Abstract

TFII-I family proteins are characterized structurally by the presence of multiple reiterated I-repeats, each containing a putative helix–loop–helix domain. Functionally, they behave as multifunctional transcription factors that are activated by a variety of extracellular signals. In studying their subcellular localization, we noticed that these transcription factors frequently reside in subnuclear domains/dots. Because nuclear dots are believed often to harbor components of histone deacetylase enzymes (HDACs), we investigated whether TFII-I family proteins colocalize and interact with HDACs. Here, we show that TFII-I and its related member hMusTRD1/BEN physically and functionally interact with HDAC3. The TFII-I family proteins and HDAC3 also show nearly identical expression patterns in early mouse development. Consistent with our earlier observation that TFII-I family proteins also interact with PIASxβ, a member of the E3 ligase family involved in the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) pathway, we show further that PIASxβ physically and functionally interacts with HDAC3 and relieves the transcriptional repression exerted by HDAC3 upon TFII-I-mediated gene activation. These results suggest a complex interplay between two posttranslational pathways—histone modification and SUMOylation—brokered in part by TFII-I family proteins.

Extracellular signals often are transduced to the nucleus to bring about either up-regulation or down-regulation of specific genes. However, because the nuclear DNA is packaged with histones in nucleosomal arrays, to initiate transcriptional activation of any given gene, the promoter DNA must be accessible by the gene-specific activators as well as the basal machinery. Conversely, an actively transcribing genetic locus or a specific gene can be “‘switched off” by rendering the DNA inaccessible. Hence, the regulation of gene expression may begin at the level of chromatin alteration by concerted actions of histone-modifying enzymes. A histone acetyl transferase (HAT) acts by acetylating the tails of histones, lowering their positive charge and decreasing its stability of interactions with the DNA, upon which DNA becomes accessible. A histone deacetylase (HDAC) can reverse such an effect by deacetylating the histones, preserving their basic nature and, thereby, impeding DNA accessibility (1–3). Several other histone-tail modifications also have been described, such as methylation, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation (2, 3). It has been proposed that certain combinations of these modifications in one or more tails act sequentially or concomitantly to form a “histone code” recognized by specific regulatory proteins that lead to downstream events (4). It is generally believed that these enzymes are brought to the vicinity of the DNA and targeted to specific promoter regions through interactions with transcription factors, which can exert their effect only when the DNA is accessible. Therefore, to better understand how these enzymes regulate gene expression, considerable efforts have been spent to study their biochemical interactions with specific transcription factors. Here, we show that multifunctional factor TFII-I and its relative, hMusTRD1/BEN, interact physically and functionally with HDAC3.

TFII-I belongs to a family of proteins characterized by the presence of I-repeats (5–12, 40). TFII-I is a ubiquitously expressed multifunctional transcription factor that is activated in response to various extracellular signals ranging from antigenic stimulation in B cells to growth factor signaling in fibroblasts. TFII-I undergoes induced tyrosine phosphorylation in response to these signals and translocates to the nucleus. The tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of TFII-I is required for c-fos transcriptional activation. Thus, TFII-I is postulated to link signal-transduction events to transcription. Although TFII-I functions as a signal-responsive transcriptional activator, the precise role of the related family member hMusTRD1/BEN remains to be elucidated. Both transcription factors are mapped to the breakpoint regions of the 7q11.23 deletion, which is correlated with Williams–Beuren syndrome (6). Both genetic mapping studies and biochemical analyses show that each of these proteins has multiple isoforms in mice and in humans (11, 13–16). The transcription functions of hMusTRD1/BEN have not yet been well characterized biochemically. hMusTRD1/BEN was reported first as a muscle-specific activator of the troponin I gene (7, 40). It also seems to function as an activator in yeast one-hybrid assays (10). However, clear demonstration of its activator function has not been obtained. In contrast, results from our laboratory suggest that hMusTRD1/BEN may behave as a specific repressor of TFII-I (15). The repression by hMusTRD1/BEN appears to involve a two-step mechanism: a competition for a common cytoplasmic factor required for nuclear translocation and a competition for a nuclear cofactor required for transcriptional activation. Taken together, these results would suggest that hMusTRD1/BEN might act both as a transcriptional activator as well as a repressor.

