Abstract

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed using the recently determined crystal structure of the reovirus attachment protein, σ1. These studies were conducted to improve an understanding of two unique features of σ1 structure: the protonation state of Asp345, which is buried in the σ1 trimer interface, and the flexibility of the protein at a defined region below the receptor-binding head domain. Three copies of aspartic acids Asp345 and Asp346 cluster in a solvent-inaccessible and hydrophobic region at the σ1 trimer interface. These residues are hypothesized to mediate conformational changes in σ1 during viral attachment or cell entry. Our results indicate that protonation of Asp345 is essential to the integrity of the trimeric structure seen by x-ray crystallography, whereas deprotonation induces structural changes that destabilize the trimer interface. This finding was confirmed by electrostatic calculations using the finite difference Poisson-Boltzmann method. Earlier studies show that σ1 can exist in retracted and extended conformations on the viral surface. Since protonated Asp345 is necessary to form a stable, extended trimer, our results suggest that protonation of Asp345 may allow for a structural transition from a partially detrimerized molecule to the fully formed trimer seen in the crystal structure. Additional studies were conducted to quantify the previously observed flexibility of σ1 at a defined region below the receptor-binding head domain. Increased mobility was observed for three polar residues (Ser291, Thr292, and Ser293) located within an insertion between the second and third β-spiral repeats of the crystallized portion of the σ1 tail. These amino acids interact with water molecules of the solvent bulk and are responsible for oscillating movement of the head of ∼50° during 5 ns of simulations. This flexibility may facilitate viral attachment and also function in cell entry and disassembly. These findings provide new insights about the conformational dynamics of σ1 that likely underlie the initiation of the reovirus infectious cycle.

INTRODUCTION

The initial step in viral infection is the attachment of the virus to specific host molecules on the cell surface. This primary interaction between the virus and its host is a critical determinant of viral disease outcome and a potential target for antiviral therapy. For mammalian reoviruses, this initial step is mediated by the attachment of outer-capsid protein σ1 to junctional adhesion molecule 1 (JAM1) (Barton et al., 2001). Reoviruses form nonenveloped icosahedral particles (Dryden et al., 1993) that contain a segmented double-stranded RNA genome. They most often infect children and can cause mild gastrointestinal or respiratory illnesses, although most infections are asymptomatic (Tyler, 2001; Tyler et al., 1986). Reovirus virions are ∼850 Å in diameter and consist of two shells. Five structural proteins (λ1, λ2, λ3, μ2, and σ2) form the inner shell (or “core”), the crystal structure of which has been determined (Reinisch et al., 2000). The core is surrounded by an outer shell that contains the three proteins (μ1, σ1, and σ3) responsible for viral attachment to the cell surface and penetration into the cytoplasm. The recently reported crystal structures of σ3 alone (Olland et al., 2001) and in complex with μ1 (Liemann et al., 2002) provide insights into the molecular events essential for viral entry.

The reovirus attachment protein, σ1, is a long, fiber-like molecule with head-and-tail morphology and several defined regions of flexibility within its tail (Fraser et al., 1990). The σ1 tail partially inserts into the virion at the twelve vertices of the icosahedral particle, whereas the σ1 head projects away from the virion surface (Dryden et al., 1993; Furlong et al., 1988). All three major reovirus serotypes engage JAM1 (J. A. Campbell and T. S. Dermody, unpublished observations) likely via sequences located in the σ1 head (Barton et al., 2001). In addition, some reoviruses use carbohydrate-based co-receptors for cellular attachment (Chappell et al., 2000). The σ1 protein undergoes a dramatic conformational change from a retracted to an elongated form during viral disassembly (Dryden et al., 1993; Furlong et al., 1988; Nibert et al., 1995). The nature of this change is not known.

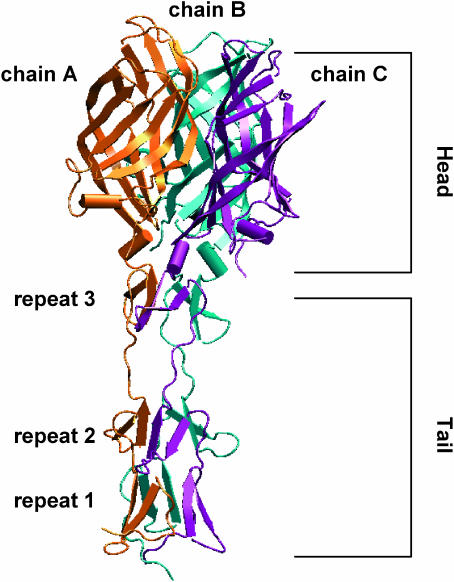

The crystal structure of a JAM1-binding fragment of σ1 revealed an elongated trimer with two domains: a compact head with a new β-barrel fold and a fibrous tail containing a triple β-spiral repeat (Chappell et al., 2002) (Fig. 1). The fibrous tail is primarily responsible for σ1 trimer formation (Leone et al., 1991, 1992), and it contains a highly flexible region that allows for significant movement between the tail and head (Fraser et al., 1990). The largest contact area of the head trimer interface is at the base of the β-barrel and involves a cluster of conserved residues (Chappell et al., 2002). This contact is unusual since it is centered on six buried aspartic acid side chains in a solvent-excluded environment. The nature of these interactions suggests that the head minimally contributes to the overall oligomeric stability of σ1 and perhaps even destabilizes the trimer. Based on these observations, σ1 was proposed to be a metastable structure capable of conformational changes upon viral attachment or cell entry (Chappell et al., 2002).

FIGURE 1.

