Abstract

Fibrinogen binding to integrin αIIbβ3 mediates platelet aggregation and requires agonist-induced “inside-out” signals that increase αIIbβ3 affinity. Agonist regulation of αIIbβ3 also takes place in megakaryocytes, the bone marrow cells from which platelets are derived. To facilitate mechanistic studies of inside-out signaling, we describe here the generation of megakaryocytes in quantity from murine embryonic stem (ES) cells. Coculture of ES cells for 8–12 days with OP9 stromal cells in the presence of thrombopoietin, IL-6, and IL-11 resulted in the development of large, polyploid megakaryocytes that produced proplatelets. These cells expressed αIIbβ3 and platelet glycoprotein Ibα but were devoid of hematopoietic stem cell, erythrocyte, and leukocyte markers. Mature megakaryocytes, but not megakaryocyte progenitors, specifically bound fibrinogen by way of αIIbβ3 in response to platelet agonists. Retrovirus-mediated expression of the reporter gene, green fluorescent protein, in ES cell-derived megakaryocytes did not affect viability or αIIbβ3 function. On the other hand, retroviral expression of CalDAG-GEFI, a Rap1 exchange factor identified by megakaryocyte gene profiling as a candidate integrin regulator, enhanced agonist-induced activation of Rap1b and fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3 (P < 0.01). These results establish that ES cells are a ready source of mature megakaryocytes for integrin studies and other biological applications, and they implicate CalDAG-GEFI in inside-out signaling to αIIbβ3.

Platelet aggregation during hemostasis requires the interaction of integrin αIIbβ3 with soluble adhesive ligands, such as fibrinogen or von Willebrand factor. Ligand binding to αIIbβ3 is tightly regulated by inside-out signals that ultimately control integrin conformation (e.g., affinity) and/or clustering (avidity; refs. 1–3). Studies of human platelets have implicated cytoplasmic Ca2+, protein kinase C, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and cytoskeletal proteins in inside-out signaling (4–6). Recent studies of gene-targeted murine platelets have defined the requirements for specific agonist receptors, heterotrimeric G proteins, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase γ, and VASP in the regulation of fibrinogen binding or platelet aggregation (7–12). In addition, abnormal aggregation responses have been demonstrated in platelets deficient in proteins not ordinarily considered as mediators of inside-out signaling, including μ calpain, PECAM-1, and transforming growth factor β1 (13–16). Thus, the control of αIIbβ3 affinity and avidity seems to be complex and the mechanisms remain to be fully characterized.

Integrin signaling in nucleated cells can be studied by manipulating gene expression in vitro, an approach not possible with anucleate platelets. However, platelets are produced by polyploid megakaryocytes, and megakaryocytes derived in culture from bone marrow or peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cells bind fibrinogen by αIIbβ3 in response to platelet agonists (17, 18). In this system, expression of a constitutively active form of Rap1b leads to enhanced agonist-induced fibrinogen binding, suggesting that this Ras family member may be involved in inside-out signaling (15). In contrast, megakaryocytes from mice deficient in a transcription factor, NF-E2, express αIIbβ3 but show markedly decreased agonist-induced fibrinogen binding (17). On the basis of the assumption that gene(s) regulated by NF-E2 are required for inside-out signaling, we recently used cDNA arrays to identify genes differentially expressed in NF-E2−/− and wild-type megakaryocytes (R.M., S.K., M. Shiraga, A. Alizadeh, M. Diehn, P.O. Brown, S.J.S., and A.D.L., unpublished observations). One gene found to be deficient in NF-E2−/− megakaryocytes is CalDAG-GEFI, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Rap1 (19–21). Because exchange factors promote GTP-loading and activation of GTPases, CalDAG-GEFI is a candidate to regulate Rap1b and αIIbβ3.

In theory, the forced expression of candidate genes like CalDAG-GEFI in megakaryocytes could provide a useful way to determine their roles in αIIbβ3 signaling. However, this approach is currently limited by the need to harvest and expand hematopoietic stem cells from numerous mice. An appealing and potentially more flexible alternative is to start with embryonic stem (ES) cells because they have the potential to differentiate into all hematopoietic lineages, to integrate vectors capable of driving conditional gene expression in differentiated cells, and to provide a virtually unlimited supply of megakaryocytes (22–27). However, it is currently unclear whether mature, functional megakaryocytes can be derived from ES cells in sufficient quantities for investigations of αIIbβ3 signaling. In the present study, we show that this goal can be achieved. Furthermore, by using CalDAG-GEFI as a test case, we establish that forced expression of this exchange factor activates endogenous Rap1b and enhances agonist-induced fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3.

Methods

Growth and Differentiation of ES Cells.

