Abstract

To accomplish its DNA strand exchange activities, the Escherichia coli protein RecA polymerizes onto DNA to form a stiff helical nucleoprotein filament within which the DNA is extended by 50%. Homology search and recognition occurs between ssDNA within the filament and an external dsDNA molecule. We show that stretching the internal DNA greatly enhances homology recognition by increasing the probability that the homologous regions of a stretched DNA molecule and a parallel, unstretched DNA molecule will be “in register” at some position. We also show that the stretching and stiffness of the filament act together to ensure that initiation of homologous exchange between the substrate DNA molecules at one position precludes initiation of homologous exchange at any other position. This prevents formation of multiple exchange site “topological traps” which would prevent completion of the exchange reaction and resolution of the products.

INTRODUCTION

RecA is a 38-kDa Escherichia coli protein that plays a key role both in DNA repair and in the exchange of genetic material by promoting DNA strand exchange. RecA or an RecA homolog has been found in every species in which it has been sought (Roca and Cox, 1997). RecA-mediated strand exchange is important in maintenance of the genome and essential for sexual reproduction. To facilitate strand exchange, RecA polymerizes onto both single- and double-stranded DNA (ssDNA and dsDNA) to form a right-handed helical filament ∼10 nm in diameter (Heuser and Griffith, 1989) with a 6-monomer-per-turn repeat length (Yu and Egelman, 1992; Takahashi and Norden, 1994).

The extended filament, formed with an ATP cofactor (Heuser and Griffith, 1989; Yu and Egelman, 1992), is the active form of RecA for strand exchange. Extended filaments are very stiff. The persistence length of the extended filaments formed with ssDNA is ξssDNA·RecA ≃ 860 nm (Hegner et al., 1999), ∼16 times that of dsDNA. DNA within the extended filament is stretched by 50% relative to B-form DNA. Although many different proteins with diverse functions act on DNA, most act as monomers or components of oligomers containing relatively few other elements. RecA is unusual in forming a stable protein filament to accomplish its activity.

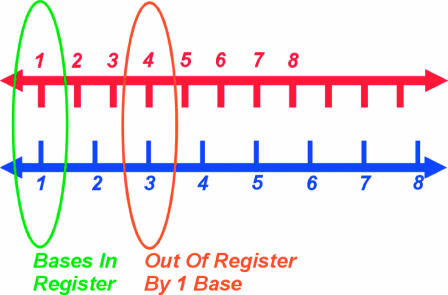

The presence of this structure is puzzling. Stretching DNA by 50% is energetically expensive, requiring ∼0.7 kBT per basepair for dsDNA. The presence of the filament also seems likely to hinder the close contact between the DNA substrates necessary for sequence comparison. Moreover, stretching one substrate DNA molecule relative to the other seems to present a serious obstacle to RecA activity by complicating the process of aligning regions of homology between them. Fig. 1 shows how a stretched DNA molecule is unable to remain “in register” with a homologous region on an unstretched DNA molecule. If they are homologously aligned at one base(pair), the neighboring base(pair) is “out of register” by the difference in base(pair) spacing between the two molecules. For RecA filaments, the stretching is by 50%. Starting from a homologously aligned base(pair), the next-to-neighboring base on the stretched molecule is an entire base out-of-register. These facts would seem to inhibit the strand exchange activity.

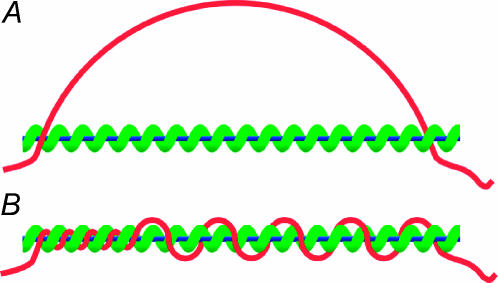

FIGURE 1.

Unequal spacing between basepairs obstructs homologous alignment. Spacing between consecutive bases on the bottom strand is 50% larger than on the top strand, as for RecA filaments. The molecules are homologously aligned at base 1. By base 3 on the stretched strand they are an entire base out-of-register.

Other DNA processing proteins, including those with recombination or repair activity, function without needing this structure, yet the RecA family have preserved the filament structure over 2.5 billion years of evolution in species as diverse as E. coli and Homo sapiens. The aim of this article is to use basic physical considerations to understand the role of RecA filaments in RecA function.

FACILITATING HOMOLOGOUS ALIGNMENT

Incompatible interbase spacings

Homology recognition requires that many consecutive basepairs be recognized as complementary. Identifying only a single pair of complementary bases is insufficient, yet stretching the DNA within the filament limits simultaneous comparison to a single basepair. Surprisingly, stretching the DNA within the filament does not impede, but rather accelerates the initial alignment of the homologous regions of the DNA substrates.

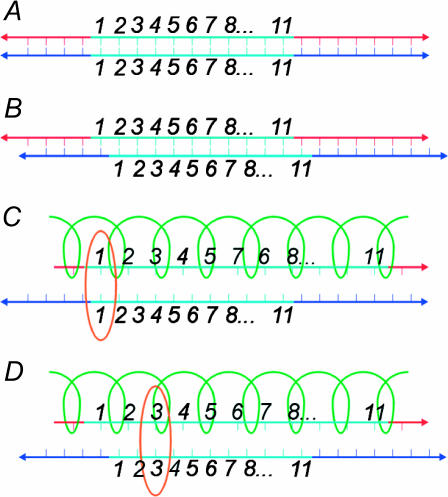

To see how, consider two B-form DNA molecules having a region of homology. The distance between consecutive basepairs of B-form DNA is  If these molecules are parallel, then for some position of one molecule relative to the other, the homologous regions will be homologously aligned. As shown in Fig. 2 A, every basepair throughout the region of homology is then homologously aligned.

If these molecules are parallel, then for some position of one molecule relative to the other, the homologous regions will be homologously aligned. As shown in Fig. 2 A, every basepair throughout the region of homology is then homologously aligned.

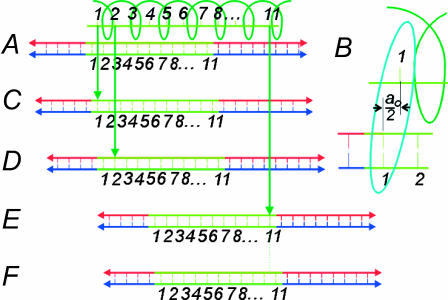

FIGURE 2.

Alignment between DNA molecules. The blue regions are homologous. (A) Consecutive bases are a distance a0 apart in both molecules. All homologous bases are homologously aligned and in-register. (B) The bottom strand has been moved to the right a distance a0. Now none of the bases are homologously aligned. (C) The upper molecule is coated with RecA, so bases are 3a0/2 apart. The first base in the region of homology is homologously aligned (orange circle), but all others are out-of-register. (D) Moving the bottom strand to the right a distance a0 does not destroy the alignment, but merely moves its location to the third base in the region of homology (orange circle). All other bases remain out-of-register.