To elucidate the biochemical mechanisms of action of these factors, we undertook yeast two-hybrid assays with both TFII-I and hMusTRD1/BEN as baits. These assays yielded PIASxβ as an interacting partner for both proteins (39). The PIAS family proteins are characterized by the presence of a RING-like zinc-finger motif presumably involved in protein—protein interactions (17–19). Several recent evidences support the involvement of a number of different and functionally distinct, RING-finger proteins in ubiquitin and small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)-dependent pathways (17, 18). The PIAS family proteins behave as E3 ligases in SUMOylation of several transcription factors in mammalian cell-free systems (20–23). In addition to their enzymatic functions, this family of proteins also may have functions related to chromosome structure and/or function (24–26). Interestingly, the PIAS family proteins localize to the nuclear dots (22, 27–29), which also harbor members of the HDAC family (30, 31), raising the possibility that these two family proteins physically and/or functionally interact to control gene expression. Consistent with this expectation, it indeed has been shown that HDAC1 is SUMOylated (32). In this manuscript, we show that both TFII-I and hMusTRD1/BEN interact physically and functionally with HDAC3 and that PIASxβ also interacts with HDAC3. The HDAC3-mediated repression of TFII-I-dependent transcription of the c-fos promoter is relieved by PIASxβ in a dose-dependent fashion, providing further biochemical evidence that there may be a general connection between the SUMO pathway and HDAC pathway via TFII-I family proteins.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, Antibodies, and Plasmids.

COS7 cells were grown under standard conditions. The monoclonal anti-FLAG (M2) and monoclonal anti-GST (GST-2) antibodies were purchased from Sigma. The monoclonal anti-GFP (JL-8) was obtained from CLONTECH. The pCEP4-FLAG-HDAC3 vector has been described (33).

Protein Analysis.

Transfections were performed with Lipofectamine (GIBCO/BRL) as described (15). For 10-cm-diameter cell culture dishes, the amount of transfected plasmid was 8 μg for FLAG-HDAC3, mPIASxβ (an N-terminal truncated form; ref. 39), and TFII-Iα, β, or Δ isoforms and 10 μg for hMusTRD1. Cells then were serum-starved for 16 h, stimulated for 20 min with recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rhEGF, 25 ng/ml; Sigma), and harvested 40 h posttransfection. For Western blot analysis, the primary anti-FLAG (1:2,000), anti-GST (1:3,500), and anti-GFP (1:2,000) antibodies and the secondary anti-mouse HRP-conjugated (Zymed) (1:10,000) antibodies were incubated in TBST buffer. Detection was done by enhanced chemiluminescence (NEN), using standard methods.

Immunostaining and Immunocytochemical Analysis.

COS7 cells were grown on coverslips, transfected with FLAG-HDAC3, TFII-I-GFP, or hMusTRD1-GFP alone, or cotransfected with FLAG-HDAC3 and TFII-I-GFP, or hMusTRD1-GFP or GFP-mPIASxβ. Nineteen hours after transfection, cells were serum-starved for 5 h and stimulated by 20 min with rhEGF (25 ng/ml; Sigma). Cells were washed twice with Dulbecco’s PBS, fixed, and stained as described (15). Cells were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG (1:1,500), followed by Alexa 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L; Molecular Probes; 1:20,000), and visualized on a fluorescence E400 Nikon microscope.

For the immunocytochemical analysis, CD-1 mouse embryos were obtained from timed-pregnant mice and fixed overnight at 4°C in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS. The fixed embryos were equilibrated overnight with 30% sucrose/PBS, followed by 30% sucrose/OCT (1:1) at 4°C. Embryos were transferred to embedding chambers, covered with OCT (Tissue-Tek Ost4583 compound, Miles), and stored at −70°C. Frozen sections were treated according to the standard protocols. Rabbit anti-BEN, anti-TFII-I, and anti-HDAC3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) polyclonal primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C and then incubated with the biotin-SP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Staining with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma) and counterstaining with Harris' hematoxylin were performed as recommended by the manufacturer. For negative controls, the same protocols were used without the addition of primary antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation Assays.

For coimmunoprecipitation experiments, cells were lysed in 25 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0/100 mM KCl/0.1% Triton X-100/0.05% Nonidet P-40/5 mM NaF/2 mM Na3VO4/1 mM Na2P4O7/1× EDTA-free antiprotease mixture (Roche)/10% glycerol. Whole-cell extracts (500 ng) were immunoprecipitated with 12.25 μg of anti-FLAG mAb and 35 μl of protein G-Sepharose (slurry, 1:1). Western blot analysis was performed as described above.

