Abstract

The glutamate at site 224 of a Kir2.1 channel plays an important role in K+ permeation. The single-channel inward current flickers with reduced conductance in an E224G mutant. We show that open-channel fluctuations can also be observed in E224C, E224K, and E224Q mutants. Yet, open-channel fluctuations were not observed in either the wild-type or an E224D mutant. Introducing a negatively charged methanethiosulfonate reagent to the E224C mutant irreversibly increased channel conductance and eliminated open-channel fluctuations. These results suggest that although the negatively charged residue 224 is located at the internal vestibule, it is important for smooth inward K+ conduction. We identified a substate in the E224G mutant and showed that open-channel fluctuations are mainly attributed to rapid transitions between the substate and the main state. Also, we characterized the voltage- and ion-dependence of the substate kinetics. The open-channel fluctuations decreased in internal  or Tl+ as compared to internal K+. These results suggest that

or Tl+ as compared to internal K+. These results suggest that  and Tl+ gate the E224G mutant in a more stable state. Based on an ion-conduction model, we propose that the appearance of the substate in the E224G mutant is due to changes of ion gating in association with variations of ion-ion interaction in the permeation pathway.

and Tl+ gate the E224G mutant in a more stable state. Based on an ion-conduction model, we propose that the appearance of the substate in the E224G mutant is due to changes of ion gating in association with variations of ion-ion interaction in the permeation pathway.

INTRODUCTION

Inward rectifier K+ channels play an important role in maintaining the resting membrane potential and controlling the excitability of many excitable cells. Their physiological functions are closely related to the unique property of inward rectification, which permits much more K+ flux inward than outward. The mechanisms underlying inward rectification have been ascribed to the voltage (Vm)-dependent block of outward currents by internal Mg2+ and polyamines (Matsuda et al., 1987; Vandenberg, 1987; Ficker et al., 1994; Lopatin et al., 1994). In the cloned inward rectifier K+ channel, Kir2.1 (Kubo et al., 1993), the aspartate at site 172 (D172) (Stanfield et al., 1994; Lu and MacKinnon, 1994; Ficker et al., 1994; Lopatin et al., 1994), glutamate at site 224 (E224) (Yang et al., 1995), and glutamate at site 299 (E299) (Kubo and Murata, 2001) have been shown to be involved in the binding of internal Mg2+ and polyamines.

In the tetrameric structure of a Kir2.1 channel, the four E224 form a ring of negative charges and play an important role in K+ permeation. It has been shown that the inward single-channel current conducted by K+ through the E224G mutant flickers with reduced conductance (Yang et al., 1995; Kubo and Murata, 2001). Several studies have suggested that rings of negative charges located in the narrow pores and pore mouths of ion channels may control single-channel conductance through electrostatic mechanisms (ion-concentrating and surface charge effects) (Imoto et al., 1988; MacKinnon et al., 1989; Xie et al., 2002; Brelidze et al., 2003; Nimigean et al., 2003). However, the underlying mechanisms for the effects of a ring of negative charges on inducing open-channel fluctuations have not been discussed. The open-channel fluctuations in the E224G mutant seem to occur between the main state and a nonzero conductance state. Ion channels are characterized by a main conductance state. However, many of these channels also display substates. In fact, substates have been observed in native IK1 (Sakmann and Trube, 1984; Matsuda, 1988) and the Kir2.1 channel (Lu et al., 2001). It is possible that the open-channel fluctuations in the E224G mutant are produced by fast fluctuations between substates and the main state.

Although the half-amplitude threshold analysis is a well-accepted method, it is not suitable for analyzing the single-channel recordings displaying more than one level of current amplitude and fast kinetics. In this study, we analyzed the single-channel properties in the E224G mutant using a method based on the construction and analysis of mean-variance (M-V) histograms (Patlak, 1993; Lischka et al., 1999). We identified at least one substate in the E224G mutant. The open-channel fluctuations were attributed to rapid transitions of the channel between the substate and main state. By carrying out cysteine modification experiments, we also demonstrated that introducing a negative charge back to site 224 restores the smooth and large conductance in the Kir2.1 channel. We also investigated the effects of Vm, [K+], and permeant ion species on the single-channel kinetics of the E224G mutant. Although screening the ring of negative charges at site 224 may reduce single-channel conductance (Xie et al., 2002), it alone cannot explain why the single channel fluctuates between different states. Based on the ion conductance mechanism elucidated by a crystal structure (Morais-Cabral et al., 2001), we propose that the open-channel fluctuations in the E224G mutant is most likely due to the neutralization of the residue at site 224, which results in variations of ion gating in coupling to changes of ion-ion interaction. Following our previous finding that K+-K+ interaction around site 148 is important for permeation through the Kir2.1 channel (Shieh et al., 1999), we show in this study that an ion-binding site located at the internal vestibule also plays a critical role in ion conduction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular biology and preparation of Xenopus oocytes

Mutations were constructed by using the “Altered Sites II: in vitro Mutagenesis Systems” (Promega, Madison, WI). The E224C mutant was generated in the methanethiosulfonate (MTS)-insensitive channel IRK1J (C54V, C76V, C89I, C101L, C149F, and C169V) (Lu et al., 1999a). The cRNA was obtained by in vitro transcription (mMessage mMachine, Ambion, Dallas, TX). Xenopus oocytes were isolated by partial ovariectomy from frogs anaesthetized with 0.1% tricaine (3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester). The incision was sutured and the animal was monitored during the recovery period before it was returned to its tank. After the final oocyte collection, frogs were anaesthetized as described above and sacrificed by decapitation. All surgical and anesthetic procedures were reviewed and approved by the Academia Sinica Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee. Oocytes were maintained at 18°C in Barth's solution containing (in mM) NaCl (88), KCl (1), NaHCO3 (2.4), CaN2O6 (0.3), CaCl2 (0.41), MgSO4 (0.82), and HEPES (15), pH 7.6, with gentamicin (20 μg/ml). Oocytes were used 1–3 days after cRNA injection.