Fig. 2 B shows the effect if we displace one molecule relative to the other by a0, the distance between consecutive basepairs. Now, none of the basepairs are homologously aligned. When two DNA molecules have identical spacing between consecutive bases, being out-of-register anywhere results in being out-of-register everywhere. Homologous alignment between two DNA molecules with identically spaced bases is an all-or-nothing phenomenon.

Next, consider the case when one of the molecules is stretched. The spacing between consecutive basepairs is ηa0, where the stretching factor η > 1. For RecA-coated DNA, η = 3/2. This is shown in Fig. 2, C and D. The stretching has two effects on the homologous alignment. First, as shown in Fig. 2 C, a homologously aligned basepair will be the only homologously aligned pair. The molecules immediately get out-of-register and the alignment is lost. Second, if we again displace one of the molecules a distance a0, we get Fig. 2 D. Now, unlike the previous case, a homologous alignment is preserved. The basepair originally homologously aligned is now out of alignment, but two nearby bases have moved into homologous alignment. The behavior is analogous to the operation of a Vernier scale or a slide rule. Unlike the situation when both molecules have the same basepair spacing, the homologous alignment is stable with respect to changes in the relative positions of the two DNA molecules. This is a key property which is essential to our reasoning. Although homologous alignment between one stretched and one unstretched DNA molecule occurs at only one basepair, there will always be one homologously aligned basepair ready to initiate strand exchange.

Homology alignment and recognition model

To show how this is of value for RecA activity, we need a model of how homologous alignment and recognition occur. We define two substrates, ℛ and 𝒟. ℛ is a RecA-coated ssDNA molecule J bases long. 𝒟 is a very long B-form dsDNA molecule which contains a region homologous to ℛ.

We make several comments about the energetics involved in recombination. First, since the process can occur without ATP hydrolysis, any suggested mechanism must function in the absence of an energy source. This means diffusion and thermal fluctuations must be sufficient to drive the process. It also means that the energy of the substrates ℛ and 𝒟 must be higher than the energy of the hybrid DNA molecule and displaced DNA strand, but lower than the energy of the products of an attempt to exchange strands nonhomologously.

To compare bases, the DNA molecules must be brought into close physical proximity, so some segment of 𝒟 must enter the filament of ℛ through the helical groove. There are binding sites for more than one strand of DNA within the RecA filament, meaning the potential energy of this invading segment decreases as it enters the filament.

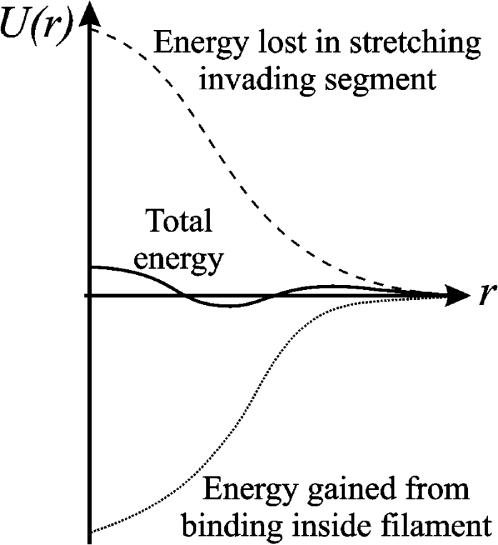

Homology recognition requires that the invading segment be stretched to keep its bases in register with those of ℛ. We assume that this happens simultaneously with the movement of the invading segment into the filament. This will have an energy cost of ∼0.7 kBT per basepair. For more than a few basepairs this will be large compared to the energies of the thermal fluctuations which drive the process. This can be overcome if the energy from binding the invading segment within the filament remains close to the energy needed to stretch it at all times as it enters the filament. This is shown qualitatively in Fig. 3. In that case, the net energy change of the invading segment as it simultaneously moves into the filament and is stretched by 50% will remain small. The combined process, and its reverse, are then easily accessible to thermal fluctuations.

FIGURE 3.

Qualitative sketch of the potential energy U of an invading segment as a function of a reaction coordinate r corresponding roughly to the distance of the invading segment from the binding site within the filament. (Dashed) Energy needed to stretch the invading segment; (dotted) energy gained from binding inside the filament; and (solid) total reaction energy.

The requirement that the stretching and binding energies nearly cancel at the end points of the reaction would ensure only that the thermodynamic difference between these states is small. We have additionally stipulated that the stretching of the invading segment occur simultaneously with its approach to the binding site within the filament and that the stretching and binding energies very nearly cancel throughout the entire process. These features ensure that not only is the thermodynamic difference between the states small, but that the energy barrier between them is small as well. This allows the kinetics of the transition between these states to be very fast, even when the transitions are driven only by thermal fluctuations.

Finally, consider the energetics involved in checking for complementarity between a base of the DNA within ℛ and an adjacent base on the invading segment by attempting to exchange basepairing partners. This could be accomplished by rotating the bases relative to the sugar phosphate backbone (Nishinaka et al., 1997, 1998), which is accessible to thermal energies. Stretching of the DNA will have largely eliminated base-stacking interactions, so the energy barrier will be dominated by the need to break the hydrogen bonds of the original Watson-Crick basepairs. This will be easier for A:T basepairs, with two hydrogen bonds each, than for G:C basepairs, with three, so we expect this part of the reaction to be dominated by A:T basepairs (Gupta et al., 1999). This is also accessible to thermal energies.

Process steps

We divide the process of aligning and identifying a homology between ℛ and 𝒟 into six steps.

Random initial contact between ℛ and 𝒟.

Rotation into a parallel but random and non-sequence-specific orientation.

Introduction of “invading segments” into the filament to position bases of 𝒟 close enough to bases of ℛ to allow for comparison and testing for complementarity.

- Testing for complementarity.

- Rejection of noncomplementary alignments.

- Stabilization of complementary alignments.

- Testing for homology.

- Expulsion of the invading segment in the absence of sufficient stabilization by additional complementary alignments.

- Extension of the invading segment when stabilized by enough additional complementary alignments.

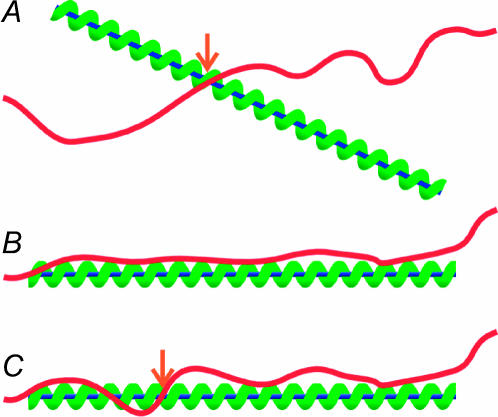

Extension of the hybrid DNA from a homologously aligned exchange nucleation point.

Step 1, the initial contact between the substrates, will occur at a point as shown in Fig. 4 A. Since this is a result of diffusion, the initial point of contact will be random. It has been noted in the literature that there is a weak, nonspecific (electrostatic) attraction between the substrates (Karlin and Brocchieri, 1996). This exerts a torque on the substrates, accomplishing step 2 by pulling them toward a loose, nonspecific parallel alignment as shown in Fig. 4 B.

