Abstract

A primary and critical step in platelet attachment to injured vascular endothelium is the formation of reversible tether bonds between the platelet glycoprotein receptor Ibα and the A1 domain of surface-bound von Willebrand factor (vWF). Due to the platelet's unique ellipsoidal shape, the force mechanics involved in its tether bond formation differs significantly from that of leukocytes and other spherical cells. We have investigated the mechanics of platelet tethering to surface-immobilized vWF-A1 under hydrodynamic shear flow. A computer algorithm was used to analyze digitized images recorded during flow-chamber experiments and track the microscale motions of platelets before, during, and after contact with the surface. An analytical two-dimensional model was developed to calculate the motion of a tethered platelet on a reactive surface in linear shear flow. Through comparison of the theoretical solution with experimental observations, we show that attachment of platelets occurs only in orientations that are predicted to result in compression along the length of the platelet and therefore on the bond being formed. These results suggest that hydrodynamic compressive forces may play an important role in initiating tether bond formation.

INTRODUCTION

Platelet adhesion dynamics is of central importance in hemostasis and thrombosis. During these biological processes, circulating platelets are recruited from the blood stream to sites of vascular injury, an event dependent on two key platelet glycoprotein (GP) receptors: GPIbα (subunit of the GPIb-IX-V complex) and GPIIb-IIIa (αIIbβIII integrin) (Lopez and Dong, 1997; Ruggeri, 1997; Du and Ginsberg, 1997). One key ligand that supports platelet adhesion by interacting with both of these receptors is von Willebrand factor (vWF), a multimeric plasma glycoprotein that is deposited on the exposed subendothelium region of the damaged vessel (Sakariassen et al., 1979; Turitto et al., 1980; Coller et al., 1983). In regard to GPIbα-mediated adhesion, it is the A1 region of this multidomain molecule that is critical for supporting the initial attachment (tethering) and subsequent translocation of platelets in flow (Savage et al., 1996; Cruz et al., 2000). This interaction also stimulates activation of the platelet GPIIb-IIIa receptor, which is necessary for firm irreversible adhesion and platelet aggregation (Savage et al., 1996; Parise, 1999; Kasirer-Friede et al., 2004).

Experiments have been conducted by a number of research groups to determine the effects of shear stress on platelet adhesion and the complementary roles of various platelet receptors (GPIbα and GPIIb-IIIa) and their ligands (vWF, fibrinogen, vitronectin, fibronectin) in promoting normal and pathological thrombus formation (Turitto et al., 1980; Weiss et al., 1989; Ikeda et al., 1991; Savage et al., 1992, 1996; Alevriadou et al., 1993; Kroll et al., 1996; Grunemeier et al., 2000). In shear flow, platelets were observed to transiently tether as well as translocate on the injured vessel surface via GPIbα-vWF tether bonds before firm adhesion, an interaction reminiscent of selectin-mediated rolling of leukocytes on inflamed endothelium (Springer, 1994; Savage et al., 1996; Cruz et al., 2000). Interestingly, Doggett et al. (2002, 2003) investigated the kinetics of the GPIbα-vWF-A1 tether bond and demonstrated that it exhibits similar biophysical attributes as the selectins; these include fast association and dissociation rates, force-dependent kinetics, and the requirement of a critical level of shear flow for adhesion to occur. This work has recently been confirmed by Kumar et al. (2003). In contrast to leukocytes, however, tethered platelets do not roll, but instead exhibit a flipping motion in the direction of flow due to their flattened ellipsoidal shape. Thus, distinct mechanics imposed by the differences in the shapes of platelets versus leukocytes must govern tethering of these cell types in a flow environment even though they possess similar kinetic attributes.

In the current study, we sought to further explore and define the mechanics of platelet-surface contact by studying interactions between GPIbα and the vWF-A1 domain under varying hydrodynamic shear stress conditions. Unlike previous platelet experiments that have primarily involved bulk measurements of platelets interacting with a surface to determine the total number of adhering platelets (Savage et al., 1996; Cruz et al., 2000; Grunemeier et al., 2000), our work focused on examining the microscale motions of individual platelets during their transient interactions with vWF-A1. Images of platelet motion over vWF-A1-coated surfaces were captured during flow chamber experiments, for a range of fluid shear stresses (0.2–8.0 dyn/cm2). We used a platelet image processing algorithm developed in MATLAB to determine, from the digitized images, platelet three-dimensional orientation with respect to the surface as a function of time.

Since theoretical models have been successfully developed to aid in our understanding of primary and secondary leukocyte recruitment at sites of inflammation (Hammer and Apte, 1992; King and Hammer, 2001a,b), we anticipated that a suitable model for platelet mechanics would prove useful in providing physical insight into the platelet recruitment process. To this end, we developed an analytical model from first principles to characterize the flipping motion of a tethered platelet on an adhesive surface under linear shear flow and then compared predicted platelet trajectories with those obtained from flow chamber experiments. The hydrodynamic forces acting on the tethered platelet for various orientations during its flipping motion on the surface were also obtained from the model. Finally, the instantaneous orientation of platelets with respect to the surface at the time of surface capture and release were recorded and compared to the theory. We found a consistent correlation between the nature of the hydrodynamic force acting on the platelet and the angular orientation of the platelet at the time of attachment to or detachment from the surface. The results obtained may have important implications on the role of compressive hydrodynamic forces in enabling platelet adhesion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experiments

Platelet tethering experiments were carried out in a parallel-plate flow chamber apparatus at a range of fluid shear stresses as previously described (Cruz et al., 2000; Doggett et al., 2002). Briefly, platelets were purified from citrated whole blood (5 × 107 per ml) and perfused over plasma vWF (20 μg/ml) at fluid shear stresses ranging from 0.2 to 8 dyn/cm2. Images of platelets flowing over, attaching to, flipping on, and detaching from vWF-A1-coated surfaces were captured at 120 fps (235 fps in one set) using a Nikon microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 20× objective and high speed video camera (Speed Vision Technologies, San Diego, CA), and converted to digital movies. The total magnification corresponded to 7.57 pixels per micron.