The murine R1 ES cell line (28) was maintained for up to 10 passages on irradiated mouse feeder cells in complete DMEM (GIBCO/Invitrogen) supplemented with 500 units/ml mouse leukemia inhibitory factor (Chemicon). For differentiation into megakaryocytes, cells were dissociated with 0.25% trypsin/EDTA and allowed to settle for 75 min to deplete adherent feeder cells. Then 1.0 × 104 ES cells were seeded into each well of a six-well plate containing confluent OP9 stromal cells, which are derived from the calvaria of newborn M-CSF-deficient B6C3F1-op/op mice, and cultured in α-MEM medium (GIBCO/Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% FBS (25). After 5 days in culture, the cells were dissociated and seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well onto a fresh OP9 layer in the same culture medium supplemented with 20 ng/ml murine thrombopoietin (TPO; Kirin Brewery, Tokyo). After three more days (e.g., day 8 of differentiation), nonadherent and adherent cells were reseeded onto a new OP9 layer and cultured for four more days (e.g., day 12) in the presence of 10 ng/ml TPO, murine IL-6, and human IL-11 (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA). Although IL-6 and IL-11 were not necessary for megakaryocytopoiesis in this system, they marginally enhanced the yield of viable, mature megakaryocytes.

Characterization of Megakaryocytes Derived from ES Cells.

Cytospin preparations of 2 to 10 × 104 cells were stained with Wright-Giemsa (Biochemical Sciences, Swedesboro, NJ) or by immunocytochemistry by using the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories). For the latter process, cells were stained for 30 min with biotinylated antibodies to αIIb (PharMingen), GP Ibα (from V. Ramikrishnan, Cor Therapeutics, South San Francisco, CA) or a biotinylated control IgG (PharMingen). Cell light-scatter profiles, antigen expression, and DNA ploidy were assessed by flow cytometry (17).

Retroviral Infection of Megakaryocytes.

The MSCV2.1 retroviral vector containing murine CalDAG-GEFIa cDNA fused to the V5 epitope tag and an IRES-GFP cassette was provided by A. Dupuy and D. Largaespada, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (20). A control vector encoding only IRES-GFP was prepared by subcloning the BamHI–ClaI IRES-GFP fragment from pIRES2-EGFP (CLONTECH) into the MSCV2.1 vector backbone. Relevant sequences were verified by automated DNA sequencing. Viruses were produced by calcium phosphate transfection of 293T cells by using 10 μg of MSCV expression vector, 15 μg of envelope plasmid pCI-VSVG, and 10 μg of packaging plasmid pHit-60 (29). Viral titers were determined 48 h later by measuring GFP expression in infected NIH 3T3 cells and ranged from 0.4 to 1 × 107 units/ml.

To obtain megakaryocytes expressing retrovirally transduced proteins, hematopoietic cells on day 5 of the differentiation protocol were resuspended to 8 × 105/ml in α-MEM containing 20 ng/ml TPO. After addition of an equal volumes of virus stock and 4 μg/ml polybrene, the cells were cultured for 18 h at 37°C, washed, placed at 4 × 105 per well onto a fresh OP9 layer, and cultured until day 12, as described above.

Functional Analyses of Megakaryocytes.

After 12 days of ES cell differentiation, nonadherent cells were sedimented by gravity for 60 min at 37°C. To optimize megakaryocyte yield, hematopoietic cells still adherent to the OP9 layer were resuspended and passed through mesh to eliminate cell clumps. For fibrinogen binding, pooled hematopoietic cells were resuspended to 1 to 2 × 106 per ml in modified Tyrode's buffer (15), and 3 to 6 × 104 cells were incubated in a final volume of 50 μl for 20 min at room temperature with 200 μg/ml biotin-fibrinogen and 10 μg/ml phycoerythrin-streptavidin. Some samples were stimulated during this time with 50 μM epinephrine, 50 μM ADP, and 1 mM PAR4 thrombin receptor-activating peptide (AYPGFK). Nonspecific fibrinogen binding was assessed by blocking specific binding with 10 mM EDTA or 20 μg/ml anti-αIIbβ3 antibody 1B5 (supplied by B. Coller, Rockefeller University, New York; ref. 30). Specific binding, defined as total minus nonspecific binding, was quantified by flow cytometry (17). In some experiments, αIIbβ3 expression was measured simultaneously by using FITC-conjugated rat anti-murine αIIb.

GTP-bound Rap1b was detected in 200 μg of megakaryocyte lysates by a pull-down assay with the Rap/Ras-binding domain of RalGDS (15, 31). Total Rap1b was detected on Western blots of 5-μg samples of megakaryocyte lysates with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). CalDAG-GEFI expression was assessed on Western blots of 20-μg samples of lysates with an antibody to V5 (Invitrogen) or a specific monoclonal antibody (provided by A. Graybiel, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge; ref. 19).

To study the actin cytoskeleton, megakaryocytes were resuspended in modified Walsh buffer and plated for 45 min at 37°C on fibrinogen-coated coverslips in the presence of 100 nM phorbol myristate acetate to enhance cell spreading (17). After fixation and permeabilization, adherent cells were stained for vinculin and F-actin and analyzed by confocal microscopy (17, 32).

Results

Characterization of Megakaryocytes Derived from ES Cells.

