Abstract

Crystallographic studies of K+ channels in the closed (KcsA) and open (MthK) states suggest that Gly99 (KcsA numbering) in the inner helices serves as a gating hinge during channel activation. However, some P-loop channels have larger residues in the corresponding position. The comparison of x-ray structures of KcsA and MthK shows that channel activation alters backbone torsions and helical H-bonds in residues 95–105. Importantly, the changes in Gly99 are not the largest ones. This raises questions about the mechanism of conformational changes upon channel gating. In this work, we have built a model of the open KcsA using MthK as a template and simulated opening and closing of KcsA by constraining C-ends of the inner helices at a gradually changing distance from the pore axis without restraining mobility of the helices along the axis. At each imposed distance, the energy was Monte Carlo-minimized. The channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories arrived to the structures in which the backbone geometry was close to that seen in MthK and KcsA, respectively. In the channel-opening trajectory, the constraints-induced lateral forces caused kinks at midpoints of the inner helices between Val97 and Gly104 but did not destroy interdomain contacts, the pore helices, and the selectivity filter. The simulated activation of the Gly99Ala mutant yielded essentially similar results. Analysis of interresidue energies shows that the N-terminal parts of the inner helices form strong attractive contacts with the pore helices and the outer helices. The lateral forces induce kinks at the position where the helix-breaking torque is maximal and the intersegment contacts vanish. This mechanism may be conserved in different P-loop channels.

INTRODUCTION

Understanding the gating mechanisms is one of the most interesting problems in molecular physiology of ion channels (see Hille, 2001). A gate is a part of the pore-forming domain of the channel protein that obstructs the ion permeation when the channel is closed. In response to the channel-activation stimulus, the gate opens and no longer blocks the conduction pathway. For K+ channels, the intracellular location of the activation gate was predicted basing on the state-dependent action of internally applied ligands (Armstrong, 1974). The employment of the substituted-cysteine accessibility method revealed the gate of K+ channels as a narrowing formed by the cytoplasmic parts of the S6 segments (Liu et al., 1997). The importance of the S6 segments (also called inner helices) for K+ channel gating was further demonstrated by recent mutational studies (Sadja et al., 2001; Yi et al., 2001; Hackos et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2002; Sukhareva et al., 2003).

Crystallographic studies have provided atomic-level structures of bacterial K+ channels in the closed (Doyle et al., 1998; Kuo et al., 2003) and open (Jiang et al., 2002a, 2003) states. The comparison of KcsA and MthK, as representatives of the closed and open states of bacterial K+ channels, suggests a mechanism of channel activation (Jiang et al., 2002a,b). In the closed channel, the inner helices are straight. The helices have a radial slope and converge at the intracellular bundle narrowing. Hydrophobic residues lining the narrowing form the closed gate that is impermeable to ions. In the open channel, the inner helices are kinked. Their C-ends diverge to form a wide vestibule (Fig. 1). Jiang et al. (2002b) suggested that lateral forces applied to C-ends of the inner helices induce channel opening.

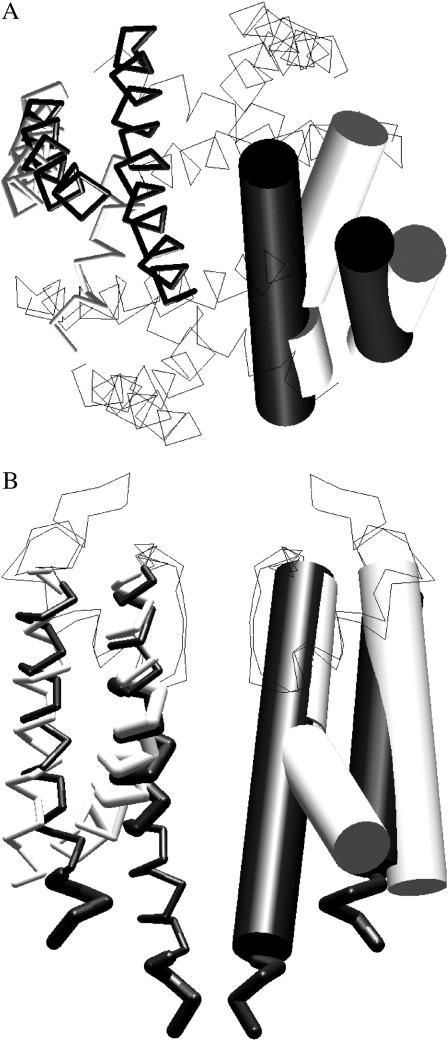

FIGURE 1.

The intracellular (A) and side (B) views of the superimposition of KcsA (solid) and MthK (shaded) structures. In the side view, only two nonadjacent subunits are shown, and in the top view P-loops are not shown. The inner and the outer helices are shown as cylinders in one subunit and as sticks in the opposite subunit. The N-ends of the outer helices (residues 23–28), C-ends of inner helices (residues 116–119), and the kink region (residues 95–105) are shown as thick sticks.

Intermediate states between the open and closed conformations of the channel remain unknown raising questions about the forces that cause conformational transitions, interactions that determine the transition pathway, and possible energy barriers between the closed and open states. These questions are difficult to address in experimental studies. On the other hand, the availability of experimental structures of channels in the open and closed states opens an avenue for molecular modeling approaches that can be used to simulate conformational rearrangements in the channels during their gating. Molecular dynamics (MD) is widely used to predict conformational transitions in macromolecules. Gullingsrud and Schulten (2003) used a steered MD method to simulate activation of a mechanosensitive channel. Biggin and Sansom (2002) simulated the KcsA channel opening by gradually increasing the volume of a dummy particle positioned in the pore at the gate region. The particle caused the protein perturbation from the closed state toward new states in which the pore diameter at the gate was increased. This work presents an interesting approach of simulating large-scale conformational transitions in ion channels. However, in view of later resolved structures of the open K+ channels, MthK and KvAP, the problem of in silico activation of K+ channels should be readdressed.

The observation that Gly99 of KcsA is located at the kink region and that this Gly is conserved among K+ channels allowed Jiang et al. (2002b) to suggest that the conserved Gly plays a key role in the channel gating, serving as a “gating hinge”. However, comparison of the kink region in KcsA and MthK shows that significant changes in the backbone torsions and helical H-bonds involve a big region between residues 95 and 105. Surprisingly, changes of torsions at Gly99 are not the largest among these residues. The results of comparison of backbone torsions should be treated with caution in view of rather low resolution of the x-ray structures of KcsA and MthK, but the latter problem also suggests that possible contribution of residues around Gly99 to the gating hinge should be investigated. Some P-loop channels whose pore domain is believed to have the architecture similar to that of K+ channels do not have Gly in the corresponding position (see Zhorov and Tikhonov, 2004). In particular, this concerns some repeats of Na+ and Ca2+ channels as well as glutamate-gated channels including the K+ selective GluR0 channel (Chen et al., 1999) that exhibits higher sequence homology with K+ channels than Na+ and Ca2+ channels. This suggests that either the activation mechanism of the channels lacking the conserved glycine is different from the activation mechanism of bacterial K+ channels or that the conserved glycine is not a critical determinant of channel gating.

