Abstract

Models of closed and open channel pores of a muscle-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) channel comprising M1 and M2 segments are presented. A model of the closed channel is proposed in which hydrophobic residues of the Equatorial Leucine ring screen the oxygen domain formed by the Serine ring, thereby preventing ion flux without completely occluding the pore. This model demonstrates a high similarity with the structure derived from a recent electron microscopy study. We propose that hydrophobic residues of the Equatorial Leucine ring are retracted when the pore is open. Our models provide a possible resolution of the nAChR gate controversy. We have also obtained explanations for the complex mechanisms underlying inhibition of nAChR by philanthotoxins (PhTXs). PhTX-343, containing a spermine moiety with a charge of +3, binds deep in the pore near the Serine ring where classical open channel blockers of nAChR bind. In contrast, PhTX-(12), which has a single charged amino group is unable to reach deeply located rings because of steric restrictions. Both philanthotoxins may bind to a hydrophobic site located close to the external entrance of the pore in a region that includes residues associated with the regulation of desensitization.

INTRODUCTION

Although the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) has not yet been crystallized, compelling inferences about its tertiary and quaternary structures have been derived from extensive biophysical, biochemical, and microscopic investigations (Corringer et al., 2000). These suggest that the nAChR channel is formed by contributions from five subunits, each subunit having four (M1–M4) membrane-spanning segments. The channel is considered to be funnel-shaped with extracellular and intracellular vestibules and a pore lined by M2 residues that straddle the membrane. The N-terminal ends of M1 residues are also thought to contribute to the wall of the channel (DiPaola et al., 1990; Akabas and Karlin, 1995).

A well-characterized domain for binding noncompetitive inhibitors (NCIs) has been identified on the M2 transmembrane domains of the pore (Utkin et al., 2000). This site is located on an upper “alpha-helical component” of the pore, whereas the narrowest region of the pore is found in a lower “loop component” (Corringer et al., 2000). Channel conductance, ion selectivity, and open channel block are mechanisms associated with eight rings of homologous residues that line the pore of the channel, six of which are in the M2 segment (Fig. 1). In the N-terminal half of the M2 segments, hydrophilic Intermediate (glutamate or glutamine), Threonine, and Serine rings are exposed to the pore lumen and probably form the pore constriction, whereas hydrophobic Equatorial, Valine, and Outer Leucine rings in the C-terminal half of these segments form a funnel-like structure above the constriction. The Equatorial and Outer Leucine rings include two neighboring residues (Fig. 1, positions 41–42 and 49–50), both accessible from the pore and affecting channel properties. In addition, two rings of charged (aspartate/glutamate) residues bordering the M2 segments line the external and internal orifices of the pore.

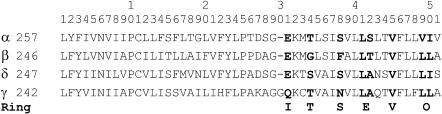

FIGURE 1.

Amino-acid sequences of M1-M2 segments of the human muscle-type nAChR channel subunits used in our models. Threonine (T), Serine (S), Equatorial (E), Valine (V), and Outer Leucine (O) rings are marked in bold.

Philanthotoxins (PhTXs) belong to a class of natural and synthetic compounds characterized by aromatic headgroups and polyamine tails and are potent NCIs of cation-selective ionotropic receptors (Usherwood, 2000; Mellor and Usherwood, 2004; Strømgaard and Mellor, 2004). Philanthotoxins were first identified in the venom of a solitary wasp where they target ionotropic glutamate receptors and nAChR in prey arthropods (Eldefrawi et al., 1988; Piek et al., 1988). They have strong structural and functional relationships to the polyamine-containing toxins present in some spider venoms (Mellor and Usherwood, 2004). Philanthotoxins have been valuable as tools for investigating the noncompetitive antagonism of ionotropic glutamate receptors and nAChR, and related polyamine-containing toxins have been useful in studies of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Inhibition of ionotropic glutamate receptors may also arise after injection of a philanthotoxin (and spermine) into an insect muscle fiber (Brundell et al., 1991), a finding that led to the discovery that endogenous, intracelluar polyamines play an important role in modulating ionotropic receptor function (Bowie and Mayer, 1995).

Initially, it was considered that philanthotoxins were exclusively open channel blockers of nAChR. Anis et al. (1990) and Choi et al. (1995) suggested that open channel block of nAChR by PhTX-343 (see Fig. 2; the numbers refer to the number of methylene groups separating amines on the polyamine) results from the interaction of the polyamine moiety with the Serine and Threonine rings lining the channel pore. However, an early review of the pharmacological properties of polyamine-containing toxins by Jackson and Usherwood (1988), although agreeing that they are open channel blockers, also suggested additional modes of action. The validity of this claim has been borne out by electrophysiological data indicating that PhTX-343 interacts with open and closed channel conformations of nAChR (Jayaraman et al., 1999). Bixel et al. (2000) showed that binding of a photosensitive philanthotoxin (N3-125I2phenyl-PhTX-343-lysine) to nAChR of Torpedo marmorata is mostly at a single class of nonallosterically interacting binding sites on the α-subunits, with a stoichiometry of two philanthotoxin molecules per receptor monomer. They also showed that some philanthotoxins displace ethidium and other classical NCIs of nAChR from its closed and desensitized conformations. They concluded that the hydrophobic headgroup of a philanthotoxin binds to the hydrophobic rings in the pore, whereas its polyamine interacts with negatively charged residues of the Intermediate ring. However, subsequent studies (Bixel et al., 2001) with the photolabile polyamine-amide, 125I-MR44, containing a long (3686) polyamine moiety indicated binding of its aromatic moiety to a region extending from αHis-186 to αLeu-199, a sequence that is extracellular to the pore and partly overlaps with one of three loops that form the agonist binding site. Complementary electrophysiological studies demonstrated that the inhibition of nAChR by MR44 is predominantly voltage independent (Brier et al., 2002).

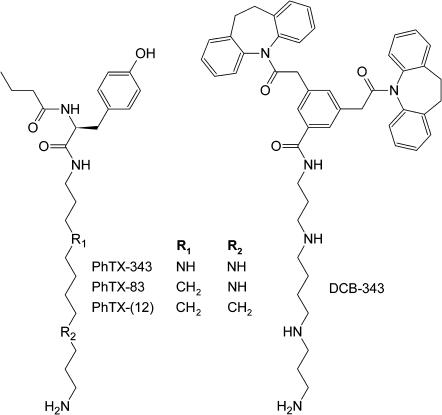

FIGURE 2.

Chemical structures of philanthotoxin analogs.

Detailed electrophysiological studies of the interactions of PhTX-343 and PhTX-(12) (dideaza-PhTX-343; Fig. 2) with a human muscle-type, embryonic nAChR were recently presented by Brier et al. (2003; see also Brier et al., 2002, Mellor et al., 2003; Strømgaard et al., 2002). These show that mechanisms of nAChR inhibition by PhTX-343 and PhTX-(12) are markedly different. The largely voltage-independent inhibition by PhTX-(12) can be explained by enhancement of nAChR desensitization, whereas PhTX-343 causes mostly voltage-dependent inhibition attributable to open channel block. The aim of this study was to analyze the binding of PhTX-343, PhTX-(12), and some other organic cations to the nAChR channel by molecular modeling using a human muscle nAChR channel model based on that of Tikhonov and Zhorov (1998) but with the inclusion of M1 helices and the M1-M2 loop. The employment of this approach has allowed us to investigate peculiarities of nAChR channel inhibition that cannot be studied directly by electrophysiology and biochemistry and to gain insight into the gate that controls transformations between open and closed channel states in this receptor.