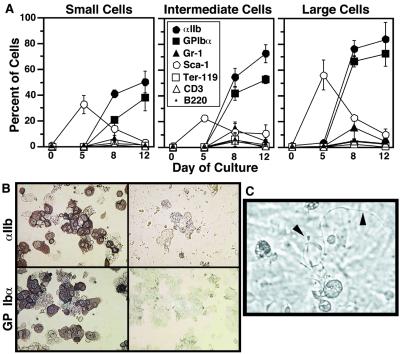

The feasibility of obtaining mature megakaryocytes from murine ES cells was evaluated by coculturing R1 ES cells with OP9 stromal cells. After 5 days in this system, ES cells develop into primitive erythrocytes and definitive multipotential hematopoietic progenitors (25, 33). When the cells on day 5 were cultured for up to seven more days (day 12) in the presence of TPO and other growth factors, a progressive increase in the percentage of intermediate and large cells was noted by flow cytometry (Fig. 1A). Concomitant cytospin preparations stained with Wright-Giemsa showed an increase in the proportion of intermediate and large, polyploid cells morphologically indistinguishable from young and mature megakaryocytes, respectively (Fig. 1B). When DNA ploidy was examined on day 12, small cells were predominantly 2n, intermediate cells 2–32n and large cells 16–128n, consistent with megakaryocyte maturation (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Development of megakaryocytes from ES cells. (A) Flow cytometric dot plots of forward and side light-scatter profiles of 20,000 live cells. Before analysis, embryonic feeder cells on day 0 or OP 9 stromal cells on subsequent days were depleted by adhesive selection as described in Methods. In each plot, three arbitrary analysis gates have been drawn containing small, intermediate, and large cells, respectively. (B) Cell morphology in cytospin preparations stained with Wright-Giemsa (×40). (C) DNA ploidy on day 12 of the differentiation protocol. αIIb-positive cells were stained with propidium iodide and analyzed for DNA content by flow cytometry.

To document the maturation process further, expression of stem cell and differentiation markers was determined by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells that expressed the hematopoietic stem cell marker, Sca-1, peaked on day 5 and decreased thereafter. In contrast, expression of platelet glycoproteins αIIb and GPIbα increased progressively (Fig. 2A). Few cells at any time point expressed erythrocyte (Ter-119), granulocyte (Gr-1), or lymphocyte (CD3, B220) antigens. Immunocytochemistry confirmed that the intermediate and large cells identified morphologically as megakaryocytes expressed αIIb and GP Ibα (Fig. 2B). A limited study of proteins by flow cytometry or Western blotting showed that these cells also express other receptors and signaling molecules present in platelets (α5β1, P-selectin, ERK1/2, PLCγ, Src, Syk, SLP-76, Vav1, and VASP) (not shown).

Figure 2.

Cell surface markers and proplatelet formation during megakaryocyte development from ES cells. (A) Cell surface expression of hematopoietic differentiation markers. Cells were categorized by size on the basis of light scatter as in Fig. 1A, and the percentage of cells that expressed each surface marker was determined by flow cytometry. Data represent means ± SEM of four experiments. (B) Immunocytochemical analysis on day 8 of the differentiation protocol confirms expression of αIIb and GP Ibα in intermediate and large cells (Left). Negative staining by control IgG is shown on Right. (C) On day 12, phase-contrast microscopy shows large megakaryocytes with proplatelets (arrowheads).

A characteristic of fully mature megakaryocytes is the capacity to send out proplatelets, long, beaded projections from which platelets are derived (34, 35). Indeed, about 10% of large megakaryocytes derived from ES cells exhibited proplatelets (Fig. 2C, arrowheads). The OP9 culture system yielded megakaryocytes on a scale sufficient for biochemical and functional studies. Typically, an initial culture of 1 × 104 ES cells yielded 6 × 104 viable, αIIb-positive cells on day 12, of which two-thirds were intermediate and large megakaryocytes. These results indicate that megakaryocytes can be derived relatively rapidly and in quantity from ES cells, enabling further investigation of αIIbβ3 function.

αIIbβ3 Signaling in Megakaryocytes Derived from ES Cells.