Cell tracking methodology

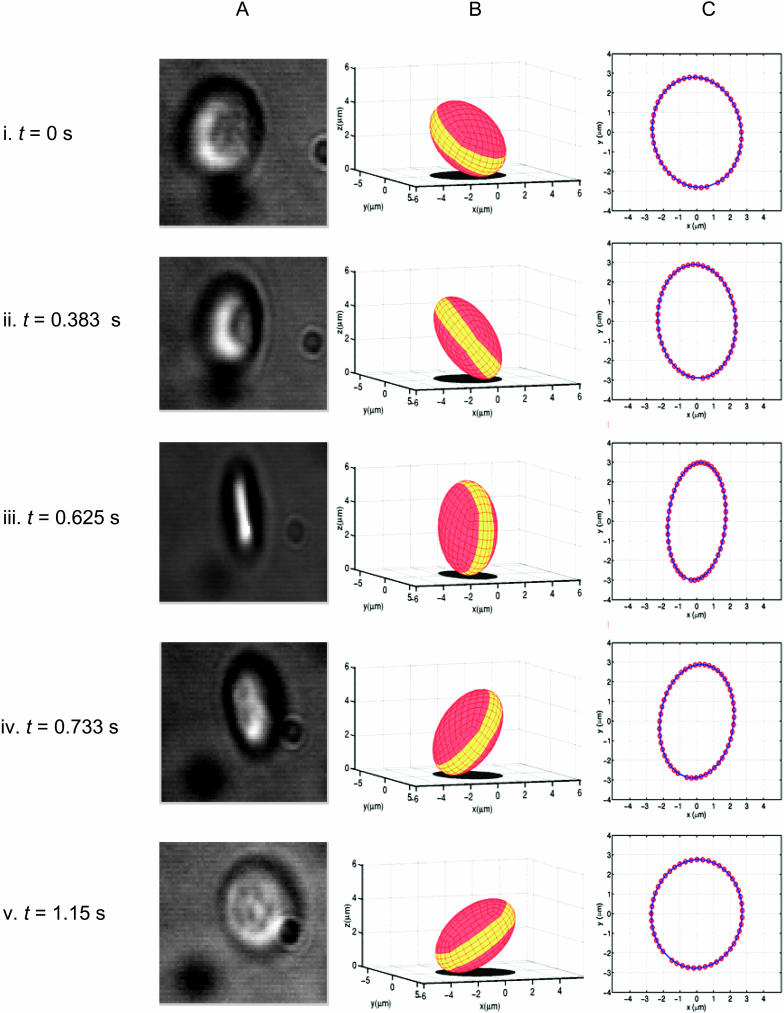

For the purposes of cell tracking, the platelet was modeled as a rigid ellipsoid. The MATLAB image processing program first analyzed the entire sequence of digital grayscale images captured from phase contrast microscopic images of platelets to determine the dimensions of each cell. Each digital movie studied contained most of the range of possible platelet orientations; thus the major and minor platelet axes could be readily identified. To calculate the three-dimensional platelet orientation for a particular frame, an initial orientation was assumed based on the most recent platelet position, and its elliptical two-dimensional projection on the x,y plane was compared with the actual platelet projection. The simplex method for minimization of the sum of errors (distance between complementary points on the experimental platelet projection and the predicted projection) was used to determine, in proximity of the initial assumed position, the true platelet orientation. Note that the platelet can be tracked with high fidelity during the entire interaction using this technique. Fig. 1 illustrates graphically the algorithm's tracking results of one platelet flipping event. We have made this program available to others for use in tracking the motion of ellipsoidal particles (contact M.R.K.).

FIGURE 1.

Graphical results of the platelet tracking algorithm developed to analyze three-dimensional position of tethering platelets from digital movies. (A) Digital movie frames of a tethered platelet flipping on a vWF-coated surface showing platelet orientation at five different times (i–v) during the flip. (B) Corresponding diagrams of ellipsoidal mesh models rotated approximately three axes and its calculated two-dimensional projected shadow. (C) Regression of calculated shadow outline (represented by thick solid line) to experimental image outline (represented by ○).

Analytical platelet flipping model

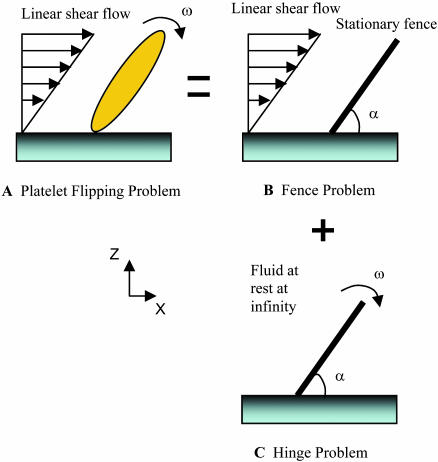

The platelet was modeled as a thin plate, hinged at one end and extending infinitely in the direction perpendicular to the flow and velocity gradient directions. We assumed in our model that the platelet-surface bond(s) provides no resistance to rotation and behaves as a frictionless hinge. The flow near the surface was approximated as linear shear flow. Because of the microscopic dimensions of this fluid system (Reynolds number Re = ρL2γ/μ ≪ 1, where ρ is the fluid density, L is the characteristic length, γ is the shear rate, and μ is the fluid viscosity) the flow near the wall is within the Stokes regime and inertial effects can be neglected. Taking advantage of the linearity of the Stokes flow equations,  where v is the fluid velocity and p is the fluid pressure, the hydrodynamic problem of platelet flipping can be decomposed into the sum of two simpler problems (Fig. 2):

where v is the fluid velocity and p is the fluid pressure, the hydrodynamic problem of platelet flipping can be decomposed into the sum of two simpler problems (Fig. 2):

Fence problem. Linear shear flow around a stationary fence inclined at angle α to an infinite rigid wall. The governing boundary conditions for this flow are v = 0 at θ = 0, π and v = 0 at θ = α for 0 ≤ r ≤ 1, and v → γ zî as r → ∞, where α is the angle made by the fence with the plane and is measured in counterclockwise direction, γ is the shear rate, and î is a unit vector in the x direction.

Hinge problem. Flow due to rotation at angular velocity ω of a hinged plate oriented at angle α to a planar surface. The surrounding fluid is motionless at infinity. Edge effects due to the finite extent of the platelet were neglected. The analysis was done in two parts with flow fields for fluid regions on either side of the plate determined separately. The boundary conditions consist of the no-slip and no-penetration conditions at the solid surfaces of θ = 0, π, α.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic of how the Stokes flow problem of a platelet flipping on a surface may be modeled as a two-dimensional analytical problem by decomposing it into the sum of two simpler cases. Flipping is a result of the hydrodynamic effect of shear flow on the platelet as it interacts with surface-bound vWF. (A) Platelet attached to the surface by GPIbα-vWF bond(s) and subjected to linear shear flow. (B) A stationary and rigid inclined fence subjected to linear shear flow. (C) A rigid, flat, hinged plate rotating at angular velocity ω toward the surface in a quiescent fluid.

A solution to the fence problem has been previously determined by Jeong and Kim (1983). They derived analytical expressions for force and torque exerted on the fence by the fluid, for all orientations of the fence with respect to the wall (Appendix 1). For the hinge problem, the necessary expressions for velocity profiles, force, and torque were derived, and are discussed in Appendix 2.

