Abstract

With discovery of the protein prestin and the gathering evidence linking it to outer hair cell electromotility, the working mechanism of outer hair cells is becoming clearer. Recent experiments have established the voltage-dependent stiffness of outer hair cells and given an insight into the nature of variation of stiffness with respect to voltage. These and earlier experiments are used to analyze and develop models of outer hair cell response. In this article, recent modeling efforts have been reconciled and placed into a common mechanics-based framework. The constitutive models are analyzed with regard to their capability to replicate experimental results. We extend the area motor model to include elastic constants dependent on motor state. The modified model successfully captures stiffness variations of outer hair cells and capacitance changes with respect to voltage.

INTRODUCTION

The discovery of the electromotile response of outer hair cells (OHCs) by Brownell et al. (1985) has spawned research into determining the precise nature in which the OHCs participate in the hearing process. To this end, many studies have been undertaken to quantify the transduction process, experimental and theoretical. OHCs have been observed to have voltage and stress-dependent capacitance (Ashmore, 1990; Santos-Sacchi, 1991; Iwasa, 1993; Kakehata and Santos-Sacchi, 1995), voltage-dependent stiffness (He and Dallos, 2000), and have shown voltage-dependent length changes (Brownell et al., 1985; Ashmore, 1987; Santos-Sacchi and Dilger, 1988).

In vitro experiments have established four important characteristics of OHC behavior, which we recount here. First, the capacitance varies like a bell-shaped function with respect to changes in the transmembrane voltage (Ashmore, 1990; Santos-Sacchi, 1991). Turgor pressure (Kakehata and Santos-Sacchi, 1995), temperature (Santos-Sacchi and Huang, 1998), and chemicals (e.g., Shehata et al., 1991; Santos-Sacchi et al., 2001b) are all found to shift the capacitance versus voltage curves along the voltage axis and also influence the shape of the nonlinear capacitance-voltage relation. Second, the length of OHC changes with transmembrane voltage change. The axial strain varies according to a Boltzmann-type function with respect to voltage. The OHC elongates when hyperpolarized and shortens when depolarized (Brownell et al., 1985; Ashmore, 1987; Santos-Sacchi and Dilger, 1988). A third characteristic that has been recently brought to the fore is the voltage dependence of the stiffness. Experiments indicate that the stiffness also varies according to a Boltzmann-type function with respect to voltage. He and Dallos (2000) have shown that electrically evoked stiffness and length changes have very similar characteristics. A fourth and much less-studied characteristic is the nonlinear dynamic behavior of the OHC. OHCs when excited simultaneously by mechanical and electrical stimulus show response at the sum and difference frequencies. However no measurable harmonics of the mechanical forcing frequency are seen for simultaneous mechanical and electrical stimulus or even for pure mechanical stimulus (He and Dallos, 1999, 2000). This suggests that stiffness is dependent more strongly on the transmembrane voltage rather than the stresses in the membrane.

Unfortunately there is no single data set that shows all the above-mentioned results from the same outer hair cell. In vivo cochlear experimental results demonstrate that positive current (from scala vestibuli to scala tympani) is consistent with hyperpolarization with an attendant upward shift in the best frequency at a given measurement location. A negative current is consistent with depolarization accompanied by a downward shift in best frequency (Parthasarathi et al., 2003). These results indicate that OHC sensitivity to electrical and mechanical resting conditions seen in vitro are also important in vivo.

In this article we investigate the ability of mathematical models of OHCs to predict experimentally observed behavior. In particular, we focus on models based on the hypothesis that there exist motor proteins in the plasma membrane that undergo conformational changes. A two-state motor model is extended to include state-dependent elastic moduli. The modified model shows the correct stiffness and dynamic behavior. Effects of turgor pressure and temperature on capacitance are discussed.

ACTIVE TISSUE MODELS

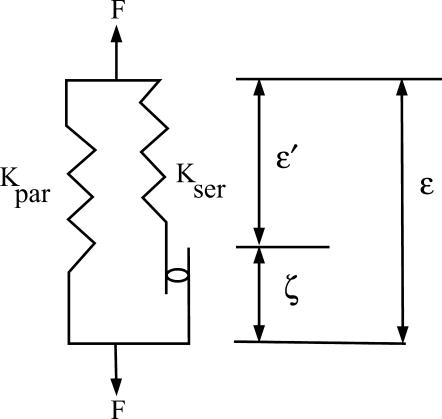

It is now generally accepted that there is a motor molecule located in the lateral membrane of the OHC that responds to electrical and mechanical stimulation in a coupled fashion. We consider an active tissue model related to Hill's model (from muscle mechanics). The schematic for the unit cell is given in Fig. 1, where ɛ is the “measurable” strain, ɛ′ is the elastic strain in the series connection, and ζ is the active strain. Experimental data for stiffness versus voltage for an OHC (He and Dallos, 2000) shows a large change in stiffness as voltage is changed. To focus on the effect of the active element of the OHC, we consider a simplifying approximation that KPAR = 0, which can be relaxed to account for a more general case. With this assumption, the constitutive law for the individual unit cell takes the form

|

(1) |

FIGURE 1.