The first possibility seems unlikely: increasing evidence suggest that C-terminal halves of the inner helices in P-loop channels are involved in the gating process. For example, replacements at this region affect gating of glutamate receptors (Kohda et al., 2000; Jones et al., 2002). Kashiwagi et al. (2002) demonstrated that in the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA)-type glutamate receptors, replacement of Thr107 (KcsA numbering) generates constitutively open channels. In the Na+ channel, substitution of the conserved Gly does not result in significant changes in activation, whereas some other replacements at the inner helix bundle produce large effects (Yarov-Yarovoy et al., 2002). Thus, the molecular determinants of the conformational transition between the open and closed state remain unclear. The role of Gly99 in the gating process should be further investigated.

In this work, we simulated KcsA opening by applying lateral forces to the C-ends of the inner helices. The protein conformation was allowed to change under the influence of these forces with a small step. At each step, the protein energy was Monte Carlo (MC)-minimized. Importantly, no constraints were applied besides those that simulated the lateral forces. The lateral forces caused the inner helices to move and kink at the midpoint region between Val97 and Gly104 without destroying interdomain contacts, the selectivity filter, and the secondary structure of the outer helices and pore helices as well as the inner helices beyond the kink region. The energetic and geometric characteristics of the in silico activated channel were found to be similar with the corresponding characteristics of the open-KcsA model built using MthK as a template. Analysis of the channel-opening trajectory shows that the N-terminal halves of the inner helices form stable contacts with the pore helices and the outer helices. The kink develops at those residues where the helix-breaking torque is maximal and the intersegment contacts disappear.

METHODS

In this study, the conformational energy expression included van der Waals, electrostatic, solvation, and torsion components. Nonbonded interactions were calculated with the AMBER force field (Weiner et al., 1984). Electrostatic interactions were calculated with a distance-dependent dielectric ɛ = r, where ɛ is the dielectric value between two atoms, and r is the distance between these atoms. A cutoff distance of 8 Å was used to build the interactions list, which was updated at each 50th energy minimization. The hydration energy was calculated by the implicit-solvent method (Lazaridis and Karplus, 1999). In addition to the inner pore, cytoplasmic and extracellular parts of the protein, the lipid-exposed residues of the outer helices were also considered hydrated. Obviously, the exterior residues of the outer helices are not hydrated in the membrane, but their partial hydration in the process of the protein crystallization does not affect significantly both open and closed conformations of the channel. We therefore assume that hydration of the lipid-facing residues in our models does not affect major results of the simulation.

KcsA includes many ionizable residues. Local environment can significantly shift standard pKa values of titratable groups. Nonstandard ionization states have been proposed for several KcsA residues (Berneche and Roux, 2002; Luzhkov and Aqvist, 2000; Ranatunga et al., 2001). Since the ionization state is conformation-dependent, its proper treatment in simulation of large-scale conformational changes such as the channel gating becomes too complex. Therefore, as a first approximation, we considered all ionizable residues in their neutral forms (Momany et al., 1975). Three K+ ions seen in the x-ray structure of KcsA (Doyle et al., 1998; PDB code 1BL8) were placed in the selectivity filter of the closed and open models. Since solvation parameters for K+ are not specified in the method of Lazaridis and Karplus (1999), K+ hydration was treated using solvation parameters of  group. This assumption does not affect major results since K+ ions are practically in the same positions in the closed and open conformations of the channel (see Results).

group. This assumption does not affect major results since K+ ions are practically in the same positions in the closed and open conformations of the channel (see Results).

The all-atom model of KcsA in the closed state was built using the x-ray structure of Doyle et al. (1998) as the starting point. The model of KcsA in the open state was built using the x-ray structure of MthK (Jiang et al., 2002a) as a template. All-trans starting conformations were assigned for those side chains that are not resolved in the crystallographic structure of KcsA. Residues that are different between KcsA and MthK were also assigned all-trans starting conformations during MC-minimization (MCM) of the open KcsA model. The inner helices of MthK are shorter than in KcsA at their C-ends, whereas the outer helices of MthK are shorter at their N-ends. Corresponding residues of KcsA were assigned α-helical conformations in both open and closed states. The α-helical structure of these residues was imposed by H-bonding constraints.

The optimal conformations of KcsA in the closed, open, and intermediate states were searched by the Monte Carlo-minimization protocol (Li and Scheraga, 1987). Energy was minimized in the space of generalized coordinates using the ZMM program (Zhorov, 1981). MC-minimizations of the open and closed models were terminated when the last 10,000 energy minimizations did not improve the energy. The criterion of convergence of MC-minimizations of intermediate states in the channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories was 2000 minimizations without improving the energy. Other details of the MCM implementation in the ZMM program are described elsewhere (Zhorov and Ananthanarayanan, 1996; Zhorov and Lin, 2000).

The open and closed models of KcsA were initially MC-minimized with a flat-bottom penalty function (Brooks et al., 1985) that allows penalty-free deviation of α-carbons up to 1 Å from the crystallographic coordinates and impose an energy penalty for larger deviations. During the MCM search, all torsions were randomized. After the constrained MCM trajectories converged, the constraints were removed, and the models of the open and closed KcsA were refined by the unconstrained MCM search. At this stage, only side-chain torsions were randomized, but all torsions were varied in subsequent energy minimizations.

The simulation of large-scale conformational transitions such as channel activation is not a trivial task. To impose lateral forces, we defined a cylinder at the pore axis. If the C-termini of the inner helices (more precisely, atoms Cα_Val115) occurred within the cylinder, a penalty function was added to the energy expression. In the channel-opening simulations, the penalty function Ec was as follows:

|

|

where f is the force constant of 100 kcal/mol−1/Å−2, d is the distance between the pore axis and Cα_Val115, and r is the radius of the cylinder. In the channel-closing trajectory, analogous penalty function was applied only when the C-termini of the inner helices occurred beyond the cylinder of radius r. The distance derivatives of Ec are the force vectors drawn normally to the pore axis and applied to atoms Cα_Val115. The cylinder of radius r may be considered as the imposed radius of the pore at the level of residues Val115 at the cytoplasmic part of the protein.