RESULTS

Flipping of tethered platelets

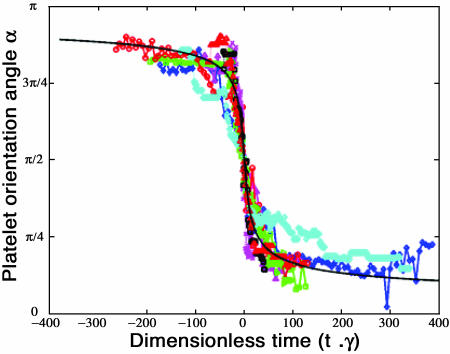

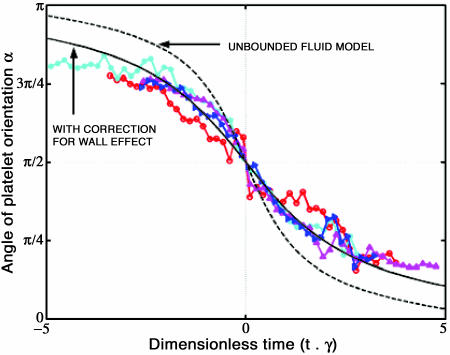

A platelet tethering event was defined as the occurrence of a platelet binding to the surface such that the anchorage point did not move while the platelet flipped about this point. After completing one flip in the direction of flow, platelets were observed to either dissociate after some finite time, or undergo a second flip at a new anchorage point. The platelet flipping events that were analyzed lasted between 0.35 and 4 s. This is significantly longer than the largest value of characteristic time for force loading of the bond, which can be calculated as 1/(minimum shear rate) = 1/100 = 0.01 s. This is the average time taken for a (spherical) cell to move a distance equal to its radius in the direction of flow resulting in maximum stressing of the bond. In the experimental characterization, platelets that did not exhibit significant rotation about the x axis were selected for study, i.e., complex, fully three-dimensional trajectories were not analyzed. Seven out of 39 observed flipping events exhibited three-dimensional motion. These so-called three-dimensional trajectories involved either diagonal flipping with a velocity component normal to the flow direction or significant bending of the platelet. Platelets rolling on their edges were not observed. Nine representative flipping trajectories, spanning wall shear stresses ranging from 1.0 to 8.0 dyn/cm2, were chosen for comparison with the theoretical prediction. Fig. 3 compares the experimentally observed platelet flipping trajectories with that predicted by the two-dimensional analytical model. Importantly, the motion of the platelets was in good agreement with the predicted trajectories over a wide range of shear stresses (1–8 dyn/cm2). It is evident from Fig. 3 that when time is non-dimensionalized with respect to wall shear rate, the experimental platelet trajectories obtained for a range of shear stresses all collapse onto a single curve (within experimental error) as expected from the model.

FIGURE 3.

Plot of analytically predicted and experimentally observed trajectories of bound platelets during platelet flips as a function of the dimensionless time. At time t = 0, the platelet is oriented at 90° to the surface. (Thick solid line represents the theoretical prediction; the symbols ⋄, △, □, and ○ represent four experimental flipping events at 8 dyn/cm2; the symbols ▹, ⋄, △, and □ represent four experimental flipping events at 1.5 dyn/cm2; x represents a flipping event at 1 dyn/cm2.)

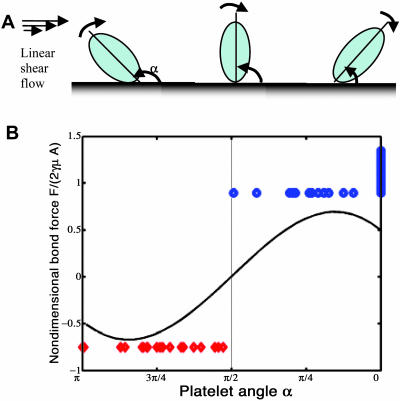

Radial bond force prediction

Our theoretical analysis also provides information on the magnitude and direction of force acting on the platelet, and thus yields an estimate of the hydrodynamic radial force experienced by the tethered platelet as a function of its orientation with respect to the surface. Making the assumption that the receptor-ligand bond(s) is oriented in the direction of the major axis of the platelet, one can thus calculate the radial force on the bond (see Discussion for motivation for this assumption). Fig. 4 B shows the magnitude and direction of non-dimensionalized radial force acting on the platelet-surface bond during the period of the flipping event. The theory predicts that the radial force on the bond changes sign during the platelet flip. The force on the bond is calculated to be compressive over the first half of the flip and tensile over the second half. Tees et al. (1993) demonstrated in their investigations of dissociation of sphere doublets under shear stress, that the doublet undergoes alternating tensile and compressive forces during its periodic rotation in the fluid. During one quarter of the complete orbit of the doublet (prolate spheroid) long axis, the doublet experiences compressive force which promote surface contact and bond formation (Neelamegham et al., 1997), and during the next quarter of the orbit, tensile forces dominate promoting bond dissociation. To estimate the magnitudes of compressive and tensile radial force on a platelet from the model, we assume a platelet size of 3 μm × 3 μm square and a fluid viscosity of 1.0 cP. The maximum absolute value of radial force on the bond is calculated as 0.93 pN and 10.2 pN at a shear rate of 73 s−1 and 800 s−1, respectively. Note that Doggett et al. (2002) showed a minimum shear threshold for tether bond formation at 73 s−1.

FIGURE 4.

Plot of non-dimensionalized theoretical hydrodynamic radial bond force as a function of decreasing platelet orientation angle, compared with experimentally observed platelet attachment/detachment angles. (A) Schematic diagrams of three positions of a platelet during its flip, where α is the angle the platelet major axis makes with the surface, measured in counterclockwise direction. (B) Non-dimensionalized theoretical radial bond force, F/(2γμA), plotted as a function of platelet orientation angle where the angles vary from π to 0 as the platelet flips from one side to the other; the experimentally observed attachment angles (⋄) and detachment angles (○) obtained from experiments conducted at shear stresses of 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 4.0, and 8.0 dyn/cm2 are plotted with the theoretical bond force estimate. Note that the occurrence of attachment/detachment events corresponds to the negative/positive sign of the predicted radial force, respectively.

Analysis of platelet attachment/detachment events

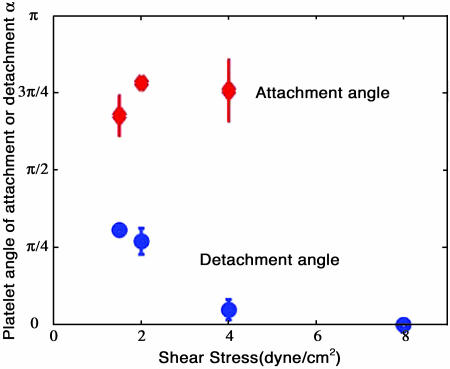

We analyzed experimental platelet tethering events using our platelet tracking/image processing algorithm to determine angles of platelet attachment to, and detachment from, the surface, and to correlate these angles with the predicted radial force acting on the ellipsoidal cell. Twenty-two attachment events and 30 detachment events were recorded for a total of 52. These events include all monitored platelet-surface contacts that resulted in attachment or detachment. We were unable to experimentally determine the number of contact events that result in attachment since we could not identify a non-adhesive contact event by visual observation; however, we could precisely determine an attachment event. The angles at which the platelets attached to the surface were all found to be >π/2 whereas the detachment angles were found to be <π/2, i.e., attachment occurred during the first-half of a platelet rotation (α = π to π/2) whereas detachment occurred during the second-half of a platelet flip (α = π/2 to 0). Fig. 4 B compares the experimentally observed attachment and detachment angles with the theoretical estimate of the radial force acting on the platelet. From these data, we noted a consistent record of platelet attachment events occurring when the platelet is predicted to experience hydrodynamic compressive force, with no observations of attachment when the radial force is predicted to be tensile in nature.