Hill's model for activity. For OHC mechanics, Kpar is taken as zero (presently). The active displacement ζ may be a function of voltage or a state variable. The key element of activity is the precise dependence of ζ on the other field variables.

The active strain can be considered as a function of either voltage, voltage and strain, a state variable (like the probability function in a two-state model), or the strain rate (especially for skeletal muscle). In addition, the elastic moduli may also be functions of the voltage or the state variable.

In our characterization of OHC activity, we also decompose the charge transfer into an active and passive component to account for the nonlinear charge observed in experiments. From the high degree of correlation seen between the electrical and mechanical behavior of OHC it seems reasonable to assume that the two effects are coupled. Hence the active charge is considered to have dependencies similar to the active strain. These micromechanical laws can then be homogenized into a macroscopic free-energy function using this simple analogy as the building block for the laws.

Next, we categorize various possibilities for OHC constitutive models as a prequel to a discussion of their ability to replicate experimental results. Define Law 1 to represent a voltage-dependent active strain with linear elasticity (e.g., Spector et al., 2001; Tolomeo and Steele, 1995). Subsumed in this law is linear piezoelectricity. Let Law 2 include models that possess a voltage-dependent stiffness modification to Law 1. This law is the generalization of the notion put forth by He and Dallos (1999) for isolated OHCs. Denote as Law 3 those that represent a two-state motor probability for activity plus linear elasticity (Iwasa and Adachi, 1997) (the area motor model). A transmembrane protein is assumed to possess two conformal states (a short or a long state). The electromotility of the cells is a function of the state probability, which couples the electrical and mechanical field variables. This model is very attractive because there are few “free” parameters. Further, the hypothesis underlying this model is directly testable (the parameters can be determined through a static test and verified via a dynamic simulation for instance). Finally, we define Law 4 as a modified area motor model with a two-state motor probability plus a probability-dependent nonlinear elastic moduli; i.e., it is proposed here that the elastic constants themselves also depend on the state of the motor. Next, the ability of these various approaches to model the OHC electromechanical behavior is explored via a specific model problem that mimics those used in in vitro experiments.

MODEL PROBLEM AND THEORETICAL RESULTS

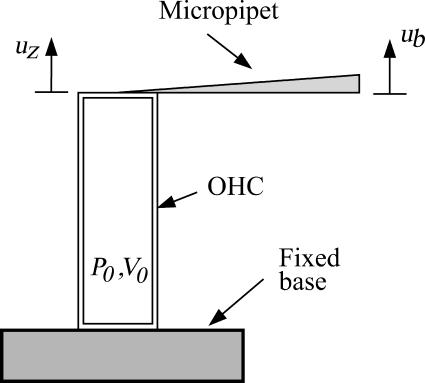

The model problem consists of a simplified model of the patch-clamp or micropipette experiment as pictured in Fig. 2. The shell (OHC) is assumed to be long compared to its diameter. The applied loads are considered axisymmetric and it is assumed that the principal axis of the material properties coincides with the cylindrical coordinates. The equilibrium relations for the OHC can then be written as:

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

where  , σzz is the stress in the axial direction, σθθ is the stress in the circumferential direction, r is the shell radius, h is the shell thickness, p is the internal fluid pressure, Text is the external load, and

, σzz is the stress in the axial direction, σθθ is the stress in the circumferential direction, r is the shell radius, h is the shell thickness, p is the internal fluid pressure, Text is the external load, and  ,

,  are the active forces in the axial and circumferential directions, respectively.

are the active forces in the axial and circumferential directions, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

OHC experiment, initially pressurized, stimulated by applied voltage about the resting potential. Mechanical loading is achieved through a micropipette (modeled as a linear spring) or an externally applied force.

In a manner similar to our decomposition of the strain field, the charge, Q, is decomposed as

|

(4) |

where Q is the total charge across the membrane per unit surface area, Q′ is the charge across the membrane per unit surface area due to the linear capacitance, and Q̃ is the active charge across the membrane per unit surface area.

These active elements are functions of only voltage in constitutive Laws 1 and 2, so that if the voltage is fixed, then the level of activity and stiffness is set. In Laws 3 and 4 the electrical and mechanical behavior are coupled through the probability function and we have

|

(5) |

where Pe is the probability that the motor is in the extended state. The probability is given by the Boltzmann probability density function

|

(6) |

where ΔF(V, Tz, Tc) is the difference in Gibbs free energy between the two states (long and short), and kBθ is the Boltzmann constant times the temperature. For Law 3, fz, fc, and Qq are functions of the material properties, density of motor proteins, and the area change that occurs when the motor flips state (in other words, these terms are constants). For Law 4, fz and fc also depend on Pe.

After the initial turgor pressure is applied, the deformation is assumed to be incompressible and the following constraint ɛz + 2ɛc = εvol is applied. Here εvol is a constant computed from the quasistatic problem for a given resting potential and turgor pressure (see Appendix A). Using this constraint we can solve Eqs. 2 and 3 to yield

|

(7) |

where  is the nominal shell stiffness. The whole-cell axial stiffness is given by

is the nominal shell stiffness. The whole-cell axial stiffness is given by  which can be obtained by differentiating Eq. 7 with respect to ɛz.

which can be obtained by differentiating Eq. 7 with respect to ɛz.