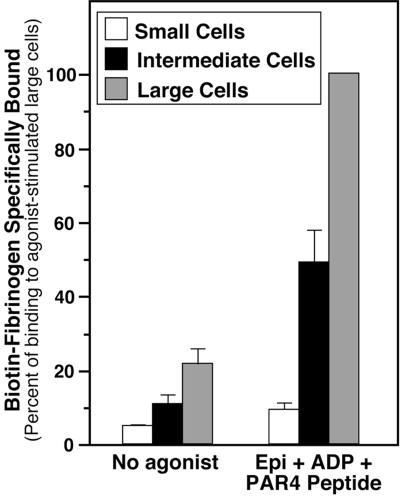

To determine whether megakaryocyte progenitors or megakaryocytes derived from ES cells are capable of undergoing inside-out signaling, the specific binding of fibrinogen to αIIbβ3-positive cells was analyzed by flow cytometry on day 12 of the differentiation protocol. Whereas αIIbβ3-positive cells of all sizes bound relatively little fibrinogen before stimulation by platelet agonists, large megakaryocytes bound fibrinogen in response to a PAR4 thrombin receptor-activating peptide (AYPGFK), and as shown in Fig. 3, to a combination of AYPGFK, epinephrine, and ADP. This response was 47% of that induced by 0.5 mM MnCl2, a direct activator of αIIbβ3 (not shown). Unlike large megakaryocytes, small αIIbβ3-positive progenitors were relatively unresponsive to these agonists, and intermediate-size megakaryocytes exhibited an intermediate response (Fig. 3). These results held true when fibrinogen binding was normalized for levels of αIIbβ3 surface expression or when two other ES cell lines (E14; W4/129S6) were used instead of R1 to derive megakaryocytes (not shown). Thus, although megakaryocyte progenitors derived from ES cells express αIIbβ3, inside-out signaling is not developed until megakaryocytes become mature, just as with bone marrow-derived megakaryocytes (17).

Figure 3.

Fibrinogen binding to αIIb-positive cells derived from ES cells. As described in Methods, cells on day 12 of the differentiation protocol were incubated with biotin-fibrinogen, FITC-conjugated anti-αIIb, phycoerythrin-streptavidin, and, where indicated, a combination of epinephrine, ADP, and PAR4 thrombin receptor-activating peptide, AYPGFK. Fibrinogen binding was then quantified by flow cytometry. Nonspecific fibrinogen binding was determined in the presence of 10 mM EDTA. Specific binding, defined as total minus nonspecific binding, is expressed as a percentage of binding to agonist-stimulated large cells. Data represent means ± SEM of four experiments.

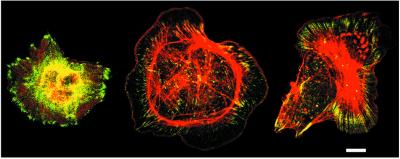

To determine whether ES cell-derived megakaryocytes reorganize their cytoskeletons in response to αIIbβ3 ligation, cells on day 12 were plated on fibrinogen in the presence of 100 nM phorbol myristate acetate, which activates protein kinase C and promotes cell spreading. Under these conditions, large megakaryocytes exhibited prominent vinculin-rich focal adhesions and actin stress fibers (Fig. 4). This response depended on αIIbβ3 because megakaryocyte adhesion to fibrinogen was blocked by antibody 1B5 (not shown). Thus, ES cell-derived megakaryocytes display bidirectional αIIbβ3 signaling, similar to platelets.

Figure 4.

αIIbβ3-dependent cytoskeletal organization in ES cell-derived megakaryocytes. On day 12 of the differentiation protocol, megakaryocytes were plated on fibrinogen for 45 min in the presence of 100 nM phorbol myristate acetate. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for vinculin with a specific antibody (green) and for F-actin with rhodamine-phalloidin (red). Megakaryocytes exhibit vinculin-rich focal adhesions and actin stress fibers, and the two cells on the right show prominent lamellipodial extensions. (Bar = 10 μm.)

Characterization of a Candidate Integrin Regulator with ES Cell-Derived Megakaryocytes.

Bone marrow-derived megakaryocytes from mice deficient in transcription factor NF-E2 show defective inside-out αIIbβ3 signaling (17). Gene profiling by using cDNA arrays and Western blotting have identified CalDAG-GEFI as one of several genes whose expression is reduced in these cells (R.M., S.W.K., M. Shiraga, A. Alizadeh, M. Diehn, P. O. Brown, S.J.S., and A.D.L., unpublished observations). CalDAG-GEFI is an exchange factor for Rap1 (19–21), and expression of a constitutively active Rap1b mutant in normal megakaryocytes enhances agonist-induced fibrinogen binding (15). Therefore, to determine the suitability of ES cell-derived megakaryocytes as a platform for candidate gene analysis, CalDAG-GEFI was retrovirally expressed and the effects on Rap1b and αIIbβ3 function were examined.

