to catalyze the reduction of nitric oxide (NO) to nitrous oxide (N2O) under reducing anaerobic conditions (Giuffrè et al., 1999a; Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001). The crystal structure of the protein indicates that the conserved to all heme-copper oxidase subunit I consists of a low-spin heme b, and a high-spin heme a3/CuB binuclear center, where the dioxygen and nitric oxide reactions take place (Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001). Subunit II contains a mixed valence homodinuclear copper complex (Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001). The a-type heme in ba3 and its counterpart caa3 contain a hydroxyethylgeranylgeranyl side chain instead of a hydroxyethylfarnesyl side chain as seen in most eukaryotic and bacterial oxidases (Iwata et al., 1995; Tsukihara et al., 1995; Ostermeier et al., 1997; Yoshikawa et al., 1998; Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001). Three proton pathways were identified in the crystal structure of ba3 (Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001). They originate at the cytoplasmic side of the membrane and serve for the transfer of protons to either the periplasmic side of the membrane or the active site. Two of these pathways correspond, with respect to their location in the enzyme, to the putative K and D pathways found in the Paracoccus denitrificans (Iwata et al., 1995; Ostermeier et al., 1997) and bovine oxidases (Tsukihara et al., 1995; Yoshikawa et al., 1998), despite the fact that most of the residues belonging to these pathways are not conserved. Importantly, Glu-278 (residue numbering of P. denitrificans) that is located at the end of the D-channel, and is highly conserved in heme-copper oxidases and has been implicated in redox-induced proton transfer reactions, is replaced by Ile in ba3-cytochrome c oxidase (Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001). The third pathway, called Q, starts from the cytoplasmic side of the membrane and leads through the axial heme a3 ligand His-384 to the propionate of the heme a3 pyrrol ring A, and then via Asn-366 and Asp-372 to an accumulation of water molecules, called water pool (Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001). Although there are significant differences concerning the amino residues in the K and D channels between cytochrome ba3 and heme-copper oxidases, the water pool, His-383, Asn-366, and Asp-372 are all highly conserved among all structurally known heme-copper oxidases (Iwata et al., 1995; Tsukihara et al., 1995; Ostermeier et al., 1997; Yoshikawa et al., 1998; Soulimane et al., 2000). Along these lines, it has been postulated that the water pool is part of the proton exit channel, and the primary acceptor for both pumped protons and H2O molecules that are formed at the binuclear center of the enzyme (Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001). Therefore, it is essential to elucidate the protein dynamics near the H2O-Asp-372-heme a3-CuB site.

Fourier transform infrared difference spectroscopy (FTIR) is a powerful structure-specific technique for exploring changes that occur to individual amino acid residues in a protein as a result of changes to redox and ligation states. The FTIR difference approach has also been used to investigate the CO-photoproduct and the electrochemical oxidized-minus-reduced difference spectra of heme-copper oxidases (Hellwig et al., 1998, 1999, 2002; Iwase et al., 1999; Rich and Breton, 2001; Bailey et al., 2002; Heitbrink et al., 2002; Koutsoupakis et al., 2002, 2003a,b,c; Pinakoulaki et al., 2002a; Stavrakis et al., 2002; Tomson et al., 2002). In the latter case, the perturbation is the change in the redox state of the metal centers, whereas in the former it is the photodissociation of CO from the heme. Recently, it was demonstrated that although the exogenous ligand vibrations (CO) were essentially identical between the room- and low-temperature FTIR spectra of photodissociated CO-cytochromes aa3 and bo3, significant differences exist in the protein bands between these temperatures (Bailey et al., 2002). It was suggested that these differences originate from the fact that at room temperature, CO has dissociated from CuB, whereas at low temperature (80 K) the final state has CO coordinated to CuB. Moreover, with the ligand dissociation approach the highly conserved Glu-278 (P. denitrificans numbering) in the bovine, P. denitrificans, Rhodobacter sphaeroides, and bo3-cytochrome oxidases, has been proposed to be involved in protonation/deprotonation reactions, and most recently in the protonation reactions during the catalytic cycle of cytochrome c oxidase from bovine (Iwaki et al., 2003), P. denitrificans (Iwaki et al., 2003), and R. sphaeroides (Nyquist et al., 2003).