From Eq. 7 we can see that for Law 1 the axial stiffness is constant with changes in voltage. Law 2 can correctly predict the stiffness behavior because of the voltage-dependent stiffness, Kc. However, neither Law 1 nor Law 2 can explain shifting of capacitance versus transmembrane voltage curves when the external load or turgor pressure is altered because changing the mechanical operating point does not affect the electrical operating point in these models. Therefore, constitutive laws that do not explicitly couple the strains and voltage will not be able to replicate the experimental data, except by fitting with new parameters for every new operating condition. Laws 3 and 4 are more promising with regard to replicating experimental findings on the electromechanical coupling as the electrical and mechanical states are linked through the probability function.

AREA MOTOR MODEL

The underlying assumption of the area motor model is the existence of a motor protein in the plasma membrane that flips between two states (extended and contracted configuration). The flipping between two configurations is accompanied by some charge transfer “q” across the protein wall as well as a change in the resting length of the material. The charge transfer is believed to be a chloride ion or some anion moving across the motor protein (Oliver et al., 2001). Because it cannot travel the entire distance across the cell wall (or it would leave the cell), this charge is usually set to be less than one electron charge. If “q” is greater than one, then that is equivalent to two or more anions traveling part of the distance. The probability that a motor will flip state is governed by a Boltzmann function given by Eq. 6. The argument of the Boltzmann function is the jump in the Gibbs free energy considering the material to be completely in one state or the other (Achenbach et al., 1986). Because we are studying an experiment where the dependencies on stress and voltage are controlled, it makes sense to use the Gibbs free energy (a function of stress and voltage). Note that in this model, we are assuming that the density of states is reached instantaneously (i.e., there is no rate dependence in the switching of states). This simplifies the analysis (because the evolution of the states need not be computed) and is justified by the high-frequency response of the OHCs (Frank et al., 1999).

For the area motor model, where the stiffness is not state dependent, the jump in Gibbs free energy is

|

(8) |

where F0 is a constant that sets the zero point of the free-energy function (or the energy difference between long and short state when voltage and stresses are zero), q is the charge that transfers during change of state, az and ac are the anisotropic area changes from the shortened to the extended state. More details can be found in (Iwasa, 1993; Iwasa and Adachi, 1997).

We assume that the probability of states is translated directly into the density of proteins in each state. Further assuming that the proteins are uniformly distributed in the OHC wall the total strains can then be written as

|

(9) |

where n is the motor density of proteins per unit area. The transmembrane charge transfer must also be considered. The total charge transfer across the OHC wall per unit area is

|

(10) |

where Q′ is the passive charge transfer and nqPe represents the active charge transfer.

Equations 2 and 3 can now be written as

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

|

(13) |

A Gibbs free-energy function can be derived for this model. Let G be the free-energy function such that

|

(14) |

Using Eqs. 8–13 we can integrate expressions given in Eq. 14 to get

|

(15) |

where  and G0 is a constant. By construction, this free-energy function will satisfy conservation of energy and we have thermodynamic consistency of the formulation. The resulting relations also satisfy reciprocity because there exists a potential function of state from which they can be derived. We assume that the elastic and electric processes involved are reversible and do not involve any dissipation. These constitutive laws will be revisited if data are presented that show significant losses or hysteretic effects.

and G0 is a constant. By construction, this free-energy function will satisfy conservation of energy and we have thermodynamic consistency of the formulation. The resulting relations also satisfy reciprocity because there exists a potential function of state from which they can be derived. We assume that the elastic and electric processes involved are reversible and do not involve any dissipation. These constitutive laws will be revisited if data are presented that show significant losses or hysteretic effects.

Capacitance

The capacitance per unit area is given by,

|

(16) |

The capacitance of the entire cell is given by Cohc = C ×Area. If we include the area change due to deformation, the total capacitance will be

|

(17) |

where R and L are the original radius and length of the cell (i.e., when strains are zero).

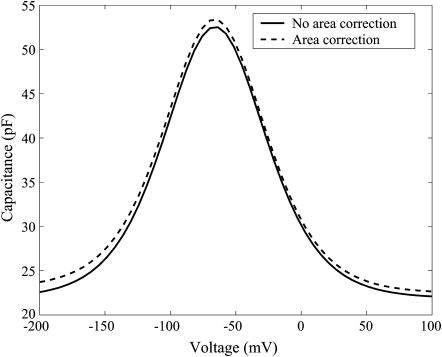

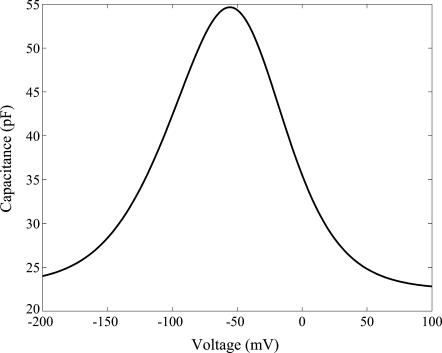

In Fig. 3 the dependence of capacitance on voltage with and without the contribution of the area change to capacitance. The effect of area change is typically second order and may be neglected. However, we include it in our calculations as per Eq. 17.