Ribbon tracing of the crystallized C-terminal fragment of reovirus attachment protein σ1. Monomers A, B, and C of σ1 are shown in orange, cyan, and purple, respectively. Each monomer consists of a compact head domain and a fibrous tail. The different protein regions are annotated.

In this study, we used molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to investigate the conformational changes in σ1 structure. MD simulations have been widely applied to studies of dynamic features of macromolecules of biological interest, including proteins, nucleic acids, and membranes (Wang et al., 2001). Of particular interest for the current study, MD simulations have provided insights into the dynamic events that influence functional properties of biomolecules (Karplus and McCammon, 2002; Karplus and Petsko, 1990). Here, MD simulations were carried out to determine the protonation state of one of the buried aspartic acid residues at the σ1 head trimer interface, Asp345, and to study the influence of Asp345 in deprotonated and protonated states on the stability of the σ1 trimer. Electrostatic calculations using the finite difference Poisson-Boltzmann (FDPB) method were performed at physiologic conditions to further assess the biological relevance of the system in different protonation states. The FDPB method, which provides an accurate description of the full range of electrostatic interactions in macromolecules (Sharp and Honig, 1990), allowed us to estimate both the pKa values of Asp345 and the electrostatic free energies (ΔGE) of the trimerization process in different protonation states at Asp345.

Additional studies defined the extent of σ1 flexibility in solution and quantified the role of individual amino acids in conferring flexibility to the structure in a region just below the likely site of receptor engagement. Previous studies have demonstrated that σ1 possesses flexibility at several defined regions within its long, fiber-like tail (Fraser et al., 1990). Crystallographic analysis implicated residues 291–294 as one region of flexibility, although the observed movement was thought to be somewhat restricted by crystal-packing contacts. The MD simulations allowed us to investigate the conformational mobility associated with this σ1 “hinge” in a more physiologically relevant environment.

Our findings provide new insights about two unique properties of σ1 that are likely to mediate conformational movements, perhaps in response to receptor attachment or acid-dependent disassembly. Viral attachment and internalization are complex events that often depend on structural transitions of viral capsid proteins. Most data have been accumulated using enveloped viruses; however, little is known about how nonenveloped viruses, like reovirus, enter cells. Our study advances knowledge in this area by defining the properties of two important design features of σ1 that likely serve as the basis for structural transitions required for reovirus attachment and cell entry.

METHODS

MD simulations

The σ1 crystal structure solved at 2.6 Å resolution, including the crystallographic water molecules, was used as a starting model (Chappell et al., 2002) (PDB code 1KKE) (in total 615 amino acids). Hydrogen atoms were added with the Biopolymer module of the program suite SYBYL (Tripos, St. Louis MO), and their position was geometrically optimized. Two MD simulations were performed for 5 ns each to establish the correct protonation state of Asp345. In one simulation, Asp345 was protonated in all three monomers, whereas in the other this residue was deprotonated. Both trimers were immersed in a box with dimensions of 120 × 65 × 59 Å3, containing ∼12,500 water molecules. Six and nine K+ counterions were added to the solvent bulk of the protein/water complexes to maintain neutrality of the system. Water shells and counterions were first equilibrated for 30 ps at 300 K. This was followed by 5 ns of MD simulations in the NPT ensemble (constant temperature and pressure) using both sets of σ1 trimers. All-atom AMBER force field (Cornell et al., 1995) parameters were used for the protein and the K+ ions, whereas the TIP3P model (Jorgensen et al., 1983) was employed to explicitly represent water molecules. The systems were simulated in periodic boundary conditions. The van der Waals and short-range electrostatic interactions were estimated within an 8 Å cutoff, whereas the long-range electrostatic interactions were assessed by using the particle mesh Ewald method (Essmann et al., 1995) with ∼1 Å charge grid spacing interpolated by fourth-order B-spline and by setting the direct sum tolerance to 10−5. Bonds involving hydrogens were constrained by using the SHAKE algorithm (Ryckaert et al., 1977) with a relative geometric tolerance for coordinate resetting of 0.0001 Å. Berendsen's coupling algorithms were employed to maintain constant temperature and pressure (Berendsen et al., 1984) with the same scaling factor for both solvent and solutes and with the time constant for heat bath coupling maintained at 1.0 ps. The pressure for the isothermal-isobaric ensemble was regulated by using a pressure relaxation time of 1.0 ps in Berendsen's algorithm. The simulations of the solvated protein models were performed using constant pressures of 1 atm and constant temperature of 300 K. A time step of 1.5 fs was used in all simulations, which were carried out by using the AMBER 6.0 program suite (Case et al., 1999).

Electrostatic calculations

Electrostatic calculations were carried out using FDPB method as implemented in the DELPHI program (Honig and Nicholls, 1995). This method allows the solution of Poisson-Boltzmann equations in three dimensions, using a nonlinear form incorporating two different dielectric regions, ionic strength, and periodic and focusing boundary conditions utilizing stripped optimum successive over-relaxation and surface charge position. The coordinates of the trimers both fully protonated and fully ionized at Asp345, and the correspondent monomers with essential hydrogen atoms, were used as input for the calculations. The grid size was set to 65 points per dimension and the scale in grid/Å to 0.52 resulting in a box fill of 98–100%. United atom charges derived from the AMBER force field (Cornell et al., 1995) were used. The inner and outer dielectrics were set to 2 and 80, respectively. Ionic strength of the solvent was set to 0.145 M (i.e., the value at physiologic pH). Focusing boundary conditions were applied. The electrostatic free energies GE computed by DELPHI is equal to one-half the sum of the charge of each atom times the potential at each atom position:

|

(1) |

In Eq. 1,  is the external electrostatic potential and

is the external electrostatic potential and  is the potential arising from the particular grid mapping used. Since identical mappings were employed, the difference between the energies of two calculations erased this term.

is the potential arising from the particular grid mapping used. Since identical mappings were employed, the difference between the energies of two calculations erased this term.

