Abstract

We compared secretion kinetics for four different fluorescent cargo proteins, each targeted to the lumen of insulin secretory vesicles. Upon stimulation, individual vesicles displayed one of four distinct patterns of fluorescence change: i), disappearance, ii), dimming, iii), transient brightening, or iv), persistent brightening. For each fusion protein, a different pattern of fluorescence change dominated. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the dominant pattern depends upon both i), the specific choice of fluorescent protein, and ii), the sequence of amino acids linking the cargo protein to the fluorescent protein. Thus, in β-cells, experiments involving fluorescent cargo proteins for the study of exocytosis must be interpreted carefully, as design of a fluorescent cargo protein determines secretion kinetics at exocytosis.

Each of four different fluorescent cargo proteins was designed to be secreted at exocytosis, consisting of insulin C-peptide fused to either i), emerald GFP (C-emGFP) or ii), TIMER protein (C-TIMER), iii), rat islet amyloid polypeptide fused to EGFP (rIAPP-EGFP) or iv), syncollin fused to EGFP (syncollin-EGFP). We used adenovirus (1) to express these proteins in primary cultures of pancreatic β-cells and total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy (2) to image individual insulin vesicles at the base of the cell, where plasma membrane approached the coverslip. Each construct was tested independently. Punctate fluorescence appeared at the plasma membrane and deep within the cell by 24–36 h after viral transduction. For all constructs, spots not only had similar membrane-proximal density and size, but also exhibited stimulated fluorescence changes after cells were depolarized. These results are consistent with labeling of insulin vesicles (3–5).

To stimulate exocytosis, the concentration of extracellular potassium was transiently elevated, causing cells to depolarize and calcium to enter. Upon stimulation, a fraction of the vesicle population responded with one of four distinct patterns of fluorescence change: i), disappearance (Fig. 1, A and B), ii), dimming (Fig. 1 C), iii), transient brightening (Fig. 1 D), or iv), persistent brightening (Fig. 1 E). For all constructs, a similar number of vesicles changed fluorescence intensity. Unlike what was seen in PC12 cells (6), vesicles in pancreatic β-cells displayed a preferred pattern of fluorescence change, depending upon which fluorescent cargo protein was used as label. Two of the probes behaved consistently: almost every responding vesicle labeled with C-emGFP disappeared, whereas responding vesicles labeled with rIAPP-EGFP brightened persistently. Responses for vesicles labeled with either C-TIMER or syncollin-EGFP varied widely.

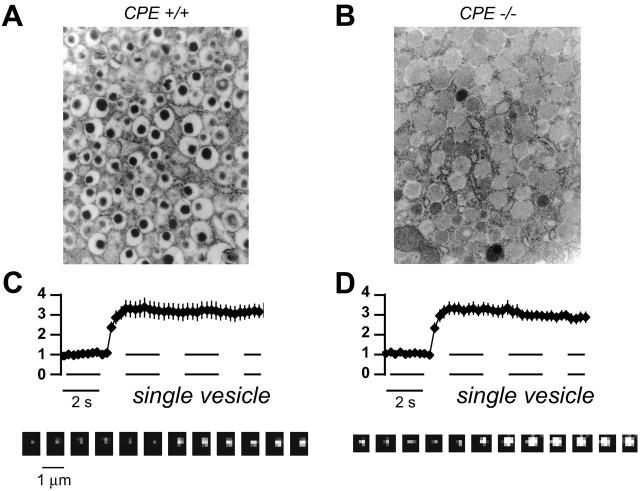

FIGURE 1.

Depolarization stimulated heterogeneous patterns of fluorescence change for fluorescent cargo proteins expressed in pancreatic β-cells. (A) High speed imaging of C-emGFP revealed transient brightening and rapid release, as fluorescence collapsed to background within 200 ms. (B–E) Single vesicles (montages and top traces) responded with four patterns of fluorescence change and, as indicated, each fluorescent cargo protein had a preferred pattern. Whole-cell fluorescence changes (middle traces) paralleled changes at the single-vesicle level, whereas fluorescence 3 μm from the edge of the cell (bottom traces) increased regardless of fluorescence changes for single vesicles, suggesting that protein was released and diffused away. Arrows indicate application of elevated potassium. For detailed descriptions of figures, see Supplementary Material.

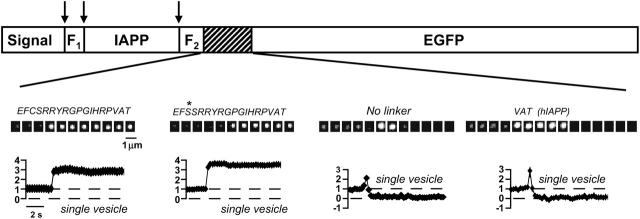

Persistent brightening of rIAPP-EGFP could be explained if rIAPP-EGFP is trapped in a slowly dissolving insulin-zinc crystal that is fully released, relieving the acidic quenching of EGFP that normally occurs in the vesicle lumen (7). But this hypothesis is not consistent with our results from mice lacking carboxypeptidase E (CPE), an enzyme essential for formation of an insulin-zinc core (8): rIAPP-EGFP behaved similarly in β-cells isolated from mice expressing (+/+) or lacking CPE (−/−) (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Persistent brightening of rIAPP-EGFP does not require an insulin/zinc electron-opaque core (A versus B) as demonstrated by the similar behaviors of vesicles labeled with rIAPP-EGFP in β-cells from CPE +/+ and CPE −/− mice (C versus D).