We examined how the average platelet attachment and detachment angles depend on wall shear stress for the 52 attachment and detachment events analyzed. Fig. 5 shows that, within experimental error, the attachment angle is independent of shear stress over a range of 1.5–4 dyn/cm2. Interestingly, the detachment angle was found to be a decreasing function of shear stress. Pooling the low shear data (1.5–2 dyn/cm2) and similarly pooling the high shear data (4–8 dyn/cm2) and comparing the mean of the two samples, we find that this difference reaches statistical significance (p < 0.001, student's t-test). Both the independence of the attachment angle and the dependence of the detachment angle with wall shear stress agree with our intuitive expectations. Initial platelet attachment should depend primarily on the incidence of cell contact, and in Stokes flows the trajectories of suspended particles are independent of wall shear rate (or equivalently, shear stress divided by fluid viscosity; see Appendices). Conversely, during the cell detachment process both the rotation rate and the magnitude of the force exerted on the formed bond(s) each depend linearly on the wall shear stress. Since the GPIbα-vWf bond has been found to exhibit selectin-like bond kinetics, dissociation rate will depend strongly on force in an exponential manner (Doggett et al., 2002). Since the full force-loading history on the receptor-ligand bond during platelet rotation is highly nonlinear, it will require detailed adhesive dynamics simulations to fully analyze and predict how detachment angles should correlate with wall shear stress and other physical determinants (King and Hammer, 2001a,b).

FIGURE 5.

Plot of the experimentally measured average attachment (⋄) and detachment angles (○), as a function of wall shear stress.

Characterization of the trajectories of freely flowing platelets

We characterized the trajectories of freely flowing platelets as they rotated in the direction of flow near the vWF-A1 functionalized surface. According to Frojmovic et al. (1990), the platelet can be viewed as an oblate spheroid with aspect ratio 0.25. Jeffery orbits (Jeffery, 1922) describe the periodic trajectories of oblate spheroids rotating in unbounded linear shear flow and were used to predict the rotational motion of free-stream platelets subjected to linear shear flow. The non-dimensionalized Jeffery equation yielding the periodic free-stream platelet trajectories is given by  where α is defined as shown in Fig. 4 A, r is the aspect ratio of the platelet taken as 0.25, and

where α is defined as shown in Fig. 4 A, r is the aspect ratio of the platelet taken as 0.25, and  is time non-dimensionalized with respect to fluid shear rate. Fig. 6 compares the rotational trajectories of free stream platelets flowing near the wall with the Jeffrey orbit prediction.

is time non-dimensionalized with respect to fluid shear rate. Fig. 6 compares the rotational trajectories of free stream platelets flowing near the wall with the Jeffrey orbit prediction.

FIGURE 6.

Plot of the trajectories of free-stream platelets as predicted by the Jeffery orbits theory, and platelet trajectories from experiments conducted at 0.2 dyn/cm2 shear stress. The experimental data (○, *, ▽, and △) are compared to the Jeffery orbit model for spheroid rotation in unbounded fluid (dashed line), and the theoretical prediction corrected to include the wall effect on plate rotational motion (thick solid line).

The Jeffery orbit theory does not account for the retardation of the rotational velocity of spheroids due to the presence of a nearby wall. Kim et al. (2001) showed that the viscous torque resistance to the rotation of a circular disk when oriented parallel to the plane, at a dimensionless distance h/a = 1 from an infinite plane, is 1.53 times greater than that for a circular disk rotating in unbounded fluid. At a distance of h/a = 0.6, where a is the disk radius, the relative torque increases to 1.88. Considering a platelet with aspect ratio 0.25 and in near contact with a wall, the maximum separation between the platelet centroid and the wall will have value h/a = 1.0 (corresponding to α = π/2), whereas the minimum separation will be h/a = 0.25 (corresponding to α = 0, π). As a first approximation to inclusion of the influence of the wall we chose an intermediate value of h/a = 0.6 and scaled the freestream platelet rotational velocity by the corresponding factor of 1.88. Here, rescaling the rotational velocity is equivalent to stretching the time domain. Fig. 6 compares the calculated rotational motion with the experimentally measured orientation angles. Note that the corrected trajectory is based on the results for a disk oriented horizontally and therefore may not be valid for nonparallel platelet orientations. Considering these approximations, as shown in Fig. 6, the agreement with our experiments is quite good and suggests that the effect of the wall is of sufficient magnitude to account for the discrepancy with the unbounded fluid Jeffrey orbit theory. Thus, together with the results of Fig. 4, these data show that although unbound flowing platelets sample all possible orientations, they consistently attach only during the first-half of their rotation (orientation angle α = π to π/2).

DISCUSSION

Over the past century, much theoretical and experimental work has elucidated the motion of spherical particles in Stokes flow for a variety of flow fields and bounding conditions. In the last four decades, significant progress has been made in the development of exact and approximate analytical solutions for hydrodynamic interactions in unbounded shear flow between two spheres (Lin et al., 1970; Batchelor and Green, 1972; Brenner and O'Neill, 1972) and between multiple spheres (Haber and Brenner, 1999). Dean and O'Neill (1963), O'Neill (1964), Brenner (1961), and Goldman et al. (1967a,b) developed exact solutions using bi-spherical coordinates for the translational and rotational motion of a sphere in bounded Stokes flow near a plane wall, and Brenner and Happel (1958) developed approximations for determining flow characteristics of viscous flow past a sphere in a cylinder. Solutions for the flow of nonspherical particles are less commonly available mainly because of the difficulties in determining the hydrodynamic interactions between nonspherical particles or a nonspherical particle and a plane. Jeffery (1922) solved the hydrodynamic problem of the motion of an ellipsoidal particle in fluid that is motionless at infinity. Yoon and Kim (1990) used boundary collocation methods to solve the mobility problem of two spheroids in Stokes flow. However, we are aware of no studies that have considered the motion of an ellipsoid or oblate spheroid near a plane wall under linear shear flow, a scenario highly relevant to platelet flow and adhesion in blood vessels.

Computational modeling of blood cell adhesion is a highly useful tool to clarify the influence of physicochemical factors (hydrodynamic flows, hydrodynamic cell-cell interactions, chemical kinetics) on adhesion dynamics of cells under flow. A number of theoretical models have been developed to describe blood cell adhesion to the vascular wall and cell-cell aggregation at physiological flow rates (Hammer and Apte, 1992; Helmke et al., 1998; Tandon and Diamond, 1997, 1998; Long et al., 1999; King and Hammer, 2001a,b). These models approximate blood cells as spherical in shape. Computational models of platelet adhesion to a surface under flow are lacking due to the scarcity of theoretical studies on nonspherical particulate-wall interactions under flow. Since platelet-shaped cells behave differently from spherical cells under shear flow, the unique shape of the platelet brings new challenges in understanding the effect of hydrodynamic forces on its tether bond formation.