The FDPB method also was used to calculate the pKa of the Asp345 both in the trimer and in the monomer, following the procedure proposed by Honig and co-workers (Yang et al., 1993). In this analysis, the “intrinsic” pKa of a single amino acid in a protein environment ( ) was calculated according to

) was calculated according to

|

(2) |

In Eq. 2,  is the standard pKa value of the titratable amino acid (e.g., 3.9 for the aspartic acid) and γ is −1 and +1 for an acidic or basic group, respectively. ΔΔ

is the standard pKa value of the titratable amino acid (e.g., 3.9 for the aspartic acid) and γ is −1 and +1 for an acidic or basic group, respectively. ΔΔ is the difference in electrostatic free energy of interaction of Asp345 with its protein environment in both deprotonated and protonated form. The electrostatic free energies (GE) for Asp345 both deprotonated and protonated either in water or in a protein environment were calculated according to Eq. 1.

is the difference in electrostatic free energy of interaction of Asp345 with its protein environment in both deprotonated and protonated form. The electrostatic free energies (GE) for Asp345 both deprotonated and protonated either in water or in a protein environment were calculated according to Eq. 1.

RESULTS

The protonation state of Asp345

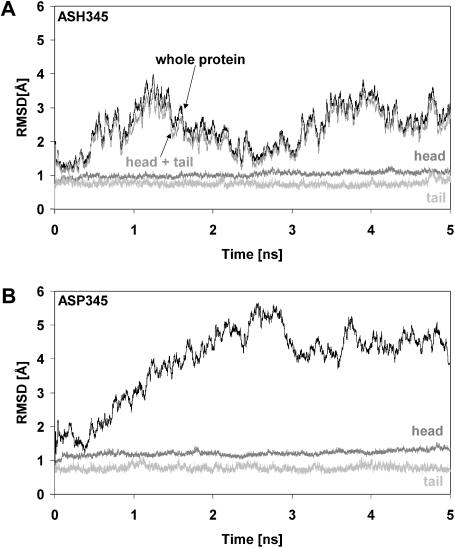

Two protocols of 5 ns each of MD simulations were performed using the recently determined x-ray structure of the reovirus attachment protein, σ1 (Chappell et al., 2002) (Fig. 1). One simulation was performed with protonated Asp345 (hereafter referred to as ASH345), and the other was carried out with negatively charged, deprotonated Asp345 (hereafter referred to as ASP345). The analyses of the root mean-square deviation (RMSD) values versus simulation time for both studies are shown in Fig. 2. RMSD values were calculated as the difference between the position of each backbone atom in the crystal structure and in every sampled configuration. The σ1 protein with ASH345 displayed conformational movements within intervals of both 1–2 ns and 3.5–4.5 ns (Fig. 2 A), indicating periodic dynamic motions of the protein. In contrast, the simulation with ASP345 showed a remarkably different behavior of σ1 (Fig. 2 B). In this case, the RMSD values increased during the entire simulation, stabilizing after ∼3.5 ns at ∼4.5 Å. Interestingly, despite such different dynamic behaviors, both the σ1 head and tail are stable in either protonation state. Further structural analyses demonstrated that, although the RMSD of the ASH345-based trimer was mainly due to rigid-body segmental motions of the σ1 head with respect to the tail (see below), accumulation of negative electrostatic energy within the Asp-rich region at the base of the σ1 head was mainly responsible for the RMSD profile of the ASP345-based complex (see below).

FIGURE 2.

RMSD values of σ1 backbone atoms. (A) RMSD values from the minimized crystallographic structure of backbone atoms (black) of σ1 simulated with protonated Asp345. The RMSD of the backbone atoms of σ1 head (dark shaded), tail (light shaded), and “head + tail” (shaded) are also shown, revealing that rigid-body segmental motions of the head with respect to the tail may be responsible for the overall dynamic behavior. (B) RMSD values from the minimized crystallographic structure of backbone atoms (black) of σ1 simulated with deprotonated Asp345. The RMSD of the backbone atoms of both the σ1 head (dark shaded) and tail (light shaded) are also shown.

We next evaluated the pKa values of Asp345 by means of electrostatic calculations carried out using the FDPB method and employing the procedure of Honig and co-workers (Yang et al., 1993). In the σ1 monomer, Asp345 displayed a pKa very similar to that of an aspartic acid in water (pKa = ∼3.9), whereas in the trimer, Asp345 displayed a pKa much higher than that of an arginine (the most basic amino acid) (pKa ≫ 12.5).

