Abstract

The red antenna states of the external antenna complexes of higher plant photosystem I, known as LHCI, have been analyzed by measurement of their preequilibrium fluorescence upon direct excitation at 280 K. In addition to the previously detected F735 state, a hitherto undetected low-energy state with emission maximum around 713 nm was observed. The 280 K bandwidths (FWHM) are 55 nm for the F735 state and ∼27 nm for the F713-nm state, much greater than for non-red-shifted antenna chlorophylls. The origin absorption band for the F735-nm state was directly detected by determination of its excitation (action) spectrum and lies at 709–710 nm. The absorption spectrum for F735, calculated using the Stepanov expression, closely overlaps the excitation spectrum, indicating that the very large Stokes shift (25 nm) is due to vibrational relaxation within the excited-state manifold and solvent effects can be excluded. Fluorescence anisotropy measurements, with direct excitation of F735, indicate that the transition dipoles of the two red states are parallel. Similar experiments performed in the long-wavelength absorbing tail of PSI-LHCI indicate the presence of emission state(s) that are red-shifted with respect to F735 of isolated LHCI. It is suggested that these are brought about by interactions between the complexes in PSI-LHCI, which occur in some yet undefined way, and which are broken upon solubilization of the component parts.

INTRODUCTION

Photosystem I of higher plants is a supramolecular pigment/protein complex, localized in the nonappressed regions of thylakoid membranes. The complex binds the primary electron donor chlorophylls, known as P700, and can photoreduce ferredoxin using plastocyanin and cytochromes as secondary electron donors (Bruce and Malkin, 1988). The complex has two moieties, which are the central chlorophyll a binding core complex and a peripheral antenna that consists of four different LHCI chlorophyll a/b binding proteins. The core complex binds ∼90–100 chlorophyll a and probably ∼20 β-carotene molecules (Jennings et al., 1996; Jordan et al., 2001), as well as P700 and the primary acceptors A0 and A1 at the interface between the two homologous subunits (Golbeck, 2003). The LHCI complexes seem to be arranged on one side of the core (Boekema et al., 2001; Ben-Shem et al., 2003) and, taken together, they bind ∼80–100 chlorophyll a + b molecules and 20 xanthophylls according to biochemical data (Bassi and Simpson, 1987), and ∼55–60 according to crystallographic data (Ben-Shem et al., 2003). There are also large discrepancies concerning the chlorophyll binding stoichiometry determined from biochemical (10 per polypeptide; Croce and Bassi, 1998) and crystallographic data (14–15 per polypeptide; Ben-Shem et al., 2003), and between the number of Lhca polypeptides bound to each PSI core (10 and 4, respectively). Thus, whereas the core complex has both antenna and charge-separation functions, the LHCI complexes are purely light harvesting in function. In solution, the LHCI complexes are thought to form two heterodimers (Croce and Bassi, 1998).

A peculiarity of the absorption spectrum of intact PSI is the presence of significant absorption in the low-energy tail, indicating the presence of red spectral chlorophyll a forms, or states, absorbing at energies close to or lower than that of the primary donor P700. In recent years evidence from cyanobacteria (Engelmann et al., 2001) and Lhca4 (Ihalainen et al., 2003) indicate that these low-energy chlorophyll states are generated by intense Coulombic interactions between the transition dipoles of chlorophyll dimers. Their combined oscillator strength in plant PSI is approximately equivalent to 10 chlorophylls (Croce et al., 1996) and most of these seem to be associated with the LHCI complexes (Croce et al., 1998). In particular, from work with mutants (Knoetzel et al., 1998) and, more recently, using pigment/apoprotein reconstitution techniques (Melkozernov et al., 2000; Schmid et al., 2001; Croce et al., 2002), it appears that the long-wavelength fluorescing state (F730) is a property of the Lhca4 complex. Data suggesting the presence of some long-wavelength emitting states associated with Lhca2–Lhca3 in antisense mutants have been recently published (Ganeteg et al., 2001). It has been suggested that the main biological function of these red states is that of light harvesting by leaves exposed to a light environment enriched in wavelengths above 690 nm, due to shading by other leaves (Rivadossi et al., 1999). Although it is now generally accepted that they do not increase the rate of energy flow from the antenna to the primary donor chlorophylls (Fischer and Hoff, 1992; Trissl, 1993; Byrdin et al., 2000; Croce et al., 2000; Gobets et al., 2001) under steady-state illumination and at physiological temperatures, they are strongly populated, with over 80% of excited states residing on them (Croce et al., 1996). The transfer of excitation energy from them to higher energy (bulk) chlorophyll forms is via relatively slow, thermally activated processes (Jennings et al., 2003b), with the trapping time increasing progressively from 80 ps at 690 nm to 100 ps at 760 nm. This imposes a moderate, antenna-based, kinetic limitation on PSI photochemistry (Croce et al., 2000; Jennings et al., 2003b), without significantly influencing the photochemical yield, due to the fact that the excited-state lifetime for chlorophyll is in the 2- to 3-ns range in membranes.

Whereas the red-absorbing chlorophyll states of the cyanobacterial PSI have received a great deal of attention over recent years (see Melkozernov, 2001, for a recent review), relatively little attention has been given to those occurring in higher plant PSI, despite the great biological importance of this photosystem. One of the main reasons for this was the relative difficulty in obtaining LHCI preparations in which large amounts of detergent-uncoupled pigments were not present. This problem was largely overcome some years ago (Croce et al., 1998) when an apparently intact, native LHCI preparation was described, thus permitting detailed spectroscopic studies. In that study the authors described the long-wavelength fluorescence, associated with the red spectral states, which underwent pronounced red shifting (from 720 nm to 732 nm for the emission maximum) upon lowering the temperature from 280 to 77 K. This suggested the presence of multiple red-emitting states with thermal equilibration between these states explaining the temperature-dependent spectral shifting. Analysis of the temperature dependence of the absorption bandshape over this temperature range furthermore suggested that the optical reorganization energy for the red states is much greater than that for the bulk pigments, absorbing at wavelengths around 680 nm. This point was recently underlined by direct determination of the fluorescence bandshape of the long-wavelength chlorophyll state (F735) at room temperature by means of selective excitation within its absorption band (Jennings et al., 2003a). Its FWHM was shown to have the remarkable value of 55 nm at 280 K, the broadest Qy chlorophyll fluorescence band ever reported. Solution values for chlorophyll a are ∼20 nm and for non-red-shifted antenna chlorophylls values lie at ∼10–12 nm (e.g., Zucchelli et al., 2002) at comparable temperatures. This raises the question as to the underlying physical mechanism giving rise to this very large fluorescence bandwidth. In general terms, two possibilities may be suggested:

Excited-state vibrational relaxation with very strong coupling of excited-state pigment electrons to protein phonons: strong electron/phonon coupling may be promoted in excitonic dimers by the greater polarizability of excited-state electrons with respect to monomers, and evidence for such strong coupling at 1.6 K has been recently presented for low-energy chlorophylls from both LHCI and PSI-LHCI (Ihalainen et al., 2003).

