Abstract

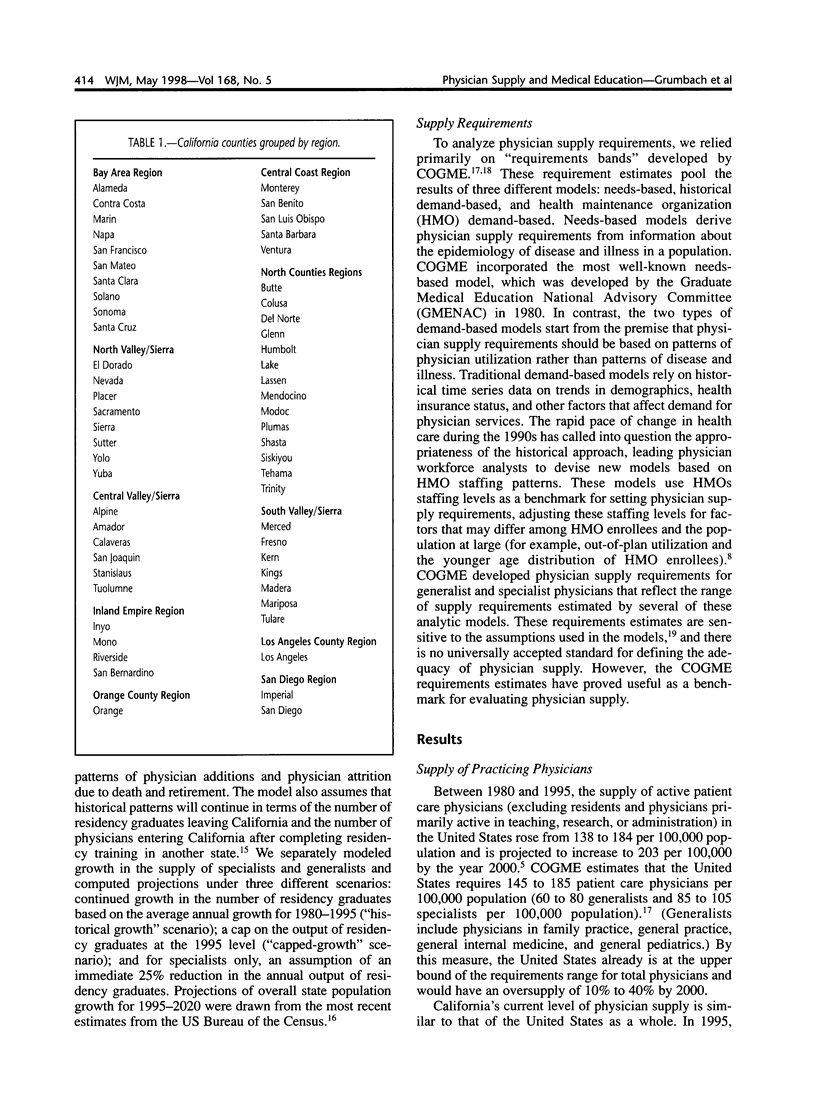

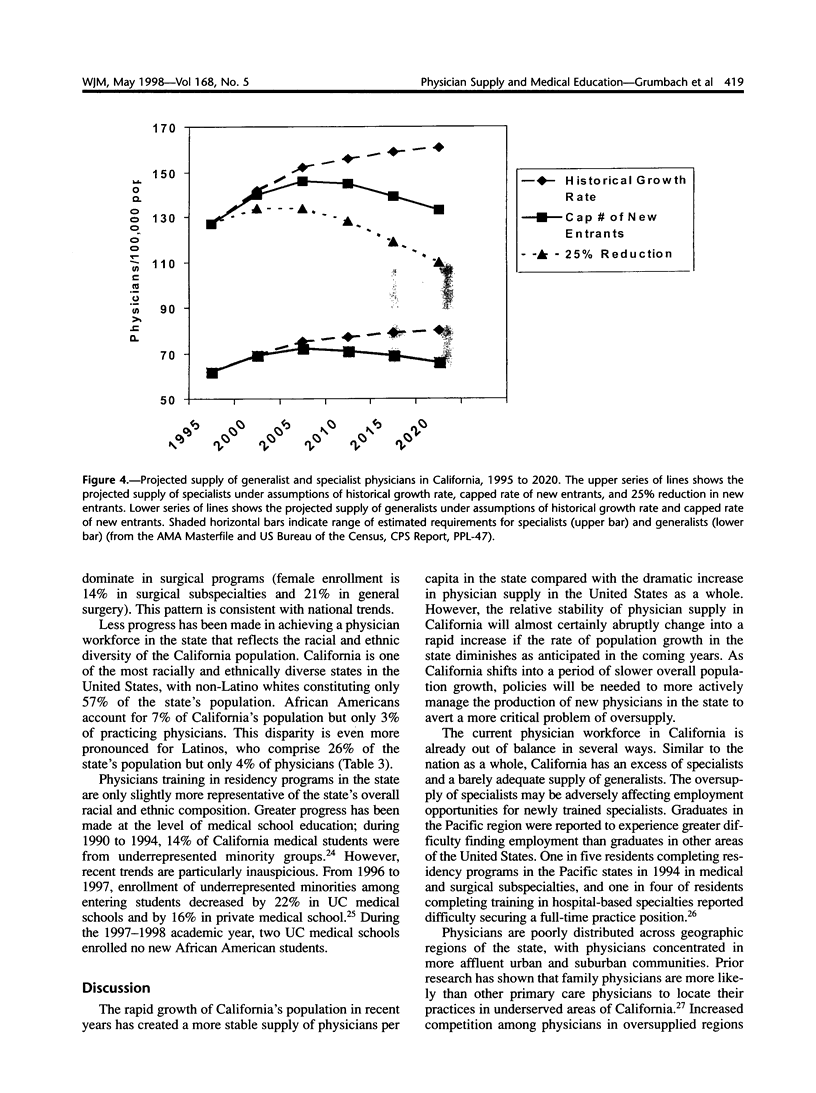

Concerns have been voiced about an impending oversupply of physicians in the United States. Do these concerns also apply to California, a state with many unique demographic characteristics? We examined trends in physician supply and medical education in California and the United States between 1980 and 1995 to better inform the formulation of workforce policies appropriate to the state's requirements for physicians. We found that similar to the United States, California has more than an ample supply of physicians in the aggregate, but too many specialists, too few underrepresented racial/ethnic minority physicians, and poor distribution of physicians across the state. However, recent growth in the supply of practicing physicians and resident physicians per capita in California has been much less dramatic than in the country overall. The state's unusually high rate of population growth has enabled California, unlike the United States as a whole, to absorb large increases in the number of practicing physicians and residents during 1980 to 1995 without substantially increasing the physician-to-population ratio. Due to a projected slowing of the state's rate of population growth, the supply of physicians per capita in the state will begin to rise steeply in coming years unless the state implements prompt reductions in the production of specialists. An immediate 25% reduction in specialist residency positions would be necessary to bring the state's supply of practicing specialists in line with projected physician requirements for the state by 2020. We conclude that major changes will be required if the state's residency programs and medical schools are to produce the number and mix of physicians the state requires. California's medical schools and residency programs will need to act in concert with federal and state government to develop effective policies to address the imbalance between physician supply and state requirements.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Burnett W. H., Mark D. H., Midtling J. E., Zellner B. B. Primary care physicians in underserved areas. Family physicians dominate. West J Med. 1995 Dec;163(6):532–536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor J. C., Miles E. L., Baker L. C., Barker D. C. Physician service to the underserved: implications for affirmative action in medical education. Inquiry. 