Due to the unusual ligand-binding kinetic properties of its binuclear center, cytochrome ba3 oxidase is unique among the heme-copper oxidases in being susceptible to a detailed analysis of its ligation dynamics in the heme a3-CuB site (Goldbeck et al., 1992; Surerus et al., 1992; Woodruff, 1993; Giuffrè et al., 1999b; Koutsoupakis et al., 2002, 2003a,b,c). Resonance Raman (RR), electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR), electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopies, in conjunction with permutations of 13C- and 15N-labeled cyanide have indicated that the reaction of oxidized ba3 with cyanide yields heme a3-CN-CuB(II)-CN complex (Surerus et al., 1992). The comparative kinetics data on CO photodissociation and rebinding of various heme-copper oxidases and the derived activation parameters have indicated that the CO-ligation/release mechanism in cytochrome ba3 follows that found in other heme-copper oxidases (Woodruff, 1993; Koutsoupakis et al., 2002, 2003a,b,c), and proceeds according to the following scheme:

|

(1) |

In contrast to the bovine aa3 oxidase, CuB of cytochrome ba3 has a relative high affinity for CO (K1 > 104), whereas the transfer of CO to heme a32+ is characterized by a small k2 = 8 s−1, and by a k−2 = 0.8 s−1 that is 30-fold greater than that of the bovine aa3 (Giuffrè et al., 1999b; Koutsoupakis et al., 2002).

In our previous cytochrome ba3 work, we identified the equilibrium CuB1+-CO complex, and concluded that the environment of the binuclear center is not altered in the pD-5.5–9.7 range. (Koutsoupakis et al., 2002). The time-resolved step-scan FTIR (TRS2) difference spectra revealed the dynamics of the binuclear center and showed protein conformational changes near the heme a3 propionates (Koutsoupakis et al., 2002). In subsequent work we have demonstrated, that the ligand delivery channel is located at the CuB site, and the presence of a docking site near the heme a3 propionates (Koutsoupakis et al., 2003a,b,c). In recent FTIR studies it has been noted that functional groups, including carboxyl groups of amino acids residues, are difficult to deuterate (Okuno et al., 2003). Therefore, we have investigated the CO-bound ba3 complex in the pH 5.5–9.5 range, aiming to finalize the pH/pD sensitivity of the binuclear center by FTIR. We have also investigated the protein response subsequent to CO photolysis from heme a3 by TRS2 FTIR spectroscopy. On the basis of the tentative assignments of the 1695/1708 and 1726 cm−1 modes, the TRS2 data may reflect that Asp-372 undergoes deprotonation upon photodissociation of CO from heme a3, and that there is a H-bonded connectivity between the ring A propionate of heme a3-Asp-372-H2O. By combining our results with those from a variety of other experiments, we postulate that the ring A propionate of heme a3-Asp-372-H2O site, which is conserved among all structurally known heme-copper oxidases, and is part of the Q-proton pathway in cytochrome ba3, forms an output proton channel. This way, the ring A propionate of heme a3-Asp-372-H2O group may accept a proton, which in turn causes release of a proton to the exit channel, the so-called water pool.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cytochrome ba3 was isolated from Thermus thermophilus HB8 cells according to previously published procedures (Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001). The samples used for the FTIR measurements had an enzyme concentration of ∼1 mM and were placed in a desired buffer (pH 5.25–6.5, MES; pH 7.5, HEPES; pH 8.5–9.8, CHES). The pD solutions prepared in D2O buffers were measured by using a pH meter and assuming pD = pH (observed) +0.4. Dithionite reduced samples were exposed to 1 atm CO (1 mM) in an anaerobic cell to prepare the carbonmonoxy adduct and transferred to a tightly sealed FTIR cell with CaF2 windows, under anaerobic conditions. CO gas (99.9%) was obtained from Messer (Frankfurt, Germany) and isotopic CO (91.6% 13C16O and 8.4% 13C18O) was purchased from Isotec (Miamisburg, OH). FTIR measurements were performed on a Bruker (Newark, DE) Equinox IFS 55 spectrometer equipped with a mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector (Graseby Infrared D316, response limit 600 cm−1). The experimental techniques used for generating and timing the green photolysis pulse (532 nm and 10 ns) and the IR probe beam to obtain time-resolved step-scan FTIR difference spectra have been reported (10, 17–19). Optical absorption spectra were recorded with a Perkin-Elmer (Fremont, CA) Lamda 20 ultraviolet-visible spectrometer before and after the FTIR measurements to ensure the formation and stability of the CO adducts.