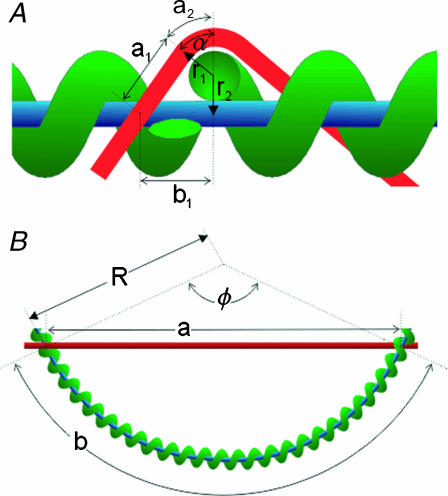

FIGURE 4.

(Red curve) dsDNA molecule (𝒟); (blue line) ssDNA; and (green helix) RecA filament (ℛ). (A) Contact at a point (orange arrow). An attractive interaction between 𝒟 and ℛ exerts a torque around this point. (B) The nonspecific parallel orientation produced by the torque in A. (C) An invading segment of 𝒟 enters the RecA filament of ℛ through the filament groove (orange arrow).

In a one-dimensional search, a simple model would be to wind a long section of 𝒟 into the filament nonspecifically and search for homology by sliding longitudinally within the filament. This avoids repeatedly winding short invading segments of 𝒟 in and out of the filament, but has other serious defects. These include experimental evidence that excludes significant sliding during the search process (Adzuma, 1998), and the observation that the longitudinal sliding of such large molecules would be very slow.

This would also create a “trap”. A long section of 𝒟 will only wind into the filament if its potential energy is lower inside than outside. In that case, it will not be readily removed from the filament once it has been wound in. The result is that any DNA heterologous to the DNA in ℛ acts as a suicide substrate by winding into the filament and blocking entry by homologous DNA. Impediment of the homologous recombination reaction with the human RecA homolog hRad51 under low salt conditions has been observed as a result of binding by heterologous dsDNA to the exterior of the nucleoprotein filament (Sigurdsson et al., 2001). The situation would be greatly exacerbated if the heterologous dsDNA were bound to the nucleoprotein filament more tightly, as would be the case for heterologous dsDNA bound within the filament. This poisoning of the reaction does not happen in vitro and would be lethal in vivo. For these and other reasons, we reject this model.

The above considerations compel us to postulate a model involving steps 3–5, repeatedly winding short invading segments of 𝒟 into and out of the filament as shown in Fig. 4 C. The invading segment must be stretched simultaneously with its movement into the filament so that it remains in register with the DNA within ℛ. As described in the previous subsection, this can be driven by the thermal fluctuations of 𝒟. Step involves testing for complementarity by some process such as the rotation of the A and T bases (Gupta et al., 1999) relative to the sugar phosphate backbone (Nishinaka et al., 1997, 1998). Hybrid basepairs formed this way must have a lower energy than the original basepairs, most likely as a result of the geometry to which they are constrained by the filament.

If the aligned bases of the hybrid molecule are not complementary, they cannot form a hybrid pair. Without a new basepairing, the energy of the rotated state will be higher than the energy of the original pairing, and the original pairing will quickly reform. In this manner, step 4a is accomplished.

If the aligned bases of the hybrid molecule are complementary, they can form a hybrid pair. We assume that the energy of the hybrid pair is only slightly lower than that of the original basepair. In this way the hybrid pair will be slightly stabilized as required by step 4b, but will eventually be disrupted by thermal fluctuations if further stabilization is not achieved. The return to the original pairing will not be completely prevented, but it will be delayed.

If the original basepairings reform as in step 4a, thermal fluctuations will quickly remove the invading segment from the filament. The search for homology between ℛ and 𝒟 has failed at this particular point along their lengths. If a hybrid pair forms as in step 4b, the slight stabilization of the position of the invading segment within the filament will allow time in which thermal fluctuations can introduce more of 𝒟 into the filament, lengthening the invading segment.

There are then two possibilities. If, as in step 5a, ℛ and 𝒟 are not homologously aligned at this point, there will be only occasional, fortuitous complementary alignments of A and T bases. This will provide little or no additional stabilization of the position of the invading segment within the filament. Such minimal stabilization will be insufficient to prevent the eventual disruption of these serendipitous hybrid pairs and thermal fluctuations will remove the invading segment from the filament.

Step 5b occurs if ℛ and 𝒟 are homologously aligned at this point, in which case every A:T pair of 𝒟 which enters the filament can make a small further contribution to stabilizing the presence of the invading segment within the filament. This allows time for even more of 𝒟 to enter the filament as a result of thermal fluctuations, adding further stabilization. This region now constitutes a nucleation point for the strand exchange reaction from which the entire homologous region of 𝒟 will be wound into the filament. This is a very stable state, and will persist long enough for the G:C pairs to break their three hydrogen bonds and exchange basepairing partners, forming hybrid G:C pairs and completing the strand exchange reaction.

Advantages from stretching one molecule

The minimal energy costs of steps through allow 𝒟 and ℛ to be rapidly and efficiently searched for a homologous alignment. If there exists a point of homologous alignment, it will be found and will serve as a nucleation site from which the exchange reaction will extended throughout the entire homology. This reduces the problem to a question of how probable it is that there is a point of homologous alignment. Stretching of the DNA by RecA plays a crucial role by enhancing this likelihood.

Target size enhancement

To have a point of homologous alignment between two DNA molecules requires that they lie within a certain range of relative positions. We define the target size σ for homologous alignment as the range of longitudinal positions of one DNA molecule relative to another which result in the homologous alignment of at least one basepair. For two B-form DNA molecules, this requires great precision. The molecules must lie within ±a0/2 of an exact alignment so that σ = a0. If they do lie in this range then all the bases are homologously aligned, but this is not desirable. Later, we show that an extended region of homologous alignment poses serious problems.

This contrasts with the situation between 𝒟 and ℛ. When ℛ is stretched by a factor  the target size is greatly augmented. This is because of the phenomenon illustrated in Fig. 2. Recall what we saw there: given a homologous alignment between a base on an unstretched DNA molecule and a base on a stretched DNA molecule, moving one of the molecules relative to the other changed the location of the homologous alignment to a different pair of bases, but it did not destroy the alignment. The target size for a homologous alignment between a stretched DNA molecule and unstretched DNA molecule is the maximum range of positions of one of the molecules relative to the other which maintains some point of homologous alignment between them. For a region of homology J bases in length, the resulting expression (compare to Appendix A) is

the target size is greatly augmented. This is because of the phenomenon illustrated in Fig. 2. Recall what we saw there: given a homologous alignment between a base on an unstretched DNA molecule and a base on a stretched DNA molecule, moving one of the molecules relative to the other changed the location of the homologous alignment to a different pair of bases, but it did not destroy the alignment. The target size for a homologous alignment between a stretched DNA molecule and unstretched DNA molecule is the maximum range of positions of one of the molecules relative to the other which maintains some point of homologous alignment between them. For a region of homology J bases in length, the resulting expression (compare to Appendix A) is

|

(1) |

For two unstretched DNA molecules,  and

and

|

(2) |

exactly as expected. Note that this is a fixed, constant value which is unchanged by the length of the homology.