1996 Summer;33(2):167–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R. A. Perspectives on the physician workforce to the year 2020. JAMA. 1995 Nov 15;274(19):1534–1543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumbach K., Lee P. R. How many physicians can we afford? JAMA. 1991 May 8;265(18):2369–2372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn N. B., Jr, Garner J. G., Schmittling G. T., Ostergaard D. J., Graham R. Results of the 1997 National Resident Matching Program: family practice. Fam Med. 1997 Sep;29(8):553–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn N. B., Jr, Schmittling G., Ostergaard D., Graham R. Specialty practice of family practice residency graduates, 1969 through 1993. A national study. JAMA. 1996 Mar 6;275(9):713–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komaromy M., Grumbach K., Drake M., Vranizan K., Lurie N., Keane D., Bindman A. B. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996 May 16;334(20):1305–1310. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605163342006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. S., Jonas H. S., Whitcomb M. E. The initial employment status of physicians completing training in 1994. JAMA. 1996 Mar 6;275(9):708–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullan F., Politzer R. M., Davis C. H. Medical migration and the physician workforce. International medical graduates and American medicine. JAMA. 1995 May 17;273(19):1521–1527. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520430057039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politzer R. M., Gamliel S. R., Cultice J. M., Bazell C. M., Rivo M. L., Mullan F. Matching physician supply and requirements: testing policy recommendations. Inquiry. 1996 Summer;33(2):181–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivo M. L., Kindig D. A. A report card on the physician work force in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1996 Apr 4;334(14):892–896. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604043341405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsberg E. S., Wing P., Dionne M. G., Jemiolo D. J. Graduate medical education and physician supply in New York State. JAMA. 1996 Sep 4;276(9):683–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifer S. D., Vranizan K., Grumbach K. Graduate medical education and physician practice location. Implications for physician workforce policy. JAMA. 1995 Sep 6;274(9):685–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J. P. Forecasting the effects of health reform on US physician workforce requirement. Evidence from HMO staffing patterns. JAMA. 1994 Jul 20;272(3):222–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]