The starting structures for the channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories were MC-minimized models of corresponding x-ray structures. The trajectories were calculated by varying the imposed radius r between 5 and 22.1 Å with the step of 0.9 Å and MC-minimizing the energy at each step. The structure found at the given point of the trajectory was used as the starting point for the next trajectory.

RESULTS

MC-minimized models of KcsA in the open and closed states

Energy characteristics of MC-minimized models of KcsA in the closed and open state are shown in Table 1. Henceforth, these models are called KcsA-based and MthK-based models because they were obtained by using, respectively, x-ray structures of KcsA and MthK as templates (see Methods). The root mean-square deviation (RMSD) of α-carbons of KcsA- and MthK-based models from corresponding x-ray structures is less than 2 Å (Table 2). The maximal difference occurs at the cytoplasmic ends of the inner and outer helices, where MCM search yielded more regular helical structure than in templates. At these regions, maximal deviations of α-carbons from the x-ray templates were as large as 2.5 Å. Both open and closed states have low van der Waals energy (about −6 kcal/mol per residue) indicating that bad contacts that were unavoidable in the starting conformations were removed during MC-minimizations.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of MC-minimized models of KcsA in the open and closed states

| Closed state

|

Open state

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All protein | Per residue | All protein | Per residue | ΔE upon channel opening |

| Energy component (kcal/mol) | |||||

| Van der Waals | −2346.2 | −6.0 | −2276.3 | −5.9 | 69.9 |

| H-bonds* | −92.1 | −0.2 | −70.1 | −0.2 | 22.1 |

| Electrostatics†‡ | −129.2 | −0.3 | 85.2 | 0.2 | 214.4 |

| Solvation | −2139.5 | −5.5 | −2263.8 | −5.8 | −124.3 |

| Torsional | 442.6 | 1.1 | 423.6 | 1.1 | −19.0 |

| Total energy | −4256.8 | −11.0 | −4102.8 | −10.6 | 154.0 |

| H-bonds in regions 95–105 | 68 | NA | 46 | NA | −22 |

NA, not applicable.

Van der Waals component of H-bonding energy calculated using the 10–12 potential in the AMBER force field (Weiner et al., 1984).

Including electrostatic interactions between donors and acceptors of H-bonds.

The electrostatic energy excludes 1,3 interactions, which increases the energy by a conformation-independent value.

TABLE 2.

Deviations (Å) of models from reference structures

| RMSD of α-carbons

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference structure* | Model*† | All KcsA | Outer helices | P-loops | Inner helices | Deviation of Cα in Val115 |

| KcsA, x-ray | KcsA-based | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| MthK, x-ray | MthK-based | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| KcsA-based | MthK-based | 5.6 | 4.2 | 1.3 | 8.5 | 15.2 |

| KcsA-based | In silico closed | 3.2 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| MthK-based | In silico activated | 2.6 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| MthK-based | In silico activated in vacuum‡ | 3.0 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| MthK-based | In silico activated by forces at Gln119§ | 3.2 | 4.1 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| MthK-based | In silico activated short model¶ | 2.3 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 2.0 |

| MthK-based | In silico activated short Gly99Ala mutant¶ | 2.4 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| MthK-based | In silico activated, without P-loops | NA | 3.9 | NA | 2.7 | 2.3 |

| MthK-based | In silico activated, without outer helices | NA | NA | 1.1 | 3.4 | 4.2 |

NA, not applicable.

MthK-based and KcsA-based models are obtained by MC-minimization of respective x-ray structures.

Unless otherwise specified, models are computed in the implicit-water environment. All models of the in silico activated and in silico closed channels correspond to those points of the channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories, in which the RMSD minima were reached. Unless otherwise specified, the in silico activation and closure is induced by forces applied to Cα_Val115.

The large RMSD is due to the fact that the reference structure is calculated in water and model in vacuum

The RMSD was calculated over three subunits that reached MthK-like conformations (see text).

The models with the diminished cytoplasmic ends of the inner and outer helices. The small values of RMSD are due to the absence of cytoplasmic residues that provide the largest contribution to the RMSD of full-fledged models.

According to our calculations, the closed-state model is 154 kcal/mol more stable than the open-state model (Table 1). The obvious structural changes that occur upon the channel opening are kinks in the inner helices and loss of contacts at their intracellular crossover. The latter results in the increase of van der Waals energy by ∼70 kcal/mol. The loss of interhelical contacts makes some residues less strained that is manifested in a small decrease of torsional energy. Electrostatic energy increases by ∼214 kcal/mol upon channel opening, which is the largest change among the energy components. The brake of the helical H-bonds in the kink region contributes significantly to this difference of the electrostatic energy and also to the increase of van der Waals interactions between the donors and acceptors of H-bonds (Table 1). The hydration energy is significantly (∼124 kcal/mol) more preferable in the open channel, which allows better hydration of the hydrophilic intracellular ends of the inner and outer helices. In addition, H-bonds in the inner helices that break upon the channel opening release hydrophilic N–H and O=C groups for more preferable hydration of the kink regions. Our models do not include lipids and cytoplasmic parts of the channel that can contribute significantly to the energy of the closed and open states.

When comparing the open and closed models of KcsA, of special interests are H-bonds in the kink region of the inner helices (residues 95–105). The open model has 22 H-bonds less than the closed model (Table 1). All H-bonds lost in the open conformation are in the kink region of the inner helices. Analysis of the low-energy structures collected during the MC-minimization of the open channel shows that H-bonds Met96_C=O⋯H–N_Ile100 and Gly99_C=O⋯H–N_Phe103 are broken most frequently. However, different low-energy structures collected during MC-minimization of the open channel have different patterns of H-bonds involving residues 96–103. This is not surprising, since the kinked region in the open-channel conformation is much more flexible than the corresponding straight region in the closed-channel conformation.

Trajectories of KcsA opening and closing

Conformational transitions of KcsA in response to lateral forces were simulated by computing the channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories. At each step of the trajectory, the energy was MC-minimized, and the obtained structure was compared with a reference structure, which was the MthK-based model for the channel-opening trajectory and KcsA-based model for the channel-closing trajectory. The RMSD of α-carbons of the inner helices (residues 86–115) and deviation of Cα_Val115 at the C-end of the inner helix were used for comparison. These characteristics are convenient for monitoring the in silico activation and closing of the channel: in the beginning of each trajectory, the RMSD of α-carbons and deviation of C-ends reflect the difference between KcsA-based and MthK-based models (Table 2). The minimal-RMSD structure obtained in the trajectory was considered as the in silico obtained model of the destination state.

