Abstract

Despite investigation since the 1950s, the molecular architecture of intermediate filaments has not yet been fully elucidated. Reliable information about the longitudinal organization of the molecules within the filaments and about the lateral interfilament packing is now available, which is not the case for the transverse architecture. Interesting results were recently obtained from in vitro microscopy observations and cross-linking of keratin, desmin, and vimentin analyses. The structural features that emerge from these analyses could not be fully representative of the in vivo architecture because intermediate filaments are subject to polymorphism. To bring new light to the transverse intermediate filament architecture, we have analyzed the x-ray scattering equatorial profile of human hair. Its comparison with simulated profiles from atomic models of a real sequence has allowed results to be obtained that are representative of hard α-keratin intermediate filaments under in vivo conditions. In short, the α-helical coiled coils, which are characteristic of the central rod of intermediate filament dimers, are straight and not supercoiled into oligomers; the radial density across the intermediate filament section is fairly uniform; the coiled coils are probably assembled into tetrameric oligomers, and finally the oligomer positions and orientations are not regularly ordered. These features are discussed in terms of filament self-assembling and structural variability.

INTRODUCTION

Intermediate filaments (IFs) form a large class of filamentous proteins distinct from microtubules and actin-containing filaments. They are believed to interact with both the nuclear and the cytoplasmic membranes and share common primary sequence features, in particular in the distribution of apolar residues (Parry and Steinert, 1995). Among IFs, keratins are the most abundant; they constitute the main component of the epidermis and its appendages in higher vertebrates. Like other IF family members, hard α-keratin mainly acts as a mechanical support. Keratin-containing tissues were first studied for the economic importance of animal fibers in the textile industry (wool), along with cosmetic related aspects such as hair growth and epidermis substitutes. A new impetus is now given by the need to understand the effect of mutations in keratins that sometimes result in severe disruption of the entire tissue, such as in epidermis. The interest in deciphering keratin architecture is also driven by its role as a model structure for all other IF members (vimentin, desmin, etc.) that are also involved in many diseases. Since these proteins do not crystallize (only fragments were recently crystallized; Strelkov et al., 2002) nor give rise to highly condensed phases like keratin, only a little information about their molecular and supramolecular architectures is available. Their structures are supposed to be close to that of keratin, more precisely of hard α-keratin, though the molecules greatly differ in their C- and N-terminal parts.

A classification based on different biosynthesis modes and corresponding to tactile sensation distinguishes soft from hard keratins (Giroud and Leblond, 1951). Soft keratins are found in epidermis and calluses. Hard keratins are generally classified into two groups, hard α-keratin (α-helix-based) found in mammalian epidermal appendages (hairs, quills, horn, nails, etc.) and β/feather keratin (β sheet-based) found in avian and reptilian tissues.

Hard α-keratin molecular structure has been studied since the 1930s because it leads to x-ray scattering patterns rich enough to provide valuable structural information, contrary to soft keratin from epidermis. In the present article, we will only consider the architecture of hard α-keratin in standard conditions, i.e., the architecture that should be representative of the structures of most IFs.

The structure of hard α-keratin in hair shaft and porcupine quill was inferred from x-ray scattering and electron microscopy analyses. Three structural hierarchy levels characterize it. At high resolution, the 450 Å long molecules are assembled into dimers that are characterized by a rodlike central part, composed of α-helical coiled coils (Crick, 1953; Pauling et al., 1951), at the extremity of which are located the globular C- and N-terminal domains. This regular coiled-coil folding gives rise to the wide-angle x-ray scattering (WAXS) meridian arc located in the 5.15 Å region. The strong intensity of this arc was shown to be related to the fine configuration of residues (Busson et al., 1999). At medium resolution, i.e., the intermediate scale arrangement of the chains inside IFs, the molecules are assembled both longitudinally and laterally, forming long cylinder-shaped intermediate filaments (Birbeck and Mercer, 1957). At low resolution, bundles of parallel intermediate filaments embedded in a sulfur-rich protein matrix form a macrofibril (subcomponent of cortical cells). The pioneering x-ray scattering analyses of R. D. B. Fraser have established that the IFs are located at the nodes of a distorted two-dimensional quasicrystalline array (Fraser et al., 1964a,b). This model was later refined using an analytical description of the corresponding small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) equatorial x-ray scattering pattern (Briki et al., 1998).

The knowledge of the medium resolution is poorer than for the high and low resolutions. Axially, the strong and fine 67 Å meridian scattering arc is indicative of a well-defined periodic ordering of the molecules along the IF. Radially, the number of molecules across a keratin IF section is assumed to be ∼26–34 (Engel et al., 1985) and the IF diameter is fairly constant (74–75 Å) (Fraser et al., 1976; Briki et al., 1998), but little is known about their geometrical distribution across the section despite many efforts during the past 50 years. The putative existence of intermediate organization levels into tetrameric (two coiled coils or four chains) or octameric (four coiled coils or eight chains) oligomers (called protofibrils and protofilaments in the literature) is still debated. The other major debate concerns the radial density profile, i.e., a ring-core profile versus a uniform profile. Let us sum up the outlines of the related abundant literature.

From electron microscopy observations Filshie and Rogers (1961) proposed an IF model consisting of a 20 Å diameter oligomer arranged into a ring-core pattern (nine in the outer ring and two in the center). The interpretation in terms of organized oligomers has been subject to controversy (Dobb and Sikorski, 1969; Fraser et al., 1969) but the ring-core model, which was inspired from the structure in cilia and in certain flagella, was subsequently confirmed by various electron microscopy-based analyses (Fraser et al., 1971; Millward, 1970).

The molecular arrangement model across the IF section was also investigated from the x-ray scattering equatorial profile analysis. Fraser et al. (1964b) developed a model consisting of nine three-strand coiled coils disposed along a 28 Å diameter ring and they calculated the corresponding SAXS and WAXS profiles. Bailey et al. (1965) proposed a similar model, with nine protofibrils 17 Å in diameter, located along a 59 Å diameter circle, plus one or two coiled coils in the core. The calculated profiles are in rather good agreement as regards the peak positions and intensities in the SAXS region; however, none of the models is fully convincing because the scattering intensity at medium resolution (typically, scattering vector S from 0.03 Å−1 to 0.08 Å−1) is not correctly reproduced. Other models were envisaged (Fraser et al., 1976, 1985; Wilk et al., 1995), but they remained speculative and were not assessed on a new experimental basis. Furthermore, these models were developed up to the 1970s with three-strand coiled coils and not two-strand coiled coils as is now admitted. Attention was recently paid to the ring-core versus uniform core question. Parry (1996) concluded from a mathematical analysis that a ring-core model with an outer diameter of 88 Å and an inner diameter of 58 Å or 70 Å gives a SAXS profile similar to that given by a uniform 75 Å diameter cylinder; however, this 88 Å outer diameter seems too large compared to the inter-IF distance. Briki et al. (1998) showed that whereas the human hair IF seemed to correspond to a uniform-density cross section, the porcupine quill IF was more consistent with a ring-core structure.