Although the plots shown in Fig. 2 and the pKa calculations clearly suggest that Asp345 is protonated in the σ1 crystal structure, this feature of σ1 was further confirmed by analyzing the RMSD values versus simulation time of all nonhydrogen atoms of Tyr313, Arg314, Asp345, Asp346, and Tyr347, which are the amino acids in the immediate vicinity of the solvent-excluded aspartate-rich region. As shown in Fig. 3 A, these residues were extremely stable with low RMSD values (∼0.5 Å) when σ1 was simulated with the neutral aspartic acid (ASH345, black). In contrast, the same atoms did not reach a stable conformation when the protein was simulated with the negatively charged aspartate (ASP345, shaded). Remarkably, the conformational mobility of these residues persisted despite the fact that the RMSD of the backbone atoms of the ASP345-based trimer stabilized at ∼4.5 Å after 3.5 ns of simulation (Fig. 2 B). Interestingly, in the case of ASH345-containing σ1, the conformational motion experienced by the protein within both the 1–2 ns and 3.5–4.5 ns intervals (Fig. 2 A) did not affect the atoms at the trimer interface. The σ1 trimer with ASH345 was conformationally far more stable than the trimer with ASP345 as also confirmed by inspection of two minimized MD snapshots after 5 ns of simulations. As shown in Fig. 3 B, the H-bond pattern between Asp345 and Asp346 was maintained during the simulation with ASH345, but this configuration was lost in the simulation with ASP345. This H-bond pattern avoids the accumulation of repelling negative charges at the base of the head trimer interface and indeed is the main reason for its conformational stability during the simulation with ASH345. Accordingly, loss of this H-bond pattern likely accounts for the mobility observed in the ASP345-containing trimer. Moreover, Tyr313 and Tyr347, which surround Asp345, contribute to such an electrostatic repulsion by means of the π-electron clouds of their aromatic rings. Thus, our MD simulations and pKa calculations clearly support the conclusion that Asp345 is protonated in the σ1 crystal structure.

FIGURE 3.

The protonation state of Asp345. (A) RMSD values from the minimized crystallographic structure of all nonhydrogen atoms of Tyr313, Arg314, Asp345, Asp346, and Tyr347 during the simulation with protonated (ASH345, black) and deprotonated (ASP345, shaded) Asp345. The dynamic behavior of these residues is strongly dependent on the protonation state of Asp345. (B) Asp345 and Asp346 residues as they appear interlinked in the trimer from a minimized snapshot at 5 ns of the MD simulation performed with ASH345 (protonated Asp345, left) and ASP345 (deprotonated Asp345, right). The hydrogen bond pattern (in red) that was observed in the crystal structure is only preserved during the simulation of σ1 with protonated Asp345 (ASH345, left).

We next investigated how the different protonation states of Asp345 affect stability of the σ1 trimer. For this analysis, we performed FDPB-based calculations using both the ASH345 and ASP345 models to compute the electrostatic free energies (ΔGE) of the trimer. FDPB-based calculations also were carried out using trimers with intermediate protonation states (one- and two-protonated Asp345 residues). The results of these calculations are shown in Table 1. Trimer stability is electrostatically substantially more favored in the fully protonated state (ASH345 model). It is noteworthy that all of the calculated ΔGE values are positive, suggesting that the crystallized trimeric σ1 structure is incompatible with deprotonated Asp345 side chains.

TABLE 1.

Differences in electrostatic free energies (GE) between the monomers (mono) and the trimer (tri) in different protonation states

| GE ASPtri | GE ASPmono | ΔGE ASP | GE ASH_Atri | GE ASH_Amono | ΔGE ASH_A | GE ASH_ABtri | GE ASH_ABmono | ΔGE ASH_AB | GE ASHtri | GE ASHmono | ΔGE ASH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8627 | 8086 | 541 (321) | 8501 | 8070 | 431 (255) | 8379 | 8065 | 314 (186) | 8287 | 8063 | 224 (133) |

ASP and ASH are the models of σ1 fully deprotonated and protonated, respectively. ASH_A is the model with protonated Asp345 of chain A. ASH_AB is the model with protonated Asp345 of chains A and B. The GE values are calculated according to Eq. 1. The energy values are in kT. The ΔGE values are in parentheses in kcal/mol.

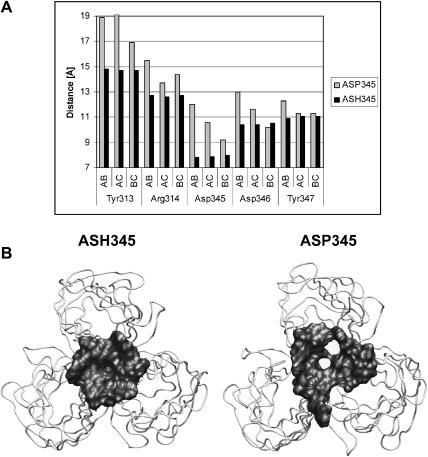

Further analyses focused on residues Tyr313, Arg314, Asp345, Asp346, and Tyr347, which are located at the base of the σ1 head and mediate intersubunit contacts between the three chains of the σ1 trimer. Moreover, the two tyrosine side chains form hydrophobic layers that sandwich Asp345. The interchain distances between two Cα of the same residue in the different chains were monitored during 5 ns of MD simulations. The average distances between the Cα carbons of Tyr313, Arg314, Asp345, Asp346, and Tyr347 of chains A, B, and C for both simulations are shown in Fig. 4 A. We found that deprotonation of Asp345 resulted in increased distances between the σ1 chains at the base of their heads, reaching deviations >4 Å from the x-ray structure for the analyzed residues. This movement allowed water molecules of the solvent bulk to access the Asp-rich region. In contrast, during the MD simulations with ASH345, the interchain distances did not show significant changes in comparison to those in the crystal structure, allowing a solvent-excluded environment adjacent to the Asp-rich region to be maintained. This finding was confirmed by analyzing the Connolly surface (Connolly, 1983) of the residues at the base of the heads. Two snapshots at the end of the MD simulations are shown in Fig. 4 B. These analyses indicate that during the simulation with ASH345 the tight H-bond pattern did not allow the heads to separate, although this occurred during the simulation with ASP345. We conclude that deprotonated Asp345 side chains are incompatible with the stable trimeric structure seen in the σ1 crystals. The Asp345 side chains must be protonated to allow for tight contacts between the head domains, and thus the trimeric σ1 must be formed under conditions in which Asp345 is protonated.

FIGURE 4.

