Abstract

Aqueous humor drains from the eye through Schlemm's canal, a small endothelial-lined collecting duct. Schlemm's canal endothelial cells may be important in controlling the pressure within the eye (and hence are of interest in glaucoma), and are subject to an unusual combination of shear stress and a basal-to-apical pressure gradient. We sought to characterize this biomechanical environment and determine its effects on F-actin architecture in situ. A theoretical model of flow in Schlemm's canal was used to estimate shear stresses applied to endothelial cells by flowing aqueous humor. Alignment of Schlemm's canal endothelial cells in human eyes was quantified by scanning electron microscopy. F-actin architecture was visualized by fluorescent labeling and compared for closely adjacent cells exposed to different biomechanical environments. We found that, despite the relatively low flow rate of aqueous humor, shear stresses experienced by Schlemm's canal endothelial cells could reach those in the arterial system. Schlemm's canal endothelial cells showed a statistically significant preferential alignment, consistent with a shear-mediated effect. Schlemm's canal endothelial cells subjected to a basal-to-apical pressure gradient due to transendothelial flow showed a prominent marginal band of F-actin with relatively few cytoplasmic filaments. Adjacent cells not subject to this gradient showed little marginal F-actin, with a denser cytoplasmic random network. We conclude that Schlemm's canal endothelial cells experience physiologically significant levels of shear stress, promoting cell alignment. We speculate that this may help control the calibre of Schlemm's canal. F-actin distribution depends critically on the presence or absence of transendothelial flow and its associated pressure gradient. In the case of this pressure gradient, mechanical reinforcement around the cell periphery by F-actin seems to be critical.

INTRODUCTION

Aqueous humor is a clear, colorless fluid produced in the eye. It flows within the anterior portion of the eye, nourishing avascular tissues and pressurizing the eye, before draining out of the eye. Schlemm's canal is a small collecting duct, into which most of the aqueous humor drains in human eyes. Schlemm's canal lined by a monolayer of vascular-derived (Krohn, 1999; Hamanaka et al., 1992) endothelial cells, and the biomechanics of these cells are of interest for two reasons. First, due to aqueous humor flow, these cells are exposed to highly spatially nonuniform forces in vivo. It is therefore possible to study the effects of different biomechanical environments on endothelial cells in whole tissue, as opposed to in cell culture. Second, Schlemm's canal endothelial (SCE) cells may be important in the common ocular disease glaucoma. We consider these two points further.

SCE cells reside in a biomechanical environment suitable for evaluating cellular response to forces in situ

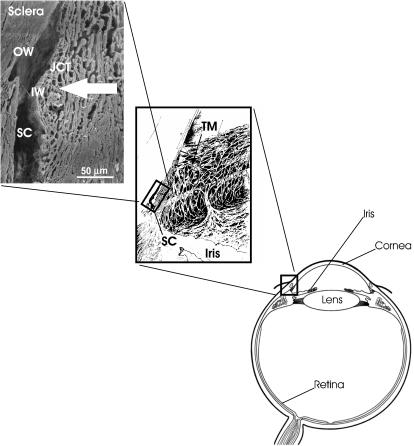

The endothelial monolayer lining Schlemm's canal can be conveniently subdivided into “inner” and “outer” walls (see Fig. 1 for terminology and identification of major features). Due to the directionality of aqueous humor flow into Schlemm's canal, inner wall cells are distended by a basal-to-apical pressure gradient, whereas outer wall cells are forced against their basal lamina and do not experience this distension. Inner and outer wall cells therefore represent two subpopulations of vascular-derived endothelial cells, situated only a few microns apart, that experience an inherently asymmetric biomechanical environment in vivo. We wish to determine how this translates into phenotypical differences, e.g., in cytoskeletal architecture.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of ocular anatomy, showing position of Schlemm's canal within the outflow tissues of the human eye. Aqueous humor drains from the eye by passing through the porous connective tissue known as the trabecular meshwork (including the juxtacanalicular tissue), before entering Schlemm's canal. Aqueous humor crosses the inner wall endothelial cells producing a basal-to-apical pressure gradient, whereas outer wall cells reside on the relatively impermeable sclera and experience a pressure gradient in the opposite (apical-to-basal) direction. Herniations of the inner wall cells (giant vacuoles) are just visible at the cut edge of the canal. Not shown in this figure are collector channels, which emanate from Schlemm's canal and carry the aqueous humor to mix with blood in the scleral venous circulation. TM, trabecular meshwork; JCT, juxtacanalicular tissue; SC, Schlemm's canal; IW, inner wall; OW, outer wall; large arrow, direction of aqueous humor flow. Middle panel modified from Hogan et al. (1971); top panel is a scanning electron micrograph of a human sample cut in cross section.

It is interesting that SCE cells on opposite sides of the canal are sometimes observed to be very well aligned with one another. It is unclear if this alignment is more than random, and if so, what the mechanism of alignment is. Shear stress exerted by flowing aqueous humor within Schlemm's canal is a natural candidate for aligning SCE cells, but because the aqueous flow rate is only 2–2.5 μl/min, it is unclear whether sufficient shear stresses are present in vivo.