In parallel with electron microscopy or x-ray scattering analyses of filaments embedded in their tissues, i.e., under in vivo conditions, a series of analyses were carried out on isolated or reconstructed filaments, i.e., under in vitro conditions. A new approach consisted of the crystallographic structure determination of short crystallized IF fragments (Strelkov et al., 2002). This technique provides high-resolution information but, being limited to short pieces, it is not yet exploitable for the IF global structure investigation. Electron microscopy observations of disintegrating IF (Aebi et al., 1983; Franke et al., 1982) revealed the existence of two oligomeric levels consisting of tetramers assembled into octamers. More recently, cryoelectron microscopy on isolated keratin IF supported the model of a low-density core (Watts et al., 2002). Electrophoresis performed on reassembled wool keratin material lent support to the existence of oligomers made of four chains laterally aligned as a pair of two-strand α-helical coiled coils (Gruen and Woods, 1983). The most original analysis is probably the cross-linking technique which was first used to investigate the IF fine structure (Geisler et al., 1992; Geisler, 1993; Steinert et al., 1993a,b). This technique gives access to the various assembly modes between coiled coils and to their corresponding axial staggers, permitting a three-dimensional model to be sketched and to be assessed by comparison to meridian x-ray scattering features. The existence of tetramers in keratin IF was also inferred from this method (Steinert et al., 1993a).

These in vitro approaches, which are interesting because they can be used for all IF types and generally yield high-resolution information, converge toward the existence of tetramers.

Despite several decades of investigation, the putative chain organization inside IFs still remains mysterious; this organization is referred to as medium resolution. To bring new light to this old problem, more precisely the nature of the oligomers, possible supercoiled organizations and the IF transverse structure, we have adopted a strategy which is based on the comparison of an experimental IF x-ray scattering equatorial profile with modeled profiles obtained from atomic models made of a real IF sequence. The experimental profile being that of native human hair, our results should be representative of hard α-keratin IF under in vivo conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

X-ray diffraction experimental profile

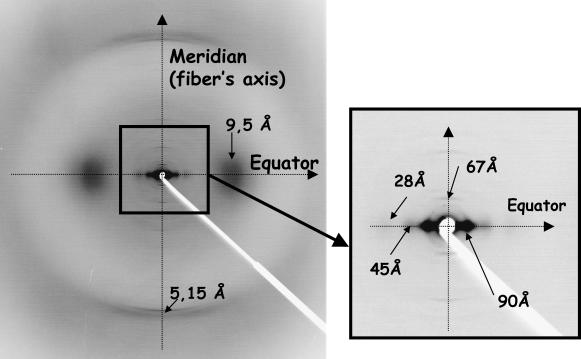

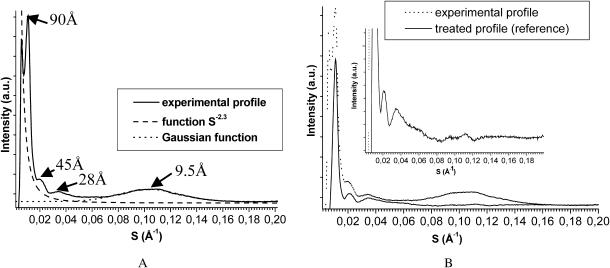

The reference x-ray diffraction equatorial profile (the equator is perpendicular to the IF axis) was extracted from a two-dimensional pattern (Fig. 1). It was obtained using the synchrotron x-ray source of LURE (Université Paris-Sud) on the D43 beamline, with a collimated and monochromatic incident beam (0.5-mm diameter, wavelength λ = 1.450 Å) selected by a Ge (111) bent monochromator. The sample consisted of a bundle of ∼50 hair shafts from a male donor inserted into a capillary glass (0.7-mm diameter) and aligned parallel to the capillary axis with an error of ±2°. A transmission geometry with a sample-detector distance of 188 mm allowed both WAXS and SAXS to be collected at room temperature and room humidity. The pattern was recorded on Fuji imaging plates located perpendicular to the incident beam and was read using a molecular dynamics scanner (STORM; Sunnyvale, CA) with a pixel size of 0.1 × 0.1 mm2. The angular resolution Δ(2θ), which is limited by the detector, was 0.06°. This value corresponds to the subtended angle by the pixel size. The rough one-dimension equatorial profile corresponds to an intensity integration around the equator in a 9-pixel-thick rectangular band (Fig. 2 A). This profile has been treated to bring out the small- and medium-resolution scattering profiles arising from the IF:

In the SAXS zone, the huge scattering intensity (proportional to S−2.3) was shown to proceed from nonkeratinous zones in hair (Briki et al., 1998). This component has been subtracted from the profile.

In the WAXS zone the broad scattering maximum located at ∼9.5 Å is supposed in the literature to be due to interferences between coiled-coil chains (Fraser et al., 1964a,b). Its relative intensity versus SAXS features was shown to be enhanced by a contrast effect arising from other proteins surrounding the IFs (Fraser et al., 1964a,b). This aspect being out of the scope of the present study, the 9.5 Å broad peak has been fitted by a Gaussian function and then subtracted from the experimental profile that is used for comparison to our simulations.

The profile thus obtained will be used as a reference for our study; it is presented in Fig. 2 B.

FIGURE 1.

X-ray scattering pattern of a bundle of human hair obtained using synchrotron radiation source of LURE (D43 station) and recorded on a flat detector perpendicular to the x-ray beam. The hairs' axes are vertical.

FIGURE 2.

Equatorial x-ray scattering profile of human hair: rough profile and the two intensity components that were subtracted (A); the corresponding treated profile (B) is used as a reference to validate the simulations; this treated intensity profile is shown in an expanded scale in the (B) inset.

We checked that the parasitic scattering from the air or the glass capillary was weaker than the signals from the sample in the SAXS zone.

It is the dense lateral IF packing that produces the three equatorial peaks located at S = 0.012, 0.022, and 0.036 Å−1 (respectively corresponding to the distances 83 Å, 45 Å, and 28 Å; note that the 83 Å value is smaller than the value of 90 Å found in the literature, which is the value before background subtraction). The presence of a fourth peak at 0.06 Å−1, hardly visible before profile treatment, had never been mentioned before. Let us note that the choice of our hair sample was focused on a lipid signal-free sample. Hair contains crystallized lipids (Fraser et al., 1963), more precisely soaps (Briki et al., 2003), that give rise to a series of rings, of which the first order is superimposed on the peak at 45 Å. The signals due to soaps are the only variable scattering signals displayed by hair; the signals due to keratin are fairly sample-independent.