RESULTS

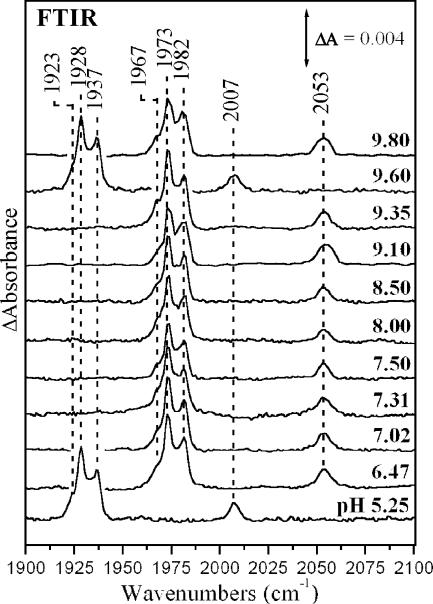

Fig. 1 shows the FTIR spectra of CO-bound cytochrome ba3 in the pH 5.25–9.8 range. The spectra exhibit peaks at 1967, 1973, and 1982 cm−1 that have been assigned (Koutsoupakis et al., 2002) to the C-O stretching modes of heme a3-CO (complex B in Scheme 1) originating from three different conformers, and the C-O stretching mode of CuB-CO (complex A) located at 2053 cm−1. These modes are downshifted to 1923, 1928, 1937, and 2007 cm−1, respectively, when 12CO is replaced by 13CO. The intensity and bandwidth of all three heme a3-CO modes remains unchanged in the pH 5.25–9.8 range. Similar observations have been reported for the bovine enzyme (Einarsdóttir et al., 1988; Iwase et al., 1999; Rich and Breton, 2001). The insensitivity of heme a3-CO to pH demonstrates that the properties of the proximal to heme a3 His-384, that is part of the Q-proton pathway, and known to affect the frequencies of the heme a3 bound CO, remain unchanged in the pH 5.25–9.8 range (Pinakoulaki et al., 2002b). The insensitivity of complex A to pH changes indicates that the environment of the CuB-N(His) ligands that is distal to the bound heme a3-CO also remains unchanged in the pH range 5.25–9.8.

FIGURE 1.

FTIR spectra of the cytochrome ba3-CO complex at the indicated pH values, 293 K. The spectra at pH 5.25 and 9.60 correspond to the ba3-13CO complex. Enzyme concentration was 1 mM and the pathlength 15 μm. The spectral resolution was 2 cm−1 except for the spectra at pH 9.10 and 9.80, where it was 4 cm−1.

In the oxidized-minus-reduced (electrochemical) FTIR difference spectra of aa3 oxidase from P. denitrificans the observation of a trough/peak pattern in the 1700 cm−1 region has been interpreted as an environmental change induced by the change in the redox state of the metal centers (Hellwig et al., 1998). In the FTIR difference spectra obtained upon CO-photolysis from the heme Fe, the appearance of a negative peak in the 1700 cm−1 region (protonated carboxylic acids) has been interpreted as deprotonation of a carboxyl group (Rich and Breton, 2001; Heitbrink et al., 2002; Nyquist et al., 2003; Okuno et al., 2003). With these approaches the properties of the highly conserved Glu-278 in heme-copper oxidases have been investigated. In ba3-cytochrome c oxidase Glu is replaced by Ile, and no trough/peaks patterns were observed in the oxidized-minus-reduced FTIR difference spectra in the 1700 cm−1 region (Hellwig et al., 1999). This observation indicates that a change in the redox state of the metal centers is not observed as a change in the protonation/deprotonation of Glu and/or Asp residues in the enzyme.