Reporter Gene Assays.

COS7 cells were transfected with 600 ng of c-fos-luciferase reporter plasmid and either pEBB empty vector, wild-type TFII-I, and mPIASxβ in the absence or presence of HDAC1 or HDAC3 and 35 ng of Renilla–luciferase plasmid. Total transfected DNA was kept constant by using empty vector pEBB. Before harvesting, cells were serum-starved for 16 h and stimulated with rhEGF (25 ng/ml; Sigma) for 4 h. Luciferase activity was assessed by using the Dual Luciferase kit (Promega). Each experiment was done in triplicate and repeated at least twice.

Results

Colocalization of TFII-I Family Proteins and PIASxβ with HDACs.

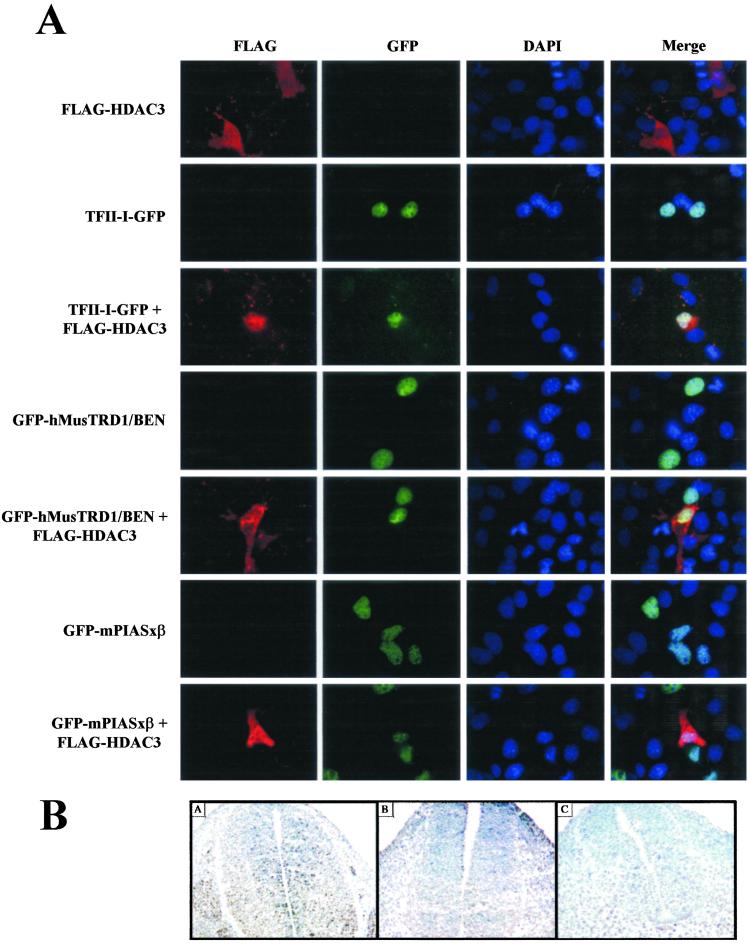

To evaluate the subcellular localization of HDAC3 with TFII-I family proteins and their interacting partner, PIASxβ, we expressed them ectopically in COS7 cells. HDAC3 was visualized by virtue of its FLAG-tag, whereas TFII-I, hMusTRD1/BEN, and PIASxβ were visualized by fluorescence by virtue of their GFP tags. Under our conditions, HDAC3 was expressed both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus (Fig. 1A). Under the same conditions, TFII-I was expressed predominantly in the nucleus. Although distinct colocalization was observed when both were coexpressed, a significant amount of HDAC3 remained in the cytoplasm. It is unclear at the moment whether the proportion of nuclear HDAC3 is greater when coexpressed with TFII-I. Similar staining and colocalization patterns were observed with hMusTRD1/BEN and PIASxβ either when expressed individually or when coexpressed with HDAC3. It is also apparent that ectopic expression of TFII-I (34) and, particularly, PIASxβ gave rise to speckled nuclear dots resembling those of promyelocytic leukemia (PML) bodies (22, 27–29). HDAC3 colocalized with these proteins in the nucleus, further suggesting that these proteins may interact physically with each other in nuclear and/or subnuclear regions. Colocalization of these proteins with HDAC1 in the nucleus also is observed (data not shown). Because TFII-I is activated in response to growth factors, we tested the colocalization of TFII-I with HDAC3 in the absence or presence of EGF. However, no apparent differences were observed under our conditions (data not shown).