From the angular width of the equatorial reflections along the meridian, it is possible to estimate the crystallographic coherence length that is associated with the transverse IF structure. This value corresponds to the apparent longitudinal size of the objects that scatter x-rays. After correction from the instrument resolution (0.06°) and from the angular spread due to intrinsic and extrinsic IF alignment (6° estimated from the meridian arcs) it turns out that the actual angular width is of the order of 0.25° ± 0.05° which, using the Scherrer formula, leads to an axial coherence length of the order of 300 ± 30 Å. This value indicates that the x-ray equatorial scattering patterns arise from segments shorter than the molecular length (∼450 Å).

Molecular architecture and coiled-coil model building

Keratin molecules mostly comprise α-helical coiled-coil segments, which are separated by noncoiled-coil short linkers. The C- and N-terminal parts are globular. The x-ray scattering modeling was carried out only taking into account the coiled-coil segments because the contribution of the globular parts of the molecules should be very diffuse and should not give rise to other peaks.

Hard α-keratin coiled coils are heterodimers of type I and type II intermediate filament proteins (Gillespie, 1990). The sequences used here were those of the longest uninterrupted heptad repeat (1B fragment, 101 residues per chain) of proteins extracted from wool fibers, as sequenced by Dowling et al. (1986) for the 8c-1 protein (type I) and Sparrow et al. (1989) for the complementary 7c (type II). These fragments are about twice as short as the axial coherence length estimated above; however, we have found that building longer models only leads to minor changes in the x-ray scattering modeling.

Crick's equations were first used to calculate Cα atom coordinates. The building of the coiled coil requires three independent parameters: the axial rise per residue hcc, coiled-coil radius r0 and pitch p0 (Busson and Doucet, 1999). We have chosen the commonly used value hcc = 1.485 Å for intermediate filaments (Fraser et al., 1964b). The coiled-coil pitch and radius cannot be directly measured experimentally (Fraser and MacRae, 1971) and were chosen according to the standard values found in coiled-coil pieces (Phillips, 1992; Seo and Cohen, 1993) and GCN4 leucine zipper (Phillips, 1992): r0 = 4.65 Å and p0 = 140 Å. Other main-chain atoms were then placed using the O program (Jones, 1985) and side chains were finally added in the same way and positioned using SCWRL package (Bower et al., 1997).

To obtain a realistic model for an entire IF, axial association was also modeled. The rod zones that were built using the method described above were completed as follows. Each linker and terminal zone structure in the molecular sequence was predicted using the FASTA method (Pearson and Lipman, 1988). The molecular structures thus obtained were then associated axially following the modes that have been demonstrated by cross-link studies (Parry et al., 2001; Steinert et al., 1993a).

X-ray diffraction simulations

X-ray diffraction patterns were simulated using a homemade program (Doucet and Benoit, 1987) that reproduces the intensity scattered on a plane detector. The intensity as a function of the scattering vector S is modeled as

|

with F(S) the structure factor of one IF, Z(S) the interference function arising from the relative lateral positions of the IF, and L and P two scattering geometry dependent factors (Lorentz and polarization). The polarization factor expression for a synchrotron radiation beam selected by a cylindrically curved crystal monochromator was calculated by Kahn et al. (1982); it is almost constant within the small scattering vector zone that was simulated. The Lorentz factor, which is equal to (cos 2θ)3 where 2θ is the diffraction angle, accounts for both the beam divergence and the still geometry with a plane detector perpendicular to the incident x-ray beam. In short, S is calculated successively for each pixel (x, z) of the simulated pattern (x along the equatorial axis and z along the meridian). The structure factor sums up the atomic contributions (phase and amplitude):

|

where fj and rj represent, respectively, the atomic scattering factor and the position vector for the jth atom.

We assumed that the IFs were located at the nodes of a two-dimensional hexagonal array. As was previously developed (Briki et al.,1998) this model lattice was better fulfilled when it was distorted following a paracrystalline disorder. This assumption allowed the analytical representation of Z(S) that was described therein. The average length of the hexagonal lattice was set to a = 90 Å and its standard deviation to 25% the length value.

Two-dimensional zones, 501 pixels along x and 9 along z (centered around the origin of the reciprocal space), were simulated according to the experimental scattering conditions. The pixel size along the x and z axes was 0.1 mm, which corresponds in reciprocal units to ∼5.10−4 Å−1. Simulated patterns were finally cylindrically averaged by adding the intensities produced by 36 coiled coils, related by successive 10° rotations around their axes, to take into account the random orientation of the IFs with respect to the x-ray beam. This procedure only played a minor role because the scattering features of a one-pitch long coiled-coil piece were already nearly symmetrical around the coiled-coil axis.

The quality of the simulated profiles was assessed by visual inspection and comparison with the reference experimental profile (Fig. 2 B). The comparison criteria were the positions of the peaks, their relative intensity, and their angular width.

RESULTS

The choice of models

The choice of models was guided by three major criteria. The first one consisted of testing as many major models discussed in the literature as possible. These models have generally been developed on the basis of data yielded by a given experimental source. We aimed here to obtain models globally compatible with the various experimental source data: electron microscopy, x-ray scattering, cross-linking, molecular modeling, etc. The second criteria was to include the structural information available in the literature, mainly the cylinder-shaped IF of ∼75 Å diameter; the distance between IF in hair is ∼90 Å and the number of chains within an IF cross section is between 24 and 32. The third criteria was to explore all the possible classes of structure that are x-ray scattering-sensitive, which means that attention was paid to geometrical parameters such as relative positions, distances, and orientations, whereas chemical links between molecules cannot be investigated by our method. The resulting questions that were examined were consequently: the overall low-resolution IF shape, the supercoiling versus linear axial arrangement along the IF, the existence and nature of oligomers in addition to the dimeric coiled coils (tetramers or octamers) and the relative orientations and positions of the molecules across the IF section.

The density shape across the IF section is globally uniform

An important item for our purpose is to evaluate the density shape within the IF. The density shape across the IF section might either be uniform or present a core with a lower or a higher value. This question can be tackled readily by modeling the SAXS equatorial intensity with a low-resolution approximation of the IF section, i.e., a full cylinder or an empty core cylinder. For a cylinder of outer radius r2, inner radius r1 and density ρ between r1 and r2, the structure factor takes the analytical form

|

with ui = 2πriS and J1 the first-order Bessel function.