Electrophysiology

Single-channel recordings, unless otherwise specified, were sampled at 20 kHz and filtered at 4 kHz using the patch-clamp technique (Hamill et al., 1981) with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) at room temperature (22°–24°C). Patch electrodes (resistance ranging from 1 to 3 MΩ) were coated with a hydrophobic mixture of parafilm and mineral oil (Hilgemann, 1995) to reduce capacitance transient and noise. The internal and external solutions contained (in mM) KCl + KOH (20–300), EDTA (5), and HEPES (5), pH 7.4. The phosphate-buffered solution contained (in mM) KCl + KOH (82), EDTA (5), K2HPO4 (8), and KH2PO4 (2), pH 7.4. In ion-dependent experiments, 100 mM [K+] was replaced by equimolar  [Tl+], [Rb+], [Na+], or [NMG+]. 2-Sulfonatoethylmethane thiosulfonate (MTSES) and 2-trimethylammonioethylmethane thiosulfonate (MTSET) (Toronto Research Chemicals, North York, Canada) were stored at −20°C and dissolved immediately before application. Rundown of channel activity was delayed by treating inside-out patches with 25 μM L-α-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2, Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) (Huang et al., 1998). Temperature was controlled and monitored using a TC-10 heating and cooling temperature controller (Dagan, Minneapolis, MN).

[Tl+], [Rb+], [Na+], or [NMG+]. 2-Sulfonatoethylmethane thiosulfonate (MTSES) and 2-trimethylammonioethylmethane thiosulfonate (MTSET) (Toronto Research Chemicals, North York, Canada) were stored at −20°C and dissolved immediately before application. Rundown of channel activity was delayed by treating inside-out patches with 25 μM L-α-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2, Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) (Huang et al., 1998). Temperature was controlled and monitored using a TC-10 heating and cooling temperature controller (Dagan, Minneapolis, MN).

The command Vm and data acquisition functions were processed using a Pentium-based personal computer, a DigiData board, and pClamp6 software (Axon Instruments).

Data analysis

Single-channel recordings were analyzed using a free “Levels” program (Lischka et al., 1999) based on the M-V histogram method described by Patlak (1993). Briefly, the mean (〈I〉) and the variance (σ2) of the current were calculated within a “sliding window” containing w data points. The mean-variance estimates were then binned into a two-dimensional histogram. The x and y axes for the M-V histogram were the mean current and the logarithm of the variance, respectively, and the z axis was the logarithm of the number of points falling within each mean-variance bin. The closed, the substate, and the main states are represented by low-variance regions, which were selected from entries that had variances as low as and lower than the baseline current variance (≈0.4 pA2). Transitions between states produce an increased variance and appear as arcs connecting the low-variance regions. The dwell time for each state was further analyzed from the M-V histograms as follows. The volume of each low-variance region is proportional to the integral of the dwell-time distribution at that level for all times greater than the window width. The relation of the volume of the low-variance region and the window width is exponential. The time constant of this function is equal to that of the original dwell-time distributions. Thus, the M-V histograms can be used to determine dwell-time constants longer than two sample intervals (Patlak, 1993) (0.05 ms per sample interval in this study).

The volume of a low-variance region is the total number of instances in the data during which the entire window is fully within a steady current level. Therefore, the probability of the channel being at a particular state was estimated as the volume of the low-variance region divided by the total number of recorded points. The mean-channel current and the fraction of time that the channel was at a particular state were estimated by fitting the corresponding low-variance region with a Gaussian-χ2 envelope function (Patlak, 1993; Lischka et al., 1999),

|

(1) |

where Nmv is the amplitude of any single bin mv, Bm and Bv are the bin widths for the mean and variance distributions, respectively, and

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

where μ is the population mean, σ2 is the variance of the distribution of 〈I〉 around μ, and n is the number of degrees of freedom.

The current variances for the closed (σ2(C)) and open (σ2(O)) states were calculated using the Clampfit basic statistics. The values of normalized open-state variance (calculated as [σ2(O) − σ2(C)]/i) were then used to compare the magnitude of the open-channel noise among different ionic conditions. Averaged data are presented as mean ± SE. Student's independent t-test was used to assess the statistical significance.

RESULTS

Analysis of open-channel fluctuations in the E224G mutant

Fig. 1 A shows the single-channel recordings of the wild-type Kir2.1 and the E224G mutant exposed to 100 mM symmetrical [K+] at −140 mV. Consistent with what has been previously shown (Yang et al., 1995), the single-channel opening flickered rapidly in the E224G mutant but not in the wild-type channel. The fluctuations seemed to occur between a nonzero conductance state and the main state. In this study, we analyzed the single-channel properties of the E224G mutant by using a method based on the construction and analysis of M-V histograms (Patlak, 1993; Lischka et al., 1999) (see Data analysis).

FIGURE 1.

Analysis of open-channel fluctuations in the E224G mutant. (A) Traces recorded in the wild-type and the E224G mutant at −140 mV. Red boxes show the transitions between C↔S and S↔M. (B) M-V histograms with a window of three points for the 30-s records measured in the wild-type and the E224G mutant. (C) The i-V relationships for the wild type (▪), the main state (▵), and the substate (•) in the E224G mutant. (D) Vm dependence of open probability (1 − pC). (E) Dependence of volumes in the low-variance regions corresponding to the substate, the closed, and the main states on window width for the E224G mutant. The solid lines were the best fit to data with a biexponential function for the closed state and a monoexponential function for the substate and the main state. n = 3–6.

Fig. 1 B displays the M-V histograms for the single-channel recordings of the wild-type and the E224G mutant. According to the M-V method, a two-dimensional “low-variance” region characterizes each conductance level. In the wild-type channel, the histogram illustrates only two low-variance regions corresponding to the closed (C) and the main state (M, −5.7 pA). The histogram for the E224G mutant shows three low-variance regions corresponding to the closed state, the substate (S, −3 pA), and the main state (−4.7 pA). In this patch, a smaller low-variance region between the closed state and the substate was observed. This substate occurred infrequently and thus we did not quantitate this component. Interconnections between both the main and the closed state with the substate were observed (Fig. 1 B, right panel). In 1452 low-variance states connecting to the substate, 71 were C→S, 69 were S→C, 725 were O→S, and 727 were S→O (examples are shown in Fig. 1 A, red boxes). Thus, the open-channel fluctuations are mainly due to the transitions between the substate and the main state.

Fig. 1 C shows the single-channel current i-V relationships of the wild-type and the E224G channel exposed to 100 mM symmetrical [K+]. Single-channel conductance was calculated by fitting the data obtained between −80 and −140 mV to a linear function. Because extracellular divalent cations and intracellular polyamines have been shown to inhibit inward single-channel currents through the Kir2.1 channel (Sabirov et al., 1997; Alagem et al., 2001; Xie et al., 2002), we carried out experiments in the absence of divalent cations and polyamines. Also, the single-channel conductance was estimated at Vm ranges where the i-V relationship shows slightly superlinear (the range was chosen so that the data from the E224G can be accurately analyzed). As a result, the single-channel conductance reported in this study is larger than those previously reported. The single-channel conductance of the E224G mutant was slightly smaller than that in the wild-type channel. Rapid open-channel fluctuations produce a broader M-V distribution and may thus generate a smaller mean value of i.