Now consider what happens if we use the known RecA value of  Equation 1 then gives us

Equation 1 then gives us

|

(3) |

Here at last we see in a clear, quantitative form the enormous advantage of stretching the DNA within ℛ. This expression scales linearly with the homology length. A modest 200 base homology gives

|

(4) |

This huge target size, already a 100-fold increase relative to two unstretched DNA molecules, offers an enormous advantage to the homology recognition process. It is achieved only because of the stretching of the DNA within the RecA filament.

Reaction rate

Knowing the target size allows us to estimate the reaction rate. The fact that the target size is proportional to the length of the region of homology produces an interesting and somewhat surprising result. In the absence of sliding (Adzuma, 1998) the reaction rate cannot exceed the diffusion limit, so the maximum “on rate” for the reaction is the Debye-Smoluchowski rate. Our target is a section of 𝒟, and is therefore a cylinder of length σ, but we approximate this by a spherical target of radius σ/2. We also estimate the diffusion constant of ℛ, which is a cylinder of length ℛ, by the diffusion constant for a sphere with a radius of ℓ/2. With these approximations we find

|

(5) |

This result is independent of the length of the homology and the spacing between consecutive base(pair)s in unstretched B-form DNA. It depends only on the temperature T, on the viscosity of the solution η, and on the stretching factor  The stretching factor for DNA within the RecA filament is

The stretching factor for DNA within the RecA filament is  and

and  Poiseuille at 20°C, so we have

Poiseuille at 20°C, so we have

The reaction rate for homologous alignment and recognition provides an opportunity to test the enhanced target size hypothesis. In the absence of target size enhancement the reaction rate should be roughly proportional to 1/J. Target size enhancement predicts that it should be relatively insensitive to J. Measurement of the reaction rates as a function of the length of ℛ should clearly distinguish between these alternatives.

PREVENTING MULTIPLE HOMOLOGOUS ALIGNMENTS

Topological trapping

If homologous strand exchange between two substrates is initiated at two or more separate points it will result in a problematic topological trapping of the reaction. To extend a region of hybrid DNA, at least one strand of the external dsDNA must wind into the RecA filament (Honigberg and Radding, 1998). If exchange between the substrates is initiated at two separate points, this motion produces compensating counterturns of the dsDNA around the outside of the filament, as shown in Fig. 5. Extending the hybrid DNA increases the number of counter turns while decreasing the length of dsDNA that forms them, which rapidly decreases the radius of the counterturns. This makes them very energetically expensive to produce, which eventually stops extension of the hybrid DNA.

FIGURE 5.

Topological trapping resulting from initiation of strand exchange at two separate points. (Red curve) dsDNA molecule (𝒟); (blue line) ssDNA; and (green helix) RecA filament (ℛ). (A) Homologous alignment at alignment regions 1 (left) and 2 (right). These are shown only at their initial point of closest approach but may be of arbitrary length, e.g., region 1 may extend far to the left of what is shown. (B) Extending alignment region 1 to the right requires that 𝒟 be wound into the filament of ℛ. This entails rotation of 𝒟 and ℛ, forming counterturns of 𝒟 around ℛ. Because 𝒟 is fixed relative to ℛ at region 2, the counterturns are trapped between regions 1 and 2.

Structures resembling topological traps have been previously observed by electron microscopy and their potential significance for RecA activity has been discussed (Rice et al., 2001; Shan et al., 1996). We believe that the observed structures are most likely heterologous topological traps, in which the points of interaction between the two substrates are chiefly heterologous alignments or false-hits with at most one homologous alignment between any pair of substrates. A consideration of heterologous topological traps would require a very different treatment, and is beyond the scope of this article. We address here only homologous topological traps, in which all interactions between the substrates are homologous. For the remainder of this article, topological trap is to be understood to mean homologous topological trap only.

Such topological trapping can occur only if homologous strand exchange is able to begin at two points. If initiation of homologous strand exchange between the substrates at one point somehow prevents the initiation of homologous strand exchange at any other point along the same two substrates, topological trapping will never occur. To exploit this fact, the strand exchange machinery must impart to the entire length of the homology the information that homologous strand exchange has been initiated between them. The problem thus becomes finding a means of communicating over large distances the fact that no further homologous strand exchange process should be initiated.

We propose that a key function of the extended filament structure is to prevent topological trapping. Both the stiffness of the filament and the stretching of the DNA within it are essential to accomplishing this. Here, we give a qualitative explanation of how this works. A more detailed treatment appears in Appendix B.

Consider homologous exchange between 𝒟 and ℛ which has extended to encompass a segment of the substrates which we call the first region. Symmetry makes it sufficient to consider only the sections of the substrates to one side of the first region. Number the base(pair)s in ascending order to the right, beginning with the rightmost base(pair) in the first region. If the second contact is at base N on 𝒟, it will be homologously aligned only if it is at basepair N on ℛ. Formation of a second region produces a double-hit loop, half of which is composed of ssDNA from ℛ and the remainder of dsDNA from 𝒟. The second region is distinct if the RecA filament passes through the double-hit loop at least once, otherwise it only extends into the first region. We estimate the minimum work to form a double-hit loop for different N and show that the resulting Boltzmann factor is too small to permit the structure to form.

When the RecA filament passes through the double-hit loop M = 1 times we consider N small. This forms structure 1, shown in Fig. 6 A. As ℛ is very stiff it will behave as a rigid rod for small N, so we ignore any bending of ℛ. To align the Nth base(pair)s of 𝒟 and ℛ then requires stretching and bending 𝒟. We ignore the work necessary to bend 𝒟 and consider only the work needed to stretch it. This underestimates the work, producing a lower bound.

FIGURE 6.

Two homologous alignments between the same substrates. (Red curve) dsDNA molecule (𝒟); (blue line) ssDNA; and (green helix) RecA filament (𝒟). (A) Structure 1 (small N). The helix is cut to allow clearer labeling of the figure. The red and blue curves form the double-hit loop. The RecA filament (green) passes through this once. Because ℛ is much stiffer than 𝒟, we assume ℛ does not bend significantly on this length scale. (B) Structure 2 (large N). Now the RecA filament passes through the double-hit loop many times. Because ℛ is longer here, we include bending with a radius of curvature R. We ignore the bending of 𝒟 necessary to enter the RecA filament.