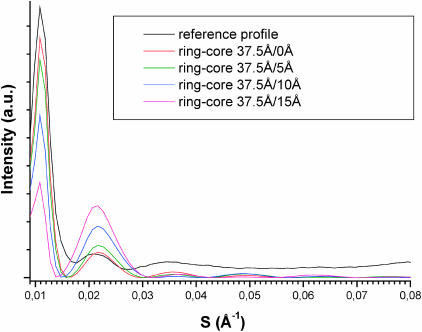

Fig. 3 shows calculated equatorial profiles for cylinders with an outer radius of 37.5 Å and with various empty-inner core radii: 0 Å (full cylinder), 5 Å, 10 Å, and 15 Å. The agreement with the experimental profile is good for the full cylinder, whereas the 10 Å and 15 Å radius empty-core cylinders lead to rather poor agreement. The intensity ratios of the second (45 Å) and third (28 Å) peaks versus the first peak (90 Å) are far from the experimental ratios. However, the 5 Å radius inner core leads to a satisfactory profile. It can be concluded that the molecular density across the IF section in hair can be considered as uniform in a low-resolution approximation or, should it contain a core, its radius is <∼7 Å, i.e., less than a coiled-coil radius.

FIGURE 3.

Equatorial profiles calculated for various ring-empty core cylinder-shaped IF. The outer radius is equal to 37.5 Å and the core radius is equal to 0, 5, 10 or 15Å. The models with 10 and 15 Å radius core lead to profiles which are significantly different from the reference profile.

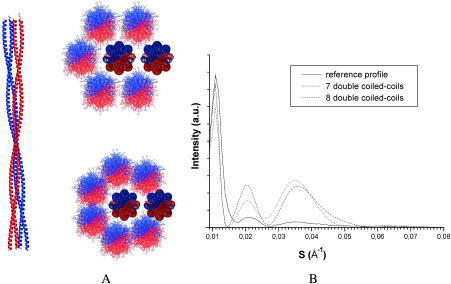

The molecules are not assembled into supercoiled oligomers

Two supercoiled architectures were modeled. The first one, called hereafter “double coiled coil,” is constituted by two coiled coils wound up around a common axis in the opposite direction to the coiled-coil twirling direction. The double coiled-coil model was built with a superhelical pitch equal to 560 Å and a center-to-center distance between coiled-coil axes equal to 13 Å. This avoids steric hindrance between side chains (Fig. 4 A). This superhelical pitch value (equal to 4× the coiled-coil pitch) corresponds to a realistic supertwirling; too small a pitch would lead to angles between the filament and the α-helical chains not compatible with the x-ray patterns (i.e., >5°–10° as indicated by the extent of the 5 Å meridian reflection), whereas too large a pitch would be meaningless for our purpose because it would lead to a super-twirling not distinguishable from straight parallel chains. Two equatorial scattering simulations corresponding to models with seven and eight double-coiled coils (Fig. 4 A) are given in Fig. 4 B. The intensity of the third peak (28 Å) is too high compared to that of the two other peaks. This is clearly due to the interference effects produced by the regular ordering of the double coiled coils imposed by the superhelical configuration. For instance, double coiled coils 30 Å apart (as in the models in Fig. 4) located on a hexagonal or quasihexagonal array give rise to a Bragg reflection at 26 Å which is superimposed and more intense than the third peak expected from the overall cylindrical shape. This explanation is confirmed by the position shift of the peak when varying the distance between double coiled coils.

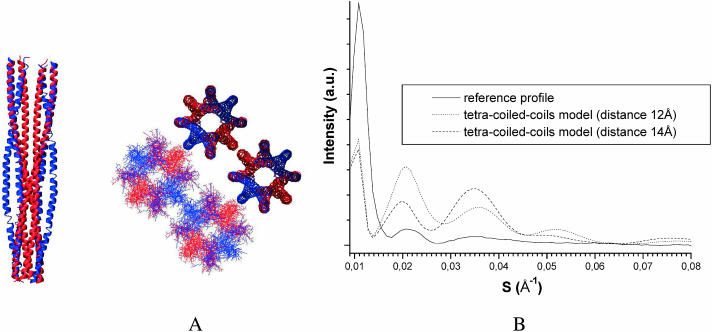

FIGURE 4.

Supercoiled tetramer-based models (double coiled coils). (A) Axial architecture with the two coiled coils in blue and red and two IF transverse architectures with seven and eight tetramers. (B) The corresponding calculated x-ray scattering equatorial profiles.

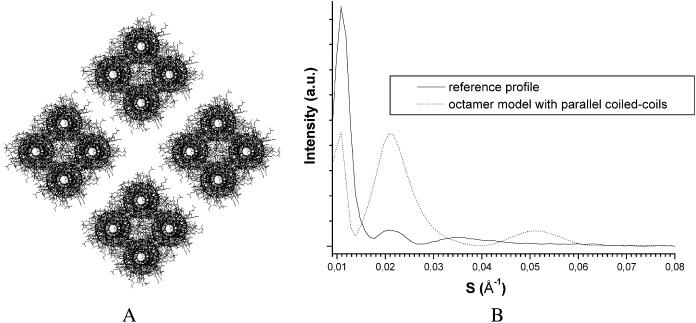

The second supercoiled architecture tested is an octamer consisting of two double coiled coils wound up around a common axis in the opposite direction to that of the double coiled coil (called hereafter “tetra-coiled coil”). Two IF models containing four tetracoiled coils with 560 Å helical pitch (for the same reasons as above), coiled-coil axes diametrically 12 Å or 14 Å apart, and 28 Å center-to-center distances, were modeled (Fig. 5 A). The corresponding equatorial scattering profiles (Fig. 5 B) are very different from the experimental profile as regards the relative intensities. As for the double coiled coil-based models, the interferences produced by the regular distances between the axes of the tetra-coiled coils yield intense diffraction peaks in the SAXS region more intense than the peaks arising from the overall cylindrical IF shape. This effect is again reinforced by the regular distances between the chains within a given tetra-coiled coil.

FIGURE 5.

Supercoiled octamer-based models (tetra-coiled coils). (A) Octamer axial architecture with two coiled-coils in blue and two others in red and an IF transverse architecture with four octamers, two represented with the main chains and two others with all the atoms. (B) The corresponding calculated x-ray scattering equatorial profiles for two distances between opposite coiled-coil axes within an octamer, 12 Å (as in A) and 14 Å.

These two oligomeric supercoiled models do not account for the experimental equatorial x-ray scattering profile. It is obvious that this conclusion can be extended to all supercoiled structures because the few regularly spaced-out oligomers across the IF section, as well as the regular spacing of the chains within an oligomer, will always give rise to intense interference peaks. The coiled coils are therefore not involved in supercoiled architectures at the supramolecular level, which nevertheless does not eliminate the possibility of an overall very large-pitch supercoiled IF architecture.

Models with straight coiled coils

Three series of IF models with straight and parallel coiled-coil pieces were analyzed: a series with four coiled coils (octamers), another with two coiled coils (tetramers), and the third with separated coiled coils (dimers).