METHODS

The overall conformational energy of a molecular system is presented as the sum of van der Waals interactions, electrostatic interactions, and torsion energies. In this study, the AMBER force field (Weiner et al., 1984) with a cutoff distance of 8.0 Å has been used. The Monte Carlo, with energy minimization, strategy (MCM; Li and Scheraga, 1987) has been used to find low-energy equilibrium conformations within internal coordinates (torsion angles and positions of free molecules). The advantage of this approach is that it provides a series of random conformation jumps and subsequent gradient minimizations to the nearest energy minimum. Energy minimization was terminated when the energy gradient became less than 1 kcal/mol/Å. MCM trajectories were calculated at T = 600 K. Conformations with the energies up to 10 kcal/mol greater than the lowest-energy conformation were counted as possible conformations of the system and stored in a stack file for further analysis. An MCM search was terminated when 5000 consecutive minimizations (for calculations of models) or 500 minimizations (for docking of an antagonist) did not lead to either a decrease in the global energy minimum or the appearance of new possible conformations in the stack. To restrict the conformational freedom of a system, flat-bottom parabolic constraint penalty functions were introduced. These functions increased the conformational energy of the system if it deviated from specified parameters. Two types of constraint were used. i), Pin constraints restricted deviation of the Cartesian coordinates of an atom from a specified point. If such a deviation was less than 1 Å, then the energy of the constraint was zero. ii), Other constraints clamped the distance between a specified atom and a plane. In this case, the mobility of the atom in the plane was not restricted. A force constant of 10 kcal/mol/Å2 was used for the constraints.

Docking of ligands was performed using an MCM energy profile strategy. The strategy was used by Tikhonov and Zhorov (1998) and by Zhorov and Bregestovski (2000). An antagonist molecule was initially placed in the channel in its optimal in vacuo conformation. The position of a ligand was fixed by imposing a plane restraint of 1-Å thickness to the terminal nitrogen. An energy profile was calculated as a series of 41 MCM searches with a 1-Å shift of the plane restraint. The zero ordinate of the profile corresponds to the position of the α-carbons of the Threonine ring of nAChR. The α-carbons of the Serine, Equatorial Leucine, Valine and Outer Leucine rings have coordinates of −5.5, −10.5, −16, and −21 Å, respectively. For each point of the profiles, the total conformational energy of the complex was partitioned for intrareceptor (channel), intraligand, and ligand-receptor energy. The latter is a sum of van der Waals and electrostatic/H-bond energies. Ligand-receptor energy was also partitioned by channel residues that allowed analysis of the contribution of residues to the binding of ligands. Intraligand and intrareceptor energies give an estimation of their energy costs for adopting optimal conformation of the complex. All calculations have been performed using the ZMM molecular modeling package (Zhorov and Lin, 2000).

RESULTS

A model of the open pore of the nAChR channel

Tikhonov and Zhorov (1998) used a consensus sequence of M2 segments to produce a model of the pore of the nAChR channel. The intrinsic feature of this model is the kink of pore-lining M2 helices between the Serine and Equatorial rings. The C-terminal ends of the M2 segments have a significant radial slope to give the extracellular half of the channel a funnel-like shape that provides free access of channel blockers to their binding sites. The N-terminal ends of the M2 segments, which are not sloped, surround the narrowest region of the channel pore, the selectivity filter. Divergence of the C-ends produces enough free space to allow the M1 segments also to contribute to the internal wall of the channel at the level of the extracellular entrance to the pore. The absence of the M1 segments in this model does not allow one to determine whether nAChR antagonists may bind to the extracellular half of the pore. Here, the model has been expanded to include the M1 segments and the M1-M2 loops and has been used to investigate the mechanisms underlying noncompetitive antagonism of nAChR by philanthotoxins and other organic cations. The conformation of the M1 segments has not yet been determined unequivocally. Cysteine scanning of M1 of α- (Akabas and Karlin, 1995) and β-subunits (Zhang and Karlin, 1997) suggests that the N-ends of M1 are not in a helical conformation. However, these parts of M1 are located in the channel vestibule and may be accessible from different sides. We have assumed that M1 is entirely helical. For the purposes of this model, it was important to fill the space between the diverging C-ends of M2s. Taking into account the assumption that M1 was helical, we treated predictions of the model at this region with special care.

For modeling of the M2 segments, we have used the C-α-carbon template from the model of Tikhonov and Zhorov (1998). The C-α-atoms of the M2 segments were fixed in positions corresponding to those pertaining in the open channel conformation of this model, and M1 helices were placed between M2s. Helical H-bonds for residues at positions 1–24, 32–39, and 41–51 were set in position by distance constraints. At the first stage of the analysis, the MCM protocol was used to find the optimal conformations of the M1 segments and the M1-M2 loops. At the next stage, the model was refined, i.e., coordinates of the C-α-atoms of the lowest-energy conformation obtained in the first stage were clamped by 1-Å width pin constraints. At this stage, only the side-chain torsions of the model were randomized, although all torsions were varied in terms of energy minimizations.

Binding of classical blockers to the open channel

Computer-based predictions of the binding of chlorpromazine, QX-222, and pentamethonium derivatives to nAChR have been described previously (Tikhonov and Zhorov, 1998). The interaction of these channel blockers with the model nAChR channel is determined by the size of their hydrophobic moiety, which binds in the region of the Equatorial ring, and by the ability of their cationic group(s) to reach the polar groups of the Serine and Threonine rings located deeper in the pore. For the extended model described herein, we have calculated the energy profiles of the open channel blockers triphenylmethylphosphonium (TPMP) and ethidium, which have been widely used for competition experiments with nAChR noncompetitive antagonists (e.g., Bixel et al., 2000). Fig. 3 illustrates the energy profiles and optimal binding modes for TPMP and ethidium. The deepest minima correspond to the interaction of both compounds with the Serine ring. For TPMP, the contributions of Serine and Equatorial rings to the interaction energy (−18.9 kcal/mol) are −10.5 and −4.2 kcal/mol, respectively. For ethidium, the contributions of Serine and Equatorial rings to the interaction energy (−18.5 kcal/mol) are −11.2 and −4.1 kcal/mol, respectively. Further penetration of these compounds into the pore is prevented by the energy barriers caused by steric hindrance at the level of the Serine ring. The binding modes for TPMP and ethidium predicted by our model agree with the experimental data for these compounds (Hucho et al., 1986) and coincide with the binding modes of chlorpromazine (Revah et al., 1990), QX-222 (Charnet et al., 1990), and tetracaine (Gallagher and Cohen, 1999).