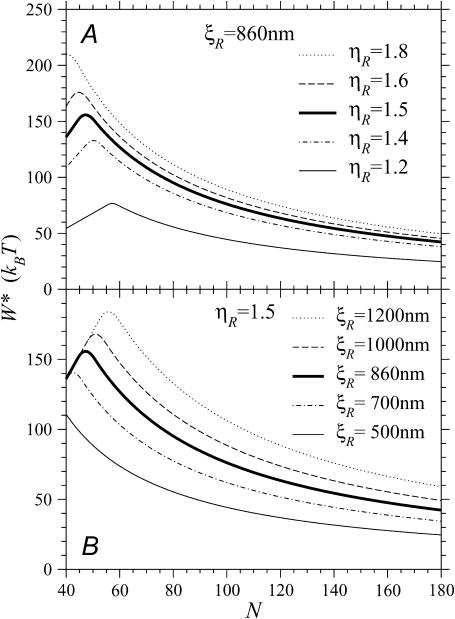

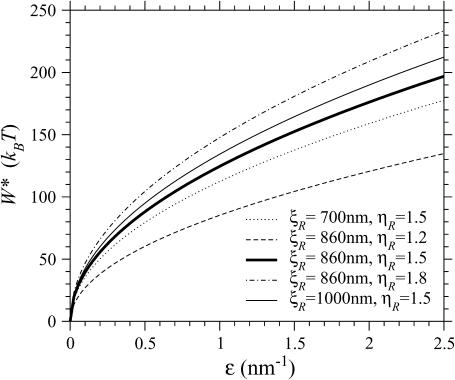

The minimum work W*(ηℛ) required to form structure 1 is calculated in Appendix B and plotted as a function of the stretching factor  in Fig. 7. W* increases with

in Fig. 7. W* increases with  making structure 1 more difficult to form. For RecA,

making structure 1 more difficult to form. For RecA,  and the work is minimized by α* = 0.84 and N* ≈ 25. We call this the minimal structure 1. The energy of this is ∼W* ≈ 170 kBT. The Boltzmann factor is

and the work is minimized by α* = 0.84 and N* ≈ 25. We call this the minimal structure 1. The energy of this is ∼W* ≈ 170 kBT. The Boltzmann factor is  so the probability of forming structure 1 is on the order of e−170. Formation of a second homologous alignment therefore does not occur for small N as a result of thermal fluctuations.

so the probability of forming structure 1 is on the order of e−170. Formation of a second homologous alignment therefore does not occur for small N as a result of thermal fluctuations.

FIGURE 7.

The minimum work W* required to form structure 1 as a function of the stretching factor  of the DNA within substrate ℛ relative to B-form DNA.

of the DNA within substrate ℛ relative to B-form DNA.

When the RecA filament passes through the double-hit loop M ≥ 2 times we must include the bending of ℛ, but we ignore the bending of 𝒟 as it enters or leaves the RecA filament. This shortens the path for 𝒟 and lengthens the radius of curvature for ℛ, both of which reduce the work, giving a lower limit on the work required to achieve the second alignment. This is structure 2, shown in Fig. 6 B. The minimum work W* to form structure 2 is calculated in Appendix B.

If  the expression for W* is complicated by the division of the parameter space into different regions. Fig. 8, A and B, are more informative. Fig. 8 A shows W*(N) with the persistence length of ℛ fixed at the physiological value of

the expression for W* is complicated by the division of the parameter space into different regions. Fig. 8, A and B, are more informative. Fig. 8 A shows W*(N) with the persistence length of ℛ fixed at the physiological value of  = 860 nm for various values of

= 860 nm for various values of  The curves all have a similar shape, with the amplitudes increasing with increasing

The curves all have a similar shape, with the amplitudes increasing with increasing  For small N, the minimal structure involves stretching 𝒟 without significantly bending ℛ. In this case,

For small N, the minimal structure involves stretching 𝒟 without significantly bending ℛ. In this case,

|

(6) |

where F0 is a known constant. Consequently, the left edges of these curves in Fig. 8 A are spaced linearly in proportion to  For the physiological value of

For the physiological value of  the minimal structure at first involves only stretching 𝒟, and W* forms a straight line which increases with N as in Eq. 6. This is because the larger N is, the more basepairs in 𝒟 must be stretched. As N increases, the length of the segment of ℛ between regions 1 and 2 increases and the work required to bend ℛ decreases. At

the minimal structure at first involves only stretching 𝒟, and W* forms a straight line which increases with N as in Eq. 6. This is because the larger N is, the more basepairs in 𝒟 must be stretched. As N increases, the length of the segment of ℛ between regions 1 and 2 increases and the work required to bend ℛ decreases. At  it becomes comparable to the work required to stretch 𝒟 and the minimal structure becomes a combination of bending ℛ and stretching 𝒟. As N increases further, the work to bend ℛ drops further, whereas the work to stretch 𝒟 continues to increase so bending ℛ becomes a steadily larger part of the process. W* curves downward as this happens, and by

it becomes comparable to the work required to stretch 𝒟 and the minimal structure becomes a combination of bending ℛ and stretching 𝒟. As N increases further, the work to bend ℛ drops further, whereas the work to stretch 𝒟 continues to increase so bending ℛ becomes a steadily larger part of the process. W* curves downward as this happens, and by  the minimal structure involves only bending ℛ and no stretching 𝒟. From here on, W* decreases when N increases as W* ∝ N−2.

the minimal structure involves only bending ℛ and no stretching 𝒟. From here on, W* decreases when N increases as W* ∝ N−2.

FIGURE 8.

W* as a function of N. (A) For various stretching factors  with the physiological persistence length of

with the physiological persistence length of  The thick curve shows the physiological case

The thick curve shows the physiological case  (B) For various persistence lengths

(B) For various persistence lengths  with the physiological stretching factor of

with the physiological stretching factor of  The thick curve shows the physiological case

The thick curve shows the physiological case

The location of the transition from the stretching 𝒟 regime with W* ∝ N to the bending ℛ regime with W* ∝ N−2 is influenced by  For larger

For larger  greater work is required to sufficiently stretch a given number of basepairs, making W* larger for larger values of

greater work is required to sufficiently stretch a given number of basepairs, making W* larger for larger values of  The work required to stretch 𝒟 thus becomes comparable to the work required to bend ℛ at smaller values of N, and the peak value of W* occurs at smaller N for larger values of

The work required to stretch 𝒟 thus becomes comparable to the work required to bend ℛ at smaller values of N, and the peak value of W* occurs at smaller N for larger values of

Fig. 8 B shows W*(N), with  fixed at the physiological value of

fixed at the physiological value of  for various values of

for various values of  The notable points here are that increasing

The notable points here are that increasing  makes it more difficult to bend ℛ, and therefore W* increases as

makes it more difficult to bend ℛ, and therefore W* increases as  increases. This also means that higher values of

increases. This also means that higher values of  push the transition from the stretching 𝒟 regime to the bending ℛ regime to higher values of N. For

push the transition from the stretching 𝒟 regime to the bending ℛ regime to higher values of N. For  the transition occurs at values of N which are off the left side of Fig. 8 B.

the transition occurs at values of N which are off the left side of Fig. 8 B.