Octamer-based models

Only compact octamers have been considered, i.e., octamers consisting of four coiled coils forming a parallelogram and four oligomers per IF section. The noncompact octamer-based models with parallel coiled coils, which are not easily distinguishable from the tetramer-based models, will be discussed below. Such a noncompact octamer-based model is similar to the “unit-length filaments” that were observed during IF vimentin assembly in solution by electron microscopy (Hermann et al., 1996). A more compact oligomer, like those envisaged here, could result from the putative compaction of a unit-length filament (Strelkov et al., 2003). In Fig. 6, one octamer-based model is shown (distance between coiled coils, 13 Å; center-to-center distances between opposite tetramers, 49 Å) with its simulated scattering profile. The conclusion is straightforward: the simulated profiles yielded by octamers are different from the experimental profile. The reason is the same as for the supercoiled models: the interferences arising from the intra- and interoctamer regular distances induce a huge and broad scattering peak centered around 42 Å. We have checked that the introduction of some irregularity into the distances between monomers or between oligomers does not change significantly the scattering pattern. On this basis, the compact octamer-based models were not satisfactory models.

FIGURE 6.

(A) Octamer-based transverse IF architecture with parallel coiled-coils; the distance between neighboring coiled coils is 13 Å and the distance between two opposite octamers is 49 Å. (B) The corresponding calculated x-ray scattering equatorial profile.

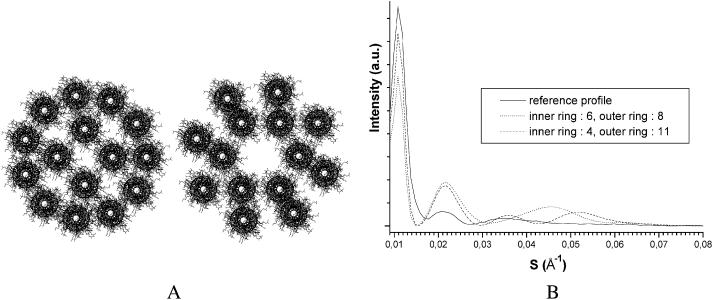

Separated coiled coil-based models (dimers)

To avoid interference effects arising either from intra- or inter- oligomer regular distances between coiled coils, a series of IF models in which the coiled coils are not assembled into oligomers was envisaged. Their basic feature consisted of two rings, an inner one containing 3–6 coiled coils and an outer one containing 7–11 coiled coils. The earlier ring models proposed by Fraser inspired them. A selection of these models is shown in Fig. 7 A and their simulated scattering profiles in Fig. 7 B. The scattering profiles were model-dependent but they all displayed peaks in the zone 50–15 Å which were more intense than in the experimental profile. This was well pronounced for the model with nine coiled coils in the outer ring and five in the inner one, which yielded a strong peak at 20 Å due to the regular coiled-coil distances. Better profiles were obtained either when the distances were less regular, like in the model with 11 coiled coils in the outer ring and 3 in the inner one, or when introducing some variability in the distance between coiled coils, but no fully satisfactory profile could be obtained. The separated coiled coil-based models gave better agreement with experimental profiles than the four coiled coil-based models but they were nevertheless not convincing enough to be retained as reliable IF models.

FIGURE 7.

Two separated coiled coil-based models consisting of an inner and an outer ring with a different number of coiled coils (A), and the corresponding calculated x-ray scattering equatorial profiles (B).

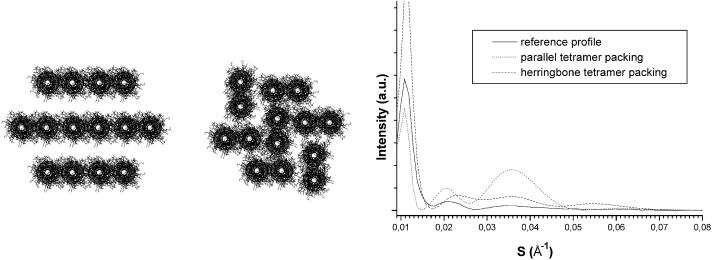

Tetramer-based models

From the previous conclusions it can be inferred that regular distances between the coiled-coil positions across the IF section produced interferences that resulted in extra scattering equatorial peaks. These extra peaks were more intense than those produced by the uniform-density cylindrical model, the simulated profile of which was in good agreement with the experimental one (in both position and intensity). Consequently, our search for the coiled-coil arrangement must be focused on the models with a density as uniform as possible, more precisely, with less-regular coiled-coil positions and distances. These conditions not being fulfilled by dimers or by octamers, we investigated the tetramers (two coiled coils-based oligomers). Such tetramers, which are stabilized by ionic interaction, have been observed by various techniques during the earlier stages of in vitro IF self-assembling processes.

In Fig. 8, two tetramer-based models and their corresponding scattering profiles are given. The model, consisting of seven parallel tetramers, leads to a strong peak at 28 Å. This reflection is obviously due to the repetitive distances between the rows of tetramers. Slight relative orientation changes of the tetramers did not induce any significant variations in the scattering profile. The second model is a herringbone packing, which is the other compact packing of rectangular-shaped objects (Doucet, 1979). This model, which is less periodic than the previous one, yielded a profile which is rather good; the peak at 28 Å is no longer intense. Similar conclusions were obtained with eight tetramers across the IF section.

FIGURE 8.

(A) Two tetramer-based models with parallel coiled coils. The left model consists of seven parallel oriented tetramers and the right model consists of seven tetramers assembled into a compact herringbone-type packing characterized by two tetramer orientations. (B) The corresponding calculated x-ray scattering equatorial profiles.

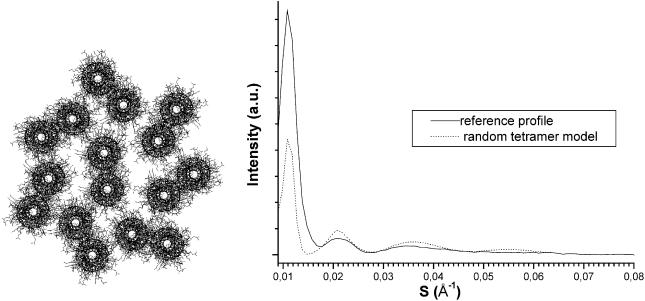

To improve this herringbone-based profile, we decided to build a model with a significant amount of disorder in the tetramer's positions and relative orientations. This randomization aimed to obtain a non-regularly ordered architecture that would not produce the extra scattering peaks. This has been achieved as follows: starting from a perfect herringbone model, we slightly modified the relative tetramer orientations and distances across the section. The shifts from the perfect herringbone-packing relative unit orientations were comprised between 5° and 15°, the distances varied slightly to avoid steric hindrance. A model built in this way and its simulated equatorial profile are shown in Fig. 9. The agreement with the experimental profile was good for the first three peaks and even for the weak fourth one.

FIGURE 9.