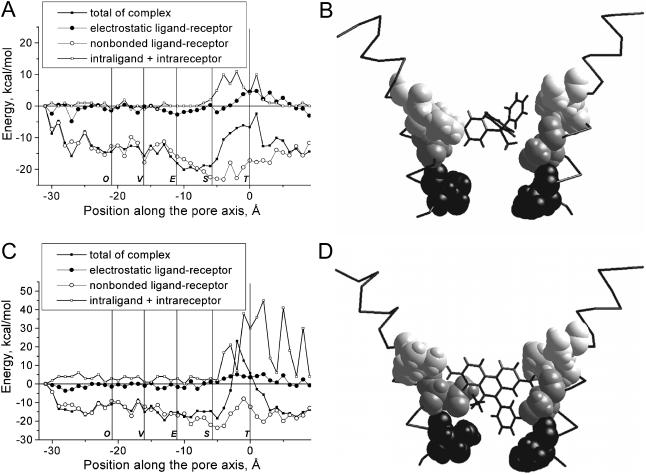

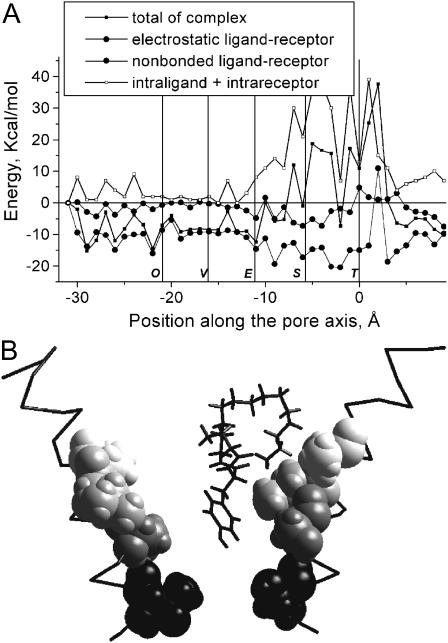

FIGURE 3.

Energy profiles (A and C) and optimal binding modes (B and D) for TPMP (A and B) and ethidium (C and D). In B and D, only the M2 segments of two nonadjacent subunits are shown. Peptide chains are presented as C-α-tracing. Residues at positions 34 (Threonine ring), 38 (Serine ring), and 41 and 42 (Equatorial ring) are space filled with decreasing density. Profiles for both TPMP and ethidium have energy minima near the Serine ring. The bulk hydrophobic groups of these compounds prevent their deeper penetration into the pore.

Access of PhTX-343 to the open pore

Tikhonov et al. (2000) have suggested that conformational properties of philanthotoxins are determined by intramolecular hydrogen bonds. Two H-bonds between the hydrogen atoms of the amine group that is closest to the uncharged moiety of PhTX-343 and the two carbonyl atoms of the headgroup give the molecule a head-and-tail structure. The PhTX-(12) molecule has only one ammonium group at the terminal position separated by 12 methylenes from its headgroup. As a result, closure of intramolecular H-bonds gives the molecule a folded shape in vacuo. Although intramolecular H-bonding has not been proven directly, and the stability of such a bond may be affected by the environment of a philanthotoxin, it has been used successfully to explain the structure-activity relationships for blockade of an insect glutamate receptor channel by philanthotoxins (Tikhonov et al., 2000) and to explain qualitatively the action of these compounds on mammalian α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor channels (Tikhonov et al., 2002).

The energy profile for PhTX-343 and its binding modes are presented in Fig. 4. Binding of PhTX-343 is similar to that of TPMP and ethidium. It has a wide minimum between the Equatorial and Threonine rings, which corresponds to two distinct binding modes (Fig. 4, B and C). At the left part of the minimum (between the Equatorial and Serine rings), the interaction energy was −27.4 kcal/mol. The terminal ammonium group of PhTX-343 interacts with the Serine ring (−10.5 kcal/mol), the middle ammonium group interacts with the polar side chains of threonine and serine residues of the Equatorial ring (position 42 in Fig. 1; −7.1 kcal/mol), and the hydrophobic moiety interacts with the Valine ring (−5.1 kcal/mol). Unlike TPMP and ethidium, which have compact shapes, the thin polyamine chain of PhTX-343 can penetrate deep into the pore and bind by another mode, corresponding to the right part of the energy minimum (between the Serine and Threonine rings in Fig. 4 A, interaction energy −22.5 kcal/mol). The terminal ammonium group of PhTX-343 binds to the Threonine ring (−6.3 kcal/mol), the middle ammonium group binds to the Serine ring (−9.2 kcal/mol), and the hydrophobic moiety interacts with leucines of the Equatorial ring (−4.1 kcal/mol). This binding mode coincides with the optimal binding of asymmetrical derivatives of pentamethonium, which are also potent blockers of the open nAChR channel (Zhorov et al., 1991; Brovtsyna et al., 1996; Tikhonov et al., 1996). When PhTX-343 penetrates deeper into the nAChR pore, it meets steric hindrances, and the energies of intraligand and intrareceptor interactions increase significantly (Fig. 4 A). Although the energy of the ligand-receptor interactions has a minimum at positive positions (deeper than the Threonine ring), further penetration of PhTX-343 into the pore beyond this ring is unlikely.

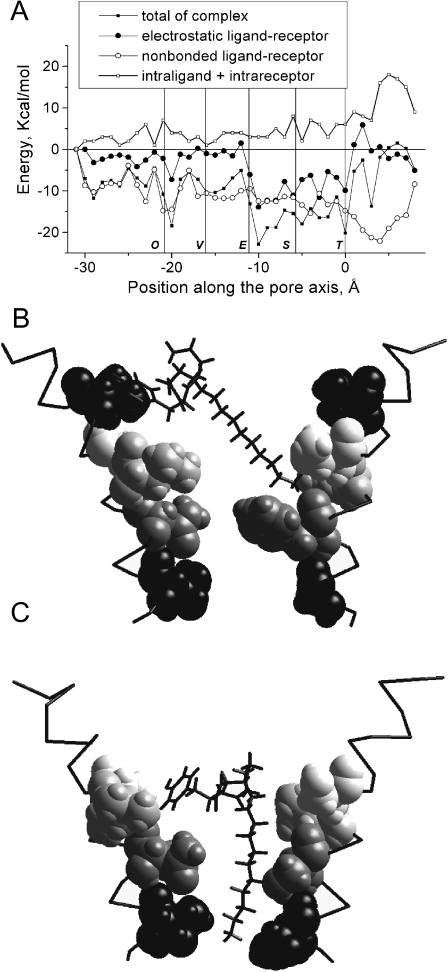

FIGURE 4.

Energy profile (A) and optimal binding modes (B and C) for PhTX-343. The binding modes are presented as in Fig. 3. The wide energy minimum between the Equatorial and Threonine rings correspond to two distinct binding modes (B and C). In B, the terminal amino group of PhTX-343 binds to the main-chain oxygen of the Serine ring, whereas its hydrophobic moiety interacts with the Valine ring (space filled, black). In C, the terminal amino group of PhTX-343 reaches the Threonine ring, the middle amino group interacts with the Serine ring, and the hydrophobic moiety interacts with the Equatorial ring.