SCE cells may be important in glaucoma

Glaucoma is the second most common cause of blindness in Western countries, afflicting 65–70 million people worldwide (Quigley, 1996). In most cases of glaucoma, the intraocular pressure (IOP) is elevated, due to impaired drainage of aqueous humor from the eye. All current medical therapy for glaucoma is designed to lower IOP. Unfortunately, existing pressure-lowering treatments frequently fail and there is therefore a great deal of interest in determining the factors that control IOP (Johnson and Erickson, 2000). SCE cells probably play a role in determining IOP (Ethier, 2002), and despite being the subject of much study, definitive evidence of how SCE cells might influence IOP remains lacking.

Although the mechanisms by which IOP is controlled in the eye are not known, the cytoskeleton of cells within the outflow tissue plays a key role in influencing aqueous outflow resistance (Tian et al., 2000). In particular, alteration of F-actin architecture and/or actin-myosin tone has a large effect on aqueous outflow resistance, as recently demonstrated in perfusion studies using latrunculin-A and -B, and H-7 (Peterson et al., 1999, 2000a,b; Sabanay et al., 2000; Tian et al., 1998) and transfection of perfused anterior segments with dominant negative RhoA (Vittitow et al., 2002). These studies, in conjunction with observations of a substantial F-actin presence in outflow pathway cells in situ (Gipson and Anderson, 1979; de Kater et al., 1992; Flügel et al., 2002), and the ability of the contractile state of outflow tissues to influence aqueous outflow resistance (Wiederholt et al., 2000), motivate further study of actin architecture within the aqueous outflow system.

Our purpose in this study was to characterize the biomechanical environment of Schlemm's canal endothelial cells, and to observe how this environment influences F-actin architecture within these cells. Because only humans and upper primates have a true Schlemm's canal, we have confined attention to human tissue.

METHODS

Paired, ostensibly normal human eyes were obtained post mortem from the Eye Bank of Canada (Ontario division, Toronto, Ontario) and NDRI (Philadelphia, PA). Eyes were free of any known ocular disease, and were stored in moistened chambers at 4°C until use. In some pairs of eyes (Table 1), outflow facility (inverse of flow resistance) was measured by perfusion with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) with added 5.5 mM glucose at either 2 or 30 mmHg mmHg, using standard methods (Ethier et al., 1993). Eyes were then fixed by anterior chamber exchange at IOP of 2, 8, or 30 mmHg. For eyes to be examined by scanning electron microscopy (three eyes), the fixative was universal fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M Sörensen's buffer, pH 7.3). For eyes to be examined by confocal microscopy, the fixative was 3% paraformaldehyde in DPBS.

TABLE 1.

Summary of characteristics of eyes and experimental conditions used in this study

| ID no. | Age/sex | Time to perfuse (h) | Outflow facility* (μl/min/mmHg) | Fixation pressure (mmHg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eyes processed for fluorescence microscopy | ||||

| 7118 | 88/F | 18.0 | ND | 30 |

| 7119 | ND | 2 | ||

| 7285 | 84/M | 19.6 | ND | 2 |

| 330OD | 77/M | 26.4 | ND | 30 |

| 330OS | ND | 2 | ||

| 279OD | 71/F | 33.0 | ND | 30 |

| 279OS | ND | 2 | ||

| 492 | 87/F | 21.2 | ND | 30 |

| 493 | ND | 2 | ||

| 072 | 79/M | 20.2 | 0.20 | 30 |

| 073 | 0.18 | 2 | ||

| 510 | 68/M | 23.0 | 0.20 | 2 |

| 9908 | 81/F | 28.0 | 0.10 | 2 |

| Eyes processed for scanning electron microscopy | ||||

| 791 | 70/M | 40.0 | ND | 30 |

| 497 | 78/F | 17.3 | 0.25 | 8 mmHg |

| 624 | 73/M | 15.5 | 0.24 | 8 mmHg |

ND, facility not determined.

Radial segments of the limbal area were microdissected using a modification of previously described techniques (Ethier et al., 1998; Ethier and Coloma, 1999; Ethier and Chan, 2001). Specifically, an incision was made along the posterior margin of Schlemm's canal while leaving the anterior margin of the canal untouched, and the trabecular meshwork and adherent inner wall of Schlemm's canal were carefully folded anteriorly. This procedure opened Schlemm's canal like a book (with the book spine corresponding to the anterior margin of the canal) and allowed simultaneous visualization of both the inner and outer walls of Schlemm's canal (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of inner wall (IW) and outer wall (OW) of Schlemm's canal. The anterior tip of the canal is indicated by the black line. Localized damage around this anterior tip is evident, but the remainder of the tissue is well preserved. A collector channel ostium (CC) can be seen on the outer wall. The inset shows a higher magnification of inner wall, identifying giant vacuoles (arrows) and transendothelial pores (arrowheads). Overview image from Eye 791.

Morphometric analysis of cell alignment

We measured the relative alignment of cells on opposite sides of Schlemm's canal, reasoning that if opposing cells tended to align with one another this would suggest a role for shear stress. It should be emphasized that we did not measure the alignment of cells with respect to collector channel ostia. This is because cells do not invariably align toward collector channel ostia (although they often do), presumably due to local variations in canal geometry affecting flow. Therefore, inner-outer wall relative alignment was thought to be a more robust measure of possible effects of shear stress on cellular orientation.