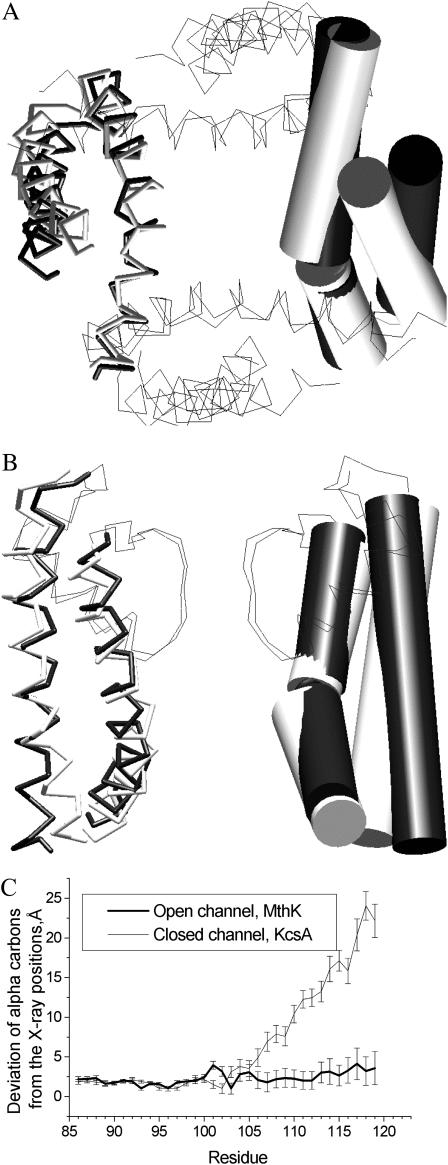

The channel-opening trajectory yielded the minimal-RMSD conformation, which is remarkably similar the x-ray structure of MthK (Fig. 2 and Table 2). And vice versa, the channel-closing trajectory that started from the open, MthK-like conformation of KcsA yielded the closed conformation in which positions of α-carbons are similar to those seen in the x-ray structure of KcsA.

FIGURE 2.

The in silico activated KcsA model versus MthK-based model. A and B are intracellular and side views of the superposition of the in silico activated KcsA (shaded) with the MthK-based model (solid). In the side view, only two nonadjacent subunits are shown, and in the top view P-loops are not shown. The inner and the outer helices are shown as cylinders in one subunit and as sticks in the opposite subunit. (C) Deviations of the inner helices' α-carbons in the in silico activated KcsA from the KcsA- and MthK-based models. The deviations are averaged over four subunits with the standard deviation shown as error bars. Note that the lateral forces do not affect N-parts of inner helices but induce a kink at the midpoint. The C-ends of the in silico activated KcsA approach positions seen in the MthK-based model.

In both channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories, the conformations of P-loops did not change noticeably. The lateral forces practically did not affect the extracellular part of the channel, in which the outer helices, the pore helices, and the inner helices are tightly packed. K+ ions inside the selectivity filter play an important role in stabilizing this region. In both the open and closed models, electrostatic interactions with K+ ions contribute about −140 kcal/mol to the protein energy. In each MC-minimized intermediate structure obtained in the channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories, K+ ions deviate less than 1 Å from their crystallographic positions. In all the models, the RMSD of P-loop α-carbons are small (Table 2) indicating that P-loops practically do not move in the channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories.

Conformations of the outer helices differ but not significantly between the x-ray structures of KcsA and MthK. In both open and closed conformations of KcsA, the outer helices are straight and do not include significant kinks or slopes. However, the comparison of x-ray structures shows that the N-ends of the outer helices in MthK are farther from the pore axis than in KcsA (Fig. 1). In the channel-opening trajectory, the N-ends of the outer helices did not reach positions seen in the open-channel model, but moved in the right direction: the RMSD of α-carbons in the outer helices decreased from 4.2 Å in the beginning of the trajectory to 3.6 Å in the lowest-RMSD structure (Table 2). In the channel-opening trajectory, the outer helices move due to the impact from the constraints-driven inner helices. In contrast, during the channel-closing trajectory, the outer helices practically did not move.

To enforce the large-scale conformational transitions, we applied the lateral forces to the C-ends of the inner helices. As a result, the largest changes were observed at the C-halves of these helices. The minimal values of RMSD and C-ends deviation for the channel-opening trajectory are 2.2 and 2.3 Å, respectively. The similarity of RMSD and C-end deviation means that the entire inner helix rather than only its C-end reached MthK-like position (Fig. 2 C). The optimal RMSD obtained in the trajectories is just 0.5–0.6 Å higher than the RMSD between the x-ray structures and corresponding x-ray based models. The obtained agreement between the computations and experiment is not surprising for the channel-closing trajectories, in which the inner helices converge to the tightly packed structure. The fact that the channel-opening trajectories, in which C-ends of the inner helices get unpacked, also converge to the experimentally observed structure indicates that lateral forces can induce conformation transition from a KcsA-like to a MthK-like structure.

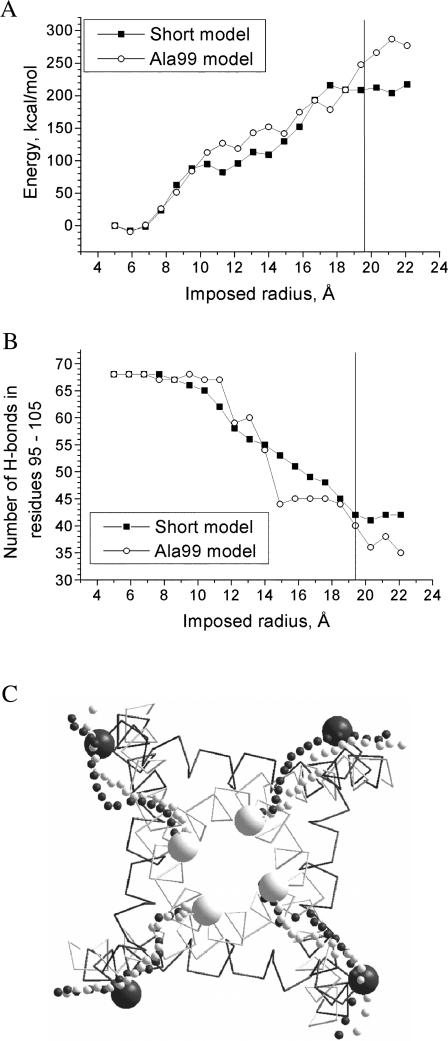

The channel-opening trajectory ended with a structure in which the inner helices are kinked and the number of H-bonds is essentially smaller than in the starting structure (Fig. 3 B). The pattern of the broken H-bonds varied among the low energy conformations found at each step of the trajectory. This clearly demonstrates that the kink region is flexible and can adopt various conformations. The channel-closing trajectory yielded the structure in which the kinks in the inner helices disappeared, but some helical H-bonds seen in the MC-minimized structure of the closed KcsA were not formed. A possible reason is that MCM search at each step of the trajectory was not long enough to find a structure with new H-bonds.