Rapid solvent relaxation around the excited-state electronic configuration (e.g., Lakowicz, 1999).

This LHCI preparation has also been subjected to a detailed spectroscopic analysis by Ihalainen et al. (2000), with measurements being performed in the 6–77 K interval. These authors observed low-temperature structures in the fluorescence spectra near 702 and 733 nm and concluded that these two emitting forms were located on different Lhca dimers, i.e., the 733-nm one on Lhca1–4 and the 702-nm one on Lhca2–3. Furthermore, fluorescence polarization measurements suggested that above 705 nm only one long-wavelength form was present, i.e., the 733-nm one. This conclusion, that the long-wavelength emission tail in LHCI is attributable to only one, albeit extremely broad, emitting form, is in contrast with the interpretation of the earlier study on the same preparation (Croce et al., 1998), in which at least two low-energy emitting states were proposed. This aspect therefore requires clarification.

With the aim of providing answers to these problems concerning the optical spectroscopy of the LHCI low-energy states, we have conducted further experiments on this same preparation, using the recently described approach in which the preequilibration fluorescence of the low-energy state(s) is detected upon direct excitation (Jennings et al., 2003a). This technique, which is based on direct excitation in the same low-energy band as that from which fluorescence is detected, has the considerable advantage of providing good spectral resolution at physiologically relevant temperatures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation

PSI-LHCI was prepared as previously described (Croce et al., 1996). LHCI was isolated by solubilizing PSI-LHCI preparations from maize by treatment with n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside and Zwittergent-16 and purified by sucrose density gradient centrifugation as described previously (Croce et al., 1998). Samples were resuspended in a Tricine buffer (10 mM, pH 7.5) for fluorescence measurements at a dodecyl maltoside concentration of 0.015%. These conditions were chosen on the basis of sample stability, with no detectable changes in the steady-state fluorescence occurring over a 4-h period at the measuring temperature of 280 K. At higher detergent concentrations (0.02%, 0.03%) this stability was decreased.

Fluorescence measurements

Steady-state fluorescence emission spectra were measured at 90° with respect to the excitation beam in either an optical multichannel analyser (OMAIII Model 1460, EG&G, Gaithersburg, MD) or a CCD camera (Princeton, Applied Physics), with a spectral resolution of <0.5 nm, and were corrected for the instrument wavelength sensitivity. The excitation beam was provided by a xenon lamp passed through a Heath monochromator with the transmittance half-width adjusted to either 1 or 2 nm, depending on the excitation wavelength. The emission spectra were measured across a Schott (Wayzata, MN) OG 530 filter. When excitation was into the Qy absorption band it was possible to partially correct for the excitation spike by means of measurements performed either on the same sample, but after complete fluorescence quenching by addition of DBMIB (2,5-Dibromo-6-methyl-3-isopropyl-1,4-benzoquinone, 80 μM), or on a scattering suspension of glycogen. In this way it was possible to completely eliminate the scattering spike to within <±5 nm of the spike maximum for all excitation wavelengths. It should be mentioned that this correction was less successful when the excitation was in the low-energy side of the absorption tail, where sample extinction was lowest, and was very successful when excitation was at wavelengths where sample extinction was higher. To be on the safe side in data interpretation we have always used the ±5 nm uncertainty interval. Fluorescence anisotropy measurements were performed in the usual way (Lakowicz, 1999), with polarizers selecting the vertical component for the excitation beam and both the vertical and horizontal components for emission. The excitation wavelength used was 720 nm, with no correction being made for the excitation spike. Detector polarization bias was corrected for by using horizontally polarized excitation (Lakowicz, 1999).

Picosecond, time-resolved fluorescence measurements were performed using the time-correlated single-photon counting technique with excitation at 644 nm. The excitation source was a pulsed diode laser (PicoQuant GmbH, Berlin, Germany), peaked at 644 nm, controlled by a controller PicoQuant PDL 800-B and operating at a repetition rate of 40 Mhz. The emission decays were passed through a monochromator (Jasco CT-10, Tokyo, Japan) and detected by a microchannel plate photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu R3809U-51, Hamamatsu, Japan). The overall system prompt response was 70 ps (FWHM) which after deconvolution yielded a time resolution of 10–20 ps. The emission decays were recorded at 10-nm intervals between 660 and 780 and analyzed globally by means of an algorithm developed in the laboratory. Five decay-associated spectral components, all with significant amplitude in the 670–760 nm interval, were resolved (0.023, 0.280, 1.430, 2.745, and 3.783 ns) and the TRES were subsequently calculated using all five decays.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