After microdissection, the inner and outer walls of Schlemm's canal were prepared for scanning electron microscopy using standard methods (Ethier et al., 1998). A photomontage of the inner wall (magnification = 1000×) was taken, ensuring that the microscope stage was oriented so that the inner wall was approximately normal to the incident electron beam. The stage was then adjusted to orient the outer wall normal to the beam, and a similar photomontage of the outer wall was taken (Fig. 3, top left).

FIGURE 3.

Inner and outer wall cells in Schlemm's canal tend to align with one another. The upper left panel shows two corresponding SEM montages (IW, inner wall; OW, outer wall). The top right panel shows the corresponding cell alignments, with inner and outer wall cell orientations shown in red and green, respectively (CC, collector channel ostium; D, damaged region; Edge, edge of canal). The bottom panel shows a summary of alignment data for all montages in all eyes. The horizontal axis is the angle between opposing cells of the inner and outer wall. The vertical axis is the percentage of inner wall area having the indicated degree of alignment between inner and outer wall cells. Solid bars are for analysis of the entire montage; open bars only for cells within 150 μm of a collector channel ostium.

To quantify the relative alignment between inner and outer wall endothelial cells, curves parallel to the margins of the cells were traced onto clear acetate sheets placed on top of the montages (Fig. 3, top right). For each tissue sample, landmarks on the inner and outer wall (e.g., cut edges, sites of damage where inner and outer wall were adhering to each other, cut septa spanning across the canal) were identified and used to align the acetate sheets corresponding to the inner and outer walls. The relative angle between opposing cells was then measured with a protractor and classified into one of six 15° ranges, i.e., 0–15° (Range1), 15–30° (Range2), … 75–90° (Range6). The outer wall was then subdivided into “patches” having the same value of Rangei (i = 1…6). The area of each patch and the distance of its centroid to the nearest collector channel ostium centroid were then measured using a digitizing tablet.

The measured distribution of relative cellular orientations was tested using the χ2-goodness of fit test, with the null hypothesis being that relative angles were equiprobable, i.e., that the total areas of Rangei (i = 1…6) were the same (Choi, 1978). To use the χ2-test, the measured areas were converted to frequency counts by dividing the area in Rangei by the average area of an inner wall endothelial cell (408 μm2; Lutjen-Drecoll and Rohen, 1970). This procedure was repeated for three widely separated montages from each of three eyes. The total overlapping area measured was ∼418,000 μm2, corresponding to ∼1020 cells.

Visualization of F-Actin architecture

For confocal microscopy Schlemm's canal was opened as described above, the inner and outer wall were separated by means of a sharp downward incision at the “spine” and tissue samples were triple labeled to visualize F-actin, nuclei, and either laminin (as a basement membrane marker) or CD31 (as an endothelial cell membrane marker). Tissue was permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in DPBS for 5 min at room temperature, washed in DPBS, then blocked with a preincubation solution of DPBS containing 1% goat serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 45 min at 37°C. To visualize laminin, tissue segments were labeled with rabbit anti-laminin IgG (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). The samples were incubated in the primary antibody diluted 1:100 in DPBS overnight at room temperature, followed by a DPBS wash and incubation in the fluorescent secondary antibody (Cy5-goat anti-rabbit IgG; Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) diluted 1:100 in DPBS for 75 min at 37°C. To visualize cytoplasmic membranes of SCE cells, tissue was labeled with mouse anti-CD31 IgG (DAKO), diluted 1:30 in DPBS, and incubated overnight at room temperature. After a DPBS wash, the radial segments were then incubated in Cy5-goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch), diluted 1:100 for 75 min at 37°C.

All samples were then washed with DBPS, and F-actin was labeled by incubation in 330 nM rhodamine-phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in DPBS for 30 min at 37°C. Nuclei were labeled by incubating in 2 μM Sytox (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in Tris-buffered saline for 5 min at room temperature.

After a thorough DPBS wash, a thin slice of tissue comprising the SCE, juxtacanalicular tissue, and TM was divided from the ciliary body and root of the iris by means of a oblique incision starting at the posterior margin of Schlemm's canal. This thin tissue sample was then mounted on a slide possessing a shallow chamber constructed from a single sheet of Parafilm “M” (American National Can, Neenah, WI). This arrangement prevented compression of the tissue during coverslipping. The much thicker outer wall segments were mounted in 0.6–0.8 mm deep depression slides (Canadawide Scientific, Ottawa, Canada). After application of DAKO fluorescent mounting medium, the tissue was covered using a No. 0 coverslip. For both inner and outer wall samples, the tissue was oriented so that the endothelium of Schlemm's canal was closest to the coverslip.

Confocal microscopy

The inner and outer walls of Schlemm's canal were examined using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany), equipped with argon-krypton, helium-neon and neon lasers, and three true confocal channels, permitting simultaneous visualization and collection of three different fluorophores in separate and distinct confocal channels. The absorption/emission spectra of the fluorophores were 504/523 nm for Sytox, 554/573 nm for rhodamine-phalloidin, and 650/670 nm for the Cy5 conjugate. Each inner/outer wall preparation was ∼2-mm long (in the circumferential direction). The average number of preparations examined was 6.1 per eye (range 3–10).