In this article, we have presented a clear two-dimensional analytical model to characterize the flipping of tethered platelets at various physiological shear rates. Transient tethering and translocation of platelets by means of flipping on the injured endothelial surface is a characteristic feature of GPIbα-vWF-A1 interactions (Doggett et al., 2002), and has been likened to the rolling of leukocytes. Our theoretical model compares well with the experimentally observed platelet motion on an adhesive surface. Additionally, this theoretical analysis estimates the hydrodynamic radial force acting on the platelet, and predicts the force to be compressive (directed toward the wall) during the first half of the tethered platelet's flip on the surface and tensile (directed away from the wall) during the second half. For the case of a platelet freely flowing over the surface, the rotational motion of the platelet caused by shearing fluid forces results in the platelet edges being periodically pushed toward and pulled away from the surface. Note that a rigid spherical body does not experience a lateral force when flowing parallel to a planar wall in shear Stokes flow (Goldman et al., 1967a), whereas deformable droplets, on the other hand, experience a lift force away from the wall even at zero Reynolds number (Leal, 1980); such flow behaviors may be expected to influence contacting of cells with the wall. Finally, we analyzed the orientation of platelets at the time of binding to, and release from, the surface, and showed that all of the experimental observations of bond formation and bond dissociation correlate with the predicted sign of the hydrodynamic radial forces acting on the platelet, i.e., tethers are only observed to form when the predicted hydrodynamic force is compressive, whereas tethers are only observed to dissociate when the force is tensile.

Our findings suggest that the pattern of platelet binding to, and release from, a vWF-coated surface is governed by radial forces experienced by the platelet. Since we are unable to obtain a direct, experimental measurement of the hydrodynamic force acting on the platelet at the time of cell-surface binding, we must rely on the theoretical model's estimate of this force, which is derived through solution of the creeping flow equations and shown to accurately predict the instantaneous velocity of the observed flipping platelets. Tether bond formation appears to occur only in those orientations where a hydrodynamic compressive force is predicted to act along the platelet length, pushing it against the surface, thereby initiating cell adhesion. Compression promotes bond formation by bringing the surfaces into close molecular contact and helping to overcome repulsive long-range interactions between the surfaces (Bell et al., 1984). After initial bond formation, this force aids in maintaining close contact between the cell surfaces and strengthens the initial tether by promoting further bond formation.

Platelet-endothelial collision and resulting contact is expected to occur only under conditions of hydrodynamic compressive force on the platelet. Figs. 4 and 5 clearly demonstrate that although shear flow promotes contact and subsequent attachment at angles of incidence >90°, the angle of attachment is not found to be a function of shear rate. As explained earlier, this result is expected because particle trajectories are independent of the magnitude of shear rate in Stokes flow. Compressive force on the platelet, on the other hand, is a function of both the incident angle and shear rate. If a critical magnitude of compressive force was required to promote bond formation, one might expect to see a trend in the angles of bond formation with shear rate. Here, it is important to note that once the platelet collides with the surface at an angle (>90°), it remains in contact until it assumes a 90° orientation. Although the GPIbα-vWf-A1 bond formation kinetics have yet to be fully characterized, we speculate that a finite time of application of this compressive force may induce bond formation at smaller angles (but >90°) associated with less favorable compressive forces. It is therefore difficult to ultimately conclude the essentiality or non-essentiality of a minimum compressive force for binding from these data alone.

Although it is not obvious from the experiments and theoretical model whether cell compression or cell contact is directly responsible for the good agreement between the experimental observations of tether formation and dissociation and the theoretical calculation of hydrodynamic forces, the conclusion that compressive forces play a role in initiating tether formation is nevertheless consistent with the experimental and theoretical results, and is indirectly supported by these results. It has been shown that platelet tethering on immobilized vWf increases with increase in shear rate (Doggett et al., 2002), which implies that tether bond formation is positively influenced by shear rate and hence compressive hydrodynamic forces. The role of compressive forces in initiating receptor-ligand binding is a fundamental question in blood cell adhesion. Our results suggest the importance of sub-picoNewton compressive forces in the initial capture of human platelets to vWF under physiological flow conditions. Extending our findings to other families of bonds, there is a possibility that leukocyte selectin-ligand bonds may associate only under suitable conditions of compressive force, which is consistent with recent studies of leukocyte bond formation using micromanipulation techniques (Chesla et al., 1998).

The GPIbα-vWF-A1 tether bond requires a threshold level of fluid shear stress (73 s−1) (Doggett et al., 2002) to promote adhesive interactions. Below this shear threshold, platelets cease to interact with the immobilized vWF-A1 on the surface and continue to flow at hydrodynamic velocity. This similar property is also shown by L-selectin interactions with its sialylated glycoprotein ligand (shear threshold ∼40 s−1) (Finger et al., 1996). The mechanism by which shearing forces govern vWF-GPIbα binding is unknown. Interestingly, whereas GPIbα platelet receptors do not bind to circulating vWF multimeric plasma proteins under normal conditions, pathological high-shear stress conditions (above 60 dyn/cm2) induces binding of large circulating vWF to GPIbα (Konstantopoulos et al., 1997; Li et al., 2004) even in the absence of exogenous agonists or activating agents. Shear-induced GPIbα-vWF binding subsequently initiates platelet activation and aggregation. GPIbα cannot bind either surface-immobilized or circulating vWF under static conditions, which suggests that the mechanism of shear stress-induced binding is the same for both types of interactions. Our model (Eq. A31) shows that the radial compressive force acting on the platelet increases linearly with increasing shear rate, which implies that a critical shear threshold is equivalent to a critical normal force. According to our theory, the threshold shear rate of 73 s−1 for GPIbα-vWF-A1 adhesive interactions translates to a critical normal force of only 0.93 pN. By gaining a better understanding of the nature of hydrodynamic forces during cell adhesion, it will be possible to elucidate the link between the critical shear threshold and bond formation of GPIbα with vWF, a prime motivational factor for this study.

The hydrodynamic forces exerted on leukocyte bonds, during transient tethering or rolling on a reactive surface, can be determined by carrying out a simple force and torque balance on the model spherical leukocyte. This technique was first employed by Alon et al. (1995) for calculating the first-order kinetic parameters of the P-selectin-PSGL-1 bond, and again (1997) for studying L-selectin tethers. Shao et al. (1998) and Park et al. (2002) used this bond force calculation method for studying microvilli extension. Doggett et al. (2002) used this same force balance technique to determine the kinetic parameters of the GPIbα-vWF-A1 bond. They circumvented the problem of the platelet being nonspherical by coating microspheres with vWF-A1 and then allowing them to flow over surface-immobilized platelets. It is important to note that the majority of platelet bonds with the surface, unlike leukocyte tethers, will not experience a sizeable lever-arm effect due to distinct differences in the geometry of these two adhesive systems. In the case of a spherical leukocyte binding with the surface, a lever arm exerts force and torque on the cell at a location several microns upstream of the lowest point of the spherical cell body (Alon et al., 1995; Park et al., 2002). However, platelet bonds are usually located close to the point of platelet-surface contact (the so-called hinge region) while flipping. Additionally, due to the ellipsoidal shape of the platelet, normal forces cause the platelet to flip or rotate over the surface (which is not possible for tethered spherical cells) and so the lever effect is minimal here. Therefore, we assume that the force on the bond is of the same order of magnitude as the hydrodynamic radial force acting on the platelet.