Access of PhTX-(12) to the open pore

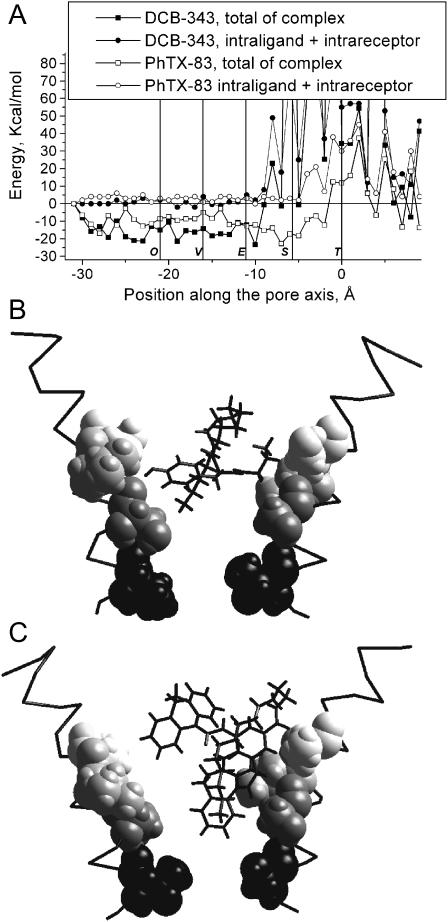

The energy profile for PhTX-(12) (Fig. 5) differs markedly from the profiles considered above. It faces a high-energy barrier beyond the Equatorial ring instead of a minimum. This barrier is due to intramolecular interactions, indicating that steric hindrances prevent the penetration of the PhTX-(12) molecule into the pore. This suggests that PhTX-(12) should not produce a voltage-dependent block of the open nAChR pore, a conclusion that concurs with the electrophysiological data of Brier et al. (2002, 2003) and Mellor et al. (2003). The only chemical difference between PhTX-343 and PhTX-(12) is the replacement of two internal ammonium groups of PhTX-343 with methylenes (PhTX-(12)). On their own, these substitutions should only reduce the ability of PhTX-(12) to interact with polar groups at the pore NCI site because PhTX-(12) still has one ammonium group, like many voltage-dependent open channel blockers of nAChR. Therefore, the energy profile of PhTX-(12), which prevents this philanthotoxin from reaching the deep NCI site in the pore, must be related to its inherent conformational properties. These properties distinguish it from PhTX-343. The conformational difference (head-and-tail versus folded structure) between PhTX-343 and PhTX-(12) is responsible for the different energy profiles of these molecules. The polyamine tail of PhTX-343 has a diameter of ∼5 Å, which means that it could enter the nAChR pore to reach polar residues located in the deep narrow part of the channel. In contrast, the folded conformation of PhTX-(12) has a diameter of 10–14 Å, which means that it would less readily enter the narrow part of the pore, and its single ammonium group would not interact with the channel wall because it is involved in forming an intramolecular H-bond.

FIGURE 5.

Energy profile (A) and optimal binding mode (B) for PhTX-(12). The binding mode is presented as in Fig. 3. The folded structure of the PhTX-(12) molecule prevents it from reaching the Serine ring. As a result, its energy profile has a barrier between the Equatorial and Serine rings instead of a minimum (see Figs. 3 and 4).

Binding of other philanthotoxins to the open pore

The data presented above suggest the size/shape of a philanthotoxin determines its level of penetration into the nAChR pore. To further test this suggestion, we have modeled the binding of PhTX-83 (Strømgaard et al., 1999; Mellor et al., 2003) and the dihydrocarbamazepine derivative DCB-343 (Bixel et al., 2000). The first compound is an intermediate between PhTX-343 and PhTX-(12) (Fig. 2), i.e., it has two ammonium groups, and, in its optimal in vacuo conformation, the headgroup with intramolecular H-bonds is more massive than that of PhTX-343 and the polyamine chain is shorter with only one free ammonium group. Its energy profile (Fig. 6) resembles those for TPMP and ethidium, i.e., its deepest minimum is located between the Equatorial and Serine rings, which are the main contributors to the interaction energy. DCB-343 has bulky moieties in its headgroup (Fig. 2) that partly screen its polyamine chain and prevent the penetration of the molecule deep into the pore. Like PhTX-(12), it encounters steric hindrances at the level of the hydrophobic rings (Fig. 6), and, therefore, the ability of its terminal amino group to interact with the Serine ring may be prevented. The characteristics of these energy profiles are in agreement with experimental data demonstrating a weak voltage-dependent block by DCB-343, and the channel blocking characteristics of PhTX-83 being an intermediate between that of PhTX-343 and PhTX-(12) (Mellor et al., 2003). Thus, the size/shape of a philanthotoxin is a major determinant of binding to the voltage-dependent NCI site.

FIGURE 6.

Energy profiles (A) and optimal binding modes of PhTX-83 (B) and DCB-343 (C). Binding modes are presented as in Fig. 3. The energy profile and binding mode of PhTX-83 are similar to those of TPMP and ethidium (see Fig. 3). The bulky moiety of DCB-343 does not allow it to penetrate deeply into the pore (positive energy after the Equatorial ring), which makes its profile similar to that of PhTX-(12) (see Fig. 5).

The importance of free, main-chain oxygens of the Serine ring and possible mechanisms of channel activation

Binding to the deep NCI site between Threonine and Serine rings is typical for open channel blockers of nAChR. Considerations of the antagonism of the closed and open channel conformations of nAChR necessarily involve the problem of channel gating. Unfortunately, there is no commonly accepted view on the nature of the nAChR channel gate, e.g., where the gate is located and, more generally, the structural difference between open and closed channel conformations. A model based on electron microscopy data (Unwin, 1995; Miyazawa et al., 1999) proposes that the leucine residues of the Equatorial ring face inwards and occlude the pore when the channel is closed but not when it is open. Mutations of these leucines significantly affect channel gating (Filatov and White, 1995; Labarca et al., 1995). Nevertheless, the Threonine ring, which is deeply located in the channel pore, remains highly accessible to some extracellular ligands when the channel is closed (Wilson and Karlin, 1998), suggesting, perhaps, that the location of the gate is deeper in the pore. However, this suggestion seemingly conflicts with many mutagenesis data and with the state-dependent binding of open channel blockers to the Serine and Equatorial rings (Hucho et al., 1986; Revah et al., 1990; Gallagher and Cohen, 1999). Recently, Yu et al. (2003) proposed that channel activation involves both the opening of the deeply located resting gate and the removal of an obstruction formed by the outer end of M1 that retards entry of blockers into the closed channel. However, electron microscopy with resolution extended to 4 Å suggests that the resting gate is formed by the Equatorial and Valine rings, which create hydrophobic rings impermeable to inorganic ions (Miyazawa et al., 2003).

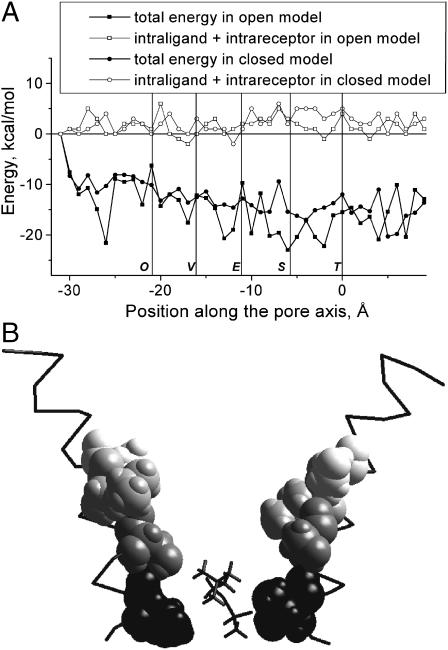

Our open channel model suggests that accessibility to the Serine ring is important for the binding of blockers. According to the energy profiles, at the initial portion of the minimum, the positively charged groups of open channel blockers interact with main-chain oxygens of the Serine ring. Because of the kink in the M2 segments, these atoms are not involved in the helical H-bond network and face into the pore. Tikhonov and Zhorov (1998) proposed that gating of the nAChR channel is due to local conformational changes at the flexible region of the kink. Leucine residues of the Equatorial ring could adopt a number of conformations, with their side chains projecting either toward or away from the pore. To test further how conformational changes at the kink region might affect the interaction of M2 residues with intrapore particles, we imposed additional axis constraints on our model, forcing the side chains of leucine residues of the Equatorial ring to face inwards. The MCM search with these constraints gave a structure that may correspond to the closed state of nAChR. A comparison of the kink region in the open and closed channel conformations of nAChR is presented in Fig. 7. There are two effects of projecting the leucine side chains into the pore: the pore diameter is reduced by hydrophobic leucine side chains; and main-chain oxygens of the Serine ring are screened, thus making them inaccessible from the pore. The important feature of this closed state model is that the side chains of leucines of the Equatorial ring do not occlude the pore completely.