The open probabilities (1-pC) were not Vm-dependent and were about the same in the wild-type and the E224G mutant (Fig. 1 D). Fig. 1 E illustrates the relationships of window width and the volumes in the low-variance regions corresponding to the three states. One short dwell time (τCS = 0.66 ms) and one long dwell time (τCL = 6.7 ms) were estimated in the closed state. The dwell times were ∼0.3 ms for both the substate and the main state. These results suggest that K+ permeation through the E224G mutant fluctuates rapidly between at least one substate and the main states.

Open-channel fluctuations do not arise from channel block by HEPES or PIP2

It has been previously shown that HEPES blocks outward currents through the Kir2.1 channel (Guo and Lu, 2002). To investigate whether the open-channel fluctuations in the E224G mutant are due to fast block by HEPES, we also recorded single-channel currents of the E224G mutant in a phosphate-buffered solution, which does not block outward Kir2.1 currents (Guo and Lu, 2002). Open-channel fluctuations were observed with the same kinetics in both phosphate- and HEPES-buffered solutions (data not shown). Thus, in the following experiments, we carried out experiments in HEPES-buffered solutions. We have also found that open-channel fluctuations persisted in the patches without PIP2 treatment (data not shown).

The ring of negative charges at positions 224 ensures smooth conductance

We next examined whether other mutations at the residue 224 result in single-channel fluctuations. Fig. 2 shows that the single-channel current amplitude and noise level of a E224D mutant at −140 mV is similar to the wild-type channel. However, when the glutamate at the site 224 was replaced by a neutral amino acid C (constructed in a pseudo wild-type channel, IRK1J; see below) or Q, open-channel fluctuations were observed (Vm = −140 mV). The single-channel current through an E224K mutant was not detectable at −140 mV, although small macroscopic currents could be recorded in whole cells using two-electrode-voltage-clamp (data not shown). At −200 mV, the single E224K current was very small and flickering (Fig. 2). No distinct closed state was identified and it is not clear how many channels were present in the trace. These results suggest that a negative charge at position 224 is important for smooth and large conductance.

FIGURE 2.

Single-channel currents recorded from the E224D, E224C, E224Q, and E224K mutants. Currents were recorded in 100 mM symmetrical [K+] at −140 mV for the E224D, E224C, and E224Q mutants and at −200 mV for the E224K mutant. Currents were sampled at 5 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz. Similar results were obtained in at least another three patches for each mutant.

To further determine whether a negatively charged residue at site 224 is important for a stable main conductance state, we next investigated the effect of a negatively charged MTS reagent, MTSES, on the E224C mutant. It has been shown that the wild-type Kir2.1 channel is sensitive to modifications by MTS reagents. Thus, an MTS-insensitive channel, IRK1J (C54V, C76V, C89I, C101L, C149F, and C169V), was constructed (Lu et al., 1999a). Fig. 3 A shows that MTSES (2 mM) did not have any effect on the IRK1J channel recorded in 300 mM symmetrical [K+] at −100 mV. MTSES relieved the open-channel fluctuations in the E224C mutant and increased the current amplitude (Fig. 3 B). The effects of MTSES could not be reversed by washout (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of MTSES and MTSET on the IRK1J (A and C) and the E224C (B and D) channels. Traces shown in each plot were obtained from the same patch at −100 mV in 300 mM symmetrical [K+]. Currents were sampled at 5 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz. Similar results were obtained in at least four patches in every set of experiments.

It has been previously shown that negatively charged MTS reagents, MTSEA and MTSET, completely inhibit the E224C mutant possibly via physically occluding the internal pore (Lu et al., 1999b). Indeed, the single-channel current of the E224Q mutant is smaller than that of the E224G mutant, suggesting that the size of a neutral residue at site 224 also affects ion permeation. However, MTSES, being similar in size to MTSEA, does not seem to reduce ion conduction. Since the Kir2.1 channel is a cation-selective channel, it is possible that negative charges at site 224 introduced by MTSES could prevent further MTSES accessing to the pore. We next examined whether the treatment of the E224C mutant with MTSES could protect the channel from further interaction with MTSET (2 mM). Fig. 3 B shows that MTSET remained capable of inhibiting the current to ∼50% of the untreated E224C mutant. Also, open-channel fluctuations reappeared after MTSET treatment. On the other hand, if the E224C mutant was first treated with MTSET, the current was almost completely inhibited (Fig. 3 C). MTSES had no effect on the channel pretreated with MTSET (Fig. 3 C). The finding that MTSES could only partially protect the E224C mutant from MTSET modification suggests that it could not modify all four cysteines at site 224 of an E224C mutant. These results suggest that not all four negative charges at site 224 are required to ensure a smooth and large conductance in the Kir2.1 channel.

Vm dependence of single E224G channel

Next we characterized single-channel currents through the E224G mutant at various Vm. Fig. 4 shows the single-channel recordings of the E224G mutant at the indicated Vm and their corresponding M-V histograms. The M-V histograms reveal that the probability of the channel staying at the main state, relative to that in the substate, was higher at more hyperpolarizing Vm. Fig. 5 summarizes the kinetics of the E224G single-channel currents. Hyperpolarization did not have much an effect on dwell times at the short closed state (τCS; Fig. 5 A) or at the main state (τM; Fig. 5 C), yet it decreased dwell times at the long closed state (τCL; Fig. 5 A) and at the substate (τS; Fig. 5 B). Hyperpolarization increased the probability of the main state (pM; Fig. 5 F) but did not affect either the closed probability (pC; Fig. 5 D) or the substate probability (pS; Fig. 5 E). Note that the sum of pC, pS, and pM is <1 because the channel spent significant time during state transitions (arches), which are not grouped in pC, pS, or pM. We estimate averaged conductance as (iO × pO + iS × pS)/Vm (omitting ∼6% of conductance contributed by fast transitions) using the values described in Fig. 5, E–G. Fig. 5 H shows that hyperpolarization favors ion conduction in the E224G mutant.

FIGURE 4.