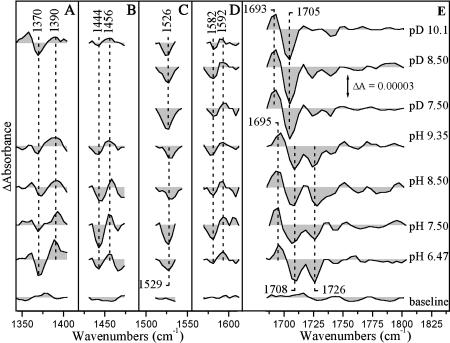

Signals in the amide I region (1620–1690 cm−1) can be attributed to changes of the C=O modes caused by perturbation in the polypeptide backbone and, to the C=O modes of Asn and Gln (Hellwig et al., 1998). Coupled CN stretching and NH bending modes and, the asymmetric COO− modes from deprotonated heme propionates and Glu and Asp side chains are expected in the 1530–1590 cm−1 region (Hellwig et al., 1998). It has been established that the deprotonated symmetric COO− vibrations of heme-propionates and Asp residues are expected at 1350 and 1450 cm−1, respectively, whereas the C=O bonds of the protonated forms are at 1730 cm−1 (Hellwig et al., 1998, 1999, 2002). Also, the asymmetric vibrations of heme-propionates and Asp are located at 1530 and 1590 cm−1, respectively (Hellwig et al., 1998, 1999, 2002). Fig. 2 collects TRS2 FTIR difference spectra (coaveraged first 100 μs after photodissociation of CO) in the pH 6.5–9.35 and pD 7.5–10.1 range. The spectra represent the difference between the heme a3-CO and the CuB-CO species because at 5–100 μs subsequent to CO photolysis, the ligand is bound to CuB (Koutsoupakis et al., 2002, 2003a,b,c). The TRS2 FTIR difference spectra in the 1690–1780 cm−1 region (Fig. 2 E) present an excellent “W” shape characteristic of substantial perturbation of carboxyl groups upon light-induced dissociation of CO from heme a3 and subsequent ligation to CuB. The C=O stretching band that we tentatively assign to the ring A of heme a3 propionate is seen as a derivative-shaped feature in the TR-FTIR difference spectrum with the trough/peak at 1708/1695 cm−1 that is 2–3 cm−1 higher than that observed in D2O (Fig. 2 E). The frequency at 1695 cm−1 in the transient spectra means weaker C=O bond and therefore stronger H-bonding to surrounding groups. The other half of the “W” shape difference spectrum consists of a negative band at 1726 cm−1. We also tentatively assign the 1726 cm−1 negative band to the C=O stretch of Asp-372 (T. Thermophilus sequencing number) because neither Glu nor other Asp residues are near the binuclear center, where the induced perturbation is expected to affect the structures of nearby residues. The TRS2 FTIR difference spectra in the pH 6.47–9.35 range show little change. The insensitivity of the 1726 cm−1 mode to external pH indicates that the pKa of Asp-372 must be higher than 9.4. The spectra obtained in the pD 7.5–10.1 range show that the 1726 cm−1 mode is absent (see below). The peak/trough of the propionate C=O stretching band observed at 1693/1705 cm−1 at pD 7.5 and 8.5 is similar to that obtained at pD 10.1 but with a noticeable intensity increase of the 1705 cm−1 trough in all the pD experiments. The rate of decay of the transient 1694(+)/1706(−) signals attributed to perturbation of the heme a3 propionates (COOH) displays similar time constant as the transient CuB1+-CO complex (Koutsoupakis et al., 2002). Although we have not been able to monitor the kinetics of the 1726 cm−1 species accurately, due to interference from H2O in this frequency range, the TRS2-FTIR spectra at times longer than 2 ms (data not shown) show a substantial decrease of the 1726 cm−1 mode, suggesting that there is a coupling between ligation dynamics in the binuclear center and the environment sensed by both the Asp-372 and the heme a3 propionates (Koutsoupakis et al., 2002). Based on 13C labeling experiments in aa3 oxidase from P. denitrificans (Behr et al., 2000) the modes at 1570 and 1538 have been assigned to ν(COO−)asym of heme propionates. Intensity changes and/or frequency shifts of the symmetric and asymmetric vibrations that could be attributed to both the deprotonated forms of heme-propionates and Asp-372 in ba3 oxidase are observed (Hellwig et al., 1999). These include the peaks/troughs at 1390/1370 cm−1 (ν(COO−)sym) of ring A propionate of heme a3 and at 1456/1444 cm−1 (ν(COO−)sym) of Asp-372. Furthermore, the negative band at 1529 cm−1 and the peak/trough at 1592/1582 cm−1 can be tentatively assigned to ν(COO−)asym of the ring A propionate of heme a3 and of Asp-372, respectively. Comparison of the pH/pD spectra shows that there is noticeable downshift (3 cm−1) of ν(COO−)asym of propionates at 1526 cm−1 in the pD 7.5–10.1 range. In addition, the 1456/1444 cm−1 ν(COO−)sym of Asp-372 has lost most of its intensity at pD 10.1 indicating alterations in the Asp-372 environment due to H/D exchange. It should be noted, however, that the deprotonated forms of both the heme-propionates ν(COO−)sym and Asp-372 persist up to pH 6.5. The appearance of COO(H) modes ascribed to heme-propionates (Fig. 2, A, C, and E) and Asp (Fig. 2 B, D, and E) in both the protonated (Fig. 2 E) and deprotonated (Fig. 2, A–D) spectral region of the TRS2 FTIR-difference spectra indicates the presence of both conformations. Interestingly, in the oxidized-minus-reduced electrochemical FTIR difference spectra of ba3 only the protonated forms of the propionates were observed, and no modes ascribed to either protonated or deprotonated Glu and/or Asp were observed (Hellwig et al., 1999).