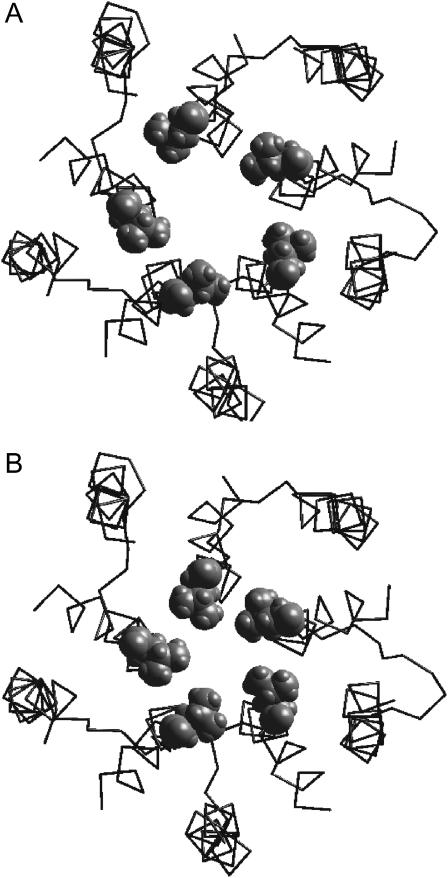

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of open (A) and closed (B) state models of the nAChR pore. In the open state model, leucines of the Equatorial ring (space filled) are projected sideways. In the closed state model, the side chains of leucines face the pore but do not completely occlude it.

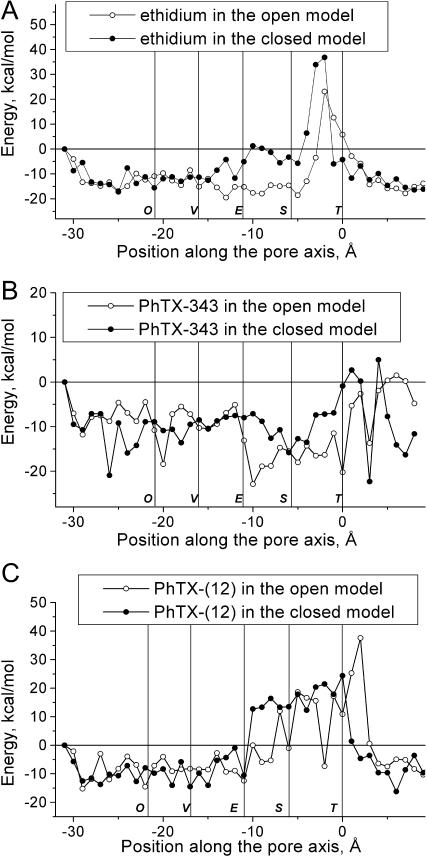

Fig. 8 compares the energy profiles for ethidium, PhTX-343, and PhTX-(12) in the open and closed channel models. For ethidium and PhTX-343, the profiles are significantly different near the Serine ring. For ethidium, the energy barrier is shifted by ∼15 Å to a shallower position in the pore (Fig. 8 A). In the closed state model, ethidium does not have a minimum at the Serine ring. Because of its reduced diameter at the Equatorial ring, the pore cannot accommodate an ethidium molecule, and, as a result, this open channel blocker cannot reach its binding site located deeper in the pore. The energy profile for PhTX-343 lacks a deep minimum between the Equatorial and Serine rings due to its much smaller electrostatic interaction with the channel (Fig. 8 B). In the open but not in the closed state model, the main-chain oxygens of the Serine ring provide electrostatic interactions for open channel blockers. Thus, differences between the profiles of open channel blockers in the open and close state models agree with their state-dependent actions. For PhTX-(12), the minor difference between profiles in the open and closed channel models is the location of the initial part of the energy barrier (Fig. 8 C); it faces a high energy barrier at the equatorial ring in the closed channel model, whereas in the open channel model it can partially enter the equatorial ring. Other than this, PhTX-(12) can bind equally well in the upper part of the pore in both closed and open states.

FIGURE 8.

Comparison of the energy profiles for ethidium (A), PhTX-343 (B), and PhTX-(12) (C) in the open and closed state models. For ethidium and PhTX-343, binding between the Equatorial and Serine rings in the closed state model is less favorable. For PhTX-(12) the only minor difference is that the high energy barrier occurs at the equatorial site in the closed channel model, whereas it can partially enter this ring in the open channel model.

The main argument against locating the nAChR channel gate at the kink region is based on data from cysteine scanning (Wilson and Karlin, 1998), which show the accessibility of methanethiosulfonate (MTS) reagents to the Threonine ring even in the closed channel state. However, the cysteine-scanning approach raises the question of how a reagent molecule can negotiate the closed channel gate. If the pore in the closed channel is occluded sterically, such a molecule should be unable to reach substituted cysteines below the gate. However, if we assume that the energy barrier preventing ion flow in the closed channel state is not steric but hydrophobic (i.e., in the closed channel state, the oxygen ring that is critical for the dehydration of permeant ions is screened by hydrophobic chains), a small organic reagent, with an unstable water shell, could permeate the channel. To test this, we have calculated the energy profiles for 2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl MTS (MTSET) in the open and closed state models. The results are presented in Fig. 9. Both profiles are similar without any systematic differences. There are no significant energy barriers, indicating that MTSET can permeate the channel pore, even in its closed state. The deepest minimum is located between the Serine and Threonine rings, which agrees with the high accessibility of the Threonine ring. Thus, the energy profiles for the open and closed state models show significant differences for open channel blockers, ethidium, and PhTX-343 but no significant differences for PhTX-(12) and MTSET.

FIGURE 9.

Energy profiles of MTSET in the open and closed state models (A) and its optimal binding mode in the open state model (B). The MTSET molecule does not meet a steric barrier and can, therefore, reach the deeply located Threonine ring. There is no significant difference between the profiles for MTSET in the open and closed state models.