Vm dependence of M-V histograms. Segments of 30-s recordings at −100 mV (A) and −200 mV (B). M-V histograms with a window of three points are shown in the lower panels.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of Vm on the kinetics of a single E224G channel. (A) Vm dependence of the dwell times for the long closed (CL, ▾) and short closed (CS, ▪) states in the control and for the closed state in 10 μM external [Cs+] (τC (Cs), □). (B and C) Vm dependence of the dwell times for the substate (circles) and main state (triangles) in the control (solid symbols) and in Cs+ (open symbols). (D–F) Effects of Vm on the probabilities of closed state, substate and main state, respectively. Symbols in D, E, and F are the same as those in A, B, and C, respectively. (G) Vm dependence of the absolute values of single-channel currents at the substate and the main state. (H) Averaged conductance versus Vm in the control. n = 3–6.

Cs+ block in the E224G mutant

Cs+ and Rb+ have been shown to induce substates in IK1 channels (Matsuda et al., 1989). The substate of the E224G mutant may be generated by open-channel block by trace amounts of external blocking ions such as Cs+ and Ba2+. We consider block by divalent cations unlikely (see Discussion). However, it is possible that our solutions may contain trace amounts of Cs+ or Rb+. We next compared the single-channel properties of the E224G mutant exposed extracellularly to the control and the Cs+-added solutions.

Fig. 6 shows the single-channel traces of the E224G mutant exposed to external 10 μM [Cs+] at the indicated Vm and their corresponding M-V histograms. The M-V histogram reveals that the probability of the channel staying in the main state relative to that in the substate was about the same at −100 and −140 mV. Cs+ did not affect the current levels of the substate and the main state (Fig. 5 G). Some characteristics of the single-channel current recorded in Cs+ were different from those in the control. First, external Cs+ induced only one single block state (Fig. 5 A) and dramatically increased the closed probability at all Vm tested. Second, although the dwell times for the substate and the open state were similar in the control and the Cs,+ the Vm dependence of the probabilities at the two states was different in these two conditions. The substate probability was more dependent on Vm in the Cs+ than that in the control (Fig. 5 E). At very negative Vm, 10 μM Cs+ decreased the substate probability (Fig. 5 E), which argues against the hypothesis that channel blockers such as Cs+ induces the substate. The main-state probability increased as Vm became more negative in the control but it became independent of Vm in Cs+ (Fig. 5 F). Thus, it seems unlikely that trace amounts of cations in the solution contribute to the formation of the substate.

FIGURE 6.

Single-channel currents recorded in 10 μM external [Cs+]. Traces and M-V histograms recorded at −100 mV (A) and −140 mV (B).

Temperature dependence of single-channel properties

Elevating temperature enhances thermal movement of ions in the solution, thereby increasing permeation. However, diffusion-limited processes such as ion permeation usually is less sensitive to temperature than processes such as protein conformational changes (van Lunteren et al., 1993). We next determined the effects of temperature on single-channel currents (diffusion-limited) and the dwell times at the substate and the main state. Fig. 7 A shows the single-channel currents recorded at −140 mV at the indicated temperature. Fig. 7 B shows the temperature dependence of the inverse of dwell times at the substate and the main state, respectively. The factors by which the inverse of dwell times increased over a 10°C increase (Q10) were ∼1.6 and 1.8 for the substate and the main state, respectively. The Q10 values for the current levels at the substate and the main state were both ∼1.2–1.3 (Fig. 7 C).

FIGURE 7.

Effects of temperature on inverse of dwell times and current amplitudes. (A) Current traces were recorded at −140 mV at the indicated temperature. (B) The inverses of dwell times for substate (•) and the main state (▴) obtained at −140 mV at temperatures ranging from 10 to 23°C. (C) Temperature dependence of the absolute values of single-channel currents at the substate and the main state. Solid lines represent the best fit to the data (in the form of 1/τ = A × exp(−μ/RT), where A and μ are temperature-independent constants, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature). Q10 = exp(10 μ/RT2). n = 3–5.

The Q10 for the dwell time is larger than that for ion permeation (single-channel current), suggesting that mechanisms other than a diffusion-limited process are involved in forming the substate. For example, it is possible that changes of the charge at site 224 may induce conformational changes resulting in fast gating (channel pore constriction) and thus produce a substate (see Discussion).

Effects of [K+] on the single E224G channel

Our experiments suggest that current fluctuations between the substate and the main states are unlikely due to contaminated ion block. However, the results do not rule out the possibility that K+ acts as a permeable blocker (Choe et al., 1998). To explore this possibility, we next studied the effects of various symmetrical [K+] on single E224G currents. Fig. 8 A shows the single-channel recordings of the E224G mutant at the indicated symmetrical [K+] and their corresponding M-V histograms at −140 mV. Open-channel fluctuations were obvious in both conditions. The M-V histogram revealed that the probability of the main state was higher in elevated [K+]. Changes in [K+] had little effect on the dwell times of all states (Fig. 8 B). If K+ were a permeable blocker, the open dwell time should have decreased as [K+] was elevated. Fig. 8 C illustrates the [K+] dependence of probabilities. An increase in [K+] elevated the probability at the main state but decreased the substate probability. The probabilities at the short and long closed states were small and were not affected by varying [K+]. Similar results were obtained at −200 mV (data not shown). Fig. 8 D shows that elevating [K+] increased the single-channel current levels of the substate and the main state. These results suggest that the substate of the E224G mutant is unlikely to be produced by the K+ block. Instead, increasing [K+] favors the E224G mutant staying at the main state, suggesting that K+ binding and/or changes in ion-ion interaction may be involved in the formation of the substate.

FIGURE 8.

Effect of symmetrical [K+] on a single E224G channel. (A) Current traces and corresponding M-V histograms at −140 mV in the indicated [K+]. (B) [K+] dependence of the dwell times at the substate, the short closed, the long closed, and the main states. (C) Effects of [K+] on the state probabilities. (D) [K+] dependence of the absolute values of currents at the substate and the main state. n = 3–6.