A key element in these force and torque balances is the hydrodynamic shear force and torque that the cell experiences when stationary on a planar surface. These are provided by the solution for an immobilized sphere under linear shear flow contacting a plane wall, developed by Goldman et al. (1967b). However, as mentioned earlier, there are no existing solutions for the force exerted on a nonspherical cell tethered to a surface. What is of prime importance in any physiological model for blood cell adhesion is an accurate estimation of the forces acting on the cell near, or on, a surface. Without this knowledge it becomes difficult to predict the flow behavior of the cell, the behavior of bonds when the cell is tethered, and how quickly bonds will form or dissociate based on the range of forces acting on the bonds and cell. Such analysis of platelet tethering behavior is possible only if the hydrodynamic effects on platelet-shaped cells are well defined. For the case of a platelet tethered to, and translocating on a surface, the hydrodynamic forces acting on it will depend on its shape, size, and orientation. In the present article, we estimated the platelet as a flat plate, and proceeded to calculate the forces and torques acting on the plate for all orientations. Therefore, our results can be viewed as first estimates of the hydrodynamic force and torque on a platelet tethered to a surface, which can be compared with the observed platelet adhesive behavior to gain a better understanding of hydrodynamic effects on platelet adhesive phenomena.

Although the model presented here merits simplicity and provides insight into the force mechanics acting on the tethered platelet during its flipping motion on the surface, its utility is nevertheless limited since it does not consider binding kinetics and simplifies the platelet shape as a thin two-dimensional planar surface. A logical next step would be to develop a numerical simulation that examines the full three-dimensional motion of platelets during approach, collision, adhesion, and release from the vessel wall in order to extend the range of validity of the analytical model, and further define the precise force history on the GPIbα-vWF-A1 bond during tethering and translocation.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by a grant from the Whitaker Foundation to M.R.K., and a National Institutes of Health grant HL063244 and an American Heart Association grant 02-40009N to T.G.D.

APPENDIX 1

Jeong and Kim (1983) derived the analytical expressions for forces and moments due to linear shear flow acting on a stationary fence with unit length, mounted at an arbitrary angle α with respect to an infinite rigid wall (Fig. 2). The flow around the fence was assumed to be slow and viscous so that the inertial terms are negligible and flow may be approximated as Stokes flow. If  are unit vectors in the x and z directions respectively, the governing equations describing the flow are

are unit vectors in the x and z directions respectively, the governing equations describing the flow are

|

(A1) |

|

(A2) |

|

(A3) |

The Stokes equation and the continuity equation along with the above boundary conditions were solved by describing pressure and velocity as vector harmonic functions, transforming the resulting equations by Mellin transformation and then subsequently solving a set of simultaneous Wiener-Hopf equations in four unknowns using the technique described by Noble (1958). The normal force Fn, shear force Fr, and moment (or torque) Tf exerted on the fence by the fluid were calculated using the following relations:

|

(A4) |

|

(A5) |

|

(A6) |

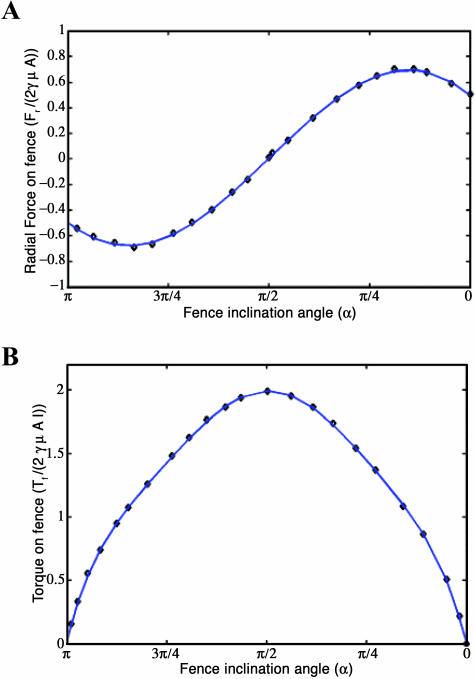

We found that the radial force Fr (Eq. A5) can be approximated (with maximum error of 3.6% and average error of 1.76%) by a polynomial fitted to the Jeong-Kim plot of analytically determined tangential force as a function of inclination angle α, as

|

(A7) |

where A is the area of one face of the plate.

The torque Tf generated by shear flow can be similarly approximated (with maximum error of 3.5% and average error of 1.1%) by a polynomial fitted to the Jeong-Kim plot of analytically determined torque as a function of inclination angle α, as

|

(A8) |

where ℓ is the height of the plate.

Fig. 7 demonstrates the good fit of the approximating polynomials determined by a least-squares regression fit to the analytically derived solution of force (Eq. A7) and torque (Eq. A8).

FIGURE 7.

Plots of the analytically derived solution for force and torque acting on a stationary inclined fence subjected to linear shear flow (fence problem; Jeong and Kim, 1983), and the polynomial approximations fitted to the analytical solution by least-squares regression. (A) Plot of force values taken from the analytically derived solution (Eq. A5) (♦) and force calculated from the polynomial approximation (Eq. A7) (thick solid line). (B) Plot of torque values taken from the analytically derived solution (Eq. A6) (♦) and torque calculated from the polynomial approximation (Eq. A8) (thick solid line).

APPENDIX 2

We derived the analytical expressions for the force and torque acting on a two-dimensional plate that rotates at an angular velocity ω, and is hinged to a rigid infinite wall, with the surrounding fluid being motionless at infinity. Fluid motion in the vorticity direction is neglected. The Stokes approximation is valid in general for flow of a viscous fluid near a sharp corner between two planes. Because of the microscopic dimensions of our fluid system, Stokes flow prevails everywhere in the fluid. Fluid motion on either side of the rotating plate is considered separately in our derivations. The full solution is then equal to the sum of both flows.

The flow due to the motion of the plate is unsteady and therefore the acceleration term in the equation of motion for a viscous incompressible fluid,  does not vanish. On non-dimensionalizing the time-dependent Stokes equation, we obtain

does not vanish. On non-dimensionalizing the time-dependent Stokes equation, we obtain  where NRE (Reynolds Number) = L2ρω/μ. Since for the experimental conditions studied NRE ≪ 1, the flow is in the Stokes regime and we may assume quasi-steady-state flow.

where NRE (Reynolds Number) = L2ρω/μ. Since for the experimental conditions studied NRE ≪ 1, the flow is in the Stokes regime and we may assume quasi-steady-state flow.

Hinge flow in the region downstream of the rotating plate

The surface at θ = 0 is stationary and the surface at θ = α moves at an angular velocity of ω(= −dα/dt) toward the horizontal surface (Fig. 2). Both angle α and angular velocity ω are functions of time. The derived results are valid at an instantaneous time t. This problem was solved using stream functions. The boundary conditions for this problem include the no-slip and no-penetration conditions at the solid surfaces, θ = 0, θ = α, and are expressed as

|

(A9) |

Solving the Stokes flow equation we obtain the non-dimensionalized velocity components as

|

(A10a) |

|

(A10b) |

where the variables are non-dimensionalized, as shown below, and where ℓ is the length of the hinged plate,

|

The pressure dependence on r,θ is determined by substituting Eq. A10 into the Navier-Stokes equations in cylindrical coordinates and integrating, yielding the result

|

(A11) |

where C1 is an integration constant. Note that the pressure is independent of θ.