FIGURE 3.

Capacitance versus voltage for a turgor pressure of 0.5 kPa and resting voltage ∼−65 mV. The parameter values are listed in Appendix B.

The expression for capacitance shows that the maximum possible capacitance and nature of change of capacitance versus the transmembrane voltage is only influenced by the area change of the OHC and the temperature because other variables are constant. Their effects, however, are second order and hence the area motor model cannot account for the change in the maximum capacitance and change in shape of the capacitance curve when turgor pressure or temperature is changed.

Stiffness

For the area motor model  and

and  From Eq. 7 we get

From Eq. 7 we get

|

(18) |

Differentiating Eq. 18 with respect to ɛz we get,

|

(19) |

where

|

and

|

The stiffness is given by

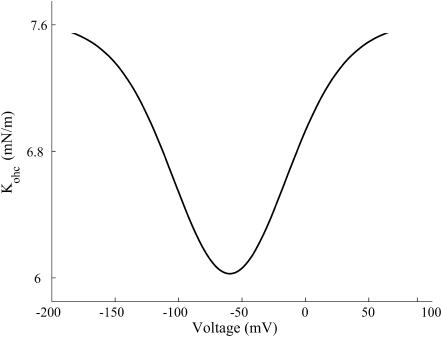

|

(20) |

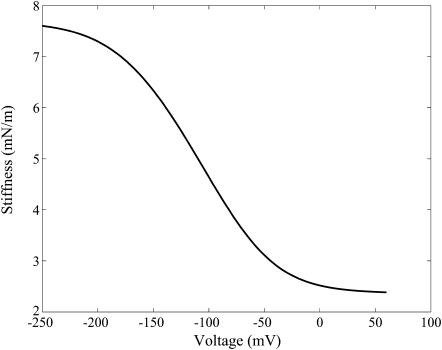

The stiffness versus voltage variation for the area motor model (see Fig. 4) is different from what has been observed in experiments (He and Dallos, 2000). The area motor model predicts that the axial stiffness at extreme hyperpolarized and depolarized states will asymptote to the same values whereas experimental results indicate that OHCs have maximum axial stiffness when hyperpolarized and minimum axial stiffness when depolarized about the resting state. Experimentally measured variation of stiffness versus voltage is similar to electromotility of the cell with an asymptotic maximum stiffness at extreme hyperpolarization and an asymptotic minimum at extreme depolarization. This suggests that the voltage dependence of stiffness is quite likely through the motor probability.

FIGURE 4.

Stiffness versus voltage for a turgor pressure of 0.5 kPa and resting voltage ∼−65 mV. The parameter values are listed in Appendix B.

Dynamic simulations

Dynamic simulations were performed for conditions similar to the experiments of He and Dallos (1999) (see Fig. 2). The boundary conditions for the model were as follows. One end of the OHC was held fixed whereas the other was attached to a spring, which simulated contact with a micropipette. The base of the micropipette was oscillated at a sinusoidal frequency, fB with amplitude Bamp. The transmembrane voltage was simultaneously excited at a different frequency, fV with amplitude Vamp. The micropipette (spring) was preloaded to simulate the preloading in the experiment, by an amount B0.

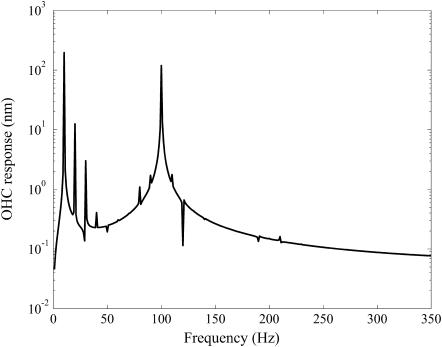

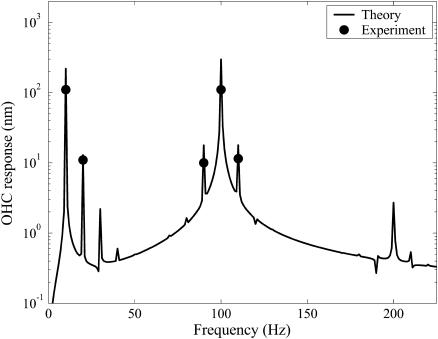

In Fig. 5, a representative result from the dynamic simulations is shown for fB = 100 Hz and fV = 10 Hz. The results do not compare well with experimental results. The main discrepancy lies in the sum and difference tones about the primary mechanical excitation frequency. The responses at 90 Hz and 110 Hz are negligible, whereas in the experiments the responses at those frequencies were pronounced. A wide range of parameter settings were tried, as some of the experimental conditions were not exactly known. None of the conditions yielded significant sum and difference tones. The reason that these difference tones are not generated is the small change in the stiffness predicted by this model (see Fig. 4). It is the product of the voltage-sensitive stiffness and the velocity that generates these distortion products.

FIGURE 5.

Frequency spectrum of ɛz versus time. OHC preload was 1 μm. Voltage amplitude was Vamp = 40 mV varied about −70 mV, fV = 10 Hz. Bamp = 1 μm and fB = 100 Hz. Probe stiffness was 4.73 mN/m. Other parameter values are listed in Appendix B. Note that response at 90 and 110 Hz is almost nonexistent.