Figure 1.

HDAC3 partially colocalizes with TFII-I, hMusTRD1/BEN, and mPIASxβ in mammalian cells and during early embryogenesis. (A) COS7 cells were transfected with 500 ng of FLAG-HDAC3 expression plasmid (first row) and 200 ng each of TFII-I-GFP (second row), GFP-hMusTRD1/BEN (fourth row), or GFP-mPIASxβ (sixth row) or cotransfected with 500 ng of FLAG-HDAC3 and 200 ng of TFII-I-GFP, GFP-hMusTRD1/BEN, or GFP-mPIASxβ (third, fifth, and last row, respectively). The ectopically expressed proteins were visualized by indirect immunofluorescence by using a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody and Alexa 594 goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Merge of GFP, Alexa 594, and DAPI images are shown at the far right. (B) Frozen sections of mouse embryos at E10.5 were stained with the following antibodies: anti-BEN (A), anti-TFII-I (B), or anti-HDAC3 (C). All three proteins show nuclear expression and overlap in the neural tube and somites.

Our immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated a broad and extensive overlap expression of BEN and TFII-I during mouse postimplantation development (unpublished results), further suggesting that these proteins may have functional association during early embryogenesis. Consistent with this notion, we show that in mouse embryo (around E10.5), the expression patterns of TFII-I, BEN, and HDAC3 in the neural tube, somites, and dorsal root ganglia are very similar (Fig. 1B).

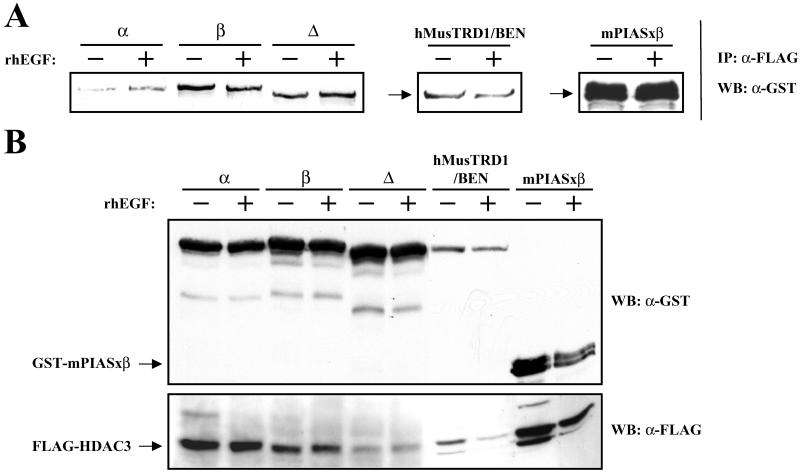

Physical Interactions of HDAC3 with TFII-I, hMusTRD1/BEN, and PIASxβ.

Given the colocalization of these proteins, we directly tested their physical interactions. Because TFII-I has multiple isoforms, we also tested the interaction potentials of some of these isoforms with HDAC3. For this purpose, either TFII-Iα, TFII-Iβ, TFII-IΔ, hMusTRD1/BEN, or PIASxβ (all GST-tagged) were transiently coexpressed with HDAC3 (FLAG-tagged) in COS7 cells. Interaction with HDAC3 was assessed by immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody, and the interacting proteins were visualized by probing with an anti-GST antibody. Although all three isoforms of TFII-I interacted with HDAC3 (Fig. 2A) either in the absence or presence of EGF, interaction of the α-isoform was noticeably less than either the Δ- or the β-isoform. Similarly, hMusTRD1/BEN interacted with HDAC3 either in the absence or presence of EGF. Interaction of PIASxβ with HDAC3 was much greater than observed either with TFII-I isoforms or with hMusTRD1/BEN. Once again, however, no apparent differences were observed in the presence or absence of EGF. Western blot analysis was performed to ascertain the levels of expression of all of the proteins (Fig. 2B). The various isoforms of TFII-I all were expressed at a comparable level and similar to PIASxβ. But, hMusTRD1/BEN was expressed at a considerably lower level. Thus, when normalized to the expression levels, it appears that hMusTRD1/BEN and PIASxβ interact better than TFII-IΔ with HDAC3. However, because the expression of HDAC3 in cells coexpressing hMusTRD1/BEN is also lower than cells coexpressing either TFII-Iα and TFII-Iβ isoforms or PIASxβ proteins, the interactions between hMusTRD1/BEN with HDAC3 could be even greater. Interactions of these proteins with HDAC1 also was observed, although they were weaker than observed with HDAC3 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