Ion dependence of open-channel fluctuations

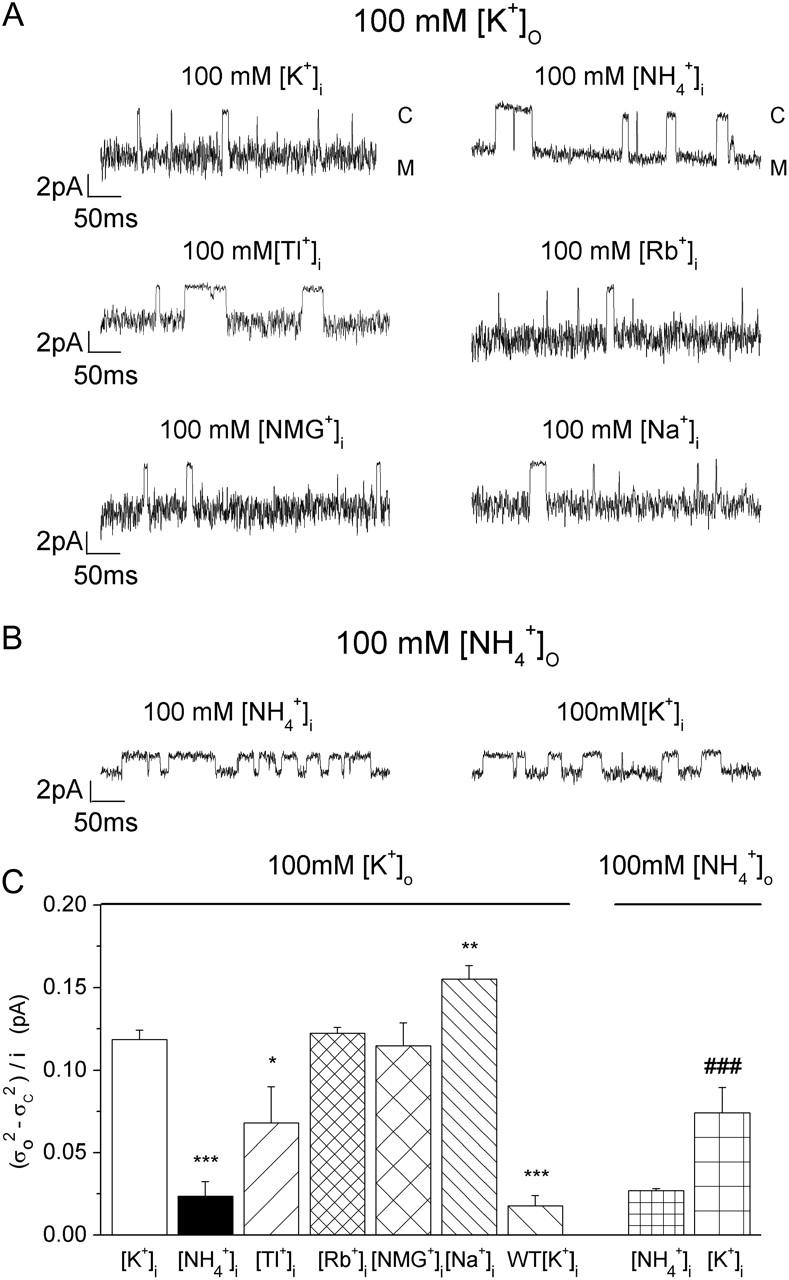

It has been suggested that a substate may result from changes in ion-ion interaction and/or ion gating (Lu et al., 2001). Figs. 5 and 7 show that hyperpolarization and elevating [K+] decreased the substate probability, suggesting that K+ binding and ion-ion interaction may be involved in forming the substate. To investigate whether mutation at residue 224 in the internal vestibule affects internal ion binding and thus ion gating, we next examined the effect of various internal ions on the open-channel fluctuations of inward K+ currents. Fig. 9 A shows the single-channel recordings of the E224G mutant exposed to 100 mM external [K+] and the indicated internal ions at −140 mV. It appears that internal  decreased the open-channel fluctuations. To further determine whether internal K+ and

decreased the open-channel fluctuations. To further determine whether internal K+ and  interact with the channel differently, we next examined the single-channel inward

interact with the channel differently, we next examined the single-channel inward  current through the E224G mutant exposed to 100 mM internal

current through the E224G mutant exposed to 100 mM internal  and [K+], respectively (Fig. 9 B). To compare open-channel fluctuations, we calculated normalized open-state variance

and [K+], respectively (Fig. 9 B). To compare open-channel fluctuations, we calculated normalized open-state variance  in the same sweep. Fig. 9 C illustrates the normalized open-channel variance of the wild-type channel and the E224G mutant exposed to the indicated external and internal ions. In 100 mM external [K+], the open-channel fluctuations of the E224G mutant significantly decreased in internal

in the same sweep. Fig. 9 C illustrates the normalized open-channel variance of the wild-type channel and the E224G mutant exposed to the indicated external and internal ions. In 100 mM external [K+], the open-channel fluctuations of the E224G mutant significantly decreased in internal  and Tl+ and increased in internal Na+ in comparison with those in internal K+. Also, in 100 mM symmetrical [K+], the normalized variance in the wild-type channel is significantly lower than the E224G mutant. In the presence of 100 mM external

and Tl+ and increased in internal Na+ in comparison with those in internal K+. Also, in 100 mM symmetrical [K+], the normalized variance in the wild-type channel is significantly lower than the E224G mutant. In the presence of 100 mM external  the open-channel noise in the E224G mutant exposed to internal

the open-channel noise in the E224G mutant exposed to internal  was slightly but significantly smaller than that in K+. These results together suggest that the interaction of ions with the internal vestibule of the E224G mutant plays a role in the formation of the substate.

was slightly but significantly smaller than that in K+. These results together suggest that the interaction of ions with the internal vestibule of the E224G mutant plays a role in the formation of the substate.

FIGURE 9.

Ion dependence of open-channel fluctuations. (A) Traces recorded at −140 mV in 100 mM external [K+] and the indicated internal ions. The traces recorded in 100 mM internal [K+] and  were obtained from the same patch. Currents were sampled at 5 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz. (B) Traces recorded at −140 mV in 100 mM external

were obtained from the same patch. Currents were sampled at 5 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz. (B) Traces recorded at −140 mV in 100 mM external  and the indicated internal ions. The traces were obtained from the same patch. (C) The normalized open-state variance in the presence of various internal ions. n = 3–11. (*) p < 0.05, (**) p < 0.01, and (***) p < 0.005 as compared to 100 mM internal [K+] in the external K+ group. (###) p < 0.005 in the external

and the indicated internal ions. The traces were obtained from the same patch. (C) The normalized open-state variance in the presence of various internal ions. n = 3–11. (*) p < 0.05, (**) p < 0.01, and (***) p < 0.005 as compared to 100 mM internal [K+] in the external K+ group. (###) p < 0.005 in the external  group.

group.