LHCI

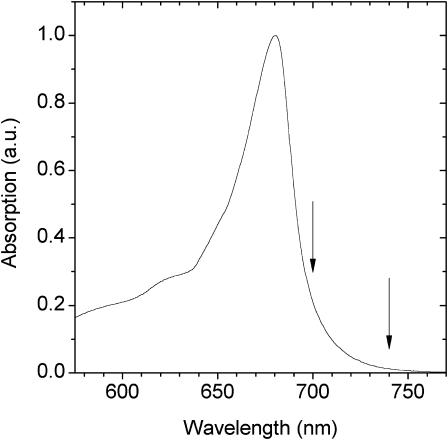

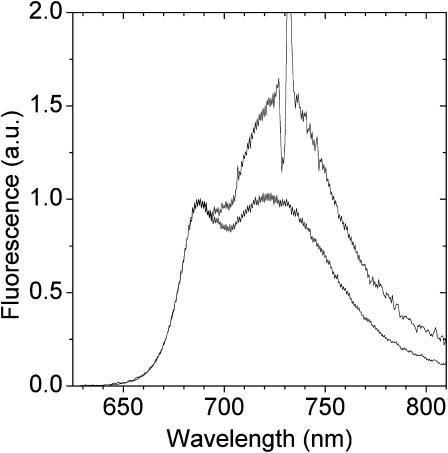

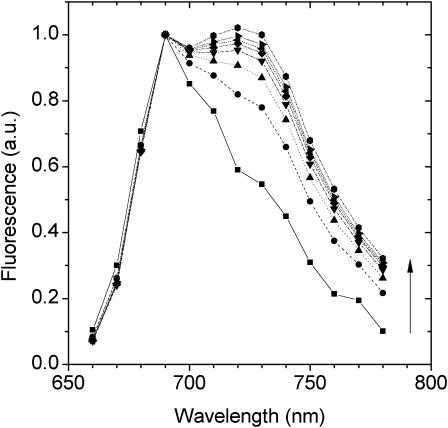

In our recent analysis of the low-energy chlorophylls of isolated LHCI it was demonstrated that these may be studied by steady-state fluorescence emission measurements performed at room temperature, by selectively exciting them within the same band as that in which fluorescence is detected (Jennings et al., 2003a). Fig. 1 shows the electronic absorption spectrum of the LHCI sample and the arrows indicate the excitation wavelength interval used for analysis of the low-energy chlorophylls. The steady-state emission spectrum, which displays a constant bandshape for excitation in the entire wavelength interval 440–690 nm, was interpreted (Jennings et al., 2003a) as approximating the equilibration spectrum, E(λ), for this preparation (Fig. 2). This interpretation, which was not previously proven, is examined in the time-resolved fluorescence experiment presented in Fig. 3. Data are presented as the TRES for the LHCI preparation. Though time-resolved fluorescence data are usually presented as decay-associated spectra, changes in fluorescence spectral bandshape as a function of time are most readily observed as TRES. We have normalized the TRES to the emission maximum of the bulk pigments, at 690 nm. Normalization to other bulk emission wavelengths, e.g., 680 nm, leads to very similar results. The TRES show that spectral evolution between the bulk and low-energy pigments is slow, in general agreement with previous data on LHCI-730 at room temperature (Pålsson et al., 1995; Melkozernov et al., 1998; Gobets et al., 2001), with significant changes occurring up to 0.25–0.5 ns, after which time further spectral evolution is slow and a quasisteady state is attained. The spectral shape of these quasisteady-state TRES bear a clear resemblance to the steady-state emission spectrum, E(λ), of Fig. 2, thus indicating that this latter spectrum is indeed very close to the equilibration spectrum for this sample. The TRES difference spectrum for long decay times minus that for time zero or very short decay times yields the preequilibrium spectrum for this sample (data not shown). This preequilibrium spectrum is also detected under steady-state conditions, upon direct excitation in the low-energy chlorophyll states, and with much greater spectral resolution (Fig. 4, and Jennings et al., 2003a).

FIGURE 1.

Electronic absorption spectrum of LHCI measured at 280 K. The arrows indicate the wavelength interval used for selective excitation of low-energy antenna states.

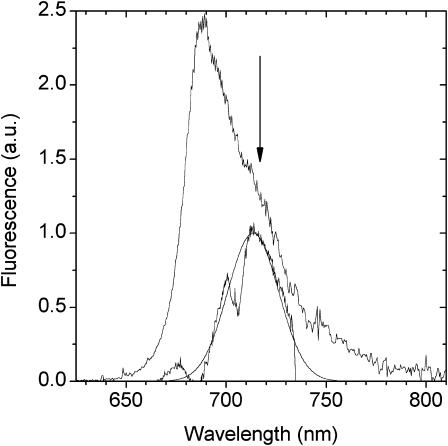

FIGURE 2.

Steady-state emission spectra (280 K) of LHCI excited at 470 nm (lower) and 730 nm (upper). Spectra have been normalized to the bulk antenna emission peak near 685 nm.

FIGURE 3.

Time-resolved emission spectra of LHCI. Spectra were determined as described in Materials and Methods for the following time lags: zero, 0.025 ns, 0.05 ns, 0.1 ns, 0.25 ns, 0.5 ns, 1 ns, and 3 ns, where the arrow indicates the time vector. All spectra were normalized at 690 nm.

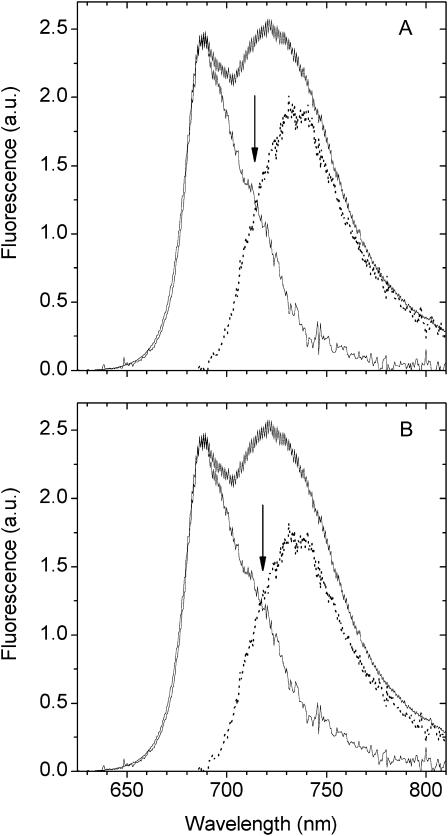

FIGURE 4.

Steady-state emission spectrum (E(λ)) of LHCI with 470-nm excitation. Within the E(λ) spectrum the F735 band is shown (dots) for weighting factors of 0.95 (A) and 0.86 (B) with respect to the wavelength interval 750–800 nm. Also shown are the respective difference spectra E(λ) − F735. The arrow at 715 nm indicates the long-wavelength emission structure in the E(λ) − F735 spectra.