MODIFIED AREA MOTOR MODEL

The area motor model does not replicate stiffness changes with respect to voltage seen experimentally. The stiffness experiments suggest that the motor is stiffer in the long state than in the short state. Next, a model where the elastic coefficients in the two states are different is developed. The total strain is expressed as a sum of strains due to motors in the short state, motors in the long state, and the active strain in the following manner:

|

(21) |

|

(22) |

where ( ) and (

) and ( ) are the compliance coefficients in the short and long state, respectively. The values of the compliance coefficients in the short and long state are computed from the respective values of elastic coefficients in the short and long state (see Appendix C). The expression for the total charge remains the same, i.e.,

) are the compliance coefficients in the short and long state, respectively. The values of the compliance coefficients in the short and long state are computed from the respective values of elastic coefficients in the short and long state (see Appendix C). The expression for the total charge remains the same, i.e.,

|

(23) |

The Gibbs energy barrier that governs the probability of switching state is now more complicated than in Eq. 8 because of the different elastic coefficients in the two states. The change in Gibbs free energy when motor jumps from short to long state is

|

(24) |

where ψ is the Helmholtz free energy (there is a jump in the Helmholtz free energy in this case because of the stiffness difference between long and short states). All Δ quantities represent the change from short to long state. The compliance coefficients for one motor protein can be written as the value of coefficients for a unit area divided by the number of proteins in a unit area. We can then write,

|

(25) |

|

(26) |

|

(27) |

|

(28) |

|

(29) |

As in the earlier model, the probability of being in the extended state is

|

(30) |

Because there is no dissipation in this model, we must be able to derive a thermodynamic potential function from which the strains and charges can be found (e.g.,  ). Again to ensure thermodynamic consistency, Eqs. 21, 22, and 23 are integrated with respect to Tz, Tc, and V, respectively, to obtain the Gibbs free-energy function for the modified area motor model

). Again to ensure thermodynamic consistency, Eqs. 21, 22, and 23 are integrated with respect to Tz, Tc, and V, respectively, to obtain the Gibbs free-energy function for the modified area motor model

|

(31) |

where G0 is a constant of integration. This ensures the consistency and reciprocity of this formulation.

The following sections show model predictions for capacitance, stiffness, electromotility, and dynamic response of OHCs. All results are for the same set of parameters (listed in Appendix B). A resting voltage of −55 mV was selected to match the resting voltage observed by He and Dallos (1999) in their stiffness experiments. The maximum and minimum stiffness values published for a certain hair cell by He and Dallos (2000) and the values for elastic coefficients published by Iwasa (2001) were used as a guide in selecting the elastic coefficients in the short and long state (see Appendixes B and C).

Capacitance

The expression for capacitance of the cell remains the same as in Eq. 16. The energy barrier is different in this model and so the capacitance is different from the area motor model. However, the capacitance results for the modified area motor model, shown in Fig. 6, are quite similar to that of the area motor model (see Fig. 3).

FIGURE 6.

Capacitance versus voltage for the modified area motor model. Vrest = −55 mV, turgor pressure = 0.2 kPa. Other parameter values are listed in Appendix B.

Stiffness and electromotility for modified area motor model

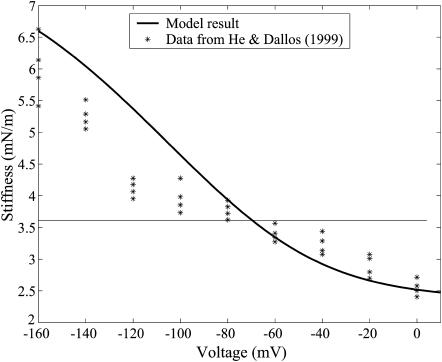

The axial force on the OHC is a sum of the externally applied axial force and the axial force contribution from the turgor pressure. Differentiating this relation with respect to ɛz and using Eqs. 21, 22, 23, and the incompressibility constraint ɛz + 2ɛc = ɛvol, the expression for whole-cell axial OHC stiffness can be derived (it is quite lengthy and not reproduced here). The stiffness-voltage relation for the same set of parameters as in Fig. 6 is shown in Fig. 7. Here the stiffness is seen to have the same qualitative behavior as in experiments, either patch clamp (He and Dallos, 1999; see Fig. 8) or microchamber (He and Dallos, 2000). Unfortunately the effective transmembrane voltage is not known in microchamber experiments, which precludes any quantitative comparison of the microchamber experiments with model predictions. The limiting values, slopes, and other features of the predictions are influenced significantly by the values we choose for the elastic constants. However, there are wide ranges of these parameters that give characteristic curves of the shape shown in Fig. 7. This shows that a model of a motor protein that has a state-dependent anisotropic stiffness does replicate experimental patterns for the axial stiffness change.

FIGURE 7.

Stiffness versus voltage for modified area motor model. Material parameters are the same as those used for Fig. 6. Results are for free extension of the cell.

FIGURE 8.