The r- and θ-components of the dimensionless drag force can be evaluated from the expressions

|

(A12a) |

|

(A12b) |

where  is the viscous stress tensor, and

is the viscous stress tensor, and  is the pressure as determined above. The radial drag force was calculated as

is the pressure as determined above. The radial drag force was calculated as

|

(A13) |

which, evaluated at the planar surface, gives  Similarly, the θ-component of the force is obtained as

Similarly, the θ-component of the force is obtained as

|

which, when evaluated at the planar surface, yields

|

(A14) |

Note that the viscous stresses do not contribute to drag force on the hinged plate. Also, there is no radial force on the plate due to the hinge flow.

Hinge flow in the region upstream of the rotating plate

Next we considered the fluid motion induced on the other side of the rotating plate. The surface at θ = π is stationary and the surface at θ = α moves at an angular velocity of ω(= −dα/dt) away from the horizontal surface (Fig. 2). The solution of this problem is solved using the same methodology as in Hinge Flow in the Region Downstream of the Rotating Plate, above. The non-dimensionalized pressure and drag forces are calculated as

|

(A15) |

where C2 is an integration constant,

|

(A16) |

|

and

|

(A17) |

|

(A18) |

Evaluation of torque on the rotating plate

The torque on the plate—generated by pressure forces—which tends to oppose motion of the hinged plate, is calculated by substituting Eqs. A11 and A15 in

|

(A19) |

to yield

|

(A20) |

From the constraints of symmetry in Stokes flow for the geometry under consideration, C = C1 = −C2, where C is a constant taken to be independent of α, and Eq. A19 becomes

|

(A21) |

Determination of plate angle with respect to the surface as a function of time using combined fence and hinge flow solutions

The torques (calculated from the fence and hinge problems) acting on the plate are equated (Tf = Th) to obtain an expression for angular velocity ω = −dα/dt of the plate. The steady-state torque balance incorporating fence flow (Eq. A8) and hinge flow solutions (Eq. A21) yields an expression for ω,

|

which is rearranged to give

|

(A22) |

Numerical integration of Eq. A22 with respect to time yields the theoretical dependence of plate angle α (platelet orientation α) with time as the hinged plate (platelet) rotates (flips) with respect to the rigid wall under an imposed linear shear flow. Changing the single adjustable parameter C, representing the unknown pressure integration constant, results in a change in the slope of the curve. C takes on a value of 30 in our solution, which produces good agreement between the theoretical prediction and the experimental observations. To verify the Stokes approximation, NRE is calculated for the largest value of ω, which evaluated from Eq. A22 is 0.133γ. Substituting into the dimensionless group L2ρω/μ, one obtains 0.133 γ L2ρ/μ. Substituting pertinent values for these physical parameters, L = 3 μm, ρ = 1 g/cm3, μ = 1 cp, and shear rate = 100–800 s−1, the range of values derived are 1.2 × 10−4 to 9.6 × 10−4 which are ≪ 1. Thus the Stokes flow and quasi-steady-state assumption remain valid.

References

- Alevriadou, B. R., J. L. Moake, N. A. Turner, Z. M. Ruggeri, B. J. Folie, M. D. Phillips, A. B. Schreiber, M. E. Hrinda, and L. V. McIntire. 1993. Real-time analysis of shear-dependent thrombus formation and its blockade by inhibitors of von Willebrand factor binding to platelets. Blood. 81:1263–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon, R., D. A. Hammer, and T. A. Springer. 1995. Lifetime of the P-selectin carbohydrate bond and its response to tensile force in hydrodynamic flow. Nature. 374:539–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon, R., S. Chen, K. D. Puri, E. B. Finger, and T. A. Springer. 1997. The kinetics of L-selectin tethers and the mechanics of selectin-mediated rolling. J. Cell Biol. 138:1169–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor, G. K., and J. T. Green. 1972. The hydrodynamic interaction of two small freely-moving spheres in a linear flow field. J. Fluid Mech. 56:375–400. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, G. I., M. Dembo, and P. Bongrand. 1984. Cell adhesion. Competition between non-specific repulsion and specific bonding. Biophys. J. 45:1051–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, H., and J. Happel. 1958. Slow viscous flow past a sphere in a cylindrical tube. J. Fluid Mech. 4:195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, H. 1961. The slow motion of a sphere through a viscous fluid towards a plane surface. Chem. Eng. Sci. 16:242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, H., and M. E. O'Neill. 1972. On the Stokes resistance of multiparticle systems in a linear shear field. Chem. Eng. Sci. 27:1421–1439. [Google Scholar]

- Chesla, S. E., P. Selvaraj, and C. Zhu. 1998. Measuring two-dimensional receptor-ligand binding kinetics by micropipette. Biophys. J. 75:1553–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller, B. S., E. I. Peerschke, L. E. Scudder, and C. A. Sullivan. 1983. Studies with a murine monoclonal antibody that abolishes ristocetin-induced binding of von Willebrand factor to platelets: additional evidence in support of GPIb as a platelet receptor for von Willebrand factor. Blood. 61:99–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, M. A., T. G. Diacovo, J. Emsley, R. Liddington, and R. I. Handin. 2000. Mapping the glycoprotein Ib-binding site in the von Willebrand factor A1 domain. J. Biol. Chem. 275:252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean, W. R., and M. E. O'Neill. 1963. A slow motion of viscous liquid caused by the rotation of a solid sphere. Mathematika. 10:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Doggett, T. A., G. Girdhar, A. Lawshé, D. W. Schmidtke, I. J. Laurenzi, S. L. Diamond, and T. G. Diacovo. 2002. Selectin-like kinetics and biomechanics promote rapid platelet adhesion in flow: the GPIbα-vWF tether bond. Biophys. J. 83:194–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doggett, T. A., G. Girdhar, A. Lawshe, J. L. Miller, I. J. Laurenzi, S. L. Diamond, and T. G. Diacovo. 2003. Alterations in the intrinsic properties of the GPIbα-VWF tether bond define the kinetics of the platelet-type von Willebrand disease mutation, Gly233Val. Blood. 102:152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, X., and M. H. Ginsberg. 1997. Integrin α IIb β3 and platelet function. Thromb. Haemost. 78:96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger, E. B., K. D. Puri, R. Alon, M. B. Lawrence, U. H. von Andrian, and T. A. Springer. 1996. Adhesion through L-selectin requires a threshold hydrodynamic shear. Nature. 379:266–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frojmovic, M., K. Longmire, and T. G. M. Van de Ven. 1990. Long-range interactions in mammalian platelet aggregation. II. The role of platelet pseudopod number and length. Biophys. J. 58:309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, A. J., R. G. Cox, and H. Brenner. 1967a. Slow viscous motion of a sphere parallel to a plane wall. I. Motion through a quiescent fluid. Chem. Eng. Sci. 22:637–651. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, A. J., R. G. Cox, and H. Brenner. 1967b. Slow viscous motion of a sphere parallel to a plane wall. II. Couette flow. Chem. Eng. Sci. 22:653–660. [Google Scholar]