Randomly ordered tetramer-based herringbone packing (A), and its corresponding calculated x-ray scattering equatorial profiles (B).

The intensity discrepancy of the first peak (90 Å) is probably due to an overestimation of the IF diameter. In fact the IF diameter has been chosen in agreement with the experimentally observed values. This value may be affected by the globular end parts which slightly protrude from the rod domains (Steven, 1990) and increase the IF apparent diameter. A slightly smaller diameter that does not take these parts into account would give rise to a structure factor decreasing less rapidly from the origin, resulting in a higher intensity for the first peak.

The interference effects arising from the relative positions and orientations of the coiled coils are now nearly absent, the intensity profile mainly results from the overall circular IF cross section. There is an infinite number of such “random” transverse possibilities, but they all give rise to a very close pattern to the one given in Fig. 9. These architectures could be considered equivalent in regard to the scattering pattern although not completely identical in detailed structure.

Similar models containing eight tetramers also led to good profiles. The same models from which one tetramer located in the core has been taken out gave a poorer agreement with the experimental profile. We mention here that similar deformations were tested starting from the other presented models (Figs. 5 and 6); this did not improve the simulated profiles.

It is also worth noting that our model was made of individually nonordered IFs. This is different from a possible model based on different types of ordered IFs like the ones described in this study. This last model would give rise to scattering profiles with extra peaks because their structure factor presents several peaks that are roughly located at the same positions. The lack of these features on the experimental profile could not be due to the nature of the experiment, in particular not to an averaging over all the individual filaments. It can be noticed that the interference function between intermediate filaments (see Briki et al., 1998) does not affect the zone which is concerned by the signal originating from an IF internal order (<30 Å). The presence of a small amount of ordered units is not excluded.

DISCUSSION

A refined model of the IF architecture in hair

Our detailed analysis of the x-ray scattering equatorial features of hard α-keratin IF in hair shaft has led to the following main structural features:

The radial density across the IF section is nearly uniform.

The coiled coils are straight and not supercoiled into oligomers.

The coiled coils are probably assembled into oligomers, not into compact four coiled-coil oligomers (octamers) but more likely into two tetrameric oligomers.

The positions and orientations of the oligomers do not show any regularity.

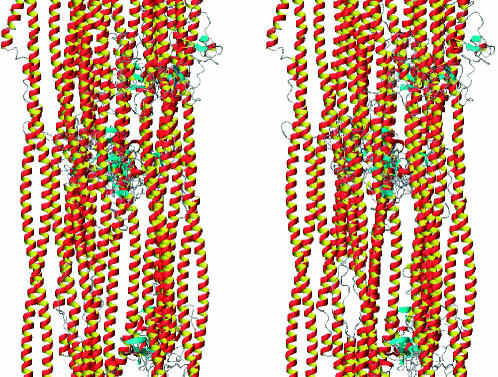

The combination of these features, related to transverse structure, with longitudinal features related to the assembly modes between neighboring coiled coils (Crewther et al., 1983; Steinert et al., 1994) allows a realistic global model of the IF architecture to be built, like the one represented in Fig. 10.

FIGURE 10.

Stereo-view of global IF architecture model built using a combination of the random tetramer transverse packing of Fig. 9 and cross-linking information based on axial association.

It must be emphasized that our conclusions, which reveal new features and allow a few structural hypotheses to be supported among the many long-debated ones, have been obtained from the analysis of a single tissue. This is of prime importance for the coherence of the results because the various structural features described in the literature for hard α-keratin were deduced from the analyses of different tissues, i.e., mainly porcupine quill and hair shaft or follicle from different species, which may exhibit some structural diversity. The other point worth mentioning is that these analyses were carried out using various analytical tools; their results are therefore not always exactly comparable. Our conclusions listed above, which were obtained on a given tissue using a single technique, must therefore be discussed and compared to the literature in the light of these two remarks.

The uniform density across the IF section

The uniform shape of the radial density across the IF was inferred from SAXS data. It is therefore low-resolution information, which indicates that the electron density does not present any strong reinforcement or depletion larger than 15–20 Å in diameter. Although this conclusion is supported by one electron microscopy observation (Steven, 1990), most microscopy observations lead to ring-core models (Filshie and Rogers, 1961; Fraser et al., 1971; Millward, 1970; Watts et al., 2002). This discrepancy could arise from the fact that the electron microscopy technique generally requires chemical sample treatment which could be nonuniform, and the interpretation of which is not devoid of artifacts due to phase-contrast effects for instance. However, artifacts are now minimized by working in cryomode and correcting images for phase-contrast. It is thus more probable that the ring-core structure is representative of in vitro conditions, i.e., in solution, and not representative of IF embedded into a dry tissue like hair shaft. Drying would induce a shrinkage of the IF organization and modify the radial density profile, as already suggested (Strelkov et al., 2003; Watts et al., 2002). In parallel, it is probable that the IF architecture is slightly origin sample-dependent; polymorphism is known to affect IF (Steven, 1990). For instance, a higher core density has been described for quill IF which is another dry tissue (Briki et al., 1998).

The absence of regularity in the transverse IF architecture

The SAXS profile is close to that given by a uniform cylinder, which indicates that no significant scattering peak arising from regular positioning of the scattering objects within the IF is present. This observation proves that the molecules are not regularly arranged across the hair IF section. The models characterized by scattering objects located symmetrically are consequently excluded; the best model consists of tetramers filling the IF section with as little regularity as possible in the distances and orientations.

One could argue that the probable nonperfect axial alignment of the successive coiled coils along the axis might smooth the projected density onto the cross section. This argument is, however, ruled out by the fact that the transverse (axial) coherence length (relevant axial length for the x-ray equatorial scattering) is smaller than the molecule length.

Another factor that could make the density projection more uniform is the contribution of the terminal parts. It has not been taken into account but its effect in the diffraction pattern should be small because of its probably more or less uniform shape. The main effect of the terminal parts, which might protrude from the IF cylinder envelope, would be to locally modify the IF diameter, resulting in a damping effect of the SAXS reflections while increasing the scattering angle.

It is important to remark that the SAXS equatorial profile analyses of hard α-keratin carried out up to now had only been limited to scattering vectors smaller than 0.05 Å−1. We show here that considering larger scattering vectors, up to 0.08 Å−1 permits the analysis to be refined because the peaks arising from interferences between oligomers often appear in the range 0.05–0.08 Å−1 whereas the experimental profiles do not display any intense peak in this range. This intermediate scattering range is therefore efficient to assess the validity of the various models.