DISCUSSION

A substate occurs frequently and contributes to open-channel fluctuations in the E224G mutant

The glutamate at position 224 in the Kir2.1 channel has been shown to be an important site involved in inward rectification (Yang et al., 1995). It is also suggested that E224 plays a critical role in ion permeation. The E224G mutant is less sensitive to internal Mg2+ and polyamines block, and its single-channel conductance is reduced and shows open-channel fluctuations (Yang et al., 1995; Kubo and Murata, 2001). Surface charge effect at site 224 has been shown to be involved in conductance (Xie et al., 2002), but the mechanisms for open-channel fluctuations remain unknown. In this study, we show that in addition to the E224G mutant, E224C, E224K, and E224Q mutants also demonstrate open-channel fluctuations at hyperpolarizing voltages. On the other hand, the single-channel recordings of the E224D mutant are similar to those in the wild-type channel. Using an analysis based on constructing M-V histograms, we identify at least one substate in the E224G mutant. The rapid open-channel fluctuations are mainly attributed to fast transitions between the substate and the main state. It is likely that more substates exist in the E224G mutant, but their dwell times are too short to be resolved. Rapid switching between the closed and the main states may produce an artificially reduced conducting substate. However, we consider this unlikely in the E224G mutant because the dwell times are longer than the resolution limit of the M-V histogram method (0.1 ms in this study). Also, the dwell time of the substate responds to changes in temperature and Vm.

Substates have been observed in the cardiac inward rectifier IK1 channel (Sakmann and Trube, 1984; Matsuda, 1988) and the wild-type Kir2.1 channel (Lu et al., 2001), although they occur much less frequently than the substate does in the E224G mutant. It is possible that the mechanisms underlying the formation of substates are similar for the wild-type and the E224G mutant. The neutralization of the negative charge at residue 224 promotes the channel entering the substate. On the other hand, a negative charge at residue 224 seems to be critical in ensuring smooth and high ion conductance. With either a glutamate or an aspartate residue at site 224, the single-channel conductance is smooth and large. Furthermore, in the E224C mutant, the negatively charged MTS reagent, MTSES, irreversibly relieves the open-channel fluctuations. MTSES could only partially protect the E224C mutant from MTSET modification, suggesting that the effect of MTSES is specific to the cysteine mutation at site 224 and that not all four negative charges at site 224 are required to ensure a smooth and large conductance in the Kir2.1 channel. It has been shown that each MTSET or MTSEA interacting with the cysteine located at site 224 of a Kir2.1 subunit inhibits 25% of current conductance (Lu et al., 1999b). However, the partial modification of the E224C mutant by MTSES does not reduce conductance. We suggest that the electrostatic effect may dominate over the steric effect of the MTSES bound to the partially modified E224C mutant. As discussed below, the negative charge may be involved in ion gating that affects ion conductance. Lu et al. (1999b) have shown that the internal pore near site 224 is large enough to accommodate four MTSET (>20 Å). As long as the internal pore mouth remains big enough for K+ flow (partial block of a 20 Å pore), the gating instead of the internal pore aperture will be more likely a rate-limiting step in ion conduction. On the other hand, in the absence of internal ion gating, the conductance will be very low (see below, Fig. 10). Reducing the size of the internal pore will further constrain ion flow (cf. the E224G and E224Q mutants). Also, the conductance can be greatly reduced by replacing a lysine at site 224 (Fig. 2, the E224K mutant), suggesting that the inhibitory effect of MTSET on the E224C mutant may be both electrostatic and steric. Note that the reduced conductance in the E224K mutant cannot simply be explained by the size of a side chain because the conductance of the wild-type and the E224D mutant are the same and the pore is >20 Å.

FIGURE 10.

Schematic model for open-channel fluctuations. The upper panel of each plot shows ion gating at the internal vestibule and ion occupancy in the selectivity filter with specified configuration of K+ ions (•) and water (○). The lower panel illustrates hypothetical energy levels for (1, 3) and (2, 4) configurations in various ion-gating conditions.

Possible mechanisms underlying the formation of the substate in E224G mutant

Exactly how the charge at residue 224 is involved in open-channel fluctuations remains to be explored. A substate may arise from channel block by ions in the solutions. By conducting experiments, we rule out the possibility that the open-channel fluctuations are due to the block by HEPES, PIP2, or Cs+. Also, we consider Mg2+ and Ba2+ block to be unlikely because our solution contained 5 mM EDTA to chelate divalent cations. The block induced by polyamines also can be ruled out since the experiments were carried out in inside-out patches perfused with solutions free of polyamines. Fig. 8 shows that K+ does not act as a permeable blocker. Also, substituting internal K+ with  or Tl+ (Fig. 9) relieves open-channel fluctuations, further arguing against the channel block hypothesis.

or Tl+ (Fig. 9) relieves open-channel fluctuations, further arguing against the channel block hypothesis.

Conformational changes inducing fast gating may be involved in generating a substate. Two regions in the Kir family are important in regulating gating (Loussouarn et al., 2002). It has been shown that mutations in the selectivity filter of a Kir6.2 channel modify its burst kinetics (Proks et al., 2001). Also the single-channel kinetics change and the occurring frequency at substates increases in backbone mutations at residues 144 and 146 located in the selectivity filter of the Kir2.1 channel (Lu et al., 2001). A slow gate is localized at the internal pore region. It is proposed that the slow gate may be due to a constriction of a bundle crossing caused by the movement of the second transmembrane domain in Kir 6.x and Kir3.x channels (Loussouarn et al., 2000; Enkvetchakul et al., 2000; Loussouarn et al., 2001; Sadja et al., 2001; Yi et al., 2001) in a way similar to Kv1 channels (del Camino and Yellen, 2001). The changes of charges at site 224 may allosterically influence one or both of these two gating regions and thus induce fast transitions of the substate and the main state.