Optical sections were collected using a ×63 or ×100 oil objective lens as a “Z-series.” To acquire a Z-series, the focal plane was adjusted so that it lay above the tissue, in which case no signal was present. The focal plane was then advanced toward the tissue until a small amount of fluorescent signal was present, usually from nuclei. This position was assumed to correspond to the apical aspect of Schlemm's canal endothelial (SCE) cells, and was the first image acquired within the Z-series. The focal plane was then advanced “deeper” into the tissue to collect the remainder of the Z-series. Z-step intervals were 0.5–1.0 μm and individual optical sections were 0.6–1.0-μm thick. To optimize the pinhole size (i.e., to give an Airy disk unit setting of between 0.74 and 1.0) and gain, the automatic brightness and contrast function were used with a 1.9-s signal averaged scan. To compensate for bleaching as the Z-series collection progressed, the gain and laser power were adjusted as necessary. Z-series were viewed in Zeiss Image Browser, version 5 (Carl Zeiss).

A model of flow in Schlemm's canal

To estimate the shear stress acting on endothelial cells within Schlemm's canal due to aqueous humor flow within Schlemm's canal, we approximated Schlemm's canal as elliptical in cross section with major and minor axes a and b, respectively (see inset of Fig. 4). The flow rate within the canal, and hence the shear stress acting on inner wall cells, depend on the proximity to a collector channel. After Johnson and Kamm (1983), we account for this effect by treating Schlemm's canal as a duct of uniform cross section with a porous wall (the trabecular meshwork) through which aqueous humor seeps. Denoting axial position in this duct by x, conservation of mass implies that

|

(1) |

where Q(x) is the flow rate in Schlemm's canal, p(x) is the local pressure in Schlemm's canal, IOP is intraocular pressure (assumed constant), and 1/Riw is the hydraulic conductivity of the trabecular meshwork and inner wall, per unit length of inner wall, assumed to be constant. For convenience we take x = 0 as the midway point between two collector channels, and x = ±L as the locations of the nearest collector channel ostia (see inset of Fig. 2).

FIGURE 4.

Endothelial cells lining Schlemm's canal are exposed to physiologically significant levels of shear stress due to flowing aqueous humor. The vertical axis is the circumferentially averaged shear stress computed from a simple model in which Schlemm's canal is modeled as being elliptical in cross section. The horizontal axis is the height of the canal (ellipse minor axis length). The panels at the top of the graph show the assumed cross-sectional shape of the canal and the terminology for computing the flow rate as a function of position in the canal, Q(x). TM, trabecular meshwork; SC, Schlemm's canal; CC, collector channel.

In the case of creeping flow, the axial pressure gradient is balanced by the shear stress on the duct walls

|

(2) |

where  is the circumferentially averaged shear stress, A is Schlemm's canal cross-sectional area, and C is the perimeter of the canal cross section. The velocity profile for steady, fully developed laminar flow in a duct of elliptical cross section with semiminor and semimajor axes a and b, respectively, is Shah and London (1978)

is the circumferentially averaged shear stress, A is Schlemm's canal cross-sectional area, and C is the perimeter of the canal cross section. The velocity profile for steady, fully developed laminar flow in a duct of elliptical cross section with semiminor and semimajor axes a and b, respectively, is Shah and London (1978)

|

(3) |

where y and z are position coordinates (−b ≤ y ≤ b; −a ≤ z ≤ a). The wall shear stress,  varies with circumferential position; the mean value is

varies with circumferential position; the mean value is

|

(4) |

where E is the complete elliptic integral of the second kind. The minimum and maximum wall shear stresses are given by

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

The local flow rate, Q(x), is computed by combining Eqs. 1, 2, and 4 and applying the boundary conditions Q(x) = 0 at x = 0 and Q(x) = Qtot/2N at x = ±L, where Qtot is the total flow rate entering the canal (2.4 μl/min) and N is the number of collector channels (30) (Johnson and Kamm, 1983; Moses, 1979). The resulting solution is

|

(7) |

The following parameter values were used for calculations: viscosity of aqueous humor μ = 0.75 cP (Moses, 1979); distance between collector channels 2L = 1.2 mm (Johnson and Kamm, 1983); anterior-posterior dimension of Schlemm's canal 2a = 264 μm (Allingham et al., 1996); total aqueous humor flow rate Qtot = 2.4 μl/min (Moses, 1979); number of collector channels N = 30 (Johnson and Kamm, 1983; Moses, 1979); and resistance of trabecular meshwork + inner wall per unit length Riw = 2.67 mmHg/μl/min, corresponding to 80% of the total pressure drop across the outflow system occurring across the trabecular meshwork and inner wall (Johnson and Erickson, 2000). The inner-outer wall separation of Schlemm's canal, 2b, was allowed to vary between 1 and 30 μm.

RESULTS

Cell alignment

Of the nine montages analyzed, six showed evidence of alignment between inner and outer wall Schlemm's canal endothelial cells. When the data were pooled for all montages, there was a clear trend toward more aligned cells than nonaligned cells (Fig. 3). The observed distribution was statistically different than the uniform one expected for random cell orientation (p < 10−6; χ2-goodness of fit test). We also looked at cells located only within the neighborhood of a collector channel ostium (where presumably the flow and hence wall shear stress is highest). We defined neighborhoods to be cells lying within a specified cut-off radius from the nearest collector channel ostium, and considered cut-off radii from 50 to 300 μm. The same trend was clear for all cut-off radii and was consistent or slightly stronger than the trend seen when considering the entire montage area. For example, Fig. 3 shows the distribution for a radius of 150 μm, for which the p-value was also <10−6. These data are consistent with shear stress-mediated alignment of SCE cells.