From these figures and from the calculation we see that for N, W* remains too high for structure 2 to form as a result of thermal fluctuations. This is only the case because of the large values of  and

and  since smaller values of either or both of these decrease W* and make the structure more accessible to random thermal processes. Since our calculation has produced only a lower limit on W* we can be confident that this conclusion is valid for values of N which are at least this large.

since smaller values of either or both of these decrease W* and make the structure more accessible to random thermal processes. Since our calculation has produced only a lower limit on W* we can be confident that this conclusion is valid for values of N which are at least this large.

For N, the minimal structure is dominated by bending ℛ, and we can ignore stretching of 𝒟. By contrast, we can no longer ignore the work required to separate 𝒟 and ℛ against the nonspecific attractive force which initially brought them into alignment. This work will be proportional to the length of the substrates between regions one and two. We use ɛ for the constant of proportionality. The work to form structure 2 in this case is calculated in Appendix B. The function is found to have a minimum with respect to N at

|

(7) |

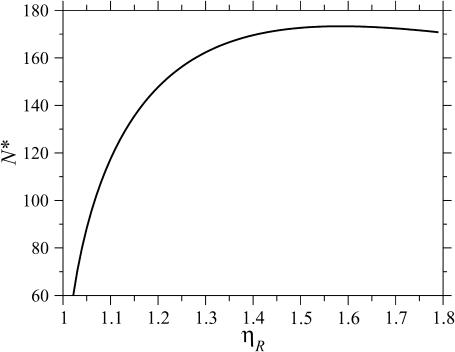

This value for N produces the minimal structure 2 for large N. The behavior of N* in Eq. 7 with respect to  as shown in Fig. 9. N* has a maximum with respect to

as shown in Fig. 9. N* has a maximum with respect to  This occurs at some value

This occurs at some value  which is found in the Appendices to be

which is found in the Appendices to be  strikingly close to the physiological value of

strikingly close to the physiological value of  This value maximizes the distance between the first and second regions for which the work required to form structure 2 is minimized.

This value maximizes the distance between the first and second regions for which the work required to form structure 2 is minimized.

FIGURE 9.

N*, the value of N at which the energy required to form structure 2 is minimized, as a function of the stretching factor  Note that N* has a maximum with respect to

Note that N* has a maximum with respect to  at

at  very near the physiological value of

very near the physiological value of

Upon using N* in the expression for work, we obtain the minimum value

|

(8) |

shown in Fig. 10. The work W* increases as the square root of ɛ. For the physiological values of  and

and  W* already reaches ∼50 kBT by

W* already reaches ∼50 kBT by  so structure 2 will not form as a result of thermal motions for the physiological values of

so structure 2 will not form as a result of thermal motions for the physiological values of  and

and  when ɛ ≳ 0.2 nm−1. W* also increases as the square root of

when ɛ ≳ 0.2 nm−1. W* also increases as the square root of  and increases with

and increases with  in a more complicated fashion. Sufficiently small values of

in a more complicated fashion. Sufficiently small values of  or

or  would produce values of W* which would be more accessible to thermal energies.

would produce values of W* which would be more accessible to thermal energies.

FIGURE 10.

The minimum work W* to form structure 2 for N > 60 as a function of the constant of proportionality ɛ for various stretching factors  and persistence lengths

and persistence lengths  The thick curve shows the physiological case

The thick curve shows the physiological case  and

and

The probability that a second, local region of homology aligns N basepairs away is ∝ N−6. This small probability forms an “entropic” barrier to formation of a second region of homology. However, since  the value of N for which the energetic obstacle to alignment is smallest, N*, is made as large as possible, maximizing the entropic obstacle to alignment. The two processes are “tuned” to work in a complementary fashion, providing a further form of selection pressure for the maintenance of stretching of the DNA by the RecA filament and, specifically, to a value close to the physiological value of

the value of N for which the energetic obstacle to alignment is smallest, N*, is made as large as possible, maximizing the entropic obstacle to alignment. The two processes are “tuned” to work in a complementary fashion, providing a further form of selection pressure for the maintenance of stretching of the DNA by the RecA filament and, specifically, to a value close to the physiological value of

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

RecA-facilitated homologous recombination derives two advantages from the stiff extended filament and the stretching of the DNA within the filament. The first is a great increase in the efficiency of the homology search and recognition process. This is a consequence of the increase in σ, the target size for homologous alignment between the substrates. For a region of homology J bases in length, stretched by a factor  we have

we have

|

(9) |

where a0 is the spacing of B-form DNA. For  this is σ = (J + 1)a0/2. This huge σ allows large segments of the substrates to be checked for homology without the need for sliding. The second advantage is the prevention of homologous topological trapping. Molecules undergoing homologous strand exchange are kept in close proximity by the region of hybrid DNA being formed. This greatly enhances the probability that they will contact each other at additional points. Without the stretching of the DNA within the extended filament, these secondary contacts would often be in homologous alignment and capable of initiating a second homologous strand exchange reaction. This would lead to a trapped state in which a region of counter-wound DNA is trapped between two regions of hybrid DNA, preventing completion of the exchange reaction.

this is σ = (J + 1)a0/2. This huge σ allows large segments of the substrates to be checked for homology without the need for sliding. The second advantage is the prevention of homologous topological trapping. Molecules undergoing homologous strand exchange are kept in close proximity by the region of hybrid DNA being formed. This greatly enhances the probability that they will contact each other at additional points. Without the stretching of the DNA within the extended filament, these secondary contacts would often be in homologous alignment and capable of initiating a second homologous strand exchange reaction. This would lead to a trapped state in which a region of counter-wound DNA is trapped between two regions of hybrid DNA, preventing completion of the exchange reaction.

The extended filament prevents homologous alignment at secondary contacts. Homologously aligned secondary contacts can only form through some combination of stretching the DNA external to the filament and bending the filament itself. For moderate distances from the point at which homologous exchange is occurring, thermal fluctuations are incapable of sufficiently bending or stretching the filament for a second hit to occur. For larger distances, thermal fluctuations are also unlikely to separate the locally aligned strands held together by nonspecific electrostatic forces. The interplay between stiffness of the filament and the stretching of the DNA within it ensures that homologous strand exchange between two substrate molecules is initiated at only one point.

Both the stiffness of the filament and the extension of the DNA within it are necessary features of the recombination apparatus. Without them, locating and aligning regions of homology between two DNA molecules would be a slow and inefficient process, and the exchange reaction would be prone to topological traps which would prevent completion of the reaction and resolution of the products. These effects provide a selection pressure to preserve the extended filament as a feature of homologous DNA recombination facilitated by RecA and its homologs.

Acknowledgments

K.K. and T.C. acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation through grant DMS-0206733. K.K. and R.B. acknowledge support from the University of California-Los Angeles Dean's Funds.

APPENDIX A: KINETIC PERFECTION IN THE HOMOLOGY SEARCH

Consider 𝒟 and ℛ as defined in the text. The center-to-center base(pair) spacing is a0 in 𝒟 and  a0 in ℛ, so an N basepair segment has length

a0 in ℛ, so an N basepair segment has length

|

(A1) |

|

(A2) |

If 𝒟 and ℛ intersect at a point and rotate around this point until parallel, at most one base within ℛ and a basepair in 𝒟 will be homologously aligned. We wish to determine if this parallel orientation produces an alignment.