FIGURE 3.

The channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories. (A) Deviation of C-ends (Cα_Val115) from the reference structures. The values are averaged over four subunits with standard deviation shown as error bars. (B) The total number of H-bonds in residues 95–105 in all four subunits. (C) The MC-minimized energy profiles. The vertical line in charts A–C corresponds to the distance from the pore axis to Cα_Val115 in the MthK-based model. (D) C-ends in the channel-opening trajectory (white small spheres) and channel-closing trajectory (black small spheres). Big spheres represent C-ends in the KcsA- and MthK-based models. Both trajectories converge to the reference structure. A break at the opening trajectory (D) corresponds to the barrier in the energy profile (C).

As expected, the energy increased in the channel-opening trajectory and decreased in the channel-closing trajectory (Fig. 3 C). It should be emphasized again that the final structures were not biased in our simulation protocol. The agreement between the results of simulations and the x-ray structures is not trivial. It was not expected a priori, especially for the open channel. Molecular interactions during the channel-opening trajectory are analyzed in a later section.

It should be noted that no symmetry operators were used in our simulations. Each subunit interacted with neighboring subunits but moved independently. That is why the C-end tracings of individual subunits are different (Fig. 3 D). Despite the differences, the C-end in each subunit passes through the positions seen in the x-ray structures. The channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories are also not identical, showing hysteresis in the energy profile, C-end tracing, and H-bonding (Fig. 3). This indicates that multiple pathways exist between the open and closed conformations.

Numerous factors influence the process of the pathway search. In the channel-closing trajectory, the system moves downhill; among alternative pathways, the steepest-descent pathway is most likely to be found. For example, energy readily decreases at the initial stages of the channel-closing trajectory (Fig. 3 C). During the channel-opening trajectory, the system moves uphill; among alternative pathways, the most gently rising would be optimal. However, at the bifurcation points, the choice is determined by the local properties of the energy hypersurface rather than the entire pathway properties. Beyond the bifurcation point, the pathways may diverge significantly, but once the choice is made, there is no way back. This can explain the energy difference between trajectories at the imposed radii of 7–11 Å. Systematic exploring of possible pathways would require huge computational time.

In terms of the channel structure, the hysteresis can be explained by the fact that the cytoplasmic half of the protein is densely packed in the closed but not in the open conformation. In the channel-opening trajectory, the inner helices are driven away from the pore axis by lateral forces, but their move is opposed by the outer helices. To find their way out, the inner helices first shift the outer helixes to some extent and then kink against them. In the channel-closing trajectory, the behavior is simpler: it starts from the open structure and moves smoothly toward the energetically more preferable closed state.

Despite significant differences, both channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories have a significant energy barrier at the imposed radii r of 7–10 Å (Fig. 3 C). Atoms Cα_Val115 move smoothly at the beginning and the end of the trajectory, but not at the above-mentioned imposed radii (Fig. 3 D). The smooth C-end tracing between r = 5 and r = 7 Å suggests that the closed channel may have inherent fluctuations. The probable cause of the energy barrier is interactions at the intracellular crossing of the helices. As mentioned above, the closed state of the channel is stabilized by van der Waals contacts at this region, whereas C-ends are better hydrated in the open state.

Sensitivity of results to setup of the models

The channel-opening trajectory demonstrates that lateral forces induce transition of the KcsA-based structure to the MthK-like conformation. The transition is not a simple enlargement of the pore diameter at the level of the gate; it involves overcoming the energy barrier and the development of kinks at the middle part of the inner helices. The models were built with several assumptions, including hydration of entire protein and application of lateral force to Cα_Val115. To explore the dependence of our results on these assumptions, two additional channel-opening trajectories were calculated. In one trajectory protein hydration was ignored, and in another trajectory lateral forces were applied to Cα_Gln119 rather than Cα_Val115.

The channel-opening trajectory calculated in vacuum also yielded MthK-like geometry, in which the RMSD of α-carbons in the inner helices from MthK-based model was 2.4 Å, which is only 0.2 Å higher than in the hydrated model (Table 2). Two peculiarities of the in silico activated model without hydration have been observed. First, the energy difference between the closed and open conformations in vacuum is much larger than in water because hydration essentially stabilizes the open conformation. The second peculiarity is the number of H-bonds in the kink regions. The channel activation in vacuum retains many H-bonds, which break when the channel is activated in water. In the kink region (residues 95–105), only 11 H-bonds in the four domains break upon channel activation in vacuum. Obviously, water preferably solvates donors and acceptors of the broken helical H-bonds; the break of each H-bond in vacuum is expensive and the inner helices of the activated channel show a smooth bent rather than a localized kink.

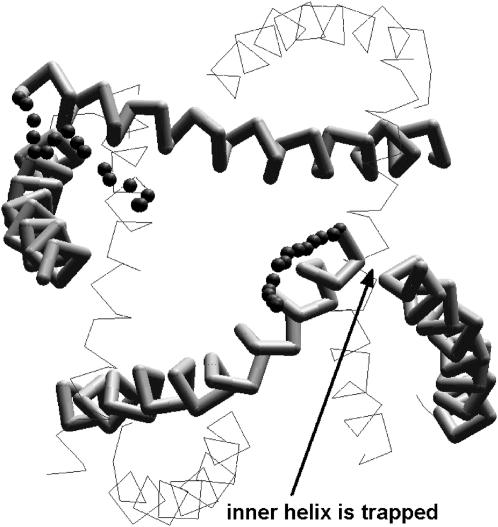

The application of lateral forces to atoms Cα_Gln119 yielded unexpected results. One of the four inner helices did not reach the MthK-like conformation (Fig. 4). The reason is that at the initial stages of the channel activation, the C-end of the inner helix established a strong contact with the neighboring outer helix. Since lateral force was applied to the very end of the C-terminus, it restricted its mobility. With the C-terminus of just one inner helix trapped in the KcsA-like conformation, the energy of the system increased dramatically because of nonsatisfied constraints. Interestingly, however, the three other subunits reached the MthK-like conformations with the RMSD of 2.4 Å. Thus, although the computational protocol setup obviously affect certain quantitative results of the in silico activation of KcsA, the general results and conclusions remain unchanged. In particular, all trajectories show the energy barrier between the open and closed states.

FIGURE 4.

The intracellular view of KcsA incompletely activated by lateral forces applied to Cα_Gln119. P-loops are not shown. For two opposite subunits, small spheres show the C-end trajectories. One of the subunits did not reach the open conformation, being trapped by interactions with the outer helix in the neighboring subunit; this pair is shown by sticks with the arrow indicating the trapping contact. In the opposite pair, which is also shown by sticks, the inner helix is not trapped and reaches the open-state conformation.