Computed wall shear stresses in Schlemm's canal

Flow is maximum near the collector channel ostium, and it is therefore useful to first estimate how flow rate in the canal varies with x. Plugging numerical values into the expression for k given in Eq. 7 shows that the product kL is small for most canal heights, b, except for the most collapsed configuration. This implies that the flow rate increases approximately linearly with position x, so that flow can be approximated by

|

(8) |

In this case, all shear stresses scale linearly with distance away from the collector channel ostium. The exception to this rule is when Schemm's canal becomes nearly collapsed, in which case flow is a slightly nonlinear function of x. For example, when the canal height is everywhere 3 μm, the actual flow deviates from the value predicted by Eq. 8 by ∼6% at x/L = 1/2; when the canal height is everywhere 2 μm the deviation is ∼15%.

Shear stresses acting on SCE cells due to aqueous humor flow in Schlemm's canal were predicted to depend strongly on canal height. For canal heights in the range of ∼2.5–8 μm in the vicinity of the collector channel ostium (x = 0), the model predicted circumferentially averaged shear stresses in the range commonly seen in large arteries, i.e., 2–25 dynes/cm2 (top curve, Fig. 4). The maximum shear stress was usually ∼25% higher than the circumferentially averaged value. When the canal widened to >∼12 μm, the circumferentially averaged shear stress near the collector channel ostium fell below 1 dyne/cm2. Away from the collector channel the shear stress is lower; at x/L = 1/2 it is 35–50% of the value at the collector channel ostium, depending on the height of Schlemm's canal (bottom curve, Fig. 4).

Histologic findings

The morphology of the combined inner-outer wall preparation appeared normal, with bulging cells on the inner wall (representing giant vacuoles and/or nuclei) and inner wall pores present (Fig. 3). Giant vacuoles are pressure-dependent distensions of the SCE inner wall cells (Grierson and Lee, 1975), whereas pores are believed to be the pathway by which aqueous humor crosses the SCE cells (Bill and Svedbergh, 1972). There was some localized damage to the inner and outer walls near the anterior end of the canal, as well as in isolated regions of the inner and outer walls (Fig. 3). Such damaged regions are also present in conventional preparations of the inner wall only, and likely occur during the microdissection step. Overall morphology was judged to be well preserved by this dissection protocol, and was comparable to that observed in previous preparations where only the inner wall and underlying trabecular meshwork were harvested (Ethier et al., 1998; Ethier and Coloma, 1999; Ethier and Chan, 2001).

Because cells in whole tissue do not lie on a flat substrate (especially on the undulating inner wall of Schlemm's canal), it was often difficult to know where the optical section plane lay within the tissue being imaged. To overcome this problem while maintaining the tissue in its native configuration, it was essential to use landmarks within the tissue. Several authors (Marshall et al., 1990; Hann et al., 2001; Brilakis et al., 2001) have reported that laminin is present within the basal lamina of SCE cells (as well as within tendinous sheath material within the underlying juxtacanalicular tissue). We therefore used the laminin labeling to determine whether our Z-plane was “above” the basal lamina of SCE cells. Specifically, we considered the “topmost” Z-section with significant laminin labeling (at a given (x,y) location) to be the Z-section closest to the basal lamina at that (x,y) location. A negative control for laminin labeling is shown in Fig. 5. It can be seen that there is some faint, punctate nonspecific labeling, but that the overall level of nonspecific labeling is quite low.

FIGURE 5.

Negative control for laminin staining (left panel) and CD31 staining (right panel). Controls were processed the same way as all other tissue except that F-actin was not labeled and the tissue was not incubated with the primary antibody. Z-plane thicknesses were 1.1 μm for the laminin control image and 0.8 μm for the CD31 control image. Both images are from Eye 073.

The distribution of F-actin within cells in the outflow pathway was strongly dependent on the location of the cell. For SCE cells on the inner wall, F-actin was most prominently observed in a band that often appeared to run around the periphery of the cell (Fig. 6). This “marginal band” was evident near the apex of the cell, and continued down nearly to the basal aspects of the cell. Frequently this band was associated with structures that we presume were giant vacuoles, as characterized by an offset, crescent-shaped nucleus, an apparently empty central region, and a “height” of ∼3 μm in the apical-basal direction. As the basal aspect of the cell was approached (as judged by proximity to the maximum laminin labeling) actin filaments were also present in the central aspects of the cell, but they tended to be thinner and sparser than the actin near the cell margin (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Confocal laser scanning micrographs (Z-series) through inner wall and juxtacanalicular tissue of a normal eye. F-actin is labeled blue, nuclei are labeled green, and laminin is labeled red. A structure that is putatively a giant vacuole can be seen in the Z = 0 micrograph (arrowhead) and can be followed through the entire series. Note the focal opening in the laminin staining at the “bottom” of this giant vacuole (arrow). Filamentous actin in inner wall cells is primarily concentrated in thick bands concentrated near the periphery of the cell, whereas F-actin in the juxtacanalicular tissue is much more disorganized and apparently randomly oriented (asterisk). Z-locations refer to distance below the topmost image, which is arbitrarily taken to be at location Z = 0. Z-plane thicknesses were 0.8 μm for all images. Images are from Eye 330OS.