As previously shown (Jennings et al., 2003a) the steady-state emission spectrum changes dramatically in shape when the excitation beam selectively excites the low-energy pigments at wavelengths >700 nm (Figs. 1 and 2). This was interpreted in terms of the slow, energetically uphill, energy transfer from the low-energy state(s) to the bulk pigments, that is to say, as a preequilibrium fluorescence. A similar interpretation for long-wavelength excitation of a cyanobacterial core particle was previously suggested by Gill and Wittmershaus (1999). Although the E(λ) spectrum may be represented by a linear combination of the emission bandshapes of all spectral states, En(λ), weighted by their respective equilibrium excited-state population terms, Pn, the preequilibrium spectrum (PE(λ)) contains an additional term due to emission from the low-energy state(s), which are directly excited:

|

(1) |

where  is a phenomenological term that represents the preequilibrium population of the emission states, directly excited by the excitation beam, integrated over their excited-state lifetime. The simple difference spectrum, PE(λ) − E(λ), thus yields the emission bandshape(s) of the long-wavelength state(s) that are directly excited, weighted by their preequilibrium excited-state population. In the special case that only a single spectral form absorbs at the wavelength of the excitation beam, then only the relative

is a phenomenological term that represents the preequilibrium population of the emission states, directly excited by the excitation beam, integrated over their excited-state lifetime. The simple difference spectrum, PE(λ) − E(λ), thus yields the emission bandshape(s) of the long-wavelength state(s) that are directly excited, weighted by their preequilibrium excited-state population. In the special case that only a single spectral form absorbs at the wavelength of the excitation beam, then only the relative  term has a nonzero value and the PE(λ) − E(λ) difference spectrum yields the emission bandshape of this state. As previously reported, this is the case for the excitation interval 720–740 nm (Jennings et al., 2003a), and the emission bandshape is that of the remarkably broad F735. This emission bandshape, which was experimentally derived in Jennings et al. (2003a), is shown in Fig. 4, where it underlies the E(λ) spectrum.

term has a nonzero value and the PE(λ) − E(λ) difference spectrum yields the emission bandshape of this state. As previously reported, this is the case for the excitation interval 720–740 nm (Jennings et al., 2003a), and the emission bandshape is that of the remarkably broad F735. This emission bandshape, which was experimentally derived in Jennings et al. (2003a), is shown in Fig. 4, where it underlies the E(λ) spectrum.

We have checked whether the spectral band characteristics of the 735-nm emission states are able to provide a reasonable description of the long-wavelength equilibrated emission of LHCI. To this end we have “manually fitted” the 735-nm form to the long-wavelength fluorescence wing of the E(λ) spectrum, recognizing that a small contribution to the long-wavelength wing must derive from the vibrational bands of the “bulk” pigments. We do not know the exact intensity of this vibrational signal and have therefore allowed it to vary between 0.05 and 0.14 of the long-wavelength emission tail (Fig. 4) with the remaining 0.95 and 0.86 being described by the 735-nm emission bandshape. It is evident from this figure that the 735-nm emission band, while providing a satisfactory description of the 740–800 nm interval, fails to describe all the long-wavelength emission. An emission structure is clearly present in the 710–720 nm interval (Fig. 4, and see Fig. 6), clearly suggesting the presence of another red-emitting state, blue-shifted with respect to the 735-nm state.

FIGURE 6.

The E(λ) − F735 spectrum of Fig. 4 B. Within this spectrum, the difference spectrum PE(λ)707 − PE(λ)Σ, calculated after normalization near 760 nm, is shown. The Gaussian approximation of this spectrum is also presented. This spectrum defines the F713 emission band of LHCI.

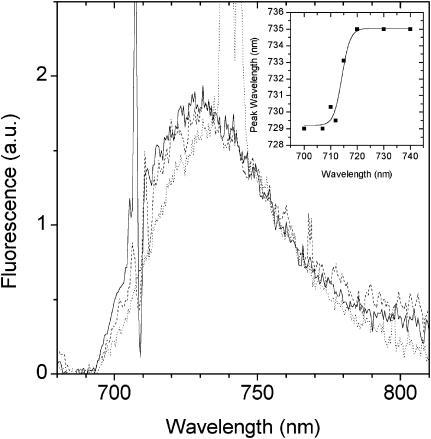

To gain further evidence for a second, red-emitting spectral state we have excited the LHCI sample at wavelengths below 720 nm. From Fig. 5 it can be seen that upon excitation below 720 nm the PE(λ) − E(λ) spectra undergo blue shifting of the peak position and also become somewhat broader toward shorter wavelengths (Fig. 5). This blue shifting of the wavelength maximum of the PE(λ) − E(λ) is plotted as a function of excitation wavelength in Fig. 5 (inset). It is evident from Fig. 5 that at excitation wavelengths below 720 nm, fluorescence from a state(s) that is somewhat less red-shifted than F735 grows into the PE(λ) − E(λ) spectrum. As the bandshape on the long-wavelength wing (730–780 nm) remains constant, we interpret these measurements as being due to the preequilibrium emission of both the F735 and another blue-shifted, low-energy state(s). The intensity of this other less red-shifted state(s) depends on the associated  value. In this case,

value. In this case,  is expected to be less than for the 735-nm emitting state as the energy gap with the bulk pigments is less. From Eq. 1 the bandshape of this shorter wavelength emission state is determined by the difference of PE(λ)<720 − PE(λ)Σ after normalization to the red tail near 760 nm. The subscript refers to the excitation wavelengths and the PE(λ)Σ spectrum is the F735 spectrum shown in Fig. 4. The result of this analysis is presented in Fig. 6 (bottom spectrum) where it can be seen that a single spectral state is present. From the Gaussian approximation of this band the emission maximum of this state appears to be close to 713 nm. The bandwidth (FWHM) is ∼27 nm. Similar data are obtained for 710-nm and 712-nm excitation (data not presented). This FWHM value is half that of the 735-nm emitting state but approximately double that of non-red-shifted antenna pigments.

is expected to be less than for the 735-nm emitting state as the energy gap with the bulk pigments is less. From Eq. 1 the bandshape of this shorter wavelength emission state is determined by the difference of PE(λ)<720 − PE(λ)Σ after normalization to the red tail near 760 nm. The subscript refers to the excitation wavelengths and the PE(λ)Σ spectrum is the F735 spectrum shown in Fig. 4. The result of this analysis is presented in Fig. 6 (bottom spectrum) where it can be seen that a single spectral state is present. From the Gaussian approximation of this band the emission maximum of this state appears to be close to 713 nm. The bandwidth (FWHM) is ∼27 nm. Similar data are obtained for 710-nm and 712-nm excitation (data not presented). This FWHM value is half that of the 735-nm emitting state but approximately double that of non-red-shifted antenna pigments.