Separation of the σ1 head. (A) Average interchain distances (AB, AC, BC) during 5 ns of MD simulations between Cα carbons of Tyr313, Arg314, Asp345, Asp346, and Tyr347 belonging to two different chains. The average distances calculated during 5 ns of MD simulations with protonated and deprotonated Asp345 are shown in black and shaded, respectively. The average distances calculated during the MD simulations using σ1 containing ASH345 (black) are similar to those observed in the crystal structure. (B) The σ1 head after 5 ns of MD simulations. The Connolly surface of the residues at the base of the head is shown (radius 1.4 Å). The σ1 heads appear to separate during the simulation with fully ionized Asp345-containing σ1. The Asp-rich region might trigger separation of the σ1 heads.

The molecular basis of σ1 flexibility

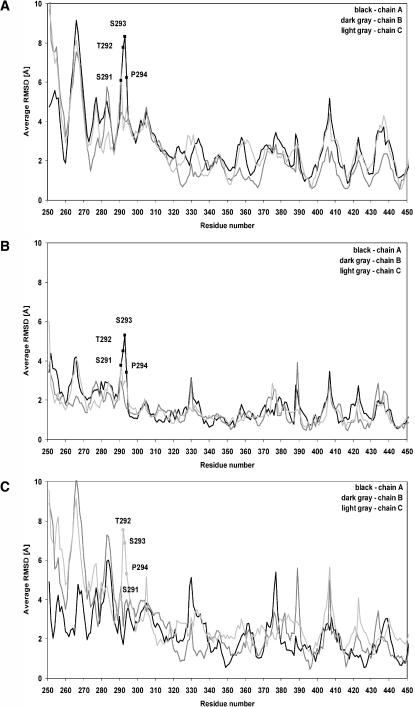

The molecular basis of σ1 flexibility was defined by analyzing the conformational movements of the protein during the MD simulations. Results reported thus far indicate that Asp345 is protonated in the σ1 crystal structure. Therefore, we used the neutral aspartic acid structure of σ1 (ASH345) for these studies. The plots shown in Fig. 2 A indicate that both the head and tail domains of σ1 are very stable during 5 ns of MD simulations (RMSD = ∼1 Å), whereas when analyzed together (plot “head + tail” of Fig. 2 A) the RMSD values of these domains show an oscillating behavior. Therefore, rigid-body segmental motions of the head with respect to the tail might be responsible for the RMSD values observed in the simulations with the ASH345-based trimer. To test this hypothesis, we first analyzed the mean RMSD values of the backbone atoms within simulation intervals in which the protein underwent significant conformational changes (1.0–2.0 ns, Fig. 5 A; 2.0–3.0 ns, Fig. 5 B; and 3.5–4.5 ns, Fig. 5 C). In this analysis, a segment comprising residues 291–294 was found to be one of the most flexible regions of the molecule. Amino acids Ser291–Pro294 have been previously suggested to be important for σ1 flexibility (Chappell et al., 2002). In particular, the crystal structure did not show any intra- or intermolecular contacts within the σ1 trimer for these residues, whose conformations were mostly determined by crystal-packing forces. These observations led to the suggestion that the observed movement of the σ1 head with respect to the base of the tail of almost 23° was mainly due to these amino acids (Chappell et al., 2002).

FIGURE 5.

RMSD values of all σ1 amino acids. (A) Average RMSD values of the backbone atoms of each amino acid from the minimized crystallographic structure within the simulation interval 1–2 ns. (B) Average RMSD values of the backbone atoms of each amino acid from the minimized crystallographic structure within the simulation interval 2–3 ns. (C) Average RMSD values of the backbone atoms of each amino acid from the minimized crystallographic structure within the simulation interval 3.5–4.5 ns.

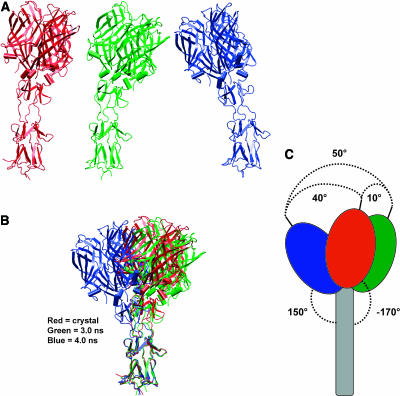

During the MD simulations, the side chains of Ser291, Thr292, and Ser293 interacted mainly with the solvent bulk. Furthermore, the observed high mean RMSD values for their backbone atoms indicate that this region of σ1 is highly flexible. To investigate how the flexibility of Ser291–Ser293 influences the movement of the head with respect to the tail, we defined the centers of mass (centroids) of the head, tail, and head-tail junction. The axes of both the head and tail were defined as the segments connecting the head centroid to the head-tail centroid, and the tail centroid to the head-tail centroid, respectively. We analyzed the oscillating movement of the head by sampling the angle between the axis of the head in the crystal structure and the axis of the head at every conformation throughout 5 ns of MD simulations. The movement detected between the crystal structure conformation (red in Fig. 6 A) and a conformation at 2.5 ns (green in Fig. 6 A) was ∼10° to the right; the movement was ∼40° to the left when the crystal structure conformation was compared to a conformation sampled at 4.0 ns (blue in Fig. 6 A). These conformations at 2.5 ns and 4.0 ns were those displaying the maximum displacement of the σ1 head with respect to its conformation in the crystal structure (Fig. 6 B). Therefore, the σ1 head underwent an oscillating motion as wide as ∼50° during 5 ns of MD simulations (Fig. 6 C). These results provide further support for the previously proposed conformational mobility of the σ1 head and suggest that the protein is capable of much wider movement in an aqueous environment than in the crystal (50° vs. 23°). In additional analyses, we investigated the bending down movement of the σ1 head, sampling the angle between the head and tail axes throughout 5 ns of MD simulations. We found that the maximum angle between the σ1 head and tail axes is ∼150°, as seen in a conformation sampled at ∼4.0 ns, whereas it had been detected at −170° in the crystal structure (Fig. 6 C). These results further suggest that σ1 undergoes substantial conformational changes in an aqueous environment.