FIGURE 2.

Time-resolved step-scan FTIR difference spectra of the CO-bound form of fully reduced cytochrome ba3 oxidase, at the indicated pH and pD values, after CO photolysis from heme a3. Each spectrum is the average of 20 individual spectra from 5 to 100 μs. The pathlength was 15 and 30 μm for the pH and pD samples, respectively, and the spectral resolution 8 cm−1. The time resolution was 5 μs and 10 coadditions were collected and averaged per data point. The excitation wavelength was 532 nm (4 mJ/pulse) and three measurements were recorded and averaged for each data set. The spectra are normalized to the intensity of the 2053 cm−1 mode (CuB1+-CO transient species).

DISCUSSION

TRS2-FTIR spectroscopy has already proven to be a very powerful technique in studying transient changes at the level of individual amino acids during protein action. The intensity changes and frequency shifts of side chains and backbone structures observed in the TR-FTIR difference spectra is the result of the perturbation induced by the photodissociation of CO from heme a3 and its subsequent binding to CuB, to structures near heme a3 and CuB. The following discussion for the behavior of the ring A propionates and Asp-372 is based on our tentative assignments. The observation of the 1695/1708 cm−1 peak/trough and its subsequent shift to 1693/1705 cm−1 upon H/D exchange is similar to that observed in the oxidized-minus-reduced spectra from which it was concluded that the heme-propionates in the ba3 oxidase from T. thermophilus are essentially protonated (Hellwig et al., 1999). The presence of deprotonated signals at 1390/1370 cm−1 indicates, however, that this is not the case. Obviously there is an equilibrium of COO− ↔ COOH. The shift of the 1529 cm−1 mode to 1526 cm−1 upon H/D exchange indicates a dependence on local environment and/or hydrogen bonding interactions. Similar conclusion can be drawn from the reduced intensity of the 1456/1444 cm−1 modes in the D2O experiments. To account for the lack of an observable negative peak at 1726 cm−1 in the D2O experiments we suggest that the loss of the H-bonding connectivity in the local environment of heme a3-Asp-372-H2O upon H/D exchanges do not alter the deuterated Asp-372, and thus, we do not observe a negative peak upon the induced perturbation (CO-photolysis from heme a3). Consequently, the proton connectivity between the three groups is disrupted in the presence of D2O, allowing Asp-372 to adopt a conformation that is significantly different from that observed in the pH experiments. Therefore, the detection of the deprotonated Asp-372 is not only the result of the induced perturbation, but rather a combination of the H-bonded connectivity of the three groups that is lost in the presence of D2O. Taken together, the detection of both protonated and deprotonated forms of the ring A of heme a3 propionate and the deprotonated Asp-372 in conjunction with the dependence of their deprotonated forms on the local environment suggests a protonic connectivity between the ring A propionate of heme a3, Asp-372, and a H2O molecule that is part of the Q-proton pathway.