HDAC3 interacts physically with TFII-I isoforms (α, β, and Δ), hMusTRD1/BEN, and mPIASxβ. (A) COS7 cells were cotransfected with a FLAG-HDAC3 expression vector and plasmids for the indicated GST proteins in the absence or presence of rhEGF. Whole-cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody, and interacting proteins were visualized with anti-GST antibody. (B) Cell extracts from A were Western-blotted with anti-FLAG antibody (Lower) and then stripped and reprobed with anti-GST antibody (Upper).

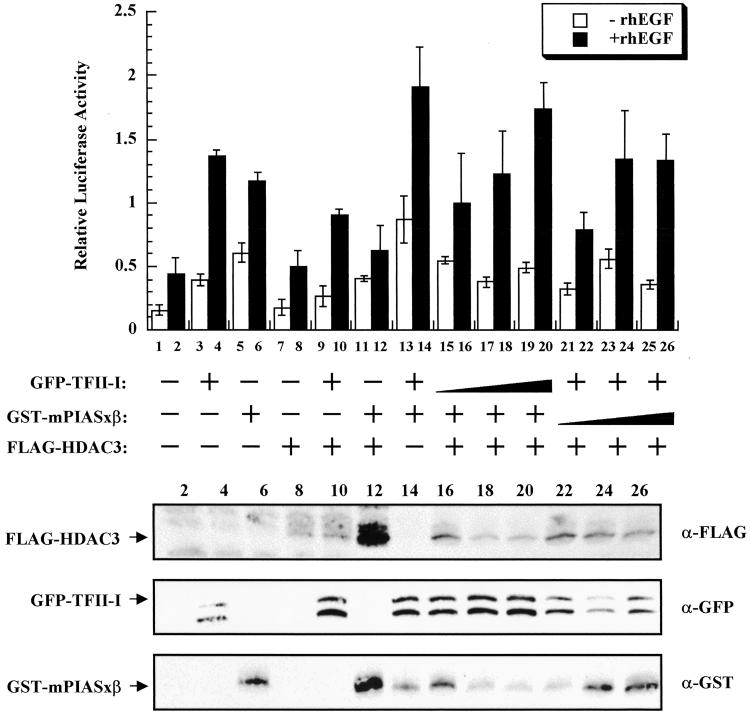

HDAC3 Represses TFII-I- and PIASxβ-Dependent Transcription.

HDAC proteins are known to function as repressors/corepressors. Thus, we tested whether HDAC3 would repress TFII-I-dependent activation of the c-fos promoter in a transient, cotransfection assay. We have shown that PIASxβ stimulates the c-fos promoter in the presence of EGF, most likely reflecting a coactivator function with endogenous TFII-I (39). Whereas both TFII-I and PIASxβ activated the c-fos promoter in EGF-dependent fashion, HDAC3 repressed both TFII-I- and PIASxβ-dependent transcription (Fig. 3). However, HDAC3 appears to be expressed generally at low levels. We also have shown that PIASxβ functions as a coactivator with TFII-I to stimulate the c-fos promoter (39). Although, HDAC3 repressed the transcriptional coactivation by TFII-I and PIASxβ, the repression was almost fully relieved in the presence of increasing amounts of TFII-I. Relief of HDAC3-mediated transcriptional repression was observed in the presence of increasing amounts of PIASxβ, but a plateau was reached at the highest levels of PIASxβ. The latter could be a result of the decreased expression of TFII-I, which often is observed at very high concentrations of PIASxβ expression plasmid. Taken together, these results suggest that perhaps HDAC3 can be titrated away from the promoter by either TFII-I or PIASxβ in a concentration-dependent manner.

Figure 3.