Stiffness prediction of modified area motor model using parameters from Fig. 7 compared against data from He and Dallos (1999). The simulation and experimental data use a resting voltage (≈−55 mV). Other parameters are fitted from the data from different experiments (He and Dallos, 2000).

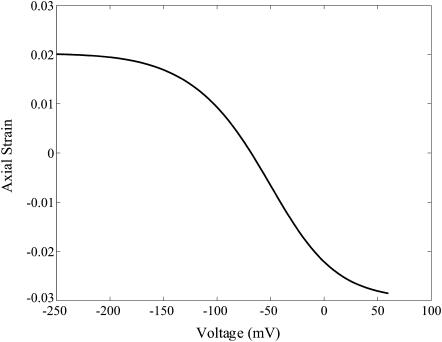

Fig. 9 shows the free electromotility prediction for the modified model. The electromotile behavior is similar, although not identical, to the stiffness behavior versus voltage as is seen in experiments (He and Dallos, 2000). The electromotility, too, is influenced by the values we choose for the elastic constants.

FIGURE 9.

Axial strain versus voltage plotted using the same material parameters as in Fig. 6. These results are for free extension of the cell.

Dynamic simulations

In Fig. 10, results for the frequency response predicted using the modified model are shown using the same conditions as for the area motor model (see Fig. 5). The response predicted by the modified model at sum and difference tones around fB is pronounced, closely matching experimental results (Fig. 3 F from He and Dallos, 2000) for the same set of mechanical and electrical excitation frequencies. A characteristic noticed in experiments is the absence of harmonics of the probe frequency (fB). In this mathematical model the stiffness depends on Pe, so the stiffness depends on the strains also. This means that harmonics of the fundamental will be generated for mechanical excitation. In Fig. 10 we can see a peak at 200 Hz, which is the first harmonic of the mechanical excitation frequency. However, note that the amplitude is very low, below the noise floor of measurements, estimated to be ∼5 nm for this experimental data set. Further investigations on the model response to pure mechanical excitation alone also showed a very low amplitude mechanical harmonic. These results agree with the experimental findings that the OHC stiffness is weakly nonlinear with respect to mechanical strain but more strongly nonlinear with respect to voltage.

FIGURE 10.

Frequency spectrum of ɛz versus time as predicted by the modified area motor model using fV = 10 Hz, fB = 100 Hz. OHC preload was 1 μm. Voltage amplitude was Vamp = 40 mV varied about −70 mV, Bamp = 1 μm. Probe stiffness was 4.73 mN/m. Other parameter values are the same as those used for Fig. 6. Results are compared with the experimental results of He and Dallos (2000).

Effect of turgor and temperature

Experiments have shown that the capacitance versus transmembrane voltage curve shifts along the voltage axis and sharpens or flattens with change in maximum capacitance when turgor pressure is changed (Kakehata and Santos-Sacchi, 1995), and when temperature is changed (Santos-Sacchi and Huang, 1998). The predictions of the modified model are very sensitive to the parameters chosen. The expression for the energy barrier gives an insight into how the model behaves under changing turgor pressure. The linear terms in stress (i.e., Tzaz + Tcac) tend to shift the curves toward more positive voltages when turgor is increased. The quadratic terms, however, have the opposite effect. At very low turgor pressures, the linear terms dominate and the model predicts the correct trend. However, at higher turgor pressures the quadratic terms dominate and the curves shift in the opposite direction.

The flattening effect of the capacitance curve at higher turgor pressures is also seen in the model. This is due to the changing turgor pressure in the OHC as the voltage is varied and the quadratic terms in the energy barrier. The presence of quadratic terms in the barrier expression implies that there is no perfect ratio of the active area change that will maintain turgor pressure when voltage is changed. In the earlier model fixing az / ac = −2 ensured active deformations that satisfied the incompressibility constraint (Hallworth, 2003). This meant that we could change voltage without affecting the turgor pressure. This is not possible in the new model.

The modified area motor model did not show significant changes in the maximum capacitance as the turgor pressure was varied. This could be due to an area effect that is not modeled correctly due to the cylindrical assumption made for the OHC shape. At higher pressures, the OHC will tend to assume a more spherical shape and reduce its overall surface area that will lead to lower capacitance.

Simulations done for varying temperatures do not show much change in the capacitance curves. The only temperature-dependent term in the equations is Pe, which is quite insensitive to temperature changes. It will be possible to model both temperature and turgor effects with this model if we allow q, the charge transferred, to vary with the stress and temperature. However, as of yet, there is no known or suspected physical basis for such a variation to occur.

CONCLUSION

By introducing probability dependence of elastic constants, the predictions from a modified area motor model match experimental results for stiffness change and capacitance. The correct stiffness behavior in the model yields sufficient nonlinearity to match the harmonic content of the dynamic simulations. It should be noted however that very little data are available with which to compare stiffness predictions. The chief sources of variable OHC stiffness data are He and Dallos (1999, 2000). The effective stimulus voltage is unknown in He and Dallos (2000), whereas the patch-clamp experiments done in He and Dallos (1999) provide data from a small number of OHCs and over a limited range of voltage. More experimental results are needed to determine the new elastic coefficients introduced in the modified model. For the purpose of this study the elastic coefficients were varied uniformly about published values. The theoretical results of this article point toward the importance of obtaining coupled capacitance, electromotility, and stiffness experimental data for the same outer hair cell to provide information for the constitutive models.