How would the change at the internal vestibule alter the fast gating in the selectivity filter? It has been proposed that the fast gating in the mutations located in the selectivity filter of the Kir2.1 channel may be due to changes of ion-gating in coupling to ion-ion interaction (Lu et al., 2001). Also, we showed that increases in [K+] and hyperpolarization enhance the main-state probability, suggesting that K+ binding and changes in ion-ion interaction may be involved in forming a substate. The ion dependence of open-channel fluctuations further supports that ion gating in the internal vestibule and ion-ion interaction in the pore play a role in the substate formation. We propose a model to explain how ion gating and ion-ion interaction work together to form a substate. It has been previously shown that there are four K+ binding sites in the selectivity filter of a KcsA channel (Morais-Cabral et al., 2001). Furthermore, in a high-conducting state, two K+ ions in the selectivity filter move in a concerted manner between two configurations of similar energy levels: one K+-water-K+-water configuration, where ions bind at positions 1 and 3 ((1, 3) configuration) and the other water-K+-water-K+ configuration where ions binds at positions 2 and 4 ((2, 4) configuration). Any factor that generates energy difference between the two configurations will result in slow ion conduction. To illustrate how a Kir2.1 channel shows open-channel fluctuations, we propose that the Kir2.1 channel possesses similar K+ binding sites in the selectivity filter (Fig. 10). Furthermore, we hypothesize that the ion gating in the internal vestibule affects K+ permeation in the following ways. In the presence of K+ binding to the internal pore, the internal pore (e.g., the crossing bundle) is open such that both (1, 3) and (2, 4) configurations have similar energy levels and thus the conductance is high (Fig. 10 A). On the other hand, in the absence of an ion binding in the internal site, the internal pore entry is narrow and the energy levels of the two configurations are much different, and thus K+ ions conduct in a low speed (Fig. 10 B). In the wild-type channel, the K+-gating functions most of the time. Therefore, the conductance is high and smooth. The neutralization of the charge at site 224 decreases the probability and stability of K+ occupancy at the internal site and thus reduces K+ gating. As a result, the E224G mutant rapidly fluctuates between two conformational states of different conductance (Fig. 10, A and B). When the internal pore is gated by  the balance of the energy levels of the (1, 3) and (2, 4) configurations are slightly disturbed such that the channel now conducts in a medium rate (Fig. 10 C). This is supported by the fact that the single-channel current is smaller in 100 mM internal

the balance of the energy levels of the (1, 3) and (2, 4) configurations are slightly disturbed such that the channel now conducts in a medium rate (Fig. 10 C). This is supported by the fact that the single-channel current is smaller in 100 mM internal  than in [K+] even though the driving force is larger in

than in [K+] even though the driving force is larger in  (Fig. 9 A). In 100 mM internal

(Fig. 9 A). In 100 mM internal  the E224G mutant rapidly oscillates between the medium and low conductance conformations (Fig. 10, C and B). Since the conductance of the two states does not differ very much, the appearing open-channel fluctuations are smaller than those in 100 mM internal [K+].

the E224G mutant rapidly oscillates between the medium and low conductance conformations (Fig. 10, C and B). Since the conductance of the two states does not differ very much, the appearing open-channel fluctuations are smaller than those in 100 mM internal [K+].

Fig. 10 presents a simplified model. The mechanisms for the appearance of substates may be more complicated. Substates can be produced from channels that rapidly fluctuate on the timescale of ion permeation between two conformational states differing only in localized structures (Dani and Fox, 1991). The equilibrium distributions of the channel between the two conformations determine the conductance. A change in the relative probability of and/or the rate of fluctuations between the two conformations may produce another conductance (substate). Furthermore, the changes of the electrostatic properties at the internal vestibule may result in a different fraction of the electrical field lines being confined to the aqueous pore, thereby producing substates (Dani and Fox, 1991; Xie et al., 2002). Site 224 may be one of the factors influencing the ion binding instead of being the exact ion-binding site at the internal vestibule, because the neutralization of residue 299 also produces open-channel fluctuations (Kubo and Murata, 2001).

To explain why fluctuations are smaller with inward  currents (Fig. 9 B), we further propose that

currents (Fig. 9 B), we further propose that  interacts with the narrow pore differently from K+ such that

interacts with the narrow pore differently from K+ such that  conductance was less sensitive to changes in internal ion gating in response to the neutralization at residue 224. This is supported by our previous finding that

conductance was less sensitive to changes in internal ion gating in response to the neutralization at residue 224. This is supported by our previous finding that  but not K+ occupancy in the pore results in channel inactivation (Shieh and Lee, 2001), indicating that ion-ion and ion-channel interactions in the pore in

but not K+ occupancy in the pore results in channel inactivation (Shieh and Lee, 2001), indicating that ion-ion and ion-channel interactions in the pore in  are different from those in K+.

are different from those in K+.

CONCLUSION

Ion channels are characterized by a main conductance state. However, many channels also display substates. Regulation of these substates may be of functional significance to cells. The study of substates may also provide insights into channel structure and permeation processes. In this study, we have shown that the negative-charged residue at residue 224 located at the internal pore mouth is very important in ensuring a “smooth” and high K+ influx through the Kir2.1 channel. Thus, not only the external ion binding sites are important for K+ permeation (Shieh et al., 1999), the internal site also plays a critical role. Also, the binding of a permeant ion to the internal pore “gates” the channel into distinct conducting states possibly through conformational changes or by changing ion-ion interaction in the selectivity filter. It remains unclear how many substates exist in the E224G mutant. Also, further investigations are required to understand how permeant ions interact with each other and with the channel to produce substates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Lily Jan and Jian Yang for kindly providing the Kir2.1 and IRK1J clone, respectively. We are grateful to Dr. Diego Restrepo for sharing the “Levels” program.

This work was supported by Academia Sinica and by the National Science Council of Taiwan, Republic of China, under grant 92-2320-B-001-021.

References

- Alagem, N., M. Dvir, and E. Reuveny. 2001. Mechanism of Ba2+ block of a mouse inwardly rectifying K+ channel: differential contribution by two discrete residues. J. Physiol. 534:381–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brelidze, T. I., X. Niu, and K. L. Magleby. 2003. A ring of eight conserved negatively charged amino acids doubles the conductance of BK channels and prevents inward rectification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:9017–9022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe, H., H. Sackin, and L. G. Palmer. 1998. Permeation and gating of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel. Evidence for a variable energy well. J. Gen. Physiol. 112:433–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani, J. A., and J. A. Fox. 1991. Examination of subconductance levels arising from a single ion channel. J. Theor. Biol. 153:401–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Camino, D., and G. Yellen. 2001. Tight steric closure at the intracellular activation gate of a voltage-gated K+ channel. Neuron. 32:649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enkvetchakul, D., G. Loussouarn, E. Makhina, S. L. Shyng, and C. G. Nichols. 2000. The kinetic and physical basis of K(ATP) channel gating: toward a unified molecular understanding. Biophys. J. 78:2334–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficker, E., M. Taglialatela, B. A. Wible, C. M. Henley, and A. M. Brown. 1994. Spermine and spermidine as gating molecules for inward rectifier K+ channels. Science. 266:1068–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D., and Z. Lu. 2002. IRK1 inward rectifier K+ channels exhibit no intrinsic rectification. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:539–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill, O. P., A. Marty, E. Heher, B. Sakmann, and F. J. Sigworth. 1981. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 391:85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann, D. W. 1995. The giant membrane patch. In Single-Channel Recording. B. Sakmann and E . Neher, editors. Plenum Press, New York. 307–328.