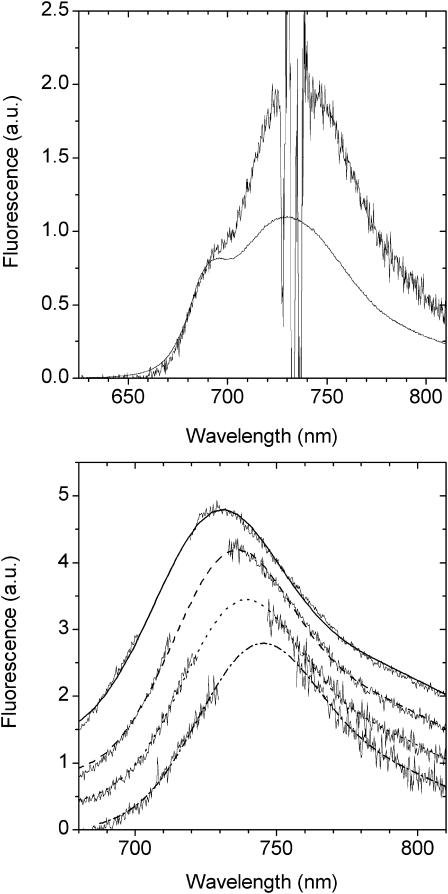

FIGURE 5.

Difference emission spectra PE(λ)707,710,740 − E(λ) normalized at 755 nm. The spectra may be identified by the wavelength position of the scattering spike. The inset shows the PE(λ) − E(λ) wavelength maxima for excitation in the 700–740 nm interval. Wavelength maxima were determined by means of a Gaussian curve-fitting procedure.

In Fig. 6 the F713 bandshape has been inserted under the E(λ) − PE(λ)Σ spectrum of Fig. 4. It is evident that this bandshape closely corresponds to the low-energy emission structure (arrow) in the E(λ) − PE(λ)Σ spectrum.

We therefore conclude that the long-wavelength emission of isolated LHCI is due to two low-energy emitting forms, with maxima near 713 nm and 735 nm (Figs. 4 and 7). This conclusion is at variance with that of Ihalainen et al. (2000) who, using a similar LHCI preparation, presented evidence for only a single low-energy emission form, present at cryogenic temperatures, which corresponds to the 735-nm form. Of course, at the very low temperatures at which their experiments were performed, if the 713-nm and 735-nm states were located on the same LHCI complex then only the lower-energy one would have been significantly populated and hence experimentally detectable.

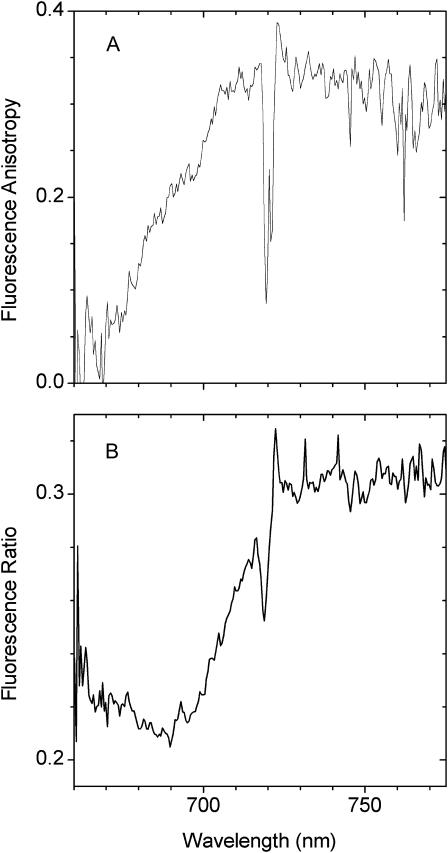

FIGURE 7.

(A) Fluorescence anisotropy spectrum of LHCI. The excitation wavelength was 720 nm. For further details see Materials and Methods. (B) Fluorescence ratio spectrum of LHCI for excitation wavelengths of 720 nm and 470 nm. The 720-nm spectrum was divided by the 470-nm spectrum.

A key experiment of Ihalainen et al. (2000) that favored their interpretation was that of the steady-state fluorescence anisotropy, which increased with excitation wavelength over the bulk chlorophyll absorption band, to attain a very high (∼0.32) and constant value at wavelengths >705 nm, when fluorescence was measured between 700 nm and 720 nm. We have performed a similar fluorescence anisotropy experiment by exciting in the long-wavelength tail at 720 nm and measuring the polarized fluorescence over the entire emission interval. The data (Fig. 7 A), where the excitation spike is clearly visible at 720 nm, are in general agreement with the low-temperature measurements of Ihalainen et al. (2000), with anisotropy increasing across the bulk chlorophyll band to attain a maximal value of 0.32 ± 0.02 between 705 and 710 nm. For steady-state anisotropy the maximum value is 0.4, which is attained when emission is measured from the same chromophore, or a chromophore with identical transition dipole orientation, as that excited. As far as we are aware, this value of 0.32 ± 0.02 is the highest ever obtained for a photosynthetic system at room temperature. It is particularly interesting that this value is reached in the 705–710 interval where emission from the 713-nm state is present and when excitation is selectively into the 735-nm state. This point is underlined in Fig. 7 B, where the ratio of the nonpolarized emission spectra excited at 720 nm (PE720) to that excited at 470 nm (E(λ)) is shown. This ratio,  unlike the anisotropy spectrum, increases to wavelengths >720 nm, to then remain constant. This is expected when excitation is selectively into the 735-nm state. The fact that the anisotropy spectrum with 720 nm excitation attains its maximal value at wavelengths from 705 to 710 nm indicates that the 713-nm emitting state is associated with the same LHCI complex as the 735-nm one, as it can only be populated by energy transfer when the 735-nm state is selectively excited. It is therefore necessary to conclude that the emission transition dipoles of the two red-emitting states have very similar orientations. From linear dichroism measurements at 4 K (Ihalainen et al., 2000) it was concluded that the absorption band giving rise to the 735-nm emission form has its Qy transition dipole oriented almost in the membrane plane. Our data suggest that the 713-nm emitting forms have much the same transition dipole orientation.

unlike the anisotropy spectrum, increases to wavelengths >720 nm, to then remain constant. This is expected when excitation is selectively into the 735-nm state. The fact that the anisotropy spectrum with 720 nm excitation attains its maximal value at wavelengths from 705 to 710 nm indicates that the 713-nm emitting state is associated with the same LHCI complex as the 735-nm one, as it can only be populated by energy transfer when the 735-nm state is selectively excited. It is therefore necessary to conclude that the emission transition dipoles of the two red-emitting states have very similar orientations. From linear dichroism measurements at 4 K (Ihalainen et al., 2000) it was concluded that the absorption band giving rise to the 735-nm emission form has its Qy transition dipole oriented almost in the membrane plane. Our data suggest that the 713-nm emitting forms have much the same transition dipole orientation.