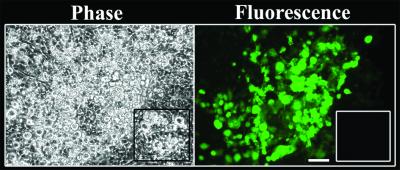

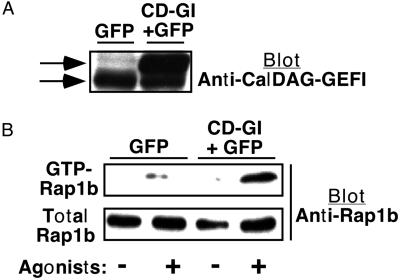

ES cell-derived hematopoietic progenitors were exposed on day 5 of differentiation to a retrovirus encoding both CalDAG-GEFI and GFP. A control virus encoded only GFP. When studied on day 12, 10–50% of the intermediate and large megakaryocytes exposed to either virus were successfully transduced, as assessed by GFP expression (Fig. 5). Expression of CalDAG-GEFI was confirmed on Western blots (Fig. 6A). Megakaryocyte development from ES cells was unaffected by retroviral infection or expression of CalDAG-GEFI and GFP. To determine whether CalDAG-GEFI could function as a Rap1b GEF in megakaryocytes, the GTP-loaded form of Rap1b was detected by a pull-down assay by using the Rap/Ras-binding domain of Ral GDS. Unstimulated megakaryocytes that had been exposed to the CalDAG-GEFI/GFP virus exhibited a relatively low level of GTP-Rap1b, albeit slightly higher than that of control megakaryocytes exposed to the GFP virus (Fig. 6B). However, stimulation of megakaryocytes with epinephrine, ADP and AYPGFK for 1 min caused an increase in GTP-Rap1b, and this response was further enhanced in cells infected with the CalDAG-GEFI/GFP virus (Fig. 6B). Thus, forced expression of CalDAG-GEFI enhances agonist-induced activation of endogenous Rap1b in ES cell-derived megakaryocytes, consistent with its role as a Rap1 GEF.

Figure 5.

Retrovirus-mediated expression of GFP in ES cell-derived megakaryocytes. After 5 days of coculture with OP9 cells, ES-derived cells were infected with retrovirus encoding CalDAG-GEFI and GFP, as described in Methods. The differentiation protocol was continued until day 12, at which time cultures were examined in an inverted fluorescence microscope. GFP-positive megakaryocytes are visible by fluorescence microscopy after viral infection but not after mock infection (Inset). In contrast to megakaryocytes, the underlying layer of OP9 stromal cells shows no fluorescence. (Bar = 100 μm.)

Figure 6.

Effect of CalDAG-GEFI expression on Rap1b activation in ES cell-derived megakaryocytes. On day 5 of the differentiation protocol, hematopoietic cells were infected with virus-encoding GFP alone or GFP and CalDAG-GEFI (CD-GI). The protocol was continued until day 12, at which time megakaryocytes were incubated for 1 min with or without epinephrine (50 μM), ADP (50 μM), and AYPGFK (1 mM). Then, CalDAG-GEFI expression and GTP-Rap1b were assessed as described in Methods. (A) Western blot shows expression of endogenous (lower arrow) and recombinant (upper arrow) CalDAG-GEFI, detected with a specific antibody. The identity of recombinant CalDAG-GEFI was confirmed with an antibody to the V5 epitope (not shown). (B) GTP-Rap1b as assessed by a pull-down assay. Total Rap1b in the starting lysate is shown as a control. Based on quantification of band intensities on blots subjected to identical chemiluminescence development times, GTP-Rap1b represented approximately 37% of total Rap1b in agonist-stimulated control cells and 70% in agonist-stimulated CalDAG-GEFI-expressing cells. This experiment is representative of three so performed.

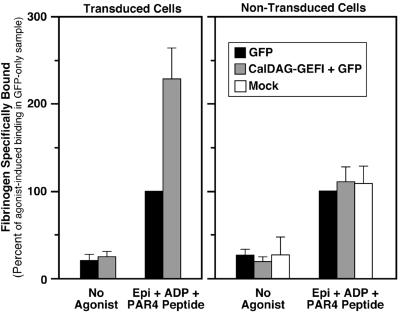

Fig. 7 shows the effects of CalDAG-GEFI expression on fibrinogen binding to megakaryocytes. In the absence of a platelet agonist, megakaryocytes bound little or no fibrinogen, whether or not they had been transduced with the GFP virus or the CalDAG-GEFI/GFP virus. When stimulated with ADP, epinephrine, and AYPGFK, nontransduced megakaryocytes and megakaryocytes expressing GFP now bound fibrinogen. By comparison, agonist-stimulated megakaryocytes expressing both CalDAG-GEFI and GFP bound even more fibrinogen, and this difference was significant (P < 0.01). The effect of CalDAG-GEFI expression was due to modulation of αIIbβ3 affinity/avidity because surface expression of αIIbβ3 was not affected (not shown). Moreover, the effect of CalDAG-GEFI was cell-autonomous because it was not observed in megakaryocytes that had been exposed to the CalDAG-GEFI/GFP virus but not successfully transduced (Fig. 7). Thus, forced expression of CalDAG-GEFI leads to enhanced agonist-induced activation of αIIbβ3, presumably by activating Rap1b.

Figure 7.

Effect of CalDAG-GEFI expression on fibrinogen binding to ES cell-derived megakaryocytes. On day 5 of the differentiation protocol, hematopoietic cells were infected with virus-encoding GFP alone or GFP and CalDAG-GEFI. The differentiation protocol was continued until day 12, at which time fibrinogen binding to large megakaryocytes was quantified. Specific fibrinogen binding is expressed as a percentage of the agonist-induced binding observed with cells exposed to control virus encoding only GFP. (Left) Transduced (GFP-positive) cells; (Right) nontransduced cells. Note that CalDAG-GEFI-enhanced fibrinogen binding only in cells that had been transduced. Data are means ± SEM of six experiments.