- Huang, C. L., S. Feng, and D. W. Hilgemann. 1998. Direct activation of inward rectifier potassium channels by PIP2 and its stabilization by Gbetagamma. Nature. 391:803–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imoto, K., C. Busch, B. Sakmann, M. Mishina, T. Konno, J. Nakai, H. Bujo, Y. Mori, K. Fukuda, and S. Numa. 1988. Rings of negatively charged amino acids determine the acetylcholine receptor channel conductance. Nature. 335:645–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo, Y., T. Baldwin, Y. Jan, and L. Jan. 1993. Primary structure and functional expression of a mouse inward rectifier potassium channel. Nature. 362:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo, Y., and Y. Murata. 2001. Control of rectification and permeation by two distinct sites after the second transmembrane region in Kir2.1 K+ channel. J. Physiol. 531:645–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lischka, F. W., M. M. Zviman, J. H. Teeter, and D. Restrepo. 1999. Characterization of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate-gated channels in the plasma membrane of rat olfactory neurons. Biophys. J. 76:1410–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopatin, A., E. Makhina, and C. Nichols. 1994. Potassium channel block by cytoplasmic polyamines as the mechanism of intrinsic rectification. Nature. 372:366–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loussouarn, G., E. N. Makhina, T. Rose, and C. G. Nichols. 2000. Structure and dynamics of the pore of inwardly rectifying K(ATP) channels. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1137–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loussouarn, G., L. R. Phillips, R. Masia, T. Rose, and C. G. Nichols. 2001. Flexibility of the Kir6.2 inward rectifier K+ channel pore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:4227–4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loussouarn, G., T. Rose, and C. G. Nichols. 2002. Structural basis of inward rectifying potassium channel gating. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 12:253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T., B. Nguyen, X. Zhang, and J. Yang. 1999a. Architecture of a K+ channel inner pore revealed by stoichiometric covalent modification. Neuron. 22:571–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T., A. Y. Ting, J. Mainland, L. Y. Jan, P. G. Schultz, and J. Yang. 2001. Probing ion permeation and gating in a K+ channel with backbone mutations in the selectivity filter. Nat. Neurosci. 4:239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T., Y. G. Zhu, and J. Yang. 1999b. Cytoplasmic amino and carboxyl domains form a wide intracellular vestibule in an inwardly rectifying potassium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:9926–9931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z., and R. MacKinnon. 1994. Electrostatic tuning of Mg2+ affinity in an inward- rectifier K+ channel. Nature. 371:243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, R., R. Latorre, and C. Miller. 1989. Role of surface electrostatics in the operation of a high- conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Biochemistry. 28:8092–8099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, H. 1988. Open-state substructure of inwardly rectifying potassium channels revealed by magnesium block in guinea-pig heart cells. J. Physiol. 397:237–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, H., H. Matsuura, and A. Noma. 1989. Triple-barrel structure of inwardly rectifying K+ channels revealed by Cs+ and Rb+ block in guinea-pig heart cells. J. Physiol. 413:139–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, H., A. Saigusa, and H. Irisawa. 1987. Ohmic conductance through the inwardly rectifying K channel and blocking by internal Mg2+. Nature. 325:156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais-Cabral, J. H., Y. Zhou, and R. MacKinnon. 2001. Energetic optimization of ion conduction rate by the K+ selectivity filter. Nature. 414:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimigean, C. M., J. S. Chappie, and C. Miller. 2003. Electrostatic tuning of ion conductance in potassium channels. Biochemistry. 42:9263–9268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patlak, J. B. 1993. Measuring kinetics of complex single ion channel data using mean-variance histograms. Biophys. J. 65:29–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proks, P., C. E. Capener, P. Jones, and F. M. Ashcroft. 2001. Mutations within the P-loop of Kir6.2 modulate the intraburst kinetics of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 118:341–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadja, R., K. Smadja, N. Alagem, and E. Reuveny. 2001. Coupling Gbetagamma-dependent activation to channel opening via pore elements in inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Neuron. 29:669–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabirov, R. Z., T. Tominaga, A. Miwa, Y. Okada, and S. Oiki. 1997. A conserved arginine residue in the pore region of an inward rectifier K channel (IRK1) as an external barrier for cationic blockers. J. Gen. Physiol. 110:665–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakmann, B., and G. Trube. 1984. Conductance properties of single inwardly rectifying potassium channels in ventricular cells from guinea-pig heart. J. Physiol. 347:641–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh, R. C., J. C. Chang, and C. C. Kuo. 1999. K+ binding sites and interactions between permeating K+ ions at the external pore mouth of an inward rectifier K+ channel (Kir2.1). J. Biol. Chem. 274:17424–17430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh, R. C., and Y. L. Lee. 2001. Ammonium ions induce inactivation of Kir2.1 potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 535:359–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanfield, P., N. Davies, P. Shelton, M. Sutcliffe, I. Khan, W. Brammar, and E. Conley. 1994. A single aspartate residue is involved in both intrinsic gating and blockage by Mg2+ of the inward rectifier, IRK1. J. Physiol. 478:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lunteren, E., K. S. Elmslie, and S. W. Jones. 1993. Effects of temperature on calcium current of bullfrog sympathetic neurons. J. Physiol. 466:81–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, C. 1987. Inward rectification of a potassium channel in cardiac ventricular cells depends of internal magnesium ions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:2560–2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L. H., S. A. John, and J. N. Weiss. 2002. Spermine block of the strong inward rectifier potassium channel Kir2.1: dual roles of surface charge screening and pore block. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:53–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J., Y. N. Jan, and L. Y. Jan. 1995. Control of rectification and permeation by residues in two distinct domains in an inward rectifier K+ channel. Neuron. 14:1047–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi, B. A., Y. F. Lin, Y. N. Jan, and L. Y. Jan. 2001. Yeast screen for constitutively active mutant G protein-activated potassium channels. Neuron. 29:657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]