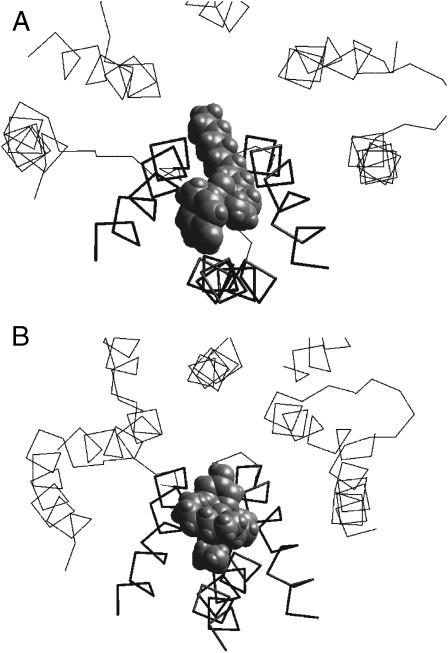

Noncompetitive antagonism through binding of philanthotoxins to the extracellular end of the channel pore

Energy profiles for philanthotoxins have minima at the extracellular half of the pore (Figs. 4 and 5). The depth of the minima for PhTX-343 and PhTX-(12) at this site are comparable with the depth of the main minimum for PhTX-343 at the open channel blocking site. At this putative outer site, philanthotoxins interact with the N-terminal ends of the M1 segments and with the C-terminal ends of the M2 segments. The site has the shape of a slot with walls formed by adjacent M2 segments and with the bottom formed by an M1 segment (Fig. 10). For PhTX-343 and PhTX-(12) the main contributors to the interaction energy are aromatic residues at positions 2 and 3 (Fig. 1) and hydrophobic Valine and Outer Leucine rings. The region is close to the N-terminal end of M1 and the C-terminal end of M2, and thus other parts of nAChR, in addition to the M1 and M2 segments, may contribute to this binding site for philanthotoxins. For instance, the region αHis-186 to αLeu-199, which is labeled by 125I-MR44 (Bixel et al., 2001), could be involved. Unfortunately, in the absence of high-resolution data on the topography of the extracellular domains of nAChR, it would be premature to include them in the model. Also, we cannot claim to know how the binding of philanthotoxins to this site antagonizes nAChR. Since the site is only marginally in the membrane electric field, any such antagonism should be largely voltage independent. Indeed, compounds like PhTX-(12) and DCB-343 that can bind only to this site in our model produce only voltage-independent inhibition. It is noteworthy that this site is formed mainly by hydrophobic residues. Recent data on PhTX-(12) derivatives have demonstrated that hydrophobicity is important for voltage-independent inhibition by philanthotoxins (Strømgaard et al., 2000).

FIGURE 10.

Binding of PhTX-343 (A) and PhTX-(12) (B) to the extracellular region of the nAChR channel. Compounds bind to a slot formed by diverging M2 segments, with the M1 segment filling space between them.

DISCUSSION

Electrophysiological data suggest that inhibition of nAChR by PhTX-343 has voltage-dependent and voltage-independent components (Jayaraman et al., 1999; Mellor et al., 2003; Brier et al., 2002, 2003), whereas inhibition by PhTX-(12) is largely voltage independent (Mellor et al., 2003; Brier et al., 2002, 2003; Strømgaard et al., 2002). Here, we have designed molecular models of the nAChR channel using a molecular mechanics approach and have tested them using these and other experimental data. We have shown that the shape/size of philanthotoxins determines their binding preferences. Thus, the modes of inhibition may be successfully predicted by the models. It should be noted that the α-carbon template of M2 segments of the open channel model of Tikhonov and Zhorov (1998) was not modified to fit the new experimental data. This template was also successfully used by Zhorov and Bregestovski (2000) for modeling the ion channel of the related glycine receptor and its interaction with intrapore ligands. A new feature of the model reported herein is the inclusion of M1 segments, which has enabled the discovery of a second potential NCI binding site for philanthotoxins that is located near the extracellular orifice of the pore.

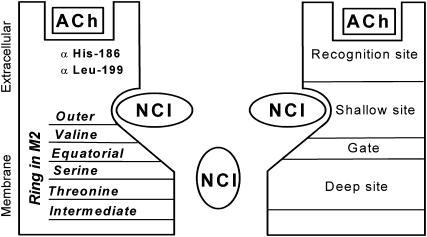

The organization of two (shallow and deep) NCI binding sites in the nAChR channel, estimated from our experimental and modeling studies of philanthotoxin action, is presented in Fig. 11. The deep NCI site is a classical binding site for open channel blockers. It is located in the narrow portion of the pore and lined mainly by polar side chains of Serine and Threonine rings. The site is below the activation gate formed by the Equatorial ring and, therefore, binding at this site is state dependent. The shallow NCI site is formed by hydrophobic residues of the C-ends of M2 segments at the wide extracellular part of the channel. Compounds bound at this site could invoke voltage-independent inhibition. Parts of the extracellular loops of nAChR that are involved in the agonist recognition are likely to contribute to this site. The important feature of our model is the close spatial location of the two sites meaning that compounds exhibiting high affinity for the shallow site could inhibit access of an open channel blocker to the deep site. We have suggested that PhTX-(12) cannot bypass the Equatorial ring even when the nAChR channel is open. Interestingly, the mutagenesis of residues 41 and 42 (Fig. 1) at the Equatorial ring strongly affects activation (Labarca et al., 1995; Filatov and White, 1995) and desensitization (Matsushima et al., 2002). Therefore, the interaction of philanthotoxins, in particular PhTX-(12) with the Equatorial ring, might also influence desensitization, as suggested by the electrophysiological data of Brier et al. (2003).

FIGURE 11.

Proposed organization of NCI binding sites in the pore of nAChR. Binding of NCIs to the deep and shallow sites corresponds to voltage-dependent and voltage-independent inhibition, respectively. At the level of the shallow site, the nAChR pore is wide enough to accommodate two NCI molecules.

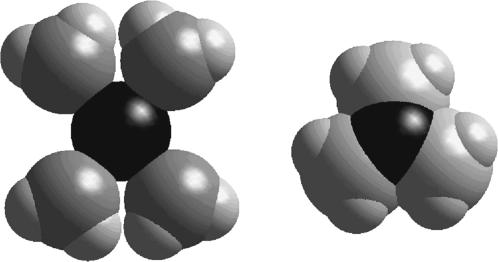

In earlier models of the closed nAChR channel (Tikhonov and Zhorov, 1998), pore-facing side chains of leucines of the Equatorial ring almost occlude the pore. As a result, it was not possible to explain the accessibility of deeper sites in the pore by MTS reagents. Here, we demonstrate that state-dependent binding of ligands does not require the steric occlusion of the closed channel, and, thus, we avoid contradictions between cysteine scanning data and other experimental data. We have shown that the conformational change during channel gating may involve screening of an oxygen ring by hydrophobic side chains, which makes dehydration of a permeant ion critically unfavorable. The hypothesis of a hydrophobic channel gate was recently discussed by Beckstein et al. (2003). It is possible for small organic reagents to slowly bypass the hydrophobic channel gate when it is closed. It is noteworthy that the dimensions of MTSET are smaller than those of hydrated inorganic ions (Fig. 12). In the Shaker potassium channel, residues known to be behind the closed gate are also accessible for MTSET, albeit at a much slower rate than in the open state (Liu et al., 1997). The important test of this idea is to simulate ion passage through the open and closed state models. This will require the employment of a molecular dynamics approach instead of the Monte Carlo minimization method used in this work. Also, such simulations will need water molecules in the channel.

FIGURE 12.

Comparison of dimensions of a hydrated sodium ion and a trimethylammonium group. The latter is significantly smaller and can access more narrow hydrophobic regions where dehydration of the sodium ion is unfavorable.