Without changing values of the charge transferred across the membrane, the modified model cannot explain the effect of turgor pressure on capacitance versus transmembrane voltage curves. The model hints toward a possible dependence of charge q on the turgor pressure, which would enable correct model behavior when turgor pressure is changed. It should be noted that change in shape of capacitance versus voltage curves for changing turgor pressure has not been observed in prestin transfected cells (Ludwig et al., 2001; Santos-Sacchi et al., 2001a) or even in OHC membrane patches (Gale and Ashmore, 1997). So it is possible that the structure of the OHC wall or some other effect plays a role in modifying the motor protein behavior when turgor pressure is changed. This needs to be investigated further to improve models for OHC behavior.

An interesting artifact of OHC behavior that we have not simulated in this article is the isolated OHC response to acoustic stimuli. OHCs subjected to stimulus on their lateral walls using fluid jets exhibit length changes in the longitudinal direction (Brundin et al., 1989; Brundin and Russell, 1994). Because there is no external regulation of the transmembrane voltage, this can be construed as evidence of motility arising through change in stress or strain in the plasma membrane. A recent study (Rybalchenko and Santos-Sacchi, 2003) reports existence of stretch-sensitive conduction channels within the lateral membrane. The new study sheds light into the role of anions in triggering conformal changes in the motor protein prestin. It brings into question the exact manner in which the anions bring about this conformal change. The current opinion on prestin electromotility is that it is effected through some voltage sensor (Oliver et al., 2001). There are doubts about whether a voltage-sensing scheme would work in vivo at high frequencies because of the low-pass membrane filter of the OHC. Rybalchenko and Santos-Sacchi (2003) propose an alternate mechanism that involves anion currents rather than the voltage influencing prestin state transitions. The experiments considered in this article include both, studies that used ion channel blockers (nonlinear capacitance studies) and those that did not use any ion channel blockers (stiffness experiments). Because motility and nonlinear capacitance has been seen irrespective of whether transmembrane anion currents were blocked or not, further experiments are needed to ascertain the role of anions in eliciting prestin state transitions. A better understanding of the process by which these motor transitions are affected will help improve the model and enable modeling of other experimental effects of OHCs like their response to jet stimuli. Adapting the model to a current-gating or other triggering mechanism will be straightforward as the model's essential working (state-dependent stiffness and motility) would remain the same.

The models presented in this article represent progress toward developing a comprehensive OHC model that correctly predicts the cell's behavior to electromechanical stimulation. We have started our models with stress-strain (Eqs. 21 and 22) and voltage-charge (Eq. 22) relations and then derived the free-energy function that is consistent with those relations. The resulting free-energy functions are more complicated and not as physically based as we would like. It may be that an approach that starts with a model based on a free-energy function and then derives the associated field dependencies from the free-energy function may yield more complete results.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jeffrey Bischoff for his contribution to the initial stages of this work and an anonymous reviewer for his comments and suggestions on this article.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant NIDCD R01–04084).

APPENDIX A: SOLUTION APPROACH

To find initial equilibrium condition for the OHC models the following method is used. First Eqs. 2 and 3 are solved for a given (resting) turgor pressure and voltage to evaluate the volume constraint ɛvol. Once this initial condition is set, perturbations occur around this operating point such that the cell volume remains constant.

|

(A-1) |

Expanding this equation and ignoring second-order terms yields

|

(A-2) |

When the resting voltage is changed, the OHC undergoes deformation in an incompressible fashion from the initially computed equilibrium position. This causes change in the turgor pressure. To evaluate axial strain we use Eq. 18. Because Pe depends on the axial strain a Newton-Raphson iteration is used to solve the implicit equation. The iteration is started with a trial value for ɛz from which initial guess for Pe is computed. Thus, ɛz is computed for different voltages. ɛc is obtained using the incompressibility condition (Eq. A-2). Stiffness and capacitance are obtained from their respective analytical expressions.

APPENDIX B: PARAMETERS

The elastic coefficients used for the modified model are  cs = 0.0143 Nm−1,

cs = 0.0143 Nm−1,  cl = 0.0464 Nm−1. Other parameter values are given in Table 1. Clin was obtained from Santos-Sacchi and Navarrete (2002). Iwasa (2001) was used as a guide for choosing the rest of the parameters. Other standard constants used are Boltzmann constant kB = 1.38 × 10−23 JK−1 and temperature (for simulations with constant temperature) θ = 300 K. F0 was adjusted as needed to have peak capacitance voltage around the desired voltage.

cl = 0.0464 Nm−1. Other parameter values are given in Table 1. Clin was obtained from Santos-Sacchi and Navarrete (2002). Iwasa (2001) was used as a guide for choosing the rest of the parameters. Other standard constants used are Boltzmann constant kB = 1.38 × 10−23 JK−1 and temperature (for simulations with constant temperature) θ = 300 K. F0 was adjusted as needed to have peak capacitance voltage around the desired voltage.

Table 1.