HDAC3 represses TFII-I- and mPIASxβ-dependent transcriptional activity. COS7 cells were cotransfected with a c-fos luciferase vector together with either 600 ng each of TFII-I or mPIASxβ or 800 ng of HDAC3 expression vectors in indicated combinations. Relative luciferase activity was measured in the absence (open bars) or presence of 25 ng/ml rhEGF (solid bars). Lanes 1 and 2, empty vector; 3 and 4, 600 ng of TFII-I; 5 and 6, 600 ng of mPIASxβ; 7 and 8, 800 ng of HDAC3; 9 and 10, 600 ng of TFII-I + 800 ng of HDAC3; 11 and 12, 600 ng of mPIASxβ + 800 ng of HDAC3; 13 and 14, 600 ng of TFII-I + 600 ng of mPIASxβ; 15–20, 600 ng of mPIASxβ + 800 ng of HDAC3 + increasing concentrations of TFII-I; 21–26, 600 ng of TFII-I + 800 ng of HDAC3 + increasing concentrations of mPIASxβ (15, 16, 21, and 22, 600 ng; 17, 18, 23, and 24, 1,200 ng; 19, 20, 25, and 26, 1,800 ng). The result is the average of a representative experiment done in triplicate. (Lower) Western blot analyses of representative lysates.

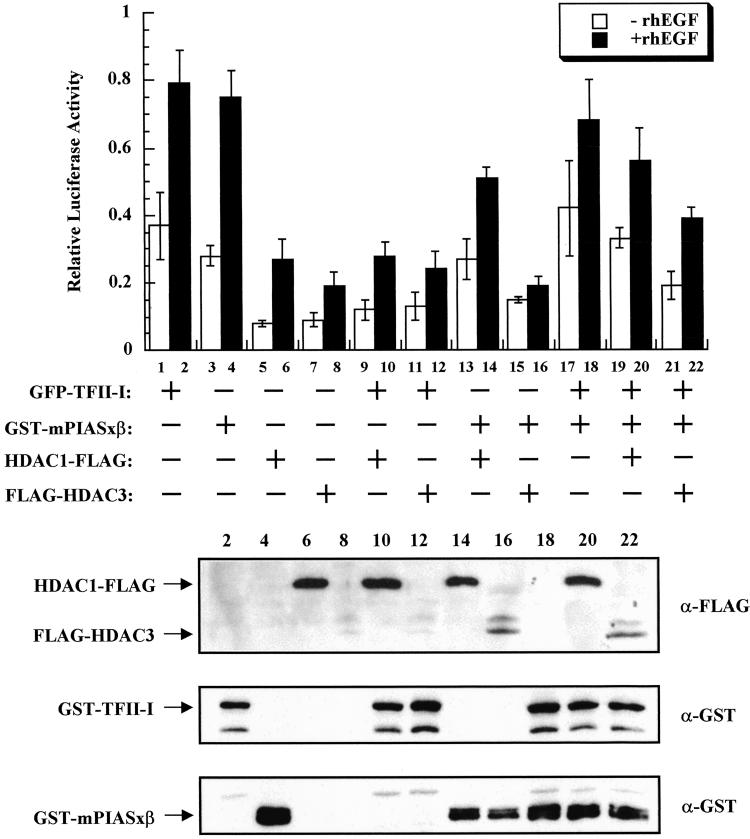

Given that under our experimental conditions HDAC3 interacted better with both TFII-I and PIASxβ than HDAC1, we tested whether there is a difference in the repressive potentials between HDAC1 and HDAC3. Employing similar transient transfection assays, we evaluated the repression by both HDAC3 and HDAC1 (Fig. 4). Although TFII-I- and PIASxβ-dependent transcription was repressed significantly by HDAC1 and HDAC3, the latter was more efficient in the case of PIASxβ compared with TFII-I. A substantial difference between HDAC1 and HDAC3 also was observed when both TFII-I and PIASxβ were present together. These results may reflect the fact that HDAC3 interacts better with both proteins than HDAC1 and that HDAC3 interacts far better with PIASxβ than with TFII-I.

Figure 4.