FIGURE 6.

The basis of σ1 flexibility. (A) The σ1 crystal structure (red) and snapshots at 2.5 ns (green) and 4 ns (blue) from the ASH345-based MD simulation. (B) Superimposition of two snapshots representative of the overall protein dynamics onto the crystallographic structure of σ1. The three-dimensional alignment was accomplished by fitting the backbone atoms of amino acids (255–288) of the σ1 tail. (C) Schematic representation of the three superimposed structures. Angle values were defined by first estimating the centers of mass (centroids) of the protein head, tail, and head-tail junction. The axes of both head and tail were defined as the segments connecting the head centroid to the head-tail centroid, and from the tail centroid to the head-tail centroid, respectively. The oscillating movement was estimated as the angle between the head axis of two different snapshots (maximum value of ∼50° was calculated between a snapshot at 2.5 ns and a snapshot at 4 ns). The bending down movement of the head was defined as the angle between the head and tail axes (maximum calculated value ∼150°).

DISCUSSION

The structural changes that accompany reovirus attachment and cell entry, and the transition from the virion to subvirion intermediate and core particle, are poorly understood (Dryden et al., 1993). The σ1 protein likely plays a key role in these events as it facilitates viral attachment and undergoes major conformational changes during viral disassembly (Dryden et al., 1993; Furlong et al., 1988). During the disassembly process, proteolytic cleavage of reovirus outer-capsid protein σ3, which lies in close proximity to σ1 on the virion surface (Nason et al., 2001; Nibert et al., 1995), coincides with a change in σ1 from a retracted to an extended conformation (Dryden et al., 1993; Furlong et al., 1988; Nibert et al., 1995). It is likely that the two properties of σ1 studied here help mediate these conformational movements.

The role of Asp345

Mechanisms underlying the conformational changes in σ1 during reovirus attachment and disassembly are unknown. However, pH might be a driving force for these changes in σ1 conformation (Sturzenbecker et al., 1987; Wetzel et al., 1997), similar in some respects to the acid-dependent changes in the influenza-virus hemagglutinin (Bullough et al., 1994a,b). Therefore, it is possible that the protonation state of Asp345 plays an important role in σ1-mediated events during the initiation of reovirus replication. In the crystal structure, the Asp345 side chains cluster in a solvent-excluded area at the head trimer interface. Each Asp345 side chain in the σ1 monomer is within hydrogen-bond distance to its symmetry-mate, and it is also close to the neighboring Asp346 residue in the same monomer (Chappell et al., 2002). No counterion is present that might compensate for excess negative charges at the center of the trimer. Interestingly, both Asp345 and Asp346 are absolutely conserved among prototype strains of the three reovirus serotypes (Duncan et al., 1990; Nibert et al., 1990). We present clear evidence to show that σ1 must be protonated at all three Asp345 side chains to form a stable trimer with the interactions seen in the crystal structure. Introducing a charge at the Asp345 side chain leads to destabilization of the trimer and separation of the head domains. This result indicates that the trimeric structure of σ1 seen in the crystal must have been formed under conditions that allow Asp345 to be protonated. Conceivably, this process could involve a low pH environment or perhaps interactions with other proteins. Once assembled, the trimer is remarkably stable and resistant to proteases even at neutral pH (Chappell et al., 1998; Nibert et al., 1995), indicating that deprotonation of Asp345 cannot occur once the trimer is formed. This latter point is fully consistent with our observation that water molecules could not reach the Asp345 side chain from the outside throughout 5 ns of MD simulations with the ASH345-based trimer. Thus, the extended form of the σ1 trimer seen in the crystal structure appears to be the endpoint of a structural transition rather than the starting point for one. This model is in agreement with previous studies in which a more extended conformer of σ1 is observed at later stages of viral disassembly (Dryden et al., 1993; Furlong et al., 1988; Nibert et al., 1995). It also provides an explanation for the previously postulated σ1 transition from a retracted to a more extended state during the disassembly cascade (Dryden et al., 1993; Furlong et al., 1988; Nibert et al., 1995).

What might the starting point for σ1 look like? We think it likely that such a state would involve a partially detrimerized σ1 protein, in which the head domains (and perhaps also the β-spiral region) are separated from each other. We note that the σ1 head is thought to be in close proximity to the σ3 protein in the reovirus virion (Nason et al., 2001). Such an arrangement is difficult to reconcile with a fully extended structure of σ1 in which the head protrudes ∼380 Å from the capsid shell (Fraser et al., 1990; Furlong et al., 1988). Thus, the head domain may be folded back onto the virion surface. An event such as the engagement of a receptor, or a change in pH, or a combination of both might destabilize this retracted form of σ1 and favor the formation of the trimer seen in the crystal structure.