Parameter values

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| L | 70 | μm |

| R | 5 | μm |

| q | −1.602 × 10−19 | C |

| dc | 0.068 | Nm−1 |

| dz | 0.046 | Nm−1 |

| c | 0.046 | Nm−1 |

| n | 9000 | (μm)−2 |

| ac | −0.75 | (nm)2 |

| az | 4.5 | (nm)2 |

| Clin | 21.9 | pF |

APPENDIX C: COMPLIANCE COEFFICIENTS

The compliance coefficients are obtained by inverting the elastic coefficients matrix.

|

(A-3) |

The short and long coefficients are obtained by substituting the corresponding long and short elastic coefficients.

References

- Achenbach, M., T. Atanackovic, and I. Muller. 1986. A model for memory alloys in plane-strain. International Journal of Solids and Structures. 22:171–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore, J. F. 1987. A fast motile response in guinea-pig outer hair cells: the cellular basis of the cochlear amplifier. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 388:323–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore, J. F. 1990. Forward and reverse transduction in the mammalian cochlea. Neurosci. Res. Suppl. 12:S39–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell, W. E., C. R. Bader, D. Bertrand, and Y. D. Ribaupierre. 1985. Evoked mechanical responses of isolated cochlear hair cells. Science. 227:194–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundin, L., A. Flock, and B. Canlon. 1989. Sound-induced motility of isolated cochlear outer hair cells is frequency-specific. Nature. 342:814–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundin, L., and I. Russell. 1994. Tuned phasic and tonic motile responses of isolated outer hair cells to direct mechanical stimulation of the cell body. Hear. Res. 73:34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, G., W. Hemmert, and A. Gummer. 1999. Limiting dynamics of high-frequency electromechanical transduction of outer hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:4420–4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale, J. E., and J. F. Ashmore. 1997. The outer hair cell motor in membrane patches. Pflügers. Arch. 434:267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallworth, R. 2003. The strain ratio of the outer hair cell motor protein. In Biophysics of the Cochlea: From Molecules to Models. World Scientific, Singapore. 144–150.

- He, D. Z. Z., and P. Dallos. 1999. Somatic stiffness of cochlear outer hair cells is voltage-dependent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:8223–8228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, D. Z. Z., and P. Dallos. 2000. Properties of voltage-dependent somatic stiffness of cochlear outer hair cells. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 01:64–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa, K. H. 1993. Effect of stress on the membrane capacitance of the auditory outer hair cell. Biophys. J. 65:492–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa, K. H. 2001. A two-state piezoelectric model for outer hair cell motility. Biophys. J. 81:2495–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa, K. H., and M. Adachi. 1997. Force generation in the outer hair cell of the cochlea. Biophys. J. 73:546–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehata, S., and J. Santos-Sacchi. 1995. Membrane tension directly shifts voltage dependence of outer hair cell motility and associated gating charge. Biophys. J. 68:2190–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, J., D. Oliver, G. Frank, N. Klocker, A. Gummer, and B. Fakler. 2001. Reciprocal electromechanical properties of rat prestin: the motor molecule from rat outer hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:4178–4183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, D., D. Z. Z. He, N. Klocker, J. Ludwig, U. Schulte, S. Waldegger, J. P. Ruppersberg, P. Dallos, and B. Fakler. 2001. Intracellular anions as the voltage sensor of prestin, the outer hair cell motor protein. Science. 292:2340–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathi, A. A., K. Grosh, J. Zheng, and A. L. Nuttall. 2003. Effect of current stimulus on in vivo cochlear mechanics. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 113:442–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybalchenko, V., and J. Santos-Sacchi. 2003. Cl− flux through a non-selective, stretch-sensitive conductance influences the outer hair cell motor of the guinea-pig. J. Physiol. 547:873–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi, J. 1991. Reversible inhibition of voltage-dependent outer hair cell motility and capacitance. J. Neurosci. 11:3096–3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi, J., and J. P. Dilger. 1988. Whole cell currents and mechanical responses of isolated outer hair cells. Hear. Res. 35:143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi, J., and G. Huang. 1998. Temperature dependence of outer hair cell nonlinear capacitance. Hear. Res. 116:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi, J., and E. Navarrete. 2002. Voltage-dependent changes in specific membrane capacitance caused by prestin, the outer hair cell lateral membrane motor. Pflügers. Arch. 444:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi, J., W. Shen, J. Zheng, and P. Dallos. 2001a. Effects of membrane potential and tension on prestin, the outer hair cell lateral membrane motor protein. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 531:661–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi, J., M. Wu, and S. Kakehata. 2001b. Furosemide alters nonlinear capacitance in isolated outer hair cells. Hear. Res. 159:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehata, W. E., W. E. Brownell, and R. Dieler. 1991. Effects of salicylate on shape, electromotility and membrane-characteristics of isolated outer hair-cells from guinea-pig cochlea. Acta Otolaryngol. 111:707–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector, A. A., M. Ameen, and A. S. Popel. 2001. Simulation of motor-driven cochlear outer hair cell electromotility. Biophys. J. 81:11–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolomeo, J. A., and C. R. Steele. 1995. Orthotropic piezolelectric properties of the cochlear outer hair cell wall. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 97:3006–3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]