HDAC3 is better than HDAC1 as a repressor of TFII-I and mPIASxβ transcriptional activity. Relative c-fos luciferase activity in the absence (open bars) or presence of 25 ng/ml rhEGF (solid bars) of indicated expression plasmids is shown (Upper). Lanes 1 and 2, 800 ng of TFII-I; 3 and 4, 800 ng of mPIASxβ; 5 and 6, 800 ng of HDAC1; 7 and 8, 800 ng of HDAC3; 9–12, 800 ng of TFII-I + 800 ng of HDAC1 (9 and 10) or 800 ng of HDAC3 (11 and 12); 13–16, 800 ng of mPIASxβ + 800 ng of HDAC1 (13 and 14) or 800 ng of HDAC3 (15 and 16); 17–22, 600 ng of TFII-I + 1,200 ng of mPIASxβ (17 and 18) + 800 ng of HDAC1 (19 and 20) or 800 ng of HDAC3 (21 and 22). The result is the average of a representative experiment done in triplicate. (Lower) Western blot analyses of representative lysates.

Discussion

The packaging of eukaryotic DNA with histones into higher-order chromatin structure gives rise to an additional layer of regulation of gene expression at the level of promoter accessibility (1–3). Thus, the mechanism of action of chromatin-remodeling complexes and histone-modifying enzymes in the activation and repression of transcription has become a highly active area of study. Because binding of gene-specific transcription factors is a prerequisite for active transcription, it is generally believed that there must be an active communication between transcription factors and chromatin-modifying molecules. The chromatin-modifying molecules, depending on their particular activity and association with specific transcription factors, can be classified either as transcriptional coactivators or corepressors (1–3). Here, we show both physical and functional association of HDAC3 with TFII-I family proteins and PIASxβ, a member of the E3 ligase family proteins involved in SUMOylation of several transcription factors (20–23).

Although association of HDAC3 was observed with three predominant isoforms of TFII-I, α-isoform interacts much less than the other two isoforms. The reason for this is not clear at present. Moreover, at present, we also do not know whether HDAC3-mediated repression of TFII-I-dependent transcription involves enzymatic modification of TFII-I. The interactions of hMusTRD1/BEN with HDAC3 are better than those of TFII-I with HDAC3. Given that hMusTRD1/BEN may behave as a transcriptional repressor, at least under some conditions, it is not totally surprising that hMusTRD1/BEN could be better associated with HDAC3 in vivo. Together with the fact that these factors colocalize in nuclear dots, which potentially may represent PML bodies, our data raise the possibility that the functional activity of the TFII-I family of transcription factors may be modulated by association with HDAC proteins in PML bodies. Regardless of the potential association of HDAC proteins with the TFII-I family in PML bodies, it is clear that these proteins colocalize in cultured cells and exhibit overlapping expression patterns in developing tissues. It has been demonstrated in Xenopus oocytes that maternal HDAC with potential enzymatic activity is accumulated in nuclei (35). Here, we show that in the developing mouse embryo, the expression patterns of TFII-I, MusTRD1/BEN, and HDAC3 are very similar. These data raise the possibility that the transcriptional activity of the TFII-I family of transcription factors may be controlled by HDACs during early development.

One of the more exciting findings is the physical and functional association of PIASxβ with HDAC3. The PIAS family proteins first were identified as inhibitors of signal transducers of activated transcription factors (STATs; refs. 36–38). Structurally, they are characterized by the presence of a RING-like zinc-finger motif that is thought to be involved in protein–protein interactions (17–19). A number of different and functionally distinct RING-finger proteins have been implicated in ubiquitin and SUMO-dependent pathways (17, 18). The PIAS family proteins behave as E3 ligases in SUMOylation of several transcription factors in both yeast and mammalian cell-free systems (20–23). Besides their enzymatic functions, this family of proteins also may have regulatory roles related to chromosome structure and/or function (24–26). An interesting connection between HDAC activity and the SUMO pathway recently was provided by DePinho and colleagues, which showed that the HDAC1 molecule is modified by SUMO-1 and that this modification can dramatically alter HDAC1 activity (32). Our data provide a direct demonstration that a key intermediate in the SUMO pathway, PIASxβ, physically interacts with HDAC3. However, although PIASxβ interacts with HDAC3, the latter does not appear to have a consensus SUMOylation site. Thus, we favor a model in which the PIASxβ may provide a regulatory role to control the activity of HDAC3. Current efforts in our laboratory are directed toward understanding the complex role of PIASxβ in simultaneously modulating HDAC and TFII-I activities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Brodeur for critical reading of the manuscript, and Stuart Schreiber for his generous gift of the HDCA1 cDNA. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI45150 (to A.L.R.).