Cells in the juxtacanalicular tissue (adjacent to SCE cells), on the other hand, showed a much more isotropic and apparently random actin-labeling pattern (Fig. 6). The labeled actin filaments within the juxtacanalicular tissue were consistently thinner than the filaments in inner wall SCE cells. Despite looking at many Z-series, we could not identify a consistent pattern of filamentous actin arrangement within cells in the juxtacanalicular tissue.

More insight into filamentous actin distribution in SCE inner wall cells was obtained from samples labeled for both F-actin and the endothelial cell membrane-associated molecule CD31. Generally, prominent F-actin bands were colocalized with regions staining for CD31 (Fig. 7). However, we also observed locations with prominent F-actin bands and little or no CD31 labeling, as well as regions with strong CD31 staining that lacked actin labeling. It was unclear whether the lack of colocalization of thick F-actin bands and CD31 labeling was due to some regions of the cell membrane being CD31 negative, or whether some prominent F-actin bands did not reside on the cell margin, or both. It appeared to us that only SCE cells (but not juxtacanalicular tissue cells) labeled positively for CD31.

FIGURE 7.

Confocal laser scanning micrographs (Z-series) through inner wall and juxtacanalicular tissue of a normal eye. F-actin is labeled blue, nuclei are labeled green, and CD31 is labeled red. Each pair of images represents the same tissue region and Z-plane; the F-actin and CD31 labels have been shown separately to facilitate comparison and colocalization of these two labels. In some regions there is excellent colocalization of F-actin and CD31 (arrowheads), whereas in other regions there is little colocalization (arrows). Z-locations refer to distance below the topmost image, which is arbitrarily taken to be at location Z = 0. Z-plane thicknesses were 0.8 μm for all images. Images are from Eye 330OD.

SCE cells on the outer wall of the canal had an F-actin distribution that was quite different than seen for inner wall SCE cells. For most regions of the outer wall, there was no obvious marginal filamentous actin band; instead, actin was distributed in fairly prominent fibers throughout much of the cell, having a more stellate appearance (Fig. 8). However, in isolated portions of the outer wall, an actin staining pattern similar to that seen for inner wall SCE cells was observed. We hypothesize that these regions corresponded to previously observed filtering portions of the outer wall, where aqueous humor “goes around” the canal and enters by crossing the outer wall. Laminin staining underneath outer wall SCE cells was more patchy and discontinuous than that seen under inner wall cells. Actin within scleral fibroblasts was arranged into thick, prominent linear bundles that were fairly isotropically distributed with the cells.

FIGURE 8.

Confocal laser scanning micrographs (Z-series) through outer wall and sclera of a normal eye. F-actin is labeled blue, nuclei are labeled green, and laminin is labeled red. Note the fine filamentous actin that runs throughout the cell in the outer wall cells (arrowheads). In contrast, the actin filaments in scleral fibroblasts are thicker and more elongated (arrow). Z-locations refer to distance below the topmost image, which is arbitrarily taken to be at location Z = 0. Z-plane thicknesses were 0.8 μm for all images. Images taken from Eye 330OS.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that Schlemm's canal endothelial cells are exposed to a complex biomechanical environment, and that this environment has profound effects on F-actin distribution in the cells.

SCE cells are exposed to a variety of biomechanical forces

SCE cells are exposed to a combination of shear stress and (for inner wall cells) a significant basal-to-apical pressure gradient. Even though the aqueous humor flow rate is very small, a theoretical calculation suggests that the magnitude of the shear stress can reach values close to those in the arterial system. This is consistent with the observed alignment of SCE cells. Arterial caliber is regulated in part by wall shear stress, both acutely and chronically (Langille and O'Donnell, 1986; Zarins et al., 1987) through regulation of matrix metalloproteinase production (Haseneen et al., 2003; Magid et al., 2003; Sho et al., 2002). Further research is needed to determine if the size of Schlemm's canal is controlled by similar factors.

The magnitude of basal-to-apical pressure gradient is not known definitively and is the subject of some controversy (see, e.g., Ethier, 2002), but most estimates place it in the range of 0.7 mmHg, corresponding to 10% of the pressure drop between IOP and episcleral venous pressure. This is presumably much smaller that the pressure gradient across endothelial cells in the vascular system, and does not seem large in absolute terms. However, because of the basal-to-apical orientation of the pressure difference, large cellular deformations result and appear to have important biomechanical consequences.