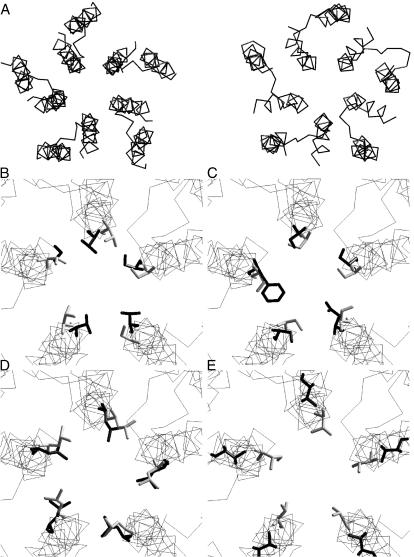

Recently, two models of the nAChR channel have been presented. Based on the mapping of the quinacrine binding site by cysteine-substituted mutants, Yu et al. (2003) have proposed a model of open channel blockade. Despite differences in structural details compared to our model and an alternative explanation for the gating, the proposed binding mode of quinacrine to the open channel is similar to our previous study (Tikhonov and Zhorov, 1998) and the results presented herein. Miyazawa et al. (2003) presented a model of the closed nAChR based on electron microscopy. Since coordinates of the model are accessible from the Protein Data Bank (accession code 1OED), we compared this model with our closed channel model. The comparison is presented in Fig. 13. The general architecture of the two models is similar, i.e., position, orientation, and helical conformation of M1s and disposition of M2s (Fig. 13 A). More particularly, the geometry of the Threonine, Serine, and Equatorial rings are practically identical (Fig. 13, B–D), these rings being especially important for binding of channel blockers. Thus, our model of the narrow part of the nAChR channel originally proposed in 1998 and based mainly on data from channel blockade agrees well with modern electron microscopy data. The model of Miyazawa et al. (2003) has a smaller kink of the M2 segments and, as a result, significantly smaller dimensions of the Valine ring (Fig. 13 E). The latter is not surprising because our closed channel model was built from the open channel model to simulate a minimal conformational transition that can cause channel closure. Thus, the main difference between the models is that the model of Miyazawa et al. (2003) has two rings of pore-facing hydrophobic residues, whereas our model has only one such ring.

FIGURE 13.

Comparison of the closed state model with the model proposed by Miyazawa et al. (2003; PDB accession code 1OED). (A) Top view. In the model of Miyazawa et al. (2003) (left), only M1 and M2 segments are shown. (B–E) Superimposition of the models with Threonine (B), Serine (C), Equatorial (D), and Valine (E) rings shown as sticks (the model of Miyazawa et al. (2003) is colored gray). Threonine, Serine, and Equatorial rings have practically the same conformations. Dimensions of the Valine ring are smaller in the model of Miyazawa et al. (2003) because of the smaller kink of M2 segments.

A limitation of our models is that they are not based on high-resolution data. We also ignore intrapore water molecules and entropy effects. Therefore, we cannot quantitatively predict the binding free energies of ligands with respect to the two NCI binding sites. The purpose of this work was not to determine precise binding energies but to provide an energy scoring function that allows us to determine steric barriers and possible binding sites. The latter correspond to optimal van der Waals contacts and complementary electrostatic/H-bond interactions between a ligand molecule and a channel model.

Although molecular models based on indirect structural data have often been shown subsequently to contain detail imperfections, they have provided important insights to the structural and molecular determinants of ligand action. In this context, they have been especially valuable for understanding the behavior of philanthotoxins, despite the high flexibility and complex modes of action of these nAChR NCIs. They have enabled us, first, to suggest a new scheme for NCI site localizations in the nAChR channel and, second, to offer a possible resolution of the nAChR gate controversy.

Acknowledgments

Coordinates of the models are available by request.

This work was supported by a Collaborative Research Initiative grant (067496) from the Wellcome Trust, UK, awarded jointly to our laboratories.

References

- Akabas, M. H., and A. Karlin. 1995. Identification of acetylcholine receptor channel lining residues in the M1 segment of the alpha subunit. Biochemistry. 34:12496–12500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anis, N., S. Sherby, R. Goodnow, M. Niwa, K. Konno, T. Kallimopoulos, R. Bukownik, K. Nakanishi, P. Usherwood, A. Eldefrawi, and M. Eldefrawi. 1990. Structure-activity relationships of philanthotoxin analogs and polyamines on N-methyl-d-aspartate and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 254:764–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstein, O., P. C. Biggin, P. Bond, J. N. Bright, C. Domene, A. Grottesi, J. Holyoake, and M. S. Sansom. 2003. Ion channel gating: insights via molecular simulations. FEBS Lett. 555:85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixel, M. G., M. Krauss, Y. Liu, M. L. Bolognesi, M. Rosini, I. S. Mellor, P. N. R. Usherwood, C. Melchiorre, K. Nakanishi, and F. Hucho. 2000. Structure-activity relationship and site of binding of polyamine derivatives at the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixel, M. G., C. Weise, M. L. Bolognesi, M. Rosini, M. J. Brierley, I. R. Mellor, P. N. R. Usherwood, C. Melchiorre, and F. Hucho. 2001. Location of the polyamine binding site in the vestibule of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel. J. Biol. Chem. 276:6151–6160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie, D., and M. L. Mayer. 1995. Inward rectification of both AMPA and kainate subtype glutamate receptors generated by polyamine-mediated ion-channel block. Neuron. 15:453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brier, T. J., I. R. Mellor, D. B. Tikhonov, I. Neagoe, Z. Y. Shao, M. J. Brierley, K. Strømgaard, J. W. Jaroszewski, P. Krogsgaard-Larsen, and P. N. R. Usherwood. 2003. Contrasting actions of philanthotoxin-343 and philanthotoxin-(12) on human muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 64:954–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brier, T., I. R. Mellor, and P. N. R. Usherwood. 2002. Allosteric and steric interactions of polyamines and polyamine-containing toxins with nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. In Perspectives in Molecular Toxinology. A. Ménez, editor. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, UK. 281–297.