As discussed previously (Jennings et al., 2003a), the F735 emission state has a most unusual fluorescence bandshape for a protein-bound chlorophyll, by reason of both its extremely broad bandwidth and marked asymmetry (spectral skew) at 280 K. Although these bandshape properties can be the result of strong coupling to protein phonon frequencies greater than those normally associated with antenna pigments (i.e., >30 cm−1; Zucchelli et al., 1996, 2002), they may also be produced by interactions with the solvent environment of this pigment state. It is therefore of interest to establish the absorption origin band of the F735 state, as this may provide information on these extraordinary spectral properties. To this end we have determined the fluorescence excitation (action) spectrum of the 735-nm form in the 700–740 nm excitation interval. Data have been normalized to the incident excitation photon flux, as determined by the area under the scattering spike, using glycogen. The results are shown in Fig. 8, where it is clear that the maximum is close to 710 nm. The steep decline on the short-wavelength side is a deformation of the excitation spectrum, due to increasing absorption by pigments, other than the 735-nm state, as the excitation wavelength moves into the tail of the bulk absorption band. This maximum at 710 nm for the room-temperature spectrum is in agreement with the suggestion of Ihalainen et al. (2000), who analyzed the 6 K spectrum by Gaussian decomposition, and puts their conclusion on a sound basis. Thus the 710/735 chlorophyll form of LHCI has the amazingly large Stokes shift of 25 nm, which may be compared with that of normal, non-red-shifted chlorophyll antenna forms for which the Stokes shift, approximately equal to twice the optical reorganization energy, is expected to be no more than 2 nm (Zucchelli et al., 1996, 2002). We have therefore asked the question as to whether this may be due to the effect of rapid solvent relaxation around its excited state, which is known to give rise to large Stokes shifts of dye molecules in polar solvents (Lakowicz, 1999). Although there is no evidence for this phenomenon in antenna chlorophyll it has been suggested to occur for some reaction-center primary donors (Borisov and Kuznetsova, 2002). In this context Stark spectroscopic measurements (Frese et al., 2002) have recently shown that a red-shifted bacterial chlorophyll has a quite large dipole moment in the excited state, which is a prerequisite for rapid solvent relaxation effects. The alternative possibility is that the large Stokes shift is associated with normal vibrational relaxation processes in an excited-state manifold that has an unusually broad energy spread. We have therefore used the emission bandshape for the 710/735 state and, by means of the Stepanov expression (Stepanov, 1957),

|

calculated the absorption bandshape A(ν). F(ν) is the fluorescence spectrum, D(T) is a term independent of frequency, h is the Planck constant, and k is the Boltzmann constant.

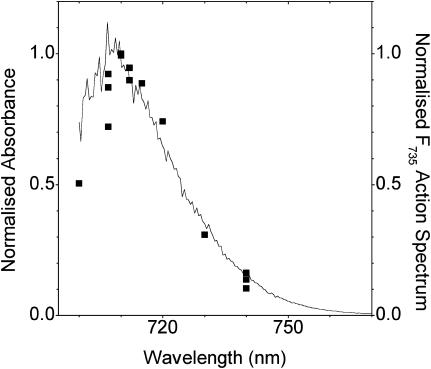

FIGURE 8.

Excitation (action) spectrum for the F735 fluorescence state (square symbols). The data are for equal photon fluence and are overlaid by the absorption spectrum of the F735 state, which was calculated by means of the Stepanov expression (see text) using the fluorescence bandshape of F735 (Fig. 4).

This expression, which has been shown to work quite well for a variety of antenna chl/protein complexes (Zucchelli et al., 1995; Croce et al., 1996; Dau and Sauer, 1996; Giuffra et al., 1997), assumes vibrational relaxation in the excited-state manifold and an absence of significant electronic rearrangements with respect to the ground state. With these assumptions the calculated absorption bandshape for the 710/735 state comes out as in Fig. 8, where it overlays the excitation spectrum for this form. Quite close agreement between the two data sets down to 705 nm is evident, with the calculated absorption maximum falling at 709 nm. We therefore conclude that the 25-nm Stokes shift is not due to solvent relaxation effects and can be accounted for by vibrational relaxation in an energetically broad excited-state manifold. The broadness of the excited-state manifold is probably due to the strong electron coupling to high-frequency phonons, very recently suggested by Ihalainen et al (2003). Furthermore, it would seem reasonable to suggest, given the assumptions on which the Stepanov theory is based, that there is no significant increase in the permanent dipole in the excited state.

Recent experiments with in vitro reconstituted LHCI monomers suggest that the 735-nm emission state is associated with Lhca4, and possibly also with Lhca3, though in lesser amounts (Croce et al., 2002). The 713-nm emission state has not hitherto been identified and our data suggest that it is in energy coupling contact with the 735-nm state in the LHCI preparation. As the Lhca1 monomer, which is thought to form a heterodimer with Lhca4, does not contain such red-shifted emitting states, it is reasonable to suggest that the 713-nm state is also associated with Lhca4. Experiments with the in vitro reconstituted complexes are in progress to investigate this aspect.

PSI-LHCI

In this section we pose the question of whether the low-energy forms in intact PSI-LHCI, that is, the state in which the external LHCI antenna dimers are bound to the core complex, are similar to those of isolated LHCI. Suggestions that this might not be the case come from our earlier experiments (Croce et al., 1996, 1998), in which it was shown that as the temperature is lowered from 280 K to 70 K the emission maxima undergo a thermodynamic red shift from 720 nm to 733 nm in LHCI and from 730 nm to 742 nm in PSI-LHCI. We have therefore analyzed the PSI-LHCI sample by measuring the steady-state emission spectra under long-wavelength excitation (PE(λ)) and comparing it with the E(λ) spectrum with 470 nm excitation, as described above for LHCI (Fig. 9, upper panel). As we have previously demonstrated (Croce et al., 1996) that under 470-nm excitation the 280 K emission spectrum closely approximates that expected for thermodynamic equilibrated excited states in PSI-LHCI, it is apparent that selective excitation in the low-energy chlorophyll states leads to marked preequilibrium fluorescence, as in isolated LHCI. It should be mentioned that this experiment is somewhat more difficult in the case of PSI-LHCI due to the short lifetime (80–100 ps) of this sample, compared with the nanosecond lifetime of LHCI, and required long accumulation times in the CCD instrument with the excitation monochromator slit much more open than was the case for the LHCI measurements.