Short models of KcsA and Gly99Ala mutant

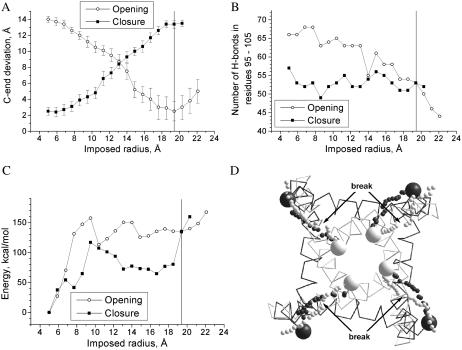

Analysis of trajectories suggests that interactions at the cytoplasmic helical ends may be partially responsible for the energy barrier in the channel-opening and channel-closing trajectories and the break in the C-end tracing (Fig. 3). To explore if there are other determinants of the barrier, we created a short model of KcsA, in which C-ends of the inner helices (residues 116–119) and N-ends of the outer helices (residues 23–28) were removed (see Fig. 1). The channel-opening trajectory of the short model, in general, has the same characteristics as the full-fledged model (Fig. 5 and Table 2). The RMSD of the inner helix α-carbons from the MthK-based model is 2.2 Å. However, the tracings of the C-ends of the inner helices (Fig. 5 C) become smoother than in the full-fledged model. Also, the short model does not show the energy barrier between the closed and open states (Fig. 5 A). This indicates that the energy barrier of the full-fledged model is indeed caused by interactions between the cytoplasmic parts of the helices at the early stages of channel opening.

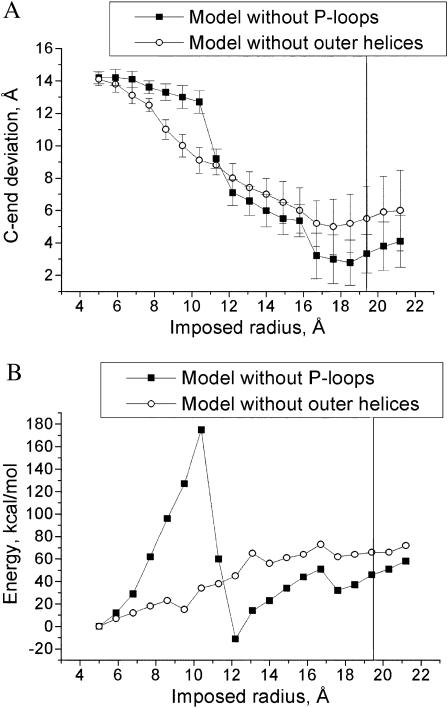

FIGURE 5.

Channel-opening trajectories of the short models of KcsA and Gly99Ala mutant. (A) MC-minimized energy profiles. Unlike the full-fledged model, the short models do not have an energy barrier between the open and closed states. (B) The total number of H-bonds in residues 95–105 in all four subunits. In the Gly99Ala mutant model, helical H-bonds break abruptly in the middle of the trajectory. The vertical line in charts A and B corresponds to the distance from the pore axis to Cα_Val115 in the MthK-based model. (C) Tracing of Cα_Val115 in the channel-opening trajectory of the short model of KcsA (black small spheres) and Gly99Ala mutant (white small spheres). Big spheres represent C-ends in the KcsA- and MthK-based models. Like in the full-fledged model, the channel-opening trajectories reach the MthK-based structure but without breaks in the trajectory.

Gly99 is conserved among K+ channels, but some other P-loop channels have larger residues in this position. To explore how the size of this residue affects the channel gating, we created a short model of the KcsA mutant Gly99Ala. The channel-opening trajectory of the mutant has characteristics very similar to those of the short model of the wild-type KcsA (Fig. 5). In the activated channel, the RMSD of the inner helix α-carbons from MthK-based model is 2.2 Å. The major differences are seen in the number of H-bonds (Fig. 5 B): in the mutant, this number decreases sharply at the imposed radii of 12–15 Å, whereas in the wide type KcsA the number of H-bonds changes smoothly. Obviously, the presence of Ala in position 99 reduces conformational flexibility of the neighboring regions, causing the whole α-helical turn to break abruptly. In contrast, in the wild-type KcsA, H-bonds in this α-helical turn break one at a time. The observed difference in the pattern of H-bonds breaking during channel opening supports important role of Gly99 in the gating of K+ channels (Jiang et al., 2002a,b). On the other hand, the channel-opening trajectories of the wild-type KcsA and Gly99Ala mutant are generally similar. This suggests that channels with larger residue in position 99 would undergo a conformational transition by a similar mechanism when activated by forces applied to the inner helices.

Models without P-loops and inner helices

As shown above, the channel-opening trajectory of the KcsA model with the short inner and outer helices arrived to the MthK-like conformation, despite having certain differences with the full-fledged model. Substitution of Gly99 by Ala also did not cause dramatic changes in the trajectory. To reveal key determinants of activation of the P-loop channels by the lateral forces applied to the C-ends of the inner helices, we sought further to explore the roles of the pore helices and the outer helices in the conformational transitions. With this goal, we created two additional models, one without the outer helices (residues 23–60) and another without the P-loops (residues 62–84). The channel-opening trajectories of the models were computed and analyzed (Fig. 6 and Table 2).

FIGURE 6.

Channel-opening trajectories of the models of KcsA without P-loops and without outer helices. (A) Deviation of C-ends from the MthK-based model. (B) MC-minimized energy profile. The vertical line corresponds to distance from the pore axis to Cα_Val115 in the MthK-based model. Although the model without outer helices moves toward MthK-based model, the agreement with the reference structure is the worst.

The forced activation of the model without P-loops yielded MthK-like structure, which was similar to that of the full-fledged model (see Table 2). As in the full-fledged model of KcsA, contacts at the intracellular crossing of the helices caused a large energy barrier in the middle of the trajectory (Fig. 6 B). Unexpectedly, the forced activation of the model without outer helices showed the same tendency of the C-ends-deviation profile as other models. The N-terminal parts of the inner helices remained stable due to contacts with the pore helices. The inner helices kinked at the midpoints, and their cytoplasmic parts approached positions seen in the MthK structure. In the absence of the outer helices, no energy barrier was observed. However, minimal deviation of the C-end (4.2 Å) and the RMSD for inner helices (3.4 Å) from the open model were significantly higher than in other models. Thus, interactions between the inner and outer helices have the largest effect on KcsA behavior in response to lateral forces. Our calculations show that the inner helices break against the outer helices. But even in the absence of the outer helices, the inner helices kink at the same region as in the larger models.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we applied the Monte Carlo-minimization protocol to simulate large-scale conformational transitions between the closed and open conformations of KcsA. The closed conformation of KcsA is available (Doyle et al., 1998), whereas the open conformation was modeled from the x-ray structure of MthK (Jiang et al., 2002a). The in silico transitions of KcsA between the closed and open conformations were driven only by the lateral forces applied to the C-ends of the inner helices. Importantly, no bias on the mutual disposition of the inner and outer helices in MthK has been imposed. The computational protocol yielded the final MthK-like structures in agreement with the experiment. Our results demonstrate that the structure of KcsA per se can determine the channel-activation pathway when lateral forces are applied to the C-ends of the inner helices.