Although there was a statistically significant coalignment of inner and outer wall Schlemm's canal endothelial cells, not all cells were perfectly coaligned and some were even at 90° to each other (Fig. 3). This suggests that the shear stress is not uniformly high enough in Schlemm's canal to force coalignment. There are three possible reasons for this: first, our model predicts that shear stress decreases away from collector channel ostia, so that more alignment should be seen near ostia. This is consistent with experimental observations. Second, the model also predicts circumferential variation in shear stress, with minimum values occurring at the anterior and posterior “tips” of the canal. Unfortunately, due to the dissection process these “tips” are where the canal is cut open, so that we cannot directly observe them to see if cellular alignment is minimal there. Third, and most importantly, the model predicts that shear stress depends strongly on inner-outer wall separation (“canal height”). Based on data in Allingham et al. (1996) the average inner-outer wall spacing is ∼8 μm in normal eyes and 6 μm in glaucomatous eyes. It should be appreciated that this is an average value that can vary significantly within an eye and from instant to instant depending on IOP (see, e.g., figures in Johnstone and Grant, 1973 or Allingham et al., 1996). This implies that some regions of the canal have inner-outer wall separations that are well within the range predicted to lead to biologically significant shear stresses, whereas other regions may be too “wide”.

F-actin distribution varies significantly between different cells in the outflow pathway

Particularly interesting is the difference between SCE cells on the inner and outer walls of Schlemm's canal. Because inner and outer wall SCE cells have a common embryologic origin (Ethier, 2002), it seems very likely that differences in F-actin architecture are most likely explained by differences in the biomechanical environment between the inner and outer wall of Schlemm's canal. Inner wall SCE cells are anchored to a fairly deformable substrate (the juxtacanalicular tissue) and are subjected to a basal-to-apical pressure gradient that causes large deformations. Outer wall cells reside on the relatively inextensible sclera (at least in nonfiltering portions of the outer wall), and generally do not experience the basal-to-apical pressure gradient and large deformations of inner wall cells. Overall, inner-wall SCE cells should experience much higher levels of mechanical stretch than outer-wall SCE cells, and this may explain our observed differences in F-actin architecture.

Biomechanically driven differences in F-actin architecture may also explain the very different architecture that F-actin assumes in SCE cells grown under static culture conditions. For example, Fig. 2 B in Epstein et al. (1999) shows prominent stress fibers running through the entire cell, with no preferential accumulation of F-actin bundles in the periphery of the cell. This differs from both inner and outer wall cells in situ, and illustrates a potential limitation of static cell culture that should be kept in mind in studies that investigate agents that act on F-actin architecture.

It is interesting how random and isotropic the F-actin arrangement in juxtacanalicular tissue cells is when compared to inner wall SCE cells. This may be in part due to the fact that juxtacanalicular tissue cells are randomly oriented within the juxtacanalicular tissue, so that images from a single optical section plane will sample a random distribution of actin filament orientations. However, even taking this into account, the F-actin seems thinner and more disordered in juxtacanalicular tissue cells than in inner-wall SCE cells. This might be in part due to the fact that inner-wall SCE cells experience forces predominantly in one direction (basal-to-apical), whereas juxtacanalicular tissue cells reside in a more complex biomechanical environment, being subjected to pressure gradients associated with local aqueous humor flow (including a possible circumferential component of drainage) and tension from longitudinal ciliary muscle fibers whose elastic tendons terminate in the juxtacanalicular tissue (Rohen and Lütjen-Drecoll, 1989).

Acknowledgments

We thank Bruce Roberts for helpful suggestions about the Schlemm's canal dissection procedure, and Dr. Abe Clark for stimulating discussions. We also thank the donor's families and the staff at the Eye Bank of Canada (Ontario Division) and NDRI (Philadelphia, PA) for providing tissue used in this work.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant MA-10051), the Glaucoma Research Society of Canada, and an unrestricted grant from Alcon Pharmaceuticals.

References

- Allingham, R. R., A. W.de Kater, and C. R. Ethier. 1996. Schlemm's canal and primary open angle glaucoma: correlation between Schlemm's canal dimensions and outflow facility. Exp. Eye Res. 62:101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill, A., and B. Svedbergh. 1972. Scanning electron microscopic studies of the trabecular meshwork and the canal of Schlemm: an attempt to localize the main resistance to outflow of aqueous humor in man. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh.). 50:295–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brilakis, H. S., C. R. Hann, and D. H. Johnson. 2001. A comparison of different embedding media on the ultrastructure of the trabecular meshwork. Curr. Eye Res. 22:235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. C. 1978. Introductory Applied Statistics in Science. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- de Kater, A. W., A. Shahsafaei, and D. L. Epstein. 1992. Localization of smooth muscle and nonmuscle actin isoforms in the human aqueous outflow pathway. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 33:424–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, D. L., L. L. Rowlette, and B. C. Roberts. 1999. Acto-myosin drug effects and aqueous outflow function. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 40:74–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier, C. R. 2002. The inner wall of Schlemm's canal. Exp. Eye Res. 74:161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier, C. R., P. Ajersch, and R. Pirog. 1993. An improved ocular perfusion system. Curr. Eye Res. 12:765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier, C. R., and D. W. Chan. 2001. Cationic ferritin changes outflow facility in human eyes whereas anionic ferritin does not. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42:1795–1802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier, C. R., and F. M. Coloma. 1999. Effects of ethacrynic acid on Schlemm's canal inner wall and outflow facility in human eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 40:1599–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier, C. R., F. M. Coloma, A. J. Sit, and M. Johnson. 1998. Two pore types in the inner-wall endothelium of Schlemm's canal. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 39:2041–2048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flügel, C., E. R. Tamm, E. Lütjen-Drecoll, and F. H. Stefani. 2002. Age-related loss of α-smooth muscle actin in normal and glaucomatous human trabecular meshwork of different age groups. J. Glaucoma. 1:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Gipson, I. K., and R. A. Anderson. 1979. Actin filaments in cells of human trabecular meshwork and Schlemm's canal. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 18:547–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grierson, I., and W. R. Lee. 1975. Pressure-induced changes in the ultrastructure of the endothelium lining Schlemm's canal. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 80:863–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamanaka, T., A. Bill, R. Ichinohasama, and T. Ishida. 1992. Aspects of the development of Schlemm's canal. Exp. Eye Res. 55:479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann, C. R., M. J. Springett, X. Wang, and D. H. Johnson. 2001. Ultrastructural localization of collagen IV, fibronectin, and laminin in the trabecular meshwork of normal and glaucomatous eyes. Ophthalmic Res. 33:314–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haseneen, N. A., G. G. Vaday, S. Zucker, and H. D. Foda. 2003. Mechanical stretch induces MMP-2 release and activation in lung endothelium: role of EMMPRIN. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 284:L541–L547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, M. J., J. A. Alvarado, and J. E. Weddel. 1971. Histology of the Human Eye. W. B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA.