Discussion

Because αIIbβ3 transduces signals required for platelet function in hemostasis, the relationship of this integrin to intracellular signaling pathways remains an area of active investigation (4, 36). To understand better the molecular mechanisms of αIIbβ3 signaling, we have adopted the approach of using the primary megakaryocyte as a biologically relevant nucleated cell-model system (17). Although megakaryocytes represent a minor fraction of normal bone marrow cells, they can be expanded from murine bone marrow or fetal liver cells by using media supplemented with TPO and other growth factors (37, 38). Here we sought to expand the utility of the megakaryocyte system dramatically by turning to a potentially inexhaustible source of megakaryocytes, the murine ES cell. The major findings are: (i) Mature megakaryocytes can be obtained in quantity from ES cells, they elaborate proplatelets, and their gene expression can be manipulated by using retroviral vectors. (ii) Mature megakaryocytes derived from ES cells exhibit bidirectional αIIbβ3 signaling, similar to platelets and bone marrow-derived megakaryocytes. (iii) ES cell-derived megakaryocytes are suitable for evaluating the role of candidate genes in integrin signaling as exemplified by CalDAG-GEFI, whose forced expression led to enhanced activation of Rap1b and αIIbβ3 in response to platelet agonists.

ES cells cultured for 5 days in serum on a layer of OP9 stromal cells proliferate and differentiate into multipotential hematopoietic progenitors. By coculture for an additional 3–7 days in the presence of appropriate growth factors, these progenitors can expand into differentiated hematopoietic or endothelial cells (25, 33, 39). In the current protocol starting with 104 ES cells and by using TPO, IL-6, and IL-11 to expand the megakaryocyte lineage, 4 × 104 polyploid megakaryocytes were typically obtained after 12 days of the differentiation protocol, and some of these cells displayed proplatelets. Given their large size and mass relative to other hematopoietic cells in the culture, ES cell-derived megakaryocytes provided sufficient starting material even at this scale for functional studies of αIIbβ3. Accordingly, this system should prove useful for studying other aspects of megakaryocyte and platelet biology.

Progenitors and megakaryocytes derived from murine ES cells closely resembled their bone marrow- or fetal liver-derived counterparts (17, 37, 38). In particular, only the more mature megakaryocytes exhibited proplatelet formation and agonist-induced fibrinogen binding (Figs. 2 and 3). The three agonists used here to trigger fibrinogen binding, ADP, epinephrine, and AYPGFK, engage specific heptahelical, G protein-coupled receptors in platelets (40). Because at least one of these receptors, the PAR4 thrombin receptor, is capable of triggering calcium fluxes even in immature megakaryocytes (A.D.L., unpublished observations), normal inside-out signaling to αIIbβ3 presumably involves one or more signaling intermediates downstream of agonist receptors whose expression is developmentally regulated during megakaryocytopoiesis. In this regard, several other integrins expressed during hematopoiesis are subject to affinity/avidity modulation, including α2β1, α4β1, α5β1, and αVβ3 (41–44). Of these, α4β1 and α5β1 are involved in the development and homing of hematopoietic progenitors (45–47). Therefore, unlike αIIbβ3, the inside-out signaling pathways for these other integrins may be functionally intact early in hematopoietic development. If true, the fine details of inside-out signaling may be integrin-specific, an idea that can now be tested by using activation-dependent, integrin-specific ligands at defined stages of megakaryocyte development (15, 41–44).

Megakaryocytes plated on fibrinogen spread and developed vinculin-rich focal adhesions and actin stress fibers (Fig. 4). Although αIIbβ3-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangements are important for platelet function, their significance for megakaryocytes is less clear because this integrin is not required for platelet formation (48, 49). However, signaling events and cytoskeletal reorganization stimulated by ligation of αIIbβ3 may still play some role in thrombogenesis (50, 51). Indeed, proplatelet/platelet formation seems to involve proteins that could be affected by outside-in signaling through αIIbβ3 or other integrins, including protein kinase C, mitogen-activated protein kinase, β1-tubulin, and actin filaments (35, 52–54). Therefore, further studies of cytoskeletal organization and proplatelet formation in megakaryocytes derived from homozygous integrin knockout ES cells are warranted.