Supercoiled versus straight dimers

This question has never been solved due to paucity of experimental evidence. In the various IF models postulated so far, this feature was set conjecturally to either of the possibilities. From the absence of any interference peak that should proceed from the regularly spaced-out coiled coils in a supercoiled structure, we can conclude here that the coiled coils are not assembled into supercoiled oligomers. The alternative geometry is an architecture with straight coiled coils, mostly parallel but with nevertheless the possibility of small-tilt angles with respect to the IF axis. It must be pointed out that this characteristic does not contradict a possible overall superhelical organization of the IF. It is perfectly realistic to imagine a helical arrangement of straight molecules, as already assumed (Watts et al., 2002).

The assembly into oligomers

The discussion about the absence of regularity in the transverse IF architecture may help in the investigation of the putative existence of oligomers. Oligomers that would lead to interference peaks, like compact octamer-based models, can be discarded. The oligomers that are compatible with the SAXS equatorial profile are those which allow molecules to be irregularly located across the IF section. Although it is not possible to point out a particular arrangement, we have shown that models with irregularly packed dimers and tetramers can yield a correct simulated x-ray profile. However, noncompact octamers, for instance four coiled coils that would be arranged along a nonclosed line, cannot be excluded. Our conclusion confirms previous in vitro observations of tetramers, and maybe octamers, as described in the introduction, but it is a direct in vivo observation and it gives further information about their mutual assembly in a hard α-keratin IF.

Implications of a nonordered organization inside hard α-keratin IF

The hard α-keratin IF architecture in hair shaft appears rather uniform across its cross section and devoid of very regular distances between molecules. Such nonregular transverse architecture is the opposite to that encountered in most biological fibers, globular protein-based fibers, like microtubule or actin, as well as chain protein-based fibers, like collagen or cellulose. However, the ring-core structure observed for quill porcupine (Briki et al., 1998) and isolated filaments (Watts et al., 2002) suggests that the architecture of hard α-keratin IF might be partially sample origin-dependent. These remarks could lead one to suppose that the formation of IF is a multistage process with similar first self-assembly stages and a last stage driven by chemical, physical, and mechanical interaction with neighboring different-tissue components (in particular with the sulfur-rich interfilament matrix), leading to a modification of the intermediate structure. The intermediate stages could consist of the formation of elongated oligomers, which afterwards would self-assemble into IF. This scenario is supported by in vitro microscopy observations of keratin oligomers (Aebi et al., 1983). Another scenario would consist of the formation of two-dimensional assemblies that would collapse in a second stage to form compact cylindrical IF (Strelkov et al., 2003). In the light of the lack of regular arrangement between molecules, this last scenario seems more probable than the first. It is likely that a folding process of a planar object could give rise to a poorly ordered object. The geometrical model of the surface lattice (Fraser et al., 1985), which was developed on the basis of chemical lateral links between molecules, could correspond to the putative two-dimensional assemblies.

In the multistage keratinization process envisaged, it is worth noting that the last stage, which gives rise to the supramolecular architecture, is probably more subject to subtle external changes than the first stages, as demonstrated by the polymorphism of IF in hair and in quill (Busson et al., 1999). It turns out therefore that studying the self-assembly process under in vitro conditions might lead to fairly representative results as regards the first stages, i.e., the oligomerization steps, but to less representative results for the last stage. Preference should be given to in vivo studies of hard α-keratin IFs in their natural tissue environment rather than to in vitro studies.

Are the structural characteristics of the other IFs the same as the ones observed for hard α-keratin in hair shaft? The answer to this question is not unique; it depends on the IF type. Other hard α-keratin IF probably presents similar architecture, as attested for instance by the paucidisperse diameter distribution, with nevertheless some variability (Briki et al., 1998). This is less sure for soft epidermal keratin IFs for which structural information is poorer. As regards β-keratin IFs, it is almost certain that their structure, which is β sheet-based, is quite different from that of α-keratin. It is more difficult to know whether the model of hard α-keratin IF can be extended to the structure of other IFs. One can nevertheless suspect differences between the various IF architectures from the observation of different assembly pathways for keratin, vimentin (Parry and Steinert, 1999), and lamins (Geisler et al., 1998; Stuurman et al., 1998). According to the sequences, longitudinal assembly may occur prior to or concurrently with lateral association, which could result in different packing. It is clear that variations of the physical and chemical conditions could also affect the in vitro assembly processes, which underlines the need for further parallel in vivo investigation to decipher the IF structures.

References

- Aebi, U., W. E. Fowler, P. Rew, and T. T. Sun. 1983. The fibrillar substructure of keratin filaments unraveled. J. Cell Biol. 97:1131–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J. C., C. N. Tyson, and H. J. Woods. 1965. The equatorial scattering of x-rays by keratin and its relation to an annular microfibril model. 3rd Int. Cong. Rech. Text. Lainière, Inst. Textile, France. I:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Birbeck, M. S. C., and E. H. Mercer. 1957. The electron microscopy of human hair follicle. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 3:203–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower, M. J., F. E. Cohen, and R. L. Dunbrack Jr. 1997. Prediction of protein side-chain rotamers from a backbone-dependent rotamer library: a new homology modeling tool. J. Mol. Biol. 267:1268–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briki, F., B. Busson, and J. Doucet. 1998. Organization of microfibrils in keratin fibers studied by X-ray scattering modelling using the paracrystal concept. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1429:57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briki, F., C. Mérigoux, F. Sarrot-Reynauld, M. Salomé, B. Fayard, J. Susini, and J. Doucet. 2003. Evidence for calcium soaps in human hair shaft revealed by sub-micrometer x-ray fluorescence. J. Phys. IV Fr. 104:337–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busson, B., and J. Doucet. 1999. Modeling α-helical coiled coils: analytic relations between parameters. J. Struct. Biol. 127:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busson, B., F. Briki, and J. Doucet. 1999. Side-chains configurations in coiled coils revealed by the 5.15-A meridional reflection on hard α-keratin X-ray diffraction patterns. J. Struct. Biol. 125:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crewther, W. G., L. M. Dowling, P. M. Steinert, and D. A. D. Parry. 1983. Structure of intermediate filaments. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 5:267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, F. H. C. 1953. The packing of α-helices: simple coiled-coils. Acta Crystallogr. 6:689–697. [Google Scholar]

- Dobb, M. G., and J. Sikorski. 1969. Fine and ultrafine structure of mammalian keratin. J. Text. Inst. 60:497. [Google Scholar]

- Doucet, J. 1979. Relation between the herringbone packing and the chain behaviour in the ordered smectic phases. J. Physiol. 40L:185–187. [Google Scholar]