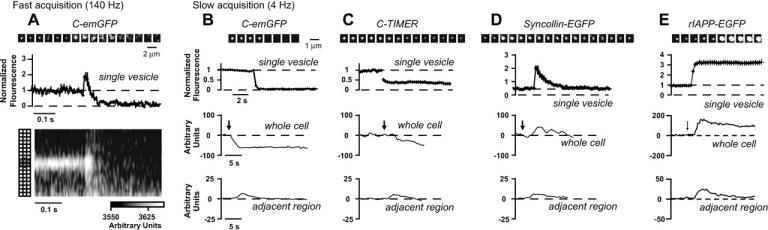

Our results with rIAPP-EGFP differ markedly from the transient brightening and frequent disappearance previously reported for vesicles labeled with human IAPP-EGFP (hIAPP-EGFP), a probe tested by transfection of clonal beta cells (INS-1) (3). Several mechanisms could explain this difference. First, we compared the behavior of vesicles labeled with each of these IAPP contructs by independently transfecting them into clonal beta cells (RIN). As the behavior of vesicles labeled with rIAPP-EGFP remained different from those labeled with hIAPP-EGFP (Fig. 3), we eliminated the method of DNA delivery (viral transduction versus plasmid transfection) and the source of the β-cells (primary culture versus clonal) as potential mechanisms to explain the observed difference. Next, we considered the sequence of amino acids linking rIAPP to EGFP. Because cysteine residues in this region can increase oligomerization of fusion proteins expressed in pancreatic β-cells (9), and oligomerization might hinder release from a vesicle, we substituted serine for the lone cysteine residue in this region of our rIAPP-EGFP construct. However, vesicles labeled with this modified rIAPP-EGFP construct continued to brighten persistently (Fig. 3), ruling out this mechanism as a possible source of the different behaviors. Finally, we removed all amino acids linking rIAPP to EGFP. When vesicles were labeled with this “linkerless” rIAPP-EGFP construct, their behavior closely resembled the behavior previously reported for hIAPP-EGFP (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Design of a fluorescent cargo protein determines secretion kinetics at exocytosis. In pancreatic β-cells, the amino acid sequence (shown in italics) linking IAPP to EGFP influenced the behavior of labeled vesicles at exocytosis. Arrows indicate processing sites.

In conclusion, we have shown that the behavior of a fluorescent cargo protein at exocytosis may be strongly influenced by protein domains introduced during assembly of the fusion protein. In the four specific constructs we examined, the choice of the fluorescent protein (Fig. 1) and linker domain (Fig. 3) significantly affected the behavior of the fluorescent fusion protein at exocytosis. These results indicate that the behavior of fluorescent fusion proteins at exocytosis may not reflect the behavior of native cargo proteins. More generally, the results highlight the caution necessary when interpreting behavior of foreign fusion proteins expressed in living cells.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Carina Ämmälä and Tatyana Gurlo for technical advice, Sebastian Barg for providing hIAPP-EGFP, Kalpit Gajera for software, and Robert Ritzel, Leena Haataja, Peter Butler, Maryann Vogelsang, and Lou Byerly for helpful discussions.

This work was funded by intramural (Y.P.L.) and extramural grants from the National Institutes if Health: DK10181 (D.J.M), DK47919 (C.J.R.), and DK60623 (R.H.C.).

References

- (1).For detailed Methods, see Supplementary Material.

- (2).Axelrod, D. 2001. Selective imaging of surface fluorescence with very high aperture microscope objectives. J. Biomed. Opt. 6:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Barg, S., C. S. Olofsson, J. Schriever-Abeln, A. Wendt, S. Gebre-Medhin, E. Renstrom, and P. Rorsman. 2002. Delay between fusion pore opening and peptide release from large dense-core vesicles in neuroendocrine cells. Neuron. 33:287–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ohara-Imaizumi, M., Y. Nakamichi, T. Tanaka, H. Ishida, and S. Nagamatsu. 2002. Imaging exocytosis of single insulin secretory granules with evanescent wave microscopy: distinct behavior of granule motion in biphasic insulin release. J. Biol. Chem. 277:3805–3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Tsuboi, T., and G. A. Rutter. 2003. Multiple forms of “kiss-and run” exocytosis revealed by evanescent wave microscopy. Curr. Biol. 13:563–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Holroyd, P., T. Lang, D. Wenzel, P. De Camilli, and R. Jahn. 2002. Imaging direct, dynamin-dependent recapture of fusing secretory granules on plasma membrane lawns from PC12 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:16806–16811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Han, W. P., D. Q. Li, A. K. Stout, K. Takimoto, and E. S. Levitan. 1999. Ca2+-induced deprotonation of peptide hormones inside secretory vesicles in preparation for release. J. Neurosci. 19:900–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Naggert, J. K., L. D. Fricker, O. Varlamov, P. M. Nishina, Y. Rouille, D. F. Steiner, R. J. Carroll, B. J. Paigen, and E. H. Leiter. 1995. Hyperproinsulinaemia in obese fat/fat mice associated with a carboxypeptidase E mutation which reduces enzyme-activity. Nat. Genet. 10:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Jain, R. K., P. B. M. Joyce, M. Molinete, P. A. Halban, and S. U. Gorr. 2001. Oligomerization of green fluorescent protein in the secretory pathway of endocrine cells. Biochem. J. 360:645–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.