CalDAG-GEFI is a member of the RasGRP/CalDAG-GEF family of Ras GEFs. Although it has marked GEF activity toward Rap1, it is reported to have some activity for N-Ras, R-Ras, K-Ras, and TC21, but not H-Ras (19–21, 55). CalDAG-GEFI contains a Ras exchanger motif (REM) domain common to Ras family GEFs, a cdc25-like GEF domain, two EF hand motifs for interaction with Ca2+, and a C1 domain for interaction with diacylglycerol/phorbol esters. The potential relevance of CalDAG-GEFI to αIIbβ3 function was suggested by gene-profiling comparisons of normal and NF-E2−/− megakaryocytes, which are deficient in agonist-induced fibrinogen binding (17) and CalDAG-GEFI (R.M., S.W.K., A. M. Shiraga, A. Alizadeh, M. Diehn, P. O. Brown, S.J.S., and A.D.L., unpublished observations). Although it remains to be determined whether expression of CalDAG-GEFI is sufficient to rescue αIIbβ3 function in NF-E2−/− megakaryocytes, this Rap1 GEF is a particularly attractive candidate to regulate inside-out signaling because (i) thrombin and other agonists stimulate increases in Ca2+ and diacylglycerol and induce Rap1 activation in platelets (56); and (ii) constitutively active Rap1b increases whereas Rap1 GAP decreases agonist-induced fibrinogen binding to bone marrow-derived megakaryocytes (15).

After retroviral transduction of CalDAG-GEFI and GFP into ES cell-derived hematopoietic progenitors, both proteins became expressed in a proportion of intermediate and large megakaryocytes. Significantly, expression of CalDAG-GEFI was associated with an enhancement of agonist-induced activation of endogenous Rap1b (Fig. 6B) and fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3 (Fig. 7), which suggests that the effect of CalDAG-GEFI on αIIbβ3 is through Rap1b. At present, it is not known whether platelets or megakaryocytes express other Ras proteins potentially targeted by CalDAG-GEFI; consequently, additional work will be required to determine whether the effect of CalDAG-GEFI on αIIbβ3 is mediated exclusively through Rap1. Moreover, CalDAG-GEFI may not be the only GEF for Rap1b in platelets and megakaryocytes. Nonetheless, this work indicates that CalDAG-GEFI is likely to be an important component of agonist-regulated pathways leading to affinity/avidity modulation of αIIbβ3. In fact, because CalDAG-GEFI expression in a myeloblastic cell line promotes β1 integrin-dependent adhesion to fibronectin (20), this GEF may be more generally involved in transducing agonist signals to Rap1 and the integrins.

Altogether, these results establish that ES cells are a ready source of megakaryocytes for analysis of megakaryocytopoiesis, thrombopoiesis, and integrin signaling. By extrapolation, the in vitro production of megakaryocyte lineage cells from human embryonic stem cells could have implications in transfusion medicine for the prophylaxis and treatment of bleeding disorders caused by platelet deficiency or dysfunction (57).

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Coller, A. Dupuy, A. Graybiel, D. Largaespada, and V. Ramikrishnan for supplying vectors or antibodies, and Barry Moran for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (to A.D.L., H.S., and S.J.S.). K.E. and R.M. were supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the American Heart Association and the Health Research Board of Ireland, respectively.