- Doucet, J., and J. P. Benoit. 1987. Molecular dynamics studied by analysis of the x-ray diffuse scattering from lysozyme crystals. Nature. 325:643–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, L. M., W. G. Crewther, and A. S. Inglis. 1986. The primary structure of component 8c-1, a subunit protein of intermediate filaments in wool keratin. Relationships with proteins from other intermediate filaments. Biochem. J. 236:695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel, A., R. Eichner, and U. Aebi. 1985. Polymorphism of reconstituted human epidermal keratin filaments: determination of their mass-per-length and width by scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). J. Ultrastruct. Res. 90:323–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filshie, B. K., and G. E. Rogers. 1961. The fine structure of α-keratin. J. Mol. Biol. 3:784–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke, W. W., D. L. Schiller, and C. Grund. 1982. Protofilamentous and annular structures as intermediates during reconstitution of cytokeratin filaments in vitro. Biol. Cell. 46:257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, R. D. B., and T. P. MacRae. 1971. Structure of α-keratin. Nature. 233:138–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, R. D. B., T. P. MacRae, A. Miller, and E. Suzuki. 1964a. The quantitative analysis of fibril packing from electron micrographs. J. Mol. Biol. 9:250–252. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, R. D. B., T. P. MacRae, and A. Miller. 1964b. The coiled-coil model of α-keratin structure. J. Mol. Biol. 10:147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, R. D. B., T. P. MacRae, and G. R. Millward. 1969. Fact and artifact. J. Text. Inst. 60:498. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, R. D. B., T. P. MacRae, G. R. Millward, D. A. D. Parry, E. Suzuki, and P. A. Tulloch. 1971. The molecular structure of keratins. Appl. Polym. Symp. 18:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, R. D. B., T. P. Macrae, G. E. Rogers, and B. K. Filshie. 1963. Lipids in keratinized tissues. J. Mol. Biol. 7:90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, R. D. B., T. P. MacRae, and E. Suzuki. 1976. Structure of α-keratin microfibril. J. Mol. Biol. 108:435–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, R. D. B., T. P. MacRae, E. Suzuki, and D. A. D. Parry. 1985. Intermediate filament structure: 2. Molecular interactions in the filament. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 7:258–274. [Google Scholar]

- Geisler, N. 1993. Chemical cross-linking with disuccinimidyl tartrate defines the relative position of two antiparallel coiled-coils of the desmin protofilaments. FEBS Lett. 323:63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler, N., J. Schünemann, and K. Weber. 1992. Chemical cross-linking indicates a staggered and antiparallel protofilament of desmin intermediate filaments and characterises one higher-level complex between protofilaments. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 207:842–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler, N., J. Schunemann, K. Weber, M. Haner, and U. Aebi. 1998. Assembly and architecture of invertebrate cytoplasmic intermediate filaments reconcile features of vertebrate cytoplasmic and nuclear lamin-type intermediate filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 282:601–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, J. M. 1990. Proteins of hair and other hard α-keratins. In Cellular and Molecular Biology of Intermediate Filaments. Plenum Press, New York. 95–128.

- Giroud, A., and C. P. Leblond. 1951. The keratinization of epidermis and its derivatives, especially the hair, as shown by x-ray diffraction and histochemical studies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 53:613–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruen, L. C., and E. F. Woods. 1983. Structural studies on the microfibrillar proteins of wool. Biochem. J. 209:587–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, H., M. Haner, M. Brettel, S. A. Muller, K. N. Goldie, B. Fedtke, A. Lustig, W. W. Francke, and U. Aebi. 1996. Structure and assembly properties of the intermediate filament protein vimentin: the role of its head, rod and tail domains. J. Mol. Biol. 264:933–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T. A. 1985. Interactive computer graphics. Meth Enzymol. 115:157–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, R., R. Fourme, A. Gadet, J. Janin, C. Dumas, and D. André. 1982. Macromolecular crystallography with synchrotron radiation: Photographic data collection and polarization correction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 15:330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Millward, G. R. 1970. The structure of α-keratin microfibrils. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 31:349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry, D. A. D. 1996. Hard α-keratin intermediate filaments: an alternative interpretation of the low-equatorial x-ray diffraction pattern, and the axial disposition of putative disulphide bonds in the intra- and inter-protofilamentous networks. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 19:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry, D. A. D., L. N. Marekov, and P. M. Steinert. 2001. Subfilamentous protofibril structures in fibrous proteins: cross-linking evidence for protofibrils in intermediate filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 276:39253–39258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry, D. A. D., and P. M. Steinert. 1995. Intermediate Filament Structure. Springer Verlag, New York.

- Parry, D. A. D., and P. M. Steinert. 1999. Intermediate filaments: molecular architecture, assembly, dynamics and polymorphism. Q. Rev. Biophys. 32:99–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauling, L., R. B. Corey, and H. R. Branson. 1951. The structure of proteins: two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 37:205–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, W. R., and D. I. Lipman. 1988. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 85:2444–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, G. N., Jr. 1992. What is the pitch of the α-helical coiled coil? Proteins. 14:425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J., and C. Cohen. 1993. Pitch diversity in α-helical coiled-coils. Proteins. 15:223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, L. G., C. P. Robinson, D. T. W. MacMahon, and M. R. Rubira. 1989. The amino acid sequence of component 7c, a type II intermediate filament protein from wool. Biochem. J. 261:1015–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert, P. M., L. N. Marekov, R. D. B. Fraser, and D. A. D. Parry. 1993a. Keratin intermediate filament structure: crosslinking studies yield quantitative information on molecular dimensions and mechanism assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 230:436–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert, P. M., L. N. Marekov, and D. A. D. Parry. 1993b. Conservation of the structure of keratin intermediate filaments: molecular mechanism which different keratin molecules integrate into pre-existing keratin intermediate filaments during differentiation. Biochemistry. 32:10046–10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert, P. M., A. C. T. North, and D. A. D. Parry. 1994. Structural features of keratin intermediate filaments. J. Invest. Derm. 103:19S–24S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steven, A. C. 1990. Intermediate filament structure diversity, polymorphism and analogy to myosin. In Cellular and Molecular Biology of Intermediate Filaments. R. D. Goldman and P. M. Steinert, editors. Plenum Press, New York. 233–263.

- Strelkov, S. V., H. Hermann, and U. Aebi. 2003. Molecular architecture of intermediate filaments. Bioessays. 25:243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strelkov, S. V., H. Hermann, N. Geisler, T. Wedig, R. Zimbelmann, U. Aebi, and P. Burkhard. 2002. Conserved segments 1A and 2B of the intermediate filament dimer: their atomic structures and role in filament assembly. EMBO J. 21:1255–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuurman, N., S. Heins, and U. Aebi. 1998. Nuclear lamins: their structure, assembly and interactions. J. Struct. Biol. 122:174–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts, N. R., L. N. Jones, N. Cheng, J. S. Wall, D. A. D. Parry, and A. C. Steven. 2002. Cryo-electron microscopy of trichocyte (hard a-keratin) intermediate filaments reveals a low-density core. J. Struct. Biol. 137:109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk, K. E., V. James, and Y. Amemiya. 1995. The intermediate filament structure of human hair. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1245:392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]