It is necessary to emphasize obvious limitations of our modeling approach. We did not launch the challenging calculations of free energy. No lipids and no explicit waters have been included in the model. Entropy contribution to the free energy of different states has not been calculated. The simplified energy function allowed us to simulate a large-scale conformational transition of the channel structure in a reasonable computational time. The relative energies of the closed, open, and intermediate states probably reflect objective tendencies. However, the values of energy differences are overestimated. The large energy differences should be compensated by entropy (see Dunitz, 1995). Indeed, in the closed state, the side chains of residues at the cytoplasmic helical crossing are tightly packed and, thus, lose entropy. In the open state, these side chains are free to rotate and gain entropy.

Our modeling revealed possible inherent determinants of conformational transitions induced by lateral forces applied to the C-end of the inner helices. In particular, we demonstrated that the lateral forces do not destroy the tetrameric structure of the channel protein because intersegment and intersubunit contacts are strong enough. Thus, lateral forces do not change the extracellular half of the tetrameric channel but induce kinks of the inner helices. This agrees with the MD-based prediction of Shrivastava and Sansom (2000) that intracellular half of the protein at the helix bundle is less stable than the P-loop region. Our results can have simple mechanistic interpretation: the kinks occur where contacts of the inner helices with other segments vanish and the torque induced by the lateral forces is maximal within the potentially mobile region. In K+ channels, Gly99 further weakens this region. However, according to our model, this Gly is not the critical determinant of the activation mechanism.

Our results agree with the mutational study (Yifrach and MacKinnon, 2002) that revealed gating-sensitive residues near the intracellular crossover of the inner helices as well as at the extracellular half of the channel, where the inner helices contact the pore helices and several inner helix residues contact the adjacent outer helix. Similar data were obtained by Irizarry et al. (2002) who suggested that the cluster of residues at the extracellular half of the channel is responsible for the stability of the protein tetramer, whereas residues at the intracellular helix bundle affect channel gating.

It is interesting to compare results of our study with the earlier MD simulation of KcsA activation (Biggin and Sansom, 2002). Besides obvious differences in methods of sampling conformational space (MCM versus MD), the approaches to simulate the channel activation also differ essentially. Biggin and Sansom (2002) had placed a sphere at the gate region and progressively expanded it to induce channel opening in the environment of explicit water and lipid molecules. The resulting structures obtained by Biggin and Sansom show opening at the gate region, which is much smaller than in MthK. Importantly however, the general direction of the inner helices' movement is the same in both modeling studies. Both studies predict a change of the backbone geometry in the middle region of the inner helices. In general, characteristics of the channel-opening trajectories computed by Biggin and Sansom (2002) are very similar to the initial parts of trajectories computed in our study. In both cases, the inner helices start to move from the channel-closed conformation smoothly, without kinking and breaking H-bonds. When Biggin and Sansom (2002) ended the channel expansion, the channel had a tendency to relax back toward the closed conformation. This indicates that the channel was not expanded far enough to overcome the activation energy barrier and develop kinks in the inner helices. It should be noted that Biggin and Sansom (2002) simulated the channel opening before the MthK and KvAP structures were published. In this study, we took these structures into consideration to make the next step in the analysis of the channel activation problem.

Several crystallographic structures of bacterial K+ channels are now available. The closed-channel structures of KcsA and the inward rectifier K+ channel KirBac1.1 (Kuo et al., 2003) are similar. In contrast, the open-channel structures of the calcium-activated channel MthK and the voltage-gated channel KvAP (Jiang et al., 2003) are essentially different at the cytoplasmic part, despite both have a large open pore accessible for different ligands (see Zhorov and Tikhonov, 2004). In KvAP, the inner helices are also kinked in the middle part. However, unlike in MthK, the C-ends of the inner helices in KvAP shift both radially and tangentially as compared to KcsA. Furthermore, only in KvAP the outer helices have significant tangential slope. Our in silico experiments show that the radial forces applied to the C-ends of the inner helices induce conformational transition from a KcsA-like structure to a MthK-like but not to a KvAP-like structure. It seems that the energetically optimal closed state is conserved in different channels, whereas the open structures induced by different external activating forces are different.

For the members of greatly diverse P-loop channels, it is difficult to predict whether their open structure is MthK-like or KvAP-like. Furthermore, other open-channel structures (not resolved now) can also exist. In this regard, experimental studies that suggest moderate conformational rearrangements upon the channel activation (Perozo et al., 1998; Kelly and Gross, 2003) should be noted. Among 18 inner-helix residues of KcsA that are inaccessible at neutral pH, only Leu105 and Ala111 become accessible at low pH (Kelly and Gross, 2003).

K+ channels of the Shaker family have a PVP motif at the intracellular part of the inner helices that can destabilize the helical structure and induce a kink (Shrivastava et al., 2000). Experimental evidences for the PVP kink were provided (Holmgren et al., 1998; del Camino et al., 2000). The kinked inner helices could form different intersegment contacts that would affect channel activation.

Thus, important aspects of the activation of P-loop channels remain unclear. The crystallization of ion channels is still not a routine technique. Molecular modeling that deals with the stability of different structures and conformational transitions between these structures is helpful. This work demonstrates that such an approach is applicable for modeling the process of channel activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Iva Bruhova for reading the manuscript and valuable comments.

Computations were performed, in part, at the SHARCNET supercomputer center of McMaster University.

This work was supported by grants to B.S.Z. from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. B.S.Z. is a recipient of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Senior Scientist award.

Denis B. Tikhonov is on leave from Sechenov Institute of Evolutionary Physiology and Biochemistry, St. Petersburg, Russia.