The role of σ1 flexibility

Our MD studies show that residues Ser291–Pro294 exhibit a high degree of flexibility, allowing dramatic movements of the σ1 head with respect to the tail. In an aqueous environment, the oscillating motion of the σ1 head with respect to the tail was as wide as 50° throughout 5 ns of MD simulations versus 23° observed in the crystal structure, where the flexibility was constrained by crystal-packing forces (Chappell et al., 2002). Flexibility of σ1 at this region was previously observed in electron micrographs of full-length σ1 (Fraser et al., 1990). Rotary shadowing experiments clearly show that the full-length σ1 trimer possesses several hinge regions, one of which is located near the head and likely identical to the one investigated here (Fraser et al., 1990). In the electron micrographs, the trimeric σ1 head bends from the trimer axis at this hinge to a degree similar to that seen in our studies. In both cases a similar maximal bending angle is observed, suggesting that the trimeric head is not capable of bending more than a certain degree (∼150°). The head is anchored to the spiral by three tightly interacting monomeric units, and these interactions probably limit the degree of conformational mobility at this site.

Flexibility of σ1 might be a fundamental requirement for viral attachment to the surface of host cells, as previously suggested for the adenovirus attachment protein, fiber, in which flexibility plays an important role in receptor selectivity and viral tropism (Chiu et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2003). Reovirus particles are relatively large, and the long fiber-like tail may be necessary to allow the head to reach its receptor JAM1, which contains two immunoglobulin-like domains (Prota et al., 2003) and thus is located in close proximity to the cell surface. Flexibility at a hinge region just below the σ1 head might facilitate engagement of this receptor by allowing the head to position itself properly for a productive interaction. We note that the flexible insertion between spiral repeats 2 and 3 of the crystallized σ1 fragment is shorter in T3D σ1 than in the prototype strains of the other two major reovirus serotypes (Chappell et al., 2002). Since reovirus serotypes differ strikingly in the capacity to infect discrete populations of cells in the murine central nervous system (Tyler et al., 1986; Weiner et al., 1977, 1980), this region of σ1 may influence reovirus pathogenesis.

Results reported here demonstrate that MD simulations within the molecular modeling framework are a powerful complement to x-ray diffraction (Huse and Kuriyan, 2002). Our findings support hypotheses that directly implicate a change in σ1 protonation during an early point in the reovirus infectious cycle. Based on these studies, it is now possible to design experiments to enhance an understanding of the role of head trimer stability in reovirus attachment and cell entry. Moreover, altering the flexibility of the hinge region (by elongating or shortening it) might correlate with changes in the efficiency of these early events in reovirus replication. Thus, our MD studies provide an experimental platform to define mechanisms underlying the conformational dynamics of σ1 during reovirus attachment and cell entry.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of our laboratories for helpful discussions. We thank C. D. Klein and J. Missimer for critical review of the manuscript.

We acknowledge support from Public Health Service awards AI45716 (T.S.), AI38296 (T.S.D.), and GM67853 (T.S. and T.S.D.), and the Elizabeth B. Lamb Center for Pediatric Research (T.S.D.).

Andrea E. Prota's current address is Paul Scherrer Institute, Biomolecular Research/Structural Biology 0FLC/103, CH-5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland.

References

- Barton, E. S., J. C. Forrest, J. L. Connolly, J. D. Chappell, Y. Liu, F. J. Schnell, A. Nusrat, C. A. Parkos, and T. S. Dermody. 2001. Junction adhesion molecule is a receptor for reovirus. Cell. 104:441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen, H. J. C., J. P. M. Postma, W. F. Van Gunsteren, A. Di Nola, and J. R. Haak. 1984. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- Bullough, P. A., F. M. Hughson, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1994a. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature. 371:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullough, P. A., F. M. Hughson, A. C. Treharne, R. W. Ruigrok, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1994b. Crystals of a fragment of influenza haemagglutinin in the low pH induced conformation. J. Mol. Biol. 236:1262–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case, D. A., D. A. Pearlman, J. W. Caldwell, T. E. Cheatham III, W. S. Ross, C. L. Simmerling, T. A. Darden, K. M. Merz, R. V. Stanton, J. J. Vincent, M. Crowley, D. M. Ferguson, R. J. Radmer, G. L. Seibel, U. C. Singh, P. K. Weiner, and P. A. Kollman. 1999. AMBER 6. University of California, San Francisco, CA.