To define “aligned” we consider only the longitudinal positions of 𝒟 and ℛ. A base on ℛ is aligned with whichever basepair on 𝒟 is closest to it in the longitudinal direction. When the aligned base and basepair are homologous they are homologously aligned.

To quantify this, first note that the center-to-center distance between consecutive basepairs of 𝒟 is a0. Let the longitudinal distance between the centers of the kth basepair on 𝒟 and the lth base on ℛ be δk,l. These are aligned if

|

(A3) |

Denote the positions of initial contact by  along 𝒟 and by

along 𝒟 and by  along ℛ. The parallel orientation is achieved by rotating around

along ℛ. The parallel orientation is achieved by rotating around  and

and  so these completely determine the relative positions of 𝒟 and ℛ once they are parallel. It is sufficient to fix

so these completely determine the relative positions of 𝒟 and ℛ once they are parallel. It is sufficient to fix  and ask what values of

and ask what values of  produce a homologous alignment in the parallel orientation. If the position

produce a homologous alignment in the parallel orientation. If the position  is moved a distance d along 𝒟, 𝒟 will be displaced relative to ℛ by this same distance d in the parallel orientation. The range of

is moved a distance d along 𝒟, 𝒟 will be displaced relative to ℛ by this same distance d in the parallel orientation. The range of  which produces a homologous alignment is therefore the same as the range of longitudinal positions of 𝒟 relative to ℛ which will produce an homologous alignment.

which produces a homologous alignment is therefore the same as the range of longitudinal positions of 𝒟 relative to ℛ which will produce an homologous alignment.

Consider 𝒟 and ℛ as shown in Fig. 11 A. Number the basepairs beginning with 1 at the leftmost basepair in the region of homology. Here, 𝒟 is as far to the left as possible while maintaining a homologous alignment between 𝒟 and ℛ. The homologous alignment is between base and basepair 1, and the center of basepair 1 is a0/2 to the left of the center of base 1. Fig. 11 B shows an enlarged view of this.

FIGURE 11.

Dark green helix, RecA filament, light green line inside helix, ssDNA (ℛ); red and blue lines with light green segments, dsDNA(𝒟). ℛ is arbitrarily chosen to be 11 bases in length. The light green region of 𝒟 is homologous to ℛ. (A) 𝒟 is as far to the left as possible while maintaining a homologous alignment between 𝒟 and ℛ (between base and basepair 1). (B) Closeup of the homologously aligned base and basepair in A. (C) Effect of shifting 𝒟 to the right a distance a0/2. (D) Effect of shifting 𝒟 further to the right, this time by a distance a0. (E) Effect of nine more consecutive shifts of 𝒟 to the right by a distance a0. (F) Effect of a final shift of 𝒟 to the right by a distance a0/2.

Moving 𝒟 to the right by a0/2 gives Fig. 11 C, where the centers of basepair 1 and base 1 are exactly aligned. Moving 𝒟 to the right by  then produces Fig. 11 D, in which the centers of basepair 2 and base 2 are exactly aligned. Each displacement of 𝒟 to the right by

then produces Fig. 11 D, in which the centers of basepair 2 and base 2 are exactly aligned. Each displacement of 𝒟 to the right by  now increments by 1 the base and basepair whose centers are exactly aligned. Starting with Fig. 11 C and repeating this motion (J−1) times produces Fig. 11 E, in which the centers of basepair J and base J are exactly aligned. A final movement of 𝒟 to the right by a0/2 produces Fig. 11 F, where 𝒟 is as far to the right relative to ℛ as is possible while still maintaining a homologous alignment between them.

now increments by 1 the base and basepair whose centers are exactly aligned. Starting with Fig. 11 C and repeating this motion (J−1) times produces Fig. 11 E, in which the centers of basepair J and base J are exactly aligned. A final movement of 𝒟 to the right by a0/2 produces Fig. 11 F, where 𝒟 is as far to the right relative to ℛ as is possible while still maintaining a homologous alignment between them.

The target size σ is the range of longitudinal positions of 𝒟 relative to ℛ which produces a homologous alignment between them. This is the change in the position of 𝒟 in going from Fig. 11, A–F, which is given in Eq. 1. If  has the known RecA value of

has the known RecA value of  we get σ = (J + 1)a0/2, which scales as the length of the region of homology.

we get σ = (J + 1)a0/2, which scales as the length of the region of homology.

From σ we can estimate the reaction rate. With no sliding (Adzuma, 1998), diffusion limits the maximum “on rate” ka for the reaction to the Debye-Smoluchowski rate. Our target is cylindrical, but the magnitude should be reasonably approximated if we substitute our target size for the diameter of a spherical target, r → σ/2, giving  where D3 is the three-dimensional diffusion constant. The length of ℛ is

where D3 is the three-dimensional diffusion constant. The length of ℛ is

|

(A4) |

Upon substituting this for the diameter of a spherical molecule, r → ℓ/2, the three-dimensional diffusion constant in a solvent with viscosity η, becomes D3 = kBT/(3πηℓ). Assuming J is reasonably large,  and ka is given by Eq. 5.

and ka is given by Eq. 5.

APPENDIX B: DOUBLE-HIT PROBABILITY IN THE RecA RECOMBINATION SYSTEM

If N is small we consider structure 1 as shown in Fig. 6 A. Define  and

and  as the extension of 𝒟 and ℛ relative to the length of B-form DNA. Let a0 be the spacing of basepairs in B-form DNA and denote the persistence lengths of 𝒟 and ℛ by

as the extension of 𝒟 and ℛ relative to the length of B-form DNA. Let a0 be the spacing of basepairs in B-form DNA and denote the persistence lengths of 𝒟 and ℛ by  and

and  respectively. These have the numerical values a0 = 0.34 nm,

respectively. These have the numerical values a0 = 0.34 nm,  and

and  We model the RecA filament as a cylinder of radius rRecA whose axis follows a helical path of radius

We model the RecA filament as a cylinder of radius rRecA whose axis follows a helical path of radius  Treating 𝒟 as a cylinder of radius

Treating 𝒟 as a cylinder of radius  the closest approach of the center of 𝒟 to the center of ℛ will be the sum of their radii, which we denote by

the closest approach of the center of 𝒟 to the center of ℛ will be the sum of their radii, which we denote by

We wish to determine the minimum work required to form structure 1. We ignore bending of ℛon this length scale and also ignore the work required to bend 𝒟. We calculate the work solely from the stretching of 𝒟, making our calculation of the work a lower bound.

The angle α can be varied to find the minimal-energy form of structure 1, the form produced with the minimum possible work, subject to two constraints. Steric hindrance between the RecA filament and 𝒟 at the points where it enters the RecA filament requires α ≥ π/5, whereas other physical considerations show that the minimum energy can occur only for α ≤ π/2.