References

- Armstrong, C. M. 1974. Ionic pores, gates, and gating currents. Q. Rev. Biophys. 7:179–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berneche, S., and B. Roux. 2002. The ionization state and the conformation of Glu-71 in the KcsA K(+) channel. Biophys. J. 82:772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggin, P. C., and M. S. Sansom. 2002. Open-state models of a potassium channel. Biophys. J. 83:1867–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, C. L., B. M. Pettitt, and M. Karplus. 1985. Structural and energetic effects of truncating long ranged interactions in ionic polar fluids. J. Chem. Phys. 83:5897–5908. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G. Q., C. Cui, M. L. Mayer, and E. Gouaux. 1999. Functional characterization of a potassium-selective prokaryotic glutamate receptor. Nature. 402:817–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Camino, D., M. Holmgren, Y. Liu, and G. Yellen. 2000. Blocker protection in the pore of a voltage-gated K+ channel and its structural implications. Nature. 403:321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, D. A., J. Morais Cabral, R. A. Pfuetzner, A. Kuo, J. M. Gulbis, S. L. Cohen, B. T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 1998. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 280:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunitz, J. D. 1995. Win some, lose some: enthalpy-entropy compensation in weak intermolecular interactions. Chem. Biol. 2:709–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullingsrud, J., and K. Schulten. 2003. Gating of MscL studied by steered molecular dynamics. Biophys. J. 85:2087–2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackos, D. H., T. H. Chang, and K. J. Swartz. 2002. Scanning the intracellular S6 activation gate in the Shaker K+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 119:521–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille, B. 2001. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- Holmgren, M., K. S. Shin, and G. Yellen. 1998. The activation gate of a voltage-gated K+ channel can be trapped in the open state by an intersubunit metal bridge. Neuron. 21:617–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry, S. N., E. Kutluay, G. Drews, S. J. Hart, and L. Heginbotham. 2002. Opening the KcsA K+ channel: tryptophan scanning and complementation analysis lead to mutants with altered gating. Biochemistry. 41:13653–13662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., A. Lee, J. Chen, M. Cadene, B. T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 2002a. The open pore conformation of potassium channels. Nature. 417:523–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., A. Lee, J. Chen, M. Cadene, B. T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 2002b. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 417:515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., A. Lee, J. Chen, V. Ruta, M. Cadene, B. T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 2003. X-ray structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature. 423:33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K. S., H. M. VanDongen, and A. M. VanDongen. 2002. The NMDA receptor M3 segment is a conserved transduction element coupling ligand binding to channel opening. J. Neurosci. 22:2044–2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi, K., T. Masuko, C. D. Nguyen, T. Kuno, I. Tanaka, K. Igarashi, and K. Williams. 2002. Channel blockers acting at N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors: differential effects of mutations in the vestibule and ion channel pore. Mol. Pharmacol. 61:533–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, B. L., and A. Gross. 2003. Potassium channel gating observed with site-directed mass tagging. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:280–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohda, K., Y. Wang, and M. Yuzaki. 2000. Mutation of a glutamate receptor motif reveals its role in gating and delta2 receptor channel properties. Nat. Neurosci. 3:315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, A., J. M. Gulbis, J. F. Antcliff, T. Rahman, E. D. Lowe, J. Zimmer, J. Cuthbertson, F. M. Ashcroft, T. Ezaki, and D. A. Doyle. 2003. Crystal structure of the potassium channel KirBac1.1 in the closed state. Science. 300:1922–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis, T., and M. Karplus. 1999. Effective energy function for proteins in solution. Proteins. 35:133–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z., and H. A. Scheraga. 1987. Monte Carlo-minimization approach to the multiple-minima problem in protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:6611–6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., M. Holmgren, M. E. Jurman, and G. Yellen. 1997. Gated access to the pore of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Neuron. 19:175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z., A. M. Klem, and Y. Ramu. 2002. Coupling between voltage sensors and activation gate in voltage-gated K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:663–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzhkov, V. B., and J. Aqvist. 2000. A computational study of ion binding and protonation states in the KcsA potassium channel. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1481:360–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momany, F. A., R. F. McGuire, A. W. Burgess, and H. A. Scheraga. 1975. Energy parameters in polypeptides. VII. Geometric parameters, partial atomic charges, nonbonded interactions, hydrogen bond interactions, and intrinsic torsional potentials of the naturally occurring amino acids. J. Phys. Chem. 79:2361–2381. [Google Scholar]

- Perozo, E., D. M. Cortes, and L. G. Cuello. 1998. Three-dimensional architecture and gating mechanism of a K+ channel studied by EPR spectroscopy. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5:459–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranatunga, K. M., I. H. Shrivastava, G. R. Smith, and M. S. Sansom. 2001. Side-chain ionization states in a potassium channel. Biophys. J. 80:1210–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadja, R., K. Smadja, N. Alagem, and E. Reuveny. 2001. Coupling Gbetagamma-dependent activation to channel opening via pore elements in inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Neuron. 29:669–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, I. H., C. E. Capener, L. R. Forrest, and M. S. Sansom. 2000. Structure and dynamics of K channel pore-lining helices: a comparative simulation study. Biophys. J. 78:79–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, I. H., and M. S. Sansom. 2000. Simulations of ion permeation through a potassium channel: molecular dynamics of KcsA in a phospholipid bilayer. Biophys. J. 78:557–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhareva, M., D. H. Hackos, and K. J. Swartz. 2003. Constitutive activation of the Shaker Kv channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 122:541–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, S. J., P. A. Kollman, D. A. Case, U. C. Singh, C. Chio, G. Alagona, S. Profeta, and P. K. Weiner. 1984. A new force field for molecular mechanical simulation of nucleic acids and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106:765–784. [Google Scholar]

- Yarov-Yarovoy, V., J. C. McPhee, D. Idsvoog, C. Pate, T. Scheuer, and W. A. Catterall. 2002. Role of amino acid residues in transmembrane segments IS6 and IIS6 of the Na+ channel alpha subunit in voltage-dependent gating and drug block. J. Biol. Chem. 277:35393–35401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi, B. A., Y. F. Lin, Y. N. Jan, and L. Y. Jan. 2001. Yeast screen for constitutively active mutant G protein-activated potassium channels. Neuron. 29:657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yifrach, O., and R. MacKinnon. 2002. Energetics of pore opening in a voltage-gated K+ channel. Cell. 111:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhorov, B. S. 1981. Vector method for calculating derivatives of energy of atom-atom interactions of complex molecules according to generalized coordinates. J. Struct. Chem. 22:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhorov, B. S., and V. S. Ananthanarayanan. 1996. Structural model of a synthetic Ca2+ channel with bound Ca2+ ions and dihydropyridine ligand. Biophys. J. 70:22–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhorov, B. S., and S.-X. Lin. 2000. Monte Carlo-minimized energy profile of estradiol in the ligand-binding tunnel of 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: atomic mechanisms of steroid recognition. Proteins. 38:414–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhorov, B. S., and D. B. Tikhonov. 2004. Potassium, sodium, calcium, and glutamate-gated channels: pore architecture and ligand action. J. Neurochem. 88:782–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]