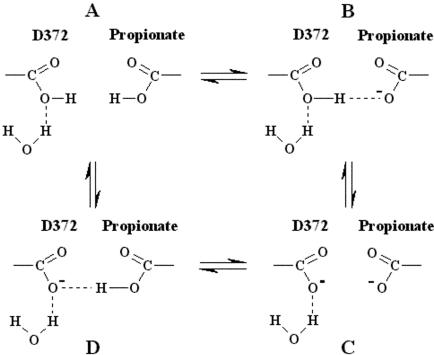

One of the strongest interactions between different groups in heme-copper oxidases is that between the ring A propionate and Asp-372 because the two carboxyl groups are only 3.3 Å apart (Kannt et al., 1998). It was concluded that net protonation of the coupled system will depend on the interaction with the environment and that these two residues share a single proton over a pH 4–11.5 range (Kannt et al., 1998). In addition, this network recently has been proposed as a part of the exit pathway for the pump protons (Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001). To account for the presence of both the protonated and deprotonated forms of the ring A propionate and only the deprotonated form of Asp-372, we present in Fig. 3 a schematic view, based on the TRS2 FTIR data presented here and the crystal structure (Soulimane et al., 2000; Than and Soulimane, 2001), that involves the Asp-372/propionate pair and a H2O molecule. In the scheme, we invoke a specific role to the ring A propionate-Asp-372 to proton motion. This pair may accept a proton either in the oxidative or reductive phase (Verkhovsky et al., 1999), which in turn causes release of a proton to the water pool. The accumulation of H2O molecules has been identified in the P. denitrificans oxidase and its involvement in proton exit channels has been demonstrated by mutagenesis experiments (Ostermeier et al., 1996; Kannt et al., 1998). It is important to note that in the scheme presented here only states B and D, in which a single proton is shared between the ring A propionate and Asp-372, may accept a proton that in turn causes the release of a proton to the water pool. We postulate that this pathway is blocked when both groups are protonated (state A) or deprotonated (state C). Although we do not know the source of the proton, our data strongly indicate that it is not from His-283 or any of the other CuB-His ligands (Koutsoupakis et al., 2002). This sequential or concerted H-bonded connectivity between the environments sensed by the ring A heme a3 propionate-Asp-372-H2O could have an activation energy for proton motion. The abovementioned protonic connectivity and the fast equilibrium of the water pool with bulk solvent suggest that the water pool may serve as a primary acceptor for both the H2O molecules, formed during the catalytic turnover, and pumped protons.

FIGURE 3.

Schematic view of the protonic connectivity between the ring A heme a3 propionate-Asp-372-H2O of the Q-proton pathway in ba3-cytochrome c oxidase.

The exchangeable protons could play a vital role in the biological function of the enzyme. The first step in locating possible sites of proton motion requires identification of labile protons that could be either redox linked or perturbed by ligand motion; in this case, the CO photodissociation from heme a3. The model discussed above postulates the role of the ring A heme a3 propionate-Asp-372-H2O site in the Q-proton channel as a proton carrier to the water pool, demonstrating a facile pathway connecting the catalytic binuclear center and the exit/output proton channel. Based on the status of the ring A heme a3 propionate-Asp-372-H2O site in all structurally known heme-copper oxidases we suggest that our data do not reflect only specific properties of the ba3-cytochrome c oxides but rather are extended to the superfamily of heme-copper oxidases. The lack of similar observation in other heme-copper oxidases containing Glu-278 can be explained by the observation of difference peaks near 1734 cm−1 that have been attributed to Glu-278. This way, strong overlap between the Glu and Asp modes in that frequency domain may have prevented the spectral isolation of the C=O stretching vibration of Asp that is located near the water pool. Experiments are in progress with emphasis on these questions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stavros Stavrakis for excellent technical assistance and Dr. Eftychia Pinakoulaki for reading the manuscript.

This work was partially supported by the Greek Ministry of Education.

Abbreviations used: FTIR, Fourier transform infrared; TRS2-FTIR, time-resolved step-scan Fourier transform infrared; MCT, mercury cadmium telluride; RR, resonance Raman.