Abbreviations

- HAT

histone acetyl transferase

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- rhEGF

recombinant human epidermal growth factor

- SUMO

small ubiquitin-like modifier

- PML

promyelocytic leukemia

References

- 1.Cress W D, Seto E. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:1–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200007)184:1<1::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmorstein R. Nat Rev. 2001;2:422–432. doi: 10.1038/35073047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narlikar G J, Fan H Y, Kingston R E. Cell. 2002;108:475–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00654-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strahl B D, Allis C D. Nature (London) 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayarsaihan D, Ruddle F H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7342–7347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franke Y, Peoples R J, Francke U. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1999;86:296–304. doi: 10.1159/000015322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Mahoney J V, Guven K L, Lin J, Joya J E, Robinson C S, Wade R P, Hardeman E C. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6641–6652. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osborne L R, Campbell T, Daradich A, Scherer S W, Tsui L C. Genomics. 1999;57:279–284. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tassabehji M, Carette M, Wilmot C, Donnai D, Read A P, Metcalfe K. Eur J Hum Genet. 1999;7:737–747. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan X, Zhao X, Qian M, Guo N, Gong X, Zhu X. Biochem J. 2000;345:749–757. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez-Jurado L A, Wang Y K, Peoples R, Coloma A, Cruces J, Francke U. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:325–334. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy A L, Du H, Gregor P D, Novina C D, Martínez E, Roeder R G. EMBO J. 1997;16:7091–7104. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y K, Perez-Jurado L A, Francke U. Genomics. 1998;48:163–170. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheriyath V, Roy A L. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26300–26308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002980200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tussié-Luna M I, Bayarsaihan D, Ruddle F H, Roy A L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7789–7794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141222298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayarsaihan D, Dunai J, Greally J M, Kawasaki K, Sumiyama K, Enkhmandakh B, Shimizu N, Ruddle F H. Genomics. 2002;79:137–143. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freemont P S. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R84–R87. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochstrasser M. Cell. 2001;107:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00519-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kentsis A, Gordon R E, Borden K L B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:667–672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012317299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson E S, Gupta A A. Cell. 2001;106:735–744. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahyo T, Nishida T, Yasuda H. Mol Cell. 2001;8:713–718. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sachdev S, Bruhn L, Sieber H, Pichler A, Melchior F, Grosschedl R. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3088–3103. doi: 10.1101/gad.944801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt D, Müller S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2872–2877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052559499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aravind L, Koonin E V. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:112–114. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01537-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hari K L, Cook K R, Karpen G H. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1334–1348. doi: 10.1101/gad.877901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strunnikov A V, Aravind L, Koonin E V. Genetics. 2001;158:95–107. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valdez B C, Henning D, Perlaky L, Busch R K, Busch H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:335–340. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molainen A, Karvonen U, Poukka H, Yan W, Toppari J, Jänne O A, Palvimo J J. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3700–3704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotaja N, Karvonen U, Janne O A, Palvimo J J. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5222–5234. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.5222-5234.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matiullah K, Nomura T, Kim H, Kaul S C, Wadhwa R, Shinagawa T, Ichikawa-Iwata E, Zhong S, Pandolfi P P, Ishii S. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu W S, Vallian S, Seto E, Yang W M, Edmonson D, Roth S, Chang K S. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2259–2268. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2259-2268.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.David G, Neptune M A, DePinho R A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23658–23663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang W M, Yao Y L, Sun J M, Davie J R, Seto E. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28001–28007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.28001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novina C D, Kumar S, Bajpai U, Cheriyath V, Zhang K, Pillai S, Wortis H H, Roy A L. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5014–5024. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryan J, Llinas A J, White D A, Turner B M, Sommerville J. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2441–2452. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.14.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung C D, Liao J, Liu B, Rao X, Jay P, Berta P, Shuai K. Science. 1997;278:1803–1805. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5344.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu B, Liao J, Rao X, Kushner S A, Chung C D, Chang D D, Shuai K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10626–10631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu B, Gross M, tenHoeve J, Shuai K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3203–3207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051489598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tussié-Luna, M. I., Michel, B., Hakre, S. & Roy, A. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.O'Mahoney J V, Guven K L, Lin J, Joya J E, Robinson C S, Wade R P, Hardeman E C. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5361. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]