- Brovtsyna, N. B., D. B. Tikhonov, O. B. Gorbunova, V. E. Gmiro, S. E. Serduk, N. Y. Lukomskaya, L. G. Magazanik, and B. S. Zhorov. 1996. Architecture of the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel at the binding site of bis-ammonium blockers. J. Membr. Biol. 152:77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundell, P., R. Goodnow, Jr., C. J. Kerry, K. Nakanishi, H. L. Sudan, and P. N. R. Usherwood. 1991. Quisqualate-sensitive glutamate receptors of the locust Schistocera gregaria are antagonised by intracellularly-applied philanthotoxin and spermine. Neurosci. Lett. 131:196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnet, P., C. Labarca, R. J. Leonard, N. J. Vogelaar, L. Czyzyk, A. Gouin, N. Davidson, and H. A. Lester. 1990. An open-channel blocker interacts with adjacent turns of alpha helices in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Neuron. 4:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. K., A. G. Kalivretenos, P. N. R. Usherwood, and K. Nakanishi. 1995. Labeling studies of photolabile philanthotoxins with nicotinic acetylcholine receptors - mode of interaction between toxin and receptor. Chem. Biol. 2:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corringer, P. J., N. Le Novère, and J. P. Changeux. 2000. Nicotinic receptors at the amino acid level. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 40:431–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPaola, M., P. N. Kao, and A. Karlin. 1990. Mapping the alpha-subunit site photolabeled by the noncompetitive inhibitor [3H] quinacrine azide in the active state of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 265:11017–11029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldefrawi, A. T., M. E. Eldefrawi, K. Konno, N. A. Mansour, K. Nakanishi, E. Oltz, and P. N. R. Usherwood. 1988. Structure and synthesis of a potent glutamate receptor antagonist in wasp venom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 85:4910–4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filatov, G. N., and M. M. White. 1995. The role of conserved leucines in the M2 domain of the acetylcholine receptor in channel gating. Mol. Pharmacol. 48:379–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, M. J., and J. B. Cohen. 1999. Identification of amino acids of the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor contributing to the binding site for the noncompetitive antagonist [3H]tetracaine. Mol. Pharmacol. 56:300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucho, F., W. Oberthur, and F. Lottspeich. 1986. The ion channel of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is formed by the homologous helices M-II of the receptor subunits. FEBS Lett. 205:137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, H., and P. N. R. Usherwood. 1988. Spider toxins as tools for dissecting elements of excitatory amino acid transmission. Trends Neurosci. 11:278–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman, V., P. N. R. Usherwood, and G. P. Hess. 1999. Inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by philanthotoxin-343: kinetic investigations in the microsecond time region using a laser-pulse photolysis technique. Biochemistry. 38:11406–11414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarca, C., M. W. Nowak, H. Y. Zhang, L. X. Tang, P. Deshpande, and H. A. Lester. 1995. Channel gating governed symmetrically by conserved leucine residues in the M2 domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 376:514–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. Q., and H. A. Scheraga. 1987. Monte-Carlo-minimization approach to the multiple-minima problem in protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:6611–6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., M. Holmgren, M. E. Jurman, and G. Yellen. 1997. Gated access to the pore of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Neuron. 19:175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima, N., S. Hirose, H. Iwata, G. Fukuma, M. Yonetani, C. Nagayama, W. Hamanaka, Y. Matsunaka, M. Ito, S. Kaneko, A. Mitsudome, and H. Sugiyama. 2002. Mutation (Ser284Leu) of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha 4 subunit associated with frontal lobe epilepsy causes faster desensitization of the rat receptor expressed in oocytes. Epilepsy Res. 48:181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, I. R., T. J. Brier, F. Pluteanu, K. Strømgaard, A. Saghyan, N. Eldursi, M. J. Brierley, K. Anderson, J. W. Jaroszewski, P. Krogsgaard-Larsen, and P. N. R. Usherwood. 2003. Modification of the philanthotoxin-343 polyamine moiety results in different structure-activity profiles at muscle nicotinic ACh, NMDA and AMPA receptors. Neuropharmacology. 44:70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, I. R., and P. N. R. Usherwood. 2004. Targeting ionotropic receptors with polyamine-containing toxins. Toxicon. 43:493–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa, A., Y. Fujiyoshi, M. Stowell, and N. Unwin. 1999. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4.6 Å resolution: transverse tunnels in the channel wall. J. Mol. Biol. 288:765–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa, A., Y. Fujiyoshi, and N. Unwin. 2003. Structure and gating mechanism of the acetylcholine receptor pore. Nature. 423:949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piek, T., R. H. Fokkens, H. Karst, C. Kruck, A. Lind, J. Van Marle, T. Nakajima, N. M. M. Nibbering, H. Shinozaki, W. Spanjer, and Y. C. Tong. 1988. Polyamine like toxins–a new class of pesticides? In Neurotox '88: Molecular Basis of Drug & Pesticide Action. G. G. Lunt, editor. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 61–76.

- Revah, F., J. L. Galzi, J. Giraudat, P. Y. Haumont, F. Lederer, and J. P. Changeux. 1990. The noncompetitive blocker [3H]chlorpromazine labels three amino acids of the acetylcholine receptor gamma subunit: implications for the alpha-helical organization of regions MII and for the structure of the ion channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87:4675–4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strømgaard, K., I. Bjornsdottir, K. Andersen, M. J. Brierley, S. Rizoli, N. Eldursi, I. R. Mellor, P. N. R. Usherwood, S. H. Hansen, P. Krogsgaard-Larsen, and J. W. Jaroszewski. 2000. Solid phase synthesis and biological evaluation of enantiomerically pure wasp toxin analogues PhTX-343 and PhTX-12. Chirality. 12:93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strømgaard, K., M. J. Brierley, K. Andersen, F. A. Sløk, I. R. Mellor, P. N. R. Usherwood, P. Krogsgaard-Larsen, and J. W. Jaroszewski. 1999. Analogues of neuroactive polyamine wasp toxins that lack inner basic sites exhibit enhanced antagonism toward a muscle-type mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J. Med. Chem. 42:5224–5234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strømgaard, K., and I. Mellor. 2004. AMPA receptor ligands: synthetic and pharmacological studies of polyamines and polyamine toxins. Med. Res. Rev. 24:589–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strømgaard, K., I. R. Mellor, K. Andersen, I. Neagoe, F. Pluteanu, P. N. R. Usherwood, P. Krogsgaard-Larsen, and J. W. Jaroszewski. 2002. Solid-phase synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of analogues of PhTX-12 - a potent and selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 12:1159–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov, D. B., L. G. Magazanik, I. R. Mellor, and P. N. R. Usherwood. 2000. Possible influence of intramolecular hydrogen bonds on the three-dimensional structure of polyamine amides and their interaction with ionotropic glutamate receptors. Receptors Channels. 7:227–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov, D. B., I. R. Mellor, P. N. R. Usherwood, and L. G. Magazanik. 2002. Modeling of the pore domain of the GluR1 channel: homology with K+ channel and binding of channel blockers. Biophys. J. 82:1884–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov, D. B., N. N. Potapyeva, V. E. Gmiro, B. S. Zhorov, and L. G. Magazanik. 1996. A proposed mechanism of binding pentamethylene-bisammonium derivatives to the muscle nicotinic cholinoreceptor ionic channel. Membr. Cell Biol. 10:199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov, D. B., and B. S. Zhorov. 1998. Kinked-helices model of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel and its complexes with blockers: simulation by the Monte Carlo minimization method. Biophys. J. 74:242–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin, N. 1995. Acetylcholine receptor channel imaged in the open state. Nature. 373:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usherwood, P. N. R. 2000. Natural and synthetic polyamines: modulators of signalling proteins. Farmaco. 55:202–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utkin, YuN, V. I. Tsetlin, and F. Hucho. 2000. Structural organization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Membr. Cell Biol. 13:143–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, S. J., P. A. Kollman, D. A. Case, U. C. Singh, C. Ghio, G. Alagona, S. Profeta, and P. Weiner. 1984. A new force-field for molecular mechanical simulation of nucleic-acids and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106:765–784. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G. G., and A. Karlin. 1998. The location of the gate in the acetylcholine receptor channel. Neuron. 20:1269–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y., L. Shi, and A. Karlin. 2003. Structural effects of quinacrine binding in the open channel of the acetylcholine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:3907–3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H., and A. Karlin. 1997. Identification of acetylcholine receptor channel-lining residues in the M1 segment of the beta-subunit. Biochemistry. 36:15856–15864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhorov, B. S., and P. D. Bregestovski. 2000. Chloride channels of glycine and GABA receptors with blockers: Monte Carlo minimization and structure-activity relationships. Biophys. J. 78:1786–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhorov, B. S., N. B. Brovtsyna, V. E. Gmiro, N. Y. Lukomskaya, S. E. Serdyuk, N. N. Potapyeva, L. G. Magazanik, D. E. Kurenniy, and V. I. Skok. 1991. Dimensions of the ion channel in neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine-receptor as estimated from analysis of conformation-activity relationships of open-channel blocking drugs. J. Membr. Biol. 121:119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhorov, B. S., and S. X. Lin. 2000. Monte Carlo-minimized energy profile of estradiol in the ligand-binding tunnel of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: atomic mechanisms of steroid recognition. Proteins. 38:414–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]