FIGURE 9.

(Top panel) Steady-state emission spectra (280 K) of PSI-LHCI excited at 470 nm (lower) and 730 nm (upper). Spectra have been normalized to the bulk antenna emission near 690 nm. (Bottom panel) Difference emission spectra PE(λ)710,720,730,740 − E(λ) normalized at 755 nm. The noisy curves represent the difference spectra and the dotted lines the fitted spectra. Spectra are offset for clarity.

The E(λ) − PE(λ) values for excitation at 740, 730, 720, and 710 nm are shown in Fig. 9, lower panel, where the E(λ) was measured under 470 nm excitation. For clarity of presentation the signal in the wavelength interval (12–17 nm) covered by the excitation spike, after correction, has been removed. In the case of the 740- and 730-nm excitation the emission peak falls within this interval and it is necessary to rely on a Gaussian curve-fitting procedure to estimate the peak wavelength position. For the 740-nm excitation it is evident from the signal asymmetry that the peak is above the excitation maximum and the curve fit suggests it to be close to 746 nm. For the 730-nm excitation the peak position is estimated at 741 nm. For the 720-nm and 710-nm excitations both curve-fitting and visual estimation place the peak wavelength positions near 736 and 732 nm, respectively. These data are represented in Fig. 10, where they are compared with the LHCI data presented in the inset to Fig. 5. It is evident that the low-energy chlorophyll compositions of the two preparations are not identical. Under 740- and 730-nm excitation the peak wavelength position of PSI-LHCI is red-shifted by 11 nm and 6 nm, respectively, with respect to that of LHCI (F735). These data, for 280 K, are in agreement with the above-mentioned thermodynamic red shifting of the emission peak in LHCI and PSI-LHCI (Croce et al., 1996, 1998) under cryogenic temperature measurement conditions, and indicate that there are low-energy chlorophyll states in intact PSI-LHCI that are not present in isolated LHCI and that are considerably more red-shifted. The bandwidths for the 710- to 740-nm excitation are in the 60–65 nm interval, slightly greater than those determined for LHCI (55 nm), and indicate very strong electron-phonon coupling. As PSI-LHCI is prepared using the octyl-glucoside method (Croce et al., 1996), whereas LHCI is prepared with dodecyl maltoside (Croce et al., 1998), these differences in red form content could, in principle, be attributed to the different detergents used. However, this can be excluded as the bandshape of the red-emitting states, in the spectral interval 720–780 nm (280 K), is identical for PSI-LHCI prepared either with octyl glucoside or dodecyl maltoside (unpublished data), even though the red form content of the dodecyl maltoside preparation is somewhat reduced. We therefore suggest that these differences are caused, in some way, by interactions between complexes in PSI-LHCI, which are destroyed upon solubilization of LHCI.

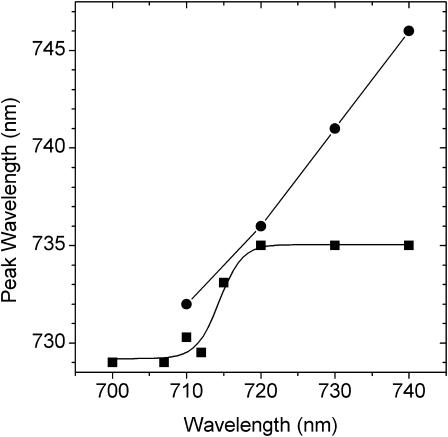

FIGURE 10.

Wavelength maxima for the PE(λ) − E(λ) spectra of PSI-LHCI (dots) and LHCI (squares), for excitation in the 700–740 nm interval. The data for LHCI have been taken from Fig. 5. The wavelength maxima were determined by means of a Gaussian curve-fitting procedure.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially financed by Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di Base grant RBAU01E3CX.

Abbreviations used: LHCI, light harvesting complex I; P700, photosystem I primary electron donor; PSI, photosystem I; FWHM, full width at half maximum; Lhca1–4, individual polypeptides composing the external antenna of photosystem I; TRES, time-resolved spectra.

References

- Bassi, R., and D. J. Simpson. 1987. Chlorophyll-protein complexes of barley photosystem I. Eur. J. Biochem. 163:221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shem, A., F. Frolow, and N. Nelson. 2003. Crystal structure of plant photosystem I. Nature. 426:630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekema, E. J., P. E. Jensen, E. Schlodder, J. F. L. van Breemen, H. van Roon, H. V. Scheller, and J. P. Dekker. 2001. Green plant photosystem I binds light-harvesting complex I on one side of the complex. Biochemistry. 40:1029–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisov, A. I., and S. A. Kuznetsova. 2002. On the involvement of the water-polaron mechanism in energy trapping by reaction centers of purple bacteria. Biochemistry. 67:1224–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, B. D., and R. Malkin. 1988. Subunit stoichiometry of the chloroplast photosystem I complex. J. Biol. Chem. 263:7302–7308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrdin, M., I. Rimke, E. Schlodder, D. Stehlik, and T. A. Roelofs. 2000. Decay kinetics and quantum yields of fluorescence in photosystem I from Synechococcus elongatus with P700 in the reduced and oxidized state: Are the kinetics of excited state decay trap-limited or transfer-limited? Biophys. J. 79:992–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce, R., and R. Bassi. 1998. The light-harvesting complex of photosystem I: pigment composition and stoichiometry. In Photosynthesis: Mechanisms and Effects. G. Garab, editor. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 421–424.