Abbreviations

- ES

embryonic stem

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- TPO

thrombopoietin

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Bazzoni G, Hemler M E. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:30–34. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hato T, Pampori N, Shattil S J. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1685–1695. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beglova N, Blacklow S C, Takagi J, Springer T A. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:282–287. doi: 10.1038/nsb779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shattil S J, Kashiwagi H, Pampori N. Blood. 1998;91:2645–2657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calderwood D A, Zent R, Grant R, Rees D J G, Hynes R O, Ginsberg M H. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28071–28074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett J S, Zigmond S, Vilaire G, Cunningham M, Bednar B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25301–25307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sambrano G R, Weiss E J, Zheng Y W, Huang W, Coughlin S R. Nature (London) 2001;413:74–78. doi: 10.1038/35092573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fabre J E, Nguyen M T, Latour A, Keifer J A, Audoly L P, Coffman T M, Koller B H. Nat Med. 1999;5:1199–1202. doi: 10.1038/13522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollopeter G, Jantzen H M, Vincent D, Li G, England L, Ramakrishnan V, Yang R B, Nurden P, Nurden A, Julius D, Conley P B. Nature (London) 2001;409:202–207. doi: 10.1038/35051599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Offermanns S. Oncogene. 2001;20:1635–1642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirsch E, Bosco O, Tropel P, Laffargue M, Calvez R, Altruda F, Wymann M, Montrucchio G. FASEB J. 2001;15:2019–2021. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0810fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauser W, Knobeloch K P, Eigenthaler M, Gambaryan S, Krenn V, Geiger J, Glazova M, Rohde E, Horak I, Walter U, Zimmer M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8120–8125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azam M, Andrabi S S, Sahr K E, Kamath L, Kuliopulos A, Chishti A H. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2213–2220. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.2213-2220.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patil S, Newman D K, Newman P J. Blood. 2001;97:1727–1732. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertoni A, Tadokoro S, Eto K, Pampori N, Parise L V, White G C, Shattil S. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25715–25721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoying J B, Yin M, Diebold R, Ormsby I, Becker A, Doetschman T. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31008–31013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.31008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiraga M, Ritchie A, Aidoudi S, Baron V, Wilcox D, White G, Ybarrondo B, Murphy G, Leavitt A, Shattil S. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1419–1430. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faraday N, Rade J J, Johns D C, Khetawat G, Noga S J, DiPersio J F, Jin Y, Nichol J L, Haug J S, Bray P F. Blood. 1999;94:4084–4092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawasaki H, Springett G M, Toki S, Canales J J, Harlan P, Blumenstiel J P, Chen E J, Bany I A, Mochizuki N, Ashbacher A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13278–13283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dupuy A J, Morgan K, von Lintig F C, Shen H, Acar H, Hasz D E, Jenkins N A, Copeland N G, Boss G R, Largaespada D A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11804–11811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008970200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cullen P J, Lockyer P J. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:339–348. doi: 10.1038/nrm808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keller G, Kennedy M, Papayannopoulou T, Wiles M V. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:473–486. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uzan G, Prandini M H, Rosa J P, Berthier R. Stem Cells (Dayton) 1996;14, Suppl. 1:194–199. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530140725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filippi M D, Porteu F, Le Pesteur F, Rameau P, Nogueira M M, Debili N, Vainchenker W, de Sauvage F J, Kupperschmitt A D, Sainteny F. Exp Hematol. 2000;28:1363–1372. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00549-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Era T, Takagi T, Takahashi T, Bories J C, Nakano T. Blood. 2000;95:870–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Era T, Wong S, Witte O N. Methods Mol Biol. 2002;185:83–95. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-241-4:83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orkin S H, Zon L I. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:323–328. doi: 10.1038/ni0402-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, Abramow-Newerly W, Roder J C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8424–8428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soneoka Y, Cannon P M, Ramsdale E E, Griffiths J C, Romano G, Kingsman S M, Kingsman A J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:628–633. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.4.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lengweiler S, Smyth S S, Jirouskova M, Scudder L E, Park H, Moran T, Coller B S. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;262:167–173. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franke B, Akkerman J W N, Bos J L. EMBO J. 1997;16:252–259. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leng L, Kashiwagi H, Ren X-D, Shattil S J. Blood. 1998;91:4206–4215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakano T, Kodama H, Honjo T. Science. 1994;265:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.8066449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi E S, Nichol J L, Hokom M M, Hornkohl A C, Hunt P. Blood. 1995;85:402–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Italiano J E, Jr, Lecine P, Shivdasani R A, Hartwig J H. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1299–1312. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips D R, Prasad K S, Manganello J, Bao M, Nannizzi-Alaimo L. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:546–554. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drachman J G, Sabath D F, Fox N E, Kaushansky K. Blood. 1997;89:483–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lecine P, Blank V, Shivdasani R. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7572–7578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirashima M, Kataoka H, Nishikawa S, Matsuyoshi N. Blood. 1999;93:1253–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brass L F. In: Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. Hoffman R, Benz E, Shattil S, Furie B, Cohen H, Silberstein L, McGlave P, editors. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. pp. 1753–1782. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faull R J, Kovach N L, Harlan J M, Ginsberg M H. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:155–162. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pampori N, Hato T, Stupack D G, Aidoudi S, Cheresh D A, Nemerow G R, Shattil S J. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21609–21616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jung S M, Moroi M. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8016–8026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rose D M, Cardarelli P M, Cobb R R, Ginsberg M H. Blood. 2000;95:602–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coulombel L, Auffray I, Gaugler M H, Rosemblatt M. Acta Haematol. 1997;97:13–21. doi: 10.1159/000203655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verfaillie C M. Blood. 1998;92:2609–2612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papayannopoulou T, Priestley G V, Nakamoto B, Zafiropoulos V, Scott L M. Blood. 2001;98:2403–2411. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hodivala-Dilke K M, McHugh K P, Tsakiris D A, Rayburn H, Crowley D, Ullman-Cullere M, Ross F P, Coller B S, Teitelbaum S, Hynes R O. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:229–238. doi: 10.1172/JCI5487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tronik-Le Roux D, Roullot V, Poujol C, Kortulewski T, Nurden P, Marguerie G. Blood. 2000;96:1399–1408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leven R M, Tablin F. Exp Hematol. 1992;20:1316–1322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takahashi R, Sekine N, Nakatake T. Blood. 1999;93:1951–1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lecine P, Italiano J E, Jr, Kim S W, Villeval J L, Shivdasani R A. Blood. 2000;96:1366–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rojnuckarin P, Kaushansky K. Blood. 2001;97:154–161. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang F, Jia Y, Cohen I. Blood. 2002;99:3579–3584. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohba Y, Mochizuki N, Yamashita S, Chan A M, Schrader J W, Hattori S, Nagashima K, Matsuda M. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20020–20026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Franke B, Van Triest M, De Bruijn K M T, Van Willligen G, Nieuwenhuis H K, Negrier C, Akkerman J W N, Bos J L. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:779–785. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.779-785.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaufman D S, Hanson E T, Lewis R L, Auerbach R, Thomson J A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10716–10721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191362598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]