Both regions can simultaneously be in homologous alignment only if N satisfies

|

(B1) |

Since a2 = r1α, trigonometry demands

|

(B2) |

|

(B3) |

We make the simplification of assuming that the force to stretch a dsDNA is

|

(B4) |

Here, F0 ≈ 20 kBT/nm, but we leave this parameter free for the present.

Above  Eq. B4 in not valid. Here, the dsDNA melts whereas the force required to stretch it rises rapidly. Further stretching breaks the sugar phosphate backbones of the DNA strands. Although our calculation may produce values of

Eq. B4 in not valid. Here, the dsDNA melts whereas the force required to stretch it rises rapidly. Further stretching breaks the sugar phosphate backbones of the DNA strands. Although our calculation may produce values of  we are not concerned. We only wish to show that the minimal form of structure 1 does not form as a result of random thermal fluctuations, and our calculation will still accomplish this.

we are not concerned. We only wish to show that the minimal form of structure 1 does not form as a result of random thermal fluctuations, and our calculation will still accomplish this.

Using Eq. B4 for  the work required to stretch the dsDNA to a final extension

the work required to stretch the dsDNA to a final extension  (in units of kBT) is

(in units of kBT) is

|

Under our approximations, this is the only contribution to the total work. Using the expressions in Eq. B3, W becomes a function of the single variable α as

|

(B5) |

Minimizing this with respect to α we find  which gives us the equations

which gives us the equations

|

(B6) |

With the known values of the constants, Eq. B6 becomes

|

(B7) |

which is plotted in Fig. 7. At the physiological value of  for the RecA system,

for the RecA system,  and W* = 174 kBT. The probability of the system being in the minimal form of structure 1 is on the order of e−174. This vanishing probability persists for

and W* = 174 kBT. The probability of the system being in the minimal form of structure 1 is on the order of e−174. This vanishing probability persists for

For somewhat larger N we consider structure 2 as shown in Fig. 6 B. The angle α no longer enters the calculation directly, and we deal with the angle φ. The parameters are subject to the restrictions  and

and

The exchange regions can simultaneously be in homologous alignment if N satisfies

|

(B8) |

from which we find

The radius of curvature R for structure ℛ is related to the opening angle φ by

|

(B9) |

whereas trigonometry gives

|

(B10) |

Upon using the above,

|

(B11) |

Using Eqs. B8 and B9 we also find

|

(B12) |

We can now calculate the work required to form structure 2. We will vary N and φ to minimize this. We can then vary  and

and  (subject to

(subject to  and

and  ) to examine their effects on the system. The work to form structure 2 comes from three terms: stretching 𝒟, bending ℛ, and separating 𝒟 from ℛ against the nonspecific attractive force by which they were initially aligned.

) to examine their effects on the system. The work to form structure 2 comes from three terms: stretching 𝒟, bending ℛ, and separating 𝒟 from ℛ against the nonspecific attractive force by which they were initially aligned.

The force required to stretch 𝒟 to  times its B-form contour length is approximately

times its B-form contour length is approximately

|

(B13) |

Since  is unphysical we impose

is unphysical we impose  to ensure that this does not occur. The work to stretch 𝒟 is thus

to ensure that this does not occur. The work to stretch 𝒟 is thus

|

(B14) |

Using Eq. B11 and expressing the regime boundaries in terms of φ, this becomes (in units of kBT)

|

(B15) |

The work to bend ℛ into the circular arc in structure 2 is

|

(B16) |

Using Eqs. B9 and B12 and the fact that  (in units of kBT), gives

(in units of kBT), gives

|

(B17) |

There is a nonspecific attractive interaction between 𝒟 and ℛ. The work to pull 𝒟 and ℛ apart is approximately proportional to the length of ℛ between the exchange regions. For intermediate N we ignore an energetic contribution  which underestimates the work and produces a lower bound,

which underestimates the work and produces a lower bound,

|

(B18) |

Upon minimizing the work W(φ) with respect to the angle φ, we find φ* and W(φ*) equal to

|

(B19) |

This function is plotted in Fig. 8, A and B, using standard values for a0, F0, and kBT. From Fig. 8, A and B, it is clear that by N ≈ 60 the minimal form of structure 2 is dominated by bending ℛ. For large N, (≳60), the interaction energy can no longer be ignored, but now we always have  The total work thus simplifies to

The total work thus simplifies to

|

(B20) |

The separation between exchange regions which minimizes this and the corresponding minimum work is

|

(B21) |

and

|

(B22) |

These are plotted in Figs. 9 and 10, respectively. We also note that N* is monotonic with respect to the  and ɛ, but has a maximum with respect to

and ɛ, but has a maximum with respect to  at

at

References

- Adzuma, K. 1998. No sliding during homology search by RecA protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273:31565–31573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R. C., E. Folta-Stogniew, S. O'Malley, M. Takahashi, and C. M. Radding. 1999. Rapid exchange of A:T basepairs is essential for recognition of DNA homology by human Rad51 recombination protein. Mol. Cell. 4:705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegner, M., S. B. Smith, and C. Bustamante. 1999. Polymerization and mechanical properties of single RecA-DNA filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:10109–10114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuser, J., and J. Griffith. 1989. Visualization of RecA protein and its complexes with DNA by quick-freeze/deep-etch electron microscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 210:473–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg, S., and C. Radding. 1998. The mechanics of winding and unwinding helices in recombination: torsional stress associated with strand transfer promoted by RecA protein. Cell. 54:525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin, S., and L. Brocchieri. 1996. Evolutionary conservation of RecA genes in relation to protein structure and function. J. Bacteriol. 178:1881–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishinaka, T., Y. Ito, S. Yokoyama, and T. Shibata. 1997. An extended DNA structure through deoxyribo-base stacking induced by RecA protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:6623–6628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishinaka, T., A. Shinohara, Y. Ito, S. Yokoyama, and T. Shibata. 1998. Basepair switching by interconversion of sugar puckers in DNA extended by proteins of RecA-family: a model for homology search in homologous genetic recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:11071–11076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca, A. I., and M. M. Cox. 1997. RecA protein: structure, function, and role in recombinational DNA repair. Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 56:129–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, K. P., A. L. Eggler, P. Sung, and M. M. Cox. 2001. DNA pairing and strand exchange by the Escherichia coli RecA and yeast Rad51 proteins without ATP hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38570–38581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan, Q., M. M. Cox, and R. B. Inman. 1996. DNA strand exchange promoted by RecA K72R. J. Biol. Chem. 271:5712–5724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsson, S., K. Trujillo, B.-W. Song, S. Stratton, and P. Sung. 2001. Basis for avid homologous DNA strand exchange by human Rad51 and RPA. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8798–8806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, M., and B. Norden. 1994. Structure of RecA-DNA complex and mechanism of DNA strand exchange reaction in homologous recombination. Adv. Biophys. 30:1–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X., and E. H. Egelman. 1992. Structural data suggest that the active and inactive forms of the RecA filament are not simply interconvertible. J. Mol. Biol. 227:334–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]