- Chappell, J. D., E. S. Barton, T. H. Smith, G. S. Baer, D. T. Duong, M. L. Nibert, and T. S. Dermody. 1998. Cleavage susceptibility of reovirus attachment protein σ1 during proteolytic disassembly of virions is determined by a sequence polymorphism in the σ1 neck. J. Virol. 72:8205–8213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, J. D., J. L. Duong, B. W. Wright, and T. S. Dermody. 2000. Identification of carbohydrate-binding domains in the attachment proteins of type 1 and type 3 reoviruses. J. Virol. 74:8472–8479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, J. D., A. E. Prota, T. S. Dermody, and T. Stehle. 2002. Crystal structure of reovirus attachment protein σ1 reveals evolutionary relationship to adenovirus fiber. EMBO J. 21:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C. Y., E. Wu, S. L. Brown, D. J. Von Seggern, G. R. Nemerow, and P. L. Stewart. 2001. Structural analysis of a fiber-pseudotyped adenovirus with ocular tropism suggests differential modes of cell receptor interactions. J. Virol. 75:5375–5380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, M. L. 1983. Solvent-accessible surfaces of proteins and nucleic acids. Science. 221:709–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, W. D., P. Cieplak, C. I. Bayly, I. R. Gould, K. M. Merz, D. M. Ferguson, D. C. Spellmeyer, T. Fox, J. W. Caldwell, and P. A. Kollman. 1995. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117:5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- Dryden, K. A., G. Wang, M. Yeager, M. L. Nibert, K. M. Coombs, D. B. Furlong, B. N. Fields, and T. S. Baker. 1993. Early steps in reovirus infection are associated with dramatic changes in supramolecular structure and protein conformation: analysis of virions and subviral particles by cryoelectron microscopy and image reconstruction. J. Cell Biol. 122:1023–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, R., D. Horne, L. W. Cashdollar, W. K. Joklik, and P. W. Lee. 1990. Identification of conserved domains in the cell attachment proteins of the three serotypes of reovirus. Virology. 174:399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essmann, U., L. Perera, M. L. Berkowitz, T. Darden, H. Lee, and L. G. Pedersen. 1995. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, R. D., D. B. Furlong, B. L. Trus, M. L. Nibert, B. N. Fields, and A. C. Steven. 1990. Molecular structure of the cell-attachment protein of reovirus: correlation of computer-processed electron micrographs with sequence-based predictions. J. Virol. 64:2990–3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, D. B., M. L. Nibert, and B. N. Fields. 1988. Sigma1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J. Virol. 62:246–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honig, B., and A. Nicholls. 1995. Classical electrostatics in biology and chemistry. Science. 268:1144–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse, M., and J. Kuriyan. 2002. The conformational plasticity of protein kinases. Cell. 109:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, W. L., J. Chandrasekhar, J. D. Madura, R. W. Impey, and L. M. Klein. 1983. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- Karplus, M., and A. McCammon. 2002. Molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:646–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus, M., and G. A. Petsko. 1990. Molecular dynamics simulations in biology. Nature. 347:631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone, G., R. Duncan, D. C. Mah, A. Price, L. W. Cashdollar, and P. W. Lee. 1991. The N-terminal heptad repeat region of reovirus cell attachment protein σ1 is responsible for σ1 oligomer stability and possesses intrinsic oligomerization function. Virology. 182:336–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone, G., L. Maybaum, and P. W. Lee. 1992. The reovirus cell attachment protein possesses two independently active trimerization domains: basis of dominant negative effects. Cell. 71:479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liemann, S., K. Chandran, T. S. Baker, M. L. Nibert, and S. C. Harrison. 2002. Structure of the reovirus membrane-penetration protein, Mu1, in a complex with is protector protein, σ3. Cell. 108:283–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nason, E. L., J. D. Wetzel, S. K. Mukherjee, E. S. Barton, B. V. Prasad, and T. S. Dermody. 2001. A monoclonal antibody specific for reovirus outer-capsid protein σ3 inhibits σ1-mediated hemagglutination by steric hindrance. J. Virol. 75:6625–6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibert, M. L., J. D. Chappell, and T. S. Dermody. 1995. Infectious subvirion particles of reovirus type 3 Dearing exhibit a loss in infectivity and contain a cleaved σ1 protein. J. Virol. 69:5057–5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibert, M. L., T. S. Dermody, and B. N. Fields. 1990. Structure of the reovirus cell-attachment protein: a model for the domain organization of σ1. J. Virol. 64:2976–2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olland, A. M., J. Jane-Valbuena, L. A. Schiff, M. L. Nibert, and S. C. Harrison. 2001. Structure of the reovirus outer capsid and dsRNA-binding protein σ3 at 1.8 Å resolution. EMBO J. 20:979–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prota, A. E., J. A. Campbell, P. Schelling, J. C. Forrest, M. J. Watson, T. R. Peters, M. Aurrand-Lions, B. A. Imhof, T. S. Dermody, and T. Stehle. 2003. Crystal structure of human junctional adhesion molecule 1: implications for reovirus binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:5366–5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinisch, K. M., M. L. Nibert, and S. C. Harrison. 2000. Structure of the reovirus core at 3.6 Å resolution. Nature. 404:960–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckaert, J. P., G. Ciccotti, and H. J. C. Berendsen. 1977. Numerical integration of the Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, K. A., and B. Honig. 1990. Electrostatic interactions in macromolecules: theory and applications. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 19:301–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturzenbecker, L. J., M. Nibert, D. Furlong, and B. N. Fields. 1987. Intracellular digestion of reovirus particles requires a low pH and is an essential step in the viral infectious cycle. J. Virol. 61:2351–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, K. L. 2001. Mammalian reoviruses. In Fields Virology, 4th ed. D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley, editors. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, PA. 1729–1945.

- Tyler, K. L., D. A. McPhee, and B. N. Fields. 1986. Distinct pathways of viral spread in the host determined by reovirus S1 gene segment. Science. 233:770–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W., O. Donini, C. M. Reyes, and P. A. Kollman. 2001. Biomolecular simulations: recent developments in force fields, simulations of enzyme catalysis, protein-ligand, protein-protein, and protein-nucleic acid noncovalent interactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 30:211–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, H. L., D. Drayna, D. R. Averill, Jr., and B. N. Fields. 1977. Molecular basis of reovirus virulence: role of the S1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 74:5744–5748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, H. L., M. L. Powers, and B. N. Fields. 1980. Absolute linkage of virulence and central nervous system cell tropism of reoviruses to viral hemagglutinin. J. Infect. Dis. 141:609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel, J. D., G. J. Wilson, G. S. Baer, L. R. Dunnigan, J. P. Wright, D. S. Tang, and T. S. Dermody. 1997. Reovirus variants selected during persistent infections of L cells contain mutations in the viral S1 and S4 genes and are altered in viral disassembly. J. Virol. 71:1362–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, E., L. Pache, D. J. Von Seggern, T. M. Mullen, Y. Mikyas, P. L. Stewart, and G. R. Nemerow. 2003. Flexibility of the adenovirus fiber is required for efficient receptor interaction. J. Virol. 77:7225–7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, A. S., M. R. Gunner, R. Sampogna, K. Sharp, and B. Honig. 1993. On the calculation of pKas in proteins. Proteins. 15:252–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]