References

- Bailey, J. A., F. L. Tomson, S. L. Mecklenburg, G. M. MacDonald, A. Katsonouri, A. Puustinen, R. B. Gennis, W. H. Woodruff, and R. B. Dyer. 2002. Time-resolved step-scan Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of the CO adducts of bovine cytochrome c oxidase and of cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 41:2675–2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr, J., H. Michel, W. Mäntele, and P. Hellwig. 2000. Functional properties of the heme propionates in cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Evidence from FTIR difference spectroscopy and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 39:1356–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einarsdóttir, Ó., M. G. Choc, S. Weldon, and W. S. Caughey. 1988. The site and mechanism of dioxygen reduction in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 263:13641–13654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrè, A., G. Stubauer, P. Sart, M. Brunori, W. G. Zumft, G. Buse, and T. Soulimane. 1999a. The heme-copper oxidases of Thermus thermophilus catalyze the reduction of nitric oxide: evolutionary implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:14718–14723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrè, A., E. Forte, G. Antonini, E. D'Itri, M. Brunori, T. Soulimane, and G. Buse. 1999b. Kinetic properties of ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus: effect of temperature. Biochemistry. 38:1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbeck, R. A., O. Einarsdótir, T. D. Dawes, D. B. O'Connor, K. K. Surerus, J. A. Fee, and D. S. Kliger. 1992. Magnetic circular dichroism study of cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus: spectral contributions from cytochromes b and a3 and nanosecond spectroscopy of carbon monoxide photodissociation intermediates. Biochemistry. 31:9376–9387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitbrink, D., H. Sigurdson, C. Bowlwien, P. Brzezinski, and J. Heberle. 2002. Transient binding of CO to CuB in cytochrome c oxidase is dynamically linked to structural changes around a carboxyl group: a time-resolved step-scan Fourier transform infrared investigation. Biophys. J. 82:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig, P., J. Behr, C. Ostermeier, O.-M. H. Richter, U. Pfitzner, A. Odenwald, B. Ludwig, H. Michel, and W. Mäntele. 1998. Involvement of glutamic acid 278 in the redox reaction of the cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans investigated by FTIR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 37:7390–7399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig, P., T. Soulimane, G. Buse, and W. Mäntele. 1999. Electrochemical, FTIR, and UV/VIS spectroscopic properties of the ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Biochemistry. 38:9648–9658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig, P., U. Pfitzner, J. Behr, B. Rost, R. P. Pasavento, W. V. Donk, R. B. Gennis, H. Michel, B. Ludwig, and W. Mäntele. 2002. Vibrational modes of tyrosines in cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans: FTIR and electrochemical studies on Tyr-D4-labeled and on Tyr280His and Tyr35Phe mutant enzymes. Biochemistry. 41:9116–9125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaki, M., A. Puustinen, M. Wikström, and P. Rich. 2003. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy of the PM and F intermediates of bovine and Paracoccus denitrificans cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 42:8809–8817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase, T., C. Varotsis, K. Shinzawa-Itoh, S. Yoshikawa, and T. Kitagawa. 1999. Infrared evidence for CuB ligation of photodissociated CO of cytochrome c oxidase at ambient temperatures and accompanied deprotonation of a carboxyl side chain of protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121:1415–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, S., C. Ostermeier, B. Ludwig, and H. Michel. 1995. Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Nature. 376:660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannt, A., C. R. D. Lancaster, and H. Michel. 1998. The coupling of electron transfer and proton translocation: electrostatic calculations on Paracoccus denitrificans cytochrome c oxidase. Biophys. J. 74:708–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoupakis, K., S. Stavrakis, E. Pinakoulaki, T. Soulimane, and C. Varotsis. 2002. Observation of the equilibrium CuB-CO complex and functional implications of the transient heme a3 propionates in cytochrome ba3-CO from Thermus thermophilus. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and time-resolved step-scan FTIR studies. J. Biol. Chem. 277:32860–32866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoupakis, K., S. Stavrakis, T. Soulimane, and C. Varotsis. 2003a. Oxygen-linked equilibrium CuB-CO species in cytochrome ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Implications for an oxygen channel at the CuB site. J. Biol. Chem. 278:14893–14896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoupakis, K., S. T. Soulimane, and C. Varotsis. 2003b. Docking site dynamics of ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 278:36806–36809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoupakis, K., S. T. Soulimane, and C. Varotsis. 2003c. Ligand binding in a docking site of cytochrome c oxidase: a time-resolved step-scan Fourier transform infrared study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:14728–14732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyquist, R. M., D. Heitbrink, C. Bolwien, R. B. Gennis, and J. Heberle. 2003. Direct observation of protonation reactions during the catalytic cycle of cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:8715–8720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno, D., T. Iwase, K. Shinzawa-Itoh, S. Yoshikawa, and T. Kitagawa. 2003. FTIR detection of protonation/deprotonation of key carboxyl side chains caused by redox change of the CuA-heme a moiety and ligand dissociation from the heme a3-CuB center of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:7209–7218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermeier, C., S. Iwata, and H. Michel. 1996. Cytochrome c oxidase. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6:460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermeier, C., A. Harrenga, U. Ermler, and H. Michel. 1997. Structure at 2.7 Å resolution of the Paracoccus denitrificans two-subunit cytochrome c oxidase complexed with an antibody FV fragment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:10547–10553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinakoulaki, E., T. Soulimane, and C. Varotsis. 2002a. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and step-scan time-resolved FTIR spectroscopies reveal a unique active site in cytochrome caa3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 277:32867–32874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinakoulaki, E., U. Pfitzner, B. Ludwig, and C. Varotsis. 2002b. The role of the cross-link His-Tyr in the functional properties of the binuclear center in cytochrome c oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:13563–13568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich, P. R., and J. Breton. 2001. FTIR studies of the CO and cyanide adducts of fully reduced bovine cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 40:6441–6449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulimane, T., G. Buse, G. P. Bourenkov, H. D. Bartunik, R. Huber, and M. E. Than. 2000. Structure and mechanism of the aberrant ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. EMBO J. 19:1766–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavrakis, S., K. Koutsoupakis, E. Pinakoulaki, A. Urbani, M. Saraste, and C. Varotsis. 2002. Decay of the transient CuB-CO complex is accompanied by formation of the heme Fe-CO complex of cytochrome cbb3-CO at ambient temperature: evidence from time-resolved Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:3814–3815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surerus, K. K., W. A. Oertling, F. Chaoliang, R. J. Gurbiel, O. Einarsdóttir, W. E. Antoline, R. B. Dyer, B. M. Hoffman, W. H. Woodruff, and J. A. Fee. 1992. Reaction of cyanide with cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus: spectroscopic characterization of the Fe(II)a3-CN·Cu(II)B-CN complex suggests four 14N atoms are coordinated to CuB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:3195–3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Than, M. E., and T. Soulimane. 2001. Ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. In Handbook of Metalloproteins. A. Messerschimdt, R. Huber, T. Poulos, and K. Wieghardt, editors. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., Chichester, UK. 363–378.