- Croce, R., D. Dorra, A. R. Holzwarth, and R. C. Jennings. 2000. Fluorescence decay and spectral evolution in intact photosystem I of higher plants. Biochemistry. 39:6341–6348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce, R., T. Morosinotto, S. Castelletti, J. Breton, and R. Bassi. 2002. The Lhca antenna complexes of higher plants photosystem I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1556:29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce, R., G. Zucchelli, F. M. Garlaschi, R. Bassi, and R. C. Jennings. 1996. Excited state equilibration in the photosystem I light-harvesting I complex: P700 is almost isoenergetic with its antenna. Biochemistry. 35:8572–8579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce, R., G. Zucchelli, F. M. Garlaschi, and R. C. Jennings. 1998. A thermal broadening study of the antenna chlorophylls in PSI-200, LHCI, and PSI core. Biochemistry. 37:17355–17360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau, H., and K. Sauer. 1996. Exciton equilibration and photosystem II exciton dynamics—a fluorescence study on photosystem II membrane particles of spinach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1273:175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann, E., T. Tagliabue, N. V. Karapetyan, F. M. Garlaschi, G. Zucchelli, and R. C. Jennings. 2001. CD spectroscopy provides evidence for excitonic interactions involving red-shifted chlorophyll forms in photosystem I. FEBS Lett. 499:112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, M. R., and A. J. Hoff. 1992. On the long-wavelength component of the light-harvesting complex of some photosynthetic bacteria. Biophys. J. 63:911–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frese, R. N., M. A. Palacios, A. Azzizi, I. H. M. van Stokkum, J. Kruip, M. Rogner, N. V. Karapetyan, E. Schlodder, R. van Grondelle, and J. P. Dekker. 2002. Electric field effects on red chlorophylls, beta-carotenes and P700 in cyanobacterial Photosystem I complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1554:180–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganeteg, U., A. Strand, P. Gustafsson, and S. Jansson. 2001. The properties of the chlorophyll a/b-binding proteins Lhca2 and Lhca3 studied in vivo using antisense inhibition. Plant Physiol. 127:150–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill, E. M., and B. P. Wittmershaus. 1999. Spectral resolution of low-energy chlorophylls in Photosystem I of Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 through direct excitation. Photosynth. Res. 61:53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffra, E., G. Zucchelli, D. Sandonà, R. Croce, D. Cugini, F. M. Garlaschi, R. Bassi, and R. C. Jennings. 1997. Analysis of some optical properties of a native and reconstituted photosystem II antenna complex, CP29: pigment binding sites can be occupied by chlorophyll a or chlorophyll b and determine spectral forms. Biochemistry. 36:12984–12993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobets, B., I. H. M. van Stokkum, M. Rogner, J. Kruip, E. Schlodder, N. V. Karapetyan, J. P. Dekker, and R. van Grondelle. 2001. Time-resolved fluorescence emission measurements of photosystem I particles of various cyanobacteria: a unified compartmental model. Biophys. J. 81:407–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golbeck, J. H. 2003. The binding of cofactors to photosystem I analyzed by spectroscopic and mutagenic methods. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 32:237–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihalainen, J. A., B. Gobets, K. Sznee, M. Brazzoli, R. Croce, R. Bassi, R. van Grondelle, J. E. I. Korppi-Tommola, and J. P. Dekker. 2000. Evidence for two spectroscopically different dimers of light-harvesting complex I from green plants. Biochemistry. 39:8625–8631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihalainen, J. A., M. Ratsep, P. E. Jensen, H. V. Scheller, R. Croce, R. Bassi, J. E. I. Korppi-Tommola, and A. Freiberg. 2003. Red spectral forms of chlorophylls in green plant PSI—a site-selective and high-pressure spectroscopy study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 107:9086–9093. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, R. C., R. Bassi, and G. Zucchelli. 1996. Antenna structure and energy transfer in higher plants photosystems. Top. Curr. Chem. 177:147–181. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, R. C., F. M. Garlaschi, T. Morosinotto, E. Engelmann, and G. Zucchelli. 2003a. The room temperature emission band shape of the lowest energy chlorophyll spectral form of LHCI. FEBS Lett. 547:107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, R. C., G. Zucchelli, R. Croce, and F. M. Garlaschi. 2003b. The photochemical trapping rate from red spectral states in PSI-LHCI is determined by thermal activation of energy transfer to bulk chlorophylls. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1557:91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P., P. Fromme, H. T. Witt, O. Klukas, W. Saenger, and N. Krauss. 2001. Three-dimensional structure of cyanobacterial photosystem I at 2.5 Angstrom resolution. Nature. 411:909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoetzel, J., B. Bossmann, and L. H. Grimme. 1998. Chlorina and viridis mutants of barley (hordeum vulgare L.) allow assignment of long-wavelength chlorophyll forms to individual lhca proteins of photosystem I in vivo. FEBS Lett. 436:339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz, J. R. 1999. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Kluwer/Plenum Press, New York.

- Melkozernov, A. N. 2001. Excitation energy transfer in Photosystem I from oxygenic organisms. Photosynth. Res. 70:129–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkozernov, A. N., S. Lin, V. H. R. Schmid, H. Paulsen, G. W. Schmidt, and R. E. Blankenship. 2000. Ultrafast excitation dynamics of low energy pigments in reconstituted peripheral light-harvesting complexes of photosystem I. FEBS Lett. 471:89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkozernov, A. N., V. H. R. Schmid, G. W. Schmidt, and R. E. Blankenship. 1998. Energy redistribution in heterodimeric light-harvesting complex lhc1–730 of photosystem I. J. Phys. Chem. B. 102:8183–8189. [Google Scholar]

- Pålsson, L. O., S. E. Tjus, B. Andersson, and T. Gillbro. 1995. Ultrafast energy transfer dynamics resolved in isolated spinach light-harvesting complex I and the LhcI-730 subpopulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1230:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rivadossi, A., G. Zucchelli, F. M. Garlaschi, and R. C. Jennings. 1999. The importance of PSI chlorophyll red forms in light-harvesting by leaves. Photosynth. Res. 60:209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, V. H. R., P. Thome, W. Ruhle, H. Paulsen, W. Kuhlbrandt, and H. Rogl. 2001. Chlorophyll b is involved in long-wavelength spectral properties of light-harvesting complexes LHC I and LHC II. FEBS Lett. 499:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanov, B. I. 1957. A universal relation between the absorption and luminescence spectra of complex molecules. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR Phys. Sect. 2:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Trissl, H. W. 1993. Long-wavelength absorbing antenna pigments and heterogeneous absorption bands concentrate excitons and increase absorption cross section. Photosynth. Res. 35:247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchelli, G., F. M. Garlaschi, R. Croce, R. Bassi, and R. C. Jennings. 1995. A Stepanov relation analysis of steady-state absorption and fluorescence spectra in the isolated D1/D2/cytochrome b-559 complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1229:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zucchelli, G., F. M. Garlaschi, and R. C. Jennings. 1996. Thermal broadening analysis of the light harvesting complex II absorption spectrum. Biochemistry. 35:16247–16254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchelli, G., R. C. Jennings, F. M. Garlaschi, G. Cinque, R. Bassi, and O. Cremonesi. 2002. The calculated in vitro and in vivo chlorophyll a absorption bandshape. Biophys. J. 82:378–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]