- Johnson, M., and K. Erickson. 2000. Mechanisms and routes of aqueous humor drainage. In Principles and Practices of Ophthalmology. D. M. Albert and F. A. Jakobiec, editors. W. B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA. 2577–95.

- Johnson, M., and R. D. Kamm. 1983. The role of Schlemm's canal in aqueous outflow from the human eye. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 24:320–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, M. A., and W. M. Grant. 1973. Pressure-dependent changes in structures of the aqueous outflow system of human and monkey eyes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 75:365–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn, J. 1999. Expression of factor VIII-related antigen in human aqueous drainage channels. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 77:9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langille, B. L., and F. O'Donnell. 1986. Reductions in arterial diameter produced by chronic decreases in blood flow are endothelium-dependent. Science. 231:405–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutjen-Drecoll, E., and J. W. Rohen. 1970. [Endothelial studies of the Schlemm's canal using silver-impregnation technic] Albrecht. Von. Graefes Arch. Klin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 180:249–266. [In German] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid, R., T. J. Murphy, and Z. S. Galis. 2003. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in endothelial cells is differentially regulated by shear stress. Role of c-Myc. J. Biol. Chem. 278:32994–32999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, G. E., A. G. Konstas, and W. R. Lee. 1990. Immunogold localization of type IV collagen and laminin in the aging human outflow system. Exp. Eye Res. 51:691–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses, R. A. 1979. Circumferential flow in Schlemm's canal. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 88:585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J. A., B. Tian, A. D. Bershadsky, T. Volberg, R. E. Gangnon, I. Spector, B. Geiger, and P. L. Kaufman. 1999. Latrunculin-A increases outflow facility in the monkey. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 40:931–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J. A., B. Tian, B. Geiger, and P. L. Kaufman. 2000a. Effect of latrunculin-B on outflow facility in monkeys. Exp. Eye Res. 70:307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J. A., B. Tian, J. W. McLaren, W. C. Hubbard, B. Geiger, and P. L. Kaufman. 2000b. Latrunculins' effects on intraocular pressure, aqueous humor flow, and corneal endothelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41:1749–1758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, H. A. 1996. Number of people with glaucoma worldwide. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 80:389–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohen, J. W., and E. Lütjen-Drecoll. 1989. Morphology of aqueous outflow pathways in normal and glaucomatous eyes. In The Glaucomas. R. Ritch, M. B. Shields, and T. Krupin, editors. C. V. Mosby, St. Louis, MO. 41–74.

- Sabanay, I., B. T. Gabelt, B. Tian, P. L. Kaufman, and B. Geiger. 2000. H-7 effects on the structure and fluid conductance of monkey trabecular meshwork. Arch. Ophthalmol. 118:955–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R. K., and A. L. London. 1978. Laminar Flow Forced Convection in Ducts: A Source Book for Compact Heat Exchanger Analytical Data. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- Sho, E., M. Sho, T. M. Singh, H. Nanjo, M. Komatsu, C. Xu, H. Masuda, and C. K. Zarins. 2002. Arterial enlargement in response to high flow requires early expression of matrix metalloproteinases to degrade extracellular matrix. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 73:142–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, B., B. Geiger, D. L. Epstein, and P. L. Kaufman. 2000. Cytoskeletal involvement in the regulation of aqueous humor outflow. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41:619–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, B., P. L. Kaufman, T. Volberg, B. T. Gabelt, and B. Geiger. 1998. H-7 disrupts the actin cytoskeleton and increases outflow facility. Arch. Ophthalmol. 116:633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittitow, J. L., R. Garg, L. L. Rowlette, D. L. Epstein, E. T. O'Brien, and T. Borras. 2002. Gene transfer of dominant-negative RhoA increases outflow facility in perfused human anterior segment cultures. Mol. Vis. 8:32–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederholt, M., H. Thieme, and F. Stumpff. 2000. The regulation of trabecular meshwork and ciliary muscle contractility. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 19:271–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarins, C. K., M. A. Zatina, D. P. Giddens, D. N. Ku, and S. Glagov. 1987. Shear stress regulation of artery lumen diameter in experimental atherogenesis. J. Vasc. Surg. 5:413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]