- Tomson, F., J. A. Bailey, R. B. Gennis, C. J. Unkefer, Z. Li, L. A. Silks, R. A. Martinez, R. J. Donahoe, R. B. Dyer, and W. H. Woodruff. 2002. Direct infrared detection of the covalently ring linked His-Tyr structure in the active site of the heme-copper oxidases. Biochemistry. 41:14383–14390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukihara, T., H. Aoyama, E. Yamashita, T. Tomizaki, H. Yamaguchi, K. Shinzawa-Itoh, R. Nakashima, R. Yaono, and S. Yoshikawa. 1995. Structures of metal sites of oxidized bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 Å. Science. 269:1069–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhovsky, M. I., A. Jasaitis, M. L. Verkhovskaya, J. E. Morgan, and M. Wikström. 1999. Proton translocation by cytochrome c oxidase. Nature. 400:480–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff, W. H. 1993. Coordination dynamics of heme-copper oxidases. The ligand shuttle and the control and coupling of electron transfer and proton translocation. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 25:177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, S., K. Shinzawa-Itoh, R. Nakashima, R. Yaono, E. Yamashita, N. Inoue, M. Yao, M. J. Fei, C. P. Libeu, T. Mizushima, H. Yamaguchi, T. Tomizaki, and T. Tsukihara. 1998. Redox-coupled crystal structural changes in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Science. 280:1723–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]