- Grunemeier, J. M., W. B. Tsai, C. D. McFarland, and T. A. Horbett. 2000. The effect of adsorbed fibrinogen, fibronectin, von Willebrand factor and vitronectin on the procoagulant state of adherent platelets. Biomaterials. 21:2243–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber, S., and H. Brenner. 1999. Hydrodynamic interactions of spherical particles in quadratic Stokes flows. Intl. J. Multiphase Flow. 25:1009–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, D. A., and S. M. Apte. 1992. Simulation of cell rolling and adhesion on surfaces in shear flow: general results and analysis of selectin-mediated neutrophil adhesion. Biophys. J. 62:35–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, B. P., M. Sugihara-Seki, R. Skalak, and G. W. Schmid-Schönbein. 1998. A mechanism for erythrocyte-mediated elevation of apparent viscosity by leukocytes in vivo without adhesion to the endothelium. Biorheology. 35:437–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, Y., M. Handa, K. Kawano, T. Kamata, M. Murata, Y. Araki, H. Anbo, Y. Kawai, K. Watanabe, I. Itagaki, K. Sakai, and Z. M. Ruggeri. 1991. The role of von Willebrand factor and fibrinogen in platelet aggregation under varying shear stress. J. Clin. Invest. 87:1234–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery, G. B. 1922. The motion of ellipsoidal particles immersed in a viscous fluid. Proc. Roy. Soc. Phys. A. 102:161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J., and M. Kim. 1983. Slow viscous flow around an inclined fence on a plane. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 52:2356–2363. [Google Scholar]

- Kasirer-Friede, A., M. R. Cozzi, M. Mazzucato, L. De Marco, Z. M. Ruggeri, and S. J. Shattil. 2004. Signaling through GP Ib-IX-V activates α IIb β3 independently of other receptors. Blood. 103:3403–3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.-U., K. W. Kim, Y.-H. Cho, and B. M. Kwak. 2001. Hydrodynamic force on a plate near the plane wall. I. Plate in sliding motion. Fluid Dyn. Res. 29:137–170. [Google Scholar]

- King, M. R., and D. A. Hammer. 2001a. Multiparticle adhesive dynamics: hydrodynamic recruitment of rolling leukocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:14919–14924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, M. R., and D. A. Hammer. 2001b. Multiparticle adhesive dynamics. Interactions between stably rolling cells. Biophys. J. 81:799–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantopoulos, K., T. W. Chow, N. A. Turner, J. D. Hellums, and J. L. Moake. 1997. Shear stress-induced binding of von Willebrand factor to platelets. Biorheology. 34:57–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, M. H., J. D. Hellums, L. V. McIntire, A. I. Schafer, and J. L. Moake. 1996. Platelets and shear stress. Blood. 88:1525–1541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R. A., J. F. Dong, J. A. Thaggard, M. A. Cruz, J. A. López, and L. V. McIntire. 2003. Kinetics of GPIbα-vWF-A1 tether bond under flow: effect of GPIbα mutations on the association and dissociation rates. Biophys. J. 85:4099–4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal, L. G. 1980. Particle motion in a viscous fluid. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 12:435–476. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F., C. Q. Li, J. L. Moake, J. A. López, and L. V. McIntire. 2004. Shear stress-induced binding of large and unusually large von Willebrand factor to human platelet glycoprotein Ibα. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 32:961–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C. J., K. J. Lee, and N. F. Sather. 1970. Slow motion of two spheres in a shear field. J. Fluid Mech. 43:35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Long, M., H. L. Goldsmith, D. F. J. Tees, and C. Zhu. 1999. Probabilistic modeling of shear-induced formation and breakage of doublets cross-linked by receptor-ligand bonds. Biophys. J. 76:1112–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, J. A., and J. F. Dong. 1997. Structure and function of the glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 4:323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelamegham, S., A. D. Taylor, J. D. Hellums, M. Dembo, C. W. Smith, and S. I. Simon. 1997. Modeling the reversible kinetics of neutrophil aggregation under hydrodynamic shear. Biophys. J. 72:1527–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble, B. 1958. Methods Based on the Wiener-Hopf Technique. Pergamon Press, London.

- O'Neill, M. E. 1964. A slow motion of viscous liquid caused by a slowly moving sphere. Mathematika. 11:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Parise, L. V. 1999. Integrin α(IIb)β(3) signaling in platelet adhesion and aggregation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11:597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, E. Y. H., M. J. Smith, E. S. Stropp, K. R. Snapp, J. A. DiVietro, W. F. Walker, D. W. Schmidtke, S. L. Diamond, and M. B. Lawrence. 2002. Comparison of PSGL-1 microbead and neutrophil rolling: microvillus elongation stabilizes P-selectin bond clusters. Biophys. J. 82:1835–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri, Z. M. 1997. Mechanisms initiating platelet thrombus formation. Thromb. Haemost. 78:611–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakariassen, K. S., P. A. Bolhuis, and J. J. Sixma. 1979. Human blood platelet adhesion to artery subendothelium is mediated by factor VIII-von Willebrand factor bound to subendothelium. Nature. 279:636–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage, B., S. J. Shattil, and Z. M. Ruggeri. 1992. Modulation of platelet function through adhesion receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 267:11300–11306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage, B., E. Saldivar, and Z. M. Ruggeri. 1996. Initiation of platelet adhesion by arrest onto fibrinogen or translocation on von Willebrand factor. Cell. 84:289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J., H. P. Ting-Beall, and R. M. Hochmuth. 1998. Static and dynamic lengths of neutrophil microvilli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:6797–6802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer, T. A. 1994. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 76:301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon, P., and S. L. Diamond. 1997. Hydrodynamic effects and receptor interactions of platelets and their aggregates in linear shear flow. Biophys. J. 73:2819–2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon, P., and S. L. Diamond. 1998. Kinetics of β2-integrin and L-selectin bonding during neutrophil aggregation in shear flow. Biophys. J. 75:3163–3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tees, D. F. J., O. Coenen, and H. L. Goldsmith. 1993. Interaction forces between red cells agglutinated by antibody. IV. Time and force dependence of breakup. Biophys. J. 65:1318–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turitto, V. T., H. J. Weiss, and H. R. Baumgartner. 1980. The effect of shear rate on platelet interaction with subendothelium exposed to citrated human blood. Microvasc. Res. 19:352–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, H. J., J. Hawiger, Z. M. Ruggeri, V. T. Turitto, P. Thiagarajan, and T. Hoffmann. 1989. Fibrinogen-independent platelet adhesion and thrombus formation on subendothelium mediated by glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex at high shear rate. J. Clin. Invest. 83:288–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, B. J., and S. Kim. 1990. A boundary collocation method for the motion of two spheroids in Stokes flow: hydrodynamic and colloidal interactions. Intl. J. Multiphase Flow. 16:639–649. [Google Scholar]